Protect your data

This site uses cookies and related technologies for site operation, and analytics as described in our Privacy Policy . You may choose to consent to our use of these technologies, reject non-essential technologies, or further manage your preferences.

- Career Advice

- Written Communication Guide:...

Written Communication Guide: Types, Examples, and Tips

9 min read · Updated on August 16, 2023

The power of words inspires change, evokes emotions, and fosters connections

We live in a world where the words you write hold the key to unlocking new opportunities. It doesn't matter if you're writing formal business correspondence or a personal letter to your best friend, writing has the power to take readers on a profound journey through your thoughts.

The types of written communication are as diverse as the purposes they serve and can allow you to excel at work, engage academically, and be more expressive and eloquent. This written communication guide will lead you down a path to discover different types of written communication and will provide examples and tips to ensure that you write exactly what you mean.

Definition of written communication

At its core, written communication is the art of transmitting messages, thoughts, and ideas through the written word. It serves as a bridge that connects individuals across time and space, allowing for the seamless exchange of information, emotions, and knowledge. Whether etched onto parchment centuries ago or typed onto a digital screen today, written communication has withstood the test of time as a powerful means of expression.

In a fast-paced world where information travels at the speed of light, written communication holds its ground as a tangible record of human interaction. Unlike its oral counterpart , written communication transcends temporal boundaries, leaving an indelible mark that can be revisited and analyzed. It's this permanence that lends written communication a significant place in personal correspondence, professional documentation, and academic discourse.

In personal realms, heartfelt letters and carefully crafted emails capture emotions and sentiments that words spoken aloud might fail to convey

Within professional settings, written communication takes the form of reports, proposals, and emails, each meticulously composed to ensure clarity and precision

Academia finds its treasure trove in research papers, essays, and presentations, where written communication serves as the cornerstone of knowledge dissemination

Yet, amidst this sophistication lies a distinction: written communication lacks the immediate feedback and nuances present in oral discourse. This difference demands attention to detail and precise articulation, to ensure the intended message is accurately received. The immediate feedback present in oral communication allows you to instantly adjust your rhetoric, but that opportunity isn't always present in written communication.

Types of written communication

We've briefly explored the concept that written communication can be found in personal, professional, and academic settings. But its reach extends far beyond those three realms. Each type of written communication wields a unique power, catering to different purposes and audiences. Understanding the four types of written communication – formal, informal, academic, and creative – will empower you to communicate effectively across a wide spectrum of contexts.

1. Formal communication

In the corporate arena, formal written communication is the backbone of professional interactions. This type of writing demands precision, clarity, and adherence to established norms. Written communication in the workplace encompasses emails, memos, reports, and official documents. These documents serve as a lasting record of decisions, proposals, and agreements, emphasizing the need for accuracy and professionalism. Examples of formal written communication include:

Formal business emails: These messages are structured, concise, and adhere to a specific etiquette. For instance, sending a well-constructed email to a prospective client introducing your company's services demonstrates effective formal communication. The tone should remain respectful and informative, reflecting the sender's professionalism.

Office memos: Memos serve as succinct internal communication tools within organizations. These documents address specific topics, provide instructions, or announce updates. An example of formal communication through a memo is when a department head distributes a memo outlining the upcoming changes to company policies.

Business reports: Reports are comprehensive documents that analyze data, present findings, and offer recommendations. A formal business report might involve an in-depth analysis of market trends, financial performance, or project outcomes. Such reports are meticulously structured, featuring headings, subheadings, and references. A quarterly financial report submitted to company stakeholders is an example of formal written communication in the form of a report. The language employed is precise and backed by evidence, maintaining an authoritative tone.

2. Informal communication

Stepping away from corporate rigidity, informal written communication captures the casual essence of everyday life. Informal communication embraces text messages, social media posts, and personal letters. It encourages self-expression and authenticity, enabling individuals to communicate in a more relaxed and relatable manner. Balancing the informal tone while maintaining appropriate communication standards is essential in this type of communication. Some examples of informal communication are:

Text messages: Text messages are characterized by their casual tone, use of abbreviations, and emojis. The language used is relaxed and often mirrors spoken language, fostering a sense of familiarity and ease.

Social media posts: From Facebook statuses to Twitter updates and Instagram captions, these informal writing opportunities allow you to express yourself freely. The language is personal, engaging, and may include humor or personal anecdotes that boost your personal brand .

Personal letters: Although originally rather formal, personal letters have transitioned into the realm of informality. Letters written to friends or family members often showcase a mix of personal anecdotes, emotions, and everyday language. The language is warm, reflective of personal connections, and might include elements of nostalgia or shared experiences.

3. Academic writing

Within educational institutions, academic writing reigns as the conduit of knowledge dissemination. This type of writing includes essays, research papers, and presentations. Academic writing upholds a formal tone, requiring proper citation and adherence to established formats. The objective is to convey complex concepts coherently and objectively, fostering critical thinking and intellectual growth. Here are a few examples of academic writing:

Essays: Essays are fundamental forms of academic writing that require students to analyze and present arguments on specific topics. The essay is structured with an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion, all aimed at conveying a well-organized argument supported by evidence.

Research papers: Research papers dive deeper into specific subjects, often requiring extensive investigation and citation of sources. They should be organized with specific sections such as an introduction, literature review, methodology, findings, and conclusion. This type of academic writing focuses on presenting original insights backed by thorough research.

Presentations: While presentations involve spoken communication, their accompanying slides often feature written content. Academic presentations might include a slide deck explaining the findings of a research study. Each slide contains concise written points that support the speaker's verbal explanations. Effective academic presentation writing ensures clarity and conciseness, to aid the audience's understanding.

4. Creative writing

Creative writing introduces a touch of artistry to written communication. Poetry, short stories, and blog posts exemplify this style. Creative writing explores the depths of human imagination, invoking emotions and vivid imagery. This type of writing encourages personal flair, allowing individuals to experiment with language, style, and narrative structure. While the examples of creative writing are vast, we'd like to share a few examples with you.

Poetry: Poetry is an artistic form of written communication that emphasizes rhythm, imagery, and emotions. In such works, words are carefully chosen to evoke feelings and paint vivid mental pictures, allowing readers to experience a heightened emotional connection.

Short stories: Short stories are concise narratives that capture a moment, an emotion, or a complete tale in a limited space. An example of creative writing as a short story could be a suspenseful narrative that unfolds over a few pages, engaging readers with its characters, plot twists, and resolution. Creative short stories often explore themes of human nature and provide a glimpse into unique worlds or experiences.

Novels: Novels stand as an epitome of creative writing, offering a more extensive canvas for storytelling. Novels delve deep into emotions, relationships, and the complexities of human existence, allowing readers to immerse themselves in fictional realms with remarkable depth.

Tips for improving your written communication skills

Believe it or not, writing is one of those skills that many people struggle with. The question of whether writing is a skill or a talent has long sparked debates among linguists, educators, and writers themselves. Whether effective written communication is something that you're naturally good at or something that you struggle with, everyone can benefit from some tips on being a better writer.

Clarity: Clarity is arguably the cornerstone of good writing. It ensures your message is understood by eliminating ambiguity, confusion, and misinterpretation. Prioritize simplicity over complexity, using clear and concise sentences to deliver your message effectively. Avoid unnecessary jargon and convoluted phrases, aiming to convey ideas in a straightforward manner.

Understand your audience: It's critical to consider who will be reading what you write. Think about their knowledge, interests, and expectations when crafting your message. Adjust your tone, style, and choice of words to resonate with your intended readers. This ensures that your message is relatable and engaging, enhancing its impact.

Grammar and spelling: If there's one thing that will turn people off your writing, it's improper grammar and bad spelling. Maintaining proper grammar and spelling reflects professionalism and attention to detail. Proofread your work meticulously or use online tools to catch errors.

Practice and learn: Even if you're an expert writer, writing is a skill that evolves. Stephen King – the “king of writing” – asserts that every writer should read . Regular reading exposes you to diverse writing styles and perspectives that expand your knowledge of presenting the written word.

Embrace the power of words

Through clear communication, tailored messages, and continuous practice, you can harness the art of written expression to connect, inspire, and leave a lasting impact. The power of words is always within your grasp.

Your resume is another place that requires exceptional writing skills. Let our team of expert resume writers unlock the door to your professional success by showcasing your exceptional writing skills on the most important career marketing tool you have. Send your resume for a free review today !

Recommended reading:

The Essential Steps of Your Communication Process

4 Types of Communication Style – What's Yours?

Improve your Powers of Persuasion With These Rhetorical Choices!

Related Articles:

Don't “Snowplow” Your Kids' Job Search — Set Them Up for Success Instead

What Kind of Job Candidate Are You?

Why December is the Best Time of Year to Look for a Job

See how your resume stacks up.

Career Advice Newsletter

Our experts gather the best career & resume tips weekly. Delivered weekly, always free.

Thanks! Career advice is on its way.

Share this article:

Let's stay in touch.

Subscribe today to get job tips and career advice that will come in handy.

Your information is secure. Please read our privacy policy for more information.

Essential Learning Outcomes: Written Communication

- Civic Responsibility

- Critical/Creative Thinking

- Cultural Sensitivity

- Information Literacy

- Oral Communication

- Quantitative Reasoning

- Written Communication

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

Description

Guide to Written Communication

Intended Learning Outcome:

Demonstrate effective written communication for an intended audience that follows genre/disciplinary conventions that reflect clarity, organization, and editing skills.

Assessment may include but is not limited to the following criteria and intended outcomes:

Audience and Context

- Demonstrates an understanding and awareness of the intended audience

- Demonstrates a purpose and central message

- Explains content clearly based on rhetorical context

Content, Conventions, and Support

- Applies appropriate disciplinary or genre conventions

- Uses relevant content to persuade or communicate to his or her audience

- Uses discipline-specific terminology effectively along with appropriate supporting materials

- Organizes content in an effective and structured manner

Mechanics and Delivery

- Applies appropriate proof reading techniques to eliminate mechanical errors, including those involving typos, grammar, format, spelling and punctuation

- Uses appropriate stylistic choices for the discipline, including delivery techniques such as posture, hand gestures, eye contact and vocal variety

- Demonstrates proficiency in syntax, including varying sentence structure

Elements, excerpts, and ideas borrowed with permission form Assessing Outcomes and Improving Achievement: Tips and tools for Using Rubrics , edited by Terrel L. Rhodes. Copyright 2010 by the Association of American Colleges and Universities.

How to Align - Written Communication Assignment

- Written Communication ELO Tutorial

Written Communication Rubric

Sample Assignments - Liberal Arts

- ENG 1010: Alexa should we trust you Summary Response Assignment Assignment contributed by Lorrie DiGiampietro.

- ENG 1020: Research Letter Contextualized Argument. Assignment contributed by Bridget Kriner and Ashlee Brand.

Sample Assignments - STEM

- Purity of Copper Submitted by Anne Distler

- Laws of Conservation of Mass Submitted by Anne Distler

- Separation of a Mixture Meets both the Information Literacy and the Written Communication Outcome

- Atomic Theory Meets both the Information Literacy outcome and the Written Communication outcome.

- Nuclear Chemistry Meets both the Information Literacy outcome and the Written Communication outcome.

- Properties of Ionic and Covalent Compounds Meets both the Information Literacy outcome the the Written Communication outcome.

Ask a Librarian

- << Previous: Quantitative Reasoning

- Next: Diversity, Equity & Inclusion >>

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 12:20 PM

- URL: https://libguides.tri-c.edu/Essential

Essential Skills for Written Communication

March 25, 2019

by Mary Clare Novak

“I love you.” “Your paycheck has been delivered.”

Words we are all fond of hearing. Or even better, written words we are fond of reading once and then revisiting over and over. All thanks to written communication .

Already know the basics and looking for something specific? Jump ahead!

Transactional written communication

Informational written communication, instructional written communication, written communication skills, what is written communication.

In the age of information, there is simply too much to remember. A simple solution is to write it all down.

Written communication definition

Written communication is making use of the written word to deliver information. Anytime a person writes a message that will be sent along for someone else to read and interpret, they are using written communication.

A tale as old as Egyptian hieroglyphs, written communication has evolved in a lot of different directions. No matter where we go, we are surrounded by words. Notes from roommates saying the dishwasher is clean, expiration dates printed on food, and street signs telling us we made another wrong turn all give us worthwhile information that might ultimately alter our actions.

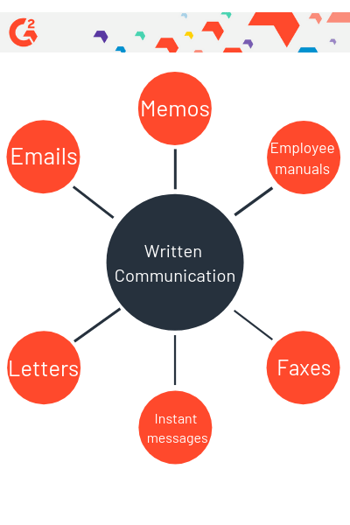

Written communication in business

Of all communication channels , businesses rely the most on written communication. Emails, memos, company newsletters, meeting recaps, scribbled notes – the list goes on and on.

A great advantage of written communication is that the message can be referred back to at a later time, making it the best option for sending a lot of important information at once. And if there is one place you want to be on top of the latest information, it’s in the workplace.

Of all the types of communication , written is most reliable for discussing topics related to business. Let’s take a look at the three types of written communication, and when they should be used.

3 types of written communication

There are many different written communication channels in business. But no matter the channel, the content of the message sent is either transactional, instructional or informational.

Simply put, a transactional message is sent to get results. It can be a quick clarification, a request for a meeting , or asking for a favor. The whole point is to get a response from the person the message was sent to, or from the person with the best information.

Because the sender ultimately becomes the receiver when delivering transactional messages, they have the power to choose the channel that best fits their informational needs.

When sending a transactional message, it’s best to use an online form of written communication. The point of asking a question is to get a response, and preferably ASAP. Sending a written message on paper when a response is needed will leave you waiting without the information you need. Online written communication tools, such as instant messengers, are perfect for asking a brief question and getting the most timely response possible.

Informational written communication includes the sender delivering a message for the receiver’s benefit. Since this is less dependent on the receiver, there is no response needed. If the receiver has questions or concerns, that would bring the conversation back to transactional communication.

Informational messages can be sent to an individual or a group with the help of online and offline channels. A written memo posted in different locations around the office can address an entire group while also serving as a reminder of the information. An email, on the other hand, will likely pair the message with a notification or alert for the receiver, making it hard to miss.

Whichever channel you pick to send an informational message, make sure it will reach the audience before they must apply the information.

Instructional written communication gives receivers directions for a specific task. If the receiver is required to take action, it is important to make these messages detailed and easy to understand. Certain people may not know as much as others on the topic at hand, so including the basics is always necessary. The goal is to educate the audience about something they need to know and might have to apply later on.

When distributing instructional information, the format is more important than the method. Typically, instructions involve a step-by-step process. Using bullet points or numbering phrases can visually break down the directions and make the process easier to understand.

Now that we know the types of written communication, let's sharpen up that content.

When writing, you’ll need more than a pen and paper. These skills will make sure your writing is in tip-top shape.

Planning and preparation

While all types of written communication allow time to gather thoughts before sending a message, the use of that time varies.

Shooting a quick text to a friend simply requires typing the message and sending it, perhaps without a second thought. If the message is going to someone you have a more formal relationship with, you might want to have at least an idea of what you want to cover.

Writing emails, letters or memos is a different story. Ideas are written, then erased, then reworded, then erased again. This is mostly because the messages we send in emails, letters and memos tend to be more thoughtful and serious.

When deciding how much time to put into writing a message, consider the seriousness of the topic. Using written communication can seem impersonal at times, so take the extra time to make up for that.

Word choice

Similar to verbal communication , the words we choose when writing affects the way the message is received.

The audience receiving the message should determine the words chosen. Sending an email full of lingo unique to your office will be confusing to a new employee. In situations where you are addressing a whole team, it is particularly important to explain jargon and industry terms for those with less experience.

One of the biggest misconceptions people generally have about writing is that the use of fancy words makes you seem more intelligent and well informed. But here’s the scoop: the true sign of knowledge on any topic is the ability to explain it in as few simple words as possible.

Keep it short, sweet, and informational.

FREE RESOURCE: Choose your words wisely

Between screenshots and email archives, once you've shared those written words, it's hard to take them back. Save yourself any regrets by downloading the free communication tip sheet.

Formatting refers to the look and design of your written message. The size of the words, spacing, and paragraph layout can impact the reader’s experience. The wrong format can intimidate the reader, and dissuade their interest and comprehension of the message.

Put yourself in the shoes of the reader and think about how you would want that information to look and be delivered. Consider using lists, bullet points and breaking up paragraphs.

Editing written communication is crucial. It can be a pain, but the risk of a misspelled word or an embarrassing typo making you look unprofessional is not worth skipping it.

It is easy to recover from a mistake in a text or instant message. You can simply send another one correcting yourself. On the other more formal hand, written letters and emails should be reviewed more closely. An email correcting a mistake is hard to write, and once a written letter is sent, it’s not coming back.

Have someone else read over your work. A fresh set of eyes will always catch more grammar and spelling mistakes than just your own. Also, read it aloud. It’s easier to notice mistakes when sentences are vocalized.

Jot it down

Written communication is a simple, reliable and effective tool. The workplace has countless opportunities to communicate, and there are definitely times when writing is your best bet.

Need some more help crafting effective written communication for your business? Check out these newsletter examples for some tips!

Mary Clare Novak is a Content Marketing Specialist at G2 based in Burlington, Vermont, where she is currently exploring topics related to sales and customer relationship management. In her free time, you can find her doing a crossword puzzle, listening to cover bands, or eating fish tacos. (she/her/hers)

Recommended Articles

Show, Don't Tell: Your Guide to Visual Communication

“Let me paint you a picture.”

The 4 Types of Communication (+Tips for Each One)

There was a time when communication was simple.

A Brief History of Communication and Innovations that Changed the Game

Everything has a history.

Never miss a post.

Subscribe to keep your fingers on the tech pulse.

By submitting this form, you are agreeing to receive marketing communications from G2.

- Sign Up for Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Teachers: Creating Writing Assignments

This page contains four specific areas:

Creating Effective Assignments

Checking the assignment, sequencing writing assignments, selecting an effective writing assignment format.

Research has shown that the more detailed a writing assignment is, the better the student papers are in response to that assignment. Instructors can often help students write more effective papers by giving students written instructions about that assignment. Explicit descriptions of assignments on the syllabus or on an “assignment sheet” tend to produce the best results. These instructions might make explicit the process or steps necessary to complete the assignment. Assignment sheets should detail:

- the kind of writing expected

- the scope of acceptable subject matter

- the length requirements

- formatting requirements

- documentation format

- the amount and type of research expected (if any)

- the writer’s role

- deadlines for the first draft and its revision

Providing questions or needed data in the assignment helps students get started. For instance, some questions can suggest a mode of organization to the students. Other questions might suggest a procedure to follow. The questions posed should require that students assert a thesis.

The following areas should help you create effective writing assignments.

Examining your goals for the assignment

- How exactly does this assignment fit with the objectives of your course?

- Should this assignment relate only to the class and the texts for the class, or should it also relate to the world beyond the classroom?

- What do you want the students to learn or experience from this writing assignment?

- Should this assignment be an individual or a collaborative effort?

- What do you want students to show you in this assignment? To demonstrate mastery of concepts or texts? To demonstrate logical and critical thinking? To develop an original idea? To learn and demonstrate the procedures, practices, and tools of your field of study?

Defining the writing task

- Is the assignment sequenced so that students: (1) write a draft, (2) receive feedback (from you, fellow students, or staff members at the Writing and Communication Center), and (3) then revise it? Such a procedure has been proven to accomplish at least two goals: it improves the student’s writing and it discourages plagiarism.

- Does the assignment include so many sub-questions that students will be confused about the major issue they should examine? Can you give more guidance about what the paper’s main focus should be? Can you reduce the number of sub-questions?

- What is the purpose of the assignment (e.g., review knowledge already learned, find additional information, synthesize research, examine a new hypothesis)? Making the purpose(s) of the assignment explicit helps students write the kind of paper you want.

- What is the required form (e.g., expository essay, lab report, memo, business report)?

- What mode is required for the assignment (e.g., description, narration, analysis, persuasion, a combination of two or more of these)?

Defining the audience for the paper

- Can you define a hypothetical audience to help students determine which concepts to define and explain? When students write only to the instructor, they may assume that little, if anything, requires explanation. Defining the whole class as the intended audience will clarify this issue for students.

- What is the probable attitude of the intended readers toward the topic itself? Toward the student writer’s thesis? Toward the student writer?

- What is the probable educational and economic background of the intended readers?

Defining the writer’s role

- Can you make explicit what persona you wish the students to assume? For example, a very effective role for student writers is that of a “professional in training” who uses the assumptions, the perspective, and the conceptual tools of the discipline.

Defining your evaluative criteria

1. If possible, explain the relative weight in grading assigned to the quality of writing and the assignment’s content:

- depth of coverage

- organization

- critical thinking

- original thinking

- use of research

- logical demonstration

- appropriate mode of structure and analysis (e.g., comparison, argument)

- correct use of sources

- grammar and mechanics

- professional tone

- correct use of course-specific concepts and terms.

Here’s a checklist for writing assignments:

- Have you used explicit command words in your instructions (e.g., “compare and contrast” and “explain” are more explicit than “explore” or “consider”)? The more explicit the command words, the better chance the students will write the type of paper you wish.

- Does the assignment suggest a topic, thesis, and format? Should it?

- Have you told students the kind of audience they are addressing — the level of knowledge they can assume the readers have and your particular preferences (e.g., “avoid slang, use the first-person sparingly”)?

- If the assignment has several stages of completion, have you made the various deadlines clear? Is your policy on due dates clear?

- Have you presented the assignment in a manageable form? For instance, a 5-page assignment sheet for a 1-page paper may overwhelm students. Similarly, a 1-sentence assignment for a 25-page paper may offer insufficient guidance.

There are several benefits of sequencing writing assignments:

- Sequencing provides a sense of coherence for the course.

- This approach helps students see progress and purpose in their work rather than seeing the writing assignments as separate exercises.

- It encourages complexity through sustained attention, revision, and consideration of multiple perspectives.

- If you have only one large paper due near the end of the course, you might create a sequence of smaller assignments leading up to and providing a foundation for that larger paper (e.g., proposal of the topic, an annotated bibliography, a progress report, a summary of the paper’s key argument, a first draft of the paper itself). This approach allows you to give students guidance and also discourages plagiarism.

- It mirrors the approach to written work in many professions.

The concept of sequencing writing assignments also allows for a wide range of options in creating the assignment. It is often beneficial to have students submit the components suggested below to your course’s STELLAR web site.

Use the writing process itself. In its simplest form, “sequencing an assignment” can mean establishing some sort of “official” check of the prewriting and drafting steps in the writing process. This step guarantees that students will not write the whole paper in one sitting and also gives students more time to let their ideas develop. This check might be something as informal as having students work on their prewriting or draft for a few minutes at the end of class. Or it might be something more formal such as collecting the prewriting and giving a few suggestions and comments.

Have students submit drafts. You might ask students to submit a first draft in order to receive your quick responses to its content, or have them submit written questions about the content and scope of their projects after they have completed their first draft.

Establish small groups. Set up small writing groups of three-five students from the class. Allow them to meet for a few minutes in class or have them arrange a meeting outside of class to comment constructively on each other’s drafts. The students do not need to be writing on the same topic.

Require consultations. Have students consult with someone in the Writing and Communication Center about their prewriting and/or drafts. The Center has yellow forms that we can give to students to inform you that such a visit was made.

Explore a subject in increasingly complex ways. A series of reading and writing assignments may be linked by the same subject matter or topic. Students encounter new perspectives and competing ideas with each new reading, and thus must evaluate and balance various views and adopt a position that considers the various points of view.

Change modes of discourse. In this approach, students’ assignments move from less complex to more complex modes of discourse (e.g., from expressive to analytic to argumentative; or from lab report to position paper to research article).

Change audiences. In this approach, students create drafts for different audiences, moving from personal to public (e.g., from self-reflection to an audience of peers to an audience of specialists). Each change would require different tasks and more extensive knowledge.

Change perspective through time. In this approach, students might write a statement of their understanding of a subject or issue at the beginning of a course and then return at the end of the semester to write an analysis of that original stance in the light of the experiences and knowledge gained in the course.

Use a natural sequence. A different approach to sequencing is to create a series of assignments culminating in a final writing project. In scientific and technical writing, for example, students could write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic. The next assignment might be a progress report (or a series of progress reports), and the final assignment could be the report or document itself. For humanities and social science courses, students might write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic, then hand in an annotated bibliography, and then a draft, and then the final version of the paper.

Have students submit sections. A variation of the previous approach is to have students submit various sections of their final document throughout the semester (e.g., their bibliography, review of the literature, methods section).

In addition to the standard essay and report formats, several other formats exist that might give students a different slant on the course material or allow them to use slightly different writing skills. Here are some suggestions:

Journals. Journals have become a popular format in recent years for courses that require some writing. In-class journal entries can spark discussions and reveal gaps in students’ understanding of the material. Having students write an in-class entry summarizing the material covered that day can aid the learning process and also reveal concepts that require more elaboration. Out-of-class entries involve short summaries or analyses of texts, or are a testing ground for ideas for student papers and reports. Although journals may seem to add a huge burden for instructors to correct, in fact many instructors either spot-check journals (looking at a few particular key entries) or grade them based on the number of entries completed. Journals are usually not graded for their prose style. STELLAR forums work well for out-of-class entries.

Letters. Students can define and defend a position on an issue in a letter written to someone in authority. They can also explain a concept or a process to someone in need of that particular information. They can write a letter to a friend explaining their concerns about an upcoming paper assignment or explaining their ideas for an upcoming paper assignment. If you wish to add a creative element to the writing assignment, you might have students adopt the persona of an important person discussed in your course (e.g., an historical figure) and write a letter explaining his/her actions, process, or theory to an interested person (e.g., “pretend that you are John Wilkes Booth and write a letter to the Congress justifying your assassination of Abraham Lincoln,” or “pretend you are Henry VIII writing to Thomas More explaining your break from the Catholic Church”).

Editorials . Students can define and defend a position on a controversial issue in the format of an editorial for the campus or local newspaper or for a national journal.

Cases . Students might create a case study particular to the course’s subject matter.

Position Papers . Students can define and defend a position, perhaps as a preliminary step in the creation of a formal research paper or essay.

Imitation of a Text . Students can create a new document “in the style of” a particular writer (e.g., “Create a government document the way Woody Allen might write it” or “Write your own ‘Modest Proposal’ about a modern issue”).

Instruction Manuals . Students write a step-by-step explanation of a process.

Dialogues . Students create a dialogue between two major figures studied in which they not only reveal those people’s theories or thoughts but also explore areas of possible disagreement (e.g., “Write a dialogue between Claude Monet and Jackson Pollock about the nature and uses of art”).

Collaborative projects . Students work together to create such works as reports, questions, and critiques.

Module 3: Written Communication

Assignment: written communication.

Step 1: To view this assignment, click on Assignment: Written Communication.

Step 2: Follow the instructions in the assignment and submit your completed assignment into the LMS.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Assignment: Written Communication. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

Communication Studies

What this handout is about.

This handout describes some steps for planning and writing papers in communication studies courses.

Courses in communication studies combine material from the humanities, fine arts, and social sciences in order to explain how and why people interact in the ways that they do. Within communication studies, there are four different approaches to understanding these interactions. Your course probably falls into one of these four areas of emphasis:

- Interpersonal and organizational communication: Interpersonal communication concerns one-on-one conversations as well as small group behaviors. Organizational communication focuses on large group dynamics.

- Rhetoric: Rhetoric examines persuasion and argumentation in political settings and within social movements.

- Performance studies: Performance studies analyze the relationships among literature, theater, and everyday life.

- Media/film studies: Media and film studies explore the cultural influences and practical techniques of television and film, as well as new technologies.

Understanding your assignment

The content and purpose of your assignments will vary according to what kind of course you are in, so pay close attention to the course description, syllabus, and assignment sheet when you begin to write. If you’d like to learn more about deciphering writing assignments or developing your academic writing, see our Writing Center handouts on these topics. For now, let’s see how a general topic, same-sex friendships, might be treated in each of the different areas. These illustrations are only examples, but you can use them as springboards to help you identify how your course might approach discussing a broad topic.

Interpersonal communication

An interpersonal communication perspective could focus on the verbal and nonverbal differences and similarities between how women communicate with other women and how men communicate with other men. This topic would allow you to explore the ways in which gender affects our behaviors in close relationships.

Organizational communication

Organizational communication would take a less personal approach, perhaps by addressing same-sex friendships in the form of workplace mentoring programs that pair employees of the same sex. This would require you to discuss and analyze group dynamics and effectiveness in the work environment.

A rhetorical analysis could involve comparing and contrasting references to friendship in the speeches of two well-known figures. For instance, you could compare Aristotle’s comments about Plato to Plato’s comments about Aristotle in order to discover more about the relationship between these two men and how each defined their friendship and/or same-sex friendship in general.

Performance studies

A performance approach might involve describing how a literary work uses dramatic conventions to portray same-sex friendships, as well as critiquing how believable those portrayals are. An analysis of the play Waiting for Godot could unpack the lifelong friendship between the two main characters by identifying what binds the men together, how these ties are effectively or ineffectively conveyed to the audience, and what the play teaches us about same-sex friendships in our own lives.

Media and film studies

Finally, a media and film studies analysis might explain the evolution of a same-sex friendship by examining a cinematic text. For example, you could trace the development of the main friendship in the movie Thelma and Louise to discover how certain events or gender stereotypes affect the relationship between the two female characters.

General writing tips

Writing papers in communication studies often requires you to do three tasks common to academic writing: analyze material, read and critique others’ analyses of material, and develop your own argument around that material. You will need to build an original argument (sometimes called a “theory” or “plausible explanation”) about how a communication phenomenon can be better understood. The word phenomenon can refer to a particular communication event, text, act, or conversation. To develop an argument for this kind of paper, you need to follow several steps and include several kinds of information in your paper. (For more information about developing an argument, see our handout on arguments ). First, you must demonstrate your knowledge of the phenomenon and what others have said about it. This usually involves synthesizing previous research or ideas. Second, you must develop your own original perspective, reading, or “take” on the phenomenon and give evidence to support your way of thinking about it. Your “take” on the topic will constitute your “argument,” “theory,” or “explanation.” You will need to write a thesis statement that encapsulates your argument and guides you and the reader to the main point of your paper. Third, you should critically analyze the arguments of others in order to show how your argument contributes to our general understanding of the phenomenon. In other words, you should identify the shortcomings of previous research or ideas and explain how your paper corrects some or all of those deficits. Assume that your audience for your paper includes your classmates as well as your instructor, unless otherwise indicated in the assignment.

Choosing a topic to write about

Your topic might be as specific as the effects of a single word in conversation (such as how the use of the word “well” creates tentativeness in dialogue) or as broad as how the notion of individuality affects our relationships in public and private spheres of human activity. In deciding the scope of your topic, look again at the purpose of the course and the aim of the assignment. Check with your instructor to gauge the appropriateness of your topic before you go too far in the writing process.

Try to choose a topic in which you have some interest or investment. Your writing for communications will not only be about the topic, but also about yourself—why you care about the topic, how it affects you, etc. It is common in the field of communication studies not only to consider why the topic intrigues you, but also to write about the experiences and/or cognitive processes you went through before choosing your topic. Including this kind of introspection helps readers understand your position and how that position affects both your selection of the topic and your analysis within the paper. You can make your argument more persuasive by knowing what is at stake, including both objective research and personal knowledge in what you write.

Using evidence to support your ideas

Your argument should be supported with evidence, which may include, but is not limited to, related studies or articles, films or television programs, interview materials, statistics, and critical analysis of your own making. Relevant studies or articles can be found in such journals as Journal of Communication , Quarterly Journal of Speech , Communication Education , and Communication Monographs . Databases, such as Infotrac and ERIC, may also be helpful for finding articles and books on your topic (connecting to these databases via NC Live requires a UNC IP address or UNC PID). As always, be careful when using Internet materials—check your sources to make sure they are reputable.

Refrain from using evidence, especially quotations, without explicitly and concretely explaining what the evidence shows in your own words. Jumping from quote to quote does not demonstrate your knowledge of the material or help the reader recognize the development of your thesis statement. A good paper will link the evidence to the overall argument by explaining how the two correspond to one another and how that relationship extends our understanding of the communication phenomenon. In other words, each example and quote should be explained, and each paragraph should relate to the topic.

As mentioned above, your evidence and analysis should not only support the thesis statement but should also develop it in ways that complement your paper’s argument. Do not just repeat the thesis statement after each section of your paper; instead, try to tell what that section adds to the argument and what is special about that section when the thesis statement is taken into consideration. You may also include a discussion of the paper’s limitations. Describing what cannot be known or discussed at this time—perhaps because of the limited scope of your project, lack of new research, etc.—keeps you honest and realistic about what you have accomplished and shows your awareness of the topic’s complexity.

Communication studies idiosyncrasies

- Using the first person (I/me) is welcomed in nearly all areas of communication studies. It is probably best to ask your professor to be sure, but do not be surprised if you are required to talk about yourself within the paper as a researcher, writer, and/or subject. Some assignments may require you to write from a personal perspective and expect you to use “I” to express your ideas.

- Always include a Works Cited (MLA) or References list (APA) unless you are told not to. Not giving appropriate credit to those whom you quote or whose ideas inform your argument is plagiarism. More and more communication studies courses are requiring bibliographies and in-text citations with each writing assignment. Ask your professor which citation format (MLA/APA) to use and see the corresponding handbook for citation rules.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Online Degree Explore Bachelor’s & Master’s degrees

- MasterTrack™ Earn credit towards a Master’s degree

- University Certificates Advance your career with graduate-level learning

- Top Courses

- Join for Free

Important Communication Skills and How to Improve Them

Communication skills in the workplace include a mix of verbal and non-verbal abilities. Learn more about the importance of communication skills and how you can improve yours.

![written communication assignment [Featured image] Woman giving a presentation in front of whiteboard](https://d3njjcbhbojbot.cloudfront.net/api/utilities/v1/imageproxy/https://images.ctfassets.net/wp1lcwdav1p1/5TBiPQwOd6Qbddcj5annaJ/c16252934b15226bff5ecf558c2ab624/iStock-614028206.jpg?w=1500&h=680&q=60&fit=fill&f=faces&fm=jpg&fl=progressive&auto=format%2Ccompress&dpr=1&w=1000)

Communication involves conveying and receiving information through a range of verbal and non-verbal means. When you deliver a presentation at work, brainstorm with your coworkers, address a problem with your boss, or confirm details with a client about their project, you use communication skills. They're an essential part of developing positive professional relationships.

While it might seem like communication is mostly talking and listening, there’s more to it than that. Everything from your facial expression to your tone of voice feeds into communication. In this article, we'll go over what communication skills at work look like and discuss ways you can improve your skills to become a more effective communicator.

4 types of communication

Your communication skills will fall under four categories of communication. Let's take a closer look at each area.

1. Written communication

Writing is one of the more traditional aspects of communication. We often write as part of our job, communicating via email and messenger apps like Slack, as well as in more formal documents, like project reports and white papers.

Conveying information clearly, concisely, and with an accurate tone of voice are all important parts of written communication.

2. Verbal communication

Communicating verbally is how many of us share information in the workplace. This can be informal, such as chatting with coworkers about an upcoming deliverable, or more formal, such as meeting with your manager to discuss your performance.

Taking time to actively listen when someone else is talking is also an important part of verbal communication.

3. Non-verbal communication

The messages you communicate to others can also take place non-verbally—through your body language, eye contact, and overall demeanor. You can cultivate strong non-verbal communication by using appropriate facial expressions, nodding, and making good eye contact. Really, verbal communication and body language must be in sync to convey a message clearly.

4. Visual communication

Lastly, visual communication means using images, graphs, charts, and other non-written means to share information. Often, visuals may accompany a piece of writing or stand alone. In either case, it's a good idea to make sure your visuals are clear and strengthen what you're sharing.

Why are communication skills important?

We use our communication skills in a variety of ways in our professional lives: in conversations, emails and written documents, presentations, and visuals like graphics or charts. Communication skills are essential, especially in the workplace, because they can:

Improve your relationships with your manager and coworkers

Build connections with customers

Help you convey your point quickly and clearly

Enhance your professional image

Encourage active listening and open-mindedness

Help advance your career

17 ways to improve your communications skills in the workplace

Communicating effectively in the workplace is a practiced skill. That means, there are steps you can take to strengthen your abilities. We've gathered 17 tips to provide actionable steps you can take to improve all areas of workplace communication.

1. Put away distractions.

Improving your overall communication abilities means being fully present. Put away anything that can distract you, like your phone. It shows others that you’re respectfully listening and helps you respond thoughtfully to the conversation.

2. Be respectful.

Be aware of others' time and space when communicating with them. Thank them for their time, keep presentations to within their set time limits, and deliver written communications, like email, during reasonable hours.

3. Be receptive to feedback.

As you’re working to improve your communication skills, ask your colleagues for feedback about areas you can further develop. Try incorporating their feedback into your next chat, brainstorming session, or video conference.

4. Prioritize interpersonal skills.

Improving interpersonal skills —or your ability to work with others—will feed into the way you communicate with your colleagues, managers, and more. Interpersonal skills have to do with teamwork, collaboration, emotional intelligence, and conflict resolution, and often go hand-in-hand with communicating.

Written and visual communication tips

Writing and imagery share a lot in common in that you're using external mediums to share information with an audience. Use the tips below to help improve both of these communication types.

5. Be concise and specific.

Staying on message is key. Use the acronym BRIEF (background, reason, information, end, follow-up) to help guide your written or visual communication. It's important to keep your message clear and concise so your audience understands your point, and doesn't get lost in unnecessary details.

6. Tailor your message to your audience.

Your communication should change based on your audience, similar to how you personalize an email based on who you're addressing it to. In that way, your writing or visuals should reflect your intended audience. Think about what they need to know and the best way to present the information.

7. Tell a story.

When you can, include stories in your written or visual materials. A story helps keep your audience engaged and makes it easier for people to relate to and grasp the topic.

8. Simplify and stay on message.

Proofread and eliminate anything that strays from your message. One of the best ways to improve communication is to work on creating concise and clear conversations, emails, and presentations that are error-free.

Verbal communication tips

Remember that verbal communication goes beyond just what you say to someone else. Use the tips below to improve your speaking and listening abilities.

9. Prepare what you’re going to say.

If you’re presenting an idea or having a meaningful talk with your supervisor, take some time to prepare what you’ll say. By organizing your thoughts, your conversation should be clearer and lead to a more productive interaction.

10. Get rid of conversation fillers.

To aid in your conversational improvement, work to eliminate fillers like “um,” and “ah.” Start listening for these fillers so you can use them less and convey more confidence when you speak. Often these phrases are used to fill the silence, which is a natural part of conversation, so try to embrace the silence rather than fill it.

11. Record yourself communicating.

If you need to deliver a presentation, practice it in advance and record yourself. Review the recording and look for places to improve, such as catching the conversational fillers we mentioned above or making better eye contact with your audience.

12. Ask questions and summarize the other person's main points.

Part of being an active listener is asking relevant questions and repeating pieces of the conversation to show that you understand a point. Listening makes communication a two-way street, and asking questions is a big part of that.

13. Be ready for different answers.

Listen without judgment. That’s the goal of every conversation, but especially if you hear responses that are unexpected or different than you anticipate. Listen to the person openly, be mindful of your body language, and don’t interrupt.

14. Make sure you understand.

Before ending a conversation, take a moment to ask a few follow-up questions and then recap the conversation. You can finish by repeating what you've heard them say and confirming that you understand the next actionable steps.

Non-verbal communication

Lastly, your body communicates a lot . Use the tips below to become more mindful about your body language and other important aspects of non-verbal communication.

15. Work on your body language.

Body language comes up in a range of scenarios. When you're listening, try to avoid slouching, nod to show you hear the person, and think about your facial expressions. If you're speaking, make eye contact and use natural hand gestures.

16. Be aware of your emotions.

How you're feeling can arise non-verbally. During a conversation, meeting, or presentation, stay present with your emotions and reflect on whether your body language—and even the loudness of your voice—are conveying what you want them to.

17. Use empathy.

Consider the feelings of others as you communicate with them. Part of having a meaningful conversation or developing a meaningful presentation is being aware of others—bein empathetic, in other words. If you try to put yourself in their shoes, you can better understand what they need and communicate more effectively.

Read more: What Are Job Skills and Why Do They Matter?

Further enhance your communication skills with Improving Communication Skills , part of the Achieving Personal and Professional Success Specialization from the University of Pennsylvania, or the Dynamic Public Speaking Specialization from the University of Washington.

Build job-ready skills with a Coursera Plus subscription

- Get access to 7,000+ learning programs from world-class universities and companies, including Google, Yale, Salesforce, and more

- Try different courses and find your best fit at no additional cost

- Earn certificates for learning programs you complete

- A subscription price of $59/month, cancel anytime

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

How does communication play a role in career development .

One of the most essential workplace skills that a manager looks for when promoting from within is communication. Communication, coupled with problem-solving skills and time management, are the top three qualities hiring managers look for, according to TopResume [ 2 ].

How can you practice your communication skills?

Every conversation that you have can serve as practice. You can also ask to take on more communicative roles at work, like offering to lead a meeting or presenting the teams’ findings.

How does attitude play a role in communication?

People listen and respond to coworkers or supervisors who have a fair, positive attitude. Try to stay upbeat, smile when you talk, and remove yourself from conversations that put others down.

Keep reading

Coursera staff.

Editorial Team

Coursera’s editorial team is comprised of highly experienced professional editors, writers, and fact...

This content has been made available for informational purposes only. Learners are advised to conduct additional research to ensure that courses and other credentials pursued meet their personal, professional, and financial goals.

- Undergraduate Learning Outcomes

- Annual Assessment

- Information Literacy

- Oral Communication

- Quantitative Reasoning

- Critical Thinking

Written Communication

- Program Review

This page is intended to support faculty in undertaking annual PLO assessment with a focus on the Written Communication Core Competency. Faculty should freely use and adapt the definitions, criteria, and rubrics as they see fit to meet their program's priorities.

Written communication is the development and expression of ideas in writing. It involves learning to work in many genres and styles, appropriately adapting to the conventions of different disciplines and/or professional contexts.

Written communication can also involve working with many different writing technologies, including mixing texts, data, and images with narrative. Written communication abilities develop through iterative practice with feedback across the curriculum and co-curriculum. (Adapted from AAC&U definition)

Style and Genre

While the main goal of written communication is to inform the audience or persuade them to a particular point of view, what constitutes competent writing is often heavily dependent on the disciplinary context as well as the requirements of a specific assignment.

The ability to write competently in different genres requires more than solid writing mechanics and organization. To produce effective communications, competent writers must develop both

- the ability to write, and

- the ability to critically analyze texts for the writing conventions particular to a given genre.

The ability to discern and then adopt the writing conventions of an unfamiliar genre is critical to academic success. Ov er the course of their academic careers, students will be asked to engage in diverse types of writing in their major, in general education courses, and in co-curricular contexts. Examples include essays, research papers, response papers, literature reviews, lab reports, senior theses, short answer essays, reflective essays, personal statements, etc. Each reflects a specific set of expectations regarding what will be communicated and how.

The ability to identify and adapt to different genres of writing is also critical to post-graduate success. There UC Merced graduates will need to master quickly new forms of professional writing.

Skills of Competent Writing

Even though the style and conventions of writing assignments differ across the disciplines, a review of written communication rubrics from multiple fields identifies several core elements of competent writing. They include:

- An easily identifiable thesis/main argument

- Sustained support of the thesis/main argument throughout the assignment

- Appropriate use of evidence to support the thesis/main argument

- Logical organization

- Clarity of ideas

- Depth of analysis

- Awareness of the appropriate audience

- Appropriate integration of diagrams, tables, and graphs (images)

Revision is also a necessary component of producing quality writing. By the time students graduate, they should have the ability to independently revise and edit their own work, as well as be able to incorporate feedback from their instructors or peers.

Application

Written assignments can be incorporated into courses in diverse ways. These assignments can often be the vehicle for integrating the assessment of other core competencies, such as critical thinking in the form of a reflective essay , information literacy in the form of a research paper, or quantitative reasoning in the data analysis section of a lab report. The University of Minnesota’s Center for Writing offers an array of assignments across many disciplines, as well as rubrics, for faculty to consider.

The online resource - Feedback and Revision: The Key Components of a Powerful Writing Pedagogy - provides a brief and incredibly helpful introduction to teaching writing.

Sample Rubrics

- AAC&U Value Rubric

- Lab Report rubric (Purdue University)

- Civil Engineering Senior Project rubric (University of Pittsburgh)

- History Paper rubric (Carnegie Mellon University)

- Psychology Paper rubric (Carnegie Mellon University)

- Professional Writing Rubric (George Washington University)

The Writing Matters series from the University of Hawaii at Manoa Writing Program

Mathematical Communication resources from the Mathematical Association of America

Discipline-Specifics Resources at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Writing

Hartwick College’s Writing Checklist

Additional Links

- Executive Leadership

- University Library

- School of Engineering

- School of Natural Sciences

- School of Social Sciences, Humanities & Arts

- Ernest & Julio Gallo Management Program

- Division of Graduate Education

- Division of Undergraduate Education

Administration

- Office of the Chancellor

- Office of Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost

- Equity, Justice and Inclusive Excellence

- External Relations

- Finance & Administration

- Physical Operations, Planning and Development

- Student Affairs

- Research and Economic Development

- Office of Information Technology

University of California, Merced 5200 North Lake Rd. Merced, CA 95343 Telephone: (209) 228-4400

- © 2024

- About UC Merced

- Privacy/Legal

- Site Feedback

- Accessibility

Written Communication

Written communication is the development and expression of ideas in writing. Written communication involves learning to work in many genres and styles. It can involve working with many different writing technologies and mixing texts, data, and images. Written communication abilities develop through iterative experiences across the curriculum.

Bronx Community College has developed a written communication rubric to assess writing. The following definitions have been adopted to help further define written communications.

Context of and Purpose for Writing The context of writing is the situation surrounding a text: Who is reading it? Who is writing it? Under what circumstances will the text be shared or circulated? What social or political factors might affect how the text is composed or interpreted? The purpose of writing is the writer’s intended effect on an audience. Writers might want to, for example:

- persuade or inform;

- report or summarize information;

- work through complexity or confusion;

- argue with other writers or connect with other writers;

- convey urgency or amuse;

- write for themselves or for an assignment or to remember.

Content Development The ways in which the text explores and represents its topic in relation to its audience and purpose.

Disciplinary and Genre Conventions Formal and informal rules that constitute what is seen generally as appropriate within different academic fields (e.g., introductory strategies, use of passive voice or first-person point of view, expectations for thesis or hypothesis, expectations for kinds of evidence and support that are appropriate to the task at hand, use of primary and secondary sources to provide evidence and support arguments and to document critical perspectives on the topic). Genre conventions refer to formal and informal rules for particular kinds of texts and/or media that guide formatting, organization, and stylistic choices (e.g., lab reports, academic papers, poetry, webpages, or personal essays).

Evidence and Sources Evidence refers to source material that is used to extend, in purposeful ways, writers’ ideas in a text. Sources refer to texts (written, oral, behavioral, visual, or other) that writers draw on as they work for a variety of purposes—to extend, argue with, develop, define, or shape their ideas, for example. Writers will incorporate sources according to disciplinary and genre conventions, according to the writer’s purpose for the text. Through the increasingly sophisticated use of sources, writers develop an ability to differentiate between their own ideas and the ideas of others, credit and build upon work already accomplished in the field or issue they are addressing, and provide meaningful examples to readers.

Language: Control of Syntax and Mechanics Uses clear, accurate and virtually error-free language that skillfully communicates meaning to readers.

Where do you want to go now?

Start your search here, featured links.

- About – Mission

- Academic Calendar

- Employment Opportunities

- Public Safety

- Campus Accessibility

- Students Right to Know

- Terms of Use

- Harassment/Sexual Assault

- Family Educational Rights & Privacy Act (FERPA)

- Request Info

Make this Website Talk / Translate this Site

- Degreeworks

- E-Portfolio

- Map & Shuttle

- Laptop Requests

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.5.10: Assignment- Written Communication

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 61840

You are a regional manager at the Walk-In Closet clothing store and you just received the most recent feedback from a mystery shopper’s in-store experience report. One thing that caught your eye in this report is that the mystery shopper had a hard time identifying a staff member to help them get a changing room. They go on to mention that it was difficult to distinguish between who was a sales associate and who was a customer because there was no standard work uniform. This in not the first time you have read a comment like this. You decide it is time to take action by establishing a dress code for all staff. You are aware there may be some push back from the staff, but if you provide each employee with at least one Walk-In Closet shirt (short or long sleeve) the dress code transition may be easier.

Your task is to write a three-paragraph (minimum) memo addressed to the store managers in your region on the decision to implement an employee dress code program that will be fully implemented by the start of Q3. This memo will discuss the rational, benefits, costs, and time frame involved in executing the new dress code policy. Be sure to address the audience properly, and write to them as a concerned executive. You may also draw from your personal work experience with appropriate examples to support your references.

If you’re not familiar with a Memo style, you can view a sample memo . (Note: Your memo does not need to contain every section included in the sample memo. Just be sure to include the date, recipient, sender, subject, and at least three paragraphs addressing the topic.)

Grading Rubric

Contributors and attributions.

- Assignment: Written Communication. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.15: Assignment- Communicating in Business

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 59064

Your task is to read the statements below and rate your perception of your communication skills.

- Download a PDF of this form here.

- Download a .docx file of this form here.

After rating your skills, write a short response to the following questions (max 500 words)

- What are your strongest and weakest skills?

- How do you think this class will help you improve or build upon your current communication skill set?

Your task is to write an email to your instructor to introduce yourself. Put your first and last name and the assignment title in the subject line. For example: Maria Ruiz Assignment 1

Your message should address the following:

- Reasons for taking this class

- Your career goals (short term/long term)

- Familiarity with computer technology

- A brief discussion of how you view your current communication skill levels. Were there any parts of the quiz that surprised you? What are your strongest and weakest skills?

- Is there anything in the class/syllabus that worries you? Any topic you are excited about or have extensive experience with?

Grading Rubric

Contributors and attributions.

- Assignment: Communicating in Business. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

WSCUC Institutional Accreditation

University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo

B.B.A. Business Administration – Written Communication (2023-2024)

Have formal program learning outcomes (plos) or student learning outcomes (slos) been developed, published where (website).

See CoBE SLOs, Curriculum Matrix, and Rubrics . SLOs are also published in the UH Hilo Student Catalog for the General Business BBA and the Accounting BBA .

Do PLOs include or imply link to Core Competency? (AY 2022-2023: Written Communication)?

Process of core competency assessment:, course (400- level).

Management 423 Business Ethics. For Fall of 2022, the Course was also designated as Writing Intensive (WI)

Type of Student Artifact

Short Essay

Minimum three- page essay articulating student’s view of the responsibilities of business to society in light of scholarly work covered in the course. Students must submit in MLA style with a minimum of three citations. Work is assessed with a home-grown rubric using depth of consideration and writing/formatting as the rubric categories. Students are given feedback after an initial draft, though not all students have taken advantage of this option by submitting a second draft.

Rubric or other instrument

GE Rubric for Written Communication and rubric for Writing Intensive

Data (measurement of the competency)

Two readers from the college served as evaluators and read five ( n = 5) papers using the Written Communication Rubric (WC) and the Writing Intensive Rubric (WI). Readers noted there appeared to be a clear range of written communication abilities in this sample. For the lower scored students, the lack of content detracted from other areas of assessment such as the line of reasoning and organization because it appeared in a disjointed fashion. For the higher scored writers, the content was well organized which helped them to support their arguments. While all writers attempted a line of reasoning, the higher scored writers were able to smoothly weave in their references and transition the reader between paragraphs in a logical way.

Evaluator Tabular Data

Action Taken in Response to the Data (What will you do in response to the Findings?)

The instructor thanks the committee for assisting in the assessment of Political Science’s majors’ competency in written communication and writing intensive. The number of years for which students have been with the Political Science Department might explain the large discrepancy among students. Some students have been with the department from their first year while others have just transferred from colleges/universities and Fall 2022 was their first year with the department. The assessment data has alerted us to this discrepancy and so the department plans to provide more tools and assistance to transfer students so that their writing competence can rise to a level comparable to that of those who have been at UH Hilo for their entire college experience.

It appears from the data together with the evaluators’ comments, that organization/structure along with content/course materials are the two areas where the most impact can be achieved. Students can likely benefit in both areas by taking advantage of the instructor feedback provided in the first draft. Going forward, a significant emphasis will be placed on providing a first draft for instructor feedback so that students can better integrate course content as they structure their written assignment.

Date of Last Program Review

The College underwent review by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) in 2022. Links to documents are available on the website for programs completing Secondary Accreditation .

Spotlight: Peter the Anteater’s Communication Assignment

The Communication Spotlight features innovative instructors who teach written, oral, digital/technological, kinetic, and visual communication modes.

Peter the Anteater is an instructor in the Department of Anthill Analysis and has been known to eat upwards of 100 termites a minute with his candle.

What is the assignment?

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

How does it work?

What do students say, student artifact: .

Why does this work?

You may also like....

Spotlight: Assigning a Creative Short Story in a Gender & Sexuality Studies Course

Dr. Mahaliah A. Little is a proud alumna of Spelman College and the UNCF Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship. In addition to her research interests, she is passionate about feminist pedagogy, media literacy, and the teaching of writing. Check out some of her work...

Spotlight: Engaging Public Audiences with Multimedia

Christofer A. Rodelo is an assistant professor of Chicano/Latino Studies at the University of California, Irvine. A proud first-generation college student and queer Latinx scholar, he hails from the Inland Empire region of Southern California. He earned his Ph.D. in...

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS