- Biographies and Features

- Morgenthau Holocaust Project

- Timeline: FDR Day by Day

- Research the Archives

- The Pare Lorentz Center

- Student Resources

- Summer Activities

- Social Media

- Museum Visit

- Research Visit

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Museum Store

- What is a Presidential Library

- The Roosevelt Story

- Events & Registration

- Press and Media

- Program Archives

- Search FRANKLIN

- Plan a Research Visit

- Digital Collections

- Featured Topics

- Morgenthau Project

- Teaching Tools

- Civics for All of US

- Resources for Students

- Distance Learning

- Teacher Workshops

- Field Trips

- NAIN Teachers Conference

- Activities at Home

- 75th Anniversary

- History of the FDR Library

- Library Trustees

- Tell Us Your Roosevelt Story

- Intern and Volunteer

- Donate TODAY!

- Ways To Give

- Get Involved

- Roosevelt Institute

- RI Annual Reports for Roosevelt Library

FDR and the Four Freedoms Speech

Web content display web content display.

Franklin Roosevelt was elected president for an unprecedented third term in 1940 because at the time the world faced unprecedented danger, instability, and uncertainty. Much of Europe had fallen to the advancing German Army and Great Britain was barely holding its own. A great number of Americans remained committed to isolationism and the belief that the United States should continue to stay out of the war, but President Roosevelt understood Britain's need for American support and attempted to convince the American people of the gravity of the situation.

In his Annual Message to Congress (State of the Union Address) on January 6, 1941, Franklin Roosevelt presented his reasons for American involvement, making the case for continued aid to Great Britain and greater production of war industries at home. In helping Britain, President Roosevelt stated, the United States was fighting for the universal freedoms that all people possessed.

As America entered the war these "four freedoms" - the freedom of speech, the freedom of worship, the freedom from want, and the freedom from fear - symbolized America's war aims and gave hope in the following years to a war-wearied people because they knew they were fighting for freedom.

Roosevelt’s preparation of the Four Freedoms Speech was typical of the process that he went through on major policy addresses. To assist him, he charged his close advisers Harry L. Hopkins, Samuel I. Rosenman, and Robert Sherwood with preparing initial drafts. Adolf A. Berle, Jr., and Benjamin V. Cohen of the State Department also provided input. But as with all his speeches, FDR edited, rearranged, and added extensively until the speech was his creation. In the end, the speech went through seven drafts before final delivery.

The famous Four Freedoms paragraphs did not appear in the speech until the fourth draft. One night as Hopkins, Rosenman, and Sherwood met with the President in his White House study, FDR announced that he had an idea for a peroration (the closing section of a speech). As recounted by Rosenman: “We waited as he leaned far back in his swivel chair with his gaze on the ceiling. It was a long pause—so long that it began to become uncomfortable. Then he leaned forward again in his chair” and dictated the Four Freedoms. “He dictated the words so slowly that on the yellow pad I had in my lap I was able to take them down myself in longhand as he spoke.”

The ideas enunciated in the Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms were the foundational principles that evolved into the Atlantic Charter declared by Winston Churchill and FDR in August 1941; the United Nations Declaration of January 1, 1942; President Roosevelt’s vision for an international organization that became the United Nations after his death; and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948 through the work of Eleanor Roosevelt.

Suggested Reading

Elizabeth Borgwardt, A New Deal for the World: America’s Vision for Human Rights (Belknap Press, 2005).

Laura Crowell, “The Building of the ‘Four Freedoms’ Speech,” Speech Monographs 22, (November 1955): 266-283.

Samuel I. Rosenman, Working with Roosevelt (Harper & Brothers, 1952).

Halford R. Ryan, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Rhetorical Presidency (Greenwood Press, 1988).

Mission Statement

The Library's mission is to foster research and education on the life and times of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, and their continuing impact on contemporary life. Our work is carried out by four major areas: Archives, Museum, Education and Public Programs.

- Research the Roosevelts

- News & Events

- Historic Collections

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

The relationship of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt began as the courtship of two young people raised in the same elite New York social circle. Over the next four decades, it became something far more unusual.

View Timeline

Four Freedoms Speech

Listen to the audio excerpt of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms Speech

On January 6, 1941 President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his eighth State of the Union address, now known as the Four Freedoms speech. The speech was intended to rally the American people against the Axis threat and to shift favor in support of assisting British and Allied troops. Roosevelt’s words came at a time of extreme American isolationism; since World War I, many Americans sought to distance themselves from foreign entanglements, including foreign wars. Policies to curb immigration quotas and increase tariffs on imported goods were implemented, and a series of Neutrality Acts passed in the 1930s limited American arms and munitions assistance abroad.

In his address, Roosevelt called for the immediate increase in American arms production, and asked Americans to support his “Lend-Lease” program, which gave Allies cash-free access to US munitions. Most importantly, Roosevelt announced his vision for the world, “a world attainable in our own time and generation,” and founded upon four essential human freedoms: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

These freedoms, Roosevelt declared, must triumph everywhere in the world, and act as a basis of a new moral order. “Freedom,” Roosevelt declared, “means the supremacy of human rights everywhere.”

Legacy of the Four Freedoms

Roosevelt’s call for human rights has created a lasting legacy worldwide. These freedoms became symbols of hope during World War II, adopted by the Allies as the basic tenets needed to create a lasting peace. Following the end of the war, the Four Freedoms formed the basis for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The Declaration was drafted over two years by the Commission on Human Rights, chaired by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. It was adopted on December 10, 1948 and is one of the most widely translated documents in the world. Drawing on Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms speech, the Declaration calls for all governments and people to secure basic human rights and to take measures to ensure these rights are upheld.

The Declaration has inspired numerous international human rights treaties and declarations, and has been incorporated into the constitutions of most countries since 1948.

“I had this thought that a memorial should be a room and a garden. That’s all I had. Why did I want a room and a garden? I just chose it to be the point of departure. The garden is somehow a personal nature, a personal kind of control of nature, a gathering of nature. And the room was the beginning of architecture. I had this sense, you see, and the room wasn’t just architecture, but was an extension of self.”

Jo Davidson

“President Roosevelt won me completely with his charm, his beautiful voice and his freedom from constraint. He had an unshakable faith in man…. In Roosevelt’s tremendous relief program, the artist too was included, and the influence of the WPA projects was tremendous.”

Milestone Documents

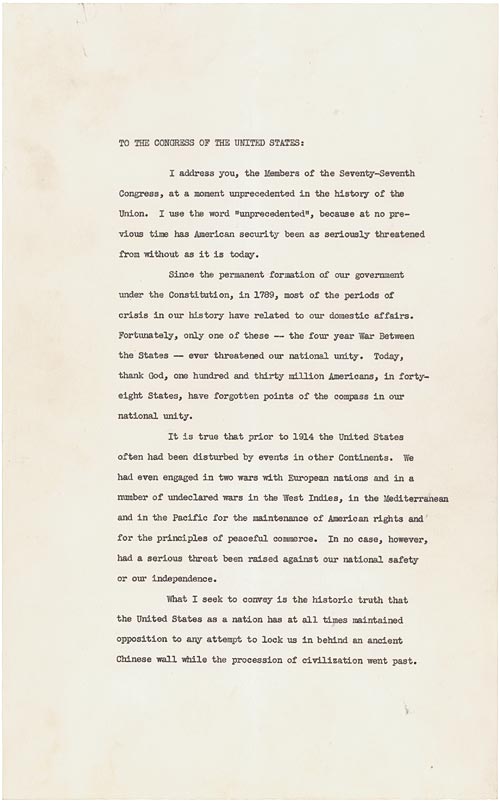

President Franklin Roosevelt's Annual Message (Four Freedoms) to Congress (1941)

Citation: Franklin D. Roosevelt Annual Message to Congress, January 6, 1941; Records of the United States Senate; SEN 77A-H1; Record Group 46; National Archives.

View All Pages in the National Archives Catalog

View Transcript

This speech, delivered by President Franklin Roosevelt on January 6, 1941, became known as his "Four Freedoms Speech" due to a short closing portion in which he described his vision for extending American ideals throughout the world.

Very early in his political career, as state senator and later as Governor of New York, President Roosevelt was concerned with human rights in the broadest sense. During 1940, stimulated by a press conference in which he discussed long-range peace objectives, he started collecting ideas for a speech about various rights and freedoms.

In his 1941 State of the Union Address to Congress, with World War II underway in Europe and the Pacific, FDR asked the American people to work hard to produce armaments for the democracies of Europe, to pay higher taxes, and to make other wartime sacrifices. Roosevelt presented his reasons for American involvement, making the case for continued aid to Great Britain and greater production of war industries at home. In helping Britain, President Roosevelt stated, the United States was fighting for the universal freedoms that all people deserved.

At a time when Western Europe lay under Nazi domination, Roosevelt presented a vision in which the American ideals of individual liberties should be extended throughout the world. Alerting Congress and the nation to the necessity of war, Roosevelt articulated the ideological aims of the war, and appealed to Americans' most profound beliefs about freedom.

In his Four Freedoms Speech, Roosevelt proposed four fundamental freedoms that all people should have. His "four essential human freedoms" included some phrases already familiar to Americans from the Bill of Rights, as well as some new phrases: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. These symbolized America's war aims and gave the American people a mantra to hold onto during the war.

As America became more engaged in World War II, painter Norman Rockwell created a series of paintings illustrating the four freedoms as international war goals that went beyond just defeating the Axis powers. In the series, he translated abstract concepts of freedom into four scenes of everyday American life. Although the federal government initially rejected Rockwell's offer to create paintings on the four freedoms theme, the images were publicly circulated when The Saturday Evening Post , one of the nation's most popular magazines, commissioned and reproduced the paintings. After winning public approval, the paintings served as the centerpiece of a massive U.S. war bond drive and went on a national tour to raise money for the war effort.

After the war, the four freedoms appeared again, embedded in the Charter of the United Nations .

Teach with this document.

Previous Document Next Document

Mr. President, Mr. Speaker, Members of the Seventy-seventh Congress:

I address you, the Members of the Seventy-seventh Congress, at a moment unprecedented in the history of the Union. I use the word "unprecedented," because at no previous time has American security been as seriously threatened from without as it is today.

Since the permanent formation of our Government under the Constitution, in 1789, most of the periods of crisis in our history have related to our domestic affairs. Fortunately, only one of these--the four-year War Between the States--ever threatened our national unity. Today, thank God, one hundred and thirty million Americans, in forty-eight States, have forgotten points of the compass in our national unity.

It is true that prior to 1914 the United States often had been disturbed by events in other Continents. We had even engaged in two wars with European nations and in a number of undeclared wars in the West Indies, in the Mediterranean and in the Pacific for the maintenance of American rights and for the principles of peaceful commerce. But in no case had a serious threat been raised against our national safety or our continued independence.

What I seek to convey is the historic truth that the United States as a nation has at all times maintained clear, definite opposition, to any attempt to lock us in behind an ancient Chinese wall while the procession of civilization went past. Today, thinking of our children and of their children, we oppose enforced isolation for ourselves or for any other part of the Americas.

That determination of ours, extending over all these years, was proved, for example, during the quarter century of wars following the French Revolution.

While the Napoleonic struggles did threaten interests of the United States because of the French foothold in the West Indies and in Louisiana, and while we engaged in the War of 1812 to vindicate our right to peaceful trade, it is nevertheless clear that neither France nor Great Britain, nor any other nation, was aiming at domination of the whole world.

In like fashion from 1815 to 1914-- ninety-nine years-- no single war in Europe or in Asia constituted a real threat against our future or against the future of any other American nation.

Except in the Maximilian interlude in Mexico, no foreign power sought to establish itself in this Hemisphere; and the strength of the British fleet in the Atlantic has been a friendly strength. It is still a friendly strength.

Even when the World War broke out in 1914, it seemed to contain only small threat of danger to our own American future. But, as time went on, the American people began to visualize what the downfall of democratic nations might mean to our own democracy.

We need not overemphasize imperfections in the Peace of Versailles. We need not harp on failure of the democracies to deal with problems of world reconstruction. We should remember that the Peace of 1919 was far less unjust than the kind of "pacification" which began even before Munich, and which is being carried on under the new order of tyranny that seeks to spread over every continent today. The American people have unalterably set their faces against that tyranny.

Every realist knows that the democratic way of life is at this moment being' directly assailed in every part of the world--assailed either by arms, or by secret spreading of poisonous propaganda by those who seek to destroy unity and promote discord in nations that are still at peace.

During sixteen long months this assault has blotted out the whole pattern of democratic life in an appalling number of independent nations, great and small. The assailants are still on the march, threatening other nations, great and small.

Therefore, as your President, performing my constitutional duty to "give to the Congress information of the state of the Union," I find it, unhappily, necessary to report that the future and the safety of our country and of our democracy are overwhelmingly involved in events far beyond our borders.

Armed defense of democratic existence is now being gallantly waged in four continents. If that defense fails, all the population and all the resources of Europe, Asia, Africa and Australasia will be dominated by the conquerors. Let us remember that the total of those populations and their resources in those four continents greatly exceeds the sum total of the population and the resources of the whole of the Western Hemisphere-many times over.

In times like these it is immature--and incidentally, untrue--for anybody to brag that an unprepared America, single-handed, and with one hand tied behind its back, can hold off the whole world.

No realistic American can expect from a dictator's peace international generosity, or return of true independence, or world disarmament, or freedom of expression, or freedom of religion -or even good business.

Such a peace would bring no security for us or for our neighbors. "Those, who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety."

As a nation, we may take pride in the fact that we are softhearted; but we cannot afford to be soft-headed.

We must always be wary of those who with sounding brass and a tinkling cymbal preach the "ism" of appeasement.

We must especially beware of that small group of selfish men who would clip the wings of the American eagle in order to feather their own nests.

I have recently pointed out how quickly the tempo of modern warfare could bring into our very midst the physical attack which we must eventually expect if the dictator nations win this war.

There is much loose talk of our immunity from immediate and direct invasion from across the seas. Obviously, as long as the British Navy retains its power, no such danger exists. Even if there were no British Navy, it is not probable that any enemy would be stupid enough to attack us by landing troops in the United States from across thousands of miles of ocean, until it had acquired strategic bases from which to operate.

But we learn much from the lessons of the past years in Europe-particularly the lesson of Norway, whose essential seaports were captured by treachery and surprise built up over a series of years.

The first phase of the invasion of this Hemisphere would not be the landing of regular troops. The necessary strategic points would be occupied by secret agents and their dupes- and great numbers of them are already here, and in Latin America.

As long as the aggressor nations maintain the offensive, they-not we--will choose the time and the place and the method of their attack.

That is why the future of all the American Republics is today in serious danger.

That is why this Annual Message to the Congress is unique in our history.

That is why every member of the Executive Branch of the Government and every member of the Congress faces great responsibility and great accountability.

The need of the moment is that our actions and our policy should be devoted primarily-almost exclusively--to meeting this foreign peril. For all our domestic problems are now a part of the great emergency.

Just as our national policy in internal affairs has been based upon a decent respect for the rights and the dignity of all our fellow men within our gates, so our national policy in foreign affairs has been based on a decent respect for the rights and dignity of all nations, large and small. And the justice of morality must and will win in the end. Our national policy is this:

First, by an impressive expression of the public will and without regard to partisanship, we are committed to all-inclusive national defense.

Second, by an impressive expression of the public will and without regard to partisanship, we are committed to full support of all those resolute peoples, everywhere, who are resisting aggression and are thereby keeping war away from our Hemisphere. By this support, we express our determination that the democratic cause shall prevail; and we strengthen the defense and the security of our own nation.

Third, by an impressive expression of the public will and without regard to partisanship, we are committed to the proposition that principles of morality and considerations for our own security will never permit us to acquiesce in a peace dictated by aggressors and sponsored by appeasers. We know that enduring peace cannot be bought at the cost of other people's freedom.

In the recent national election there was no substantial difference between the two great parties in respect to that national policy. No issue was fought out on this line before the American electorate. Today it is abundantly evident that American citizens everywhere are demanding and supporting speedy and complete action in recognition of obvious danger.

Therefore, the immediate need is a swift and driving increase in our armament production.

Leaders of industry and labor have responded to our summons. Goals of speed have been set. In some cases these goals are being reached ahead of time; in some cases we are on schedule; in other cases there are slight but not serious delays; and in some cases--and I am sorry to say very important cases--we are all concerned by the slowness of the accomplishment of our plans.

The Army and Navy, however, have made substantial progress during the past year. Actual experience is improving and speeding up our methods of production with every passing day. And today's best is not good enough for tomorrow.

I am not satisfied with the progress thus far made. The men in charge of the program represent the best in training, in ability, and in patriotism. They are not satisfied with the progress thus far made. None of us will be satisfied until the job is done.

No matter whether the original goal was set too high or too low, our objective is quicker and better results. To give you two illustrations:

We are behind schedule in turning out finished airplanes; we are working day and night to solve the innumerable problems and to catch up.

We are ahead of schedule in building warships but we are working to get even further ahead of that schedule.

To change a whole nation from a basis of peacetime production of implements of peace to a basis of wartime production of implements of war is no small task. And the greatest difficulty comes at the beginning of the program, when new tools, new plant facilities, new assembly lines, and new ship ways must first be constructed before the actual materiel begins to flow steadily and speedily from them.

The Congress, of course, must rightly keep itself informed at all times of the progress of the program. However, there is certain information, as the Congress itself will readily recognize, which, in the interests of our own security and those of the nations that we are supporting, must of needs be kept in confidence.

New circumstances are constantly begetting new needs for our safety. I shall ask this Congress for greatly increased new appropriations and authorizations to carry on what we have begun.

I also ask this Congress for authority and for funds sufficient to manufacture additional munitions and war supplies of many kinds, to be turned over to those nations which are now in actual war with aggressor nations.

Our most useful and immediate role is to act as an arsenal for them as well as for ourselves. They do not need man power, but they do need billions of dollars worth of the weapons of defense.

The time is near when they will not be able to pay for them all in ready cash. We cannot, and we will not, tell them that they must surrender, merely because of present inability to pay for the weapons which we know they must have.

I do not recommend that we make them a loan of dollars with which to pay for these weapons--a loan to be repaid in dollars.

I recommend that we make it possible for those nations to continue to obtain war materials in the United States, fitting their orders into our own program. Nearly all their materiel would, if the time ever came, be useful for our own defense.

Taking counsel of expert military and naval authorities, considering what is best for our own security, we are free to decide how much should be kept here and how much should be sent abroad to our friends who by their determined and heroic resistance are giving us time in which to make ready our own defense.

For what we send abroad, we shall be repaid within a reasonable time following the close of hostilities, in similar materials, or, at our option, in other goods of many kinds, which they can produce and which we need.

Let us say to the democracies: "We Americans are vitally concerned in your defense of freedom. We are putting forth our energies, our resources and our organizing powers to give you the strength to regain and maintain a free world. We shall send you, in ever-increasing numbers, ships, planes, tanks, guns. This is our purpose and our pledge."

In fulfillment of this purpose we will not be intimidated by the threats of dictators that they will regard as a breach of international law or as an act of war our aid to the democracies which dare to resist their aggression. Such aid is not an act of war, even if a dictator should unilaterally proclaim it so to be.

When the dictators, if the dictators, are ready to make war upon us, they will not wait for an act of war on our part. They did not wait for Norway or Belgium or the Netherlands to commit an act of war.

Their only interest is in a new one-way international law, which lacks mutuality in its observance, and, therefore, becomes an instrument of oppression.

The happiness of future generations of Americans may well depend upon how effective and how immediate we can make our aid felt. No one can tell the exact character of the emergency situations that we may be called upon to meet. The Nation's hands must not be tied when the Nation's life is in danger.

We must all prepare to make the sacrifices that the emergency-almost as serious as war itself--demands. Whatever stands in the way of speed and efficiency in defense preparations must give way to the national need.

A free nation has the right to expect full cooperation from all groups. A free nation has the right to look to the leaders of business, of labor, and of agriculture to take the lead in stimulating effort, not among other groups but within their own groups.

The best way of dealing with the few slackers or trouble makers in our midst is, first, to shame them by patriotic example, and, if that fails, to use the sovereignty of Government to save Government.

As men do not live by bread alone, they do not fight by armaments alone. Those who man our defenses, and those behind them who build our defenses, must have the stamina and the courage which come from unshakable belief in the manner of life which they are defending. The mighty action that we are calling for cannot be based on a disregard of all things worth fighting for.

The Nation takes great satisfaction and much strength from the things which have been done to make its people conscious of their individual stake in the preservation of democratic life in America. Those things have toughened the fibre of our people, have renewed their faith and strengthened their devotion to the institutions we make ready to protect.

Certainly this is no time for any of us to stop thinking about the social and economic problems which are the root cause of the social revolution which is today a supreme factor in the world.

For there is nothing mysterious about the foundations of a healthy and strong democracy. The basic things expected by our people of their political and economic systems are simple. They are:

Equality of opportunity for youth and for others. Jobs for those who can work. Security for those who need it. The ending of special privilege for the few. The preservation of civil liberties for all.

The enjoyment of the fruits of scientific progress in a wider and constantly rising standard of living.

These are the simple, basic things that must never be lost sight of in the turmoil and unbelievable complexity of our modern world. The inner and abiding strength of our economic and political systems is dependent upon the degree to which they fulfill these expectations.

Many subjects connected with our social economy call for immediate improvement. As examples:

We should bring more citizens under the coverage of old-age pensions and unemployment insurance.

We should widen the opportunities for adequate medical care.

We should plan a better system by which persons deserving or needing gainful employment may obtain it.

I have called for personal sacrifice. I am assured of the willingness of almost all Americans to respond to that call.

A part of the sacrifice means the payment of more money in taxes. In my Budget Message I shall recommend that a greater portion of this great defense program be paid for from taxation than we are paying today. No person should try, or be allowed, to get rich out of this program; and the principle of tax payments in accordance with ability to pay should be constantly before our eyes to guide our legislation.

If the Congress maintains these principles, the voters, putting patriotism ahead of pocketbooks, will give you their applause.

In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech and expression--everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way--everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want--which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants-everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear--which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor--anywhere in the world.

That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation. That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb.

To that new order we oppose the greater conception--the moral order. A good society is able to face schemes of world domination and foreign revolutions alike without fear.

Since the beginning of our American history, we have been engaged in change -- in a perpetual peaceful revolution -- a revolution which goes on steadily, quietly adjusting itself to changing conditions--without the concentration camp or the quick-lime in the ditch. The world order which we seek is the cooperation of free countries, working together in a friendly, civilized society.

This nation has placed its destiny in the hands and heads and hearts of its millions of free men and women; and its faith in freedom under the guidance of God. Freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere. Our support goes to those who struggle to gain those rights or keep them. Our strength is our unity of purpose. To that high concept there can be no end save victory.

Skip to Main Content of WWII

The four freedoms.

In January of 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt outlined a vision of the future in which people the world over could enjoy four essential freedoms. This vision persisted throughout World War II and came to symbolize the ideals behind the rights of humanity and the pursuit of peace in a postwar world.

Eleven months before the Japanese Empire launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt (FDR) gave a speech that came to symbolize the broader meaning behind America’s effort to defeat fascism abroad. Delivered during the State of the Union on January 6, 1941, Roosevelt took a stance against the calls for isolationism prevalent at that time and issued a call to action to defend global democracy, stating that the United States had a responsibility to fight for four universal freedoms people the world over ought to enjoy. After the United States formally entered the war in December 1941, these “Four Freedoms” became a driving message behind the need to stop the Axis powers. As captured by this speech, World War II was not simply a war to defeat dictators, but it was a war to preserve the fundamental freedoms that defined life in a free, democratic society.

The Freedoms

Although delivered well before the United States joined the other Allied Powers to fight in World War II, Roosevelt’s speech remained closely intertwined with the history and legacy of the war. By describing the grave threat facing democratic societies around the world, he gave voice to the fears that permeated daily life in the months before America’s eventual entrance into the war. He did so to emphasize the urgent need to prepare for war, as well as to continue supporting American allies with arms and munitions. Looking ahead to the war’s end, Roosevelt described a world that he saw as “founded upon four essential human freedoms.” The first of the four freedoms was the freedom of speech . The second he listed was the freedom to worship in one’s own way . The third was the freedom from want . Roosevelt explained this freedom as encompassing the economic stability to ensure “to every nation a healthy peacetime” once the turmoil of war came to an end. The fourth freedom was the freedom from fear , which President Roosevelt believed would come with a reduction of armaments worldwide.

Roosevelt saw these freedoms as obtainable in the lifetime of those who, 11 months later, began the march to war. These freedoms—of speech and worship, and from want and fear—gave those who went to war a clear purpose. This speech not only outlined what Americans fought against in World War II, but more importantly, the speech described what was being fought for. Although this speech, delivered in the era of American isolationism, initially received criticism, the ideals Roosevelt put forth cultivated an enduring legacy for the efforts all Americans contributed to the war, both abroad and at home.

In 1942, the artist Norman Rockwell, who had been looking for ways to support the war effort, saw Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms speech as a source of inspiration. Basing each freedom on simple scenes of individuals in town hall meetings, in the midst of prayer, or at home with their families, Rockwell constructed widely successful visual representations of each freedom. The images, originally published in The Saturday Evening Post , proved so popular the US Department of the Treasury sold copies of the paintings to raise money for war bonds. After launching the campaign, roughly 2,000 requests for the posters came in daily. To this day, Rockwell’s illustrations continue to represent glimpses into an idealized American society, inspired by FDR’s aspirations for the postwar world.

Part of artist Norman Rockwell’s series of paintings on the Four Freedoms, depicting followers of different religions engaged in prayer. Image courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, 513537.

The WWII Victory Medal captured the importance of FDR’s vision by featuring each of the Four Freedoms on the back side of the medal. Created through an act of Congress, the United States military awarded this medal to all who served between the dates of December 7, 1941, and December 31, 1946, the date President Harry Truman declared an official end of hostilities. The WWII Victory Medal, commonly referred to as the “Victory Ribbon,” depicted a figure of Liberation, holding a broken blade in one hand and the hilt of a broken sword in the other. Liberation’s foot rested upon the top of a helmet to indicate victory in war. On the reverse, the Four Freedoms appeared in bold lettering, a reminder of what those who served fought to protect.

While FDR did not live to see the war come to an end, the vision he presented in January 1941 proved an enduring source of guidance in the years that followed Germany’s and Japan’s formal surrender. His widow, Eleanor Roosevelt, incorporated the language of the Four Freedoms within the Preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states,

“Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people.”

Preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Adopted by the United Nations on December 10, 1948, during an era of increasing decolonization that followed World War II, this Declaration recognized need to protect these fundamental human rights the world over. Following this victory, Eleanor continued to advocate for her late husband’s vision throughout the rest of her life. In a broadcast given in 1951, Eleanor made it clear: “It isn’t enough to talk about peace. One must believe in it. And it isn’t enough to believe in it. One must work at it.” Decades later, the Four Freedoms remains a guiding message in the protection and preservation of human rights. Included in the language of the International Bill of Human Rights, ratified in 1976, and preserved in the iconic Norman Rockwell paintings, FDR’s speech serves as a reminder of the freedoms people can enjoy, should they remain willing to defend them.

Like this article? Read more in our online classroom.

From the Collection to the Classroom: Teaching History with The National WWII Museum.

Kristen D. Burton, PhD

Kristen D. Burton is the Teacher Programs and Curriculum Specialist at The National WWII Museum in New Orleans, LA.

Explore Further

The Holocaust

The Holocaust was Nazi Germany’s deliberate, organized, state-sponsored persecution and genocide of European Jews. During the war, the Nazi regime and their collaborators systematically murdered over six million Jewish people.

The Fallen Crew of the USS Arizona and Operation 85

The Operation 85 project aims to identify unknown servicemen who perished aboard the USS Arizona during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

'Maxwell Opened My Eyes': Rosa Parks, WWII Defense Worker

Before her historic protest in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Rosa Parks was a Home Front worker at Maxwell Airfield.

Patchwork Plane: Building the P-47 Thunderbolt

Roughly 100 companies, coast to coast, helped Republic Aviation Corporation manufacture each P-47 Thunderbolt.

The Chopping Block: The Fate of Warplanes after WWII

After the war, hundreds of thousands of US warplanes remained—but the military needed only a fraction of them.

War Time: How America's Wristwatch Industry Became a War Casualty

Prior to World War II, there was a thriving American wristwatch industry, but it became a casualty of the war.

Standing against "Universal Death": The Russell–Einstein Manifesto

Penned by philosopher Bertrand Russell and endorsed by Albert Einstein, the document warned human beings about the existential threat posed by the new hydrogen bomb.

1936, a Year for the Worker: Factory Occupations and the Popular Front’s Victory in France

The election of the Popular Front government in France and a wave of factory occupations secured huge gains for French workers.

Annual Message to Congress (1941): The Four Freedoms

- January 06, 1941

Introduction

In his annual State of the Union Address to Congress on January 6, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt reiterated the importance of supporting Great Britain in its war with Nazi Germany. In making his case, Roosevelt underscored the two nations’ shared commitment to four universal freedoms. The “Four Freedoms” were subsequently formally incorporated into the Atlantic Charter crafted by Winston Churchill and FDR in August 1941. Once the United States entered the war on December 8, 1941, protecting these freedoms became the cornerstone of the American war effort.

Source: President Franklin Roosevelt’s Annual Message (Four Freedoms) to Congress (1941), in 100 Milestone Documents , an online library compiled by the “Our Documents” Initiative, a cooperative effort of the National Archives and Records Administration with National History Day and USA Freedom Corps. https://goo.gl/9PmD2o .

Mr. President, Mr. Speaker, Members of the Seventy-seventh Congress:

I address you, the Members of the Seventy-seventh Congress, at a moment unprecedented in the history of the Union. I use the word “unprecedented,” because at no previous time has American security been as seriously threatened from without as it is today. . . .

Even when the World War broke out in 1914, it seemed to contain only small threat of danger to our own American future. But, as time went on, the American people began to visualize what the downfall of democratic nations might mean to our own democracy.

We need not overemphasize imperfections in the Peace of Versailles. We need not harp on failure of the democracies to deal with problems of world reconstruction. We should remember that the Peace of 1919 1 was far less unjust than the kind of “pacification” which began even before Munich, 2 and which is being carried on under the new order of tyranny that seeks to spread over every continent today. The American people have unalterably set their faces against that tyranny.

Every realist knows that the democratic way of life is at this moment being directly assailed in every part of the world – assailed either by arms, or by secret spreading of poisonous propaganda by those who seek to destroy unity and promote discord in nations that are still at peace.

During sixteen long months this assault has blotted out the whole pattern of democratic life in an appalling number of independent nations, great and small. The assailants are still on the march, threatening other nations, great and small.

Therefore, as your President, performing my constitutional duty to “give to the Congress information of the state of the Union,” I find it, unhappily, necessary to report that the future and the safety of our country and of our democracy are overwhelmingly involved in events far beyond our borders.

Armed defense of democratic existence is now being gallantly waged in four continents. If that defense fails, all the population and all the resources of Europe, Asia, Africa and Australasia will be dominated by the conquerors. Let us remember that the total of those populations and their resources in those four continents greatly exceeds the sum total of the population and the resources of the whole of the Western Hemisphere – many times over.

In times like these it is immature – and incidentally, untrue – for anybody to brag that an unprepared America, single-handed, and with one hand tied behind its back, can hold off the whole world.

No realistic American can expect from a dictator’s peace international generosity, or return of true independence, or world disarmament, or freedom of expression, or freedom of religion – or even good business. . . .

The need of the moment is that our actions and our policy should be devoted primarily – almost exclusively – to meeting this foreign peril. For all our domestic problems are now a part of the great emergency.

Just as our national policy in internal affairs has been based upon a decent respect for the rights and the dignity of all our fellow men within our gates, so our national policy in foreign affairs has been based on a decent respect for the rights and dignity of all nations, large and small. And the justice of morality must and will win in the end. Our national policy is this:

First, by an impressive expression of the public will and without regard to partisanship, we are committed to all-inclusive national defense.

Second, by an impressive expression of the public will and without regard to partisanship, we are committed to full support of all those resolute peoples, everywhere, who are resisting aggression and are thereby keeping war away from our Hemisphere. By this support, we express our determination that the democratic cause shall prevail; and we strengthen the defense and the security of our own nation.

Third, by an impressive expression of the public will and without regard to partisanship, we are committed to the proposition that principles of morality and considerations for our own security will never permit us to acquiesce in a peace dictated by aggressors and sponsored by appeasers.

We know that enduring peace cannot be bought at the cost of other people’s freedom.

In the recent national election there was no substantial difference between the two great parties in respect to that national policy. No issue was fought out on this line before the American electorate. Today it is abundantly evident that American citizens everywhere are demanding and supporting speedy and complete action in recognition of obvious danger.

Therefore, the immediate need is a swift and driving increase in our armament production. . . .

A free nation has the right to expect full cooperation from all groups. A free nation has the right to look to the leaders of business, of labor, and of agriculture to take the lead in stimulating effort, not among other groups but within their own groups.

The best way of dealing with the few slackers or trouble makers in our midst is, first, to shame them by patriotic example, and, if that fails, to use the sovereignty of Government to save Government.

As men do not live by bread alone, they do not fight by armaments alone. Those who man our defenses, and those behind them who build our defenses, must have the stamina and the courage which come from unshakable belief in the manner of life which they are defending. The mighty action that we are calling for cannot be based on a disregard of all things worth fighting for.

The Nation takes great satisfaction and much strength from the things which have been done to make its people conscious of their individual stake in the preservation of democratic life in America. Those things have toughened the fiber of our people, have renewed their faith and strengthened their devotion to the institutions we make ready to protect.

Certainly this is no time for any of us to stop thinking about the social and economic problems which are the root cause of the social revolution which is today a supreme factor in the world.

For there is nothing mysterious about the foundations of a healthy and strong democracy. The basic things expected by our people of their political and economic systems are simple. They are:

Equality of opportunity for youth and for others.

Jobs for those who can work.

Security for those who need it.

The ending of special privilege for the few.

The preservation of civil liberties for all.

The enjoyment of the fruits of scientific progress in a wider and constantly rising standard of living.

These are the simple, basic things that must never be lost sight of in the turmoil and unbelievable complexity of our modern world. The inner and abiding strength of our economic and political systems is dependent upon the degree to which they fulfill these expectations.

Many subjects connected with our social economy call for immediate improvement. As examples:

We should bring more citizens under the coverage of old-age pensions and unemployment insurance.

We should widen the opportunities for adequate medical care.

We should plan a better system by which persons deserving or needing gainful employment may obtain it.

I have called for personal sacrifice. I am assured of the willingness of almost all Americans to respond to that call.

A part of the sacrifice means the payment of more money in taxes. In my Budget Message I shall recommend that a greater portion of this great defense program be paid for from taxation than we are paying today. No person should try, or be allowed, to get rich out of this program; and the principle of tax payments in accordance with ability to pay should be constantly before our eyes to guide our legislation.

If the Congress maintains these principles, the voters, putting patriotism ahead of pocketbooks, will give you their applause.

In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech and expression – everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way – everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want – which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants – everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear – which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor – anywhere in the world.

That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation. That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb.

To that new order we oppose the greater conception – the moral order. A good society is able to face schemes of world domination and foreign revolutions alike without fear.

Since the beginning of our American history, we have been engaged in change – in a perpetual peaceful revolution – a revolution which goes on steadily, quietly adjusting itself to changing conditions – without the concentration camp 3 or the quick-lime in the ditch. The world order which we seek is the cooperation of free countries, working together in a friendly, civilized society.

This nation has placed its destiny in the hands and heads and hearts of its millions of free men and women; and its faith in freedom under the guidance of God. Freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere. Our support goes to those who struggle to gain those rights or keep them. Our strength is our unity of purpose. To that high concept there can be no end save victory.

- 1. By “Peace of 1919” and “Peace of Versailles” Roosevelt means the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, which ended the war between Germany and the Allied Powers: principally Britain, France, and the United States. The terms of the treaty, particularly large reparation payments from Germany to the allies, were widely held to have caused many of the problems of the inter-war years and contributed to the rise of Nazism in Germany.

- 2. The Munich Agreement, September 28, 1938, between Germany, Italy, France, and Great Britain allowed Germany to annex parts of Czechoslovakia. Germany occupied other parts of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, gaining significant industrial capacity and armaments. In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland.

- 3. The term “concentration camp” was first used to refer to any detention of people in a confined area by a political or military power. The Nazis began using concentration camps inside Germany to detain political opponents soon after coming to power.

Radio Address by Senator Burton Wheeler (D-MT)

A warning on isolationism, see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Check out our collection of primary source readers

Our Core Document Collection allows students to read history in the words of those who made it. Available in hard copy and for download.

The blog of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

Forward with Roosevelt

The “Four Freedoms” speech remastered

By Paul M. Sparrow, Director, FDR Library.

There is only one speech in American history that inspired a multitude of books and films, the establishment of its own park, a series of paintings by a world famous artist, a prestigious international award and a United Nation’s resolution on Human Rights.

That speech is Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union Address, commonly known as the “Four Freedoms” speech. In it he articulated a powerful vision for a world in which all people had freedom of speech and of religion, and freedom from want and fear. It was delivered on January 6, 1941 and it helped change the world. The words of the speech are enshrined in marble at Four Freedoms Park on Roosevelt Island in New York, are visualized in the paintings of Norman Rockwell, inspired the international Four Freedoms Award and are the foundation for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948.

On the 50 th anniversary of the speech in 1991 a ceremony was held in the U.S. Capitol featuring a remarkable bi-partisan group of leaders including Sen. Bob Dole, Rep. Richard Gephardt, Anne Roosevelt and President George H.W. Bush. President Bush said this about FDR’s Four Freedoms:

“Two hundred years ago, perhaps our greatest political philosopher, Thomas Jefferson, defined our nation’s identity when he wrote “All men are created equal, endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, among them are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Fifty years ago, our greatest American political pragmatist, Roosevelt, refined that thought in his Four Freedoms when he brilliantly enunciated our 20 th century vision of our founding fathers’ commitment to individual liberty.”

Video – 50th Anniversary of FDR’s Four Freedoms Speech

To honor the 75 th anniversary of this historic presidential address, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum joined forces with the National Archives Motion Picture Preservation Labs to create new enhanced versions of the speech in HD and Ultra-HD (4K) file formats. These new versions were transferred directly from the original 35mm film stock. Audio from the original disk recordings were then synced with the new video files to create an entirely new resource. The new HD video is now available to the public here , and the 4K video is available upon special request from the Library.

(Copyright Sherman Grinberg Film Library – http://www.shermangrinberg.com/)

It is important to fully understand the historic context of this speech. On November 5 th , 1940 Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president for an unprecedented third term. It was a dark time as the world faced unprecedented danger, instability, and war. Much of Europe had fallen to the Nazis and Great Britain was barely holding its own. The Japanese Empire brutally occupied much of China and East Asia. A great number of Americans remained committed to isolationism and the belief that the United States should stay out of the war. President Roosevelt understood Britain’s desperate need for American support and attempted to convince the American people to come to the aid of their closest ally.

In his address on January 6, 1941, Franklin Roosevelt presented his reasons for American involvement, making the case for continued aid to Great Britain and greater production of war industries at home. In helping Britain, President Roosevelt stated, the United States was fighting for the universal freedoms that all people deserved.

As America entered the war these “four freedoms” – the freedom of speech, the freedom of worship, the freedom from want, and the freedom from fear – symbolized America’s war aims and gave hope in the following years to a war-wearied people because they knew they were fighting for freedom.

The ideas enunciated in Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms were the foundational principles that evolved into the Atlantic Charter declared by Winston Churchill and FDR in August 1941; the United Nations Declaration of January 1, 1942; President Roosevelt’s vision for an international organization that became the United Nations after his death; and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948 through the work of Eleanor Roosevelt.

As tyrannical leaders once again resort to brutal oppression and terrorism to achieve their goals, as democracy and journalism are under attack from extremists across the globe, and as surveillance and technology threaten individual liberties and freedom of expression, FDRs bold vision for a world that embraces these four fundamental freedoms is as vital today as it was 75 years ago.

Special thanks to the New York Community Trust for their ongoing support of the Pare Lorentz Film Center.

Share this:

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : January 6

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Franklin D. Roosevelt speaks of Four Freedoms

On January 6, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addresses Congress in an effort to move the nation away from a foreign policy of neutrality. The president had watched with increasing anxiety as European nations struggled and fell to Hitler’s fascist regime and was intent on rallying public support for the United States to take a stronger interventionist role. In his address to the 77th Congress, Roosevelt stated that the need of the moment is that our actions and our policy should be devoted primarily–almost exclusively–to meeting the foreign peril. For all our domestic problems are now a part of the great emergency.

Roosevelt insisted that people in all nations of the world shared Americans’ entitlement to four freedoms: the freedom of speech and expression, the freedom to worship God in his own way, freedom from want and freedom from fear. After Roosevelt’s death and the end of World War II , his widow Eleanor often referred to the four freedoms when advocating for passage of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Mrs. Roosevelt participated in the drafting of that declaration, which was adopted by the United Nations in 1948.

Also on This Day in History January | 6

U.s. capitol riot, "wheel of fortune" premieres, joan of arc is born.

This Day in History Video: What Happened on January 6

Theodore roosevelt dies, new mexico joins the union.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Harold II crowned king of England

Congress certifies george w. bush winner of 2000 elections, samuel morse unveils the telegraph, revolutionizing communication, army drops charges of my lai cover-up, two future presidents marry respective sweethearts, frontiersman jedediah smith is born, two thousand led zeppelin fans trash the boston garden, blizzard of 1996 begins, skater nancy kerrigan attacked.

Four Freedoms Speech

30 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Index of Terms

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “four freedoms speech”.

On January 6, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed the members of the 77th Congress with his “Four Freedoms Speech.” At this time, the United Kingdom and its Allies were heavily embroiled in World War II, while the United States remained neutral. However, Roosevelt understood that the fate of his nation was inextricably tied to the fight against totalitarianism in Europe. The president’s speech served as a call to arms, both literal and figurative, urging the American people and the rest of the democratic world to unite behind the common cause of freedom . In the face of unprecedented threats to American security, Roosevelt articulated a vision for a future where essential freedoms were safeguarded, injustice was confronted, and cooperation prevailed.

This guide refers to the online transcript of the speech freely available at Voices of Democracy: The U.S. Oratory Project . Citations refer to paragraph numbers.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,750+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,800+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Roosevelt’s speech begins by acknowledging the gravity of the situation the country finds itself in, asserting that American security has never been so seriously jeopardized by external forces. He critiques an isolationist stance to world affairs, comparing it to placing the US behind “an ancient Chinese wall” while the world advanced (5). Instead, he emphasizes the importance of committing to international engagement.

The president recalls a time when threats to American safety were rare. Before 1914, the US had engaged in wars and conflicts, yet its national safety and continued independence remained intact. He acknowledges the toll World War I took on the US and admits that the 1919 Treaty of Versailles failed to secure a long-lasting peace. However, he suggests World War II represents an “unprecedented” threat to American democracy . Roosevelt warns of the untrustworthy nature of “peace dictated by aggressors and appeasers” (10). He also challenges “loose talk of [the US’s] immunity” from invasion (23), asserting that secret agents of the Axis powers are sure to have infiltrated the American population.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 175 + new titles every month

The president introduces his vision of the “Four Freedoms.” He identifies freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear as fundamental human rights that should be upheld globally. The president envisions a world where economic understandings would secure peace for every nation and armament reduction would prevent physical aggression.

By articulating the Four Freedoms , Roosevelt envisions a just and equitable world order. Freedom of speech and expression is the bedrock of democratic societies, ensuring the unrestricted flow of ideas and opinions. Freedom of worship acknowledges the diversity of religious beliefs and underscores the importance of respecting and protecting individual faith. Freedom from want seeks to address the socioeconomic disparities that plague societies, advocating for economic systems that provide a decent standard of living for all. Lastly, freedom from fear aspires to a world where nations would no longer live in constant apprehension of armed conflict but instead embrace diplomacy and disarmament.

Underlining the situation’s urgency, Roosevelt calls for all-inclusive national defense and expresses unwavering support for nations resisting the aggression of totalitarian powers. He proposes that America act as “an arsenal ,” manufacturing and providing war materials to the Allied nations engaged in active conflict. The repayment for this support could be in kind, through similar materials or other goods, further benefiting America’s defense. He urges Congress to prioritize the nation’s security, highlighting the need for increased armament production. To achieve this goal, the president emphasizes the need for increased taxation. Roosevelt also champions human rights and social justice , advocating for improved social and economic conditions, such as “old-age pensions,” “unemployment insurance,” and “adequate medical care” (76-77).

Roosevelt compares the “new order of tyranny” sought by totalitarian dictators with the morally principled values championed by the US (11). He encourages citizens to face adversity without fear, asserting that America’s destiny resides in the hands, heads, and hearts of its millions of free men and women. Roosevelt asserts that, guided by faith in democracy, the nation has the strength to confront schemes of world domination.

In his closing remarks, Roosevelt underscores the shared responsibility of Congress and the American people to work toward a world founded on the principles of the Four Freedoms. He emphasizes that the futures of America and the world depend on swift and resolute action, urging continued unity in the face of adversity.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Executive Order 9066

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Featured Collections

Books on Justice & Injustice

View Collection

Books on U.S. History

Nation & Nationalism

Politics & Government

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

FDR’s “Four Freedoms” Speech

Engraving of the Four Freedoms at the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Wikimedia Commons

"Sometimes we fail to hear or heed these voices of freedom because to us the privilege of our freedom is such an old, old story." —Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in his Third Inaugural Address, January 20, 1941.

While many of the most frequently-studied statements about freedom were published in the form of written documents such as the Bill of Rights or the Magna Carta , the library is certainly not the only place where Americans encounter references to freedom. On radio and television, on the campaign trail and at press conferences, our public officials appeal to the cause of freedom every day. The world of political oratory provides a living laboratory for studying the place of "freedom" within public discourse. Some of the most thought-provoking—and influential—musings on freedom were first presented not in books or in pamphlets, but broadcast from podiums and grandstands.

Guiding Questions

What does freedom mean?

What does FDR's "Four Freedoms" speech reveal about the variety of different attitudes, priorities, and political philosophies encompassed by the word "freedom"?

Learning Objectives

Examine the substance, context, subtext, and significance of the most famous portion of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's 1941 State of the Union Address.

Evaluate the influence of political rhetoric and oratory on the ongoing process of refining our definitions of "freedom."

Evaluate longstanding theoretical debates over the scope and meaning of freedom.

Create an original argument regarding the theory and practice of freedom in the U.S.

Lesson Plan Details

One of the most famous political speeches on freedom in the twentieth century was delivered by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his 1941 State of the Union message to Congress. The address is commonly known as the "Four Freedoms" speech, and an excerpt is available through the EDSITEment-reviewed website POTUS—Presidents of the United States .

In the relevant part of the speech , President Roosevelt announced:

"In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression -- everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way -- everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want -- which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants -- everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear -- which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor-- anywhere in the world."

In bold and plain language, Roosevelt's declaration raises many of the broad questions underlying any discussion of freedom. This lesson will introduce students to some of the rudiments of political theory embedded within FDR's vision.

The tone set by FDR in his "Four Freedoms" speech has been imitated by his successors and by his counterparts in other countries. Students today are so accustomed to hearing freedom invoked rhetorically as a matter of course that the word sometimes signifies little more than something to feel vaguely good about. This lesson will examine some of the nuances, vagaries, and ambiguities inherent in the rhetorical use of "freedom." The objective is to encourage students to glimpse the broad range of hopes and aspirations that are expressed in the call of—and for—freedom.

The ostensible purpose of FDR's 1941 State of the Union was not to comment about freedom in the abstract, but to persuade a reluctant Congress to pass the Lend-Lease Act. Through speeches like the Four Freedoms speech, FDR successfully sold the public and the Congress on the idea of the Lend-Lease Act. The passage of the Act effectively ended American neutrality in World War II by essentially giving the British the badly needed weapons that they could not afford to buy. This lesson does not focus on the debate over American participation in World War II, but it is impossible to read Roosevelt's "Four Freedoms" as anything other than an argument against American neutrality in the war. Initially, of course, FDR was—at least publicly—in favor of neutrality. This is the position he stakes out in a fireside chat entitled " On the European War ." In this speech, delivered in September 1939, FDR says the following:

"Let no man or woman thoughtlessly or falsely talk of America sending its armies to European fields. At this moment there is being prepared a proclamation of American neutrality. This would have been done even if there had been no neutrality statute on the books, for this proclamation is in accordance with international law and in accordance with American policy."

It will be helpful, in considering the evolution of FDR's foreign policy, to consult a timeline of World War II related events that occurred during his presidency. An excellent WWII timeline is available through the FDR page of the PBS American Experience: The Presidents website. The American Experience site is available as a link from the EDSITEment resource New Deal Network.

Review and print the transcripts of some of FDR's fireside chats . Reading very short excerpts from these transcripts in Activity 2 will help set the scene for the unique rapport FDR had established with the American people by the time he made his Four Freedoms speech. You may want to pay particularly close attention to the September 1934 chat entitled " Greater Freedom and Greater Security ," which will be used in Activity 2.

- For general background on the life and policies of President Roosevelt, you may consult the general internet biography available through the American Presidency .

NCSS.D2.His.1.9-12. Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

NCSS.D2.His.2.9-12. Analyze change and continuity in historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

NCSS.D2.His.12.9-12. Use questions generated about multiple historical sources to pursue further inquiry and investigate additional sources.

NCSS.D2.His.14.9-12. Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.

NCSS.D2.His.15.9-12. Distinguish between long-term causes and triggering events in developing a historical argument.

NCSS.D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

Activity 1. Competing definitions of freedom: Is the idea of freedom universal?

People do not always agree about which freedoms are most essential. More generally, we can add that people do not even agree about what counts as freedom at all . But notice that President Roosevelt's vision of freedom is a universal one. He emphasizes his hope that each of the freedoms he lists will take hold " everywhere in the world ." Discuss:

- Is it possible to distinguish between ideas of freedom that are specific to certain times and places and ideas of freedom that are universal?

- How should we address disagreement about the meaning of freedom?

- What does the Declaration of Independence tell us about the universality of human freedom?

- How does the American Constitutional system handle disagreement about the meaning of freedom? Does the system of federalism and states' rights reflect the Founders' willingness to entertain more than one conception of freedom? What about the Bill of Rights?

- In the long run, can more than one idea of freedom coexist within a single nation? Within the world?

Activity 2. If you had to choose: Which freedoms are most essential?

As students will surely notice during activity 1, a roomful of people will come up with a roomful of responses when asked to identify the four most essential freedoms. Now ask students to think about the significance of the particular four freedoms listed by FDR: expression, worship, economic prosperity, and physical security.

- Why do you suppose that these were the four freedoms he chose to highlight as "essential?"

- How did the historical circumstances of the speech (see timeline ) contribute to FDR's emphasis on these freedoms?

- How are these four freedoms foreshadowed in FDR's 1934 fireside chat on economic freedom and security for all Americans? How is the 1934 speech different?

- Obviously there are more than four freedoms that the President could have mentioned. Which potential freedoms did the President leave out?

- How do FDR's four freedoms compare with the essential freedoms that the class came up with in Activity 1?

- How do FDR's four freedoms compare with the liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights?

Explain to the class that FDR's goal in giving the "Four Freedoms" speech was to persuade Congress to end American neutrality in World War II through the passage of the Lend-Lease Act. If desired, you can read FDR's 1939 fireside chat in support of American neutrality in World War II(see the excerpt in Preparation Instructions). The arguments FDR makes in that address reflect the arguments of those who opposed the Lend-Lease Act in 1941. If time permits, discuss:

- How did FDR's attitude towards neutrality change, and how does the "Four Freedoms" speech explain that change?

- Whom is FDR trying to persuade and why?

- What might his opponents have listed as the four most essential freedoms?

Activity 3. Setting the Scene: FDR, Freedom, and Fireside Chats

Franklin Roosevelt ranks among the most gifted orators in American Presidential history. A large part of his reputation for eloquence comes from his institution of regular "fireside chats" with the American public. Families would gather around the radio to hear President Roosevelt offer words of hope, caution, and direction in regular radio broadcasts.

These chats helped Roosevelt cultivate an unmatched rhetorical rapport with the American public. Introduce the class to the idea of the fireside chat, and then read aloud from the chat entitled " Greater Freedom and Greater Security ." Roosevelt closes this speech, which addresses mainly worker's rights and issues of economic security, with the following paragraph:

"I still believe in ideals. I am not for a return to that definition of Liberty under which for many years a free people were being gradually regimented into the service of the privileged few. I prefer and I am sure you prefer that broader definition of Liberty under which we are moving forward to greater freedom, to greater security for the average man than he has ever known before in the history of America."

Within this remark, there is an apparent tension between two alternative definitions of freedom. Discuss this tension with the class:

- What "definition of Liberty" is Roosevelt rejecting?

- How is his own idea of freedom new and different?

- Was the medium of the fireside chat effective in reflecting and communicating Roosevelt's new definition of freedom?

These questions provide a nice introduction to the idea of competing definitions of freedom.

In order to set the scene for the "Four Freedoms" speech, first remind students of the date of the speech: January 6, 1941. You may want to note that the speech was delivered almost exactly 11 months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, at a time when the United States was officially neutral in World War II. If desired, distribute copies of the World War II timeline from the FDR page of the PBS American Experience website.

Now tell students that what they are about to hear was addressed to Congress as part of FDR's 1941 State of the Union speech. Make sure the class has a general idea of the significance of the State of the Union address. If desired, you can familiarize the class with the Constitutional basis of the State of the Union address by reading to them from Article 2, Section 3 of the Constitution, which states:

"He [the President] shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient."

(Note: The Text of the Constitution is available on the EDSITEment resource Educator Resources .) You might also want to ask members of the class who have watched a State of the Union address live to recount their memories of the speech.

Now ask students to imagine that they have all crowded around a radio set in a cozy living room on a cold January day to listen to the President deliver his State of the Union address. Then, have a volunteer read the relevant part of the speech (excerpted above) aloud to the class. Or, for a more dramatic experience, students can actually listen to a recording of FDR himself delivering a few lines from the speech. The recording can be accessed and played from the Four Freedoms section of the Powers of Persuasion exhibit on the EDSITEment-reviewed National Archives websites.