- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Win 10 Summer Reading Books from ThriftBooks 📚!

How To Write a Bibliography (Three Styles, Plus Examples)

Give credit where credit is due.

Writing a research paper involves a lot of work. Students need to consult a variety of sources to gather reliable information and ensure their points are well supported. Research papers include a bibliography, which can be a little tricky for students. Learn how to write a bibliography in multiple styles and find basic examples below.

IMPORTANT: Each style guide has its own very specific rules, and they often conflict with one another. Additionally, each type of reference material has many possible formats, depending on a variety of factors. The overviews shown here are meant to guide students in writing basic bibliographies, but this information is by no means complete. Students should always refer directly to the preferred style guide to ensure they’re using the most up-to-date formats and styles.

What is a bibliography?

When you’re researching a paper, you’ll likely consult a wide variety of sources. You may quote some of these directly in your work, summarize some of the points they make, or simply use them to further the knowledge you need to write your paper. Since these ideas are not your own, it’s vital to give credit to the authors who originally wrote them. This list of sources, organized alphabetically, is called a bibliography.

A bibliography should include all the materials you consulted in your research, even if you don’t quote directly from them in your paper. These resources could include (but aren’t limited to):

- Books and e-books

- Periodicals like magazines or newspapers

- Online articles or websites

- Primary source documents like letters or official records

Bibliography vs. References

These two terms are sometimes used interchangeably, but they actually have different meanings. As noted above, a bibliography includes all the materials you used while researching your paper, whether or not you quote from them or refer to them directly in your writing.

A list of references only includes the materials you cite throughout your work. You might use direct quotes or summarize the information for the reader. Either way, you must ensure you give credit to the original author or document. This section can be titled “List of Works Cited” or simply “References.”

Your teacher may specify whether you should include a bibliography or a reference list. If they don’t, consider choosing a bibliography, to show all the works you used in researching your paper. This can help the reader see that your points are well supported, and allow them to do further reading on their own if they’re interested.

Bibliography vs. Citations

Citations refer to direct quotations from a text, woven into your own writing. There are a variety of ways to write citations, including footnotes and endnotes. These are generally shorter than the entries in a reference list or bibliography. Learn more about writing citations here.

What does a bibliography entry include?

Depending on the reference material, bibliography entries include a variety of information intended to help a reader locate the material if they want to refer to it themselves. These entries are listed in alphabetical order, and may include:

- Author/s or creator/s

- Publication date

- Volume and issue numbers

- Publisher and publication city

- Website URL

These entries don’t generally need to include specific page numbers or locations within the work (except for print magazine or journal articles). That type of information is usually only needed in a footnote or endnote citation.

What are the different bibliography styles?

In most cases, writers use one of three major style guides: APA (American Psychological Association), MLA (Modern Language Association), or The Chicago Manual of Style . There are many others as well, but these three are the most common choices for K–12 students.

Many teachers will state their preference for one style guide over another. If they don’t, you can choose your own preferred style. However, you should also use that guide for your entire paper, following their recommendations for punctuation, grammar, and more. This will ensure you are consistent throughout.

Below, you’ll learn how to write a simple bibliography using each of the three major style guides. We’ve included details for books and e-books, periodicals, and electronic sources like websites and videos. If the reference material type you need to include isn’t shown here, refer directly to the style guide you’re using.

APA Style Bibliography and Examples

Source: Verywell Mind

Technically, APA style calls for a list of references instead of a bibliography. If your teacher requires you to use the APA style guide , you can limit your reference list only to items you cite throughout your work.

How To Write a Bibliography (References) Using APA Style

Here are some general notes on writing an APA reference list:

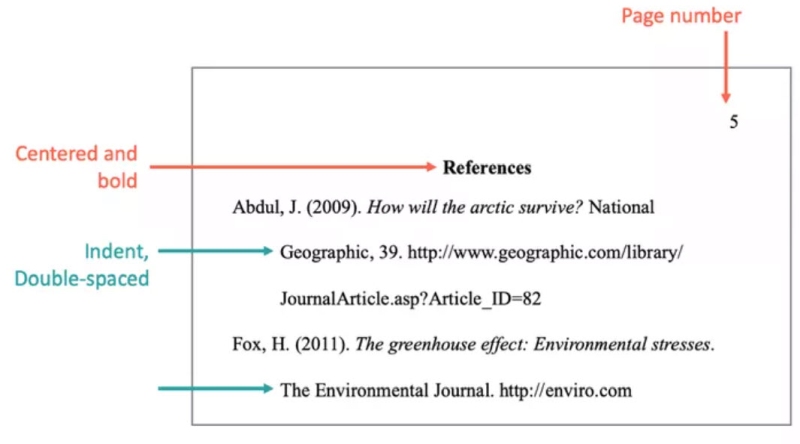

- Title your bibliography section “References” and center the title on the top line of the page.

- Do not center your references; they should be left-aligned. For longer items, subsequent lines should use a hanging indent of 1/2 inch.

- Include all types of resources in the same list.

- Alphabetize your list by author or creator, last name first.

- Do not spell out the author/creator’s first or middle name; only use their initials.

- If there are multiple authors/creators, use an ampersand (&) before the final author/creator.

- Place the date in parentheses.

- Capitalize only the first word of the title and subtitle, unless the word would otherwise be capitalized (proper names, etc.).

- Italicize the titles of books, periodicals, or videos.

- For websites, include the full site information, including the http:// or https:// at the beginning.

Books and E-Books APA Bibliography Examples

For books, APA reference list entries use this format (only include the publisher’s website for e-books).

Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Publication date). Title with only first word capitalized . Publisher. Publisher’s website

- Wynn, S. (2020). City of London at war 1939–45 . Pen & Sword Military. https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/City-of-London-at-War-193945-Paperback/p/17299

Periodical APA Bibliography Examples

For journal or magazine articles, use this format. If you viewed the article online, include the URL at the end of the citation.

Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Publication date). Title of article. Magazine or Journal Title (Volume number) Issue number, page numbers. URL

- Bell, A. (2009). Landscapes of fear: Wartime London, 1939–1945. Journal of British Studies (48) 1, 153–175. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25482966

Here’s the format for newspapers. For print editions, include the page number/s. For online articles, include the full URL.

Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Year, Month Date) Title of article. Newspaper title. Page number/s. URL

- Blakemore, E. (2022, November 12) Researchers track down two copies of fossil destroyed by the Nazis. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2022/11/12/ichthyosaur-fossil-images-discovered/

Electronic APA Bibliography Examples

For articles with a specific author on a website, use this format.

Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Year, Month Date). Title . Site name. URL

- Wukovits, J. (2023, January 30). A World War II survivor recalls the London Blitz . British Heritage . https://britishheritage.com/history/world-war-ii-survivor-london-blitz

When an online article doesn’t include a specific author or date, list it like this:

Title . (Year, Month Date). Site name. Retrieved Month Date, Year, from URL

- Growing up in the Second World War . (n.d.). Imperial War Museums. Retrieved May 12, 2023, from https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/growing-up-in-the-second-world-war

When you need to list a YouTube video, use the name of the account that uploaded the video, and format it like this:

Name of Account. (Upload year, month day). Title [Video]. YouTube. URL

- War Stories. (2023, January 15). How did London survive the Blitz during WW2? | Cities at war: London | War stories [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/uwY6JlCvbxc

For more information on writing APA bibliographies, see the APA Style Guide website.

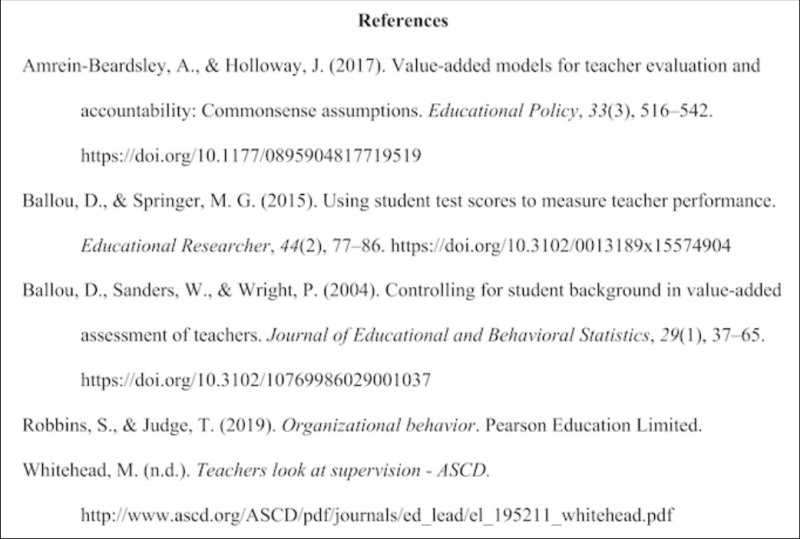

APA Bibliography (Reference List) Example Pages

Source: Simply Psychology

More APA example pages:

- Western Australia Library Services APA References Example Page

- Ancilla College APA References Page Example

- Scribbr APA References Page Example

MLA Style Bibliography Examples

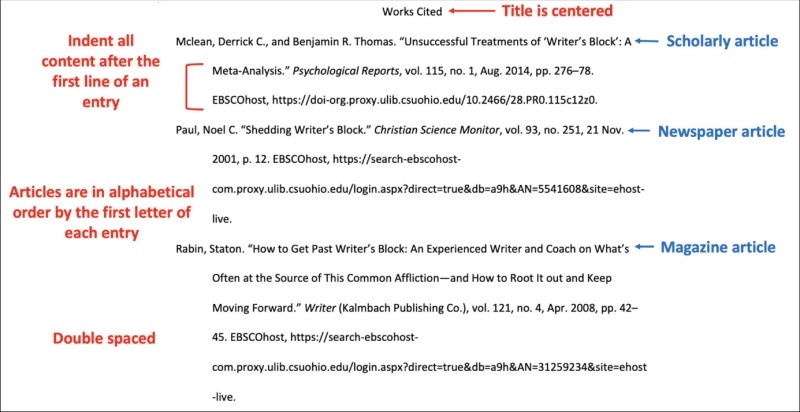

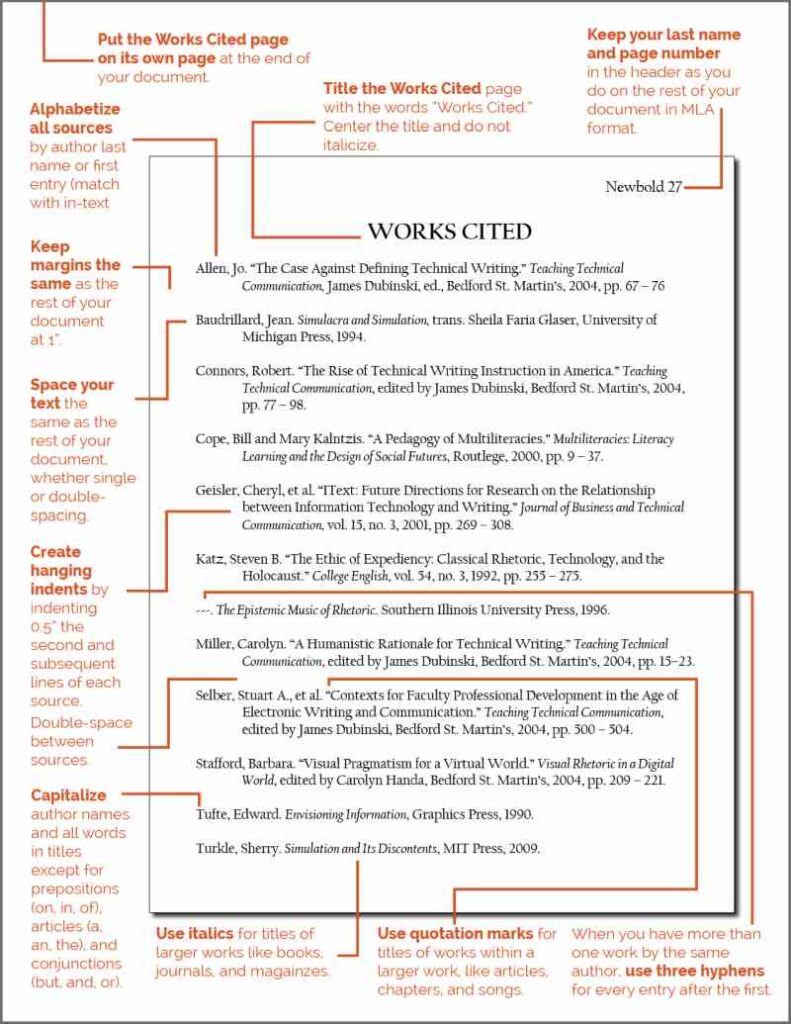

Source: PressBooks

MLA style calls for a Works Cited section, which includes all materials quoted or referred to in your paper. You may also include a Works Consulted section, including other reference sources you reviewed but didn’t directly cite. Together, these constitute a bibliography. If your teacher requests an MLA Style Guide bibliography, ask if you should include Works Consulted as well as Works Cited.

How To Write a Bibliography (Works Cited and Works Consulted) in MLA Style

For both MLA Works Cited and Works Consulted sections, use these general guidelines:

- Start your Works Cited list on a new page. If you include a Works Consulted list, start that on its own new page after the Works Cited section.

- Center the title (Works Cited or Works Consulted) in the middle of the line at the top of the page.

- Align the start of each source to the left margin, and use a hanging indent (1/2 inch) for the following lines of each source.

- Alphabetize your sources using the first word of the citation, usually the author’s last name.

- Include the author’s full name as listed, last name first.

- Capitalize titles using the standard MLA format.

- Leave off the http:// or https:// at the beginning of a URL.

Books and E-Books MLA Bibliography Examples

For books, MLA reference list entries use this format. Add the URL at the end for e-books.

Last Name, First Name Middle Name. Title . Publisher, Date. URL

- Wynn, Stephen. City of London at War 1939–45 . Pen & Sword Military, 2020. www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/City-of-London-at-War-193945-Paperback/p/17299

Periodical MLA Bibliography Examples

Here’s the style format for magazines, journals, and newspapers. For online articles, add the URL at the end of the listing.

For magazines and journals:

Last Name, First Name. “Title: Subtitle.” Name of Journal , volume number, issue number, Date of Publication, First Page Number–Last Page Number.

- Bell, Amy. “Landscapes of Fear: Wartime London, 1939–1945.” Journal of British Studies , vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 153–175. www.jstor.org/stable/25482966

When citing newspapers, include the page number/s for print editions or the URL for online articles.

Last Name, First Name. “Title of article.” Newspaper title. Page number/s. Year, month day. Page number or URL

- Blakemore, Erin. “Researchers Track Down Two Copies of Fossil Destroyed by the Nazis.” The Washington Post. 2022, Nov. 12. www.washingtonpost.com/science/2022/11/12/ichthyosaur-fossil-images-discovered/

Electronic MLA Bibliography Examples

Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title.” Month Day, Year published. URL

- Wukovits, John. 2023. “A World War II Survivor Recalls the London Blitz.” January 30, 2023. https://britishheritage.com/history/world-war-ii-survivor-london-blitz

Website. n.d. “Title.” Accessed Day Month Year. URL.

- Imperial War Museum. n.d. “Growing Up in the Second World War.” Accessed May 9, 2023. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/growing-up-in-the-second-world-war.

Here’s how to list YouTube and other online videos.

Creator, if available. “Title of Video.” Website. Uploaded by Username, Day Month Year. URL.

- “How did London survive the Blitz during WW2? | Cities at war: London | War stories.” YouTube . Uploaded by War Stories, 15 Jan. 2023. youtu.be/uwY6JlCvbxc.

For more information on writing MLA style bibliographies, see the MLA Style website.

MLA Bibliography (Works Cited) Example Pages

Source: The Visual Communication Guy

More MLA example pages:

- Writing Commons Sample Works Cited Page

- Scribbr MLA Works Cited Sample Page

- Montana State University MLA Works Cited Page

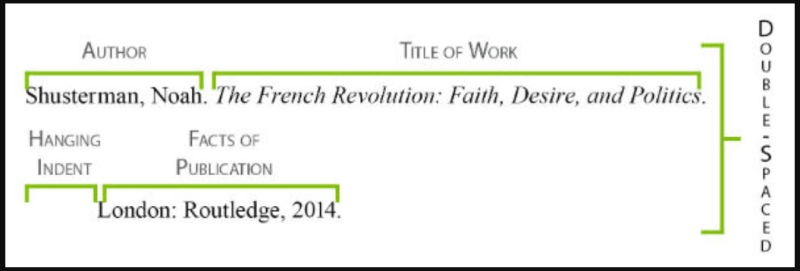

Chicago Manual of Style Bibliography Examples

The Chicago Manual of Style (sometimes called “Turabian”) actually has two options for citing reference material : Notes and Bibliography and Author-Date. Regardless of which you use, you’ll need a complete detailed list of reference items at the end of your paper. The examples below demonstrate how to write that list.

How To Write a Bibliography Using The Chicago Manual of Style

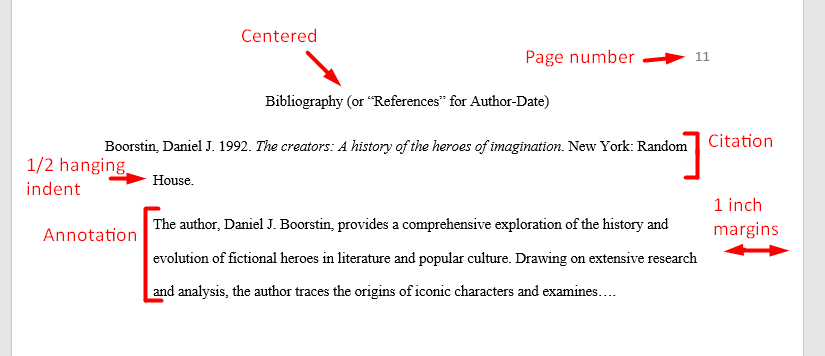

Source: South Texas College

Here are some general notes on writing a Chicago -style bibliography:

- You may title it “Bibliography” or “References.” Center this title at the top of the page and add two blank lines before the first entry.

- Left-align each entry, with a hanging half-inch indent for subsequent lines of each entry.

- Single-space each entry, with a blank line between entries.

- Include the “http://” or “https://” at the beginning of URLs.

Books and E-Books Chicago Manual of Style Bibliography Examples

For books, Chicago -style reference list entries use this format. (For print books, leave off the information about how the book was accessed.)

Last Name, First Name Middle Name. Title . City of Publication: Publisher, Date. How e-book was accessed.

- Wynn, Stephen. City of London at War 1939–45 . Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2020. Kindle edition.

Periodical Chicago Manual of Style Bibliography Examples

For journal and magazine articles, use this format.

Last Name, First Name. Year of Publication. “Title: Subtitle.” Name of Journal , Volume Number, issue number, First Page Number–Last Page Number. URL.

- Bell, Amy. 2009. “Landscapes of Fear: Wartime London, 1939–1945.” Journal of British Studies, 48 no. 1, 153–175. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25482966.

When citing newspapers, include the URL for online articles.

Last Name, First Name. Year of Publication. “Title: Subtitle.” Name of Newspaper , Month day, year. URL.

- Blakemore, Erin. 2022. “Researchers Track Down Two Copies of Fossil Destroyed by the Nazis.” The Washington Post , November 12, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2022/11/12/ichthyosaur-fossil-images-discovered/.

Electronic Chicago Manual of Style Bibliography Examples

Last Name, First Name Middle Name. “Title.” Site Name . Year, Month Day. URL.

- Wukovits, John. “A World War II Survivor Recalls the London Blitz.” British Heritage. 2023, Jan. 30. britishheritage.com/history/world-war-ii-survivor-london-blitz.

“Title.” Site Name . URL. Accessed Day Month Year.

- “Growing Up in the Second World War.” Imperial War Museums . www.iwm.org.uk/history/growing-up-in-the-second-world-war. Accessed May 9, 2023.

Creator or Username. “Title of Video.” Website video, length. Month Day, Year. URL.

- War Stories. “How Did London Survive the Blitz During WW2? | Cities at War: London | War Stories.” YouTube video, 51:25. January 15, 2023. https://youtu.be/uwY6JlCvbxc.

For more information on writing Chicago -style bibliographies, see the Chicago Manual of Style website.

Chicago Manual of Style Bibliography Example Pages

Source: Chicago Manual of Style

More Chicago example pages:

- Scribbr Chicago Style Bibliography Example

- Purdue Online Writing Lab CMOS Bibliography Page

- Bibcitation Sample Chicago Bibliography

Now that you know how to write a bibliography, take a look at the Best Websites for Teaching & Learning Writing .

Plus, get all the latest teaching tips and ideas when you sign up for our free newsletters .

You Might Also Like

Free Printable Homework Pass Set for K-12 Teachers

Plus ideas for using them. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Bibliography: Definition and Examples

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

A bibliography is a list of works (such as books and articles) written on a particular subject or by a particular author. Adjective : bibliographic.

Also known as a list of works cited , a bibliography may appear at the end of a book, report , online presentation, or research paper . Students are taught that a bibliography, along with correctly formatted in-text citations, is crucial to properly citing one's research and to avoiding accusations of plagiarism . In formal research, all sources used, whether quoted directly or synopsized, should be included in the bibliography.

An annotated bibliography includes a brief descriptive and evaluative paragraph (the annotation ) for each item in the list. These annotations often give more context about why a certain source may be useful or related to the topic at hand.

- Etymology: From the Greek, "writing about books" ( biblio , "book", graph , "to write")

- Pronunciation: bib-lee-OG-rah-fee

Examples and Observations

"Basic bibliographic information includes title, author or editor, publisher, and the year the current edition was published or copyrighted . Home librarians often like to keep track of when and where they acquired a book, the price, and a personal annotation, which would include their opinions of the book or of the person who gave it to them" (Patricia Jean Wagner, The Bloomsbury Review Booklover's Guide . Owaissa Communications, 1996)

Conventions for Documenting Sources

"It is standard practice in scholarly writing to include at the end of books or chapters and at the end of articles a list of the sources that the writer consulted or cited. Those lists, or bibliographies, often include sources that you will also want to consult. . . . "Established conventions for documenting sources vary from one academic discipline to another. The Modern Language Association (MLA) style of documentation is preferred in literature and languages. For papers in the social sciences the American Psychological Association (APA) style is preferred, whereas papers in history, philosophy, economics, political science, and business disciplines are formatted in the Chicago Manual of Style (CMS) system. The Council of Biology Editors (CBE) recommends varying documentation styles for different natural sciences." (Robert DiYanni and Pat C. Hoy II, The Scribner Handbook for Writers , 3rd ed. Allyn and Bacon, 2001)

APA vs MLA Styles

There are several different styles of citations and bibliographies that you might encounter: MLA, APA, Chicago, Harvard, and more. As described above, each of those styles is often associated with a particular segment of academia and research. Of these, the most widely used are APA and MLA styles. They both include similar information, but arranged and formatted differently.

"In an entry for a book in an APA-style works-cited list, the date (in parentheses) immediately follows the name of the author (whose first name is written only as an initial), just the first word of the title is capitalized, and the publisher's full name is generally provided.

APA Anderson, I. (2007). This is our music: Free jazz, the sixties, and American culture . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

By contrast, in an MLA-style entry, the author's name appears as given in the work (normally in full), every important word of the title is capitalized, some words in the publisher's name are abbreviated, the publication date follows the publisher's name, and the medium of publication is recorded. . . . In both styles, the first line of the entry is flush with the left margin, and the second and subsequent lines are indented.

MLA Anderson, Iain. This Is Our Music: Free Jazz, the Sixties, and American Culture . Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2007. Print. The Arts and Intellectual Life in Mod. Amer.

( MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers , 7th ed. The Modern Language Association of America, 2009)

Finding Bibliographic Information for Online Sources

"For Web sources, some bibliographic information may not be available, but spend time looking for it before assuming that it doesn't exist. When information isn't available on the home page, you may have to drill into the site, following links to interior pages. Look especially for the author's name, the date of publication (or latest update), and the name of any sponsoring organization. Do not omit such information unless it is genuinely unavailable. . . . "Online articles and books sometimes include a DOI (digital object identifier). APA uses the DOI, when available, in place of a URL in reference list entries." (Diana Hacker and Nancy Sommers, A Writer's Reference With Strategies for Online Learners , 7th ed. Bedford/St. Martin's, 2011)

- What Is a Bibliography?

- What Is a Citation?

- MLA Bibliography or Works Cited

- What Is a Senior Thesis?

- MLA Sample Pages

- How to Write a Bibliography For a Science Fair Project

- What Is a Style Guide and Which One Do You Need?

- What Is an Annotated Bibliography?

- Turabian Style Guide With Examples

- APA In-Text Citations

- Definition and Examples of Title Case and Headline Style

- Tips for Typing an Academic Paper on a Computer

- Documentation in Reports and Research Papers

- 140 Key Copyediting Terms and What They Mean

- Writing an Annotated Bibliography for a Paper

- MLA Style Parenthetical Citations

Citation Guide

- What is a Citation?

- Citation Generator

- Chicago/Turabian Style

- Paraphrasing and Quoting

- Examples of Plagiarism

What is a Bibliography?

What is an annotated bibliography, introduction to the annotated bibliography.

- Writing Center

- Writer's Reference Center

- Helpful Tutorials

- the authors' names

- the titles of the works

- the names and locations of the companies that published your copies of the sources

- the dates your copies were published

- the page numbers of your sources (if they are part of multi-source volumes)

Ok, so what's an Annotated Bibliography?

An annotated bibliography is the same as a bibliography with one important difference: in an annotated bibliography, the bibliographic information is followed by a brief description of the content, quality, and usefulness of the source. For more, see the section at the bottom of this page.

What are Footnotes?

Footnotes are notes placed at the bottom of a page. They cite references or comment on a designated part of the text above it. For example, say you want to add an interesting comment to a sentence you have written, but the comment is not directly related to the argument of your paragraph. In this case, you could add the symbol for a footnote. Then, at the bottom of the page you could reprint the symbol and insert your comment. Here is an example:

This is an illustration of a footnote. 1 The number “1” at the end of the previous sentence corresponds with the note below. See how it fits in the body of the text? 1 At the bottom of the page you can insert your comments about the sentence preceding the footnote.

When your reader comes across the footnote in the main text of your paper, he or she could look down at your comments right away, or else continue reading the paragraph and read your comments at the end. Because this makes it convenient for your reader, most citation styles require that you use either footnotes or endnotes in your paper. Some, however, allow you to make parenthetical references (author, date) in the body of your work.

Footnotes are not just for interesting comments, however. Sometimes they simply refer to relevant sources -- they let your reader know where certain material came from, or where they can look for other sources on the subject. To decide whether you should cite your sources in footnotes or in the body of your paper, you should ask your instructor or see our section on citation styles.

Where does the little footnote mark go?

Whenever possible, put the footnote at the end of a sentence, immediately following the period or whatever punctuation mark completes that sentence. Skip two spaces after the footnote before you begin the next sentence. If you must include the footnote in the middle of a sentence for the sake of clarity, or because the sentence has more than one footnote (try to avoid this!), try to put it at the end of the most relevant phrase, after a comma or other punctuation mark. Otherwise, put it right at the end of the most relevant word. If the footnote is not at the end of a sentence, skip only one space after it.

What's the difference between Footnotes and Endnotes?

The only real difference is placement -- footnotes appear at the bottom of the relevant page, while endnotes all appear at the end of your document. If you want your reader to read your notes right away, footnotes are more likely to get your reader's attention. Endnotes, on the other hand, are less intrusive and will not interrupt the flow of your paper.

If I cite sources in the Footnotes (or Endnotes), how's that different from a Bibliography?

Sometimes you may be asked to include these -- especially if you have used a parenthetical style of citation. A "works cited" page is a list of all the works from which you have borrowed material. Your reader may find this more convenient than footnotes or endnotes because he or she will not have to wade through all of the comments and other information in order to see the sources from which you drew your material. A "works consulted" page is a complement to a "works cited" page, listing all of the works you used, whether they were useful or not.

Isn't a "works consulted" page the same as a "bibliography," then?

Well, yes. The title is different because "works consulted" pages are meant to complement "works cited" pages, and bibliographies may list other relevant sources in addition to those mentioned in footnotes or endnotes. Choosing to title your bibliography "Works Consulted" or "Selected Bibliography" may help specify the relevance of the sources listed.

This information has been freely provided by plagiarism.org and can be reproduced without the need to obtain any further permission as long as the URL of the original article/information is cited.

How Do I Cite Sources? (n.d.) Retrieved October 19, 2009, from http://www.plagiarism.org/plag_article_how_do_i_cite_sources.html

The Importance of an Annotated Bibliography

An Annotated Bibliography is a collection of annotated citations. These annotations contain your executive notes on a source. Use the annotated bibliography to help remind you of later of the important parts of an article or book. Putting the effort into making good notes will pay dividends when it comes to writing a paper!

Good Summary

Being an executive summary, the annotated citation should be fairly brief, usually no more than one page, double spaced.

- Focus on summarizing the source in your own words.

- Avoid direct quotations from the source, at least those longer than a few words. However, if you do quote, remember to use quotation marks. You don't want to forget later on what is your own summary and what is a direct quotation!

- If an author uses a particular term or phrase that is important to the article, use that phrase within quotation marks. Remember that whenever you quote, you must explain the meaning and context of the quoted word or text.

Common Elements of an Annotated Citation

- Summary of an Article or Book's thesis or most important points (Usually two to four sentences)

- Summary of a source's methodological approach. That is, what is the source? How does it go about proving its point(s)? Is it mostly opinion based? If it is a scholarly source, describe the research method (study, etc.) that the author used. (Usually two to five sentences)

- Your own notes and observations on the source beyond the summary. Include your initial analysis here. For example, how will you use this source? Perhaps you would write something like, "I will use this source to support my point about . . . "

- Formatting Annotated Bibliographies This guide from Purdue OWL provides examples of an annotated citation in MLA and APA formats.

- << Previous: Examples of Plagiarism

- Next: ACM Style >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 2:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.limestone.edu/citation

What is Bibliography?: Meaning, Types, and Importance

A bibliography is a fundamental component of academic research and writing that serves as a comprehensive list of sources consulted and referenced in a particular work. It plays a crucial role in validating the credibility and reliability of the information presented by providing readers with the necessary information to locate and explore the cited sources. A well-constructed bibliography not only demonstrates the depth and breadth of research undertaken but also acknowledges the intellectual contributions of others, ensuring transparency and promoting the integrity of scholarly work. By including a bibliography, writers enable readers to delve further into the subject matter, engage in critical analysis, and build upon existing knowledge.

1.1 What is a Bibliography?

A bibliography is a compilation of sources that have been utilized in the process of researching and writing a piece of work. It serves as a comprehensive list of references, providing information about the various sources consulted, such as books, articles, websites, and other materials. The purpose of a bibliography is twofold: to give credit to the original authors or creators of the sources used and to allow readers to locate and access those sources for further study or verification. A well-crafted bibliography includes essential details about each source, including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication date, and publication information. By having a bibliography, writers demonstrate the extent of their research, provide a foundation for their arguments, and enhance the credibility and reliability of their work.

1.2 Types of Bibliography.

The bibliography is a multifaceted discipline encompassing different types, each designed to serve specific research purposes and requirements. These various types of bibliographies provide valuable tools for researchers, scholars, and readers to navigate the vast realm of literature and sources available. From comprehensive overviews to specialized focuses, the types of bibliographies offer distinct approaches to organizing, categorizing, and presenting information. Whether compiling an exhaustive list of sources, providing critical evaluations, or focusing on specific subjects or industries, these types of bibliographies play a vital role in facilitating the exploration, understanding, and dissemination of knowledge in diverse academic and intellectual domains.

As a discipline, a bibliography encompasses various types that cater to different research needs and contexts. The two main categories of bibliographies are

1. General bibliography, and 2. Special bibliography.

1.2.1. General Bibliography:

A general bibliography is a comprehensive compilation of sources covering a wide range of subjects, disciplines, and formats. It aims to provide a broad overview of published materials, encompassing books, articles, journals, websites, and other relevant resources. A general bibliography typically includes works from various authors, covering diverse topics and spanning different periods. It is a valuable tool for researchers, students, and readers seeking a comprehensive collection of literature within a specific field or across multiple disciplines. General bibliographies play a crucial role in guiding individuals in exploring a subject, facilitating the discovery of relevant sources, and establishing a foundation for further research and academic pursuits.

The general bibliography encompasses various subcategories that comprehensively cover global, linguistic, national, and regional sources. These subcategories are as follows:

- Universal Bibliography: Universal bibliography aims to compile a comprehensive list of all published works worldwide, regardless of subject or language. It seeks to encompass human knowledge and includes sources from diverse fields, cultures, and periods. Universal bibliography is a monumental effort to create a comprehensive record of the world’s published works, making it a valuable resource for scholars, librarians, and researchers interested in exploring the breadth of human intellectual output.

- Language Bibliography: Language bibliography focuses on compiling sources specific to a particular language or group of languages. It encompasses publications written in a specific language, regardless of the subject matter. Language bibliographies are essential for language scholars, linguists, and researchers interested in exploring the literature and resources available in a particular language or linguistic group.

- National Bibliography: The national bibliography documents and catalogs all published materials within a specific country. It serves as a comprehensive record of books, journals, periodicals, government publications, and other sources published within a nation’s borders. National bibliographies are essential for preserving a country’s cultural heritage, facilitating research within specific national contexts, and providing a comprehensive overview of a nation’s intellectual output.

- Regional Bibliography: A regional bibliography compiles sources specific to a particular geographic region or area. It aims to capture the literature, publications, and resources related to a specific region, such as a state, province, or local area. Regional bibliographies are valuable for researchers interested in exploring a specific geographic region’s literature, history, culture, and unique aspects.

1.2.2. Special Bibliography:

Special bibliography refers to a type of bibliography that focuses on specific subjects, themes, or niche areas within a broader field of study. It aims to provide a comprehensive and in-depth compilation of sources specifically relevant to the chosen topic. Special bibliographies are tailored to meet the research needs of scholars, researchers, and enthusiasts seeking specialized information and resources.

Special bibliographies can cover a wide range of subjects, including but not limited to specific disciplines, subfields, historical periods, geographical regions, industries, or even specific authors or works. They are designed to gather and present a curated selection of sources considered important, authoritative, or influential within the chosen subject area.

Special bibliography encompasses several subcategories that focus on specific subjects, authors, forms of literature, periods, categories of literature, and types of materials. These subcategories include:

- Subject Bibliography: Subject bibliography compiles sources related to a specific subject or topic. It aims to provide a comprehensive list of resources within a particular field. Subject bibliographies are valuable for researchers seeking in-depth information on a specific subject area, as they gather relevant sources and materials to facilitate focused research.

- Author and Bio-bibliographies: Author and bio-bibliographies focus on compiling sources specific to individual authors. They provide comprehensive lists of an author’s works, including their books, articles, essays, and other publications. Bio-bibliographies include biographical information about the author, such as their background, career, and contributions to their respective fields.

- Bibliography of Forms of Literature: This bibliography focuses on specific forms or genres of literature, such as poetry, drama, fiction, or non-fiction. It provides a compilation of works within a particular literary form, enabling researchers to explore the literature specific to their interests or to gain a comprehensive understanding of a particular genre.

- Bibliography of Materials of Particular Periods: Bibliographies of materials of particular periods compile sources specific to a particular historical period or time frame. They include works published or created during that period, offering valuable insights into the era’s literature, art, culture, and historical context.

- Bibliographies of Special Categories of Literature: This category compiles sources related to special categories or themes. Examples include bibliographies of children’s literature, feminist literature, postcolonial literature, or science fiction literature. These bibliographies cater to specific interests or perspectives within the broader field of literature.

- Bibliographies of Specific Types of Materials: Bibliographies of specific materials focus on compiling sources within a particular format or medium. Examples include bibliographies of manuscripts, rare books, visual art, films, or musical compositions. These bibliographies provide valuable resources for researchers interested in exploring a specific medium or format.

1.3 Functions of Bibliography

A bibliography serves several important functions in academic research, writing, and knowledge dissemination. Here are some key functions:

- Documentation: One of the primary functions of a bibliography is to document and record the sources consulted during the research process. By providing accurate and detailed citations for each source, it can ensure transparency, traceability, and accountability in scholarly work. It allows readers and other researchers to verify the information, trace the origins of ideas, and locate the original sources for further study.

- Attribution and Credit: The bibliography plays a crucial role in giving credit to the original authors and creators of the ideas, information, and materials used in research work. By citing the sources, the authors acknowledge the intellectual contributions of others and demonstrate academic integrity. This enables proper attribution and prevents plagiarism, ensuring ethical research practices and upholding the principles of academic honesty.

- Verification and Quality Control: It acts as a means of verification and quality control in academic research. Readers and reviewers can assess the information’s reliability, credibility, and accuracy by including a list of sources. This allows others to evaluate the strength of the evidence, assess the validity of the arguments, and determine the scholarly rigor of a work.

- Further Reading and Exploration: The bibliography is valuable for readers who wish to delve deeper into a particular subject or topic. By providing a list of cited sources, the bibliography offers a starting point for further reading and exploration. It guides readers to related works, seminal texts, and authoritative materials, facilitating their intellectual growth and expanding their knowledge base.

- Preservation of Knowledge: The bibliography contributes to the preservation of knowledge by cataloguing and documenting published works. It records the intellectual output within various fields, ensuring that valuable information is not lost over time. A bibliography facilitates the organization and accessibility of literature, making it possible to locate and retrieve sources for future reference and research.

- Intellectual Dialogue and Scholarship: The bibliography fosters intellectual dialogue and scholarship by facilitating the exchange of ideas and enabling researchers to build upon existing knowledge. By citing relevant sources, researchers enter into conversations with other scholars, engaging in a scholarly discourse that advances knowledge within their field of study.

A bibliography serves the important functions of documenting sources, crediting original authors, verifying information, guiding further reading, preserving knowledge, and fostering intellectual dialogue. It plays a crucial role in maintaining academic research’s integrity, transparency, and quality and ensures that scholarly work is built upon a solid foundation of evidence and ideas.

1.4 Importance of Bibliographic Services

Bibliographic services are crucial in academia, research, and information management. They are a fundamental tool for organizing, accessing, and preserving knowledge . From facilitating efficient research to ensuring the integrity and credibility of scholarly work, bibliographic services hold immense importance in various domains.

Bibliographic services are vital for researchers and scholars. These services provide comprehensive and reliable access to various resources, such as books, journals, articles, and other scholarly materials. By organizing these resources in a structured manner, bibliographic services make it easier for researchers to locate relevant information for their studies. Researchers can explore bibliographic databases, catalogues, and indexes to identify appropriate sources, saving them valuable time and effort. This accessibility enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of research, enabling scholars to stay up-to-date with the latest developments in their fields.

Bibliographic services also aid in the process of citation and referencing. Proper citation is an essential aspect of academic integrity and intellectual honesty. Bibliographic services assist researchers in accurately citing the sources they have used in their work, ensuring that credit is given where it is due. This not only acknowledges the original authors and their contributions but also strengthens the credibility and authenticity of the research. By providing citation guidelines, formatting styles, and citation management tools, bibliographic services simplify the citation process, making it more manageable for researchers.

Another crucial aspect of bibliographic services is their role in preserving and archiving knowledge. Libraries and institutions that provide bibliographic services serve as custodians of valuable information. They collect, organize, and preserve various physical and digital resources for future generations. This preservation ensures that knowledge is not lost or forgotten over time. Bibliographic services enable researchers, students, and the general public to access historical and scholarly materials, fostering continuous learning and intellectual growth.

Bibliographic services contribute to the dissemination of research and scholarly works. They provide platforms and databases for publishing and sharing academic outputs. By cataloguing and indexing research articles, journals, and conference proceedings, bibliographic services enhance the discoverability and visibility of scholarly work. This facilitates knowledge exchange, collaboration, and innovation within academic communities. Researchers can rely on bibliographic services to share their findings with a broader audience, fostering intellectual dialogue and advancing their respective fields.

In Summary, bibliographic services are immensely important in academia, research, and information management. They facilitate efficient analysis, aid in proper citation and referencing, preserve knowledge for future generations, and contribute to the dissemination of research. These services form the backbone of scholarly pursuits, enabling researchers, students, and professionals to access, utilize, and contribute to the vast wealth of knowledge available. As we continue to rely on information and research to drive progress and innovation, the significance of bibliographic services will only grow, making them indispensable resources in pursuing knowledge.

References:

- Reddy, P. V. G. (1999). Bio bibliography of the faculty in social sciences departments of Sri Krishnadevaraya university Anantapur A P India.

- Sharma, J.S. Fundamentals of Bibliography, New Delhi : S. Chand & Co.. Ltd.. 1977. p.5.

- Quoted in George Schneider, Theory of History of Bibliography. Ralph Robert Shaw, trans., New York : Scare Crow Press, 1934, p.13.

- Funk Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of the English language – International ed – Vol. I – New York : Funku Wagnalls Co., C 1965, p. 135.

- Shores, Louis. Basic reference sources. Chicago : American Library Association, 1954. p. 11-12.

- Ranganathan, S.R., Documentation and its facts. Bombay : Asia Publishing House. 1963. p.49.

- Katz, William A. Introduction to reference work. 4th ed. New York : McGraw Hill, 1982. V. 1, p.42.

- Robinson, A.M.L. Systematic Bibliography. Bombay : Asia Publishing House, 1966. p.12.

- Chakraborthi, M.L. Bibliography : In Theory and practice, Calcutta : The World press (P) Ltd.. 1975. p.343.

Related Posts

National bibliography, bibliographic services.

This site was… how do I say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve found something which helped me. Thanks!

You really make it seem so easy along with your presentation but I find this topic to be actually something which I think I would never understand. It kind of feels too complex and very vast for me. I am having a look ahead in your next publish, I’ll try to get the grasp of it!

I’m Ghulam Murtaza

Thank for your detailed explanation,the work really help me to understand bibliography more than I knew it before.

thanks for this big one, and i get concept about bibliography( reference) that is great!!!!!

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography: The Annotated Bibliography

- The Annotated Bibliography

- Fair Use of this Guide

Explanation, Process, Directions, and Examples

What is an annotated bibliography.

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations to books, articles, and documents. Each citation is followed by a brief (usually about 150 words) descriptive and evaluative paragraph, the annotation. The purpose of the annotation is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited.

Annotations vs. Abstracts

Abstracts are the purely descriptive summaries often found at the beginning of scholarly journal articles or in periodical indexes. Annotations are descriptive and critical; they may describe the author's point of view, authority, or clarity and appropriateness of expression.

The Process

Creating an annotated bibliography calls for the application of a variety of intellectual skills: concise exposition, succinct analysis, and informed library research.

First, locate and record citations to books, periodicals, and documents that may contain useful information and ideas on your topic. Briefly examine and review the actual items. Then choose those works that provide a variety of perspectives on your topic.

Cite the book, article, or document using the appropriate style.

Write a concise annotation that summarizes the central theme and scope of the book or article. Include one or more sentences that (a) evaluate the authority or background of the author, (b) comment on the intended audience, (c) compare or contrast this work with another you have cited, or (d) explain how this work illuminates your bibliography topic.

Critically Appraising the Book, Article, or Document

For guidance in critically appraising and analyzing the sources for your bibliography, see How to Critically Analyze Information Sources . For information on the author's background and views, ask at the reference desk for help finding appropriate biographical reference materials and book review sources.

Choosing the Correct Citation Style

Check with your instructor to find out which style is preferred for your class. Online citation guides for both the Modern Language Association (MLA) and the American Psychological Association (APA) styles are linked from the Library's Citation Management page .

Sample Annotated Bibliography Entries

The following example uses APA style ( Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th edition, 2019) for the journal citation:

Waite, L., Goldschneider, F., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review, 51 (4), 541-554. The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.

This example uses MLA style ( MLA Handbook , 9th edition, 2021) for the journal citation. For additional annotation guidance from MLA, see 5.132: Annotated Bibliographies .

Waite, Linda J., et al. "Nonfamily Living and the Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young Adults." American Sociological Review, vol. 51, no. 4, 1986, pp. 541-554. The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.

Versión española

Tambíen disponible en español: Cómo Preparar una Bibliografía Anotada

Content Permissions

If you wish to use any or all of the content of this Guide please visit our Research Guides Use Conditions page for details on our Terms of Use and our Creative Commons license.

Reference Help

- Next: Fair Use of this Guide >>

- Last Updated: Sep 29, 2022 11:09 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/annotatedbibliography

The Plagiarism Checker Online For Your Academic Work

Start Plagiarism Check

Editing & Proofreading for Your Research Paper

Get it proofread now

Online Printing & Binding with Free Express Delivery

Configure binding now

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Master degree

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Example sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Frequency distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Your Step to Success

Plagiarism Check within 10min

Printing & Binding with 3D Live Preview

Bibliography – Types, Formats & Examples

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Bibliographies are the backbone of academic research, providing a roadmap to the citing sources that shape scholarly discourse. Assembled with precision, and care, they not only acknowledge intellectual debts, but also offer pathways for further exploration. In this article, we delve into the significance of bibliography, exploring its role in guiding researchers through the labyrinth of knowledge.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Bibliography in a nutshell

- 2 Definition: Bibliography

- 3 Basic Bibliographic Entries

- 4 Types of Bibliographies

- 5 Analytical Bibliography

- 6 Annotated Bibliography

- 7 Enumerative Bibliography

- 8 Bibliographic Formats

Bibliography in a nutshell

A bibliography is an alphabetically organized list of sources, that you need to reference when writing scholarly articles, books, or research papers to avoid plagiarism.

Definition: Bibliography

A bibliography is a comprehensive list of sources , such as books and websites, that have been consulted or cited in a particular work. It serves as a reference list , providing readers with information about the sources used by the author, and allowing them to locate and verify those sources. Typically, they include detailed information for each source, such as the author’s name, title, publication date, publisher, and page numbers.

There are three major style guides, when it comes to citation: the APA citation style (American Psychological Association), MLA citation style (Modern Language Association), and Chicago style of citation. These include analytical bibliographies, enumerative bibliographies, and lastly, annotated bibliographies.

The term “bibliography” is generally used for any list of sources cited at the of an academic work. Some style guides refer to them using particular terminology . MLA format refers to it as a Works Cited page. Whereas, the American Psychological Association refers to it as an APA Reference page .

Basic Bibliographic Entries

Entries for each source cited or consulted, are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry includes essential bibliographic details such as:

- Authors or editors

- Title of the work

- Publishing date

- Relevant page numbers

Types of Bibliographies

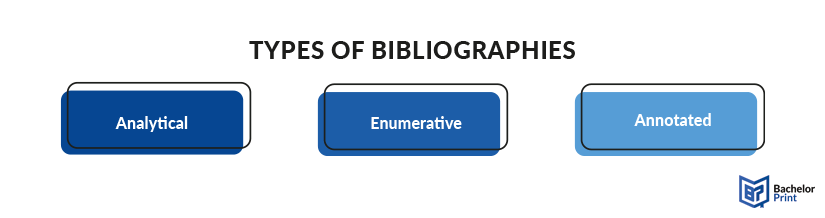

There are three common kinds of bibliography, each serving different purposes and focusing on various aspects of research and scholarship:

Enumerative

Analytical bibliographies go beyond simple description to analyze the content and structure of works. They include variations between different editions , each work’s number of pages , information concerning the booksellers and printers, paper and binding descriptions, and any insights that unfold as a book evolved from a manuscript to a published book. They are used by researchers interested in the history of books and printing.

- Details about each source, including the author’s name, publication title, etc.

- Analysis focusing on textual evidence, editorial decisions, etc.

- Explanation of the purpose and goal of the bibliography.

- Historical context on the source’s production, including printing technology etc.

- Comparison with other editions or versions, highlighting textual variations etc.

Annotated bibliographies include brief summaries or annotations of each source listed alphabetically, in addition to bibliographic information. This type provides an outline of the content and quality of the source, helping researchers evaluate its relevance for their own work.

- Details about each source, including the author’s name, title, etc.

- Brief summary (2-4 sentences) of the main points and arguments of each source.

- Assessment of quality, reliability, relevance, and credibility.

- Explanation of why the source was chosen and who it is intended for.

- Explanation of how the source relates to the research topic or question.

Students writing research papers commonly use enumerative bibliography. It is the most basic type, where the writer lists all sources used, providing bibliographic details for each work. Those sources share common characteristics such as language, topic, or period of time. Information concerning the source is then given by the writer to provide directions to the readers towards the source.

- A list of sources including details of the author’s name, title, etc.

- Method of organizing the bibliographic entries, such as alphabetical by author, etc.

- Description of the scope, including and specific criteria used to select or exclude sources.

- May include annotations providing further information, such as evaluations or summaries.

Analytical Bibliography

There are several distinctions for the analytical type. Three of them will be explained below.

Critical Analytical

Descriptive analytical, historical analytical.

Critical analytical bibliographies analyze the significance and meaning of textual variations . They may examine the implications of editorial decisions or printing errors on the interpretation and reception of a work. They often engage with literary theory, textual criticism, and scholarly debates. By critically examining the production history of a work, critical analytical bibliographies aim to shed light on the intentions of authors and editors, as well as the cultural and social contexts in which works were produced.

This analysis includes the following features:

- Providing textual analysis on variations, changes, and decisions

- Offering contextual information about the cultural, social, or political milieu

- Identifying differences, similarities, and unique contributions with other works

- Assessing the scholarly significance and impact of the work

Focus on providing detailed descriptions of the physical characteristics of books and printed materials. They aim to analyze aspects such as typography, binding, paper quality, illustrations, and textual variations. By documenting these features, descriptive analytical bibliographies facilitate the identification of different versions of a work, helping others trace the history of printing and publishing processes.

This analysis includes elements such as:

- Detailed description of physical characteristics

- Documentation of textual variations and discrepancies

- Analysis of editorial decisions or interventions

- Examination of printing history

- Comparison with other editions or versions

Historical analysis examines the production history and reception of relevant materials within their context. This involves studying factors such as printing technology, publishing practices, censorship, and readership. It aims to uncover the cultural, political, and intellectual significance of printed materials, shedding light on their roles in shaping historical developments and cultural movements.

This analysis generally outlines:

- Contextualization within historical, cultural, and social frameworks

- Documentation of publication history and evolution over time

- Analysis of reception and impact within historical context

- Examination of editorial practices and textual transmission

- Assessment of cultural, political, and intellectual significance

Annotated Bibliography

There are a few distinctions for the annotated bibliography type. Three of them will be explained in the following paragraph.

Critical Annotated

Descriptive annotated, informative annotated.

Critical annotations evaluate the strengths , weaknesses , and overall significance of the source, considering factors such as methodology , empirical evidence, authority, and bias. Critical annotations may include both positive and negative comments , and provide readers with insights into the credibility and usefulness of each source, helping them make informed decisions about its inclusion in their research.

This annotation may include the following elements:

- Examining the author’s bias or tone

- Evaluating the author’s qualifications

- Verifying the accuracy of the information

- Comparing the work with other publications on the topic

- Assessing the significance of the work’s contribution

These annotations provide a concise summary of the source’s content, focusing on key points and findings. Descriptive annotations aim to give readers a clear understanding of what the source covers without offering evaluation or critique. They are commonly used to provide basic information about each source listed in the annotated bibliography.

This annotation typically outlines:

- The primary objective of the work

- The contents covered in the work

- The conclusion drawn by the author

- The target audience

- The research methods employed by the author

- Distintice elements within the work, such as illustrations and tables.

Informative annotations serve as a hybrid between descriptive and critical ones, providing both a summary and evaluation of the source’s content. This type aims to inform readers about the key aspects, while also offering insights into its strengths and weaknesses. Overall, informative annotations aim to strike a balance between providing descriptive information and offering critical insights.

An informative annotation comprises the following aspects:

- Summary of the source’s content and message

- Includes the hypothesis, methodology, main points, and conclusion

- Does not offer editorial evaluative comment on the content.

Enumerative Bibliography

There are different types of the enumerative bibliography. Three of them will be explained down below.

Comprehensive Enumerative

Selective numerative, subject enumerative.

This type of bibliography aims to provide an exhaustive list of works on a particular subject without imposing strict selection criteria, offering researches a comprehensive overview of the literature available.

This specific type may include the following elements:

- Comprehensive coverage of relevant literature

- Emphasis on inclusivity, striving to list all known and available sources

- May include annotations or descriptive notes for further information about each source

- Regularly updating and maintaining the bibliography to ensure currency and relevance

The selective enumerative type includes only a subset of the available literature on a topic. It focuses on key works, seminal text, or authoritative sources based on specific criteria, Unlike comprehensive ones, selective bibliographies prioritize quality over quantity , offering users a curated selection of the most important and influential works within the subject area.

It typically outlines these elements:

- Clearly defining the criteria used to select sources

- Carefully curating a selection of sources

- Excluding sources that do not meet the specified criteria

- May include evaluative annotations or commentary to justify the selection

- Providing guidance to users on how to effectively use it

The subject-specific enumerative type focuses on compiling sources related to a specific subject , catering to the research needs of practitioners, students, and scholars within that domain. They are tailored to the needs and interests of users within a particular specialization .

A subject enumerative comprises the following aspects:

- Organized according to the subject area, facilitating easy access of resources

- Coverage of a broad range of topics within the chosen subject area

- May include thematic categorization or subheadings to further organize it

- Tailored annotations, offering insights into the relevance of each source

Bibliographic Formats

Bibliographies can be formatted in various styles, each with its own set of guidelines for organizing and presenting bibliographic information. In this format, we will provide you with the three most common formats, as well as examples for each.

When writing bibliographies (references) using the APA format, the following steps should be observed:

- At the end of the paper on a new page, “ References ” entitled with center-alignment .

- The references themselves should be left-aligned .

- Subsequent lines need a hanging indent of 1/2 inch.

- Only use the author’s full last name and the initial of the first (and middle) name.

- If there are multiple authors, the names are separated with an ampersand (&).

- Place the date in parentheses .

- Italicize the title of the source material & use sentence case .

- For websites, use the full URL .

Smith, J. (2020). The Impact of Social Media on Adolescent Mental Health: A Comprehensive Analysis. Academic Press.

Last Name, First Name Middle Name. (Publication Date). Title . Publisher. URL.

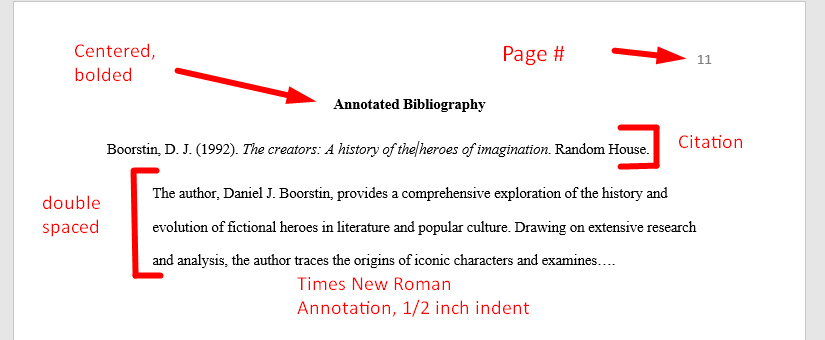

The image below contains an example of an annotated bibliography in APA format.

When writing a bibliography (Works Cited) using MLA, it appears in this format:

- Start “ Works Cited ” list on a new page with center-alignment .

- If you add a Works Consulted list , start it on a new page after Works Cited.

- Each source is left-aligned .

- Alphabetize your sources, usually the author’s last name.

- Full name of the author, last name is mentioned first .

- Remove the https:// of the URL.

Litfin, Karen. “Introduction to Political Economy.” Political Science 203. The University of Washington. Seattle, 2000.

Last Name, First Name Middle Name. Title . Publisher, Date. URL

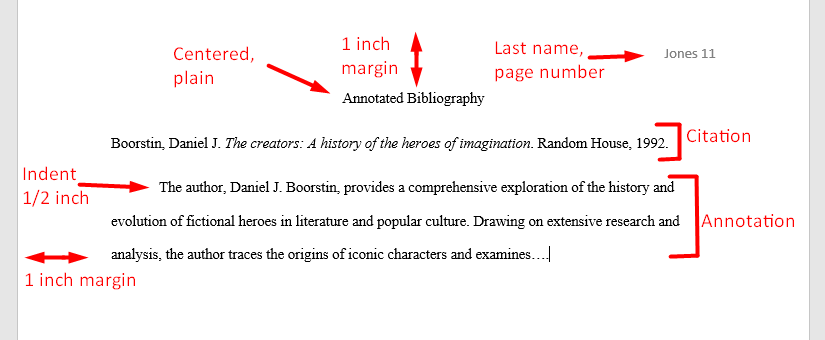

The image below illustrates an example of an annotated bibliography in MLA format.

Chicago Style Format

Here are some general notes on writing a Chicago Style bibliography:

- “Bibliography” or “References” in center-alignment .

- Before the first entry, add t wo blank lines .

- Left-align each entry, 1/2 hanging indent for each subsequent line.

- Single-space entry, with a blank line between each.

- Include the full URL .

Wynn, Stephen. 2020. City of London at War 1939–45 . Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military.

Last Name, First Name Middle Name. Date. Title . City of Publication: Publisher. URL

The image below serves as an example of an annotated bibliography in Chicago format.

What is a bibliography?

A bibliography generally entails the listing of books, articles, websites, and other study materials used to compose a piece of academic writing or literary work. It typically appears at the end of the document and provides readers with detailed information about each source, allowing them to locate and verify the information used by the author.

What is in a bibliography?

A bibliography should include

- The authors’ names

- Date of publication

- Name of publishers and publisher city

- If there are multiple volumes or editions, add page number

- URL if required

What is the difference between bibliographies and a works cited page?

“Works Cited” is a specific term used in MLA citation to refer to a list of sources cited directly in the text, whereas a bibliography includes sources that were consulted, but not directly cited.

What are examples of bibliography?

The exact method and formatting required, will depend on the referencing style that your institution uses.

APA: Last Name, First Name Middle Name. (Publication Date). Title . Publisher. URL.

MLA: Last Name, First Name Middle Name. Title . Publisher, Date. URL

Chicago: Last Name, First Name Middle Name. Date. Title . City of Publication: Publisher. URL

What are the different types of bibliographies?

There are three main types of bibliographies. Check with your institution which method you’re required to use. This may depend on the referencing and citation style you’re using, as well as your field of research.

Analytical: Includes information and new insights that come to light as the book or research paper progresses.

Annotated: Outlines the research that was conducted and provides feedback on specific sources.

Enumerative: A list of sources in a particular order.

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience.

- External Media

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us to understand how our visitors use our website.

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

Privacy Policy Imprint

How to Write a Bibliography for a Research Paper

Do not try to “wow” your instructor with a long bibliography when your instructor requests only a works cited page. It is tempting, after doing a lot of work to research a paper, to try to include summaries on each source as you write your paper so that your instructor appreciates how much work you did. That is a trap you want to avoid. MLA style, the one that is most commonly followed in high schools and university writing courses, dictates that you include only the works you actually cited in your paper—not all those that you used.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, assembling bibliographies and works cited.

- If your assignment calls for a bibliography, list all the sources you consulted in your research.

- If your assignment calls for a works cited or references page, include only the sources you quote, summarize, paraphrase, or mention in your paper.

- If your works cited page includes a source that you did not cite in your paper, delete it.

- All in-text citations that you used at the end of quotations, summaries, and paraphrases to credit others for their ideas,words, and work must be accompanied by a cited reference in the bibliography or works cited. These references must include specific information about the source so that your readers can identify precisely where the information came from.The citation entries on a works cited page typically include the author’s name, the name of the article, the name of the publication, the name of the publisher (for books), where it was published (for books), and when it was published.

The good news is that you do not have to memorize all the many ways the works cited entries should be written. Numerous helpful style guides are available to show you the information that should be included, in what order it should appear, and how to format it. The format often differs according to the style guide you are using. The Modern Language Association (MLA) follows a particular style that is a bit different from APA (American Psychological Association) style, and both are somewhat different from the Chicago Manual of Style (CMS). Always ask your teacher which style you should use.

A bibliography usually appears at the end of a paper on its own separate page. All bibliography entries—books, periodicals, Web sites, and nontext sources such radio broadcasts—are listed together in alphabetical order. Books and articles are alphabetized by the author’s last name.

Most teachers suggest that you follow a standard style for listing different types of sources. If your teacher asks you to use a different form, however, follow his or her instructions. Take pride in your bibliography. It represents some of the most important work you’ve done for your research paper—and using proper form shows that you are a serious and careful researcher.

Bibliography Entry for a Book

A bibliography entry for a book begins with the author’s name, which is written in this order: last name, comma, first name, period. After the author’s name comes the title of the book. If you are handwriting your bibliography, underline each title. If you are working on a computer, put the book title in italicized type. Be sure to capitalize the words in the title correctly, exactly as they are written in the book itself. Following the title is the city where the book was published, followed by a colon, the name of the publisher, a comma, the date published, and a period. Here is an example:

Format : Author’s last name, first name. Book Title. Place of publication: publisher, date of publication.

- A book with one author : Hartz, Paula. Abortion: A Doctor’s Perspective, a Woman’s Dilemma . New York: Donald I. Fine, Inc., 1992.

- A book with two or more authors : Landis, Jean M. and Rita J. Simon. Intelligence: Nature or Nurture? New York: HarperCollins, 1998.

Bibliography Entry for a Periodical

A bibliography entry for a periodical differs slightly in form from a bibliography entry for a book. For a magazine article, start with the author’s last name first, followed by a comma, then the first name and a period. Next, write the title of the article in quotation marks, and include a period (or other closing punctuation) inside the closing quotation mark. The title of the magazine is next, underlined or in italic type, depending on whether you are handwriting or using a computer, followed by a period. The date and year, followed by a colon and the pages on which the article appeared, come last. Here is an example:

Format: Author’s last name, first name. “Title of the Article.” Magazine. Month and year of publication: page numbers.

- Article in a monthly magazine : Crowley, J.E.,T.E. Levitan and R.P. Quinn.“Seven Deadly Half-Truths About Women.” Psychology Today March 1978: 94–106.

- Article in a weekly magazine : Schwartz, Felice N.“Management,Women, and the New Facts of Life.” Newsweek 20 July 2006: 21–22.

- Signed newspaper article : Ferraro, Susan. “In-law and Order: Finding Relative Calm.” The Daily News 30 June 1998: 73.

- Unsigned newspaper article : “Beanie Babies May Be a Rotten Nest Egg.” Chicago Tribune 21 June 2004: 12.

Bibliography Entry for a Web Site

For sources such as Web sites include the information a reader needs to find the source or to know where and when you found it. Always begin with the last name of the author, broadcaster, person you interviewed, and so on. Here is an example of a bibliography for a Web site:

Format : Author.“Document Title.” Publication or Web site title. Date of publication. Date of access.

Example : Dodman, Dr. Nicholas. “Dog-Human Communication.” Pet Place . 10 November 2006. 23 January 2014 < http://www.petplace.com/dogs/dog-human-communication-2/page1.aspx >

After completing the bibliography you can breathe a huge sigh of relief and pat yourself on the back. You probably plan to turn in your work in printed or handwritten form, but you also may be making an oral presentation. However you plan to present your paper, do your best to show it in its best light. You’ve put a great deal of work and thought into this assignment, so you want your paper to look and sound its best. You’ve completed your research paper!

Back to How To Write A Research Paper .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

bibliography

Definition of bibliography

Examples of bibliography in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'bibliography.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.