- Researching

- 3. Sub-questions

How to develop research sub-questions

Once you have become familiar with your topic through your background research , you can begin to think about how to approach answering your Key Inquiry Question .

However, the Key Inquiry Question is usually too broad to answer at this early juncture.

Therefore, you need to break your Key Inquiry Question into smaller questions (called 'sub-questions') in order to answer it sufficiently.

Sub-questions are secondary questions that are related to a primary or main inquiry question and are used to break down and further explore a particular aspect of the main question.

They help to clarify the main question and provide more specific direction for the research.

How to create sub-questions

A good Key Inquiry Question can easily be divided into three separate parts which can be turned into sub-questions.

Based upon good background research , you should be able to identify the three divisions of your Key Inquiry Question .

For example:

If your Key Inquiry Question was:

Why did Martin Luther King believe that social problems could be fixed through non-violent means?

The three parts that need to be answered separately can be highlighted as follows:

Why did Martin Luther King believe that social problems could be fixed through non-violent means ?

Each of these parts can be turned into three sub-questions (with the same three elements highlighted).

What were Martin Luther King’s beliefs about society?

For what social problems did Martin Luther King want to find a solution?

How did Martin Luther King imagine that non-violent practices could help ?

The importance of good sub-questions

Spend time thinking of good sub-questions. Well thought-out sub-questions can mean the difference between an average and an excellent essay.

Good sub-questions should:

- Be 'open' questions (This means that they cannot be answered with a simple 'yes' or 'no' answer. Usually this means starting the question with: what, why, or how)

- Incorporate terms and concepts that you learnt during your background research

In answering each of your three sub-questions through source research , you will ultimately have an answer for your Key Inquiry Question .

Watch a video explanation on the History Skills YouTube channel:

Watch on YouTube

Improving your sub-questions

Even though you are required to create sub-questions at the beginning of your research process , it does not mean that they do not change.

As you begin finding sources that help answer your original sub-questions, you will find that you will need to modify your questions.

This is usually the result of discovering further, more specific, information about your topic.

Improving your sub-questions during your source research stage will result in better topic sentences and, as a result, a better essay .

What role did the bombings of Tokyo , Hiroshima and Nagasaki have on Japan’s decision to surrender at the end of World War Two?

An initial and simplistic set of sub-questions could be:

- What role did the bombing of Tokyo have on Japan’s decision to surrender at the end of World War Two?

- What role did the bombing of Hiroshima have on Japan’s decision to surrender at the end of World War Two?

- What role did the bombing of Nagasaki have on Japan’s decision to surrender at the end of World War Two?

However, after conducting further research, they could be improved by including specific dates and historical information :

- What role did the March 9th incendiary bombings of Tokyo have on Japan's decision to surrender at the end of World War Two ?

- What role did the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6th have on Japan's decision to surrender at the end of World War Two ?

- What role did the atomic bombing of Nagasaki August 9th have on Japan's decision to surrender at the end of World War Two ?

Finally, after finding some detailed primary and secondary sources, they could be further improved by citing the role that key people played :

- How did the March 9th incendiary bombings of Tokyo motivate emperor Hirohito to become more involved in ending the Second World War?

- Why did the Japanese government not surrender after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on the 6th of August, 1945 ?

- Why did Hirohito finally decide to surrender after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki on August 9th, 1945 ?

Test your learning

No personal information is collected as part of this quiz. Only the selected responses to the questions are recorded.

What's next?

Need a digital Research Journal?

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

Formulating Your Research Question

- First Online: 26 May 2018

Cite this chapter

- Eva O. L. Lantsoght 2 , 3

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

193k Accesses

In this chapter, the research question is studied. We focus on how to find a research question that is specific enough, so that you are not tempted to explore paths that are only tangentially related to your research question. The literature review identifies gaps in the current knowledge, and you will learn how to frame a research question within these gaps. We then explore how to subdivide the research question into subquestions. These subquestions become the chapters of your dissertation. We also look at creative thinking, a skill necessary to think out of the box to formulate your research question. This chapter discusses how to convince your supervisor of your research question. It can happen that your supervisor already has an idea of the direction in which your research should be going, but if you can provide technically sound arguments based on your literature review why this approach is not ideal, and why you propose a different road, you should be able to have the freedom to explore your proposed option. Once you have outlined your research question, it is necessary to turn the question and subquestions into practical actions. These practical actions link back to the planning skills you learned in Chap. 3 .

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Time blocks of 25 minutes during which you concentrate on one single task. You can find more information about the Pomodoro technique in the glossary of Part II.

I often work with noise-cancelling headphones.

The course is sweet and short, and runs frequently. I highly recommend it!

Refer to Chap. 4 for examples on how I use mindmaps to structure documents, such as a literature review report.

Further Reading and References

Kara, H. (2015). Creative research methods in the Social Sciences: A practical guide . Bristol: Policy Press.

Google Scholar

Kara, H. (2015). How to choose your research question. PhD Talk . http://phdtalk.blogspot.com/2015/07/how-to-choose-your-research-question.html

Lantsoght, E. (2012). The creative process: The importance of questions. PhD Talk . http://phdtalk.blogspot.nl/2012/11/the-creative-process-importance-of.html

Feynman, R. P., Leighton, R., & Hutchings, E. (1997). “Surely you’re joking, Mr. Feynman!”: Adventures of a curious character (1st pbk ed.). New York: W.W. Norton.

Lantsoght, E. (2012). The creative process: The creative habit. PhD Talk . http://phdtalk.blogspot.nl/2012/11/the-creative-process-creative-habit.html

Rose, C. (2016). 15 minute history . http://15minutehistory.org /

Oakley, B. (2014). A mind for numbers: How to excel at Math and Science (even if you flunked algebra) . New York: TarcherPerigree.

Lantsoght E (2011). Book review: Starting research: An introduction to academic research and dissertation writing – Roy Preece. PhD Talk . http://phdtalk.blogspot.nl/2011/07/book-review-starting-research.html .

Preece, R. (2000). Starting research: An introduction to academic research and dissertation writing . London: Continuum.

Lantsoght, E. (2014). An example outline diagram for structuring your dissertation. PhD Talk . http://phdtalk.blogspot.nl/2014/08/an-example-outline-diagram-for.html

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador

Eva O. L. Lantsoght

Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Lantsoght, E.O.L. (2018). Formulating Your Research Question. In: The A-Z of the PhD Trajectory. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77425-1_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77425-1_5

Published : 26 May 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-77424-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-77425-1

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Research Question: Types and Examples

The first step in any research project is framing the research question. It can be considered the core of any systematic investigation as the research outcomes are tied to asking the right questions. Thus, this primary interrogation point sets the pace for your research as it helps collect relevant and insightful information that ultimately influences your work.

Typically, the research question guides the stages of inquiry, analysis, and reporting. Depending on the use of quantifiable or quantitative data, research questions are broadly categorized into quantitative or qualitative research questions. Both types of research questions can be used independently or together, considering the overall focus and objectives of your research.

What is a research question?

A research question is a clear, focused, concise, and arguable question on which your research and writing are centered. 1 It states various aspects of the study, including the population and variables to be studied and the problem the study addresses. These questions also set the boundaries of the study, ensuring cohesion.

Designing the research question is a dynamic process where the researcher can change or refine the research question as they review related literature and develop a framework for the study. Depending on the scale of your research, the study can include single or multiple research questions.

A good research question has the following features:

- It is relevant to the chosen field of study.

- The question posed is arguable and open for debate, requiring synthesizing and analysis of ideas.

- It is focused and concisely framed.

- A feasible solution is possible within the given practical constraint and timeframe.

A poorly formulated research question poses several risks. 1

- Researchers can adopt an erroneous design.

- It can create confusion and hinder the thought process, including developing a clear protocol.

- It can jeopardize publication efforts.

- It causes difficulty in determining the relevance of the study findings.

- It causes difficulty in whether the study fulfils the inclusion criteria for systematic review and meta-analysis. This creates challenges in determining whether additional studies or data collection is needed to answer the question.

- Readers may fail to understand the objective of the study. This reduces the likelihood of the study being cited by others.

Now that you know “What is a research question?”, let’s look at the different types of research questions.

Types of research questions

Depending on the type of research to be done, research questions can be classified broadly into quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies. Knowing the type of research helps determine the best type of research question that reflects the direction and epistemological underpinnings of your research.

The structure and wording of quantitative 2 and qualitative research 3 questions differ significantly. The quantitative study looks at causal relationships, whereas the qualitative study aims at exploring a phenomenon.

- Quantitative research questions:

- Seeks to investigate social, familial, or educational experiences or processes in a particular context and/or location.

- Answers ‘how,’ ‘what,’ or ‘why’ questions.

- Investigates connections, relations, or comparisons between independent and dependent variables.

Quantitative research questions can be further categorized into descriptive, comparative, and relationship, as explained in the Table below.

- Qualitative research questions

Qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional, and more flexible. It concerns broad areas of research or more specific areas of study to discover, explain, or explore a phenomenon. These are further classified as follows:

- Mixed-methods studies

Mixed-methods studies use both quantitative and qualitative research questions to answer your research question. Mixed methods provide a complete picture than standalone quantitative or qualitative research, as it integrates the benefits of both methods. Mixed methods research is often used in multidisciplinary settings and complex situational or societal research, especially in the behavioral, health, and social science fields.

What makes a good research question

A good research question should be clear and focused to guide your research. It should synthesize multiple sources to present your unique argument, and should ideally be something that you are interested in. But avoid questions that can be answered in a few factual statements. The following are the main attributes of a good research question.

- Specific: The research question should not be a fishing expedition performed in the hopes that some new information will be found that will benefit the researcher. The central research question should work with your research problem to keep your work focused. If using multiple questions, they should all tie back to the central aim.

- Measurable: The research question must be answerable using quantitative and/or qualitative data or from scholarly sources to develop your research question. If such data is impossible to access, it is better to rethink your question.

- Attainable: Ensure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific.

- You have the expertise

- You have the equipment and resources

- Realistic: Developing your research question should be based on initial reading about your topic. It should focus on addressing a problem or gap in the existing knowledge in your field or discipline.

- Based on some sort of rational physics

- Can be done in a reasonable time frame

- Timely: The research question should contribute to an existing and current debate in your field or in society at large. It should produce knowledge that future researchers or practitioners can later build on.

- Novel

- Based on current technologies.

- Important to answer current problems or concerns.

- Lead to new directions.

- Important: Your question should have some aspect of originality. Incremental research is as important as exploring disruptive technologies. For example, you can focus on a specific location or explore a new angle.

- Meaningful whether the answer is “Yes” or “No.” Closed-ended, yes/no questions are too simple to work as good research questions. Such questions do not provide enough scope for robust investigation and discussion. A good research question requires original data, synthesis of multiple sources, and original interpretation and argumentation before providing an answer.

Steps for developing a good research question

The importance of research questions cannot be understated. When drafting a research question, use the following frameworks to guide the components of your question to ease the process. 4

- Determine the requirements: Before constructing a good research question, set your research requirements. What is the purpose? Is it descriptive, comparative, or explorative research? Determining the research aim will help you choose the most appropriate topic and word your question appropriately.

- Select a broad research topic: Identify a broader subject area of interest that requires investigation. Techniques such as brainstorming or concept mapping can help identify relevant connections and themes within a broad research topic. For example, how to learn and help students learn.

- Perform preliminary investigation: Preliminary research is needed to obtain up-to-date and relevant knowledge on your topic. It also helps identify issues currently being discussed from which information gaps can be identified.

- Narrow your focus: Narrow the scope and focus of your research to a specific niche. This involves focusing on gaps in existing knowledge or recent literature or extending or complementing the findings of existing literature. Another approach involves constructing strong research questions that challenge your views or knowledge of the area of study (Example: Is learning consistent with the existing learning theory and research).

- Identify the research problem: Once the research question has been framed, one should evaluate it. This is to realize the importance of the research questions and if there is a need for more revising (Example: How do your beliefs on learning theory and research impact your instructional practices).

How to write a research question

Those struggling to understand how to write a research question, these simple steps can help you simplify the process of writing a research question.

Sample Research Questions

The following are some bad and good research question examples

- Example 1

- Example 2

References:

- Thabane, L., Thomas, T., Ye, C., & Paul, J. (2009). Posing the research question: not so simple. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie , 56 (1), 71-79.

- Rutberg, S., & Bouikidis, C. D. (2018). Focusing on the fundamentals: A simplistic differentiation between qualitative and quantitative research. Nephrology Nursing Journal , 45 (2), 209-213.

- Kyngäs, H. (2020). Qualitative research and content analysis. The application of content analysis in nursing science research , 3-11.

- Mattick, K., Johnston, J., & de la Croix, A. (2018). How to… write a good research question. The clinical teacher , 15 (2), 104-108.

- Fandino, W. (2019). Formulating a good research question: Pearls and pitfalls. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia , 63 (8), 611.

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP journal club , 123 (3), A12-A13

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

- 6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in the World of Research

Language and grammar rules for academic writing, you may also like, mla works cited page: format, template & examples, academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , 9 steps to publish a research paper, what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging, 6 tips for post-doc researchers to take their....

Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

The “Golden Thread” Explained Simply (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

The research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.

Research Aims: What are they?

Simply put, the research aim(s) is a statement that reflects the broad overarching goal (s) of the research project. Research aims are fairly high-level (low resolution) as they outline the general direction of the research and what it’s trying to achieve .

Research Aims: Examples

True to the name, research aims usually start with the wording “this research aims to…”, “this research seeks to…”, and so on. For example:

“This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.” “This study sets out to assess the interaction between student support and self-care on well-being in engineering graduate students”

As you can see, these research aims provide a high-level description of what the study is about and what it seeks to achieve. They’re not hyper-specific or action-oriented, but they’re clear about what the study’s focus is and what is being investigated.

Need a helping hand?

Research Objectives: What are they?

The research objectives take the research aims and make them more practical and actionable . In other words, the research objectives showcase the steps that the researcher will take to achieve the research aims.

The research objectives need to be far more specific (higher resolution) and actionable than the research aims. In fact, it’s always a good idea to craft your research objectives using the “SMART” criteria. In other words, they should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound”.

Research Objectives: Examples

Let’s look at two examples of research objectives. We’ll stick with the topic and research aims we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic:

To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation. To assess employee perceptions of digital transformation in retail HR. To identify the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR.

And for the student wellness topic:

To determine whether student self-care predicts the well-being score of engineering graduate students. To determine whether student support predicts the well-being score of engineering students. To assess the interaction between student self-care and student support when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students.

As you can see, these research objectives clearly align with the previously mentioned research aims and effectively translate the low-resolution aims into (comparatively) higher-resolution objectives and action points . They give the research project a clear focus and present something that resembles a research-based “to-do” list.

Research Questions: What are they?

Finally, we arrive at the all-important research questions. The research questions are, as the name suggests, the key questions that your study will seek to answer . Simply put, they are the core purpose of your dissertation, thesis, or research project. You’ll present them at the beginning of your document (either in the introduction chapter or literature review chapter) and you’ll answer them at the end of your document (typically in the discussion and conclusion chapters).

The research questions will be the driving force throughout the research process. For example, in the literature review chapter, you’ll assess the relevance of any given resource based on whether it helps you move towards answering your research questions. Similarly, your methodology and research design will be heavily influenced by the nature of your research questions. For instance, research questions that are exploratory in nature will usually make use of a qualitative approach, whereas questions that relate to measurement or relationship testing will make use of a quantitative approach.

Let’s look at some examples of research questions to make this more tangible.

Research Questions: Examples

Again, we’ll stick with the research aims and research objectives we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic (which would be qualitative in nature):

How do employees perceive digital transformation in retail HR? What are the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR?

And for the student wellness topic (which would be quantitative in nature):

Does student self-care predict the well-being scores of engineering graduate students? Does student support predict the well-being scores of engineering students? Do student self-care and student support interact when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students?

You’ll probably notice that there’s quite a formulaic approach to this. In other words, the research questions are basically the research objectives “converted” into question format. While that is true most of the time, it’s not always the case. For example, the first research objective for the digital transformation topic was more or less a step on the path toward the other objectives, and as such, it didn’t warrant its own research question.

So, don’t rush your research questions and sloppily reword your objectives as questions. Carefully think about what exactly you’re trying to achieve (i.e. your research aim) and the objectives you’ve set out, then craft a set of well-aligned research questions . Also, keep in mind that this can be a somewhat iterative process , where you go back and tweak research objectives and aims to ensure tight alignment throughout the golden thread.

The importance of strong alignment

Alignment is the keyword here and we have to stress its importance . Simply put, you need to make sure that there is a very tight alignment between all three pieces of the golden thread. If your research aims and research questions don’t align, for example, your project will be pulling in different directions and will lack focus . This is a common problem students face and can cause many headaches (and tears), so be warned.

Take the time to carefully craft your research aims, objectives and research questions before you run off down the research path. Ideally, get your research supervisor/advisor to review and comment on your golden thread before you invest significant time into your project, and certainly before you start collecting data .

Recap: The golden thread

In this post, we unpacked the golden thread of research, consisting of the research aims , research objectives and research questions . You can jump back to any section using the links below.

As always, feel free to leave a comment below – we always love to hear from you. Also, if you’re interested in 1-on-1 support, take a look at our private coaching service here.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

39 Comments

Thank you very much for your great effort put. As an Undergraduate taking Demographic Research & Methodology, I’ve been trying so hard to understand clearly what is a Research Question, Research Aim and the Objectives in a research and the relationship between them etc. But as for now I’m thankful that you’ve solved my problem.

Well appreciated. This has helped me greatly in doing my dissertation.

An so delighted with this wonderful information thank you a lot.

so impressive i have benefited a lot looking forward to learn more on research.

I am very happy to have carefully gone through this well researched article.

Infact,I used to be phobia about anything research, because of my poor understanding of the concepts.

Now,I get to know that my research question is the same as my research objective(s) rephrased in question format.

I please I would need a follow up on the subject,as I intends to join the team of researchers. Thanks once again.

Thanks so much. This was really helpful.

I know you pepole have tried to break things into more understandable and easy format. And God bless you. Keep it up

i found this document so useful towards my study in research methods. thanks so much.

This is my 2nd read topic in your course and I should commend the simplified explanations of each part. I’m beginning to understand and absorb the use of each part of a dissertation/thesis. I’ll keep on reading your free course and might be able to avail the training course! Kudos!

Thank you! Better put that my lecture and helped to easily understand the basics which I feel often get brushed over when beginning dissertation work.

This is quite helpful. I like how the Golden thread has been explained and the needed alignment.

This is quite helpful. I really appreciate!

The article made it simple for researcher students to differentiate between three concepts.

Very innovative and educational in approach to conducting research.

I am very impressed with all these terminology, as I am a fresh student for post graduate, I am highly guided and I promised to continue making consultation when the need arise. Thanks a lot.

A very helpful piece. thanks, I really appreciate it .

Very well explained, and it might be helpful to many people like me.

Wish i had found this (and other) resource(s) at the beginning of my PhD journey… not in my writing up year… 😩 Anyways… just a quick question as i’m having some issues ordering my “golden thread”…. does it matter in what order you mention them? i.e., is it always first aims, then objectives, and finally the questions? or can you first mention the research questions and then the aims and objectives?

Thank you for a very simple explanation that builds upon the concepts in a very logical manner. Just prior to this, I read the research hypothesis article, which was equally very good. This met my primary objective.

My secondary objective was to understand the difference between research questions and research hypothesis, and in which context to use which one. However, I am still not clear on this. Can you kindly please guide?

In research, a research question is a clear and specific inquiry that the researcher wants to answer, while a research hypothesis is a tentative statement or prediction about the relationship between variables or the expected outcome of the study. Research questions are broader and guide the overall study, while hypotheses are specific and testable statements used in quantitative research. Research questions identify the problem, while hypotheses provide a focus for testing in the study.

Exactly what I need in this research journey, I look forward to more of your coaching videos.

This helped a lot. Thanks so much for the effort put into explaining it.

What data source in writing dissertation/Thesis requires?

What is data source covers when writing dessertation/thesis

This is quite useful thanks

I’m excited and thankful. I got so much value which will help me progress in my thesis.

where are the locations of the reserch statement, research objective and research question in a reserach paper? Can you write an ouline that defines their places in the researh paper?

Very helpful and important tips on Aims, Objectives and Questions.

Thank you so much for making research aim, research objectives and research question so clear. This will be helpful to me as i continue with my thesis.

Thanks much for this content. I learned a lot. And I am inspired to learn more. I am still struggling with my preparation for dissertation outline/proposal. But I consistently follow contents and tutorials and the new FB of GRAD Coach. Hope to really become confident in writing my dissertation and successfully defend it.

As a researcher and lecturer, I find splitting research goals into research aims, objectives, and questions is unnecessarily bureaucratic and confusing for students. For most biomedical research projects, including ‘real research’, 1-3 research questions will suffice (numbers may differ by discipline).

Awesome! Very important resources and presented in an informative way to easily understand the golden thread. Indeed, thank you so much.

Well explained

The blog article on research aims, objectives, and questions by Grad Coach is a clear and insightful guide that aligns with my experiences in academic research. The article effectively breaks down the often complex concepts of research aims and objectives, providing a straightforward and accessible explanation. Drawing from my own research endeavors, I appreciate the practical tips offered, such as the need for specificity and clarity when formulating research questions. The article serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers, offering a concise roadmap for crafting well-defined research goals and objectives. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced researcher, this article provides practical insights that contribute to the foundational aspects of a successful research endeavor.

A great thanks for you. it is really amazing explanation. I grasp a lot and one step up to research knowledge.

I really found these tips helpful. Thank you very much Grad Coach.

I found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing this.

thank you so much, the explanation and examples are really helpful

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Memberships

Research questions explained plus examples

Research questions: This article provides a practical explanation of the topic of research questions . The article begins with a general definition of the term “research question” and an explanation of the different types of research questions. You will also find several useful tips for developing your own research question and sub-questions, for example, for a thesis or other research project. Enjoy reading!

What is a research question?

When conducting research, the research question and sub-questions are essential. The research question reflects the main question of the research, and the sub-questions contribute to answering this main question. Therefore, it is essential to carefully consider the formulation of the questions.

A good research question is concrete, relevant, and well-defined. It should be clear what is being researched and what the purpose of the research is. The sub-questions should match this and should be specific enough to be answered within the research. The sub-questions should also contribute to answering the main question.

Example research question

An example of a research question with sub-questions could be: “How can communication between employees and managers be improved within organization X?” The sub-questions could be:

- What does the current communication structure look like within organization X?

- What are the obstacles to communication between employees and managers?

- What communication tools are currently used, and are they effective?

- What are the best practices for improving communication between employees and managers?

Creating good research questions and sub-questions is important for carrying out a clear and relevant study. By paying sufficient attention to this, the research can be carried out efficiently and effectively, and valuable results can be achieved.

Common types of research questions

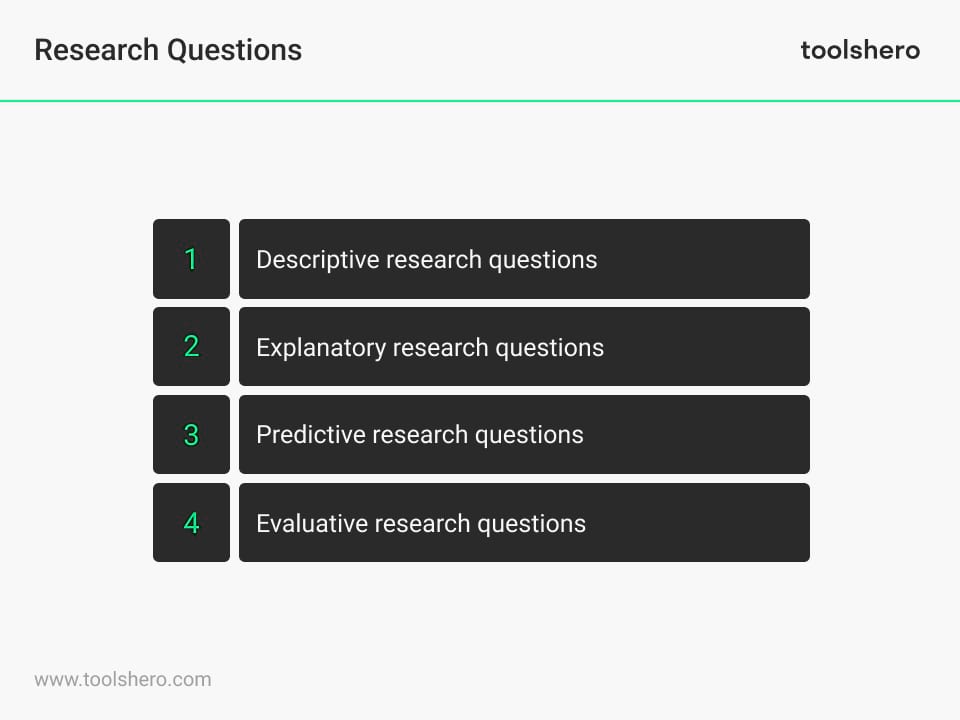

Figure 1 – 4 types of Research questions

1. Descriptive research questions

These questions focus on describing a phenomenon, situation, or population. They are aimed at gathering information about what is going on and what is known about the research topic. An example of a descriptive research question is: “What percentage of students at university X have a part-time job alongside their studies?”

2. Explanatory research questions

These questions focus on finding explanations for a particular phenomenon or situation. They aim to find causal relationships between different variables. An example of an explanatory research question is: “What is the relationship between stress and sleep deprivation among healthcare workers?”

3. Predictive research questions

These questions focus on predicting future events or outcomes based on certain variables or factors. They aim to find patterns and trends that can help make predictions. An example of a predictive research question is: “How much is the sales of product X expected to increase in the coming year?”

4. Evaluative research questions

These questions focus on evaluating the effectiveness or efficiency of a particular intervention, policy, or program. They aim to assess the impact of a particular action or change. An example of an evaluative research question is: “What is the effect of introducing a new teaching method on the academic performance of students?”

It is important to choose the right type of research question that fits the purpose of the research and the research method used. By formulating a clear and specific research question, a researcher can work more effectively and achieve the desired results.

Research Methods For Business Students Course A-Z guide to writing a rockstar Research Paper with a bulletproof Research Methodology! More information

What criteria should a good research question meet?

Below you will find six criteria that a good research question should meet. These criteria are specificity, clarity, relevance, feasibility, significance, and interest.

The research question must be formulated clearly and specifically, so that it is clear what the subject of the research is.

The research question must be relevant to the field and build upon existing knowledge and insights.

The research question must be feasible within the available time, resources, and knowledge of the researcher.

The research question must be verifiable through empirical research or data analysis, so that the results can be objectively evaluated.

The research question must be original and contribute to expanding existing knowledge or developing new insights.

The research question must be challenging and inspiring, so that it motivates the researcher to work hard and perform at a high level.

How to write a good research question?

With the following steps, you can formulate a good research question that is relevant to the field in which you are conducting research.

Step 1: choose a topic

Choose a topic that is relevant to your field and contains keywords that people search for. Use a tool such as Google Keyword Planner to find keywords.

Step 2: prepare

Read literature and articles about the topic and identify gaps in knowledge or conflicting results that are worth further investigation.

Step 3: develop a preliminary research question

Formulate a general preliminary research question based on the findings from the literature. Make sure that this question is clear, concise, and relevant. Use relevant terms in your question.

Step 4: refine

Refine the general question into a specific question that can be answered through empirical research or data analysis. Use clear and simple language, and avoid jargon.

Step 5: check

Check if the question meets the characteristics of a good research question: is the question specific, relevant, feasible, verifiable, original, and inspiring?

Other tips for developing a research question for your thesis

Developing a good research question is essential for a successful thesis. Here are some tips that can help you develop a research question:

Choose a relevant topic

Choose a topic that is relevant to your field of study and that you are passionate about. This will increase your motivation and help you make a meaningful contribution to your field.

Determine the purpose of your research

Ask yourself what you want to achieve with your research. Do you want to discover a new problem, solve an existing problem, or introduce a new concept? Be specific Make sure that your research question is specific and not too broad. It should have a clear purpose and focus on a limited topic.

Use clear language

Make sure that your research question is clear and understandable to others. Avoid jargon and technical terms, unless they are necessary for the context of your research.

Make it measurable

Ensure that your research question is measurable, so that you can evaluate and analyze the results of your research.

Consider data availability

Now it’s your turn

What do you think? Do you recognize the explanation about research questions? Have you often worked with research questions? Like during the process of writing your thesis or another type of research? Do you find the tips and recommendations in this article helpful? Do you have other tips or comments?

Share your experience and knowledge in the comments box below.

More information

- Agee, J. (2009). Developing qualitative research questions: A reflective process . International journal of qualitative studies in education, 22(4), 431-447.

- Andrews, R. (2003). Research questions . Bloomsbury Publishing .

- Barick, R. (2021). Research Methods For Business Students . Retrieved 02/16/2024 from Udemy.

- Dillon, J. T. (1984). The classification of research questions . Review of Educational Research, 54(3), 327-361.

- White, P. (2017). Developing research questions. Bloomsbury Publishing.

How to cite this article: Janse, B. (2023). Research questions . Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/research/research-questions/

Original publication date: 05/12/2023 | Last update: 01/02/2024

Add a link to this page on your website: <a href=”https://www.toolshero.com/research/research-questions/”>Toolshero: Research questions</a>

Did you find this article interesting?

Your rating is more than welcome or share this article via Social media!

Average rating 4.2 / 5. Vote count: 5

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Ben Janse is a young professional working at ToolsHero as Content Manager. He is also an International Business student at Rotterdam Business School where he focusses on analyzing and developing management models. Thanks to his theoretical and practical knowledge, he knows how to distinguish main- and side issues and to make the essence of each article clearly visible.

Related ARTICLES

Respondents: the definition, meaning and the recruitment

Market Research: the Basics and Tools

Gartner Magic Quadrant report and basics explained

Univariate Analysis: basic theory and example

Bivariate Analysis in Research explained

Contingency Table: the Theory and an Example

Also interesting.

Content Analysis explained plus example

Field Research explained

Observational Research Method explained

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

BOOST YOUR SKILLS

Toolshero supports people worldwide ( 10+ million visitors from 100+ countries ) to empower themselves through an easily accessible and high-quality learning platform for personal and professional development.

By making access to scientific knowledge simple and affordable, self-development becomes attainable for everyone, including you! Join our learning platform and boost your skills with Toolshero.

POPULAR TOPICS

- Change Management

- Marketing Theories

- Problem Solving Theories

- Psychology Theories

ABOUT TOOLSHERO

- Free Toolshero e-book

- Memberships & Pricing

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg

- v.24(1); Jan-Mar 2019

Formulation of Research Question – Stepwise Approach

Simmi k. ratan.

Department of Pediatric Surgery, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi, India

1 Department of Community Medicine, North Delhi Municipal Corporation Medical College, New Delhi, India

2 Department of Pediatric Surgery, Batra Hospital and Research Centre, New Delhi, India

Formulation of research question (RQ) is an essentiality before starting any research. It aims to explore an existing uncertainty in an area of concern and points to a need for deliberate investigation. It is, therefore, pertinent to formulate a good RQ. The present paper aims to discuss the process of formulation of RQ with stepwise approach. The characteristics of good RQ are expressed by acronym “FINERMAPS” expanded as feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, relevant, manageable, appropriate, potential value, publishability, and systematic. A RQ can address different formats depending on the aspect to be evaluated. Based on this, there can be different types of RQ such as based on the existence of the phenomenon, description and classification, composition, relationship, comparative, and causality. To develop a RQ, one needs to begin by identifying the subject of interest and then do preliminary research on that subject. The researcher then defines what still needs to be known in that particular subject and assesses the implied questions. After narrowing the focus and scope of the research subject, researcher frames a RQ and then evaluates it. Thus, conception to formulation of RQ is very systematic process and has to be performed meticulously as research guided by such question can have wider impact in the field of social and health research by leading to formulation of policies for the benefit of larger population.

I NTRODUCTION

A good research question (RQ) forms backbone of a good research, which in turn is vital in unraveling mysteries of nature and giving insight into a problem.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ] RQ identifies the problem to be studied and guides to the methodology. It leads to building up of an appropriate hypothesis (Hs). Hence, RQ aims to explore an existing uncertainty in an area of concern and points to a need for deliberate investigation. A good RQ helps support a focused arguable thesis and construction of a logical argument. Hence, formulation of a good RQ is undoubtedly one of the first critical steps in the research process, especially in the field of social and health research, where the systematic generation of knowledge that can be used to promote, restore, maintain, and/or protect health of individuals and populations.[ 1 , 3 , 4 ] Basically, the research can be classified as action, applied, basic, clinical, empirical, administrative, theoretical, or qualitative or quantitative research, depending on its purpose.[ 2 ]

Research plays an important role in developing clinical practices and instituting new health policies. Hence, there is a need for a logical scientific approach as research has an important goal of generating new claims.[ 1 ]

C HARACTERISTICS OF G OOD R ESEARCH Q UESTION

“The most successful research topics are narrowly focused and carefully defined but are important parts of a broad-ranging, complex problem.”

A good RQ is an asset as it:

- Details the problem statement

- Further describes and refines the issue under study

- Adds focus to the problem statement

- Guides data collection and analysis

- Sets context of research.

Hence, while writing RQ, it is important to see if it is relevant to the existing time frame and conditions. For example, the impact of “odd-even” vehicle formula in decreasing the level of air particulate pollution in various districts of Delhi.

A good research is represented by acronym FINERMAPS[ 5 ]

Interesting.

- Appropriate

- Potential value and publishability

- Systematic.

Feasibility means that it is within the ability of the investigator to carry out. It should be backed by an appropriate number of subjects and methodology as well as time and funds to reach the conclusions. One needs to be realistic about the scope and scale of the project. One has to have access to the people, gadgets, documents, statistics, etc. One should be able to relate the concepts of the RQ to the observations, phenomena, indicators, or variables that one can access. One should be clear that the collection of data and the proceedings of project can be completed within the limited time and resources available to the investigator. Sometimes, a RQ appears feasible, but when fieldwork or study gets started, it proves otherwise. In this situation, it is important to write up the problems honestly and to reflect on what has been learned. One should try to discuss with more experienced colleagues or the supervisor so as to develop a contingency plan to anticipate possible problems while working on a RQ and find possible solutions in such situations.

This is essential that one has a real grounded interest in one's RQ and one can explore this and back it up with academic and intellectual debate. This interest will motivate one to keep going with RQ.

The question should not simply copy questions investigated by other workers but should have scope to be investigated. It may aim at confirming or refuting the already established findings, establish new facts, or find new aspects of the established facts. It should show imagination of the researcher. Above all, the question has to be simple and clear. The complexity of a question can frequently hide unclear thoughts and lead to a confused research process. A very elaborate RQ, or a question which is not differentiated into different parts, may hide concepts that are contradictory or not relevant. This needs to be clear and thought-through. Having one key question with several subcomponents will guide your research.

This is the foremost requirement of any RQ and is mandatory to get clearance from appropriate authorities before stating research on the question. Further, the RQ should be such that it minimizes the risk of harm to the participants in the research, protect the privacy and maintain their confidentiality, and provide the participants right to withdraw from research. It should also guide in avoiding deceptive practices in research.

The question should of academic and intellectual interest to people in the field you have chosen to study. The question preferably should arise from issues raised in the current situation, literature, or in practice. It should establish a clear purpose for the research in relation to the chosen field. For example, filling a gap in knowledge, analyzing academic assumptions or professional practice, monitoring a development in practice, comparing different approaches, or testing theories within a specific population are some of the relevant RQs.

Manageable (M): It has the similar essence as of feasibility but mainly means that the following research can be managed by the researcher.

Appropriate (A): RQ should be appropriate logically and scientifically for the community and institution.

Potential value and publishability (P): The study can make significant health impact in clinical and community practices. Therefore, research should aim for significant economic impact to reduce unnecessary or excessive costs. Furthermore, the proposed study should exist within a clinical, consumer, or policy-making context that is amenable to evidence-based change. Above all, a good RQ must address a topic that has clear implications for resolving important dilemmas in health and health-care decisions made by one or more stakeholder groups.

Systematic (S): Research is structured with specified steps to be taken in a specified sequence in accordance with the well-defined set of rules though it does not rule out creative thinking.

Example of RQ: Would the topical skin application of oil as a skin barrier reduces hypothermia in preterm infants? This question fulfills the criteria of a good RQ, that is, feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant.

Types of research question

A RQ can address different formats depending on the aspect to be evaluated.[ 6 ] For example:

- Existence: This is designed to uphold the existence of a particular phenomenon or to rule out rival explanation, for example, can neonates perceive pain?

- Description and classification: This type of question encompasses statement of uniqueness, for example, what are characteristics and types of neuropathic bladders?

- Composition: It calls for breakdown of whole into components, for example, what are stages of reflux nephropathy?

- Relationship: Evaluate relation between variables, for example, association between tumor rupture and recurrence rates in Wilm's tumor

- Descriptive—comparative: Expected that researcher will ensure that all is same between groups except issue in question, for example, Are germ cell tumors occurring in gonads more aggressive than those occurring in extragonadal sites?

- Causality: Does deletion of p53 leads to worse outcome in patients with neuroblastoma?

- Causality—comparative: Such questions frequently aim to see effect of two rival treatments, for example, does adding surgical resection improves survival rate outcome in children with neuroblastoma than with chemotherapy alone?

- Causality–Comparative interactions: Does immunotherapy leads to better survival outcome in neuroblastoma Stage IV S than with chemotherapy in the setting of adverse genetic profile than without it? (Does X cause more changes in Y than those caused by Z under certain condition and not under other conditions).

How to develop a research question

- Begin by identifying a broader subject of interest that lends itself to investigate, for example, hormone levels among hypospadias

- Do preliminary research on the general topic to find out what research has already been done and what literature already exists.[ 7 ] Therefore, one should begin with “information gaps” (What do you already know about the problem? For example, studies with results on testosterone levels among hypospadias

- What do you still need to know? (e.g., levels of other reproductive hormones among hypospadias)

- What are the implied questions: The need to know about a problem will lead to few implied questions. Each general question should lead to more specific questions (e.g., how hormone levels differ among isolated hypospadias with respect to that in normal population)

- Narrow the scope and focus of research (e.g., assessment of reproductive hormone levels among isolated hypospadias and hypospadias those with associated anomalies)

- Is RQ clear? With so much research available on any given topic, RQs must be as clear as possible in order to be effective in helping the writer direct his or her research

- Is the RQ focused? RQs must be specific enough to be well covered in the space available

- Is the RQ complex? RQs should not be answerable with a simple “yes” or “no” or by easily found facts. They should, instead, require both research and analysis on the part of the writer

- Is the RQ one that is of interest to the researcher and potentially useful to others? Is it a new issue or problem that needs to be solved or is it attempting to shed light on previously researched topic

- Is the RQ researchable? Consider the available time frame and the required resources. Is the methodology to conduct the research feasible?

- Is the RQ measurable and will the process produce data that can be supported or contradicted?

- Is the RQ too broad or too narrow?

- Create Hs: After formulating RQ, think where research is likely to be progressing? What kind of argument is likely to be made/supported? What would it mean if the research disputed the planned argument? At this step, one can well be on the way to have a focus for the research and construction of a thesis. Hs consists of more specific predictions about the nature and direction of the relationship between two variables. It is a predictive statement about the outcome of the research, dictate the method, and design of the research[ 1 ]

- Understand implications of your research: This is important for application: whether one achieves to fill gap in knowledge and how the results of the research have practical implications, for example, to develop health policies or improve educational policies.[ 1 , 8 ]

Brainstorm/Concept map for formulating research question

- First, identify what types of studies have been done in the past?

- Is there a unique area that is yet to be investigated or is there a particular question that may be worth replicating?

- Begin to narrow the topic by asking open-ended “how” and “why” questions

- Evaluate the question

- Develop a Hypothesis (Hs)

- Write down the RQ.

Writing down the research question

- State the question in your own words

- Write down the RQ as completely as possible.

For example, Evaluation of reproductive hormonal profile in children presenting with isolated hypospadias)

- Divide your question into concepts. Narrow to two or three concepts (reproductive hormonal profile, isolated hypospadias, compare with normal/not isolated hypospadias–implied)

- Specify the population to be studied (children with isolated hypospadias)

- Refer to the exposure or intervention to be investigated, if any

- Reflect the outcome of interest (hormonal profile).

Another example of a research question

Would the topical skin application of oil as a skin barrier reduces hypothermia in preterm infants? Apart from fulfilling the criteria of a good RQ, that is, feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant, it also details about the intervention done (topical skin application of oil), rationale of intervention (as a skin barrier), population to be studied (preterm infants), and outcome (reduces hypothermia).

Other important points to be heeded to while framing research question

- Make reference to a population when a relationship is expected among a certain type of subjects

- RQs and Hs should be made as specific as possible

- Avoid words or terms that do not add to the meaning of RQs and Hs

- Stick to what will be studied, not implications

- Name the variables in the order in which they occur/will be measured

- Avoid the words significant/”prove”

- Avoid using two different terms to refer to the same variable.

Some of the other problems and their possible solutions have been discussed in Table 1 .

Potential problems and solutions while making research question

G OING B EYOND F ORMULATION OF R ESEARCH Q UESTION–THE P ATH A HEAD

Once RQ is formulated, a Hs can be developed. Hs means transformation of a RQ into an operational analog.[ 1 ] It means a statement as to what prediction one makes about the phenomenon to be examined.[ 4 ] More often, for case–control trial, null Hs is generated which is later accepted or refuted.

A strong Hs should have following characteristics:

- Give insight into a RQ

- Are testable and measurable by the proposed experiments

- Have logical basis

- Follows the most likely outcome, not the exceptional outcome.

E XAMPLES OF R ESEARCH Q UESTION AND H YPOTHESIS

Research question-1.

- Does reduced gap between the two segments of the esophagus in patients of esophageal atresia reduces the mortality and morbidity of such patients?

Hypothesis-1

- Reduced gap between the two segments of the esophagus in patients of esophageal atresia reduces the mortality and morbidity of such patients

- In pediatric patients with esophageal atresia, gap of <2 cm between two segments of the esophagus and proper mobilization of proximal pouch reduces the morbidity and mortality among such patients.

Research question-2

- Does application of mitomycin C improves the outcome in patient of corrosive esophageal strictures?

Hypothesis-2

In patients aged 2–9 years with corrosive esophageal strictures, 34 applications of mitomycin C in dosage of 0.4 mg/ml for 5 min over a period of 6 months improve the outcome in terms of symptomatic and radiological relief. Some other examples of good and bad RQs have been shown in Table 2 .

Examples of few bad (left-hand side column) and few good (right-hand side) research questions

R ESEARCH Q UESTION AND S TUDY D ESIGN

RQ determines study design, for example, the question aimed to find the incidence of a disease in population will lead to conducting a survey; to find risk factors for a disease will need case–control study or a cohort study. RQ may also culminate into clinical trial.[ 9 , 10 ] For example, effect of administration of folic acid tablet in the perinatal period in decreasing incidence of neural tube defect. Accordingly, Hs is framed.

Appropriate statistical calculations are instituted to generate sample size. The subject inclusion, exclusion criteria and time frame of research are carefully defined. The detailed subject information sheet and pro forma are carefully defined. Moreover, research is set off few examples of research methodology guided by RQ:

- Incidence of anorectal malformations among adolescent females (hospital-based survey)

- Risk factors for the development of spontaneous pneumoperitoneum in pediatric patients (case–control design and cohort study)

- Effect of technique of extramucosal ureteric reimplantation without the creation of submucosal tunnel for the preservation of upper tract in bladder exstrophy (clinical trial).

The results of the research are then be available for wider applications for health and social life

C ONCLUSION

A good RQ needs thorough literature search and deep insight into the specific area/problem to be investigated. A RQ has to be focused yet simple. Research guided by such question can have wider impact in the field of social and health research by leading to formulation of policies for the benefit of larger population.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

R EFERENCES

Dissertations & projects: Research questions

- Research questions

- The process of reviewing

- Project management

- Literature-based projects

Jump to content on these pages:

“The central question that you ask or hypothesis you frame drives your research: it defines your purpose.” Bryan Greetham, How to Write Your Undergraduate Dissertation

This page gives some help and guidance in developing a realistic research question. It also considers the role of sub-questions and how these can influence your methodological choices.

Choosing your research topic

You may have been provided with a list of potential topics or even specific questions to choose from. It is more common for you to have to come up with your own ideas and then refine them with the help of your tutor. This is a crucial decision as you will be immersing yourself in it for a long time.

Some students struggle to find a topic that is sufficiently significant and yet researchable within the limitations of an undergraduate project. You may feel overwhelmed by the freedom to choose your own topic but you could get ideas by considering the following:

Choose a topic that you find interesting . This may seem obvious but a lot of students go for what they think will be easy over what they think will be interesting - and regret it when they realise nothing is particularly easy and they are bored by the work. Think back over your lectures or talks from visiting speakers - was there anything you really enjoyed? Was there anything that left you with questions?

Choose something distinct . Whilst at undergraduate level you do not have to find something completely unique, if you find something a bit different you have more opportunity to come to some interesting conclusions. Have you some unique experiences that you can bring: personal biography, placements, study abroad etc?

Don't make your topic too wide . If your topic is too wide, it will be harder to develop research questions that you can actually answer in the context of a small research project.

Don't make your work too narrow . If your topic is too narrow, you will not be able to expand on the ideas sufficiently and make useful conclusions. You may also struggle to find enough literature to support it.

Scope out the field before deciding your topic . This is especially important if you have a few different options and are not sure which to pick. Spend a little time researching each one to get a feel for the amount of literature that exists and any particular avenues that could be worth exploring.

Think about your future . Some topics may fit better than others with your future plans, be they for further study or employment. Becoming more expert in something that you may have to be interviewed about is never a bad thing!

Once you have an idea (or even a few), speak to your tutor. They will advise on whether it is the right sort of topic for a dissertation or independent study. They have a lot of experience and will know if it is too much to take on, has enough material to build on etc.

Developing a research question or hypothesis

Research question vs hypothesis.

First, it may be useful to explain the difference between a research question and a hypothesis. A research question is simply a question that your research will address and hopefully answer (or give an explanation of why you couldn't answer it). A hypothesis is a statement that suggests how you expect something to function or behave (and which you would test to see if it actually happens or not).

Research question examples

- How significant is league table position when students choose their university?

- What impact can a diagnosis of depression have on physical health?

Note that these are open questions - i.e. they cannot be answered with a simple 'yes' or 'no'. This is the best form of question.

Hypotheses examples

- Students primarily choose their university based on league table position.

- A diagnosis of depression can impact physical health.

Note that these are things that you can test to see if they are true or false. This makes them more definite then research questions - but you can still answer them more fully than 'no they don't' or 'yes it does'. For example, in the above examples you would look to see how relevant other factors were when choosing universities and in what ways physical health may be impacted.

For more examples of the same topic formulated as hypotheses, research questions and paper titles see those given at the bottom of this document from Oakland University: Formulation of Research Hypothesis

Which do you need?

Generally, research questions are more common in the humanities, social sciences and business, whereas hypotheses are more common in the sciences. This is not a hard rule though, talk things through with your supervisor to see which they are expecting or which they think fits best with your topic.

What makes a good research question or hypothesis?

Unless you are undertaking a systematic review as your research method, you will develop your research question as a result of reviewing the literature on your broader topic. After all, it is only by seeing what research has already been done (or not) that you can justify the need for your question or your approach to answering it. At the end of that process, you should be able to come up with a question or hypothesis that is:

- Clear (easily understandable)

- Focused (specific not vague or huge)

- Answerable (the data is available and analysable in the time frame)

- Relevant (to your area of study)

- Significant (it is worth answering)

You can try a few out, using a table like this (yours would all be in the same discipline):

A similar, though different table is available from the University of California: What makes a good research topic? The completed table has some supervisor comments which may also be helpful.

Ultimately, your final research question will be mutually agreed between yourself and your supervisor - but you should always bring your own ideas to the conversation.

The role of sub-questions

Your main research question will probably still be too big to answer easily. This is where sub-questions come in. They are specific, narrower questions that you can answer directly from your data.

So, looking at the question " How much do online users know and care about how their self-images can be used by Apple, Google, Microsoft and Facebook? " from the table above, the sub-questions could be:

- What rights do the terms and conditions of signing up for Apple, Google, Microsoft and Facebook accounts give those companies regarding the use of self-images?

- What proportion of users read the terms and conditions when creating accounts with these companies?

- How aware are users of the rights they are giving away regarding their self-images when creating accounts with these companies?

- How comfortable are users with giving away these rights?

Together, the answers to your sub-questions should enable you to answer the overarching research question.

How do you answer your sub-questions?

Depending on the type of dissertation/project your are undertaking, some (or all) the questions may be answered with information collected from the literature and some (or none) may be answered by analysing data directly collected as part of your primary empirical research .

In the above example, the first question would be answered by documentary analysis of the relevant terms and conditions, the second by a mixture of reviewing the literature and analysing survey responses from participants and the last two also by analysing survey responses. Different projects will require different approaches.

Some sub-questions could be answered by reviewing the literature and others from empirical study.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Searching >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 1:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/dissertations

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

How to Craft a Research Question

In the following we will work on crafting a successful research question. At this point, don't be committed to a methodology, and beware that you are not writing a question that unconsciously leans to a particular methodology.

The process you follow is critical, not the methodology, at least not yet.

In the following, you will:

- Learn the process of writing a successful research question.

- Apply this process to your own research topic and questions.

- What research questions are.

- Types of research questions and subquestions.

- Ways qualitative and quantitative questions differ.

- How hypotheses go with questions in quantitative methodology.

Let's get started.

Developing a Research Question

Learning to write good research questions is a skill that takes practice. Developing a research question is a developmental process. As you read the literature and gain a greater understanding about your research problem, you will rework your research question until you are able to focus more specifically on what you want to explore and learn about during the formal research process. Keep in mind that a question typically goes through several iterations. So don't worry if your first attempts may not be the final product. This is normal.

Getting Oriented to Research Questions

Let's get oriented first. The research question is what the researcher seeks to answer by collecting data. It is the foundation of the entire study, because the question embodies the method by which the research problem—called for by the existing literature—will be solved. It's simple: You are going to solve your research problem by collecting information, and you collect that information by asking about a specific question or set of questions.

Simply by reading a well-formed research question, you can usually tell:

- What concept(s), phenomena, or variables are going to be measured in quantitative research or described in qualitative research.

- What research design will be used.

- What the sample will consist of.

As we proceed you will need to have knowledge of a variety of research terms. If you don't recognize and understand these terms, there are handouts in the Dissertation Research Seminar Courseroom that you can refer to. We strongly encourage you to take notes as you work your way through this document, and make sure that you understand each section.

Let's work on quantitative questions first.

What Quantitative Research Questions Do

Quantitative research questions address the:

- description of variables being investigated,

- measurement of relationships between (at least two) variables,

- differences between two or more groups' scores on a variable or variables, and so on.

They also clearly identify the sample that will be questioned. Most importantly, they use the same language for these elements as the research problem used. Your research question needs to cover all three items.