Jump to navigation Skip to content

Search form

- P&W on Facebook

- P&W on Twitter

- P&W on Instagram

Find details about every creative writing competition—including poetry contests, short story competitions, essay contests, awards for novels, grants for translators, and more—that we’ve published in the Grants & Awards section of Poets & Writers Magazine during the past year. We carefully review the practices and policies of each contest before including it in the Writing Contests database, the most trusted resource for legitimate writing contests available anywhere.

Find a home for your poems, stories, essays, and reviews by researching the publications vetted by our editorial staff. In the Literary Magazines database you’ll find editorial policies, submission guidelines, contact information—everything you need to know before submitting your work to the publications that share your vision for your work.

Whether you’re pursuing the publication of your first book or your fifth, use the Small Presses database to research potential publishers, including submission guidelines, tips from the editors, contact information, and more.

Research more than one hundred agents who represent poets, fiction writers, and creative nonfiction writers, plus details about the kinds of books they’re interested in representing, their clients, and the best way to contact them.

Every week a new publishing professional shares advice, anecdotes, insights, and new ways of thinking about writing and the business of books.

Find publishers ready to read your work now with our Open Reading Periods page, a continually updated resource listing all the literary magazines and small presses currently open for submissions.

Since our founding in 1970, Poets & Writers has served as an information clearinghouse of all matters related to writing. While the range of inquiries has been broad, common themes have emerged over time. Our Top Topics for Writers addresses the most popular and pressing issues, including literary agents, copyright, MFA programs, and self-publishing.

Our series of subject-based handbooks (PDF format; $4.99 each) provide information and advice from authors, literary agents, editors, and publishers. Now available: The Poets & Writers Guide to Publicity and Promotion, The Poets & Writers Guide to the Book Deal, The Poets & Writers Guide to Literary Agents, The Poets & Writers Guide to MFA Programs, and The Poets & Writers Guide to Writing Contests.

Find a home for your work by consulting our searchable databases of writing contests, literary magazines, small presses, literary agents, and more.

Poets & Writers lists readings, workshops, and other literary events held in cities across the country. Whether you are an author on book tour or the curator of a reading series, the Literary Events Calendar can help you find your audience.

Get the Word Out is a new publicity incubator for debut fiction writers and poets.

Research newspapers, magazines, websites, and other publications that consistently publish book reviews using the Review Outlets database, which includes information about publishing schedules, submission guidelines, fees, and more.

Well over ten thousand poets and writers maintain listings in this essential resource for writers interested in connecting with their peers, as well as editors, agents, and reading series coordinators looking for authors. Apply today to join the growing community of writers who stay in touch and informed using the Poets & Writers Directory.

Let the world know about your work by posting your events on our literary events calendar, apply to be included in our directory of writers, and more.

Find a writers group to join or create your own with Poets & Writers Groups. Everything you need to connect, communicate, and collaborate with other poets and writers—all in one place.

Find information about more than two hundred full- and low-residency programs in creative writing in our MFA Programs database, which includes details about deadlines, funding, class size, core faculty, and more. Also included is information about more than fifty MA and PhD programs.

Whether you are looking to meet up with fellow writers, agents, and editors, or trying to find the perfect environment to fuel your writing practice, the Conferences & Residencies is the essential resource for information about well over three hundred writing conferences, writers residencies, and literary festivals around the world.

Discover historical sites, independent bookstores, literary archives, writing centers, and writers spaces in cities across the country using the Literary Places database—the best starting point for any literary journey, whether it’s for research or inspiration.

Search for jobs in education, publishing, the arts, and more within our free, frequently updated job listings for writers and poets.

Establish new connections and enjoy the company of your peers using our searchable databases of MFA programs and writers retreats, apply to be included in our directory of writers, and more.

- Register for Classes

Each year the Readings & Workshops program provides support to hundreds of writers participating in literary readings and conducting writing workshops. Learn more about this program, our special events, projects, and supporters, and how to contact us.

The Maureen Egen Writers Exchange Award introduces emerging writers to the New York City literary community, providing them with a network for professional advancement.

Find information about how Poets & Writers provides support to hundreds of writers participating in literary readings and conducting writing workshops.

Bring the literary world to your door—at half the newsstand price. Available in print and digital editions, Poets & Writers Magazine is a must-have for writers who are serious about their craft.

View the contents and read select essays, articles, interviews, and profiles from the current issue of the award-winning Poets & Writers Magazine .

Read essays, articles, interviews, profiles, and other select content from Poets & Writers Magazine as well as Online Exclusives.

View the covers and contents of every issue of Poets & Writers Magazine , from the current edition all the way back to the first black-and-white issue in 1987.

Every day the editors of Poets & Writers Magazine scan the headlines—publishing reports, literary dispatches, academic announcements, and more—for all the news that creative writers need to know.

In our weekly series of craft essays, some of the best and brightest minds in contemporary literature explore their craft in compact form, articulating their thoughts about creative obsessions and curiosities in a working notebook of lessons about the art of writing.

The Time Is Now offers weekly writing prompts in poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction to help you stay committed to your writing practice throughout the year. Sign up to get The Time Is Now, as well as a weekly book recommendation for guidance and inspiration, delivered to your inbox.

Every week a new author shares books, art, music, writing prompts, films—anything and everything—that has inspired and shaped the creative process.

Listen to original audio recordings of authors featured in Poets & Writers Magazine . Browse the archive of more than 400 author readings.

Ads in Poets & Writers Magazine and on pw.org are the best ways to reach a readership of serious poets and literary prose writers. Our audience trusts our editorial content and looks to it, and to relevant advertising, for information and guidance.

Start, renew, or give a subscription to Poets & Writers Magazine ; change your address; check your account; pay your bill; report a missed issue; contact us.

Peruse paid listings of writing contests, conferences, workshops, editing services, calls for submissions, and more.

Poets & Writers is pleased to provide free subscriptions to Poets & Writers Magazine to award-winning young writers and to high school creative writing teachers for use in their classrooms.

Read select articles from the award-winning magazine and consult the most comprehensive listing of literary grants and awards, deadlines, and prizewinners available in print.

- Subscribe Now

The Literature of War

- Printable Version

- Log in to Send

- Log in to Save

Need help submitting your writing to literary journals or book publishers/literary agents? Click here! →

7 Tips For Writing Realistic War Stories (UPDATED 2024)

by Writer's Relief Staff | Inspiration And Encouragement For Writers , Nonfiction Books , Other Helpful Information , The Writing Life | 15 comments

Review Board is now open! Submit your Short Prose, Poetry, and Book today!

Deadline: thursday, april 18th.

Updated April 2023

Both fiction and memoir writing have endeavored to make sense of (or even see the senselessness of) violent conflict. But writing about war can be tricky: Some readers might be sensitive about graphic depictions of war and violence; others may have a hard time understanding what’s happening if you don’t go into detail. Here’s how to write battle scenes that are accurate and effective.

Important Tips For Writing About War

Consider whether certain violent elements need to be included. Graphic, explicit scenes can become offensive when they’re overdone or unnecessary. Of course, you may be going for “offensive” in order to make a point about your subject, but violence that’s heavy on detail needs to have a point. The key is to be aware of your choices and why you’re making them.

Use a panoramic lens. Capture the vastness of a battle by showing us a wide view of the action. Allow your narrator a moment to look around at what’s going on so that your reader can also see what’s happening. However, remember that “epic” doesn’t necessarily mean emotionally engaging. If not handled properly, big battles can feel impersonal and lead to “action fatigue.”

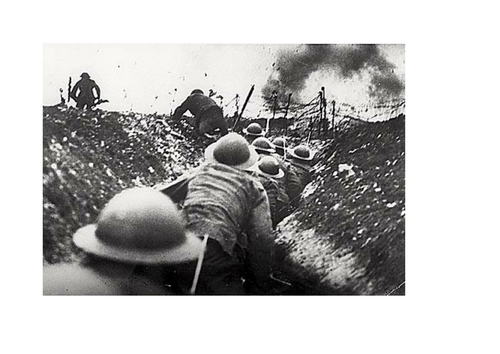

Focus on the details. Whether you’re writing about the trenches of World War I or the Time-Space Wars of the Zygine Galaxy, pay attention to the little details of everyday life. Sometimes, the familiar smell of coffee and a campfire can be more emotionally powerful than the less familiar smell of a lit cannon fuse.

If your violence is comic, be cautious of subtext. Some people may laugh; others might be offended. If you need to make a choice about your character’s actions that happens to align with stereotypes of violence, make sure you do so with caution.

Understand your characters . Whether you’re writing about a perpetrator of violence or a victim, dig deep within your own personal capacity for empathy to tease out elements that will make all of your characters human, relatable, and real—even the villains. You might not respect your antagonist’s decisions, but by understanding them, you’ll bring depth and emotion to your work.

Get it right. If you’re writing historical fiction or even memoir, check (and recheck!) your facts. Confirm that your details are accurate. By spending the extra time and doing the research , you’ll have a story that resonates with authenticity and powerful details—especially if you’re writing military fiction .

Avoid clichés. While every genre has its tropes, be aware of choices that lead to scenes that are overly familiar. Falling back on clichés is sometimes the easy way out. If you find yourself writing a familiar battle scene (one soldier dragging another to safety, or one person dying in another’s arms), be sure to mix up the action with your own unique perspective.

When In Doubt, Read Military Memoirs And Fiction

If you’re not sure your battles have a realistic edge, read other books in the genre. Reading is one of the best ways to improve your writing, regardless of your topic.

When you’ve finished reading military memoirs and fiction, why not try to get published alongside them? The research experts at Writer’s Relief will help you pinpoint the best markets and boost your odds of getting an acceptance. Learn more about our services and submit your work to our Review Board today!

Whether you want to take the traditional publishing route or prefer to self-publish , we can help. Give us a call, and we will point you in the right direction!

15 Comments

In response to your question, “What do you think one of the things many battle/war scenes get wrong is?” I would like to say it is the disconnection/connections between two common enemies. Many solders do not even know the real reason they are fighting. Many American solders have gone to battle under the false premise of spreading Democracy. Our enemy fight for what they believe to be the opposing cause. Yet, when the war is believed to be over, a new bicultural atmosphere has almost always been established. That is because, as humans, we all have more in common than not.

To Mr. JL Gibson: I loved your comment. I don’t imagine that many of us think of what the other guy is fighting for. I have no plans to write a novel about war, but I still believe that this article and your comment could be used for any other type of story. We all have our battles to fight whether it be for love, wealth, a job promotion, or even our own simple way of life. Thank you for the insight.

I’m writing a war story and this has been helpful.

I’m also writing my first war book too. My book is called Ghost Squad, the war I’m researching is very hard trying to put all pieces of information together so that the war itself is real, but my characters, operation groups, and seans are made up of this book. I’m worried if my information of this war would have false information in my novel. I’m still writing and researching, but so far my book is looking pretty good. If you guys have any tips for me that would be helpful.

This is some really good information about writing good war stories. My sister wants to be an author and she loves historical fiction. I liked your advice about getting it right and doing research about the time period. It does seem like a good idea to try reading some memoirs of actual soldiers.

I’m going to write a battilistic war book. It’s not an American war. Another countries war. A central american one. This has been helpful.

I’m writing a fictional war story, meant to focus upon the ascension of a Battalion Commander, to the ranking of General. One issue I’m having is the rankings themselves. While I can hide behind the excuse that this is a fictional war, with a fictional military that could have fictional ranking orders, I still would like to know what the actual officer ranking order is like. Google isn’t very helpful, could somebody please point me to an explicit explanation of military officer ranking ? I would greatly appreciate it, thank you! I eagerly await your reply.

Vincent, the ranks for officers are easy to find. They are: 2nd Lieutenant, 1st Lieutenant, Captain, Major, Lieutenant Colonel, Colonel, Brigadier General, Major General, Lieutenant General, and General.

Thank you , I am a struggling writer who will indeed benefit from this

Thank you for the help! I am writing a book that has many military scenes. I appreciate this a bunch!

Read books written by veterans

Definitely read books by veterans. And if you are writing a book about the military, it would be extremely helpful to have a veteran as a beta reader. Lee Childs doesn’t write military, but his main character, Jack Reacher, is an ex soldier – however he has so many military fact incorrect it sometimes drives me crazy. One of his main problems is that the author is British, and the character is American. In the British Army, I guess, the enlisted shine the officer’s boots and do their laundry; this is absolutely not what happens in the US Army. Also, his premise that the military police are better trained in weapons and hand to hand so they can subdue elite Rangers and green berets when necessary is crazy.

The government actually has many good primary resources in this area. I recently took over a blog written by a librarian that highlights government sources to help authors with realism in their fiction. I am still in the process of transferring, editing, and updating the older entries (which has been fascinating), but it has several military history posts:

https://fictionwritersguidetogovernmentinformation.wordpress.com/

Hope this is helpful!

Hi. I´m terrible when it comes to battle strategy. I just have my characters with the planned development, dynamics, relationships and often – fitting deaths. I have the moral questions. I have the magical system. I somehow just make the war fit my needs… Which is extremely frustrating! I have to think of stuff to fill plot holes and all the strategies don’t add up! It’s like a patchwork – a beautiful piece of art (an emotional moment, a character death, a release of a magical power) is hanging on some weak shit.

Please send help. I always get stuck on the tactics. How to master it? Or how to write smart and compelling fantasy stories without it? Even if it’s not fantasy, I have the feeling that without all these scheming and mind games my stories sound boring.

Look at what you did in the first paragraph. You have already arrived at most of the story, since story is about character and relationships. The action that arises from the characters, i.e., what each character does, moves along the plot, defines character, and produces story theme and meaning. Then, think of your story within the context of a particular moment in the war. For example, “Platoon” selected a section of a company to go on patrol in the Vietnam jungle, night and day, to tell the story of young American foot soldiers and particularly, the growth of one particular named Taylor. How does the war fit into the story? The war, or a particular aspect of the war necessary to the story is selected and used as a container to hold the entire story about Taylor.

Take a look at another war story, “The Deer Hunter”. This is the story about Russian-American steelworker friends who go off to Vietnam as foot soldiers. Each one is altered. Therefore, the writer must have planned particular moments in the war to highlight the exigencies of each character as such character encounters life-challenging and possibly, life-changing conflicts that determine what we must notice about the character.

Please don’t allow the loud and epic nature of war to scare you into giving up. Writing about war is no different than writing about a city, or school, or people on a cruise liner. The fact remains that all of those are contexts or backdrops to your story, which should always be about the human condition, i.e., our thwarted desires that lead us to the truth and beauty of realization and/or learning, if we (the characters) accept the challenging lessons, or losing, if we reject, as the author intends to depict.

Finally, a war is always about one side against the other, with a line drawn in the sand. Such could be visible or invisible. Find your war, select a context and people that context with who would be necessary for the particular story. My war story challenge tonight is to tell a story about particular soldiers on the frontline of WWI, but not across the entire several hundred miles of trenches. I selected one small area that produces the particular challenges of that area, which I feel excited about depicting., and how that place set up significant pressure on the characters to think and behave in certain ways that I believe to be necessary for telling the reader/viewer about our mysterious human condition — perhaps, even deepening the mystery.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

See ALL the services we offer, from FREE to Full Service!

Click here for a Writer’s Relief Full Service Overview

Services Catalog

Free Publishing Leads and Tips!

- Name * First Name

- Email * Enter Email Confirm Email

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Featured Articles

Featured Video

- Facebook 121k Followers

- Twitter 113.9k Followers

- YouTube 5.1k Followers

- Instagram 5.5k Followers

- LinkedIn 146.2k Followers

- Pinterest 33.5k Followers

- Name * First

- E-mail * Enter Email Confirm Email

WHY? Because our insider know-how has helped writers get over 18,000 acceptances.

- BEST (and proven) submission tips

- Hot publishing leads

- Calls to submit

- Contest alerts

- Notification of industry changes

- And much more!

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Pin It on Pinterest

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Make Your Own List

Politics & Society » War

The best war writing, recommended by kate mcloughlin.

War writing extends to all sorts of genres, including blogs and Twitter. Oxford University's Professor Kate McLoughlin , author of Authoring War: The Literary Representation of War from the Iliad to Iraq recommends some of her favourite books of war writing.

Interview by Beatrice Wilford

Charlotte Sometimes by Penelope Farmer

The Iliad by Homer

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

Catch 22 by Joseph Heller

If This Is a Man by Primo Levi

1 Charlotte Sometimes by Penelope Farmer

2 the iliad by homer, 3 war and peace by leo tolstoy, 4 catch 22 by joseph heller, 5 if this is a man by primo levi.

Y ou’ve chosen three novels, a memoir and a poem. Which other genres come under the umbrella of war writing?

Does writing about war, in the vein of someone like Hemingway, ever glamorise it? And is there a vein that does the opposite?

Yes. It’s possible to split war writing into pro-war writing and anti-war writing and that can depend on the culture at the time, or it can depend on the individual’s view.

Hemingway obviously thought war was a great thing. Outside war, he liked hunting, fishing and shooting. Killing things was his thing and a war was a natural environment for him. That’s not to say that he thinks that war is an unmitigated good. For Whom the Bell Tolls and A Farewell to Arms show the human cost of war as well, and the political cost of war, and the futility of it.

“The blog has taken over from the epic as the war-writing genre of choice.”

I suppose it’s rare to find anything that says war is a good thing without it being questioned at all. But some of the earlier texts celebrate heroism in battle unquestioningly.

How do writers deal with the horrors of war?

There is some incredibly graphic description of what goes on in war and among the most graphic is one I’ve chosen, the Iliad , where there are descriptions of horrific injuries. Another way of describing the horrors of battle is by indirection. Describing, for example, all the people who didn’t get funerals in the First World War—as Wilfred Owen does in ‘ Anthem For Doomed Youth ‘—is a way of conveying death and loss and bereavement on a mass scale.

Is there a clear gender divide in written perspectives on war?

Yes, I think there is. There’s a concept famous among academics who work on war writing called ‘combat gnosticism,’ gnosticism meaning knowledge. It’s the idea that only people who’ve been in combat have earned the right to write about it. And it seems pretty unique to war as a phenomenon. You would think something like childbirth would be similar, but it seems not. It’s war: you have to be in it to be able to write about it according to some people. That has led to there being a canon built up of combatant writing. Especially, for example, the First World War and the trench poets. Of course that has implications for that section of humanity who don’t get to fight in armed combat: women.

I think there are only two armies—the Israeli and the Russian—in which women, even now, can fight as ground forces. That means women have been banished and talk about another angle: the folks back at home, the hospitals, the orphans, the widows, the more sentimental aspects of war. But you get some incredibly feisty women who fight their way to the front anyway, who don’t take no for an answer, stow away, just turn up and who write remarkable reportage—and of course that’s not to overlook the role of the imagination in all of this. Being in war, actually having that combative experience, you might get too close and need more of a detached perspective.

I think the gendering of war writing is about different kinds of experience, but not different kinds of validity of experience.

You’re currently writing about modern warfare. Your most recent book choice is Charlotte Sometimes , written in 1969. How has war writing changed in this time?

The book I’m working on at the moment is called Veteran Poetics . It’s an exploration of certain philosophical ideas—self, experience and storytelling—in the age of modern mass warfare, which I date from 1793 as that’s when the French issued their levée en masse : mass conscription. I think the French Revolution and Napoleonic wars were when war became modern, globalized, industrialised and mass.

I also think that was different from anything that had gone before. Walter Benjamin famously said in his essay “The Storyteller”, “men came back from the First World War, not richer but poorer in communicable experience.” I think he got the date wrong, I think it was actually the Napoleonic and French Revolutionary wars. He conveys this sense of having had an experience that you can’t describe because there’s literally nothing to compare it with, and I think that’s a very modern feeling. I think that’s almost a unique feeling to modernity.

The books I’m looking at for my veterans book wouldn’t necessarily qualify as obvious war writing. The most recent ones are by JK Rowling, her Cormoran Strike series, because they feature a detective who’s a veteran. I trace that figure back to Lord Peter Wimsey and to Dr Watson. I’m looking at how veterancy becomes a means of expressing a certain kind of problem solving, not the forensic problem solving of Sherlock Holmes but the more ‘university of life’ understanding of Dr Watson.

Your first book is Charlotte Sometimes by Penelope Farmer.

This book is the first war book I read and it made a deep impression on me. I read it when I was about nine or ten. It’s a book for children , published in 1969. The Charlotte of the title is a twelve year old girl who goes to boarding school and goes to sleep in a dormitory in a bed which has a funny set of wheels on it, and wakes up fifty years earlier in 1918. She has swapped places with a girl called Clare, who in 1918 was sleeping in the same bed. We don’t hear from Clare’s point of view, what she makes of 1969 or 1968, but we do hear about Charlotte, who finds herself in the final year of the First World War .

They swap backwards and forwards night after night. The plot twist is that Charlotte gets stuck in 1918. She and her younger sister are evacuated to a house where the son has gone to war thinking it was going to be a fantastic military heroic adventure, and it turns out it wasn’t. They play with his toy soldiers and the family hold a séance. It made a huge impression on me because Penelope Farmer has this incredibly deft way of making you get a sense of the shock Arthur feels on going to war and finding it was nothing like his toy soldiers and his ideas of bravery.

There is another poignant moment surrounding a teacher in the 1918 school called Miss Wilkins. She’s very bright—a little bit plump, she’s sort of birdy and beady—and Charlotte likes her very much. When she eventually gets back to her own time there’s a Miss Wilkins who’s white haired and a different person altogether, her fiancé died in the First World War. It’s a way of showing how, without being graphic in the slightest, this enormous worldwide conflict had very personal consequences. I think it’s an extraordinary novel and a very thought-provoking one, with many interesting details for children to use to think about war.

What should we tell children about war?

You don’t want to overwhelm children with the seriousness and magnitude of war, but on the other hand there are children who have no choice but to live through war. The children who are told about it are the lucky ones. But I think doing it in this way, having details of the home front, makes it extremely vivid.

There are other fantastic war books for children. Carrie’s War by Nina Bawden is another good example. That also involves an evacuation. It is dear to my heart because my dad was an evacuee. That sense of the impact of war on children comes across very convincingly, very vividly.

As you describe, this book has a very complex temporal framework. How does war alter our experience of time, and how does writing seek to reflect this?

Let’s move on to your second book, the Iliad .

The Iliad is absolutely extraordinary. I read it every so often, and from the beginning it has the most incredible evocation of place, on the beach with the camp fires and Achilles sulking in his tent. There’s such a sense of camaraderie between these warriors. It’s an ancient culture, completely foreign to us now, and yet somehow we are brought to feel their day-to-day emotions. Not just on the Greek side, on the Trojan side as well. There are poignant moments, for example where Hector’s going in to fight and his wife Andromache doesn’t want him to. It’s an extraordinarily vivid account of war and a very graphic one.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

The edition I read it in first, and still read it in, is E. V. Rieu’s Penguin Classics translation. When I’m doing my academic work, I check it against the Loeb Classic edition where it’s very literally translated. Rieu fought in the First World War. He was in the Maratha Light infantry in India and then in the Second World War he was in London in the Blitz, when he decided to start translating the Odyssey . He did the Odyssey first and then the Iliad . This is a veteran in war, translating the great book of war.

How has the Iliad influenced and shaped the genre of war writing?

It continues to inspire. There have been so many writers who have been influenced by it. For an epic, it manages to do both things: it has an enormous scope, but then it really focuses in. To write vividly about battle you need that human interest angle. Monomachia or hand-to-hand fighting comes out in other much later works of war literature, which focus on a single individual and their fate in war.

I’m thinking now of C.S. Lewis in Surprised By Joy . He fought in the First World War and when he got to the western front he said, “This is war, this is what Homer saw.” I’m sure it was nothing like it actually, it’s dubious whether Homer was one single person and it’s unclear whether he could see. But it still carries the weight of all these centuries of cultural baggage.

Having influenced war writing; do you think the Iliad influenced the way people fought in wars?

Book number 3 is War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy . Don’t people only read it for the peace bits? Because the war bits can be quite boring, people say.

The last hundred pages are dull, but if you can stick out the first 1200, then you might as well stick out the last. For the first 1200, it’s a kind of ebb and flow between war and peace, and I think each is equally engaging. When you get to the war parts, Tolstoy is always having the characters think about how they can talk about war. So Nikolai Rostov has these very heroic ideas of going into battle, but then it’s not quite as heroic as he imagined, it doesn’t go as well as he thought, and then when he’s asked to talk about it he realises his listener seems disappointed, so he very quickly slips into a standard heroic war tale. Tolstoy didn’t fight in the Napoleonic wars, but he did fight in the Crimean war, so he drew on his experiences in that when he wrote War and Peace .

Yes, it’s not about the time that he’s writing in. How common is writing written post conflict? What difference is there between this and writing written in a conflict?

That’s true of most of the choices here. Tolstoy is writing in the 1860s about the beginning of the nineteenth century, Homer is writing about an imaginary war, Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 is published in 1961 and it’s about the Second World War . Penelope Farmer was writing a good fifty years after the First World War . I think people do write about previous wars and partly it’s a way of avoiding contemporary rawnesses.

Let’s move on to Catch 22 , tell me about this book.

This is the great war book of the twentieth century. It’s laugh-out-loud funny. He’s talking about the Second World War , which is thought of as the good war. He picks up on an aspect of war which has gone on since Homer. You have an overarching war strategy which might make sense, but, for the individual, the things they’re asked to do can seem absolutely ludicrous — in this case to fly death-defying, practically suicidal missions. It’s completely illogical, being in the war zone. He captures that brilliantly: through repetition, through completely farcical situations and through extremely harrowing moments as well.

Is comedy antithetical to war, or is it a useful lens through which to look at the experience of war?

Laughter and war are almost natural companions. But I wouldn’t say laughter implies funniness or a lack of seriousness, and nor does comedy. Catch-22 gets you to the point where you can’t apply your reason any more and laughter takes over. It’s the laughter of the absurd which might not be to do with funniness, but is to do with preposterousness or incongruity or disbelief. It’s that kind of, “I can make no sense of this,” laughter and I think evoking it is incredibly skilful.

Another person who does it is Spike Milligan. I love his war memoirs. The first one is Hitler: My Part in His Downfall . Just the title conveys the ridiculous. He is one person who mostly spends his Second World War in Bexhill-on-Sea doing maneuvers.

Catch 22 also has some very visceral descriptions of the horrors of war. How successfully does he convey those experiences and what are their purpose in this book?

He does convey them graphically. He makes it absolutely clear that man is mortal. A character gets chopped in half and there’s someone else who’s horribly wounded in an air accident and you find out the contents of his stomach. It’s literally visceral, his kidneys are there with the tomatoes he had for breakfast. He’s very good at conveying that sense of the absolute mortality and carnality of the human body.

“There’s nothing like war to show the fragility of the human body, its destructibility.”

There’s a recurring character called the Soldier in White, who’s a soldier in the hospital completely encased in white plaster cast. In another scene the characters discover the solder in white is gone and an identical one is in his place. Although his arms are different lengths and his body’s a different length, he’s still encased in white, so there will always be a Soldier in White. People become absolutely indistinguishable from one another, which conveys this sense of man as organic matter. There’s nothing like war to show the fragility of the human body, its destructibility.

There’s the amazing description of the Blitz in Kate Atkinson’s Life after Life . The narrator sees a body that she thinks is clothes on a coat hanger because it’s just hanging there.

I was stunned by Life After Life . I think that idea of the world turned upside down, and particularly the house turned inside out, is quite common. I can only imagine what it must feel like to have an intimate room like the bedroom suddenly on show in the street, and have all your possessions out in the street. It’s the complete opposite of civilized living. Writers use it quite often, “ The Land-Mine ” by George Macbeth described how the war has ripped off the front of houses.

Your final book is If This Is a Man by Primo Levi.

I first read this in my twenties. It was my introduction to the Holocaust . This is when I began to understand what the Holocaust had been. Primo Levi was an Italian Jew and an industrial chemist who was sent to Auschwitz. It is about his existence in Auschwitz. Reading it, horror follows horror. It’s hard to believe that the human frame can survive under such circumstances, let alone survive to write something like this.

There are two moments in it that particularly struck me. Auschwitz is in Poland and it’s winter. The hard labour is extremely difficult and it is very cold and bitter. The prisoners are going to be synthesizing rubber in a factory near to Auschwitz, so there is a chemistry exam. And it’s the most infernal exam in the world. This person who has been reduced to something that is almost sub-human now has to try and remember his chemistry from his degree. If he can remember he will be able to work inside in the warmth, and he won’t die. There’s something about being a scholar and thinking about your knowledge under such circumstances that is very powerful.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount .

He does get to work in the factory, which probably saves his life. There is a scene in which he is going with a very young prisoner to get soup and suddenly a line from Dante’s Inferno comes to his mind. It’s the Ulysses canto, where Ulysses is saying, “I’m not meant for men like these but men who strive after excellence” and Primo Levi tries to remember it. Trying to remember it is this moment of confirmation that he’s still human. The young man he is with is French and doesn’t see what he’s talking about, but senses that it is really important. Levi doesn’t remember the whole canto, but he remembers enough snatches of it that he’s just about got it. I’d like to say that this proves the enduring, humanising power of literature, but I’m not sure you can. George Steiner has pointed out in his great book Language and Silence that people who read Goethe and listened to Schubert in the morning then went out and did their work as guards at Auschwitz. So I don’t think literature improves you. Nonetheless, it is a moment worth registering because it is this remembrance that means so much to him and he says, “I would give my day’s soup ration to remember that line.” You’d have to read this account to know how much a day’s soup ration matters.

This makes me think of Elaine Scarry’s The Body In Pain and her idea that if you reduce somebody to just a cipher or symbol of your own power through causing them pain it involves that removal of self. I think it’s a very coherent way of thinking about that loss of humanity–you remove the inner life and you make them simply a body.

Yes, I absolutely agree with that. The writing of this, and similar Holocaust memoirs, is a reaffirmation, it goes back to combat gnosticism. It’s hard for anyone who hasn’t been in that situation to talk about reaffirmation, because it’s hard to imagine just what you would have to come back for.

How does he approach the writing of the truly unspeakable?

He writes with extreme candor and a remarkable lack of self-pity. I think there’s this sense, in theories of representations of the Holocaust, that if you deviate even slightly from the truth then you risk letting in the deniers. And so the place of literature in relation to the Holocaust is a very delicate subject. As readers, we have to be very, very aware of the potential of slipping into sentimentality, or trying to make something good out of it that just isn’t there

Does our knowledge of his suicide in any way alter the experience of reading his writing?

In a way it just makes the bravery of the writing—not only of If This Is A Man but all his other works, which never leave this subject—the more extraordinary. There is something about surviving to bear witness, it is an incredibly brave thing to do. He strikes me as an absolutely heroic person.

You’re writing now about literature and silence, how can silence creep into literature? Might it be the purest expression of a horrific event?

My next project is going to be about literature and silence. It grows out of the last chapter of the book I’m writing on veterans which is called “The End of the Story”. The penultimate chapter is about veterans who never stop talking about the war as a model of literary creativity. And the final chapter is about veterans who won’t say anything or can’t say anything or don’t say anything.

We neglect the silences in literature. I’m interested in the acoustic use of silence in poetry or drama and in things that aren’t said, and how we know they’re not said. It’s terribly difficult if you’re not going to say something or write something in protest, how do you register that? You’ve got to sort of hedge it round with words. But I think we can try and listen to those silences.

And silences, as we know from the two minute silence, are incredibly powerful. I want to try and understand this better, and understand how we can see silences in texts that are there, and also maybe texts that aren’t there, or texts that aren’t as they would have been. It’s looking into the realm of the subjunctive, into the hypothetical, into the not said.

February 12, 2016

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Kate McLoughlin

Kate McLoughlin is Associate Professor of English at Harris Manchester College, Oxford. Her books include Authoring War: The Literary Representation of War from the Iliad to Iraq (2011) and Martha Gellhorn: the War Writer in the Field and in the Text (2007). She is a former government lawyer, an Associate of the Royal College of Music in piano performance, and a poet: her collection Plums came out in 2011.

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

Contemporary Writing on War and Conflict

- World War One: Projects to Mark the Centenary

- September 2014 - December 2018

This project examines the contemporary war experience as reflected by writers, poets, journalists and bloggers, and interrogate how we write about war and conflict today in contrast to the writing that was written on WW1.

Thought pieces from leading contemporary UK writers are a starting point for international public discussions. Looking at questions such as: What is the role of the writer in responding to conflict? What feels like an appropriate amount of time before creating an artistic response to war? Who do we trust to write about war? What we accept as war literature today, and how this is influenced by its context and changing global situations. How do we capture the human experience of war?

Caroline Wyatt on reportage

Patrick Hennessey on memoir

Helen Dunmore on fiction,

Owen Sheers on poetry

Ben Hammersley on digital writing

Helen Dunmore was the first winner of the Orange Prize and is also an acclaimed children's author and poet. She has published twelve novels including Zennor In Darkness , winner of the Mckitterick Prize; A Spell Of Winter , winner of the first Orange Prize; The Betrayal , longlisted for the Man Booker prize, shortlisted for the Orwell Prize and the Commonwealth Writers Prize; The Greatcoat (2012) and The Lie (2014). Helen Dunmore has also published three collections of stories, Love Of Fat Men, Ice Cream and Rose 1944 , and her stories have been widely broadcast and anthologised. Her children's novels include the INGO series, published by harpercollins and shortlisted for the Nestlé Smarties Book Prize. Her ten poetry collections include The Raw Garden, Out Of The Blue and The Malarkey , all published by Bloodaxe Books. She spoke on the theme of war in her work at events in Russia at the Krasnoyarsk Book Fair 1-4 November 2014 along with Nigel Farndale (who spoke about the research he undertook on the First World War for his novel The Blasphemer ) and Imtiaz Dharker (who talked about her response to Wilfred Owen’s Anthem of Doomed Youth in the collection of poems 1914 Remembers ).

Patrick Hennessey was born in 1982 and educated at Berkhamsted School and Balliol College, Oxford, where he read English. On leaving university he joined the Army and served from 2004 to 2009 as an officer in The Grenadier Guards. In between guarding towers, castles and palaces he worked in the Balkans, Africa, South East Asia, the Falkland Islands and deployed on operational tours of Iraq and Afghanistan. On leaving the Army he wrote his first book, The Junior Officers’ Reading Club , a memoir of a brief but eventful stint in uniform; followed by Kandak an account of how unlikely alliances can be forged in the intensity of battle. Patrick is now a barrister.

Owen Sheers has written two collections of poetry, The Blue Book and Skirrid Hill , which won a Somerset Maugham award. His verse drama Pink Mist won Wales Book of the Year and the Hay Festival Poetry Medal. Non-fiction includes The Dust Diaries and Calon: A Journey to the Heart of Welsh Rugby . His first novel Resistance has been translated into ten languages and was made into a film in 2011. His plays include The Passion, The Two Worlds of Charlie F and Mametz , which has been longlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize 2014. His second novel, I Saw A Man , is published by Faber & Faber in 2015.

Ben Hammersley is an author, futurist and technologist specialising in the effects of the internet and the ubiquitous digital network on the world’s political, cultural and social spheres. He enjoys an international career as a trends and digital guru, explaining complex technological and sociological topics to lay audiences, and as a high-level advisor on these matters to governments and business. Ben Hammersley is a Fellow at The Brookings Institute in Washington DC, a fellow at the Robert Schuman School of Advanced Study at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy, and Innovator-in-Residence at the Centre for Creative and Social Technologies, Goldsmiths, University of London. He is contributing editor of WIRED Magazine and writes regularly for the international media including The Financial Times .

Caroline Wyatt became the BBC’s Religious Affairs Correspondent in August 2014, having been a BBC Defence Correspondent from 2007. Prior to that, she covered UK operations in Iraq from 2003 and in Afghanistan from 2001. From 2003 - 2007, Caroline was BBC Paris correspondent, and before that spent three years as Moscow Correspondent, charting Vladimir Putin's first term as Russian President. She also covered NATO in Kosovo in 1999, and Russian operations in Chechnya, as well as working in Gaza and the wider Middle East for the BBC in the late 1990s and early 2000s. She is also an occasional presenter for R4 The World Tonight and Saturday R4 PM. She contributed to 'The Oxford Handbook of War', R4’s ‘More from Our Own Correspondent’ and ‘Only Remembered’, a children’s anthology edited by Michael Morpurgo looking at the literature of WW1.

Sign Up to the Newsletter

Become a Bestseller

Follow our 5-step publishing path.

Fundamentals of Fiction & Story

Bring your story to life with a proven plan.

Market Your Book

Learn how to sell more copies.

Edit Your Book

Get professional editing support.

Author Advantage Accelerator Nonfiction

Grow your business, authority, and income.

Author Advantage Accelerator Fiction

Become a full-time fiction author.

Author Accelerator Elite

Take the fast-track to publishing success.

Take the Quiz

Let us pair you with the right fit.

Free Copy of Published.

Book title generator, nonfiction outline template, writing software quiz, book royalties calculator.

Learn how to write your book

Learn how to edit your book

Learn how to self-publish your book

Learn how to sell more books

Learn how to grow your business

Learn about self-help books

Learn about nonfiction writing

Learn about fiction writing

How to Get An ISBN Number

A Beginner’s Guide to Self-Publishing

How Much Do Self-Published Authors Make on Amazon?

Book Template: 9 Free Layouts

How to Write a Book in 12 Steps

The 15 Best Book Writing Software Tools

How To Write A Book About War: 8 Tips To Authentic Prose

POSTED ON May 16, 2023

Written by Sarah Rexford

Ever wondered how to write a book about war? I don’t know where you were that summer night in July of 2017, but hopefully you found a few hours to sit in a dark theater and watch the new film release, Dunkirk . With a 92% tomatometer score , Rotten Tomatoes describes it as an “Extremely powerful and exciting war movie about the evacuation during WW2.”

Writers long to craft powerful, exciting plots that bring in readers and garner standout reviews. In this article, I show you how to write a book about war and provide an eight point, step by step guide to help you. Let’s get into it!

Need A Fiction Book Outline?

Table of Contents

Defining a war book.

Often termed a war novel or known as military fiction , a book about war has its central focus on the battlefield or the home front. Laura Hillenbrand’s Unbroken is a classic, nonfiction example of surviving during war.

Kristin Hannah’s The Nightingale is a bestselling fiction of life on the home front during World War II.

And Unbroken: Path to Redemption is the film sequel displaying Louis Zamperini’s struggle to return to normal life with PTSD and the countless complications that follow soldiers home from war.

When you decide to write a book on war, you do not need to pigeon hole yourself into one time period. Instead, you can choose to write about life on the battlefield, the home front, or returning from war.

Fiction Versus Nonfiction

While fiction and nonfiction vary greatly in most genres, when you write a book on war, both categories should include a factual recounting of historical events.

While Kristin Hannah can create characters of her own, they need to live in environments that could have, or did, actually exist during the war time setting she places them in. In the same way, Laura Hillenbrand had to include strictly factual details about her real-life protagonist’s story. Whether you write fiction or nonfiction, facts are key.

How To Write A Book About War: Things To Include

Just like every genre, there are key factors to include when learning how to write a book about war. I dive deeper in the coming guide, but keep these three aspects top of mind for fiction:

- Include multiple types of conflict

- Include realistic battle scenes

- Include humanized character

For nonfiction, your list is quite similar. Be sure to include:

- The primary conflicts your protagonist faced

- Realistic depictions of their experiences

- Multiple facets of their character

Next up, your step by step guide.

Step By Step Guide

With the above in mind, let’s dive into eight steps you can take as you write a book about war.

#1 – Define Your Primary Focus

There are so many factors to consider when you decide to write a book about war. In fact, it can feel like an insurmountable task to even begin to include every important detail. Instead, focus on the primary goal of your story.

If you write nonfiction, how can you best share an individual’s story or an event? For fiction, what should you focus on most to drive the action?

#2 – Don’t Forget About All Types Of Conflict

Second, when learning how to write a book about war it’s important to understand that your conflict doesn’t only include the setting. There are many types of conflicts you can include: Man against self, man against man, and man against nature.

While a book about war is primarily focused on man against man, consider how you can develop a deep point of view by including the conflict of man against self. This applies for both fiction and nonfiction.

#3 – Use The Senses To Showcase Emotion

It may feel difficult to include the five senses when writing on the topic of war, but it’s important to accurately portray it. Resist the urge to sugar coat the experiences of veterans and those who gave their lives, and instead, use the five senses to realistically display your scenes.

Of course, keep your target audience in mind and recognize that no matter how many edits you make, you can never replicate the experience itself. However, you can do your best to tell an honest story.

#4 – Understand What You’re Writing And How To Write It

Unless you’re writing your memoir or autobiography, you likely don’t have first hand experience about what you will write about. To aid you in this process, consider watching movies about war to visualize battle.

Steven Spielberg’s 1998 film, Saving Private Ryan is a great place to start. Spielberg depicted the Normandy landing so well that the film triggered PTSD in the veterans who watched it . If you write a book taking place on the battlefield, learn how to write battle scenes well.

#5 – Add Humanity To Common Tropes

Every genre has tropes, but when you write a book about war, don’t forget the humanity in the individuals and characters you write about. Louis Zamperini was not only a prisoner of war, he was a living, breathing individual with feelings, fears, hopes, and dreams.

To strip your protagonist of their humanity, particularly if you write nonfiction, is to lessen the weight of their sacrifice.

#6 – Resource Other Books

Simply writing this article is a reminder of the gravity in choosing to write a book about war. It is not an easy topic, so be sure to learn from authors who have gone before you. Read as many books in the genre as possible to get a grip on how to write well.

#7 – Remember You Can Always Edit

With tip number six in mind, remember that when you write a book about war, or any topic, you can always edit your manuscript. Until you send your final draft to the publisher or click publish you can make changes. Do your best to create a great first draft, but you can always:

- Edit your battle scenes

- Add layers of humanity

- Write in more senses

- Include internal conflict

- Fine tune your central focus

Edit, edit, edit.

#8 – Check Your Facts

This should go without saying, but fact checking is so crucial I can’t do less than include it. While you can take some creative liberties when writing fiction, your nonfiction should exactly reflect the details that truly happened.

For instance, if you cover an individual’s experience during the Bosnian War, fact check every detail of both their experience and the events that occurred. For fiction, you can take liberties with your characters’ experiences, but not with the events that occurred.

The Key Is To Begin The Process

If you feel a bit overwhelmed after all of this, simply focus on your first step. What can you do after exiting out of this blog to further your manuscript? Do you need to:

- Decide what perspective character to write from, or what point of view to use ?

- Research important dates?

- Interview an individual?

Every book begins with the first step. You can do this! Feel free to reference this eight-step guide as often as you need to, and if you need further guidance, you may want to watch this video.

Remember, take it one step at a time. Best wishes as you set out on your journey!

Related posts

How to write a romance novel in 13 easy steps.

Non-Fiction

Need Some Memorable Memoir Titles? Use These Tips

Business, Marketing, Writing

Amazon Book Marketing: How to Do Amazon Ads

How to Write a War Story

So, you started writing a War story and got stuck along the way. Maybe you aren’t sure if your story meets all the obligatory scenes and conventions of its genre. Maybe you’re wondering if your controlling idea or theme addresses the overall values at stake in a War story. Maybe you’re asking, what are the core emotions, subgenres, and audience expectations of a War story? Do you even have a War story?

I’ve completed a great deal of research on War stories and I’m excited to answer these questions and more by sharing what I’ve learned.

Let’s get started.

What is a War story?

Fundamentally, a War story includes a single soldier or group of soldiers preparing for, waiting for, engaging in, and possibly recovering from wartime combat. A war story must have soldiers on a battlefield with the possibility of death. It’s important to note that it’s not every story set in time of war. It has to build and lead to a core battle, which is the equivalent of the “hero at the mercy of the villain” scene for a Thriller or the “proof of love” scene for a Love story. A wartime setting could function as a backdrop for any genre. A War story is not a history lesson on war-time conflict, a bunch of battle sequences strung together, or about a protagonist who is just a bad-ass Terminator robot. A war story is much more.

In War stories, human behavior is dramatized to demonstrate the coexistence of brutality and altruism and how extreme circumstances and trauma bring out the best and the worst in soldiers.

The story dramatizes a political perspective on war. (See subgenres and commentary on politics, below.)

What is the Global Value?

The global value at stake describes the protagonist’s primary change from the beginning of the story to the end. It’s the primary arc you’ll keep your protagonist moving along throughout your story.

The global War story turns on honor and disgrace in the context of war.

Conflict in a War story is expressed on three different levels:

External Conflict arises from fellow soldiers and/or the environmental pressures (weather, enemy forces, terrain). The protagonist is motivated by the expectations and limitations of his team to stay alive, win the battle, and obtain honor via sacrificing for fellow soldiers.

Interpersonal Conflict is between the antagonist and protagonist. The antagonist of a War story is usually the enemy forces and at least one member of a soldier’s own side, often a higher ranking official.

Internal Conflict is a war within the protagonist. This usually follows a Worldview or Morality trajectory (or both) and culminates in a shift in thinking that allows the protagonist to display all their gifts while fighting in the Big Battle. In most stories, the conflict might unfold on one or two of these levels. A War story’s conflict must unfold on all three. Confusing? Let’s take a look at the infographic.

The protagonist doesn’t necessarily have to be defeated with dishonor, but it must be a possible outcome. In a War story, the “negation of the negation” is dishonorable defeat presented as honorable. In other words, trying to convince others that one’s dishonorable behavior in war was honorable is equivalent to a character’s damnation.

War stories arises from the protagonist’s physiological AND emotional needs for safety. The War protagonist’s primary goal isn’t love, self-esteem, or financial rewards. Initially their want is to win the battle and stay alive (external storyline, conscious object of desire). They come to realize their need is to believe that life is worth living but, if they must die, dying with honor is better than dying in disgrace.

What’s the Controlling Idea?

A story’s Controlling Idea (sometimes called the theme) is the lesson you want your reader to come away with. It’s the meaning they will assign to your story.

Each of the main content genres has some generic premise statements. They are either prescriptive–a positive story that shows the reader what to do–or cautionary–a negative story that warns the reader about what not to do.

War stories can have broad-ranging purposes. You need to be absolutely clear which type you’re telling.

Prescriptive:

War is justified and meaningful when waged against a truly evil enemy. (war propaganda, Pro-War subgenre)

War’s meaning emerges from the nobility of the love and self-sacrifice of soldiers for each other. (Credit to Editors Anne Hawley and Leslie Watts)

Honor is gained in war when a soldier sacrifices for their fellow soldier, regardless of victory or defeat in battle.

Cautionary:

War lacks meaning when it is not morally justified. (Anti-War subgenre)

War lacks meaning when leaders are corrupt and dishonor soldiers’ sacrifices on the battlefield. (Credit to Editors Anne Hawley and Leslie Watts)

Honor is lost in war when a soldier refuses to sacrifice themselves for their fellow soldier, regardless of victory or defeat in battle.

What Are the Core Emotions?

Controlling Ideas help the writer elicit core emotions from the audience. Because a War story operates on three levels of conflict, it can elicit several different emotions:

Excitement, Fear

People choose War stories to experience courage and selflessness in the face of intense fear, without actual danger. False bravery.

Satisfaction, Pity, Contempt

They may also choose War stories to experience righteous satisfaction at the proper outcome for the protagonist, whether negative or positive. They want to feel pity for the tested and contempt for the unrepentant but righteous satisfaction when the punishment comes.

What are the essential moments?

Each subgenre has its own essential moments but here is what they all have in common:

A shock (negative or positive) upsets the homeostasis of the protagonist and disrupts their ordinary life. The inciting incident of a War story is an attack that challenges the morals of the protagonist. It must put them under pressure.

The protagonist denies responsibility to respond.

Editor Tip: In overtly refusing the call to change, the protagonist expresses an inner darkness (fear of cowardice and/or fear of uncontrollable rage) or a clinging to unrealistic ideals (a worldview that never allows for the expression of violence). Classic Hero’s Journey.

The protagonist’s refusal of the call complicates the story and the call comes a second time but in a different form, usually as a requirement to fight for someone or something else.

Editor Tip: The War story often compels the protagonist to act without much choice beyond do or die.

Forced to respond, the protagonist and other soldiers lash out according to their positions on the power hierarchy.

The protagonist’s initial strategy to outmaneuver antagonist fails.

The protagonist learns what their antagonist’s object of desire is.

Editor Tip: The real antagonist is often on the “side” of the soldier rather than a member of the enemy forces.

There is a clear “Point of No Return” moment, when the protagonist accepts the inevitability of death.

The protagonist, realizing they must change their approach to attain a measure of victory, undergoes an All Is Lost moment. The All is Lost in a war story is usually cathartic, a moment of acceptance of fate that either compels madness or resignation.

A Big Battle is the story’s core event. This is when the protagonist’s gifts (usually the gifts of all the team members) are expressed or destroyed. They discover their inner moral code or choose the immoral path.

Editor Tip: Make sure the primary antagonist is present in the Big Battle scene of the climax with the intent to see the protagonist fail.

The protagonist is rewarded with at least one level of satisfaction (external, internal or interpersonal) for their sacrifice. They gain honor or dishonor.

What are the essential situations?

Each subgenre has its own essential situations but here is what they all have in common:

The war portrayed must be necessary to your story, not ancillary. As an example, in Platoon , the war is what isolates the men together and forces them to act.

There is a team of soldiers on a battlefield confronting life and death stakes.

Editor Tip: Five is a common cast of predominant characters; the protagonist plus four. As Editor Anne Hawley pointed out, “Odd numbers of characters in any scene will generate more dynamic energy than even numbers.”

There is one protagonist with offshoot characters that embody a multitude of that character’s personality traits. Examples are Achilles in The Iliad , Dienekes in Gates of Fire, and Chris in Platoon .

Editor Tip: Make sure you have a foil for your protagonist within the team. This is the character who embodies the ideals and attributes opposite of your character. As in a Status story , this character exists to show the reader the other path your protagonist could have taken. An example is Mother in A Midnight Clear who represents the emotional and vulnerable traits that the protagonist, Will, is too cynical and skeptical to show. Another example is Bunny in Platoon who represents a complete lack of moral character and thoughtfulness in opposition to sentimental Chris.

The War itself is a seemingly impossible external conflict. The protagonist confronts overwhelming odds. Often, their team is substantially outnumbered.

As in a Horror story , physical violence (or the threat thereof) is ever present.

Editor tip: Use this to heighten the consequences of seemingly minor character actions.

The protagonist has a mentor or sidekick, for better or worse. This character may lead the protagonist astray or encourage moral behavior. In Platoon , Chris has Elias.

The protagonist brings their past into the war in the form of memories, ghosts, photographs, traumas, representational trinkets, etc. Whether they are able to overcome these or lean on these for support in war in order to make the right choices in the end depends upon your subgenre. In Platoon , Chris brings his emotional isolation with him. He clings to his grandmother and refuses to acknowledge his father. He comes to war to rid himself of the privileges he has at home.

The protagonist receives assistance from unexpected sources, the Herald archetypes. Some examples are the characters who tell the protagonist “the truth” such as Rhah pointing out how good and evil are battling for Chris’ soul in Platoon or Eldridge calling out James in The Hurt Locker . Or they are characters who enable the protagonist, like Bunny in Platoon .

The protagonist’s values are tested, and the test culminates in a sacrifice for the team, or, in the negative story, in a failure to make the necessary sacrifice. Platoon’s final battle scene tests Chris’s values by giving him the chance to kill Barnes. Chris chooses to sacrifice his own safety during the battle for his fellow soldiers and he kills Barnes in the name of the good of humanity.

Editor Tip: The protagonist’s self-sacrifice makes little emotional sense unless the relationships among the soldiers has been clearly shown long before this culminating scene. By the end of Platoon, Chris has stopped writing his grandmother, is connected to other soldiers, and acknowledges both Elias and Barnes as father figures.

What are the Subgenres?

Ideologically Pro-War, more externally focused stories

The core values of this subgenre ride between honorable victory and dishonorable defeat. These stories focus on the false idea that it is “us versus them” and that one side (usually American) represents the liberators and freedom fighters. “We are good. They are bad.” These stories often assert that a low status person can become a high status person and hero by virtue of their involvement in battle, that they can finally belong. Soldiers are honored and portrayed as the saviours of humanity. Violence is glorified, justified, and meaningful. Battle sequences might be under-realized and the impact of violence and the cost of war are minimized. These stories carry aspects of the Brotherhood subgenre.

Examples of this story are The Longest Day, Inglorious Bastards, Black Hawk Down, Red Dawn, and The Guns of Navarone.

Ideologically Anti-War, more externally focused stories

The core values of this story range between honorable victory and dishonorable defeat. The explicit use of random violence and repeated terror, combined with characters’ heinous acts as behavioral norms within context of their humanity, dramatize the basic premise that war negatively influences behavior and damages lives. Soldiers are flawed and often behave as their own worst enemies. Suspense techniques are employed to simulate the harsh realities of combat whether there is victory or defeat. War is meaningless and horrific for all of humanity, not just soldiers. These stories include at least one war crime scene and carry aspects of the Brotherhood subgenre.

Examples of the Anti-War story are The Red Badge of Courage, All Quiet on the Western Front, Paths of Glory, A Midnight Clear, The Thin Red Line , Dispatches (the novel on which Full Metal Jacket was based), Platoon, and Bridge On The River Kwai .

Editor Tip: Some critics and scholars argue that no film can qualify as an Anti-War story. For more information, check out this link . Whether or not their assertions apply to novels as well is unclear.

Brotherhood, more internally focused stories

The core values of this subgenre are honor and disgrace regardless of victory or loss in battle. Battle sequences are well realized. The trials of War are the external framework on which the internal genre is hung. Action and battle scenes are only used when needed to drive the internal transformation of the protagonist. Scenes may be longer than those of other subgenres to allow for more dialog and the dramatization of the protagonist’s change arc. These stories carry aspects of either the Pro-War or Anti-War subgenres or both. This story has a secondary genre of Morality or a Morality/ Worldview combo in which the protagonist must sacrifice for their fellow soldiers. This story type has a lot in common with the Performance story .

Examples of this story are Gates of Fire and The Deer Hunter.

Do you really want to tell a War story?

The challenge in writing a War story is how to innovate while remaining respectful and truthful; how to make sure the story resonates with audiences and that you don’t accidentally glorify war if you meant to damn it.

In my examination of many War stories, I saw the same story repeated over and over. If you can’t make a strong case for why you’re adding another War story to the world and clearly state how your story will be different, I challenge you to ask yourself why you want to tell a War story in the first place.

If you’re telling a primarily external genre story, you may find that your story is better told through the Performance , Society , or Action Genre. Look at the controlling ideas and value shifts of these stories and see if they are a better fit.

If you’re telling a primarily internal story, you may find your story is better served by using the frameworks of the Morality , Worldview , or Status Genres. Does your story even need ever present threats of violence and horror to work? As you recall, just because it’s set in wartime doesn’t make it a War story. You may even find your story is better served in a different setting than War.

So, if a War story is what best serves your idea, how do you craft it?

By now you know a War story isn’t created by stringing a bunch of battles and carnage together. You’ve seen they’re not a history lesson on the who, what, when, or where of war-time conflict. And you know you are going to have to take your protagonist to emotional extremes as a reaction to war events.

Your story will dramatize how a combat soldier is split between the person they were at home and the person they are at war. Put them through an emotional journey where they are helped by certain members of their team, fight an enemy, destroy part of themself, and suffer a real or metaphorical death and rebirth. Show how individual soldiers react to trauma in different ways, how they struggle with the expected and approved deception of combat with their sense of self and the world outside of combat where they’ve only ever been told to avoid deception. After the trials of horror and pain, they may or may not physically return to the world they came from.

Remember, a soldier isn’t a robot. The journey of a soldier is one of change the hard way. Consider taking your protagonist through the stages of the Kubler-Ross change curve .

From what I’ve read, soldiers in a war zone go through four immutable stages. You could send your protagonist through all four or assign individual stages to various supporting characters.

Stage One: This soldier just arrived. They think they’re in for an adventure and are sure they will survive. They don’t accept advice from senior soldiers or leaders. They’re special and this war gig is manageable without the need for personal change. Or, they underestimate the transformation they need to make to stay alive and honorable. They’re experiencing shock and denial. An example is Chris in the beginning of Platoon.

Stage Two: This soldier has seen combat and is changed by it. They recognize they’re in danger and institute caution. They implement change. Now they are accepting mentorship. In Platoon, Chris starts paying attention to Elias after Chris is accused of falling asleep on his shift and failing to prevent an attack.

Stage Three: They’ve seen enough to know the brutalities of war and the rules for staying alive. They are willing to share useful information with others. In Platoon , King, Elias, Rhah, and Lerner are all at this stage.

Stage Four : The soldier believes they are more likely to die than live through the war. They’ve seen the unexpected and horrific over a long period of time and now believe they’ve cheated death and luck longer than they deserve. In Platoon, Barnes reaches this state after he kills Elias.

Stage Five: Real soldiers rarely get clear resolutions but our protagonists require them. A War story must deliver meaning by dramatizing how the protagonist comes to integrate their experiences in war, even if it is in the short-term. In Platoon , Chris gives a monologue in the helicopter as he’s lifted off the battlefield that explains both his short-term and long-time thinking.