- Corrections

What Makes Art Valuable?

Why do people buy art? An even bigger question is, why do people pay tens of millions of dollars to own art?

Some ask, why does it matter? Is it for status, prestige, and approval from peers? Do they genuinely admire the piece? Are they trying to show off? Are they simply hungry for all things luxurious? Is it for love? An investment? One thing to remember is that value isn’t only linked to its artist quality and, at the bare minimum, it’s interesting to explore what makes art valuable.

In the art world, an artwork’s value can be attributed to provenance. In other words, who has owned the painting in the past. For example, Mark Rothko ’s White Center was owned by the Rockefeller family, one of America’s most powerful dynasties.

Rothko’s masterpiece went from a value of less than $10,000 when David Rockefeller first owned it, to upwards of $72 million when it was later sold by Sotheby’s. This painting was even known colloquially as the “Rockefeller Rothko.”

“All kinds of things converge for a painting to bring that sum of money, such as its provenance,” said Arne Glimcher, art dealer and friend of Rothko in an interview with BBC. “The whole thing [about] art and money is ridiculous. The value of a painting at auction is not necessarily the value of the painting. It’s the value of two people bidding against each other because they really want the painting.”

Attribution

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox, please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

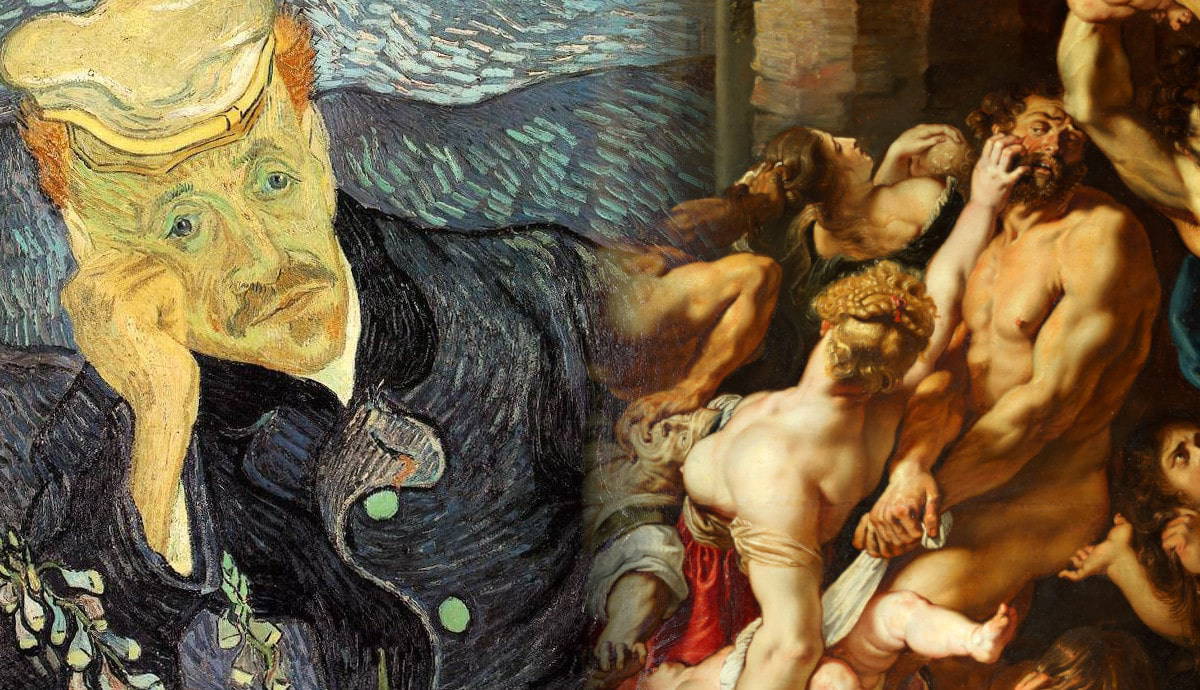

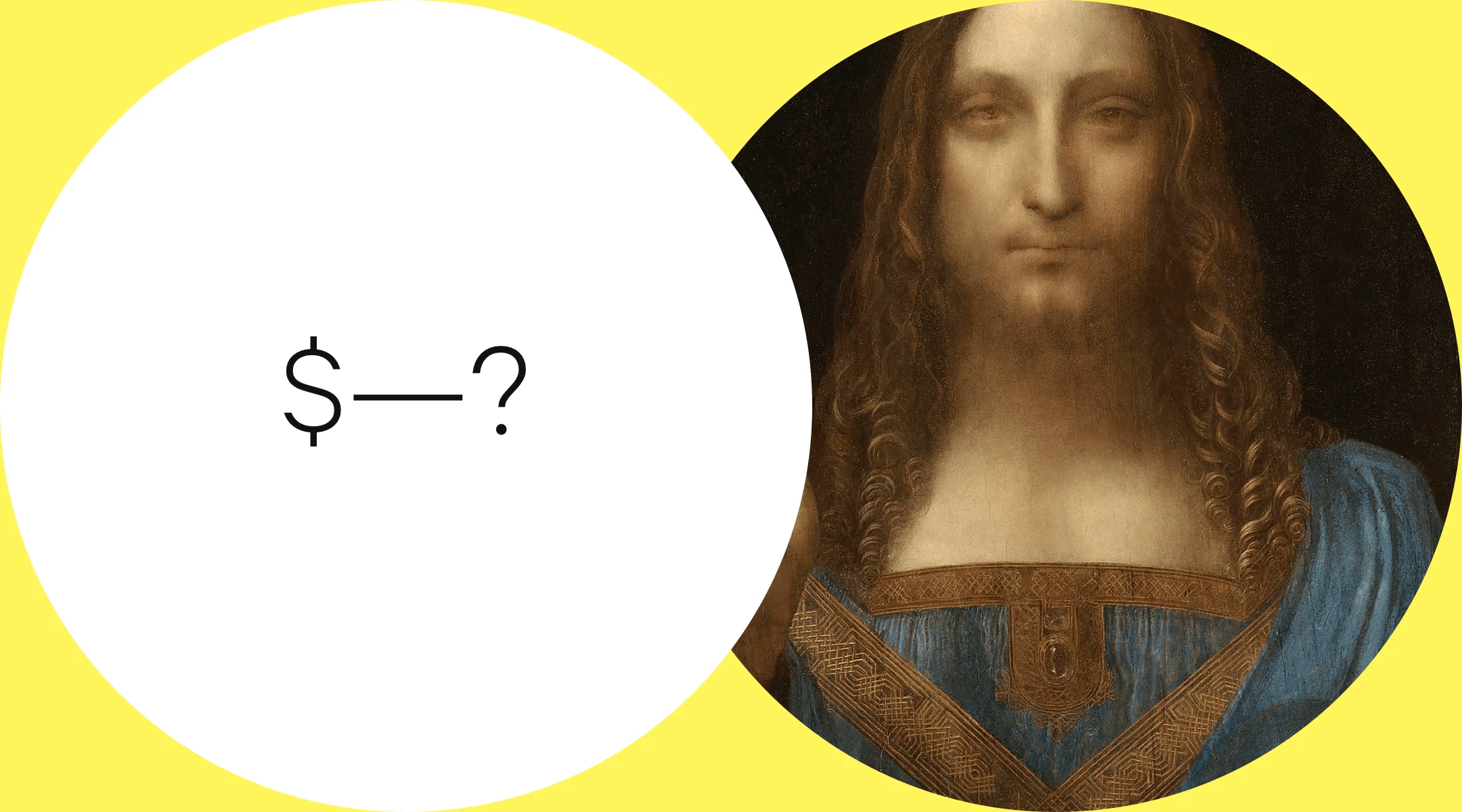

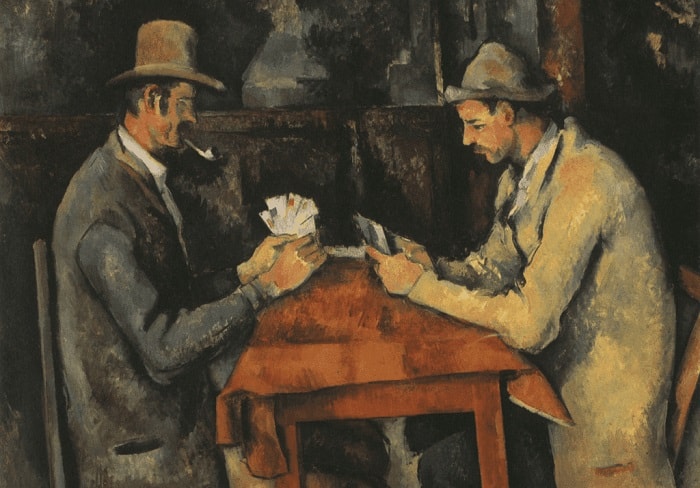

Old masterpieces are seldom sold as they are typically kept in museums, never again to change hands between private owners. Yet, the sale of these masterpieces happens now and then as did with Peter Paul Rubens ’ Massacre of the Innocents .

Rubens is considered one of the greatest painters of all time and it’s undeniable that this piece of art has technical value, insofar as the emotion, finesse, and composition is all remarkable.

But it wasn’t until recently that the Massacre of the Innocents was attributed to Rubens at all and beforehand, it went largely unnoticed. When it was identified as a Rubens, however, the value of the painting skyrocketed overnight, proving that when attributed to a famous artist, people’s perception of the artwork changes and the value goes up.

The Thrill of Auction

The salerooms at Christie’s or Sotheby’s are filled with billionaires – or better yet, their advisors. An obscene amount of money is on the line and the whole ordeal is a buzzing spectacle.

Auctioneers are skilled salesmen who help raise those prices up and up and up. They know when to bump up a lot and when to slightly tip the scales. They’re running the show and it’s their job to make sure the highest bidder has a shot and that values soar.

And they’re playing to the right audience because if one knows anything about wealthy businessmen who often find themselves in an auction house, part of the thrill is winning.

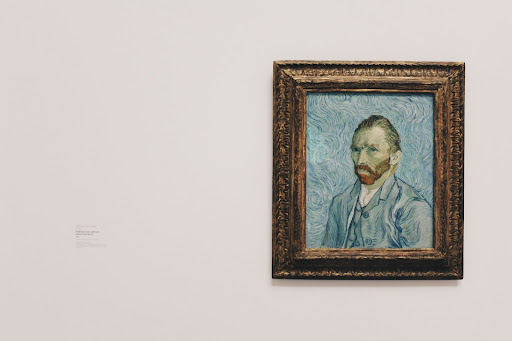

BBC also spoke to Christophe Burge, legendary auctioneer at Christie’s who described the prolonged cheering that ensued after the, then record-breaking sale of Portrait of Dr. Gachet by Vincent van Gogh .

“There was sustained applause, people leapt to their feet, people cheered and yelled. This applause went on for several minutes which is completely unheard of. The reason everybody applauded, I believe, is because we had a very serious financial situation developing in 1990. The Japanese buyers who had been the mainstay of the market were beginning to get nervous and were pulling out and everybody was convinced that the market was going to tumble.

“I think what everybody was applauding was either relief that they had saved their money. They weren’t applauding for van Gogh. They weren’t applauding for the work of art. But they were applauding for money.”

So, if you think about it, as the auctioneer steers prices up and billionaires get swept away in the thrill of a bidding war, it makes sense that, as these artworks get sold and re-sold, their value continues to change, usually going up.

Historical Significance

Historical significance works in a couple of ways when it comes to determining the value of art.

Firstly, you can consider the piece in terms of its importance to art history in its genre. For example, a painting by Claude Monet is worth more than other more recent impressionist work since Monet changed the canon of art history and impressionism as a whole.

World history also affects the value of art. After all, art is often a reflection of the culture of its time and as it became a commodity, art was affected by political and historical changes. Let’s explore this concept.

Russian oligarchs have become high bidders at art auctions as of late. Often incredibly private people, millions of dollars change hands in order own some of the most beautiful works of art. And while, sure, this could be a power play insofar as earned esteem from their closest peers, but it also indicates some historical significance.

When Russia was the Soviet Union and operated under communism, people weren’t allowed to own private property. They didn’t even have bank accounts. These oligarchs are newly allowed to own property after the communist regime fell apart and are looking to art as a way to take advantage of this opportunity.

It doesn’t have much to do with the art pieces themselves, but the fact that they have money that they can spend as they please, it’s obvious that changes in politics have a historical effect on the value of art to different people.

Another example of historical significance affecting art value is a notion of restitution.

Adele Bloch-Bauer II by Austrian painter Gustav Klimt was stolen by the Nazis during World War II. After going through a few legal hoops, it was eventually returned to a descendant of its original owner before it was sold at auction.

Due to its interesting story and historical significance on a global scale, Adele Bloch-Bauer II became the fourth-highest priced painting of its time and sold for almost $88 million. Oprah Winfrey owned the piece at one time and now the owner is unknown.

Social Status

In the earliest years of art history as we know it today, artists were commissioned by royalty or religious institutions. Private sales and auctions came much later and now it’s clear that high art is the ultimate luxury commodity with some artists now becoming brands in and of themselves.

Take Pablo Picasso , the Spanish painter from the 1950s. Steve Wynn, a billionaire property developer who owns much of the extravagant Las Vegas strip amassed quite the collection of Picassos. Seemingly, more as a status symbol than for any real admiration for the artist’s work since Picasso, as a brand, is known as the artist beyond some of the world’s most expensive pieces of all time.

To exemplify this assumption, Wynn opened an elite restaurant, Picasso where Picasso’s artwork hangs on the walls, each likely costing more than $10,000 each. In Vegas, a city obsessed with money, it seems painfully obvious that most people eating at Picasso aren’t art history majors. Instead, they feel elevated and important at the mere fact of being among such expensive art.

Later, to buy his Wynn hotel, Wynn sold most of his Picasso pieces. All but one called Le Reve which lost value after he accidentally put a hole in the canvas with his elbow.

So, people indeed spend money on art to gain social status and feel luxurious everywhere they turn. Art then becomes an investment and values continue to increase as more billionaires covet their ownership.

Love and Passion

On the other hand, while some are making business investments and gaining prestige, others are willing to pay huge sums of money for a work of art simply because they fall in love with the piece.

Before Wynn owned his collection of Picassos, most of them were owned by Victor and Sally Ganz. They were a young couple married in 1941 and a year later bought their first piece of art, Le Reve by Picasso. It cost the equivalent of more than two years’ rent and began the couple’s long love affair with Picasso until their collection became the highest-selling single-owner auction at Christie’s.

Kate Ganz, the couple’s daughter told BBC that when you say how much is it worth, then it’s not about the art anymore. The Ganz family seemed to truly love art regardless of money and this passion is probably where the value of art originates in the first place.

Other Factors

As you can see, many arbitrary factors contribute to the value of art, but other, more straightforward things make art valuable, too.

Authenticity is a clear indicator of value as copies and prints of an original painting. The condition of the artwork is another obvious indicator and, like the Picasso that Wynn put his elbow through, the value of art decreases significantly when the condition is compromised.

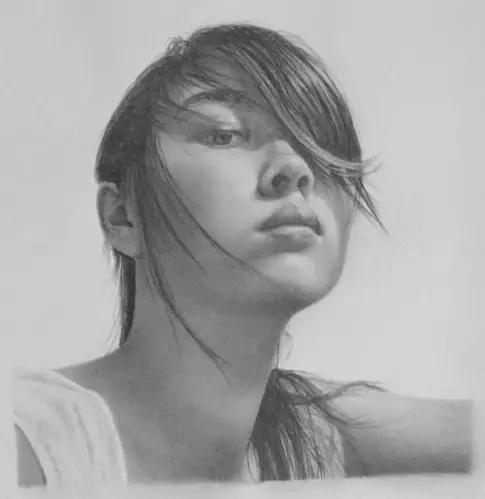

The medium of the artwork also contributes to its value. For example, canvas works are typically worth more than those on paper and paintings are often at higher values than sketches or a print.

Sometimes, more nuanced situations cause artwork to garner interest such as the early death of the artist or the subject matter of a painting. For instance, art depicting beautiful women tends to be sold for higher prices than that of beautiful men.

It seems as though all of these factors combine to determine the value of art. Whether in a perfect storm of passion and desire or a calculated risk of business transactions and retribution, art collectors continue to spend millions upon millions each year at art auctions.

But clearly, surface-level attributes aren’t the only cause of sky-high prices. From the thrill of an auction to popularity contests, perhaps the real answer is what many assert… why does it matter?

What makes art valuable beyond the cost of supplies and labor? We may never truly understand.

10 Facts about Mark Rothko, the Multiform Father

By Kaylee Randall Kaylee Randall is a contributing writer, originally from Florida. who is deeply interested and invested in the arts. She lives in Australia and writes about health, fitness, art, and entertainment while sharing her own stories of transition on her personal blog.

Frequently Read Together

6 Things About Peter Paul Rubens You Probably Didn’t Know

4 Things You May Not Know About Vincent van Gogh

Claude Monet: Get to Know the Father of Impressionism

The Value of Art Why should we care about art?

One of the first questions raised when talking about art is simple—why should we care? Art in the contemporary era is easy to dismiss as a selfish pastime for people who have too much time on their hands. Creating art doesn't cure disease, build roads, or feed the poor. So to understand the value of art, let’s look at how art has been valued through history and consider how it is valuable today.

The value of creating

At its most basic level, the act of creating is rewarding in itself. Children draw for the joy of it before they can speak, and creating pictures, sculptures and writing is both a valuable means of communicating ideas and simply fun. Creating is instinctive in humans, for the pleasure of exercising creativity. While applied creativity is valueable in a work context, free-form creativity leads to new ideas.

Material value

Through the ages, art has often been created from valuable materials. Gold , ivory and gemstones adorn medieval crowns , and even the paints used by renaissance artists were made from rare materials like lapis lazuli , ground into pigment. These objects have creative value for their beauty and craftsmanship, but they are also intrinsically valuable because of the materials they contain.

Historical value

Artwork is a record of cultural history. Many ancient cultures are entirely lost to time except for the artworks they created, a legacy that helps us understand our human past. Even recent work can help us understand the lives and times of its creators, like the artwork of African-American artists during the Harlem Renaissance . Artwork is inextricably tied to the time and cultural context it was created in, a relationship called zeitgeist , making art a window into history.

Religious value

For religions around the world, artwork is often used to illustrate their beliefs. Depicting gods and goddesses, from Shiva to the Madonna , make the concepts of faith real to the faithful. Artwork has been believed to contain the spirits of gods or ancestors, or may be used to imbue architecture with an aura of awe and worship like the Badshahi Mosque .

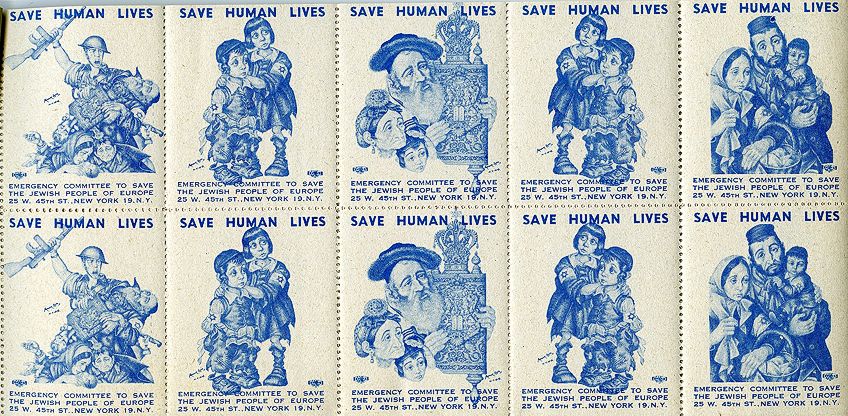

Patriotic value

Art has long been a source of national pride, both as an example of the skill and dedication of a country’s artisans and as expressions of national accomplishments and history, like the Arc de Triomphe , a heroic monument honoring the soldiers who died in the Napoleonic Wars. The patriotic value of art slides into propaganda as well, used to sway the populace towards a political agenda.

Symbolic value

Art is uniquely suited to communicating ideas. Whether it’s writing or painting or sculpture, artwork can distill complex concepts into symbols that can be understood, even sometimes across language barriers and cultures. When art achieves symbolic value it can become a rallying point for a movement, like J. Howard Miller’s 1942 illustration of Rosie the Riveter, which has become an icon of feminism and women’s economic impact across the western world.

Societal value

And here’s where the rubber meets the road: when we look at our world today, we see a seemingly insurmountable wave of fear, bigotry, and hatred expressed by groups of people against anyone who is different from them. While issues of racial and gender bias, homophobia and religious intolerance run deep, and have many complex sources, much of the problem lies with a lack of empathy. When you look at another person and don't see them as human, that’s the beginning of fear, violence and war. Art is communication. And in the contemporary world, it’s often a deeply personal communication. When you create art, you share your worldview, your history, your culture and yourself with the world. Art is a window, however small, into the human struggles and stories of all people. So go see art, find art from other cultures, other religions, other orientations and perspectives. If we learn about each other, maybe we can finally see that we're all in this together. Art is a uniquely human expression of creativity. It helps us understand our past, people who are different from us, and ultimately, ourselves.

Reed Enger, "The Value of Art, Why should we care about art?," in Obelisk Art History , Published June 24, 2017; last modified November 08, 2022, http://www.arthistoryproject.com/essays/the-value-of-art/.

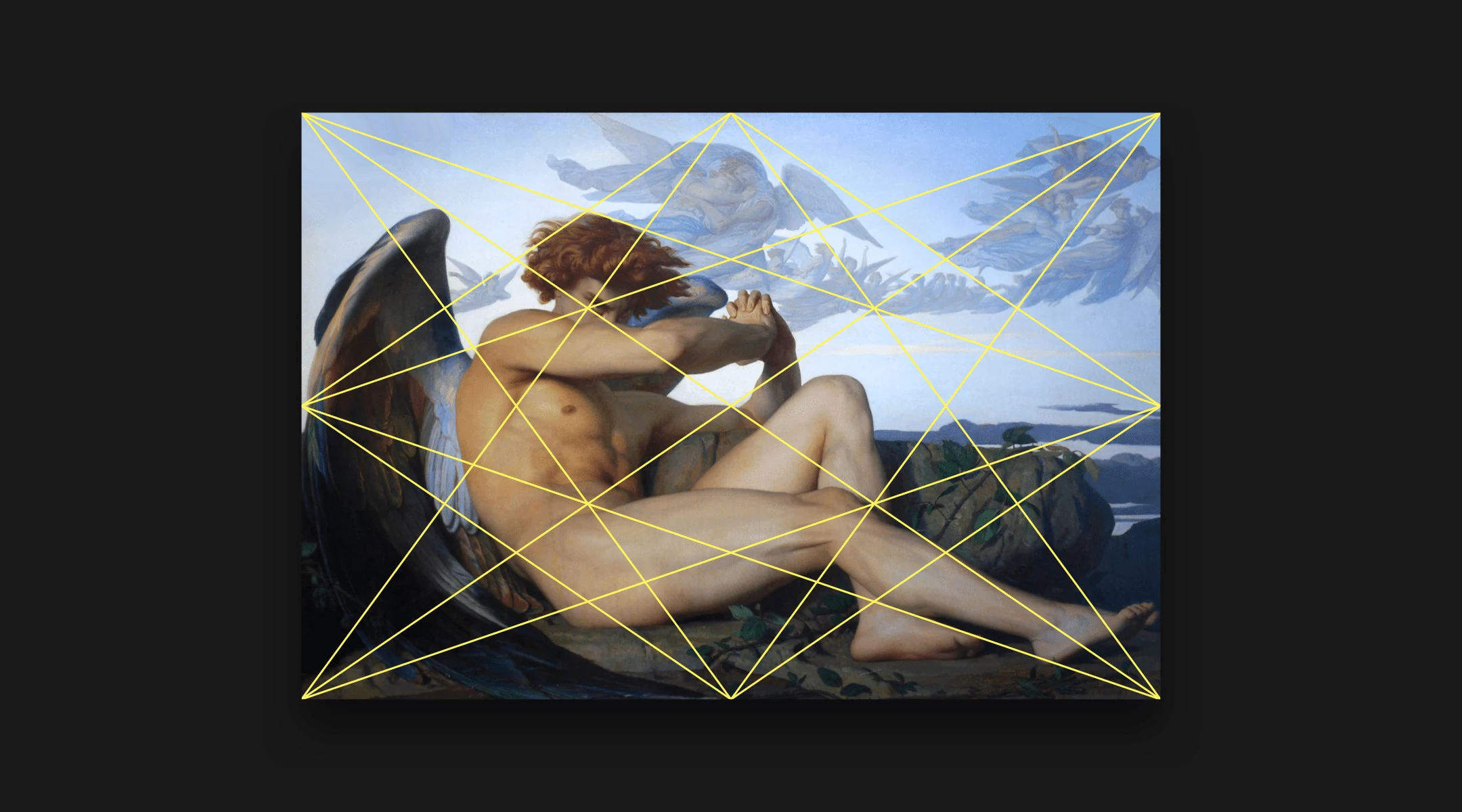

Advanced Composition Techniques

Let's get mathematical

Art History Methodologies

Eight ways to understand art

Categorizing Art

Can we make sense of it all?

By continuing to browse Obelisk you agree to our Cookie Policy

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: Start here > Unit 2

- What is Cultural Heritage?

- Where are the women artists?

- Must art be beautiful?

- Is there a difference between art and craft?

- What's the point of realism?

What makes art valuable—then and now?

- Copying — spotlight: Virgin Hodegetria

- Copying as innovation and resistance

What was the status of the artist before the modern era?

What we value has changed, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

What Makes Art Valuable? (Understanding Value in Art)

Have you ever wondered why one artist is paid tens of millions of dollars while another struggles to sell even a single piece of their artwork? If so, then you have come to the right place! In this article, I’ll discuss what makes art valuable and how to increase the value of your art.

However, first, you need to understand the fundamental concept of the art world. It is critical for everyone interested in taking their initial steps into the art industry.

Is pricing the only consideration in this concept? Is it a reflection of art’s symbolic meaning or the quality of its materials? Continue reading to learn more.

Table of Contents

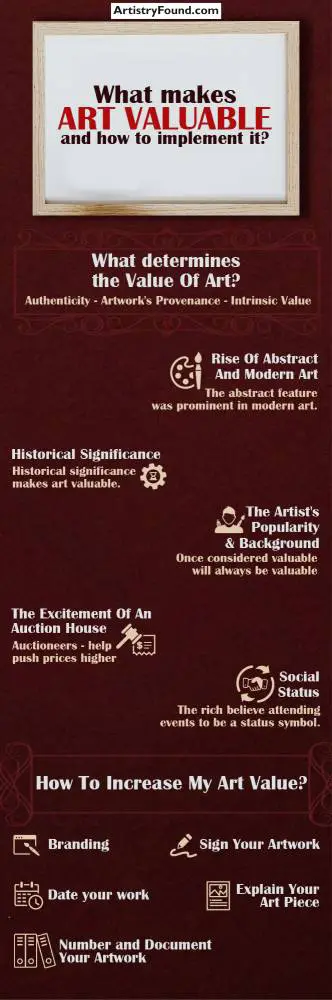

What Determines the Value of Art?

(This article may contain affiliate links and I may earn a commission if you make a purchase)

Photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash

Being an artist is difficult , and appreciating art is an art form in itself. However, it still boggles the mind that something that appears to have been drawn by a small child could be worth several million dollars. What is the story behind the astronomical prices, and how are these artworks different from other works of art?

There are various ways to look at it, and if you’re curious about how to assess the true value of art or what makes it so exorbitantly expensive or worthless, keep reading.

Authenticity

The first feature that distinguishes a low-cost painting from a high-cost one is, of course, its authenticity. An original painting will always have higher values than a replica.

Artwork’s Provenance

Another huge determining factor in an artwork’s value is its provenance or the documented history of who it has previously belonged. In other words, who were the previous owners of the painting? An artwork that was once owned by a celebrity, a prominent collector, or came from perhaps a respected gallery, for example, would increase its value.

The condition also plays an important role in determining the value of art. If the art has undergone restoration or conservation work, or if it is in poor condition and requires extensive restoration, it can have a substantial impact on its value.

Intrinsic Value

When it comes to their art, artists don’t think about money. Money is only a little part of it; it’s more of a mirror of themselves in the vast wide world. Artists express their individual and artistic expression to a bigger audience through painting, sculpture, and performance arts.

The intrinsic (or underlying) is a pretty subjective emotional value tied to how a certain work of art makes the audience feel and what sensations it stimulates. Since emotional reactions can’t be kept or measured, it is difficult to assign them a value. Moreover, all of these factors are influenced by one’s ethnic background, education, and life experience and are relatively unaffected by the materials used.

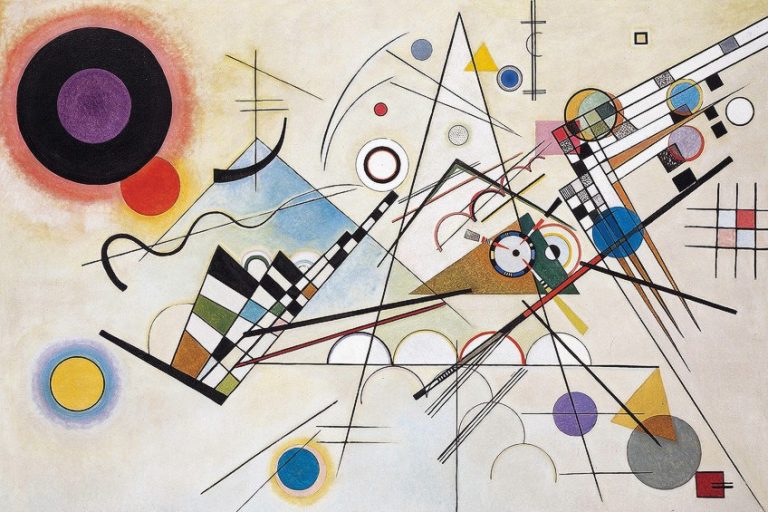

Rise of Abstract and Modern Art

Camera technology ushered in a dramatic revolution in creative culture. Photography was initially used to document the world. Thus, traditional artists no longer believed that was their primary reason for creating art. As a result, art has lost its ability to skillfully depict the world.

In the modern era, art is about how you feel and how you represent yourself. This has been one of the major transformations in art culture, and it has had a significant impact on how the world values art.

Historical Significance

When it comes to judging the worth of art, know that the historical significance makes art valuable. To begin, think about the artist’s work in terms of its historical significance within its genre. A painting by Claude Monet, for example, is more valuable than other recent impressionist works since Monet altered the narrative of art history and impressionism overall.

Art’s worth is also influenced by world history. After all, art is frequently a mirror of its time’s culture, and when it evolved into a commodity, it was influenced by political and historical changes, for example – The Mona Lisa painting .

The Artist’s Popularity & Background

The artist’s place in the art world is one of the most crucial factors to examine. Looking back through history, it’s simple to see that some artists were more influential than others, especially in the secondary market. This is due to a variety of causes, including being a leader and innovator.

If it’s a famous artist who wins prizes and is featured in exhibitions at prestigious galleries and museums, their artwork is more inclined to sell for a high price in the primary market.

If one of an artist’s paintings has been sold for a high price, other works by that artist will be considered valuable as well. And once an artist has established a brand, the sky is the limit in terms of assigning a monetary worth to their work.

The medium in which the painting is created also adds to its monetary value. Canvas works, for example, are expensive paintings. They are typically worth more than those on paper, and paintings are frequently worth more than sketches or prints.

The price a n a r t i s t c a n c o m m a n d will be affected if they have an interesting backstory, such as early death. This is partly because if they died young and created less work, supply and demand would immediately kick in. But, it’s also because artists’ lives interest the audience, so any compelling story would help sell their work.

The Excitement of An Auction House

Art, like all other things, is evaluated in comparison to other works of art. The price of modern art is influenced by recent auction results. Billionaires — or, better still, their advisors – abound in Christie’s and Sotheby’s auction houses. A huge sum of money is on the line, and the whole thing is a whirlwind of activity.

Auctioneers are adept salespeople who help push prices higher and higher. They know when to raise the stakes dramatically and when to shift the scales slightly. They’re in charge of the show, with people bidding, and it’s their responsibility to ensure that the highest bidder gets a chance and that prices rise.

And they’re playing to the proper crowd because winning is a big part of the thrill for wealthy businessmen who frequently find themselves in auction houses.

Social Status

Many people regard art as a status thing and a stepping stone to a beautiful lifestyle. There are many art fairs, auctions, and gatherings with after-parties, and the rich and famous believe attending such events to be a status symbol.

Furthermore, they spend millions on art. It helps the wealthy make a public statement about their wealth and become the center of attention. With art, there’s also an element of exclusivity.

How Artists Can Increase The Value of Their Art

Photo by Geri Mis on Unsplash

With the current global art market on the rise and living artists smashing auction records, what makes one artist more “valuable” than another?

Selling art has changed significantly over the past few decades. Works of art were commissioned in the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods, meaning that they were requested by a client and then manufactured to order. The buyer would discuss with the artist how he wanted the painting to be, the materials used, etc.

It wasn’t quite artistic freedom, but it did have its own benefits. You didn’t just paint anything and hope it sold as many artists do nowadays.

Below are ways that can make your art worth more money:

Establish an Artistic Brand

It takes more than a design, font style, or color to establish a brand. A brand is recognized because the consumer forms a personal bond with the company or product, or both. So how do you set yourself apart from the thousands of other artists that sell work online? It’s not as difficult as you may assume. All you need to do now is tell your tale.

- What is your personal narrative?

- What message are you attempting to convey through your artwork?

- What are your essential principles and morals?

- What are your sources of inspiration?

Your stories, morals, and fundamental values will draw in your target audience and increase brand exposure on the internet.

What If My Art Doesn’t Have Any Story?

Understand that every piece of art has a backstory. Remember that art comes from the depths of your soul or heart. It’s meaningful and not just a skill, practice, or thoughtless doodling. You are the protagonist of your own story.

When it comes to marketing your paintings or other artwork, you are the most important factor. Saying that your art lacks a story is like saying that you lack a story or that nothing is compelling about you or your work. You can’t possibly know what your art is about or how to express it if you don’t know who you are and what you believe in. And until you figure that out, you’re not going to get far.

Sign Your Artwork

Many artists are discovering how to sell their work online and earn money. I’ve discussed how telling your story and communicating your basic principles with your audience can boost the worth of your work. However, how can you encourage people to read your narrative if they have no idea who you are?

How can you be sure that people will recognize you as the artist behind the work they’re enjoying online? It’s not as difficult as you may believe. You only need to sign your artwork. Your work should have a signature that is constant across all of your artwork, whether it is legible or not. People will always know it’s yours this way.

Date Your Artwork

Don’t be fooled into thinking that collectors are exclusively interested in new items. People will want your previous work when you’re famous, and they’ll use it to explain your artistic progress. This will be valuable for both curators and art buyers as your career progresses.

Explain Your Art Piece

People want to know about your art, what it represents, expresses, or symbolizes, how it came to be, what’s going on in it, what inspired it, how you came up with the concept, and so on. There’s no need to get wordy, technical, or monotonous here.

You’ll need at least a one or two-sentence explanation of the art, a “way in” to understand or at least explore it, much like you’ll need a one or two-sentence explanation in a gallery or auction catalog. Allow collectors to communicate about your work with their friends by providing some information for them to talk about.

Number and Document Your Artwork

Set the edition size, never modify it, and number every piece in the edition consecutively if you’re a printmaker, digital artist, or you make multiples of any type. People who purchase multiples expect to receive a fixed edition size that will never vary.

Never alter the edition size or opt to print a new edition, no matter how successful it becomes. If you do so, you will betray the confidence of the original buyers, and, at worst, you will jeopardize the popularity and marketability of your art.

No matter how you look at it, maintaining accurate documentation of your art and art business is a great idea. This includes titles, dimensions, mediums, descriptions, images, videos, times, dates, sale prices or buyer names (where possible), and any published materials— online or in print— that are specifically linked to you and your art, such as criticisms, reviews, interviews, and so on. Good documentation of your art career’s history and evolution is essential not just for you but also for coming generations, not to mention your reputation as an artist.

What is Art Value?

A realistic evaluated value is based in part on what the work has already sold for or normally sells for not only in retail galleries, but also at auctions, secondary market websites, and other relevant venues, and it’s based on actual pricing data from previous sales.

Can Unknown Painters’ Artworks Be Valuable?

While original paintings command the highest prices, in some situations, a rare or customized print might be worth millions. A reproduction of a well-known artist’s painting is sometimes more valuable than a genuine painting by an unknown artist.

Is There Any Value in Unsigned Prints?

Prints are sometimes perceived as mass-produced replicas of well-known works of art that aren’t particularly significant or worthwhile investments. Nothing, however, could be further from the truth. Prints can be equally as valuable as any other piece of art, with some prints fetching seven or eight figures at auction.

Why Do Art Collectors Purchase Works of Art?

Aesthetics and a wish to dwell in the presence of art! The majority of online art consumers buy art to hang in their homes. Seventy-one percent of collectors polled stated that they purchase art to adorn their homes. This was the most often reported reason for buying art, even among investment-minded collectors.

What Is It That Makes Modern Art So Special?

Modernist art is defined by a rejection of traditional and conservative values or realistic renderings of subjects, as well as a richness of form (colors, shapes, and lines) with a focus on abstractions.

Every artist desires to sell their work and raise its worth. Selling art is an art form, and you’ll want to devote some time each week to improve your internet marketing skills. If you want to improve the worth of your artwork more quickly, you should learn how to become an expert in online marketing .

What Makes Art Valuable – Final Thoughts

The specific artist who created the work is highly valued by the market. It makes a significant difference whether the artist is undiscovered, emerging, or well-known. The value of an artwork is determined by the artist’s previous exhibitions, sales history, and level of experience.

In general, the higher the market price for an artist, the higher the demand for that artist. So hopefully, by now, you have a better idea of what makes art valuable.

More From Artistry Found

- What Does Art Mean to You? (5 Things to Think About)

Are Talented Artists Born or Made? (The Truth!)

- The Difference Between Art And Craft (Explained!)

- Why Artists Keep Sketchbooks (Explained!)

Bryan is an artist living in Las Vegas, Nevada who loves travel, ebiking, and putting ketchup on his tacos (Who does that?!). More about Bryan here.

Similar Posts

Why Are Artists Bad At Math? (Explained)

There seems to be a stereotype that has been around for years and years; this is that artists are notoriously bad at math. Although this appears to be the truth in some cases, not many people try to find out the reasoning behind it. So, why are artists bad at math? Artists can be bad…

Do Artists Have A Responsibility To Society? (The Truth)

Art plays such a critical role in shaping our culture and the way that society operates. But, if it is essential for free expression and reflecting our values, emotions, and politics, do artists have a responsibility to the community at large? Yes, artists have a responsibility to society. Without art, we would not have voices…

Can An Artist Use Two Names? (Explained with Examples)

Throughout the ages, artists have been known by nicknames, aliases, or stage names. Artists often use different names to make themselves sound more exotic or marketable – “Prince” sounds a lot more interesting than Prince Rogers Nelson. But does this apply in the world of fine art? Can an artist have two names? An artist can…

Artists are talented individuals capable of creating great art with the right resources. These individuals express raw talent, creating artworks that can ultimately stand the test of time. However, many are of the notion that talented artists are simply born that way, and no amount of training will make an untalented artist good. So, are…

Are Artists Depressed? (Creativity and Depression)

The tortured artist is a timeless stereotype; if you see an artist in media, you can be sure they would have mental health issues. Similarly, those characterized as having mood disorders are described as creatives—whether it be a writer, painter, or musician. Are artists depressed, and if so why? There is a link between creativity…

Portrait vs. Portraiture (What’s the REAL Difference?)

Using the terms portrait and portraiture correctly has always been so confusing to me. Everyone seems to use these words differently. But now, knowing the real difference between portrait and portraiture, everything has become crystal clear. A portrait is the end product of an artistic rendering of an individual where the person’s likeness, mood, or…

What made art valuable: then and now

For artists working in the West in the period before the modern era (before about 1800 or so), the process of selling art was different than it is now. In the Middle Ages and in the Renaissance works of art were commissioned, that is, they were ordered by a patron (the person paying for the work of art), and then made to order. A patron usually entered into a contract with an artist that specified how much he would be paid, what kinds of materials would be used, how long it would take to complete, and what the subject of the work would be.

Not what we would consider artistic freedom—but it did have its advantages. You didn’t paint something and then just hope it would sell, the way artists often do now.

Patrons often asked to be included in the painting they commissioned. When patrons appear in a painting we usually refer to them as donors. In this painting, the donor is shown kneeling on the right before the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child. Jan van Eyck, The Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele , 1436, oil on panel, 141 x 176.5 cm (including frame) ( Groeningemuseum , Bruges)

What was the status of the artist before the modern era?

One way to understand this is to think about what you “order” to have made for you today. A pizza comes to mind—ordered from the cook at the local pizza parlor—”I’ll have a large pie with pepperoni,” or a birthday cake from a baker—”I’d like a chocolate cake with mocha icing and blue letters that say ‘Happy Birthday Jerry.'” Or perhaps you ordered a set of bookshelves from a carpenter, or a wedding dress from a seamstress?

Does our culture consider cooks and carpenters to be as high in their status as lawyers or doctors (remember we’re not asking what we think, but what value our culture generally gives to those professions)? Our culture creates a distinction that we sometimes refer to as “blue collar” work versus “white collar” work.

In the Middle Ages and even for much of the Renaissance, the artist was seen as someone who worked with his hands—they were considered skilled laborers, craftsmen, or artisans. This was something that Renaissance artists fought fiercely against. They wanted, understandably, to be considered as thinkers and innovators. And during the Renaissance the status of the artist does change dramatically, but it would take centuries for successful artists to gain the extremely high status we grant to “ art stars ” today (for example, Pablo Picasso , Andy Warhol , Jeff Koons , or Damien Hirst ).

Left: Simone Martini, Annunciation , 1333, tempera on panel, 184 x 210 cm (Uffizi Gallery, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: soup can (detail), Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans , 1962, synthetic polymer on thirty-two canvases, each canvas 20 x 16 inches (Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What we value has changed

Medieval paintings were often sumptuous objects made with gold and other precious materials (like Simone Martini’s Annunciation ). What made these paintings valuable were these materials (blue, for example, was often made from the rare and expensive semi-precious stone, lapis lazuli ). These materials were lavished on objects to express religious devotion or to reflect the wealth and status of its patron. Today the value of a painting is often the result of something entirely different. Picasso could have painted on a napkin and it would have been incredibly valuable just because it was by Picasso—art is now an expression of the artist and materials often have little to do with the worth of the art.

Additional resources

Why commission artwork during the Renaissance?

Learn about life in a Renaissance artist’s workshop

Learn about the role of the workshop in late medieval and early modern Northern Europe

Learn about the role of the workshop in Italian Renaissance art

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Articles and Features

Value in Art – What Makes Art Valuable?

By Chiara Bastoni

The definition of value in art is an ever-disputed topic in the art world as the elements of art value are extremely numerous and often highly subjective rather than empirical. Understanding this concept at the core of the art market is essential to all those who wish to take their first steps into the art world. For example, what makes art valuable? Does this concept only have to do with the price? Does it reflect the symbolic nature of art or rather the fineness of its material? Watch the video below and read on to understand what is the value of art and what are the elements that define it.

What is Value in Art?

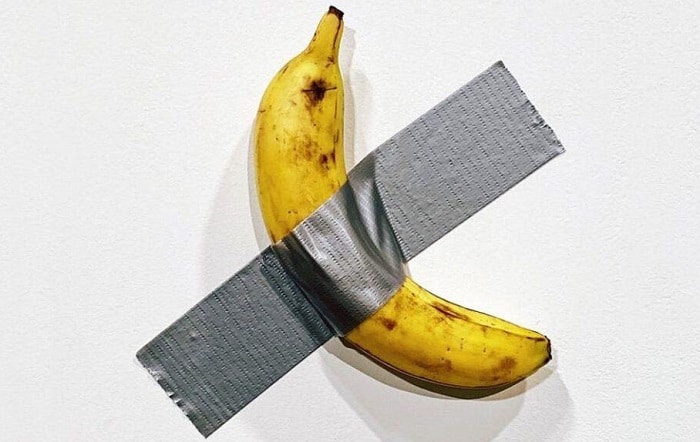

The parameters and elements that determine the value of art have certainly changed from the past. Until the advent of the modern era, the question about what is the value of art could be answered more easily, taking into consideration the materials used, the purpose served, the dimensions, the notoriety of the artist and of the commissioner – an extremely common figure back then. Even though not all of these elements have disappeared, today they are certainly complemented by others. One just has to think that today an art piece like Comedian by Cattelan can sell for 150.000 USD, a price that certainly exceeds the cost of the materials employed: a banana and a strip of duct tape.

The Elements that Define the Value of Art

Although simplistic – like all classifications – a useful categorization of the different aspects involved in the definition of the value of art includes:

- The intrinsic or inherent value of art, pertaining to its symbolic quality;

- The social value of art;

- The commercial (or market) value.

The Intrinsic Value of Art

The intrinsic value of a piece of art consists of what can’t be determined by numbers. The most difficult one to pin down, the intrinsic (or inherent) is a highly subjective emotional value, connected to how a specific work of art makes the viewer feel, what sensations it provokes, and, of course, this can’t be held or shown. Furthermore, all these variables depend upon cultural background, education, and personal life experience. and are rather independent of materials employed. For example, leaving the investment aspect of an art purchase aside, if an artwork made of gold leaves you cold, its low intrinsic value to you won’t justify its price. Debates around the overall meaning of art are countless and the definition of intrinsic value is something that pertains to the individual. After all, it has something to do with the uniqueness, irreplaceability, and sacred aura that surrounds art.

The social value of art

Another relevant element of art value is societal meaning. Art indeed is a means of communication, as it passes ideas, values, feelings, concepts, which might be received differently by each observer but still vehiculate ideas concerning society and human condition. When producing art, an artist shares a story, a sentiment, cultural elements and the moment people perceive it, they also understand it and project their own stories, sentiments and cultures. Moreover, the social value of art comes from the capacity of gathering individuals for the purpose of a communal experience.

The commercial value of art

The third main element of art value is market value, in simpler terms, its price. Given what was mentioned about the social and intrinsic value of art, it should be clear now that an artwork’s price is not determined the same way as utilitarian goods. The commercial value of an art piece, in fact, is determined according to some collective consensuses, exactly like currency: it is a human stipulation to define it.

When talking about art, there are two separate markets where negotiations take place and this stipulation happens: the primary market, undermining the passages from the artist’s hands to its first purchaser, where the price is decided mainly by the artist himself and his dealer, and the secondary market, for all successive passages of an art piece, where the price inevitably follows the principle of demand and supply.

What makes art valuable?

As mentioned, the market value is mainly determined by the galleries and auction houses. The consensuses that are born in this context are accountable for establishing a history of pricing for an artwork or an artist, which helps new works or works resold on the market to be priced.

Several are the inputs to this process:

One of them is the context of the production of an artwork. This can either be of historical importance or have a certain meaning in the development of history.

Another essential element is the provenance of the work, meaning the history of ownership once it enters the secondary market. If the previous owner of the piece was a famous collector, this information certainly doesn’t pass unobserved. If the artwork belonged to a museum, this adds an incredible value to the art piece, as much as to make them “off” the market most of the time. This also has an effect on the rarity of the work and on the mechanisms of demand and supply: the more artworks of a specific artist are situated in public museums, the less amount of artworks will be available for sale, therefore, the more the value of those works for sale.

The market also takes into consideration the conditions in which the artwork has been preserved. This is evaluated by experts and varies according to the taste of the period. There were eras, in fact, where invasive restorations were carried out to the detriment of originality, while now this is an element that takes out value rather than adding more.

Other paramount factors to consider are the authenticity of the work, which is technically evaluated, and the quality of its production, which is, on the opposite, subjective. However, subjectivity is removed by art critics who are able to judge on factors such as the clarity of execution and the mastery of the medium used, independently from style and era.

Other elements to take into consideration are the size of the work and the materials used, even though, especially when it comes to contemporary art, these factors became secondary. Sometimes also the subject has an impact on the price, as, for example, women subjects on average sell better than men.

Finally, the market values extremely the artist who produced the work. Whether the artist is unknown, emerging, or a blue-chip artist, it makes a huge difference. The price is based on the artist’s exhibition history, sales history, and career level. In general, the greater the demand for an artist, the higher the prices fetched on the market.

Relevant sources to learn more

Learn more with our Top 10 Books That Explore the Fine Art of Collecting Read more on BBC: Why is art so expensive?

Wondering where to start?

- Artblog Radio

How do we value art?

Dearest Artblog readers,

We are thrilled to present to you two firsts: our first long-form essay co-written by Morgan and Roberta, and our first audio article! You heard us right- if you aren’t in the mood to read something long today, you can listen to Roberta recite this essay in her soothing voice. Today, we cover value: Why is art undervalued in America? Well, maybe it would be valued if it were accessible, prioritized in our educational system, and inclusive.

You can listen to “How do we value art?” on Apple Podcasts and Spotify . And thank you AGAIN Kyle McKay (our podcast music composer) for writing our brand new audio article intro and outro!

Our value system in America is blurry. What do we value? Money certainly, and for some that is the most important. We’ve all heard the phrase “time is money,” (and we have plastic surgeons and the beauty industry devoted to keeping our youthful glow), so we can say we value time. We seem to value skill, at least when it comes to medicine, law, sports, or acting. We say we value knowledge but maybe we actually value expertise. Experts save us time, after all. America has certainly made itself clear about one thing: it doesn’t value art.

Needed: a more holistic approach to art including both object and maker

Art is irrefutably valuable when used as an indicator of wealth, a status symbol, or when it can be resold at a profit. However, we do not value artists for their time, skills, knowledge, or expertise. Time: if paid by the hour, a graphic designer who is efficient is punished . Skills: artists are expected to maintain a day job and pursue their art career in the evenings and weekends. Expertise: you will not see an art expert on the news; people think they know enough about art already (abstract art? my kid could paint that).

If art is an area of time, skill, and expertise, it ticks off three value boxes. So why does art not come to mind when we ask most people what they value? One huge reason art is not valued is because it is not accessible. It is treated not as a part of life, but as a non-essential feature of life, reserved for the few, but not for everyone. Art can and should be for everyone. By not valuing artists, we devalue art. Art encompasses both maker and object.

We argue that art is of great societal value, and that by demystifying art through increased access and integration into our educational system, art can be elevated in our topsy turvy value system and adopted as a holistic practice that benefits not only artists and arts educators, but our entire society.

What is art?

Art is thinking critically and rethinking systems and breaking rules. That is art’s value. It is a system that changes and adapts and allows anyone to participate in shaping it. It is democratic. Art is not a narrow field of study, it is a response to the human need for beauty, order, community. It’s not too strong to say that art is a human need. It doesn’t die, it changes.

If you randomly selected a group of people on the street and asked them to define art, you wouldn’t reach one universally agreed upon answer. Artists cannot even agree on a definition, in part because art is complex — it’s a system of thinking and a practice of making as well and it is always in the state of being redefined. What is seen as art today would have been rejected 100 years ago.

A phrase that we hear too often is “I can’t draw,” which is a self-dismissive comment but also a value statement about art. The unsaid corollary is “And I don’t understand art.” Drawing is not the definition of art, and the common understanding that drawing is art creates a barrier that prevents many from accepting art as anything other than the means for a pretty picture. But art is a practice of life.

The roles of teachers, lawyers, actors, are clear, but who are artists, what do they do? This inability to define what artists are and do creates a devaluing of the artists and a kind of misty demonization or in some cases glorification of these unknowable people. It also dismisses the art made by the demonized people and allows the value of art to be considered only in monetary terms. If you have little knowledge of art, there is no context in which to value it, other than money. If the news says a Van Gogh painting sells for $125 million, people know that’s a valuable piece of art. But that doesn’t connect with their lives and is pretty meaningless information except for Quizzo.

Here is a meaningful example of art that does not require the ability to draw: art can be a community project, like Project Row Houses . Not only does PRH employ and provide opportunities for artists in Houston, it also runs The Young Mother Residential Program which provides housing to young mothers and their children so that the mothers can go back to school. Art can be an invitation to cook together, like Shreshth Khilani’s Immigrant Kitchen . Artblog itself is an art project. Projects such as these are a testament to art’s ethos: art exists to challenge norms, pose questions, and propose positive change.

STEM AND STEAM

It is no wonder though, that when art is seen as a talent or ability rather than a way of life based on critical thinking, community and beauty, that time and time again, art is the first thing to be cut from underfunded public schools. The arts are categorized as superfluous and not worthy of tax dollars. These funding decisions disproportionately affect poor people, marginalized people, and those who attend public schools, fueling the idea that art is a privilege and not for everyone. The lack of art in schools impoverishes education and impoverishes society.

STEM was one nail in the coffin of art. It’s an easy sell to kill art programs in favor of Engineering, Math, Technology and Science. But even before STEM came along in 2001, we had the culture wars in the 1980s and 1990s, when Sen. Jesse Helms and the Republican and religious right went after the NEA and gutted its budget for having given grants to artists like Andres Serrano, Karen Finley and others who made what the conservatives believed to be sacrilegious or profane art. That was not the first and it wouldn’t be the last time art was de-listed as a public good, something valued.

Philadelphia Arts in Education Partnership ( PAEP )’s STEAM program is an effort to reintroduce the arts. But as an organization that relies on grants and operates after school and in the summer, they are destined to fail because they are not integrated into the educational foundation. They are a band-aid, plopping the “A” back in there, instead of a permanent fixture of the educational value system.

The academia feedback loop

And don’t get us started on art college. Why, you ask, if there is no art in most elementary and secondary schools, do colleges and universities teach art and award students degrees in Fine Art? Well, the answer is that some students want to study art. Some people actually feel bad when they don’t make art. They need to express themselves in ways that fulfill them that science, math, technology and engineering don’t. Art helps people express themselves – it fulfills a human need to communicate.

Art school is effective in teaching verbal communication: think critique, artist talks, art theory. This training makes BFAs uniquely qualified to solve problems that require creativity, flexibility, and thinking on your feet. BFAs can easily point out flaws and provide solutions. They excel at offering different perspectives. BFAs are a unique resource and should be employable everywhere to help with critical thinking and problem solving. They deserve more than barista jobs, which is what many fall into after graduation.

But art school itself is flawed. It is expensive and often cultivates an elitist and insular culture. And due to lack of employment opportunities for BFA graduates, many find themselves right back in academia (as MFA students, and then as professors). In her essay Work Ethic , Helen Molesworth points out this problem: “The rise of the MFA artist– an artist trained in large measure to become a teacher in MFA programs.” This is not a sustainable model. Postgraduate education is not affordable, and it’s not accessible, and it’s not diverse. We need to get out of this academia feedback loop and diversify undergraduate and graduate art education to provide opportunities for those who wouldn’t otherwise attend art school but want to. Check out Kemuel Benyehudah’s piece, “school to museum pipeline,” which is all about that, here .

While some are now rethinking the value of college education, which is priced so high it’s creating a generation of loan-enslaved graduates, we say the value of college lies in its ability to safely allow young adults to explore the world and grow into mature humans. And for that we believe access to a four-year college should be free, and all education past that should be affordable. While we’re at it- even though we believe in access to postgraduate education, we believe an MFA degree should never be a job requirement. This only services the business of art education and forces underemployed, overqualified BFAs into even more debt. BFAs deserve a living wage.

Getting art back into America’s value system and communities

We believe there should be full employment of artists after art school. Artists should be paid to impress upon others the skills of critical thinking, creative problem solving, and values of community. There should also be full employment in the non-profit sector, for artists to work with communities in programs like Americorps. This may seem outrageous to you in 2020, but under Lyndon Johnson in the 1970s, CETA employed more than 10,000 artists with living wages. This model is practiced today in the Berkshires through THE OFFICE ’s program, Artists at Work ( AAW ). THE OFFICE’s Rachel Chanoff says the ultimate goal is to make AAW national and as expansive as the WPA .

Museums can address their lack of diversity, inclusion, and community enrichment initiatives by working with public schools and colleges to employ, mentor, and collaborate with artists of color and marginalized artists. Again, you should really check out Kemuel’s in-depth piece about this topic.

How have we tried to prove art’s value?

Data survey research by Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance and others has proven art’s value with dollar signs: “Arts and culture is a $4.1 billion economic engine for Philadelphia…” That’s $4.1 billion in total economic impact, with 55,000 full-time equivalent job; $1.3 billion in household income; $224.3 million in state and local taxes. You would think that was demonstration enough of art’s value, but unfortunately that is not the case, as evident by the city’s decision to gouge the arts and culture budget (the Office of Arts Culture and the Creative Economy and the Philadelphia Cultural Fund, known as OACCE and PCF) earlier this year. Arguments about art as an economic power player don’t sell in political arenas where low hanging fruit (like OACCE and PCF) are easily cut when budgets need trimming.

How should we value art? Art’s value is its holistic value

We want to convey, with urgency, that art is a practice of life that has been undervalued through inaccurate stereotypes and narrow generalizations about its purpose. Like love, and faith, art is hydra-headed. It is not stagnant, it is understood through societal context and time. In other words, we found ourselves thinking about how to “redefine” art, but defining art is not the problem. Art needs a conceptual manicure. It should be rethought as a holistic practice that can be integrated into anyone’s lives, instead of as a club. We need to conceive of a way to introduce the value of art into peoples lives in a holistic way that begins with public education, right down to pre-kindergarten.

These are steps that can be taken immediately: Support art by supporting artists with your dollars: buy their work. Support art by celebrating artists — go to their studios (safely) and talk with them and learn about their art. Support art by starting to call yourself an artist! It doesn’t matter if you haven’t been to art school, or if you did but haven’t made anything since. It doesn’t matter if you think you’ve never made art. If you think critically, you are an artist. If you think visually, you are an artist. Do you knit? Do you crochet? Do you curate your living space or bookshelves? Do you enjoy food presentations, or tending to your garden? What color are the clothes you put on today? All of these actions– just to give you a short list of examples– are artistic. Finally, embrace the idea of art as a life practice. Say it: Art is not separate from life.

What Others Are Reading...

Taji Ra’oof Nahl, Val Gay, Tuft the World, Philadelphia Consortium Print Fair, ‘The Cut’

Reggie Browne, finance leader, art collector and patron, thinks globally and locally about supporting the arts

Valerie Gay is Chief Cultural Officer! Commonweal Gallery, Locks Gallery, Woodmere Art Museum pop with artist news, Roberto Lugo, Tim McFarlane, an opportunity and Pittsburgh!

- Ask Artblog

- Socialist Grocery

- The 3:00 Book

- What Makes Us Unique

The Artblog, Inc. 1315 Walnut Street, Suite 320 Philadelphia, PA 19107

Why Is Art Important? – The Value of Creative Expression

The importance of art is an important topic and has been debated for many years. Some might think art is not as important as other disciplines like science or technology. Some might ask what art is able to offer the world in terms of evolution in culture and society, or perhaps how can art change us and the world. This article aims to explore these weighty questions and more. So, why is art important to our culture? Let us take a look.

Table of Contents

- 1.1 The Definition of Art

- 1.2 The Types and Genres of Art

- 2.1 Art Is a Universal Language

- 2.2 Art Allows for Self-Expression

- 2.3 Art Keeps Track of History and Culture

- 2.4 Art Assists in Education and Human Development

- 2.5 Art Adds Beauty for Art’s Sake

- 2.6 Art Is Socially and Financially Rewarding

- 2.7 Art Is a Powerful (Political) Tool

- 3 Art Will Always Be There

- 4.1 What Is the Importance of Arts?

- 4.2 Why Is Art Important to Culture?

- 4.3 What Are the Different Types of Art?

- 4.4 What Is the Definition of Art?

What Is Art?

There is no logical answer when we ponder the importance of arts. It is, instead, molded by centuries upon centuries of creation and philosophical ideas and concepts. These not only shaped and informed the way people did things, but they inspired people to do things and live certain ways.

We could even go so far as to say the importance of art is borne from the very act of making art. In other words, it is formulated from abstract ideas, which then turn into the action of creating something (designated as “art”, although this is also a contested topic). This then evokes an impetus or movement within the human individual.

This impetus or movement can be anything from stirred up emotions, crying, feeling inspired, education, the sheer pleasure of aesthetics, or the simple convenience of functional household items – as we said earlier, the importance of art does not have a logical answer.

Before we go deeper into this question and concept, we need some context. Below, we look at some definitions of art to help shape our understanding of art and what it is for us as humans, thus allowing us to better understand its importance.

The Definition of Art

Simply put, the definition of the word “art” originates from the Latin ars or artem , which means “skill”, “craft”, “work of art”, among other similar descriptions. According to Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary, the word has various meanings; art may be a “skill acquired by experience, study, or observation”, a “branch of learning”, “an occupation requiring knowledge or skill”, or “the conscious use of skill and creative imagination especially in the production of aesthetic objects”.

We might also tend to think of art in terms of the latter definition provided above, “the conscious use of skill” in the “production of aesthetic objects”. However, does art only serve aesthetic purposes? That will also depend on what art means to us personally, and not how it is collectively defined. If a painting done with great skill is considered to be art, would a piece of furniture that is also made with great skill receive the same label as being art?

Thus, art is defined by our very own perceptions.

Art has also been molded by different definitions throughout history. When we look at it during the Classical or Renaissance periods , it was very much defined by a set of rules, especially through the various art academies in the major European regions like Italy (Academy and Company for the Arts of Drawing in Florence), France (French Academy of Fine Arts), and England (Royal Academy of Arts in London).

In other words, art had an academic component to it so as to distinguish artists from craftsmen.

The defining factor has always been between art for art’s sake , art for aesthetic purposes, and art that serves a purpose or a function, which is also referred to as “utilitarianism”. It was during the Classical and Renaissance periods that art was defined according to these various predetermined rules, but that leaves us with the question of whether these so-called rules are able to illustrate the deeper meaning of what art is?

If we move forward in time to the 20 th century and the more modern periods of art history, we find ourselves amidst a whole new art world. People have changed considerably between now and the Renaissance era, but we can count on art to be like a trusted friend, reflecting and expressing what is inherent in the cultures and people of the time.

During the 20 th century, art was not confined to rules like perspective, symmetry, religious subject matter, or only certain types of media like oil paints . Art was freed, so to say, and we see the definition of it changing (literally) in front of our very own eyes over a variety of canvases and objects. Art movements like Cubism , Fauvism, Dadaism, and Surrealism, among others, facilitated this newfound freedom in art.

Artists no longer subscribed to a set of rules and created art from a more subjective vantage point.

Additionally, more resources became available beyond only paint, and artists were able to explore new methods and techniques previously not available. This undoubtedly changed the preconceived notions of what art was. Art became commercialized, aestheticized, and devoid of the traditional Classical meaning from before. We can see this in other art movements like Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, among others.

The Types and Genres of Art

There are also different types and genres of art, and all have had their own evolution in terms of being classified as art. These are the fine arts, consisting of painting, drawing, sculpting, and printmaking; applied arts like architecture; as well as different forms of design such as interior, graphic, and fashion design, which give day-to-day objects aesthetic value.

Other types of art include more decorative or ornamental pieces like ceramics, pottery, jewelry, mosaics, metalwork, woodwork, and fabrics like textiles. Performance arts involve theater and drama, music, and other forms of movement-based modalities like dancing, for example. Lastly, Plastic arts include works made with different materials that are pliable and able to be formed into the subject matter, thus becoming a more hands-on approach with three-dimensional interaction.

Top Reasons for the Importance of Art

Now that we have a reasonable understanding of what art is, and a definition that is ironically undefinable due to the ever-evolving and fluid nature of art, we can look at how the art that we have come to understand is important to culture and society. Below, we will outline some of the top reasons for the importance of art.

Art Is a Universal Language

Art does not need to explain in words how someone feels – it only shows. Almost anyone can create something that conveys a message on a personal or public level, whether it is political, social, cultural, historical, religious, or completely void of any message or purpose. Art becomes a universal language for all of us to tell our stories; it is the ultimate storyteller.

We can tell our stories through paintings, songs, poetry, and many other modalities.

Art connects us with others too. Whenever we view a specific artwork, which was painted by a person with a particular idea in mind, the viewer will feel or think a certain way, which is informed by the artwork (and artist’s) message. As a result, art becomes a universal language used to speak, paint, perform, or build that goes beyond different cultures, religions, ethnicities, or languages. It touches the deepest aspects of being human, which is something we all share.

Art Allows for Self-Expression

Touching on the above point, art touches the deepest aspects of being human and allows us to express these deeper aspects when words fail us. Art becomes like a best friend, giving us the freedom and space to be creative and explore our talents, gifts, and abilities. It can also help us when we need to express difficult emotions and feelings or when we need mental clarity – it gives us an outlet.

Art is widely utilized as a therapeutic tool for many people and is an important vehicle to maintain mental and emotional health. Art also allows us to create something new that will add value to the lives of others. Consistently expressing ourselves through a chosen art modality will also enable us to become more proficient and disciplined in our skills.

Art Keeps Track of History and Culture

We might wonder, why is art important to culture? As a universal language and an expression of our deepest human nature, art has always been the go-to to keep track of everyday events, almost like a visual diary. From the geometric motifs and animals found in early prehistoric cave paintings to portrait paintings from the Renaissance, every artwork is a small window into the ways of life of people from various periods in history. Art connects us with our ancestors and lineage.

When we find different artifacts from all over the world, we are shown how different cultures lived thousands of years ago. We can keep track of our current cultural trends and learn from past societal challenges. We can draw inspiration from past art and artifacts and in turn, create new forms of art.

Art is both timeless and a testament to the different times in our history.

Art Assists in Education and Human Development

Art helps with human development in terms of learning and understanding difficult concepts, as it accesses different parts of the human brain. It allows people to problem-solve as well as make more complex concepts easier to understand by providing a visual format instead of just words or numbers. Other areas that art assists learners in (range from children to adults) are the development of motor skills, critical thinking, creativity, social skills, as well as the ability to think from different perspectives.

Art subjects will also help students improve on other subjects like maths or science. Various research states the positive effects art has on students in public schools – it increases discipline and attendance and decreases the level of unruly behavior.

According to resources and questions asked to students about how art benefits them, they reported that they look forward to their art lesson more than all their other lessons during their school day. Additionally, others dislike the structured format of their school days, and art allows for more creativity and expression away from all the rules. It makes students feel free to do and be themselves.

Art Adds Beauty for Art’s Sake

Art is versatile. Not only can it help us in terms of more complex emotional and mental challenges and enhance our well-being, but it can also simply add beauty to our lives. It can be used in numerous ways to make spaces and areas visually appealing.

When we look at something beautiful, we immediately feel better. A piece of art in a room or office can either create a sense of calm and peace or a sense of movement and dynamism.

Art can lift a space either through a painting on a wall, a piece of colorful furniture, a sculpture, an ornamental object, or even the whole building itself, as we see from so many examples in the world of architecture. Sometimes, art can be just for art’s sake.

Art Is Socially and Financially Rewarding

Art can be socially and financially rewarding in so many ways. It can become a profession where artists of varying modalities can earn an income doing what they love. In turn, it becomes part of the economy. If artists sell their works, whether in an art gallery, a park, or online, this will attract more people to their location. Thus, it could even become a beacon for improved tourism to a city or country.

The best examples are cities in Europe where there are numerous art galleries and architectural landmarks celebrating artists from different periods in art history, from Gothic cathedrals like the Notre Dame in Paris to the Vincent van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Art can also encourage people to do exercise by hiking up mountains to visit pre-historic rock art caves.

Art Is a Powerful (Political) Tool

Knowing that art is so versatile, that it can be our best friend and teacher, makes it a very powerful tool. The history of humankind gives us thousands of examples that show how art has been used in the hands of people who mean well and people who do not mean well.

Therefore, understanding the role of art in our lives as a powerful tool gives us a strong indication of its importance.

Art is also used as a political medium. Examples include memorials to celebrate significant changemakers in our history, and conveying powerful messages to society in the form of posters, banners, murals, and even graffiti. It has been used throughout history by those who have rebelled as well as those who created propaganda to show the world their intentions, as extreme as wanting to take over the world or disrupt existing regimes.

The Futurist art movement is an example of art combined with a group of men who sought to change the way of the future, informed by significant changes in society like the industrial revolution. It also became a mode of expression of the political stances of its members.

Other movements like Constructivism and Suprematism used art to convey socialist ideals, also referred to as Socialist Realism.

Other artists like Jacques-Louis David from the Neoclassical movement produced paintings influenced by political events; the subject matter also included themes like patriotism. Other artists include Pablo Picasso and his famous oil painting , Guernica (1937), which is a symbol and allegory intended to reach people with its message.

The above examples all illustrate to us that various wars, conflicts, and revolutions throughout history, notably World Wars I and II, have influenced both men and women to produce art that either celebrates or instigates changes in society. The power of art’s visual and symbolic impact has been able to convey and appeal to the masses.

Art Will Always Be There

The importance of art is an easy concept to understand because there are so many reasons that explain its benefits in our lives. We do not have to look too hard to determine its importance. We can also test it on our lives by the effects it has on how we feel and think when we engage with it as onlookers or as active participants – whether it is painting, sculpting, or standing in an art gallery.

What art continuously shows us is that it is a constant in our lives, our cultures, and the world. It has always been there to assist us in self-expression and telling our story in any way we want to. It has also given us glimpses of other cultures along the way.

Art is fluid and versatile, just like a piece of clay that can be molded into a beautiful bowl or a slab of marble carved into a statue. Art is also a powerful tool that can be used for the good of humanity good or as a political weapon.

Art is important because it gives us the power to mold and shape our lives and experiences. It allows us to respond to our circumstances on micro- and macroscopic levels, whether it is to appreciate beauty, enhance our wellbeing, delve deeper into the spiritual or metaphysical, celebrate changes, or to rebel and revolt.

Take a look at our purpose of art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the importance of arts.

There are many reasons that explain the importance of art. It is a universal language because it crosses language and cultural barriers, making it a visual language that anyone can understand; it helps with self-expression and self-awareness because it acts as a vehicle wherein we can explore our emotions and thoughts; it is a record of past cultures and history; it helps with education and developing different skill sets; it can be financially rewarding, it can be a powerful political tool, and it adds beauty and ambiance to our lives and makes us feel good.

Why Is Art Important to Culture?

Art is important to culture because it can bridge the gap between different racial groups, religious groups, dialects, and ethnicities. It can express common values, virtues, and morals that we can all understand and feel. Art allows us to ask important questions about life and society. It allows reflection, it opens our hearts to empathy for others, as well as how we treat and relate to one another as human beings.

What Are the Different Types of Art?

There are many different types of art, including fine arts like painting, drawing, sculpture, and printmaking, as well as applied arts like architecture, design such as interior, graphic, and fashion. Other types of art include decorative arts like ceramics, pottery, jewelry, mosaics, metalwork, woodwork, and fabrics like textiles; performance arts like theater, music, dancing; and Plastic arts that work with different pliable materials.

What Is the Definition of Art?

The definition of the word “art” originates from the Latin ars or artem , which means “skill”, “craft”, and a “work of art”. The Merriam-Webster online dictionary offers several meanings, for example, art is a “skill acquired by experience, study, or observation”, it is a “branch of learning”, “an occupation requiring knowledge or skill”, or “the conscious use of skill and creative imagination especially in the production of aesthetic objects”.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20 th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Why Is Art Important? – The Value of Creative Expression.” Art in Context. July 26, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/why-is-art-important/

Meyer, I. (2021, 26 July). Why Is Art Important? – The Value of Creative Expression. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/why-is-art-important/

Meyer, Isabella. “Why Is Art Important? – The Value of Creative Expression.” Art in Context , July 26, 2021. https://artincontext.org/why-is-art-important/ .

Similar Posts

Italian Renaissance Art – What Was the Italian Renaissance?

French Art – A Deep Dive into the Art and Culture of France

Fresco Painting – The Age-Old Art of Applying Paint to Plaster

Color Field Painting – The History of Color Block Art

Non-Objective Art – Finding a Non-Objective Art Definition

Frank Stella Dies at 87 – A Legacy of Innovation

One comment.

It’s great that you talked about how there are various kinds and genres of art. I was reading an art book earlier and it was quite interesting to learn more about the history of art. I also learned other things, like the existence of online american indian art auctions.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

What Makes Art so Valuable and Expensive?

Have you ever pondered the extraordinary worth attached to modern art pieces? How does a seemingly simple painting or sculpture evolve into a multimillion-dollar masterpiece? What criteria underlie the valuation of these artworks?

Modern art, a genre-spanning from the 1860s to the 1970s, encompasses a diverse array of styles, including Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, and more. Visionaries such as Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Frida Kahlo, Andy Warhol, Ana Mercedes Hoyos, and Banksy, have left an indelible mark with their innovative expressions of thoughts and emotions. However, the journey from a canvas to a skyrocketing price tag is a complex one. Let us delve into the pivotal factors that shape the value of modern art:

Supply and Demand: A Delicate Balance