Design Briefs

Design a record cover.

- Post author By Manuel Schmalstieg

- Post date May 2024

A historical design assignment by Tomás Maldonado, at the Ulm School of Design, presented in 1963 in the magazine Ulm 8/9 .

In the second quarter of the academic year 1962/63, Tomás Maldonado set the following exercise to the first year students of the Visual Communication Department: to design a case for a 33 1/3 r.p.m. gramophone record. The students could choose from records by Mauricio Kagel (Transicion I, Transicion II, Antithese), by Karlheinz Stockhausen (Zyklus) and by Franco Evangelisti. If prefered, however, they could design a case for a record of their own selection. The cases could be designed either in colour or in black and white – as also the circular labels in the centres of the records.

Some of the resulting works by students:

- Tags Music , Ulm School of Design

Ulm Exercises

Some historical design briefs from the legendary Ulm School of Design (1953-1968) were presented during a study project at the Cologne International School of Design in 2002/03, supervised by Gui Bonsiepe (who was editor of the Ulm magazine).

A website was put online in 2002/03. It is still available via the Wayback Machine. Some briefs:

Otl Aicher : Schematische Darstellung komplexer Sachverhalte

Gui Bonsiepe : Einführung in die visuelle Semantik

Tomás Maldonado : hüllen für schallplatten (ulm 8/9)

In this exercise (1962/63), students have to create an album cover for an LP. The works assigned are by composers Mauricio Kagel (Transicion I, Transicion II, Antithese), Karlheinz Stockhausen (Zyklus), and Franco Evangelisti.

Josef Müller-Brockmann : Firmentypografie (ulm 8/9)

Gui Bonsiepe : Perforationen , Topologische Übungen (ulm 17/18)

- Tags Ulm School of Design

write a radio-play

- Post date Mar 2024

This assignment was reverse-engineered from a project description in issue #2 of “Ulm” (1958), the magazine of the Ulm School of Design. The short article describes a team-writing experiment, that was broadcast as a radio-play.

- Make comprehensive preparatory studies in order to shape exactly the characters of the play.

- Compose detailed biographies, diaries, letters, dreams, and scenes of everyday life of the characters.

- Plan the scenes.

- Compose the material into a satiric crime story.

- Tags Ulm School of Design , writing

Bring an object

- Post date Dec 2023

Jarret Fuller, designer and teacher, writes on his blog :

I was inspired by my conversation with Sam Jacob and adapted a framework he’s used in the writing classes he’s taught. For the first half of the class, the students had to bring in a single object, that cost no more than $30, to write about. Each week, they wrote about their object through a different lens: aesthetic/formal qualities, historical and contextual, and finally ideological. We weren’t too interested in voice yet, just how to talk about these objects and what they can tell us about design, culture, economics, etc. In the second half of the class, we used what we learned and added a variety of writing tricks to them: thinking about voice and tone, how can we play with structure, tell a new story. Throughout the semester, I was continually impressed with what the students brought — they took these objects they didn’t think they could write about and suddenly we were talking about immigration, class, identity, race, sustainability… It was so fun.

- Tags writing

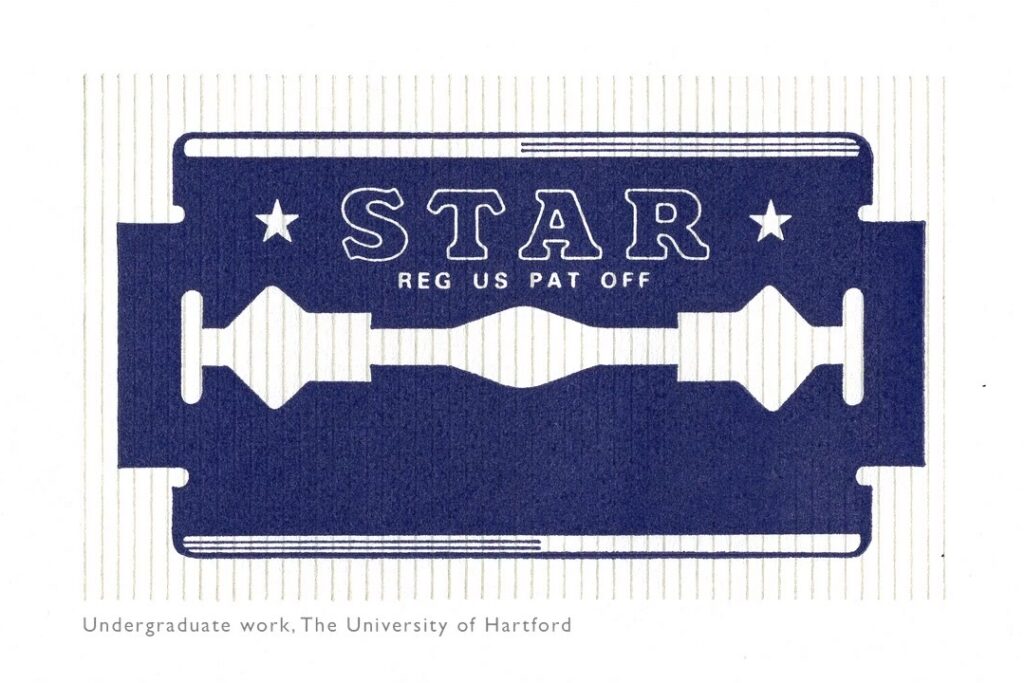

Recreate a label from scratch

An assignment by Inge Druckrey, described in the movie “Teaching to See” (minutes 7:04 to 8:30):

I had collected over time some beautiful old labels. So I distributed them among the students, and asked them to create a new edition. They had to: recreate the letters on the label. draw any image that appeared on the label. prepare color-separation to have hot metal plates done. mix the ink. print the labels in proper registration on a small letter press.

So they learned about designing letters, they matched the letters on the original label, they designed the marks from scratch, carefully matching the same quality. They learned about color separation, how to get the individual colors on separate hot metal plates, about ink mixing, and the printing itself. And the students loved the project, because it had a clear goal.

Note: the assignment was done before computers became available.

- Tags graphic design , printing , typography

Create a BookTok video

- Post date Nov 2023

Students get assigned a literary work, and have to create a short promotional video. The aim is to get viral and improve book sales.

Note: BookTok is a subcommunity on the app TikTok that focuses on books and literature.

- Tags social media , video

explore a WordPress pattern in seven ways

- Post date Feb 2023

This assignments is based on a blog post by WordPress theme designer Rich Tabor: Exploring WordPress as a design tool (December 2022). Rich writes:

Last week I challenged myself to take one pattern, from one theme, and morph it multiple times — only using the design controls block editor. It’s kind of like CSS Zen Garden , but without CSS — just out-of-the-box WordPress block design tooling. One theme. One pattern. Seven ways. No additional blocks, nor custom CSS between scenes — just designing in the good ol’ WordPress block editor. Every font family/size, color, border, radius, image, video, and spacing value were are all added in-editor.

- Tags interface design , speed project , web design , WordPress

Assignment : Wait

An assignment by David Reinfurt, in his 2022 course in the Visual Arts Program at Princeton University, “ Gestalt “:

Design an animated graphic that means “Wait.”

The result is an animation designed for an electronic screen. Read more detail on the dedicated website . This assignment is also featured in Reinfurt’s 2019 book “A New Program for Graphic Design” (p. 133).

- Tags animation , icon design

Assignment : Stop

An assignment by David Reinfurt, in his 2022 course in the Visual Arts Program at Princeton University, “ Gestalt “:

Design an autonomous graphic form that means “Stop.”

More information at the dedicated website .

In Reinfurt’s 2019 book “A New Program for Graphic Design”, the “Stop” assignment is broadened by including also a “Go” sign.

As with the Stop sign, the Go sign must not rely on symbolic, graphic, or literal conventions. The Go sign will be directly related to, and dependent on, the form of the Stop sign.

- Tags graphic design , symbols

- Post date Nov 2022

The Noun Project – a crowdsourced library of icons available for free on the website NounProject.org – has partnered in 2011 with Code for America to offer “Iconathons” and “Icon Camps”. “Traveling through six U.S. cities, Noun Project founder Edward Boatman conducted daylong workshops bringing together designers, civic leaders, and city staffers to design new urban symbols”.

In a 2012 interview , Boatman explains:

Our Iconathons are a series of design workshops, and their goal is essentially to create civic-minded symbols for the public domain. What we do is run a group design workshop, where we invite designers, subject matter experts, and citizens who really care about their environment and their community. So we invite citizens into this process who have no design experience. What’s great is that non-designers can really add value to this process. We keep the execution level just to pencil and paper. Keeping it to a pen and paper, it’s all about ideas. We design these symbols in a group, and we talk about which symbols best communicate certain concepts. Then after the event, I work with a series of graphic designers to take those sketches and turn them into vectors. With this process we’ve produced about 55 symbols to date. Last year we held them Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, Chicago, and Boston, and each Iconathon had a different theme. The Los Angeles one was food policy. The L.A. county food policy heads came to the Iconathon, and they really helped inform the process by telling us: This how the symbols could be used. This is why they’re powerful tools. This is how they help solve problems. They really helped inform the process.

Read a report by Kat Lau, intern at the San Francisco Office of Civic Innovation in 2012.

Also featured in Ellen Lupton’s “Type on Screen”:

In Baltimore a team of designers from MICA paired up with city leaders to create icons focusing on food, health and community.

- Tags icon design , open source , public domain

- Arts & Photography

- Decorative Arts & Design

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

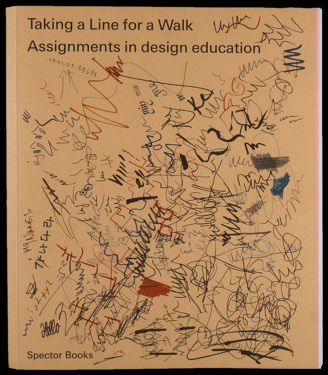

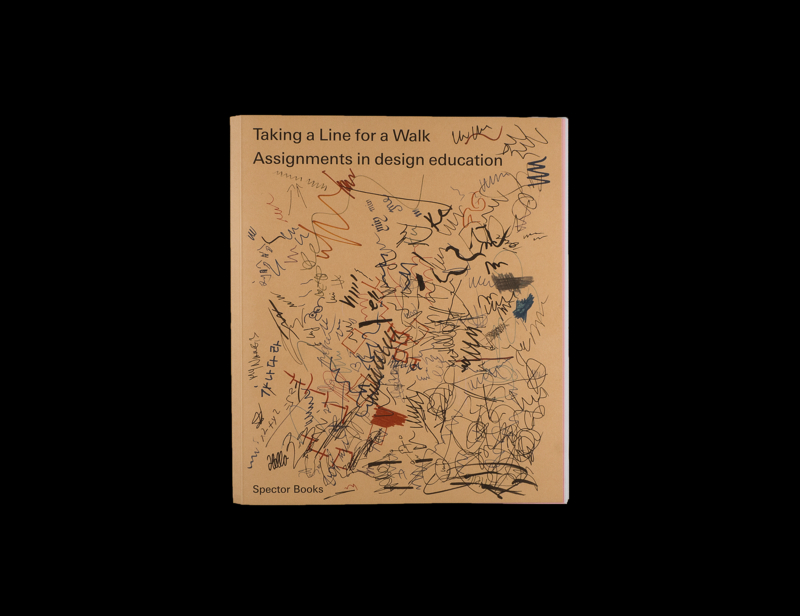

Taking a Line for a Walk: Assignments in design education Paperback – January 9, 2016

- Print length 224 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Spector Books

- Publication date January 9, 2016

- Dimensions 8.6 x 0.8 x 10 inches

- ISBN-10 395905081X

- ISBN-13 978-3959050814

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Product details

- Publisher : Spector Books (January 9, 2016)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 224 pages

- ISBN-10 : 395905081X

- ISBN-13 : 978-3959050814

- Item Weight : 1.7 pounds

- Dimensions : 8.6 x 0.8 x 10 inches

- #419 in Design History & Criticism

- #2,139 in Graphic Design Techniques

About the author

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top review from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Taking a Line for a Walk Assignments in design education (Reprint) Nina Paim

272 pp. black-white images Wire-o with softcover in reverse binding Leipzig February, 2021 ISBN: 9783959050814 Edition Number: 2 Width: 22 cm Length: 25.5 cm Language(s): English Editor Nina Paim Designer Nina Paim, Corinne Gisel Co-Editor Emilia Bergmark Text Corinne Gisel

Related books

Your cart -

- 0"> −

Taxes and shipping calculated at checkout

- Create account

Taking a Line for a Walk: Assignments in Design Education

Deriving its title from the Paul Klee’s pedagogical sketchbook of the same name written in 1925, Taking a Line for a Walk focuses on the use of language in design education through the lens of the assignment, showcasing close to 300 contemporary and historical assignments ranging from the Renaissance up to the present including Eugene Grasset’s Méthode de Composition Ornamentale from 1905 and British graphic designer Ken Garland’s game Connect created in 1969.

This rich collection provides an overview of the development and evolving approaches to graphic design instruction. Conceived by Nina Paim and designed in collaboration with Emilia Bergmark, the book also includes two essays by designer, photographer, and writer Corinne Gisel, looking at the assignment as a teaching tool and linguistic artifact.

Taking a Line is the first installment of a trilogy of books on modes of design education, expanding from their exhibition at the International Biennial of Graphic Design, Brno 2014, Czech Republic.

Designed by Corinne Gisel and Nina Paim

Published by Spector Books, 2021 Second edition

272 pages, single color, concealed Wire-O case binding, 8.5 × 10 inches

ISBN 978-3-95905-081-4

Stay connected. Sign up for the Draw Down Newsletter.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Press the space key then arrow keys to make a selection.

Taking a Line for a Walk: Assignments in Design Education

In 2014, we were asked to submit some of our favorite assignments to be included in the 26th International Biennial of Graphic Design Brno. These assignments later appeared in Taking a Line for a Walk: Assignments in Design Education edited by Nina Paim and Emilia Bergmark in 2016.

Assignments included:

Human Algorithm (with Neil Donnelly) With a partner, devise a set of instructions of at least ten steps to carry out a task. The task could be something utterly commonplace and practical, or outlandish, unprecedented, and absurd. Use “if”, “if/else” (i.e., “if this, then that; or else, do this”), “while”, or “for” statements as needed to anticipate unpredictable conditions or decisions…

Stories as Networks (with Neil Donnelly) Jorge Luis Borges was an Argentinian writer famous for his short stories that deal with labyrinths, dreams, religion, and mathematical ideas (particularly set theory concepts like infinity and cardinality). His circuitous and meandering prose, full of allusions and vivid imagery, is a good way to think about the Web as a network that has many nodes and many connections, and that continuously folds upon itself. It is the act of navigating through this maze that brings meaning to the Web experience…

Meaning in Multiples (with Julian Bittiner) Collections help us to filter and make sense of the world. Through the act of collecting, we develop a more critical eye. We compare and contrast, define patterns and anomalies, form judgements and develop preferences…

Source: Excerpts from Taking a Line for a Walk: Assignments in Design Education by Nina Paim and Emilia Bergmark published by Spector Books (2016), Tags: Form Making, Interaction Design, Pedagogy

Facebook Twitter

Previous—

L’importanza del curriculum, next—, present continuous: thoughts on chinese typography.

Design Education Resources

AIGA supports education throughout the arc of a designer’s career, including special programs for educators, a group critical to advancing the profession.

AIGA Design Teaching Resource

The AIGA Design Teaching Resource is a peer-populated platform for educators to share assignments, teaching materials, outcomes, and project reflections.

- AIGA Design Educators Community

The DEC Steering Committee is comprised of 13 dedicated educators providing service and leadership to the Community.

Meet the committee

Dialectic seeks to publish scholarship, analytical study and criticism that will enlighten and inform a diverse audience of design educators engaged not only in classroom teaching experiences but also in differing forms of research and professional practice. It is open access, double-blind-peer reviewed, and the official journal of the AIGA Design Educators Community (DEC).

Access past issues

NASAD and Accreditation

The AIGA & NASAD briefing papers address various aspects of graphic design education and are directed towards a number of different audiences.

Read the briefing papers

Professional Standards of Teaching

A design educator adheres to values that demonstrate respect for students, other educators, academic institutions, the profession, the public, society and the environment. These standards define the expectations of a design educator and represent the distinction of an AIGA member teaching design.

Bibliographies

These bibliographies for design educators and students address an eclectic array of topics: Cognition and Emotion, Cultural Studies, Design Planning, Education and Learning Theory and Interaction and New Media Design.

View the bibliographies

Design Futures

This research project examines seven trends shaping the context for the practice of design. This change in the nature of work calls for new skills and perspectives beyond traditional college-level design education. It is critical that the industry expands its knowledge and expertise to remain economically viable and professionally relevant as it prepares for changing client demands and new opportunities for design influence.

Read the trends

Dialogue is the ongoing series of fully open-access proceedings of the conferences and national symposia of the AIGA Design Educators Community (DEC). Issues of Dialogue contain papers from DEC conferences that focus on topics affecting design education, research, and professional practice, although each conference varies in theme. Michigan Publishing, the hub of scholarly publishing at the University of Michigan, publishes Dialogue on behalf of the AIGA DEC.

Promotion and Tenure

The purpose of this resource is to provide guidance to those involved with Promotion and Tenure (P&T) processes of Graphic Design and Visual Communication Design Educators at US institutions of higher learning. It is not meant to address all possible topics and issues related to the P&T process, but should assist in dealing with issues commonly involved in the P&T process, and will provide suggestions on which policies and procedures may be based, at the discretion of the institution.

Guide to Internships

AIGA believes that quality internships provide an invaluable stepping stone towards professional practice and create continuity within the design profession. We thank those who open their doors to young designers and generously share their knowledge and experience with the next generation of design practitioners.

High School Design Curriculum

This four-unit graphic curriculum has been created specifically for high school educators. Areas addressed include An Introduction to Graphic Design, 2D Design Basics, Design Process, and Typography, as well as a glossary and supporting handouts. Created by AIGA Minnesota with support from AIGA Innovate.

Download the curriculum

Additional Teaching Resources

WRITING A SYLLABUS

Published by Jossey-Bass

The Course Syllabus, A Learning Centered Approach, Second Edition

Chronicle of Higher Education

How to Create a Syllabus

Steven Heller

Teaching Graphic Design: Course Offerings and Class Projects from the Leading Graduate and Undergraduate Programs

CREATING A RUBRIC

Robin Landa

A Case for Using a Rubric

Karen Cheng

How to Survive Critique: A Guide to Giving and Receiving Feedback—Part 1

How to survive critique—part 2.

Yoon Soo Lee

Functional Criticism— How to Have Productive Critiques in the Creative Classroom

TEACHING ASSISTANTS

John Bowers

Handbook for Teaching Assistants

COLLABORATION

Marty Maxwell Lane and Rebecca Tegtmeyer

Collab + Design Ed: Collaboration in Design Education

Chad Hall and Jp Avila

This is Design School

David Airey

Advice for Design Students

Adrian Shaughnessy

How to be a Graphic Designer Without Losing Your Soul

PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE

Emily Ruth Cohen

Brutally Honest: No Bullshit Strategies To Evolve Your Creative Business

Ted Leonhardt

Nail It: Stories for Designers on Negotiating with Confidence

BUILDING PORTFOLIOS

Bryony Gomez-Palacio and Armin Vit

Simon & Schuster

Build Your Own Brand

Juliette Cezzar

AIGA Career Guide

CURRICULUM / PEDAGOGY

Meredith Davis

Teaching Design: A Guide to Curriculum and Pedagogy for College Design Faculty and Teachers Who Use Design in Their Classrooms

The education of a graphic designer.

ASSIGNMENTS

Spector Books

Taking a Line for a Walk: Assignments in Design Education

Edited by Linda van Deursen

37 Assignments

Teaching graphic design.

FOUNDATIONS

Ellen Lupton and Jennifer Cole Phillips

Graphic Design: The New Basics

Graphic design solutions, 6th edition, visual communication design: an introduction to design concepts in everyday experience.

Robin Landa, Rose Gonnella, and Steven Brower

2D: Visual Basics for Designers

Jason Santa Maria

A Book Apart: On Web Typography

Simon Garfield

Just My Type: A Book About Fonts

Designing type.

Robert Bringhurst

Elements of Typographic Style

Matej Latin

Better Web Typography for a Better Web

Ellen Lupton

Thinking With Type

A type primer.

Timothy Samara

Making and Breaking the Grid, Second Edition, Updated and Expanded: A Graphic Design Layout Workshop

Josef Müller-Brockman

Grid systems in graphic design: A visual communication manual for graphic designers, typographers and three dimensional designers

Graphic design theory (graphic design in context) first edition.

Helen Armstrong

Graphic Design Theory: Readings from the Field

Rose Gonnella and Max Friedman

Design Fundamentals: Notes on Color

The designer’s dictionary of color.

Website Planet.com

30 Stats and Logo Facts

INCLUSIVE DESIGN

Ellen Lupton and Andrea Lipps

The Senses: Design Beyond Vision

Mismatch: how inclusion shapes design (simplicity: design, technology, business, life).

Scott Barry Kaufman and Carolyn Gregoire

Wired to Create: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Creative Mind

The storm of creativity (simplicity: design, technology, business, life).

Rosanne Somerson and Mara Hermano

The Art of Critical Making: Rhode Island School of Design on Creative Practice

INTERACTION/INTERFACE DESIGN

Don’t Make Me Think, Revisited: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability

Thoughts on interaction design.

DESIGN HISTORY

Graphic Design, Referenced: A Visual Guide to the Language, Applications, and History of Graphic Design

Teaching graphic design history.

Phillip B Meggs

Megg’s History of Graphic Design 6th Edition

Steven Heller and Véronique Vienne

100 Ideas That Changed Graphic Design

Richard Poulin

Graphic Design and Architecture, A 20th Century History: A Guide to Type, Image, Symbol, and Visual Storytelling in the Modern World

MOTION DESIGN

Editors R. Brian Stone, Leah Walin; Routledge: 2018

The Theory and Practice of Motion Design: Critical Perspectives and Professional Practice

Beth Costello

The Art of the Process: Establishing Good Habits for Successful Outcomes

THE ROLE OF THE DESIGNER

Steven McCarthy

The Designer As…

Citizen designer.

Noah Scalin

The Design Activists Handbook

THINKING/WRITING

Writing and Research for Graphic Designers: A Designer’s Manual to Strategic Communication and Presentation

Design is storytelling, graphic design thinking (design briefs), related videos.

Student-Run Design Studios

A panel and discussion about the logistics and pedagogy of student-run design studios, facilitated by Jessica Jacobs and Meaghan Dee.

Concepts of Affordance

How might design educators apply concepts of affordance into their design courses? This event was a roundtable format with introductory presentations from our guests followed by active discussions by our participants.

International Design Collaborations

A panel discussion about international design collaborations, exploring lessons and experiences.

The Value of Design Education

A panel discussion exploring questions like: What value do we provide as design educators? How do we measure or demonstrate that value? (To ourselves, our students, our institutions) and, We can’t recreate in-person experiences online. So, what are reasonable expectations to set for ourselves? For our students?

Engage & Learn

- AIGA Membership

- AIGA Design Conference

- Career, Jobs, & Projects

- National Partner Program

- Sponsorship & Advertising

Sign-up for our newsletter

228 Park Ave S, Suite 58603 New York, NY 10003

© 2024 AIGA

- UAL Research

Taking a Line for a Walk: Assignments in design education

- UAL Research Centre

- Research type

- File format

- Login (to deposit)

- Email Research Online

- UAL Research Management

- Scholarly Communications

Repository Staff Only: item control page | University Staff: Request a correction

School of Art, Media, and Technology

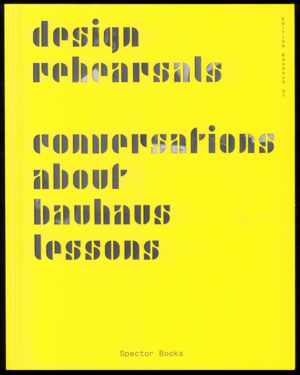

Taking a line for a walk conversations #4: the real assignment.

Tue, December 6, 2016

7:00 PM – 9:00 PM

The New School | Parsons School of Design

66 West 12th Street

Klein Conference Room, A 510

New York, New York 10011

The relationship between education and professional practice is a rather complicated one. While education is often considered a training ground, professional practice is commonly described as the actual battle field. But is that really true? Isn’t education a real thing in itself? What, then, is the nature of student work? Is it real, fake or fictional? What are the benefits and pitfalls of assignments that emulate professional conditions? What are the positives and negatives of so-called “useless” assignments? What does it mean to bring actual clients into a school environment? When does design education become exploitive? When is design education emancipatory? When is it visionary? Or reactionary? When is education pragmatic? Or hermetic? When is it actually realistic?

If you’re a TNS student and would like to receive complimentary tickets, RSVP here .

For general public, RSVP here .

Julian Bittiner, Senior Critic, Yale University School of Art

Neil Donnelly, Part-Time Lecturer BFA Communication Design, Parsons School of Design

Rob Giampietro, Senior Critic, Rhode Island School of Design

YuJune Park, Director & Assistant Professor BFA Communication Design, Parsons School of Design

Amy Papaelias, Assistant Professor Graphic Design Program, State University of New York at New Paltz

Mediated by:

Nina Paim and Corinne Gisel

This conversation is part of a series of events investigating current issues in design education in relation to giving, writing, and preserving assignments, initiated by the authors of the book Taking a Line for a Walk, published by Spector Books Leipzig in 2016.

Assignments can give instructions, describe an exercise, present a problem, set out rules, propose a game, stimulate a process, or simply throw out questions. Taking a Line for a Walk brings attention to something that is often neglected: the assignment as a pedagogical element and verbal artefact of design education. This book is a compendium of 224 assignments, edited by Nina Paim and coedited by Emilia Bergmark. A reference book for educators, researchers, and students alike, it includes both contemporary and historical examples and offers a space for different lines of design pedagogy to converge and converse. An accompanying essay by Corinne Gisel takes a closer look at the various forms assignments can take and the educational contexts they exist within. Taking a Line for a Walkderived from an exhibition of the same name at the International Biennial of Graphic Design Brno 2014.

Taking a Line for a Walk: Assignments in design education Conceived by Nina Paim, Corinne Gisel, and Emilia Bergmark Spector Books Leipzig 2016

Purchase the book HERE

- Announcements

- Exhibitions

- Film Screening

- Illustration Dept. Events

- Momentum Alumni Lectures

- Presentation

- Talks/Lectures

- Visiting Lecture Series

- Communication Design | BFA

- Communication Design | MPS

- Data Visualization | MS

- Design and Technology | BFA

- Design and Technology | MFA

- Fine Arts | BFA

- Fine Arts | MFA

- Graphic Design | AAS

- Illustration | BFA

- Photography | BFA

- Photography | MFA

- Printmaking

School of Design Strategies

- Arturo Escobar

- Ezio Manzini

- Lori Adelman

School of Constructed Environments

Parsons undergraduate blog.

- First Year IS2 students out and about!

- Parsons First Year Journal Launch Party & Reading!

- CREATING COMMUNITY FROM THE GET GO

School of Art and Design History and Theory

- PLDS 4075, Design for Aging Populations, visits 305 West End Avenue

- A New Book by ADHT’s Petya Andreeva | Fantastic Fauna From China to Crimea: Image-Making in Eurasian Nomadic Societies, 700 BCE-500 CE

- A New Book by ADHT’s Jilly Traganou | Design, Displacement, Migration: Spatial and Material Histories

School of Fashion

- BFA Fashion

- AAS Fashion

- MFA Fashion Design & Society

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Getting Started with Creative Assignments

Creative teaching and learning can be cultivated in any course context to increase student engagement and motivation, and promote thinking skills that are critical to problem-solving and innovation. This resource features examples of Columbia faculty who teach creatively and have reimagined their course assessments to allow students to demonstrate their learning in creative ways. Drawing on these examples, this resource provides suggestions for creating a classroom environment that supports student engagement in creative activities and assignments.

On this page:

- The What and Why of Creative Assignments

Examples of Creative Teaching and Learning at Columbia

- How To Get Started

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2022). Getting Started with Creative Assignments. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/creative-assignments/

The What and Why of Creative Assignments

Creative assignments encourage students to think in innovative ways as they demonstrate their learning. Thinking creatively involves combining or synthesizing information or course materials in new ways and is characterized by “a high degree of innovation, divergent thinking, and risk-taking” (AAC&U). It is associated with imagination and originality, and additional characteristics include: being open to new ideas and perspectives, believing alternatives exist, withholding judgment, generating multiple approaches to problems, and trying new ways to generate ideas (DiYanni, 2015: 41). Creative thinking is considered an important skill alongside critical thinking in tackling contemporary problems. Critical thinking allows students to evaluate the information presented to them while creative thinking is a process that allows students to generate new ideas and innovate.

Creative assignments can be integrated into any course regardless of discipline. Examples include the use of infographic assignments in Nursing (Chicca and Chunta, 2020) and Chemistry (Kothari, Castañeda, and McNeil, 2019); podcasting assignments in Social Work (Hitchcock, Sage & Sage, 2021); digital storytelling assignments in Psychology (Sheafer, 2017) and Sociology (Vaughn and Leon, 2021); and incorporating creative writing in the economics classroom (Davis, 2019) or reflective writing into Calculus assignment ( Gerstle, 2017) just to name a few. In a 2014 study, organic chemistry students who elected to begin their lab reports with a creative narrative were more excited to learn and earned better grades (Henry, Owens, and Tawney, 2015). In a public policy course, students who engaged in additional creative problem-solving exercises that included imaginative scenarios and alternative solution-finding showed greater interest in government reform and attentiveness to civic issues (Wukich and Siciliano, 2014).

The benefits of creative assignments include increased student engagement, motivation, and satisfaction (Snyder et al., 2013: 165); and furthered student learning of course content (Reynolds, Stevens, and West, 2013). These types of assignments promote innovation, academic integrity, student self-awareness/ metacognition (e.g., when students engage in reflection through journal assignments), and can be made authentic as students develop and apply skills to real-world situations.

When instructors give students open-ended assignments, they provide opportunities for students to think creatively as they work on a deliverable. They “unlock potential” (Ranjan & Gabora and Beghetto in Gregerson et al., 2013) for students to synthesize their knowledge and propose novel solutions. This promotes higher-level thinking as outlined in the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy’s “create” cognitive process category: “putting elements together to form a novel coherent whole or make an original product,” this involves generating ideas, planning, and producing something new.

The examples that follow highlight creative assignments in the Columbia University classroom. The featured Columbia faculty taught creatively – they tried new strategies, purposefully varied classroom activities and assessment modalities, and encouraged their students to take control of what and how they were learning (James & Brookfield, 2014: 66).

Dr. Cruz changed her course assessment by “moving away from high stakes assessments like a final paper or a final exam, to more open-ended and creative models of assessments.” Students were given the opportunity to synthesize their course learning, with options on topic and format of how to demonstrate their learning and to do so individually or in groups. They explored topics that were meaningful to them and related to the course material. Dr. Cruz noted that “This emphasis on playfulness and creativity led to fantastic final projects including a graphic novel interpretation, a video essay that applied critical theory to multiple texts, and an interactive virtual museum.” Students “took the opportunity to use their creative skills, or the skills they were interested in exploring because some of them had to develop new skills to produce these projects.” (Dr. Cruz; Dead Ideas in Teaching and Learning , Season 3, Episode 6). Along with their projects, students submitted an artist’s statement, where they had to explain and justify their choices.

Dr. Cruz noted that grading creative assignments require advanced planning. In her case, she worked closely with her TAs to develop a rubric that was shared with students in advance for full transparency and emphasized the importance of students connecting ideas to analytical arguments discussed in the class.

Watch Dr. Cruz’s 2021 Symposium presentation. Listen to Dr. Cruz talk about The Power of Blended Classrooms in Season 3, Episode 6 of the Dead Ideas in Teaching and Learning podcast. Get a glimpse into Dr. Cruz’s online classroom and her creative teaching and the design of learning experiences that enhanced critical thinking, creativity, curiosity, and community by viewing her Voices of Hybrid and Online Teaching and Learning submission.

As part of his standard practice, Dr. Yesilevskiy scaffolds assignments – from less complex to more complex – to ensure students integrate the concepts they learn in the class into their projects or new experiments. For example, in Laboratory 1, Dr. Yesilevskiy slowly increases the amount of independence in each experiment over the semester: students are given a full procedure in the first experiment and by course end, students are submitting new experiment proposals to Dr. Yesilevskiy for approval. This is creative thinking in action. Students not only learned how to “replicate existing experiments, but also to formulate and conduct new ones.”

Watch Dr. Yesilevskiy’s 2021 Symposium presentation.

How Do I Get Started?: Strategies to Support Creative Assignments

The previous section showcases examples of creative assignments in action at Columbia. To help you support such creative assignments in your classroom, this section details three strategies to support creative assignments and creative thinking. Firstly, re-consider the design of your assignments to optimize students’ creative output. Secondly, scaffold creative assignments using low-stakes classroom activities that build creative capacity. Finally, cultivate a classroom environment that supports creative thinking.

Design Considerations for Creative Assignments

Thoughtfully designed open-ended assignments and evaluation plans encourage students to demonstrate their learning in authentic ways. When designing creative assignments, consider the following suggestions for structuring and communicating to your students about the assignment.

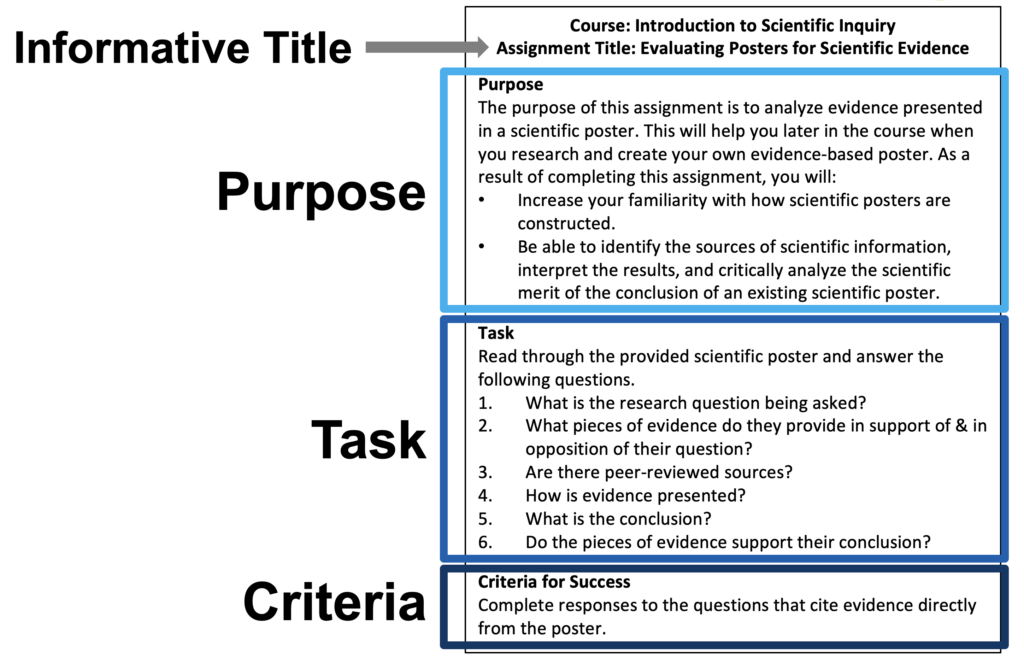

Set clear expectations . Students may feel lost in the ambiguity and complexity of an open-ended assignment that requires them to create something new. Communicate the creative outcomes and learning objectives for the assignments (Ranjan & Gabora, 2013), and how students will be expected to draw on their learning in the course. Articulare how much flexibility and choice students have in determining what they work on and how they work on it. Share the criteria or a rubric that will be used to evaluate student deliverables. See the CTL’s resource Incorporating Rubrics Into Your Feedback and Grading Practices . If planning to evaluate creative thinking, consider adapting the American Association of Colleges and Universities’ creative thinking VALUE rubric .

Structure the project to sustain engagement and promote integrity. Consider how the project might be broken into smaller assignments that build upon each other and culminate in a synthesis project. The example presented above from Dr. Yesilevskiy’s teaching highlights how he scaffolded lab complexity, progressing from structured to student-driven. See the section below “Activities to Prepare Students for Creative Assignments” for sample activities to scaffold this work.

Create opportunities for ongoing feedback . Provide feedback at all phases of the assignment from idea inception through milestones to completion. Leverage office hours for individual or group conversations and feedback on project proposals, progress, and issues. See the CTL’s resource on Feedback for Learning . Consider creating opportunities for structured peer review for students to give each other feedback on their work. Students benefit from learning about their peers’ projects, and seeing different perspectives and approaches to accomplishing the open-ended assignment. See the CTL’s resource Peer Review: Intentional Design for Any Course Context .

Share resources to support students in their work. Ensure all students have access to the resources they will need to be successful on the assigned project. Connect students with campus resources that can help them accomplish the project’s objectives. For instance, if students are working on a research project – connect them to the Library instruction modules “ From Books to Bytes: Navigating the Research Ecosystem ,” encourage them to schedule a consultation with a specialist for research support through Columbia Libraries , or seek out writing support. If students will need equipment to complete their project, remind them of campus resources such as makerspaces (e.g., The Makerspace @ Columbia in Room 254 Engineering Terrace/Mudd; Design Center at Barnard College); borrowing equipment (e.g., Instructional Media and Technology Services (IMATS) at Barnard; Gabe M. Wiener Music & Arts Library ).

Ask students to submit a self-reflection with their project. Encourage students to reflect on their process and the decisions they made in order to complete the project. Provide guiding questions that have students reflect on their learning, make meaning, and engage their metacognitive thinking skills (see the CTL’s resource of Metacognition ). Students can be asked to apply the rubric to their work or to submit a creative statement along with their work that describes their intent and ownership of the project.

Collect feedback from students and iterate. Invite students to give feedback on the assigned creative project, as well as the classroom environment and creative activities used. Tell students how you will use their suggestions to make improvements to activities and assignments, and make adjustments to the classroom environment. See the CTL’s resource on Early and Mid-Semester Student Feedback .

Low-Stakes Activities to Prepare Students for Creative Assignments

The activities described below are meant to be scaffolded opportunities leading to a larger creative project. They are low-stakes, non-graded activities that make time in the classroom for students to think, brainstorm, and create (Desrochers and Zell, 2012) and prepare them to do the creative thinking needed to complete course assignments. The activities can be adapted for any course context, with or without the use of technology, and can be done individually or collaboratively (see the CTL’s resource on Collaborative Learning to explore digital tools that are available for group work).

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a process that students can engage in to generate as many ideas as possible related to a topic of study or an assignment topic (Sweet et al., 2013: 87). As they engage in this messy and jugement-free work, students explore a range of possibilities. Brainstorming reveals students’ prior knowledge (Ambrose et al., 2010: 29). Brainstorm activities are useful early on to help create a classroom culture rooted in creativity while also serving as a potential icebreaker activity that helps instructors learn more about what prior knowledge and experiences students are bringing to the course or unit of study. This activity can be done individually or in groups, and in class or asynchronously. Components may include:

- Prompt students to list off (individually or collaboratively) their ideas on a whiteboard, free write in a Google Doc or some other digital space.

- Provide formative feedback to assist students to further develop their ideas.

- Invite students to reflect on the brainstorm process, look over their ideas and determine which idea to explore further.

Mind mapping

A mind map, also known as a cognitive or concept map, allows students to visually display their thinking and knowledge organization, through lines connecting concepts, arrows showing relationships, and other visual cues (Sweet et al., 2013: 89; Ambrose et al. 2010: 63). This challenges students to synthesize and be creative as they display words, ideas, tasks or principles (Barkley, 2010: 219-225). A mind mapping activity can be done individually or in groups, and in class or asynchronously. This activity can be an extension of a brainstorming session, whereby students take an idea from their brainstormed list and further develop it.

Components of a mind mapping activity may include:

- Prompt students to create a map of their thinking on a topic, concept, or question. This can be done on paper, on a whiteboard, or with digital mind mapping or whiteboard tools such as Google Drawing.

- Provide formative feedback on the mind maps.

- Invite students to reflect on their mind map, and determine where to go next.

Digital storytelling

Digital storytelling involves integrating multimedia (images, text, video, audio, etc.) and narrative to produce immersive stories that connect with course content. Student-produced stories can promote engagement and learning in a way that is both personal and universal (McLellan, 2007). Digital storytelling contributes to learning through student voice and creativity in constructing meaning (Rossiter and Garcia, 2010).

Tools such as the CTL-developed Mediathread as well as EdDiscussion support collaborative annotation of media objects. These annotations can be used in writing and discussions, which can involve creating a story. For freeform formats, digital whiteboards allow students to drop in different text and media and make connections between these elements. Such storytelling can be done collaboratively or simply shared during class. Finally, EdBlogs can be used for a blog format, or Google Slides if a presentation format is better suited for the learning objective.

Asking questions to explore new possibilities

Tap into student imagination, stimulate curiosity, and create memorable learning experiences by asking students to pose “What if?” “why” and “how” questions – how might things be done differently; what will a situation look like if it is viewed from a new perspective?; or what could a new approach to solving a problem look like? (James & Brookfield, 2014: 163). Powerful questions are open-ended ones where the answer is not immediately apparent; such questions encourage students to think about a topic in new ways, and they promote learning as students work to answer them (James & Brookfield, 2014: 163). Setting aside time for students to ask lots of questions in the classroom and bringing in questions posed on CourseWorks Discussions or EdDiscussion sends the message to students that their questions matter and play a role in learning.

Cultivate Creative Thinking in the Classroom Environment

Create a classroom environment that encourages experimentation and thinking from new and diverse perspectives. This type of environment encourages students to share their ideas without inhibition and personalize the meaning-making process. “Creative environments facilitate intentional acts of divergent (idea generation, collaboration, and design thinking) and convergent (analysis of ideas, products, and content created) thinking processes.” (Sweet et al., 2013: 20)

Encourage risk-taking and learning from mistakes . Taking risks in the classroom can be anxiety inducing so students will benefit from reassurance that their creativity and all ideas are welcome. When students bring up unexpected ideas, rather than redirecting or dismissing, seize it as an opportunity for a conversation in which students can share, challenge, and affirm ideas (Beghetto, 2013). Let students know that they can make mistakes, “think outside of the box” without penalty (Desrochers and Zell, 2012), and embrace failure seeing it as a learning opportunity.

Model creative thinking . Model curiosity and how to ask powerful questions, and encourage students to be curious about everything (Synder et al., 2013, DiYanni, 2015). Give students a glimpse into your own creative thinking process – how you would approach an open-ended question, problem, or assignment? Turn your own mistakes into teachable moments. By modeling creative thinking, you are giving students permission to engage in this type of thinking.

Build a community that supports the creative classroom environment. Have students get to know and interact with each other so that they become comfortable asking questions and taking risks in front of and with their peers. See the CTL’s resource on Community Building in the Classroom . This is especially important if you are planning to have students collaborate on creative activities and assignments and/or engage in peer review of each other’s work.

Plan for play. Play is integral to learning (Cavanagh, 2021; Eyler, 2018; Tatter, 2019). Play cultivates a low stress, high trust, inclusive environment, as students build relationships with each. This allows students to feel more comfortable in the classroom and motivates them to tackle more difficult content (Forbes, 2021). Set aside time for play (Ranjan & Gabora, 2013; Sinfield, Burns, & Abegglen, 2018). Design for play with purpose grounded in learning goals. Create a structured play session during which students experiment with a new topic, idea, or tool and connect it to curricular content or their learning experience. Play can be facilitated through educational games such as puzzles, video games, trivia competitions, scavenger hunts or role-playing activities in which students actively apply knowledge and skills as they act out their role (Eyler, 2018; Barkley, 2010). For an example of role-playing games explore Reacting to the Past , an active learning pedagogy of role-playing games developed by Mark Carnes at Barnard College.

The CTL is here to help!

CTL consultants are happy to support instructors as they design activities and assignments that promote creative thinking. Email [email protected] to schedule a consultation.

Ambrose et al. (2010). How Learning Works: 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Barkley, E. F., Major, C. H., and Cross, K. P. (2014). Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty .

Barkley, E. F. (2010) Student Engagement Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty.

Beghetto, R. (2013). Expect the Unexpected: Teaching for Creativity in the Micromoments. In M.B. Gregerson, H.T. Snyder, and J.C. Kaufman (Eds.). Teaching Creatively and Teaching Creativity . Springer.

Cavanagh, S. R. (2021). How to Play in the College Classroom in a Pandemic, and Why You Should . The Chronicle of Higher Education. February 9, 2021.

Chicca, J. and Chunta, K, (2020). Engaging Students with Visual Stories: Using Infographics in Nursing Education . Teaching and Learning in Nursing. 15(1), 32-36.

Davis, M. E. (2019). Poetry and economics: Creativity, engagement and learning in the economics classroom. International Review of Economics Education. Volume 30.

Desrochers, C. G. and Zell, D. (2012). Gave projects, tests, or assignments that required original or creative thinking! POD-IDEA Center Notes on Instruction.

DiYanni, R. (2015). Critical and creative thinking : A brief guide for teachers . John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Eyler, J. R. (2018). How Humans Learn. The Science and Stories Behind Effective College Teaching. West Virginia University Press.

Forbes, L. K. (2021). The Process of Play in Learning in Higher Education: A Phenomenological Study. Journal of Teaching and Learning. Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 57-73.

Gerstle, K. (2017). Incorporating Meaningful Reflection into Calculus Assignments. PRIMUS. Problems, Resources, and Issues in Mathematics Undergraduate Studies. 29(1), 71-81.

Gregerson, M. B., Snyder, H. T., and Kaufman, J. C. (2013). Teaching Creatively and Teaching Creativity . Springer.

Henry, M., Owens, E. A., and Tawney, J. G. (2015). Creative Report Writing in Undergraduate Organic Chemistry Laboratory Inspires Non Majors. Journal of Chemical Education , 92, 90-95.

Hitchcock, L. I., Sage, T., Lynch, M. and Sage, M. (2021). Podcasting as a Pedagogical Tool for Experiential Learning in Social Work Education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work . 41(2). 172-191.

James, A., & Brookfield, S. D. (2014). Engaging imagination : Helping students become creative and reflective thinkers . John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Jackson, N. (2008). Tackling the Wicked Problem of Creativity in Higher Education.

Jackson, N. (2006). Creativity in higher education. SCEPTrE Scholarly Paper , 3 , 1-25.

Kleiman, P. (2008). Towards transformation: conceptions of creativity in higher education.

Kothari, D., Hall, A. O., Castañeda, C. A., and McNeil, A. J. (2019). Connecting Organic Chemistry Concepts with Real-World Context by Creating Infographics. Journal of Chemistry Education. 96(11), 2524-2527.

McLellan, H. (2007). Digital Storytelling in Higher Education. Journal of Computing in Higher Education. 19, 65-79.

Ranjan, A., & Gabora, L. (2013). Creative Ideas for Actualizing Student Potential. In M.B. Gregerson, H.T. Snyder, and J.C. Kaufman (Eds.). Teaching Creatively and Teaching Creativity . Springer.

Rossiter, M. and Garcia, P. A. (2010). Digital Storytelling: A New Player on the Narrative Field. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. No. 126, Summer 2010.

Sheafer, V. (2017). Using digital storytelling to teach psychology: A preliminary investigation. Psychology Learning & Teaching. 16(1), 133-143.

Sinfield, S., Burns, B., & Abegglen, S. (2018). Exploration: Becoming Playful – The Power of a Ludic Module. In A. James and C. Nerantzi (Eds.). The Power of Play in Higher Education . Palgrave Macmillan.

Reynolds, C., Stevens, D. D., and West, E. (2013). “I’m in a Professional School! Why Are You Making Me Do This?” A Cross-Disciplinary Study of the Use of Creative Classroom Projects on Student Learning. College Teaching. 61: 51-59.

Sweet, C., Carpenter, R., Blythe, H., and Apostel, S. (2013). Teaching Applied Creative Thinking: A New Pedagogy for the 21st Century. Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press Inc.

Tatter, G. (2019). Playing to Learn: How a pedagogy of play can enliven the classroom, for students of all ages . Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Vaughn, M. P. and Leon, D. (2021). The Personal Is Political Art: Using Digital Storytelling to Teaching Sociology of Sexualities. Teaching Sociology. 49(3), 245-255.

Wukich, C. and Siciliano, M. D. (2014). Problem Solving and Creativity in Public Policy Courses: Promoting Interest and Civic Engagement. Journal of Political Science Education . 10, 352-368.

CTL resources and technology for you.

- Overview of all CTL Resources and Technology

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Advertisement

Interdisciplinarity in design education: understanding the undergraduate student experience

- Published: 27 January 2016

- Volume 27 , pages 459–480, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

- James A. Self 1 &

- Joon Sang Baek 1

1946 Accesses

23 Citations

2 Altmetric

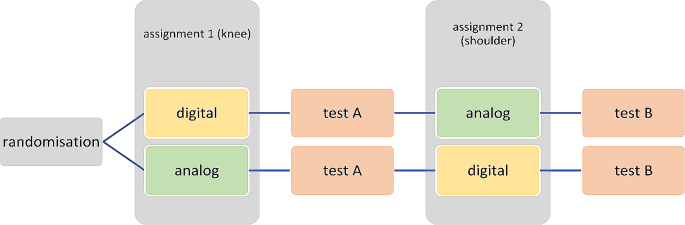

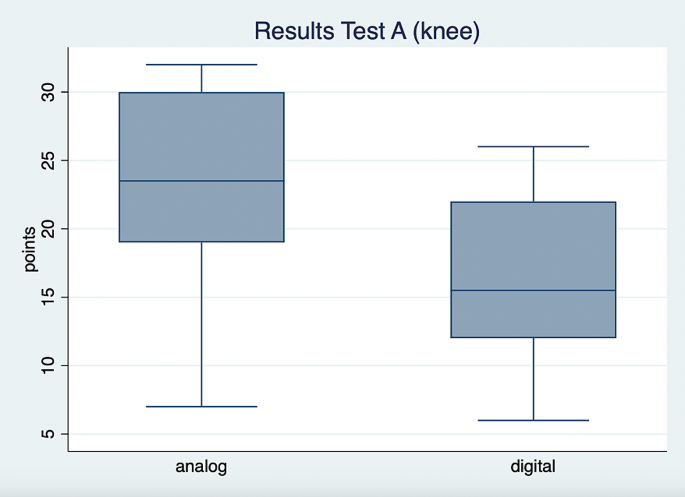

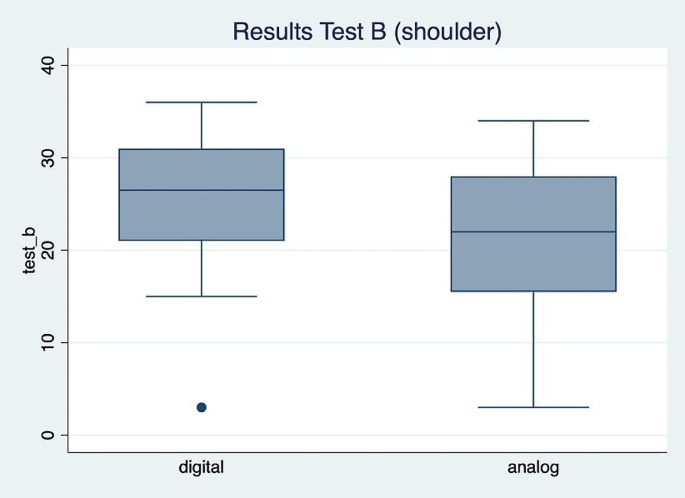

Explore all metrics

Interdisciplinarity is becoming a critical issue of concern for design schools across East Asia in their attempts to provide industry graduates with the skills and competences to make creative contributions in a global economy. As a result, East Asian higher education institutions are aggressively endeavouring to provide interdisciplinary undergraduate curriculum that combine traditional designerly skills with engineering knowledge and methods. The current study takes an interdisciplinary undergraduate course as case-study to examine how the pedagogic strategy of team teaching influences student learning experience. Two surveys of student learning were conducted for this research purpose. The first provided an indication of the holistic student learning experience, while the second explored the conditions of team and non-team teaching as influence upon learning experiences specifically. Results showed how students taught by a single instructor provided a more positive overall opinion of course quality and experienced significantly more encouragement to participate compared to team taught respondents. However, findings also indicated how team teaching significantly increased the students’ experience of a balanced contribution from different disciplinary perspectives and how the team teaching approach was significantly more effective in providing students with greater opportunities to understand the relevance of the different disciplines to the course subject. We conclude with a discussion of results in terms of the effective use of team teaching at undergraduate level as strategy for interdisciplinary learning experiences.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

To Explore the Influence of Single-Disciplinary Team and Cross-Disciplinary Team on Students in Design Thinking Education

Interdisciplinary: challenges and opportunities for design education

Is group work beneficial for producing creative designs in STEM design education?

Adams, R. S., Turns, J., & Atman, C. J. (2003). Educating effective engineering designers: The role of reflective practice. Design Studies, 24 (3), 275–294.

Article Google Scholar

Affairs, Educational. (2013). UNIST 2013 course catalog . In UNIST (Ed.), Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST).

Carulli, M., Bordegoni, M., & Cugini, U. (2013). An intergrated framework to support design & engineering education. International Journal of Engineering Education, 29 (2), 291–303.

Google Scholar

Jaeger, A., Mayrhofer, W., Kuhlang, P., & Matyas, K. (2013). Total immersion: Hands and heads-on training in a learning factory for comprehensive industrial engineering education. International Journal of Engineering Education, 29 (1), 23–32.

Kang, N. (2008). Activation plan for the convergence study of scientific technology & humanities and social sciences . Ministry of education, science and technology.

Kaygan, P. (2014). ‘Arty’ versus ‘Real’ work: Gendered relations between industrial designers and engineers in interdisciplinary work settings. The Design Journal, 17 (1), 73–90. doi: 10.2752/175630614X13787503069990 .

Kim, K., Kim, N., Jung, S., Kim, D. Y., Kwak, Y., & Kyung, G. (2012). A radically assembled design-engineering education program with a selection and combination of multiple disciplines. International Journal of Engineering Education, 28 (4), 904–919.

Klein, J., & Newell, W. (1998). Advancing interdisciplinary studies. In W. Newell (Ed.), Interdisciplinarity: Essays from the literature . New York: College Entrance Examination Board.

Kolb, D. (2014). The structure of knowledge experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (2nd ed., pp. 153–192). New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc.

Lattuca, L. (2001a). Considering interdisciplinarity creating interdisciplinarity: Interdisciplinary research and teaching among College and University faculty . New York: Vanderbilt University Press.

Lattuca, L. R. (2001b). Creating interdisciplinarity: Interdisciplinary research and teaching among college and University faculty . Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Lattuca, L, & Knight, D. (2010). AC 2010-1537: In the eye of the beholder: Defining and studying interdisciplinarity in engineering education.

Lattuca, L., Knight, D., & Bergom, I. (2013). Developing a measure of interdisciplinary competence. International Journal of Engineering Education, 29 (3), 726–739.

Lattuca, L. R., Voight, L. J., & Fath, K. Q. (2004). Does interdisciplinarity promote learning? Theoretical support and researchable questions. Review of Higher Education, 28 (1), 23-C.

Lee, J. (2014). The integrated design process from the facilitator’s perspective. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 33 (1), 141–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-8070.2014.12000.x .

Mansilla, V., & Duraising, E. (2007). Targeted assessment of students’ interdisciplinary work: An empirically grounded framework proposed. The Journal of Higher Education, 78 (2), 215–237.

Mansilla, V., & Gardner, H. (2003). Assessing interdisciplinary work at the frontier: An empirical exploration of “symptoms of quality”. In G. Origgi & C. Heintz (Eds.), Rethinking interdisciplinarity . Cambridge: Harvard University.

Mendoza, H. R., Bernasconi, C., & MacDonald, N. M. (2007). Creating new identities in design education. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 26 (3), 308–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-8070.2007.00541.x .

Mok, Y. H. (2009). Korea education in the age of knowledge convergence . Paper presented at the autumn conference of Korean educational research association.

Newell, W. (2001). A theory of interdisciplinary studies. Issues in Integrative Studies, 19 , 1–25.

Norman, D. (2010) Why Design Education Must Change. Core77, Retrieved from http://www.core77.com/posts/17993/why-design-education-must-change-17993

Norman, D, & Klemmer, S. (2014). State of design: How design education must change. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20140325102438-12181762-state-of-design-how-design-educationmust-change .

Oehlberg, L., Leighton, I., & Agogino, A. (2012). Teaching human-centred design innovation across engineering, humanities and social sciences. International Journal of Engineering Education, 28 (2), 484–491.

Repko, A. (2012). Interdisciplinary research: Process and theory (2nd ed.). New York: SAGE Publications Inc.

Strong, D. (2012). An approach for improving design and innovation skills in engineering education: The multidisciplinary design stream. International Journal of Engineering Education, 28 (2), 339–348.

Suh, S. G., & Park, S., J. (2009). The Korean Government’s Policies and Strategies to Foster World-Class Universities. In Cheng, Y., Wang, Q. & Nian, C., L. (Eds.), How World-Class Universities Affect Global Higher Education . (pp. 65–83). Rotterdam: SensePublishes.

The Korean Ministy of Education, Science and Technology. (2008). World Class University Project .

Thompson, M. (2009). Increasing the rigor of freshman design education . Paper presented at the iasdr09, Seoul. http://www.iasdr2009.or.kr/index.html . Accessed 15 Jan 2015.

Thompson, M. K. (2009). ED100: Shifting paradigms in design education and student thinking at KAIST . Paper presented at the CIRP design conference 2009.

Tolbert, D., & Daly, R. (2013). First-year engineering student perceptions of creative opportunities in design. International Journal of Engineering Education, 29 (4), 879–890.

Yim, H, Lee, K, Brezing, A, Lower, M, & Feldhusen, J. (2011). Learning from an interdisciplinary and intercultural project - based design course . Paper presented at the international conference on engineering and product design education, City University, London, UK.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our gratitude to all the students who took the time to respond to our call for participation and our institution in supporting opportunities for interdisciplinarity to prosper. This work was supported by the UNIST Creative and Innovative Project fund 1.150129.01.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Design and Human Engineering, UNIST, Ulsan, Republic of Korea

James A. Self & Joon Sang Baek

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to James A. Self .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Self, J.A., Baek, J. Interdisciplinarity in design education: understanding the undergraduate student experience. Int J Technol Des Educ 27 , 459–480 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-016-9355-2

Download citation

Accepted : 19 January 2016

Published : 27 January 2016

Issue Date : September 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-016-9355-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Interdisciplinarity

- Student experience

- Team teaching

- Design thinking

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, creating assignments.

Here are some general suggestions and questions to consider when creating assignments. There are also many other resources in print and on the web that provide examples of interesting, discipline-specific assignment ideas.

Consider your learning objectives.

What do you want students to learn in your course? What could they do that would show you that they have learned it? To determine assignments that truly serve your course objectives, it is useful to write out your objectives in this form: I want my students to be able to ____. Use active, measurable verbs as you complete that sentence (e.g., compare theories, discuss ramifications, recommend strategies), and your learning objectives will point you towards suitable assignments.

Design assignments that are interesting and challenging.

This is the fun side of assignment design. Consider how to focus students’ thinking in ways that are creative, challenging, and motivating. Think beyond the conventional assignment type! For example, one American historian requires students to write diary entries for a hypothetical Nebraska farmwoman in the 1890s. By specifying that students’ diary entries must demonstrate the breadth of their historical knowledge (e.g., gender, economics, technology, diet, family structure), the instructor gets students to exercise their imaginations while also accomplishing the learning objectives of the course (Walvoord & Anderson, 1989, p. 25).

Double-check alignment.

After creating your assignments, go back to your learning objectives and make sure there is still a good match between what you want students to learn and what you are asking them to do. If you find a mismatch, you will need to adjust either the assignments or the learning objectives. For instance, if your goal is for students to be able to analyze and evaluate texts, but your assignments only ask them to summarize texts, you would need to add an analytical and evaluative dimension to some assignments or rethink your learning objectives.

Name assignments accurately.

Students can be misled by assignments that are named inappropriately. For example, if you want students to analyze a product’s strengths and weaknesses but you call the assignment a “product description,” students may focus all their energies on the descriptive, not the critical, elements of the task. Thus, it is important to ensure that the titles of your assignments communicate their intention accurately to students.

Consider sequencing.

Think about how to order your assignments so that they build skills in a logical sequence. Ideally, assignments that require the most synthesis of skills and knowledge should come later in the semester, preceded by smaller assignments that build these skills incrementally. For example, if an instructor’s final assignment is a research project that requires students to evaluate a technological solution to an environmental problem, earlier assignments should reinforce component skills, including the ability to identify and discuss key environmental issues, apply evaluative criteria, and find appropriate research sources.

Think about scheduling.

Consider your intended assignments in relation to the academic calendar and decide how they can be reasonably spaced throughout the semester, taking into account holidays and key campus events. Consider how long it will take students to complete all parts of the assignment (e.g., planning, library research, reading, coordinating groups, writing, integrating the contributions of team members, developing a presentation), and be sure to allow sufficient time between assignments.

Check feasibility.

Is the workload you have in mind reasonable for your students? Is the grading burden manageable for you? Sometimes there are ways to reduce workload (whether for you or for students) without compromising learning objectives. For example, if a primary objective in assigning a project is for students to identify an interesting engineering problem and do some preliminary research on it, it might be reasonable to require students to submit a project proposal and annotated bibliography rather than a fully developed report. If your learning objectives are clear, you will see where corners can be cut without sacrificing educational quality.

Articulate the task description clearly.

If an assignment is vague, students may interpret it any number of ways – and not necessarily how you intended. Thus, it is critical to clearly and unambiguously identify the task students are to do (e.g., design a website to help high school students locate environmental resources, create an annotated bibliography of readings on apartheid). It can be helpful to differentiate the central task (what students are supposed to produce) from other advice and information you provide in your assignment description.

Establish clear performance criteria.

Different instructors apply different criteria when grading student work, so it’s important that you clearly articulate to students what your criteria are. To do so, think about the best student work you have seen on similar tasks and try to identify the specific characteristics that made it excellent, such as clarity of thought, originality, logical organization, or use of a wide range of sources. Then identify the characteristics of the worst student work you have seen, such as shaky evidence, weak organizational structure, or lack of focus. Identifying these characteristics can help you consciously articulate the criteria you already apply. It is important to communicate these criteria to students, whether in your assignment description or as a separate rubric or scoring guide . Clearly articulated performance criteria can prevent unnecessary confusion about your expectations while also setting a high standard for students to meet.

Specify the intended audience.

Students make assumptions about the audience they are addressing in papers and presentations, which influences how they pitch their message. For example, students may assume that, since the instructor is their primary audience, they do not need to define discipline-specific terms or concepts. These assumptions may not match the instructor’s expectations. Thus, it is important on assignments to specify the intended audience http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm (e.g., undergraduates with no biology background, a potential funder who does not know engineering).

Specify the purpose of the assignment.

If students are unclear about the goals or purpose of the assignment, they may make unnecessary mistakes. For example, if students believe an assignment is focused on summarizing research as opposed to evaluating it, they may seriously miscalculate the task and put their energies in the wrong place. The same is true they think the goal of an economics problem set is to find the correct answer, rather than demonstrate a clear chain of economic reasoning. Consequently, it is important to make your objectives for the assignment clear to students.

Specify the parameters.

If you have specific parameters in mind for the assignment (e.g., length, size, formatting, citation conventions) you should be sure to specify them in your assignment description. Otherwise, students may misapply conventions and formats they learned in other courses that are not appropriate for yours.

A Checklist for Designing Assignments

Here is a set of questions you can ask yourself when creating an assignment.

- Provided a written description of the assignment (in the syllabus or in a separate document)?

- Specified the purpose of the assignment?

- Indicated the intended audience?

- Articulated the instructions in precise and unambiguous language?

- Provided information about the appropriate format and presentation (e.g., page length, typed, cover sheet, bibliography)?

- Indicated special instructions, such as a particular citation style or headings?

- Specified the due date and the consequences for missing it?

- Articulated performance criteria clearly?

- Indicated the assignment’s point value or percentage of the course grade?

- Provided students (where appropriate) with models or samples?

Adapted from the WAC Clearinghouse at http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm .

CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

- Faculty Support

- Graduate Student Support

- Canvas @ Carnegie Mellon

- Quick Links

- Join Our Listserv

- Request a Consult

- Search Penn's Online Offerings

- Assignment Design: Is AI In or Out?

Generative AI

- Rachel Hoke

This page provides examples for designing AI out of or into your assignments. These ideas are intended to provide a starting point as you consider how assignment design can limit or encourage certain uses of AI to help students learn. CETLI is available to consult with you about ways you might design AI out of or into your assignments.

Considerations for Crafting Assignments

- Connect to your goals. Assignments support the learning goals of your course, and decisions about how students may or may not use AI should be based on these goals.

- Designing ‘in’ doesn’t mean ‘all in’. Incorporating certain uses of AI into an assignment doesn’t mean you have to allow all uses, especially those that would interfere with learning.

- Communicate to students . Think about how you will explain the assignment’s purpose and benefits to your students, including the rationale for your guidelines on AI use.

Design Out: Limit AI Use

Very few assignments are truly AI-proof, but some designs are more resistant to student AI use than others. Along with designing assignments in ways that deter the use of AI, inform students about your course AI policies regarding what is and is not acceptable as well as the potential consequences for violating these terms.

Assignments that ask students to refer to something highly specific to your course or not easily searchable online will make it difficult for AI to generate a response. Examples include asking students to:

- Summarize, discuss, question, or otherwise respond to content from an in-class activity, a specific part of your lecture, or a classmate’s discussion comments.

- Relate course content to issues that have local context or personal relevance. The more recent and specific the topic, the more poorly AI will perform.

- Respond to visual or multimedia material as part of their assignment. AI has difficulty processing non-text information.

Find opportunities for students to present, discuss their work, and respond to questions from others. To field questions live requires students to demonstrate their understanding of the topic, and the skill of talking succinctly about one’s work and research is valuable for students in many disciplines. You might ask students to:

- Create an “elevator pitch” for a research idea and submit it as a short video, then watch and respond to peers’ ideas.

- Give an in-class presentation with Q&A that supplements submitted written work.

- Meet with you or your TA to discuss their ideas and receive constructive feedback before or after completing the assignment.

This strategy allows students to show how they have thought about the work that they’ve done and places value on their awareness of their learning. For instance, students might:

- Briefly write about a source or approach they considered but decided not to use and why.

- Discuss a personal connection they made to the learning material.

- Submit a reflection on how the knowledge or skills gained from the assignment apply to their professional practice.

Consider asking students to show the stages of their work or submit assignments in phases, so you can review the development of their ideas or work over time. Explaining the value of the thinking students will do in taking on the work themselves can help deter students’ dependence on AI. Additionally, this strategy helps keep students on track so they do not fall behind and feel pressure to use AI inappropriately. For materials handed in with the final product, it can give you a way to refer back to their process. You may ask students to:

- Submit an outline, list of sources, discussion of a single piece of data, explanation of their approach, or first draft before the final product.

- Meet briefly with an instructor to discuss their approach or work in progress.

- Submit the notes they have taken on sources to prepare their paper, presentation, or project.

Prior to beginning an exam or submitting an assignment, you may ask students to confirm that they have followed the policies regarding academic integrity and AI. This can be particularly helpful for an assignment with different AI guidelines than others in your course. You might:

- Ask students to affirm a statement that all submitted work is their own.

- Ask students to confirm their understanding of your generative AI policy at the start of the assignment.

If you decide to limit student’s use of AI in their work:

- Communicate the policy early, often and in a variety of ways.

- Be Transparent. Clearly explain the reasoning behind your decision to limit or exclude the use of AI in the assignment, focusing on how the assignment relates to the course’s learning objectives and how the use of AI limits the intended learning outcomes.

Design In: Encourage AI Use