How to Write a Great Synopsis for Thesis

A synopsis is a structured outline of a research thesis and the steps followed to answer the research question. The goal of writing a synopsis is to clearly and thoroughly explain the need to investigate a certain problem using particular practical methods to conduct the study. One of the main components of this written work is an extensive literature review containing strong evidence that the proposed research is feasible.

Establishing the Background

A supervisor may ask you to write a synopsis for one or more reasons:

- to help you improve your critical thinking and writing skills

- to help you understand how to design a comprehensive synopsis

- to encourage you to write a comprehensive literature review to make sure that the research problem has not been answered yet

- to make you conduct a logical analysis of the steps that should be followed to meet the objectives of the research

A synopsis should be coherent in terms of research design. Thus, you should ensure that the research problem, aims, and research methods are logically linked and well-considered. Note that all synopses should contain answers for several crucial questions:

- Why should research on the proposed problem be undertaken?

- What is expected to be achieved?

- What has been done by other researchers on the proposed topic?

- How will the objectives of the study be achieved?

The Writing Process

Before proceeding, consider answering the following questions:

- Why am I going to study this topic?

- Why do I consider it to be important?

- Have I conducted an extensive literature review on the topic?

- What problem will the research help to solve?

- How do I incorporate previous studies on the topic?

The structure of a synopsis should correspond to the structure of qualifying research work, and the word count should be 2,500–3,000 words (Balu 38). The basic elements of a synopsis include a title page, contents page, an introduction, background, literature review, objectives, methods, experiments and results, conclusions, and references.

Introduction

As this comprises the first part of the main text, the introduction should convince readers that the study addresses a relevant topic and that the expected outcomes will provide important insights. Also, this section should include a brief description of the methods that will be used to answer the research question. Usually, the introduction is written in 1–3 paragraphs and answers the following questions:

- What is the topic of the research?

- What is the research problem that needs to be meaningfully understood or investigated?

- Why is the problem important?

- How will the problem be studied?

In this section, you should set the scene and better introduce the research topic by proving its scientific legitimacy and relevance. It is important to establish a clear focus and avoid broad generalizations and vague statements. If necessary, you may explain key concepts or terms. Consider covering the following points in this section:

- Discuss how the research will contribute to the existing scientific knowledge.

- Provide a detailed description of the research problem and purpose of the research.

- Provide a rationale for the study.

- Explain how the research question will be answered.

- Be sure to discuss the methods chosen and anticipated implications of the research.

Literature Review

A review of existing literature is an important part of a synopsis, as it:

- gives a more detailed look at scientific information related to the topic

- familiarizes readers with research conducted by others on a similar subject

- gives insight into the difficulties faced by other researchers

- helps identify variables for the research based on similar studies

- helps double-check the feasibility of the research problem.

When writing the literature review, do not simply present a list of methods researchers have used and conclusions they have drawn. It is important to compare and contrast different opinions and be unafraid to criticize some of them. Pay attention to controversial issues and divergent approaches used to address similar problems. You may discuss which arguments are more persuasive and which methods and techniques seem to be more valid and reliable. In this section, you are expected not to summarize but analyze the previous research while remembering to link it to your own purpose.

Identify the objectives of the research based on the literature review. Provide an overall objective related to the scientific contribution of the study to the subject area. Also include a specific objective that can be measured at the end of the research.

When writing this section, consider that the aim of the research is to produce new knowledge regarding the topic chosen. Therefore, the research methodology forms the core of your project, and your goal is to convince readers that the research design and methods chosen will rationally answer the research questions and provide effective tools to interpret the results correctly. It may be appropriate to incorporate some examples from your literature review into the description of the overall research design.

When describing the research methodology, ensure that you specify the approaches and techniques that will be used to answer the research question. In addition, be specific about applying the chosen methods and what you expect to achieve. Keep in mind that the methods section allows readers to evaluate the validity and feasibility of the study. Therefore, be sure to explain your decision to adopt specific methods and procedures. It is also important to discuss the anticipated barriers and limitations of the study and how they will be addressed. Specify what kind of contribution to the existing knowledge on the topic is expected, and discuss any ethical considerations that are relevant to the research.

Experiments and Results

Logically present and analyze the results of the study using tables or figures.

In this section, you should again state the significance of the research and summarize the study. Be sure to mention the study objectives and methods used to answer the research questions. Also, discuss how the results of the study contribute to the current knowledge on the problem.

A synopsis should contain a list of all references used. Make sure the references are formatted according to the chosen citation style and each source presented in this section is mentioned within the body of the synopsis.

The purpose of writing a synopsis is to show a supervisor a clear picture of a proposed project and allow him or her to find any gaps that have not been considered previously. A concisely written synopsis will help you gain approval to proceed with the actual research. While no rigid rules for writing this type of paper have been established, a synopsis should be constructed in a manner to help a supervisor understand the proposed research at first glance.

Balu, R. “Writing a Good Ph.D Research Synopsis.” International Journal of Research in Science and Technology, vol. 5, no. 4, 2015, pp. 38–48.

Unfortunately, your browser is too old to work on this site.

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Write a Research Synopsis: Template, Examples, & More

Last Updated: May 9, 2024 Fact Checked

Research Synopsis Template

- Organizing & Formatting

- Writing Your Synopsis

- Reviewing & Editing

This article was reviewed by Gerald Posner and by wikiHow staff writer, Raven Minyard, BA . Gerald Posner is an Author & Journalist based in Miami, Florida. With over 35 years of experience, he specializes in investigative journalism, nonfiction books, and editorials. He holds a law degree from UC College of the Law, San Francisco, and a BA in Political Science from the University of California-Berkeley. He’s the author of thirteen books, including several New York Times bestsellers, the winner of the Florida Book Award for General Nonfiction, and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History. He was also shortlisted for the Best Business Book of 2020 by the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 239,772 times.

A research synopsis describes the plan for your research project and is typically submitted to professors or department heads so they can approve your project. Most synopses are between 3,000 and 4,000 words and provide your research objectives and methods. While the specific types of information you need to include in your synopsis may vary depending on your department guidelines, most synopses include the same basic sections. In this article, we’ll walk you step-by-step through everything you need to know to write a synopsis for research.

Things You Should Know

- Begin your research synopsis by introducing the question your research will answer and its importance to your field.

- List 2 or 3 specific objectives you hope to achieve and how they will advance your field.

- Discuss your methodology to demonstrate why the study design you chose is appropriate for your research question.

Organizing Your Research Synopsis

- Find out what citation format you’re supposed to use, as well as whether you’re expected to use parenthetical references or footnotes in the body of your synopsis.

- If you have questions about anything in your guidelines, ask your instructor or advisor to ensure you follow them correctly.

- Title: the title of your study

- Abstract: a summary of your research synopsis

- Introduction: identifies and describes your research question

- Literature Review: a review of existing relevant research

- Objectives: goals you hope to accomplish through your study

- Hypotheses: results you expect to find through your research

- Methodology and methods: explains the methods you’ll use to complete your study

- References: a list of any references used in citations

Tip: Your synopsis might have additional sections, depending on your discipline and the type of research you're conducting. Talk to your instructor or advisor about which sections are required for your department.

- Keep in mind that you might not end up using all the sources you initially found. After you've finished your synopsis, go back and delete the ones you didn't use.

Writing Your Research Synopsis

- Your title should be a brief and specific reflection of the main objectives of your study. In general, it should be under 50 words and should avoid unneeded phrases like “an investigation into.”

- On the other hand, avoid a title that’s too short, as well. For example, a title like “A Study of Urban Heating” is too short and doesn’t provide any insight into the specifics of your research.

- The introduction allows you to explain to your reader exactly why the question you’re trying to answer is vital and how your knowledge and experience make you the best researcher to tackle it.

- Support most of the statements in your introduction with other studies in the area that support the importance of your question. For example, you might cite a previous study that mentions your problem as an area where further research needs to be done.

- The length of your introduction will vary depending on the overall length of your synopsis as well as the ultimate length of your eventual paper after you’ve finished your research. Generally, it will cover the first page or two of your synopsis.

- For example, try finding relevant literature through educational journals or bulletins from organizations like WHO and CDC.

- Typically, a thorough literature review discusses 8 to 10 previous studies related to your research problem.

- As with the introduction, the length of your literature review will vary depending on the overall length of your synopsis. Generally, it will be about the same length as your introduction.

- Try to use the most current research available and avoid sources over 5 years old.

- For example, an objective for research on urban heating could be “to compare urban heat modification caused by vegetation of mixed species considering the 5 most common urban trees in an area.”

- Generally, the overall objective doesn’t relate to solving a specific problem or answering a specific question. Rather, it describes how your particular project will advance your field.

- For specific objectives, think in terms of action verbs like “quantify” or “compare.” Here, you’re hoping to gain a better understanding of associations between particular variables.

- Specify the sources you used and the reasons you have arrived at your hypotheses. Typically, these will come from prior studies that have shown similar relationships.

- For example, suppose a prior study showed that children who were home-schooled were less likely to be in fraternities or sororities in college. You might use that study to back up a hypothesis that home-schooled children are more independent and less likely to need strong friendship support networks.

- Expect your methodology to be at least as long as either your introduction or your literature review, if not longer. Include enough detail that your reader can fully understand how you’re going to carry out your study.

- This section of your synopsis may include information about how you plan to collect and analyze your data, the overall design of your study, and your sampling methods, if necessary. Include information about the study setting, like the facilities and equipment that are available to you to carry out your study.

- For example, your research work may take place in a hospital, and you may use cluster sampling to gather data.

- Use between 100 and 200 words to give your readers a basic understanding of your research project.

- Include a clear statement of the problem, the main goals or objectives of your study, the theories or conceptual framework your research relies upon, and the methods you’ll use to reach your goals or objectives.

Tip: Jot down a few notes as you draft your other sections that you can compile for your abstract to keep your writing more efficient.

Reviewing and Editing Your Research Synopsis

- If you don’t have that kind of time because you’re up against a deadline, at least take a few hours away from your synopsis before you go back to edit it. Do something entirely unrelated to your research, like taking a walk or going to a movie.

- Eliminate sentences that don’t add any new information. Even the longest synopsis is a brief document—make sure every word needs to be there and counts for something.

- Get rid of jargon and terms of art in your field that could be better explained in plain language. Even though your likely readers are people who are well-versed in your field, providing plain language descriptions shows you know what you’re talking about. Using jargon can seem like you’re trying to sound like you know more than you actually do.

Tip: Free apps, such as Grammarly and Hemingway App, can help you identify grammatical errors as well as areas where your writing could be clearer. However, you shouldn't rely solely on apps since they can miss things.

- Reference list formatting is very particular. Read your references out loud, with the punctuation and spacing, to pick up on errors you wouldn’t have noticed if you’d just read over them.

- Compare your format to the one in the stylebook you’re using and make sure all of your entries are correct.

- Read your synopsis backward by starting on the last word and reading each word separately from the last to the first. This helps isolate spelling errors. Reading backward sentence by sentence helps you isolate grammatical errors without being distracted by the content.

- Print your synopsis and circle every punctuation mark with a red pen. Then, go through them and focus on whether they’re correct.

- Read your synopsis out loud, including the punctuation, as though you were dictating the synopsis.

- Have at least one person who isn’t familiar with your area of study look over your synopsis. If they can understand your project, you know your writing is clear. If any parts confuse them, then that’s an area where you can improve the clarity of your writing.

Expert Q&A

- If you make significant changes to your synopsis after your first or second round of editing, you may need to proofread it again to make sure you didn’t introduce any new errors. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://admin.umt.edu.pk/Media/Site/iib1/FileManager/FORMAT%20OF%20SYNOPSIS%2012-10-2018.pdf

- ↑ https://www.scientificstyleandformat.org/Tools/SSF-Citation-Quick-Guide.html

- ↑ https://numspak.edu.pk/upload/media/Guidelines%20for%20Synopsis%20Writing1531455748.pdf

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279917593_Research_synopsis_guidelines

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

- ↑ https://www.cornerstone.edu/blog-post/six-steps-to-really-edit-your-paper/

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jul 25, 2022

Did this article help you?

Wave Bubble

Aug 31, 2021

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Student blogs and videos

- Why Cambridge

- Qualifications directory

- How to apply

- Fees and funding

- Frequently asked questions

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Visiting the University

- Term dates and calendars

- Video and audio

- Find an expert

- Publications

- International Cambridge

- Public engagement

- Giving to Cambridge

- For current students

- For business

- Colleges & departments

- Libraries & facilities

- Museums & collections

- Email & phone search

- Postgraduate Study in MMLL

Applying & Funding

Writing an MPhil Research Proposal

- About overview

- Governance of the Faculty overview

- Governance at MML

- Faculty Board overview

- Board Overview

- Membership and Contacts

- Student Engagement

- Staff-Student Liaison Committee overview

- Committee Overview

- News & Events

- Academic Visitors

- Public Engagement

- IT Services

- The University Library

- Language Centre

- Research Facilities

- MMLL privacy policy

- Health and Safety at MMLL

- Subjects overview

- Modern Greek

- Spanish and Portuguese

- Slavonic Studies overview

- Slavonic Studies virtual event for Years 11 & 12

- Theoretical and Applied Linguistics

- Undergraduates overview

- The Courses: Key Facts overview

- Course costs

- The courses we offer

- The MML Course overview

- MML: The First Year

- MML: The Second Year

- MML: The Year Abroad

- MML: The Fourth Year

- The Linguistics Course

- The History and Modern Languages Course overview

- Course structure overview

- How We Teach

- How You Learn

- Resources for teachers and supporters

- Careers and Employment

- Alumni testimonials overview

- Matthew Thompson

- Rosie Sargeant

- Mark Austin

- Esther Wilkinson

- Katherine Powlesland

- Gillian McFarland

- Katya Andrusz

- Frequently asked questions overview

- Choosing your course

- Applications

- Resources and reading lists for prospective students

- Did you know...?

- Student Perspectives overview

- Alfie Vaughan

- Romany Whittall

- Postgraduates

- Offer Holders overview

- French overview

- Summer Preparation

- German overview

- Beginners Course overview

- Post A-Level Course overview

- Italian and Greek overview

- Portuguese overview

- Spanish overview

- History & Modern Languages Tripos

- From Our Students

- Current undergraduates overview

- Year Abroad overview

- Current Students

- Thinking about your Year Abroad overview

- Studying overview

- Finance overview

- Turing Scheme

- Safety and Insurance

- Year Abroad FAQs

- Year Abroad Project FAQs

- Modern and Medieval Languages Tripos overview

- MML Part IA List of Papers

- Part I Oral Examination A and B

- MML Part IB List of Papers

- MML IB Assessment by Long Essay

- The Year Abroad Project

- MML Part II List of Papers overview

- MML Part II List of Borrowed Papers

- CS5: The Body

- CS6: European Film

- Oral C Examination

- MML Part II Optional Dissertation

- MML with Classics

- Linguistics within the Modern and Medieval Languages Tripos

- Linguistics Tripos overview

- Linguistics Tripos - List of Papers

- Transferable Skills

- History and Modern Languages Tripos

- Marking Criteria

- Supervision Guidelines

- Teaching Provision

- Examinations Data Retention Policy (PDF)

- Learning Resources

- Additional Course Costs

- Faculty guidance on plagiarism

- Translation Toolkit overview

- 1. Translation as a Process

- 2. Translation as a Product

- 3. Equivalence and Translation Loss

- Email etiquette at MMLL

- Overall Degree Classification

- Current postgraduates

- Research in MMLL overview

- Research by Section overview

- Italian overview

- CIRN Home overview

- CIRN Events overview

- CIRN Annual Lecture 2015

- CIRN Annual Lecture 2016

- CIRN Annual Lecture 2017

- CIRN Annual Lecture 2018

- CIRN Annual Lecture 2019

- CIRN Annual Lecture 2019-20

- CIRN Annual Symposium 2015

- CIRN Annual Symposium 2016

- CIRN Annual Symposium 2017

- CIRN Annual Symposium 2018

- CIRN Annual Symposium 2019

- CIRN News and Events archive

- Slavonic Studies

- Research by Language overview

- Research by Period overview

- Medieval and Pre-Modern

- Early Modern

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- 1900 - 1945

- 1945 - present

- Research by Thematic Field overview

- Literature, Visual Culture and the Arts overview

- Colonial, Postcolonial and Decolonial Studies

- Contemporary Culture and Society

- Drama, Music and Performance

- Environmental Criticism and Posthumanism

- Film and Visual Culture

- Gender, Feminism and Queer Studies

- Intellectual and Cultural History

- Literary Theory, Philosophy and Political Thought

- Material Culture and History of the Book

- Poetry, Rhetoric and Poetics

- Language and Linguistics overview

- Comparative Syntax

- Computational Linguistics

- Dialectology

- Experimental Phonetics and Phonology

- Historical Linguistics

- Language Acquisition

- Language Change

- Language Contact

- Multilingualism

- Psycholinguistics

- Semantics, Pragmatics and Philosophy

- Translation Theory and Practice

- Funded Projects

- Apply for Research Funding overview

- Research Strategy Committee

- Leverhulme Early Career Fellowships

- British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowships

- Management of Ongoing Grants

- Funding Opportunities

- Centres overview

- Cambridge Film and Screen

- Cambridge Italian Research Network (CIRN)

- Centre of Latin American Studies (CLAS)

- Cambridge Language Sciences

- Cambridge Endangered Languages and Cultures Group (CELC) overview

- Seminar Series

- Past conferences

- Cambridge Centre for Greek Studies

- Centre for the Study of Global Human Movement

- Equality and Diversity overview

- EDI Committee

- Accessibility Statement

- Accessible Materials

- Recording Lectures

- Athena SWAN

- Mentoring and Career Development

- Parents and Carers

- EDI Related Links

- Harassment and Discrimination

- Outreach overview

- Resources overview

- Open Day Resources for Prospective Students

- CCARL A-level Resources overview

- Why Not Languages? resources overview

- Student Q&A

- Events for Students overview

- Events for Teachers overview

- Diversity in French and Francophone Studies: A CPD workshop series for teachers of French

- Diversity in German Studies - CPD Workshop series aimed at secondary teachers of German

- Workshop for Spanish Teachers

- Workshop for Teachers of German: Diversity in German Culture

- Access and Widening Participation

- Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages and Linguistics

- Applying: MPhil in Euro, LatAm, Comp Lit and Cultures

- Applying: MPhils in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics

- Applying: MPhils in Film and Screen Studies

- Applying: PhD

- PG Guide for applicants

- Writing an MPhil research proposal

- Mallinson MPhil Studentship (ELAC)

- Scandinavian Studies Fund

- Postgraduate Study

- MPhil Courses

- PhD Courses

- Postgraduate Committees

- Cambridge Virtual Postgraduate Open Days

- Visitors and Erasmus

- Information for current Students

- Postdoctoral Affiliation

- Consortium in Latin American Cultural Studies

- Postgraduate Contacts

- Current student profiles

Your MPhil research proposal should be approximately one page in length.

- Your research proposal should clearly articulate what you want to research and why. It should indicate a proposed approach to your given field of study. It should nevertheless retain sufficient flexibility to accommodate any changes you need to make as your research progresses.

- You should try to show how your postgraduate plans emerge from your undergraduate work and may move it on.

- You should try to show how your proposed research will build on existing knowledge or address any gaps or shortcomings. You should accordingly mention existing scholarship, if necessary with certain qualifications – (eg. ‘Smith has written extensively on the theatre of Pirandello, but fails to mention…).

- Identify a potential Supervisor.

Search form

Related links.

- Student Support

- Wellbeing at Cambridge

- Year Abroad FAQ

- Polyglossia Magazine

- The Cambridge Language Collective

- Information for current undergraduates

- Visiting and Erasmus Students

Keep in touch

- University of Cambridge Privacy Policy

- Student complaints and Examination Reviews

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- University A-Z

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Terms and conditions

- Undergraduate

- Spotlight on...

- About research at Cambridge

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.4: Writing Introductory and Concluding Paragraphs

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 20635

- Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Picture your introduction as a storefront window: You have a certain amount of space to attract your customers (readers) to your goods (subject) and bring them inside your store (discussion). Once you have enticed them with something intriguing, you then point them in a specific direction and try to make the sale (convince them to accept your thesis).

Your introduction is an invitation to your readers to consider what you have to say and then to follow your train of thought as you expand upon your thesis statement.

An introduction serves the following purposes:

- Establishes your voice and tone, or your attitude, toward the subject

- Introduces the general topic of the essay

- Relates the topic to the reader

- States the thesis that will be supported in the body paragraphs

First impressions are crucial and can leave lasting effects in your reader’s mind, which is why the introduction is so important to your essay. If your introductory paragraph is dull or disjointed, your reader probably will not have much interest in continuing with the essay.

Attracting Interest in Your Introductory Paragraph

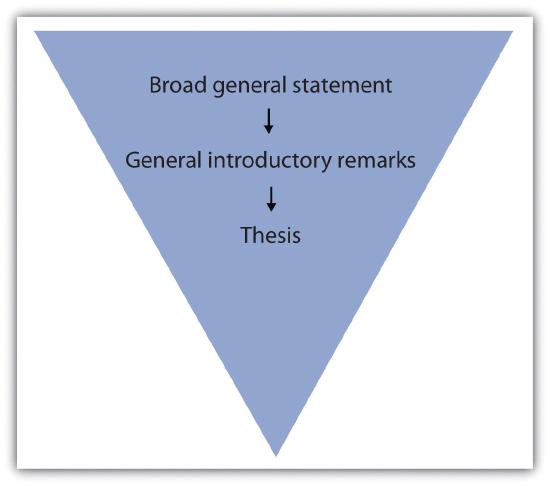

Your introduction should begin with an engaging statement devised to provoke your readers’ interest. It should also relate to your stance on the topic. In the next few sentences, introduce your reader to the topic by stating general facts or ideas about the subject. As you move deeper into your introduction, you gradually narrow the focus, moving closer to your thesis. Moving smoothly and logically from your introductory remarks to your thesis statement can be achieved using a funnel technique, as illustrated in the following diagram.

On a separate sheet of paper, jot down a few general remarks that you can make about the topic for which you formed a thesis in Section 5.1, " Developing a Strong, Clear Thesis Statement ."

Immediately capturing your readers’ interest increases the chances of having them read what you are about to discuss. You can garner curiosity for your essay in a number of ways. Try to get your readers personally involved by doing any of the following:

- Appealing to their emotions

- Using logic

- Beginning with a provocative question or opinion

- Opening with a startling statistic or surprising fact

- Raising a question or series of questions

- Presenting an explanation or rationalization for your essay

- Opening with a relevant quotation or incident

- Opening with a striking image

- Including a personal anecdote

Some other ideas are:

- If the topic is controversial, you can include the current state of the controversy. If there is a lot of history to the topic, you can summarize the history.

- If you are writing a personal essay, you can begin with a brief personal anecdote.

- If you are writing an essay that is focused on one or two works (of literature or nonfiction), you can introduce those works with the title(s), author(s), and brief information about those works.

- Describe a brief event that you think illustrates the overall point you want to make with your essay.

- State an interesting fact that others may not know.

- State a shocking but relevant statistic.

- Compare what people generally think to what the reality is.

The Role of Introductions

Introductions and conclusions can be the most difficult parts of papers to write. Usually when students sit down to respond to an assignment, they have at least some sense of what they want to say in the body of the paper. They might have chosen a few examples or have an idea that will help them answer the main question of your assignment: these sections, therefore, are not as hard to write. But these middle parts of the paper can’t just come out of thin air at the reader; they need to be introduced and concluded in a way that makes sense to the reader.

The introduction and conclusion act as bridges that transport readers from their own lives into the “place” of the writer’s analysis. If the readers pick up a paper about education in the autobiography of Frederick Douglass, for example, they need a transition to help them leave behind the world of California, YouTube, e-mail, etc. and to help them temporarily enter the world of nineteenth-century American slavery. By providing an introduction that helps readers make a transition between their own world and the issues in the paper, writers give their readers the tools they need to get into the topic and care about what they are reading. (See this handout on conclusions .)

The trick about how general to begin is to think about your audience. Write a first sentence that everyone can both to your topic and they can relate to personally. Now, how you present that topic – be it a question, a humorous statement, an interesting statistic or a shocking fact – depends on what you think is appropriate for your audience.

Image by Helena Lopes from Pexels

Why Bother Writing a Good Introduction?

You never get a second chance to make a first impression . The opening paragraph of a paper will provide readers with their initial impressions of the argument, the writing style, and the overall quality of work. A vague, disorganized, error-filled, off-the-wall, or boring introduction will probably create a negative impression. On the other hand, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will start your readers off thinking highly of the writer, his analytical skills, the writing, and the paper overall.

Your introduction is an important road map for the rest of your paper . The introduction conveys a lot of information to the readers. They are introduced to the topic, why it is important, and how the topic will be discussed and developed. It also introduces your tone and stance about the topic. In most academic disciplines, the introduction should contain a thesis that will assert the main argument. It should also, ideally, give the reader a sense of the kinds of information used to make that argument and the general organization of the paragraphs and pages that will follow. After reading the introduction, readers should not have any major surprises in store when they read the main body of the paper.

Ideally, your introduction will make your readers want to read your paper . The introduction should capture the readers’ interest, making them want to read the rest of the paper. Opening with a compelling story, a fascinating quotation, an interesting question, or a stirring example can get readers to see why this topic matters and serve as an invitation for them to join an interesting intellectual conversation.

Guidelines: Writing Effective Introductions

1. Start by thinking about the question (or questions) you are trying to answer . Your entire essay will be a response to this question, and your introduction is the first step toward that end. Your direct answer to the assigned question will be your thesis, and your thesis will be included in your introduction, so it is a good idea to use the question as a jumping off point. Imagine that you are assigned the following question:

Education has long been considered a major force for American social change, righting the wrongs of our society. Drawing on the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, discuss the relationship between education and slavery in 19th-century America. Consider the following: How did white control of education reinforce slavery? How did Douglass and other enslaved African Americans view education while they endured slavery? And what role did education play in the acquisition of freedom? Most importantly, consider the degree to which education was or was not a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

You will probably refer back to your assignment extensively as you prepare your complete essay, and the prompt itself can also give you some clues about how to approach the introduction. Notice that it starts with a broad statement, that education has been considered a major force for social change, and then narrows to focus on specific questions from the book. One strategy might be to use a similar model in your own introduction —start off with a big picture sentence or two about the power of education as a force for change as a way of getting your reader interested and then focus in on the details of your argument about Douglass. Of course, a different approach could also be very successful, but looking at the way the professor set up the question can sometimes give you some ideas for how you might answer it.

2. Decide how general or broad your opening should be. Keep in mind that even a “big picture” opening needs to be clearly related to your topic; an opening sentence that said “Human beings, more than any other creatures on earth, are capable of learning” would be too broad for our sample assignment about slavery and education. If you have ever used Google Maps or similar programs, that experience can provide a helpful way of thinking about how broad your opening should be. The question you are asking determines how “broad” your view should be. In the sample assignment above, the questions are probably at the “state” or “city” level of generality. But the introductory sentence about human beings is mismatched—it’s definitely at the “global” level. When writing, you need to place your ideas in context—but that context doesn’t generally have to be as big as the whole galaxy!

3. Try writing your introduction last . You may think that you have to write your introduction first, but that isn’t necessarily true, and it isn’t always the most effective way to craft a good introduction. You may find that you don’t know what you are going to argue at the beginning of the writing process, and only through the experience of writing your paper do you discover your main argument. It is perfectly fine to start out thinking that you want to argue a particular point, but wind up arguing something slightly or even dramatically different by the time you’ve written most of the paper. The writing process can be an important way to organize your ideas, think through complicated issues, refine your thoughts, and develop a sophisticated argument. However, an introduction written at the beginning of that discovery process will not necessarily reflect what you wind up with at the end. You will need to revise your paper to make sure that the introduction, all of the evidence, and the conclusion reflect the argument you intend. Sometimes it’s easiest to just write up all of your evidence first and then write the introduction last—that way you can be sure that the introduction will match the body of the paper and don't run out of time to revise your introduction.

4. Don’t be afraid to write a tentative introduction first and then change it later. Some people find that they need to write some kind of introduction in order to get the writing process started. That’s fine, but if you are one of those people, be sure to return to your initial introduction later and rewrite if necessary.

5. Open with an attention grabber. Sometimes, especially if the topic of your paper is somewhat dry or technical, opening with something catchy can help. Consider these options:

- an intriguing example (for example, the mistress who initially teaches Douglass but then ceases her instruction as she learns more about slavery)

- a provocative quotation (Douglass writes that “education and slavery were incompatible with each other”)

- a puzzling scenario (Frederick Douglass says of slaves that “[N]othing has been left undone to cripple their intellects, darken their minds, debase their moral nature, obliterate all traces of their relationship to mankind; and yet how wonderfully they have sustained the mighty load of a most frightful bondage, under which they have been groaning for centuries!” Douglass clearly asserts that slave owners went to great lengths to destroy the mental capacities of slaves, yet his own life story proves that these efforts could be unsuccessful.)

- a vivid and perhaps unexpected anecdote (for example, “Learning about slavery in the American history course at Frederick Douglass High School, students studied the work slaves did, the impact of slavery on their families, and the rules that governed their lives. We didn’t discuss education, however, until one student, Mary, raised her hand and asked, ‘But when did they go to school?’ That modern high school students could not conceive of an American childhood devoid of formal education speaks volumes about the centrality of education to American youth today and also suggests the significance of the deprivation of education in past generations.”)

- a thought-provoking question (given all of the freedoms that were denied enslaved individuals in the American South, why does Frederick Douglass focus his attentions so squarely on education and literacy?)

6. Pay special attention to your first sentence . Start off on the right foot with your readers by making sure that the first sentence actually says something useful and that it does so in an interesting and error-free way.

7. Be straightforward and confident . Avoid statements like “In this paper, I will argue that Frederick Douglass valued education.” While this sentence points toward your main argument, it isn’t especially interesting. It might be more effective to say what you mean in a declarative sentence. It is much more convincing to tell us that “Frederick Douglass valued education” than to tell us that you are going to say that he did. Assert your main argument confidently. After all, you can’t expect your reader to believe it if it doesn’t sound like you believe it!

How to Evaluate Your Introduction?

Ask a friend to read it and then tell you what he or she expects the paper will discuss, what kinds of evidence the paper will use, and what the tone of the paper will have. If your friend is able to predict the rest of your paper accurately and wants to keep reading, you probably have a good introduction.

Guidelines: Avoiding Less Effective Introductions

1. The place holder introduction . When you don’t have much to say on a given topic, it is easy to create this kind of introduction. Essentially, this kind of weaker introduction contains several sentences that are vague and don’t really say much. They exist just to take up the “introduction space” in your paper. If you had something more effective to say, you would probably say it, but in the meantime this paragraph is just a place holder. This may what you write just to get yourself writing, but be sure to go back and revise it.

Example: Slavery was one of the greatest tragedies in American history. There were many different aspects of slavery. Each created different kinds of problems for enslaved people.

2. The restated question introduction. Restating the question can sometimes be an effective strategy, but it can be easy to stop at JUST restating the question instead of offering a more specific, interesting introduction to your paper. The professor or teaching assistant wrote your questions and will be reading ten to seventy essays in response to them—thye do not need to read a whole paragraph that simply restates the question. Try to do something more interesting.

Example: Indeed, education has long been considered a major force for American social change, righting the wrongs of our society. The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass discusses the relationship between education and slavery in 19th century America, showing how white control of education reinforced slavery and how Douglass and other enslaved African Americans viewed education while they endured. Moreover, the book discusses the role that education played in the acquisition of freedom. Education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

3. The Dictionary introduction. This introduction begins by giving the dictionary definition of one or more of the words in the assigned question. This introduction strategy is on the right track—if you write one of these, you may be trying to establish the important terms of the discussion, and this move builds a bridge to the reader by offering a common, agreed-upon definition for a key idea. You may also be looking for an authority that will lend credibility to your paper. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and copy down what it says—it may be far more interesting for you (and your reader) if you develop your own definition of the term in the specific context of your class and assignment, or if you use a definition from one of the sources you’ve been reading for class. Also recognize that the dictionary is also not a particularly authoritative work—it doesn’t take into account the context of your course and doesn’t offer particularly detailed information. If you feel that you must seek out an authority, try to find one that is very relevant and specific. Perhaps a quotation from a source reading might prove better? Dictionary introductions are also ineffective simply because they are so overused. Many teachers will see twenty or more papers that begin in this way, greatly decreasing the dramatic impact that any one of those papers will have.

Example: Webster’s dictionary defines slavery as “the state of being a slave,” as “the practice of owning slaves,” and as “a condition of hard work and subjection.”

4. The “dawn of man” introduction. This kind of introduction generally makes broad, sweeping statements about the relevance of this topic since the beginning of time. It is usually very general (similar to the place holder introduction) and fails to connect to the thesis. You may write this kind of introduction when you don’t have much to say—which is precisely why it is ineffective.

Example: Since the dawn of man, slavery has been a problem in human history.

5. The book report introduction. This introduction is what you had to do for your elementary school book reports. It gives the name and author of the book you are writing about, tells what the book is about, and offers other basic facts about the book. You might resort to this sort of introduction when you are trying to fill space because it’s a familiar, comfortable format. It is ineffective because it offers details that your reader already knows and that are irrelevant to the thesis.

Example: Frederick Douglass wrote his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, in the 1840s. It was published in 1986 by Penguin Books. In it, he tells the story of his life.

Remember that your diction, or word choice, while always important, is most crucial in your introductory paragraph. Boring diction could extinguish any desire a person might have to read through your discussion. Choose words that create images or express action. For more information on diction, or word choice, see Chapter 11, "Clarity, Conciseness, and Style ."

See a student's introduction below with the thesis statement underlined. What do you think of it?

Play Atari on a General Electric brand television set? Maybe watch Dynasty? Or read old newspaper articles on microfiche at the library? Thirty-five years ago, the average college student did not have many options when it came to entertainment in the form of technology. Fast-forward to the twenty-first century, and the digital age has digital technology, consumers are bombarded with endless options for how they do most everything--from buying and reading books to taking and developing photographs. In a society that is obsessed with digital means of entertainment, it is easy for the average person to become baffled. Everyone wants the newest and best digital technology, but the choices are many and the specifications are often confusing.

If you have trouble coming up with a provocative statement for your opening, it is a good idea to use a relevant, attention-grabbing quote about your topic. Use a search engine to find statements made by historical or significant figures about your subject.

Writing at Work

In your job field, you may be required to write a speech for an event, such as an awards banquet or a dedication ceremony. The introduction of a speech is similar to an essay because you have a limited amount of space to attract your audience’s attention. Using the same techniques, such as a provocative quote or an interesting statistic, is an effective way to engage your listeners. Using the funnel approach also introduces your audience to your topic and then presents your main idea in a logical manner.

Reread each sentence in Andi’s introductory paragraph. Indicate which techniques they used and comment on how each sentence is designed to attract the readers’ interest.

Image by Ann H from Pexels

Writing a Conclusion

It is not unusual to want to rush when you approach your conclusion, and even experienced writers may fade. But what good writers remember is that it is vital to put just as much attention into the conclusion as in the rest of the essay. After all, a hasty ending can undermine an otherwise strong essay.

A conclusion that does not correspond to the rest of your essay, has loose ends, or is unorganized can unsettle your readers and raise doubts about the entire essay, just like a book with an ambiguous ending. However, if you have worked hard to write the introduction and body, your conclusion can often be the most logical part to compose.

Many times, writers find that they write a stronger main idea at the beginning of a conclusion on their first draft than they wrote initially. Sometimes this main idea would make a better thesis than what you may have originally had.

The Anatomy of a Strong Conclusion

Keep in mind that the ideas in your conclusion must conform to the rest of your essay. In order to tie these components together, restate your thesis at the beginning of your conclusion in other words. This helps you assemble, in an orderly fashion, all the information you have explained in the body. Rephrasing your thesis reminds your readers of the major arguments you have been trying to prove and also indicates that your essay is drawing to a close. A strong conclusion also reviews your main points in general and emphasizes the importance of the topic. It may also look to the future regarding your topic.

Conclusions are almost opposite in structure from introductions. Conclusions generally start off with your main point (a reworded thesis) and then become more general. Many times, in addition to making a final statement about your main ideas, a conclusion will “look to the future” by discussing how the author hopes this topic will be treated in the future. Other times, a conclusion includes a solution if the essay discusses a problem, or what additional study needs to be done about the topic (especially in research papers). It can also discuss how what your essay is about is relevant in other parts of the world or domains of study.

Many writers like to end their essays with a final emphatic statement. This strong closing statement will cause your readers to continue thinking about the implications of your essay; it will make your conclusion, and thus your essay, more memorable. Another powerful technique is to challenge your readers to make a change in either their thoughts or their actions. Challenging your readers to see the subject through new eyes is a powerful way to ease yourself and your readers out of the essay.

- When closing your essay, do not expressly state that you are drawing to a close. Relying on statements such as in conclusion , it is clear that , as you can see , or in summation is unnecessary and can be considered trite because the reader can obviously see that it's the end of your essay.

- Introducing new material

- Contradicting your thesis

- Changing your thesis

- Using apologies or disclaimers

Introducing new material in your conclusion has an unsettling effect on your reader. When you raise new points, you make your reader want more information, which you could not possibly provide in the limited space of your final paragraph.

Contradicting or changing your thesis statement causes your readers to think that you do not actually have a conviction about your topic. After all, you have spent several paragraphs adhering to a singular point of view. When you change sides or open up your point of view in the conclusion, your reader becomes less inclined to believe your original argument.

By apologizing for your opinion or stating that you know it is tough to digest, you are in fact admitting that even you know what you have discussed is irrelevant or unconvincing. You do not want your readers to feel this way. Effective writers stand by their thesis statement and do not stray from it.

Exercise 3\(\PageIndex{3}\)

On a separate sheet of a paper, restate your thesis from Exercise 2 of this section and then make some general concluding remarks. Next, compose a final emphatic statement. Finally, incorporate what you have written into a strong conclusion paragraph for your essay.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers

Andi incorporates some of these pointers into their conclusion by paraphrasing their thesis statement in the first sentence.

In a society fixated on the latest and smartest digital technology, a consumer can easily become confused by the countless options and specifications. The ever-changing state of digital technology challenges consumers with its updates and add-ons and expanding markets and incompatible formats and restrictions–a fact that is complicated by salesmen who want to sell them anything. In a world that is increasingly driven by instant gratification, it’s easy for people to buy the first thing they see. The solution for many people should be to avoid buying on impulse. Consumers should think about what they really need, not what is advertised.

Make sure your essay is balanced by not having an excessively long or short introduction or conclusion. Check that they match each other in length as closely as possible, and try to mirror the formula you used in each. Structural parallelism strengthens the message of your essay.

On the job you may sometimes give oral presentations based on research you have conducted. A concluding statement to an oral report contains the same elements as a written conclusion. You should wrap up your presentation by restating the

purpose of the presentation, reviewing its main points, and emphasizing the importance of the material you presented. A strong conclusion will leave a lasting impression on your audience.

Contributors and Attributions

- Adapted from Writing for Success. Provided by: The Saylor Foundation. License: CC-NC-SA 3.0

- Introductions . Provided by: UNC Writing Center. License: CC BY-NC-ND

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CONTENT

" Writing Introductions and Conclusions in an Essay ." Authored by: Karen Hamilton. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

This page most recently updated on June 23, 2020.

- Interesting

- Scholarships

- UGC-CARE Journals

Eight Effective Tips to Overcome Writer’s Block in PhD Thesis Writing

Conquer Your Thesis: 8 Proven Tips to Beat PhD Writer's Block

Are you a Master’s student or PhD scholar struggling with writer’s block in your academic journey? Don’t worry; you’re not alone. Even I struggled during my research journey due to writer’s block. Many of us experience this at some point of time in our academic career, especially when writing our research paper or thesis. In this article, iLovePhD will provide you with eight useful and realistic tips to overcome writer’s block. I am sure that these tips will help you to complete your research paper or thesis writing successfully.

Struggling to write your PhD thesis or master’s dissertation? Feeling stuck and overwhelmed? You’re not alone! Dr. Sowndarya, a PhD graduate herself, shares 8 powerful strategies to overcome writer’s block and get those words flowing. Learn practical tips for structuring your writing, managing your time, and staying motivated. Read now and conquer your thesis!

What is writer’s block?

- Writer’s block is a common condition that affects many writers, including academic writers.

- It is considered a temporary inability to write or create new content, even when the writer wishes to write.

- It can be caused by many factors, such as stress, anxiety, fear of failure, lack of motivation, or even perfectionism.

How to Overcome Writer’s Block in PhD Research?

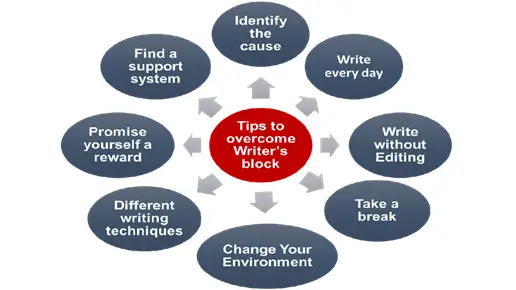

Here are eight useful tips to help you overcome writer’s block in research paper or thesis writing:

1. Identify the cause

The first step in overcoming writer’s block is to identify the cause. Is it due to stress or anxiety or lack of motivation, or something else? Once you identify the cause, you can work on it accordingly.

Extra Tips: Some common causes of writer’s block include:

- Lack of inspiration : Running out of ideas or struggling to find a spark to start writing.

- Fear of failure : The pressure to produce perfect content can lead to anxiety and writer’s block.

- Perfectionism : Setting extremely high standards can make it difficult to start or continue writing.

- Distractions : External or internal distractions, such as social media, email, or self-doubt, can disrupt the writing flow.

- Burnout : Physical, mental, or emotional exhaustion can make it challenging to focus and write.

- Unclear goals or expectations : Lack of clarity about the writing project or audience can lead to uncertainty and writer’s block.

- Research overload : Too much research or information can overwhelm and stall the writing process.

- Personal issues : Life events, stress, or emotional struggles can affect motivation and ability to write.

- Writing habits : Poor writing habits, such as procrastination or inconsistent writing schedules, can contribute to writer’s block.

2. Write every day

Set a manageable target for yourself. Some scholars prefer to work on a time basis. For those of you, my suggestion is, to try to write for 2 hours per day. Ie., 1 hour in the morning and 1 hour in the evening or frame a suitable schedule that works best for you and stick to it.

Some scholars prefer to have several page counts. For those of you, fix a target to complete 1 page per day. The key is you need to be consistent. The next day you need to have the motivation to write for 1 hour or 1 page, or whatever target you have set for yourself. Don’t worry about the format or the style.

It is easier to edit than to start from scratch. So, just keep the words flowing and avoid skipping even one day. If you skip, then the next day will be even harder.

Extra Tips: Writing daily can help overcome writer’s block in several ways:

- Develops writing habit : Regular writing trains your brain to get into a writing mindset, making it easier to start writing.

- Warm-up exercises : Daily writing can include warm-up exercises like freewriting, journaling, or prompts to get your creative juices flowing.

- Builds momentum : Consistent writing helps build momentum, making it easier to tackle larger writing projects.

- Reduces pressure : Writing daily can reduce the pressure to produce perfect content, allowing you to focus on the process rather than the outcome.

- Increases ideas : Daily writing can help generate new ideas and perspectives, helping to overcome writer’s block.

- Improves writing skills : Regular writing practice improves writing skills, boosting confidence and reducing writer’s block.

3. Write without Editing

One of the main causes of writer’s block is perfectionism. So, to overcome this, try to write without revising or editing. Focus on getting your ideas on paper first, and not worry about grammar, structure, and format as the first draft doesn’t have to be perfect. This tip will help you overcome the fear of producing perfect content and allow your ideas to emerge freely.

Extra Tips: Writing without editing can help overcome writer’s block in several ways:

- Silences inner critic : By not editing, you quiet your inner critic, allowing yourself to focus on the creative process rather than perfection.

- Increases flow : Writing without editing helps maintain a fluid writing pace, keeping ideas flowing and momentum building.

- Reduces pressure : Letting go of the need for perfection reduces pressure, making it easier to start writing and keep writing.

- Fosters creativity : Writing without editing allows your ideas to flow freely, without self-censorship, leading to new insights and perspectives.

- Builds confidence : By writing freely, you develop confidence in your writing abilities, helping to overcome writer’s block.

To write without editing:

- Set a timer for a specific writing period (e.g., 25 minutes)

- Write without stopping or looking back

- Ignore grammar, spelling, and punctuation

- Focus on getting your ideas down

- Refrain from deleting or revising

- Embrace the imperfections and keep writing!

4. Take a break

One of the important tips is taking a break: Sometimes, stepping away from your writing for a short period can help you clear your mind and provide you with a fresh perspective. Engage in activities that make you feel good or stimulate your creativity, such as meditation, going for a walk, reading a book, or listening to music. You know, at times, eating your favorite food will make you feel good and relaxed. So, the goal is to generate momentum and overcome the mental blocks.

Extra Tips: Taking a break can be an effective way to overcome writer’s block. Sometimes, stepping away from your work can help you:

- Clear your mind : A break can help you relax and clear your thoughts, making it easier to approach your writing with a fresh perspective.

- Recharge your energy : Taking a break can help you regain your mental and physical energy, reducing fatigue and increasing focus.

- Gain new insights : Stepping away from your writing can give you time to reflect and gain new insights, helping you approach your work with renewed creativity.

- Come back to your work with a fresh perspective : A break can help you see your work from a new angle, making it easier to identify solutions to any challenges you’re facing.

Some ideas for taking a break include:

- Going for a walk or doing some exercise

- Practicing meditation or deep breathing

- Engaging in a creative activity unrelated to writing (e.g., drawing, painting, or playing music)

- Reading a book or watching a movie

- Taking a nap or getting a good night’s sleep

5. Change Your Environment

Find a place where you can sit and write peacefully and most importantly free from distractions. Distractions can make it difficult to focus on writing. So, turning off your mobile phone is important while writing your thesis. In my case, I did all my writing work in my University Library, where I was able to think and write peacefully without any disturbance and distractions. So, you can also try to find a place in your University Library for writing your research paper or thesis.

I’m telling you; you can realize the magic. Very quickly you will start to associate this place with writing. Your thoughts and ideas will automatically turn into your research paper or thesis.

Extra Tips: Changing your environment can be a great way to overcome writer’s block. A new setting can:

- Stimulate creativity : A change of scenery can inspire fresh ideas and perspectives.

- Break routine : A new environment can disrupt your usual routine and help you approach your writing with a renewed sense of purpose.

- Reduce distractions : Sometimes, a change of environment can help you escape distractions and focus on your writing.

- Boost productivity : A new setting can energize your writing session and help you stay focused.

Some ideas for changing your environment include:

- Writing in a different room or location in your home

- Working from a coffee shop, library, or co-working space

- Writing outdoors or in a park

- Trying a writing retreat or workshop

- Even just rearranging your writing space or desk

6. Different writing techniques

Then try to experiment with different writing techniques, such as mind mapping, outlining, or summarizing. Find the method that works best for you to organize your ideas and overcome the block in your writing. Have a habit of using sticky notes. You can randomly make notes on it and from that you can develop your writing.

Extra Tips: Trying different writing techniques can help overcome writer’s block by:

- Shaking up your routine : Experimenting with new techniques can break you out of your usual writing habits and stimulate creativity.

- Discovering new perspectives : Different techniques can help you approach your writing from fresh angles and uncover new ideas.

- Building writing muscles : Practicing various techniques can improve your writing skills and boost confidence.

- Keeping your writing fresh : Trying new techniques can prevent your writing from becoming stale and predictable.

Some techniques to try:

- Freewriting : Write without stopping or editing.

- Stream-of-consciousness : Write your thoughts as they come.

- Dialogue-only writing : Focus on conversations between characters.

- Description-only writing : Concentrate on descriptive passages.

- Writing prompts : Use exercises or prompts to generate ideas.

- Writing sprints : Set timers and write in short, focused bursts.

- Reverse writing : Start with the conclusion and work backward.

- Sense memory writing : Use sensory details to evoke memories and inspiration.

7. Find a support system

As far as PhD research is concerned, you need a driving force to move forward. Traveling through this journey is a bit tough. All the time you need to be motivated. So, talk to your advisor, friends, and even your parents about your difficulties. They may provide valuable insights and suggestions to overcome it. Also, you can join writing groups, workshops, or online forums where you can connect with fellow PhD scholars who are sailing in the same boat.

Extra Tips: Having a support system can be a great way to overcome writer’s block. A support system can:

- Offer encouragement : Help you stay motivated and confident.

- Provide feedback : Give you new insights and perspectives on your writing.

- Hold you accountable : Help you stay on track and meet deadlines.

- Share experiences : Relate to your struggles and offer valuable advice.

Some ways to find a support system:

- Writing groups : Join online or in-person groups to connect with fellow writers.

- Writing buddies : Find a writing partner to share work and provide feedback.

- Writing coaches : Hire a coach to guide and support you.

- Online communities : Join forums, social media groups, or writing platforms.

- Writing workshops : Attend conferences, retreats, or online workshops.

- Beta readers : Share your work with trusted readers for feedback.

8. Promise yourself a reward

And the last tip is rewarding yourself. After completing every task or milestone, reward yourself. Celebrate your progress. It need not be in a grandeur manner. But you can do things which make you feel happy and energetic. This kind of motivation will automatically turn your efforts into a research paper or thesis. As you make progress, you will look forward to finishing your targets.

Extra Tips: Promising yourself a reward can be a great motivator to overcome writer’s block! By setting a goal and rewarding yourself when you achieve it, you can:

- Stay motivated : Give yourself a reason to keep writing and push through challenges.

- Celebrate progress : Acknowledge and celebrate your accomplishments.

- Boost creativity : Take a break and do something enjoyable to refresh your mind.

Some ideas for rewards:

- Time off : Take a break to relax, read, or watch a movie.

- Favorite activities : Do something you enjoy, like hiking, drawing, or cooking.

- Treats : Indulge in your favorite snacks or desserts.

- Personal pampering : Get a massage, take a relaxing bath, or get a good night’s sleep.

- Creative indulgences : Buy a new book, try a new writing tool, or take a writing workshop.

Writer’s block can be a frustrating and challenging experience but don’t allow it to demotivate your research paper or thesis writing. And most importantly, take care of your physical and mental health. When your body and mind are in good shape, it can impact your writing. Embrace this process, trust in your abilities, and remember that every word written brings you one step closer to your dream. You will certainly forget this pain and struggle, when you walk across that stage to get your PhD degree, and when someone calls you “Doctor” for the very first time.

Eight important tips and tricks to overcome writer’s block are discussed in the article. So, when you experience writer’s block in your thesis writing, don’t panic. Remember these tips and try to follow them. You will be able to overcome it and complete your research paper or thesis writing successfully.

Happy Researching!

- Academic Writing

- Dissertation

- Journal Writing

- productivity

- Research Paper

- student tips

- writer's block

5 Free Data Analysis and Graph Plotting Software for Thesis

6 best online chemical drawing software 2024, how to write a research paper in a month, most popular, the hrd scheme india 2024-25, imu-simons research fellowship program (2024-2027), india science and research fellowship (isrf) 2024-25, example of abstract for research paper – tips and dos and donts, photopea tutorial – online free photo editor for thesis images, list of phd and postdoc fellowships in india 2024, google ai for phd research – tools and techniques, best for you, 24 best free plagiarism checkers in 2024, what is phd, popular posts, how to check scopus indexed journals 2024, how to write a research paper a complete guide, popular category.

- POSTDOC 317

- Interesting 258

- Journals 234

- Fellowship 130

- Research Methodology 102

- All Scopus Indexed Journals 92

iLovePhD is a research education website to know updated research-related information. It helps researchers to find top journals for publishing research articles and get an easy manual for research tools. The main aim of this website is to help Ph.D. scholars who are working in various domains to get more valuable ideas to carry out their research. Learn the current groundbreaking research activities around the world, love the process of getting a Ph.D.

Contact us: [email protected]

Google News

Copyright © 2024 iLovePhD. All rights reserved

- Artificial intelligence

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The structure of a synopsis should correspond to the structure of qualifying research work, and the word count should be 2,500-3,000 words (Balu 38). The basic elements of a synopsis include a title page, contents page, an introduction, background, literature review, objectives, methods, experiments and results, conclusions, and references.

FORMAT OF SYNOPSIS (MS/MPHIL & PHD) Given below is an outline for synopsis writing. It provides guidelines for organization and presentation of research in form of synopsis as well as organization of material within each section. Contents in each section tell what needs to be included in each section and how

1. Format your title page following your instructor's guidelines. In general, the title page of a research synopsis includes the title of the research project, your name, the degree and discipline for which you're writing the synopsis, and the names of your supervisor, department, institution, and university.

MS/M.Phil. Business Administration), at "Faculty Name" (e.g. Faculty of Management Studies), University of Central Punjab, hereby declare that this thesis titled, "Title of Thesis" is my own research work and has not been submitted, published, or printed elsewhere in Pakistan or abroad.

essen al that the bulk of thesis must be carefully controlled, e.g. around 75-100 pages for M.A / M.Sc. or M.Phil. / MS thesis and 150-200 for PhD disserta on in experimental, social and descrip ve science including appendices and tables (excluding illustra ons) may be a reasonable volume to incorporate and digest a

The thesis/synopsis/proposal shall be typed on one side of A4 size white paper of at least 80 gram. Method of production. The text must be typewritten in acceptable type face (readable) and the original typescript (or copy of equal quality) must normally be submitted to examination branch. Layout of script.

A research synopsis is a short outline of what your research thesis is and all the steps you propose to follow in order to achieve them. It gives you and you...

Key steps to write Synopsis for MPhil and PhD1. Introduction Title of Research Study background 2. Literature review Review Conceptual model Objectives Rese...

The synopsis for a thesis is basically the plan for a research project, typically done when pursuing a doctorate. It outlines the focus areas and key components of the research in order to obtain approval for the research. Here is a listing of the sections that typically are a part of the synopsis. Do check with your guide/supervisor for those ...

REVISED FORMAT OF SYNOPSIS (MS/MPhil & PhD) Given below is an outline for synopsis writing. It provides guidelines for MS/PHD students for presentation of research in form of synopsis as well as organization of ... Student can write abstract here (150-200 words) (Size 12, Time New Roman. Single line, center justified, one paragraph)

Overview of the structure. To help guide your reader, end your introduction with an outline of the structure of the thesis or dissertation to follow. Share a brief summary of each chapter, clearly showing how each contributes to your central aims. However, be careful to keep this overview concise: 1-2 sentences should be enough.

The synopsis is based on the information provided by the supervisor(s) and by secondary sources of information. In the final report you will present the results of your data collection and ...

Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates. Published on June 7, 2022 by Tegan George.Revised on November 21, 2023. A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical early steps in your writing process.It helps you to lay out and organize your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding the specifics of your dissertation topic and showcasing its relevance to ...