- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Reasons to Submit

- About Journal of Surgical Protocols and Research Methodologies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, contents of a research study protocol, conflict of interest statement, how to write a research study protocol.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Julien Al Shakarchi, How to write a research study protocol, Journal of Surgical Protocols and Research Methodologies , Volume 2022, Issue 1, January 2022, snab008, https://doi.org/10.1093/jsprm/snab008

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A study protocol is an important document that specifies the research plan for a clinical study. Many funders such as the NHS Health Research Authority encourage researchers to publish their study protocols to create a record of the methodology and reduce duplication of research effort. In this paper, we will describe how to write a research study protocol.

A study protocol is an essential part of a research project. It describes the study in detail to allow all members of the team to know and adhere to the steps of the methodology. Most funders, such as the NHS Health Research Authority in the United Kingdom, encourage researchers to publish their study protocols to create a record of the methodology, help with publication of the study and reduce duplication of research effort. In this paper, we will explain how to write a research protocol by describing what should be included.

Introduction

The introduction is vital in setting the need for the planned research and the context of the current evidence. It should be supported by a background to the topic with appropriate references to the literature. A thorough review of the available evidence is expected to document the need for the planned research. This should be followed by a brief description of the study and the target population. A clear explanation for the rationale of the project is also expected to describe the research question and justify the need of the study.

Methods and analysis

A suitable study design and methodology should be chosen to reflect the aims of the research. This section should explain the study design: single centre or multicentre, retrospective or prospective, controlled or uncontrolled, randomised or not, and observational or experimental. Efforts should be made to explain why that particular design has been chosen. The studied population should be clearly defined with inclusion and exclusion criteria. These criteria will define the characteristics of the population the study is proposing to investigate and therefore outline the applicability to the reader. The size of the sample should be calculated with a power calculation if possible.

The protocol should describe the screening process about how, when and where patients will be recruited in the process. In the setting of a multicentre study, each participating unit should adhere to the same recruiting model or the differences should be described in the protocol. Informed consent must be obtained prior to any individual participating in the study. The protocol should fully describe the process of gaining informed consent that should include a patient information sheet and assessment of his or her capacity.

The intervention should be described in sufficient detail to allow an external individual or group to replicate the study. The differences in any changes of routine care should be explained. The primary and secondary outcomes should be clearly defined and an explanation of their clinical relevance is recommended. Data collection methods should be described in detail as well as where the data will be kept secured. Analysis of the data should be explained with clear statistical methods. There should also be plans on how any reported adverse events and other unintended effects of trial interventions or trial conduct will be reported, collected and managed.

Ethics and dissemination

A clear explanation of the risk and benefits to the participants should be included as well as addressing any specific ethical considerations. The protocol should clearly state the approvals the research has gained and the minimum expected would be ethical and local research approvals. For multicentre studies, the protocol should also include a statement of how the protocol is in line with requirements to gain approval to conduct the study at each proposed sites.

It is essential to comment on how personal information about potential and enrolled participants will be collected, shared and maintained in order to protect confidentiality. This part of the protocol should also state who owns the data arising from the study and for how long the data will be stored. It should explain that on completion of the study, the data will be analysed and a final study report will be written. We would advise to explain if there are any plans to notify the participants of the outcome of the study, either by provision of the publication or via another form of communication.

The authorship of any publication should have transparent and fair criteria, which should be described in this section of the protocol. By doing so, it will resolve any issues arising at the publication stage.

Funding statement

It is important to explain who are the sponsors and funders of the study. It should clarify the involvement and potential influence of any party. The sponsor is defined as the institution or organisation assuming overall responsibility for the study. Identification of the study sponsor provides transparency and accountability. The protocol should explicitly outline the roles and responsibilities of any funder(s) in study design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing and dissemination of results. Any competing interests of the investigators should also be stated in this section.

A study protocol is an important document that specifies the research plan for a clinical study. It should be written in detail and researchers should aim to publish their study protocols as it is encouraged by many funders. The spirit 2013 statement provides a useful checklist on what should be included in a research protocol [ 1 ]. In this paper, we have explained a straightforward approach to writing a research study protocol.

None declared.

Chan A-W , Tetzlaff JM , Gøtzsche PC , Altman DG , Mann H , Berlin J , et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials . BMJ 2013 ; 346 : e7586 .

Google Scholar

- conflict of interest

- national health service (uk)

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- JSPRM Twitter

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2752-616X

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press and JSCR Publishing Ltd

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, developing a robust case study protocol.

Management Research Review

ISSN : 2040-8269

Article publication date: 4 July 2023

Issue publication date: 11 January 2024

Case study research has been applied across numerous fields and provides an established methodology for exploring and understanding various research contexts. This paper aims to aid in developing methodological rigor by investigating the approaches of establishing validity and reliability.

Design/methodology/approach

Based on a systematic review of relevant literature, this paper catalogs the use of validity and reliability measures within academic publications between 2008 and 2018. The review analyzes case study research across 15 peer-reviewed journals (total of 1,372 articles) and highlights the application of validity and reliability measures.

The evidence of the systematic literature review suggests that validity measures appear well established and widely reported within case study–based research articles. However, measures and test procedures related to research reliability appear underrepresented within analyzed articles.

Originality/value

As shown by the presented results, there is a need for more significant reporting of the procedures used related to research reliability. Toward this, the features of a robust case study protocol are defined and discussed.

- Case study research

- Systematic literature review

Burnard, K.J. (2024), "Developing a robust case study protocol", Management Research Review , Vol. 47 No. 2, pp. 204-225. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-11-2021-0821

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Open access

- Published: 16 February 2022

The “case” for case studies: why we need high-quality examples of global implementation research

- Blythe Beecroft ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6254-421X 1 ,

- Rachel Sturke 1 ,

- Gila Neta 2 &

- Rohit Ramaswamy 3

Implementation Science Communications volume 3 , Article number: 15 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3561 Accesses

5 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Rigorous and systematic documented examples of implementation research in global contexts can be a valuable resource and help build research capacity. In the context of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), there is a need for practical examples of how to conduct implementation studies. To address this gap, Fogarty’s Center for Global Health Studies in collaboration with the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and the National Cancer Institute is commissioning a collection of implementation science case studies in LMICs that describe key components of conducting implementation research, including how to select, adapt, and apply implementation science models, theories, and frameworks to these settings; develop and test implementation strategies; and evaluate implementation processes and outcomes. The case studies describe implementation research in various disease areas in LMICs around the world. This commentary highlights the value of case study methods commonly used in law and business schools as a source of “thick” (i.e., context-rich) description and a teaching tool for global implementation researchers. It addresses the independent merit of case studies as an evaluation approach for disseminating high-quality research in a format that is useful to a broad range of stakeholders. This commentary finally describes an approach for developing high-quality case studies of global implementation research, in order to be of value to a broad audience of researchers and practitioners.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

Reinforcing the need for “thick” (i.e., context-rich) descriptions of implementation studies

Highlighting the utility of case studies as a dissemination strategy for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers

Articulating the value of detailed case studies as a teaching tool for global implementation researchers

Describing a method for developing high-quality case studies of global implementation research

Research capacity for implementation science remains limited in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Various stakeholders, including NIH-funded implementation researchers and practitioners, often inquire about how to apply implementation science methods and have requested additional resources and training to support implementation capacity building. This is in part due to a dearth of practical examples for both researchers and practitioners of how to select, adapt, and apply implementation science models, theories, and frameworks to these settings; how to evaluate implementation processes and outcomes; and how to develop and test implementation strategies. The need for detailed documentation of implementation research in all settings has been well established, and guidelines for documentation of implementation research studies have been created [ 1 , 2 ]. But the mere availability of checklists and guidelines in and of themselves does not result in comprehensive documentation that is useful for learning, as has been pointed out by many systematic reviews of implementation science and quality improvement studies ([ 3 , 4 ]). It has also been observed that documentation alone is not enough, and there is a need for mentors to translate abstract theories into context-appropriate research designs and practice approaches [ 5 ]. Because of the especially acute shortage of mentors and coaches in LMIC settings, we propose that documentation with “thick” descriptions that go beyond checklists and guidelines are needed to make the field more useful to emerging professionals [ 6 ]. We suggest that the case study method intended to “explore the space between the world of theory and the experience of practice” [ 7 ] that has been used successfully for over a century by law and business schools as a teaching aid can be of value to develop detailed narratives of implementation research projects. In this definition, we are not referring to the case study as a qualitative research method [ 8 ], but as a rich and detailed method of retrospective documentation to aid teaching, practice, and research. In this context, our case studies are akin to “single-institution or single-patient descriptions” [ 9 ] called “case reports” or “case examples” in other fields. As these terms are rarely used in global health, we have used the words “case studies” in this paper but reiterate that they do not refer to case study research designs.

Fogarty’s Center for Global Health Studies (CGHS) in collaboration with the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) is commissioning a collection of implementation science case studies that describe implementation research focusing on various disease areas in different (LMIC) contexts around the world. These case study descriptions will provide guidance on the process of conducting implementation science studies and will highlight the impact these studies have had on practice and policy in global health contexts. This brief note makes a case for using case studies to document and disseminate implementation research, describes the CGHS approach to case study development and poses evaluation questions that need to be answered to better understand the utility of case studies. This effort is intended to develop a set of useful examples for LMIC researchers, practitioners, and policymakers, but also to assess and improve the use of case studies as a tested documentation methodology in implementation research.

The “case” for case studies

A preliminary landscape analysis of the field conducted by CGHS found that there are not many descriptions of global implementation science projects in a case study format in the peer-reviewed or gray literature, and those that exist are embedded in the content of academic teaching materials. There is not a cohesive collection, especially relating to health, that illustrates how implementation research has been conducted in varied organizations, countries, or disease areas. This new collection will add value in three different ways: as a dissemination strategy, as a tool for capacity building, and as a vehicle for stimulating better research.

Case studies as a dissemination strategy

Case studies have independent merit as an evaluation approach for disseminating high-quality research in a format that is useful to a broad range of stakeholders. The Medical Research Council (MRC) has recommended process evaluation as a useful approach to examine complex implementation, mechanisms of impact, and context [ 10 ]. Guidelines on documentation of implementation recommend that researchers should provide “detailed descriptions of interventions (and implementation strategies) in published papers, clarify assumed change processes and design principles, provide access to manuals and protocols that provide information about the clinical interventions or implementation strategies, and give detailed descriptions of active control conditions” [ 1 ]. Case studies can be thought of as a form of post hoc process evaluation, to disseminate how the delivery of an intervention is achieved, the mechanisms by which implementation strategies produce change, or how context impacts implementation and related outcomes.

Case studies as a capacity building tool

In addition, case studies can address the universal recognition of the need for more capacity building in Implementation Science , especially in LMIC settings. Case studies have been shown to address common pedagogical challenges in helping students learn by allowing students to dissect and explore limitations, adaptations, and utilization of theories, thereby creating a bridge between theories presented in a classroom and their application in the field [ 11 ]. A recent learning needs assessment for implementation researchers, practitioners, and policymakers in LMICs conducted by Turner et al. [ 12 ] reflected a universal consensus on the need for context-specific knowledge about how to apply implementation science in practice, delivered in an interactive format supported by mentorship. A collection of case studies is a valuable and scalable resource to meet this need.

Using case studies to strengthen implementation research

Descriptions of research using studies can illustrate not just whether implementation research had an impact on practice and policy, but how, why, under what circumstances, and to whom, which is the ultimate goal of generating generalizable knowledge about how to implement. Using diverse cases to demonstrate how a variety of research designs have been used to answer complex implementation questions provides researchers with a palette of design options and examples of their use. A framework developed by Minary et al. [ 13 ] illustrates the wide variety of research designs that are useful for complex interventions, depending on whether the emphasis is on internal and external validity or whether knowledge about content and process or about outcomes is more important. A collection of case studies would be invaluable to researchers seeking to develop appropriate designs for their work. In addition, the detailed documentation provided through these case descriptions will hopefully motivate researchers to document their own studies better using the guidelines described earlier.

Developing and testing the case study creation process: the CGHS approach

Writing case studies that satisfy the objectives described above is an implementation science undertaking in itself that requires the engagement of a variety of stakeholders and planned implementation strategies. The CGHS team responsible for commissioning the case studies began this process in 2017 and followed the approach detailed below to test the process of case study development.

Conducted 25+ consultations with various implementation science experts on gaps in the field and the relevance of global case studies

Convened a 15-member Steering Committee Footnote 1 of implementation scientists with diverse expertise, from various academic institutions and NIH institutes to serve as technical experts and to help guide the development and execution of the project

Developed a case study protocol in partnership with the Steering Committee to guide the inclusion of key elements in the case studies

Commissioned two pilot cases Footnote 2 to assess the feasibility and utility of the case study protocol and elicited feedback on the writing experience and how it could be improved as the collection expands

Led an iterative pilot writing process where each case study writing team developed several drafts, which were reviewed by CGHS staff and a designated member of the Steering Committee

Truncated and adjusted the protocol in response to input from the pilot case study authors teams

Developed a comprehensive grid with the Steering Committee, outlining the key dimensions of implementation science that are significant and would be important areas of focus for future case studies. The grid will be used to evaluate potential case applicants and is intended to help foster diversity of focus and content, in addition to geography

Implementing the process: the call for case studies

In March of 2021, CGHS issued a closed call for case studies to solicit applications from a pool of researchers. Potential applicants completed the comprehensive grid in addition to a case study proposal. Applicants will go through a three-tier screening and review process. CGHS will initially screen the applications for completeness to ensure all required elements are present. Each case study application will then be reviewed by two Steering Committee members for content and scientific rigor and given a numerical score based on the selection criteria. Finally, the CGHS team will screen the applications to ensure diversity of implementation elements, geography, and disease area. Approximately 10 case studies will be selected for development in an iterative process. Each case team will present their case drafts to the Steering Committee, which will collectively workshop the drafts in multiple sittings, drawing on the committee’s implementation science expertise. Once case study manuscripts are accepted by the Steering Committee, they will be submitted to Implementation Science Communications for independent review by the journal. CGHS intends for the case studies to be published collectively, but on a rolling basis as they are accepted for publication.

Future research: evaluating the effectiveness of the case study approach

This commentary has put forth arguments for the potential value of case studies for documenting implementation research for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. Case studies not only provide a way to underscore how implementation science can advance practice and policy in LMICs, but also offer guidance on how to conduct implementation research tailored to global contexts. However, there is little empirical evidence about the validity of these arguments. The creation of this body of case studies will allow us to study why, how, how often, and by whom these case studies are used. This is a valuable opportunity to learn and use that information to better inform future use of this approach as a capacity-building or dissemination strategy.

Conclusions

Similar to their use in law and business, case study descriptions of implementation research could be an important mechanism to counteract the paucity of training programs and mentors to meet the demands of global health researchers. If the evaluation results indicate that the case study creation process produces useful products that enhance learning to improve future implementation research, a mechanism needs to be put in place to create more case studies than the small set that can be generated through this initiative. There will be a need to create a set of documentation guidelines that complement those that currently exist and a mechanism to solicit, review, publish, and disseminate case studies from a wide variety of researchers and practitioners. Journals such as Implementation Science or Implementation Science Communications can facilitate this effort by either creating a new article type or by considering a new journal with a focus on rigorous and systematic case study descriptions of implementation research and practice. An example that could serve as a guide is BMJ Open Quality , which is a peer-reviewed, open-access journal focused on healthcare improvement. In addition to original research and systematic reviews, the journal publishes two article types: Quality Improvement Report and Quality Education Report to document healthcare quality improvement programs and training. The journal offers resources for authors to document their work rigorously. Recently, a new journal titled BMJ Open Quality South Asia has been released to disseminate regional research. We hope that our efforts in sponsoring and publishing these cases, and in setting up a process to support their creation, will make an important contribution to the field and become a mechanism for sharing knowledge that accelerates the growth of implementation science in LMIC settings.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Rohit Ramaswamy, CCHMC, Gila Neta, NCI NIH, Theresa Betancourt, BC, Ross Brownson, WASU, David Chambers, NCI NIH, Sharon Straus, University of Toronto, Greg Aarons, UCSD, Bryan Weiner, UW, Sonia Lee, NICHD NIH, Andrea Horvath Marques, NIMH NIH, Susannah Allison, NIMH NIH, Suzy Pollard, NIMH NIH, Chris Gordon, NIMH NIH, Kenny Sherr, UW, Usman Hamdani, HDR Foundation Pakistan, Linda Kupfer, FIC NIH

The first pilot case was led by the Human Development Research Foundation (HDRF) in Pakistan and examines scaling up evidenced-based care for children with developmental disorders in rural Pakistan. The second pilot was led by Boston College and investigates alternate delivery platforms and implementation models for bringing evidence-based behavioral Interventions to scale for youth facing adversity in Sierra Leone to close the mental health treatment gap.

Abbreviations

Low- and middle-income countries

Center for Global Health Studies

National Cancer Institute

Medical Research Council

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation Sci. 2013;8(139) [cited 2021 May];. Available from: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 .

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, et al. for the StaRI group. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795 [cited 2021Sept]. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/356/bmj.i6795 .

Article Google Scholar

Brouwers MC, De Vito C, Bahirathan L, Carol A, Carroll JC, Cotterchio M, et al. What implementation interventions increase cancer screening rates? A systematic review. Implementation Sci. 2011; [cited 2021 Sept];6:111. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3197548/ .

Nadeem E, Gleacher A, Beidas RS. Consultation as an implementation strategy for evidence-based practices across multiple contexts: unpacking the black box. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(6):439–50. [cited 2021 Sept]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10488-013-0502-8 .

Darnell D, Dorsey CN, Melvin A, Chi J, Lyon AR, Lewis CC. A content analysis of dissemination and implementation science resource initiatives: what types of resources do they offer to advance the field? Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):137 [cited 2021 Sept];. Available from: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-017-0673-x .

Geertz C. Thick description: toward an interpretive theory of culture In: The interpretation of cultures: selected essays. New York: Basic Books; 1973. p. 3–32.

Breslin M, Buchanan R. On the case study method of research and teaching in design. Design Issues. 2008;24(1):36–40 [cited 2021 Sept]. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25224148 .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:100. [cited 2021 Sept]. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alpi KM, Evans JJ. Distinguishing case study as a research method from case reports as a publication type. J Med Libr Assoc. 2019;107(1):1–5 Jan [cited 2021 Sept]. Available from: https://jmla.pitt.edu/ojs/jmla/article/view/615 .

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258. March [cited 2021 May]. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h1258 . https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258 .

Velenchik AD. The case method as a strategy for teaching policy analysis to undergraduates. J. Econ. Educ. 1995;26(1):29–38.

Turner MW, Bogdewic S, Agha E, Blanchard C, Sturke R, Pettifor A, et al. Learning needs assessment for multi-stakeholder implementation science training in LMIC settings: findings and recommendations. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(134) [cited 2021 May]. Available from: https://implementationsciencecomms.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s43058-021-00238-2 .

Minary L, Trompette J, Kivits J, Cambon L, Tarquinio C, Alla F. Which design to evaluate complex interventions? Toward a methodological framework through a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(92) [cited 2021 May]. Available from: https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12874-019-0736-6 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent any official position or policy of the US National Institutes of Health or the US Department of Health and Human Services or any other institutions with which authors are affiliated.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Fogarty International Center, US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA

Blythe Beecroft & Rachel Sturke

National Cancer Institute, US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, USA

Rohit Ramaswamy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BB, RS, and GN contributed to the conceptualization of the manuscript with leadership from RR. BB and RS drafted the main text. RR and GN reviewed and contributed additional content to further develop the text. All authors have read and agreed to the contents of the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Blythe Beecroft .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Beecroft, B., Sturke, R., Neta, G. et al. The “case” for case studies: why we need high-quality examples of global implementation research. Implement Sci Commun 3 , 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00227-5

Download citation

Received : 05 August 2021

Accepted : 27 September 2021

Published : 16 February 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00227-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Case studies

- Global implementation science

Implementation Science Communications

ISSN: 2662-2211

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Basic Methods Handbook for Clinical Orthopaedic Research pp 65–73 Cite as

How to Write a Study Protocol

- Lukas B. Moser 8 , 9 &

- Michael T. Hirschmann 8 , 9

- First Online: 02 February 2019

2366 Accesses

This chapter aims to provide a guide for young trainees writing their first study protocol. It includes important aspects junior researchers should consider before getting started and preparing their first study protocol. After having read the chapter, the reader should have a good idea about what a study protocol is about and be able to answer the question why, when, and how a study protocol should be written. Finally, the reader will be prepared to master the very first step of conducting a successful study—writing a brief, concise, but comprehensive study protocol.

Study protocol examples of typical clinical scenarios further illustrate the approach to this mandatory and important part of a research project.

- Scientific writing

- Instruction

- Study protocol

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Al-Jundi A, Sakka S. Protocol writing in clinical research. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZE10–3.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Babyak MA. What you see may not be what you get: a brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:411–21.

PubMed Google Scholar

Bando K, Sato T. Did you write a protocol before starting your project? Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;63:71–7.

Article Google Scholar

Barletta JF. Conducting a successful residency research project. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72:92.

Brody BA, McCullough LB, Sharp RR. Consensus and controversy in clinical research ethics. JAMA. 2005;294:1411–4.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Doran G. There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Manag Rev. 1981;70:35–6.

Google Scholar

Doran PC. Understanding dentures: instructions to patients. J Colo Dent Assoc. 1981;59:4–8.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Fleming TR, DeMets DL. Surrogate end points in clinical trials: are we being misled? Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:605–13.

Fronteira I. How to design a (good) epidemiological observational study: epidemiological research protocol at a glance. Acta Medica Port. 2013;26:731–6.

Ghooi RB, Divekar D. Insurance in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res. 2014;5:145–50.

Gilmore SJ. Evaluating statistics in clinical trials: making the unintelligible intelligible. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:177–84; quiz 185–176.

Huang Y, Gilbert PB. Comparing biomarkers as principal surrogate endpoints. Biometrics. 2011;67:1442–51.

Kanji S. Turning your research idea into a proposal worth funding. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68:458–64.

O’Brien K, Wright J. How to write a protocol. J Orthod. 2002;29:58–61.

Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123:A12–3.

Rosenthal R, Schafer J, Briel M, Bucher HC, Oertli D, Dell-Kuster S. How to write a surgical clinical research protocol: literature review and practical guide. Am J Surg. 2014;207:299–312.

Sade RM, Akins CW, Weisel RD. Managing conflicts of interest. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:971–2.

Skelly AC, Dettori JR, Brodt ED. Assessing bias: the importance of considering confounding. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2012;3:9–12.

Van Spall HG, Toren A, Kiss A, Fowler RA. Eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials published in high-impact general medical journals: a systematic sampling review. JAMA. 2007;297:1233–40.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e297.

Vavken P, Culen G, Dorotka R. Management of confounding in controlled orthopaedic trials: a cross-sectional study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:985–9.

Warren MD. Aide-memoire for preparing a protocol. Br Med J. 1978;1:1195–6.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Kantonsspital Baselland (Bruderholz, Liestal, Laufen), Bruderholz, Switzerland

Lukas B. Moser & Michael T. Hirschmann

University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michael T. Hirschmann .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

UPMC Rooney Sports Complex, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Volker Musahl

Department of Orthopaedics, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden

Jón Karlsson

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Kantonsspital Baselland (Bruderholz, Laufen und Liestal), Bruderholz, Switzerland

Michael T. Hirschmann

McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Olufemi R. Ayeni

Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, USA

Robert G. Marx

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, IL, USA

Jason L. Koh

Institute for Medical Science in Sports, Osaka Health Science University, Osaka, Japan

Norimasa Nakamura

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 ISAKOS

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Moser, L.B., Hirschmann, M.T. (2019). How to Write a Study Protocol. In: Musahl, V., et al. Basic Methods Handbook for Clinical Orthopaedic Research. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-58254-1_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-58254-1_8

Published : 02 February 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-662-58253-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-662-58254-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 6, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Write an Error-free Research Protocol As Recommended by WHO: 21 Elements You Shouldn’t Miss!

Principal Investigator: Did you draft the research protocol?

Student: Not yet. I have too many questions about it. Why is it important to write a research protocol? Is it similar to research proposal? What should I include in it? How should I structure it? Is there a specific format?

Researchers at an early stage fall short in understanding the purpose and importance of some supplementary documents, let alone how to write them. Let’s better your understanding of writing an acceptance-worthy research protocol.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Protocol?

The research protocol is a document that describes the background, rationale, objective(s), design, methodology, statistical considerations and organization of a clinical trial. It is a document that outlines the clinical research study plan. Furthermore, the research protocol should be designed to provide a satisfactory answer to the research question. The protocol in effect is the cookbook for conducting your study

Why Is Research Protocol Important?

In clinical research, the research protocol is of paramount importance. It forms the basis of a clinical investigation. It ensures the safety of the clinical trial subjects and integrity of the data collected. Serving as a binding document, the research protocol states what you are—and you are not—allowed to study as part of the trial. Furthermore, it is also considered to be the most important document in your application with your Institution’s Review Board (IRB).

It is written with the contributions and inputs from a medical expert, a statistician, pharmacokinetics expert, the clinical research coordinator, and the project manager to ensure all aspects of the study are covered in the final document.

Is Research Protocol Same As Research Proposal?

Often misinterpreted, research protocol is not similar to research proposal. Here are some significant points of difference between a research protocol and a research proposal:

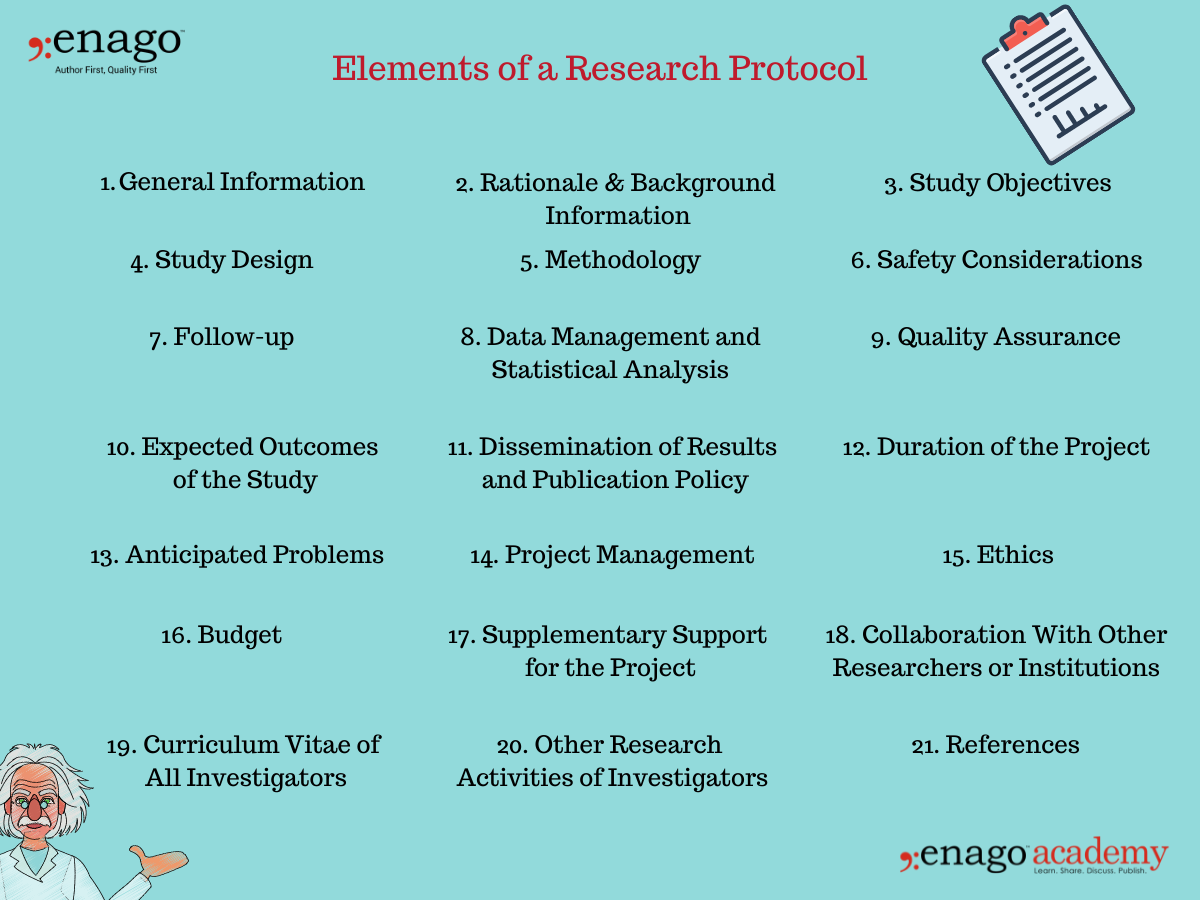

What Are the Elements/Sections of a Research Protocol?

According to Good Clinical Practice guidelines laid by WHO, a research protocol should include the following:

1. General Information

- Protocol title, protocol identifying number (if any), and date.

- Name and address of the funder.

- Name(s) and contact details of the investigator(s) responsible for conducting the research, the research site(s).

- Responsibilities of each investigator.

- Name(s) and address(es) of the clinical laboratory(ies), other medical and/or technical department(s) and/or institutions involved in the research.

2. Rationale & Background Information

- The rationale and background information provides specific reasons for conducting the research in light of pertinent knowledge about the research topic.

- It is a statement that includes the problem that is the basis of the project, the cause of the research problem, and its possible solutions.

- It should be supported with a brief description of the most relevant literatures published on the research topic.

3. Study Objectives

- The study objectives mentioned in the research proposal states what the investigators hope to accomplish. The research is planned based on this section.

- The research proposal objectives should be simple, clear, specific, and stated prior to conducting the research.

- It could be divided into primary and secondary objectives based on their relativity to the research problem and its solution.

4. Study Design

- The study design justifies the scientific integrity and credibility of the research study.

- The study design should include information on the type of study, the research population or the sampling frame, participation criteria (inclusion, exclusion, and withdrawal), and the expected duration of the study.

5. Methodology

- The methodology section is the most critical section of the research protocol.

- It should include detailed information on the interventions to be made, procedures to be used, measurements to be taken, observations to be made, laboratory investigations to be done, etc.

- The methodology should be standardized and clearly defined if multiple sites are engaged in a specified protocol.

6. Safety Considerations

- The safety of participants is a top-tier priority while conducting clinical research .

- Safety aspects of the research should be scrutinized and provided in the research protocol.

7. Follow-up

- The research protocol clearly indicate of what follow up will be provided to the participating subjects.

- It must also include the duration of the follow-up.

8. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

- The research protocol should include information on how the data will be managed, including data handling and coding for computer analysis, monitoring and verification.

- It should clearly outline the statistical methods proposed to be used for the analysis of data.

- For qualitative approaches, specify in detail how the data will be analysed.

9. Quality Assurance

- The research protocol should clearly describe the quality control and quality assurance system.

- These include GCP, follow up by clinical monitors, DSMB, data management, etc.

10. Expected Outcomes of the Study

- This section indicates how the study will contribute to the advancement of current knowledge, how the results will be utilized beyond publications.

- It must mention how the study will affect health care, health systems, or health policies.

11. Dissemination of Results and Publication Policy

- The research protocol should specify not only how the results will be disseminated in the scientific media, but also to the community and/or the participants, the policy makers, etc.

- The publication policy should be clearly discussed as to who will be mentioned as contributors, who will be acknowledged, etc.

12. Duration of the Project

- The protocol should clearly mention the time likely to be taken for completion of each phase of the project.

- Furthermore a detailed timeline for each activity to be undertaken should also be provided.

13. Anticipated Problems

- The investigators may face some difficulties while conducting the clinical research. This section must include all anticipated problems in successfully completing their projects.

- Furthermore, it should also provide possible solutions to deal with these difficulties.

14. Project Management

- This section includes detailed specifications of the role and responsibility of each investigator of the team.

- Everyone involved in the research project must be mentioned here along with the specific duties they have performed in completing the research.

- The research protocol should also describe the ethical considerations relating to the study.

- It should not only be limited to providing ethics approval, but also the issues that are likely to raise ethical concerns.

- Additionally, the ethics section must also describe how the investigator(s) plan to obtain informed consent from the research participants.

- This section should include a detailed commodity-wise and service-wise breakdown of the requested funds.

- It should also include justification of utilization of each listed item.

17. Supplementary Support for the Project

- This section should include information about the received funding and other anticipated funding for the specific project.

18. Collaboration With Other Researchers or Institutions

- Every researcher or institute that has been a part of the research project must be mentioned in detail in this section of the research protocol.

19. Curriculum Vitae of All Investigators

- The CVs of the principal investigator along with all the co-investigators should be attached with the research protocol.

- Ideally, each CV should be limited to one page only, unless a full-length CV is requested.

20. Other Research Activities of Investigators

- A list of all current research projects being conducted by all investigators must be listed here.

21. References

- All relevant references should be mentioned and cited accurately in this section to avoid plagiarism.

How Do You Write a Research Protocol? (Research Protocol Example)

Main Investigator

Number of Involved Centers (for multi-centric studies)

Indicate the reference center

Title of the Study

Protocol ID (acronym)

Keywords (up to 7 specific keywords)

Study Design

Mono-centric/multi-centric

Perspective/retrospective

Controlled/uncontrolled

Open-label/single-blinded or double-blinded

Randomized/non-randomized

n parallel branches/n overlapped branches

Experimental/observational

Endpoints (main primary and secondary endpoints to be listed)

Expected Results

Analyzed Criteria

Main variables/endpoints of the primary analysis

Main variables/endpoints of the secondary analysis

Safety variables

Health Economy (if applicable)

Visits and Examinations

Therapeutic plan and goals

Visits/controls schedule (also with graphics)

Comparison to treatment products (if applicable)

Dose and dosage for the study duration (if applicable)

Formulation and power of the studied drugs (if applicable)

Method of administration of the studied drugs (if applicable)

Informed Consent

Study Population

Short description of the main inclusion, exclusion, and withdrawal criteria

Sample Size

Estimated Duration of the Study

Safety Advisory

Classification Needed

Requested Funds

Additional Features (based on study objectives)

Click Here to Download the Research Protocol Example/Template

Be prepared to conduct your clinical research by writing a detailed research protocol. It is as easy as mentioned in this article. Follow the aforementioned path and write an impactful research protocol. All the best!

Clear as template! Please, I need your help to shape me an authentic PROTOCOL RESEARCH on this theme: Using the competency-based approach to foster EFL post beginner learners’ writing ability: the case of Benin context. I’m about to start studies for a master degree. Please help! Thanks for your collaboration. God bless.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Science under Surveillance: Journals adopt advanced AI to uncover image manipulation

Journals are increasingly turning to cutting-edge AI tools to uncover deceitful images published in manuscripts.…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Demystifying the Role of Confounding Variables in Research

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- [email protected]

- Connecting and sharing with us

- Entrepreneurship

- Growth of firm

- Sales Management

- Retail Management

- Import – Export

- International Business

- Project Management

- Production Management

- Quality Management

- Logistics Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Human Resource Management

- Organizational Culture

- Information System Management

- Corporate Finance

- Stock Market

- Office Management

- Theory of the Firm

- Management Science

- Microeconomics

- Research Process

- Experimental Research

- Research Philosophy

- Management Research

- Writing a thesis

- Writing a paper

- Literature Review

- Action Research

- Qualitative Content Analysis

- Observation

- Phenomenology

- Statistics and Econometrics

- Questionnaire Survey

- Quantitative Content Analysis

- Meta Analysis

The Case Study Protocol

A case study protocol has only one thing in common with a survey questionnaire: Both are directed at a single data point—either a single case (even if the case is part of a larger, multiple-case study) or a single respondent.

Beyond this similarity are major differences. The protocol is more than a questionnaire or instrument. First, the protocol contains the instrument but also contains the procedures and general rales to be followed in using the protocol. Second, the protocol is directed at an entirely different party than that of a survey questionnaire, explained below. Third, having a case study protocol is desirable under all circumstances, but it is essential if you are doing a multiple-case study.

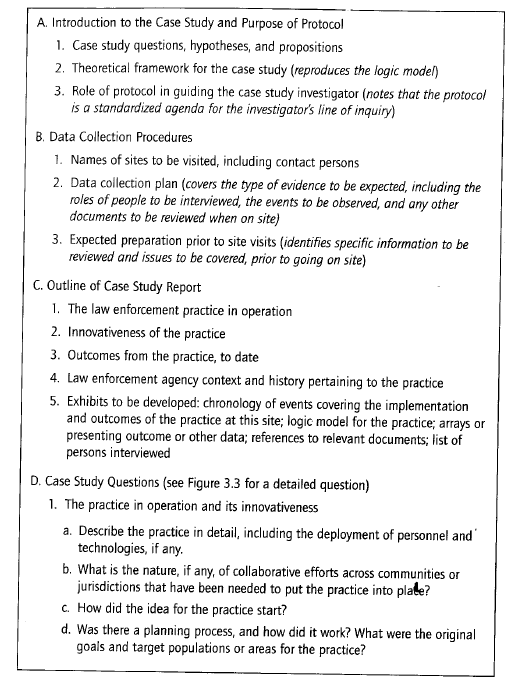

The protocol is a major way of increasing the reliability of case study research and is intended to guide the investigator in carrying out the data collection from a single case (again, even if the single case is one of several in a multiple-case study). Figure 3.2 gives a table of contents from an illustrative protocol, which was used in a study of innovative law enforcement practices supported by federal funds. The practices had been defined earlier through a careful screening process (see later discussion in this chapter for more detail on “screening case study nominations”). Furthermore, because data were to be collected from 18 such cases as part of a multiple-case study, the information about any given case could not be collected in great depth, and thus the number of the case study questions was minimal.

As a general matter, a case study protocol should have the following sections:

- an overview of the case study project (project objectives and auspices, case study issues, and relevant readings about the topic being investigated),

- field procedures (presentation of credentials, access to the case study “sites,” language pertaining to the protection of human subjects, sources of data, and procedural reminders),

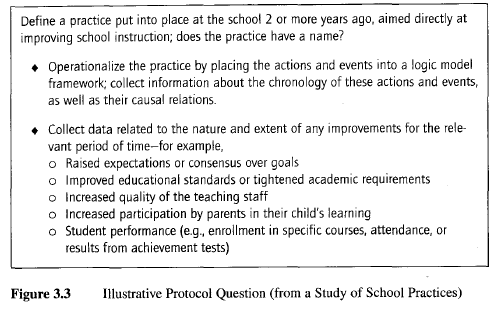

- case study questions (the specific questions that the case study investigator must keep in mind in collecting data, “table shells” for specific arrays of data, and the potential sources of information for answering each question—see Figure 3.3 for an example), and

- a guide for the case study report (outline, format for the data, use and presentation of other documentation, and bibliographical information).

A quick glance at these topics will indicate why the protocol is so important. First, it keeps you targeted on the topic of the case study. Second, preparing the protocol forces you to anticipate several problems, including the way that the case study reports are to be completed. This means, for instance, that you will have to identify the audience for your case study report even before you have conducted your case study. Such forethought will help to avoid mismatches in the long run.

The table of contents of the illustrative protocol in Figure 3.2 reveals another important feature of the case study report: In this instance, the desired report starts by calling for a description of the innovative practice being studied (see item Cl in Figure 3.2)—and only later covers the agency context and history pertaining to the practice (see item C4). This choice reflects the fact that most investigators write too extensively on history and background conditions. While these are important, the description of the subject of the study—the innovative practice—needs more attention.

Each section of the protocol is discussed next.

1. Overview of the Case Study Project

The overview should cover the background information about the project, the substantive issues being investigated, and the relevant readings about the issues.

As for background information, every project has its own context and perspective. Some projects, for instance, are funded by government agencies having a general mission and clientele that need to be remembered in conducting the research. Other projects have broader theoretical concerns or are offshoots, of earlier research studies. Whatever the situation, this type of background information, in summary form, belongs in the overview section.

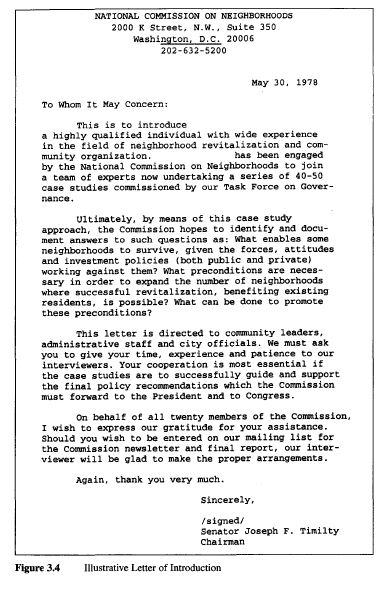

A procedural element of this background section is a statement about the project which you can present to anyone who may want to know about the project, its purpose, and the people involved in conducting and sponsoring the project. This statement can even be accompanied by a letter of introduction, to be sent to all major interviewees and organizations that may be the subject of study. (See Figure 3.4 for an illustrative letter.) The bulk of the overview, however, should be devoted to the substantive issues being investigated. This may include the rationale for selecting the case(s), the propositions or hypotheses being examined, and the broader theoretical or policy relevance of the inquiry. For all of these topics, relevant readings should be cited, and the essential reading materials should be made available to everyone on the case study team.

A good overview will communicate to the informed reader (that is, someone familiar with the general topic of inquiry) the case study’s purpose and setting. Some of the materials (such as a summary describing the project) may be needed for other purposes anyway, so that writing the overview should be seen as a doubly worthwhile activity. In the same vein, a well-conceived overview even may later form the basis for the background and introduction to the final case study report.

2. Field Procedures

Chapter 1 has previously defined case studies as studies of events within their real-life context. This has important implications for defining and designing the case study, which have been discussed in Chapters 1 and 2.

For data collection, however, this characteristic of case studies also raises an important issue, for which properly designed field procedures are essential. You will be collecting data from people and institutions in their everyday situations, not within the controlled confines of a laboratory, the sanctity of a library, or the structured limitations of a survey questionnaire. In a case study, you must therefore learn to integrate real-world events with the needs of the data collection plan. In this sense, you do not have the control over the data collection environment as others might have in using the other research methods discussed in Chapter 1.

Note that in a laboratory experiment, human “subjects” are solicited to enter into the laboratory—an environment controlled nearly entirely by the research investigator. The subject, within ethical and physical constraints, must follow the investigator’s instructions, which carefully prescribe the desired behavior. Similarly, the human “respondent” to a survey questionnaire cannot deviate from the agenda set by the questions. Therefore, the respondent’s behavior also is constrained by the ground rules of the investigator. Naturally, the subject or respondent who does not wish to follow the prescribed behaviors may freely drop out of the experiment or survey. Finally, in the historical archive, pertinent documents may not always be available, but the investigator can inspect what exists at his or her own pace and at a time convenient to her or his schedule. In all three situations, the research investigator closely controls the formal data collection activity.

Doing case studies involves an entirely different situation. For interviewing key persons, you must cater to the interviewee’s schedule and availability, not your own. The nature of the interview is much more open-ended, and an interviewee may not necessarily cooperate fully in sticking to your line of questions. Similarly, in making observations of real-life activities, you are intruding into the world of the subject being studied rather than the reverse; under these conditions, you are the one who may have to make special arrangements, to be able to act as an observer (or even as a participant- observer). As a result, your behavior—and not that of the subject or respondent—is the one likely to be constrained.

This contrasting process of doing data collection leads to the need to have explicit and well-planned field procedures encompassing guidelines for “coping” behaviors. Imagine, for instance, sending a youngster to camp; because you do not know what to expect, the best preparation is to have the resources to be prepared. Case study field procedures should be the same way.

With the preceding orientation in mind, the field procedures of the protocol need to emphasize the major tasks in collecting data, including

- gaining access to key organizations or interviewees;

- having sufficient resources while in the field—including a personal computer, writing instruments, paper, paper clips, and a preestablished, quiet place to write notes privately;

- developing a procedure for calling for assistance and guidance, if needed, from other case study investigators or colleagues;

- making a clear schedule of the data collection activities that are expected to be completed within specified periods of time; and

- providing for unanticipated events, including changes in the availability of interviewees as well as changes in the mood and motivation of the case study investigator.

These are the types of topics that can be included in the field procedures section of the protocol. Depending upon the type of study being done, the specific procedures will vary.

The more operational these procedures are, the better. To take but one minor issue as an example, case study data collection frequently results in the accumulation of numerous documents at the field site. The burden of carrying such bulky documents can be reduced by two procedures. First, the case study team may have had the foresight to bring large, prelabeled envelopes, to mail the documents back to the office rather than carry them. Second, field time may have been set aside for perusing the documents and then going to a local copier facility and copying only the few relevant pages of each document—and then returning the original documents to the informants at the field site. These and other operational details can enhance the overall quality and efficiency of case study data collection.

A final part of this portion of the protocol should carefully describe the procedures for protecting human subjects. First, the protocol should repeat the rationale for the IRB-approved field procedures. Then, the protocol should include the “scripted” words or instructions for the team to use in obtaining informed consent or otherwise informing case study interviewees and other participants of the risks and conditions associated with the research.

3. Case Study Questions

The heart of the protocol is a set of substantive questions reflecting your actual line of inquiry. Some people may consider this part of the protocol to be the case study “instrument.” However, two characteristics distinguish case study questions from those in a survey instrument. (Refer back to Figure 3.3 for an illustrative question from a study of a school program; the complete protocol included dozens of such questions.)

General orientation of questions. First, the questions are posed to you, the investigator, not to an interviewee. In this sense, the protocol is directed at an entirely different party than a survey instrument. The protocol’s questions, in essence, are your reminders regarding the information that needs to be collected, and why. In some instances, the specific questions also may serve as prompts in asking questions during a case study interview. However, the main purpose of the protocol’s questions is to keep the investigator on track as data collection proceeds.

Each question should be accompanied by a list of likely sources of evidence. Such sources may include the names of individual interviewees, documents, or observations. This crosswalk between the questions of interest and the likely sources of evidence is extremely helpful in collecting case study data. Before arriving on the case study scene, for instance, a case study investigator can quickly review the major questions that the data collection should cover.

(Again, these questions form the structure of the inquiry and are not intended as the literal questions to be asked of any given interviewee.)

Levels of questions. Second, the questions in the case study protocol should distinguish clearly among different types or levels of questions. The potentially relevant questions can, remarkably, occur at any of five levels:

Level 1: questions asked of specific interviewees;

Level 2: questions asked of the individual case (these are the questions in the case study protocol to be answered by the investigator during a single case, even when the single case is part of a larger, multiple-case study);

Level 3: questions asked of the pattern of findings across multiple cases;

Level 4: questions asked of an entire study—for example, calling on information beyond the case study evidence and including other literature or published data that may have been reviewed; and

Level 5: normative questions about policy recommendations and conclusions, going beyond the narrow scope of the study.

Of these five levels, you should concentrate heavily on Level 2 for the case study protocol.

The difference between Level 1 and Level 2 questions is highly significant. The two types of questions are most commonly confused because investigators think that their questions of inquiry (Level 2) are synonymous with the specific questions they will ask in the field (Level 1). To disentangle these two levels in your own mind, think again about a detective, especially a wily one. The detective has in mind what the course of events in a crime might have been (Level 2), but the actual questions posed to any witness or suspect (Level 1) do not necessarily betray the detective’s thinking. The verbal line of inquiry is different from the mental line of inquiry, and this is the difference between Level 1 and Level 2 questions. For the case study protocol, explicitly articulating the Level 2 questions is therefore of much greater importance than any attempt to identify the Level 1 questions.

In the field, keeping in mind the Level 2 questions while simultaneously articulating Level 1 questions in conversing with an interviewee is not easy. In a like manner, you can lose sight of your Level 2 questions when examining a detailed document that will become part of the case study evidence (the common revelation occurs when you ask yourself, “Why am I reading this document?”). To overcome these problems, successful participation in the earlier seminar training helps. Remember that being a “senior” investigator means maintaining a working knowledge of the entire case study inquiry. The (Level 2) questions in the case study protocol embody this inquiry.

The other levels also should be understood clearly. A cross-case question, for instance (Level 3), may be whether the larger school districts among your cases are more responsive than smaller school districts or whether complex bureaucratic structures make the larger districts more cumbersome and less responsive. However, this Level 3 question should not be part of the protocol for collecting data from the single case, because the single case only can address the responsiveness of a single school district. The Level 3 question cannot be addressed until the data from all the single cases (in a multiple-case study) are examined. Thus, only the multiple-case analysis can cover Level 3 questions. Similarly, the questions at Levels 4 and 5 also go well beyond any individual case study, and you should note this limitation if you include such questions in the case study protocol. Remember: The protocol is for the data collection from a single case (even when part of a multiple-case study) and is not intended to serve the entire project.

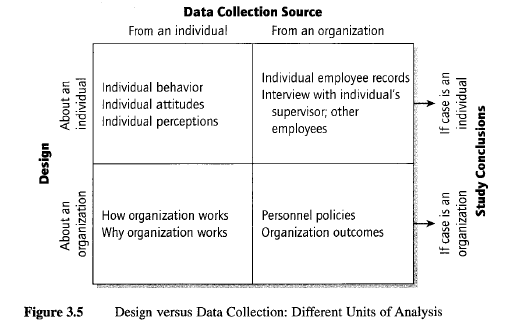

Undesired confusion between unit of data collection and unit of analysis. Related to the distinction between Level 1 and Level 2 questions, a more subtle and serious problem can arise in articulating the questions in the case study protocol. The questions should cater to the unit of analysis of the case study, which may be at a different level from the unit of data collection of the case study. Confusion will occur if, under these circumstances, the data collection process leads to an (undesirable) distortion of the unit of analysis.

The common confusion begins because the data collection sources may be individual people (e.g., interviews with individuals), whereas the unit of analysis of your case study may be a collective (e.g., the organization to which the individual belongs)—a frequent design when the case study is about an organization, community, or social group. Even though your data collection may have to rely heavily on information from individual interviewees, your conclusions cannot be based entirely on interviews as a source of information (you would then have collected information about individuals’ reports about the organization, not necessarily about organizational events as they actually had occurred). In this example, the protocol questions therefore need to be about the organization, not the individual.