Confirmation Bias In Psychology: Definition & Examples

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

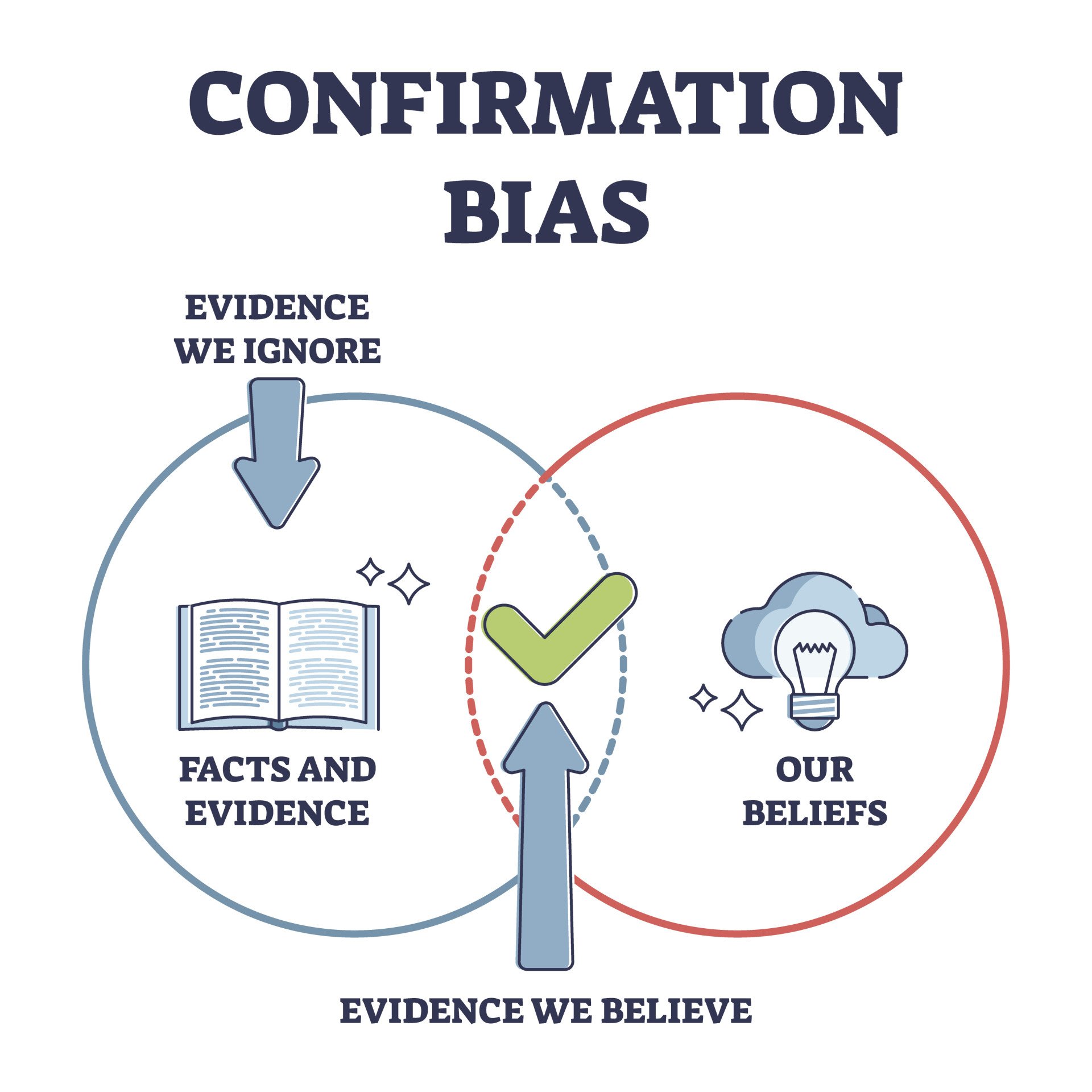

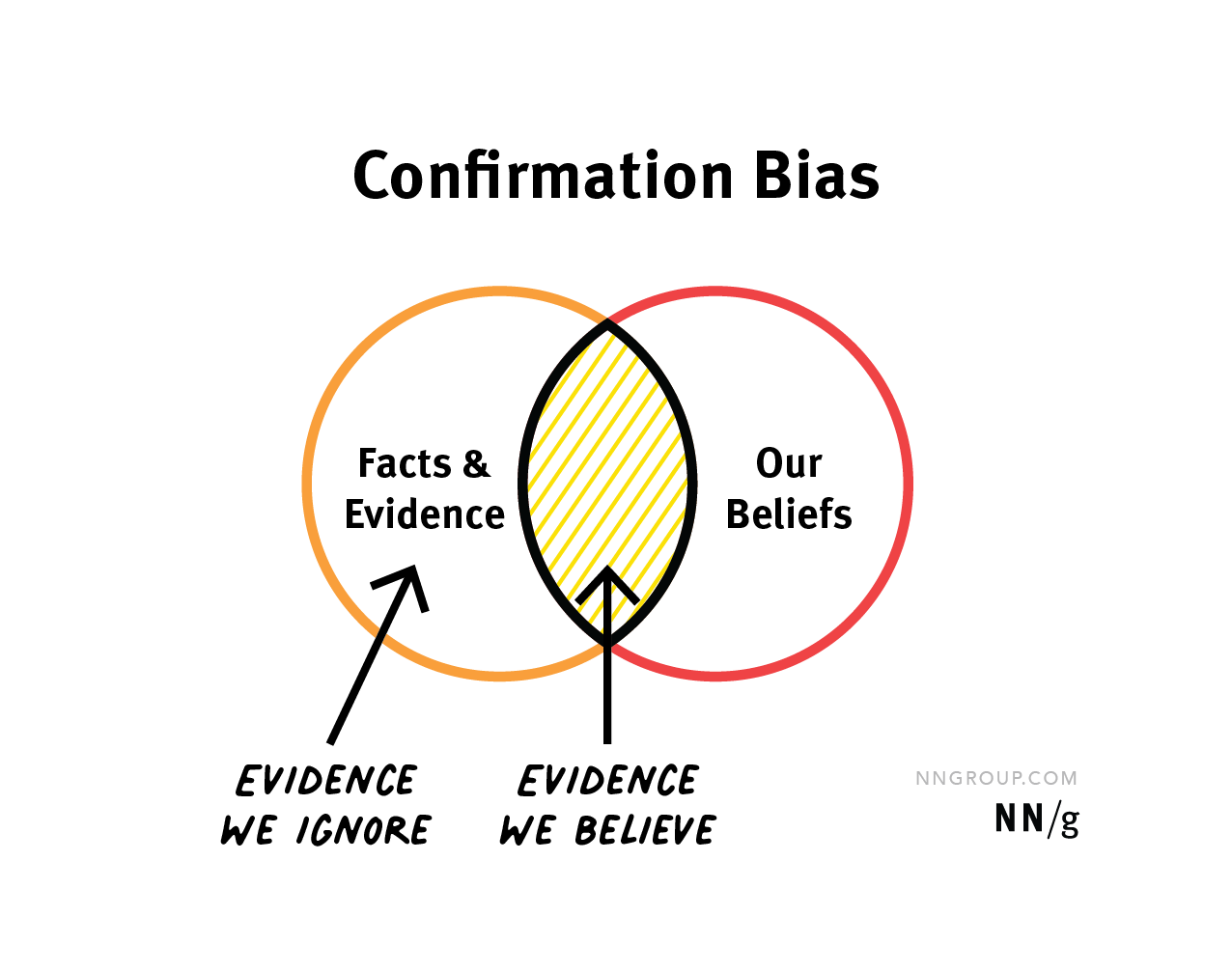

Confirmation Bias is the tendency to look for information that supports, rather than rejects, one’s preconceptions, typically by interpreting evidence to confirm existing beliefs while rejecting or ignoring any conflicting data (American Psychological Association).

One of the early demonstrations of confirmation bias appeared in an experiment by Peter Watson (1960) in which the subjects were to find the experimenter’s rule for sequencing numbers.

Its results showed that the subjects chose responses that supported their hypotheses while rejecting contradictory evidence, and even though their hypotheses were incorrect, they became confident in them quickly (Gray, 2010, p. 356).

Though such evidence of confirmation bias has appeared in psychological literature throughout history, the term ‘confirmation bias’ was first used in a 1977 paper detailing an experimental study on the topic (Mynatt, Doherty, & Tweney, 1977).

Biased Search for Information

This type of confirmation bias explains people’s search for evidence in a one-sided way to support their hypotheses or theories.

Experiments have shown that people provide tests/questions designed to yield “yes” if their favored hypothesis is true and ignore alternative hypotheses that are likely to give the same result.

This is also known as the congruence heuristic (Baron, 2000, p.162-64). Though the preference for affirmative questions itself may not be biased, there are experiments that have shown that congruence bias does exist.

For Example:

If you were to search “Are cats better than dogs?” in Google, all you would get are sites listing the reasons why cats are better.

However, if you were to search “Are dogs better than cats?” google will only provide you with sites that believe dogs are better than cats.

This shows that phrasing questions in a one-sided way (i.e., affirmative manner) will assist you in obtaining evidence consistent with your hypothesis.

Biased Interpretation

This type of bias explains that people interpret evidence concerning their existing beliefs by evaluating confirming evidence differently than evidence that challenges their preconceptions.

Various experiments have shown that people tend not to change their beliefs on complex issues even after being provided with research because of the way they interpret the evidence.

Additionally, people accept “confirming” evidence more easily and critically evaluate the “disconfirming” evidence (this is known as disconfirmation bias) (Taber & Lodge, 2006).

When provided with the same evidence, people’s interpretations could still be biased.

For example:

Biased interpretation is shown in an experiment conducted by Stanford University on the topic of capital punishment. It included participants who were in support of and others who were against capital punishment.

All subjects were provided with the same two studies.

After reading the detailed descriptions of the studies, participants still held their initial beliefs and supported their reasoning by providing “confirming” evidence from the studies and rejecting any contradictory evidence or considering it inferior to the “confirming” evidence (Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979).

Biased Memory

To confirm their current beliefs, people may remember/recall information selectively. Psychological theories vary in defining memory bias.

Some theories state that information confirming prior beliefs is stored in the memory while contradictory evidence is not (i.e., Schema theory). Some others claim that striking information is remembered best (i.e., humor effect).

Memory confirmation bias also serves a role in stereotype maintenance. Experiments have shown that the mental association between expectancy-confirming information and the group label strongly affects recall and recognition memory.

Though a certain stereotype about a social group might not be true for an individual, people tend to remember the stereotype-consistent information better than any disconfirming evidence (Fyock & Stangor, 1994).

In one experimental study, participants were asked to read a woman’s profile (detailing her extroverted and introverted skills) and assess her for either a job of a librarian or real-estate salesperson.

Those assessing her as a salesperson better recalled extroverted traits, while the other group recalled more examples of introversion (Snyder & Cantor, 1979).

These experiments, along with others, have offered an insight into selective memory and provided evidence for biased memory, proving that one searches for and better remembers confirming evidence.

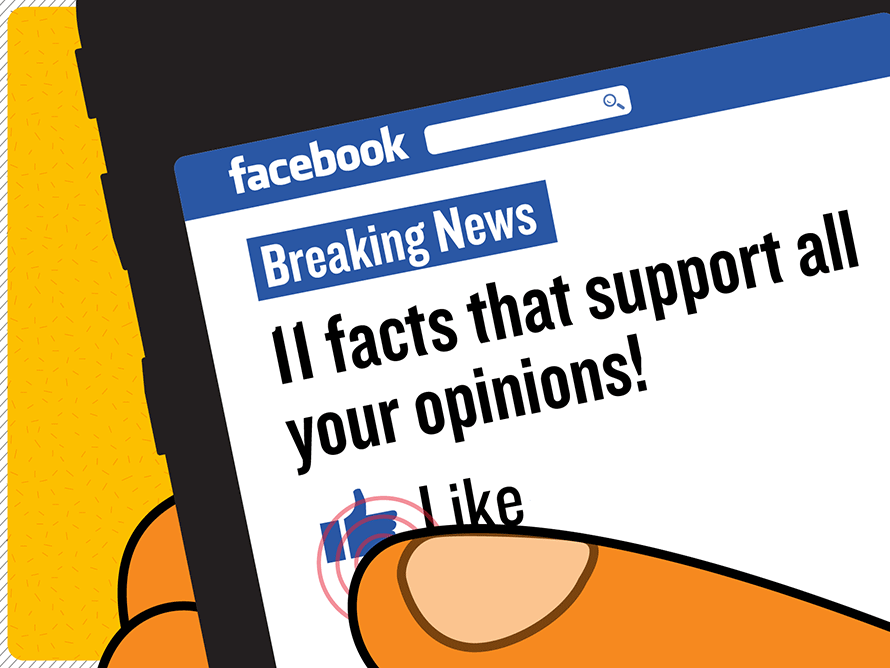

Social Media

Information we are presented on social media is not only reflective of what the users want to see but also of the designers’ beliefs and values. Today, people are exposed to an overwhelming number of news sources, each varying in their credibility.

To form conclusions, people tend to read the news that aligns with their perspectives. For instance, new channels provide information (even the same news) differently from each other on complex issues (i.e., racism, political parties, etc.), with some using sensational headlines/pictures and one-sided information.

Due to the biased coverage of topics, people only utilize certain channels/sites to obtain their information to make biased conclusions.

Religious Faith

People also tend to search for and interpret evidence with respect to their religious beliefs (if any).

For instance, on the topics of abortion and transgender rights, people whose religions are against such things will interpret this information differently than others and will look for evidence to validate what they believe.

Similarly, those who religiously reject the theory of evolution will either gather information disproving evolution or hold no official stance on the topic.

Also, irreligious people might perceive events that are considered “miracles” and “test of faiths” by religious people to be a reinforcement of their lack of faith in a religion.

when Does The Confirmation Bias Occur?

There are several explanations why humans possess confirmation bias, including this tendency being an efficient way to process information, protect self-esteem, and minimize cognitive dissonance.

Information Processing

Confirmation bias serves as an efficient way to process information because of the limitless information humans are exposed to.

To form an unbiased decision, one would have to critically evaluate every piece of information present, which is unfeasible. Therefore, people only tend to look for information desired to form their conclusions (Casad, 2019).

Protect Self-esteem

People are susceptible to confirmation bias to protect their self-esteem (to know that their beliefs are accurate).

To make themselves feel confident, they tend to look for information that supports their existing beliefs (Casad, 2019).

Minimize Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance also explains why confirmation bias is adaptive.

Cognitive dissonance is a mental conflict that occurs when a person holds two contradictory beliefs and causes psychological stress/unease in a person.

To minimize this dissonance, people adapt to confirmation bias by avoiding information that is contradictory to their views and seeking evidence confirming their beliefs.

Challenge avoidance and reinforcement seeking to affect people’s thoughts/reactions differently since exposure to disconfirming information results in negative emotions, something that is nonexistent when seeking reinforcing evidence (“The Confirmation Bias: Why People See What They Want to See”).

Implications

Confirmation bias consistently shapes the way we look for and interpret information that influences our decisions in this society, ranging from homes to global platforms. This bias prevents people from gathering information objectively.

During the election campaign, people tend to look for information confirming their perspectives on different candidates while ignoring any information contradictory to their views.

This subjective manner of obtaining information can lead to overconfidence in a candidate, and misinterpretation/overlooking of important information, thus influencing their voting decision and, eventually country’s leadership (Cherry, 2020).

Recruitment and Selection

Confirmation bias also affects employment diversity because preconceived ideas about different social groups can introduce discrimination (though it might be unconscious) and impact the recruitment process (Agarwal, 2018).

Existing beliefs of a certain group being more competent than the other is the reason why particular races and gender are represented the most in companies today. This bias can hamper the company’s attempt at diversifying its employees.

Mitigating Confirmation Bias

Change in intrapersonal thought:.

To avoid being susceptible to confirmation bias, start questioning your research methods, and sources used to obtain their information.

Expanding the types of sources used in searching for information could provide different aspects of a particular topic and offer levels of credibility.

- Read entire articles rather than forming conclusions based on the headlines and pictures. – Search for credible evidence presented in the article.

- Analyze if the statements being asserted are backed up by trustworthy evidence (tracking the source of evidence could prove its credibility). – Encourage yourself and others to gather information in a conscious manner.

Alternative hypothesis:

Confirmation bias occurs when people tend to look for information that confirms their beliefs/hypotheses, but this bias can be reduced by taking into alternative hypotheses and their consequences.

Considering the possibility of beliefs/hypotheses other than one’s own could help you gather information in a more dynamic manner (rather than a one-sided way).

Related Cognitive Biases

There are many cognitive biases that characterize as subtypes of confirmation bias. Following are two of the subtypes:

Backfire Effect

The backfire effect occurs when people’s preexisting beliefs strengthen when challenged by contradictory evidence (Silverman, 2011).

- Therefore, disproving a misconception can actually strengthen a person’s belief in that misconception.

One piece of disconfirming evidence does not change people’s views, but a constant flow of credible refutations could correct misinformation/misconceptions.

This effect is considered a subtype of confirmation bias because it explains people’s reactions to new information based on their preexisting hypotheses.

A study by Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler (two researchers on political misinformation) explored the effects of different types of statements on people’s beliefs.

While examining two statements, “I am not a Muslim, Obama says.” and “I am a Christian, Obama says,” they concluded that the latter statement is more persuasive and resulted in people’s change of beliefs, thus affirming statements are more effective at correcting incorrect views (Silverman, 2011).

Halo Effect

The halo effect occurs when people use impressions from a single trait to form conclusions about other unrelated attributes. It is heavily influenced by the first impression.

Research on this effect was pioneered by American psychologist Edward Thorndike who, in 1920, described ways officers rated their soldiers on different traits based on first impressions (Neugaard, 2019).

Experiments have shown that when positive attributes are presented first, a person is judged more favorably than when negative traits are shown first. This is a subtype of confirmation bias because it allows us to structure our thinking about other information using only initial evidence.

Learning Check

When does the confirmation bias occur.

- When an individual only researches information that is consistent with personal beliefs.

- When an individual only makes a decision after all perspectives have been evaluated.

- When an individual becomes more confident in one’s judgments after researching alternative perspectives.

- When an individual believes that the odds of an event occurring increase if the event hasn’t occurred recently.

The correct answer is A. Confirmation bias occurs when an individual only researches information consistent with personal beliefs. This bias leads people to favor information that confirms their preconceptions or hypotheses, regardless of whether the information is true.

Take-home Messages

- Confirmation bias is the tendency of people to favor information that confirms their existing beliefs or hypotheses.

- Confirmation bias happens when a person gives more weight to evidence that confirms their beliefs and undervalues evidence that could disprove it.

- People display this bias when they gather or recall information selectively or when they interpret it in a biased way.

- The effect is stronger for emotionally charged issues and for deeply entrenched beliefs.

Agarwal, P., Dr. (2018, October 19). Here Is How Bias Can Affect Recruitment In Your Organisation. https://www.forbes.com/sites/pragyaagarwaleurope/2018/10/19/how-can-bias-during-interviewsaffect-recruitment-in-your-organisation

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/confirmation-bias

Baron, J. (2000). Thinking and Deciding (Third ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Casad, B. (2019, October 09). Confirmation bias . https://www.britannica.com/science/confirmation-bias

Cherry, K. (2020, February 19). Why Do We Favor Information That Confirms Our Existing Beliefs? https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-confirmation-bias-2795024

Fyock, J., & Stangor, C. (1994). The role of memory biases in stereotype maintenance. The British journal of social psychology, 33 (3), 331–343.

Gray, P. O. (2010). Psychology . New York: Worth Publishers.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 (11), 2098–2109.

Mynatt, C. R., Doherty, M. E., & Tweney, R. D. (1977). Confirmation bias in a simulated research environment: An experimental study of scientific inference. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 29 (1), 85-95.

Neugaard, B. (2019, October 09). Halo effect. https://www.britannica.com/science/halo-effect

Silverman, C. (2011, June 17). The Backfire Effect . https://archives.cjr.org/behind_the_news/the_backfire_effect.php

Snyder, M., & Cantor, N. (1979). Testing hypotheses about other people: The use of historical knowledge. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 15 (4), 330–342.

Further Information

- What Is Confirmation Bias and When Do People Actually Have It?

- Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises

- The importance of making assumptions: why confirmation is not necessarily a bias

- Decision Making Is Caused By Information Processing And Emotion: A Synthesis Of Two Approaches To Explain The Phenomenon Of Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias occurs when individuals selectively collect, interpret, or remember information that confirms their existing beliefs or ideas, while ignoring or discounting evidence that contradicts these beliefs.

This bias can happen unconsciously and can influence decision-making and reasoning in various contexts, such as research, politics, or everyday decision-making.

What is confirmation bias in psychology?

Confirmation bias in psychology is the tendency to favor information that confirms existing beliefs or values. People exhibiting this bias are likely to seek out, interpret, remember, and give more weight to evidence that supports their views, while ignoring, dismissing, or undervaluing the relevance of evidence that contradicts them.

This can lead to faulty decision-making because one-sided information doesn’t provide a full picture.

Related Articles

Cognitive Psychology

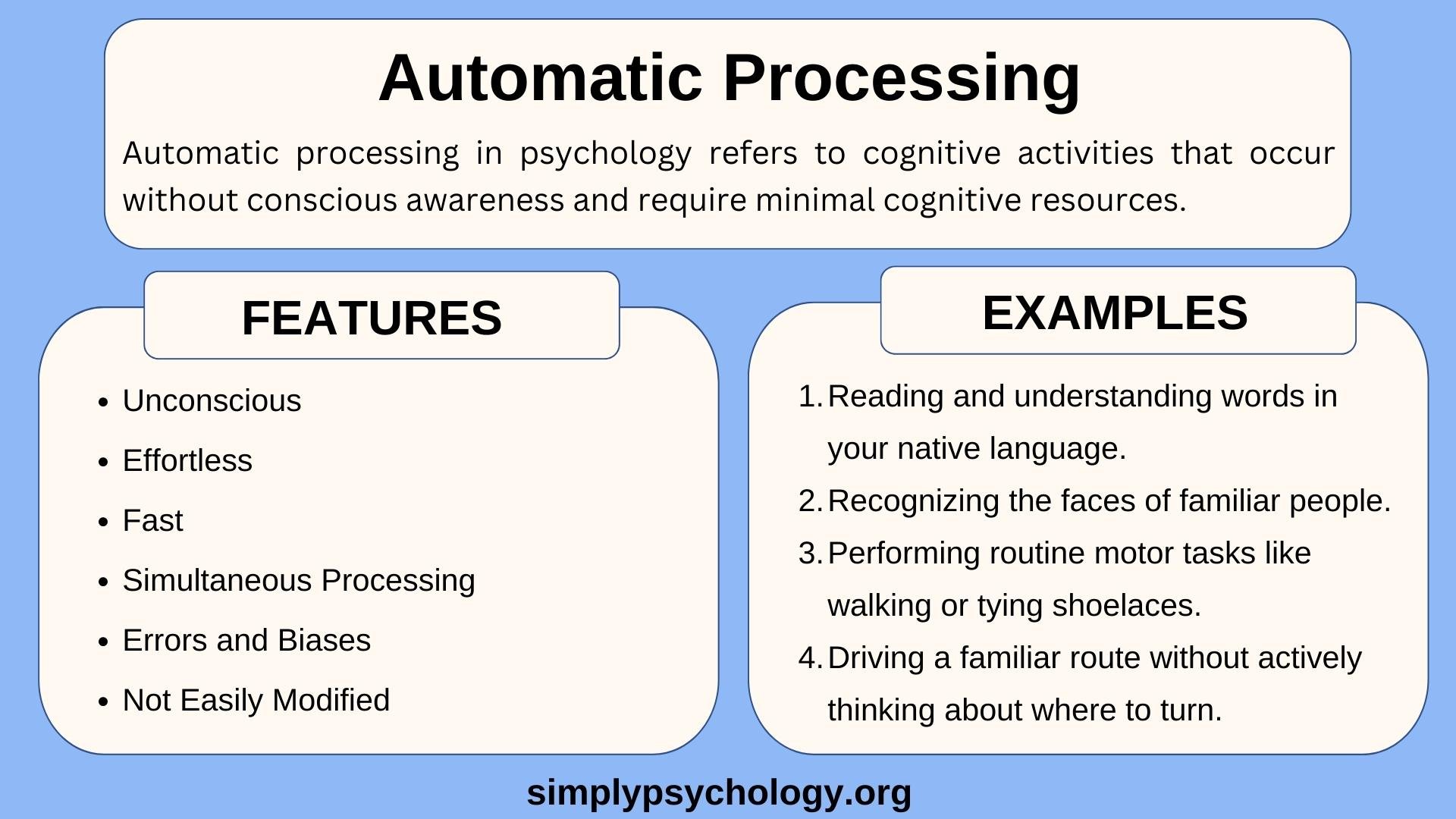

Automatic Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

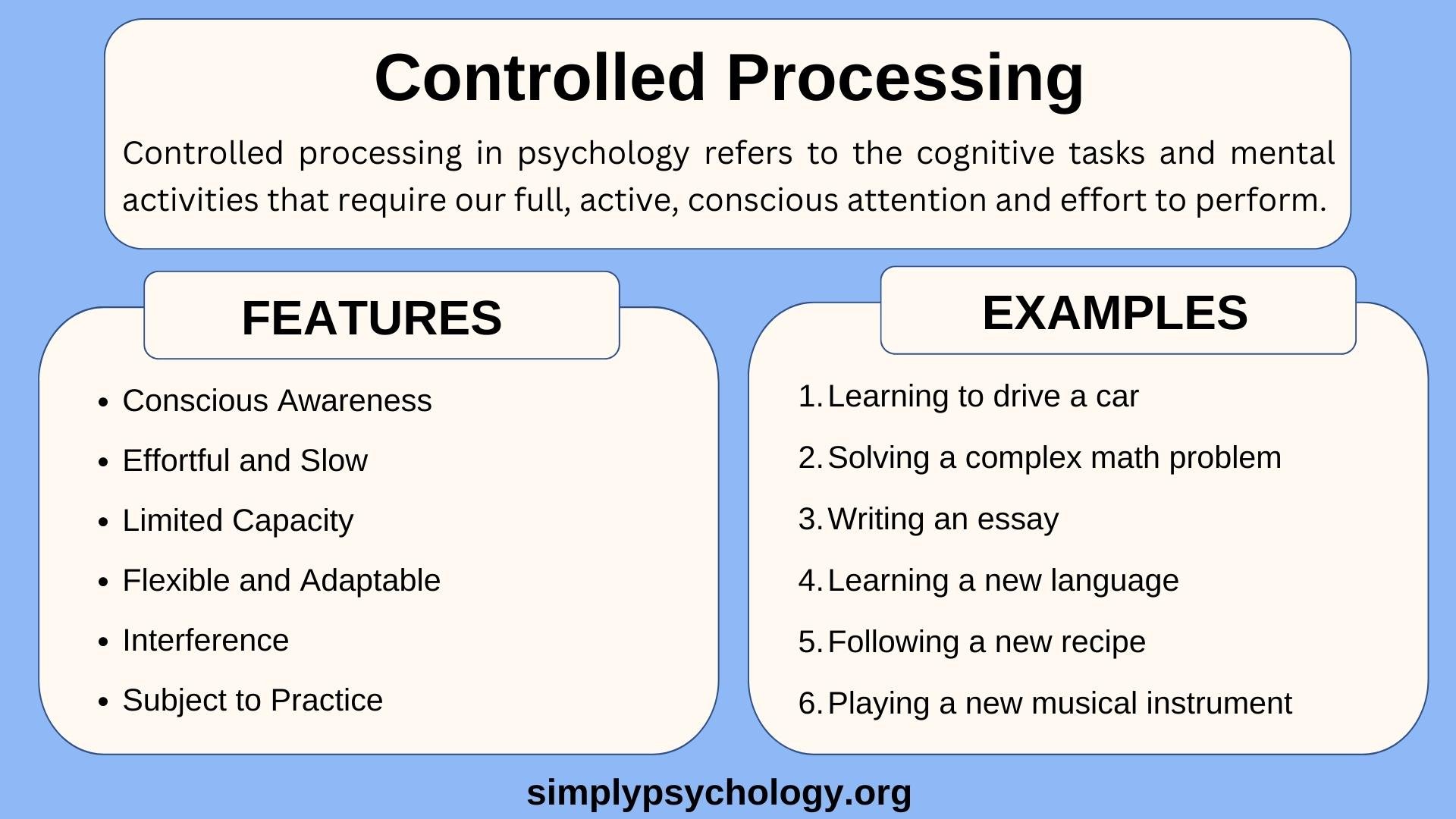

Controlled Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

How Ego Depletion Can Drain Your Willpower

What is the Default Mode Network?

Theories of Selective Attention in Psychology

Availability Heuristic and Decision Making

Search This Blog

Buyer behaviour.

Deciphering Buying Behaviour & Consumer Lifestyles for Marketing Decisions.

Prior Hypothesis Bias

Popular posts, common man's cars, world peace, yes; info. to the world, no.

Effectiviology

The Confirmation Bias: Why People See What They Want to See

The confirmation bias is a cognitive bias that causes people to search for, favor, interpret, and recall information in a way that confirms their preexisting beliefs. For example, if someone is presented with a lot of information on a certain topic, the confirmation bias can cause them to only remember the bits of information that confirm what they already thought.

The confirmation bias influences people’s judgment and decision-making in many areas of life, so it’s important to understand it. As such, in the following article you will first learn more about the confirmation bias, and then see how you can reduce its influence, both in other people’s thought process as well as in your own.

How the confirmation bias affects people

The confirmation bias promotes various problematic patterns of thinking , such as people’s tendency to ignore information that contradicts their beliefs . It does so through several types of biased cognitive processes:

- Biased search for information. This means that the confirmation bias causes people to search for information that confirms their preexisting beliefs, and to avoid information that contradicts them.

- Biased favoring of information. This means that the confirmation bias causes people to give more weight to information that supports their beliefs, and less weight to information that contradicts them.

- Biased interpretation of information. This means that the confirmation bias causes people to interpret information in a way that confirms their beliefs, even if the information could be interpreted in a way that contradicts them.

- Biased recall of information. This means that the confirmation bias causes people to remember information that supports their beliefs and to forget information that contradicts them, or to remember supporting information as having been more supporting than it really was, or to incorrectly remember contradictory information as having supported their beliefs.

Note : one closely related phenomenon is cherry picking . It involves focusing only on evidence that supports one’s stance, while ignoring evidence that contradicts it. People often engage in cherry picking due to the confirmation bias, though it’s possible to engage in cherry picking even if a person is fully aware of what they’re doing, and is unaffected by the bias.

Examples of the confirmation bias

One example of the confirmation bias is someone who searches online to supposedly check whether a belief that they have is correct, but ignores or dismisses all the sources that state that it’s wrong. Similarly, another example of the confirmation bias is someone who forms an initial impression of a person, and then interprets everything that this person does in a way that confirms this initial impression.

Furthermore, other examples of the confirmation appear in various domains. For instance, the confirmation bias can affect:

- How people view political information. For example, people generally prefer to spend more time looking at information that supports their political stance and less time looking at information that contradicts it.

- How people assess pseudoscientific beliefs. For example, people who believe in pseudoscientific theories tend to ignore information that disproves those theories .

- How people invest money. For example, investors give more weight to information that confirms their preexisting beliefs regarding the value of certain stocks.

- How scientists conduct research. For example, scientists often display the confirmation bias when they selectively analyze and interpret data in a way that confirms their preferred hypothesis.

- How medical professionals diagnose patients. For example, doctors often search for new information in a selective manner that will allow them to confirm their initial diagnosis of a patient, while ignoring signs that this diagnosis could be wrong.

In addition, an example of how the confirmation bias can influence people appears in the following quote, which references the prevalent misinterpretation of evidence during witch trials in the 17th century:

“When men wish to construct or support a theory, how they torture facts into their service!” — From “ Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds “

Similarly, another example of how people display the confirmation bias is the following:

“… If the new information is consonant with our beliefs, we think it is well founded and useful: ‘Just what I always said!’ But if the new information is dissonant, then we consider it biased or foolish: ‘What a dumb argument!’ So powerful is the need for consonance that when people are forced to look at disconfirming evidence, they will find a way to criticize, distort, or dismiss it so that they can maintain or even strengthen their existing belief.” — From “ Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts “

Overall, examples of the confirmation bias appear in various domains. These examples illustrate the various different ways in which it can affect people, and show that this bias is highly prevalent, including among trained professionals who are often assumed to assess information in a purely rational manner.

Psychology and causes of the confirmation bias

The confirmation bias can be attributed to two main cognitive mechanisms:

- Challenge avoidance , which is the desire to avoid finding out that you’re wrong.

- Reinforcement seeking , which is the desire to find out that you’re right.

These forms of motivated reasoning can be attributed to people’s underlying desire to minimize their cognitive dissonance , which is psychological distress that occurs when people hold two or more contradictory beliefs simultaneously. Challenge avoidance can reduce dissonance by reducing engagement with information that contradicts preexisting beliefs. Conversely, reinforcement seeking can reduce dissonance by increasing engagement with information that affirms people’s sense of correctness , including if they encounter contradictory information later.

Furthermore, the confirmation bias also occurs due to flaws in the way we test hypotheses. For example, when people try to find an explanation for a certain phenomenon, they tend to focus on only one hypothesis at a time, and disregard alternative hypotheses, even in cases where they’re not emotionally incentivized to confirm their initial hypothesis. This can cause people to simply try and prove that their initial hypothesis is true, instead of trying to actually check whether it’s true or not, which causes them to ignore the possibility that the information that they encounter could disprove this initial hypothesis, or support alternative hypotheses.

An example of this is a doctor who forms an initial diagnosis of a patient, and who then focuses solely on trying to prove that this diagnosis is right, instead of trying to actively determine whether alternative diagnoses could make more sense.

This explains why people can experience unmotivated confirmation bias in situations where they have no emotional reason to favor a specific hypothesis over others. This is contrasted with a motivated confirmation bias, which occurs when the person displaying the bias is motivated by some emotional consideration.

Finally, the confirmation bias can also be attributed to a number of additional causes. For example, in the case of the motivated confirmation bias, an additional reason why people experience the bias is that the brain sometimes suppresses neural activity in areas associated with emotional regulation and emotionally neutral reasoning. This causes people to process information based on how their emotions guide them to, rather than based on how their logic would guide them.

Overall, people experience the confirmation bias primarily because they want to minimize psychological distress, and specifically due to challenge avoidance , which is the desire to avoid finding out that they’re wrong, and reinforcement seeking , which is the desire to find out that they’re right. Furthermore, people can also experience the confirmation due to other causes, such as the flawed way they test hypotheses, as in the case where people fixate on confirming a single hypothesis while ignoring alternatives.

Note : Some of the behaviors that people engage in due to the confirmation bias can be viewed as a form of selective exposure . This involves people choosing to engage only with information that supports their preexisting beliefs and decisions, while ignoring information that contradicts them.

How to reduce the confirmation bias

Reducing other people’s confirmation bias.

There are various things that you can do to reduce the influence that the confirmation bias has on people. These methods generally revolve around trying to counteract the cognitive mechanisms that promote the confirmation bias in the first place .

As such, these methods generally involve trying to get people to overcome their tendency to focus on and prefer confirmatory information, or their tendency to avoid and reject challenging information, while also encouraging them to conduct a valid reasoning process.

Specifically, the following are some of the most notable techniques that you can use to reduce the confirmation bias in people:

- Explain what the confirmation bias is, why we experience it, how it affects us, and why it can be a problem, potentially using relevant examples. Understanding this phenomenon better can motivate people to avoid it, and can help them deal with it more effectively, by helping them recognize when and how it affects them. Note that in some cases, it may be beneficial to point out the exact way in which a person is displaying the confirmation bias.

- Make it so that the goal is to find the right answer, rather than defend an existing belief. For example, consider a situation where you’re discussing a controversial topic with someone, and you know for certain that they’re wrong. If you argue hard against them, that might cause them to get defensive and feel that they must stick by their initial stance regardless of whatever evidence you show them. Conversely, if you state that you’re just trying to figure out what the right answer is, and discuss the topic with them in a friendly manner, that can make them more open to considering the challenging evidence that you present. In this case, your goal is to frame your debate as a journey that you go on together in search of the truth, rather than a battle where you fight each other to prove the other wrong. The key here is that, when it comes to a joint journey, both of you can be “winners”, while in the case of a battle, only one of you can, and the other person will often experience the confirmation bias to avoid feeling that they were the “loser”.

- Minimize the unpleasantness and issues associated with finding out that they’re wrong. In general, the more unpleasant and problematic being wrong is, the more a person will use the confirmation bias to stick by their initial stance. There are various ways in which you can make the experience of being wrong less unpleasant or problematic, such as by emphasizing the value of learning new things, and by avoiding mocking people for having held incorrect beliefs.

- Encourage people to avoid letting their emotional response dictate their actions. Specifically, explain that while it’s natural to want to avoid challenges and seek reinforcement, letting these feelings dictate how you process information and make decisions is problematic. This means, for example, that if you feel that you want to avoid a certain piece of information, because it might show that you’re wrong, then you should realize this, but choose to see that information anyway.

- Encourage people to give information sufficient consideration. When it comes to avoiding the confirmation bias, it often helps to engage with information in a deep and meaningful way, since shallow engagement can lead people to rely on biased intuitions, rather than on proper analytical reasoning. There are various things that people can do to ensure that they give information sufficient consideration , such as spending a substantial amount of time considering it, or interacting with it in an environment that has no distractions.

- Encourage people to avoid forming a hypothesis too early. Once people have a specific hypothesis in mind, they often try and confirm it , instead of trying to formulate and test other possible hypotheses. As such, it can often help to encourage people to process as much information as possible before forming their initial hypothesis.

- Ask people to explain their reasoning. For example, you can ask them to clearly state what their stance is, and what evidence has caused them to support that stance. This can help people identify potential issues in their reasoning, such as that their stance is unsupported.

- Ask people to think about various reasons why their preferred hypothesis might be wrong. This can help them test their preferred hypothesis in ways that they might not otherwise, and can make them more likely to accept and internalize challenging information .

- Ask people to think about alternative hypotheses, and why those hypotheses might be right. Similarly to asking people to think about reasons why their preferred hypothesis might be wrong, this can encourage people to engage in a proper reasoning process, which they might not do otherwise. Note that, when doing this, it is generally better to focus on a small number of alternative hypotheses , rather than a large number of them.

Different techniques will be more effective for reducing the confirmation bias in different situations, and it is generally most effective to use a combination of techniques, while taking into account relevant situational and personal factors.

Furthermore, in addition to the above techniques, which are aimed at reducing the confirmation bias in particular, there are additional debiasing techniques that you can use to help people overcome their confirmation bias. This includes, for example, getting people to slow down their reasoning process, creating favorable conditions for optimal decision making, and standardizing the decision-making process.

Overall, to reduce the confirmation bias in others, you can use various techniques that revolve around trying to counteract the cognitive mechanisms that promote the confirmation bias in the first place. This includes, for example, making people aware of this bias, making discussions be about finding the right answer instead of defending an existing belief, minimizing the unpleasantness associated with being wrong, encouraging people to give information sufficient consideration, and asking people to think about why their preferred hypothesis might be wrong or why competing hypotheses could be right.

Reducing your own confirmation bias

To mitigate the confirmation bias in yourself, you can use similar techniques to those that you would use to mitigate it in others. Specifically, you can do the following:

- Identify when and how you’re likely to experience the bias.

- Maintain awareness of the bias in relevant situations, and even actively ask yourself whether you’re experiencing it.

- Figure out what kind of negative outcomes the bias can cause for you.

- Focus on trying to find the right answer, rather than on proving that your initial belief was right.

- Avoid feeling bad if you find out that you’re wrong; for example, try to focus on having learned something new that you can use in the future.

- Don’t let your emotions dictate how you process information, particularly when it comes to seeking confirmation or avoiding challenges to your beliefs.

- Dedicate sufficient time and mental effort when processing relevant information.

- Avoid forming a hypothesis too early, before you’d had a chance to analyze sufficient information.

- Clearly outline your reasoning, for example by identifying your stance and the evidence that you’re basing it on.

- Think of reasons why your preferred hypothesis might be wrong.

- Come up with alternative hypotheses, as well as reasons why those hypotheses might be right.

An added benefit of many of these techniques is that they can help you understand opposing views better, which is important when it comes to explaining your own stance and communicating with others on the topic.

In addition, you can also use general debiasing techniques , such as standardizing your decision-making process and creating favorable conditions for assessing information.

Furthermore, keep in mind that, as is the case with reducing the confirmation bias in others, different techniques will be more effective than others, both in general and in particular circumstances. You should take this into account, and try to find the approach that works best for you in any given situation.

Finally, note that in some ways, debiasing yourself can be easier than debiasing others, since other people are often not as open to your debiasing attempts as you yourself are. At the same time, however, debiasing yourself is also more difficult in some ways, since we often struggle to notice our own blind spots, and to identify areas where we are affected by cognitive biases in general, and the confirmation bias in particular.

Overall, to reduce the confirmation bias in yourself, you can use similar techniques to those that you would use to reduce it in others. This includes, for example, maintaining awareness of this bias, focusing on trying to find the right answer rather than proving that you were right, dedicating sufficient time and effort to analyzing information, clearly outlining your reasoning, thinking of reasons why your preferred hypothesis might be wrong, and coming up with alternative hypotheses.

Additional information

Related cognitive biases.

There are many cognitive biases that are closely associated with the confirmation bias, either because they involved a similar pattern or reasoning, or because they occur, at least partly, due to underlying confirmation bias.

For example, there is the backfire effect , which is a cognitive bias that causes people who encounter evidence that challenges their beliefs to reject that evidence, and to strengthen their support of their original stance. This bias can, for instance, cause people to increase their support for a political candidate after they encounter negative information about that candidate, or to strengthen their belief in a scientific misconception after they encounter evidence that highlights the issues with that misconception. The backfire effect is closely associated with the confirmation bias, since it involves the rejection of challenging evidence, with the goal of confirming one’s original beliefs.

Another example of a cognitive bias that is closely related to the confirmation bias is the halo effect , which is a cognitive bias that causes people’s impression of someone or something in one domain to influence their impression of them in other domains. This bias can, for instance, cause people to assume that if someone is physically attractive, then they must also have an interesting personality , or it can cause people to give higher ratings to an essay if they believe that it was written by an attractive author . The halo effect is closely associated with the confirmation bias, since it can be attributed in some cases to people’s tendency to confirm their initial impression of someone, by forming later impressions of them in a biased manner.

The origin and history of the confirmation bias

The term ‘confirmation bias’ was first used in a 1977 paper titled “ Confirmation bias in a simulated research environment: An experimental study of scientific inference “, published by Clifford R. Mynatt, Michael E. Doherty, and Ryan D. Tweney in the Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (Volume 29, Issue 1, pp. 85-95). However, as the authors themselves note, evidence of the confirmation bias can be found earlier in the psychological literature.

Specifically, the following passage is the abstract of the paper that coined the term. It outlines the work presented in the paper, and also notes the existence of prior work on the topic:

“Numerous authors (e.g., Popper, 1959 ) argue that scientists should try to falsify rather than confirm theories. However, recent empirical work (Wason and Johnson-Laird, 1972 ) suggests the existence of a confirmation bias, at least on abstract problems. Using a more realistic, computer controlled environment modeled after a real research setting, subjects in this study first formulated hypotheses about the laws governing events occurring in the environment. They then chose between pairs of environments in which they could: (1) make observations which would probably confirm these hypotheses, or (2) test alternative hypotheses. Strong evidence for a confirmation bias involving failure to choose environments allowing tests of alternative hypotheses was found. However, when subjects did obtain explicit falsifying information, they used this information to reject incorrect hypotheses.”

In addition, a number of other past studies are discussed in the paper :

“Examples abound of scientists clinging to pet theories and refusing to seek alternatives in the face of large amounts of contradictory data (see Kuhn, 1970 ). Objective evidence, however, is scant. Wason ( 1968a ) has conducted several experiments on inferential reasoning in which subjects were given conditional rules of the form ‘If P then Q’, where P was a statement about one side of a stimulus card and Q a statement about the other side. Four stimulus cards, corresponding to P, not-P, Q, and not-Q were provided. The subjects’ task was to indicate those cards—and only those cards—which had to be turned over in order to determine if the rule was true or false. Most subjects chose only P, or P and Q. The only cards which can falsify the rule, however, are P and not-Q. Since the not-Q card is almost never selected, the results indicate a strong tendency to seek confirmatory rather than disconfirmatory evidence. This bias for selecting confirmatory evidence has proved remarkably difficult to eradicate (see Wason and Johnson-Laird, 1972 , pp. 171-201). In another set of experiments, Wason ( 1960 , 1968b , 1971 ) also found evidence of failure to consider alternative hypotheses. Subjects were given the task of recovering an experimenter defined rule for generating numerical sequences. The correct rule was a very general one and, consequently, many incorrect specific rules could generate sequences which were compatible with the correct rule. Most subjects produced a few sequences based upon a single, specific rule, received positive feedback, and announced mistakenly that they had discovered the correct rule. With some notable exceptions, what subjects did not do was to generate and eliminate alternative rules in a systematic fashion. Somewhat similar results have been reported by Miller ( 1967 ). Finally, Mitroff ( 1974 ), in a large-scale non-experimental study of NASA scientists, reports that a strong confirmation bias existed among many members of this group. He cites numerous examples of these scientists’ verbalizations of their own and other scientists’ obduracy in the face of data as evidence for this conclusion.”

Summary and conclusions

- The confirmation bias is a cognitive bias that causes people to search for, favor, interpret, and recall information in a way that confirms their preexisting beliefs.

- The confirmation bias affects people in every area of life; for example, it can cause people to disregard negative information about a political candidate that they support, or to only pay attention to news articles that support what they already think.

- People experience the confirmation bias due to various reasons, including challenge avoidance (the desire to avoid finding out that they’re wrong), reinforcement seeking (the desire to find out that they’re right), and flawed testing of hypotheses (e.g., fixating on a single explanation from the start).

- To reduce the confirmation bias in yourself and in others, you can use various techniques that revolve around trying to counteract the cognitive mechanisms that promote the confirmation bias in the first place.

- Relevant debiasing techniques you can use include maintaining awareness of this bias, focusing on trying to find the right answer rather than being proven right, dedicating sufficient time and effort to analyzing relevant information, clearly outlining the reasoning process, thinking of reasons why a preferred hypothesis might be wrong, and coming up with alternative hypotheses and reasons why those hypotheses might be right.

Other articles you may find interesting:

- The Backfire Effect: Why Facts Don't Always Change Minds

- Cherry Picking: When People Ignore Evidence that They Dislike

- Belief Bias: When People Rely on Beliefs Rather Than Logic

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Confirmation Bias?

Cherrypicking the Facts to Support an Existing Belief

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Verywell / Daniel Fishel

- Tips for Overcoming It

Confirmation bias is a type of cognitive bias that favors information that confirms your previously existing beliefs or biases .

For example, imagine that Mary believes left-handed people are more creative than right-handed people. Whenever Mary encounters a left-handed, creative person, she will place greater importance on this "evidence" because it supports what she already believes. Mary might even seek proof that further backs up this belief while discounting examples that don't support the idea.

Confirmation biases affect not only how we gather information but also how we interpret and recall it. For example, people who support or oppose a particular issue will not only seek information to support it, but they will also interpret news stories in a way that upholds their existing ideas. They will also remember details in a way that reinforces these attitudes .

History of Confirmation Bias

The idea behind the confirmation bias has been observed by philosophers and writers since ancient times. In the 1960s, cognitive psychologist Peter Wason conducted several experiments known as Wason's rule discovery task. He demonstrated that people tend to seek information that confirms their existing beliefs.

Signs of Confirmation Bias

When it comes to confirmation bias, there are often signs that a person is inadvertently or consciously falling victim to it. Unfortunately, it can also be very subtle and difficult to spot. Some of these signs that might help you identify when you or someone else is experiencing this bias include:

- Only seeking out information that confirms your beliefs and ignoring or discredit information that doesn't support them.

- Looking for evidence that confirms what you already think is true, rather than considering all of the evidence available.

- Relying on stereotypes or personal biases when assessing information.

- Selectively remembering information that supports your views while forgetting or discounting information that doesn't.

- Having a strong emotional reaction to information (positive or negative) that confirms your beliefs, while remaining relatively unaffected by information that doesn't.

Types of Confirmation Bias

There are a few different types of confirmation bias that can occur. Some of the most common include the following:

- Biased attention : This is when we selectively focus on information that confirms our views while ignoring or discounting data that doesn't.

- Biased interpretation : This is when we consciously interpret information in a way that confirms our beliefs.

- Biased memory : This is when we selectively remember information that supports our views while forgetting or discounting information that doesn't.

Examples of the Confirmation Bias

It can be helpful to consider a few examples of how confirmation bias works in everyday life to get a better idea of the effects and impact it may have.

Interpretations of Current Issues

One of the most common examples of confirmation bias is how we seek out or interpret news stories. We are more likely to believe a story if it confirms our pre-existing views, even if the evidence presented is shaky or inconclusive. For example, if we support a particular political candidate, we are more likely to believe news stories that paint them in a positive light while discounting or ignoring those that are critical.

Consider the debate over gun control:

- Let's say Sally is in support of gun control. She seeks out news stories and opinion pieces that reaffirm the need for limitations on gun ownership. When she hears stories about shootings in the media, she interprets them in a way that supports her existing beliefs.

- Henry, on the other hand, is adamantly opposed to gun control. He seeks out news sources that are aligned with his position. When he comes across news stories about shootings, he interprets them in a way that supports his current point of view.

These two people have very different opinions on the same subject, and their interpretations are based on their beliefs. Even if they read the same story, their bias shapes how they perceive the details, further confirming their beliefs.

Personal Relationships

Another example of confirmation bias can be seen in the way we choose friends and partners. We are more likely to be attracted to and befriend people who share our same beliefs and values, and less likely to associate with those who don't. This can lead to an echo chamber effect, where we only ever hear information that confirms our views and never have our opinions challenged.

Decision-Making

The confirmation bias can often lead to bad decision-making . For example, if we are convinced that a particular investment is good, we may ignore warning signs that it might not be. Or, if we are set on getting a job with a particular company, we may not consider other opportunities that may be better suited for us.

Impact of the Conformation Bias

The confirmation bias happens due to the natural way the brain works, so eliminating it is impossible. While it is often discussed as a negative tendency that impairs logic and decisions, it isn't always bad. The confirmation bias can significantly impact our lives, both positively and negatively. On the positive side, it can help us stay confident in our beliefs and values and give us a sense of certainty and security.

Unfortunately, this type of bias can prevent us from looking at situations objectively. It can also influence our decisions and lead to poor or faulty choices.

During an election season, for example, people tend to seek positive information that paints their favored candidates in a good light. They will also look for information that casts the opposing candidate in a negative light.

By not seeking objective facts, interpreting information in a way that only supports their existing beliefs, and remembering details that uphold these beliefs, they often miss important information. These details and facts might have influenced their decision on which candidate to support.

How to Overcome the Confirmation Bias

There are a few different ways that we can try to overcome confirmation bias:

- Be aware of the signs that you may be falling victim to it. This includes being aware of your personal biases and how they might be influencing your decision-making.

- Consider all the evidence available, rather than just the evidence confirming your views.

- Seek out different perspectives, especially from those who hold opposing views.

- Be willing to change your mind in light of new evidence, even if it means updating or even changing your current beliefs.

Confirmation Bias: The Takeaway

Unfortunately, all humans are prone to confirmation bias. Even if you believe you are very open-minded and consider the facts before coming to conclusions, some bias likely shapes your opinion. Combating this natural tendency is difficult.

However, knowing about confirmation bias and accepting its existence can help you recognize it. Be curious about opposing views and listen to what others have to say and why. This can help you see issues and beliefs from other perspectives.

American Psychological Association. Confirmation bias . APA Dictionary of Psychology.

Wason PC. On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task . Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology . 1960;12(3):129-140. doi:10.1080/17470216008416717

Satya-Murti S, Lockhart J. Recognizing and reducing cognitive bias in clinical and forensic neurology . Neurol Clin Pract . 2015 Oct;5(5):389-396. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000181

Allahverdyan AE, Galstyan A. Opinion dynamics with confirmation bias . PLoS One . 2014;9(7):e99557. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099557

Frost P, Casey B, Griffin K, Raymundo L, Farrell C, Carrigan R. The influence of confirmation bias on memory and source monitoring. J Gen Psychol . 2015;142(4):238-52. doi:10.1080/00221309.2015.1084987

Suzuki M, Yamamoto Y. Characterizing the influence of confirmation bias on web search behavior . Front Psychol . 2021;12:771948. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.771948

Poletiek FH. Hypothesis-Testing Behavior . Psychology Press, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

What Is Confirmation Bias?

People are prone to believe what they want to believe..

Posted April 23, 2015 | Reviewed by Lybi Ma

- When people would like a certain concept to be true, they believe it to be true. This is confirmation bias.

- Confirmation bias can be found in anxious individuals, who view the world as dangerous.

- Wishful thinking, or false optimism, can lead to confirmation bias.

- Overcoming confirmation bias begins with setting one's hypothesis while looking for how to prove it is wrong.

Imagine that you have tried to reach a friend with whom you have an ambivalent relationship by phone or email, leaving messages, yet receiving no call in return. In a situation like this, it is easy to jump to conclusions in an intuitive manner that your friend wants to avoid you. The danger, of course, is that you leave this belief unchecked and start to act as though it were true.

Confirmation bias occurs from the direct influence of desire on beliefs. When people would like a certain idea or concept to be true, they end up believing it to be true. They are motivated by wishful thinking. This error leads the individual to stop gathering information when the evidence gathered so far confirms the views or prejudices one would like to be true.

Once we have formed a view, we embrace information that confirms that view while ignoring, or rejecting, information that casts doubt on it. Confirmation bias suggests that we don’t perceive circumstances objectively. We pick out those bits of data that make us feel good because they confirm our prejudices. Thus, we may become prisoners of our assumptions. For example, some people will have a very strong inclination to dismiss any claims that marijuana may cause harm as nothing more than old-fashioned reefer madness. Some social conservatives will downplay any evidence that marijuana does not cause harm.

Confirmation bias, anxiety, and self-deception

Confirmation bias can also be found in anxious individuals, who view the world as dangerous. For example, a person with low self-esteem is highly sensitive to being ignored by other people, and they constantly monitor for signs that people might not like them. Thus, if you are worried that someone is annoyed with you, you are biased toward all the negative information about how that person acts toward you. You interpret neutral behavior as indicative of something negative.

Wishful thinking is a form of self-deception , such as false optimism . For example, we often deceive ourselves, such as stating: just this one; it’s not that fattening; I’ll stop smoking tomorrow. Or when someone is “under the influence” he feels confident that he can drive safely even after three or more drinks.

Self-deception can be like a drug, numbing you from harsh reality or turning a blind eye to the tough matter of gathering evidence and thinking. As Voltaire commented long ago, “Illusion is the first of all pleasure.” In some cases, self-deception is good for us. For example, when dealing with certain illnesses, positive thinking may actually be beneficial for diseases such as cancer, but not diabetes or ulcers. There is limited evidence that believing that you will recover helps reduce your level of stress hormones , giving the immune system and modern medicine a better chance to do their work.

In sum, people are prone to believe what they want to believe. Seeking to confirm our beliefs comes naturally, while it feels strong and counterintuitive to look for evidence that contradicts our beliefs. This explains why opinions survive and spread. Disconfirming instances are far more powerful in establishing the truth. Disconfirmation would require looking for evidence to disprove it.

How to minimize confirmation bias

The take-home lesson here is to set your hypothesis and look for instances to prove that you are wrong. This is perhaps a true definition of self-confidence : the ability to look at the world without the need to look for instances that please your ego.

For group decision-making , it is crucial to obtain information from each member in a way that they are independent. For example, as part of a police procedure to derive the most reliable information from multiple witnesses to a crime , witnesses are not allowed to discuss it prior to giving their testimony. The goal is to prevent unbiased witnesses from influencing each other. It is known that Abraham Lincoln intentionally filled his cabinet with rival politicians who had extremely different ideologies. When making decisions, Lincoln always encouraged vigorous debate and discussion.

Shahram Heshmat, Ph.D., is an associate professor emeritus of health economics of addiction at the University of Illinois at Springfield.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

COGNITIVE BIASES AND STRATEGIC DECISION PROCESSES: AN INTEGRATWE PERSPECTIVE

Previous studies have not adequately addressed the role of cognitive biases in strategie decisiorr processes. In this article we suggest that cognitive biases are systematically associated with strategic decision processes. Different decision processes tend to accentuate particular types of eognitive fjias. We develop an integrative framework to explore the presence of four basic tyq^es of eognitive bias under five difiererit modes of decision making. The cognitive biases include prior hypotheses and focusing on limited targets, exposure to limited alternatives, iiiseri-sitiv-ity to outcome probabilities and illusion of manageability-. The five mcjdes of strategic decision making are rational, avoidance, logical incrementalist, political and garbage can. We suggest a number of key propositions to facilitate empirical testing of the various contingent relationships implicit in the framework. I^istly, we discuss the implications of this framework for research and managerial practice.

Related Papers

Management for Professionals

This article, through some examples, introduces a few types of biases in strategic decisions and the reasons for their biases. It proposes a strategic decision tendentious model on the basis of consideration of internal and external situations. Three important principles that ought to be complied with in the strategic decision makings are proposed and introduced.

Business: Theory and Practice

Renato Luz Brito Costa

Decision-making is a multidisciplinary and ubiquitous phenomenon in organizations, and it can be observed at the individual, group, and organizational levels. Decision making plays, however, an increasingly important role for the manager, whose cognitive competence is reflected in his ability to identify potential opportunities, to immediately detect and solve the problems he faces, and to predict and prevent future threats. Nevertheless, to what extent do managers of the most diverse sectors and industries continue to rely on false knowledge when they have better strategies at their disposal? The present article proposes, through the application of bibliographically based instruments, the diagnosis of three prominent biases – overconfidence, optimism, and anchoring effect – in managers of the Portuguese port sector, as well as also seeking to establish a comparative analysis with the conclusions already documented in relation to the Brazilian civil construction sector. In addition,...

Advances in Human Resources Management and Organizational Development

Thibault Jacquemin

In today's post-bureaucratic organization, where decision-making is decentralized, most managers are confronted with highly complex situations where time-constraint and availability of information makes the decision-making process essential. Studies show that a great amount of decisions are not taken after a rational decision-making process but rather rely on instinct, emotion or quickly processed information. After briefly describing the journey of thoughts from Rational Choice Theory to the emergence of Behavioral Economics, this chapter will elaborate on the mechanisms that are at play in decision-making in an attempt to understand the root causes of cognitive biases, using the theory of Kahneman's (2011) System 1 and System 2. It will discuss the linkage between the complexity of decision-making and post-bureaucratic organization.

Long Range Planning

Mumin Dayan

Strategic Management Journal

Gerard P Hodgkinson

Wright and Goodwin (2002) maintain that, in terms of experimental design and ecological validity, Hodgkinson et al. (1999) failed to demonstrate either that the framing bias is likely to be of salience in strategic decision making, or that causal cognitive mapping provides an effective means of limiting the damage accruing from this bias. In reply, we show that there is ample evidence to support both of our original claims. Moreover, using Wright and Goodwin's own data set, we demonstrate that our studies did in fact attain appropriate levels of ecological validity, and that their proposed alternative to causal cognitive mapping, a decision tree approach, is far from ‘simpler.’ Wright and Goodwin's approach not only fails to eliminate the framing bias—it leads to confusion. Copyright © 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Jane McKenzie

Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to challenge an over-reliance on past experience as the cognitive underpinning for strategic decisions. It seeks to argue that, in complex and unknowable conditions, effective leaders use three distinct and complementary thinking capacities, which go beyond those normally learned during their rise to the top. Design/methodology/approach – A conceptual model of thinking capacities is justified through a review of the psychology literature; the face validity of the proposed model is supported through six in-depth interviews with successful CEOs. Findings – A model of non-conventional thinking capacities describes how strategic decision-makers make choices that are better adapted to the conditions of uncertainty, ambiguity and contradiction, which prevail in complex situations. These capacities are complementary to the more conventional approaches generally used in thinking about decisions. Practical implications – The paper aims to stimulate awareness of the limitations of habitual mental responses in the face of difficult strategic decisions. It challenges leaders consciously to extend their abilities beyond conventional expectations to a higher order of thinking that is better suited to multi-stakeholder situations in complex environments. Originality/value – The paper responds to the challenge of McKenna and Martin-Smith to develop new theoretical approaches to complex environments. It extends conventional approaches to decision making by synthesising from the literature some essential thinking capacities, which are well suited to the demands of situations dominated by uncertainty, ambiguity and contradiction.

Jurnal Ekonomi Perusahaan

Bilson Simamora

Extant studies hold that the decision quality at the very moment of choice indicates future task accomplishment. However, regarding individual-making, the decision’s strategic nature still received little attention from scientists so far. For that reason, the author utilizes the strategic decision dimensions of justifiability, confidence, and satisfaction to form a new concept called strategic decisional beliefs. Making self-efficacy, motivation, subjective well-being, loyalty, and switching likelihood as the concept’s consequences under investigation, the author tests the concept using data from 350 new students chosen judgmentally. As expected, exploratory factor analysis with maximum likelihood extraction offers only one latent variable for the three underlined dimensions. Further investigation with confirmatory factor analysis indicates that all items are internally valid, reliable, and solidly merged into a single construct with a close fit measurement model. Good-fit structura...

Marketing Letters

Kim P Corfman , Marian Moore

This goal of this paper is to establish a research agenda that will lead to a stream of research that closes the gap between actual and normative strategic managerial decision making. We start by distinguishing strategic managerial decision making (choices) from other choices. Next, we propose a conceptual model of how managers make strategic decisions that is consistent with the observed gap between actual and normative decision making. This framework suggests a series of interesting issues, both descriptive and prescriptive in nature, about the strategic decision-making process that define our proposed research agenda.

Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2013, Volume 61, Issue 7, pp. 2117-2122.

The aim of the paper is to demonstrate the impact of heuristics, biases and psychological traps on the decision making. Heuristics are unconscious routines people use to cope with the complexity inherent in most decision situations. They serve as mental shortcuts that help people to simplify and structure the information encountered in the world. These heuristics could be quite useful in some situations, while in others they can lead to severe and systematic errors, based on significant deviations from the fundamental principles of statistics, probability and sound judgment. This paper focuses on illustrating the existence of the anchoring, availability, and representativeness heuristics, originally described by Tversky & Kahneman in the early 1970's. The anchoring heuristic is a tendency to focus on the initial information, estimate or perception (even random or irrelevant number) as a starting point. People tend to give disproportionate weight to the initial information they receive. The availability heuristic explains why highly imaginable or vivid information have a disproportionate effect on people’s decisions. The representativeness heuristic causes that people rely on highly specific scenarios, ignore base rates, draw conclusions based on small samples and neglect scope. Mentioned phenomena are illustrated and supported by evidence based on the statistical analysis of the results of a questionnaire.

RELATED PAPERS

G. Tsetskhladze (ed.), Ionians in the West and East. Proceedings of an International Conference ‘Ionians in the East and West’, Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya-Empúries, Empúries/L’Escala, Spain, 26–29 October, 2015

Yasar Ersoy

PPGA - UCS Mostra de iniciação científica

Leane Filipetto , Marcelo Bergonsi

Flavio Cesar Freitas Vieira

International Journal of Scientific Research

Kashinatha Shenoy

International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition

Chitradevi Kaniraja

Feddes Repertorium

MUHAMMAD IQBAL

Yonsei Medical Journal

Security Professionalisation: The Journey towards Recognition as a Profession

Orlando Mardner

Bheki Maliba

Physics Letters B

Jan De Boer

Reproduction in Domestic Animals

Ingeborgh Polis

Journal of Neuro-Oncology

Paolo Galluzzi

Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy

melkamu tilahun

Iraqi Journal for Administrative Sciences

Yaser Mahmod Fahad - ياسر محمود فهد

原版复刻阿卡迪亚大学毕业证 uvic毕业证文凭学位证书毕业证认证原版一模一样

East African Medical Journal

Mourine Kangogo

Journal of Veterinary Medical Science

Dominiek Maes

2015 9th International Conference on Software, Knowledge, Information Management and Applications (SKIMA)

Ashok Kumar Pant

LETICIA FLORES PULIDO

Tebuireng: Journal of Islamic Studies and Society

Mukhsin Achmad Achmad, S.Ag., M.Ag.

Jurnal Penelitian dan Pengembangan Pendidikan

Dodi Adnyana

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Skip navigation

World Leaders in Research-Based User Experience

Confirmation bias in ux.

March 13, 2022 2022-03-13

- Email article

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Twitter

When scanning your social-media feeds, did it ever happen to you to ignore articles posted by friends with political views different than yours? Yet, you probably paid attention to the content shared by those who are on your side of the political spectrum. This is an example of confirmation bias — a term that was first introduced by psychologist Peter Wason in 1960 and that refers to the tendency to let prior beliefs influence how we perceive new information.

Definition : Confirmation bias is a cognitive error that occurs when people pursue or analyze information in a way that directly conforms with their existing beliefs or preconceptions. Confirmation bias will lead people to discard information that contradicts their existing beliefs, even if the information is factual.

Confirmation bias can be seen as an instance of priming — our prior beliefs influence how we search for new information and distort how we interpret it. It is a cost-efficient way to understand the world — after all, it’s easier to stick with a hypothesis than to discard it and come up with another one instead.

Here are some typical ways in which confirmation bias manifests:

- People tend to ignore information that challenges their existing beliefs . Often, this is because our egos get in the way of unbiased thinking. Ego can cloud our judgment, causing us to feel uncomfortable with information that challenges our beliefs.

- People tend to seek information that confirms their existing beliefs . Not only is confirming information more comfortable to interpret, but doing so helps us justify our beliefs and fuels our confidence in the subject.

- People exhibit this bias when they selectively gather or recall information or when they interpret it in a biased manner. This can look like hearing only one side of a news story or interpreting the story in a way that confirms prior beliefs.

The impact is greater for emotionally charged issues and deeply ingrained beliefs , such as religion, race, politics, women’s rights, or climate change.

Of more importance to those working in UX, the more invested you are in your assumptions about the design or the users, the stronger the confirmation bias. For example, if you have worked for months to create a design, you will be very likely to believe usability evidence that says that the design is fine and be skeptical of any findings that show problems with the design. On the other hand, if you only worked for a day or two on a paper prototype before running a usability study, you will be less biased in interpreting the findings.

In This Article:

Confirmation bias in ux research and design, tips for preventing confirmation bias in ux research, why confirmation bias is important.

Confirmation bias can have serious consequences in UX research and design because it can distort practitioners’ perspectives by excluding alternative options and delegitimizing disagreement. Recognizing and overcoming confirmation bias will lead to improved decision making, research, and, eventually, better products and user experiences.

For example, imagine an ecommerce site that, in spite of a lot of traffic and users who put products in their bags, has low sales. The designers hypothesize that the inferior performance is due to a poorly designed checkout button (preconceived belief). They decide to collect feedback and ask the following survey question:

Was the red checkout button difficult to locate?

There are several problems with this question:

- The focus on the checkout button biases the study to collect evidence in favor of the prior hypothesis that designers started with. Even if the responses indicate that yes, the button was difficult to find, that issue might not be the biggest issue users have with the site or with the checkout process.

- The negative language ( difficult to locate) primes participants to think about the issues with this button (rather than about whether the button was effective or not).

- The close-ended binary question leaves users with no room for providing context about the actual experience and issues that they encountered.

A better, nonleading question is:

How was the checkout process? Please explain anything that you liked or disliked about the process.

This question avoids priming the participants and does not cater to designer’s confirmation bias. It recognizes that the checkout process might be the problem and allows the respondents to elaborate and give contextual feedback.

To summarize, there are many ways that in which confirmation bias can affect UX professionals:

- Asking biasing questions and (more generally) setting up a test so that it seeks to confirm the researchers’ assumptions rather than investigating other possible issues and causes for a problem

- Ignoring evidence that points in a different direction (e.g., in a usability test)

- Interpreting ambiguous evidence in the favor of the researchers’ prior hypotheses or assumptions

Being aware of confirmation bias is the first step in avoiding it. Here are a few ways in which UX researchers and designers can prevent confirmation bias:

Research rather than validate . UX professionals should start with an open mindset and aim to test hypotheses and assumptions instead of validating them. The goal of research is to uncover things we did not know beforehand, not to confirm our expectations. Designers should be nimble and able to quickly recognize that they are on the wrong path instead of spending time and resources to dig deeper into an unpromising design solution. To avoid this cycle of validation, where designers assume that the test will confirm what they already believe to be true, understand that the planning stage of any user study should include a comprehensive review of the test objectives.

Get early data. As mentioned above, the less time, resources, and emotions you have vested in a certain design, the less biased you will be when interpreting observations from user research. Thus, the sooner you get empirical data from the target audience, the more likely you are to be relatively unbiased when analyzing the data and acting on the findings.

Ask nonbiasing questions . When UX practitioners gather feedback from users, whether through usability testing , diary studies , or interviews , avoid asking leading questions. Leading questions prime the test participants and make them sensitive to those issues that the researchers may be interested in.

Often, when you have a specific hypothesis, it can be difficult to come up with a question that is not leading (like in our checkout example). Always step back and ask yourself: is there any way in which this question may be suggesting a response to the participant? Could the participant guess what my hypothesis is from this question? If the answer is yes, rephrase the question. Participants are human beings and they will often want to feel helpful and please the facilitator by trying hard to consider what they think may be the researcher’s interest and point of view.

Use triangulation . Multiple data sources can not only boost the credibility of your research, but can prevent confirmation biases. It can be easy to twist and turn one research finding to match your hypothesis, but it’s a lot more difficult to do so with data coming from several different sources such as user testing, analytics, quantitative studies, or customer-service logs. In the example above, imagine that the designers looked at the site’s behavior flow in some analytics software before seeking user feedback. They might have found that most dropoffs happen later in the checkout flow, long after the checkout button was clicked. This observation alone could lead them to ask better questions. Or, let’s say that the user feedback indicated that users didn’t have any issues with the checkout process, but the analytics data clearly shows that users aren’t making it through the entire process. Here, perhaps the survey didn’t ask the right question, ignoring the real reason behind the high abandonment rate.

Involve fresh eyes in research planning and analysis. Whenever possible, ask a colleague who is not directly involved in your project to go through your study plan and sit in your presentation of the findings. Often, someone who has no background knowledge about prior assumptions can bring a new, neutral perspective and more easily help you identify the effects of confirmation bias.