An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Adv Pract Oncol

- v.12(4); 2021 May

Quality Improvement Projects and Clinical Research Studies

Every day, I witness firsthand the amazing things that advanced practitioners and nurse scientists accomplish. Through the conduct of quality improvement (QI) projects and clinical research studies, advanced practitioners and nurse scientists have the opportunity to contribute exponentially not only to their organizations, but also towards personal and professional growth.

Recently, the associate editors and staff at JADPRO convened to discuss the types of articles our readership may be interested in. Since we at JADPRO believe that QI projects and clinical research studies are highly valuable methods to improve clinical processes or seek answers to questions, you will see that we have highlighted various QI and research projects within the Research and Scholarship column of this and future issues. There have also been articles published in JADPRO about QI and research ( Gillespie, 2018 ; Kurtin & Taher, 2020 ). As a refresher, let’s explore the differences between a QI project and clinical research.

Quality Improvement

As leaders in health care, advanced practitioners often conduct QI projects to improve their internal processes or streamline clinical workflow. These QI projects use a multidisciplinary team comprising a team leader as well as nurses, PAs, pharmacists, physicians, social workers, and program administrators to address important questions that impact patients. Since QI projects use strategic processes and methods to analyze existing data and all patients participate, institutional review board (IRB) approval is usually not needed. Common frameworks, such as Lean, Six Sigma, and the Model for Improvement can be used. An attractive aspect of QI projects is that these are generally quicker to conduct and report on than clinical research, and often with quantifiable benefits to a large group within a system ( Table 1 ).

Clinical Research

Conducting clinical research through an IRB-approved study is another area in which advanced practitioners and nurse scientists gain new knowledge and contribute to scientific evidence-based practice. Research is intended for specific groups of patients who are protected from harm through the IRB and ethical principles. Research can potentially benefit a larger group, but benefits to participants are often unknown during the study period.

Clinical research poses many challenges at various stages of what can be a lengthy process. First, the researcher conducts a review of the literature to identify gaps in existing knowledge. Then, the researcher must be diligent in their self-reflection (is this phenomenon worth studying?) and in developing the sampling and statistical methods to ensure validity and reliability of the research ( Higgins & Straub, 2006 ). A team of additional researchers and support staff is integral to completing the research and disseminating findings. A well-designed clinical trial is worth the time and effort it takes to answer important clinical questions.

So, as an advanced practitioner, would a QI project be better to conduct than a clinical research study? That depends. A QI project uses a specific process, measures, and existing data to improve outcomes in a specific group. A research study uses an IRB-approved study protocol, strategic methods, and generates new data to hopefully benefit a larger group.

In This Issue

Both QI projects and clinical research can provide evidence to base one’s interventions on and enhance the lives of patients in one way or another. I hope you will agree that this issue is filled with valuable information on a wide range of topics. In the following pages, you will learn about findings of a QI project to integrate palliative care into ambulatory oncology. In a phenomenological study, Carrasco explores patient communication preferences around cancer symptom reporting during cancer treatment.

We have two excellent review articles for you as well. Rogers and colleagues review the management of hematologic adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors, and Lemke reviews the evidence for use of ginseng in the management of cancer-related fatigue. In Grand Rounds, Flagg and Pierce share an interesting case of essential thrombocythemia in a 15-year-old, with valuable considerations in the pediatric population. May and colleagues review practical considerations for integrating biosimilars into clinical practice, and Moore and Thompson review BTK inhibitors in B-cell malignancies.

- Higgins P. A., & Straub A. J. (2006). Understanding the error of our ways: Mapping the concepts of validity and reliability . Nursing Outlook , 54 ( 1 ), 23–29. 10.1016/j.outlook.2004.12.004 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gillespie T. W. (2018). Do the right study: Quality improvement projects and human subject research—both valuable, simply different . Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology , 9 ( 5 ), 471–473. 10.6004/jadpro.2018.9.5.1 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kurtin S. E., & Taher R. (2020). Clinical trial design and drug approval in oncology: A primer for the advanced practitioner in oncology . Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology , 11 ( 7 ), 736–751. 10.6004/jadpro.2020.11.7.7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- HRP Staff Directory

- Office Hours

- Quality Improvement Project vs. Research

- Self Exempt & UROP

- Case Reports

- Commercial IRB Reliance Agreements

- National Cancer Institute Central IRB (CIRB) Independent Review Process

- UCI as the Reviewing IRB

- Submitting the Application

- Lead Researcher Eligibility

- Training & Education

- Ethical Guidelines, Regulations and Statutes

- Other Institutional Requirements

- Department of Defense Research Requirements

- Levels of Review

- Data Security

- Protected Health Information (HIPAA)

- European Union General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR)

- China’s Personal Information Protection Law

- Required Elements of Informed Consent

- Drafting the Informed Consent Form

- Consent and Non-English or Disabled Subjects

- Use Of Surrogate Consent In Research

- Vulnerable Populations

- Data and Safety Monitoring for Clinical Research

- Placebo-Controlled Studies

- Expanded Access to Unapproved Drugs or Biologics

- Right to Try: Unapproved Drugs or Biologics

- Use of Controlled Substances

- Expanded Access to Unapproved Medical Devices

- Humanitarian Use Devices

- Human Gene Transfer Research

- How To Register and Update Your Study

- Post-Review Responsibilities

Quality Improvement Projects vs Quality Improvement Research Activities

In general, a quality improvement (QI) project does not need to be submitted to the IRB. The comparison chart below is intended to help you determine whether an activity is a "Project or "Research"

EQUIP TIPS Additional Guidance!

Qi project vs. qi research, definitions.

Definitition

An activity that is specifically initiated with a goal of improving the performance of institutional practices in relationship to an established standard.

However, if a project was originally initiated as a local QI project but the findings are of interest and the project investigator chooses to expand the findings into a research study, IRB review would be required at that time.

QI Research

An activity that is initiated with a goal of improving the performance of institutional practices in relationship to an established standard , with the intent to contribute to generalizable knowledge (“widely applicable”)

Meets the definition of Human Subjects Research :

- Human Subjects

Core Elements

Core Elements

HIPAA Rule: the following activities are considered “ healthcare operations ” (they are not considered “research” ):

- Conducting quality assessment and improvement activities, including outcomes evaluation and development of clinical guidelines, if the obtaining of generalizable knowledge is not the primary purpose of studies resulting from the activities

- Population-based activities relating to improving health or reducing healthcare costs

- [Clinical] protocol development, case management and care coordination

Authorization:

- HIPAA Rule does not require a covered entity to secure individual authorization (nor a waiver) for use or disclosure of PHI for these activities, as long as the covered entity describes the activities in its Notice of Privacy Practices

- “Release to” section: UCI faculty/resident name

- “Purpose” section: QI activity publication

- the signed authorization should be uploaded and maintained in the patient’s record; note, the patient has the right to ask for a copy of the signed authorization form

- translated HIPAA Authorizations

Privacy and confidentiality: A QI activity retains the standard for ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the population and data being accessed and studied; also, review the above note regarding HIPAA Authorization

Intent: generate generalizable results

Additional risk or burden: the project includes risks or burdens beyond the standard of practice to make the results generalizable

Design: involves randomization or an element that may be considered less (or more) than standard of care

HIPAA Rule: requirements for waiving informed consent and/or waiving the requirements for documentation of informed consent must be met

Documentation

DOCUMENTATIAON

Documentation:

- Journals and conference platforms typically ask whether your project received an IRB review

- Recommendation: submission of a NHSR determination request and maintain the IRB email determination for the life of the project

- Submit a non-human subject research (NHSR) determination request via Kuali Research (KR) Protocols .

Publication:

- Publications must describe the activity as a “project” and NOT use the term "research" ; also, review the above note regarding HIPAA Authorization

IRB review: activities that meet the definition of Human Subjects Research require IRB review

- How to apply

Additonal Resources

- EQUIP-TIPS Quality Improvement Project vs. Research Guidance

- 45 CFR 46. 102(e)(1) : Federal Policy’s definition of Human Subject (v 2018)

- 45 CFR 46. 102(l) : Federal Policy’s definition of Research (v 2018)

- 45 CFR 46 (v 2018): Preamble for Quality Improvement Activities

- IRB Ethics & Human Research, Vol 39(3), May-June 2017, Pages 1-10

- 45 CFR 164.506 (2013): Definition of Health Care Operations

- IRB Ethics & Human Research, Vol 35(5), September-October 2013, Pages 1-8

- Research Compliance Professional’s Handbook, 2nd Edition, 2013, Chapter 8, Page 79

- OHRP Quality Improvement Activities FAQ (2010)

- Institutional Review Board, Management and Function, 2nd Edition, 2006, Chapter 4-3, Pages 102-103

- 2005 California Senate Bill 13 (SB 13) (*when applicable)

- Example of a published QI Project

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to get started in...

How to get started in quality improvement

Linked opinion.

The benefits of QI are numerous and the challenges worth overcoming

Read the full collection

- Related content

- Peer review

- Bryan Jones , improvement fellow 1 ,

- Emma Vaux , consultant nephrologist 2 ,

- Anna Olsson-Brown , research fellow 3

- 1 The Health Foundation, London, UK

- 2 Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust. Reading, UK

- 3 Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, The Institute of Translational Medicine, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

- Correspondence to B Jones bryan.jones{at}health.org.uk

What you need to know

Participation in quality improvement can help clinicians and trainees improve care together and develop important professional skills

Effective quality improvement relies on collaborative working with colleagues and patients and the use of a structured method

Enthusiasm, perseverance, good project management skills, and a willingness to explain your project to others and seek their support are key skills

Quality improvement ( box 1 ) is a core component of many undergraduate and postgraduate curriculums. 1 2 3 4 5 Numerous healthcare organisations, 6 professional regulators, 7 and policy makers 8 recognise the benefits of training clinicians in quality improvement.

Defining quality improvement 1

Quality improvement aims to make a difference to patients by improving safety, effectiveness, and experience of care by:

Using understanding of our complex healthcare environment

Applying a systematic approach

Designing, testing, and implementing changes using real time measurement for improvement

Engaging in quality improvement enables clinicians to acquire, assimilate, and apply important professional capabilities 7 such as managing complexity and training in human factors. 1 For clinical trainees, it is a chance to improve care 9 ; develop leadership, presentation, and time management skills to help their career development 10 ; and build relationships with colleagues in organisations that they have recently joined. 11 For more experienced clinicians, it is an opportunity to address longstanding concerns about the way in which care processes and systems are delivered, and to strengthen their leadership for improvement skills. 12

The benefits to patients, clinicians, and healthcare providers of engaging in quality improvement are considerable, but there are many challenges involved in designing, delivering, and sustaining an improvement intervention. These range from persuading colleagues that there is a problem that needs to be tackled, through to keeping them engaged once the intervention is up and running as other clinical priorities compete for their attention. 13 You are also likely to have competing priorities and will need support to make time for quality improvement. The organisational culture, such as the extent to which clinicians are able to question existing practice and try new ideas, 14 15 16 also has an important bearing on the success of the intervention.

This article describes the skills, knowledge, and support needed to get started in quality improvement and deliver effective interventions.

What skills do you need?

Enthusiasm, optimism, curiosity, and perseverance are critical in getting started and then in helping you to deal with the challenges you will inevitably face on your improvement journey.

Relational skills are also vital. At its best quality improvement is a team activity. The ability to collaborate with different people, including patients, is vital for a project to be successful. 17 18 You need to be willing to reach out to groups of people that you may not have worked with before, and to value their ideas. 19 No one person has the skills or knowledge to come up with the solution to a problem on their own.

Learning how systems work and how to manage complexity is another core skill. 20 An ability to translate quality improvement approaches and methods into practice ( box 2 ), coupled with good project and time management skills, will help you design and implement a robust project plan. 27

Quality improvement approaches

Healthcare organisations use a range of improvement methods, 21 22 such as the Model for Improvement , where changes are tested in small cycles that involve planning, doing, studying, and acting (PDSA), 23 and Lean , which focuses on continually improving processes by removing waste, duplication, and non-value adding steps. 24 To be effective, such methods need to be applied consistently and rigorously, with due regard to the context. 25 In using PDSA cycles, for example, it is vital that teams build in sufficient time for planning and reflection, and do not focus primarily on the “doing.” 26

Equally important is an understanding of the measurement for improvement model, which involves the gradual refinement of your intervention based on repeated tests of change. The aim is to discover how to make your intervention work in your setting, rather than to prove it works, so useful data, not perfect data, are needed. 28 29 Some experience of data collection and analysis methods (including statistical analysis tools such as run charts and statistical process control) is useful, but these will develop with increasing experience. 30 31

Most importantly, you need to enjoy the experience. It is rare that a clinician can institute real, tangible change, but with quality improvement this is a real possibility, which is both empowering and satisfying. Finally, don’t worry about what you don’t know. You will learn by doing. Many skills needed to implement successful quality improvement will be developed as you go; this is a fundamental feature of quality improvement.

How do you get started?

The first step is to recruit your improvement team. Start with colleagues and patients, 32 but also try to bring in people from other professions, including non-clinical staff. You need a blend of skills and perspectives in your team. Find a colleague experienced in quality improvement who is willing to mentor or supervise you.

Next, identify a problem collaboratively with your team. Use data to help with this (eg, clinical audits, registries of data on patients’ experiences and outcomes, and learning from incidents and complaints) ( box 3 ). Take time to understand what might be causing the problem. There are different techniques to help you (process mapping, five whys, appreciative inquiry). 35 36 37 Think about the contextual factors that are contributing to the problem (eg, the structure, culture, politics, capabilities and resources of your organisation).

Clinical audit and quality improvement

Quality improvement is an umbrella term under which many approaches sit, clinical audit being one. 33 Clinical audit is commonly used by trainees to assess clinical effectiveness. Confusion of audit as both a term for assurance and improvement has perhaps limited its potential, with many audits ending at the data collection stage and failing to lead to improvement interventions. Learning from big datasets such as the National Clinical Audits in the UK is beginning to shift the focus to a quality improvement approach that focuses on identifying and understanding unwanted variation in the local context; developing and testing possible solutions, and moving from one-off change to multiple cycles of change. 34

Next, develop your aim using the SMART framework: Specific (S), Measurable (M), Achievable (A), Realistic (R), and Timely (T). 38 This allows you to assess the scale of the intervention and to pare it down if your original idea is too ambitious. Aligning your improvement aim with the priorities of the organisation where you work will help you to get management and executive support. 39

Having done this, map those stakeholders who might be affected by your intervention and work out which ones you need to approach, and how to sell it to them. 40 Take the time to talk to them. It will be appreciated and increases the likelihood of buy in, without which your quality improvement project is likely to fail irrespective of how good your idea is. You need to be clear in your own mind about the reasons you think it is important. Developing an “elevator pitch” based on your aims is a useful technique to persuade others, 38 remembering different people are hooked in for different reasons.

The intervention will not be perfect first time. Expect a series of iterative changes in response to false starts and obstacles. Measuring the impact of your intervention will enable you to refine it. 28 Time invested in all these aspects will improve your chances of success.

Right from the start, think about how improvement will be embedded. Attention to sustainability will mean that when you move to your next job your improvement efforts, and those of others, and the impact you have collectively achieved will not be lost. 41 42

What support is needed?

You need support from both your organisation and experienced colleagues to translate your skills into practice. Here are some steps you can take to help you make the most of your skills:

Find the mentor or supervisor who will help identify and support opportunities for you. Signposting and introduction to those in an organisation who will help influence (and may hinder) your quality improvement project is invaluable

Use planning and reporting tools to help manage your project, such as those in NHS Improvement’s project management framework 27

Identify if your local quality improvement or clinical audit team may be a source of support and useful development resource for you rather than just a place to register a project. Most want to support you.

Determine how you might access (or develop your own) local peer to peer support networks, coaching, and wider improvement networks (eg, NHS networks; Q network 43 44 )

Use quality improvement e-learning platforms such as those provided by Health Education England or NHS Education for Scotland to build your knowledge 45 46

Learn through feedback and assessment of your project (eg, via the QIPAT tool 47 or a multi-source feedback tool. 48 49

Quality improvement approaches are still relatively new in the education of healthcare professionals. Quality improvement can give clinicians a more productive, empowering, and educational experience. Quality improvement projects allow clinicians, working within a team, to identify an issue and implement interventions that can result in true improvements in quality. Projects can be undertaken in fields that interest clinicians and give them transferable skills in communication, leadership, project management, team working, and clinical governance. Done well, quality improvement is a highly beneficial, positive process which enables clinicians to deliver true change for the benefit of themselves, their organisations, and their patients.

Quality improvement in action: three doctors and a medical student talk about the challenges and practicalities of quality improvement

This box contains four interviews by Laura Nunez-Mulder with people who have experience in quality improvement.

Alex Thompson, medical student at the University of Cambridge, is in the early stages of his first quality improvement project

We are aiming to improve identification and early diagnosis of aortic dissections in our hospital. Our supervising consultant suspects that the threshold for organising computed tomography angiography for a suspected aortic dissection is too high, so to start with, my student colleague and I are finding out what proportion of CT angiograms result in a diagnosis of aortic dissection.

I fit the project around my studies by working on it in small chunks here and there. You have to be very self motivated to see a project through to the end.

Anna Olsson-Brown, research fellow at the University of Liverpool, engaged in quality improvement in her F1 year, and has since supported junior doctors to do the same. This extract is adapted from her BMJ Opinion piece ( https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/ )

Working in the emergency department after my F1 job in oncology, I noticed that the guidelines on neutropenic sepsis antibiotics were relatively unknown and even less frequently implemented. A colleague and I devised a neutropenic sepsis pathway for oncology patients in the emergency department including an alert label for blood tests. The pathway ran for six months and there was some initial improvement, but the benefit was not sustained after we left the department.

As an ST3, I mentored a junior doctor whose quality improvement project led to the introduction of a syringe driver prescription sticker that continues to be used to this day.

My top tips for those supporting trainees in quality improvement:

Make sure the project is sufficiently narrow to enable timely delivery

Ensure regular evaluation to assess impact

Support trainees to implement sustainable pathways that do not require their ongoing input.

Amar Puttanna, consultant in diabetes and endocrinology at Good Hope Hospital, describes a project he carried out as a chief registrar of the Royal College of Physicians

The project of which I am proudest is a referral service we launched to review medication for patients with diabetes and dementia. We worked with practitioners on the older adult care ward, the acute medical unit, the frailty service, and the IT teams, and we promoted the project in newsletters at the trust and the Royal College of Physicians.

The success of the project depended on continuous promotion to raise awareness of the service because junior doctors move on frequently. Activity in our project reduced after I left the trust, though it is still ongoing and won a Quality in Care Award in November 2018.

Though this project was a success, not everything works. But even the projects that fail contain valuable lessons.

Mark Taubert, consultant in palliative medicine and honorary senior lecturer for Cardiff University School of Medicine, launched the TalkCPR project

Speaking to people with expertise in quality improvement helped me to narrow my focus to one question: “Can videos be used to inform both staff and patients/carers about cardiopulmonary resuscitation and its risks in palliative illness?” With my team I created and evaluated TalkCPR, an online resource that has gone on to win awards (talkcpr.wales).

The most challenging aspect was figuring out which tools might get the right information from any data I collected. I enrolled on a Silver Improving Quality Together course and joined the Welsh Bevan Commission, where I learned useful techniques such as multiple PDSA (plan, do, study, act) cycles, driver diagrams, and fishbone diagrams.

Education into practice

In designing your next quality improvement project:

What will you do to ensure that you understand the problem you are trying to solve?

How will you involve your colleagues and patients in your project and gain the support of managers and senior staff?

What steps will you take right from the start to ensure that any improvements made are sustained?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

The authors have drawn on their experience both in partnering with patients in the design and delivery of multiple quality improvement activities and in participating in the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges Training for Better Outcomes Task and Finish Group 1 in which patients were involved at every step. Patients were not directly involved in writing this article.

Sources and selection material

Evidence for this article was based on references drawn from authors’ academic experience in this area, guidance from organisations involved in supporting quality improvement work in practice such as NHS Improvement, The Health Foundation, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and authors’ experience of working to support clinical trainees to undertake quality improvement.

Competing interests: The BMJ has judged that there are no disqualifying financial ties to commercial companies.

The authors declare the following other interests: none.

Further details of The BMJ policy on financial interests is here: https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-authors/forms-policies-and-checklists/declaration-competing-interests

Contributors: BJ produced the initial outline after discussions with EV and AOB. AO-B produced a first complete draft, which EV reworked and expanded. BJ then edited and finalised the text, which was approved by EV and AO-B. The revisions in the resubmitted version were drafted by BJ and edited and approved by EV and AO-B. BJ is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Provenance and peer review: This article is part of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on ideas generated by a joint editorial group with members from the Health Foundation and The BMJ, including a patient/carer. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication. Open access fees and The BMJ’s quality improvement editor post are funded by the Health Foundation.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

- ↵ Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AoMRC). Quality improvement: training for better outcomes. March 2016. http://www.aomrc.org.uk/reports-guidance/quality-improvement-training-better-outcomes/

- Bethune R ,

- Woodhead P ,

- Van Hamel C ,

- Teigland CL ,

- Blasiak RC ,

- Wilson LA ,

- Meyerhoff KL ,

- ↵ Jones B, Woodhead T. Building the foundations for improvement—how five UK trusts built quality improvement capability at scale within their organisations. The Health Foundation. February 2015. https://www.health.org.uk/publication/building-foundations-improvement

- ↵ General Medical Council (GMC). Generic professional capabilities framework. May 2017. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/generic-professional-capabilities-framework-0817_pdf-70417127.pdf

- ↵ NHS improvement (NHSI). Developing people—improving care A national framework for action on improvement and leadership development in NHS-funded services. December 2016. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/developing-people-improving-care/

- ↵ The Health Foundation. Involving junior doctors in quality improvement: evidence scan. September 2011. https://www.health.org.uk/publication/involving-junior-doctors-quality-improvement

- ↵ Zarkali A, Acquaah F, Donaghy G, et al. Trainees leading quality improvement. A trainee doctor’s perspective on incorporating quality improvement in postgraduate medical training. Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management. March 2016. https://www.fmlm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/content/resources/attachments/FMLM%20TSG%20Think%20Tank%20Trainees%20leading%20quality%20improvement.pdf

- Hillman T ,

- ↵ Bohmer R. The instrumental value of medical leadership: Engaging doctors in improving services. The King’s Fund. 2012. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/instrumental-value-medical-leadership-richard-bohmer-leadership-review2012-paper.pdf

- ↵ Dixon-Woods M, McNicol S, Martin G. Ten challenges in improving quality in healthcare: lessons from the Health Foundation's programme evaluations and relevant literature. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;1e9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000760 OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- Brault MA ,

- Linnander EL ,

- Carroll JS ,

- Edmondson AC

- Mannion R ,

- Richter A ,

- McPherson K ,

- Headrick L ,

- ↵ Lucas B, Nacer H. The habits of an improver. Thinking about learning for improvement in health care. The Health Foundation. October 2015. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/TheHabitsOfAnImprover.pdf

- Greenhalgh T

- ↵ The Health Foundation. Quality Improvement made simple: what everyone should know about quality improvement. The Health Foundation. 2013. https://www.health.org.uk/publication/quality-improvement-made-simple

- ↵ Boaden R, Harvey G, Moxham C, Proudlove N. Quality improvement: theory and practice in healthcare. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. 2008. https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/publication/quality-improvement-theory-practice-in-healthcare/

- ↵ Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). IHI resources: How to improve. IHI. 2018 http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx

- ↵ Lean Enterprise Institute. What is lean? Lean Enterprise Institute. 2018. https://www.lean.org/WhatsLean/

- ↵ Bate P, Robert G, Fulop N, Øvretveit J, Dixon-Woods M. Perspectives on context. A selection of essays considering the role of context in successful quality improvement. The Health Foundation. 2014. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/PerspectivesOnContext_fullversion.pdf

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools. Project management an overview. September 2017. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/project-management-overview/

- ↵ Clarke J, Davidge M, James L. The how-to guide for measurement for improvement. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2009. https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/How-to-Guide-for-Measurement-for-Improvement.pdf

- Nelson EC ,

- Splaine ME ,

- Batalden PB ,

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools. Run charts. January 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/run-charts/

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools. Statistical process control tool. May 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/statistical-process-control-tool/

- Cornwell J ,

- Purushotham A ,

- Sturmey G ,

- Burgess R ,

- ↵ Royal College of Physicians. Unlocking the potential. Supporting doctors to use national clinical audit to drive improvement. April 2018. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/unlocking-potential-supporting-doctors-use-national-clinical-audit-drive

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools: conventional process mapping. January 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/process-mapping-conventional-model/

- ↵ Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) 5 Whys: Finding the root cause. IHI tool. 2018. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/5-Whys-Finding-the-Root-Cause.aspx

- Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) Appreciative Inquiry Resource Pack

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools: Developing your aims statement. January 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/aims-statement-development/

- Pannick S ,

- Sevdalis N ,

- Athanasiou T

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools: Stakeholder Analysis. January 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2169/stakeholder-analysis.pdf

- ↵ Maher L, Gustafson D, Evans A. Sustainability model and guide. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. February 2010. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160805122935/http:/www.nhsiq.nhs.uk/media/2757778/nhs_sustainability_model_-_february_2010_1_.pdf

- Networks NHS

- ↵ Community Q. The Health Foundation. 2018. https://q.health.org.uk/

- ↵ Health Education England. e-learning for healthcare. https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/research-audit-and-quality-improvement/

- ↵ Scotland Quality Improvement Hub NHS. QI e-learning. http://www.qihub.scot.nhs.uk/education-and-learning-xx/qi-e-learning.aspx

- ↵ Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Quality Improvement Assessment Tool (QIPAT). 2017. https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/documents/may-2012-quality-improvement-assessment-tool-qipat

- ↵ Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Quality improvement assessment tool. May 2017. https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/documents/may-2012-quality-improvement-assessment-tool-qipat

- ↵ Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Multi-source feedback. August 2014. https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/documents/multi-source-feedback-august-2014 .

How to Begin a Quality Improvement Project

Affiliations.

- 1 Division of Nephrology, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- 2 Keenan Research Center, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- 3 Division of Nephrology, University Health Network, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- 4 Division of Nephrology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California; and.

- 5 Department of Nephrology, Humber River Regional Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- 6 Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- 7 Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- PMID: 27016497

- PMCID: PMC4858490

- DOI: 10.2215/CJN.11491015

Quality improvement involves a combined effort among health care staff and stakeholders to diagnose and treat problems in the health care system. However, health care professionals often lack training in quality improvement methods, which makes it challenging to participate in improvement efforts. This article familiarizes health care professionals with how to begin a quality improvement project. The initial steps involve forming an improvement team that possesses expertise in the quality of care problem, leadership, and change management. Stakeholder mapping and analysis are useful tools at this stage, and these are reviewed to help identify individuals who might have a vested interest in the project. Physician engagement is a particularly important component of project success, and the knowledge that patients/caregivers can offer as members of a quality improvement team should not be overlooked. After a team is formed, an improvement framework helps to organize the scientific process of system change. Common quality improvement frameworks include Six Sigma, Lean, and the Model for Improvement. These models are contrasted, with a focus on the Model for Improvement, because it is widely used and applicable to a variety of quality of care problems without advanced training. It involves three steps: setting aims to focus improvement, choosing a balanced set of measures to determine if improvement occurs, and testing new ideas to change the current process. These new ideas are evaluated using Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles, where knowledge is gained by testing changes and reflecting on their effect. To show the real world utility of the quality improvement methods discussed, they are applied to a hypothetical quality improvement initiative that aims to promote home dialysis (home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis). This provides an example that kidney health care professionals can use to begin their own quality improvement projects.

Keywords: Delivery of Health Care; Hemodialysis; Home; Humans; Leadership; Quality Improvement; Total Quality Management; chronic kidney disease; clinical nephrology; end stage kidney disease; renal dialysis.

Copyright © 2016 by the American Society of Nephrology.

- Hemodialysis, Home / standards*

- Models, Organizational

- Nephrology / standards*

- Organizational Innovation

- Outcome and Process Assessment, Health Care

- Program Development / methods*

- Quality Improvement / organization & administration*

- Total Quality Management*

Grants and funding

- K24 DK085446/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Quality Improvement Activities FAQs

How does hhs view quality improvement activities in relation to the regulations for human research subject protections.

Protecting human subjects during research activities is critical and has been at the forefront of HHS activities for decades. In addition, HHS is committed to taking every appropriate opportunity to measure and improve the quality of care for patients. These two important goals typically do not intersect, since most quality improvement efforts are not research subject to the HHS protection of human subjects regulations. However, in some cases quality improvement activities are designed to accomplish a research purpose as well as the purpose of improving the quality of care, and in these cases the regulations for the protection of subjects in research (45 CFR part 46) may apply.

To determine whether these regulations apply to a particular quality improvement activity, the following questions should be addressed in order:

- does the activity involve research ( 45 CFR 46.102(d) );

- does the research activity involve human subjects ( 45 CFR 46.102(f) );

- does the human subjects research qualify for an exemption ( 45 CFR 46.101(b) ); and

- is the non-exempt human subjects research conducted or supported by HHS or otherwise covered by an applicable FWA approved by OHRP.

For those quality improvement activities that are subject to these regulations, the regulations provide great flexibility in how the regulated community can comply. Other laws or regulations may apply to quality improvement activities independent of whether the HHS regulations for the protection of human subjects in research apply.

Do the HHS regulations for the protection of human subjects in research (45 CFR part 46) apply to quality improvement activities conducted by one or more institutions whose purposes are limited to: (a) implementing a practice to improve the quality of patient care, and (b) collecting patient or provider data regarding the implementation of the practice for clinical, practical, or administrative purposes?

No, such activities do not satisfy the definition of “research” under 45 CFR 46.102(d) , which is “...a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge...” Therefore the HHS regulations for the protection of human subjects do not apply to such quality improvement activities, and there is no requirement under these regulations for such activities to undergo review by an IRB, or for these activities to be conducted with provider or patient informed consent.

Examples of implementing a practice and collecting patient or provider data for non-research clinical or administrative purposes include:

- A radiology clinic uses a database to help monitor and forecast radiation dosimetry. This practice has been demonstrated to reduce over-exposure incidents in patients having multiple procedures. Patient data are collected from medical records and entered into the database. The database is later analyzed to determine if over-exposures have decreased as expected.

- A group of affiliated hospitals implements a procedure known to reduce pharmacy prescription error rates, and collects prescription information from medical charts to assess adherence to the procedure and determine whether medication error rates have decreased as expected.

- A clinic increasingly utilized by geriatric patients implements a widely accepted capacity assessment as part of routine standard of care in order to identify patients requiring special services and staff expertise. The clinic expects to audit patient charts in order to see if the assessments are performed with appropriate patients, and will implement additional in-service training of clinic staff regarding the use of the capacity assessment in geriatric patients if it finds that the assessments are not being administered routinely.

Do quality improvement activities fall under the HHS regulations for the protection of human subjects in research (45 CFR part 46) if their purposes are limited to: (a) delivering healthcare, and (b) measuring and reporting provider performance data for clinical, practical, or administrative uses?

No, such quality improvement activities do not satisfy the definition of “research” under 45 CFR 46.102(d), which is “…a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge…” Therefore the HHS regulations for the protection of human subjects do not apply to such quality improvement activities, and there is no requirement under these regulations for such activities to undergo review by an IRB, or for these activities to be conducted with provider or patient informed consent.

The clinical, practical, or administrative uses for such performance measurements and reporting could include, for example, helping the public make more informed choices regarding health care providers by communicating data regarding physician-specific surgical recovery data or infection rates. Other practical or administrative uses of such data might be to enable insurance companies or health maintenance organizations to make higher performing sites preferred providers, or to allow other third parties to create incentives rewarding better performance.

Can I analyze data that are not individually identifiable, such as medication databases stripped of individual patient identifiers, for research purposes without having to apply the HHS protection of human subjects regulations?

Yes, whether or not these activities are research, they do not involve “human subjects.” The regulation defines a “human subject” as “a living individual about whom an investigator conducting research obtains (1) data through intervention or interaction with the individual, or (2) identifiable private information….Private information must be individually identifiable (i.e., the identity of the subject is or may readily be ascertained by the investigator or associated with the information) in order for obtaining the information to constitute research involving human subjects.” Thus, if the research project includes the analysis of data for which the investigators cannot readily ascertain the identity of the subjects and the investigators did not obtain the data through an interaction or intervention with living individuals for the purposes of the research, the analyses do not involve human subjects and do not have to comply with the HHS protection of human subjects regulations.

(See OHRP Guidance on Research Involving Coded Private Information or Biological Specimens , October 2008; available at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/ohrp/policy/cdebiol.pdf .)

Are there types of quality improvement efforts that are considered to be research that are subject to HHS human subjects regulations?

Yes, in certain cases, a quality improvement project may constitute non-exempt human subjects research conducted or supported by HHS or otherwise covered by an applicable FWA. For example, if a project involves introducing an untested clinical intervention for purposes which include not only improving the quality of care but also collecting information about patient outcomes for the purpose of establishing scientific evidence to determine how well the intervention achieves its intended results, that quality improvement project may also constitute nonexempt human subjects research under the HHS regulations.

If I plan to carry out a quality improvement project and publish the results, does the intent to publish make my quality improvement project fit the regulatory definition of research?

No, the intent to publish is an insufficient criterion for determining whether a quality improvement activity involves research. The regulatory definition under 45 CFR 46.102(d) is “ Research means a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge.” Planning to publish an account of a quality improvement project does not necessarily mean that the project fits the definition of research; people seek to publish descriptions of nonresearch activities for a variety of reasons, if they believe others may be interested in learning about those activities. Conversely, a quality improvement project may involve research even if there is no intent to publish the results.

Does a quality improvement project that involves research need to be reviewed by an IRB?

Yes, in some cases. IRB review is needed if the research involves human subjects, is not exempt, and is conducted or supported by HHS or otherwise covered by an applicable FWA.

For more information see exempt categories .

Does IRB review of a quality improvement project that is also non-exempt human subjects research always need to be carried out at a convened IRB meeting?

No, if the human subjects research activity involves no more than minimal risk and fits one or more of the categories of research eligible for expedited review, the IRB chair or another member designated by the IRB chair may conduct the review.

The categories of research eligible for expedited review are available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/categories-of-research-expedited-review-procedure-1998/index.html .

If a quality improvement project involves non-exempt research with human subjects, do I always need to obtain informed consent from all subjects (patients and/or providers) involved in the research?

No, the HHS regulations protecting human subjects allow an IRB to waive the requirements for obtaining informed consent of the subjects of the research when

- the risk to the subjects is minimal,

- subjects’ rights and welfare will not be adversely affected by the waiver,

- conducting the research without the waiver is not practicable, and

- if appropriate, subjects are provided with additional pertinent information after their participation ( 45 CFR 46.116(d) ).

Other applicable regulations or laws may require the informed consent of individuals in such projects independent of the HHS regulations for the protection of human subjects in research.

If a quality improvement project is human subjects research requiring IRB review, do I need to obtain separate IRB approval from every institution engaged in the project?

No, not if certain conditions are met. The HHS protection of human subjects regulations allow one IRB to review and approve research that will be conducted at multiple institutions. An institution has the option of relying upon IRB review from another institution by designating that IRB on its FWA and submitting the revised FWA to OHRP, and having an IRB Authorization Agreement with the other institution.

See IRBs and Assurances for information on FWAs and IRB Authorization Agreements.

- Open access

- Published: 03 June 2024

Continue nursing education: an action research study on the implementation of a nursing training program using the Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory

- MingYan Shen 1 , 2 &

- ZhiXian Feng 1 , 2

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 610 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

To address the gap in effective nursing training for quality management, this study aims to implement and assess a nursing training program based on the Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory, utilizing action research to enhance the practicality and effectiveness of training outcomes.

The study involved the formation of a dedicated training team, with program development informed by an extensive situation analysis and literature review. Key focus areas included motivation to transfer, learning environment, and transfer design. The program was implemented in a structured four-step process: plan, action, observation, reflection.

Over a 11-month period, 22 nurses completed 14 h of theoretical training and 18 h of practical training with a 100% attendance rate and 97.75% satisfaction rate. The nursing team successfully led and completed 22 quality improvement projects, attaining a practical level of application. Quality management implementation difficulties, literature review, current situation analysis, cause analysis, formulation of plans, implementation plans, and report writing showed significant improvement and statistical significance after training.

The study confirms the efficacy of action research guided by Holton’s model in significantly enhancing the capabilities of nursing staff in executing quality improvement projects, thereby improving the overall quality of nursing training. Future research should focus on refining the training program through long-term observation, developing a multidimensional evaluation index system, exploring training experiences qualitatively, and investigating the personality characteristics of nurses to enhance training transfer effects.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The “Medical Quality Management Measures“ [ 1 ] and “Accreditation Standards for Tertiary Hospitals (2020 Edition)” [ 2 ] both emphasize the importance of using quality management tools in medical institutions to carry out effective quality management [ 3 ]. However, there is a notable gap in translating theoretical training into effective, practical application in clinical settings [ 4 ]. This gap is further highlighted in the context of healthcare quality management, as evidenced in studies [ 5 ] which demonstrate the universality of these challenges across healthcare systems worldwide.

Addressing this issue, contemporary literature calls for innovative and effective training methods that transition from passive knowledge acquisition to active skill application [ 6 ]. The Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory [ 7 ] provides a framework focusing on key factors such as motivation, learning environment, and transfer design [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This study aims to implement a nursing training program based on the Holton model, using an action research methodology to bridge the theoretical-practical gap in nursing education.

Quality management training for clinical nurses has predominantly been characterized by short-term theoretical lectures, a format that often fails to foster deep engagement and lasting awareness among nursing personnel [ 10 ]. The Quality Indicator Project in Taiwan’s nursing sector, operational for over a decade, demonstrates the effective use of collective intelligence and scientific methodologies to address these challenges [ 11 ]. The proposed study responds to the need for training programs that not only impart knowledge but also ensure the practical application of skills in real-world nursing settings, thereby contributing to transformative changes within the healthcare system [ 12 ].

In April 2021, the Nursing Education Department of our hospital launched a quality improvement project training program for nurses. The initiation of this study is underpinned by the evident disconnect between theoretical training and the practical challenges nurses face in implementing quality management initiatives, a gap also identified in the work [ 13 ]. By exploring the efficacy of the Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory, this study seeks to enhance the practical application of training and significantly contribute to the field of nursing education and quality management in healthcare.

Developing a nursing training program with the Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory

Establishing a research team and assigning roles.

There are 10 members in the group who serve as both researchers and participants, aiming to investigate training process issues and solutions. The roles within the group are as follows: the deputy dean in charge of nursing is responsible for program review and organizational support, integrating learning transfer principles in different settings [ 14 ]; the deputy director of the Nursing Education Department handles the design and implementation of the training program, utilizing double-loop learning for training transfer [ 15 ]; the deputy director of the Nursing Department oversees quality control and project evaluation, ensuring integration of evidence-based practices and technology [ 16 ] and the deputy director of the Quality Management Office provides methodological guidance. The remaining members consist of 4 faculty members possessing significant university teaching experience and practical expertise in quality control projects, and 2 additional members who are jointly responsible for educational affairs, data collection, and analysis. Additionally, to ensure comprehensive pedagogical guidance in this training, professors specializing in nursing pedagogy have been specifically invited to provide expertise on educational methodology.

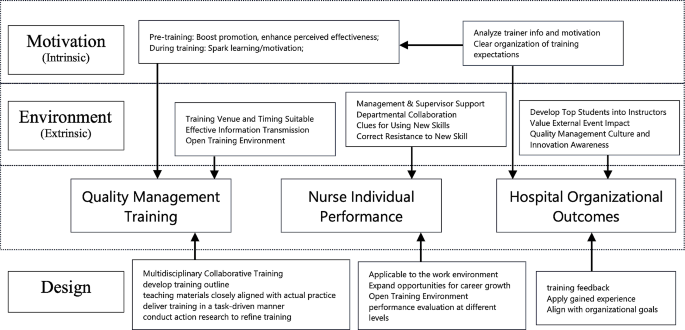

Current situation survey

Based on the Holton Learning Transfer System Inventory (refer to Fig. 1 ), the appropriate levels of Motivation to Improve Work Through Learning (MTIWL), learning environment, and transfer design are crucial in facilitating changes in individual performance, thereby influencing organizational outcomes [ 17 , 18 ]. Motivation to Improve Work Through Learning (MTIWL) is closely linked to expectation theory, fairness theory, and goal-setting theory, significantly impacting the positive transfer of training [ 19 ]. Learning environment encompasses environmental factors that either hinder or promote the application of learned knowledge in actual work settings [ 20 ]. Transfer design, as a pivotal component, includes training program design and organizational planning.

To conduct the survey, the research team retrieved 26 quality improvement reports from the nursing quality information management system, which were generated by nursing units in 2020. A checklist was formulated, and a retrospective evaluation was conducted across eight aspects, namely, team participation, topic selection feasibility, method accuracy, indicator scientificity, program implementation rate, effect maintenance, and promotion and application. Methods employed in the evaluation process included report analysis, on-site tracking, personnel interviews, and data review within the quality information management system [ 21 ]. From the perspective of motivation [ 22 ], learning environment [ 23 ], and transfer design, a total of 14 influencing factors were identified. These factors serve as a reference for designing the training plan and encompass the following aspects: lack of awareness regarding importance, low willingness to participate in training, unclear understanding of individual career development, absence of incentive mechanisms, absence of a scientific training organization model, lack of a training quality management model, inadequate literature retrieval skills and support, insufficient availability of practical training materials and resources, incomplete mastery of post-training methods, lack of cultural construction plans, suboptimal communication methods and venues, weak internal organizational atmosphere, inadequate leadership support, and absence of platforms and mechanisms for promoting and applying learned knowledge.

Learning Transfer System Inventory

Development of the training program using the 4W1H approach

Drawing upon Holton’s Learning Transfer System Inventory and the hospital training transfer model diagram, a comprehensive training outline was formulated for the training program [ 24 , 25 ]. The following components were considered:

(1) Training Participants (Who): The training is open for voluntary registration to individuals with an undergraduate degree or above, specifically targeting head nurses, responsible team leaders, and core members of the hospital-level nursing quality control team. Former members who have participated in quality improvement projects such as Plan-Do-Check-Act Circle (PDCA) or Quality control circle (QCC) are also eligible.

(2) Training Objectives (Why): At the individual level, the objectives include enhancing the understanding of quality management concepts, improving the cognitive level and application abilities of project improvement methods, and acquiring the necessary skills for nursing quality improvement project. At the team level, the aim is to enhance effective communication among team members and elevate the overall quality of communication. Moreover, the training seeks to facilitate collaborative efforts in improving the existing nursing quality management system and processes. At the operational level, participants are expected to gain the competence to design, implement, and manage nursing quality improvement project initiatives. Following the training, participants will lead and successfully complete a nursing quality improvement project, which will undergo a rigorous audit.

(3) Training Duration (When): The training program spans a duration of 11 months.

(4) Training Content (What): The program consists of 14 h of theoretical courses and 18 h of practical training sessions, as detailed in Table 1 .

(5) Quality Management Approach (How): To ensure quality throughout the training process, two team members are assigned to monitor the entire training journey. This encompasses evaluating whether quality awareness education, quality management knowledge, and professional skills training are adequately covered. Additionally, attention is given to participants’ learning motivation, the emphasis placed on active participation in training methods, support from hospital management and relevant departments, as well as participants’ satisfaction and assessment results. Please refer to Fig. 2 for a visual representation.

In-house training model from Holton Learning Transfer

Implementation of the nursing project training program using the action research method

The first cycle (april 2021).

In the initial cycle, a total of 22 nurses were included as training participants after a self-registration process and qualification review. The criteria used to select these participants, elaborated in Section Development of the training program using the 4W1H approach, ‘Development of the Training Program,’ were meticulously crafted to capture a broad spectrum of experience, expertise, and functional roles within our hospital’s nursing staff. The primary focus was to investigate their learning motivation. The cycle comprised the following key activities:

(1) Training Objectives: The focus was on understanding the learning motivation of the participating nurses.

(2) Theoretical Training Sessions: A total of 7 theoretical training sessions, spanning 14 class hours, were completed. The contents covered various aspects, including an overview of nursing quality improvement projects, methods for selecting project topics, common tools used in nursing quality improvement projects, effective leadership strategies to promote project practices, literature retrieval and evaluation methods, formulation and promotion of project plans, and writing project reports. Detailed course information, including the title, content, and class hours, is listed in Table 1 . At the end of each training session, a course satisfaction survey was conducted.

(3) Assessment and Reporting: Following the completion of the 7 training sessions, a theoretical assessment on quality management knowledge was conducted. Additionally, nurses were organized to present their plans for special projects to be carried out during the training. Several issues were identified during this cycle:

Incomplete Literature Review Skills: Compared to other quality control tools, nursing quality improvement project places more emphasis on the scientific construction of project plans. The theoretical evaluation and interviews with nurses highlighted the incomplete and challenging nature of their literature review skills.

Insufficient Leadership: Among the participants, 6 individuals were not head nurses, which resulted in a lack of adequate leadership for their respective projects.

Learning environment and Support: The learning environment, as well as the support from hospital management and relevant departments, needed to be strengthened.

Second cycle (may-october 2021)

In response to the issues identified during the first cycle, our approach in the second cycle was both corrective and adaptive, focusing on immediate issues while also setting the stage for addressing any emerging challenges. The team members actively implemented improvements during the second cycle. The key actions taken were as follows:

(1) Establishing an Enabling Organizational Environment: The quality management department took the lead, and multiple departments collaborated in conducting the “Hospital Safety and Quality Red May” activity. This initiative aimed to enhance the overall quality improvement atmosphere within the hospital. Themed articles were also shared through the hospital’s WeChat public account.

(2) Salon-style Training Format: The training sessions were conducted in the form of salons, held in a meeting room specifically prepared for this purpose. The room was arranged with a round table, warm yellow lighting, green plants, and a coffee bar, creating a conducive environment for free, democratic, and equal communication among the participants. The salon topics included revising project topic selection, conducting current situation investigations, facilitating communication and guidance for literature reviews, formulating improvement plans, implementing those plans, and writing project reports. After the projects were presented, quality management experts provided comments and analysis, promoting the transformation of training outcomes from mere memory and understanding to higher-level abilities such as application, analysis, and creativity.

(3) Continuous Support Services: Various support services were provided to ensure ongoing assistance. This included assigning nursing postgraduates to aid in literature retrieval and evaluation. Project team members also provided on-site guidance and support, actively engaging in the project improvement process to facilitate training transfer.

(4) Emphasis on Spiritual Encouragement: The Vice President of Nursing Department actively participated in the salons and provided feedback on each occasion. Moreover, the President of the hospital consistently commended the training efforts during the weekly hospital meetings.

Issues identified in this cycle

(1) Inconsistent Ability to Write Project Documents: The proficiency in writing project documents for project improvement varied among participants, and there was a lack of standardized evaluation criteria. This issue had the potential to impact the quality of project dissemination.

(2) Lack of Clarity Regarding the Platform and Mechanism for Training Result Transfer: The platform and mechanisms for transferring training results were not clearly defined, posing a challenge in effectively sharing and disseminating the outcomes of the training.

The third cycle (November 2021-march 2022)

During the third cycle, the following initiatives were undertaken.

(1) Utilizing the “Reporting Standards for Quality Improvement Research (SQUIRE)”, as issued by the US Health Care Promotion Research, to provide guidance for students in writing nursing project improvement reports.

(2) Organizing a hospital-level nursing quality improvement project report meeting to acknowledge and commend outstanding projects.

(3) Compiling the “Compilation of Nursing Quality Improvement Projects” for dissemination and exchange among nurses both within and outside the hospital.

(4) Addressing the issue of inadequate management of indicator monitoring data, a hospital-level quality index management platform was developed. The main evaluation data from the 22 projects were entered into this platform, allowing for continuous monitoring and timely intervention.

Effect evaluation

To assess the efficacy of the training, a diverse set of evaluation metrics, encompassing both outcome and process measures [ 26 ]. These measures can be structured around the four-level training evaluation framework proposed by Donald Kirkpatrick [ 27 ].

Process evaluation

Evaluation method.

To assess the commitment and support within the organization, the process evaluation involved recording the proportion of nurses’ classroom participation time and the presence of leaders during each training session. Additionally, a satisfaction survey was conducted after the training to assess various aspects such as venue layout, time arrangement, training methods, lecturer professionalism, content practicality, and interaction. On-site recycling statistics were also collected for project evaluation purposes.

Evaluation results the results of the process evaluation are as follows

Nurse training participation rate: 100%.

Training satisfaction rate (average): 97.75%.

Proportion of nurses’ participation time in theoretical training sessions (average): 36.88%.

Proportion of nurses’ participation time in salon training sessions (average): 74.23%.

Attendance rate of school-level leaders: 100%.

Results evaluation

Assessment of theoretical knowledge of quality management.

To evaluate the effectiveness in enhancing the trainees’ theoretical knowledge of quality management, the research team conducted assessments before the training, after the first round of implementation, and after the third round of implementation. Assessments to evaluate the effectiveness of the training program were conducted immediately following the first round of implementation, and after the third round of implementation. This dual-timing approach was designed to evaluate both the immediate impact of the training and its sustained effects over time, addressing potential influences of memory decay on the study results. The assessment consisted of a 60-minute examination with different question types, including 30 multiple-choice questions (2 points each), 2 short-answer questions (10 points each), and 1 comprehensive analysis question (20 points). The maximum score achievable was 100 points.

The assessment results are as follows:

Before training (average): 75.05 points.

After the first round of implementation (average): 82.18 points.

After the third round of implementation (average): 90.82 points.

Assessment of difficulty in quality management project implementation

To assess the difficulty of implementing quality management projects, the trainees completed the “Quality Management Project Implementation Difficulty Assessment Form” before and after the training. They self-evaluated 10 aspects using a 5-point scale, with 5 indicating the most difficult and 1 indicating no difficulty. The evaluation results before and after implementation are presented in Table 2 .

Statistically significant differences were found in the following items: literature review, current situation analysis, cause analysis, plan formulation, implementation plan, and report writing. This indicates that the training significantly enhanced the nurses’ confidence and ability to tackle practical challenges.

Evaluation of transfer effect

To assess how effectively the training translated into practical applications. The implementation of the 22 quality improvement projects was evaluated using the application hierarchy analysis table. The specific results are presented in Table 3 .

In addition, the “Nursing Project Guidance Manual” and “Compilation of Nursing Project Improvement Projects” were compiled and distributed to the hospital’s management staff, nurses, and four collaborating hospitals, receiving positive feedback. The lecture titled “Improving Nurses’ Project Improvement Ability Based on the Training Transfer Theory Model” shared experiences with colleagues both within and outside the province in national and provincial teaching sessions in 2022. Furthermore, four papers were published on the subject.

The effectiveness of the training program based on the Holton Learning transfer System Inventory

The level of refined management in hospitals is closely tied to the quality management awareness and skills of frontline medical staff. Quality management training plays a crucial role in improving patient safety management and fostering a culture of quality and safety. Continuous quality improvement is an integral part of nursing management, ensuring that patients receive high-quality and safe nursing care. Compared to the focus of existing literature on the individual performance improvements following nursing training programs [ 28 , 29 , 30 ], our study expands the evaluation framework to include organizational performance metrics. Our research underscores a significantly higher level of organizational engagement as evidenced by the 100% attendance rate of school-level leaders. The publication of four papers related to this study highlights not only individual performance achievements but also significantly broadens the hospital organization’s impact on quality management, leading to meaningful organizational outcomes.

Moreover, our initiative to incorporate indicators of quality projects into a hospital-level evaluation index system post-training signifies a pivotal move towards integrating quality improvement practices into the very fabric of organizational operations. In training programs, it is essential not only to achieve near-transfer, but also to ensure that nurses continuously apply the acquired management skills to their clinical work, thereby enhancing quality, developing their professional value, and improving organizational performance. The Holton learning Transfer System Inventory provides valuable guidance on how to implement training programs and evaluate their training effect.

This study adopts the training transfer model as a framework to explore the mechanisms of “how training works” rather than simply assessing “whether training works [ 31 ].” By examining factors such as Motivation to Improve Work Through Learning (MTIWL), learning environment, and transfer design, the current situation is analyzed, underlying reasons are identified, and relevant literature is reviewed to develop and implement training programs based on the results of a needs survey. While individual transfer motivation originates from within the individual, it is influenced by the transfer atmosphere and design. By revising the nurse promotion system and performance management system and aligning them with career development, nurses’ motivation to participate and engage in active learning has significantly increased [ 32 ]. At the learning environment level, enhancing the training effect involves improving factors such as stimulation and response that correspond to the actual work environment [ 33 ]. This project has garnered attention and support from hospital-level leaders, particularly the nursing dean who regularly visits the training site to provide guidance, which serves as invaluable recognition. Timely publicity and recognition of exemplary project improvement initiatives have also increased awareness and understanding of project knowledge among doctors and nurses, fostering a stronger quality improvement atmosphere within the team.

Transfer design, the most critical component for systematic learning and mastery of quality management tools, is achieved through theoretical lectures, salon exchanges, and project-based training. These approaches allow nurses to gain hands-on experience in project improvement under the guidance of instructors. Throughout the project, nurses connect project management knowledge and skills with practical application, enabling personal growth and organizational development through problem-solving in real work scenarios. Finally, a comprehensive evaluation of the training program was conducted, including assessments of theoretical knowledge, perception of management challenges, and project quality. The results showed high satisfaction among nurses, with a satisfaction rate of 97.75%. The proportion of nurses’ participation time in theoretical and practical training classes was 36.88% and 74.23%, respectively. The average score for theoretical knowledge of quality management increased from 75.05 to 90.82. There was also a significant improvement in the evaluation of the implementation difficulties of quality management projects. Moreover, 22 nurses successfully led the completion of one project improvement project, with six projects focusing on preventing the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrating valuable crisis response practices.

Action research helps to ensure the quality of organizational management of training