Highlights from a New Report on Indicators of Workplace Violence

Federal agencies recently published a joint statistical report on workplace violence entitled Indicators of Workplace Violence, 2019 . The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) examined incidents of fatal and nonfatal violence that occurred against persons at work or on duty, or violence that was away from work but over work-related issues from 1992 to 2019. The report includes data for 13 indicators of workplace violence from five federal data collections. The purpose of this report was to make summary data from a variety of sources readily available. It does not attempt to explore reasons for workplace violence.

Workplace Homicide

The study found that, over a 27-year period (1992 to 2019), 17,865 persons were killed in a workplace homicide, according to data from BLS’s Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries. Homicides in the workplace peaked at 1,080 homicides in 1994 and dropped to 454 in 2019, a decline of 58%. During a more recent period from 2014 (409 homicides) to 2019, workplace homicides increased 11%. The remainder of the report’s analysis on workplace homicide focuses on data from 2015 to 2019.

From 2015 to 2019:

- 21% of victims of workplace homicides worked in sales and related occupations. Protective-service occupations, notably police officers and security guards, accounted for 19% of workplace homicides. Persons in management occupations (e.g., owners or managers of restaurants and hotels) accounted for 9% of workplace homicides.

- 82% of victims of workplace homicide were male.

- 46% (1,052) of workplace homicide victims were white. White individuals also made up 66% of all workplace fatalities. Black individuals accounted for 25% (579) of workplace homicides and experienced 11% of all workplace fatalities. Hispanic individuals accounted for 16% (368) of workplace homicides and 18% of all workplace fatalities.

- 66% of workplace homicide victims were ages 25 to 54.

- 23% of victims of workplace homicides were self-employed.

- 79% of workplace homicides were shootings.

Nonfatal Workplace Violence

Workplace violence crimes.

In 2019, the rate of nonfatal workplace violence was 9.2 violent crimes per 1,000 workers ages 16 or older, according to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). This was a 25% increase from 2015, when the rate was 7.4 per 1,000. However, it was 70% lower than the 1994 rate of 31.0 violent crimes per 1,000 workers. The rate of total nonfatal violent crime followed a similar pattern.

From 2015-2019:

- An annual average of 1.3 million nonfatal workplace violent victimizations occurred during the combined 5 years from 2015 to 2019, including about 53,000 rapes or sexual assaults, 46,000 robberies, 186,000 aggravated assaults, and 979,000 simple assaults per year.

- The average annual rate of nonfatal workplace violence was 8.0 nonfatal violent crimes per 1,000 workers ages 16 or older.

- Males committed the majority of nonfatal workplace violence (64%).

- Strangers committed about half (47%) of nonfatal workplace violence, with male victims less likely than female victims to know the offender.

- The offender was armed in 16% of nonfatal workplace violence.

- Offenders were armed in about 24% of nonfatal workplace violence against workers in retail sales and in 24% of nonfatal workplace violence against those in transportation occupations.

- Overall, 12% of nonfatal workplace violence involved injury to the victim. However, nearly a quarter (23%) of nonfatal workplace violence against workers in medical occupations resulted in victim injury.

- Fifteen percent of victims of nonfatal workplace violence reported severe emotional distress due to the crime.

- About 39% of all nonfatal workplace violence was reported to police.

Emergency department-treated workplace violence injuries

About 529,000 nonfatal injuries from workplace violence were treated in hospital emergency departments (EDs) for the combined 2015 to 2019 period, based on data from NIOSH’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Occupational Supplement. This was a rate of 7.1 ED-treated injuries per 10,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) workers. Physical assaults (e.g., hitting, kicking, or beating) accounted for 83% of such injuries. The ED-treated injuries were most often contusions and abrasions (33%), followed by sprains and strains (12%) and traumatic brain injuries (12%). Beginning with workers ages 25 to 29, the rate of ED-treated injuries due to workplace violence decreased as workers’ ages increased.

Workplace violence injuries resulting in days away from work

In 2019, female workers (5.1 cases per 10,000 FTEs) had higher rates than males (2.3 per 10,000) of nonfatal injuries due to workplace violence resulting in days away from work. The same year, female workers accounted for 65% of the 37,210 nonfatal injuries due to workplace violence involving hitting, kicking, beating, or shoving that resulted in missed work. Male workers accounted for 82% of the 340 injuries involving an intentional shooting that resulted in days away from work.

Data Sources and Collections

This report uses data from five federal data collections—the National Crime Victimization Survey (sponsored by BJS), the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System – Occupational Supplement (sponsored by NIOSH and the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission), the National Vital Statistics System (sponsored by the National Center for Health Statistics), the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (sponsored by BLS), and the Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses – Case and Demographics (conducted by BLS). Due to different data sources, estimates in this report could not always be presented consistently and are not always comparable.

Conclusion and Discussion

Workplace violence continues to negatively affect workers, organizations, and communities. This report provides a multi-faceted snapshot of the issue and establishes reliable indicators. Regular updating and monitoring of data on the topic remains critical in guiding law enforcement, researchers, policymakers, and occupational safety specialists in understanding the extent, nature, and context of violence in the workplace that will enable them to effectively address this problem.

Amid the ever-changing landscape of what work looks like, additional indicators may prove helpful in understanding how workplace violence continues to manifest. What additional data are needed to better understand and monitor the occurrence of workplace violence? Moreover, what effects did the COVID-19 pandemic have on workplace violence across the country? Please share your thoughts in the comment section below.

Erika Harrell of the Bureau of Justice Statistics

Jeremy Petosa and Nicole Dangermond of the Bureau of Labor Statistics

Susan Derk, Dan Hartley and Audrey Reichard of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Department of Labor measures labor market activity, working conditions, price changes, and productivity in the U.S. economy to support public and private decision making.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health , part of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is a research institute focused on the study of worker safety and health, and empowering employers and workers to create safe and healthy workplaces.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics of the U.S. Department of Justice is the principal federal agency responsible for collecting, analyzing and disseminating reliable statistics on crime and criminal justice in the United States.

The Office of Justice Programs provides federal leadership, grants, training, technical assistance and other resources to improve the nation’s capacity to prevent and reduce crime, advance racial equity in the administration of justice, assist victims and enhance the rule of law.

3 comments on “Highlights from a New Report on Indicators of Workplace Violence”

Comments listed below are posted by individuals not associated with CDC, unless otherwise stated. These comments do not represent the official views of CDC, and CDC does not guarantee that any information posted by individuals on this site is correct, and disclaims any liability for any loss or damage resulting from reliance on any such information. Read more about our comment policy » .

You need to gauge the workplace violence against Healthcare workers, especially in Hospitals.

Thank you for your comment. Some of the data sources used in this document offer the ability to look at occupations within industries. We will consider that possibility for future iterations of this document.

Small-scale mining. Apply international studies (WHO, Minamata) to America. Thank you.

Post a Comment

Cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- 50th Anniversary Blog Series

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aging Workers

- Agriculture

- Animal/Livestock hazards

- Artificial Intelligence

- Back Injury

- Bloodborne pathogens

- Cardiovascular Disease

- cold stress

- commercial fishing

- Communication

- Construction

- Cross Cultural Communication

- Dermal Exposure

- Education and Research Centers

- Electrical Safety

- Emergency Response/Public Sector

- Engineering Control

- Environment/Green Jobs

- Epidemiology

- Fire Fighting

- Food Service

- Future of Work and OSH

- Healthy Work Design

- Hearing Loss

- Heat Stress

- Holiday Themes

- Hydraulic Fracturing

- Infectious Disease Resources

- International

- Landscaping

- Law Enforcement

- Manufacturing

- Manufacturing Mondays Series

- Mental Health

- Motor Vehicle Safety

- Musculoskeletal Disorders

- Nanotechnology

- National Occupational Research Agenda

- Needlestick Prevention

- NIOSH-funded Research

- Nonstandard Work Arrangements

- Observances

- Occupational Health Equity

- Oil and Gas

- Outdoor Work

- Partnership

- Personal Protective Equipment

- Physical activity

- Policy and Programs

- Prevention Through Design

- Prioritizing Research

- Reproductive Health

- Research to practice r2p

- Researcher Spotlights

- Respirators

- Respiratory Health

- Risk Assessment

- Safety and Health Data

- Service Sector

- Small Business

- Social Determinants of Health

- Spanish translations

- Sports and Entertainment

- Strategic Foresight

- Struck-by injuries

- Student Training

- Substance Use Disorder

- Surveillance

- Synthetic Biology

- Systematic review

- Take Home Exposures

- Teachers/School Workers

- Temporary/Contingent Workers

- Total Worker Health

- Translations (other than Spanish)

- Transportation

- Uncategorized

- Veterinarians

- Wearable Technologies

- Wholesale and Retail Trade

- Work Schedules

- Workers' Compensation

- Workplace Medical Mystery

- Workplace Supported Recovery

- World Trade Center Health Program

- Young Workers

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Unit 9: Introduction to Case Studies and Case Study 1: Psych Patient in ED

Proceed to Introduction to Case Studies .

Unit 9 Introduction to Case Studies and Case Study 1: Psych Patient in ED

Exit notification/disclaimer policy.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Jennifer Kramer

- Brandon Ruiz

- Shoshee Hui

- Dat T. Phan

- Gabriel Rishwain

- Courtney Luengo

- Wendy Camacho

- Veronica Gomez

- Employment Law

- Sexual Harassment

- Age Discrimination

- Disability & ADA Compliance

- Gender Discrimination

- Pregnancy & FMLA

- Race & National Origin

- Religious Discrimination

- Sexual Orientation & Gender Identification

- Wrongful Termination

- Retaliation

- Contract Workers Rights

- Minimum Wage

- Salary Hourly Classification

- Wage & Hour Class Action

- Civil Right Federal Subsection 1983

- Qui Tam Government Contract Fraud

- Pharmaceutical Sales

- Refuser Cases

- Privacy Rights

- Claims By Public Entity Employees

- Areas Served

- In The News

- Case Results

True Stories of Workplace Bullying: Case Examples to Help You Understand Your Rights

Do you think you’re being bullied at work? If so, your workplace bully could be violating California and Federal law due to their harassing behaviors. While bullying itself is not unlawful, there are anti-bullying legislative measures being brought to the forefront all across the country, including the Healthy Workplace Bill. In addition to anti-bullying legislation, the Workplace Bullying Institute is also striving to eradicate bullying on the job by dedicating their efforts to anti-bullying education, research, and consulting for individuals, professionals, employers, and organizations.

Workplace bullying comes in many forms and can be unlawful if this type of harassment is based on an employee’s national origin, age, gender, disability, or other protected characteristics. Bullies also typically engage in these unlawful behaviors more than once rather than in isolated incidents.

In the spirit of the Workplace Bullying Institute’s Freedom from Workplace Bullies Week, we’ve decided to offer some insight into real workplace bullying, retaliation and discrimination cases from around the country that can help you understand your own rights when it comes to employment harassment.

Table of Contents

Real Workplace Bullying Case Examples

Microsoft to pay $2 million in workplace bullying case.

AUSTIN, TX – After seven years, Michael Mercieca finally saw the courts order Microsoft to pay for workplace bullying that almost led him to the breaking point.

The Texas employment labor law case judge, Tim Sulak, found Microsoft guilty of “acting with malice and reckless indifference” in an organized program of office retaliation against Mercieca.

“They (Microsoft Corporation) remain guilty today, tomorrow and in perpetuity over egregious acts against me and racist comments by their executive that led to the retaliation and vendetta resulting in my firing,” said Mercieca.

Previously, a jury, by unanimous agreement, found that Microsoft knowingly created a hostile work environment that led to Mercieca’s constructive dismissal. Mercieca was a highly regarded member of the tech giant’s sales department and had an unblemished record, but found himself trapped in a workplace conspiracy where his supervisors and coworkers undermined his work, falsely accused him of sexual harassment, and expense account fraud, marginalized him, and blocked his promotions. These harassing behaviors began when Mercieca ended a relationship with a woman who then went on to become his boss. Human relations at Microsoft did nothing to stop the bullying, either.

“Rather than do the right thing, the management team went after Michael by getting a female employee to file a sexual harassment complaint and a complaint of retaliation against him,” says Paul T. Morin. “Microsoft could have taken Mercieca’s charges seriously and disciplined the senior manager but instead it engaged in the worst kind of corporate bullying.”

Read the full story

King Soopers to Pay $80,000 to Settle EEOC Disability Discrimination Lawsuit

DENVER, CO – Dillon Companies, Inc., owners of the King Soopers supermarket chain in Colorado will pay $80,000 for bullying a learning-disabled employee who worked at its Lakewood, Colorado store.

According to the EEOC’s disability discrimination lawsuit, two store supervisors repeatedly subjected Justin Stringer, an employee who worked at King Soopers for a decade, to repeated bullying and taunting in the workplace because of his learning disability. The EEOC alleged that the bullying resulted in Stringer’s termination.

“Employees with disabilities must be treated with the same dignity and respect as all other members of the work force,” said EEOC Regional Attorney Mary Jo O’Neill. “The EEOC will continue to enforce the ADA to protect the rights of disabled employees and applicants.”

DHL Global Forwarding Pays $201,000 to Settle EEOC National Origin Discrimination Suit

DALLAS, TX – Air Express International, USA, Inc. and Danzas Corporation, doing business as DHL Global Forwarding, will pay $201,000 to nine employees and provide other significant relief to settle a national origin hostile environment lawsuit brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

The EEOC charged DHL Global with subjecting a class of Hispanic employees to bullying, discrimination, and harassment due to their national origin. According to the suit, Hispanic employees at DHL’s Dallas warehouse were bullied at work by being subjected to taunts and derogatory names such as “wetback,” “beaner,” “stupid Mexican” and “Puerto Rican b-h”. The Hispanic workers, who included persons of Mexican, Salvadoran and Puerto Rican heritage, were often ridiculed by DHL personnel with demeaning slurs which included referring to the Salvadoran worker as a “salvatrucha,” a term referring to a gangster. Other workers were identified with other derogatory stereotypes.

Robert A. Canino, regional attorney for the EEOC’s Dallas District Office, stated, “Bullying Hispanic workers for speaking a language other than English is a distinct form of discrimination, which, when coupled with ethnic slurs, is clearly motivated by prejudice and national origin animus. Sometimes job discrimination isn’t just about hiring, firing or promotion; it’s about an employer promoting disharmony and disrespect through an unhealthy work environment.”

Wal-Mart to Pay $150,000 to Settle EEOC Age and Disability Discrimination Suit

DALLAS, TX – Wal-Mart Stores of Texas, L.L.C. (Wal-Mart) has agreed to pay $150,000 and provide other significant relief to settle an age and disability discrimination lawsuit brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The EEOC charged in its suit that Wal-Mart discriminated against the manager of the Keller, Texas Walmart store by subjecting him to bullying, harassment, discriminatory treatment, and discharge because of his age.

According to the EEOC, David Moorman was ridiculed with frequent bullying and taunts at work from his direct supervisor, including being called “old man” and “old food guy.” The EEOC also alleged that Wal-Mart fired Moorman because of his age.

“Mr. Moorman was subjected to taunts and bullying from his supervisor that made his working conditions intolerable,” said EEOC Senior Trial Attorney Joel Clark. “The EEOC remains committed to prosecuting the rights of workers through litigation in federal court.”

Under the terms of the two-year consent decree settling the case, Wal-Mart will pay $150,000 in relief to Moorman under the terms of the two-year consent decree. Wal-Mart also agreed to provide training for employees on the ADA and the ADEA, which will include an instruction on the kind of conduct that could constitute unlawful discrimination or harassment.

Everyone deserves to work in a safe, supportive environment and workplace bullies should be dealt with accordingly. If you are being bullied at work, contact our expert California employment lawyers today for your free consultation.

Recent Posts

Schedule a free case evaluation.

Fields Marked With An * Are Required

Do you agree to receive text messages from Hennig Kramer Ruiz & Singh LLP?

more than 25 years of experience

Trusted counsel when you need it most.

- Practice Areas

Local Office

3600 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 1908 Los Angeles, CA 90010

Copyright © 2024 Hennig Kramer Ruiz & Singh, LLP . All rights reserved.

An official website of the United States government.

Here’s how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- 中文(简体) (Chinese-Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese-Traditional)

- Kreyòl ayisyen (Haitian Creole)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- Español (Spanish)

- Filipino/Tagalog

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Safety and Health Topics

Workplace Violence

- Workplace Violence Home

Risk Factors

Prevention programs.

- Training & Other Resources

Enforcement

- Workers' Rights

- Enforcement Procedures and Scheduling for Occupational Exposure to Workplace Violence . OSHA Directive CPL 02-01-058, (January 10, 2017).

- Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers ( EPUB | MOBI ). OSHA Publication 3148, (2016).

- Worker Safety in Hospitals: Caring for our Caregivers, Preventing Workplace Violence in Healthcare . OSHA.

- Taxi Drivers – How to Prevent Robbery and Violence . OSHA Publication 3976 (DHHS/NIOSH Publication No. 2020-100), (November 2019).

- Recommendations for Workplace Violence Prevention Programs in Late-Night Retail Establishments . OSHA Publication 3153, (2009).

This workplace violence website provides information on the extent of violence in the workplace, assessing the hazards in different settings and developing workplace violence prevention plans for individual worksites.

What is workplace violence?

Workplace violence is any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the work site. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults and even homicide. It can affect and involve employees, clients, customers and visitors. Acts of violence and other injuries is currently the third-leading cause of fatal occupational injuries in the United States. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI), of the 5,333 fatal workplace injuries that occurred in the United States in 2019, 761 were cases of intentional injury by another person. [ More... ] However it manifests itself, workplace violence is a major concern for employers and employees nationwide.

Who is at risk of workplace violence?

Many American workers report having been victims of workplace violence each year. Unfortunately, many more cases go unreported. Research has identified factors that may increase the risk of violence for some workers at certain worksites. Such factors include exchanging money with the public and working with volatile, unstable people. Working alone or in isolated areas may also contribute to the potential for violence. Providing services and care, and working where alcohol is served may also impact the likelihood of violence. Additionally, time of day and location of work, such as working late at night or in areas with high crime rates, are also risk factors that should be considered when addressing issues of workplace violence. Among those with higher-risk are workers who exchange money with the public, delivery drivers, healthcare professionals, public service workers, customer service agents, law enforcement personnel, and those who work alone or in small groups.

How can workplace violence hazards be reduced?

In most workplaces where risk factors can be identified, the risk of assault can be prevented or minimized if employers take appropriate precautions. One of the best protections employers can offer their workers is to establish a zero-tolerance policy toward workplace violence. This policy should cover all workers, patients, clients, visitors, contractors, and anyone else who may come in contact with company personnel.

By assessing their worksites, employers can identify methods for reducing the likelihood of incidents occurring. OSHA believes that a well-written and implemented workplace violence prevention program, combined with engineering controls, administrative controls and training can reduce the incidence of workplace violence in both the private sector and federal workplaces.

This can be a separate workplace violence prevention program or can be incorporated into a safety and health program, employee handbook, or manual of standard operating procedures. It is critical to ensure that all workers know the policy and understand that all claims of workplace violence will be investigated and remedied promptly. In addition, OSHA encourages employers to develop additional methods as necessary to protect employees in high risk industries.

Provides information on risk factors and scope of violence in the workplace to increase awareness of workplace violence.

Provides guidance for evaluating and controlling violence in the workplace.

Training and Other Resources

Provides online training and other resource information.

There are currently no specific OSHA standards for workplace violence. Also provides links to enforcement letters of interpretation.

- Open access

- Published: 03 October 2023

Healthcare workers’ experiences of workplace violence: a qualitative study in Lebanon

- Linda Abou-Abbas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9185-3831 1 ,

- Rana Nasrallah 2 ,

- Sally Yaacoub ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0819-1561 1 , 3 ,

- Jessica Yohana Ramirez Mendoza 4 &

- Mahmoud Al Wais ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0007-6138-1184 1

Conflict and Health volume 17 , Article number: 45 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought unprecedented challenges to healthcare workers (HCWs) around the world. The healthcare system in Lebanon was already under pressure due to economic instability and political unrest before the pandemic. This study aims to explore the impact of COVID-19 and the economic crisis on HCWs’ experiences of workplace violence in Lebanon.

A qualitative research design with an inductive approach was employed to gather data on workplace violence through Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) from HCWs in Tripoli Governmental Hospital (TGH), a governmental hospital in North Lebanon. Participants were recruited through purposive sampling. The interviews were conducted in Arabic, recorded, transcribed, and translated into English. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data.

A total of 27 employees at the hospital participated in the six FGDs, of which 15 females and 12 males. The analysis identified four main themes: (1) Types of violence, (2) Events witnessed, (3) Staff reactions to violence, and (4) Causes of violence. According to the interviews conducted, all the staff members, whether they had experienced or witnessed violent behavior, reported that such incidents occurred frequently, ranging from verbal abuse to physical assault, and sometimes even involving the use of weapons. The study findings suggest that several factors contribute to the prevalence of violence in TGH, including patients’ financial status, cultural beliefs, and lack of medical knowledge. The hospital’s location in an area with a culture of nepotism and favoritism further exacerbates the issue. The staff’s collective response to dealing with violence is either to submit to the aggressor’s demands or to remove themselves from the situation by running away. Participants reported an increase in workplace violence during the COVID-19 pandemic and the exacerbated economic crisis in Lebanon and the pandemic.

Interventions at different levels, such as logistical, policy, and education interventions, can help prevent and address workplace violence. Community-level interventions, such as raising awareness and engaging with non-state armed groups, are also essential to promoting a culture of respect and zero tolerance for violence.

Introduction

Acts of violence in the workplace have far-reaching consequences that can disrupt various aspects of society [ 1 ]. Healthcare workers (HCWs) are often at a higher risk of being subjected to workplace violence, with up to 38% of HCWs experiencing violence at some point during their careers [ 2 ]. The prevalence of workplace violence (WPV) against HCWs was found to be high in Asian and North American countries, psychiatric and emergency department settings, and among nurses and physicians [ 3 ].

The COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated violence against HCWs [ 4 , 5 , 6 ], increasing existing sources of violence and opening new areas of confrontation between healthcare providers, patients, and their families [ 5 ]. From February to December 2020, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) received 848 reports of violence against HCWs related to COVID-19 across 42 countries. These incidents occurred in various regions around the world, including Europe, Africa, the Americas, and Asia [ 7 ]. A review of incidents from a lower-middle-income country revealed that the reasons for the assaults are varied, including unexpected outcomes or death of a patient, unavailability of resources at the hospital due to overcrowding, miscommunication, and a lack of awareness in society [ 8 ].

A joint study by several international organizations has found that violence against doctors is widespread and has increased since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 5 ]. The study received responses from over 120 organizations and found that 58% of respondents perceived an increase in violence, with all respondents reporting verbal aggression, 82% mentioning threats and physical aggression, and 27% reporting staff being threatened by weapons [ 5 ]. The study highlights the need for concrete action to end impunity for those who are violent and suggests practical solutions, such as improving relations between health personnel and patients and implementing successful strategies from countries such as Bulgaria, Colombia, Italy, Portugal, and Taiwan. The study highlights the need to better understand how violence is affecting healthcare workforce and quality of services and take action to stop it [ 5 ].

WPV is a serious issue in Lebanon, and the healthcare sector is not immune to this problem. A study conducted in 2015 found that 62% of nurses in Lebanon experienced verbal abuse in the past year, while 10% reported physical abuse, including weapon attacks [ 9 ]. The economic crisis in Lebanon, combined with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic for the past three years, has resulted in an increase in violent acts against HCWs, with hospitals becoming a target for frustrated individuals [ 10 ]. The situation is particularly challenging for Tripoli Governmental Hospital (TGH), which is the second largest public hospital in Lebanon where citizens suffer from low incomes and poverty. Its location is critical, as many armed clashes/hostilities take place in the surrounding area of the hospital, making it more vulnerable to workplace violence [ 11 ]. As HCWs play a critical role in providing essential services to the community and deserve to work in a safe and supportive environment, it is crucial to address the issue of workplace violence and gain a deeper understanding of the issues surrounding violence against healthcare providers in TGH. This study aims to understand HCWs’ perspectives on workplace violence, explore their preferences for interventions to prevent violence, and propose feasible methods to protect HCWs from violence. This research could be a crucial step towards improving the safety and well-being of HCWs in Lebanon and other similar settings.

Study design and setting

A qualitative research design with an inductive approach was employed to gather data on WPV through Focus Group Discussions (FGDs). The decision to initiate the research with FGDs rather than individual interviews was due to several factors including resource availability, research objectives, and the nature of the research question. Starting directly with FGDs was deemed efficient in terms of time and resources, especially when seeking a broader understanding of WPV by facilitating group interactions that stimulate participants to build on each other’s ideas and experiences. Additionally, FGDs can create an environment where participants feel more comfortable sharing sensitive or personal experiences due to the shared context and the support of the group.

The study was conducted at TGH that serves about 638,000 Lebanese (including 244,000 residents of Tripoli), 233,000 Syrian refugees, and roughly 50,000 Palestinian refugees. Approximately 400 healthcare providers (doctors and nurses) work at TGH [ 11 ].

Participant recruitment

To ensure a diverse range of participants based on gender and occupations, we implemented a purposeful sampling procedure. This procedure involved contacting various categories of hospital staff and inviting them to participate in our study. Eligibility was extended to all staff members working within the hospital setting. Invitations to participate were conveyed through phone messages. Staff members who expressed their willingness to participate were subsequently contacted via phone messages to arrange the interview. Additionally, we meticulously planned the FGDs by predetermining the date, time, and location.

Our selection criteria focused mainly on individuals in direct contact with patients due to their unique vantage points and daily exposure to WP incidents providing firsthand perspectives on frontline dynamics. Additionally, administrative and support staff were included to contribute valuable insights into organizational aspects related to workplace violence, enriching our understanding of the broader context within healthcare organizations. These categories were considered most appropriate for our research, as they align closely with our research objectives, allowing us to gain comprehensive insights into WP in the healthcare setting.

The hospital staff who agreed to participate in the study were grouped according to their preferred time during the day.

Four FGDs were conducted for the study, as follows:

A group of female nurses.

Two groups of both female and male nurses.

A group of hospital administrative staff.

Two groups of other support staff including orderlies, lab technicians, cooks, housekeeping.

Data collection

In February 2022, the FGDs were conducted by two investigators in Arabic in a private room at the hospital using a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1). Only non-identifiable information was collected and included gender and the participants’ job title (i.e., physician, nurse, paramedic). The interview guide included open-ended questions related to WPV, such as how it is defined, the forms it takes, examples of violent incidents, and the motives of perpetrators. Other questions included the staff’s reaction to the incidents and whether they could have reacted differently or prevented the event from happening. Training of HCWs, preventing violence, and hospital safety regulations were also discussed. The interviews lasted 45 min to an hour on average.

As we progressed through the study, we observed that new information and perspectives related to workplace violence became increasingly scarce. Instead, we encountered recurring themes and insights from participants, indicating that we had comprehensively explored the topic. This consistent repetition of information across participants signaled to us that we had achieved data saturation, where further data collection would likely yield diminishing returns in terms of new insights.

Data gathering tool

The discussions were audio recorded as a means of capturing participants’ voices, experiences, and perspectives in their own words during the FGDs. Following the transcription, the original recordings were securely destroyed to uphold participants’ privacy and ensure the confidentiality of the information shared. This approach aligned with best practices in qualitative research to protect participants’ identities and uphold the integrity of the research process.

Quality control and assurance

The research team rigorously ensured objectivity and impartiality in the formulation of research questions. Questions posed during interviews were deliberately crafted to be objective, avoiding any form of intervention or bias. The primary goal was to explore diverse dimensions of workplace violence and gather information essential for the study. Crucially, the interviewers maintained a neutral stance, refraining from expressing personal opinions or influencing participant responses. Importantly, no pre-existing relationships existed between the interviewers and participants, reinforcing the integrity of the research process. Data collection was conducted in a room within the hospital premises, selected for its convenience. This choice accommodated the participation of hospital staff during their work shifts, facilitating their engagement in the study. All staff members within the hospital, irrespective of their roles, were eligible to participate due to their direct interactions with patients, which made their perspectives valuable to the research objectives. The selection of participants was unbiased, guided solely by their roles in patient care and their exposure to workplace violence incidents.

Ethical considerations

The approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at American University of Beirut (AUB) (SBS-2021-0352) and the internal ethical review board at ICRC was obtained before starting the study (2109-APR). The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles and guidelines, including informed consent, confidentiality, and the right to withdraw from the study at any time. The participants signed an informed consent form before the discussion, which emphasized the confidentiality of the information they shared. They were also informed that they could withdraw from participating in the study at any time.

Data analysis

Audio-recorded FGDs were transcribed verbatim in the Arabic language. A rigorous manual analysis was undertaken to discern recurring themes, patterns, and insights pertaining to WPV experiences among HCWs. The verbatim transcripts were meticulously reviewed to extract pertinent concepts and phrases, which were then assigned as codes. These codes were subsequently organized into categories within a matrix structure. These categories aligned with overarching themes that were deduced from the research objectives and questions, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of WPV dimensions. The themes and sub-themes identified underwent thorough discussion within the research team to ensure accuracy and robustness. Quotes used in reporting findings were translated to English language.

A total of 27 employees at the hospital participated in the six FGDs, of which 15 females and 12 males. The participants were further categorized into three groups based on their occupations: nurses (14 participants), administrative staff (5 participants), and support staff (8 participants).

The analysis of the information gathered was conducted through a process of coding, sub-theme, and theme development. The coding scheme can be found in Table 1 .

In the following paragraphs, each theme is described in more detail providing sample quotes, where appropriate.

Types of violence

All participants unanimously agreed that any form of aggression experienced while performing their jobs in healthcare settings constitutes violence. This indicates a clear consensus among the participants regarding the definition of violence in the healthcare setting.

Based on the participants’ descriptions, the types of violence experienced in healthcare settings can be categorized into two main forms: verbal and physical. Verbal violence included any communication that is intended to harm or intimidate, such as shouting, swearing, or making derogatory remarks. Physical violence, on the other hand, included any intentional physical act that causes harm or injury, such as hitting, kicking, or pushing. Some participants also mentioned the potential for nonverbal or subtle forms of violence, such as body language or tone of voice, which can convey aggression or hostility. Additionally, some participants identified the use of weapons or threats as a form of violence. While most of the participants focused on the violence that they can face from the patients and their families, some mentioned that violence can be addressed from their colleagues as well. Moreover, it was acknowledged that violence in healthcare settings can also originate from staff members towards their patients.

Events witnessed

All staff members have witnessed violence at work that ranged from verbal abuse such as being threatened, shouted at, and being cursed, to being punched or slapped and sometimes even physical injury in the form of bone fractures. It is important to note that the type of violence targeting males and females differed. Males were more likely to experience physical violence. In contrast, females were often targeted with verbal abuse, though they were not immune to physical violence either. Additionally, weapons were brought into the hospital and used against the staff, further exacerbating the risk and harm faced by everyone involved.

A nurse that was working in the Emergency Department (ED) was present during an event when a family member of a patient who was seeking care for a stabbing injury in the back was threatening to blow the ED with a bomb if his relative would have died or “ does not leave the hospital walking on his legs ”. He even shot the roof of the ED with the weapon he was holding.

The participant verbalized the following words:

“ It was one of the scariest moments of my life… my colleague and I had to help the bleeding patient, but we were hiding afraid to die… If my parents knew what I went through that day, they would have not allowed me to go to work again ”.

Another participant described being punched in the face by someone who came to the blood bank asking for O negative blood units. The lab technician ended up giving him a unit of blood from any type due to his fear. He mentioned:

In times like that, all you think about is how to save yourself, your life, so that you remain available next to your family… .

Almost half of the participants recalled a recent event experienced by a nurse at the Obstetrics and Gynecology (OBGYN) unit. The family members of a patient broke the fingers of the nurse for not being able to insert an IV line directly to the patient.

Administrative staff have also been subject to violence with four out of five having experienced violent episodes. The violence they encounter is primarily in the form of shouting and damage to the health facility and equipment causing destruction of glass and equipment in their vicinity.

“ We’re used to this kind of violence, we face it daily ”, they said.

Violence has been observed by staff across all categories, including those who do not have direct contact with patients and their families. For example, a cook working in the hospital’s kitchen was shouted at by a patient’s family member for not providing food, even though the patient was under medical orders not to eat due to a recent surgical operation. Additionally, a pharmacist was threatened with physical harm in the pharmacy department if they did not provide narcotics to an aggressive individual.

Some participants mentioned that verbal aggression between staff members may occur, but they are usually resolved immediately without further escalation. Additionally, one participant noted that in some cases, staff members may raise their voices and behave inappropriately towards patients and their families, which could be attributed to the high levels of stress they are experiencing.

“ We are all stressed, sometimes we shout at patients’ families or our colleagues due to the stress we are enduring inside and outside the hospital environment ”.

Causes of violence

Staff reported the causes that could potentially lead to violent incidents in hospitals which can generally be divided into two categories: hospital-related and patient-related.

Hospital-related

One of the main causes that staff members at the hospital cited for potential violence was the inadequate number of security guards. With only two guards stationed at the entrance of the hospital, there was concern that they would not be able to effectively respond to any violent incidents that might occur. Additionally, even though at the hospital’s parking premises there is an army checkpoint; they are not authorized to intervene in such situations, further exacerbating the security issue.

Another reason mentioned by the administrative staff was the laborious and protracted billing procedure for outpatients. To bill the patients, the paperwork needs to be physically transported across several departments, such as pharmacy, laboratory, and imaging, which is a manual process. This process is time-consuming which adds frustration to the patient and his family and can sometimes escalate into violence.

The lack of a clear visitation policy was also a concern raised by nurses at the hospital. Without clear restrictions on who can visit patients and when, anyone can enter the hospital at any time, including individuals who may be carrying weapons.

Patient-related

According to the TGH staff, the main reason of violence in the hospital is attributed to the financial status of the patients. As a public hospital, many patients expect to receive free treatment. However, when informed of the costs associated with their care by the admitting department, they become overwhelmed and agitated, which can escalate to violent behavior. Additionally, the hospital’s location in an area with a culture of favoritism contributes to some patients’ belief that they can obtain special treatment by shouting and threatening, which may also contribute to incidents of violence in the hospital.

One of the staff said that “ the clients of the hospital know that if they shout and threaten, they will get whatever they want ”.

The insufficient medical knowledge of patients and their families is identified by almost all participants as a significant factor contributing to violence in TGH. Due to their limited understanding of the disease, patients and their families have unrealistic expectations of the healthcare staff’s ability to maintain the patient’s life, which can escalate to violent conduct. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened this situation, as participants noted that the lack of comprehension of this novel disease has also played a role in violent incidents.

“ Families and patients do not understand why they cannot see their relative at isolation, and that makes them aggressive ”.

Staff reactions to violence

The staff collectively agreed that the best way to deal with violence is to either submit to the aggressor’s demands to avoid being subjected to violence or to physically remove themselves from the situation by running away. Two nurses working at the pharmacy department described how nurses from the Obstetrics and Gynecology department ran away from their unit to the pharmacy department when they were aggressed by a patient’s family.

Staff members in hospitals often avoid reacting or intervening in violent situations due to their fear of not only being attacked at work but also being followed and harassed on their way to and from work, as they mentioned:

“ In these situations, we just need to protect ourselves… we agree with whatever the aggressor says and do whatever he asks for ”.

The response to violence differs between males and females. Males tend to face the perpetrator and confront them directly, possibly reflecting societal expectations of male protectiveness or assertiveness. In contrast, females tend to prioritize escape and avoidance, preferring not to engage with the perpetrators directly. They may even respond to the perpetrators’ needs, even if those needs are not relevant or urgent, as a means of defusing the situation. Some female staff members mentioned that when a perpetrator attacks the nursing station or arrives angry at a department, their aggression often subsides upon realizing that the entire staff present is female. This observation suggests that the gender composition of the staff can have an impact on the dynamics of the situation, potentially leading to a de-escalation of the aggression.

In cases of violence, staff members seek assistance by calling the few available security guards at the hospital or asking for help from the police, recognizing the importance of external support in managing violent incidents and ensuring the safety of all involved parties.

The study conducted sheds light on the alarming issue of violence against HCWs in TGH. According to the interviews conducted, all the staff members, whether they had experienced or witnessed violent behavior, reported that such incidents occurred frequently, ranging from verbal abuse to physical assault, and sometimes even involving the use of weapons. The study findings suggest that several factors contribute to the prevalence of violence in TGH, including patients’ financial status, cultural beliefs, and lack of medical knowledge. The hospital’s location in an area with a culture of clout and favoritism further exacerbates the issue. The staff’s collective response to dealing with violence is either to submit to the aggressor’s demands or to remove themselves from the situation by running away. In this discussion section, we will examine the implications of these findings and propose recommendations to address this problem.

Our findings are consistent with a recent meta-analysis of 38 studies involving 63,672 healthcare workers (HCWs), which reported high prevalence rates of workplace violence (WPV) among HCWs. The analysis revealed significant rates of physical violence (9%), verbal violence (48%), and emotional violence (26%) among HCWs. Furthermore, the meta-analysis indicated an escalation of WPV, physical violence, and verbal violence during the mid- to late-stages of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 12 ]. These findings emphasize the critical need to address WPV and prioritize the well-being and safety of HCWs. The patients’ financial status appears to be a significant contributor to violent behavior, as many patients expect to receive free treatment at TGH, being a public hospital. However, they become agitated when informed of the costs associated with their care, which can escalate to violent conduct. The cultural beliefs and attitudes of patients towards the hospital staff also play a role in the occurrence of violence. Patients who believe that shouting and threatening will give them preferential treatment may become violent when their expectations are not met. The lack of medical knowledge among patients and their families is also a significant factor contributing to violent behavior. Patients and their families may have unrealistic expectations of the healthcare staff’s ability to maintain the patient’s life due to their limited understanding of the disease. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the issue of violence in the hospital, with participants reporting that the lack of knowledge about the new disease has contributed to violent incidents. Working with people infected with COVID-19 is also a factor for violence [ 6 ]. The weakness of the security logistics at the hospital has also been a major reason for violence. The issues of corruption in Lebanon have also affected violence in the TGH. Many participants mentioned that people who commit violence against HCWs at the hospitals are usually covered by political parties. They threat with weapons and use them in the hospital knowing that eventually, there will be no punishment for their actions. The fact that TGH is a public hospital makes it a “punching bag” for the Lebanese patients that are frustrated from the Lebanese Government, so they pour their anger against the corrupted system in Lebanon on the healthcare workers at the hospital.

Differences were observed between males and females in terms of the types of violent incidents witnessed and the corresponding reactions exhibited. Males are more likely to witness and experience physical violence, such as being punched, slapped, or sustaining physical injuries. This could be attributed to societal expectations of male dominance and the perceived need for physical confrontation. On the other hand, females are more likely to encounter verbal abuse and emotional violence. When faced with violence, males tend to confront the perpetrators directly, possibly driven by societal norms of masculinity and the desire to protect themselves or others. In contrast, females often prioritize their safety by opting for escape and avoiding direct confrontation. They may comply with the aggressor’s demands to de-escalate the situation or minimize the risk of harm. These gender-specific responses may be influenced by social conditioning and self-preservation instincts, highlighting the complex interplay between societal expectations, gender roles, and individual coping mechanisms in the face of violence. However, it is important to note that these findings should not overshadow the fact that violence can affect individuals of all genders and that the experiences of individuals may vary widely. Each case should be considered on its own merits, and it is crucial to avoid making broad generalizations based solely on gender. Addressing violence requires comprehensive efforts that focus on prevention, support for survivors, and challenging harmful societal norms and behaviors.

It’s important to note that not all HCWs initially approached for participation in our study agreed to participate to the study. Possible reasons are unavailability during the study period or may be concerns related to the sensitivity of the topic, given that workplace violence is a complex and sensitive issue. We recognize that their non-participation introduces certain limitations and potential biases as their perspectives and experiences, which could have enriched our findings, are not represented. Consequently, we have taken great care to accurately present the data collected from willing participants in a manner that faithfully reflects their experiences within the study’s scope.

Interventions should be implemented promptly to enhance the security measures in hospitals, given the severity of the issue of violence against staff members. To improve security measures at hospitals, various interventions can be implemented at the organizational level. Logistical interventions, policy initiation interventions, and staff education can help prevent workplace violence. One effective logistical intervention is to install metal doors with access restricted to staff ID cards at hospital entrances and unit doors. Additionally, increasing the number of security guards and placing at least one guard on each hospital floor can help limit the number of visitors and prevent unwanted access. Metal detectors at the main entrance can also help prevent visitors from entering the hospital with weapons. At the policy level, visitation restrictions can be implemented, such as limiting visits to two family members per patient. Staff education and training programs can be conducted to prevent and manage workplace violence. Research has shown that staff training for violence prevention and management can reduce the consequences of violence [ 13 ]. Healthcare organizations, policymakers, and the government should work together to implement these interventions to ensure that healthcare workers can provide care safely and without fear of violence. Staff have shown willingness to participate in such training during focus group discussions.

At the community level, raising awareness among the adjacent population about the importance of respecting the hospital’s facilities and staff is one such intervention. This can help the community understand the crucial role of healthcare workers in treating and preventing diseases and promote their protection instead of violation. Another important intervention is to engage with non-State armed groups in the area to prevent violence against healthcare workers. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has set an example in 2014 by counseling and meeting with them and signing an agreement to avoid interfering in the hospital’s work and protecting healthcare workers [ 7 ]. These interventions involve all stakeholders in the problem and have shown positive impacts in reducing violence against healthcare workers in recent studies [ 13 ].

Violence against healthcare workers is a critical issue that affects the quality of healthcare services and the safety of both HCWs and patients. Our findings, derived from the perspectives of healthcare workers (HCWs), suggest that the problem of violence against HCWs is multifaceted, with various factors contributing to its occurrence. These factors include patient-related, organizational, and community-related factors. Interventions at different levels, such as logistical, policy, and education interventions, can help prevent and address workplace violence. Community-level interventions, such as raising awareness and engaging with non-state armed groups, are also essential to promoting a culture of respect and zero tolerance for violence. It is crucial for all stakeholders, including healthcare organizations, policymakers, the government, and the community, to work together to implement these interventions to ensure that healthcare workers can provide care safely and without fear of violence or harm.

The authors confirm that the views and opinions expressed in this publication do not in any way constitute the official view or position of the ICRC. Every effort has been made to comply with our duties of discretion regarding activities undertaken during our employment/missions with the ICRC.

Data Availability

The data collected for this qualitative study is not publicly available due to the confidential nature of the information shared by participants. Access to the data is restricted to the research team to maintain privacy and ensure compliance with ethical guidelines.

Abbreviations

Coronavirus disease-2019

Health care workers

Focus group discussion

Tripoli Governmental Hospital

International Committee of the Red Cross

- Workplace violence

Liu J, et al. Workplace violence against nurses, job satisfaction, burnout, and patient safety in chinese hospitals. Nurs Outlook. 2019;67(5):558–66.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

WHO, World Health Organization., Preventing violence against health workers, available: https://www.who.int/activities/preventing-violence-against-health-workers . 2022.

Liu J, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(12):927–37.

Elsaid NMAB, et al. Violence against healthcare workers during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Egypt: a cross-sectional study. Egypt J Forensic Sci. 2022;12(1):45.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Thornton J. Violence against health workers rises during COVID-19. The Lancet. 2022;400(10349):348.

Article Google Scholar

Bitencourt MR, et al. Predictors of violence against health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0253398.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

ICRC, International Committee of the Red Cross., COVID-19 Special, Available: https:// healthcareindanger.org/covid-19-special/?__hstc=246532443.c138db4f20418b575032677d21f6d14a.1669035781842 .1669040887977.1679927932677.3&__hssc=246532443.1.1679927932677&__hsfp=1617094012. 2020.

Bhatti OA, et al. Violence against Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of incidents from a Lower-Middle-Income Country. Annals of Global Health. 2021;87(1):41–1.

Alameddine M, Mourad Y, Dimassi H. A National Study on Nurses’ exposure to Occupational Violence in Lebanon: prevalence, Consequences and Associated factors. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0137105–5.

Fleifel M, Abi Farraj K. The lebanese Healthcare Crisis: an infinite calamity. Cureus. 2022;14(5):e25367–7.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

AFD, Reinforcing the provision of care at Tripoli Governmental Hospital (TGH.), available: https://www.afd.fr/en/carte-des-projets/lebanon-reinforcing-provision-care-tripoli-governmental-hospital . 2022.

Zhang S et al. Workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2023: p. 1–15.

Bellizzi S, et al. Violence against Healthcare: a Public Health Issue beyond Conflict Settings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;106(1):15–6.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the TGH who consented to participate in this study and for sharing their stories during such troubled times in Lebanon. We also thank the nursing director who helped with the recruitment and logistics.

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Beirut, Lebanon

Linda Abou-Abbas, Sally Yaacoub & Mahmoud Al Wais

American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

Rana Nasrallah

Université Paris Cité and Université Sorbonne Paris Nord, Inserm, INRAE, Center for Research in Epidemiology and Statistics (CRESS), Paris, France

Sally Yaacoub

International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, Switzerland

Jessica Yohana Ramirez Mendoza

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MAW and SY conceived the study idea and designed the study protocol. RN and SY conducted the interviews. RN conducted the transcription, translation, and drafted the manuscript. LAA contributed to the qualitative analysis of the data and assisted with editing the article. JM reviewed the article for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version submitted.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mahmoud Al Wais .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the American University of Beirut (AUB) and the internal ethical review board at ICRC (DP_DIR 21/14 - FTY/abg). Informed consent was obtained from participants, who were assured of confidentiality, the right to withdraw, and the destruction of audio recordings after transcription.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Interview Topic guide .

Introduce yourself, provide the consent form .

Collect Demographic information: Gender & job title .

Workplace Violence .

How do you define occupational violence (i.e., workplace violence)? In what forms does it occur? Can you give examples from your experience (whether you witnessed violence or got exposed to it)?

Have you ever been exposed to violence at work/healthcare setting?

Why do you think such aggressive incidents take place? What are the motives of the perpetrator?

How did you react to the incidents that you got exposed to or witnessed? And do you think you could have reacted differently or maybe prevented the event from happening?

Do you think training of healthcare workers in communication/counseling skills, training in managing violence … would help prevent violent incidents?

Do you think it would be useful to increase resources in combating violence; specifically, by increasing security personal and facilities, working conditions and incentives for healthcare workers, and adequate facilities (equipment/medicines/ healthcare workers)?

What rules and regulations are needed to ensure that the environment is safe at the hospital?

How willing are you to engage in specific programs to combat violence? Why are you encouraged and why not?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Abou-Abbas, L., Nasrallah, R., Yaacoub, S. et al. Healthcare workers’ experiences of workplace violence: a qualitative study in Lebanon. Confl Health 17 , 45 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-023-00540-x

Download citation

Received : 19 June 2023

Accepted : 15 September 2023

Published : 03 October 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-023-00540-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Healthcare workers

- Qualitative study

Conflict and Health

ISSN: 1752-1505

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 13 October 2023

Contemporary evidence of workplace violence against the primary healthcare workforce worldwide: a systematic review

- Hanizah Mohd Yusoff 1 ,

- Hanis Ahmad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6657-8698 1 ,

- Halim Ismail 1 ,

- Naiemy Reffin 1 ,

- David Chan 1 ,

- Faridah Kusnin 2 ,

- Nazaruddin Bahari 2 ,

- Hafiz Baharudin 1 ,

- Azila Aris 1 ,

- Huam Zhe Shen 1 &

- Maisarah Abdul Rahman 3

Human Resources for Health volume 21 , Article number: 82 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Violence against healthcare workers recently became a growing public health concern and has been intensively investigated, particularly in the tertiary setting. Nevertheless, little is known of workplace violence against healthcare workers in the primary setting. Given the nature of primary healthcare, which delivers essential healthcare services to the community, many primary healthcare workers are vulnerable to violent events. Since the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978, the number of epidemiological studies on workplace violence against primary healthcare workers has increased globally. Nevertheless, a comprehensive review summarising the significant results from previous studies has not been published. Thus, this systematic review was conducted to collect and analyse recent evidence from previous workplace violence studies in primary healthcare settings. Eligible articles published in 2013–2023 were searched from the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed literature databases. Of 23 included studies, 16 were quantitative, four were qualitative, and three were mixed method. The extracted information was analysed and grouped into four main themes: prevalence and typology, predisposing factors, implications, and coping mechanisms or preventive measures. The prevalence of violence ranged from 45.6% to 90%. The most commonly reported form of violence was verbal abuse (46.9–90.3%), while the least commonly reported was sexual assault (2–17%). Most primary healthcare workers were at higher risk of patient- and family-perpetrated violence (Type II). Three sub-themes of predisposing factors were identified: individual factors (victims’ and perpetrators’ characteristics), community or geographical factors, and workplace factors. There were considerable negative consequences of violence on both the victims and organisations. Under-reporting remained the key issue, which was mainly due to the negative perception of the effectiveness of existing workplace policies for managing violence. Workplace violence is a complex issue that indicates a need for more serious consideration of a resolution on par with that in other healthcare settings. Several research gaps and limitations require additional rigorous analytical and interventional research. Information pertaining to violent events must be comprehensively collected to delineate the complete scope of the issue and formulate prevention strategies based on potentially modifiable risk factors to minimise the negative implications caused by workplace violence.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Events where healthcare workers (HCWs) are attacked, threatened, or abused during work-related situations and that present a direct or indirect threat to their security and well-being are referred to as workplace violence (WPV) [ 1 ]. Violence in the health sector has increased over the last decade and is a primary global concern [ 2 ]. Recent statistical data demonstrated that HCWs were five times more likely to experience violence than workers in other sectors and are involved in 73% of all nonfatal violent work incidents [ 3 ]. The experience of WPV is linked to reduced quality of life and negative psychological implications, such as low self-esteem, increased anxiety, and stress [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. WPV is often linked to poor work performance caused by lower job satisfaction, higher absenteeism, and reduced worker retention [ 7 , 8 ], which may disrupt patient care quality and other healthcare service productivity [ 9 ]. Decision-makers and academics worldwide now recognise the seriousness of WPV in the health sector, which has been extensively examined in tertiary settings, particularly emergency and psychiatric departments. Nonetheless, understanding of WPV in primary healthcare (PHC) settings is minimal.

The modern health system has experienced a fundamental shift in delivery systems while moving towards universal health coverage and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [ 7 ]. Despite the focus on tertiary-level individual disease management, the healthcare system recently moved towards empowering primary-level patient and community health needs [ 10 ]. Robust PHC system delivery provides deinstitutionalised patient care, which includes health promotion, acute disease management, rehabilitation, and palliative services, via primary health units in the community, which are referred to with different terms across countries, such as family health units, family medicine and community centres, and outpatient physician clinics [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. In developing and developed countries, PHC services are associated with improved accessibility, improved health conditions, reduced hospitalisation rates, and fewer emergency department visits [ 14 ]. The backbone of this health system delivery is a PHC team of family physicians, physician assistants, nurses, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, social workers, administrative staff, auxiliaries, and community workers [ 15 ].

Nevertheless, the nature of PHC service, which delivers essential services to the community, requires direct interaction with patients and family members, thus increasing the likelihood of experiencing violent behaviour [ 10 ]. Understaffing occurs mainly due to the lack of comprehensive national data that could offer a complete view of the PHC workforce constitution and distribution, which results in increased responsibilities and compromised patient communication [ 15 ]. Considering the current worldwide employment patterns, a shortage of approximately 14.5 million health workers in 2030 is anticipated based on the threshold of human resource needs related to the SDG health targets [ 16 ]. Other challenges at the PHC level recently have also been addressed, including long waiting times, dissatisfaction with referral systems, high burnout rates, and limited accessibility in rural areas, which exacerbate existing WPV issues [ 14 ].

As PHC system quality relies entirely on its workers, the issue of WPV requires more attention. WPV issues must be examined separately between PHC and other clinical settings to support an effective violence prevention strategy for PHC, given that the violence characteristics and other relevant factors can vary by facility type. In addition, PHC workers also have distinct services, work tasks, and work environments [ 11 ]. Since the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978, interest in conducting empirical studies investigating WPV in the PHC setting has increased worldwide [ 17 ]. Nevertheless, a comprehensive systematic review summarising the results from previous studies has never been published. Understanding this issue among workers who serve under a robust PHC system would be equally essential and requires attention to critical dimensions on par with WPV incidents in other clinical settings, especially hospitals. Therefore, this preliminary systematic review of WPV against the PHC workforce analysed and summarised the current information, including the WPV prevalence, predisposing factors, implications, and preventive measures in previous research.

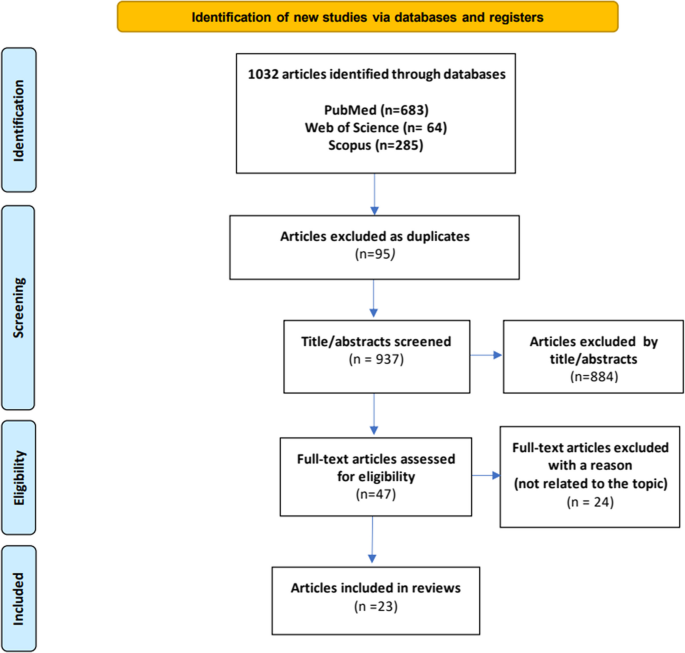

Literature sources

This systematic review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 review protocol [ 18 ]. A comprehensive database search of the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed databases was conducted in February 2023 using key terms related to WPV (“violence”, “harassment”, “abuse”, “conflict”, “confrontation”, and “assault”), workplace setting (“primary healthcare”, “primary care”, “community unit”, “family care”, “general practice”), and victims (“healthcare personnel”, “healthcare provider”, “medical staff”, “healthcare worker”). The keywords were combined using advanced field code searching (TITLE–ABS–KEY), phrase searching, truncation, and the Boolean operators “OR” and “AND”.

Eligibility criteria

All selected studies were original articles written in English and published within the last 10 years (2013–2023) on optimal sources or current literature. The articles were selected based on the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Described all violence typology (Types I–IV) and its form (verbal abuse, physical assault, physical threat, racism, bullying, or sexual assault);

The topic of interest concerned every category of PHC personnel (family doctor, general practitioner, nurse, pharmacist, administrative staff).

Exclusion criteria

The violence occurred in a tertiary or secondary setting (during training/industrial attachment at a hospital);

Case reports or series, and technical notes.

Study selection and data extraction

All research team members were involved in screening the titles and abstracts of all articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All potentially eligible articles were retained to evaluate the full text, which was conducted interchangeably by two teams of four members. Differences in opinion were resolved with the research team leader’s input. Before the data extraction and analysis, the methodological quality of the finalised article was assessed using the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Based on the outcomes of interest, the information obtained from the included articles was compiled in Excel and grouped into the following categories: (i) prevalence, typology, and form of violence, (ii) predisposing factors, (iii) implications, and (iv) preventive measures. Figure 1 depicts the article selection process flow.

PRISMA flow diagram

General characteristics of the studies