World History Edu

- Africa / Renowned Writers

Wole Soyinka: Biography, Political Activism, Major Plays, Nobel Prize, & Achievements

by World History Edu · May 3, 2021

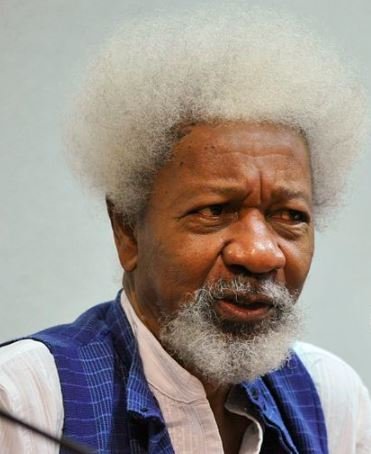

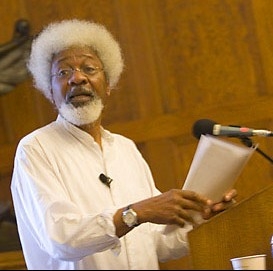

Wole Soyinka — Image courtesy — from the Nobel Foundation archive

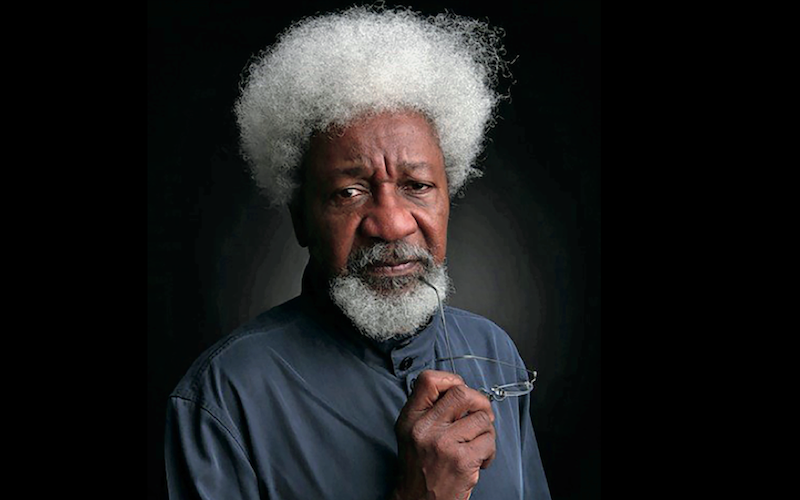

In recent decades, very good playwrights have emerged from the African continent, but nowhere do they reach the excellence of Nigerian playwright and poet Wole Soyinka.

Most known for winning the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986, Wole Soyinka has written critically acclaimed plays for both theatre and radio. He thus became the first sub-Saharan African to win a Nobel Prize.

Drawing heavily from Yoruba people’s myths, rites and cultural patterns, Soyinka, a Distinguished Scholar in Residence at Duke University, has attained incredible feats to the point where he is now considered one of the finest poetical playwrights of all time.

Wole Soyinka: Quick Facts

Born: Akinwande Ouwole “Wole” Soyinka

Birthday: July 13, 1934

Place of birth : Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria (formerly Nigeria Protectorate)

Parents: Grace Eniola Soyinka and Samuel Ayodele Soyinka

Siblings: Folashade (died at age one), Kayode, Omofolabo “Folabo”, Yeside, Femi, and Atinuke “Tinu”.

Education: Abeokuta Grammar School, Government College in Ibadan (1946-1952), University College Ibadan (1952-1954); University of Leeds

Spouses: Married three times and divorce twice: Barbara Dixon (married in 1958), Olaide Idowu (married in 1963), Folake Doherty (1989-)

Influenced by : Irish writer J.M. Synge, British literary scholar Molly Maureen Mahood

Most famous for : Works that help to advance understanding and the exchange of knowledge of different cultures and peoples

Notable awards and honors: Nobel Prize in Literature (1986), Academy of Achievement Golden Plate Award (2009), Europe Theatre Prize in the “Special Prize” category (2017)

Who is Wole Soyinka?

Wole Soyinka is the son of Samuel Ayodele Soyinka and Grace Eniola. Both his parents grew up in strong Anglican values. His father for example was an Anglican minister and a headmaster of Anglican school in Abeokuta. His mother, a shop owner, was a political activist in Abeokuta.

His family belongs to the Yoruba people, one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria. As a result of his family’s Anglican background as well as the prevailing Yoruba religious tradition around him, he benefited tremendously from the merging of those two religious beliefs. As a matter of fact, many of his works were inspired by the culture and traditions of the Yoruba people.

Growing up, Soyinka attended a primary school in Abeokuta before studying at Government College in Ibadan, Nigeria. He then proceeded to the University of Ibadan (1952-1954) and then the University of Leeds in England (1957), where he studied drama. While at Leeds, he was tutored by the famous literary critic Wilson Knight.

While in the United Kingdom, he worked for some time as a dramturgist at the Royal Court Theater, London. Once back in Nigeria, Soyinka followed his passion and studied African drama before going on to teach drama and literature at the University of Lagos.

He also had teaching spells at his alma mater the University of Ibadan, and later Obafemi Awolowo University (formerly the University of Ife).

Like his famous aunt-in-law, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (the mother of Afro-Beat king Fela Kuti ), Soyinka was very active in Nigeria’s fight to gain independence from Great Britain.

Since 1975 Soyinka has been the professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Ibadan. He has on numerous occasions served as a visiting professor in universities in England and the U.S., including Yale, Cambridge, and Sheffield.

In November 1994 he fled his home country Nigeria (through Benin) after then-military ruler General Sani Abacha accused him of treasonous crimes. Soyinka made his way to the U.S., where he lived until Nigeria was returned to civilian rule following the death of Gen. Abacha in 1998.

In October 1994 Soyinka was appointed the UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for the Promotion of African culture and human rights, freedom of expression, media and communication

Imprisonment during the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970)

Frustrated by the extent of cult of personality and rampant government corruption in his country, he began to firm statements critical of the Nigerian government, especially the January 1966 military coup

Beginning around 1967, Soyinka had secret talks with the Ibo community in a bid to avert a civil war from breaking out in Nigeria. He wrote a passionate article, appealing to both sides to exercise restraint. However, his good intentions were misread by the Nigeria government (headed by General Yakubu Gowon) who described him as a traitor.

Soyinka was subsequently imprisoned in 1967 on the charge of conspiring with the leaders of Biafra rebels. He remained locked up (in solitary confinement in some cases) for close to two years before his release in 1969.

Fight against oppressive governments and dictators

Soyinka does not mince words when it comes to rejecting the numerous military dictatorships that have blighted many African countries for decades. For example, he was very vocal in criticizing the brutal dictatorships of General Idi Amin of Uganda (1971-1979), Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (1987-2017), and Nigeria’s General Sani Abacha’s (1993-1998). The latter dictator, in a farce trial, sentenced Soyinka in absentia to death on the charge of treason against the state.

As a result of the frequent suppression of dissent in Nigeria by various military juntas of the past, Soyinka was forced to spend a bulk part of his adult life living in exile, particularly in countries such as the U.S. and the UK.

He has also relentlessly called on his Nigerian government to end the endemic corruption and abuse of powers by people placed in positions of trust.

Nobel Prize in Literature (1986)

In 1986, Soyinka became the first African to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. His works were deemed by the Swedish Academy in Stockholm, Sweden, as being “full of life and urgency”.

In his Nobel lecture , titled “This Past Must Address Its Present”, on December 8, 1986, he praised the invaluable contribution anti-apartheid fighter Nelson Mandela in ending the politics of racial segregation in not just South Africa, but across the world.

Two years after his 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature, he received the Agip Prize for Literature.

Major plays and essays

Broadcast in July 1954 by the Nigerian Broadcasting Service, Soyinka’s “Keffi’s Birthday Treat” was a short radio play that he wrote while studying in the U.K.

During his stay in London, he also wrote plays such as The Lion and the Jewel (1959) and The Swamp Dwellers (1958) . The latter play was a philosophical play with a touch of comedy, highlighting how Nigerians could blend development and tradition.

Other famous plays by Wole Soyinka

Drawing heavily from Yoruba people’s myths, rites and cultural patterns, Soyinka has attained incredible feats to the point where he is now considered one of the finest poetical playwrights of all time.

The following are some of his famous plays:

The Invention (1957) – Soyinka’s first play to be produced at the Royal Court Theatre, London

A Dance of the Forest (performed 1960, published in 1963)

The Strong Breed (performed 1966, published in 1963)

The Detainee (1964) – a radio play for the BBC in London

The Road (1965) – premiered in London at the Commonwealth Arts Festival in September, 1965

Kongi’s Harvest (performed 1965, published 1967)

Madmen and Specialists (performed in 1970, published in 1971)

Death and the King’s Horseman (performed in 1976, published in 1975)

Opera Wonyosi (performed in 1977, published in 1981)

A Play of Giants (1984)

Requiem for a Futurologist (1985)

Famous novels by Wole Soyinka

Some examples of Wole Soyinka famous novels are The Interpreters (1964) and Season of Anomy (1973). The latter delves into his thoughts during his time behind bars as political prisoner.

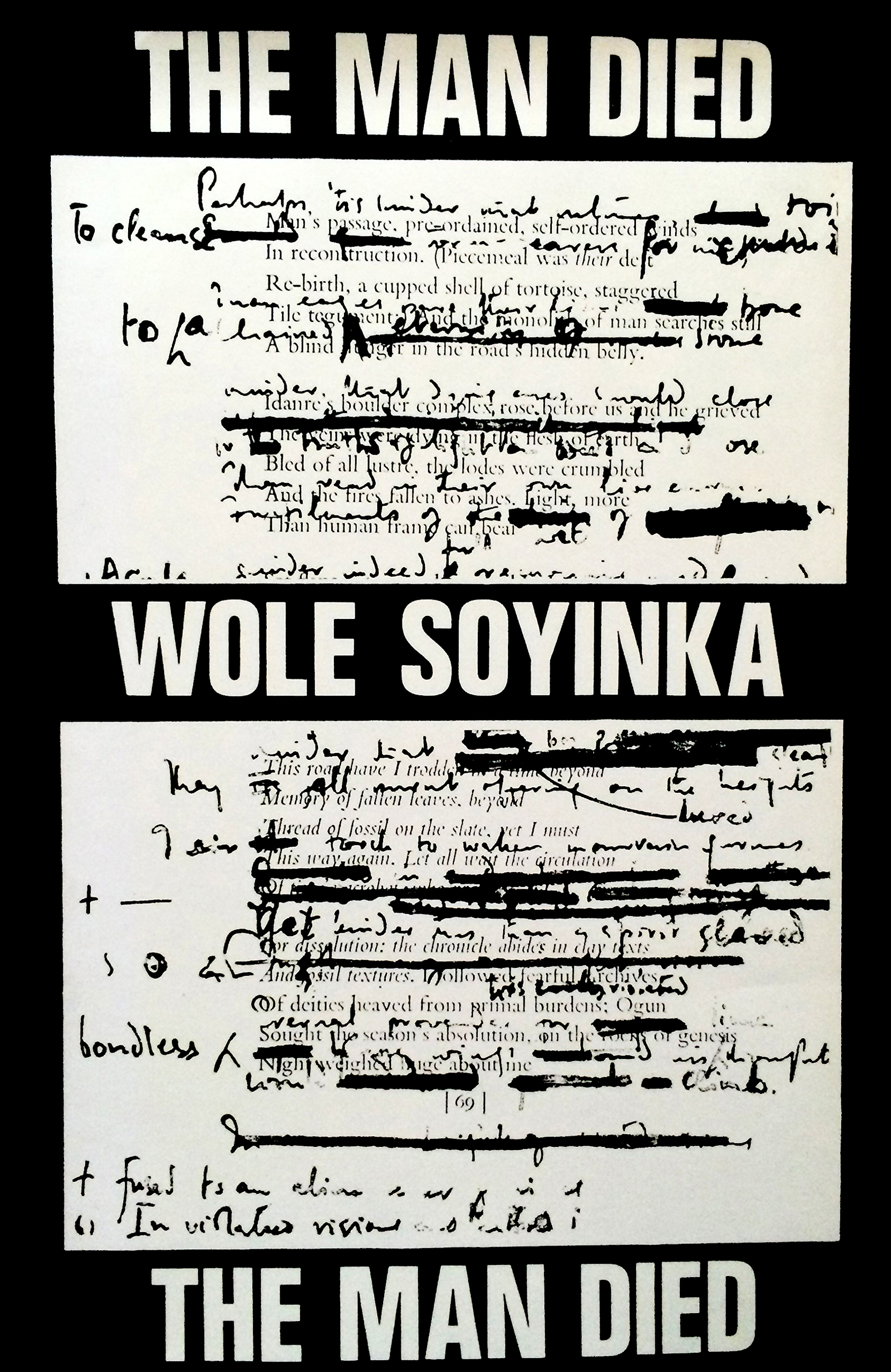

Wole Soyinka — A line from Soyinka’s 1960 essay for the Horn

More Wole Soyinka Facts

- In an interview in 2007, he stated that he although he attended church regularly and sang in the choir while growing up in Abeokuta, he went on to gravitate towards agnosticism in his adult life, which was then followed by “outright atheistic convictions”.

- Soyinka’s mother – Grace Eniola Soyinka – was a member of the Ransome-Kuti family. She was also the niece-in-law to Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, the mother of Afro-Beat king Fela Kuti.

- Some notable first cousins (once removed) are Fela Kuti, Dr. Beko Ransome-Kuti, and politician Olikoye Ransome-Kuti. As a result, his second cousins are Femi Kuti Seun Kuti, and Yeni Kuti.

- Soyinka is a big admirer of Yoruba mythology, particularly the orisha (god) Ogun, the god of iron and war.

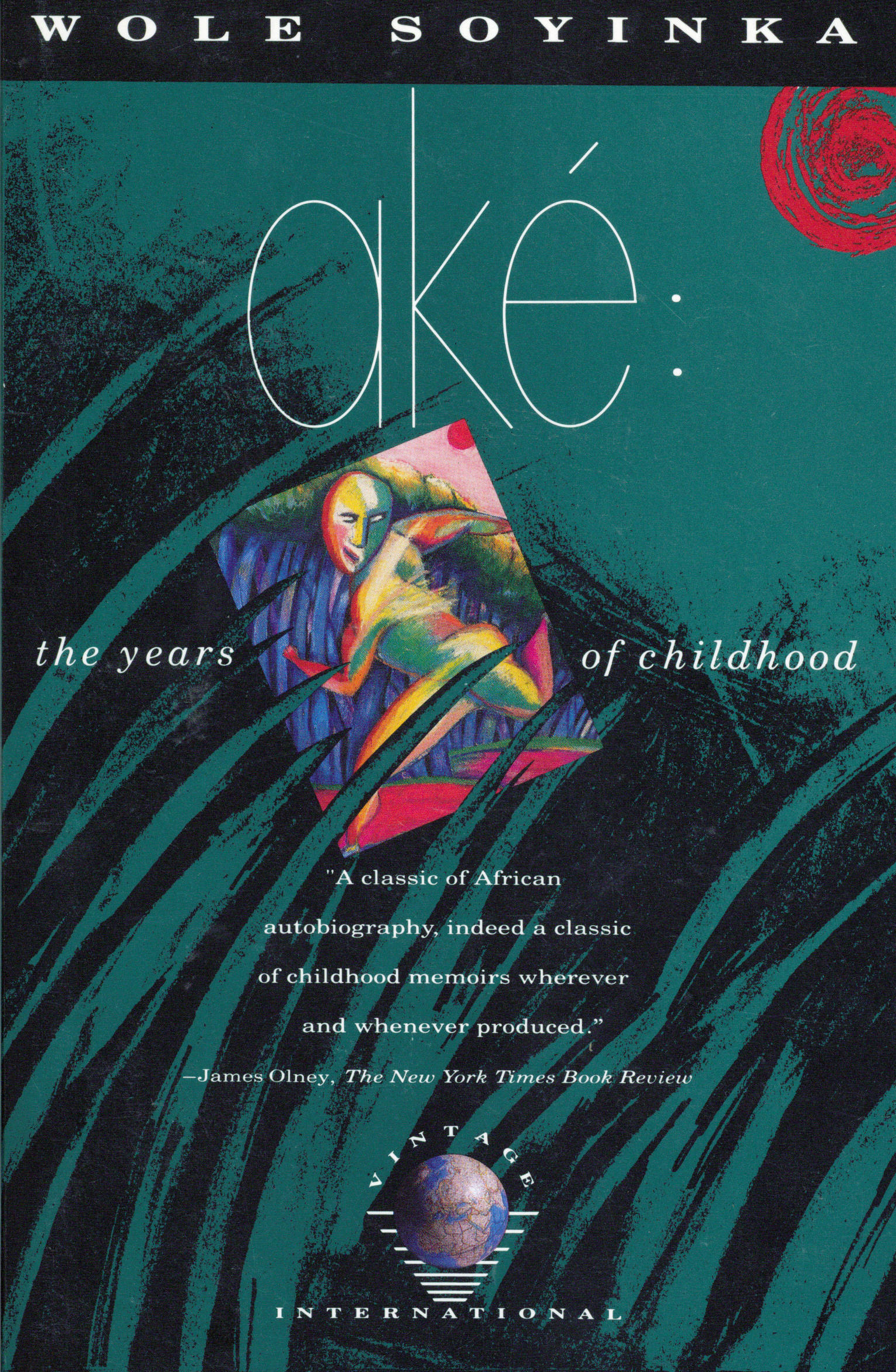

- Some of his most famous autobiographies are The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972), which was banned by a Nigerian court in 1984, and Aké: The Years of Childhood (1981), which won the 1983 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award.

- Soyinka’s first essay “Towards a True Theater” was published in December 1962. He would go on to write several others, including Culture in Transition (1963), Myth, Literature, and the African World (1976), and The Credo of Being and Nothingness (1991)

- In 1960, Wole Soyinka founded a theatre group called The 1960 Masks. Four years later, in 1964, he founded the Orisun Theatre Company, producing many great plays and acting in a number of them.

- His 1963 play A Dance of the Forest (performed 1960, published 1963) was a brilliant work that exposed the flaws of the elites of Nigerian society. It was selected as the official play for the independence celebration on October 1, 1960.

- He released his first feature length film – Culture in Transition – in 1963.

- Soyinka briefly lived in Accra, Ghana, where he served as the editor of the literary magazine Transition. The magazine was very critical of numerous African dictators of that era, including Idi Amin, Uganda’s dictator of the 1970s.

Tags: Abeokuta-Nigeria African Writers Nigeria Nobel Prize in Literature Playwrights Poets Wole Soyinka

You may also like...

Shaka Zulu: History, Military Tactics & Facts

May 22, 2021

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf: 10 Major Accomplishments

July 15, 2020

10 Mightiest African Empires of All Time and their Achievements

June 9, 2021

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Next story Major Facts about Fela Kuti (1938-1997)

- Previous story Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

Nakba Day: Origin Story & Significance to the Palestinians

Who were the Catholic priests that were legally married before becoming pope?

Apologizing for Alan Turing’s Prosecution

Why did NATO get involved in the Kosovo War?

Most Influential Scientists of the 20th Century

Greatest African Leaders of all Time

Queen Elizabeth II: 10 Major Achievements

Donald Trump’s Educational Background

Donald Trump: 10 Most Significant Achievements

8 Most Important Achievements of John F. Kennedy

Odin in Norse Mythology: Origin Story, Meaning and Symbols

Ragnar Lothbrok – History, Facts & Legendary Achievements

9 Great Achievements of Queen Victoria

12 Most Influential Presidents of the United States

Most Ruthless African Dictators of All Time

Kwame Nkrumah: History, Major Facts & 10 Memorable Achievements

Greek God Hermes: Myths, Powers and Early Portrayals

8 Major Achievements of Rosa Parks

Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

10 Most Famous Pharaohs of Egypt

How did Captain James Cook die?

The Exact Relationship between Elizabeth II and Elizabeth I

Nile River: Location, Importance & Major Facts

Sobek in Egyptian Mythology: Origin Story, Family, Powers, & Symbols

How and when was Morse Code Invented?

- Adolf Hitler Alexander the Great American Civil War Ancient Egyptian gods Ancient Egyptian religion Apollo Athena Athens Black history Carthage China Civil Rights Movement Cold War Constantine the Great Constantinople Egypt England France Germany Hera Horus India Isis John Adams Julius Caesar Loki Medieval History Military Generals Military History Nobel Peace Prize Odin Osiris Pan-Africanism Queen Elizabeth I Ra Religion Set (Seth) Soviet Union Thor Timeline Turkey Women’s History World War I World War II Zeus

- Member Interviews

- Science & Exploration

- Public Service

- Achiever Universe

- Summit Overview

- About The Academy

- Academy Patrons

- Delegate Alumni

- Directors & Our Team

- Golden Plate Awards Council

- Golden Plate Awardees

- Preparation

- Perseverance

- The American Dream

- Recommended Books

- Find My Role Model

All achievers

Wole soyinka, nobel prize in literature.

Listen to this achiever on What It Takes

What It Takes is an audio podcast produced by the American Academy of Achievement featuring intimate, revealing conversations with influential leaders in the diverse fields of endeavor: public service, science and exploration, sports, technology, business, arts and humanities, and justice.

Writing became a therapy. I was reconstructing my own existence. It was also an act of defiance.

Akonwande Oluwole “Wole” Soyinka was born in Abeokuta in Western Nigeria. At the time, Nigeria was a Dominion of the British Empire. British religious, political and educational institutions co-existed with the traditional civil and religious authorities of the indigenous peoples, including Soyinka’s ethnic group, the Yorùbá people, who predominate in Western Nigeria. As a child, Soyinka lived in an Anglican Christian enclave known as the Parsonage. Soyinka’s mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, was a devout Anglican; in his memoirs, Wole Soyinka calls his mother “Wild Christian.” His father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka, was headmaster of the parsonage primary school, St. Peter’s. Known as “S.A.,” Wole Soyinka calls him “Essay” in his memoirs. Although the Soyinka family had deep ties to the Anglican Church, they enjoyed close relations with Muslim neighbors, and through his extended family — particularly his father’s relations — Wole Soyinka gained an early acquaintance with the indigenous spiritual traditions of the Yorùbá people. Even among practicing Christians, belief in ghosts and spirits was common. The young Wole Soyinka enjoyed participating in Anglican services and singing in the church choir, but he also formed an early identification with Ogun, the Yorùbá deity associated with war, iron, roads and poetry.

Soyinka’s mother, a shopkeeper, joined a protest movement, led by her sister Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, against the traditional ruler, the Alake of Abeokuta, who ruled with the support of the British colonial authorities. When the Alake levied oppressive taxes against the shopkeepers, Mrs. Ransome-Kuti, Mrs. Soyinka, and their followers refused to pay, and the Alake was forced to abdicate.

Thanks to his father, young Wole Soyinka enjoyed access to books, not only the Bible and English literature but to classical Greek tragedies such as the Medea of Euripides, which had a profound effect on his imagination. A precocious reader, he soon sensed a link between the Yorùbá folklore of his neighbors and the Greek mythology underlying so much of western literature.

He moved quickly from St. Peter’s Primary School to the Abeokuta Grammar School and won a scholarship to the colony’s premier secondary school, the Government College in Ibadan. At this boarding school, he continued to distinguish himself in his studies, writing stories and acting in school plays, the beginning of his lifelong preoccupation with the practical aspects of theatrical performance.

After graduation at age 16 from the Government College, Soyinka deferred immediate admission to university life and moved to the colonial capital, Lagos, to work in an uncle’s pharmacy for two years before entering university. During this period of personal independence, he began writing plays for local radio. In 1950, he entered the University at Ibadan. Two years later, won a scholarship to the University of Leeds in England, and left Africa for the first time.

In England, he joined a close-knit community of West African students. The petty racism they encountered in Britain seemed less important than the reports they read from South Africa of black Africans being subjected to legally enforced racial discrimination in their own country by the white-led apartheid government. Along with his fellow African students, Soyinka imagined a pan-African movement to liberate South Africa. He went so far as to enlist in the British program of student military education, in hopes that he could use this training in a future campaign against the apartheid regime in South Africa. He dropped out of the program during the Suez Crisis, when it appeared that students might be called up to serve in Egypt. As Britain prepared to leave Nigeria, students like Soyinka were excused from further military service.

After graduating from the University of Leeds, Wole Soyinka continued to study for a master’s degree while writing plays drawing on his Yorùbá heritage. His first major works, The Swamp Dwellers and The Lion and the Jewel , date from this period. In 1958, The Lion and the Jewel was accepted for production by the Royal Court Theatre in London. Beginning in the late 1950s, the Royal Court was the major venue for serious new drama in Britain. Soyinka interrupted his graduate studies to join the theater’s literary staff. From this post, he was able to watch the rehearsal and development process of new plays at a time when the British theater was entering a period of renewed vitality. His own next major work was The Trials of Brother Jero , expressing his skepticism about the self-styled elite of black Nigerians who were preparing to take power from the British colonial regime.

In 1960, Soyinka received a Rockefeller Foundation grant to research traditional performance practices in Africa. Nigeria was poised to become independent from Britain, and Soyinka’s play A Dance of the Forest, another satire of the colonial elite, was chosen to be performed during the independence festivities. Soyinka joined the English faculty at the University of Ibadan. He also formed a theater company, 1960 Masks, to produce topical plays, employing traditional performance techniques to dramatize the many issues arising from Nigerian independence. His writings, including his 1964 novel, The Interpreters , were bringing him fame outside his own country, but he faced increasing difficulties with censorship inside Nigeria. Independence from Britain had not brought about the open democratic society Soyinka and others had hoped for. In negotiating the independence of the country, Britain had overestimated the population of the northern region, dominated by Hausa-Fulani people of Muslim faith, and given them greater representation in the national parliament, at the expense of the predominantly Christian peoples of the southern regions: the Yorùbá in the West and the Igbo in the East.

In Western Nigeria, the results of a 1964 regional election were set aside so that a candidate favored by the central government could claim victory. With some friends, Soyinka forced his way into the local radio station and substituted a tape of his own for the recorded message prepared by the fraudulent victor of the election. This escapade caused his arrest and detention for two months, but international publicity led to his acquittal. Following his release, Soyinka was appointed to the English Department of Lagos University, and completed the comedy Kongi’s Harvest , which would be produced throughout the English-speaking world. Soyinka had become one of the best-known writers in Africa, but political developments would soon thrust him into a more difficult role. The discovery of oil in the Southeast in 1965 further heightened ethnic and regional tensions in Nigeria. A 1966 military coup led by Igbo officers was followed by a counter-coup, which installed the young army officer Yakubu Gowon as head of state. Massacres of Igbo living in the North sent more than a million refugees fleeing south, and many Igbo began to call for secession from Nigeria. Hoping to avoid further bloodshed, Soyinka traveled in secret to meet with the secessionist General Ojukwu and urged a peaceful resolution. When Ojukwu and the Eastern forces declared an independent Republic of Biafra, Soyinka contacted General Obasanjo of the Western forces to urge a negotiated settlement of the conflict, but Obasanjo sided with the national government, and a full-scale civil war ensued. Soyinka’s friend, the poet Christopher Okigbo, joined the Biafran forces and was killed in action.

Soyinka was accused of collaborating with the Biafrans and went into hiding. Captured by Nigerian federal troops, he was imprisoned for the rest of the war. From his prison cell, he wrote a letter asserting his innocence and protesting his unlawful detention. When the letter appeared in the foreign press, he was placed in solitary confinement for 22 months. Despite being denied access to pen and paper, Soyinka managed to improvise writing materials and continued to smuggle his writings to the outside world. A volume of verse, Idanre and Other Poems , composed before the war, was published to international acclaim during his imprisonment. By the end of 1969, the war was virtually over. Gowon and the Nigerian federal army had defeated the Biafran insurgency, an amnesty was declared, and Soyinka was released. Unable to return immediately to his old life, he repaired to a friend’s farm in the South of France. While recuperating, he wrote an adaptation of the classical Greek tragedy The Bacchae by Euripides. Across the millennia, the story of a state destroyed by a sudden eruption of senseless violence had acquired a special resonance for Soyinka. Another volume of verse, Poems from Prison , also known as A Shuttle in the Crypt , was published in London.

Soyinka returned to Nigeria to head the Department of Theater Arts at the University of Ibadan. The 1970s were a productive decade for Wole Soyinka. He oversaw stage and film productions of his play Kongi’s Harvest and wrote one of his most compelling satirical plays, Madmen and Specialists . His prison memoir, The Man Died , was published in 1972, followed by a novel, The Season of Anomy . He traveled to France and the United States for productions of his plays. When political tensions resurfaced, unresolved by the civil war, Soyinka resigned his university post and went to live in Europe, lecturing at Cambridge and other universities. Oxford University Press published his Collected Plays in 1974. One of his greatest works appeared the following year, the poetic tragedy Death and the King’s Horseman . After a number of years in Europe, Soyinka settled for a time in Accra, Ghana, where he edited the literary journal Transition . His column in the magazine became a forum for his continued commentary on African politics, in particular for his denunciation of dictatorships such as that of Idi Amin in Uganda.

In 1975, General Gowon was deposed, and Soyinka felt confident enough to return to Nigeria, where he became Professor of Comparative Literature and head of the Department of Dramatic Arts at the University of Ife. He published a new poetry collection, Ogun Abibiman , and a collection of essays, Myth, Literature and the African World , a comparative study of the roles of mythology and spirituality in the literary cultures of Africa and Europe. His continuing interest in international drama was reflected in a new work, inspired by John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera and Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera . Soyinka called his musical allegory of crime and political corruption Opera Wonyosi . He created a new theatrical troupe, the Guerilla Unit, to perform improvised plays on topical themes.

At the turn of the decade, Wole Soyinka’s creativity was expanding in all directions. In 1981, he published the first of several volumes of autobiography, Aké: The Years of Childhood . In the early 1980s, he wrote two of his best-known plays, Requiem for a Futurologist and A Play of Giants , satirizing the new dictators of Africa. In 1984, he also directed the film Blues for a Prodigal . For years, Soyinka had written songs. In the 1980s, Nigerian music, including that of Soyinka’s cousin, the flamboyant bandleader Fela Ransome-Kuti, was capturing the attention of listeners around the world. In 1984, Soyinka released an album of his own music entitled I Love My Country , with an assembly of musicians he called The Unlimited Liability Company.

Soyinka also played a prominent role in Nigerian civil society. As a faculty member at the University of Ife, he led a campaign for road safety, organizing a civilian traffic authority to reduce the shocking rate of traffic fatalities on the public highways. His program became a model of traffic safety for other states in Nigeria, but events soon brought him into conflict with the national authorities. The elected government of President Shehu Shagari, which Soyinka and others regarded as corrupt and incompetent, was overthrown by the military, and General Muhammadu Buhari became Head of State. In an ominous sign, Soyinka’s prison memoir, A Man Died, was banned from publication.

Despite troubles at home, Soyinka’s reputation in the outside world had never been greater. In 1986, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, the first African author to be so honored. The Swedish Academy cited the “sparkling vitality” and “moral stature” of his work and praised him as one “who in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence.” When Soyinka received his award from the King of Sweden in the ceremony in Stockholm, he took the opportunity to focus the world’s attention on the continuing injustice of white rule in South Africa. Rather than dwelling on his own work, or the difficulties of his own country, he dedicated his prize to the imprisoned South African freedom fighter Nelson Mandela. His next book of verse was called Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems . He followed this with two more plays, From Zia with Love and The Beatification of Area Boy , along with a second collection of essays, Art, Dialogue and Outrage . He continued his autobiography with Isara: A Voyage Around Essay , centering on his memories of his father S.A. “Essay” Soyinka, and Ibadan, The Penkelemes Years .

Meanwhile, Soyinka continued his criticism of the military dictatorship in Nigeria. In 1994, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) named Wole Soyinka a Goodwill Ambassador for the promotion of African culture, human rights and freedom of expression. Less than a month later, a new military dictator, General Sani Abacha, suspended nearly all civil liberties. Soyinka escaped through Benin and fled to the United States. Soyinka judged Abacha to be the worst of the dictators who had imposed themselves on Nigeria since independence. He was particularly outraged at Abacha’s execution of the author Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was hanged in 1995 after a trial condemned by the outside world. In 1996, Soyinka published The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Memoir of the Nigerian Crisis . Predictably, the work was banned in Nigeria, and in 1997, the Abacha government formally charged Wole Soyinka with treason. General Abacha died the following year, and the treason charges were dropped by his successors.

Since 1994, Wole Soyinka has resided primarily in the United States. He has taught at a number of American universities, including Emory University in Atlanta, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and Loyola Marymount in Los Angeles. Since moving to the United States, he has written another play, King Baabu , a volume of verse, Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known , and his latest book of memoirs, You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006).

Although Wole Soyinka has always been reticent about discussing his family life, in this volume he makes a particularly touching dedication to his “stoically resigned” children, and to his wife Adefolake, for enduring many years of hardship and dislocation.

Although presidential elections were held in Nigeria in 2007, Soyinka denounced them as illegitimate due to ballot fraud and widespread violence on election day. Wole Soyinka continues to write and remains an uncompromising critic of corruption and oppression wherever he finds them.

The poet and playwright Wole Soyinka is a towering figure in world literature. He has won international acclaim for his verse, as well as for novels such as The Interpreters . His work in the theater ranges from the early comedy The Lion and the Jewel to the poetic tragedy Death and the King’s Horseman .

Born in Nigeria, he returned from graduate studies in England just as his country attained its independence from Britain. Many of his plays, including Kongi’s Harvest and Madmen and Specialists , are bitter satires on the dictatorships of post-colonial Africa. In the late ’60s, his opposition to a repressive regime in his own country led to his imprisonment in solitary confinement for nearly two years, an experience he reflects on in the memoir The Man Died and the verse collection A Shuttle in the Crypt .

His works in all genres deploy a rich poetic language, steeped in European mythology and the Yorùbá spiritual traditions of West Africa, interests he fused in his masterful study Myth, Literature and the African World . In 1986, he became the first African to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Apart from your literary career, you have played a very active political role in Nigeria, beginning many years ago. During the Western regional crisis of 1965, you took to the airwaves to denounce the falsification of election results. Could you tell us how that came about?

Wole Soyinka: Those elections were very violent and the people resisted. This was the Western Region at the time. I was then teaching at the University of Ibadan. Violent, and the incumbent government used its power of incumbency in the region, in alliance with the power of the center. It was a federal structure. In spite of that, they could not rig the election successfully. And so what they did was just start altering the results. And even that proved exceedingly difficult for them. Finally the premier of the region decided to just forget the whole thing and announce his victory on radio. And I happened, you know, by very fortunate coincidence, I learned that this was going to become a fait accompli . And since he had the support of the federal government, something drastic had to be done. And so with some assistance, some of my usual collaborators, I managed to stop the broadcast, substitute my — I pre-recorded my own statement. So I went to the studio and I took the premier’s tape off and substituted my own and went away. And so I was tried — very, very nasty charge. I was charged with armed robbery, because apparently this event was supposed to have taken place with the aid of a gun, and so — very cunning people, coming to frame a charge of armed robbery, for a tape! Costs under a pound or whatever, and I substituted one, anyway — so it wasn’t — and I left that one. So where was the robbery?

Anyway, I was tried and acquitted, thank goodness. Then some years passed. Of course the seeds of what came later were already being laid and planted, from that rigging of the elections in the West, and in the rest of the country, as a matter of fact. So a military coup took place in 1966, in January. There were massacres, especially against the Igbos, because the first coup, the leaders were mostly Igbo, and so reprisal claims took place and the drums of war began to sound very, very loud. The East Igbos, who felt they had been really violated — because they were hunted down all over the place, not just in the North — they decided to secede.

My friend Christopher Okigbo was Igbo, of course. I knew him from the writers and artists community in Ibadan. He was a founding member of the Mbari writers and artists club. When I was detained for that “un-robbery” episode, he used to come and visit me in my place of detention. I was not actually formally detained. I was just not granted bail, that’s all. So he used to come to visit me at the police station where I was held and we’d read his poetry together. Or more accurately, he would read his poetry. He loved reading his own poems. He wanted you to hear exactly how it sounded, because it was a very aural, musical kind of poetry. He was a musician also, by the way, so that wasn’t surprising. So we became quite close.

When I realized that war really was going to happen, I tried to — and he (Christopher Okigbo) had left, like the other Igbo that fled to the East, where they were more secure. Chinua Achebe was in the East. We had other writers like Gabriel Okara in the East, and I felt maybe by linking up and resurrecting that tight community we might be able to do something to prevent that war, and so I traveled. By then the firing had started, the early skirmishes had begun. And I traveled by road to the East. I was promptly arrested as a suspected enemy by the Biafrans whom I had come to see, but of course, some time after, the police realized who I was and I was released. And who had come into my police station? He didn’t know I was there. It was Christopher Okigbo, coming from the war front, coming for more equipment. And so we were reunited for the last time. He went back to the front. So the leader of the secessionist enclave, Ojukwu, we spoke, and then when I came back I was detained for having traveled to the East. I was accused of all kinds of things, including trying to buy jet fighters for the — I don’t know why people like to cook, you know, fantasies, around one’s individual existence.

Why did you take on this role of intermediary between the Biafrans and the West?

Wole Soyinka: I belong to the West, the Yorùbá part of the federation. And in a war, when a war is being fought, it is being fought on behalf of people. And this war committed me, as a Nigerian, it committed me, and I felt that war was wrong and I refused to accept that, to be committed in that way. The Biafrans had been violated. They had been massacred. It was more than one massacre, it was like a wave of massacres. And they were being hunted everywhere. In other words, the conduct of the federal side, at least that portion to which I belong, indicated — said, in plain language, even though it was not articulated as such, “You, the Igbo, are no longer part of the federation.” There was no way, nothing was done to make them feel secure, at least not enough was done to make them feel secure in the rest of the nation. And then, after they had seceded, which I considered, by the way, a tactical mistake — not a political crime, not a moral crime, no, no, no, no, no. It was a tactical error. But then, to go after them, to declare war against them on this banal basis of unity above anything else! Unity of what? I mean, who committed the act of disuniting the nation in the first place? Those who made the Igbo feel they were not part of the full entity. So for me it was an unjust war of which I could not be a part. And if I’d not gone to the East, I would have gone into exile, because I would refuse to be part of that entity which waged war against a people who had been so dehumanized. So in effect, it was for my own peace of mind, to try and do everything possible to make sure the war did not take place.

When you returned to the West, you were detained, but never officially charged. Was this because of an open letter you had published in the Daily Times of Nigeria? What was your intent in writing that letter?

Wole Soyinka: First of all, the letter was published before I went to the East.

There was supposed to be a delegation going from the federal side, a delegation of citizens, you know, high-placed citizens, traditional rulers and so on. I wanted to make sure that when they went over to the East, they didn’t go mouthing pious, meaningless sentiment. They should understand that they were going to visit a wronged people, and that they should take the kind of message there that would make them come back. Well, as I expected, it was a futile visitation. The Igbo by that stage didn’t trust anyone, and in any case they could not, they had nothing concrete to take over to the other side. And so I followed up my letter by visiting there, and trying to get Chinua, Christopher, the group I knew, and also talk to Ojukwu, whom I’ve known — the head of the Biafran enclave — whom I’ve known. We were both students around the same time, even though he was somewhat older than myself. And when I came back, I brought back certain messages and delivered those messages on return.

I should add that when I went there, we had formed what we called the “Third Force.” Since the cause of the federal side, in our view, was not just, and since the Igbo had committed a tactical error in deciding on secession, we thought there should be a third force, a neutral force, which would put on the table various concrete proposals, in effect neutralizing the positions of both sides. We could present these proposals to both sides, and to the international community, which might finally succeed in bringing them to some kind of agreement.

You’ve made a distinction between your first arrest, in the mid-’60s, and your second arrest. If corruption, a rigged election, was the issue in the first case, what was really the issue when you were imprisoned the second time?

Wole Soyinka: Power is involved in this, you know. The tendency for sections of any community to dominate the rest seems to be part and parcel of society, historically. Nothing extraordinary, in my view, happened about what went on in Nigeria. It wasn’t really corruption that led to the first coup, even though this was one of the allegations. It had to do with a sense of injustice, of a political lie which had been implanted by the British before they departed. So it was the contest for power, as much as for control of resources. Because power is an element in itself which one should never underestimate. To dominate others seems to be kind of an animal part of the human make-up which we haven’t quite evolved out of. So corruption, yes, was involved, but it wasn’t really the central issue in those early days.

Days after your incarceration, your friend Christopher Okigbo was killed in the civil war. Did you hear of his death while you were in prison? Were you able to get news?

Wole Soyinka: I was in solitary confinement for quite a while, but after a while, even prison has its chinks which one is able to study and explore. So occasionally, after the really hermetic isolation of a couple of months, I was able to start formulating links with the outside world.

You smuggled a letter out of prison in 1967. How did it change your treatment in prison?

Wole Soyinka: First of all, I was held in a maximum security prison in Lagos. After I smuggled out that statement, the government panicked and decided to move me to Kaduna and place me in complete solitary confinement. I was shocked. It was one of the most bitter moments, bitterest moments of my incarceration, to find the Minister of Information calling an international press conference and reading what was supposed to be my confession. It’s one of the most horrible things that can happen to anybody in prison, that you feel, “What else? What is going to come next? What are they going to say next? What are they speaking in my name?” Reading —not to be accusing me, I mean, that’s okay — but actually saying, “I have here his confessional statement,” and every bit of it — except the trip to Biafra — a complete fabrication. But after I got to Kaduna, I stayed completely quiet for some time. Didn’t even attempt to reach the outside world. Just made sure they thought I was a complete model prisoner, totally resigned to being in isolation. And I began to probe the chinks and managed to start getting things outside. Even sent some poems for publication to my publisher outside, which was scribbled on toilet paper with ink I’d manufactured and so on.

You wrote about your prison experience in a memoir, The Man Died . Did you actually begin work on that book while you were in prison?

Wole Soyinka: I began writing, scribbling notes, you know, in prison. But it wasn’t actually published until after I’d come out. Writing became a therapy. First of all, it meant I was reconstructing my own existence. It was also an act of defiance. I wasn’t supposed to write. I wasn’t supposed to have paper, pen, anything, any reading material whatsoever. So this became an exercise in self-preservation, keeping up my spirits. It also, you had to occupy very long hours of the day, you know, not speaking to anyone. And I even — it wasn’t just writing. I evolved all kinds of mental exercises, even went back to those subjects which I said I hated in school, in particular mathematics. I started to try and recover my mathematical formulae by trial and error, and created problems for myself which I solved. You know, anything to keep the mind alive. As I said, it’s an exercise in self-preservation. Writing was just part of it.

- 42 photos

Wole Soyinka

My literary journey.

By Book Buzz Foundation

"The culture of any society represents for me the authentic spiritual precipitates of any society or community." - Wole Soyinka

Wole Soyinka is a renowned Nigerian playwright, poet, essayist, and critic. He was born on July 13, 1934, in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Soyinka is often regarded as one of the foremost literary figures in Africa and is known for his diverse body of work that addresses political, social, and cultural issues. The 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to him. He is the first African recipient of the prize.

Wole Soyinka Antequities (2020) by Wole Soyinka Book Buzz Foundation

On the art of fiction writing

I do not identify as a fiction writer by nature. My novels emerged more or less by chance. While I have always enjoyed writing short stories, the idea of writing a novel never crossed my mind. I vividly recall the inception of my first novel, marking my initial foray into the world of fiction. The entire conception of 'The Interpreters' occurred during my time with my acting company, a period when I was actively engaged in play-writing.

On the importance of language

My deep fascination with language, regardless of its form, has been the driving force behind my literary pursuits. I have always studied language alongside literature. My fascination with language can actually be traced back to my encounter with D. O. Fágúnwà, a pioneering Nigerian author who wrote novels in the Yorùbá language. As a child, his works sparked an appreciation for language that extended beyond my native tongue, leading me to recognize parallels in the literary traditions of other cultures. I often incorporate Yorùbá phrases into my work, finding joy in the challenge of translating these expressions into English. Sometimes, when a direct translation proves elusive, I simply include the Yorùbá phrase with a brief explanation in a footnote.

The culture of any society is a reflection of its spiritual essence. There is a great deal of healing to be done, dating back to the very origins of slavery, even before we consider the imperialist adventure, the misadventure of colonization, and the ongoing repercussions of neocolonialism, such as the persistent inequitable treatment of African societies and the Black race in general, even in global forums. I use my work to shed light on and address these fundamental and crucial issues.

On the books that have influenced me

As a child, I devoured the works of D. O. Fágúnwà, a prolific Yoruba author. In fact, after completing my studies in England, I set out on an ambitious project to translate all of Fágúnwà's works into English. However, after translating the first novel, I had an epiphany. I realized that if I continued to focus solely on translating Fágúnwà's works, I might never develop my own unique voice as a writer. Fortunately, I was able to step back from this project after some years and revisit it with a fresh perspective. Each time I delve into Fágúnwà's writings, I am enriched by his mastery of language and his ability to weave captivating stories. His works continue to serve as a source of inspiration.

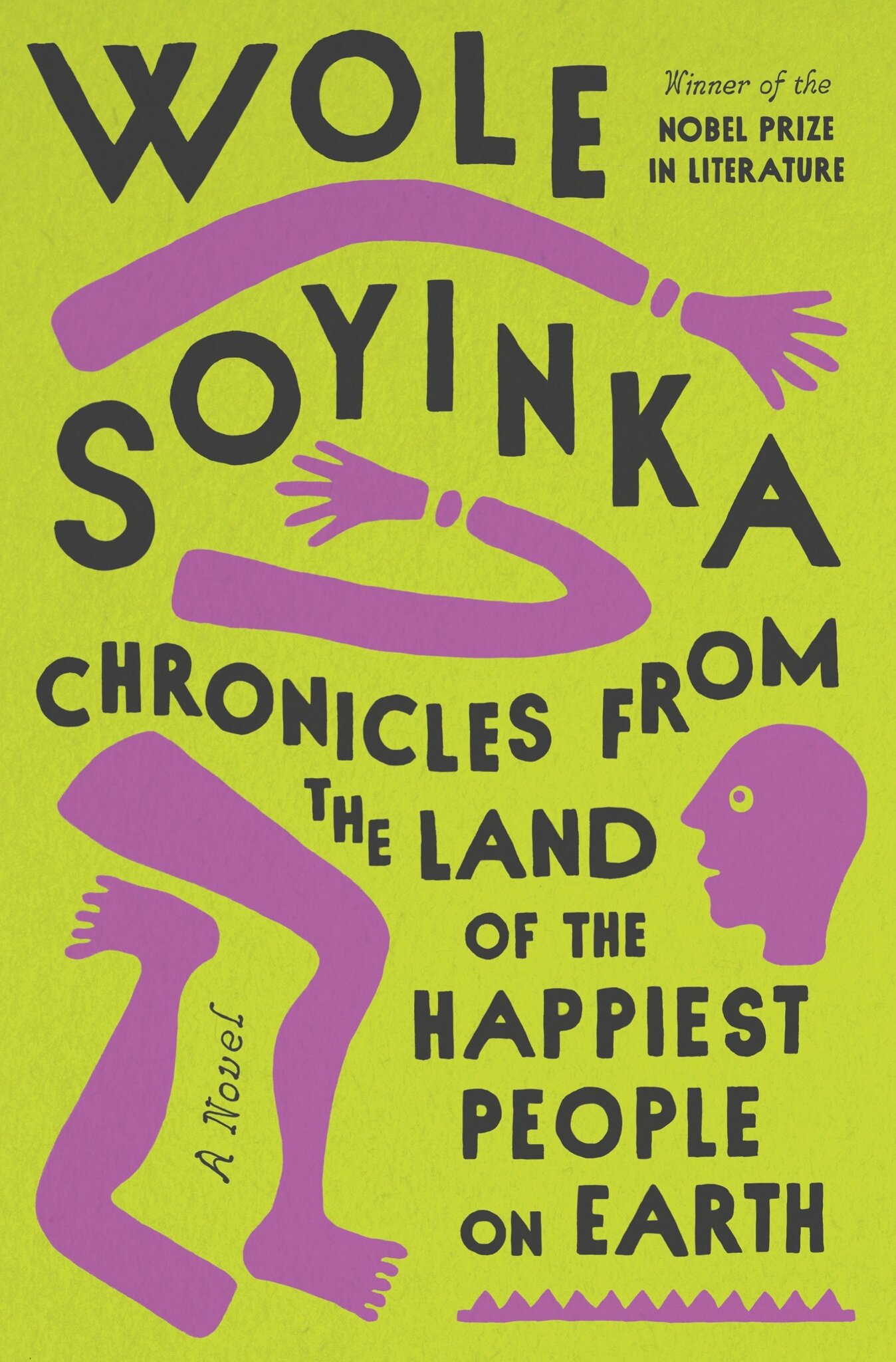

On writing for the theater

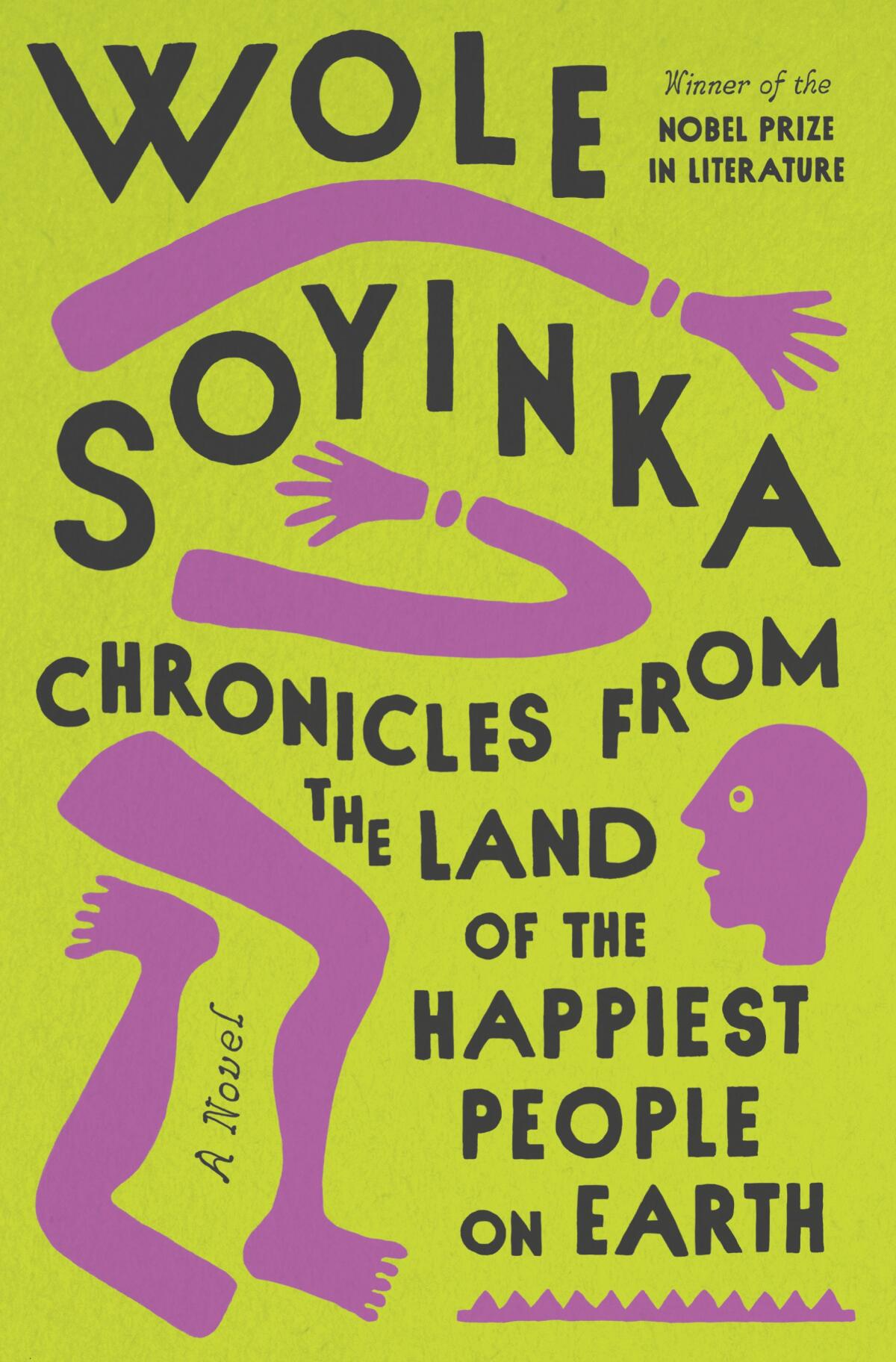

Following the publication of The Interpreters , I embarked on the creation of Season of Anomy . It was an introspective exploration of my generation, examining our role and impact on a rapidly evolving society. The Interpreters marked the beginning of my literary investigation into the character and impact of my generation. The Season of Anomy delved into the realm of mythology, while Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth took longer to manifest than initially anticipated. Despite my ventures into novel writing, I still consider myself primarily a playwright, finding greater resonance and comfort in the world of theater.

Introducing Ake Arts and Book Festival

Book buzz foundation, the gems of african literature, daughters of pen: discover african women writers, weaving african magical worlds of wonders and adventure, ink trailblazers: male writers shaping african literature, africanfuturism and africanjujuism: discover the wonders of other worlds, véronique tadjo, ama ata aidoo (1942 - 2023), wana udobang: take me back, esu: the misunderstood god of yoruba religion.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka on a Lifetime of Art and Activism

Aysegül sert talks to the nigerian writer in paris.

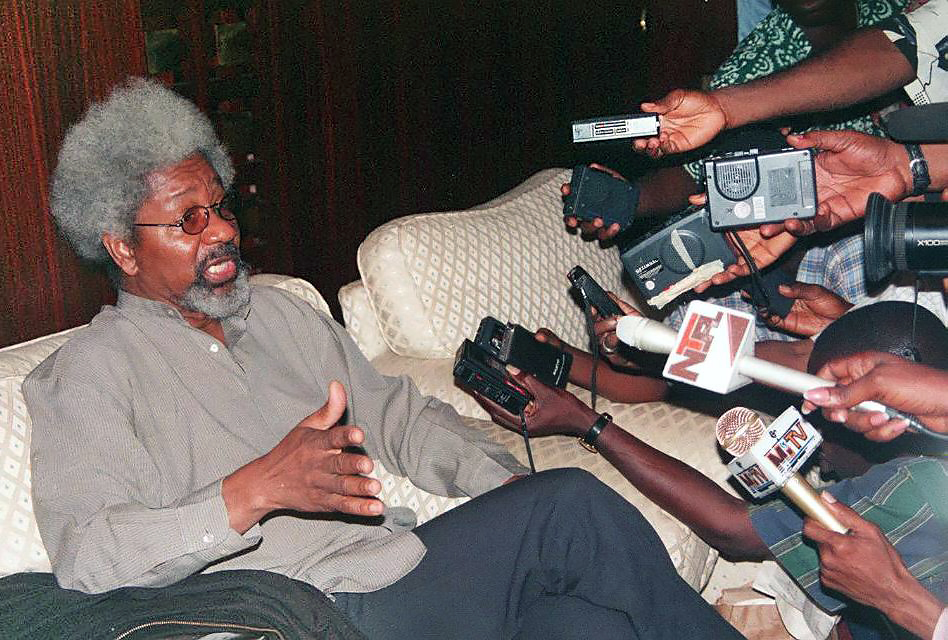

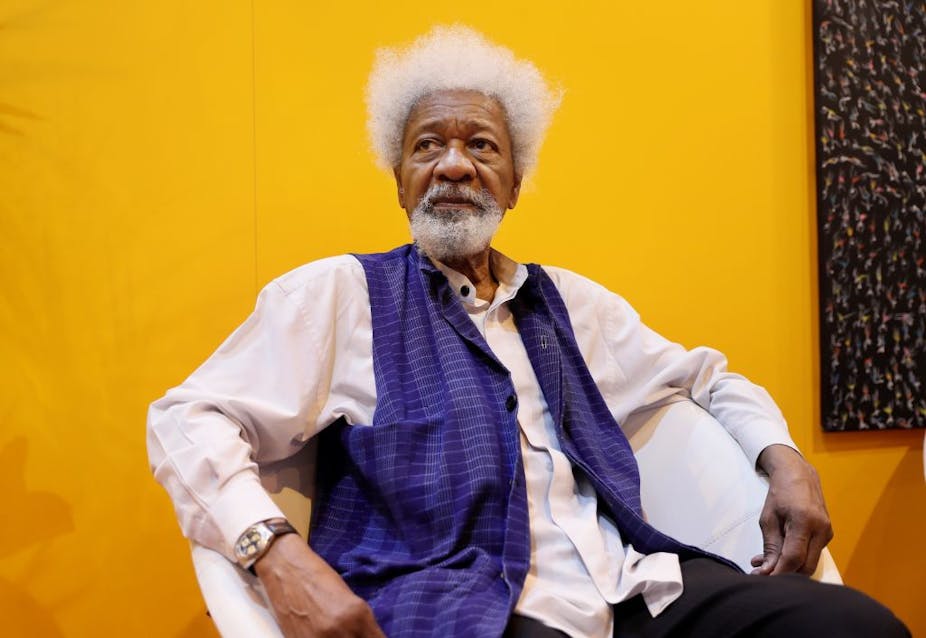

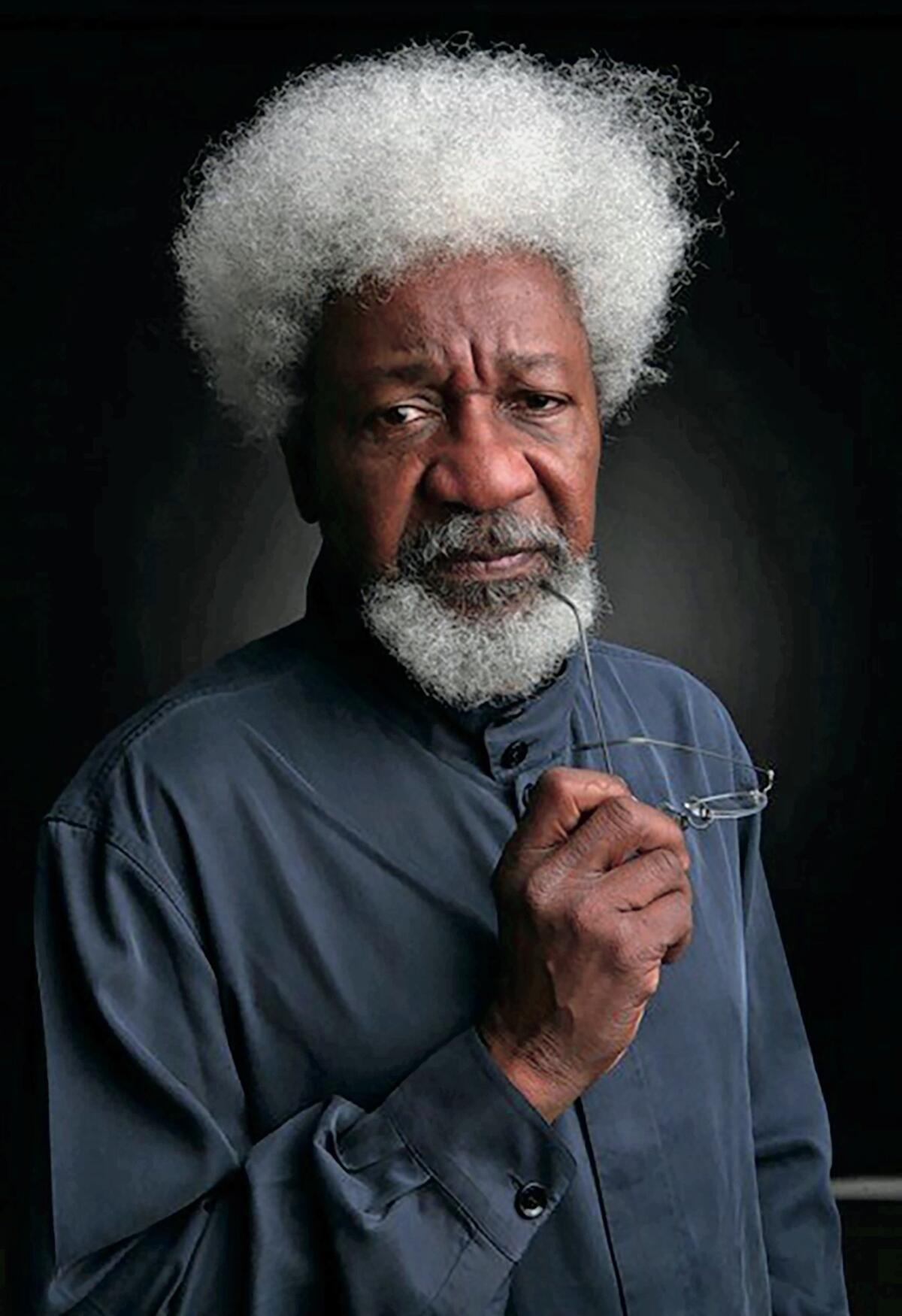

Wole Soyinka is writer-warrior: at 89, he still has his abundant hair, lanky frame and lavish beard, which give him the look of a charming mad scientist.

Born in 1934 in Abeokuta, in the forested land of the Yoruba region of southwestern Nigeria, he was the first African writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, winning in 1986. He studied in England, founded two theatre companies [in 1960 and 1964], is a professor of comparative literature, was primarily exiled in the U.S., and currently lives between Nigeria and California. His impact on the history of literature is rivaled only by his political activism. Jailed in his homeland in the sixties, he served twenty-two months in solitary confinement out of twenty-seven months of incarceration. His prolific work—over 45 published plays, poems, essays, memoirs, novels—has been translated into dozens of languages.

Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth is his third novel, and his first in nearly fifty years. Recently released in French by Editions du Seuil, it was originally published in English two years prior by Pantheon Books. Soyinka dedicates the novel to the memory of two of his compatriots and friends, the investigative journalist Dele Giwa, and governor and lawyer Bola Ige. Both were assassinated in their homeland. He recalls his friend Giwa having immediately showed up at Soyinka’s sister’s home where he was staying in Lagos, clutching a bottle of Cognac XO, basically in his pajamas, when the news of his Nobel was announced. Giwa was blown up by a package bomb that was sent to him days after this celebratory reunion. As for Bola Ige, a former attorney-general and lawyer, he was assassinated in 2001 at his home on the eve of his departure for the United States to take up his new job as Africa’s representative on the United Nations international law commission. His wife used to call Soyinka and her husband twins, because of the way they were involved in so many political activities together.

This close circle dedicated to the service of humanity reflects Soyinka’s remarkable life and restless persona. His uncle, Oludotun Ransome-Kuti (musician Fela Kuti’s father) ought to be mentioned here. Soyinka wanted to write his biography and through him write on that first generation of nationalists to which his Kuti belonged. That was to remain an unaccomplished project; his uncle died soon after, Nigeria got its independence in 1960, and he gave up the idea. What happened then? “Well, you know, when you are in prison you have a lot of time on your hands,” he tells me with sly amusement. Deprived of paper and pen by the prison directorate, he found a way to create his own writing material from whatever outlet he could—Soyinka playfully calls himself “Soy-Ink”—and he proceeded to write on cigarette papers, rolls of toilet paper, and in between the lines of a book he had managed to have smuggled in. He envisioned those scraps as the outline of the first chapter of what would have been his uncle’s biography, but they turned out to be the groundwork for his own moving memoir Ak é : The Years of Childhood , one of the best books of 1982 according to The New York Times Book Review .

We meet on a Friday, in the hall of his hotel, located on a quiet street by Saint-Germain-des-Près. It’s unusually hot in Paris for the season. He has a lunch appointment he wishes to get to and he says his voice is tired, brushing off any attempt to extend the interview. Wearing a Mao collar shirt and a dark blue sleeveless vest, he has on his right wrist a silver watch and a light tote bag is kept close-by. He momentarily looks for his hat, which he thinks he has left at an event he spoke at the night before, and makes the point that he wants it back.

“What keeps you young, what’s your secret?” I ask, right off the bat, to ease the mood.

“I have no idea,” he sighs. “I should be slowing down, I know, but each time I try to slow down something happens, and I have to get on the trail again. You see, I am deprived of that sense of inner tranquility once I turn my back on a situation. Quite frankly, I think it’s a flaw, because I am depriving myself of something which I know I need profoundly. If I didn’t manage to have some quiet in my mind, I’d have gone crazy years ago, so it’s a question of extracting myself [from the world] whenever I can.”

Soyinka calls this being a closet masochist. “It means depriving oneself of what one feels is pleasurable,” he explains. “You have to battle for your creative space, battle for it! Extract yourself whenever you can and be thankful for it, and just carry on waiting for the next opportunity to gratify your innermost instinct to disappear, and do not sacrifice it. If you can manage to balance the two [the activism and the writing] that’s OK, but if you find that you are being tortured internally then be quiet, just close the shop, run and go.”

His strong sense of social justice caused him a lifetime of pressure and persecution; yet he persevered. “I know it’s unbelievable but I really just prefer my peace of mind; I like to sink myself in a truly tranquil environment, which I find mostly in the forest. But [he raises his voice pronouncing those three letters], but, if between getting out of your house and getting into the forest you encounter something unacceptable on the way then that becomes a problem, and you cannot just enjoy what you really want until you have dealt with what you just saw.”

Puzzled, I query him whether that means he never intended to become a writer engagé . “No! Never!” he replies, without skipping a beat. “I don’t know,” he shrugs. “One shouldn’t expect literature to be committed. It is sufficient that a writer opens up possibilities. The fact is that something is being presented, a different view is presented, that’s what matters. The writer must be honest, if you have a bad temperament—of confrontation, of poking your finger in the eye of power—then by all means do so but if you do not don’t feel useless, don’t feel like you are betraying literature. You are writing, that’s your mission, that’s your m é tier ; exploit it in whatever direction it leads.”

The year is 1986: Wole Soyinka wins the Nobel Prize in Literature, and Elie Wiesel is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. What was the promise of the world then and what is its state today? Wars and displacement, corrupted systems and dictators, religious fundamentalism and brutality linger. “Take Gabon for instance [in late August, the army seized power disputing the election results in which Ali Bongo was declared winner; he had been president since 2009 and his father for 41 years before him], one family dynasty in power for fifty years, manipulating elections consistently, it was asking to be toppled, it deserves to be toppled—but—is the military the answer? The military has shown itself to be just as decadent, just as corrupt as the rest. Its claim to be a cleansing broom has been detonated, the only defense they have is to legitimize their terror. They will leave eventually, but look at the setback, it is heartbreaking.”

Soyinka’s art has always found its genesis in the African continent’s myths and mystifications, and in his own life experiences—he has been jailed on two occasions, in 1965 and again from 1967-1969, tortured, condemned to death by dictator Sani Abacha, and forced repeatedly and for long periods into hiding for his own safety. What can literature do in the face of such chaos, injustice, and violence? “Well,” he says in a hoarse voice, “present a model of possibilities, and that is all. Beyond that, nothing. The fact that literature is not helpless is proven by the fact that it attracts power. Those who hold power use it to censor, to harass [writers] so literature is not as helpless or insignificant as some people think.”

We turn to the subject of his incarceration: how does prison change a man? “When I came out, I was very bitter, not bitter about being in prison, I was bitter about the treatment I received, but most importantly of all the statements that were attributed to me which were false. My immediate writing was bitter, then I settled on looking at society and looking at the human condition and creating microworlds which is what all writers do. One of the problems one has as a writer who writes about society is the danger of becoming pessimistic, resentful, and aggressively so.”

The immediate writing he refers to is Madmen and Specialists , a play about the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970), considered the writer’s darkest dramatic work. He recounted his years behind bars in 1972’s The Man Died: Prison Notes , which the Nigerian government eventually banned in 1984. His play Death and the King ’ s Horseman , first performed in 1976, brings Soyinka worldwide acclaim.

Wole Soyinka does not regard himself as a novelist; he refers to his novels as “accidents.” His debut, The Interpreters , was published in 1965, followed by Season of Anomy in 1973. He swears that this one, his third, is his last. “Oh, I am not going that way again! I just know it intuitively. A novel is hard labor. A play is unfinished and on stage it gets finished, so you don’t really mind, because you know that on stage you will have an opportunity to change things here and there. Theater is a dynamic process. A novel is frozen, until maybe a filmmaker is foolish enough to attempt to put it on celluloid.”

Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth is set in an imaginary Nigeria and examines the unreasonable and unethical contemporary state of affairs there. In the US, it has been received by some as pessimistic, while others, particularly in Europe, have welcomed it as political satire. “Although it’s not for me to decide, some say it’s also a Whodunit, and I say: absolutely, why not? I love detective stories, I used to eat them up in my youth, and I always said, one of these days I will write a detective story.” He laughs. “It wasn’t my intent at the start, but along the writing process it came to me that I could tag on a mystery element.”

Soyinka can create a story out of anything and he can write anywhere, but distance can help. “I had to get out of Nigeria to write [ Chronicles ]. I had to wait year after year to feel completely detached from the physical environment I was writing about. I wrote some parts of it in Senegal and in Ghana. Then Covid happened, it was touch and go, and the world began to button down. I was in Los Angeles at my son’s wedding; it was the last social event for us as a family, people had come from all over. When I realized that the lockdown was fast approaching I knew I had to go back to Nigeria, which is the only home I consider home. So I said: Listen, I’m getting on that plane, the rest of you, wherever you are locked-down, good luck to you. I couldn’t get back into Lagos directly, I had to go to Ghana and then continue by road, but I made sure I arrived in the nick of time to Abeokuta. And that’s where I finished Chronicles .”

When Soyinka is not keen on something he makes sure the message gets through loud and clear. In 2016, after the election of Donald Trump as the 46th President, he destroyed his U.S. Green Card. That same year, the Nobel committee’s literary laureate was Bob Dylan, “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” Wole Soyinka’s discontent vibrates the room. “The prize for literature should have never gone that way!” he tells me, his fingers fidgeting in the air. “As a music lover, and a composer myself, I respect music, but there is something called literature, and we don’t have enough prizes as is. If they award this prize to one more musician, I am sending all my musical compositions to the Grammys. I know what I consider literature, and writing lyrics or certain songs, is not literature, it is music! You want to have a Nobel Prize for music, fine, I’ll be there, but don’t say that you are taking a prize away from this discipline and extending it to another!”

On that note, he grows impatient. He has an appointment, which means I have one last question: What has the Nobel meant for his life? “It has changed nothing at all for me. All it has done for me is that since then I have to fight for my anonymity.”

Wole Soyinka leaves not a minute later. It’s sunny out. And his hat is still missing.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Aysegul Sert

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Masha Gessen and Nathan Thrall on The Whole Story of Israel and Palestine

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Wole Soyinka: ‘This book is my gift to Nigeria’

The Nobel laureate has produced plays, poems, essays and even inspired a pop duo but he hasn’t written a novel for nearly half a century - until now

A t 87, Wole Soyinka is a Nigerian icon. His plays have been performed around the world, his poems anthologised, his novels studied in schools and universities, while his nonfiction writing has been the scourge of many a Nigerian dictator. He was imprisoned for 22 months during the Nigerian civil war in the late 1960s for attempting to broker peace; his activism led him again into exile two decades later during the era of General Sani Abacha, military ruler of Nigeria, when the environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa was hanged.

In 1986, he was awarded the Nobel prize in literature and became the first African laureate, but his status in Nigerian letters was secured long before then. For a generation of young Nigerian writers, his work has been transformative. It has inspired artists, too – in Lagos, many display their skill by painting famous faces, his among them. There was even a musical duo called Soyinka’s Afro.

Born in Abeokuta, in south-west Nigeria, in 1934, Soyinka chronicled his colourful childhood in his memoir, Aké. He studied English literature at both the University of Ibadan and the University of Leeds, and now lives not far from his birthplace with his wife, Folake Doherty-Soyinka.

Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth , Soyinka’s first novel in nearly half a century, is published in the UK this month. It is a high-jinks state-of-the-nation novel that follows a religious leader, a politician, a media baron and a group of university friends as they scheme their way through a version of present-day Nigeria. The satire and the commentary on Nigerian politics and society are trademark Soyinka. We talked in late August on Zoom; I was in London and Soyinka was at home, with bird song trilling in the background. We discussed his latest novel, his thoughts on Big Brother Africa, how far he has travelled from his childhood, and his hopes for Nigeria.

Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth is your first novel in 48 years . Why now? What is special about this moment? The themes in this novel have been constantly with me in various forms, from sketches and polemics to poetry. The ideas have been gathering in a cumulative fashion. And finally I just said: let me try putting all this down in prose once and for all.

The book has a large cast of characters from very different walks of life: Sir Goddie, the prime minister of this fictionalised Nigeria; engineer Pitan-Payne, crusading against corruption; Papa Davina, founder of “Chrislam”, a hybrid of Christianity and Islam – and many more. How did you keep track of them all? That is a very good question and I’m glad you asked for the sake of young novelists who have to use this marvellous instrument called the computer. They may think that the computer is a help. Believe me, the computer can be an enemy. I’m giving you secrets of the trade, as I learned the hard way with this novel. You must number drafts very carefully. That’s the only way to do it.

Which comes first for you : plot or character? I suspect character. Events evolve out of character more than the other way round.

Religious leaders are satirised in this novel, as they are in your play, The Trials of Brother Jero . What role do you think religion plays in Nigerian life? Religion has been a fascinating component of my environment since childhood. At the beginning I was a believer. As a child, it was beaten into me, but as I matured, I began to look more closely at some of these claims and characters. Many of them were very colourful. As society became more materialist, more cynical, more unscrupulous, you had people taking to religion strictly for criminal business. As a writer, one is attracted by their creativity. They have more to offer in terms of drama.

I enjoyed the range of contemporary references. If you are familiar with the Nigerian political landscape, you might even recognise thinly veiled satirical characters. Did you have to research the novel, or was all the material in your mind already? Events around me just reached a kind of crisis point. Society really became insupportable in terms of what one could absorb on a daily basis. I make no bones about it: a lot of events are taken from real life. Some characters have been taken from real life, but then fictionalised. It is one of the reasons why I aimed to release the book before the 60th anniversary of Nigerian independence. I wanted this to be my present to the nation, to the people who live here: both the governed and those who govern, the exploiters and the exploited.

The novel also has a lot of cultural references, for example to Big Brother Africa . Do you now watch Big Brother Naija [formerly Big Brother Nigeria]? I find it nauseating. I watched Big Brother Africa out of duty when it first came out [in 2003]. My friends used to rush home. They would say: “Excuse me, I must get back. I’ve got to watch this episode.” I think I managed about two and a half episodes. But the voyeurism was totally contrary to everything I believed. So I haven’t seen the new version at all. I’m not going near it.

The title, Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, seems to be a critique of Nigeria: we are happy despite all that is going wrong. Fela Kuti also criticises this trait in his song Shuffering and Shmiling , where he lambasts the populace for putting up with terrible conditions. Would you describe yourself as happy ? That title came about when I read somewhere a few years ago that Nigerians were among the top 10 happiest people in the world. And I looked at that statement and thought: “What? Is this the same Nigeria we’re talking about?” So the title is meant to be ironic. It’s certainly not a truthful description of what I encounter on a daily basis or what you see when you pick up the newspapers. Am I happy? Right now, I’m very content because I’m in my environment. When I step out of this environment, my heartbeat races. So I don’t use that word, happy. And I don’t use the word unhappy. I try to attain a state of equilibrium where I can function as a human being. That’s all.

You choose to live in Nigeria when you could live anywhere in the world. Why? I’m a lazy person. I’m accustomed to this environment. Each time I was in exile, I found I really could not feel at home elsewhere, not completely.

In the acknowledgments, you thank a colleague with a cottage in Senegal and John Agyekum Kufuor , the former president of Ghana, for giving you “creative seclusion to write this novel”. Do you feel you can’t write in Nigeria? Oh no. I do write in Nigeria. It’s just that this particular theme required detachment from Nigeria. On my first stint in Senegal, I set down a chunk of the novel. Then I had to go back to earning a living. Believe it or not, I still have to do that, going out lecturing and so on. And then I started looking for another short stretch. President Kufuor, a friend, offered what I call his baronial house in Ghana. So I moved from that little cottage by the seaside to the lap of luxury. I was looked after hand and foot and I was very appreciative of both.

Does becoming a Nobel laureate mean that you feel more pressure when you sit down to write? None whatsoever. I always advise the younger generation, don’t submit to pressure. If you feel pressure of the sterile kind – which is, “I ought to write, I should write” – don’t. Just go out and do something else. Immerse yourself in the environment. Go to a bar. Get drunk. Well, try not to get drunk but just do something else, something positive. Read a book, go for a walk, interact with other people, watch nature, go out in the street and walk about with people. You’ll be astonished how quickly the material starts flowing in your mind.

You’ve had many years of activism through both your words and your actions. What did you think of the recent end S ars [the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, a notorious unit of the Nigerian Police] protest , with young Nigerians calling for good governance and an end to police brutality? That was a tragic event. It began in the heights of euphoria. I was so delighted and relieved that the young generation, whom I’ve always insulted as being lazy and waiting for salvation, got its act together and took on these brutes called the Sars. And of course, it wasn’t just the Sars. It was more than that. It was an expression of discontent. To see this structured movement, I felt rejuvenated. I said: “At last, it’s happening,” and then what happened? The thugs took over. The villains took over. The underworld got in on the act. Prisoners were let loose. It was very depressing.

Do you have hope for Nigeria’s future? Oh, hope. Again, that’s another word that I don’t use, like happiness. When you even mention the word Nigeria, I don’t know what that is. I feel nothing for it because it’s totally diverged from what I knew as Nigeria as a child. I don’t recognise this country. That’s the truth. And so to that question, my answer is very mixed.

You always look very good. What is your secret? You think I look good? I’ll tell my wife. I live a normal life, I hope. I eat whatever is put before me. Eba, pounded yam, rice, plantain. I have no special body care. I don’t jog. I don’t, what do they say, “work out”. From time to time, I do go out hunting. Only what’s eatable. Not trophy or safari. So maybe that’s it.

What’s your take on the contemporary African writing scene ? Very healthy. There is a marvellous crop of young writers, particularly young female writers, who really have become a pride to the continent.

Your memoir, Aké, is one of my favourite books of all time. I loved reading about your adventures with your mother, who you call Wild Christian . I wonder how you got away with that. Let me tell you what she did one day. We launched the book in the old schoolroom in Aké where I grew up. She hadn’t read it but she’d been teased about it. And so as we returned home, amid all these people, she came to me, pretended she wanted to whisper something in my ear. Then she took my ear, twisted it and said: “That’s for Wild Christian!” So I said: “You see why I call you Wild Christian. You’ve come here to disgrace me in front of all these people.” That’s what she did.

Saturday magazine

This article comes from Saturday, the new print magazine from the Guardian which combines the best features, culture, lifestyle and travel writing in one beautiful package. Available now in the UK and ROI.

That’s a good story. I gave her that name because she was a real believer. Her Christianity was a wild one. She really believed that she had a secret communication line with God. If anything went wrong she would say: “I’ve offended Papa God.” And I would say to her: “Papa God is not interested in whether or not you poured your oil in the right place or not. He’s too busy.” Then she’d chase me out. She was the genuine article. Having abandoned Christianity, I always marvelled how anybody could be so passionate. There are people like that and I respect that.

So would the young Wole Soyinka in Aké believe how far you’ve gone in life – Nobel prize, accolades, prestige? I don’t think that’s a question I’m capable of answering. For the simple reason that I never really looked for fame. I wanted to be content and fulfilled according to my own standards. I wanted to be able to live with myself and do what I set out to do. It didn’t matter what.

- Wole Soyinka

Most viewed

BlackPast is dedicated to providing a global audience with reliable and accurate information on the history of African America and of people of African ancestry around the world. We aim to promote greater understanding through this knowledge to generate constructive change in our society.

Wole soyinka (1934- ).

Akinwande Ouwole “Wole” Soyinka, the first African writer to win a Nobel Prize in Literature (1986) was born in Abeokuta, Nigeria on July 13, 1934. His father, Canon S.A. Soyinka, was an Anglican minister and his mother, Grace Eniola, was the daughter of an Anglican minister.

Soyinka received a primary school education in Abeokuta and then completed secondary school at Government College, Ibadan . He attended the University of Ibadan for two years (1952-1954) before completing his undergraduate education at the University of Leeds in England in 1957. Soyinka received his degree in drama at Leeds under the instruction of world-renowned Shakespearean critic G. Wilson Knight. He worked briefly as a play reader at the Royal Court Theater in London before returning to Nigeria to study African drama. Soyinka taught at the University of Lagos, the University of Ibadan, and the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University) in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. On the faculty at the latter institution since 1975, he is currently a Professor of Comparative Literature.

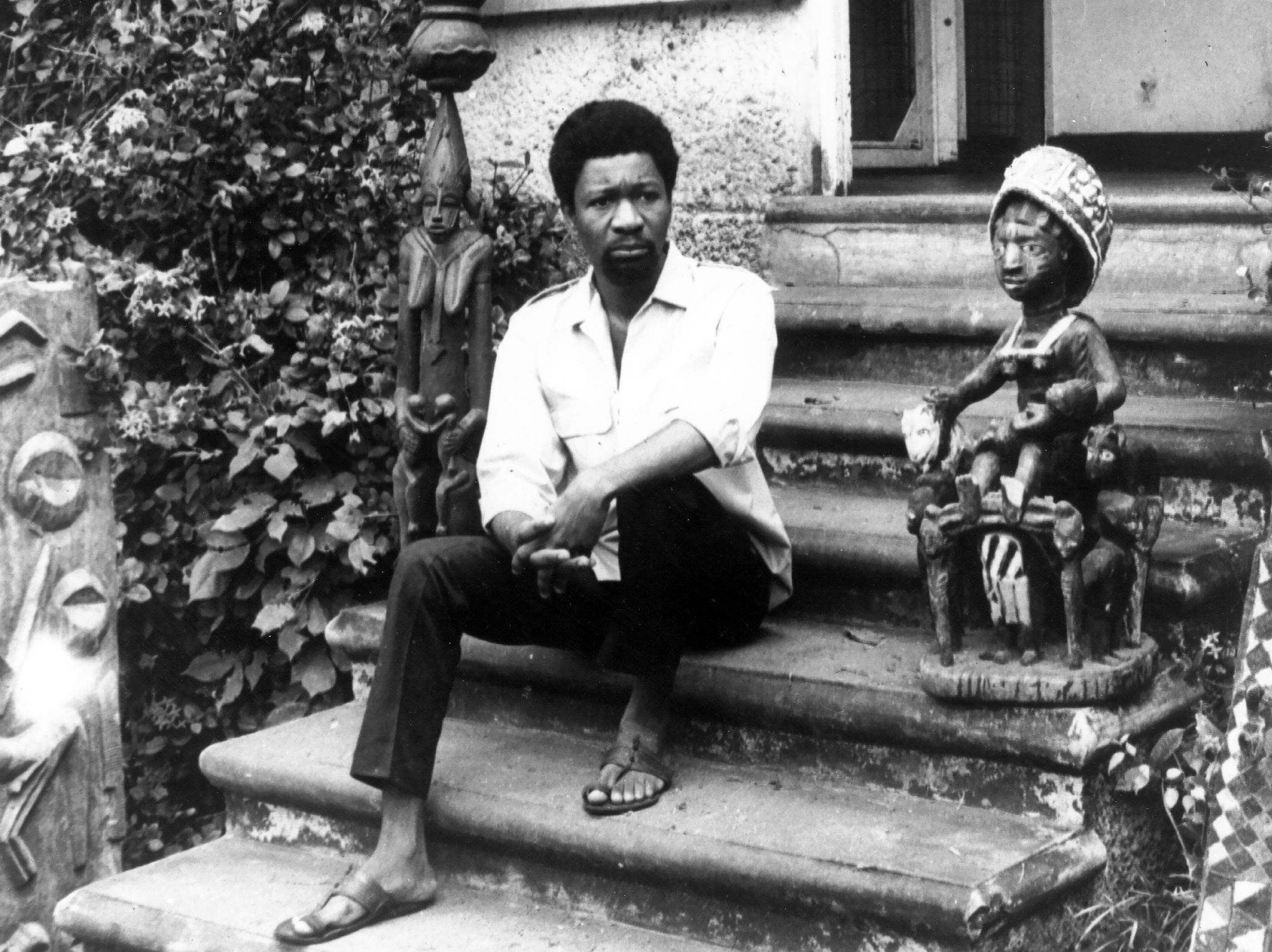

Soyinka wrote his first major plays, The Swamp Dwellers and The Lion and the Jewel, while working at the Royal Court Theater in London. His next plays, The Trials of Brother Jero and A Dance of the Forest appeared after he returned to Nigeria in 1960. A Dance of the Forest , a biting criticism of Nigeria’s elites, was first performed on October 1, 1960, Nigeria’s Independence Day. In 1963, Soyinka’s first feature length film, Culture in Transition , was released. One year later, The Interpreters , his most famous novel, was published in London. Both pursued a similar theme.

By 1965, Soyinka’s reputation as a leading dramatist and a political critic of the government was well established. That year Soyinka was arrested for his criticism of recent elections but was released after protests from the international community. In 1967, he secretly and unofficially met with Ibo leaders in a vain attempt to prevent the Nigerian Civil War . When the war began Soyinka was declared a traitor and was incarcerated for the remainder of the war.

After his release, Soyinka lectured and lived in Europe. By 1975, he had returned to Africa and lived briefly in Accra , Ghana, where he edited a literary magazine called Transition . He used the magazine to critique African dictators such as Idi Amin in Uganda. He returned to Nigeria later that year after his political nemesis, General Yakubu Gowon , was removed from power. For the next decade he continued his writing and political protests prompting more government repression. His 1984 play, The Man Died , was banned by a Nigerian court. In 1986, however, Soyinka won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In November 1994 Soyinka fled Nigeria and briefly lived in exile in the United States. In 1996, while in the U.S., he wrote The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis . The following year, he was charged with treason by the Nigerian military government. Soyinka returned to Nigeria when civilian rule was restored in 1999. However, his critique of the government continues. In April 2007, he called for the cancellation of Nigerian elections due to widespread violence and fraud.

In a career that has lasted more than five decades, Soyinka has written twenty-one plays, eight books of poetry, five books of essays, two novels, and five memoirs. He has also produced two feature-length films. Wole Soyinka lives in Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Cite this entry in APA format:

Source of the author's information:.

Biodun Jeyifo, Wole Soyinka: Politics, Poetics and Post Colonialism (New York: Cambridge Press, 2004); http://prelectur.stanford.edu/lecturers/soyinka/ .

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.

Wole Soyinka’s life of writing holds Nigeria up for scrutiny

Lecturer in African and African Diasporan Literature, University of Lagos

Disclosure statement

Abayomi Awelewa received funding from the American Council of Learned Society (ACLS) for his Africa Humanities Program (AHP) Fellowship.

University of Lagos provides support as an endorsing partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

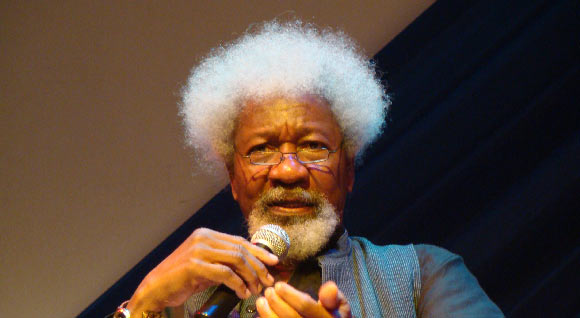

Akinwande Oluwole Babatunde Soyinka, known simply as Wole Soyinka, can’t be easily described. He is a teacher, an ideologue, a scholar and an iconoclast, an elder statesman, a patriot and a culturalist.

The Nigerian playwright, novelist, poet and essayist is a giant among his contemporaries. In 1986, he became the first sub-Saharan African, and is one of only five Africans, to be awarded the Nobel prize for literature. This was in recognition of the way he “fashions the drama of existence” .

His works reveal him as a humanist, a courageous man and a lover of justice. His symbolism, flashbacks and ingenious plotting contribute to a rich dramatic structure. His best works exhibit humour and fine poetic style as well as a gift for irony and satire. These accurately match the language of his complex characters to their social position and moral qualities.

His works have such impact that some of them are used in schools in Nigeria and some other anglophone countries in West Africa. Some have also been translated into French .

Life and activism