- Try for free

The 6 Levels of Questioning in the Classroom (+ Examples)

Download for free!

The 6 levels of questioning in the classroom.

The goal of questioning in the classroom is not simply to determine whether students have learned something, but rather to guide them in their learning process. Unlike tests, quizzes, and exams , questioning in the classroom should be used to teach students, not test them!

Questions as tests

Teachers spend a great deal of classroom time testing students through questions. Observations of teachers at all levels of education reveal that most spend more than 90 percent of their instructional time testing students (through questioning). And most of the questions teachers ask are typically factual questions that rely on short-term memory.

Although questions are widely used and serve many functions, teachers tend to overuse factual questions such as “What is the capital of California?” Not surprising, as many teachers ask upward of 400 questions every school day! And approximately 80 percent of all the questions teachers ask are factual, literal, or knowledge-based questions.

The result is a classroom in which there is little creative thinking taking place.

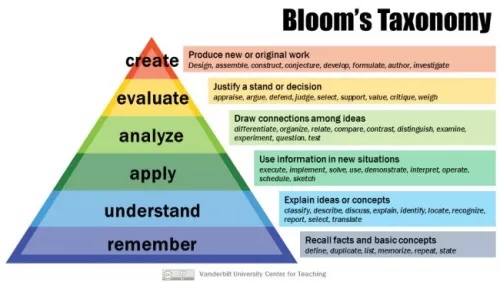

What is Bloom's Taxonomy?

Bloom's Taxonomy is a hierarchical model used in education to classify educational learning objectives into levels of complexity and specificity. It's named after Benjamin Bloom, who chaired the committee of educators that devised it in the 1950s.

The taxonomy has six levels, designed to help educators create more effective learning objectives and engage students in higher levels of thinking. These levels are arranged in hierarchical form, moving from the lowest level of cognition to the highest level of cognition.

Bloom's Taxonomy was revised in 2001 to better reflect the different types of cognitive processes used in learning and understanding.

Why use Bloom's Taxonomy?

Bloom's Taxonomy is a powerful tool in the K-12 classroom because it provides a structured approach to questioning that promotes higher levels of thinking. Instead of focusing on rote memorization, Bloom's Taxonomy encourages students to analyze, evaluate, and create. This level of questioning not only enhances students’ understanding of the material, but it also fosters critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

Moreover, this level of questioning in the classroom provides teachers with a clear framework to design their lessons and assess student learning effectively. This approach shifts the focus from merely testing students to facilitating meaningful learning experiences.

Levels of questioning in the classroom (+ examples)

Graphic used with permission by Vanderbilt University

Level 1: Remember

The first level of questioning in the classroom according to Bloom’s Taxonomy is "Remember" (previously: “Knowledge”). This base level involves recalling or recognizing information from memory. It's the most basic level of cognition, where students are asked to remember facts, terms, basic concepts, or answers without necessarily understanding what they mean.

Examples of this level of questioning in the classroom might include "What is the capital of France?" or "Who wrote 'To Kill a Mockingbird'?" Although this level is necessary, it's important to progress beyond it to promote higher levels of thinking.

Words often used in “Remember” questions often include know , who , define , what , name , where , list , and when .

Remembering question examples:

- "What is the date of the Declaration of Independence?"

- "Who is the author of 'Pride and Prejudice'?"

- "Can you list the planets in our solar system?"

- "What is the formula for the area of a rectangle?"

- "Who was the first president of the United States?"

Level 2: Understand

The second level of questioning in the classroom is "Understand" (previously: “Comprehension”). At this stage, students are expected to comprehend the material, which means they can interpret, translate, and summarize the information.

This level goes beyond simple recall of facts and asks students to explain ideas or concepts in their own words.

Keywords often used in "Understand" questions include explain , describe , identify , discuss , and interpret .

Understanding questions examples:

- "Can you summarize the main events in the book in your own words?"

- "How would you interpret the author's intentions in this scene?"

- "Can you explain the concept of photosynthesis to a 5-year-old?"

- "What do you think the significance of this event in history is?"

- "How would you translate this sentence into your own words?"

Level 3: Apply

The third level of questioning in the classroom, according to Bloom’s Taxonomy, is "Apply" (previously: “Application”). At this stage, students are expected to use the information they have learned in new situations.

This stage involves problem-solving, implementing methods, and demonstrating how concepts can be used in real-world scenarios.

This level of questioning is important because it encourages students to go beyond simply recalling information and understanding concepts and to start applying this knowledge in practical ways. It promotes critical thinking and problem-solving skills and helps students see the relevance and applicability of what they are learning.

Keywords often used in "Apply" questions include demonstrate , apply , solve , use , and illustrate .

Applying question examples:

- "How would you use the Pythagorean theorem to determine the length of the hypotenuse in a right-angled triangle?"

- "Can you construct a model to demonstrate how the solar system works?"

- "Using what you've learned about the water cycle, can you explain why it rains?"

- "How can you apply the principles of democracy to set up a student council in your school?"

- "Can you create an experiment to test the law of conservation of energy?"

Level 4: Analyze

The fourth level of questioning in the classroom is "Analyze" (previously: “Analysis”). This level involves breaking down information into its component parts for better understanding. Students are expected to differentiate, organize, and relate the parts to the whole.

This stage is crucial as it encourages students to examine information in a detailed way and to understand how different parts relate to one another. This level of questioning promotes critical thinking and a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Keywords often used in "Analyze" questions include compare , contrast , examine , classify , and break down .

Analyzing questions examples

- "How does the protagonist's journey in the novel reflect societal issues?"

- "What are the similarities and differences between two political systems?"

- "How do the different elements of this artwork contribute to its overall impact?"

- "Explain the cause and effect relationship between events in a historical period."

- "How do the different theories of economics apply to this case study?"

Level 5: Evaluate

The fifth level of questioning in the classroom is "Evaluate" (previously: “Evaluation”). At this stage, students are expected to form judgments about the value and worth of information based on criteria and standards. This involves appraising, judging, critiquing, and defending positions. This level encourages students to formulate their own opinions and make judgments based on their understanding and analysis of the information.

Keywords often used in "Evaluate" questions include judge , rate , evaluate , defend , and justify .

Evaluating question examples:

- "Was the ending of the novel satisfactory? Defend your position."

- "What do you think about the author's point of view?"

- "How would you rate this character's decisions throughout the story?"

- "Evaluate the effectiveness of the government's response in a historical event."

- "Can you justify your solution to this problem?"

Level 6: Create

The final level of questioning in the classroom according to Bloom’s Taxonomy is "Create" (previously: “Synthesis”). At this stage, students are expected to use what they've learned to create something new or original. This could involve developing a plan or proposal, deriving a set of abstract relations, or presenting an original idea. This level of questioning encourages creativity and innovation, as students are asked to generate new ideas, products, or ways of viewing things. Keywords often used in "Create" questions include design , construct , create , invent , and compose .

Creating question examples:

- "Can you devise a way to ensure clean water access in developing countries?"

- "How would you design a fair and effective classroom behavior policy?"

- "Can you create a short story based on the themes we've discussed?"

- "Compose a poem that expresses your feelings about a current event."

- "Invent a new product that solves a problem you've identified."

It's elementary!

Many teachers think primary-level students (Kindergarten through 2nd Grade) cannot handle higher-level questions. But nothing could be further from the truth! Challenging all students through higher-order questioning is one of the best ways to stimulate learning and enhance brain development, regardless of age.

If you only ask your students one level of questioning, your students might not be exposed to higher levels of thinking. If, for example, you only ask your students knowledge-based questions, they might think that learning a specific subject is nothing more than the ability to memorize a select number of facts.

The 6 levels of questioning in the classroom according to Bloom’s Taxonomy provide a structured shift from simple factual recall to more complex cognitive processes. This approach not only deepens students' understanding of the subject matter, but also fosters critical thinking, problem-solving skills, creativity, and innovation.

Featured High School Resources

Related Resources

About the author

Digital Content Manager & Editor

About haley.

Higher Level Thinking: Synthesis in Bloom's Taxonomy

Putting the Parts Together to Create New Meaning

- Teaching Resources

- An Introduction to Teaching

- Tips & Strategies

- Policies & Discipline

- Community Involvement

- School Administration

- Technology in the Classroom

- Teaching Adult Learners

- Issues In Education

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Special Education

- Homeschooling

- M.Ed., Curriculum and Instruction, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956 ) was designed with six levels in order to promote higher order thinking. Synthesis was placed on the fifth level of the Bloom’s taxonomy pyramid as it requires students to infer relationships among sources. The high-level thinking of synthesis is evident when students put the parts or information they have reviewed as a whole in order to create new meaning or a new structure.

The Online Etymology Dictionary records the word synthesis as coming from two sources:

"Latin synthesis meaning a "collection, set, suit of clothes, composition (of a medication)" and also from the Greek synthesis meaning "a composition, a putting together."

The dictionary also records the evolution of the use of synthesis to include "deductive reasoning" in 1610 and "a combination of parts into a whole" in 1733. Today's students may use a variety of sources when they combine parts into a whole. The sources for synthesis may include articles, fiction, posts, or infographics as well as non-written sources, such as films, lectures, audio recordings, or observations.

Types of Synthesis in Writing

Synthesis writing is a process in which a student makes the explicit connection between a thesis (the argument) and evidence from sources with similar or dissimilar ideas. Before synthesis can take place, however, the student must complete a careful examination or close reading of all source material. This is especially important before a student can draft a synthesis essay.

There are two types of synthesis essays:

- A student may choose to use an explanatory synthesis essay in order to deconstruct or divide evidence into logical parts so that the essay is organized for readers. Explanatory synthesis essays usually include descriptions of objects, places, events or processes. Descriptions are written objectively because the explanatory synthesis does not present a position. The essay here has information gathered from the sources that the student places in a sequence or other logical manner.

- In order to present a position or opinion, a student may choose to use an argumentative synthesis. The thesis or position of an argumentative essay is one that can be debated. A thesis or position in this essay can be supported with evidence taken from sources and is organized so that it can be presented in a logical manner.

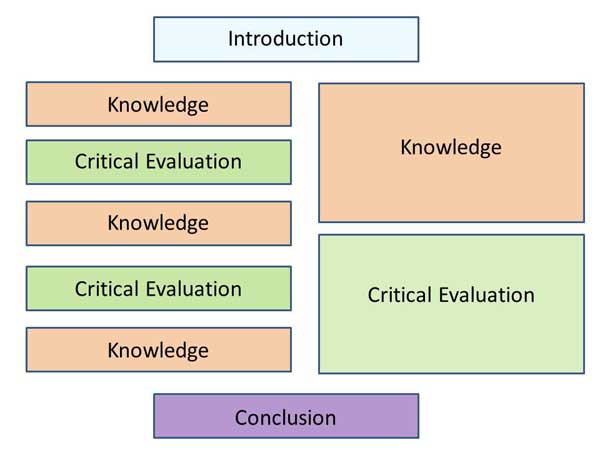

The introduction to either synthesis essay contains a one-sentence (thesis) statement that sums up the essay's focus and introduces the sources or texts that will be synthesized. Students should follow the citation guidelines in referencing the texts in the essay, which includes their title and author(s) and maybe a little context about the topic or background information.

The body paragraphs of a synthesis essay can be organized using several different techniques separately or in combination. These techniques can include: using a summary, making comparisons and contrasts, providing examples, proposing cause and effect, or conceding opposing viewpoints. Each of these formats allows the student the chance to incorporate the source materials in either the explanatory or the argumentative synthesis essay.

The conclusion of a synthesis essay may remind readers of the key points or suggestions for further research. In the case of the argumentative synthesis essay, the conclusion answers the "so what" that was proposed in the thesis or may call for action from the reader.

Key Words for the Synthesis Category:

blend, categorize, compile, compose, create, design, develop, form, fuse, imagine, integrate, modify, originate, organize, plan, predict, propose, rearrange, reconstruct, reorganize, solve, summarize, test, theorize, unite.

Synthesis Question Stems With Examples

- Can you develop a theory for the popularity of a text in English?

- Can you predict the outcome of behavior in Psychology I by using polls or exit slips?

- How could you test the speed of a rubber-band car in physics if a test track is not available?

- How would you adapt ingredients to create a healthier casserole in Nutrition 103 class?'

- How could you change the plot of Shakespeare's Macbeth so it could be rated "G"?

- Suppose you could blend iron with another element so that it could burn hotter?

- What changes would you make to solve a linear equation if you could not use letters as variables?

- Can you fuse Hawthorne's short story "The Minister's Black Veil" with a soundtrack?

- Compose a nationalist song using percussion only.

- If you rearrange the parts in the poem "The Road Not Taken", what would the last line be?

Synthesis Essay Prompt Examples

- Can you propose a universal course of study in the use of social media that could be implemented across the United States?

- What steps could be taken in order to minimize food waste from the school cafeteria?

- What facts can you compile to determine if there has been an increase in racist behavior or an increase in awareness of racist behavior?

- What could you design to wean young children off video games?

- Can you think of an original way for schools to promote awareness of global warming or climate change?

- How many ways can you use technology in the classroom to improve student understanding?

- What criteria would you use to compare American Literature with English Literature?

Synthesis Performance Assessment Examples

- Design a classroom that would support educational technology.

- Create a new toy for teaching the American Revolution. Give it a name and plan a marketing campaign.

- Write and present a news broadcast about a scientific discovery.

- Propose a magazine cover for a famous artist using his or her work.

- Make a mix tape for a character in a novel.

- Hold an election for the most important element on the periodic table.

- Put new words to a known melody in order to promote healthy habits.

- Questions for Each Level of Bloom's Taxonomy

- Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) in Education

- Bloom's Taxonomy - Application Category

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- Asking Better Questions With Bloom's Taxonomy

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- How to Construct a Bloom's Taxonomy Assessment

- Using Bloom's Taxonomy for Effective Learning

- Beef Up Critical Thinking and Writing Skills: Comparison Essays

- Bloom's Taxonomy in the Classroom

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- Composition Type: Problem-Solution Essays

- What Is Expository Writing?

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

Literature Review Basics

- What is a Literature Review?

- Synthesizing Research

- Using Research & Synthesis Tables

- Additional Resources

Synthesis: What is it?

First, let's be perfectly clear about what synthesizing your research isn't :

- - It isn't just summarizing the material you read

- - It isn't generating a collection of annotations or comments (like an annotated bibliography)

- - It isn't compiling a report on every single thing ever written in relation to your topic

When you synthesize your research, your job is to help your reader understand the current state of the conversation on your topic, relative to your research question. That may include doing the following:

- - Selecting and using representative work on the topic

- - Identifying and discussing trends in published data or results

- - Identifying and explaining the impact of common features (study populations, interventions, etc.) that appear frequently in the literature

- - Explaining controversies, disputes, or central issues in the literature that are relevant to your research question

- - Identifying gaps in the literature, where more research is needed

- - Establishing the discussion to which your own research contributes and demonstrating the value of your contribution

Essentially, you're telling your reader where they are (and where you are) in the scholarly conversation about your project.

Synthesis: How do I do it?

Synthesis, step by step.

This is what you need to do before you write your review.

- Identify and clearly describe your research question (you may find the Formulating PICOT Questions table at the Additional Resources tab helpful).

- Collect sources relevant to your research question.

- Organize and describe the sources you've found -- your job is to identify what types of sources you've collected (reviews, clinical trials, etc.), identify their purpose (what are they measuring, testing, or trying to discover?), determine the level of evidence they represent (see the Levels of Evidence table at the Additional Resources tab ), and briefly explain their major findings . Use a Research Table to document this step.

- Study the information you've put in your Research Table and examine your collected sources, looking for similarities and differences . Pay particular attention to populations , methods (especially relative to levels of evidence), and findings .

- Analyze what you learn in (4) using a tool like a Synthesis Table. Your goal is to identify relevant themes, trends, gaps, and issues in the research. Your literature review will collect the results of this analysis and explain them in relation to your research question.

Analysis tips

- - Sometimes, what you don't find in the literature is as important as what you do find -- look for questions that the existing research hasn't answered yet.

- - If any of the sources you've collected refer to or respond to each other, keep an eye on how they're related -- it may provide a clue as to whether or not study results have been successfully replicated.

- - Sorting your collected sources by level of evidence can provide valuable insight into how a particular topic has been covered, and it may help you to identify gaps worth addressing in your own work.

- << Previous: What is a Literature Review?

- Next: Using Research & Synthesis Tables >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 12:06 PM

- URL: https://usi.libguides.com/literature-review-basics

Writing Resources

- Student Paper Template

- Grammar Guidelines

- Punctuation Guidelines

- Writing Guidelines

- Creating a Title

- Outlining and Annotating

- Using Generative AI (Chat GPT and others)

- Introduction, Thesis, and Conclusion

- Strategies for Citations

- Determining the Resource This link opens in a new window

- Citation Examples

- Paragraph Development

- Paraphrasing

- Inclusive Language

- International Center for Academic Integrity

- How to Synthesize and Analyze

- Synthesis and Analysis Practice

- Synthesis and Analysis Group Sessions

- Decoding the Assignment Prompt

- Annotated Bibliography

- Comparative Analysis

- Conducting an Interview

- Infographics

- Office Memo

- Policy Brief

- Poster Presentations

- PowerPoint Presentation

- White Paper

- Writing a Blog

- Research Writing: The 5 Step Approach

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- MLA Resources

- Time Management

ASC Chat Hours

ASC Chat is usually available at the following times ( Pacific Time):

If there is not a coach on duty, submit your question via one of the below methods:

928-440-1325

Ask a Coach

Search our FAQs on the Academic Success Center's Ask a Coach page.

Learning about Synthesis Analysis

What D oes Synthesis and Analysis Mean?

Synthesis: the combination of ideas to

- show commonalities or patterns

Analysis: a detailed examination

- of elements, ideas, or the structure of something

- can be a basis for discussion or interpretation

Synthesis and Analysis: combine and examine ideas to

- show how commonalities, patterns, and elements fit together

- form a unified point for a theory, discussion, or interpretation

- develop an informed evaluation of the idea by presenting several different viewpoints and/or ideas

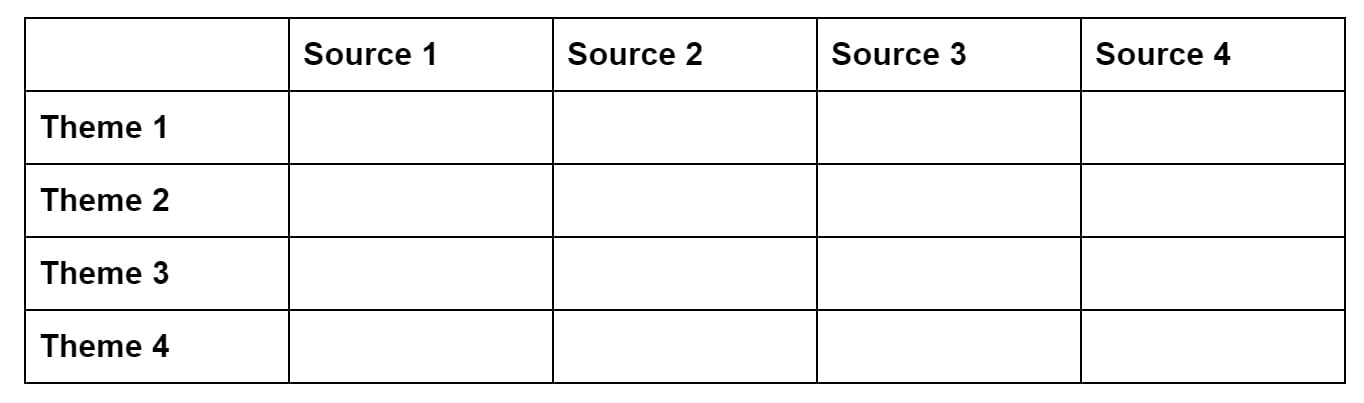

Key Resource: Synthesis Matrix

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix is an excellent tool to use to organize sources by theme and to be able to see the similarities and differences as well as any important patterns in the methodology and recommendations for future research. Using a synthesis matrix can assist you not only in synthesizing and analyzing, but it can also aid you in finding a researchable problem and gaps in methodology and/or research.

Use the Synthesis Matrix Template attached below to organize your research by theme and look for patterns in your sources .Use the companion handout, "Types of Articles" to aid you in identifying the different article types for the sources you are using in your matrix. If you have any questions about how to use the synthesis matrix, sign up for the synthesis analysis group session to practice using them with Dr. Sara Northern!

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: International Center for Academic Integrity

- Next: How to Synthesize and Analyze >>

- Last Updated: Apr 10, 2024 2:12 PM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/writingresources

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Digital SAT Reading and Writing

Course: digital sat reading and writing > unit 2, rhetorical synthesis | lesson.

- Rhetorical synthesis — Worked example

- Rhetorical Synthesis — Quick example

- Rhetorical synthesis: foundations

What are "rhetorical synthesis" questions?

- The novel David Copperfield by Charles Dickens focuses on the adventures of its title character, David Copperfield.

- David Copperfield is considered a bildungsroman.

- In a bildungsroman, the main character grows, learns, and changes from experience.

- The novel Tom Jones by Henry Fielding focuses on the adventures of its title character, Tom Jones.

- Tom Jones is considered a picaresque novel.

- In a picaresque novel, the main character has many experiences but stays fundamentally the same.

- (Choice A) David Copperfield and Tom Jones are both considered picaresque novels. A David Copperfield and Tom Jones are both considered picaresque novels.

- (Choice B) Both David Copperfield and Tom Jones focus on the adventures of their title characters. B Both David Copperfield and Tom Jones focus on the adventures of their title characters.

- (Choice C) David Copperfield was written by Charles Dickens; Tom Jones was written by Henry Fielding. C David Copperfield was written by Charles Dickens; Tom Jones was written by Henry Fielding.

- (Choice D) In David Copperfield , unlike in Tom Jones , the main character grows, learns, and changes from experience. D In David Copperfield , unlike in Tom Jones , the main character grows, learns, and changes from experience.

Choice A: This choice does not accurately represent the information in the bullet points! Bullet point 2 tells us that David Copperfield is considered a bildungsroman. The next bullet points tell us that in a bildungsroman, the main character changes, while in a picaresque novel, the main character basically stays the same. This means that a bildungsroman can't also be a picaresque novel.

Choice B: This choice emphasizes a similarity and accurately represents the information in the bullet points. Bullet point 1 says that David Copperfield focuses on the adventures of its title character, and bullet point 4 says that Tom Jones focuses on the adventures of its title character.

Choice C: This choice accurately represents the bulleted information, but it doesn't accomplish the goal. It highlights a difference between the two novels—the fact that they have different authors. But we're looking for a similarity.

Choice D: Like choice C, this choice accurately represents the bulleted information, but it doesn't accomplish the goal. It emphasizes a difference between the two novels, but, again, we're looking for a similarity.

How should we think about rhetorical synthesis questions?

Question structure.

- an introduction

- a series of bulleted facts

- a question prompt

- the choices

How to approach rhetorical synthesis questions

Step 1: Identify the goal

Step 2: Read the bullet points and identify relevant info

Step 3: Test the choices

Step 4: Select the choice that matches

Do two "passes" to eliminate choices!

Simplify the goal.

- Choice C emphasizes a difference between the two novels, not a similarity. We can eliminate choice C.

- Choice D also emphasizes a difference between the two novels, not a similarity. We can eliminate choice D.

Ignore the grammar

- Marine biologist Camille Jazmin Gaynus studies coral reefs.

- Coral reefs are vital underwater ecosystems that provide habitats to 25% of all marine species.

- Reefs can include up to 8,000 species of fish, such as toadfish, seahorses, and clown triggerfish.

- The Amazon Reef is a coral reef in Brazil.

- It is one of the largest known reefs in the world.

- (Choice A) Providing homes to 25% of all marine species, including up to 8,000 species of fish, coral reefs are vital underwater ecosystems and thus of great interest to marine biologists. A Providing homes to 25% of all marine species, including up to 8,000 species of fish, coral reefs are vital underwater ecosystems and thus of great interest to marine biologists.

- (Choice B) Marine biologist Camille Jazmin Gaynus studies coral reefs, vital underwater ecosystems that provide homes to 25% of all marine species. B Marine biologist Camille Jazmin Gaynus studies coral reefs, vital underwater ecosystems that provide homes to 25% of all marine species.

- (Choice C) Camilla Jazmin Gaynus is a marine biologist who exclusively studies the Amazon Reef, a coral reef that is home to 8,000 different species of fish. C Camilla Jazmin Gaynus is a marine biologist who exclusively studies the Amazon Reef, a coral reef that is home to 8,000 different species of fish.

- (Choice D) As Camille Jazmin Gaynus knows well, coral reefs are vital underwater ecosystems, providing homes to thousands of species of fish. D As Camille Jazmin Gaynus knows well, coral reefs are vital underwater ecosystems, providing homes to thousands of species of fish.

- Choice A doesn't mention the scientist at all. We can eliminate choice A.

- Remember to be strict : the goal is to introduce the scientist AND her field of study. Choice D names the scientist, but it doesn't introduce her field of study (it doesn't say she's a marine biologist). We can eliminate choice D.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Home » Insights

Completing the Learning Loop: The Power of Synthesis and Reflection Prompts

by Jon Altbergs and Laurie Gagnon

At redesign, we encourage the adoption of a learning cycle that guides the learner through the habits and skills that support the development of competency with practice over time. in this post, we dig into the synthesis and reflection element of the learning cycle..

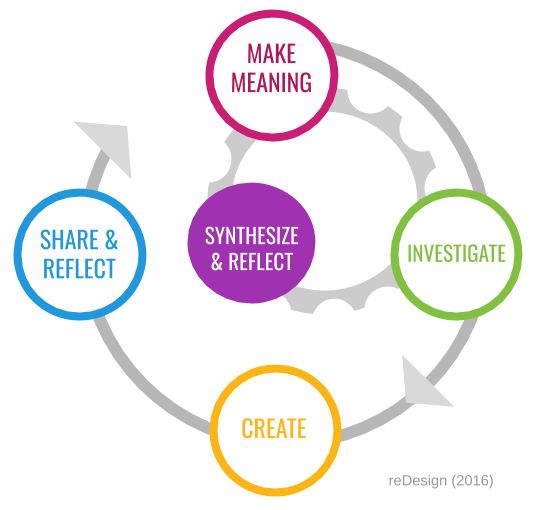

Let’s take a moment to revisit the two dimensions of the learning cycle. It represents the stages of meaningful learning that occur simultaneously during daily learning experiences (the “inner circle), and across multi-week units of study they constitute (the “outer circle”) that build toward authentic, competency-building work.

As our colleague Sydney Schaef explained in A Friendly Introduction to the Competency-based Learning Cycle ,

In a nutshell, the Competency-based Learning Cycle is a visual framework that illustrates the cognitive and metacognitive processes that help learners develop competency with practice and feedback, as they work and learn in increasingly challenging contexts. …The “outer circle” represents the four major stages of a competency-based project or unit of study through which learners explore a compelling question or issue. …The “inner circle” structures daily learning experiences. … These learning experiences are purposefully and directly connected to the larger arc (outer circle), such that successful, recursive movement through this inner cycle enables progress through the four stages of the unit.

Ongoing synthesis and reflection anchor the learning cycle. Every learning experience, we believe, should culminate with synthesis and reflection questions. Why are synthesis and reflection questions so important to close the loop of a lesson or learning experience? They are essential because the information they provide:

- supports the provision of individualized feedback

- builds relationships through teacher attunement

- gauges student engagement

- offers insight into learners’ metacognition, the key to self-directed learning.

Ultimately, synthesis and reflection questions are a moment of pause to “lift the hood” on learners’ thinking.

Meaningful learning and assessment generate evidence of learning (as opposed to simply evidence of working). Synthesis and reflection help the learner situate new ideas into their overall understanding and helps the teacher gain insight into the thinking processes and conceptual understanding behind other work that the learner produces . When planning lessons, teachers often rightfully focus on designing assignments and activities that prompt students to think critically about the content they are learning. But rigorous assignments are not enough. Students need opportunities to synthesize and reflect on their learning. Synthesis connects the day’s learning to prior learning, helping students build schema and deepen their understanding. Reflection encourages metacognitive development by shifting the focus from the what of learning to the how.

A synthesis prompt asks students to identify the important learning, summarize the learning, and articulate connections between the new learning and prior learning, knowledge, or experience in order to create or deepen understanding . Well-crafted synthesis questions lay the foundation for transferability of skills and knowledge. By incorporating synthesis into daily practice, building the connections that expand schema and ensure transferability is an ongoing process, rather than one that occurs at the end of a unit, the end of the year, or when new material is introduced.

Synthesizing, like other strategies and skills, is a capability that develops over time and should be explicitly taught . Responding to a synthesis prompt calls upon three specific elements: determining importance, summarizing, and connecting. First, students identify the important parts of their learning, the key takeaways from the lesson or learning experience that were essential to completing the task at hand. Second, students summarize by concisely communicating the what and the why of their learning—the key content and its importance. Finally, when students synthesize they connect the day’s learning to a larger context, such as prior learning, the essential question, or their own experience and describe how connecting the two deepens their understanding. Connections can also be made to novel situations to extend thinking.

Ultimately, the purpose of synthesis questions is the production, rather than reproduction, of knowledge . When students begin to explore a specific topic, their pool of knowledge may be limited, making rich connections and synthesis more difficult, but as they have more to call upon, those new (to them) insights happen more often.

Though the thinking underlying synthesis prompts is complex, the prompts themselves don’t have to be. I used to think … but then I learned … and so now is a simple frame for synthesis. As part of an exit ticket, journaling prompt, or classroom discussion, this frame incorporates all three elements and creates the opportunity to uncover what students know and what gaps and misconceptions need to be addressed.

A reflection prompt asks students to look critically at their learning process from its inception to its completion . Reflection incorporates summarizing, evaluating, and inferring. When reflecting, students describe the steps they took to complete a task, focusing on their strategic action—the strategies and skills they used and the adjustments they made on their way toward their learning goal. They then make inferences about the influence of their actions on their outcomes to evaluate the effectiveness of those actions. Reflection is vital to fostering agency, self-efficacy, and independence, as it aids in building self-regulated learning skills: the ability to set goals and appraise tasks; monitor one’s learning progress; apply strategies as needed; and sustain motivation.

Reflection helps the learner to evaluate whether their approach to their learning was successful and to surface lessons about how they learn, which can help them in being successful in their next learning endeavor.

- What was my learning goal? Did I achieve my learning goal?

- How did I learn what I learned?

- What worked well as I learned? How do I know it worked well? What did not work as well as I wanted? How do I know it didn’t work well?

- What changes did I make on the fly? What was the effect of those changes?

- What did I learn about myself as a learner? How will this insight help me learn in the future?

- How did my thinking change as a result of my new learning?

- How can I use my new learning in the future?

If you are new to the idea of synthesis and reflection as a regular part of the learning process or if you want to bring more intention to how you craft questions, check out this self-assessment checklist for Synthesis & Reflection Prompt Design . To see it in action, check out this personal narrative unit outline that illustrates how the reflection and synthesis prompts at each key stage of the unit build in complexity as learners move through the stages of the learning cycle: making meaning, investigating, creating, and finally, presenting, celebrating, and reflecting.

Back in the spring, our first tip for meaningful learning in COVID was to FOCUS ON EVIDENCE OF LEARNING (not evidence of working). Reflecting back, focusing on evidence of learning is actually a fundamental practice for learning. Now that schools and districts are getting back to school after the emergency learning situation of the spring, but still in very different conditions than before, we have the opportunity to design learning experiences that better incorporate key ideas from the research on how we learn.

If you’re interested in hands-on learning and support to help you design learning experiences that are research-based and built around the learning cycle, check out this upcoming workshop series, The Learning Cycle Workshop , offered through reDesign’s Institute in October/November. We hope to see you there!

Join the community!

Sign up to receive our newsletter, access best-of educational resources, and stay in the know on upcoming events and learning opportunities. We hope to see you soon!

Share this Post

Sydney Schaef

More Posts by this Author

Related Insights

3 Takeaways From Competency-Based Design Research

Insights from a Youth Participant at SXSW

Igniting Curiosity

Explore our educator resources.

Check out reDesign’s curated collection of tools, resources, and guides to support educators in learner-centered communities. We’ve got learning activities, performance assessments, competency-based implementation tools, and formative tasks for learners of all ages!

South Shore took a professional learning community approach to refining and implementing a range of school-wide shifts, designed to make grading more fair, accurate, and helpful.The Fellow designated to lead this project served in an administrator role, and helped the school community coalesce around four areas for change: 1) developing a competency-based grade scale, 2) directly linking all assignments and grades to standards; 3) instituting a universal late work policy; and 4) implementing a revision policy focused on relearning. Background knowledge-building, feasibility discussions that incorporated community input, and formalizing a plan for change were all part of the journey, with the recognition that the school would adjust the plan along the way. In Year 2, communication, transparency with all stakeholders, and continued education have been essential, as well as continued solicitation of feedback as assessments were developed that aligned with the rollout of the new grade scale. Ultimately, South Shore is not only rethinking grading – the school is also rethinking work habits, remediation, assessments, instruction, and curriculum.

The Melrose High School team identified 3 anchor questions: How can assessments best serve student learning? What do we want our students to leave with? How can students drive and discuss their learning? Guided by these, they developed an integrated approach to 21st century grading that fosters equity by: (1) Supporting students’ Habits of Learning, across the academic program (2) Increasing accuracy and transparency in grading; (3) Developing new policies for Retaking and Revising Assessments, and establishing a minimum grade of 50%; (4) Proactively communicating; (5) Explicitly nurturing student voice; and (6) Adopting universal design principles for efficient assessment-building within a flexible environment.

Revere High School identified three “rethinking” arenas: 1) Clarify what it means for students to be proficient; 2) Ensure alignment with standards and other frameworks; 3) Develop consistent practices for grade calculations, the use of rubrics, and grade reporting. The pilot team collaborated to design a prototype for a common grading table, category weights connected to power standards, and a plan to develop assessments tied to those standards-based learning targets. This approach sharpens the focus on student proficiency, takes gradebook construction out of the hands of teachers and considers every step of “the what” in a more comprehensive way.

Revere High School, Part 2 – Developing a Culture of Competency: 72% of the students who attend Revere High School are learning English. A number of them have struggled to pass the MCAS (state’ graduation exam), and have also experienced course failure. As an extension of their #RethinkingGrading efforts, the District is designing a customized and personalized graduation pathway, guided by a Profile of a Graduate. To ensure teachers can effectively support students, the district is partnering with reDesign to develop and facilitate professional learning experiences and modularized courses: a commitment to developing a culture of competency for both young people and the adults who serve them.

- Teaching Tips

Bloom’s Taxonomy Question Stems For Use In Assessment [With 100+ Examples]

This comprehensive list of pre-created Bloom’s taxonomy question stems ensure students are critically engaging with course material

Jacob Rutka

![analysis and synthesis questions Bloom’s Taxonomy Question Stems For Use In Assessment [With 100+ Examples]](https://tophat.com/wp-content/uploads/bloomsstem-blog.png)

One of the most powerful aspects of Bloom’s Taxonomy is that it offers you, as an educator, the ability to construct a curriculum to assess objective learning outcomes, including advanced educational objectives like critical thinking. Pre-created Bloom’s Taxonomy questions can also make planning discussions, learning activities, and formative assessments much easier.

For those unfamiliar with Bloom’s Taxonomy, it consists of a series of hierarchical levels (normally arranged in a pyramid) that build on each other and progress towards higher-order thinking skills. Each level contains verbs, such as “demonstrate” or “design,” that can be measured to gain greater insight into student learning.

Click here to download 100+ Bloom’s taxonomy question stems for your classroom and get everything you need to engage your students.

Table of Contents

- Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956)

Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (2001)

Bloom’s taxonomy for adjunct professors, examples of bloom’s taxonomy question stems, additional bloom’s taxonomy example questions, higher-level thinking questions, bloom’s taxonomy (1956).

The original Bloom’s Taxonomy framework consists of six levels that build off of each other as the learning experience progresses. It was developed in 1956 by Benjamin Bloom, an American educational psychologist. Below are descriptions of each level:

- Knowledge: Identification and recall of course concepts learned

- Comprehension: Ability to grasp the meaning of the material

- Application: Demonstrating a grasp of the material at this level by solving problems and creating projects

- Analysis: Finding patterns and trends in the course material

- Synthesis: The combining of ideas or concepts to form a working theory

- Evaluation: Making judgments based on the information students have learned as well as their own insights

A group of educational researchers and cognitive psychologists developed the new and revised Bloom’s Taxonomy framework in 2001 to be more action-oriented. This way, students work their way through a series of verbs to meet learning objectives. Below are descriptions of each of the levels in revised Bloom’s Taxonomy:

- Remember: To bring an awareness of the concept to learners’ minds.

- Understand: To summarize or restate the information in a particular way.

- Apply: The ability to use learned material in new and concrete situations.

- Analyze: Understanding the underlying structure of knowledge to be able to distinguish between fact and opinion.

- Evaluate: Making judgments about the value of ideas, theories, items and materials.

- Create: Reorganizing concepts into new structures or patterns through generating, producing or planning.

Free Download: Bloom’s Taxonomy Question Stems and Examples

Bloom’s Taxonomy questions are a great way to build and design curriculum and lesson plans. They encourage the development of higher-order thinking and encourage students to engage in metacognition by thinking and reflecting on their own learning. In The Ultimate Guide to Bloom’s Taxonomy Question Stems , you can access more than 100 examples of Bloom’s Taxonomy questions examples and higher-order thinking question examples at all different levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956) question samples:

- Knowledge: How many…? Who was it that…? Can you name the…?

- Comprehension: Can you write in your own words…? Can you write a brief outline…? What do you think could have happened next…?

- Application: Choose the best statements that apply… Judge the effects of… What would result …?

- Analysis: Which events could have happened…? If … happened, how might the ending have been different? How was this similar to…?

- Synthesis: Can you design a … to achieve …? Write a poem, song or creative presentation about…? Can you see a possible solution to…?

- Evaluation: What criteria would you use to assess…? What data was used to evaluate…? How could you verify…?

Click here to get 100+ Bloom’s taxonomy question stems that’ll help engage students in your classroom.

Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (2001) question samples:

- Remember: Who…? What…? Where…? How…?

- Understand: How would you generalize…? How would you express…? What information can you infer from…?

- Apply: How would you demonstrate…? How would you present…? Draw a story map…

- Analyze: How can you sort the different parts…? What can you infer about…? What ideas validate…? How would you categorize…?

- Evaluate: What criteria would you use to assess…? What sources could you use to verify…? What information would you use to prioritize…? What are the possible outcomes for…?

- Create: What would happen if…? List the ways you can…? Can you brainstorm a better solution for…?

As we know, Bloom’s Taxonomy is a framework used in education to categorize levels of cognitive learning. Here are 10 Bloom’s Taxonomy example questions, each corresponding to one of the six levels in Bloom’s Taxonomy, starting from the lowest level (Remember) to the highest level (Create):

- Remember (Knowledge): What are the four primary states of matter? Can you list the main events of the American Civil War?

- Understand (Comprehension): How would you explain the concept of supply and demand to someone who is new to economics? Can you summarize the main idea of the research article you just read?

- Apply (Application): Given a real-world scenario, how would you use the Pythagorean theorem to solve a practical problem? Can you demonstrate how to conduct a chemical titration in a laboratory setting?

- Analyze (Analysis): What are the key factors contributing to the decline of a particular species in an ecosystem? How do the social and economic factors influence voting patterns in a specific region?

- Evaluate (Evaluation): Compare and contrast the strengths and weaknesses of two different programming languages for a specific project. Assess the effectiveness of a marketing campaign, providing recommendations for improvement.

- Create (Synthesis): Design a new and innovative product that addresses a common problem in society. Develop a comprehensive lesson plan that incorporates various teaching methods to enhance student engagement in a particular subject.

Download Now: Bloom’s Taxonomy Question Stems and Examples

Higher-level thinking questions are designed to encourage critical thinking, analysis, and synthesis of information. Here are eight examples of higher-level thinking questions that can be used in higher education:

- Critical Analysis (Analysis): “What are the ethical implications of the decision made by the characters in the novel, and how do they reflect broader societal values?”

- Problem-Solving (Application): “Given the current environmental challenges, how can we develop sustainable energy solutions that balance economic and ecological concerns?”

- Evaluation of Evidence (Evaluation): “Based on the data presented in this research paper, do you think the study’s conclusions are valid? Why or why not?”

- Comparative Analysis (Analysis): “Compare and contrast the economic policies of two different countries and their impact on income inequality.”

- Hypothetical Scenario (Synthesis): “Imagine you are the CEO of a multinational corporation. How would you navigate the challenges of globalization and cultural diversity in your company’s workforce?”

- Ethical Dilemma (Evaluation): “In a medical emergency with limited resources, how should healthcare professionals prioritize patients, and what ethical principles should guide their decisions?”

- Interdisciplinary Connection (Synthesis): “How can principles from psychology and sociology be integrated to address the mental health needs of a diverse student population in higher education institutions?”

- Creative Problem-Solving (Synthesis): “Propose a novel solution to reduce urban congestion while promoting eco-friendly transportation options. What are the potential benefits and challenges of your solution?”

These questions encourage students to go beyond simple recall of facts and engage in critical thinking, analysis, synthesis, and ethical considerations. They are often used to stimulate class discussions, research projects, and written assignments in higher education settings.

Click here to download 100+ Bloom’s taxonomy question stems

Recommended Readings

25 Effective Instructional Strategies For Educators

The Complete Guide to Effective Online Teaching

Subscribe to the top hat blog.

Join more than 10,000 educators. Get articles with higher ed trends, teaching tips and expert advice delivered straight to your inbox.

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

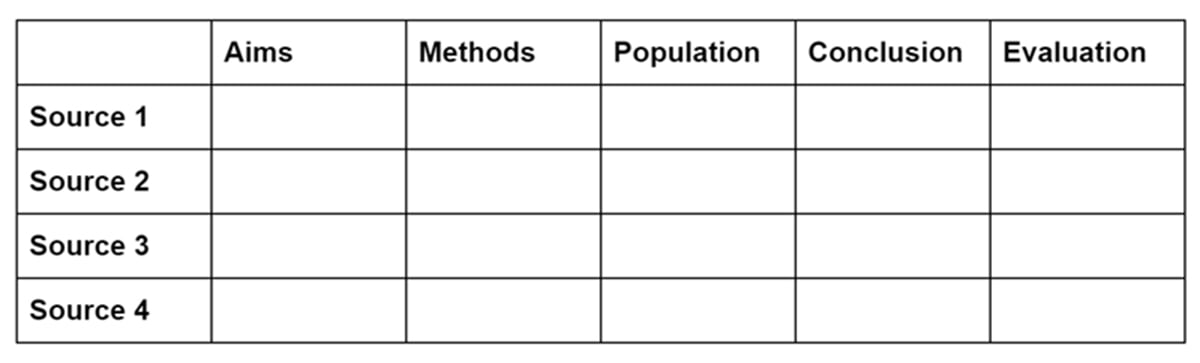

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

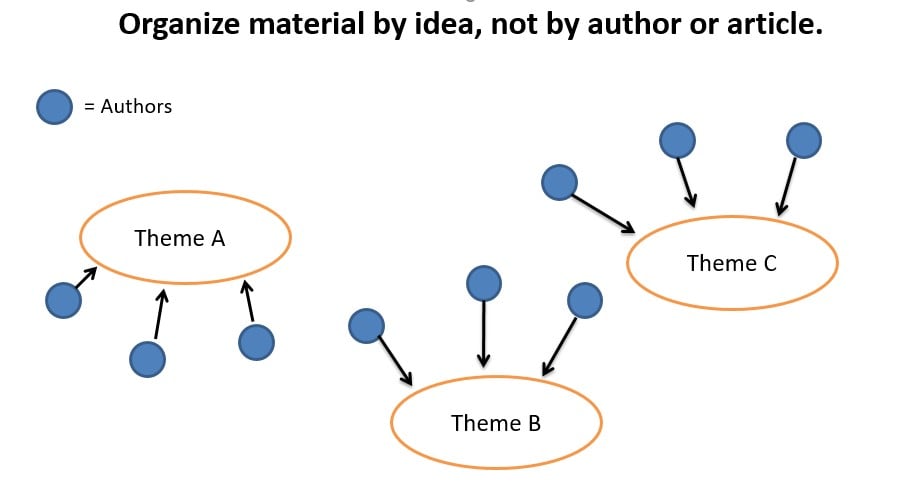

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Related Articles

Student Resources

How To Cite A YouTube Video In APA Style – With Examples

How to Write an Abstract APA Format

APA References Page Formatting and Example

APA Title Page (Cover Page) Format, Example, & Templates

How do I Cite a Source with Multiple Authors in APA Style?

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Analysis vs. Synthesis

What's the difference.

Analysis and synthesis are two fundamental processes in problem-solving and decision-making. Analysis involves breaking down a complex problem or situation into its constituent parts, examining each part individually, and understanding their relationships and interactions. It focuses on understanding the components and their characteristics, identifying patterns and trends, and drawing conclusions based on evidence and data. On the other hand, synthesis involves combining different elements or ideas to create a new whole or solution. It involves integrating information from various sources, identifying commonalities and differences, and generating new insights or solutions. While analysis is more focused on understanding and deconstructing a problem, synthesis is about creating something new by combining different elements. Both processes are essential for effective problem-solving and decision-making, as they complement each other and provide a holistic approach to understanding and solving complex problems.

Further Detail

Introduction.

Analysis and synthesis are two fundamental processes in various fields of study, including science, philosophy, and problem-solving. While they are distinct approaches, they are often interconnected and complementary. Analysis involves breaking down complex ideas or systems into smaller components to understand their individual parts and relationships. On the other hand, synthesis involves combining separate elements or ideas to create a new whole or understanding. In this article, we will explore the attributes of analysis and synthesis, highlighting their differences and similarities.

Attributes of Analysis

1. Focus on details: Analysis involves a meticulous examination of individual components, details, or aspects of a subject. It aims to understand the specific characteristics, functions, and relationships of these elements. By breaking down complex ideas into smaller parts, analysis provides a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

2. Objective approach: Analysis is often driven by objectivity and relies on empirical evidence, data, or logical reasoning. It aims to uncover patterns, trends, or underlying principles through systematic observation and investigation. By employing a structured and logical approach, analysis helps in drawing accurate conclusions and making informed decisions.

3. Critical thinking: Analysis requires critical thinking skills to evaluate and interpret information. It involves questioning assumptions, identifying biases, and considering multiple perspectives. Through critical thinking, analysis helps in identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter.

4. Reductionist approach: Analysis often adopts a reductionist approach, breaking down complex systems into simpler components. This reductionist perspective allows for a detailed examination of each part, facilitating a more in-depth understanding of the subject matter. However, it may sometimes overlook the holistic view or emergent properties of the system.

5. Diagnostic tool: Analysis is commonly used as a diagnostic tool to identify problems, errors, or inefficiencies within a system. By examining individual components and their interactions, analysis helps in pinpointing the root causes of issues, enabling effective problem-solving and optimization.

Attributes of Synthesis

1. Integration of ideas: Synthesis involves combining separate ideas, concepts, or elements to create a new whole or understanding. It aims to generate novel insights, solutions, or perspectives by integrating diverse information or viewpoints. Through synthesis, complex systems or ideas can be approached holistically, considering the interconnections and interdependencies between various components.

2. Creative thinking: Synthesis requires creative thinking skills to generate new ideas, concepts, or solutions. It involves making connections, recognizing patterns, and thinking beyond traditional boundaries. By embracing divergent thinking, synthesis enables innovation and the development of unique perspectives.

3. Systems thinking: Synthesis often adopts a systems thinking approach, considering the interactions and interdependencies between various components. It recognizes that the whole is more than the sum of its parts and aims to understand emergent properties or behaviors that arise from the integration of these parts. Systems thinking allows for a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena.

4. Constructive approach: Synthesis is a constructive process that builds upon existing knowledge or ideas. It involves organizing, reorganizing, or restructuring information to create a new framework or understanding. By integrating diverse perspectives or concepts, synthesis helps in generating comprehensive and innovative solutions.

5. Design tool: Synthesis is often used as a design tool to create new products, systems, or theories. By combining different elements or ideas, synthesis enables the development of innovative and functional solutions. It allows for the exploration of multiple possibilities and the creation of something new and valuable.

Interplay between Analysis and Synthesis

While analysis and synthesis are distinct processes, they are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they often complement each other and are interconnected in various ways. Analysis provides the foundation for synthesis by breaking down complex ideas or systems into manageable components. It helps in understanding the individual parts and their relationships, which is essential for effective synthesis.

On the other hand, synthesis builds upon the insights gained from analysis by integrating separate elements or ideas to create a new whole. It allows for a holistic understanding of complex phenomena, considering the interconnections and emergent properties that analysis alone may overlook. Synthesis also helps in identifying gaps or limitations in existing knowledge, which can then be further analyzed to gain a deeper understanding.

Furthermore, analysis and synthesis often involve an iterative process. Initial analysis may lead to the identification of patterns or relationships that can inform the synthesis process. Synthesis, in turn, may generate new insights or questions that require further analysis. This iterative cycle allows for continuous refinement and improvement of understanding.

Analysis and synthesis are two essential processes that play a crucial role in various fields of study. While analysis focuses on breaking down complex ideas into smaller components to understand their individual parts and relationships, synthesis involves integrating separate elements or ideas to create a new whole or understanding. Both approaches have their unique attributes and strengths, and they often complement each other in a cyclical and iterative process. By employing analysis and synthesis effectively, we can gain a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena, generate innovative solutions, and make informed decisions.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

Module 8: Writing Workshop—Analysis and Synthesis

Why it matters: writing workshop—analysis and synthesis.

Figure 1 . Effective scholarship is often a matter of making connections.

Why Analyze?

In college courses, you will be asked to read, reason, and write analytically. Effective analysts can distinguish the whole, identify parts, infer relationships, and make generalizations. Those skills enable individuals to connect ideas, detect inconsistencies, and solve problems in a systematic fashion. Understanding what analysis is, how to apply it, and how to convey the results effectively will be invaluable to you throughout your college and professional careers.

Analysis is at the heart of academic work in every area of study. Literary critics break down poems and novels, examining how the different parts of the text work together to create meaning. Sociologists conduct field research to observe how gender roles influence pay discrepancies in developing nations, often arriving at policy recommendations that might result in more equitable arrangements. Business students scrutinize data on consumer behavior in different markets to better understand why some products fail in one place while nearly identical ones succeed in a different place.

Note that each researcher started with a question. The literary critic asks: how does this text create meaning? The sociologist wants to know: how are gender and inequalities of pay related to broader economic development? And the business student is trying to get a sense of what regional market differences might account for success or failure for a given plan. The work of analysis gives each researcher an opportunity to complicate their initial question, to compile useful information, and then to draw–or infer–some conclusions based on this new, more thorough level of understanding.

While analysis is the term we use to describe the process of breaking something down, say a poem or novel, a transcript of interviews with workers and business owners, or a regional market overview, this is not the only work we perform as scholars.

In an academic context, we are often occupied by a kind of transaction. As students we demonstrate our learning in exchange for credits, and ultimately we redeem these credits for a degree. And while there is certainly nothing wrong with learning for its own sake, without any broader framework of approval or evaluation, if you are working toward a degree it is helpful to understand why your professors value particular demonstrations of ability. In short, your teachers are looking for complexity and thoroughness in your thinking and writing. They want to see that you can propose and sustain a defensible line of inquiry, and that you can select and utilize appropriate evidence to support your guiding questions.

But how, exactly, do you utilize your material? Two complicating techniques that you can employ, and that will increase the complexity and credibility of your work are inference and synthesis. Let’s say that our hypothetical sociologist writes a draft of her paper that describes the types of labor performed by men and women in different lines of work in a recently urbanized region. If she categorically breaks down and examines in detail these differently compensated positions, we can say that she has performed an analysis. However, if she cites her interview transcripts and argues that her subjects are implying that pay rates in newly established professional settings should be based on “traditional” pay rates from earlier forms of gender-segregated agricultural labor, then she has inferred this is an unspoken framework of inequality in need of more scrutiny. Her inference has complicated and built on the existing analysis. If she goes on to find similarities in this notion of “traditionally” gender-based pay discrepancies among company mission statements, her interview transcripts, and studies conducted by other sociologists in other developing countries, then she has synthesized these different viewpoints and sources. This will also demonstrate a more thorough and credible thought process, and one that is valued within her chosen academic discipline.

As we work through the next few pages you will have an opportunity to consider how analysis, inference, and synthesis can work together. You will also get to test your own ability to identify these concepts in action, and to practice applying them to a scholarly essay.

Writing Workshop: Your Working Document

Every component of the working document will be introduced throughout this module in a blue box such as this one. Open your working document now and keep it open as you progress through the module .

- Go to the assignment for this module in your LMS. Click on the link to open the Working Document for this module as a Google Document.

- Now hold onto this document—we’ll need it soon! (You’ll submit the link to your instructor once you’ve completed the Writing Workshop activities).

- Photograph of Women Working at a Bell System Telephone Switchboard. Provided by : The U.S. National Archives. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/6zqGGV . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Why It Matters: Writing Workshopu2014Analysis and Synthesis. Authored by : Scott Barr for Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- AIMS Public Health

- v.3(1); 2016

What Synthesis Methodology Should I Use? A Review and Analysis of Approaches to Research Synthesis

Kara schick-makaroff.

1 Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Marjorie MacDonald

2 School of Nursing, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

Marilyn Plummer

3 College of Nursing, Camosun College, Victoria, BC, Canada

Judy Burgess

4 Student Services, University Health Services, Victoria, BC, Canada

Wendy Neander

Associated data, additional file 1.

When we began this process, we were doctoral students and a faculty member in a research methods course. As students, we were facing a review of the literature for our dissertations. We encountered several different ways of conducting a review but were unable to locate any resources that synthesized all of the various synthesis methodologies. Our purpose is to present a comprehensive overview and assessment of the main approaches to research synthesis. We use ‘research synthesis’ as a broad overarching term to describe various approaches to combining, integrating, and synthesizing research findings.

We conducted an integrative review of the literature to explore the historical, contextual, and evolving nature of research synthesis. We searched five databases, reviewed websites of key organizations, hand-searched several journals, and examined relevant texts from the reference lists of the documents we had already obtained.

We identified four broad categories of research synthesis methodology including conventional, quantitative, qualitative, and emerging syntheses. Each of the broad categories was compared to the others on the following: key characteristics, purpose, method, product, context, underlying assumptions, unit of analysis, strengths and limitations, and when to use each approach.

Conclusions

The current state of research synthesis reflects significant advancements in emerging synthesis studies that integrate diverse data types and sources. New approaches to research synthesis provide a much broader range of review alternatives available to health and social science students and researchers.

1. Introduction

Since the turn of the century, public health emergencies have been identified worldwide, particularly related to infectious diseases. For example, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Canada in 2002-2003, the recent Ebola epidemic in Africa, and the ongoing HIV/AIDs pandemic are global health concerns. There have also been dramatic increases in the prevalence of chronic diseases around the world [1] – [3] . These epidemiological challenges have raised concerns about the ability of health systems worldwide to address these crises. As a result, public health systems reform has been initiated in a number of countries. In Canada, as in other countries, the role of evidence to support public health reform and improve population health has been given high priority. Yet, there continues to be a significant gap between the production of evidence through research and its application in practice [4] – [5] . One strategy to address this gap has been the development of new research synthesis methodologies to deal with the time-sensitive and wide ranging evidence needs of policy makers and practitioners in all areas of health care, including public health.

As doctoral nursing students facing a review of the literature for our dissertations, and as a faculty member teaching a research methods course, we encountered several ways of conducting a research synthesis but found no comprehensive resources that discussed, compared, and contrasted various synthesis methodologies on their purposes, processes, strengths and limitations. To complicate matters, writers use terms interchangeably or use different terms to mean the same thing, and the literature is often contradictory about various approaches. Some texts [6] , [7] – [9] did provide a preliminary understanding about how research synthesis had been taken up in nursing, but these did not meet our requirements. Thus, in this article we address the need for a comprehensive overview of research synthesis methodologies to guide public health, health care, and social science researchers and practitioners.