Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Do Thematic Analysis | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

How to Do Thematic Analysis | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on September 6, 2019 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Thematic analysis is a method of analyzing qualitative data . It is usually applied to a set of texts, such as an interview or transcripts . The researcher closely examines the data to identify common themes – topics, ideas and patterns of meaning that come up repeatedly.

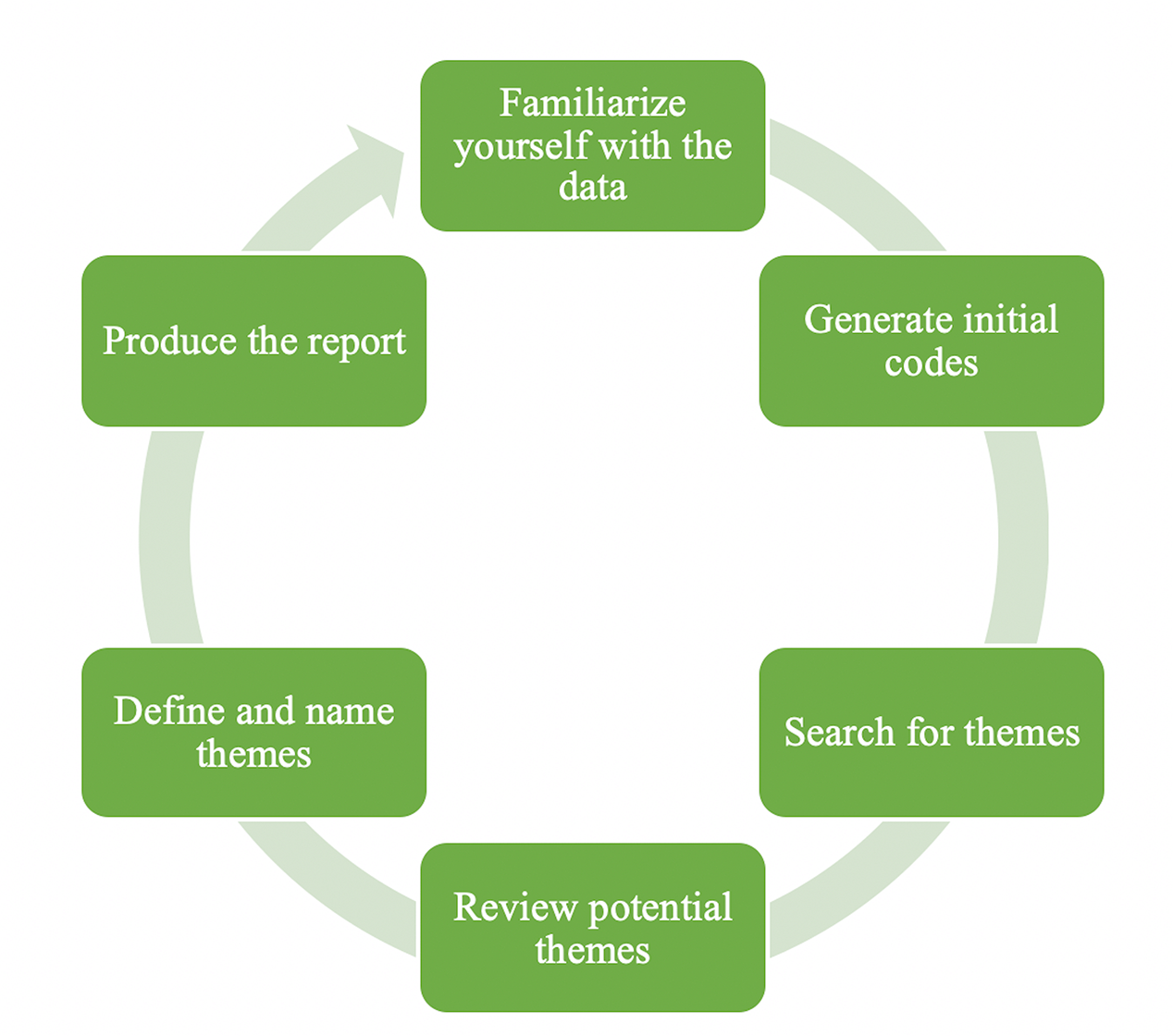

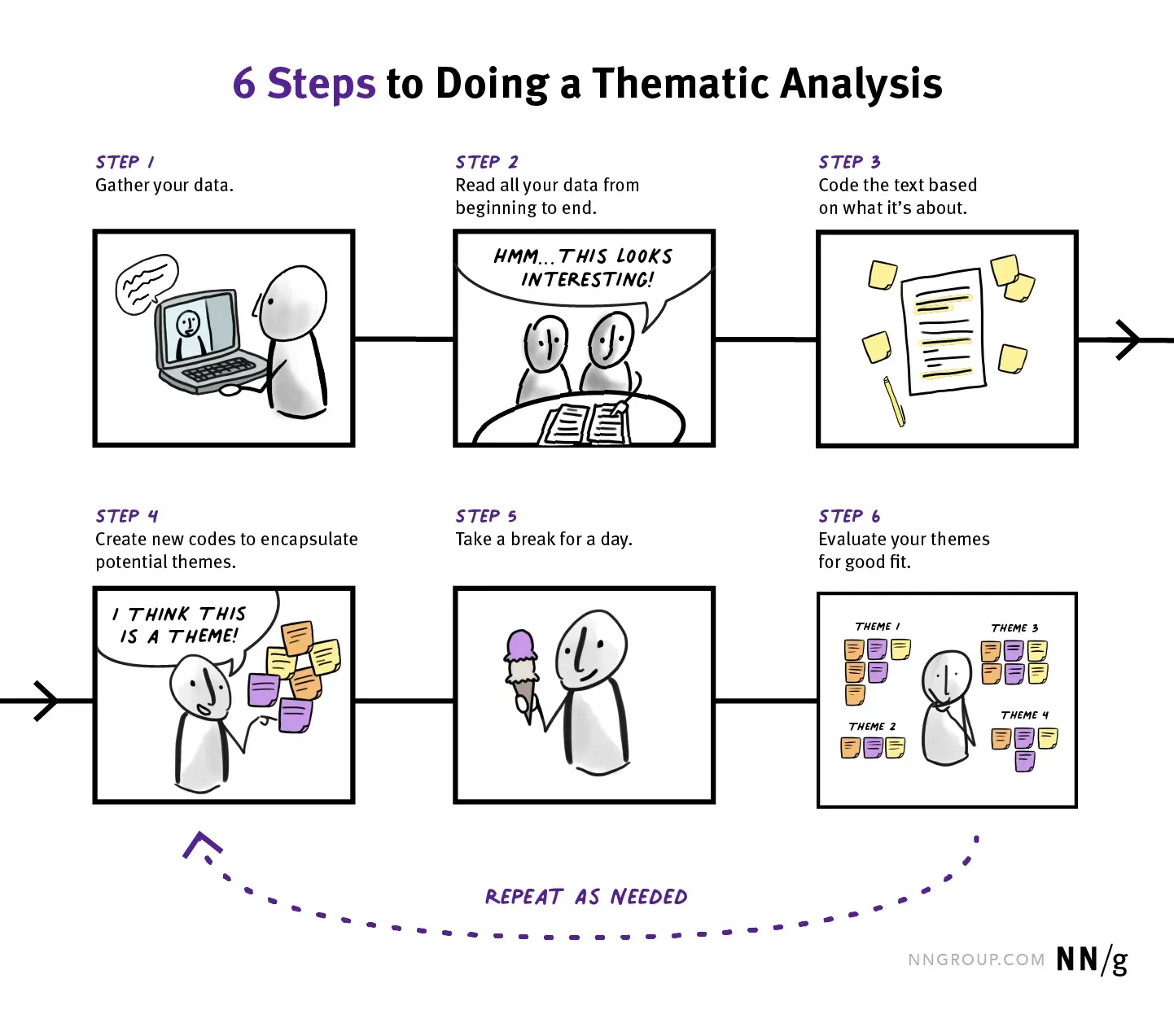

There are various approaches to conducting thematic analysis, but the most common form follows a six-step process: familiarization, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and writing up. Following this process can also help you avoid confirmation bias when formulating your analysis.

This process was originally developed for psychology research by Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke . However, thematic analysis is a flexible method that can be adapted to many different kinds of research.

Table of contents

When to use thematic analysis, different approaches to thematic analysis, step 1: familiarization, step 2: coding, step 3: generating themes, step 4: reviewing themes, step 5: defining and naming themes, step 6: writing up, other interesting articles.

Thematic analysis is a good approach to research where you’re trying to find out something about people’s views, opinions, knowledge, experiences or values from a set of qualitative data – for example, interview transcripts , social media profiles, or survey responses .

Some types of research questions you might use thematic analysis to answer:

- How do patients perceive doctors in a hospital setting?

- What are young women’s experiences on dating sites?

- What are non-experts’ ideas and opinions about climate change?

- How is gender constructed in high school history teaching?

To answer any of these questions, you would collect data from a group of relevant participants and then analyze it. Thematic analysis allows you a lot of flexibility in interpreting the data, and allows you to approach large data sets more easily by sorting them into broad themes.

However, it also involves the risk of missing nuances in the data. Thematic analysis is often quite subjective and relies on the researcher’s judgement, so you have to reflect carefully on your own choices and interpretations.

Pay close attention to the data to ensure that you’re not picking up on things that are not there – or obscuring things that are.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you’ve decided to use thematic analysis, there are different approaches to consider.

There’s the distinction between inductive and deductive approaches:

- An inductive approach involves allowing the data to determine your themes.

- A deductive approach involves coming to the data with some preconceived themes you expect to find reflected there, based on theory or existing knowledge.

Ask yourself: Does my theoretical framework give me a strong idea of what kind of themes I expect to find in the data (deductive), or am I planning to develop my own framework based on what I find (inductive)?

There’s also the distinction between a semantic and a latent approach:

- A semantic approach involves analyzing the explicit content of the data.

- A latent approach involves reading into the subtext and assumptions underlying the data.

Ask yourself: Am I interested in people’s stated opinions (semantic) or in what their statements reveal about their assumptions and social context (latent)?

After you’ve decided thematic analysis is the right method for analyzing your data, and you’ve thought about the approach you’re going to take, you can follow the six steps developed by Braun and Clarke .

The first step is to get to know our data. It’s important to get a thorough overview of all the data we collected before we start analyzing individual items.

This might involve transcribing audio , reading through the text and taking initial notes, and generally looking through the data to get familiar with it.

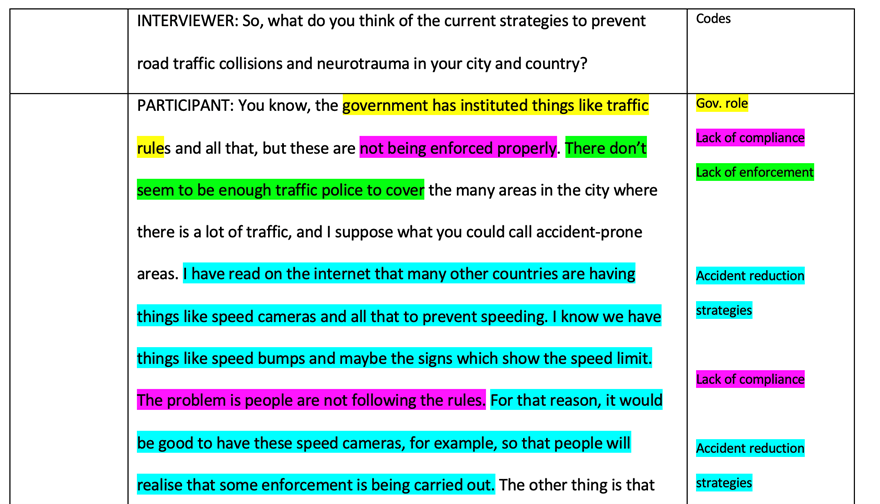

Next up, we need to code the data. Coding means highlighting sections of our text – usually phrases or sentences – and coming up with shorthand labels or “codes” to describe their content.

Let’s take a short example text. Say we’re researching perceptions of climate change among conservative voters aged 50 and up, and we have collected data through a series of interviews. An extract from one interview looks like this:

| Interview extract | Codes |

|---|---|

| Personally, I’m not sure. I think the climate is changing, sure, but I don’t know why or how. People say you should trust the experts, but who’s to say they don’t have their own reasons for pushing this narrative? I’m not saying they’re wrong, I’m just saying there’s reasons not to 100% trust them. The facts keep changing – it used to be called global warming. |

In this extract, we’ve highlighted various phrases in different colors corresponding to different codes. Each code describes the idea or feeling expressed in that part of the text.

At this stage, we want to be thorough: we go through the transcript of every interview and highlight everything that jumps out as relevant or potentially interesting. As well as highlighting all the phrases and sentences that match these codes, we can keep adding new codes as we go through the text.

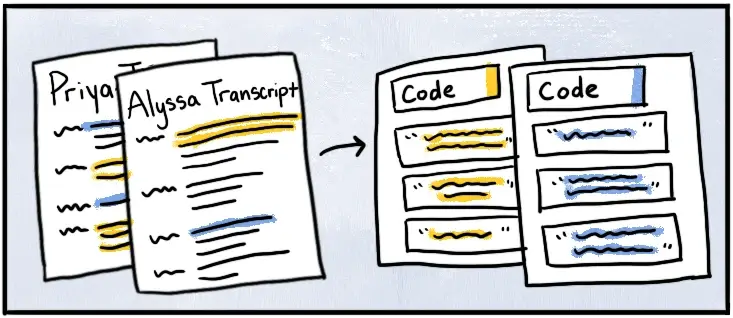

After we’ve been through the text, we collate together all the data into groups identified by code. These codes allow us to gain a a condensed overview of the main points and common meanings that recur throughout the data.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Next, we look over the codes we’ve created, identify patterns among them, and start coming up with themes.

Themes are generally broader than codes. Most of the time, you’ll combine several codes into a single theme. In our example, we might start combining codes into themes like this:

| Codes | Theme |

|---|---|

| Uncertainty | |

| Distrust of experts | |

| Misinformation |

At this stage, we might decide that some of our codes are too vague or not relevant enough (for example, because they don’t appear very often in the data), so they can be discarded.

Other codes might become themes in their own right. In our example, we decided that the code “uncertainty” made sense as a theme, with some other codes incorporated into it.

Again, what we decide will vary according to what we’re trying to find out. We want to create potential themes that tell us something helpful about the data for our purposes.

Now we have to make sure that our themes are useful and accurate representations of the data. Here, we return to the data set and compare our themes against it. Are we missing anything? Are these themes really present in the data? What can we change to make our themes work better?

If we encounter problems with our themes, we might split them up, combine them, discard them or create new ones: whatever makes them more useful and accurate.

For example, we might decide upon looking through the data that “changing terminology” fits better under the “uncertainty” theme than under “distrust of experts,” since the data labelled with this code involves confusion, not necessarily distrust.

Now that you have a final list of themes, it’s time to name and define each of them.

Defining themes involves formulating exactly what we mean by each theme and figuring out how it helps us understand the data.

Naming themes involves coming up with a succinct and easily understandable name for each theme.

For example, we might look at “distrust of experts” and determine exactly who we mean by “experts” in this theme. We might decide that a better name for the theme is “distrust of authority” or “conspiracy thinking”.

Finally, we’ll write up our analysis of the data. Like all academic texts, writing up a thematic analysis requires an introduction to establish our research question, aims and approach.

We should also include a methodology section, describing how we collected the data (e.g. through semi-structured interviews or open-ended survey questions ) and explaining how we conducted the thematic analysis itself.

The results or findings section usually addresses each theme in turn. We describe how often the themes come up and what they mean, including examples from the data as evidence. Finally, our conclusion explains the main takeaways and shows how the analysis has answered our research question.

In our example, we might argue that conspiracy thinking about climate change is widespread among older conservative voters, point out the uncertainty with which many voters view the issue, and discuss the role of misinformation in respondents’ perceptions.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, June 22). How to Do Thematic Analysis | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 13, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/thematic-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is qualitative research | methods & examples, inductive vs. deductive research approach | steps & examples, critical discourse analysis | definition, guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Practical thematic...

Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis

- Related content

- Peer review

- on behalf of the Coproduction Laboratory

- 1 Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 2 Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 3 Center for Primary Care and Public Health (Unisanté), Lausanne, Switzerland

- 4 Jönköping Academy for Improvement of Health and Welfare, School of Health and Welfare, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

- 5 Highland Park, NJ, USA

- 6 Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA

- Correspondence to: C H Saunders catherine.hylas.saunders{at}dartmouth.edu

- Accepted 26 April 2023

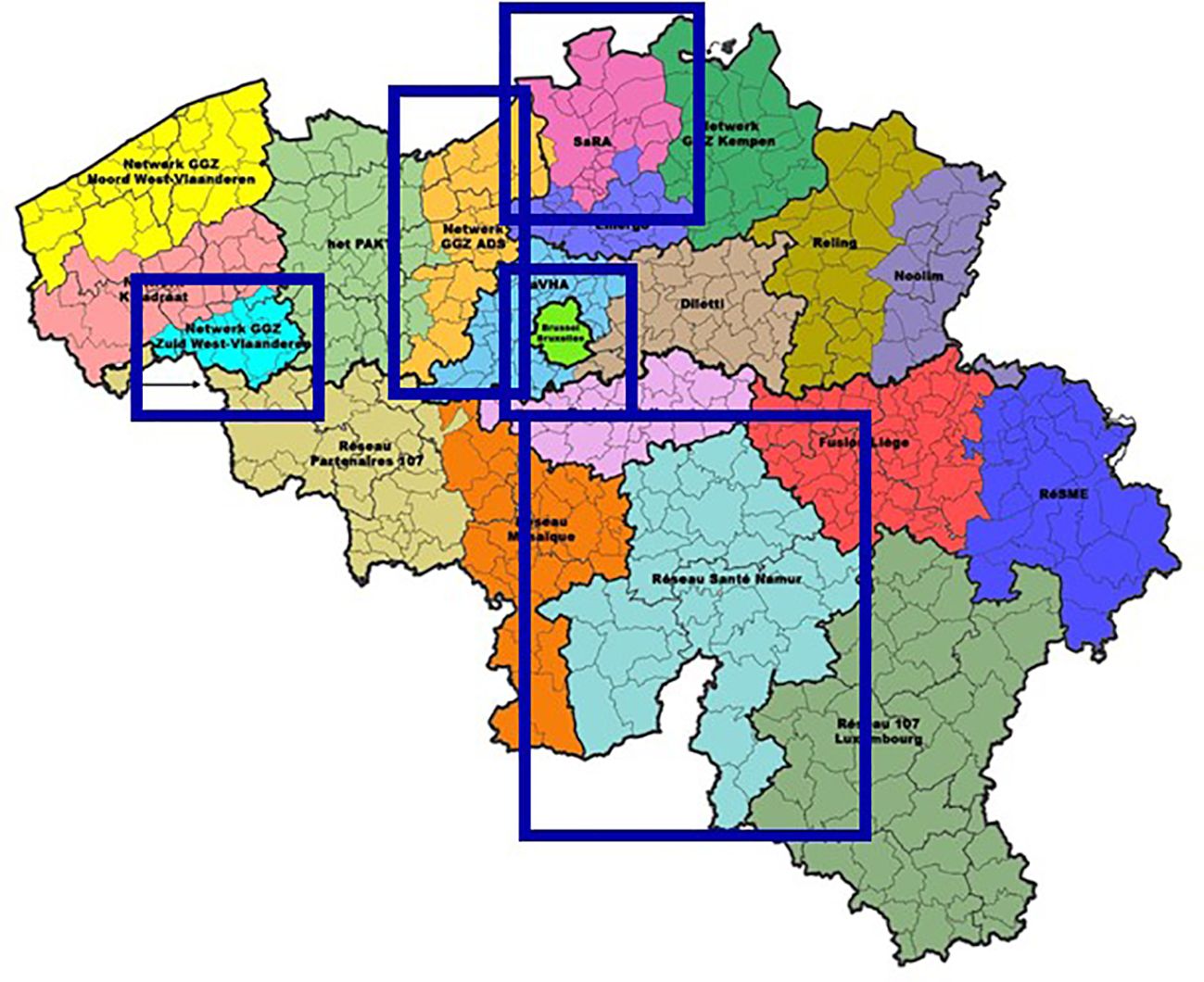

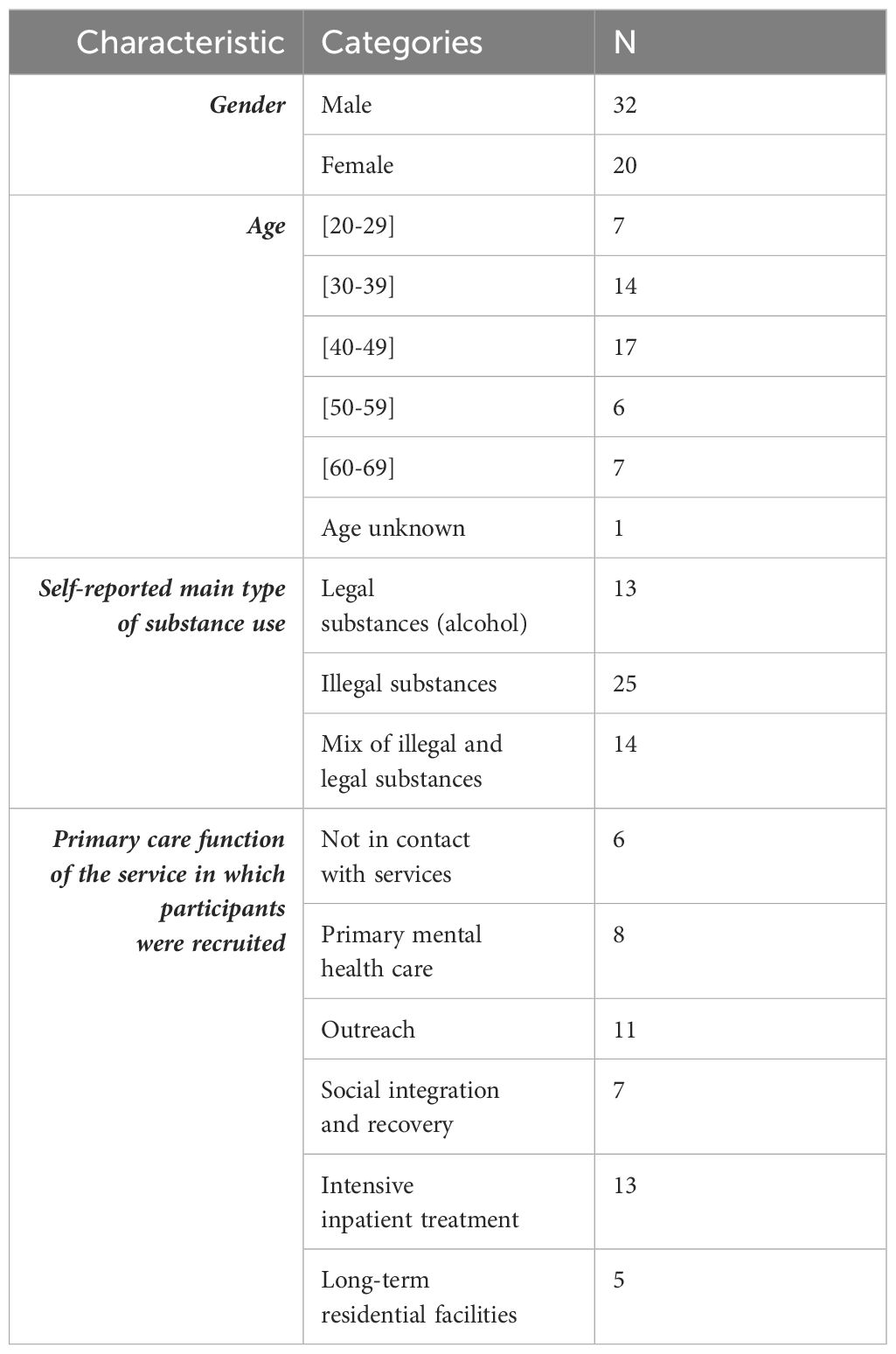

Qualitative research methods explore and provide deep contextual understanding of real world issues, including people’s beliefs, perspectives, and experiences. Whether through analysis of interviews, focus groups, structured observation, or multimedia data, qualitative methods offer unique insights in applied health services research that other approaches cannot deliver. However, many clinicians and researchers hesitate to use these methods, or might not use them effectively, which can leave relevant areas of inquiry inadequately explored. Thematic analysis is one of the most common and flexible methods to examine qualitative data collected in health services research. This article offers practical thematic analysis as a step-by-step approach to qualitative analysis for health services researchers, with a focus on accessibility for patients, care partners, clinicians, and others new to thematic analysis. Along with detailed instructions covering three steps of reading, coding, and theming, the article includes additional novel and practical guidance on how to draft effective codes, conduct a thematic analysis session, and develop meaningful themes. This approach aims to improve consistency and rigor in thematic analysis, while also making this method more accessible for multidisciplinary research teams.

Through qualitative methods, researchers can provide deep contextual understanding of real world issues, and generate new knowledge to inform hypotheses, theories, research, and clinical care. Approaches to data collection are varied, including interviews, focus groups, structured observation, and analysis of multimedia data, with qualitative research questions aimed at understanding the how and why of human experience. 1 2 Qualitative methods produce unique insights in applied health services research that other approaches cannot deliver. In particular, researchers acknowledge that thematic analysis is a flexible and powerful method of systematically generating robust qualitative research findings by identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. 3 4 5 6 Although qualitative methods are increasingly valued for answering clinical research questions, many researchers are unsure how to apply them or consider them too time consuming to be useful in responding to practical challenges 7 or pressing situations such as public health emergencies. 8 Consequently, researchers might hesitate to use them, or use them improperly. 9 10 11

Although much has been written about how to perform thematic analysis, practical guidance for non-specialists is sparse. 3 5 6 12 13 In the multidisciplinary field of health services research, qualitative data analysis can confound experienced researchers and novices alike, which can stoke concerns about rigor, particularly for those more familiar with quantitative approaches. 14 Since qualitative methods are an area of specialisation, support from experts is beneficial. However, because non-specialist perspectives can enhance data interpretation and enrich findings, there is a case for making thematic analysis easier, more rapid, and more efficient, 8 particularly for patients, care partners, clinicians, and other stakeholders. A practical guide to thematic analysis might encourage those on the ground to use these methods in their work, unearthing insights that would otherwise remain undiscovered.

Given the need for more accessible qualitative analysis approaches, we present a simple, rigorous, and efficient three step guide for practical thematic analysis. We include new guidance on the mechanics of thematic analysis, including developing codes, constructing meaningful themes, and hosting a thematic analysis session. We also discuss common pitfalls in thematic analysis and how to avoid them.

Summary points

Qualitative methods are increasingly valued in applied health services research, but multidisciplinary research teams often lack accessible step-by-step guidance and might struggle to use these approaches

A newly developed approach, practical thematic analysis, uses three simple steps: reading, coding, and theming

Based on Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, our streamlined yet rigorous approach is designed for multidisciplinary health services research teams, including patients, care partners, and clinicians

This article also provides companion materials including a slide presentation for teaching practical thematic analysis to research teams, a sample thematic analysis session agenda, a theme coproduction template for use during the session, and guidance on using standardised reporting criteria for qualitative research

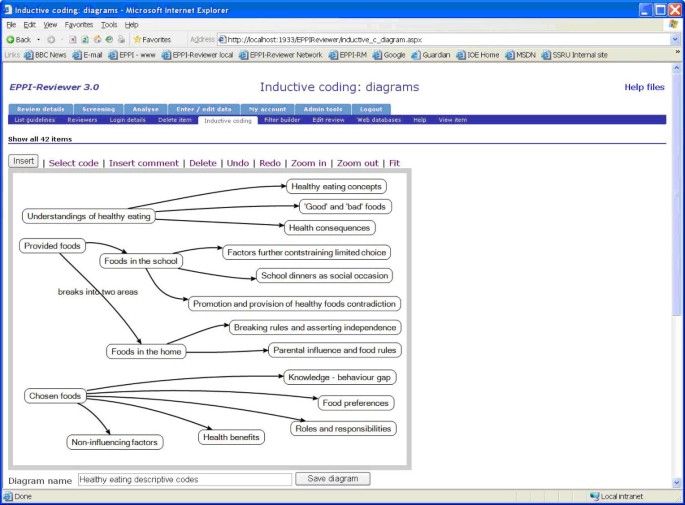

In their seminal work, Braun and Clarke developed a six phase approach to reflexive thematic analysis. 4 12 We built on their method to develop practical thematic analysis ( box 1 , fig 1 ), which is a simplified and instructive approach that retains the substantive elements of their six phases. Braun and Clarke’s phase 1 (familiarising yourself with the dataset) is represented in our first step of reading. Phase 2 (coding) remains as our second step of coding. Phases 3 (generating initial themes), 4 (developing and reviewing themes), and 5 (refining, defining, and naming themes) are represented in our third step of theming. Phase 6 (writing up) also occurs during this third step of theming, but after a thematic analysis session. 4 12

Key features and applications of practical thematic analysis

Step 1: reading.

All manuscript authors read the data

All manuscript authors write summary memos

Step 2: Coding

Coders perform both data management and early data analysis

Codes are complete thoughts or sentences, not categories

Step 3: Theming

Researchers host a thematic analysis session and share different perspectives

Themes are complete thoughts or sentences, not categories

Applications

For use by practicing clinicians, patients and care partners, students, interdisciplinary teams, and those new to qualitative research

When important insights from healthcare professionals are inaccessible because they do not have qualitative methods training

When time and resources are limited

Steps in practical thematic analysis

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

We present linear steps, but as qualitative research is usually iterative, so too is thematic analysis. 15 Qualitative researchers circle back to earlier work to check whether their interpretations still make sense in the light of additional insights, adapting as necessary. While we focus here on the practical application of thematic analysis in health services research, we recognise our approach exists in the context of the broader literature on thematic analysis and the theoretical underpinnings of qualitative methods as a whole. For a more detailed discussion of these theoretical points, as well as other methods widely used in health services research, we recommend reviewing the sources outlined in supplemental material 1. A strong and nuanced understanding of the context and underlying principles of thematic analysis will allow for higher quality research. 16

Practical thematic analysis is a highly flexible approach that can draw out valuable findings and generate new hypotheses, including in cases with a lack of previous research to build on. The approach can also be used with a variety of data, such as transcripts from interviews or focus groups, patient encounter transcripts, professional publications, observational field notes, and online activity logs. Importantly, successful practical thematic analysis is predicated on having high quality data collected with rigorous methods. We do not describe qualitative research design or data collection here. 11 17

In supplemental material 1, we summarise the foundational methods, concepts, and terminology in qualitative research. Along with our guide below, we include a companion slide presentation for teaching practical thematic analysis to research teams in supplemental material 2. We provide a theme coproduction template for teams to use during thematic analysis sessions in supplemental material 3. Our method aligns with the major qualitative reporting frameworks, including the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ). 18 We indicate the corresponding step in practical thematic analysis for each COREQ item in supplemental material 4.

Familiarisation and memoing

We encourage all manuscript authors to review the full dataset (eg, interview transcripts) to familiarise themselves with it. This task is most critical for those who will later be engaged in the coding and theming steps. Although time consuming, it is the best way to involve team members in the intellectual work of data interpretation, so that they can contribute to the analysis and contextualise the results. If this task is not feasible given time limitations or large quantities of data, the data can be divided across team members. In this case, each piece of data should be read by at least two individuals who ideally represent different professional roles or perspectives.

We recommend that researchers reflect on the data and independently write memos, defined as brief notes on thoughts and questions that arise during reading, and a summary of their impressions of the dataset. 2 19 Memoing is an opportunity to gain insights from varying perspectives, particularly from patients, care partners, clinicians, and others. It also gives researchers the opportunity to begin to scope which elements of and concepts in the dataset are relevant to the research question.

Data saturation

The concept of data saturation ( box 2 ) is a foundation of qualitative research. It is defined as the point in analysis at which new data tend to be redundant of data already collected. 21 Qualitative researchers are expected to report their approach to data saturation. 18 Because thematic analysis is iterative, the team should discuss saturation throughout the entire process, beginning with data collection and continuing through all steps of the analysis. 22 During step 1 (reading), team members might discuss data saturation in the context of summary memos. Conversations about saturation continue during step 2 (coding), with confirmation that saturation has been achieved during step 3 (theming). As a rule of thumb, researchers can often achieve saturation in 9-17 interviews or 4-8 focus groups, but this will vary depending on the specific characteristics of the study. 23

Data saturation in context

Braun and Clarke discourage the use of data saturation to determine sample size (eg, number of interviews), because it assumes that there is an objective truth to be captured in the data (sometimes known as a positivist perspective). 20 Qualitative researchers often try to avoid positivist approaches, arguing that there is no one true way of seeing the world, and will instead aim to gather multiple perspectives. 5 Although this theoretical debate with qualitative methods is important, we recognise that a priori estimates of saturation are often needed, particularly for investigators newer to qualitative research who might want a more pragmatic and applied approach. In addition, saturation based, sample size estimation can be particularly helpful in grant proposals. However, researchers should still follow a priori sample size estimation with a discussion to confirm saturation has been achieved.

Definition of coding

We describe codes as labels for concepts in the data that are directly relevant to the study objective. Historically, the purpose of coding was to distil the large amount of data collected into conceptually similar buckets so that researchers could review it in aggregate and identify key themes. 5 24 We advocate for a more analytical approach than is typical with thematic analysis. With our method, coding is both the foundation for and the beginning of thematic analysis—that is, early data analysis, management, and reduction occur simultaneously rather than as different steps. This approach moves the team more efficiently towards being able to describe themes.

Building the coding team

Coders are the research team members who directly assign codes to the data, reading all material and systematically labelling relevant data with appropriate codes. Ideally, at least two researchers would code every discrete data document, such as one interview transcript. 25 If this task is not possible, individual coders can each code a subset of the data that is carefully selected for key characteristics (sometimes known as purposive selection). 26 When using this approach, we recommend that at least 10% of data be coded by two or more coders to ensure consistency in codebook application. We also recommend coding teams of no more than four to five people, for practical reasons concerning maintaining consistency.

Clinicians, patients, and care partners bring unique perspectives to coding and enrich the analytical process. 27 Therefore, we recommend choosing coders with a mix of relevant experiences so that they can challenge and contextualise each other’s interpretations based on their own perspectives and opinions ( box 3 ). We recommend including both coders who collected the data and those who are naive to it, if possible, given their different perspectives. We also recommend all coders review the summary memos from the reading step so that key concepts identified by those not involved in coding can be integrated into the analytical process. In practice, this review means coding the memos themselves and discussing them during the code development process. This approach ensures that the team considers a diversity of perspectives.

Coding teams in context

The recommendation to use multiple coders is a departure from Braun and Clarke. 28 29 When the views, experiences, and training of each coder (sometimes known as positionality) 30 are carefully considered, having multiple coders can enhance interpretation and enrich findings. When these perspectives are combined in a team setting, researchers can create shared meaning from the data. Along with the practical consideration of distributing the workload, 31 inclusion of these multiple perspectives increases the overall quality of the analysis by mitigating the impact of any one coder’s perspective. 30

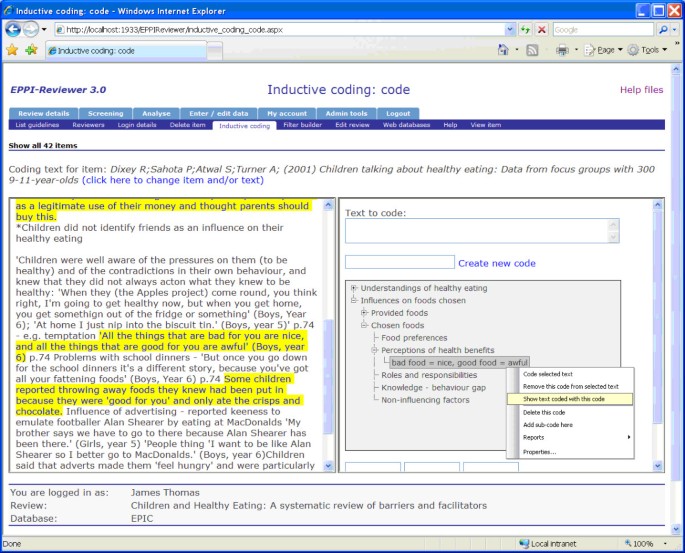

Coding tools

Qualitative analysis software facilitates coding and managing large datasets but does not perform the analytical work. The researchers must perform the analysis themselves. Most programs support queries and collaborative coding by multiple users. 32 Important factors to consider when choosing software can include accessibility, cost, interoperability, the look and feel of code reports, and the ease of colour coding and merging codes. Coders can also use low tech solutions, including highlighters, word processors, or spreadsheets.

Drafting effective codes

To draft effective codes, we recommend that the coders review each document line by line. 33 As they progress, they can assign codes to segments of data representing passages of interest. 34 Coders can also assign multiple codes to the same passage. Consensus among coders on what constitutes a minimum or maximum amount of text for assigning a code is helpful. As a general rule, meaningful segments of text for coding are shorter than one paragraph, but longer than a few words. Coders should keep the study objective in mind when determining which data are relevant ( box 4 ).

Code types in context

Similar to Braun and Clarke’s approach, practical thematic analysis does not specify whether codes are based on what is evident from the data (sometimes known as semantic) or whether they are based on what can be inferred at a deeper level from the data (sometimes known as latent). 4 12 35 It also does not specify whether they are derived from the data (sometimes known as inductive) or determined ahead of time (sometimes known as deductive). 11 35 Instead, it should be noted that health services researchers conducting qualitative studies often adopt all these approaches to coding (sometimes known as hybrid analysis). 3

In practical thematic analysis, codes should be more descriptive than general categorical labels that simply group data with shared characteristics. At a minimum, codes should form a complete (or full) thought. An easy way to conceptualise full thought codes is as complete sentences with subjects and verbs ( table 1 ), although full sentence coding is not always necessary. With full thought codes, researchers think about the data more deeply and capture this insight in the codes. This coding facilitates the entire analytical process and is especially valuable when moving from codes to broader themes. Experienced qualitative researchers often intuitively use full thought or sentence codes, but this practice has not been explicitly articulated as a path to higher quality coding elsewhere in the literature. 6

Example transcript with codes used in practical thematic analysis 36

- View inline

Depending on the nature of the data, codes might either fall into flat categories or be arranged hierarchically. Flat categories are most common when the data deal with topics on the same conceptual level. In other words, one topic is not a subset of another topic. By contrast, hierarchical codes are more appropriate for concepts that naturally fall above or below each other. Hierarchical coding can also be a useful form of data management and might be necessary when working with a large or complex dataset. 5 Codes grouped into these categories can also make it easier to naturally transition into generating themes from the initial codes. 5 These decisions between flat versus hierarchical coding are part of the work of the coding team. In both cases, coders should ensure that their code structures are guided by their research questions.

Developing the codebook

A codebook is a shared document that lists code labels and comprehensive descriptions for each code, as well as examples observed within the data. Good code descriptions are precise and specific so that coders can consistently assign the same codes to relevant data or articulate why another coder would do so. Codebook development is iterative and involves input from the entire coding team. However, as those closest to the data, coders must resist undue influence, real or perceived, from other team members with conflicting opinions—it is important to mitigate the risk that more senior researchers, like principal investigators, exert undue influence on the coders’ perspectives.

In practical thematic analysis, coders begin codebook development by independently coding a small portion of the data, such as two to three transcripts or other units of analysis. Coders then individually produce their initial codebooks. This task will require them to reflect on, organise, and clarify codes. The coders then meet to reconcile the draft codebooks, which can often be difficult, as some coders tend to lump several concepts together while others will split them into more specific codes. Discussing disagreements and negotiating consensus are necessary parts of early data analysis. Once the codebook is relatively stable, we recommend soliciting input on the codes from all manuscript authors. Yet, coders must ultimately be empowered to finalise the details so that they are comfortable working with the codebook across a large quantity of data.

Assigning codes to the data

After developing the codebook, coders will use it to assign codes to the remaining data. While the codebook’s overall structure should remain constant, coders might continue to add codes corresponding to any new concepts observed in the data. If new codes are added, coders should review the data they have already coded and determine whether the new codes apply. Qualitative data analysis software can be useful for editing or merging codes.

We recommend that coders periodically compare their code occurrences ( box 5 ), with more frequent check-ins if substantial disagreements occur. In the event of large discrepancies in the codes assigned, coders should revise the codebook to ensure that code descriptions are sufficiently clear and comprehensive to support coding alignment going forward. Because coding is an iterative process, the team can adjust the codebook as needed. 5 28 29

Quantitative coding in context

Researchers should generally avoid reporting code counts in thematic analysis. However, counts can be a useful proxy in maintaining alignment between coders on key concepts. 26 In practice, therefore, researchers should make sure that all coders working on the same piece of data assign the same codes with a similar pattern and that their memoing and overall assessment of the data are aligned. 37 However, the frequency of a code alone is not an indicator of its importance. It is more important that coders agree on the most salient points in the data; reviewing and discussing summary memos can be helpful here. 5

Researchers might disagree on whether or not to calculate and report inter-rater reliability. We note that quantitative tests for agreement, such as kappa statistics or intraclass correlation coefficients, can be distracting and might not provide meaningful results in qualitative analyses. Similarly, Braun and Clarke argue that expecting perfect alignment on coding is inconsistent with the goal of co-constructing meaning. 28 29 Overall consensus on codes’ salience and contributions to themes is the most important factor.

Definition of themes

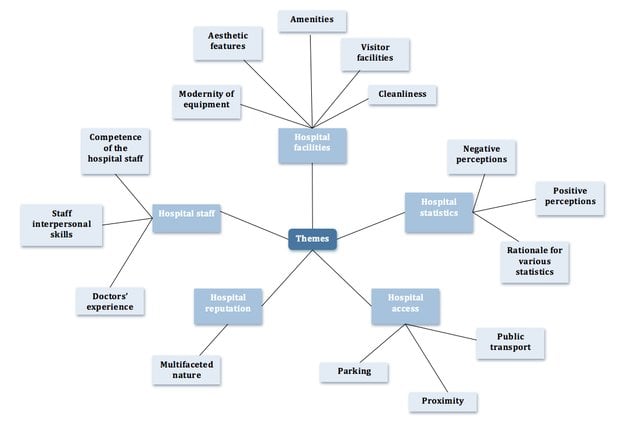

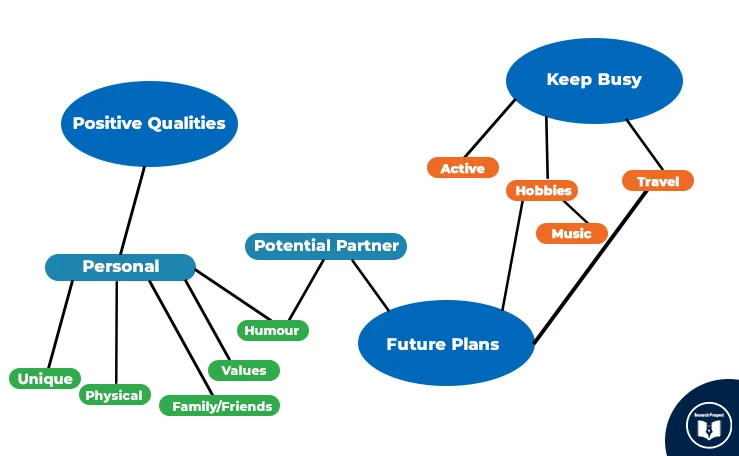

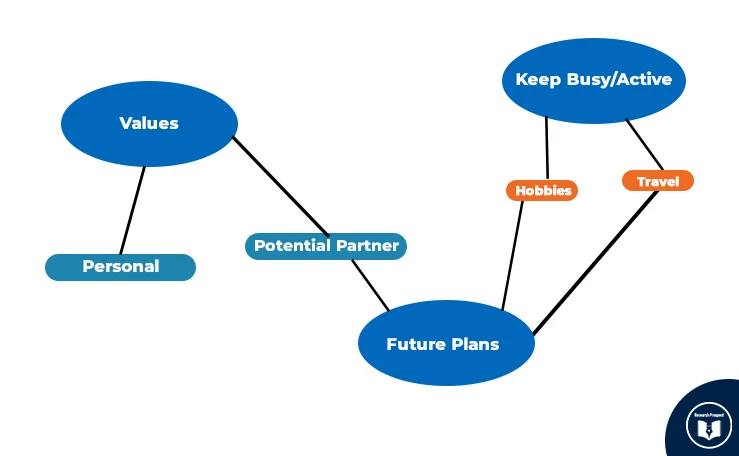

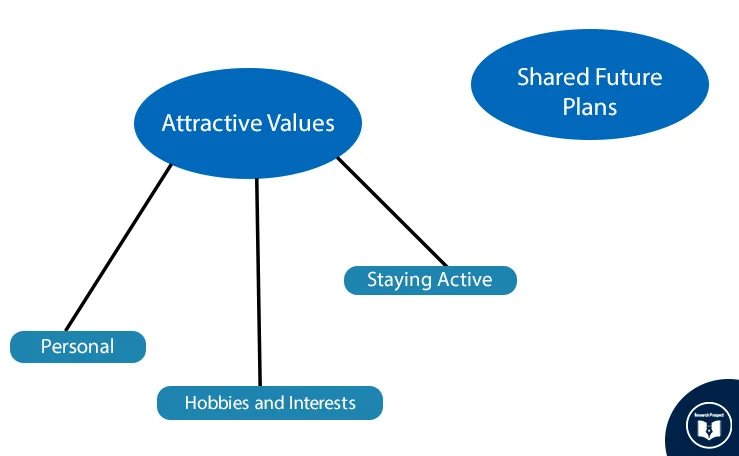

Themes are meta-constructs that rise above codes and unite the dataset ( box 6 , fig 2 ). They should be clearly evident, repeated throughout the dataset, and relevant to the research questions. 38 While codes are often explicit descriptions of the content in the dataset, themes are usually more conceptual and knit the codes together. 39 Some researchers hypothesise that theme development is loosely described in the literature because qualitative researchers simply intuit themes during the analytical process. 39 In practical thematic analysis, we offer a concrete process that should make developing meaningful themes straightforward.

Themes in context

According to Braun and Clarke, a theme “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set.” 4 Similarly, Braun and Clarke advise against themes as domain summaries. While different approaches can draw out themes from codes, the process begins by identifying patterns. 28 35 Like Braun and Clarke and others, we recommend that researchers consider the salience of certain themes, their prevalence in the dataset, and their keyness (ie, how relevant the themes are to the overarching research questions). 4 12 34

Use of themes in practical thematic analysis

Constructing meaningful themes

After coding all the data, each coder should independently reflect on the team’s summary memos (step 1), the codebook (step 2), and the coded data itself to develop draft themes (step 3). It can be illuminating for coders to review all excerpts associated with each code, so that they derive themes directly from the data. Researchers should remain focused on the research question during this step, so that themes have a clear relation with the overall project aim. Use of qualitative analysis software will make it easy to view each segment of data tagged with each code. Themes might neatly correspond to groups of codes. Or—more likely—they will unite codes and data in unexpected ways. A whiteboard or presentation slides might be helpful to organise, craft, and revise themes. We also provide a template for coproducing themes (supplemental material 3). As with codebook justification, team members will ideally produce individual drafts of the themes that they have identified in the data. They can then discuss these with the group and reach alignment or consensus on the final themes.

The team should ensure that all themes are salient, meaning that they are: supported by the data, relevant to the study objectives, and important. Similar to codes, themes are framed as complete thoughts or sentences, not categories. While codes and themes might appear to be similar to each other, the key distinction is that the themes represent a broader concept. Table 2 shows examples of codes and their corresponding themes from a previously published project that used practical thematic analysis. 36 Identifying three to four key themes that comprise a broader overarching theme is a useful approach. Themes can also have subthemes, if appropriate. 40 41 42 43 44

Example codes with themes in practical thematic analysis 36

Thematic analysis session

After each coder has independently produced draft themes, a carefully selected subset of the manuscript team meets for a thematic analysis session ( table 3 ). The purpose of this session is to discuss and reach alignment or consensus on the final themes. We recommend a session of three to five hours, either in-person or virtually.

Example agenda of thematic analysis session

The composition of the thematic analysis session team is important, as each person’s perspectives will shape the results. This group is usually a small subset of the broader research team, with three to seven individuals. We recommend that primary and senior authors work together to include people with diverse experiences related to the research topic. They should aim for a range of personalities and professional identities, particularly those of clinicians, trainees, patients, and care partners. At a minimum, all coders and primary and senior authors should participate in the thematic analysis session.

The session begins with each coder presenting their draft themes with supporting quotes from the data. 5 Through respectful and collaborative deliberation, the group will develop a shared set of final themes.

One team member facilitates the session. A firm, confident, and consistent facilitation style with good listening skills is critical. For practical reasons, this person is not usually one of the primary coders. Hierarchies in teams cannot be entirely flattened, but acknowledging them and appointing an external facilitator can reduce their impact. The facilitator can ensure that all voices are heard. For example, they might ask for perspectives from patient partners or more junior researchers, and follow up on comments from senior researchers to say, “We have heard your perspective and it is important; we want to make sure all perspectives in the room are equally considered.” Or, “I hear [senior person] is offering [x] idea, I’d like to hear other perspectives in the room.” The role of the facilitator is critical in the thematic analysis session. The facilitator might also privately discuss with more senior researchers, such as principal investigators and senior authors, the importance of being aware of their influence over others and respecting and eliciting the perspectives of more junior researchers, such as patients, care partners, and students.

To our knowledge, this discrete thematic analysis session is a novel contribution of practical thematic analysis. It helps efficiently incorporate diverse perspectives using the session agenda and theme coproduction template (supplemental material 3) and makes the process of constructing themes transparent to the entire research team.

Writing the report

We recommend beginning the results narrative with a summary of all relevant themes emerging from the analysis, followed by a subheading for each theme. Each subsection begins with a brief description of the theme and is illustrated with relevant quotes, which are contextualised and explained. The write-up should not simply be a list, but should contain meaningful analysis and insight from the researchers, including descriptions of how different stakeholders might have experienced a particular situation differently or unexpectedly.

In addition to weaving quotes into the results narrative, quotes can be presented in a table. This strategy is a particularly helpful when submitting to clinical journals with tight word count limitations. Quote tables might also be effective in illustrating areas of agreement and disagreement across stakeholder groups, with columns representing different groups and rows representing each theme or subtheme. Quotes should include an anonymous label for each participant and any relevant characteristics, such as role or gender. The aim is to produce rich descriptions. 5 We recommend against repeating quotations across multiple themes in the report, so as to avoid confusion. The template for coproducing themes (supplemental material 3) allows documentation of quotes supporting each theme, which might also be useful during report writing.

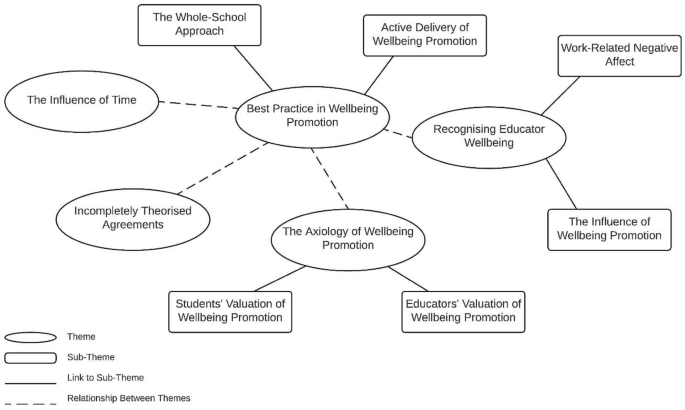

Visual illustrations such as a thematic map or figure of the findings can help communicate themes efficiently. 4 36 42 44 If a figure is not possible, a simple list can suffice. 36 Both must clearly present the main themes with subthemes. Thematic figures can facilitate confirmation that the researchers’ interpretations reflect the study populations’ perspectives (sometimes known as member checking), because authors can invite discussions about the figure and descriptions of findings and supporting quotes. 46 This process can enhance the validity of the results. 46

In supplemental material 4, we provide additional guidance on reporting thematic analysis consistent with COREQ. 18 Commonly used in health services research, COREQ outlines a standardised list of items to be included in qualitative research reports ( box 7 ).

Reporting in context

We note that use of COREQ or any other reporting guidelines does not in itself produce high quality work and should not be used as a substitute for general methodological rigor. Rather, researchers must consider rigor throughout the entire research process. As the issue of how to conceptualise and achieve rigorous qualitative research continues to be debated, 47 48 we encourage researchers to explicitly discuss how they have looked at methodological rigor in their reports. Specifically, we point researchers to Braun and Clarke’s 2021 tool for evaluating thematic analysis manuscripts for publication (“Twenty questions to guide assessment of TA [thematic analysis] research quality”). 16

Avoiding common pitfalls

Awareness of common mistakes can help researchers avoid improper use of qualitative methods. Improper use can, for example, prevent researchers from developing meaningful themes and can risk drawing inappropriate conclusions from the data. Braun and Clarke also warn of poor quality in qualitative research, noting that “coherence and integrity of published research does not always hold.” 16

Weak themes

An important distinction between high and low quality themes is that high quality themes are descriptive and complete thoughts. As such, they often contain subjects and verbs, and can be expressed as full sentences ( table 2 ). Themes that are simply descriptive categories or topics could fail to impart meaningful knowledge beyond categorisation. 16 49 50

Researchers will often move from coding directly to writing up themes, without performing the work of theming or hosting a thematic analysis session. Skipping concerted theming often results in themes that look more like categories than unifying threads across the data.

Unfocused analysis

Because data collection for qualitative research is often semi-structured (eg, interviews, focus groups), not all data will be directly relevant to the research question at hand. To avoid unfocused analysis and a correspondingly unfocused manuscript, we recommend that all team members keep the research objective in front of them at every stage, from reading to coding to theming. During the thematic analysis session, we recommend that the research question be written on a whiteboard so that all team members can refer back to it, and so that the facilitator can ensure that conversations about themes occur in the context of this question. Consistently focusing on the research question can help to ensure that the final report directly answers it, as opposed to the many other interesting insights that might emerge during the qualitative research process. Such insights can be picked up in a secondary analysis if desired.

Inappropriate quantification

Presenting findings quantitatively (eg, “We found 18 instances of participants mentioning safety concerns about the vaccines”) is generally undesirable in practical thematic analysis reporting. 51 Descriptive terms are more appropriate (eg, “participants had substantial concerns about the vaccines,” or “several participants were concerned about this”). This descriptive presentation is critical because qualitative data might not be consistently elicited across participants, meaning that some individuals might share certain information while others do not, simply based on how conversations evolve. Additionally, qualitative research does not aim to draw inferences outside its specific sample. Emphasising numbers in thematic analysis can lead to readers incorrectly generalising the findings. Although peer reviewers unfamiliar with thematic analysis often request this type of quantification, practitioners of practical thematic analysis can confidently defend their decision to avoid it. If quantification is methodologically important, we recommend simultaneously conducting a survey or incorporating standardised interview techniques into the interview guide. 11

Neglecting group dynamics

Researchers should concertedly consider group dynamics in the research team. Particular attention should be paid to power relations and the personality of team members, which can include aspects such as who most often speaks, who defines concepts, and who resolves disagreements that might arise within the group. 52

The perspectives of patient and care partners are particularly important to cultivate. Ideally, patient partners are meaningfully embedded in studies from start to finish, not just for practical thematic analysis. 53 Meaningful engagement can build trust, which makes it easier for patient partners to ask questions, request clarification, and share their perspectives. Professional team members should actively encourage patient partners by emphasising that their expertise is critically important and valued. Noting when a patient partner might be best positioned to offer their perspective can be particularly powerful.

Insufficient time allocation

Researchers must allocate enough time to complete thematic analysis. Working with qualitative data takes time, especially because it is often not a linear process. As the strength of thematic analysis lies in its ability to make use of the rich details and complexities of the data, we recommend careful planning for the time required to read and code each document.

Estimating the necessary time can be challenging. For step 1 (reading), researchers can roughly calculate the time required based on the time needed to read and reflect on one piece of data. For step 2 (coding), the total amount of time needed can be extrapolated from the time needed to code one document during codebook development. We also recommend three to five hours for the thematic analysis session itself, although coders will need to independently develop their draft themes beforehand. Although the time required for practical thematic analysis is variable, teams should be able to estimate their own required effort with these guidelines.

Practical thematic analysis builds on the foundational work of Braun and Clarke. 4 16 We have reframed their six phase process into three condensed steps of reading, coding, and theming. While we have maintained important elements of Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, we believe that practical thematic analysis is conceptually simpler and easier to teach to less experienced researchers and non-researcher stakeholders. For teams with different levels of familiarity with qualitative methods, this approach presents a clear roadmap to the reading, coding, and theming of qualitative data. Our practical thematic analysis approach promotes efficient learning by doing—experiential learning. 12 29 Practical thematic analysis avoids the risk of relying on complex descriptions of methods and theory and places more emphasis on obtaining meaningful insights from those close to real world clinical environments. Although practical thematic analysis can be used to perform intensive theory based analyses, it lends itself more readily to accelerated, pragmatic approaches.

Strengths and limitations

Our approach is designed to smooth the qualitative analysis process and yield high quality themes. Yet, researchers should note that poorly performed analyses will still produce low quality results. Practical thematic analysis is a qualitative analytical approach; it does not look at study design, data collection, or other important elements of qualitative research. It also might not be the right choice for every qualitative research project. We recommend it for applied health services research questions, where diverse perspectives and simplicity might be valuable.

We also urge researchers to improve internal validity through triangulation methods, such as member checking (supplemental material 1). 46 Member checking could include soliciting input on high level themes, theme definitions, and quotations from participants. This approach might increase rigor.

Implications

We hope that by providing clear and simple instructions for practical thematic analysis, a broader range of researchers will be more inclined to use these methods. Increased transparency and familiarity with qualitative approaches can enhance researchers’ ability to both interpret qualitative studies and offer up new findings themselves. In addition, it can have usefulness in training and reporting. A major strength of this approach is to facilitate meaningful inclusion of patient and care partner perspectives, because their lived experiences can be particularly valuable in data interpretation and the resulting findings. 11 30 As clinicians are especially pressed for time, they might also appreciate a practical set of instructions that can be immediately used to leverage their insights and access to patients and clinical settings, and increase the impact of qualitative research through timely results. 8

Practical thematic analysis is a simplified approach to performing thematic analysis in health services research, a field where the experiences of patients, care partners, and clinicians are of inherent interest. We hope that it will be accessible to those individuals new to qualitative methods, including patients, care partners, clinicians, and other health services researchers. We intend to empower multidisciplinary research teams to explore unanswered questions and make new, important, and rigorous contributions to our understanding of important clinical and health systems research.

Acknowledgments

All members of the Coproduction Laboratory provided input that shaped this manuscript during laboratory meetings. We acknowledge advice from Elizabeth Carpenter-Song, an expert in qualitative methods.

Coproduction Laboratory group contributors: Stephanie C Acquilano ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1215-5531 ), Julie Doherty ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5279-6536 ), Rachel C Forcino ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9938-4830 ), Tina Foster ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6239-4031 ), Megan Holthoff, Christopher R Jacobs ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5324-8657 ), Lisa C Johnson ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7448-4931 ), Elaine T Kiriakopoulos, Kathryn Kirkland ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9851-926X ), Meredith A MacMartin ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6614-6091 ), Emily A Morgan, Eugene Nelson, Elizabeth O’Donnell, Brant Oliver ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7399-622X ), Danielle Schubbe ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9858-1805 ), Gabrielle Stevens ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9001-178X ), Rachael P Thomeer ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5974-3840 ).

Contributors: Practical thematic analysis, an approach designed for multidisciplinary health services teams new to qualitative research, was based on CHS’s experiences teaching thematic analysis to clinical teams and students. We have drawn heavily from qualitative methods literature. CHS is the guarantor of the article. CHS, AS, CvP, AMK, JRK, and JAP contributed to drafting the manuscript. AS, JG, CMM, JAP, and RWY provided feedback on their experiences using practical thematic analysis. CvP, LCL, SLB, AVC, GE, and JKL advised on qualitative methods in health services research, given extensive experience. All authors meaningfully edited the manuscript content, including AVC and RKS. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This manuscript did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Ziebland S ,

- ↵ A Hybrid Approach to Thematic Analysis in Qualitative Research: Using a Practical Example. 2018. https://methods.sagepub.com/case/hybrid-approach-thematic-analysis-qualitative-research-a-practical-example .

- Maguire M ,

- Vindrola-Padros C ,

- Vindrola-Padros B

- ↵ Vindrola-Padros C. Rapid Ethnographies: A Practical Guide . Cambridge University Press 2021. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=n80HEAAAQBAJ

- Schroter S ,

- Merino JG ,

- Barbeau A ,

- ↵ Padgett DK. Qualitative and Mixed Methods in Public Health . SAGE Publications 2011. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=LcYgAQAAQBAJ

- Scharp KM ,

- Korstjens I

- Barnett-Page E ,

- ↵ Guest G, Namey EE, Mitchell ML. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Field Manual for Applied Research . SAGE 2013. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=-3rmWYKtloC

- Sainsbury P ,

- Emerson RM ,

- Saunders B ,

- Kingstone T ,

- Hennink MM ,

- Kaiser BN ,

- Hennink M ,

- O’Connor C ,

- ↵ Yen RW, Schubbe D, Walling L, et al. Patient engagement in the What Matters Most trial: experiences and future implications for research. Poster presented at International Shared Decision Making conference, Quebec City, Canada. July 2019.

- ↵ Got questions about Thematic Analysis? We have prepared some answers to common ones. https://www.thematicanalysis.net/faqs/ (accessed 9 Nov 2022).

- ↵ Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic Analysis. SAGE Publications. 2022. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/thematic-analysis/book248481 .

- Kalpokas N ,

- Radivojevic I

- Campbell KA ,

- Durepos P ,

- ↵ Understanding Thematic Analysis. https://www.thematicanalysis.net/understanding-ta/ .

- Saunders CH ,

- Stevens G ,

- CONFIDENT Study Long-Term Care Partners

- MacQueen K ,

- Vaismoradi M ,

- Turunen H ,

- Schott SL ,

- Berkowitz J ,

- Carpenter-Song EA ,

- Goldwag JL ,

- Durand MA ,

- Goldwag J ,

- Saunders C ,

- Mishra MK ,

- Rodriguez HP ,

- Shortell SM ,

- Verdinelli S ,

- Scagnoli NI

- Campbell C ,

- Sparkes AC ,

- McGannon KR

- Sandelowski M ,

- Connelly LM ,

- O’Malley AJ ,

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.21(12); 2021 Dec

General-purpose thematic analysis: a useful qualitative method for anaesthesia research

1 Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, School of Medicine, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

2 Department of Anaesthesia, Auckland City Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand

Learning objectives

By reading this article, you should be able to:

- • Explain when to use thematic analysis.

- • Describe the steps in thematic analysis of interview data.

- • Critique the quality of a study that uses the method of thematic analysis.

- • Thematic analysis is a popular method for systematically analysing qualitative data, such as interview and focus group transcripts.

- • It is one of a cluster of methods that focus on identifying patterns of meaning, or themes, across a data set.

- • It is relevant to many questions in perioperative medicine and a good starting point for those new to qualitative research.

- • Systematic approaches to thematically analysing data exist, with key components to demonstrate rigour, accountability, confirmability and reliability.

- • In one study, a useful six-step approach to analysing data is offered.

Anaesthesia research commonly uses quantitative methods, such as surveys, RCTs or observational studies. Such methods are often concerned with answering what questions and how many questions. Qualitative research is more concerned with why questions that enable us to understand social complexities. ‘Qualitative studies in the anaesthetic setting’, write Shelton and colleagues, ‘have been used to define excellence in anaesthesia, explore the reasons behind drug errors, investigate the acquisition of expertise and examine incentives for hand hygiene in the operating theatre’. 1

General-purpose thematic analysis (termed thematic analysis hereafter) is a qualitative research method commonly used with interview and focus group data to understand people's experiences, ideas and perceptions about a given topic. Thematic analysis is a good starting point for those new to qualitative research and is relevant to many questions in the perioperative context. It can be used to understand the experiences of healthcare professionals and patients and their families. Box 1 gives examples of questions amenable to thematic analysis in anaesthesia research.

Examples of questions amenable to thematic analysis.

- (i) How do operating theatre staff feel about speaking up with their concerns?

- (ii) What are trainee's conceptions of the balance between service and learning?

- (iii) What are patients' experiences of preoperative neurocognitive screening?

Alt-text: Box 1

Thematic analysis involves a process of assigning data to a number of codes, grouping codes into themes and then identifying patterns and interconnections between these themes. 2 Thematic analysis allows for a nuanced understanding of what people say and do within their particular social contexts. Of note, thematic analysis can be used with interviews and focus groups and other sources of data, such as documents or images.

Thematic analysis is not the same as content analysis. Content analysis involves counting the frequency with which words or phrases appear in data. Content analysis is a method used to code and categorise textual information systematically to determine trends, frequency and patterns of words used. 3 Conversely, thematic analysis focuses on the relative importance of ideas and how ideas connect and govern practices. Thematic analysis does not rely on frequency counts to indicate the importance of coded data. Content analysis can be coupled with thematic analysis, where both themes and frequencies of particular statements or words are reported.

Thematic analysis is a research method, not a methodology. A methodology is a method with a philosophical underpinning. If researchers report only on what they did, this is the method. If, in addition, they report on the philosophy that governed what they did, this is methodology. Common methodologies in qualitative research include phenomenology, grounded theory, hermeneutics, narrative enquiry and ethnography. 4 Each of these methodologies has associated methods for data analysis. Thematic analysis can be combined with many different qualitative methodologies.

There are also different types of thematic analysis, such as inductive (including general purpose), applied, deductive or semantic thematic analysis. Inductive analysis involves approaching the data with an open mind, inductively looking for patterns and themes and interpreting these for meaning. 2 , 4 Of note, researchers can never have a truly open mind on their topic of interest, so the process will be influenced by their particular perspectives, which need to be declared. In applied and deductive thematic analysis, the researcher will have a pre-existing framework (which may be informed by theory or philosophy) against which they will attempt to categorise the data. 4 , 5 , 6 For semantic thematic analysis, the data are coded on explicit content, and tend to be descriptive rather than interpretative. 6

In this review, we outline what thematic analysis entails and when to use it. We also list some markers to look for to appraise the quality of a published study.

Designing the data collection

Before embarking on qualitative research, as with quantitative research, it is important to seek ethical review of the proposed study. Ethical considerations include such issues as consent, data security and confidentiality, permission to use quotes, potential for identifying individuals or institutions, risk of psychological harm to participants with studies on sensitive issues (e.g. suicide or sexual harassment), power relationships between interviewer and interviewee or intrusion on other activities (such as teaching time or work commitments). 7

Qualitative research often involves asking people questions during interviews or focus groups. Merriam and Tisdell stated that, ‘The most common form of interview is the person-to-person encounter in which one person elicits information from the other’. 8 Information is elicited through careful and purposeful questioning and listening. 9 Research interviews in anaesthesia are generally purposeful conversations with a structure that allows the researcher to gather information about a participant's ideas, perceptions and experiences concerning a given topic.

A structured interview is when the researcher has already decided on a set of questions to ask. 9 If the researcher will ask a set of questions, but has flexibility to follow up responses with further questions, this is called a semi-structured interview. Semi-structured interviews are commonly used in research involving thematic analysis. The researcher can also use other forms of questioning, such as single-question interview. Semi-structured interviews are commonly used in anaesthesia, such as the studies from our own research group. 10 , 11 , 12

Interviews are usually recorded in audio form and then transcribed. For each interview or focus group, a single transcript is created. The transcripts become the written form of data and the collection of transcripts from the research participants becomes the data set.

Designing productive interview questions

The design of interview questions significantly shapes a participant's response. Interview questions should be designed using ‘sensitising concepts’ to encourage participants to share information that will increase a researcher's understanding of the participants' experiences, views, beliefs and behaviours. 13 ‘Sensitising concepts’ describe words in questions that bring the participants' attention to a concept of research interest. Examples of sensitising concepts include speaking up, teamwork and theoretical concepts (such as Kolb's experiential learning cycle or Foucauldian power theory in relation to trainee learning and operating theatre culture). 14 , 15 Specifically, the questions should be framed in such a way as to encourage participants to make sense of their own experience and in their own words. The researcher should try to minimise the influences of their own biases when they design questions. Using open-ended questions will increase the richness of data. Box 2 gives examples of question design.

How to design an interview question.

Alt-text: Box 2

Bias, positionality and reflexivity

Bias is an inclination or prejudice for or against someone or something, whereas positionality is a person's position in society or their stance towards someone or something. For example, Tanisha once had an inexperienced anaesthetist accidentally rupture one of her veins whilst they were siting an i.v. cannula in an emergency situation. Now, Tanisha has a bias against inexperienced anaesthetists. Tanisha's positionality —a medical anthropologist with no anaesthesia training, but working with many anaesthesia colleagues, including her director—may also inform that bias or the way that Tanisha interacts with anaesthetists. Reflexivity is a process whereby people/researchers proactively reflect on their biases and positionality. Biases shape positionality (i.e. the stance of the researcher in relation to the social, historical and political contexts of the study). In practical research terms, biases and positionality inform the way researchers design and undertake research, and the way they interpret data. It is important in qualitative research to both identify biases and positionality, and to take steps to minimise the impact of these on the research.

Some ways to minimise the influence of bias and positionality on findings include:

(i) Raise awareness amongst the research team of bias and positionality.

(ii) Design research/interview questions that minimise potential for these to distort which data are collected or how they are collected.

(iii) Researchers ask reflexive questions during data analysis, such as, ‘Is my bias about xxx informing my view of these data?’

(iv) Two or more researchers are involved in the analysis process.

(v) Data analysis member check (e.g. checking back with participants if the interpretation of their data is consistent with their experience and with what they said).

Before embarking on the study, researchers should consider their own experiences, knowledge and views; how this influences their own position in relation to the study question; and how this position could potentially introduce bias in how they collect and analyse the data. Taking time to reflect on the impact of the researchers' position is an important step towards being reflective and transparent throughout the research process. When writing up the study, researchers should include statements on bias and positionality. In quantitative research, we aim to eliminate bias. In qualitative research, we acknowledge that bias is inevitable (and sometimes even unconscious), and we take steps to make it explicit and to minimise its effect on study design and data interpretation.

Sampling and saturation

Qualitative research typically uses systematic, non-probability sampling. Unlike quantitative research, the goal of sampling is not to randomly select a representative sample from a population. Instead, researchers identify and select individuals or groups relevant to the research question. Commonly used sampling techniques in anaesthesia qualitative research are homogeneous (group) sampling and maximum variation sampling. In the former, researchers may be concerned with the experiences of participants from a distinct group or who share a certain characteristic (e.g. female anaesthesia trainees), so they recruit selectively from within the group with this shared characteristic to gain a rich, in-depth understanding of their experiences. Conversely, the aim with maximum variation sampling is to recruit participants with diverse characteristics to obtain a broad understanding of the question being studied (e.g. members of different professional groups within operating theatre teams, who have diverse ages, gender and ethnicities).

As with quantitative research, the purpose of sampling is to recruit sufficient numbers of participants to enable identification of patterns or richness in what they say or do to understand or explain the phenomenon of interest, and where collecting more data is unlikely to change this understanding.

In qualitative research, data collection and analysis often occur concurrently. This is because data collection is an iterative process both in recruitment and in questioning. The researchers may identify that more data are needed from a particular demographic group or on a particular theme to reach data saturation, so the next participants may be selected from a particular demographic, or be asked slightly different questions or probes to draw out that theme. Sample size is considered adequate when little or no new information emerges from interviews or focus groups; this is generally termed ‘data saturation’, although some qualitative researchers use the term ‘data sufficiency’. This could also be explained in terms of data reliability (i.e. the researcher is satisfied that collecting more data will not substantially change the results). Data saturation typically occurs with between 12 and 17 participants in a relatively homogeneous sampling, but larger numbers may be required, where the interviewees are from distinct groups or cultures. 16 , 17

Data management

For data sets that involve 10 or more transcripts or lengthy interviews (e.g. 90 min or more), researchers often use software to help them collate and manage the data. The most commonly used qualitative software packages are QSR NVivo, Atlas and Dedoose. 18 , 19 , 20 Many researchers use Microsoft Excel instead, or for small data sets the analysis can be done by hand, with pen, paper and scissors (i.e. researchers cut up printed transcripts and reorder the information according to code and theme). 21 NVivo and Atlas are simply repositories, in which you can input the transcripts and, using your coding scheme, sort the text into codes. They facilitate the task of analysis, rather than doing the analysis for you. Some advantages over coding by hand are that text can be allocated to more than one code, and you can easily identify the source of the segment of text you have coded.

Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis is ‘the classification and interpretation of linguistic (or visual) material to make statements about implicit and explicit dimensions and structures of meaning-making in the material and what is represented in it’. 22

Several social scientists have described this analytical process in depth. 2 , 6 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 For inductive studies, we recommend researchers follow Braun and Clarke's practical six-phase approach to thematic analysis. 26 The phases are (i) familiarising the researcher with the data, (ii) generating initial codes, (iii) searching for themes, (iv) reviewing themes, (v) defining and naming themes and (vi) producing the report. These six phases are described next.

Phase 1: familiarising the researcher with the data

In this step, the researchers read the transcripts to become familiar with them and take notes on potential recurring ideas or potential themes. They share and discuss their ideas and, in conjunction with any sensitising concepts, they start thinking about possible codes or themes.

Phase 2: generating initial codes

The first step in Phase 2 is ‘assigning some sort of short-hand designation to various aspects of your data so that you can easily retrieve specific pieces of the data’. 2 The designation might be a word or a short phrase that summarises or captures the essence of a particular piece of text. Coding makes it easier to summarise and compare, which is important because qualitative research is primarily about synthesis and comparison of data. 2 , 25 As the researcher reads through the data, they assign codes. If they are coding a transcript, they might highlight some words, for example, and attach to them a single word that summarises their meaning.

Researchers undertaking thematic analysis should iteratively develop a ‘coding scheme’, which is essentially a list of the codes they create as they read the data, and definitions for each code. 25 , 26 Code definitions are important, as they help the researcher make decisions on whether to assign this code or another one to a segment of data. In Table 1 , we have provided an example of text data in Column 1. TJ analysed these data. To do so, she asked, ‘What are these data about? How does it answer the research question? What is the essence of this statement?’ She underlined keywords and created codes and definitions (Columns 2 and 3). Then, TJ searched the remaining data to see if any more data met each code definition, and if so, coded that (see Table 1 ). As demonstrated in Table 1 , data can be coded to multiple codes.

Table 1

How to code qualitative data: an example

| Research question To what extent do you think the surgical safety checklist (SSC) has changed teamwork culture in New Zealand operating theatres? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Data (The following quotes are excerpts from written responses to the above question that the authors CD and JW independently wrote, and TJ coded) | Potential code | Code definition |

| ‘In New Zealand, we have spent a lot of time trying to build whole of with the SSC through a change in the way it is delivered and by introducing local auditors who observe SSC delivery and score it against a marking scale. I think this has had a big effect on the way the SSC is delivered’. (JW) ‘We changed it so it was to lead different parts of the checklist, and got rid of the paper. This really helped’. (JW) ‘SSC has significantly by encouraging all disciplines of the operating theatre team to speak up and of safety in the operating theatre’. (CD) | Team responsibility | Participant describes processes or behaviour that demonstrates the SSC promotes teamwork or is managed by the team (rather than by one person). This includes behavioural change. |

| ‘It started out being a paper checklist that a nurse was tasked with signing off to certify that the SCC had been done. We changed it so it was , and got rid of the paper. This really helped’. (JW) | Embedding the checklist | Participant describes processes that have made use of the SSC routine. |

| ‘I think that the SSC, along with our own approach to implementing it in New Zealand, and possibly , such as NetworkZ and OWR, is changing the culture in New Zealand operating theatres. I think it's a that's influencing the culture in the operating theatres to be more team oriented, more inclusive and less hierarchical’. (JW) | Other influences on cultural change | Participant describes influences other than the SSC on teamwork. |

| ‘SSC has significantly improved teamwork culture by encouraging all disciplines of the operating theatre team to and take ownership of safety in the operating theatre’. (CD) ‘In particular, nursing staff say that because of the in the SSC and because they are , they feel more part of the team’. (JW) ‘The overall management of the patient also feels more like teamwork as from each discipline are so that one aspect of a patient care is from another’. (CD) | Communication | Participant describes how communication (as an element of teamwork) is influenced by SSC |

In thematic analysis of interview data, we recommend that code definitions begin with something objective, such as ‘participant describes’. This keeps the researcher's focus on what participants said rather than what the researcher thought or said.

There is no set rule for how many codes to create. 25 However, in our experience, effective manageable coding schemes tend to have between 15 and 50 codes. The coding scheme is iterative. This means that the coding scheme is developed over time, with new codes being created as more data are coded. For example, after a close reading of the first transcript, the researcher might create, say, 10 codes that convey the key points. Then, the researcher reads and codes the next transcript and may, for instance, create additional four codes. As additional transcripts are read and coded, more codes may be created. Not all codes are relevant to all transcripts. The researcher will notice patterns as they code more transcripts. Some codes may be too broad and will need to be refined into two or three smaller codes (and vice versa ). Once the coding scheme is deemed complete and all transcripts have been coded, the researcher should go back to the beginning and recode the first few transcripts to ensure coding rigour.

The second step in Phase 2, once the coding is complete, is to collate all the data relevant to each of these codes.

Phase 3: searching for themes

In this phase, the researchers look across the codes to identify connections between them, with the intention of collating the codes into possible themes. Once these possible themes have been identified, all the data relevant to each possible theme are pulled together under that theme.

Phase 4: reviewing the themes

After the initial collation of the data into themes, the researchers undertake a rigorous process of checking the integrity of these themes, through reading and re-reading their data. This process includes checking to see if the themes ‘fit’ in relation to the coded excerpts (i.e. Do all the data collected under that theme fit within that theme?). Next is checking if the themes fit in relation to the whole data set (i.e. Do the themes adequately reflect the data?) This step may result in the search for additional themes. As a final step in this phase, the researchers create a thematic ‘map’ of the analysis.

When viewed together, the themes should answer the research question and should summarise participant experiences, views or behaviours.

Phase 5: naming the themes

Once researchers have checked the themes and included any additional emerging themes they name the final set of themes identified. Each theme and any subthemes should be listed in turn.

Phase 6: producing the report