- Navigate to any page of this site.

- In the menu, scroll to Add to Home Screen and tap it.

- In the menu, scroll past any icons and tap Add to Home Screen .

The Religion and Family Connection

Social science perspectives, darwin l. thomas , editor, the influence of three agents of religious socialization: family, church, and peers, marie cornwall.

Marie Cornwall, “The Influence of Three Agents of Religious Socialization: Family, Church, and Peers,” in The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives , ed. Darwin L. Thomas (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 207–31.

Marie Cornwall was an assistant professor of sociology at Brigham Young University when this was published. For several years she was the project director for the Religious Activity Project sponsored by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Her published research has focused on how to measure religiosity, the processes of religious disaffiliation, and the role of personal communities in maintaining religious commitment. She received her PhD from the University of Minnesota.

Introduction

How is it that people come to believe, feel, and behave religiously? Social scientists have addressed this question in a number of ways, but the most fruitful research focuses on religious socialization. Of particular interest is not only why people are religious, but why they are religious in the way they are. Sociologists have predicted the decline of religion for the past one hundred years, but it is now clear that religion has not lost its importance in modern society. A new focus in the research, therefore, is to understand how society maintains religion and how religion is transferred to the next generation. Religious institutions no longer operate as monopolies. The modern pluralistic world offers a multitude of religious perspectives from which individuals may choose. What are the processes by which people come to adopt a particular religious identity?

This paper studies the impact of religious socialization on the religiosity of adults. Three agents of religious socialization are examined: parents, the church, and peers. After reviewing the research which demonstrates the importance of these three agents, elements of the socialization process are outlined and a model to test the interrelatedness of these elements is presented. The paper concludes with a discussion of three processes of religious socialization.

Much of the literature examining the influence of religious socialization has been based on data collected from adolescent respondents (Johnson, 1973; Thomas et al., 1974; Albrecht et al., 1977; Aacock and Bengston, 1978; Hoge and Petrillo, 1978). These studies, and other research which has examined the antecedents of adult religiosity (Himmelfarb, 1977, 1979; Greeley and Rossi, 1966; Greeley, 1976), suggest the importance of three agents of religious socialization: (1) parental religiosity and family religious observances, (2) the religiosity of one’s peers—particularly the religiosity of one’s spouse in studies utilizing adult samples, and (3) exposure to church socialization, most notably religious education.

One limitation in much of this research has been a focus on the relative influence of parents, the church, and peers in the socialization process. Greeley, for example, looked at the impact of a parochial school education on the religiosity of Catholics. He and Rossi (Greeley and Rossi, 1966) concluded that religious training in the home had a greater influence on the religious development of children than did a parochial school education. Other research among Jews (Himmelfarb, 1977) and Lutherans 0ohnstone, 1966) supported these finding. Having underscored the relative importance of the family, and the relative unimportance of church and peer socialization, researchers have neglected to ask the next question. How are family, church, and peer socialization processes interrelated? For example, how do family processes influence friendship choices and church attendance? While Greeley originally concluded a parochial school education by itself did not have a substantial influence on adult religiosity, in more recent research he has found a parochial education does have an important influence on adult religiosity by helping integrate the individual into the Catholic community (Fee, Greeley, McCready, and Sullivan, 1981). An understanding of the influence of family, church, and peer socialization requires a more careful examination of how these factors influence one another as well as how they influence adult religiosity. Himmelfarb (1979) has made a significant step towards this kind of understanding in his study of religious socialization based on data collected from a random sample of Jews in Chicago. He suggests that “parents socialize their children by channelling them into other groups or experiences (such as schools and marriage) which will reinforce (have an additive influence on) what was learned at home and will channel them further into similar adult activities” (Himmelfarb, 1979: 478).

In a test of his theory, he found that while parental religiosity was not the best predictor of any of the types of adult religious involvement used in the model, its indirect effect through other agents of religious socialization was very substantial. There was a direct positive influence of parents’ observance of ritual on (1) hours of Jewish schooling, (2) Jewish organizational participation, and (3) spouse’s ritual observance at marriage. Each of these variables had a strong positive effect on adult religious involvement. Himmelfarb concluded parents are influential because they channel their children into experiences and environments which support the socialization received at home.

Theoretical perspectives on the importance of religious socialization generally have focused on the importance of “social learning” and the construction of a religious worldview. For example, Yinger has noted that religiosity, particularly church participation, is a learned behavior. “One learns his religion from those around him Fundamentalist parents tend to bring up children who share the fundamentalist tradition; liberal religious views are found most often among those who have been trained to such views.” (1970: 131.)

A sociology of knowledge perspective suggests the importance of socialization processes in the development of a religious worldview. Individuals come to adopt a particular worldview through early childhood religious socialization or as an adult by switching worlds through re-socialization. The world is built up in the consciousness of the individual by conversation with significant others: parents, peers, and teachers. The subjective reality of the world is maintained by this same conversation. “If such conversation is disrupted (the spouse dies, the friends disappear, or one comes to leave one’s original social milieu), the world begins to totter, to lose its subjective plausibility The subjective reality of the world hangs on the thin thread of conversation.” (Berger, 1967: 17.)

Berger also introduces the concept of “plausibility structures” such as the nuclear and extended family, friendship networks, or churches and other voluntary organizations which socialize individuals into a particular worldview and help them maintain their subjective reality. While Berger suggests that the nuclear family is a tenuous plausibility structure, Lenski (1963) suggests that the family is the core of vital subcommunities which sustain religious commitment in the modern world. Lenski, in fact, argues that religious institutions are highly dependent upon subcommunities of individuals who effectively socialize and indoctrinate group members.

An adequate study of the processes of religious socialization should incorporate each of the elements discussed above. This requires careful attention to:

1. The impact of family, church, and peer socialization on adult religiosity as well as the interrelatedness of these three agents.

2. Channelling processes by which parents and other family members encourage participation in experiences and environments which support the socialization received at home.

3. The role of the family in providing a religious worldview.

4. The role of the family in modelling religious behaviors.

Methodology

<3>Sample.

Respondents were randomly selected from complete membership lists from twenty-seven different Mormon wards (congregations) from all parts of the United States. These twenty-seven wards had previously been chosen from a larger sample of Mormon stakes (typically made up of from six to twelve wards) which had been selected randomly from the different administrative areas of the church in the United States.

A membership roster was obtained from each of the ward units used in the sample and a list of households was randomly selected from each roster. Using this procedure, a total of thirty-two active and forty-eight inactive families was obtained within each of the twenty-seven units. Level of religious participation was previously obtained from the local bishop. Inactive households were oversampled because pretest data indicated they would be less likely to respond to the study than would active families. One adult member in each household was designated for inclusion in the sample by a toss of a die. Adult children over the age of eighteen were included in the sampling universe. When only one adult lived in the household or when there was only one adult who was a member of the LDS church, that person was included in the sample. The final sample consisted of 1,874 members over the age of eighteen.

A thirty-two-page questionnaire with appropriate cover letters requesting participation in what was described as one of the most important studies of Mormon religiosity ever undertaken was mailed to all adults in the sample. Follow-up postcards and additional copies of the questionnaire were mailed to nonrespondents over the next eight-week period. Adjusting for the 576 questionnaires that were undeliverable, the response rate was 74 percent from active members and 48 percent from less active members. The overall response rate was 64 percent. Despite the efforts taken to get accurate membership rosters, church records for those who are not currently attending religious services were found to be seriously inaccurate. Consequently, the majority of the undeliverable questionnaires were returned from less active members. The sample is representative of Mormons who could be located using information available from current church records. Respondents, therefore, probably have more positive feelings towards the LDS church and may be more religious than the general population.

Only the respondents baptized before age nineteen are included in this analysis. About one-third of the respondents are adult converts and the amount of family religious socialization reported by them is much lower than that reported by lifelong members. These adult converts were not socialized in their youth by family, peers, and the religious institution but acquired their belief and commitment through socialization experienced in the conversion process.

While the majority of lifelong members are baptized at age eight, about 10 percent of the lifelong members in the sample were baptized in their teenage years. Because they were exposed to some degree of church and peer socialization during their teenage years, we felt it appropriate to include them in the analysis. A total of 570 respondents in the sample had been baptized before age nineteen. Table 1 presents a description of the sample according to age, education, marital status and gender. In the sample 43 percent of the respondents were weekly attenders; 39 percent reported they seldom or never attend.

Table 1. Demographic profile of respondents (Respondents baptized before age 19 only)

Measurement

Family socialization. The amount of religious socialization in the family was measured by three variables. Respondents were asked to indicate the religious preference of their parents when the respondents were age twelve to eighteen. FAMILY is a dummy variable coded one if both parents were present in the home and both were members of the LDS church and zero if one or both parents were not LDS or if one parent was not present in the home. FAMILY is an indicator of whether or not respondents came from a complete LDS family.

Respondents also reported the frequency of their parents’ church attendance. PCHURCH is the average frequency of church attendance for both parents when the respondent was age twelve to eighteen. If only one parent was present in the home, PCHURCH is the frequency of that parent’s church attendance.

YHRO is a measure of the amount of religious observance respondents experienced in the home during their teenage years. The scale is composed of four items measuring frequency of family prayer, family religious discussions, family Bible or scripture reading, and family discussions of right and wrong. Home religious observance is stressed by LDS church leaders, and, furthermore, parents are strongly encouraged to take an active role in the religious development of their children.

Church socialization. The amount of socialization received through church participation was measured by two variables: YATTEND, a measure of the frequency of attendance at religious services during the teenage years, and SEMINARY. Seminary is a program of religious study offered to LDS students in the ninth through twelfth grades. In most areas of the United States students attend early-morning seminary prior to attending regular school. In Utah students are allowed “released time” from their regular studies to take a seminary course during the day. Response categories were (1) never attended (2) attended occasionally, (3) completed one to two years, and (4) completed three to four years. Because seminary has not always been available in all parts of the country, we expected, and found, a moderate age effect for attendance at seminary (correlation of -.30). Younger respondents were more likely to report having attended. Because of this age effect, the analysis is based on a covariance matrix of residuals after controlling for age.

Peer socialization. Two measures of peer socialization were used: FRIENDS and DECLINE. Respondents were asked to indicate how many of their friends were active members of the LDS church during their teenage and young adult years. Response categories included (1) none of them (2) a few of them (3) about half of them (4) most of them and (5) all of them. FRIENDS is a measure of the proportion of one’s friends who were active LDS during the teenage years, and DECLINE is a measure of the amount of decline in proportion of active LDS friends between the teenage and young adult years. DECLINE was computed by subtracting the proportion of active friends who were LDS during the young adult years (nineteen to twenty-five) from the proportion of active friends who were LDS during the teenage years.

Dimensions of religiosity. Four measures of religious belief and commitment are used in the analysis: two scales measuring a more personal mode of religiosity and two scales measuring the institutional mode of religiosity (for a full discussion of the dimensions of religiosity, see Cornwall, et al., 1986).

1. Traditional orthodoxy is defined as belief in traditional Christian doctrines such as the existence of God, the divinity of Christ, life after death, Satan, and the Bible. These are beliefs that are not unique to Mormonism. Acceptance or rejection of such beliefs is largely independent of affiliation with a particular religious group or institution. Traditional orthodoxy was measured with a five-item scale (see Table 2).

2. Spiritual commitment was measured using a five-item scale which focuses on degree of commitment to God. Items tap feelings such as loving God with all one’s heart, willingness to do whatever the Lord wants, and the importance of one’s relationship with God.

3. Particularistic orthodoxy refers to the acceptance or rejection of beliefs peculiar to a particular religious organization. Particularistic orthodoxy includes acceptance of such doctrines as the prophetic calling of Joseph Smith and the current church president, the authenticity of the Book of Mormon, and adherence to the belief that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the only true church on earth. Four items were used to measure particularistic orthodoxy.

4. Church commitment is the affective orientation of the individual towards the religious organization or community. It measures the attachment, identification, and loyalty of the individual towards the church organization or religious community. Five items were used to measure church commitment.

Table 2. Varimax Factor Pattern of Religiosity Items

Table 2 presents the results of a factor analysis of the several items which were combined into four separate religiosity scales. A factor analysis of these items produced three factors. All the spiritual commitment items load on the first factor with two items from the traditional orthodoxy scale. The particularistic orthodoxy items and the church commitment items load on the second factor. The particularistic orthodoxy items and the traditional belief items load on the third factor. When only the traditional orthodoxy items and the particularistic orthodoxy items are entered into a factor analysis, two distinct factors emerge. The traditional items load on one factor and the particularistic items load on the other. In addition, when other religiosity measures are included in the factor analysis (such as church attendance, frequency of personal prayer, and frequency of home religious observance), the overlap between church commitment and particularistic orthodoxy factors disappears. For this reason, four separate religiosity scales will be used as measures of religiosity.

Two levels of statistical analysis are reported in this paper. First, zero-order correlations among the several variables are examined, and then, in order to examine the complex interrelationships among variables, a path model is developed and tested. It is always useful to examine the zero-order correlations [1] between two variables to get an initial estimate of the amount of association between them. However, measures of association are not always indicators of a causal relationship. For example, the amount of association between two variables may actually be due to their correlation with a third variable. Or sometimes the amount of association between two variables is masked by the effects of another variable. The primary question to be addressed in the following statistical analysis is the interrelatedness of the family, peer and church socialization variables as well as their impact on adult religiosity.

Table 3 presents a correlation matrix of the religious socialization variables with the four measures of religious belief and commitment. The correlations between the family socialization variables (FAMILY, PCHURCH, and YHRO) and the four religious belief and commitment scales are not very large, ranging from a high of. 19 (SPIRIT and YHRO) to a low of .04 (SPIRIT and FAMILY). Compared with other family variables, correlations between YHRO and the four adult religiosity measures are relatively strong, ranging between .14 and .17, although all three family socialization variables have an impact on particularistic belief. The correlation matrix also reveals LDS family completeness and parental church activity have a greater influence on institutional religiosity (PARTIC and CHURCH) than on personal religiosity (TRAD and SPIRIT).

Table 3. Correlation Matrix of Religious Socialization Variables and Religious Belief and Commitment, Lifelong Members Only, Controlling for Age

GENDER (0=female; 1=male) FAMILY, family complete LDS (0=single parent or one parent not LDS; 1=both parents present and both LDS) PCHURCH, frequency of parents' church attendance YHRO, frequency of home religious observance: frequency of family prayer, family religious discussions, scripture reading, and family discussions about right and wrong YATTEND, church attendance of respondents when age 12-18 SEMINARY, years attendance at seminary FRIENDS, proportion of friends who wer active LDS when respondent was age 12-18 DECLINE, decline in proportion of friends active LDS between teenage years and adult years TRAD, traditional orthodoxy SPIRIT, spiritual commitment PARTIC, particularistic orthodoxy CHURCH, church commitment *p>.05

Church socialization variables and measures of adult religiosity are also moderately correlated. SEMINARY is correlated .22 and .15 with church commitment and particularistic orthodoxy and .05 and .09 with spiritual commitment and traditional orthodoxy. The same pattern holds for the correlation between YATTEND and religious belief and commitment, although the differences are not as great. The greater the amount of church socialization, the greater the level of institutional belief and commitment. Church socialization does not have as great an impact on personal belief and commitment.

A similar pattern is found when we examine the relationship between the proportion of active LDS friends (FRIENDS) and religiosity: low, nonsignificant correlations with personal religiosity (.06 and .03), and moderate correlations with institutional religiosity (.21 and .15).

Family socialization variables are highly correlated with both the peer socialization and the church socialization variables. The correlation between FAMILY and SEMINARY is .40 and the correlation between FAMILY and FRIENDS is .45. The size of the correlations between PCHURCH and YHRO and both FRIENDS and SEMINARY is also moderately strong.

The size of correlations between the four measures of belief and commitment and the amount of decline in proportion of active LDS friends is larger than any other coefficients in the table. The religiosity measures are more highly correlated with DECLINE than any other variable in the model, suggesting that peer socialization during the young adult years has a significant impact on both personal and institutional modes of religiosity.

An effect for sex is also apparent in Table 3. (The negative coefficient indicates that men report lower levels). Women report higher levels of home religious observance, greater frequency of attendance at religious services, a greater proportion of active LDS friends during the teenage years, and more decline in active LDS friends from the teenage years to young adulthood. Furthermore, they also report higher levels of adult religious belief and commitment. While the effect of gender on frequency of attendance at religious services, active LDS friends, and adult religiosity is not surprising, one might question the theoretical link between gender and the amount of home religious observance reported in the teenage years. Two explanations for this are possible. First, response bias may account for the slight correlation. Women report higher levels of religiosity and recall greater religious activity in their homes during the teenage years. However, another explanation is just as compelling. It may mean that women experience more home religious observance in their youth than men. Much of the responsibility for initiating home religious observance may fall upon women, and perhaps the young women themselves act as an important catalyst for encouraging parents and siblings to have family prayer, scripture reading, and the like.

At this point, the analysis suggests family socialization variables have less impact than church and peer socialization variables. However, because the family, church, and peer socialization variables are highly correlated, further analysis must be done to isolate the impact of each of the variables and to examine their interrelatedness.

LISREL (Joreskog and Sorbom, 1984) is a computer program which facilitates path modelling while controlling for measurement error. LISREL estimates the unknown coefficients in a set of linear structural equations. The advantages of LISREL over other analysis programs are (1) it provides a chi square measure of fit, (2) it requires specificity of assumptions about measurement error, and (3) it handles reciprocal causation or interdependence among the variables in the model. It also allows for the introduction of latent, unobserv-able variables.

LISREL was used for this analysis because it enables us to control for the effect of uncorrelated errors. Recall data is often suspect, and the introduction of measurement error is particularly likely with respect to data about frequency of parental church attendance and frequency of religious observance in the home. We are able to take into consideration the correlation of error terms between PCHURCH and YHRO by requesting the calculation of the error term.

LISREL also allowed us to specify and account for the interdependence of the YATTEND, FRIENDS, and SEMINARY variables. Interdependence is a problem because it is difficult to know whether attending church during the teenage years influences friendship patterns or whether friendship patterns influence attendance at church. The same is true, of course, for the relationship between FRIENDS and SEMINARY. These relationships are reciprocal. For path modelling purposes, the relationship between FRIENDS and SEMINARY and between YATTEND and FRIENDS is assumed to be reciprocal. However, we assumed the relationship between YATTEND and SEMINARY is monocausal. Those teenagers who attend church on a regular basis are more likely to attend seminary, but attendance at seminary is not as likely to influence attendance at religious services.

The findings presented here are the result of an iterative process. Early model specification was based on both empirical results (correlation matrix and regression analysis) and theoretical insights. In some cases, the T-value (less than 2.05) suggested the path should be dropped from the model. In other cases, the modification index indicated a path should be included. Once the model was fit, both theoretically and empirically, the same model was used to predict the four measures of belief and commitment.

Final model specification assumed a direct effect of six variables on adult religiosity: home religious observance, seminary attendance, proportion of friends who were active LDS during the teenage years, amount of decline in proportion of active LDS friends between the young adult years and the teenage years, frequency of respondent’s church attendance as a youth, and gender.

Each of the three family variables operate differently in the socialization process. Model specification assumed the FAMILY variable would influence parental church activity, proportion of active LDS friends, and seminary attendance. While the correlation matrix also suggested a moderate association between FAMILY and YATTEND, DECLINE, and the religiosity measures, early efforts to fit the model produced nonsignificant t-values for these paths. Theoretically, we would expect LDS family completeness would have the strongest direct effect on frequency of parental church attendance. When both parents are present and both belong to the same church, their level of religious activity is likely to be higher than if parents are of different religions, or only one parent is present. Friendship choices and seminary attendance are also directly affected because of the lack of support in the family for in-group association and church participation.

PCHURCH is correlated with YHRO, YATTEND, SEMINARY, and FRIENDS, but early efforts to fit the model suggested a direct effect of PCHURCH on YHRO and YATTEND only. The influence of family religious socialization on seminary attendance and friendship patterns is felt directly through FAMILY and YHRO, rather than PCHURCH. However, as might be expected, parental religious activity is strongly correlated with amount of religious observance in the home, and with frequency of attendance at church during the teenage years. Teenagers are more likely to attend church if their parents attend with them.

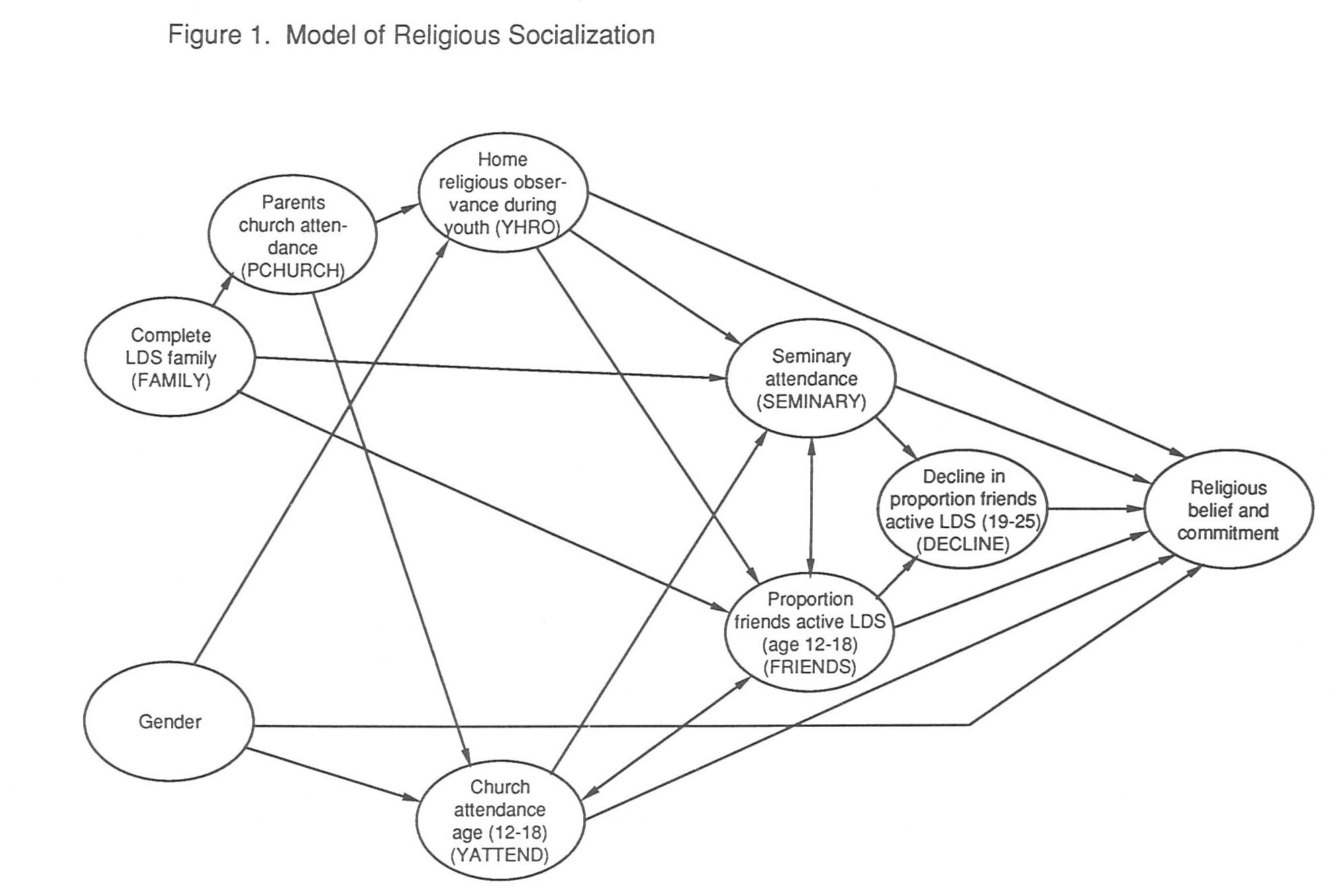

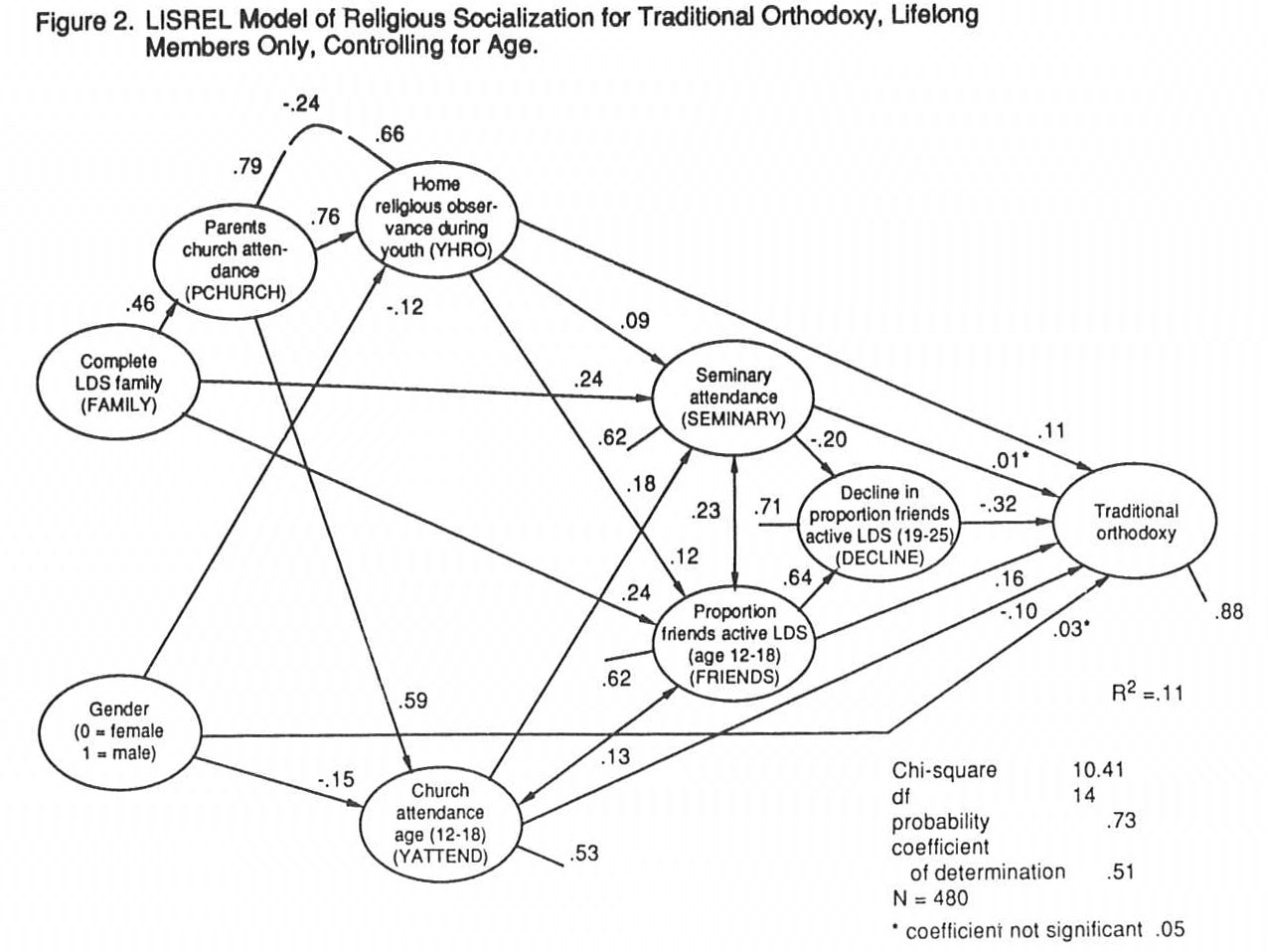

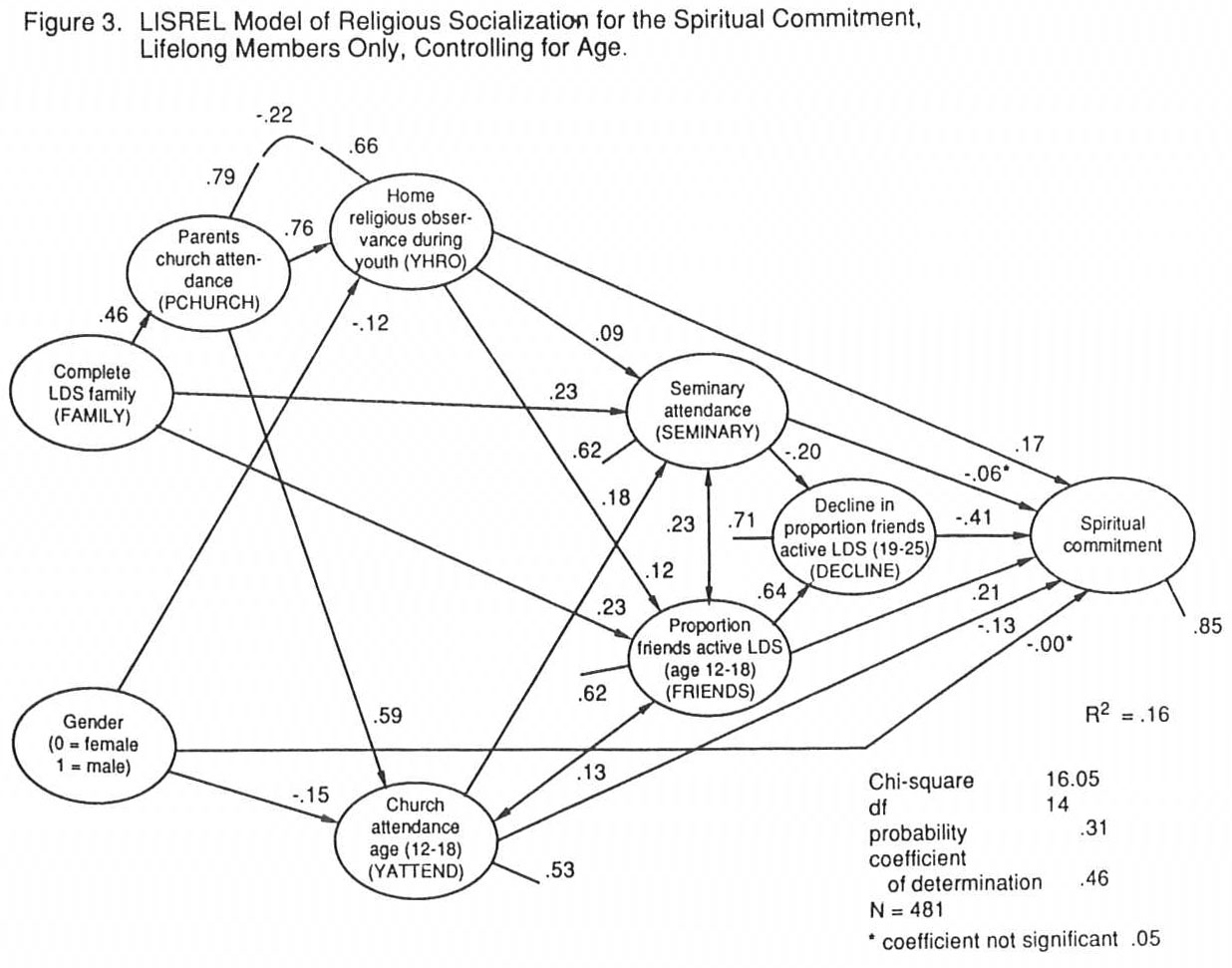

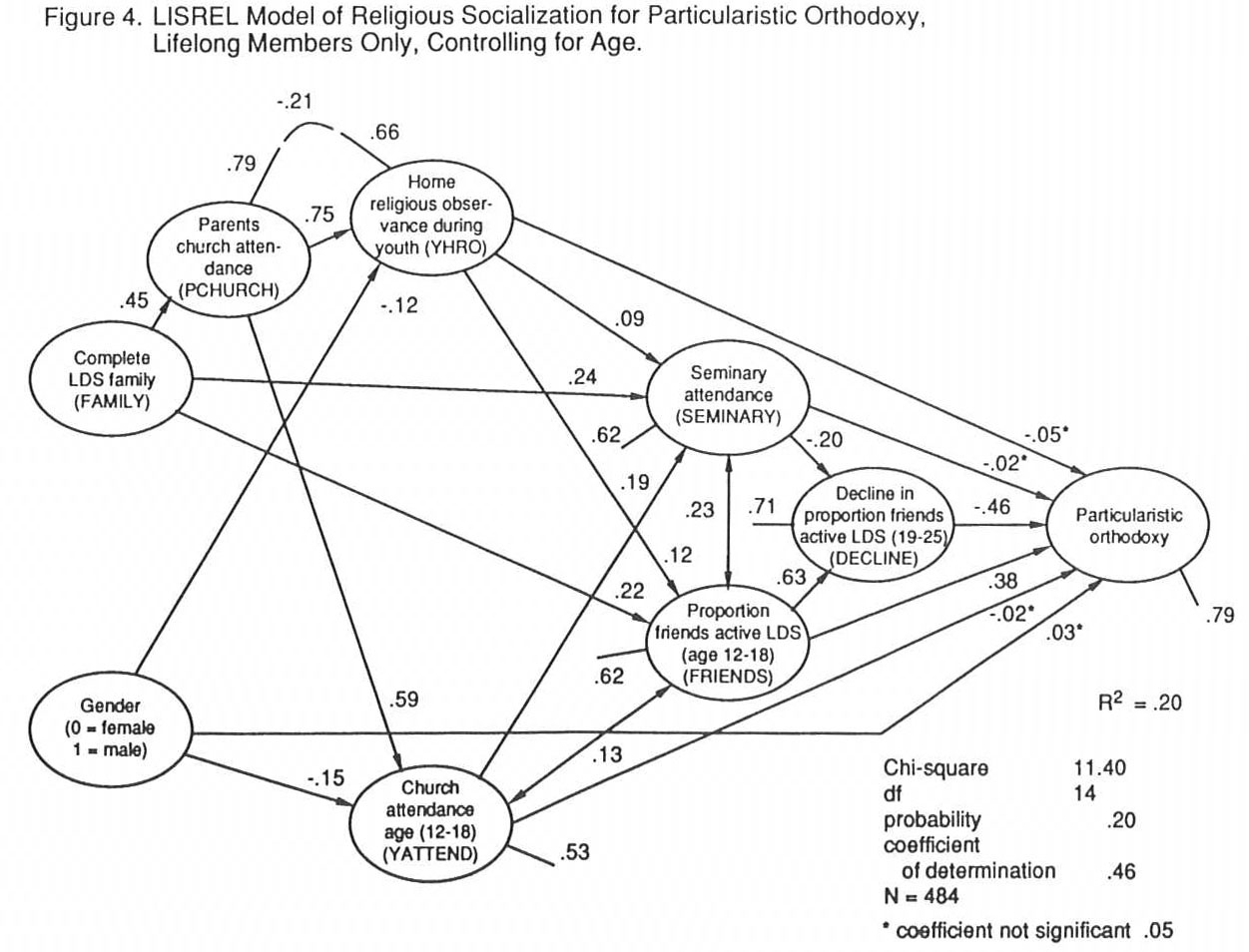

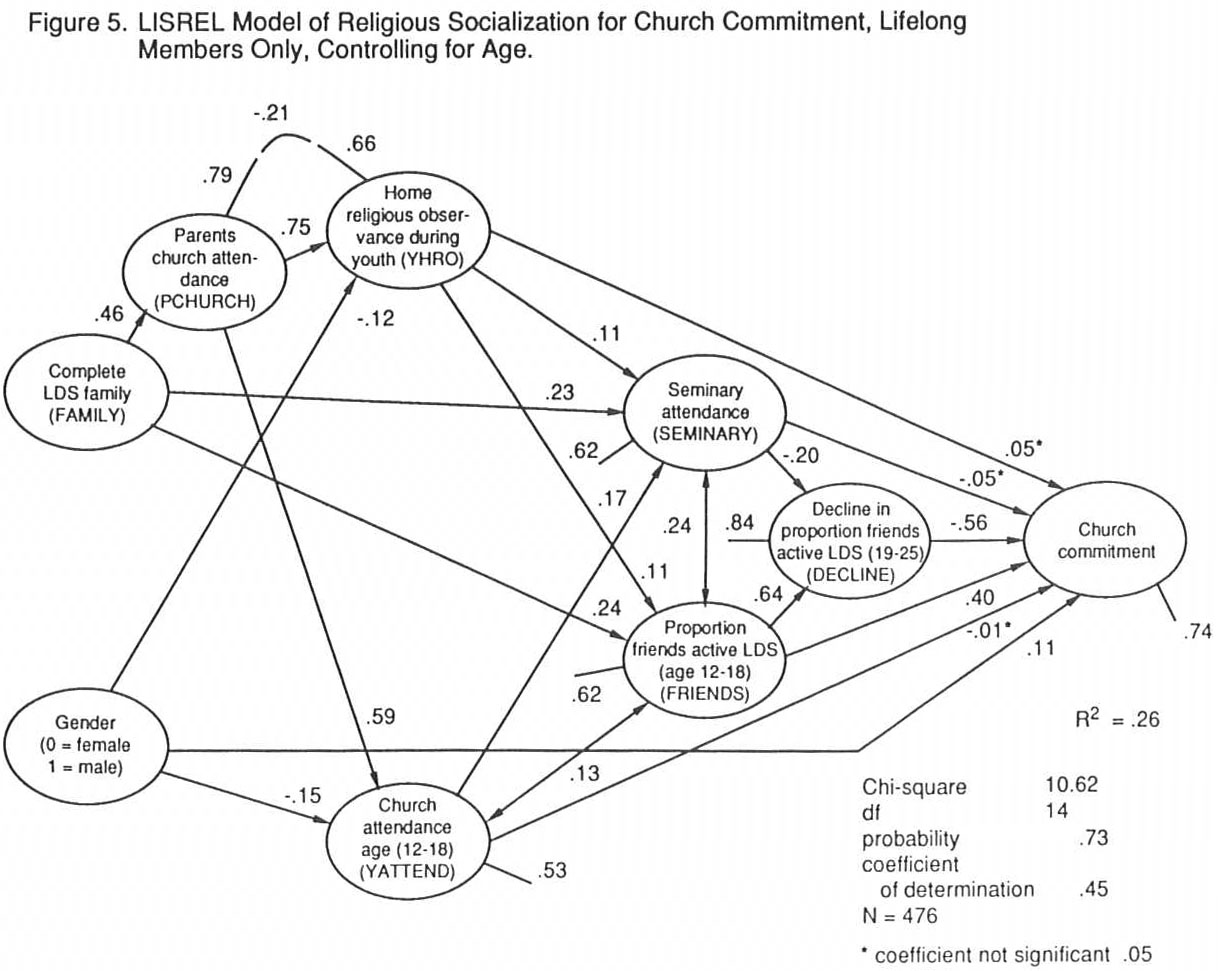

Final model specification is presented in Figure 1. The results of the LISREL analyses are displayed in Figures 2 through 5. The chi-squares for all models ranged between 10 and 16 with 14 degrees of freedom, indicating no significant difference between the model and the data (probability levels between .20 and .73).

The standardized path coefficients [2] presented in Figures 2 through 5 demonstrate the direct and indirect effects of the several variables in the model. Each figure contains essentially the same structural equation model but a different measure of adult religiosity is examined.

Because each model is essentially the same except for the dependent variable, the relationships among the family socialization variables (FAMILY, PCHURCH, and YHRO), the peer socialization variables (FRIENDS, and DECLINE), and the church socialization variables (YATTEND and SEMINARY) are the same across all models. Understanding the processes of religious socialization requires careful examination of the relationships among these variables alone. In the following discussion, the size of relevant path coefficients will be noted within parentheses.

Coming from a complete LDS family increases the likelihood of also having parents who attend church regularly (.46), having active LDS friends during the teenage years (.24), and attending seminary (.24). Frequency of parental church attendance has a strong positive influence on the amount of religious observance in the home (.76) and frequency of attendance at worship services during the teenage years (.59). Home religious observance has a slight positive influence on seminary attendance (.09) and proportion of active LDS friends (.12). Having active LDS friends is associated with both church (.13) and seminary attendance (.23) although the interdependence is greater for seminary attendance than for church attendance. Proportion of active LDS friends also has a strong positive influence on decline in active LDS friends during the young adult years (.64), although the strength of this relationship is due in part to the way DECLINE was calculated. In addition, women report higher levels of home religious observance and more frequent church attendance during their teenage years.

Contrary to earlier findings, frequency of home religious observance does not have the same direct effect on all measures of adult religiosity. The significant direct effect of YHRO on traditional orthodoxy (.11) and spiritual commitment (.17) does not appear in the other two models. Frequency of home religious observance during the teenage years influences personal religiosity, but not institutional religiosity. Further model testing using frequency of personal prayer and attendance at worship services as dependent variables gives additional evidence of the relative importance of home religious observance on the private, more personalized aspects of religion. In the meeting attendance model (not shown), home religious observance does not have a direct effect on frequency of attendance (.04). However, there is a significant direct effect of home religious observance on frequency of personal prayer.

The path from SEMINARY to the outcome variables is not significant in any of the four models. Although seminary attendance does have an impact on adult religiosity, its impact is primarily indirect through its influence on friendship networks. Seminary attendance influences friendship choices in the young adult years (coefficient equals -.20 in all models), and these friendship choices have a notable impact on adult religiosity.

The impact of the DECLINE variable on the four measures of religiosity differs across all models. It is weakest for traditional orthodoxy (-.32) and strongest for church commitment (-.56), but it is the variable which has the strongest direct effect in all four models. The strength of the DECLINE variable in predicting adult religiosity can in part be understood in light of recent research suggesting the importance of the teenage and young adult years in the development of a religious identity (Albrecht, Cornwall, Cunningham, forthcoming). Religious change frequently occurs during these years. Those who drop out or disengage from religious participation do so during the teenage or young adult years.

The impact of proportion of active LDS friends during the teenage years is different for each dimension of adult religiosity. The path coefficient for the FRIENDS variable is almost twice as large for the institutional measures (.38 and .40) as for the personal measures (.16 and .21), suggesting peer relationships have a greater impact on institutional religiosity than on personal religiosity. The significance of such patterns emphasizes the importance of in-group association for institutional religiosity and the relative less importance of such association for personal religiosity.

A direct effect for gender is found in the two personal religiosity models, but gender has no direct influence on institutional religiosity once the effect of other variables is controlled. Women report higher levels of traditional orthodoxy (-.10) and spiritual commitment (-.13), but the coefficients for gender are nonsignificant in the institutional religiosity models.

Attendance at meetings during the teenage years has a stronger influence on institutional commitment than on personal religious commitment. Data analysis reveals a significant direct effect of frequency of attendance during the teenage years on church commitment (.11) only. Further model testing reveals youth church attendance also directly influenced adult attendance (standardized coefficient equals .08).

The R-square for each model differs significantly from a low of .11 for traditional orthodoxy to a high of .26 for church commitment. The R-square for particularistic orthodoxy is .20 and the R-square for spiritual commitment is .16. We are less able to account for the variance in personal religiosity than we are to account for the variance in institutional religiosity, but even so, the overall amount of explained variance using religious socialization variables is less than one-fourth. However, other model testing produced an R-square of .29 for frequency of attendance at worship services.

The amount of variance explained in these models is relatively low. One reason for this may be that we are examining the relationship between religious experiences and socialization during the teenage years with adult religiosity. The low R-square may be an indicator of the many other factors which influence religiosity as the individual becomes an adult. This interpretation is strengthened by the results Himmelfarb (1979) found in his study of American Jews. His analysis of the effect of similar variables on eight different dimensions of religiosity produced an average R-square of .30. He was able to explain slightly more of the variance in his dependent variables by including a measure of spouse religiosity. Even so, an average R-square of .30 suggests the need to identify additional, currently unmeasured factors which also influence adult religiosity.

Conclusions

The primary importance of the family is apparent in this research, although in somewhat unexpected ways. For the most part, the family variables did not directly influence adult religiosity, although they had a significant influence on almost every other variable in the model. When both parents are present and both are LDS, a teenager is more likely to attend seminary and is also more likely to have active LDS friends during the teenage years. When frequency of parental church attendance is high, the teenager attends church more frequently. And when home religious observance is high, teenagers are also more likely to associate with LDS friends. Family religious socialization affects adult religiosity to the extent that it influences intervening variables: church and seminary attendance, and integration into a network of LDS peers.

The family, however, has a particularly important influence on personal religiosity. There was a consistent direct effect of home religious observance for models examining the personal mode of adult religiosity (traditional orthodoxy, spiritual commitment, and frequency of personal prayer), but not for the models examining the institutional mode of religiosity (particularistic orthodoxy, church commitment, and frequency of church attendance). Why is there no direct effect of family socialization variables on institutional religiosity? One explanation is participation in and commitment to the religious group is more heavily dependent upon the degree to which individuals are integrated into that group and has established a pattern of group participation. Thus, peer group associaton has a greater impact on institutional religiosity than on personal religiosity, and family socialization has a greater direct impact on personal religiosity than on institutional religiosity. Family socialization therefore influences the institutional modes of religiosity in adulthood to the extent that it contributes to the development of friendship ties with people who are active participators in the same religious group. On the other hand, family socialization influences personal religiosity by providing the foundation for a religious worldview, as well as by channelling people into networks of associations which foster the maintenance of that worldview.

Church and peer socialization have a significant impact on adult religiosity as well. Consistent with Himmelfarb’s conclusions, these data suggest parents channel their children into religious activities and religious networks which reinforce what is learned at home and encourage continued participation in adult activities which sustain belief and commitment. However, church and peer socialization also channel individuals. Seminary attendance acts as an important mechanism for increased integration within an LDS network and sustains integration through the young adult years and into adulthood.

The Processes of Religious Development

Extrapolating from these findings, we can begin to identify the processes by which individuals acquire a religious identity. Parents influence the development of a religious identity by supplying their children with a symbolic reference for understanding and interpreting a religious life, by modelling religious behavior on both the personal and institutional levels, and by encouraging the integration of their children into networks of relationships with others who share the same beliefs and the same group identity.

Symbolic references and the construction of religious meaning. Every person must develop a worldview or meaning system by which he or she can understand and interpret life experiences. Sociologists refer to this process as the social construction of reality because reality construction is highly dependent upon the symbolic references provided by others: parents, siblings, friends, and associates (Geertz, 1966). For the most part, these symbolic references take the form of “stories” (Greeley, 1982; Fowler, 1984) or “conversations” (Berger, 1967). Within these stories are images which represent, resonate, and articulate religious experience. The child, according to Greeley, “more explicitly and more self-consciously than the rest of us wants a story that will clarify reality for him” (1982: 57). Fairy tales and folktales, Bible stories and family stories are all equally true within the mind of the young child seeking to understand the world and how it works. Within the family, the individual begins to create his own religious worldview. The foundations upon which this worldview rests are created out of the family environment and the more religiously oriented the family, the more central religion will be within the child’s personal construction of reality.

Modelling religious behavior. Along with the construction of a religious worldview, the individual must also learn the norms and expectations of the religious group. The exact parameters of these expectations (for example, daily prayers, tithe paying, daily scripture reading) are defined by the particular religious group to which he or she belongs and become a part of the religious worldview during the socialization process. A young child learns what these expectations are by listening to stories and conversations told to them by their peers and by adults. In addition, however, children also learn about the norms and expectations of the religious group from parents and others whose own religious behavior provides the child with additional information about the practical application of religious norms and the contexts in which they are most appropriate. The extent to which these norms and expectations become an integral part of the beliefs and behaviors of a group member is therefore dependent upon both the development of a worldview that incorporates a belief in the norms and expectations of the group and the extent to which he or she has had opportunities to observe the practical application of those expectations.

Channelling. As with any type of social group, religious groups are particularly concerned with encouraging commitment on the part of its members. The vitality of the group is highly dependent upon the degree to which members are committed to the survival of the organization itself, to other members of the group, and to the norms and expectations of the group (Kanter, 1972). It is generally agreed that commitment is very much a product of the extent to which individuals are integrated into the religious community (Roof, 1978; McGaw, 1980; Cornwall, 1985; 1987). For example, the role of friendship ties and social networks in the conversion process has been demonstrated in the literature (Lofland and Stark, 1965; Lofland, 1977), and social scientists are beginning to assert that affective commitment develops prior to full acceptance of the belief system.

This, and other research on the channelling effect of parents (Himmelfarb, 1979), and the church (Fee et al., 1981) not only confirms the importance of social ties in religious development, but also begins to identify how the family and the church influence friendship choices. People are channelled into networks of association at fairly young ages and this channelling continues to be a vital force during the teenage and young adult years.

Implications

Having identified these three salient processes of religious development (symbolic references, modelling, and channelling), we know families have a strong influence on the religious development of individuals and we have a better understanding of why. While more research is needed to understand these processes and how they interact with one another, religious educators and church leaders can begin now to emulate what families have been able to do so well for so many years. We must therefore begin to ask in what ways youth leaders can enhance religious development in children and youth by sharing religious experiences and personal stories, by modelling religious behavior, and by encouraging integration into networks of people who share the same religious faith.

The research reported here is helpful in other ways, as well. The data strongly suggest interfaith marriages and single parent families place the religious development of children at risk. Family completeness affects parental religious activity. It also influences seminary attendance and proportion of active LDS friends during the teenage years, even after controlling for the effect of parental religious activity and home religious observance. It may be that parents in interfaith marriages or single parent families are less integrated into a religious network themselves and are therefore less able to help integrate their children. It may also be that these parents (either intentionally or unintentionally) channel their children into experiences which do not foster identity with one particular religious group. Presented with the option to choose between two groups, they opt for neither one. There is insufficient data available about the effects of interfaith marriages on the religious development of children. But given the increasing numbers of such marriages (Caplow et al., 1983), more research is needed in that area.

Finally, these findings again point to two critical periods of religious development: adolescence and young adulthood. In addition to the physical, social and cognitive changes experienced during the teenage and young adult years, individuals are much more likely to be confronted with alternative worldviews and their attendant life-styles, as well as new friendship choices. It is likely the strength of attachments, the plausibility of parental worldviews, and the practicalities of modelled behaviors play a central role in maintaining a religious identity during this critical period. All of which suggests the need for further examination of the processes of faith development during these critical years.

Bibliography

Aacock, A., and V. Bengston. 1978. “On the Relative Influence of Mothers and Fathers: A Covariance Analysis of Political and Religious Socialization.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 40: 519–30.

Albrecht, S. L., B. Chadwick, and D. Alcorn. 1977. “Religiosity and Deviance: Application of an Attitude-Behavior Consistency Model.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 16: 263–74.

Albrecht, S. L, M. Cornwall, and P. Cunningham. 1988. “Religious Leave-taking: Disengagement and Disaffiliation among Mormons,” in D. G. Bromley (ed.) Falling from the Faith: The Causes, Course, and Consequences of Religious Apostasy, forthcoming.

Berger, P. L. 1967. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Caplow, T., H. M. Bahr, and B. A. Chadwick. 1983. All Faithful People: Change and Continuity in Middletown’s Religion. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Cornwall, M. 1985. “The Normative Bases of Religion: A Study of Factors Influencing Religious Behavior.” Paper presented at the annual meetings of the Association for the Sociology of Religion, Washington, D.C.

Cornwall, M. 1987. “The Social Bases of Religion: A Study of Factors Influencing Religious Belief and Commitment,” Review of Religious Research 29: 44–56.

Cornwall, M., S. L. Albrecht, P. H. Cunningham, and B. L. Pitcher. 1986. “The Dimensions of Religiosity: A Conceptual Model with an Empirical Test.” Review of Religious Research 27: 226–44.

Fee, J. L., A. M. Greeley, W. C. McCready, and T. Sullivan. 1981. Young Catholics in the United States and Canada. New York: Sadlier.

Fowler, J. W. 1984. Becoming Adult, Becoming Christian: Adult Development and Christian Faith. San Francisco: Harper and Row.

Geertz, C. 1966. “Religion as a Cultural System,” in M. Banton (ed.), Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion. London: Tavistock Publications.

Greeley, A. M., and P. Rossi. 1966. The Education of Catholic Americans. Chicago: Aldine.

Greeley, A. M., W. C. McCready, and K. McCourt. 1976. Catholic Schools in a Declining Church. Kansas City, MO: Sheed and Ward.

Greeley, A. M. 1982. Religion: A Secular Theory. New York: Free Press.

Himmelfarb, H. S. 1977. “The Interaction Affects of Parents, Spouse, and Schooling: Comparing the Impact of Jewish and Catholic Schools.” Sociological Quarterly 18: 464–71.

Himmelfarb, H. S. 1979. “Agents of Religious Socialization among American Jews.” Sociological Quarterly 20: 447–94.

Hoge, D., and G. Petrillo. 1978. “Determinants of Church Participation and Attitudes Among High School Youth.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17: 359–79.

Johnson, M. 1973. “Family Life and Religious Commitment.” Review of Religious Research 14: 144–50.

Johnstone, R. L. 1966. The Effectiveness of Lutheran Elementary and Secondary Schools as Agencies of Christian Education. St. Louis: Concordia Seminary.

Kanter, R. M. 1972. Commitment and Community. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lenski, G. 1963. The Religious Factor. Garden City: Doubleday.

Lofland, J., and R. Stark. 1965. “Becoming a World-Saver: A Theory of Religious Conversion.” American Sociological Review 30: 862–74.

Lofland, J. 1977. Doomsday Cult. New York: Irvington Publishers.

McGaw, D. B. 1980. “Meaning and Belonging in a Charismatic Congregation: An Investigation into Sources of Neo-Pentecostal Success.” Review of Religious Research (Summer): 284–301.

Roof, W. C. 1978. Community and Commitment: Religious Plausibility in a Liberal Protestant Church. New York: Elsevier.

Thomas, D., V. Gecas, A. Weigert and E. Rooney. 1974. Family Socialization and the Adolescent. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

Yinger, M. J. 1970. The Scientific Study of Religion. New York: Macmillan.

[1] Zero-order correlations measure the amount and direction of association between two variables. The larger the correlation, the greater the amount of association. Correlations vary from -1.00 to +1.00. However, in social science research of this type a correlation greater than .40 is considered a relatively strong association.

[2] Path coefficients are measures of the amount of association between two variables controlling for the effect of all other variables in the model. The coefficient represents the amount of change in the independent variable which is associated with one standardized unit of change in the dependent variable.

Contact the RSC

185 Heber J. Grant Building Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 801-422-6975

Helpful Links

Religious Education

BYU Studies

Maxwell Institute

Articulos en español

Artigos em português

Connect with Us

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

5.3 Agents of Socialization

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Evaluate the roles of families and peer groups in socialization

- Describe how people are socialized through institutions like schools, workplaces, and the government

Socialization helps people learn to function successfully in their social worlds. How does the process of socialization occur? How do we learn to use the objects of our society’s material culture? How do we come to adopt the beliefs, values, and norms that represent its nonmaterial culture? This learning takes place through interaction with various agents of socialization, like peer groups and families, plus both formal and informal social institutions.

Social Group Agents

Social groups often provide the first experiences of socialization. Families, and later peer groups, communicate expectations and reinforce norms. People first learn to use the tangible objects of material culture in these settings, as well as being introduced to the beliefs and values of society.

Family is the first agent of socialization. Mothers and fathers, siblings and grandparents, plus members of an extended family, all teach a child what he or she needs to know. For example, they show the child how to use objects (such as clothes, computers, eating utensils, books, bikes); how to relate to others (some as “family,” others as “friends,” still others as “strangers” or “teachers” or “neighbors”); and how the world works (what is “real” and what is “imagined”). As you are aware, either from your own experience as a child or from your role in helping to raise one, socialization includes teaching and learning about an unending array of objects and ideas.

Keep in mind, however, that families do not socialize children in a vacuum. Many social factors affect the way a family raises its children. For example, we can use sociological imagination to recognize that individual behaviors are affected by the historical period in which they take place. Sixty years ago, it would not have been considered especially strict for a father to hit his son with a wooden spoon or a belt if he misbehaved, but today that same action might be considered child abuse.

Sociologists recognize that race, social class, religion, and other societal factors play an important role in socialization. For example, poor families usually emphasize obedience and conformity when raising their children, while wealthy families emphasize judgment and creativity (National Opinion Research Center 2008). This may occur because working-class parents have less education and more repetitive-task jobs for which it is helpful to be able to follow rules and conform. Wealthy parents tend to have better educations and often work in managerial positions or careers that require creative problem solving, so they teach their children behaviors that are beneficial in these positions. This means children are effectively socialized and raised to take the types of jobs their parents already have, thus reproducing the class system (Kohn 1977). Likewise, children are socialized to abide by gender norms, perceptions of race, and class-related behaviors.

In Sweden, for instance, stay-at-home fathers are an accepted part of the social landscape. A government policy provides subsidized time off work—480 days for families with newborns—with the option of the paid leave being shared between mothers and fathers. As one stay-at-home dad says, being home to take care of his baby son “is a real fatherly thing to do. I think that’s very masculine” (Associated Press 2011). Close to 90 percent of Swedish fathers use their paternity leave (about 340,000 dads); on average they take seven weeks per birth (The Economist, 2014). How do U.S. policies—and our society’s expected gender roles—compare? How will Swedish children raised this way be socialized to parental gender norms? How might that be different from parental gender norms in the United States?

Peer Groups

A peer group is made up of people who are similar in age and social status and who share interests. Peer group socialization begins in the earliest years, such as when kids on a playground teach younger children the norms about taking turns, the rules of a game, or how to shoot a basket. As children grow into teenagers, this process continues. Peer groups are important to adolescents in a new way, as they begin to develop an identity separate from their parents and exert independence. Additionally, peer groups provide their own opportunities for socialization since kids usually engage in different types of activities with their peers than they do with their families. Peer groups provide adolescents’ first major socialization experience outside the realm of their families. Interestingly, studies have shown that although friendships rank high in adolescents’ priorities, this is balanced by parental influence.

Institutional Agents

The social institutions of our culture also inform our socialization. Formal institutions—like schools, workplaces, and the government—teach people how to behave in and navigate these systems. Other institutions, like the media, contribute to socialization by inundating us with messages about norms and expectations.

Most U.S. children spend about seven hours a day, 180 days a year, in school, which makes it hard to deny the importance school has on their socialization (U.S. Department of Education 2004). Students are not in school only to study math, reading, science, and other subjects—the manifest function of this system. Schools also serve a latent function in society by socializing children into behaviors like practicing teamwork, following a schedule, and using textbooks.

School and classroom rituals, led by teachers serving as role models and leaders, regularly reinforce what society expects from children. Sociologists describe this aspect of schools as the hidden curriculum , the informal teaching done by schools.

For example, in the United States, schools have built a sense of competition into the way grades are awarded and the way teachers evaluate students (Bowles and Gintis 1976). When children participate in a relay race or a math contest, they learn there are winners and losers in society. When children are required to work together on a project, they practice teamwork with other people in cooperative situations. The hidden curriculum prepares children for the adult world. Children learn how to deal with bureaucracy, rules, expectations, waiting their turn, and sitting still for hours during the day. Schools in different cultures socialize children differently in order to prepare them to function well in those cultures. The latent functions of teamwork and dealing with bureaucracy are features of U.S. culture.

Schools also socialize children by teaching them about citizenship and national pride. In the United States, children are taught to say the Pledge of Allegiance. Most districts require classes about U.S. history and geography. As academic understanding of history evolves, textbooks in the United States have been scrutinized and revised to update attitudes toward other cultures as well as perspectives on historical events; thus, children are socialized to a different national or world history than earlier textbooks may have done. For example, information about the mistreatment of African Americans and Native American Indians more accurately reflects those events than in textbooks of the past.

Big Picture

Controversial textbooks.

On August 13, 2001, twenty South Korean men gathered in Seoul. Each chopped off one of his own fingers because of textbooks. These men took drastic measures to protest eight middle school textbooks approved by Tokyo for use in Japanese middle schools. According to the Korean government (and other East Asian nations), the textbooks glossed over negative events in Japan’s history at the expense of other Asian countries.

In the early 1900s, Japan was one of Asia’s more aggressive nations. For instance, it held Korea as a colony between 1910 and 1945. Today, Koreans argue that the Japanese are whitewashing that colonial history through these textbooks. One major criticism is that they do not mention that, during World War II, the Japanese forced Korean women into sexual slavery. The textbooks describe the women as having been “drafted” to work, a euphemism that downplays the brutality of what actually occurred. Some Japanese textbooks dismiss an important Korean independence demonstration in 1919 as a “riot.” In reality, Japanese soldiers attacked peaceful demonstrators, leaving roughly 6,000 dead and 15,000 wounded (Crampton 2002).

The protest affirms that textbooks are a significant tool of socialization in state-run education systems.

The Workplace

Just as children spend much of their day at school, many U.S. adults at some point invest a significant amount of time at a place of employment. Although socialized into their culture since birth, workers require new socialization into a workplace, in terms of both material culture (such as how to operate the copy machine) and nonmaterial culture (such as whether it’s okay to speak directly to the boss or how to share the refrigerator). In the chapter introduction, Noel did not fully embrace the culture of their new company. Importantly, the obligation of such socialization is not simply on the worker: Organizational behavior and other business experts place responsibility on companies; organizations must have strong onboarding and socialization programs in order to build satisfaction, productivity, and workplace retention (Cebollero 2019).

Different jobs require different types of socialization. In the past, many people worked a single job until retirement. Today, the trend is to switch jobs at least once a decade. Between the ages of eighteen and forty-six, the average Baby Boomer of the younger set held 11.3 different jobs (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). This means that people must become socialized to, and socialized by, a variety of work environments.

While some religions are informal institutions, here we focus on practices followed by formal institutions. Religion is an important avenue of socialization for many people. The United States is full of synagogues, temples, churches, mosques, and similar religious communities where people gather to worship and learn. Like other institutions, these places teach participants how to interact with the religion’s material culture (like a mezuzah, a prayer rug, or a communion wafer). For some people, important ceremonies related to family structure—like marriage and birth—are connected to religious celebrations. Many religious institutions also uphold gender norms and contribute to their enforcement through socialization. From ceremonial rites of passage that reinforce the family unit to power dynamics that reinforce gender roles, organized religion fosters a shared set of socialized values that are passed on through society.

Although we do not think about it, many of the rites of passage people go through today are based on age norms established by the government. To be defined as an “adult” usually means being eighteen years old, the age at which a person becomes legally responsible for him- or herself. And sixty-five years old is the start of “old age” since most people become eligible for senior benefits at that point.

Each time we embark on one of these new categories—senior, adult, taxpayer—we must be socialized into our new role. Seniors must learn the ropes of Medicare, Social Security benefits, and senior shopping discounts. When U.S. males turn eighteen, they must register with the Selective Service System within thirty days to be entered into a database for possible military service. These government dictates mark the points at which we require socialization into a new category.

Mass media distribute impersonal information to a wide audience, via television, newspapers, radio, and the Internet. With the average person spending over four hours a day in front of the television (and children averaging even more screen time), media greatly influences social norms (Roberts, Foehr, and Rideout 2005). People learn about objects of material culture (like new technology and transportation options), as well as nonmaterial culture—what is true (beliefs), what is important (values), and what is expected (norms).

Sociology in the Real World

Girls and movies.

Movies aimed at young people have featured a host of girls and women leads. Snow White , Cinderella , and Sleeping Beauty gave way to The Little Mermaid , Beauty and the Beast, and Mulan . In many of those cases, if the character is not a princess to begin with, she typically ends the movie by marrying a prince or, in the case of Mulan, a military general. Although not all “princesses” in Disney movies play a passive role in their lives, they typically find themselves needing to be rescued by a man, and the happy ending they all search for includes marriage.

Alongside this prevalence of princesses, many parents are expressing concern about the culture of princesses that Disney has created. Peggy Orenstein addresses this problem in her popular book, Cinderella Ate My Daughter . Orenstein wonders why every little girl is expected to be a “princess” and why pink has become an all-consuming obsession for many young girls. Another mother wondered what she did wrong when her three-year-old daughter refused to do “nonprincessy” things, including running and jumping. The effects of this princess culture can have negative consequences for girls throughout life. An early emphasis on beauty can lead to reduced interest in math and science among girls, as well as avoiding educational scenarios that are "typically feminine" (Coyne 2016).

Others acknowledge these issues, but find princess movies and "princess culture" less alarming. Some remind concerned parents that children have an array of media and activities around them, and the children may be happy wearing their princess outfit while digging for worms or going to hockey practice, which run counter to feminine stereotypes (Wagner 2019). Others indicate that rather than disallowing princess movies and merchandise, engaging with the children as they enjoy them might be more effective. And many people acknowledge that girls and women are often currently portrayed differently than they were in years past.

Disney seems to have gotten the message about the concerns. Its 2009 Tiana and the Frog was specifically billed as "a princess movie for people who don't like princess movies," and features a talented chef and business owner—who didn't need a man to rescue her—as its main character. Brave 's Merida and the title character in Moana seem to go out of their way to separate themselves from traditional princesses, and undertake great acts of bravery to help others. Frozen focuses on sisterly love rather than romantic love. And though she was never meant to be a princess, Star Wars ' Rey was the go-to girls Halloween costume for years after she was introduced in the movies.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/5-3-agents-of-socialization

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Religion, Identity, Socialization, and Well-Being

- First Online: 13 July 2022

Cite this chapter

- Preeti Kapur 4 ,

- Girishwar Misra 5 &

- Nitin K. Verma 6

165 Accesses

Life involves a series of negotiations between alternative choices, a variety of stresses and strains, management of relationships, striking a balance between personal and social needs and demands. It is often punctuated by a series of religious engagements across the life span. The period of transition from adolescence to young adulthood is viewed as very critical in many religions. The agents of socialization play a crucial role in the acquisition and maintenance of religious beliefs and behaviors. On the other hand, cognitive maturation allows the acceptance and transmission of religious values, customs, and traditions. Once the foundation is laid down, maintaining the religious beliefs and practices continues during the subsequent phases of life. The religious beliefs and practices, in turn, construct and maintain self and identity, with different pathways for men and women, giving shape to a variety of coping strategies. Developmental research tends to suggest potential relationships between self-construal, religious identity, and well-being.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Agarwal, M., & Dalal, A. K. (1993). Beliefs about the world and recovery from myocardial infarction. Journal of Social Psychology, 133 , 385–394.

Article Google Scholar

Aldwin, C. M., & Levenson, M. R. (2001). Stress, coping, and health at midlife: A developmental perspective. In M. E. Lachman (Ed.), The handbook of mid-life development (pp. 188–214). New York.

Google Scholar

Anand, J. (2005). Role of nonconscious processes in psychological healing . Unpublished doctoral dissertation, A.P.S. University, Rewa, India.

Anand, J. (2009). Psychological healing and faith in the doctrine of Karma. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 12 , 817–832.

Ano, G. G., & Vasconcelles, E. B. (2005). Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61 (4), 461–480.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ardelt, M. (2003). Effects of religion and purpose in life on elders’ subjective well-being and attitudes towards death. Journal of Religious Gerontology, 14 , 55–77.

Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Meanings of life . Guilford Press.

Chamberlain, K., & Zika, S. (1988). Religiosity, life meaning and well-being: Some relationships in a sample of women. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 27 , 411–420.

Dalal, A. K., & Singh, A. K. (1992). Role of causal and recovery beliefs in psychological adjustment to a chronic disease. Psychology and Health: An International Journal, 6 , 193–203.

Dalal, A., & Misra, G. (2006). Psychology of health and well-being: Some emerging perspectives . Psychological Studies, 2, (pp. 2–3).

Dalal, A. K. (2000). Living with a chronic disease: Healing and psychological adjustment in Indian society. Psychology and Developing Societies, 12 , 67–82.

Dalal, A. K., & Pande, N. (1988). Psychological recovery of the accident victims with temporary and permanent disability. International Journal of Psychology, 23 , 25–40.

Davar, B., & Lohokare, M. (2009). Recovering from psychosocial traumas: The place of dargahs in Maharashtra. Economic & Political Review, 44 , 16.

Deiner, E., & Clifton, D. (2002). Life satisfaction and religiosity in broad probability samples. Psychological Inquiry , 13 , 206–209.

Diener, E., Tay, L., & Myers, D. (2011). The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101 , 1278–1290.

Dutta, R. (2010). Pilgrimage as a religious process: Some reflections on the identities of the Srivaisnavas of South India. Indian Historical Review, 37 (1), 17–38.

Elizabeth, M. D., & Scarlett, W. G. (Eds.). (2006). Religious and spiritual development . Sage.

Emmons, R. A. (1999). The psychology of ultimate concerns . Guilford Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. Selected papers . International University Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis . Norton Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1974). Dimensions of a new identity . Norton Press.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2002). How does religion benefit health and well-being? Are positive emotions active ingredients? Psychological Inquiry, 13 , 209–213.

Galea, S., Merchant, R. M., & Lurie, N. (2020). The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180 (6), 817–818.

Geaves, R. (2010). Sikh controversies concerning Punjabi pilgrimage sites used for healing and possession. In Fabrizio Ferrari (Ed.), Health and Religious rituals in South Asia: Disease, possession and healing. Routledge.

Geyer, A. L., & Baumeister, R. F. (2005). Religion morality and self-control: Values, virtues and vices. In R. F. Paloutizan & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 412–434). Guildford Press.

Jadhav, S. (1996). The cultural origins Western depression. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 42 , 269–286.

Joshi, M. S. (1995). Lay explanations of the cause of diabetes in India and the U.K. In I. Markova and R.M. Farr (Eds.), Representations of health, illness and handicap (pp. 163–188). Harwood.

Joshi, P. C. (2000). Relevance and utility of traditional medical systems (TMS) in the context of a Himalayan tribe. Psychology and Developing Societies, 12 , 5–29.

Kakar, S. (2003). Psychoanalysis and eastern spiritual traditions. Journal of Analytic Psychology, 48 , 659–678.

Kakar, S. (1978). The inner world . Oxford University Press.

Kakar, S. (1982). Shamans, mystics & doctors . Oxford University Press.

Kapur, P., & Misra, G. (2011). Social identity in India: Continuities and fractures. In G. Misra (Ed.), Handbook of Psychology in India (pp. 149–162). Oxford University Press.

Khan, A., Ahmad, R., Hamdan, A. R., Mustaffa, M. S., & Tahir, M. L. (2014). Does psychological strengths and subjective well-being predicting parental involvement and problem solving among Malaysian and Indian students? Springer plus, 3 , 1–6.

Kim-Prieto, C., & Miller, L. (2018).Intersection of religion and subjective well-being. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers.

Koenig, H. G. (2020). Maintaining health and well-being by putting faith into action during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health, 59 (5), 2205–2214.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Krause, N. (2003). Race, religion, and abstinence from alcohol in late life. Journal of Aging and Health, 15 , 508–533.

Levenson, M. R., Aldwin, C. M., & D’Mello, M. (2005). Religious development from adolescence to middle adulthood. In Raymond, F. Paloutizan& C. L. Park, (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality , (pp 144–161). Guildford Press.

Lun, V. M., & Bond, M. H. (2013). Examining the relation of religion and spirituality to subjective well-being across national cultures. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5 , 304–315.

Mahoney, A., & Tarakeshwar, N. (2005). Religion’s role in marriage and parenting in daily life and during family crises. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 177–195). The Guilford Press.

Mak, M. C. K., Han, Y. M. Y., You, J., Jin, M., & Bond, M. H. (2011). Building life satisfaction through attachment to mother and beliefs about the world: Social axioms as mediators in two cultural groups. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14 , 223–239.

McFadden, S. H. (1999). Religion, personality and aging: A life span perspective. Journal of Personality, 67 , 1081–1104.

McFadden, S. H., & Levin, J. S. (1996). Religion emotion and health. In C. Magi & S. H. McFadden (Eds.), Handbook of emotions, adult development and aging (pp. 349–365). Academic Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Metcalf, B. D. (2004). Islamic Contestations: Essays on Muslims in India and Pakistan . Oxford University Press.

Nanda, M. (2009). The god market: How globalization is making India more Hindu. Random House.

Nicholas, E. (2003). How to Stay Afloat. Community Care, 6 , 40–41.

Nooney, J., & Woodrum, E. (2002). Religious coping and church-based social support as predictors of mental health outcomes: Testing a conceptual model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41 , 359–368.

Norrie, B. (2009). Human Factors and safe patient care. Nursing Management, 17 (2), 203–211.

Oberoi, H. S. (1994). The construction of religious boundaries: Culture, identity and diversity in Sikh tradition . Oxford University Press.

Oman, D., & Thorsen, C. E. (2003). Spiritual modelling: A key to spiritual and religious growth. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 13 , 149–165.

Pandey, J., Kumar, R. & Thapa, K. (Eds.), (2019). Psychological perspectives on diversity and social development . Springer.

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. M. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 564 , 519–543.

Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 374 , 710–724.

Pargament, K. I., & Mahoney, A. M. (2005). Sacred matters: Sanctification as a vital topic for the psychology of religion. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 15 , 179–198.

Pargament, K. I., Ano, G. G., & Wachholtz. (2005). The religious dimension of coping: Advances in theory, research and practice. In R. F. Paloutizan & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 479–495). Guildford Press.

Raj, S. J., &. Dempsey, C. G (Eds.), (2002). Popular Christianity in India. Riting between the Lines. SUNY.

Ramsay, J. E., Tong, E. M., Chowdhury, A., & Ho, M. H. R. (2019). Teleological explanation and positive emotion serially mediate the effect of religion on well-being. Journal of Personality, 87 , 676–689.

Sen, A. (2006). Identity and violence: The illusion of destiny . Allen Lane.

Sharma, S., & Sharma, M. (2006). Sustaining and enhancing health/well-being of Indian students: The role of spiritual and religious interventions. Psychological Studies, 51 (2), 113–118.

Shinde, K. (2011). Placing communities: Spatiality and ritual performances in Indian religious tourism. Tourism, 59 , 335–352.

Singh, K. S. (1992). The people of India: An introduction . Anthropological Survey of India.

Singh, S. (2009). Pilgrim culture of tirtha in India: Enculturation of new age movements within Age-Old Rituals. In S. Singh (Ed.), Domestic Tourism in Asia: Diversity and Divergence . Earthscan Publications.

Spilka, B., Hood, R. W., Jr., Hunsberger, B., & Gorsuch, R. L. (2003). The psychology of religion: An empirical approach (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Sreekumar, R. (2008). The pattern of association of religious factors with subjective well-being: A path analysis model. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 34 , 119–125.

Villani et. al. (2019). The role of spirituality and religiosity in subjective well-being of individuals with different religious status. Frontiers in Psychology . https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01525/full .

Willits, F. K., & Crider, D. M. (1988). Religion and well-being: Men and women in the middle years. Review of Religious Research, 29 , 281–294.

Wink, P., & Dillon, M. (2002). Spiritual development across the adult life course: Findings from a longitudinal study. Journal of Adult Development, 9 , 79–94.