Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 01 August 1997

Researching alternative medicine

- Wayne B. Jonas 1

Nature Medicine volume 3 , pages 824–827 ( 1997 ) Cite this article

132 Accesses

28 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

In 1992 the US Congress created the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM), placing it within the NIH, one of the foremost bio-medical research establishments world-wide. The OAM is currently funded to the tune of $40 million per year. Although alternative and unconventional medicine attracts considerable attention (and finances) from the public in Western societies, many within the established medical and research communities are outwardly cynical and dismissive of alternative medical practices. We have asked Wayne B. Jonas. Director of the OAM, to discuss what the OAM hopes to achieve and how it is going about it.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Eisenberg, D.M., Kessler, R.C., Foster, C., Norlock, F.E., Calkins, D.R., Delbanco, T.L. Unconventional medicine in the United States - prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N. Engl. J. Med. , 328 , 246–252 (1993).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fisher, P. & Ward, A. Complementary medicine in Europe. British Medical Journal. 309 , 107–111 (1994).

MacLennan, A.H., Wilson, D.H. & Taylor, A.W. Prevalence and cost of alternative medicine in Australia. Lancet. 347 , 569–573 (1996).

Cassileth, B.R., Lussk, E.J., Strouss, T.B. & Bodenheimer, B.J. Contemporary unorthodox treatments in cancer medicine: a study of patients, treatments, and practitioners. Annals Int. Med. 101 , 105–112 (1984).

Anderson, W.H. et al . Patient use and assessment of conventional and alternative therapies for HIV infection and AIDS. AIDS. 74 , 561–564 (1993).

Article Google Scholar

Blumberg, D.L., Grant, W.D., Hendricks, S.R., Kamps, C.A. & Dewan, M.J. The physician and unconventional medicine. Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine. 1 , 31–35 (1995).

CAS Google Scholar

Ernst,, E. Complementary medicine: what physicians think of it: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 155 , 2405–2408 (1995).

Halliday, J., Taylor, M., Jenkins, A. & Reilly, D. Medical students and complementary medicine. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 1 (suppl), 32–33 (1993).

Google Scholar

Carlston, M., Stuart, M. & Jonas, W. Alternative Medicine Instruction in American Medical Schools and Family Medicine Residency Programs. Fam. Med. (in the press) (1997).

Description PoDa. Defining and describing complementary and alternative medicine. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 3 , 49–57 (1997).

Furnham, A. & Forey, J. The attitudes, behaviors and beliefs of patients of conventional vs. complementary (alternative) medicine. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 50 , 458–469 (1994).

Kleijnen, J. & Knipschild, P. Gingko biloba for cerebral insufficiency. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 34 , 352–358 (1992).

Di Silverio, F. et al . Plant extracts in BPH. Minerva Urologica e Nefrologica 45 , 143–49 (1993).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Neil, A. & Silagy, C. Garlic: Its cardio-protective properties. Curr. Opin. Lipid. 5 , 6–10 (1994).

Linde, K., Ramirez, G., Mulrow, C.D., Pauls, A., Weidenhammer, W. & Melchart, D. St John's wort for depression — an overview and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials [see comments]. Br. Med. J. 313 , 253–258 (1996).

Gibson, R.G., Gibson, S., MacNeill, A.D. & Watson, B.W. Homeopathic therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: Evaluation by double-blind clinical therapeutical trial. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 9 , 453–459 (1980).

Berman, B.M. et al . Efficacy of traditional Chinese acupuncture in the treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: A pilot study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 3 , 139–142 (1995).

Jonas, W.B., Rapoza, C.P. & Blair, W.F. The effect of niacinamide on osteoarthritis: A pilot study. Inflammation Research. 45 , 330–334 (1996).

Tao, X.L., Dong, Y. & Zhang, N.Z. A double-blind study of T2 (tablets of polygly-cosides of Tripterygium wilfodii hook) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. [Chinese]. Chung-Hua Nei Ko Tsa Chih Chinese Journal of Internal Medicine. 26 , 399–402, 444–445 (1987).

Altman, R.D. et al . Capsaicin cream 0.025% as monotherapy for osteoarthritis: A double-blind study. Seminars in Arthritis & Rheumatism. 23 (suppl) 25–33 (1994).

Kjeldsen-Kragh, J. et al . Changes in laboratory variables in rheumatoid arthritis patients during a trial of fasting and one-year vegetarian diet. Scand J Rheumatol. 24 , 85–93 (1995).

Lavigne, J.V., Ross, C.K., Berry, S.L., Hayford, J.R. & Pachman, L.M. Evaluation of a psychological treatment package for treating pain in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 5 , 101–110 (1992).

Assendelft, W.J., Koes, B.W., Knipschild, P.G. & Bouter, L.M. The relationship between methodological quality and conclusions in reviews of spinal manipulation. JAMA 274 , 1942–1948 (1995).

Ader, R. Conditioned Immunopharmacological effects in animals: Implications for a conditioning model of pharmacotherapy. In: White, L., Tursky, B., Schwartz, G.E., editors. Placebo Theory, Research and Mechanisms (The Guilford Press) 306–323 (New York, 1985).

Vickers, A.J. Can acupuncture have specific effects on health? A systematic review of acupuncture antiemesis trials. J. R. Soc. Med. 89 , 303–311 (1996).

Dowie, J. Evidence based medicine. Needs to be within framework of decision making based on decision analysis. Br. Med. J. 313 , 170–171 (1996).

Methods PoRGa. How should we research unconventional therapies? Int. J. Tech. Assess. Health Care 13 , 111–121 (1997).

Davenas, E. et al . Human basophil degranulation triggered by very dilute anti-serum against IgE. Nature 333 , 816–818 (1988).

Kleijnen, J., Knipschild, P. & Rietter, G. Clinical trials of homoeopathy. Br. Med. J. 302 , 316–323 (1991).

Linde, K. et al . Critical review and meta-analysis of serial agitated dilutions in experimental toxicology. Human and Experimental Toxicology 13 , 481–492 (1994).

Boissel, J.P., Cucherat, M., Haugh, M. & Gauthier, E. Critical literature review on the effectiveness of homoeopathy: overview of data from homoeopathic medicine trials. Brussels: Homoeopathic Medicine Research Group. Report to the European Commission, 1996.

Radin, D.I. & Nelson, R.D. Evidence for Consciousness-Related Anomalies in Random Physical Systems. Found. Physics 19 , 1499–1514 (1989).

Braud, W.G. & Schlitz, M.J. Consciousness interactions with remote biological systems: Anomalous intentionality effects. Subtle Energies 2 , 1–46 (1992).

Bern, D.J. & Honorton, C. Does psi exist? Replicable evidence for anomalous information transfer. Psychological Bulletin 115 , 4–18 (1994).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Director, Office of Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health, 9000 Rockville Pike, Building 31, Room 5B35 MSC 2182, Bethesda, Maryland, 20892, USA

Wayne B. Jonas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Jonas, W. Researching alternative medicine. Nat Med 3 , 824–827 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0897-824

Download citation

Issue Date : 01 August 1997

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0897-824

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Herbal biomedicines: a new opportunity for aquaculture industry.

- Thavasimuthu Citarasu

Aquaculture International (2010)

What is the state of the evidence on the mind–cancer survival question, and where do we go from here? A point of view

- Joanne E. Stephen

- Michelle Rahn

Supportive Care in Cancer (2007)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Alternative Medicine and Healthcare Delivery: A Narrative Review

- First Online: 07 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Ibrahim Adekunle Oreagba 3 &

- Kazeem Adeola Oshikoya 4

456 Accesses

1 Altmetric

The global trend toward increased acceptability and use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs), across all age groups, is well documented in the literature. Consequently, further systematic evaluation and meta-analysis are necessary to evaluate the quality, efficacy, safety, and regulation of these range of therapies by combining all the available evidence in the literature. Furthermore, the role of CAM in healthcare delivery and its utilization in a digital age cannot be overemphasized. Evidence-based results would guide both patients willing to use CAMs and their providers in making an informed decision. This narrative review addressed the above points. There is subtle evidence supporting the quality, efficacy, and safety of CAM therapies and products; however, much of the evidence is inconsistent due to the varied CAM types and regulatory policies from country to country. More research is required in this field to further harness the gains of CAM therapies and products globally. CAM users and providers should exercise caution with the available therapies and products. Care should also be taken when consulting CAM therapies online.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Adib-Hajbaghery, M., & Hoseinian, M. (2014). Knowledge, attitude and practice toward complementary and traditional medicine among Kashan health care staff. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 22 , 126–132.

Google Scholar

Allen, D., Bilz, M., Leaman, D. J., Miller, R. M., Timoshyna, A., & Window, J. (2014). European red list of medicinal . Publications Office of the European Union.

Aronson, J. K. (2016). Meyler’s side effects of drugs (16th ed. pp. 488–424). Elsevier Publishing House.

Ayoubi, R. A., Nassour, N. S., Saidy, E. G., Aouad, D. K., Maalouly, J. S., & Daou, E. B. (2020). Physical manipulation-induced femoral neck fracture: A case report. Case Reports in Orthopaedic Research, 3 , 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1159/000509704

Article Google Scholar

Barnes, J. (2003). Quality, efficacy and safety of complementary medicines: Fashions, facts and the future. Part I. Regulation and quality. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 55 , 226–233.

Bent, S., Tiedt, T. N., Odden, M. C., & Shlipak, M. G. (2003). The relative safety of ephedra compared with other herbal products. Annals of Internal Medicine, 138 , 468–471.

Bordes, C., Leguelinel-Blache, G., Lavigne, J. P., Mauboussin, J. M., Laureillard, D., Faure, H., Rouanet, I., Sotto, A., & Loubet, P. (2020). Interactions between antiretroviral therapy and complementary and alternative medicine: A narrative review. Clinical Microbiology and Infection., 26 (9), 1161–1170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.019.p420-421

Bouziri, A., Hamdi, A., Menif, K., & Ben Jaballah, N. (2010). Hepatorenal injury induced by cutaneous application of Atractylis gummifera L. Clin Toxicol (Phila), 48 (7), 752–754. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2010.498379 . PMID: 20615152.

Bowden, D., Goddard, L., & Gruzelier, J. (2011). A randomized controlled single-blind trial of the efficacy of reiki at benefitting mood and well-being. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 2011 , 381862. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/381862

Campbell-Hall, V., Petersen, I., Bhana, A. et al. (2010). Collaboration between traditional practitioners and primary health care staff in South Africa: Developing a workable partnership for community mental health services. Transcultural Psychiatry, 47 , 610–628.

Charnock, D., Shepperd, S., Needham, G., & Gann, R. (1999). DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 53 (2), 105–111.

Chitindingu, E., George, G., & Gow, J. (2014). A review of the integration of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine into the curriculum of South African medical schools. BMC Medical Education, 14 , 40.

Colombo, F., Di Lorenzo, C., Biella, S., Vecchio, S., Frigerio, G., & Restani, P. (2020). Adverse effects to food supplements containing botanical ingredients. Journal of Functional Foods, 72 ,. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2020.103990

De Maat, M. M. R., Hoetelmans, R. M. W., Mathôt, R. A. A., van Gorp, E. C. M., Meenhorst, P. L., Mulder, J. W., & Beijnen, J. H. (2001). Drug interaction between St John’s wort and nevirapine. AIDS, 15 (3).

Dwyer, J. T., Coates, P. M., & Smith, M. J. (2018). Dietary supplements: Regulatory challenges and research resources. Nutrients, 10 (1), 41. Published 2018 Jan 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010041

Eisenberg, D. M., Davis, R., Ettner, S. L., Appel, S., Wilkey, S., Van Rompay, M., et al. (1998). Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States 1990–1997. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280 , 1569–1575.

Ekor, M. (2014). The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 4 , 177.

Ernst, E., & Thompson-Coon, J. (2002). Heavy metals in traditional Chinese medicines: A systematic review. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 70 (6), 497–504. https://doi.org/10.1067/mcp.2001.120249

European Medicines Agency. Compilation of Union Procedures on Inspections and Exchange of Information. 21 September 2021, EMA/INS/428126/2021, Rev 18, Inspections Office, Quality and Safety of Medicines Department. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/compilation-union-procedures-inspections-exchange-information_en.pdf (Accessed 30 March 2022).

Frass, M., Strassl, R. P., Friehs, H., Müllner, M., Kundi, M., & Kaye, A. D. (2012). Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: A systematic review. The Ochsner Journal, 12 , 45–56. Google Scholar | Medline

Fjær, E. L., Landet, E. R., McNamara, C. L. (2020). The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in Europe. BMC Complement Med Ther, 20 , 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-020-02903-w

Food Drug and Administration. (2016). Dietary supplements: New dietary ingredient notifications and related issues: Guidance for Industry April 1.

Food Drugs and Administration. Alerts, Advisories and Safety Information: Food, Beverages, Dietary Supplements, and Infant Formula . Available at https://www.fda.gov/food/recalls-outbreaks-emergencies/alerts-advisories-safety-information (Accessed 29 March 2022).

Forsyth, A., Blamey, G., Lobet, S., & McLaughlin, P. (2020). Practical guidance for nonspecialist physical therapists managing people with hemophilia and musculoskeletal complications. Health, 12 (2), 158–179.

Goksu, E., Kilic, T., & Yilmaz, D. (2012). Hepatitis: A herbal remedy Germander. Clinical Toxicology, 50 (2), 158. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2011.647993

Guido, P. C., Ribas, A., Gaioli, M., Quattrone, F., & Macchi, A. (2015). The state of the integrative medicine in Latin America: The long road to include complementary, natural, and traditional practices in formal health systems. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 7 , 5–12.

Health Canada. (2016). About natural health product regulation in Canada . Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/natural-nonprescription/regulation.html (Accessed 31 March 2022).

Hofgard, M. W., & Zipin, M. L. (1999) Complementary and alternative medicine--a business opportunity? Medical Group Management Journal, 46 (3), 16–24, 26–7. PMID: 10539335.

Horrigan, B., Lewis, S., Abrams, D. I., & Pechura, C. (2012). Integrative medicine in America—How integrative medicine is being practiced in clinical centers across the United States. Global Advances in Health and Medicine 1 (3), 18–94. https://doi.org/10.7453/gahmj.2012.1.3.006

Hudson, A., Lopez, E., Almalki, A. J., Roe, A. L., & Calderón, A. I. (2018). A review of the toxicity of compounds found in herbal dietary supplements. Planta Medica, 84 (9–10), 613–626. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0605-3786 . Epub 2018 Apr 19.

James, P. B., Wardle, J., Steel, A., & Adams, J. (2018). Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMJ Global Health, 3 , e000895. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000895

Kasilo, O. M., Trapsida, J.-M., & Mwikisa Ngenda, C. (2010) An overview of the traditional medicine situation in the African region. African Health Monitor , 7–15.

Kalumbi, M. H., Likongwe, M. C., Mponda, J., Zimba, B. L., Phiri, O., Lipenga, T., Mguntha, T., & Kumphanda, J. (2020). Bacterial and heavy metal contamination in selected commonly sold herbal medicine in Blantyre, Malawi. Malawi Medical Journall, 32 (3), 153–159.

Keshari P. (2021). Controversy, adulteration and substitution: Burning problems in ayurveda practices. In H. El-Shemy (Ed.), Medicinal plants from nature [Working Title] [Internet]. IntechOpen; [cited 2022 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/77108 . https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.98220

Komlaga, G., Agyare, C., Dickson, R. A., Mensah, M. L. K., Annan, K., &, Loiseau, P. M. (2015). Medicinal plants and finished marketed herbal products used in the treatment of malaria in the Ashanti region, Ghana. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 4 , 172:333–346.

LiverTox. (2017). Clinical and research information on drug-Induced liver injury [Internet]. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-. Chaparral. [Updated 2017 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548355/

LiverTox. (2018). Clinical and research information on drug-Induced liver injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-. Jin Bu Huan. [Updated 2018 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548147/

LiverTox. (2020). Clinical and research information on drug-Induced liver injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-. Pennyroyal Oil. [Updated 2020 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548673/

Luo, L., Wang, B., Jiang, J., Fitzgerald, M., Huang, Q., Yu, Z., Li, H., Zhang, J., Wei, J., Yang, C., Zhang, H., Dong, L., & Chen, S. (2020). Heavy metal contaminations in herbal medicines: Determination, comprehensive risk assessments, and solutions. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 14 (11), 595335. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.595335.PMID:33597875;PMCID:PMC7883644

Ministry for Primary Industries. (2016). Food standard: New Zealand food (supplemented food) standard, 2016 (2016) https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/11365-new-zealand-food-supplemented-food-standard-2016 (Accessed 31 March 2022).

Mingzhe, X., Baobin, H., Fang, G., Chenchen, Z., Yueying, Y., Lulu, L., Wenya, W., & Luwen. (2019). Assessment of adulterated traditional Chinese medicines in China: 2003–2017. Front Pharmacol (10). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.01446

National Center on Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). (2005). Energy medicine: An overview . Backgrounders; NCCIH: Rockville Pike, MD, USA.

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). Alerts and advisories . Available at https://www.nccih.nih.gov/news/alerts (Accessed 29 March 2022).

National Institute of Health. (2005a). Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 7, Integration of CAM and Conventional Medicine. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83807/

National Institute of Health. (2005b). Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 5, State of Emerging Evidence on CAM. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83790/

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (2020). Natural Does not Necessarily Mean Safer, or Better [Internet]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [cited 2020 May 24]. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/know-science/natural-doesnt-mean-better .

Neuman, M. G., Cohen, L., Opris, M., Nanau, R. M., & Hyunjin, J. (2015). Hepatotoxicity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences, 18 (4), 825–843. https://doi.org/10.18433/j3bg7j PMID: 26626258.

Newmaster, S. G., Grguric, M., Shanmughanandhan, D., et al. (2013). DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products. BMC Medicine, 11 , 11–222.

Ng, J. Y., Munford, V., & Thakar, H. (2020). Web-based online resources about adverse interactions or side effects associated with complementary and alternative medicine: A systematic review, summarization and quality assessment. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 20 , 290. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-01298-5

Ng, J. Y. (2020). The regulation of complementary and alternative medicine professions in Ontario. Canada. Integrative Medicine Research, 9 (1), 12–16.

Nielsen, A., Tick, H., Mao, J. J., & Hecht, F. (2019). Consortium pain task force. Academic consortium for integrative medicine & health commentary to CMS; RE: National Coverage Analysis (NCA) Tracking Sheet for Acupuncture for Chronic Low Back Pain (CAG-00452N). Global Advance Health and Medicine,8 , 2164956119857648. Published 2019 Jul 11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2164956119857648 .

Oshikoya, K. A., Oreagba, I. A., Ogunleye, O. O., et al. (2014). Use of complementary medicines among HIV-infected children in Lagos. Nigeria. Complement Ther Clin Pract, 20 , 118–124.

Oshikoya, K. A., Oreagba, I. A., Ogunleye, O. O., Oluwa, R., Senbanjo, I. O., & Olayemi, S. O. (2013). Herbal medicines supplied by community pharmacies in Lagos, Nigeria: Pharmacists’ knowledge. Pharmacy Practice, 11 (4), 219–227.

Oreagba, I. A., Kazeem Adeola Oshikoya and Mercy Amachree. (2011). Herbal medicine use among urban residents in Lagos, Nigeria BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 11, 117. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/11/117 .

Paoloni, M., Agostini, F., Bernasconi, S., Bona, G., Cisari, C., Fioranelli, M., Invernizzi, M., Madeo, A., Matucci-Cerinic, M., Migliore, A., Quirino, N., Ventura, C., Viganò, R., & Bernetti, A. (2022). Information survey on the use of complementary and alternative medicine. Medicina (Kaunas), 14 , 58(1), 125.

Robinson, M. M., & Zhang, X. (2011a). Traditional medicines: Global situation, issues and challenges. In Proceedings of the world medicines situation. World Health Organization, pp. 1–14. https://digicollection.org/hss/documents/s18063en/s18063en.pdf .

Robinson, M. M., & Zhang, X. (2011b) Traditional medicines: Global situation, issues and challenges. In: Proceedings of the world medicines situation. World Health Organization, pp. 1–14. https://digicollection.org/hss/documents/s18063en/s18063en.pdf .

Pantano, F., Mannocchi, G., Marinelli, E., Gentili, S., Graziano, S., Busardò, F. P., & di Luca, N. M. (2017). Hepatotoxicity induced by greater celandine (Chelidonium majus L.): A review of the literature. European Review Medical and Pharmacol ogical Sciences, 21 (1 Suppl), 46–52. PMID: 28379595.

Paoloni, M., Agostini, F., Bernasconi, S., Bona, G., Cisari, C., Fioranelli, M., Invernizzi, M., Madeo, A., Matucci-Cerinic, M., Migliore, A., Quirino, N., Ventura, C., Viganò, R., & Bernetti, A. (2022). Information survey on the use of complementary and alternative medicine. Medicina (kaunas, Lithuania), 58 (1), 125.

Perez-Garcia, M., & Figueras, A. (2011). The lack of knowledge about the voluntary reporting system of adverse drug reactions as a major cause of underreporting: Direct survey among health professionals. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety, 20 (12), 1295–1302.

Raman, A., & Lau, C. (1996). Anti-diabetic properties and phytochemistry of Momordica charantia L. (Cucurbitaceae). Phytomedicine, 2 (4), 349–362.

Robinson, N. (2006). Integrated traditional Chinese medicine. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 12 (2), 132–140.

Romm, A. (2009, May 22). Botanical medicine for women’s health E-Book . Elsevier Health Sciences .

Sambo, L. (2011). Health systems and primary health care in the African region. African Health Monitor 14, 2–3.

Sbaffi, L., & Rowley, J. (2017). Trust and credibility in web-based health information: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19 (6), e218.

Schulz, V., Hänsel, R., & Tyler, V. E. (2000). Rational Phytotherapy. A Physicians’ Guide to Herbal Medicine (4th ed.). Springer.

Sharad, S., Manish, P., Mayank, B., Mitul, C., & Sanjay, S. (2011). Regulatory status of traditional medicines in Africa Region. International Journal of Research in Ayurveda and Pharmacy 2 (1), 103–110.

Sharma, O. P., Sharma, S., Pattabhi, V., Mahato, S. B., & Sharma, P. D. A. (2007). Review of the hepatotoxic plant Lantana camara. Critical Reviews in Toxicology., 37 , 313–352.

Sharples, F. M., van Haselen, R., & Fisher, P. (2003). NHS patients’ perspective on complementary medicine: A survey. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 11 , 243–248.

Snyman, T., Stewart, M. J., Grove, A., & Steenkamp, V. (2005). Adulteration of South African Traditional Herbal Remedies. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, 27 (1), 86–89. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007691-200502000-00015

Summaries for Patients. (2003). Ephedra is associated with more adverse effects than other herbs. Ann Intern Med 138, I.56

Tabish, S. A. (2008). Complementary and alternative healthcare: Is it evidence-based? International Journal Health Science (Qassim) 2(1), V–IX.

Teschke, R. (2010). Kava hepatotoxicity: Pathogenetic aspects and prospective considerations. Liver International, 30 (9), 1270–1279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02308.x PMID: 20630022.

Upton, R., Romm, A. (2010). Chapter 4—Guidelines for herbal medicine use. In A. Romm, Mary L. Hardy, & S. Mills (Eds.), Botanical Medicine for Women’s Health , Churchill Livingstone, pp. 75–96, ISBN 9780443072772, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-07277-2.00004-0 . https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780443072772000040

Van Andel, T., Myren, B., & Van Onselen, S. (2012). Ghana’s herbal market. Journal of Ethno- Pharmacology., 140 (2), 368–378.

Valli, G., & Giardina, E. G. (2002). Benefits adverse effects and drug interactions of herbal therapies with cardiovascular effects. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 39 (7), 1083–1095.

Vega, L. C., Montague, E., & DeHart, T. (2011). Trust between patients and health websites: A review of the literature and derived outcomes from empirical studies. Health Technology, 1 (2–4), 71–80.

Ventola, C. L. (2010). Current issues regarding complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the United States: Part 1: The widespread Use of CAM and the need for better-Informed health care professionals to provide patient counselling. Pharmacy and Therapeutics., 35 (8), 461–468.

Wang, J., & Xiong, X. (2012). Current situation and perspectives of clinical study in integrative medicine in China. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2012, Article ID 268542, p. 11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/268542

World Health Organization. (2000). WHO General guidelines for methodologies on research and evaluation of traditional medicine . Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/66783/1/WHO_EDM_TRM_2000.1.pdf (Accessed 30 March 2022).

World Health Organization. (2019). WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1217520/retrieve (Accessed 30 March 2022).

Zhang, C. S., Tan, H. Y., Zhang, G. S., Zhang, A. L., Xue, C. C., & Xie, Y. M. (2015, November 4). Placebo Devices as Effective Control Methods in Acupuncture Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE, 10 (11), e0140825. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140825

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Pharmacology, Therapeutics and Toxicology, College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Idi-Araba, Lagos, Nigeria

Ibrahim Adekunle Oreagba

Department of Pharmacology, Therapeutics and Toxicology, College of Medicine, Lagos State University, Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria

Kazeem Adeola Oshikoya

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ibrahim Adekunle Oreagba .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Business (Entrepreneurship), Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam

Lukman Raimi

College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Oreagba, I.A., Oshikoya, K.A. (2023). Alternative Medicine and Healthcare Delivery: A Narrative Review. In: Raimi, L., Oreagba, I.A. (eds) Medical Entrepreneurship. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-6696-5_21

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-6696-5_21

Published : 07 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-19-6695-8

Online ISBN : 978-981-19-6696-5

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 23 November 2020

Potential factors that influence usage of complementary and alternative medicine worldwide: a systematic review

- Mayuree Tangkiatkumjai ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9442-970X 1 ,

- Helen Boardman 2 &

- Dawn-Marie Walker 3

BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies volume 20 , Article number: 363 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

32k Accesses

77 Citations

40 Altmetric

Metrics details

To determine similarities and differences in the reasons for using or not using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) amongst general and condition-specific populations, and amongst populations in each region of the globe.

A literature search was performed on Pubmed, ScienceDirect and EMBASE. Keywords: ‘herbal medicine’ OR ‘herbal and dietary supplement’ OR ‘complementary and alternative medicine’ AND ‘reason’ OR ‘attitude’. Quantitative or qualitative original articles in English, published between 2003 and 2018 were reviewed. Conference proceedings, pilot studies, protocols, letters, and reviews were excluded. Papers were appraised using valid tools and a ‘risk of bias’ assessment was also performed. Thematic analysis was conducted. Reasons were coded in each paper, then codes were grouped into categories. If several categories reported similar reasons, these were combined into a theme. Themes were then analysed using χ 2 tests to identify the main factors related to reasons for CAM usage.

231 publications were included. Reasons for CAM use amongst general and condition-specific populations were similar. The top three reasons for CAM use were: (1) having an expectation of benefits of CAM (84% of publications), (2) dissatisfaction with conventional medicine (37%) and (3) the perceived safety of CAM (37%). Internal health locus of control as an influencing factor was more likely to be reported in Western populations, whereas the social networks was a common factor amongst Asian populations ( p < 0.05). Affordability, easy access to CAM and tradition were significant factors amongst African populations ( p < 0.05). Negative attitudes towards CAM and satisfaction with conventional medicine (CM) were the main reasons for non-use ( p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Dissatisfaction with CM and positive attitudes toward CAM, motivate people to use CAM. In contrast, satisfaction with CM and negative attitudes towards CAM are the main reasons for non-use.

Peer Review reports

Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has become widespread in the last two decades. The prevalence of CAM use in general populations worldwide ranges from 9.8% to 76% [ 1 ]. Twelve systematic reviews report reasons for CAM use mainly in cancer populations compared to other condition-specific populations [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Five of the systematic reviews aimed to determine reasons for CAM use in either general or condition-specific populations [ 2 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. The reviews reported that the main reasons for CAM use were: (a) expected benefits and perceived safety of CAM, (b) control and participation in their therapy, and (c) alignment of socioculture, beliefs and needs. The other six reviews also reported reasons for CAM use, but this issue was not their main aim [ 3 , 4 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Their findings showed various reasons for CAM use, such as: (1) the benefits and safety of CAM, (2) availability and accessibility of CAM, (3) influence from friends, family, and the mass media, and (4) dissatisfaction with conventional medicine (CM). One systematic review from sub-Saharan Africa also reported barriers to CAM use that included: (a) the absence of conclusive scientific evidence for CAM, (b) a lack of belief in safety and efficacy of CAM, and (c) unhygienic practice in product preparation [ 9 ].

A narrative review (Jones et al., 2019) aimed to determine factors influencing CAM use in Australia and reported that cancer and other condition-specific populations shared some reasons for CAM use: (a) self-perceived ill health, (b) sense of well-being and (c) integrative treatment [ 13 ].

However these reviews do not directly compare similarities and differences in the reasons for CAM use between populations. There are also limited systematic reviews reporting reasons for not using CAM. The present review aimed to provide comprehensive understanding of factors influencing different populations to use/not use CAM.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 statement was employed in the present systematic review [ 14 ]. Research questions of this review were 1) What were the similarities and differences in reasons for using/not using CAM amongst general and condition specific populations? and 2) What were the similarities and differences in reasons for using/not using CAM amongst populations in each region?

Search strategy

The databases – PubMed: National Library of Medicine, ScienceDirect and EMBASE were searched. It is recommended that two or more databases are searched. EMBASE alone has the highest percentage recall of papers and, as a result, gains in searching resources beyond EMBASE are modest [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Keywords used were ‘herbal medicine’ OR, ‘herbal and dietary supplement’ OR, ‘complementary and alternative medicine’, AND ‘reason’ OR ‘attitude’. Free-text terms combined with Boolean operators and filters were used for searching relevant studies [ 18 ]. For example, ‘complementary and alternative medicine’ AND ‘reason’; ‘complementary and alternative medicine’ AND ‘attitude’. All permutations of these key words were performed. Herbal medicine and dietary supplements were used as keywords due to these products being extensively used worldwide, compared to other types of CAM [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. Pubmed and EMBASE were chose because they are the main sources suggested by the Cochrane centre and provide relevant studies in this field [ 26 ]. Meanwhile, the ScienceDirect database has published information relating to the social sciences A date range of January 2003 to December 2018 was set as the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2002 definition of CAM was used to underpin this research: “CAM are used to refer to a broad set of health care practices that are not part of a country’s own tradition, or not integrated into its dominant health care system” [ 27 ]. This current review began in 2019 and has reviewed relevant sources published ovevr a 15 year period from 2003 to 2018.

Selection criteria

Original articles published in English from 2003 to 2018 were reviewed. Quantitative, and qualitative studies, and mixed-methods research were included as each type of publication provided a different informational perspective and complemented each other. No limits were set regarding country of origin or type of population. This process was conducted by two independent reviewers.

Exclusion criteria

Conference proceedings, pilot studies, study protocols, letters, literature reviews or systematic reviews were excluded. The studies which did not report on factors or reasons for using, or not using, CAM were excluded. Furthermore, papers which studied some specific groups were also excluded, i.e. students, medical professionals, pregnant women, people aged less than 15 years, care givers, or specific sexual identities or ethnic groups. This exclusion was due to the premise that each group has a specific characteristic which may underpin their reasons for CAM usage, which may deviate from other populations. As the present review focused on the reasons and attitudes influencing people to use/not use CAM, efficacy trials of CAM were also excluded.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

The process of extracting data from publications was conducted by two independent reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer. The included quantitative studies were appraised using a standard tool adapted from Gan’s study, which contained 10 items and assessed a study’s internal and external validity [ 22 ]. Meanwhile, the qualitative studies were assessed by a standard tool from Jakes’ study, which evaluated agreement between research questions, methods, representation, interpretation of results, influence of researchers, evidence of ethical approve and a flow from the analysis to conclusion [ 12 ]. These tools have been used for evaluating studies in the CAM field and seem to be appropriate to assessing the methodologies of the observational and qualitative studies included in this present systematic review.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Data in the present systematic review was analysed by both qualitative and quantitative methods conducted by two independent reviewers [ 28 ]. An inductive thematic approach was performed to identify themes of reasons for use and non-use of CAM [ 28 ]. All use or non-use reasons in each publication were coded by hand, and then grouped into a category according to the reason(s). If several categories reported similar reasons, such categories were combined into one theme. The themes, therefore, emerged from this process. This process was forward and backward analysed until the themes were consistent. Then, similarities and differences of the themes between general and condition-specific populations, and between Western and Asia populations were analysed by χ 2 -tests. Tests were two-tailed and a p -value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

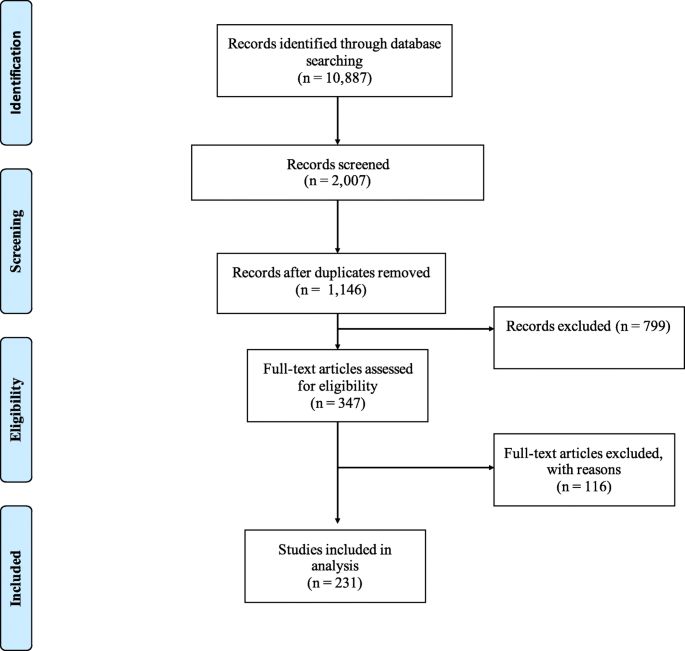

Searching via the three databases provided 10,887 publications. After excluding irrelevant publications based on their title and abstract, 2,007 publications remained, from which 861 duplicates were removed. 799 publications met the exclusion criteria and were therefore not included. From the 347 full-text articles reviewed, 116 publications were excluded due to an absence of reporting factors or reasons for CAM use, resulting in 231 publications from 51 countries being included in the analysis (Fig. 1 ).

Flowchart of study identification process

Thirty-seven out of the 231 included publications were qualitative studies (16%) mainly from the United Kingdom (UK) [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ], the United States (US) [ 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ], Australia [ 39 , 40 , 41 ] or Canada [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]; a survey or cross-sectional study were the most commonly employed quantitative methods in the included publications (80.5%). Only eight mixed method papers (3.5%) reported the reasons for CAM use [ 32 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ]. Eleven papers (4.8%) were conducted in elderly populations [ 35 , 39 , 42 , 43 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 ], and six (2.6%) in women only populations [ 29 , 38 , 39 , 59 , 60 , 61 ].

The highest number of all included publications originated in Asia (25.5%), followed by Europe (20.9%), North America (20.0%) and the Middle East (14.7%). A small number of publications from Australia were also included in the present systematic review (7.8%).

To gather information the majority of the quantitative papers utilised questionnaires which provided a list of factors or reasons for using CAM based on previous studies. The majority of the included qualitative studies utilised interviews or focus groups with open-ended questions and employed thematic or inductive analyses. Sixty-four percent of the included publications defined CAM based on the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), the World Health Organization (WHO, 7%), and the others, e.g. the Food and Drug Administration, the Dietary Supplement and Health Education Act (DSHEA), Ernst’s definition, Eisenberg’s definition, etc.

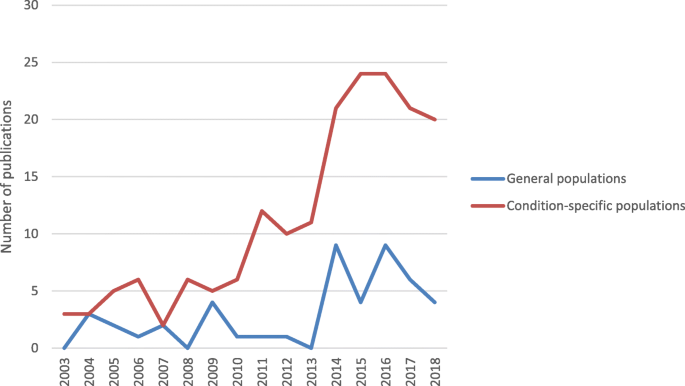

Figure 2 shows an increase in the number of publications related to reasons for CAM use amongst condition-specific populations since 2013, compared with publications involving general populations. The total number of publications dealing with CAM use amongst general and condition-specific populations in this review was 48 (21%) and 179 (77%), respectively. The number of the papers in condition-specific populations is higher than in general populations (Fig. 2 ), i.e. cancer (29.0% of publications), diabetes (5.6% of publications), cardiovascular disease and hypertension (5.2% of publications), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (3.5% of publications), inflammatory bowel disease (3% of publications), pain (3% of publications), chronic kidney disease (2.6% of publications), and depression (0.9% of publications). The majority of studies in the present review reported various types of CAM use (69%), followed by herbal medicine (18%) and traditional medicine, including traditional Chinese medicine (1%).

Trend in numbers of the publications of reasons for CAM use

The risk of bias assessment resulted in one quantitative publication being excluded due to poor internal and external validity. The included studies addressing general populations had a low bias risk (mode of a total score = 10, range 7-10), and for condition-specific populations there was a moderate risk of bias (mode of a total score = 7, range 5 – 10). The weaknesses of studies involving condition-specific populations was mainly due to a lack of reporting of their randomisation procedure (73% of the publications), how representative the sample was (64%), and non-response bias (48%). Details of the risk of bias assessment provided in a supplementary material no. 1 .

Lack of reporting the researcher’s background (69% of the publications) and the influence of reseachers on the research (60%) were the main weaknesses of the included qualitative studies in both general and condition-specific populations.

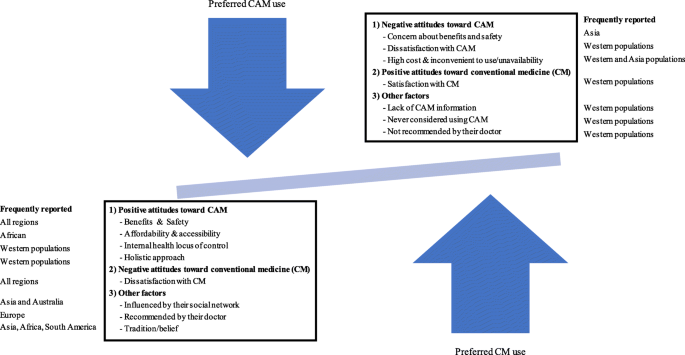

Themes of reasons for use and non-use of CAM

Both quantitative and qualitative studies reported similar reasons for CAM use. Thirty-three (14.3%) publications provided reasons for use as well as non-use of CAM. The present systematic review found three main factors related to reasons for CAM use: positive attitudes toward CAM, negative attitudes toward CM, and other factors, i.e. influence of their social network, their doctor’s recommendation, having an internal health locus of control and tradition (Fig. 3 ). Reasons for non-use of CAM were having negative attitudes toward CAM and positive attitudes toward CM.

Factors related to reasons for CAM use and non-use

Reasons for CAM use amongst general and condition-specific populations

There was no difference in reasons for CAM use between general and condition-specific populations. The top three reported reasons for CAM use in all populations were perceived benefits (84% of publications), and safety of CAM (37%), and dissatisfaction with CM (37%). The most reported expected benefits of CAM were treatment of illnesses, alleviation of symptoms, reducing side effects of CM, maintenance of well-being, or prevention of disease. People also reported that using CAM was a last resort [ 29 , 44 , 52 , 62 , 63 , 64 ]. Improving physical and emotional well-being, and quality of life were further reasons for using CAM in patients with cancer [ 50 , 63 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 ]. The cancer patients also reported using CAM to reduce side effects of CM [ 33 , 45 , 65 , 66 , 69 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 ]. Western populations in both the general and condition-specific populations were more likely to report combining CAM and CM helped them [ 33 , 54 , 74 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 ]. Likewise, condition-specific populations in some Asian and Middle East countries perceived that CAM complemented CM [ 63 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 ]. Even though CAM is more likely to be a mainstream therapy in Asian countries, the Asian condition-specific populations tend not use CAM as a substitute for CM. However, CM is substituted with CAM amongst general populations in Japan [ 90 ].

Regarding dissatisfaction with CM, being ineffective and/or causing side effects were the most frequently reported reasons in both general and condition-specific populations for their lack of satisfaction [ 29 , 36 , 40 , 54 , 81 , 87 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 ]. Some patients wanted to use CAM in order to either avoid side effects resulting from CM or to decrease the number of conventional medicines taken [ 49 , 92 , 103 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 ]. A lack of trust in CM as the reason for using CAM was reported in three publications from Asia, two from the Middle East and one from Europe [ 61 , 94 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 ]. Additionally, condition-specific populations decided to use CAM to avoid invasive care or aggressive treatment [ 80 , 111 ]; or they were disappointed with or had negative experience of conventional care and/or the staff providing it [ 41 , 80 , 86 , 97 , 103 , 105 , 117 , 118 , 119 ]. CAM users in both Asian and Western populations preferred to visit CAM practitioners because they provided fuller explanations and more time when compared with conventional health professionals [ 34 , 66 , 86 ]. Condition-specific populations in Asia and Africa often found it difficult to access CM; a circumstance which drove them to use CAM [ 97 , 120 ].

Only 8.7% of publications found that condition-specific populations viewed CAM as natural, and thus safe [ 21 , 29 , 49 , 65 , 67 , 76 , 92 , 100 , 106 , 107 , 112 , 114 , 121 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 ]. Six studies from Europe, Asia and Africa also reported ‘being curious’ as the reason for using CAM [ 92 , 97 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 ].

Other factors were influenced by CAM users’ social networks (27% of publications), having an internal health locus of control defined as preferring to control or decide choices of health treatments themselves (28%), affordability of CAM (24%), willingness to try or use CAM (including hope) (21%), conventional health professionals’ recommendation (18%), easy access to CAM (14%), belief in a holistic approach (12%), and tradition/belief (12%). Internal health locus of control and a holistic approach were more likely to reported by Western populations, as such reasons may be developed from or informed by a Western perspective [ 30 , 31 , 34 , 37 , 42 , 45 , 46 , 48 , 50 , 55 , 56 , 67 , 68 , 71 , 73 , 80 , 91 , 93 , 95 , 106 , 107 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 130 , 134 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 , 140 , 141 , 142 , 143 , 144 , 145 , 146 , 147 , 148 , 149 , 150 , 151 , 152 , 153 , 154 , 155 , 156 , 157 , 158 , 159 ].

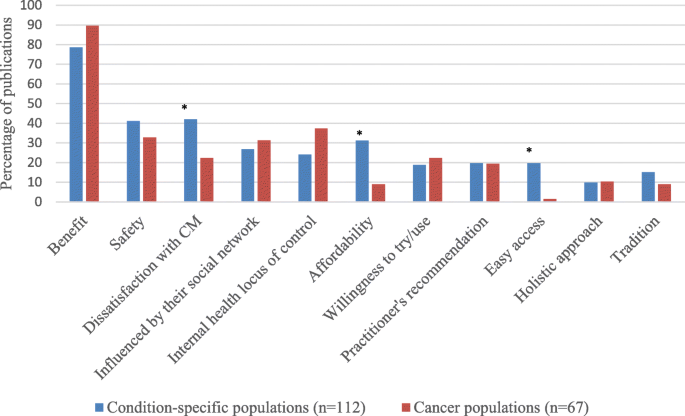

Similarities and differences in reasons for CAM use amongst patients with cancer and other chronic illnesses

The literature shows that patients with various illnesses share the main reasons for CAM use, such as perceived benefits of CAM use or dissatisfaction with CM rather than having different reasons in specific diseases [ 36 , 40 , 41 , 48 , 57 , 62 , 84 , 86 , 87 , 92 , 96 , 99 , 104 , 108 , 125 , 160 , 161 , 162 , 163 , 164 , 165 , 166 , 167 ]. However, being influenced by social media, having an internal health locus of control, or willingness to try CAM were reported more frequently by cancer patients than other members of condition-specific populations (Fig. 4 ). Meanwhile dissatisfaction with CM, affordability of CAM and easy access to CAM were more frequently reported by patients with other chronic illnesses ( p < 0.05). Patients with cancer, whilst accepting the efficacy and safety of CM, may use CAM in order to complement the efficacy of chemotherapy and/or reduce its unpleasant side effects (36% of publications in cancer populations) [ 33 , 34 , 45 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 69 , 71 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 88 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 139 , 152 ].

Comparing the reasons for CAM use amongst cancer patients and patients with other chronic illnesses. * Statistical significant at p < 0.05

Reasons for CAM use in each region

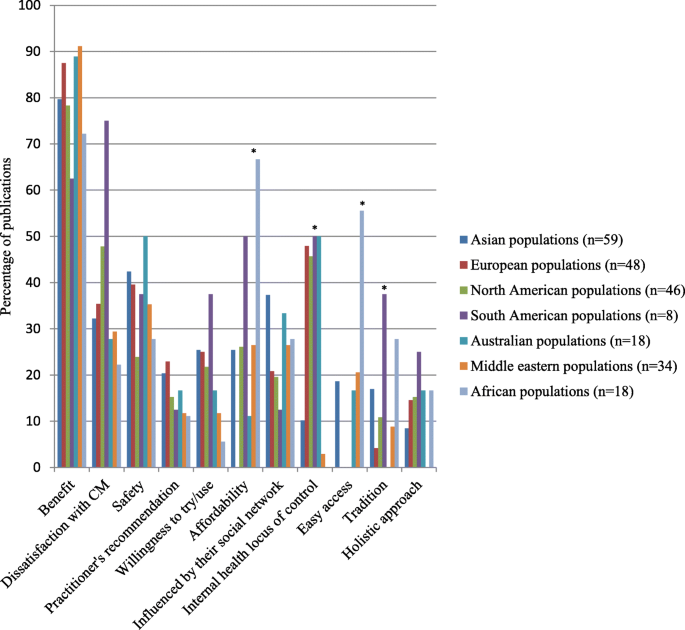

There was no global difference in the reported reasons for using CAM, namely the benefits of CAM, dissatisfaction with CM, and safety of CAM, see Fig. 5 . However, the number of publications in Europe (35% of publication), North America (48%) and South America (75%) that reported dissatisfaction with CM as the reason for using CAM was higher than in other populations. The benefits (89% of publications) and safety of CAM (50%) were reported as of the main reasons for CAM use in Australian populations.

Comparison of the reasons for CAM use worldwide. * Statistical significant at p < 0.05

An internal health locus control, affordability and easy access of CAM, as well as tradition/belief were significantly different in each region ( p < 0.05). Internal health locus control influenced people in Australia (50% of publications), South America (50%), and Europe (48%). Additionally, tradition significantly influenced CAM use in South America (38% of publications), Africa (28%) and Asia (17%), compared with other regions. A high proportion of publications in Asian (37%) and Australian populations (33%) reported that social networks influenced them to use CAM, compared with other regions. African populations had the highest proportion of reported affordability of CAM (67%) and easy access (56%) as reasons for CAM use, whilst no report of these reasons was found in European populations. European populations (23% of publications) are more likely to report conventional health professionals’ recommendations for CAM use as their reason, compared with other regions.

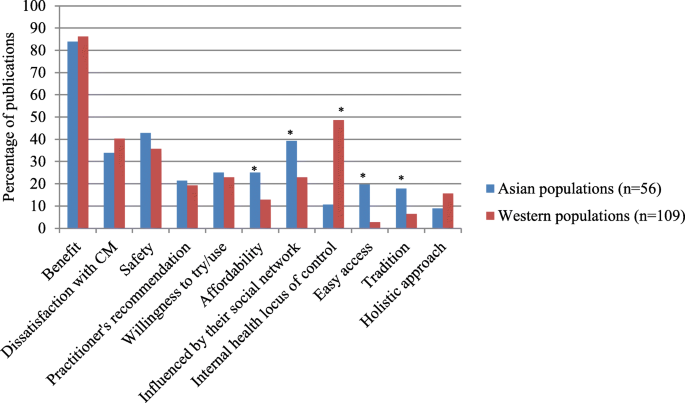

Regarding reasons for CAM use amongst Western and Asian populations, Asian populations more frequently reported using CAM due to being influenced by members of their social network, low costs of CAM, easier access to CAM and tradition than Western populations ( p < 0.05), Fig. 6 . Meanwhile, having an internal health locus of control is the main reason for CAM use in Western populations ( p < 0.05).

Comparison of the reasons for CAM use between Asian and Western populations. * Statistical significant at p < 0.05

Reasons for non-use amongst Western and Asian populations

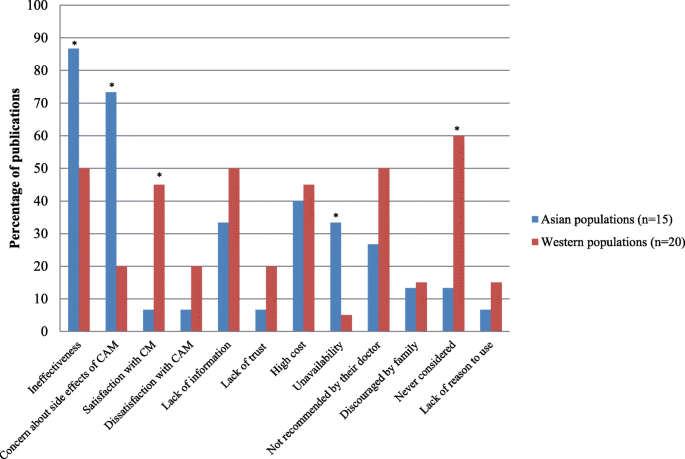

The studies of reasons for non-use are limited compared to the reasons for using CAM, so comparison of the reasons for non-use in each region cannot be made. No publications from the Middle East or South America were included in the present systematic review. Two publications from Africa and Australia were included. The majority of studies in the included publications were conducted in Asia, Europe or North America. Therefore, we compared Asian and Western populations.

Thirty papers in condition-specific populations [ 45 , 47 , 65 , 75 , 79 , 80 , 95 , 107 , 115 , 120 , 123 , 124 , 130 , 150 , 152 , 157 , 162 , 168 , 169 , 170 , 171 , 172 , 173 , 174 , 175 , 176 , 177 , 178 , 179 ], six in general populations [ 180 , 181 , 182 , 183 , 184 , 185 ], one publication involving elderly people [ 53 ] and one publication involving females [ 61 ] reported the reasons for not using CAM. Asian populations more frequently reported doubt about the efficacy of CAM or lower effectiveness of CAM compared to CM, concerns about side effects of CAM, and inconvenience or unavailability of CAM than did members of Western populations ( p < 0.05), Fig. 7 [ 47 , 75 , 79 , 120 , 170 , 172 , 174 , 175 , 176 , 177 , 179 , 180 , 181 ]. Some publications in Asian populations also reported concern about CAM reducing the efficacy of CM as a reason for non-use [ 169 , 170 ].

Reasons for non-use between Asian and Western populations. * Statistical significant at p < 0.05

Meanwhile, Western populations mainly reported satisfaction with CM (45% of publications, p < 0.05) or had never considered using CAM (60%, p < 0.05) [ 45 , 65 , 95 , 123 , 124 , 130 , 150 , 152 , 157 , 162 , 171 , 182 , 184 , 186 ]. Other reasons for the non-use of CAM were lack of reliable information about the efficacy of CAM, the high cost of CAM, and it not being recommended by conventional health professionals or the ‘patient’s’ family.

The included studies in the present systematic review can be seen to represent CAM use worldwide as they were mainly from Asia, Europe, North America, Middle East, and Australia. Recently, researchers in Asia have become interested in this field as several CAMs are embedded in their culture and society. Publications from this region has been rising since 2008; however, readers should be aware that the present systematic review included a small number of eligible publications from Australia and South America. Although a high number of publications originated in Australia, they tended to study specific populations, e.g. middle-aged women, and other topics, rather than reasons for CAM use. Researchers may less likely to investigate reasons for CAM use in South America, compared to other regions. Therefore, the findings in the present systematic review may be less likely to be generalisable in Australian and South American populations.

The present systematic review included a high number of publications amongst cancer, diabetic, cardiovascular disease, and HIV populations. It would therefore seem that illnesses, such as these which cannot be satisfactorily treated by CM, or when CM has significant unpleasant side-effects, drive some patients to seek CAM. Cancer populations have been studied regarding reasons for CAM use more than other condition-specific populations. There are six systematic reviews of the reasons for CAM use in patients with cancer [ 2 , 3 , 5 , 8 , 187 , 188 ].

As expected, three main factors related to reasons for CAM use in the present systematic review were positive attitudes toward CAM, negative attitudes toward CM and other factors, i.e. the influence of their social network, their doctor’s recommendation, having an internal health locus of control and tradition. The top three reported reasons for CAM use were perceived benefits and safety of CAM, and dissatisfaction with CM. These findings are consistent with previous systematic reviews [ 3 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. These reasons are similar in both general and condition-specific populations, and in populations from different global regions, as cited frequently above. Although the present systematic review included a limited number of publications from Australia, benefits and safety of CAM were reported as the main reasons for CAM use in Australian populations. These findings agree with a previous systematic review in Australia [ 6 ].

Despite limited scientific evidence for the benefits of CAM [ 189 ], the ‘expected benefits’ of CAM was the most frequently reported reason for CAM use. This finding is not surprising as people tend to seek CAM as a way of meeting their needs or filling a gap left by conventional medicine. The included publications amongst the cancer population are more likely to report CAM use for reducing the negative and often unpleasant side effects of CM. This finding is consistent with systematic reviews of CAM users with prostate or advanced cancer [ 3 , 4 ]. Additionally, the cancer population seems to accept the efficacy and side effects of CM, and therefore uses CAM to complement CM.

Previously, people believed that CAM is natural and safe [ 190 ]. This idea may have led many patients with chronic illnesses on using CAM instead of CM. However, the present systematic review indicates that a small number of the included publications amongst condition-specific populations reported that CAM is safe as a reason for CAM use. Therefore, CAM as natural therapy is not the main reason for CAM use; a point which may be linked to the high number of reported adverse events from using CAM [ 191 , 192 , 193 ]. Patients therefore should use CAM with caution or under supervision from conventional or CAM practitioners.

Regarding other factors related to CAM use in each region, nearly half of the included publications reported that internal health locus control influenced people in Australia, South America, and Europe. However, this reason may have been reported less by Asian, Middle Eastern and African people, as they may not explain their reasons in such terms. Tradition also significantly influenced CAM use in South America, Africa and Asia, compared with other global regions. This orientation may be because CAM, for example, herbal medicine, is embedded in such regions and therefore aligns with their populations’ socio-culture values. Social networks influenced Asian and Australian populations to use CAM, compared with other regions, as they may have a close-knot family or community structure.

Affordability of CAM, together with easy access, are likely to be the main reasons for CAM use amongst African populations. The high cost of, and poor accessibility to, CM appears to influence people to use CAM in Africa [ 57 , 58 , 97 , 164 , 183 , 194 , 195 , 196 , 197 , 198 , 199 , 200 , 201 ]. Meanwhile, no report of these reasons was found in European populations. CAM may not be cheap and easy to access in Europe, compared with CM as users have to personally pay for CAM and it can be difficult to access [ 19 ]. Moreover, European populations are more likely to report conventional health professionals’ recommendations for CAM use as their reason for choosing that option, compared with other global regions. This option may be because health care is readily available in most European countries; so when they have a health problem, they visit their general practitioner.

There are limited publications reporting reasons for non-use of CAM in each region. Further studies relating to this issue are required, particularly in populations from Africa, the Middle East and South America. The present systematic review found that Asian populations are more likely to question the efficacy and safety of CAM, and to be concerned about potentially harmful interactions between herbal medicines and CM. These findings imply that Asian populations seem to understand the limitations of CAM, the efficacy and safety of CAM, and are aware of herb-drug interactions.

The findings confirm that Western populations do not use CAM if they are satisfied with the efficacy and safety of CM. This outcome may be because they can easily access CM, and CAM is less likely to be considered as an option for chronic illnesses in Western countries. However, if they were to become disappointed with the CM/staff, they may decide to use CAM. This possibility is consistent with the systematic review of patients with cancer, which reported that the patients who were satisfied with CM did not use CAM [ 3 ]. Lack of reliable information about the efficacy of CAM, as a barrier to CAM use reported in the present systematic review, is consistent with the findings from a previous systematic review [ 9 ].

Limitations of this review

Although this review only selected a small number of key words, and only three search engines in order to search the literature the findings returned 43% duplicate publications. Further reviews should search using a wide range of CAM types as keywords, e.g. yoga, acupuncture, relaxation, etc., in order to confirm the findings from the present review. There was a small number of publications addressing the reasons for CAM use in South America (n = 8); thus the findings from that continent should be interpreted with caution. This review included only publications in English; as a result the findings did not represent publications in other languages. Regarding the results from the search strategy used in this review, only 5% of the papers were excluded due to being non-English. This outcome is unlikely to have any significant impact on the findings of the present review, as most of the studies were conducted in Europe, from where a high number of publications in English were identified for inclusion in this review.

Results of publications in condition-specific populations representing a national population should also be interpreted with caution due to only 36% of these studies being designed to represent the patient population. The present systematic review found poor external validity of the included studies amongst condition-specific populations, therefore future studies should be aware of this issue.

Impact of the findings for conventional health professionals

Expected benefits of CAM are the main reason for CAM use despite a lack of clinical trials. To promote the rational use of CAM, health care providers should be ready to provide such information to their patients and conventional medicine guidelines should report reliable information about CAM, and be easily available to, health care providers. The findings in the present review have confirmed that being disappointed with CM or associated professional providers, particularly in Western populations, is more likely to influence condition-specific populations to use CAM. To prevent patients from using CAM inappropriately, health care providers should spend more time clearly explaining treatment options, the likely treatment outcomes and potential negative effects of CAM, including herb-drug interactions.

Having an internal health locus of control seems to be a main reason for CAM use in Western populations. This finding implies that patients prefer deciding a therapy by and for themselves. To decrease inappropriate use of CAM, conventional health care providers should offer sufficient health information to their patients, as well as holding a discussion with a patient, before deciding upon a health therapy.

A person’s social network is more likely to influence their decision making regarding CAM in Asian populations. Therefore, health care providers should educate not only patients about how to properly use CAM, but also their friends and family members.

It is clear that the main reasons for CAM use in all populations are a positive attitude toward CAM, that is the perceived benefit and safety of CAM, and a negative attitude toward CM, a dissatisfaction with CM. Having an internal health locus of control is a more frequently reported reason for CAM use in Western populations, whilst being influenced by social networks is a common reason for its adoption amongst Asian populations. Affordability, easy access to CAM and tradition are the most common reasons amongst African populations. Negative attitudes towards CAM and satisfaction with CM are more likely to be the reason for non-use. Conventional health professionals should acknowledge that people may turn to CAM in order to serve their needs. Therefore, health care providers should regularly ask their patients about their use of CAM before that providers prescribes any conventional medicines, in order to prevent undesirable adverse effects or CAM-drug interactions. Further studies are required to investigate reasons for CAM use in South America and reasons for non-use in all global regions, in order to provide more conclusive evidence in this field.

Availability of data and materials

The included publications in this systematic review were assessed their risk of bias in order to evaluate the quality of publications. This information provided in its supplementary information file. The other datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Conventional Medicine

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Revews and Meta-Analyses

The United Kingdom

The United States

Harris PE, Cooper KL, Relton C, Thomas KJ. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: a systematic review and update. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(10):924–39.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Weeks L, Balneaves LG, Paterson C, Verhoef M. Decision-making about complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients: integrative literature review. Open Med. 2014;8(2):e54–66.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Truant TL, Porcino AJ, Ross BC, Wong ME, Hilario CT. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in advanced cancer: a systematic review. J Support Oncol. 2013;11(3):105–13.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bishop FL, Rea A, Lewith H, Chan YK, Saville J, Prescott P. Elm Ev, Lewith GT: complementary medicine use by men with prostate cancer: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14(1):1–13.

Verhoef MJ, Balneaves LG, Boon HS, Vroegindewey A. Reasons for and characteristics associated with complementary and alternative medicine use among adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005;4(4):274–86.

Reid R, Steel A, Wardle J, Trubody A, Adams J. Complementary medicine use by the Australian population: a critical mixed studies systematic review of utilisation, perceptions and factors associated with use. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):176.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Franzel B, Schwiegershausen M, Heusser P, Berger B. Individualised medicine from the perspectives of patients using complementary therapies: a meta-ethnography approach. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:124.

Bishop FL, Yardley L, Lewith GT. A systematic review of beliefs involved in the use of complementary and alternative medicine. J Health Psychol. 2007;12(6):851–67.

James PB, Wardle J, Steel A, Adams J. Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(5):e000895.

Qureshi NA, Khalil AA, Alsanad SM. Spiritual and religious healing practices: some reflections from Saudi National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Riyadh. J Relig Health. 2018.

Yang L, Sibbritt D, Adams J. A critical review of complementary and alternative medicine use among people with arthritis: a focus upon prevalence, cost, user profiles, motivation, decision-making, perceived benefits and communication. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(3):337–51.

Jakes D, Kirk R, Muir L. A qualitative systematic review of patients’ experiences of acupuncture. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(9):663–71.

Jones E, Nissen L, McCarthy A, Steadman K, Windsor C. Exploring the use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1534735419854134.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J, Franco OH. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):245.

Halladay CW, Trikalinos TA, Schmid IT, Schmid CH, Dahabreh IJ. Using data sources beyond PubMed has a modest impact on the results of systematic reviews of therapeutic interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(9):1076–84.

Suarez-Almazor ME, Belseck E, Homik J, Dorgan M, Ramos-Remus C. Identifying clinical trials in the medical literature with electronic databases: MEDLINE alone is not enough. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21(5):476–87.

Keene MR, Heslop IM, Sabesan SS, Glass BD. Complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;35:33–47.

CAMbrella – A pan-European research network for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) [ https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/92501/reporting/en ].

Ock SM, Choi JY, Cha YS, Lee J, Chun MS, Huh CH, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in a general population in South Korea: results from a national survey in 2006. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24(1):1–6.

Singh V, Raidoo DM, Harries CS. The prevalence, patterns of usage and people's attitude towards complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among the Indian community in Chatsworth, South Africa. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004;4:3.

Gan WC, Smith L, Luca EJ, Harnett JE. The prevalence and characteristics of complementary medicine use by Australian and American adults living with gastrointestinal disorders: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2018;41:52–60.

Jatau AI, Aung MM, Kamauzaman TH, Chedi BA, Sha'aban A, Rahman AF. Use and toxicity of complementary and alternative medicines among patients visiting emergency department: systematic review. J Intercult Ethnopharmacol. 2016;5(2):191–7.

The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States [ https://nccih.nih.gov/research/statistics/2007/camsurvey_fs1.htm ].

Posadzki P, Watson LK, Alotaibi A, Ernst E. Prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by patients/consumers in the UK: systematic review of surveys. Clin Med (Lond). 2013;13(2):126–31.

Article Google Scholar

Lefebvre C, Glanville J, Briscoe S, Littlewood A, Marshall C, Metzendorf M-I, et al. Searching for and selecting studies. Cochrane Handbook Syst Rev Interv. 2019:67–107.

World Health Organization. WHO traditional medicine strategy 2002-2005. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

Google Scholar

Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J. An introduction to systematic reviews. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications Inc.; 2017.

Vickers KA, Jolly KB, Greenfield SM. Herbal medicine: women's views, knowledge and interaction with doctors: a qualitative study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:40.

Soundy A, Lee RT, Kingstone T, Singh S, Shah PR, Edwards S, et al. Experiences of healing therapy in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:106.

Little CV. Simply because it works better: exploring motives for the use of medical herbalism in contemporary U. K, health care. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17(5-6):300–8.

Holmes MM, Bishop FL, Calman L. “I just googled and read everything”: exploring breast cancer survivors’ use of the internet to find information on complementary medicine. Complement Ther Med. 2017;33:78–84.

MacArtney JI. Balancing exercises: Subjectivised narratives of balance in cancer self-health. Health (London). 2016;20(4):329–45.

de Valois B, Asprey A, Young T. “The monkey on your shoulder”: a qualitative study of lymphoedema patients’ attitudes to and experiences of acupuncture and moxibustion. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:4298420.

Oberg EB, Thomas MS, McCarty M, Berg J, Burlingham B, Bradley R. Older adults’ perspectives on naturopathic medicine’s impact on healthy aging. Explore (NY). 2014;10(1):34–43.

Hwang JP, Roundtree AK, Suarez-Almazor ME. Attitudes toward hepatitis B virus among Vietnamese, Chinese and Korean Americans in the Houston area, Texa. J Community Health. 2012;37(5):1091–100.

Eaves ER, Sherman KJ, Ritenbaugh C, Hsu C, Nichter M, Turner JA, et al. A qualitative study of changes in expectations over time among patients with chronic low back pain seeking four CAM therapies. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:12.

Kabel A. Fighting for wellness: strategies of mid-to-older women living with cancer. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2015;30(1):107–17.

McLaughlin D, Lui CW, Adams J. Complementary and alternative medicine use among older Australian women - a qualitative analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:34.

McIntyre E, Saliba AJ, Moran CC. Herbal medicine use in adults who experience anxiety: a qualitative exploration. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2015;10:29275.

Brijnath B, Antoniades J, Adams J. Investigating patient perspectives on medical returns and buying medicines online in two communities in Melbourne, Australia: results from a qualitative study. Patient. 2015;8(2):229–38.

Fries CJ. Older adults’ use of complementary and alternative medical therapies to resist biomedicalization of aging. J Aging Stud. 2014;28:1–10.

Williamson AT, Fletcher PC, Dawson KA. Complementary and alternative medicine: use in an older population. J Gerontol Nurs. 2003;29(5):20–8.

Read SC, Carrier ME, Whitley R, Gold I, Tulandi T, Zelkowitz P. Complementary and alternative medicine use in infertility: cultural and religious influences in a multicultural Canadian setting. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(9):686–92.

Fox P, Butler M, Coughlan B, Murray M, Boland N, Hanan T, et al. Using a mixed methods research design to investigate complementary alternative medicine (CAM) use among women with breast cancer in Ireland. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(4):490–7.

Niemi M, Stahle G. The use of ayurvedic medicine in the context of health promotion--a mixed methods case study of an ayurvedic Centre in Sweden. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:62.

Tangkiatkumjai M, Boardman H, Praditpornsilpa K, Walker DM. Reasons why Thai patients with chronic kidney disease use or do not use herbal and dietary supplements. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:473.

Skovgaard L. Use and users of complementary and alternative medicine among people with multiple sclerosis in Denmark. Dan Med J. 2016;63(1):B5159.

PubMed Google Scholar

Hendershot KA, Dixon M, Kono SA, Shin DM, Pentz RD. Patients’ perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine in head and neck cancer: a qualitative, pilot study with clinical implications. Complement Therapies Clin Pract. 2014;20(4):213–8.

Scarton LA, Del Fiol G, Oakley-Girvan I, Gibson B, Logan R, Workman TE. Understanding cancer survivors’ information needs and information-seeking behaviors for complementary and alternative medicine from short- to long-term survival: a mixed-methods study. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(1):87–97.

Mulkins AL, McKenzie E, Balneaves LG, Salamonsen A, Verhoef MJ. From the conventional to the alternative: exploring patients’ pathways of cancer treatment and care. J Complement Integr Med. 2016;13(1):51–64.

Levine MAH, Xu S, Gaebel K, Brazier N, Bedard M, Brazil K, et al. Self-reported use of natural health products: a cross-sectional telephone survey in older Ontarians. J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7(6):383–92.

Cheung CK, Wyman JF, Halcon LL. Use of complementary and alternative therapies in community-dwelling older adults. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(9):997–1006.

Bruno JJ, Ellis JJ. Herbal use among US elderly: 2002 National Health Interview Survey. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(4):643–8.

Johnson PJ, Jou J, Rhee TG, Rockwood TH, Upchurch DM. Complementary health approaches for health and wellness in midlife and older US adults. Maturitas. 2016;89:36–42.

Murthy V, Sibbritt D, Broom A, Kirby E, Frawley J, Refshauge KM, et al. Back pain sufferers’ attitudes toward consultations with CAM practitioners and self- prescribed CAM products: a study of a nationally representative sample of 1310 Australian women aged 60-65 years. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23(6):782–8.

Ayele AA, Tegegn HG, Haile KT, Belachew SA, Mersha AG, Erku DA. Complementary and alternative medicine use among elderly patients living with chronic diseases in a teaching hospital in Ethiopia. Complement Ther Med. 2017;35:115–9.

Bayuo J. Experiences with out-patient hospital service utilisation among older persons in the Asante Akyem North District- Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):652.