Global site navigation

- Celebrity biographies

- Quotes - messages - wishes

- Bizarre facts

- Celebrities

- Family and Relationships

- Women Empowerment

- South Africa

- Cars and Tech

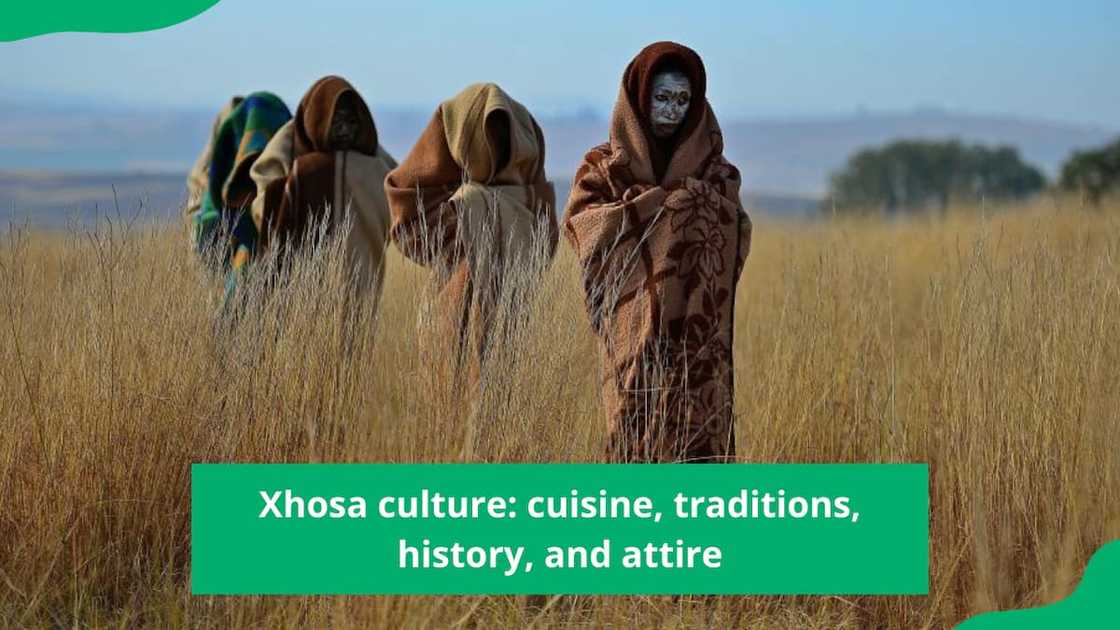

All about Xhosa culture: cuisine, traditions, history, and attire

The Xhosa are often called the "Red Blanket People" because red and orange are the primary colors for their traditional attire. This tribe is part of the four Nguni (nations) tribes in South Africa. Like numerous other African communities, the Xhosa culture has rich and well-laid-out traditions, beliefs, rites, rituals, and ways of life. This article shares the most important aspects of the Xhosa culture, from religious beliefs to wedding, birth, circumcision, and death rites. It also touches on aspects about their homesteads, food, folklore, songs, and art.

The Xhosa are a Bantu-speaking tribe and the second-largest tribe in South Africa. These people are predominantly found in the Eastern and Western Cape provinces. The Xhosas call their language isiXhosa, but the world calls it Xhosa in English. Discover the most interesting facts about the Xhosa culture below.

The Xhosa culture and traditions

The Xhosa tribe is further divided into various subtribes, mainly the Mpondomise, Mfengu, and Thembu. They also have smaller subtribes like the Bhaca, Bomvana, Fingo, Nhlangwini, and Xesibe. Read the most intriguing truths about Xhosa origins and their culture below:

White man embraces Xhosa tradition with stylish attire in viral TikTok video, wins praise online

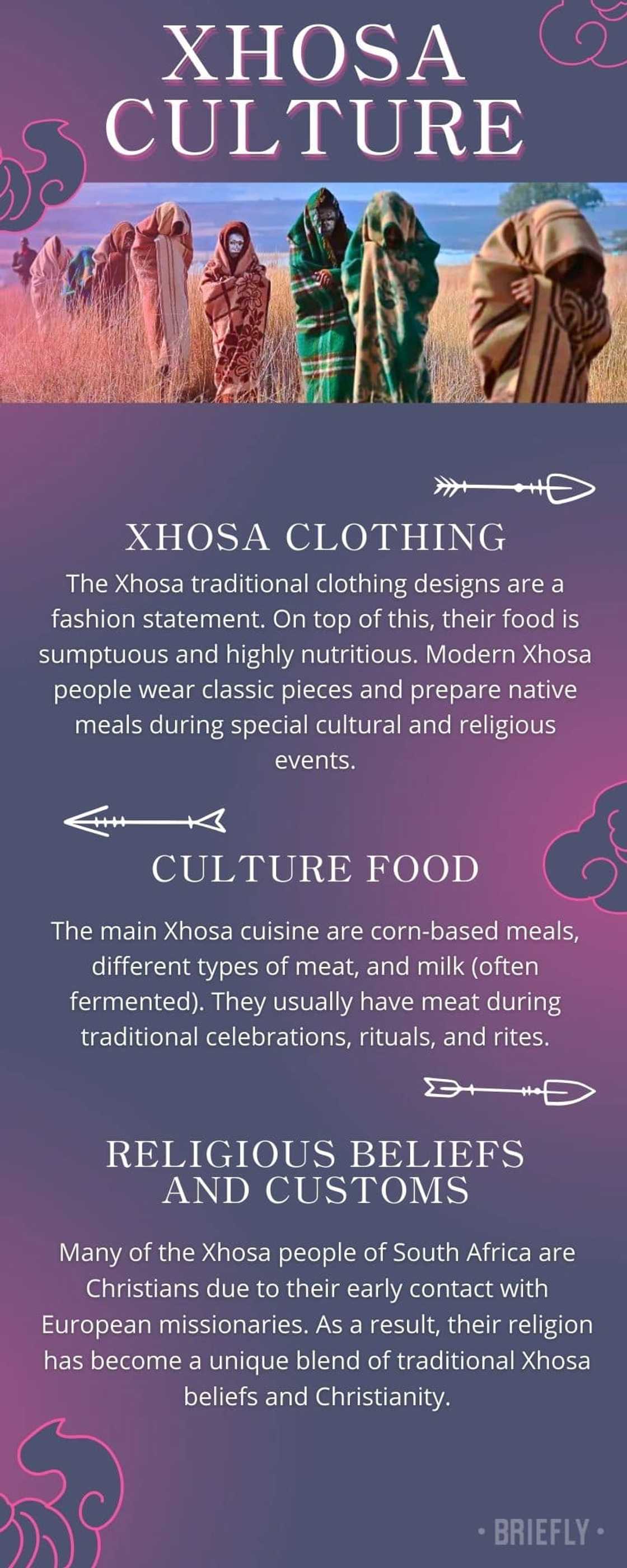

Xhosa culture: clothing and food

The Xhosa traditional clothing designs are a fashion statement. On top of this, their food is sumptuous and highly nutritious. Modern Xhosa people wear classic pieces and prepare native meals during special cultural and religious events.

What are some foods of the Xhosa culture?

The main Xhosa cuisine are corn-based meals, different types of meat, and milk (often fermented). They usually have meat during traditional celebrations, rituals, and rites. Some popular Xhosa meat-based dishes are inyama yebhokwe , umleqwa , inyama yegusha , and inyama yenkomo .

Other popular Xhosa dishes are umngqusho (a savory combination of corn, beans, and spices), umqa (stiff maize meal porridge served with curried cabbage or spinach), and umxhaxha (a combination of pumpkin and corn), and umkhuphu (maize meal and beans).

Xhosa has numerous rules about food . For example, the liver is for young men, while the inguba (the meat between the intestines and the stomach wall) is reserved for older men. Men do not drink milk from a village where they might get wives, women do not eat eggs, and newly married women are not allowed to eat some types of meat.

Mzansi Magic's Kokota cast with images, plot summary, full story, trailer

What is the Xhosa traditional wear?

Traditional Xhosa attire are usually in brilliant colors like red, white, orange, or yellow. Married women wear long aprons over their dresses. The isikhakha (dress) is decorated with black bias binding at the hem and neck. The women complete the look with a cloak made from the same material, head scarves, breaded jewelry, and a sling bag called inxili .

A Xhosa head scarf for a woman is made of two or three materials of colors representing the different areas she comes from. Meanwhile, their beaded jewelry are primarily red, blue, dark blue, white, and yellow.

Most Xhosa traditional attire are cotton-woven and come in numerous unique styles and patterns. The men wear wrap-around skirts running from the waist to the feet. These are accompanied by a long scarf thrown over one shoulder, which can serve as a cloak when it gets cold.

Video of Venda wedding takes TikTok by storm with cultural spectacle and traditional outfits

Additionally, the men carry sticks given to them during their circumcision ceremonies. They can use these sticks to defend themselves and their families. Xhosa men learn how to fight with sticks growing up. Boys practice this fight while herding cattle in the veld (pastures).

Xhosa religious beliefs and customs

Today, many of the Xhosa people of South Africa are Christians due to their early contact with European missionaries. As a result, their religion has become a unique blend of traditional Xhosa beliefs and Christianity.

Who is the God of Xhosa?

The supreme being in Xhosa is called Mdali , Thixo , or Qamata , and they communicate with him through ancestral intermediaries. The primary role of the Xhosa ancestral intermediaries is to perform rituals and sacrifices, which are believed to help the people communicate with the spirits of their ancestors.

The ancestral spirits, in turn, act as mediators between the people and the deity. Xhosa people believe that Qamatha , the creator of all things, controls all things, and without the rules he laid down for humans, there would be confusion, madness, and uncertainty on Earth.

Census 2022 shows increase of Shona speakers in Limpopo linked to Zimbabwean migrants

Although most Xhosa-speaking people generally accept Christianity, some of the tribes' descendants practice both Christianity and traditions.

The Xhosa marriage ceremony

Umtshato (marriage ceremony) is among Xhosa culture's most significant traditional events. The ceremony begins with the ukuzena process, which can be done in three ways.

The marriage proposal

The couple can do the ukuzibonela , whereby the man proposes to a woman before informing his family to accompany him to meet her people.

Alternatively, the girl's parents can practice ukholela , whereby they identify a man (a potential spouse for their daughter). Afterward, they send a family member (uncle or elder brother) to plant a spear in his parent's home early in the morning.

A family that wakes up to a spear planted in their home asks around to know where it came from. If they accept the proposal, they will return the spear by planting it in the home of the girl's parents. If they reject the proposal, they will keep the spear.

SABC2's Married Our Way wedding show: What can you expect?

The third alternative is the ukuthwala , whereby the couple marry without consent from their parents. This usually happens when they fear opposition from the lady's family. After a secret courtship, they agree on the day and time of eloping.

The man sneaks into the woman's home in the evening and takes her to his home, where his parents will be waiting for introductions. The following morning, the man's family will visit the girl's parents to express their intentions to have her as a daughter-in-law. The girl's parents accept the proposal and request the man to pay a fine for eloping with their daughter.

The fourth option is the ukufilisha , whereby the man speaks to the girl's parents. It is up to the parents to reject or accept his proposal, and the bride-to-be's opinion does not matter.

The marriage proposal acceptance letter

After both families are aware of a potential marriage between their children, the man's family writes a proposal letter to the woman's family. The latter also responds with a letter. Two men from the woman's home deliver it to the man's parents. This traditional letter acceptance process is called ukuvuma .

What happened to Big Nuz members? Here is everything we know

The lobola ceremony

The woman's family informs the man's family of the date for the lobola ceremony through the acceptance letter. The groom's family pays ikhazi (dowry or bride price), which is usually money or cattle (ten to twelve cows). The dowry must be paid a few days or months before the wedding, and the man can add gifts like alcohol.

The amount of cash and the number of cattle a man pays depends on the agreement between his family and the bride's family. Additionally, if the marriage proposal was initiated by ukufilisha or ukholela , the girl's father or uncle can help the groom by paying part of the dowry.

The lobola ceremony has several stages. The first payment, an imvulamlomo , is a small token or fee the groom pays the bride's family before his family can negotiate ikhazi (dowry or bride price) with them.

Xhosa woman celebrates traditional wedding in stunning video, over 400 000 peeps in love

The second token, isazimzi, demonstrates the seriousness of the groom's family. It assures the woman's family that the groom's people specifically selected that girl's home among all the other homes in the village.

After the negotiations and agreeing on the dowry size, the bride's family performs isivumo . They slaughter a cow to feed the groom's family. It signifies the two families accept to have a relationship through their children's marriage.

The ikhazi is the main dowry, and two special cows should be set apart from all the cows the man pays. One is an ubuso bentombi (a cow for the bride's face), and the other is an inkomo yomthuko (a cow for the bride's mother).

The man pays intlawulo (a sacred cow or goat) if he has a child or children with the bride. It must be killed, cooked, and feasted on by both families on the same day it is brought to the woman's home. This cow is a fine the bride's family imposes on the man. Since having children out of wedlock is frowned upon, the ritual cleanses the name of the girl's family and also restores their dignity.

e.tv's Smoke & Mirrors: cast, plot summary, trailer (with images)

The Xhosa wedding ceremony

The Xhosa wedding ceremony takes at least three days. After the lobola ceremony, people escort the bride to the groom's home for uduli (bridal party). The party happens on the eve of the wedding day. The man's family gives the bride and her guests a special hut and gifts them a goat called umathulanthabeni .

The bride's people pay a fine called isiphembamlilo for the groom's family to give them a lighter to make a fire for cooking or roasting the goat meat.

The following day, they will pay the man's family a cow called inkomo yobulunga as blessings to the bride as she moves into her new home. A rope is made from the skin of the inkomo yobulunga and tied around the bride and her children (if she has any) to protect them from evil.

e.tv's Nikiwe: cast, plot summary, full story, trailer, episodes

Later in the evening, the man's family will sacrifice a cow and offer the bride's family a leg, inxaxheba , as a token of appreciation for the new family ties. After that, the young maidens from the bride's family will help her light her first fire, which she will use when they are gone.

The following day will be for umdundo or umtshatso (the actual wedding). The man wears traditional outfits, while the bride wears her isishweshwe skirt and apron, ikhetshemiya (headcloth), imibhaco (beaded necklace and bracelets), and covers herself in ingcawa (a blanket).

The bride's people sing and dance while taking her to enkundleni (an assembly of the groom's family). Usually, the men are the lead singers, while the women respond to the songs.

When they get to the forum, two men from the bride's side uncover her to reveal her face. In response, male elders from the groom's side welcome and counsel her on how to conduct herself as a married woman. After that, female elders are given the chance to offer her more marital advice. This guiding and counseling process is called ukuyala .

Exclusive: Somizi, Skhumba, and JSomething to be investigators on 'The Masked Singer SA'

After the ukuyala , people feast and drink umqombothi (traditional liquor) while singing and dancing ukuxhentsa (traditional dance). The families then gather again and give the bride a spear to throw as a sign she has been accepted into the new family. If the spear falls on the ground, it signifies her marriage will fail, but if it does not, the marriage will last.

The morning after the umdundo , the groom's family gives the bride's family blankets and other gifts. Meanwhile, the woman's family returns home, leaving behind an inkubabulongwe (a young girl) to help the makoti (newlywed woman) with chores like cooking, fetching firewood and water, and cleaning the hut.

In the evening, the groom's family will dress the new wife in umbhaco or umajelumane (a blue makoti attire), tie a small blanket around the waist, and cover her head with iqhiya (a black headscarf). She will sit on a grass-woven mat and eat goat meat and sour milk. The woman will use the mat wherever she goes instead of sitting in a chair.

Zulu, Xhosa, Tswana and 2 more traditional wedding dresses Mzansi loved, South African expert explains cost, fabrics and designs

For about three or four months after the wedding, she will undergo ukuhlonipha to learn how to do house chores, dress decently, address elders, and so on.

Xhosa birth rituals

Xhosa people do not pick children's names before birth. They wait till the child is born to know its gender, what it looks like, and how people feel so that they can give it an appropriate name.

The mother and child's seclusion period

A birthing mother is called umdlezana and is aided by her grandmother or midwives (women in the community who have experience helping fellow women deliver babies).

She gives birth in her rondavel , which is a circular dark room made with mud walls and a conical grass-thatched roof. The mother and baby spend ten days indoors, inside the rondavel , to allow the baby's umbilical cord to fall off.

Top trees in South Africa: A-Z exhaustive list with images

During that time, the grandmother or community midwives mix ash, sugar, and a plant called umtuma , then rub the paste on the baby's umbilical cord. The mixture aids the drying process, which, in turn, makes the placenta fall off faster.

Once the placenta has fallen off, close female family members and a few women from the community gather in the rondavel to perform the sifudu ritual . They burn aromatic leaves from the sifudu tree and float the baby (upside-down) over its pungent smoke three times. The smoke makes the baby cough, and sometimes, scream severely.

The women return the baby to the mother, who then passes it under her left and right knees. The Xhosa people believe the sifudu ceremony strengthens the baby's spirit and protects it from future evil.

Afterward, they women will wash and smear the baby with ingceke , a white chalk made of grounded mtomboti wood. Its sweet smell stays on the baby for weeks.

Who is Konka Soweto owner? Everything to know about the restaurant and club

The mother breastfeeds the baby before the women bury or burn the inkaba (placenta). The ritual protects the baby from sorcery and bonds it with its clan, ancestral land, and the spiritual ancestral world. In the future, when the baby is an adult, he/she can visit where their inkaba was buried to communicate with their ancestors.

What happens after the mother and child's seclusion period?

The family sacrifices a goat and invites friends and relatives to the imbeleko feast. The ceremony marks the end of the mother's ten-day period of solitude. Those who do not practice traditional Xhosa birth rituals can still be invited.

The family treats the goat's skin as a sacred item. They dry and preserve it for the new clan member, the baby, to sleep on in the future in times of trouble and connect with the ancestors.

The Xhosa naming ceremony

Dudu Busani-Dube's books list in order: A must-read for booklovers

The child is named during the imbeleko ceremony. The Xhosa clan's “Praise-Singer” summons the ancestors vocally with praises. The singer chants qualities the family would love the ancestors to below upon the baby so that it grows into a responsible clan member.

After that, the baby is named after its father (surname) and one of its ancestors (first name). Also, it can be given names that signify seasons (rainy season, planting time, harvesting time, or the famine season) or the family's wishes for the baby, such as Sibabalwe (the blessed one). All traditional Xhosa names have beautiful meanings.

Xhosa circumcision rituals

The isiXhosa culture circumcises men and women. The abakweta (male initiates-in-training) live in bhoma (secluded huts) away from the village. The boys wear loincloths, cover themselves in blankets for warmth, and smear white clay on their bodies from head to toe.

BET Redemption cast (with images), trailer, plot summary, full story, episodes

The seclusion lasts about a month and is in two phases. During the first seven days after an ingcibi (traditional surgeon surgically has removed their foreskins, the initiates are confined to the huts and fed on certain foods. Some foods and water may be restricted. The initiates are not allowed to cry or show signs of pain as this would be considered shameful and an indication of weakness.

The second phase lasts two to three weeks, and an ikhankatha (traditional attendant) looks after them. The seclusion period ends with a goat sacrifice and the boys washing themselves. Also, they burn down the huts and the initiates' possessions, including their clothing, to symbolize a new beginning.

Each initiate receives an ikrwala (a new blanket), representing he is a new man or amakrwala . What's more, the initiates dress formally for some time after the rite.

Ndebele clan names, best baby names and surnames: Exhaustive list

The female circumcision ritual is shorter than that of their male counterparts. The intonjane (female initiates-in-training) stay away for a week, and no surgical operation is performed on their bodies.

Xhosa death and burial rituals

The Xhosa have well-defined burial rituals and practices . The nuclear family announces the death of their loved one to the extended family. The process is called umbiko . After that, relatives gathers to prepare for the burial.

The family conducts the indlu enkulu (or emptying the bedroom ritual) to honor the deceased and create space for mourners to view the body. One of the family elders guards the body throughout the days the burial preparations are going on. These days, people take the bodies to the mortuary.

The widow is not expected to talk too much. Some of the aunts sit with her in the house on grass mats and cover themselves with blankets while the other family members continue with the ukuvela (burial preparations).

Top 20 interesting facts about South Africa you ought to know | Details for travellers

Visitors and people trooping into the home to offer their condolences are allowed to hold imithandazo (prayers) for the family. Meanwhile, the community gravediggers dig and prepare grave. It takes about four days for them to complete the work and the family cooks for them daily as a sign of appreciation.

When the family brings the corpse home from the mortuary, they practice ukuvulwa kwebhokisi . This means a designated person speaks to the deceased before they leave the morgue and when they arrive home. Neighbors, relatives, and anyone can view the body in the coffin when it gets home. Xhosa people call this ukubona umfi .

Xhosa funerals ( umngcwabo ) do not come with an invitation. So, anyone can attend. The family provided a bull and umngqusho (corn and beans) to feed the mourners on the burial day.

A day after, women wash the deceased’s belongings to wash away death and family members also shave their hair, indicating that life continues after death; just like how the hair grows again.

How to get ready for Christmas in South Africa: lunch ideas, trees, crackers, table decor

A year after the person's death, the family sacrifices a bull to beseech the spirit return home. They believe the spirit must live with its family to guide and protect them.

If someone loses a spouse, they observe a one-year mourning period, during which the widow or widower wears black traditional Xhosa attire.

Where are the Xhosa originally from?

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Xhosa-speaking people have lived in South Africa's Eastern Cape area since the 7th century. Xhosa ancestors, the Nguni, are believed to have occupied central and northern Africa. They migrated and settled in the southern part of the continent before the arrival of the Dutch settlers.

The Nguni comprised several clans, such as the Gcaleka, Ngika, Ndlambe, Dushane, Qayi, and Gqunkhwebe of Khoisan origin. Their unity and ability to fight off colonial encroachment into their land were weakened by the famines and political divisions in the 19th century.

Muvhango Teasers for July 2021: Will Mpho's baby be found?

What language do the Xhosa speak?

The Xhosa language is called isiXhosa (or Xhosa in English). It is spoken by about 16% of South Africa's population. Unique click sounds distinguish this Bantu language and makes it sound slightly different from from Ndebele and Swazi languages. For example, the X, Q, KR, and CG form the clicks. The click Xhosa consonants were borrowed from Khoi or San words.

What are the Xhosa family rules?

The Xhosa family is primarily patriarchal. So, women and children submit to the men's authority and leadership as heads of households and the entire community. The tribe allows polygamous marriages so long as a man pays the lobola (bride price) for each wife.

What do Xhosa homesteads look like?

Xhosa homesteads, imizi , are scattered over the rural landscape of the Eastern and Western Cape provinces of South Africa. The homesteads round huts with grass-thatched roofs and mud walls. The roof comprises circular wooded poles and saplings, bent and bound to form a conical shape.

Vele Manenje biography, age, on Muvhango, accident, awards

A Xhosa homestead has several huts because they are polygamous. So, each wife needs a separate house. Additionally, sons who have been circumcised or married also need their own huts. The chiefs or wealthy men with large cattle herds sometimes allowed families not blood-related to reside at their homesteads.

What is the culture of Xhosa?

The Xhosa culture is extensive. First, they believe in a supreme being in Xhosa is called Mdali , Thixo , or Qamata . Xhosas communicate to him through ancestral intermediaries who invoke the spirits of the ancestors through rituals and sacrifices. Additionally, the Xhosas have unique wedding, birth, circumcision, and death rituals. They have traditional foods, folklore songs and stories, and native art.

Did the Xhosa have any artwork?

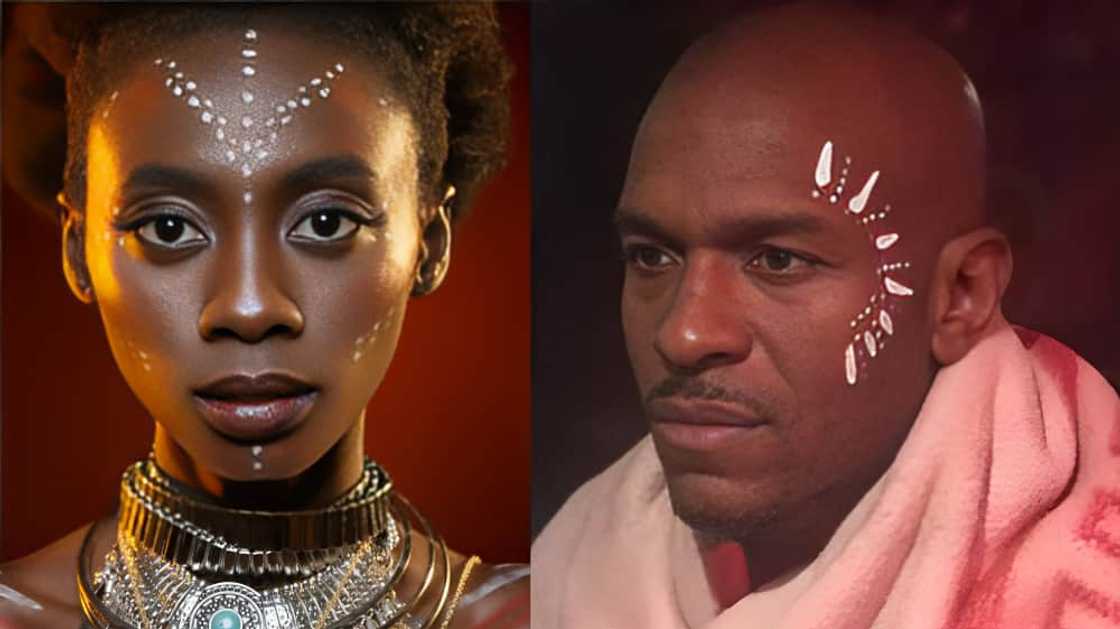

Umchokozo , face painting, plays a significant role in Xhosa culture. The white or yellow ochre decorations are sometimes painted over their eyebrows, the bridge of their noses, and cheeks.

Mzansi Magic Ehostela cast (with images), seasons, the full story

For men, face painting indicates status and conveys a strong cultural meaning. Meanwhile, women decorate their faces as a ritual to prepare themselves to be custodians of their culture.

Xhosa people make beads from nutshells, wood, glass, and metal. Anyone can wear the Xhosa beadwork as a fashion statement, even if they are not descendants of this tribe.

Xhosa folklore songs and stories

Like other Bantu languages, the Xhosa culture is rich in folklore songs , dances, stories ( intsomi ), verbal expressions, idioms, poems ( izibongo ), and proverbs. Most Xhosa stories and folktales are about the tribe's history, religious beliefs, and heroes.

Qongqothwane , by Miriam Makeba, is a timeless Xhosa wedding song. Meanwhile, most popular Xhosa folklore stories are about the first person on Earth and the origin of death.

The Xhosa tribe believes death originated when Qamatha (god) sent the chameleon to earth to tell people they would never die. However, the chameleon got tired on its way to Earth and decided to rest.

What is the most spoken language in South Africa? Top 11 languages

The lizard found the chameleon resting and asked it where it was going. After the chameleon explained its mission, the lizard ran and told the people they would die. An outcry erupted on the Earth, with people crying because they were going to die.

When the chameleon heard this outcry, it proceeded to the earth to tell the people the true message from Qamatha , but they did not believe it. That is why people die.

What are the five habits of the Xhosa culture?

The Xhosa people emphasize traditional practices and customs inherited from their forefathers. Their culture is extensive because it has been practiced for centuries and passed down from generation to generation. Here are some five things they do:

- Xhosa people live in traditional homesteads called imizi.

- They speak in unique click sounds.

- A groom pays lobola (dowry) to the bride's family.

- They name children after their fathers and ancestors.

- Xhosa men undergo circumcision while the women pass through an initiation rite.

Top 10 great ancient African leaders you should know about

What is imbeleko in the Xhosa culture?

The imbeleko is a Xhosa child naming ceremony, and it marks the end of the ten-day mother and child seclusion period. The family introduces the baby to friends and relatives during this ceremony. Anyone can attend the event, including people who are not Xhosa.

What are some traditional customs of the Xhosa people?

The Xhosa people have many traditions and customs. Here are some five things they do:

- Xhosa boys learn to stick fighting early when herding cattle in the veld (pastures).

- Married Xhosa women wear long aprons over their dresses, cloaks over the dresses, head scarves, breaded jewelry, and carry sling bags called inxili .

- Xhosa men wear wraparound skirts running from the waist to the feet. These are accompanied by a long scarf thrown over one shoulder and serve as a cloak when it gets cold.

- Umchokozo , face painting, plays a significant role in Xhosa culture. They paint themselves over their eyebrows, the bridge of their noses, and cheeks.

- Xhosa homesteads have round mud huts with conical-shaped grass-thatched roofs.

Deception Zee World cast, full story, plot summary, teasers, final episode

Xhosa culture is broad and exciting to learn. Their beliefs, traditions, rituals, rites, and structures make them unique people. The Xhosa people are careful about preserving their culture and are dedicated to passing it on to the younger generations.

Briefly.co.za published an article about the top Sotho names for boys and girls. The Sotho language is part of the Bantu ethnic group, and there are three different dialectical groups within the Sotho tribe: Sepedi (northern Sotho), Sesotho, and Setswana.

The Sotho people are in Botswana, Lesotho, and South Africa. Like other African communities, they have a unique way of naming their newborns. Additionally, all Sotho names have deep cultural meanings.

Source: Briefly News

Peris Walubengo (Lifestyle writer) Peris Walubengo is a content creator with 5 years of experience writing articles, researching, editing, and proofreading. She has a Bachelor of Commerce & IT from the University of Nairobi and joined Briefly.co.za in November 2019. The writer completed a Google News Initiate Course. She covers bios, marketing & finance, tech, fashion & beauty, recipes, movies & gaming reviews, culture & travel. You can email her at [email protected].

Jackline Wangare (Lifestyle writer) Jackline Simwa is a content writer at Briefly.co.za, where she has worked since mid-2021. She tackles diverse topics, including finance, entertainment, sports, and lifestyle. Previously, she worked at The Campanile by Kenyatta University. She has more than five years in writing. Jackline graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (2019) and a Diploma in Marketing (2015) from Kenyatta University. In 2023, Jackline finished the AFP course on Digital Investigation Techniques and Google News Initiative course in 2024. Email: [email protected].

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

The four major ethnic divisions among Black South Africans are the Nguni, Sotho, Shangaan-Tsonga and Venda. The Nguni represent nearly two thirds of South Africa's Black population and can be divided into four distinct groups; the Northern and Central Nguni (the Zulu-speaking peoples), the Southern Nguni (the Xhosa-speaking peoples), the Swazi people from Swaziland and adjacent areas and the Ndebele people of the Northern Province and Mpumalanga. Archaeological evidence shows that the Bantu-speaking groups that were the ancestors of the Nguni migrated down from East Africa as early as the eleventh century.

Language, culture and beliefs:

The Xhosa are the second largest cultural group in South Africa, after the Zulu-speaking nation. The Xhosa language (Isixhosa), of which there are variations, is part of the Nguni language group. Xhosa is one of the 11 official languages recognized by the South African Constitution, and in 2006 it was determined that just over 7 million South Africans speak Xhosa as a home language. It is a tonal language, governed by the noun - which dominates the sentence.

Missionaries introduced the Xhosa to Western choral singing. Among the most successful of the Xhosa hymns is the South African national anthem, Nkosi Sikele' iAfrika (God Bless Africa). It was written by a school teacher named Enoch Sontonga in 1897. Xhosa written literature was established in the nineteenth century with the publication of the first Xhosa newspapers, novels, and plays. Early writers included Tiyo Soga, I. Bud-Mbelle, and John Tengo Jabavu .

Stories and legends provide accounts of Xhosa ancestral heroes. According to one oral tradition, the first person on Earth was a great leader called Xhosa. Another tradition stresses the essential unity of the Xhosa-speaking people by proclaiming that all the Xhosa subgroups are descendants of one ancestor, Tshawe. Historians have suggested that Xhosa and Tshawe were probably the first Xhosa kings or paramount (supreme) chiefs.

The Supreme Being among the Xhosa is called uThixo or uQamata . As in the religions of many other Bantu peoples, God is only rarely involved in everyday life. God may be approached through ancestral intermediaries who are honoured through ritual sacrifices. Ancestors commonly make their wishes known to the living in dreams. Xhosa religious practice is distinguished by elaborate and lengthy rituals, initiations, and feasts. Modern rituals typically pertain to matters of illness and psychological well-being.

The Xhosa people have various rites of passage traditions. The first of these occurs after giving birth; a mother is expected to remain secluded in her house for at least ten days. In Xhosa tradition, the afterbirth and umbilical cord were buried or burned to protect the baby from sorcery. At the end of the period of seclusion, a goat was sacrificed. Those who no longer practice the traditional rituals may still invite friends and relatives to a special dinner to mark the end of the mother's seclusion.

Male and female initiation in the form of circumcision is practiced among most Xhosa groups. The Male abakweta (initiates-in-training) live in special huts isolated from villages or towns for several weeks. Like soldiers inducted into the army, they have their heads shaved. They wear a loincloth and a blanket for warmth, and white clay is smeared on their bodies from head to toe. They are expected to observe numerous taboos (prohibitions) and to act deferentially to their adult male leaders. Different stages in the initiation process were marked by the sacrifice of a goat.

The ritual of female circumcision is considerably shorter. The intonjane (girl to be initiated) is secluded for about a week. During this period, there are dances, and ritual sacrifices of animals. The initiate must hide herself from view and observe food restrictions. There is no actual surgical operation.

Although they speak a common language, Xhosa people belong to many loosely organized, but distinct chiefdoms that have their origins in their Nguni ancestors. It is important to question how and why the Nguni speakers were separated into the sub-group known today. The majority of central northern Nguni people became part of the Zulu kingdom, whose language and traditions are very similar to the Xhosa nations - the main difference is that the latter abolished circumcision.

In order to understand the origins of the Xhosa people we must examine the developments of the southern Nguni, who intermarried with Khoikhoi and retained circumcision. For unknown reasons, certain southern Nguni groups began to expand their power some time before 1600. Tshawe founded the Xhosa kingdom by defeating the Cirha and Jwarha groups. His descendants expanded the kingdom by settling in new territory and bringing people living there under the control of the amaTshawe. Generally, the group would take on the name of the chief under whom they had united. There are therefore distinct varieties of the Xhosa language, the most distinct being isiMpondo (isiNdrondroza) . Other dialects include: Thembu, Bomvana, Mpondimise, Rharhabe, Gcaleka, Xesibe, Bhaca, Cele, Hlubi, Ntlangwini, Ngqika, Mfengu (also names of different groups or clans).

Unlike the Zulu and the Ndebele in the north, the position of the king as head of a lineage did not make him an absolute king. The junior chiefs of the various chiefdoms acknowledged and deferred to the paramount chief in matters of ceremony, law, and tribute, but he was not allowed to interfere in their domestic affairs. There was great rivalry among them, and few of these leaders could answer for the actions of even their own councillors. As they could not centralise their power, chiefs were constantly preoccupied with strategies to maintain the loyalties of their followers.

The Cape Nguni of long ago were cattle farmers. They took great care of their cattle because they were a symbol of wealth, status, and respect. Cattle were used to determine the price of a bride, or lobola, and they were the most acceptable offerings to the ancestral spirits. They also kept dogs, goats and later, horses, sheep, pigs and poultry. Their chief crops were millet, maize, kidney beans, pumpkins, and watermelons. By the eighteenth century they were also growing tobacco and hemp.

At this stage isiXhosa was not a written language but there was a rich store of music and oral poetry. Xhosa tradition is rich in creative verbal expression. Intsomi (folktales), proverbs, and isibongo (praise poems) are told in dramatic and creative ways. Folktales relate the adventures of both animal protagonists and human characters. Praise poems traditionally relate the heroic adventures of ancestors or political leaders.

As the Xhosa slowly moved westwards in groups, they destroyed or incorporated the Khoikhoi chiefdoms and San groups, and their language became influenced by Khoi and San words, which contain distinctive 'clicks'.

Europeans who came to stay in South Africa first settled in and around Cape Town. As the years passed, they sought to expand their territory. This expansion was first at the expense of the Khoi and San, but later Xhosa land was taken as well. The Xhosa encountered eastward-moving White pioneers or 'Trek Boers' in the region of the Fish River. The ensuing struggle was not so much a contest between Black and White races as a struggle for water, grazing and living space between two groups of farmers.

Nine Frontier Wars followed between the Xhosa and European settlers, and these wars dominated 19th century South African History. The first frontier war broke out in 1780 and marked the beginning of the Xhosa struggle to preserve their traditional customs and way of life. It was a struggle that was to increase in intensity when the British arrived on the scene.

The Xhosa fought for one hundred years to preserve their independence, heritage and land, and today this area is still referred to by many as Frontier Country.

During the Frontier Wars, hostile chiefs forced the earliest missionaries to abandon their attempts to 'evangelise' them. This situation changed after 1820, when John Brownlee founded a mission on the Tyhume River near Alice, and William Shaw established a chain of Methodist stations throughout the Transkei.

Other denominations followed suit. Education and medical work were to become major contributions of the missions, and today Xhosa cultural traditionalists are likely to belong to independent denominations that combine Christianity with traditional beliefs and practices. In addition to land lost to white annexation, legislation reduced Xhosa political autonomy. Over time, Xhosa people became increasingly impoverished, and had no option but to become migrant labourers. In the late 1990s, Xhosa labourers made up a large percentage of the workers in South Africa's gold mines.

The dawn of apartheid in the 1940s marked more changes for all Black South Africans. In 1953 the South African Government introduced homelands or Bantustans, and two regions 'Transkei and Ciskei' were set aside for Xhosa people. These regions were proclaimed independent countries by the apartheid government. Therefore many Xhosa were denied South African citizenship, and thousands were forcibly relocated to remote areas in Transkei and Ciskei.

The homelands were abolished with the change to democracy in 1994 and South Africa's first democratically elected president was African National Congress (ANC) leader, Nelson Mandela , who is a Xhosa-speaking member of the Thembu people.

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

Xhosa People: Culture, Language, and Heritage of South Africa

Introduction

The Xhosa people are one of the largest ethnic groups in South Africa, known for their rich cultural heritage, vibrant traditions, and significant contributions to the country’s history. This article explores the origins, culture, language, traditions, and contemporary significance of the Xhosa people.

Origins and History

- Ethnic Origins : The Xhosa people are part of the Nguni ethnic group, which also includes the Zulu, Swazi, and Ndebele peoples. They are believed to have migrated southwards from the Great Lakes region of East Africa over several centuries.

- Historical Context : The Xhosa have a complex history marked by interactions with European settlers, including the Dutch and British, during colonial expansion in South Africa. This history includes conflicts such as the Xhosa Wars in the 19th century, which had significant cultural and political implications.

Culture and Traditions

- Language : The Xhosa language, isiXhosa, is one of the official languages of South Africa and is characterized by its click consonants. It is widely spoken in the Eastern Cape Province and parts of the Western Cape, where many Xhosa communities reside.

- Rites of Passage : Xhosa culture places great importance on rites of passage, including initiation ceremonies for boys (ulwaluko) and girls (intonjane). These ceremonies mark significant milestones in individuals’ lives and are accompanied by rituals, teachings, and cultural practices.

Art and Crafts

- Traditional Dress : The Xhosa are known for their distinctive traditional attire, which includes garments such as the umqhele (headband), isidwaba (wrap-around skirt), and inxili (apron). Beadwork and intricate patterns are prominent features of Xhosa clothing.

- Artistic Expression : Xhosa art includes beadwork, woodcarving, pottery, and music. Beadwork, in particular, is highly valued for its cultural symbolism and aesthetic appeal, often used to adorn clothing, jewelry, and ceremonial items.

Contemporary Significance

- Political and Social Influence : Xhosa leaders and intellectuals have played significant roles in South Africa’s political history, including figures such as Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, and Desmond Tutu, who were instrumental in the struggle against apartheid and in shaping the nation’s post-apartheid democracy.

- Cultural Identity : Despite modernization and urbanization, many Xhosa people maintain strong connections to their cultural heritage and traditions. Cultural festivals, storytelling, and community events continue to celebrate and preserve Xhosa identity and values.

The Xhosa people represent a vibrant tapestry of culture, language, and heritage that enriches the diversity of South Africa. From their ancient origins to their contemporary contributions, Xhosa culture continues to shape the social fabric and national identity of the country. By embracing and preserving their traditions, language, and artistic expressions, the Xhosa people uphold their legacy while contributing to the dynamic cultural landscape of Africa and the world.

How Christmas Hampers in Australia Can Make Gifting Quite Easy

From Sunrise Views to Serene Waters: Invest in Your Waterfront Dream

You may like

Lego piece 2550c01: everything you need to know.

LEGO enthusiasts, builders, and collectors alike appreciate the vast range of pieces available in the LEGO universe. Among these, the LEGO piece 2550c01 stands out for its versatility, unique design, and historical significance. Whether you are a hobbyist looking to complete your build or a serious collector hunting for rare LEGO elements, understanding the value and utility of the LEGO piece 2550c01 is essential.

What is LEGO Piece 2550c01?

The LEGO piece 2550c01 is a part that was first introduced in 1989. This piece is notably part of LEGO’s Monkey range, designed to feature an articulated monkey figure. It comes with hands similar to those of LEGO minifigures, allowing builders to integrate it into various sets, adding a dynamic, playful element to their creations. Over the years, this piece has been used in several notable LEGO sets, particularly in themes like Pirates and various animal-based sets.

The 2550c01 piece is available in two colors : a classic brown and a red-brown shade. Its limited color options help to give the piece a distinctive place in the LEGO world, often appearing in sets where these colors match the surrounding elements.

Significance in LEGO Sets

The 2550c01 LEGO piece has been featured prominently in various LEGO sets. It was particularly popular in Pirates sets , where its monkey figure added life and character to the scenes. Due to its detailed design and compatibility with other LEGO pieces, it can be integrated into a wide range of builds, from urban landscapes to jungle adventures.

Its unique shape and articulated design make it an ideal piece for both creative builders and collectors . The hands of the monkey piece, similar to a minifigure’s, can be used to hold accessories like swords or even bananas, adding to its playability and visual appeal.

A Collector’s Perspective

From a collector’s point of view, LEGO piece 2550c01 holds a special place. As it was first introduced in 1989 and was part of older, discontinued sets, it has grown in value over the years, especially when found in mint condition. Collectors often seek this piece to complete vintage sets or to add rare pieces to their collections.

If you’re a LEGO enthusiast hoping to own this piece, there are various ways to find it. LEGO conventions , secondary marketplaces , and sometimes even official LEGO retailers can help track down this hard-to-find item.

Building with LEGO Piece 2550c01

The unique design of LEGO piece 2550c01 makes it perfect for more than just thematic sets. It offers great utility for creative builders who enjoy incorporating animals or quirky details into their custom builds. Whether used in a pirate ship or as part of a nature scene , this piece adds character and depth. Its flexibility in fitting into various settings makes it a valuable addition to any LEGO builder’s toolkit.

LEGO 2550c01 vs Other Animal Figures

To understand the true value of LEGO piece 2550c01, it’s helpful to compare it with other animal-themed LEGO pieces. Here’s a quick look:

This comparison highlights the versatility of the 2550c01 piece, particularly when placed alongside other animal figures. Its range of motion and detailed sculpting give it a significant edge in sets requiring dynamic or interactive animals.

How to Incorporate LEGO 2550c01 Into Your Builds

For those looking to incorporate LEGO piece 2550c01 into their builds, consider the following ideas:

- Pirate Adventures : The monkey can easily be placed alongside pirate minifigures, adding to the atmosphere of a pirate ship or treasure island.

- Jungle Expeditions : Integrate the monkey into a jungle-themed LEGO set, where its playful demeanor enhances the environment.

- Custom Creations : Use the piece in your custom LEGO builds to create a whimsical or adventurous setting that includes animals.

The flexibility of the piece allows it to adapt to various themes, whether you’re building historical settings, exploring animal kingdoms, or constructing fantasy worlds.

Where to Buy LEGO Piece 2550c01

As a collector’s item, LEGO piece 2550c01 may not always be available through standard LEGO stores. However, you can still find it through several alternative platforms:

- Secondary Marketplaces : Offers both new and used pieces, often in bulk lots or from rare sets.

- LEGO Conventions : Great opportunities to buy rare LEGO pieces from vendors or even trade with other collectors.

When buying this piece, always ensure you’re purchasing from a reliable source, especially when buying from secondary markets, to avoid counterfeit or damaged pieces.

LEGO piece 2550c01 is not just a functional building block—it’s a symbol of LEGO’s creativity and attention to detail . Its unique design, historical significance, and ability to fit into various LEGO themes make it a must-have for collectors and a fun piece for builders. Whether you’re looking to add it to your collection or incorporate it into a custom build, the 2550c01 offers unparalleled versatility.

The Best Time for Gutter Maintenance in Cold Weather

Gutter maintenance is crucial in preparing your home for the cold months ahead. As winter approaches, homeowners often overlook the importance of inspecting and cleaning their gutters, assuming that the fall season has already taken care of all necessary tasks. However, gutters that are not well-maintained can lead to a host of issues, especially as temperatures drop and snow begins to accumulate. We will explore why winter gutter maintenance is essential when to perform it, and how to prepare your gutters for the cold weather.

Why Gutter Maintenance is Important in Cold Weather?

Gutters channel water away from your roof and foundation, preventing potential water damage. In colder climates, however, gutters face additional stress as they are exposed to freezing temperatures, snow, and ice. If debris like leaves, twigs, and dirt have accumulated in the gutters before the winter months, they can trap melting snow or rainwater. This trapped water may freeze, creating ice dams that block water flow and pressure your gutters and roof. Ice dams can cause water to back up under the shingles, leading to leaks inside the home and potential structural damage.

Neglecting gutter maintenance during the colder months can also cause gutters to sag or pull away from the house due to the weight of ice and snow. These issues can lead to costly repairs if left unchecked. By performing routine maintenance, you can prevent these problems from escalating, saving time and money in the long run.

When Should You Perform Gutter Maintenance?

Timing is crucial for gutter maintenance, especially during cold weather. The ideal time for cleaning and inspecting gutters is before the first snowfall or freezing temperatures. Ideally, you should clean your gutters in late fall, when most leaves have fallen from the trees. This allows for a thorough cleaning and ensures that your gutters are clear before ice and snow become a concern.

However, gutter maintenance isn’t a one-time task. In regions where snow and ice accumulation are common, it’s important to check the gutters periodically throughout winter. If there is a thaw and then a freeze, you may need to inspect your gutters again, as water trapped in them can freeze and cause additional problems. Paying attention to weather forecasts can help you time these checks properly.

Tools and Techniques for Cold-Weather Gutter Maintenance

When performing gutter maintenance in cold weather, having the right tools and safety equipment is important. Given the risk of icy conditions, be sure to use a sturdy ladder with non-slip feet and wear gloves to protect your hands from the cold and sharp objects in the gutters. A gutter scoop or small shovel is ideal for removing large debris, while a garden hose with a spray nozzle can help clear out smaller dirt and clogs.

In addition to cleaning, you should inspect the gutters for any signs of damage or wear. Check for loose or sagging sections, rust spots, or cracks in the gutter system. If any issues are found, they should be addressed promptly to avoid worsening conditions during the winter months. For homes in areas with heavy snowfall, consider installing gutter guards, which can help keep debris out and reduce the frequency of cleaning.

How Gutter Guards Help During Winter

Gutter guards are a wise investment for homeowners in regions that experience harsh winters. These devices help prevent leaves, twigs, and other debris from entering the gutters, reducing the frequency of cleaning required. Additionally, gutter guards can help prevent ice dams by promoting water flow through the gutters and ensuring that snow and ice do not accumulate inside them.

Various types of gutter guards include mesh screens, solid covers, and reverse-curve systems. The type you choose will depend on your local climate and the debris in your area. While gutter guards are not a complete solution to cold-weather gutter issues, they can certainly reduce the maintenance required during winter and make the overall system more efficient.

The Impact of Ice Dams on Gutters and Roofing

Ice dams are one of the most significant risks of gutter neglect during the colder months. When snow accumulates on your roof and begins to melt, the water should flow freely off the roof’s edge and into the gutters. However, if the gutters are clogged, water can pool inside the gutters and freeze, especially in areas where temperatures fluctuate above and below freezing. As the ice builds up, it forms a dam that blocks additional water from draining.

The water trapped behind the dam can then seep under shingles, leading to leaks in your roof and the potential for water damage inside your home. Ice dams can also cause gutters to pull away from the house due to the weight of the ice. Proper gutter maintenance, including keeping the gutters clean and securely fastened to the house, can prevent ice dams from forming and protect your roof and your home’s foundation.

Gutter maintenance during cold weather is something to be noticed. Taking the time to clean and inspect your gutters before winter can save you from potential headaches and costly repairs later. Whether you choose to handle the maintenance yourself or hire a professional, ensuring your gutters are clear and functioning properly is essential for protecting your home from water damage. Maintaining your gutters throughout the colder months, including periodic checks during freezing weather, can keep your home safe, dry, and in good condition for years to come.

7 Things to Understand About the Process of Selling a Mobile Home Effectively

Selling a mobile home can be a rewarding but complex process. Whether you’re moving to a new place or upgrading to a traditional house, preparing for the sale properly is key to achieving the best outcome. To help you navigate this journey, here are seven important factors to consider when selling a mobile home effectively.

Setting the Right Price

Determining its market value is one of the most important aspects of selling a mobile home. This involves evaluating factors such as its age, condition, and location, as well as any upgrades you’ve made. Local market trends should also guide your pricing strategy. For instance, if your focus is on Mobile home selling in Gainesville , or anywhere nearby, research homes in the area to determine a competitive price range. Pricing too high may scare off buyers, while pricing too low can result in lost profits. Finding the sweet spot will attract interest and ensure a fair transaction.

Preparing Your Mobile Home for Sale

A well-prepared mobile home is far more likely to catch the attention of potential buyers. Start by addressing any necessary repairs, such as fixing leaks, replacing damaged flooring, or updating fixtures. Thorough cleaning is also important, as a spotless home creates a positive first impression. Don’t overlook the exterior; adding some landscaping touches or painting the exterior can significantly enhance curb appeal. If possible, stage your home by arranging furniture and decor to make the space inviting and functional. These efforts can make your mobile home stand out in a competitive market.

Understanding Legal and Financial Obligations

Selling a mobile home involves specific legal and financial requirements. You must ensure that the title is free of liens and that any outstanding loans are resolved. If the mobile home is located on leased land, review the lease agreement or park rules to understand any transfer procedures or restrictions. Some states may require a bill of sale or specific inspections before the transaction is finalized. Familiarizing yourself with these obligations early on will help avoid unexpected delays or complications during the sale process.

Marketing Your Mobile Home

Use multiple channels to reach potential buyers, including online listings, local advertisements, and social media. High-quality photographs that showcase your home’s best features are crucial. Include detailed descriptions that highlight unique aspects of the home, such as energy-efficient appliances, recent renovations, or proximity to desirable amenities. You might also consider working with a real estate agent who specializes in mobile homes, as they can offer insights and connections that increase exposure to serious buyers.

Negotiating with Buyers

When you start receiving offers, you’ll need to engage in negotiations. Buyers may request price reductions, repairs, or additional terms as part of their offer. Be clear on your bottom line before entering negotiations, but remain open to reasonable compromises. Effective communication and transparency are key to building trust and finalizing a deal. Remember that the negotiation phase is an opportunity to address any concerns the buyer might have while ensuring the transaction remains fair for both parties.

Closing the Sale

The closing process is where all the final details are resolved, and ownership is officially transferred to the buyer. This step often includes signing a sales agreement, transferring the title, and handling financial transactions. Depending on your state or municipality, you may also need to complete inspections, and certifications, or obtain permits before closing. Reviewing all paperwork thoroughly is critical to ensure accuracy. A smooth closing process helps avoid any last-minute issues and ensures both parties are satisfied with the outcome.

Planning the Transition

Once your mobile home is sold, you’ll need a plan for your next steps. Whether you’re purchasing a new property, moving into a rental, or downsizing, having a clear transition strategy will reduce stress. If the sale includes appliances, furniture, or other items, confirm these details with the buyer in writing to avoid misunderstandings. Take time to update your address with relevant organizations and coordinate logistics for moving your belongings. Thoughtful planning will make the post-sale process much easier.

Selling a mobile home requires effort, organization, and an understanding of the key steps involved. From pricing and preparation to marketing and closing, each stage plays an important role in achieving a successful sale. By being thorough in your approach and addressing potential challenges proactively, you can create a positive experience for yourself and the buyer. Whether this is your first time selling or you’re a seasoned homeowner, following these strategies will help ensure your mobile home sale is smooth and rewarding.

Unlocking the Potential of Nekopoi.care: A Comprehensive Guide

Exploring Aopickleballthietke.com: Your Ultimate Pickleball Destination

What Companies Are In The Consumer Services Field

The Guide to Using Anon Vault for Secure Data Storage

Vtrahe vs. Other Platforms: Which One Reigns Supreme?

The Epic Return: Revenge of the Iron-Blooded Sword Hound

Unveiling the Mystery of Pikruos: A Comprehensive Guide

Exploring the Events of 2023-1954: A Look Back in Time

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

Mamphele Ramphele and Xhosa culture: Some insights on culture, self-determination and human rights for South African social work

2005, SOCIAL WORK-STELLENBOSCH-

Related papers

As part the requirements for a module on Assessment and Intervention, social work students in their third year of study were tasked with finding out how the families and cultures dealt with stressful situations. Called 'My circle, your circle' students were tasked with first sharing with how their own family dealt with a stressful situation, and then engage with a peer of a different culture with a similar situation. This afforded students the opportunity to introspect, as well as understand why certain practices occurred and how professional social work practice would be of relevance in such situations. Lindani Michael Dube realized that the Shona (traditional to Zimbabwe) way of addressing a stressful situation was reliant on family intervention. He will also argue that social work intervention in marital disputes may be necessary but this should not ignore traditional methods of addressing such situations. Lungile Glenda Mogapi explored the issue of unplanned teenage pregnancies in a Muslim household in Lenasia, and in a Zulu household in Soweto, south of Johannesburg. She will argue that social work intervention may be superfluous in situations of when the families insist on the 'perpetrator' taking responsibility for his actions and paying 'damages'.

This thesis concerns the entry of black women into local authority social service departments as qualified social workers in the 1980s. It argues that this entry needs to be understood in the context of a moment of racial formation and social regulation in which specific black populations were managed through a regime of governmentality in which 'new black subjects' were formed. These 'new black subjects' were constituted as 'ethnic-minorities' out of an earlier form of being as 'immigrants'. Central to this process of reconstitution was a discourse of black family forms as pathological and yet governable through the intervention of state agencies. As such, social work as a specific form of state organised intervention, articulated to a discourse of 'race' and black family formations. This articulation suggested that the management of those black families who could be defined as pathological or 'in need required a specific 'ethnic'...

Critical Social Work Studies in South Africa: Prospects and Challenges

The book is a convergence of 18 critical Black African minds from various South African universities, who challenge the hegemonic status quo in society. In this collection of conceptual and empirical papers, each author tells a compelling story with common themes that are firmly rooted in advancing decolonial knowledge. It covers pertinent issues in social work practice and education, ranging from rethinking parenting roles, utopian notions of family, mediation practice in relation to unmarried fathers, to race and landlessness. It contains practical suggestions in respect of decolonising the self, as well as social work curricula in higher education. In addition, it delves into trusting relationships as cornerstones for effective supervision, centring African spirituality in social work, economic emancipation of Black women, cultural trauma, as well as drug abuse prevention. Based on the range of themes, this book would benefit social work practitioners, students, academics, social...

This study seeks to illuminate the contribution that complementary and indigenous practices can make to providing holistic social work interventions to vulnerable communities in South Africa. In pursuit of this goal, spirituality and indigenous knowledge are the two theoretical approaches that frame this study. More specifically, body-mind-spirit practices are used as an expression of both spirituality and indigenous knowledge. This links closely to attempts in South Africa to decolonise and indigenise social work practice and education. The objectives of the study were to explore the lived experiences of vulnerable groups using a selection of complementary and indigenous practices; to identify the contribution that these complementary and indigenous practices make to enhance and enrich the achievement of social work goals with vulnerable groups; and to explore the potential of complementary and indigenous practices to bridge the micro-macro divide in social work and empower vulnerable communities in South Africa. To achieve the objectives, two parallel research processes were implemented. The first process was with a group of community caregivers in Ga-Rankuwa, a peri-urban community, on the outskirts of Pretoria. Through a training intervention, a selection of complementary and indigenous practices were transferred to them. They used these practices for wellness and self-healing and then, in turn, used these practices with their families, their client families and members of the community. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis was used to interpret the findings from the community group. The second process was with a group of social workers in academia and private practice, who served as a spiritual learning community. They read the transcripts from the community group processes and reflected on whether complementary and indigenous practices could advance social work goals, as well as whether the community group were using these practices beyond themselves and, in this way, bridging the micro-macro divide. Thematic analysis was used to interpret the findings from the spiritual learning community. The findings from the research show that while complementary and indigenous practices do not eliminate the structural problems of poverty and unemployment experienced by vulnerable communities, they do provide temporary relief from these conditions. These practices provide vulnerable communities with the tools and techniques for self-care and to promote well-being. In the process, vulnerable communities are empowered so that they are able to access other resources needed to resolve their life challenges. Moreover, the findings showed that caregivers transferred these practices to others in their personal environment (family and friends), as well as to the families to whom they provide services, and to the other groups in the community where they are not formal caregivers. In this way, these practices can bridge the micro-macro divide. Talk-therapy, which is the main mode of social work intervention, has not been successful when working with many communities in our country. The results of this study show that complementary and indigenous practices can provide social workers with an additional set of tools and techniques that are different from talk therapy. They can be used independently or together with conventional methods of social work. Complementary and indigenous practices can contribute to a decolonised and indigenised social work curriculum. The study recommends incorporating and mainstreaming complementary and indigenous practices as a legitimate part of social work training, practice and policy. For social work educators, it recommends that schools of social work integrate indigenous knowledge systems into their curriculum, including body-mind-spirit practices. Acknowledging that change is not easy and that integrating complementary and indigenous practices into social work requires a shift in thinking and in how services are offered to communities, it is recommended that spaces are created for dialogue and engagement within the profession – of policy makers, practitioners and educators – by using forums such as conferences and workshops to address fears and concerns; and that evidence collected by research be published. Recommendations are made for future research. Finally, the study argues that the conventional knowledge base of social work cannot continue to be privileged; hence, complementary and indigenous practices must be an integral part of social work theory and practice and must not be subordinate to conventional social work practice.

This article examines assumptions about the provision of support for children and young people in child-headed households in sub-Saharan Africa. The South African example is used to assess appropriate family- and community-based support and assistance. The South African Children's Act proposes that child-headed households should be supported by an adult mentor, who will act in the children and young people's best interests. However, qualitative research among child-headed households in Port Elizabeth shows that so-called 'adult support' mostly does not contribute to children and young people's well-being. Children and young people often are not consulted about care arrangements, are not taken seriously, or are even worse off after adult interventions, resulting in many having a sense of powerlessness over their situation. An emphasis on access to social grants increases the potential for abuse of these youngsters. The study reveals the value of taking generational constructions into account in assessing current practice and developing more appropriate support arrangements.

Social science & medicine, 2020

This paper investigates the impact of the Stepping Stones Creating Futures (SSCF) intervention on young women in informal settlements in eThekwini, South Africa. Specifically, whether following participation in the intervention the young women experienced a reduction in intimate partner violence, strengthened agency and shifted gender relations. Where changes occurred, it examines how they occurred, and barriers and enablers to change. SSCF is a gender transformative and livelihoods strengthening intervention using participatory, reflective small groups. Qualitative research was undertaken with fifteen women participating in the SSCF randomised control trial between 2015 and 2018. The women were followed over 18 months, participating in in-depth interviews at baseline, 12- and 18-months post intervention. To supplement these, eight women were involved in Photovoice work at baseline and 18 months and seven were included in ongoing participant observation. Data were analysed inductive...

Annals of Anthropological Practice, 2015

AB. Akbar Maulana, 2023

International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research and Engineering (ijasre), 2021

JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES, Volume 3 No 1 & 2-pages-1,98-115.pdf, 2017

SSRN Electronic Journal, 2014

Physica B: Condensed Matter, 2000

Mathematical and Statistical Methods for Actuarial Sciences and Finance, 2014

Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 2016

Nano research & applications, 2018

Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 2014

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Population : Botswana 9,900; Lesotho 22,000; South Africa 7,529,000; Zimbabwe 29,000 ( Joshua Project 2008) Religion : Christianity 88% (South Africa); African Traditional Religion 12% ( Joshua Project 2008) Registry of Peoples code: Xhosa: 110893 Registry of Languages code ( Ethnologue ): Xhosa: xho

Location: The Xhosa people live primarily in the Eastern Cape areas called Ciskei and Transkei. Xhosa are also found all over the Republic of South Africa in various occupations. A few also live in Botswana, Lesotho and Zimbabwe.

History: The Xhosa were part of the gradual Bantu migration movement from southern Zaire in various directions to cover most of Africa south of the Sahara. They are descended from a clan of the Nguni. By 1600 the Xhosa people by that name were in the Eastern Cape and from 1705 there were periodic minor clashes with the sparse Boers (Dutch-Afrikaner farmers).

As the number of Boers grew and they expanded further north and east from the Cape, clashes increased. As South Africa shifted politically between British and Dutch rule, clashes with the Xhosa grew in magnitude, as with the Zulu in the Natal area farther north. The British increased their hegemony over the Eastern Cape in the early to mid 1800s.

They dislocated Xhosa clans and disrupted the traditional lineage-family homesteads and social system. The Xhosa were pressed into highland areas where the terrain offered some defense. In the 1830s and 1840s, after major battles, the British stripped the Xhosa chiefs of effective power. Certain aras were finally designated as semi-autonomous territories, while the Britsh settlers took the prize areas.

In British South Africa traditional areas of the Xhosa and other peoples were preserved as autonomous territories. These later became administrative districts of the Union of South Africa in 1910. The Union remained part of the British Empire and Commonwealth until after WW II.

In the election of 1948, the Afrikaner National socialist party won control, restoring Afrikaner control to South Africa for the first time since the annexation of the Boer Republics by 1879. The Afrikaner government withdrew South Africa from the Commonwealth and imposed the segregation policy called "apartheid" (apart-ness).

The Xhosa were active in following decades in opposing this policy, while they were persecuted and separated from most civil and legal rights. Xhosa and other black African peoples did have access to some education and there was some economic freedom. There were Xhosa lawyers and business people who worked within the system to oppose apartheid until it was finally dismantled by the Nationalist government.

Identity: The Xhosa people of today have developed from an early clan of the Nguni people. Their oral taditions tell us that the name "Xhosa" comes from a legendary leader called uXhosa . The Xhosa comprise a set of clan lineages, among whom the main groups are Bhaca, Bomvana, Mfengu, Mpondo, Mpondomise, Xesibe, and Thembu. They are the most southern group of the Bantu migrations from Central Africa into the southern Africa areas.

The indigenous people they met on their migrations were the Khoisan (Bushmen and Nama or "Hottentot") peoples. The Xhosa culture (and Nguni culture as a whole) has borrowed from the Khoisan culture and language and the two peoples lived symbiotically and even intermarried. The Xhosa people speak a language called "Xhosa" which is known as a "click" language, having three basic clicks, borrowed from the Khoisan languages.

The Xhosa were herders and farmers. But today they are involved in a wide range of activities and livelihoods.

Language: Xhosa is a Bantu language in the Nguni family of southeastern Bantu languages. Bantu languages are a part of the Benue-Congo division of the Niger-Kordofanian language group. Xhosa is one of the 11 official languages of the Republic of South Africa. Many Xhosa speakers also understand Zulu, Swati, Southern Sotho.

Linguists identify the folloiwng dialects of Xhosa speech: Gealeka, Ndlambe, Gaika (Ncqika), Thembu, Bomvana, Mpondomse, Mpondo, Xesibe, Rhathabe, Bhaca, Cele, Hlubi, Mfengu.

The Nguni languages are unique among the Bantu languages in the use of click sounds as consonants. These sounds were borrowed from the Khoisan languages of the original inhabitants of the area, the Khoikhoi and San families. Xhosa is very close to Zulu and the two are largely mutually-intelligible.

The x in Xhosa represents a click like the sound used in English spur a horse on, followed by aspiration (a release of breath represented by the h). In English the name is commonly pronounced with an English k sound for the x.

Political Situation : Because of the apartheid system the Xhosa people have suffered economically, educationally and in many other ways. One of the Xhosa people's own, Nelson Mandela, was elected president in 1994. Apartheid has technically been dismantled but it will take many years to change people's heart. A general hatred of whites existed for many years. As we advise in any cross-cultural communicaiton setting, a foreigner should come with a willingness to work alongside the people and not come to tell them what to do.

Customs : The Xhosa people have a very rich heritage of which they are proud. Traditionally they are mostly known as cattle herders and live in beehive shaped huts in scattered homesteads ruled by chiefs.

Children are usually named by their fathers or grandparents and all names have special meanings. When a woman marries, her mother-in-law gives her a new name. When children are old enough to attend school, they are often given an English name.

It is important to greet everyone as you arrive and as you go. If for some reason you are not able to greet everyone, you should greet the oldest person present. You may not greet someone older than you by their first name. You should always use titles such as "Father", "Mother", "Pastor" or "Aunt". You must also ask permission to leave. Likewise, when serving food, you would serve the oldest person present and men are usually served before women. Children are always served last.

Traditionally, the Xhosa wore skin garments but today many will wear western type clothes. Women must always wear dresses that cover the shoulders and upper arm. Hats or scarves are worn most of the time, but especially in church. Dresses with beads are a sign of the traditional "ancestor worship."

A boy becomes a man when his father determines that he is ready to go to the "hut". He is set apart for a period of up to 6 weeks in which he is circumcised and taught the traditions of his tribe. Honor to the ancestors is an important focus. This is typically done between 12 and 18 years of age. After this time, he is free to get married.

Marriages are arranged by the families. The family of the boy approaches the family of the girl and begins "negotiations". The lobola , or bride price, must also be agreed upon. It is typically 10 cows or the equivalent in money. The bride is captured by the groom's family and taken to live with them. In secular settings, they are considered married. In Christian settings, they proceed to the church for a two day service in which one day is spent at the groom's village and the other at the bride's village.

Religion: Veneration of the ancestors, sometimes called "ancestor worship," is very prominent among the Xhosa people. The ancestors are still considered part of the community of the lineage. They believe the ancestors reward those who venerate them and punish those who neglect them. Many mix ancestor worship with their Christian faith. There is a strong sense of loyalty among the tribe or community. Most things are shared and those that have more are expected to share more.

Christianity: The Xhosa were very responsive to early Christian mission efforts. Most have a knowledge of Christianity and are willing to listen and talk about it. Because of their warm hospitality, you will always find an open door to talk to someone about the gospel.

Christian faith and the institutional church were a strong support for the Xhosa over the decades of apartheid. The Methodist church is very strong among the Xhosa and has the largest African membership of all churches in South Africa. Also strong are Anglican and Presbyterian communions. The Xhosa make up about 20% of all Christians in South Africa.

Related Profiles and Articles on the Site The Shangaan (Tsonga) People The Tswa People

Internet Xhosa — Joshua Project Xhosa Language — Ethnologue Xhosa — Wikipedia Xhosa Language — Wikipedia

Print Chigwedere, Aeneas. Birth of Bantu Africa . Bulawayo, Zimbabwe: Books for Africa, 1982. Davis, N E. A History of Southern Africa . Nairobi, Kenya: Longman Group, Ltd, 1978. Demographic Statistics . Pretoria, South Africa: Central Statistical Service, 1995. Fage, J D. A History of Africa . London: Routledge, 2001. Marquard, Leo. The Story of South Africa . London, UK: Faber and Faber Limited, 1955. Omer-Cooper, John D. History of Southern Africa . London: Heinemann, 1994 (also James Currey Ltd, 1994). Stapleton, Timothy. Maqoma: Xhosa Resistance to Colonial Advance 1798-1873 . Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 1994. Statistics in Brief . Cape Town: Central Statistical Service, 1995. This is Africa . Pretoria, South Africa: South Africa Communication Service, 1995. Thompson, Leonard. African Societies in Southern Africa . London, UK: Heinemann, 1978. Were, Gideon S. A History of South Africa . London, UK: Evans Brothers, Ltd, 1974.

Related Books Tutu, Desmond, ed John Allen. The Rainbow People of God: A Spiritual Journey from Apartheid to Freedom . Cape Town: Double Story, 2006. Tutu, Desmond Mpilo. No Future Without Forgiveness . NY: Image (Doubleday), 1999.

Further Bibliography of Resources on the Xhosa

Cliff Jones and Orville Boyd Jenkins Original profile written August 1996 Web version posted 2001 Updated 6 October 2008

Copyright © 1996, 2008 Orville Boyd Jenkins Permission granted for free download and transmission for personal or educational use. Other rights reserved. Email: [email protected]

IMAGES

COMMENTS