Spain’s Geography and Culture Essay

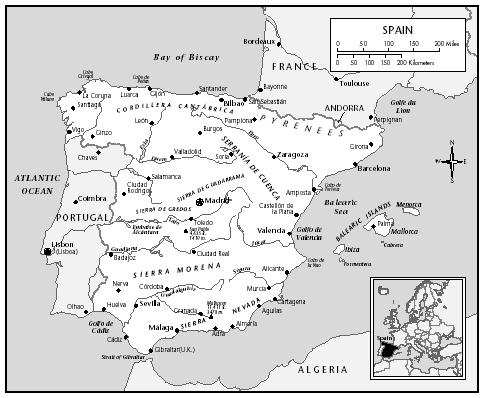

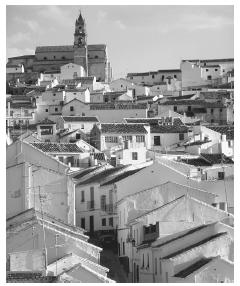

Spain, claiming over half a million acres on the Iberian Peninsula, fronts on the North Atlantic, the Bay of Biscay, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Balearic Sea. It borders the Pyrenees of France. and Portugal to the West. Morocco is its nearest Southern neighbor, across the Straits of Gibraltar (known in Classical times as the Pillars of Hercules) (n.a., Spain) .

Archeological evidence shows long habitation ranging from the pre-human (n.a., Spain History). Today’s populations represent a mix of Iron-Age Celtiberians, and subsequent conquerors; Romans, Visigoths, and Arabs, plus European allies/enemies (Gascoigne) . More recently, Spain has absorbed expatriates, ‘snow birds’ (Govan), and immigrants from less advantaged regions, including former New World colonies (Worden). Gypsies have always had a presence as well (n.a., Spain – The Gypsies).

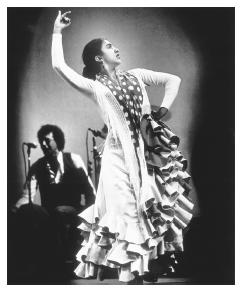

The rich legacy thereby bequeathed includes the Paleolithic cave art of Altamira to the north, Neolithic passage tombs at Los Millares to the South (n.a., Los Millares (3200-2200 B.C.)), Alhambra’s Moorish beauty (n.a., Alhambra), traditional bull-fighting, Flamenco music and dancing, the Prado’s treasures, medieval walled communities such as Toledo, and magnificent cathedrals and shrines everywhere. All are compelling.

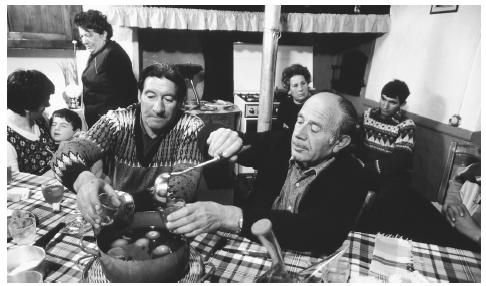

Daily life in Spain is idiosyncratic, although the siesta is disappearing (Deschenaux) . One wonders whether its demise will doom the nightly round of tapas bars; only feasible given a daytime rest. Gastronomy is unlikely to abate, given Madrid’s self-proclaimed ‘museum of ham’ (McLane). The distinctive cuisine of Spain includes the bounty of sea and land, plus colonial acquisitions such as potatoes and tomatoes.

When might we journey there?

Works Cited

Deschenaux, Joanne. Less Time for Lunch: the siesta in Spain is disappearing under the pressures of international business and big-city commuting, from HR Magazine. June 2008. Web.

Gascoigne, Bamber. History of Spain . From 2001, Ongoing. Web.

Govan, Fiona. “ British Expatriates March In Spain To Protest Against Chaotic Planning Laws. ” 2009. The Telegraph. Web.

McLane, Daisann. “ In Madrid There’s No Such Thing As Too Much Ham. ” 2000. New York Times. Web.

n.a. A Traveller’s Geography of Spain. 2010. Web.

—. Alhambra . 2010. Web.

—. Los Millares (3200-2200 B.C.). 2010. Web.

—. Spain . 27 December 2010. Central Intelligence Agency. Web.

—. “ Spain – The Gypsies. ” Country Studies. US Library Of Congress. Web.

—. “ Spain History .” 2010. Brittanica. Web.

Worden, Tom. “ Spain Sees Six-Fold Increase in Immigration Over Decade. ” 2010. The Guardian. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, July 18). Spain’s Geography and Culture. https://ivypanda.com/essays/spain/

"Spain’s Geography and Culture." IvyPanda , 18 July 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/spain/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Spain’s Geography and Culture'. 18 July.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Spain’s Geography and Culture." July 18, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/spain/.

1. IvyPanda . "Spain’s Geography and Culture." July 18, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/spain/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Spain’s Geography and Culture." July 18, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/spain/.

- Gastronomy of Tiramisu and Its Development

- Flamingo or Flamenco Dance

- Flamenco Music and Dance History: Spanish Carte-De-Visite Born in Andalusia

- Urban-Rural Variations in Health: Living in Greener Areas

- Physical, Human, and Economic Geography of Italians

- Germany; History, Geography, Legal and Politics

- GIS Project: Environmental Hazards in the USA

- Monsoons in South Asia

- The Culture Of Spain

- Historically, Spain's culture has been heavily influenced by religion, but this influence is slowly losing its prevalence.

- Spanish literature is credited with the creation of the picaresque genre, which follows the adventures of a rogue protagonist.

- Spaniards enjoy tapas as an afternoon snack, which is a selection of different foods served hot or cold at bars and restaurants.

- Though modern Western clothing is usually worn in Spain today, traditional items can still be seen at festivals or rural areas.

- Football (soccer) is very popular among Spaniards, and they have several high-performing teams.

Spain has a diverse culture, shaped by thousands of years of occupation by different empires. The ancient Greeks, Romans, Moors, Celts, Carthaginians and Phoenicians who settled in the country all left their mark on the cultural heritage of the country. Religion (and Christianity in particular) is also an important factor in shaping the traditions and customs in Spain.

7. Social Beliefs And Customs

Social beliefs and customs practiced in Spain are influenced by the local religion and traditions. Spaniards are known for being courteous and will shake hands when they meet and when departing. When interacting with the elderly they show respect by using titles such as don for men and doña for women. Married women wear wedding rings on their right hands as opposed to the left hand.

The family, be it the immediate relations or the extended family, is very important to Spaniards. Though it can be a conservative culture in some ways, it has also spearheaded its share of progress, such as becoming one of the earlier countries in legalizing same-sex marriage.

6. Religion, Festivals, And Holidays

Christianity is the dominant religion in Spain with the vast majority of Spaniards identifying themselves as Catholic. About 70% belong to the Catholic religion, while 26% of the population identifies as atheists. However, despite the historical prevalence of the Roman Catholic Church in Spain, the denomination has experienced a steady decline both in followers as well as clergy with the number of nuns seeing a drop in recent years. Lately, about 58% of Roman Catholics say they rarely attend mass.

Islam is the second-largest religion in Spain with about 800,000 citizens identifying as Muslims. The rise of Islam in the country is attributed to the influx of immigrants from Morocco in the 1990s, many of whom are Muslim. Jewish people make up a minority of the population with about 1% of Spaniards practicing the Jewish religion, with the majority being found in Madrid and Barcelona. Other religions practiced in Spain include Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism, and Paganism.

Spaniards are known the world over for their love of celebrations and festivals. These festivals are locally known as “Fiestas” and include Las Fallas. Held in March in Valencia, Las Fallas is arguably the largest celebration in Spain and features parades, fireworks, dancing, and ceremonial burning. Another top festival is the Carnival of Cadiz, held annually 40 days before Easter. Spain also has several national holidays which are observed all over the country and include the Day of Epiphany held on January 6th, Labor Day on May 1st, and the Constitution Day, observed on December 8th and marking the anniversary of the approval of their constitution.

5. Music And Dance

Spain has a vibrant music and dance scene with a wide array of genres ranging from traditional, classical music to modern genres. The music and dance are widely influenced by the cultural diversity of the country with different regions having distinct music styles. The region of Andalusia is known for the flamenco music and dance which incorporates the traditional seguidilla style. Other popular genres from the region include Sephardic and copla genres. Some notable musicians from Andalusia include Carlos Cano, Javier Ruibal, Joaquin Sabina and Luis Delgado.

The Aragon region is known as the birthplace of Jota music which is popular all over the country and features the use of tambourines, guitarro (a small traditional guitar), castanets, and the bandurria. The stick-dance, as well as the dulzaina dance, originated from Aragon. In the Canary Islands, a variation of Jota music known as Isa is common and is widely influenced by Cuban music.

Catalonia is known as the home of the Rumba Catalana, a type of rumba music created by the Catalan Romani with Rock Catalana being the popular music genre among young people from the region. In Valencia, Jota music is popular among residents who are also popular for performing bandes, local brass bands.

4. Literature And Arts

Literature in Spain has a rich history going back hundreds of years. One of the most popular literary works in Spain is La Celestina , a 1499 book written by Fernando de Rojas which is considered by many people as the best example of Spanish literature in history. A popular literary genre of Spanish literature is the picaresque novel whose origin is traced back to a 16th-century novel entitled Lazarillo de Tormes. The picaresque genre is where readers can follow the adventures of a rogue protagonist, and the most significant example of a Spanishpicaresque novel still commonly read today is Don Quixote.

Spain also has a reputable art scene with accomplished artists such as Salvador Dalí, Antoni Tapies, Juan Gris, and Joan Miro being known around the world. However, the most famous Spanish artist is Pablo Picasso, whose catalogue of works includes sculptures, paintings, ceramics, and drawings. The best locations to sample Spanish art at its finest are through its museums which include the Prado Museum, the Reina Sofia National Museum, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum.

Spanish cuisine is primarily drawn from Andalusian, Jewish and Roman traditions and closely resembles Mediterranean cuisine. Common characteristics of Spanish cuisine include the use of olive oil with Spain being one of the largest producers of olives, the use of onions and garlic and the partaking of wine during meals. Most meals prepared in Spain have potatoes, beans, pepper, and tomatoes as key ingredients. Some popular Spanish dishes include Escabeche and the Merienda. A common snack enjoyed all over Spain is the tapas which is an assortment of foods served either cold or hot in restaurants and bars. Spain is also home to many world-class chefs who include Sergi Cola, Ilan Hall, Penelope Casas and Karlos Arguinano, among others.

2. Clothing

The clothes worn in Spain feature both traditional as well as modern influences. Young Spaniards, particularly from urban centers, sport western-styled clothing such as jeans and sundresses. However, there are various articles of clothing from traditional Spanish culture that can still be seen and include the Zamarra, a long coat made of sheepskin; the Barretina, a traditional male hat popular in Catalonia; the Traje de Flamenca, a long dress worn by Andalusian women; and the Sombrero cordobés, a wide-brimmed hat commonly worn in Andalusia.

Football (known in the United States and Canada as soccer) is the most popular sport in Spain with the local football league known as the La Liga being dubbed “the best football competition in the world.” The La Liga features world-famous football teams such as Real Madrid and Barcelona, with global superstars like Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi playing for Spanish football clubs.

The Spanish national football team also has many world-class players and boasts of winning the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Tennis is another popular sport in Spain, with the country winning the Davis Cup five times. The country has also produced record-breaking tennis players led by Rafael Nadal, who became a tennis Olympic Gold medalist in the 2008 Summer Olympics.

More in Society

Understanding Stoicism and Its Philosophy for a Better Life

Countries With Zero Income Tax For Digital Nomads

The World's 10 Most Overcrowded Prison Systems

Manichaeism: The Religion that Went Extinct

The Philosophical Approach to Skepticism

How Philsophy Can Help With Your Life

3 Interesting Philosophical Questions About Time

What Is The Antinatalism Movement?

855-997-4652 Login Try a Free Class

A Brief Introduction to Spanish Culture, Traditions, and Beliefs

Spanish culture has contributed powerfully to the evolution of the Spanish language. The customs and identity of Spain stand out for several reasons. Particularly, Spanish traditions are unique and have influenced the culture of Latin American countries.

Still, some Spanish traditions are only possible to admire and experience if you take a trip to Spain. The breathtaking architecture, delicious food, the kind and warm people, and the astonishing celebrations are all worth honoring.

Pack your bags and join me for an insightful Introduction to Spanish culture, traditions, and beliefs!

Facts About Spanish Culture and Language

Spain has played a crucial role in world history. Firstly, Spain is the birthplace of the second most spoken language around the world. Secondly, it is home to fascinating Spanish culture and traditions.

Although the majority of the population speaks Spanish or Castellano, they speak other native languages there. Spanish is the second tongue of people who speak Basque, Catalan, Valencian, and Galician.

75% of Spain’s population speaks Castilian, 16% speak Catalan, and the remaining 9% speak the other tongues.

Learn More: How Many Languages Are Spoken in Spain?

The variety of languages contributes to a diverse Spanish culture that draws the attention of millions of tourists from all corners of the world. Small and large cities are home to influential architecture, rich music, vivid celebrations, and delicious foods.

Discovering Spain’s charming traditions and culture is worth your while if you’re learning Spanish. It’s the perfect opportunity to understand the language’s origin and social context. It gives you an insight on how society and identity are formed in Spain.

This familiarity with Spanish traditions makes you contextualize, absorb vocabulary and idioms, and become more confident in your language skills.

Let’s explore the most prominent and interesting facts about Spanish culture!

Spanish Greetings

Greetings and introductions are a fundamental particularity of Spanish culture.

Acquaintances say “hi” to each other the first time with a handshake and keep it simple. If you’ve met the person a few times already, the handshake will be warmer and may come with a pat on the shoulder. More familiarity with a person comes with a hug or with a double kiss on the cheek.

The double kiss on the cheek is the signature of Spain, Latin America took this part of Spanish culture and made its own. In many Latin American Spanish-speaking countries, people greet each other with one kiss on the cheek.

Most people will introduce themselves using only their first names. Each person has typically two first names and one last name they use. Older adults are introduced with the prefixes Don and Doña (Mr. & Mrs), to show them more respect and formality.

Religion is an essential element of Spanish culture.

Almost every Spanish city has Catholic churches and Cathedrals. The predominant religion in Spain is Catholicism. The second largest religion of Spain is Islam due to recent arrivals of African and Middle Eastern refugees. There is also a large portion of Atheists and a small percentage of Jewish people.

Nevertheless, religious holidays and traditions are quite popular with all the majority of people in the region.

Las procesiones (processions) are a prominent tradition of Spain that dates back to the 16 century. They are organized marches similar to parades that are a manifestation of faith and commemoration of religious happenings.

Processions are such an important part of Spanish culture, the tradition was taken to Latin America and became highly popular in countries like Guatemala.

Learn more about Guatemalan processions .

Celebrations and Festivals

Spain’s rich history comes with prominent celebrations and traditions.

Semana Santa (Holy Week) is one of the largest celebrations. It’s known for having processions that commemorate the Passion of Christ.

El Día de Reyes Magos (Day of the Three Kings) is widely celebrated across the country and is a favorite holiday for children. They receive gifts and there’s colorful parades in the cities where they celebrate their long awaited arrival.

Spanish “fiestas” (festivals) are large celebrations and carnivals devoted to a specific Saint or City. These fiestas have traditional foods, fireworks, dancing, handmade decorations, parades, concerts, and theater.

Other traditions like the running of the bulls of San Fermín in Pamplona, and the tomato fights of la Tomatina are experiences that draw millions of people and tourists to celebrate Spanish culture.

Read this insightful article about the largest Spanish fiesta , The Pyrotechnic Celebration of Las Fallas de Valencia .

Traditional Clothing and Fashion

Traditional styled clothing representative of Spanish culture is possible to admire in toreros (bullfighters), Flamenco dancers, and during festivities.

Some traditional pieces worth highlighting are:

- El traje corto (short suit): short jackets, combined with a white shirt, and high-waisted trousers. It’s usually worn by men with a Spanish sombrero (hat).

- La mantilla (veil): a long lace or silk veil that covers women’s head and shoulders. It was once a requirement to wear it before entering a church.

- La peineta (comb) : a tortoise-shell comb worn by women to secure the mantilla in their hair.

Spain is known for having a thriving fashion industry. The best designers and fashion brands of the world have a presence in Spain’s fashion events.

High-end designers like Cristóbal Balenciaga, Paco Rabanne, Manolo Blahnik, and Agatha Ruiz de la Prada are Spanish.

Spanish Culture and Arts

Spain is home to ingenious representatives of art and architecture. Well-known artists like Pablo Picasso, Francisco Goya, Salvador Dalí, and Joan Miró are Spanish.

The country is home to beloved museums of classical and contemporary art that pay homage to Spanish culture, traditions, and history.

Get inspired with this empowering list of 12 contemporary Spanish Female Artists that are redefining Spain’s art scene.

Barcelona, Spain’s most popular tourist destination, was the home of pioneer architect, Antoni Gaudí. He played a key role in the design of whimsical and complex architectural masterpieces in the Catalan city such as La Sagrada Familia and Parc Güell .

Discover Everything You Need to Know About Spanish Architecture in this informative blog post.

Spanish culture is very-well represented in literature. As the original representative of the Spanish language, the country harbours literary treasures that date back hundreds of years. Don Quixote is considered the best example of Spanish literature and language. The novel by author Miguel de Cervantes is over 400 years old.

Dive deep into the History of Don Quixote and Miguel de Cervantes in this fascinating blog post.

Spanish Music and Dance

Spanish culture is known for having well-known musical melodies and rhythms. Spain has produced incredibly talented songwriters and artists like Plácido Domingo, Enrique and Julio Iglesias, Paco de Lucía, Alejandro Sanz, and Rosalía.

Spanish music genres vary according to region. Flamenco , Rumba Catalana , and Bolero are accompanied by string musical instruments and powerful dance. Modern and classical artists often mix Flamenco and other traditional Spanish music with modern beats.

Roman and Celtic influence is evident in the varied styles of Spanish music and dancing. Flamenco is a signature dance often associated with Spain’s image.

Here’s a list of other popular Spanish dances:

- Sardana from Catalonia

- Muiñeira from Galicia

- Zambra from Andalusia

- Jota from Valencia

- Sevillana from Seville

Did you know Flamenco and Sardana are considered Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity? Learn what makes them special in this interesting article about Spanish Dances .

El fútbol (soccer) is the highest-grossing sport in Spain.

Spain’s official soccer team won the 2010 FIFA World Cup. La Liga Española (Spanish league) has some of the best performing teams in the world. Soccer clubs like Barcelona and Real Madrid, have the best names and superstars. Literally, the whole country gets paralized when these two teams face each other in El Clásico.

The country is also known for other groundbreaking athletes and champions. Tennis player Rafael Nadal and Formula 1 champion Fernando Alonso, set high standards for their competitors around the world.

What’s more, soccer and tennis aren’t the only sports the Spanish excel on. You’ll find that several types of sports like basketball, water polo, and surfing; are enjoyed throughout Spain.

Start a conversation about sports with this practical Guide to Spanish Sports Vocabulary.

Traditional Food

Food is a strong foundation of Spanish culture. The blend of Arab, Roman, Jewish, and Mediterranean cuisine uses top ingredients and flavors.

Spain produces large quantities of high-quality olive oil and wine. Predominant ingredients of Spanish gastronomy include garlic, tomato, pepper, potatoes, beans, and curated meats.

Spanish people enjoy a style of appetizer and snack known as tapas . Las tapas are usually a mix of small preparations like cold cuts, cheeses, croquetas (croquettes), calamares (squid), and more.

Savory food and flavors also make Spain the home of world-class chefs, elite cooking schools, and top-rated Michelin Star restaurants.

Here’s a list of representative dishes of Spanish culture and traditions:

- Fideuá – a seafood paella styled plate with noodles instead of rice

- Jamón – curated ham from the Iberian Peninsula.

- Fabada – a type of bean stew

- Patatas bravas – deep fried potatoes with spicy sauce

- Gazpacho – cold tomato soup

- Churros – fried dough pastries you can dip in hot chocolate

Pick up useful Spanish vocabulary in this appetizing blog post about The Origin and History of the Spanish Paella.

Curiosities About Spanish Culture

La siesta (nap time) .

It is a short nap Spanish people take in the early afternoon. The tradition has expanded to the Philippines and Mexico. During siesta time the majority of businesses close.

To celebrate New Year, people in Spain eat a grape for each month of the year for good luck.

Superstitions

The Spanish are superstitious about the number 13. Also, some Spanish people believe a hat on your bed is a bad omen.

When a Spanish family moves to a new house they need to buy a new broom. They believe bringing an old broom is bad luck.

In Catalonia, children get gifts from a wooden log-looking character known as el Tío de Nadal.

In Spanish culture, you’re expected to bring a gift when you’re invited to someone’s house for dinner.

Semana Santa

Certain Spanish traditions evolved into their own Latin American version. Such is the case of Semana Santa.

Plan a Trip to Spain

Experience these traditions for yourself and plan a cultural trip to Spain. The stylish fashion, incredible architecture, delicious food, colorful rhythms, and richness of Spanish culture are guaranteed to mesmerize you.

A trip to Spain is an ideal opportunity for you to practice your Spanish. Coming up close to Spanish traditions and native speakers enables you to understand the origin of the language and its surrounding context.

Sign up for a free class with our certified teachers from Guatemala. They provide an excellent learning environment and support you in developing advanced fluency. Prepare for your trip to Spain with useful vocabulary and next-level Spanish abilities.

Do you love Hispanic culture? Check out our latest posts!

- Celebrating Culture and Joy: The Magic of Carnival in Spanish-Speaking Countries

- 15 Mouth-Watering National Dishes of Latin America

- Discovering The Mayan Languages

- The 10 Most Common Spanish Surnames in The U.S

- Everything About Mexican Christmas Traditions

- What Is the Hispanic Scholarship Fund? Is It Legit?

- A Spanish Guide to Thanksgiving Food Vocabulary

- How Did All Saints Day Celebrations Started?

- Recent Posts

- 29 Cool and Catchy Spanish Phrases To Use With Friends [+Audio] - January 8, 2023

- A Fun Kids’ Guide to Opposites in Spanish (Free Lesson and Activities) - December 29, 2022

- 10 Fun Spanish Folk Tales for Kids - December 10, 2022

Related Posts

3 key benefits to being bilingual in the workforce, food for thought: 6 spanish foods to learn about (and try), bilingualism: how the us compares to other countries, ahead of the pack: how becoming bilingual now can leap your child ahead of their peers, leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Countries and Their Cultures

- Culture of Spain

Culture Name

Alternative names.

Los españoles

Orientation

Identification. The name España is of uncertain origin; from it derived the Hispania of the roman Empire. Important regions within the modern nation are the Basque Country (País Vasco), the Catalan-Valencian-Balearic area, and Galicia—each of which has its own language and a strong regional identity. Others are Andalucía and the Canary Islands; Aragón; Asturias; Castile; Extremadura; León; Murcia; and Navarra, whose regional identities are strong but whose language, if in some places dialectic, is mutually intelligible with the official Castilian Spanish. The national territory is divided into fifty provinces, which date from 1833 and are grouped into seventeen autonomous regions, or comunidades autónomas.

Location and Geography. Spain occupies about 85 percent of the Iberian peninsula, with Portugal on its western border. Other entities in Iberia are the Principality of Andorra in the Pyrenees and Gibraltar, which is under British sovereignty and is located on the south coast. The Pyrenees range separates Spain from France. The Atlantic Ocean washes Spain's north coast, the far northwest corner adjacent to Portugal, and the far southwestern zone between the Portuguese border and the Strait of Gibraltar. Spain is separated from North Africa on the south by the Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean Sea, which also washes Spain's entire east coast. The Balearic Islands lie in the Mediterranean and the Canary Islands in the Atlantic, off the coast of Africa. Spain also holds two cities, Ceuta and Melilla, on the Mediterranean coast of Morocco.

Spain's perimeter is mountainous, the mountains generally rising from relatively narrow coastal plains. The country's interior, while transected by various mountain ranges, is high plateau, or meseta, generally divided into the northern and southern mesetas.

Such general geographic distinctions as north/ south, coastal/interior, mountain/lowland/plateau, and Mediterranean/Atlantic are overwhelmed by the variety of local geographies that exist within all of the larger natural and historical regions. Great local diversity flourishes on Spanish terrain and is part of Spain's essence. The people of hamlets, villages, towns, and cities—the basic political units of the Spanish population—and sometimes even neighborhoods ( barrios ) hold local identities that are rooted not only in differences of local geography and microclimate but also in perceived cultural differences made concrete in folklore and symbolic usages. Throughout rural Spain, despite the strength of localism, there is also a perception of shared culture in rural zones called comarcas. The comarca is a purely cultural and economic unit, without political or any other official identity. In what are known as market communities in other parts of the world, villages or towns in a Spanish comarca patronize the same markets and fairs, worship at the same regional shrines in times of shared need (such as drought), wear similar traditional dress, speak the language similarly, intermarry, and celebrate some of the same festivals at places commonly regarded as central or important.

The populations least likely to feel Spanish are Catalans and Basques, although these large, complex regional populations are by no means unanimous in their views. The Basque language is unrelated to any living language or known extinct ones; this fact is the principal touchstone of a Basque sense of separateness. Even though many other measures of difference can be questioned, Basque separatism, where it is endorsed, is fueled by the experience of political repression in the twentieth century in particular. There has never been an independent Basque state apart from Spain or France.

Cataluña has had greater autonomy in the past and had, at different times, as close ties with southwestern France as with Spain. The Catalan language, like Spanish, is a Romance language, lacking the mysterious distinction that Basque has. But other measures of difference, in addition to a separate language, distinguish Cataluña from the rest of Spain. Among these is Cataluña's deeply commercial and mercantile bent, which has underlain Catalan economic development and power in both past and present. Perhaps because of this power, Cataluña has suffered longer from periodic repression at the hands of the central Castilian state than has any other of modern Spain's regions; this underlies a separatist movement of note in contemporary Cataluña.

The state now known as Spanish has long been dominated by Castile, the region that covers much of the Spanish meseta and the marriage of whose future queen, Isabel, to Fernando of Aragón in 1469 brought about the consolidation of powers that underlay the development of modern Spain. This growing power was soon to be enhanced by the Crown's monopoly (vis-a-vis other regions and the rest of Europe) on all that accrued from Christopher Columbus's discovery of the New World, which occurred under Crown sponsorship.

Madrid, already at the time an ancient Castilian town, was selected as Spain's capital in 1561, replacing the court's former home, Valladolid. The motive of this move was Madrid's centrality: it lies at Spain's geographic center and thus embodies the central power of the Crown and gives the court geographic centrality in relation to its realm as a whole. At the plaza known as Puerta del Sol in the heart of Madrid stand not only Madrid's legendary symbol—a sculpted bear under a strawberry tree ( madroño )—but also a signpost pointing in all directions to various of Spain's provincial capitals, a further statement of Madrid's centrality. The Puerta del Sol is at kilometer zero for Spain's road system.

Demography. Spain's population of 39,852,651 in early 1999 represented a slight decline from levels earlier in the decade. The population had increased significantly in every previous decade of the twentieth century, rising from under nineteen million in 1900. Spain's declining birthrate, which in 1999 was the lowest in the world, has been the cause of official concern. The bulk of Spain's population is in the Castilian provinces (including Madrid), the Andalusian provinces, and the other, smaller regions of generalized Castilian culture and speech. The Catalan and Valencian provinces (including the major cities of Barcelona and Valencia), along with the Balearic Islands, account for about 30 percent of the population, Galicia for about 7 percent, and Basque Country for about 5 percent. These are not numbers of speakers of the minority languages, however, as the Catalan, Gallego, and Basque provinces all hold diverse populations and speech communities.

Linguistic Affiliation. Spain's national language is Spanish, or Castilian Spanish, a Romance language derived from the Latin implanted in Iberia following the conquest by Rome at the end of the third century B.C.E. Two of the minority languages of the nation—Gallego and Catalan—are also Romance languages, derived from Latin in their respective regions just as Castilian Spanish (hereafter "Spanish") was. These Romance languages supplanted earlier tribal ones which, except for Basque, have not survived. The Basque language was spoken in Spain prior to the colonization by Rome and has remained in use into the twenty-first century. It is, as noted earlier, unique among known languages.

Virtually everyone in the nation today speaks Spanish, most as a first but some as a second language. The regions with native non-Spanish languages are also internally the most linguistically diverse of Spain's regions. In them, people who do not speak Spanish even as a second language are predictably older and live in remote areas. Most adults with even modest schooling are trained in Spanish, especially as the official use of the Catalan and Basque languages has suffered repression by centrist interests as recently as Francisco Franco's régime (1939–1975), as well as in earlier periods. None of the regional languages has ever been in official use outside its home region and their speakers have used Spanish in national-level exchanges and in wide-scale commerce throughout modern times.

Under the democratic government that followed Franco's death in 1975, Gallego, Basque, and Catalan have come into official use in their respective regions and are therefore experiencing a renaissance at home as well as enhanced recognition in the rest of the nation. Proper names, place-names, and street names are no longer translated automatically into Spanish. The unique nature of Basque has always brought personal, family, and place-names into the general consciousness, but Gallego and Catalan words had been easily rendered in Spanish and their native versions left unannounced. This is no longer so. There is evidence now—as has long been the case in Cataluña—that speakers of the regional languages are increasing in number. In Cataluña, where Catalan is spoken by Catalans up and down the social structure and in urban and rural areas alike, immigrants and their children become Catalan speakers, Spanish even falling to second place among the young. In Basque Country, the easy use of Basque is increasing among Basques themselves as the language regains status in official use. The same is true in Galicia in circles whose language of choice might until recently have been Spanish. An important literary renaissance expectedly accompanies these developments.

In those parts of Spain in which Spanish is the only language, dialectical patterns can remain significant. As with monolingualism in Basque, Catalan, or Gallego, deeply dialectic speech varies with age, formal schooling, and remoteness from major population centers. However, in some regions—Asturias is one—there has been a revival of traditional language forms and these are a focus of local pride and historical consciousness. Asturias, which in pre-modern times covered a wider area of the Atlantic north than the modern province of Asturias, was a major seat of early Christian uprising against Islam, which was established in southern Spain in 711 C.E. Events in Asturian history are thus emblematic of the persistence and reemergence of the Christian Spanish nation; the heir to the Spanish throne bears the title of Prince of Asturias. The Asturian dialect belongs to the Old Leonese ( Antiguo Leonés ) dialect area; this dialect was spoken and written by the kings of the early Christian kingdoms of the north (Asturias, León, Castile) and is ancestral to modern Spanish. Thus the Asturian dialect, like the province itself, is emblematic of the birth of the modern nation.

Symbolism. Spain's different regions, or smaller entities within them, depict themselves richly through references to local legend and custom; classical references to places and their character; Christian heroic tales and events; and the regions' roles in Spain's complex history, especially during the eight-century presence of Islam. Examples already cited here are the association of Madrid with a site at which a bear and a strawberry tree were found together, of Asturias with tales of local Christian resistance early in the Islamic period, and of Basque country with a pre-Roman language and a defiant resistance to Rome. Many such images are stable in time; others less so as new touchstones of identity emerge.

Current symbolism at the national level respects the mosaic of more local depictions of identity and joins Spain's regions in a flag that bears the fleurs-de-lis of the Bourbon Crown and the arms or emblems of the several historical kingdoms that covered the present nation in its entirety. The colors, yellow and red, of what was to become the national flag were first adopted in 1785 for their high visibility at sea. The presence of an eagle, either double- or single-headed, has been historically variable. So has the legend (under the crowned columns that represent the pillars of Hercules) based on the older motto nec plus ultra ("nothing beyond") that now reads plus ultra in recognition of Spain's discovery of new lands. The presence of a crown symbol, of course, has been absent in republican periods. The national flag is thus quite recent—it has only been displayed on public buildings since 1908—and its iconography much manipulated, as is that on the coins of the realm. Many regional and local symbols have been more stable in time. This in itself suggests the depth of localism and regionalism and the seriousness of giving them due weight in symbolizing the nation as a whole. In some instances the iconography or language of monarchy and the use of the adjective "royal" ( real ) takes precedence over the term "national." The national anthem is called the Marcha real, or Royal March, and has no words; at least one attempt to attach words met with public apathy.

Some of the most compelling and widespread national symbols and events are those rooted in the religious calendar. The patron saint of Spain is Santiago, the Apostle Saint James the Greater, with his shrine at Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, the focus of medieval pilgrimages that connected Christian Spain to the rest of Christian Europe. The feast of Santiago on 25 July is a national holiday, as is the feast of the Immaculate Conception, 8 December, which is also Spain's Mother's Day. Other national holidays include Christmas, New Year's Day, Epiphany, and Easter. The feast of Saint Joseph, 19 March, is Father's Day. The ancient folk festival of Midsummer's Eve, 21 June, is conflated with the feast of Saint John (San Juan) on 24 June and is also the current king's name day. Our Columbus Day, 12 October, is the Día de Hispanidad, also a national holiday.

There are also secular figures that transcend place and have become iconic of Spain as a whole. The most important are the bull, from the complex of bullfighting traditions across Spain, and the figures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, from Miguel de Cervantes's novel of 1605. These share a place in Spaniards' consciousness along with the Holy Family, emblems of locality (including locally celebrated saints), and a deep sense of participation in a history that has set Spain apart from the rest of Europe.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Early unification of Spain's tribal groups occurred under Roman rule (circa 200 B.C.E. to circa 475 C.E. ) when the Latin ancestral language was implanted, eventually giving rise to all of the Iberian languages except Basque. Other aspects of administration, military and legal organization, and sundry cultural and social processes and institutions derived from the Roman presence. Christianity was introduced to Spain in Roman times, and the Christianization of the populace continued into the Visigothic period (475 to 711 C.E. ). Spain's major contacts were Mediterranean (Phoenician, Greek, Roman, and North African) until the entry of the Visigoths from across the Pyrenees. The Visigoths were the first foreign power to establish their centers in the northern rather than the southern half of the peninsula. Visigothic rule saw the implantation of new forms of local governance, new legal codes, and the Christianization of the peoples of Spain's mountainous north. A Jewish population was present in Spain from about 300 B.C.E. , before Roman colonization, and throughout Spain's subsequent history until the expulsion in 1492 of those Jews who did not choose to convert to Christianity.

The Visigoths fell to Muslim invasion from North Africa in 711 C.E. and subsequently took refuge in the far north, while the south came under Islamic rule, most notably from the caliphate established at the southern city of Córdoba and ruling from 969 until 1031. The presence of Islam inspired from the beginning a Christian insurgency from the northern refuge areas, and this built over the centuries. Much of the northern meseta was a frontier between Christian kingdoms and the caliphate—or smaller Muslim kingdoms ( taifas ) after the caliphate's fall. Christians pushed this frontier increasingly southward until their final victory over the last Islamic stronghold, Granada, in 1492. During this period, Christian power was continually consolidated with Castile at its center. Also in 1492, under the sponsorship of the Catholic Kings, Fernando and Isabel, Columbus encountered the New World. Thus began the formation of Spain's great overseas empire at exactly the time at which Christian Spain triumphed over Islam and expelled unconverted Muslims and Jews from Spanish soil.

Spain has been a committed Roman Catholic nation throughout modern times. This commitment has informed many of Spain's relations with other nations. Internally, while the populace is almost wholly Catholic, there has been much philosophical, social-class, and regional variance over time regarding the position of the church and clergy. These issues have joined other secular ones, some regarding succession to the Crown, to produce a dynamic national political history. Twice the monarchy has given way to a republic—the first from 1873 to 1875, the second from 1931 to 1936. The Second Republic was overthrown in 1936 by a military uprising. Following a bloody civil war, General Francisco Franco, in 1939, established a conservative, Catholic, and fascist dictatorship that lasted until his death in 1975. Franco regarded himself as a regent for a future king and selected the grandson of the last ruler (Alfonso XIII, who left Spain in 1931) as the king to succeed him. Franco died in 1975 and King Juan Carlos I then gained the helm of a constitutional monarchy, which took a democratic Spain into the twenty-first century.

National Identity. Spanish national sentiment and a sense of unity rest on shared experience and institutions and have been strengthened by Spain's relative separation from the rest of Europe by the forbidding barrier of the Pyrenees range. Processes promoting unification were begun under Rome and the Visigoths, and the Christianization of the populace was particularly important. Christian identity was strengthened in the centuries of confrontation with Islam and again with the Spaniards' establishment of Christianity in the New World. The events of 1492 brought senses of both a renewed and an emergent nation through the reestablishment of Christian hegemony on Spanish soil and the achievement of new power in the New World, which placed Spain in the avant garde of all Europe.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

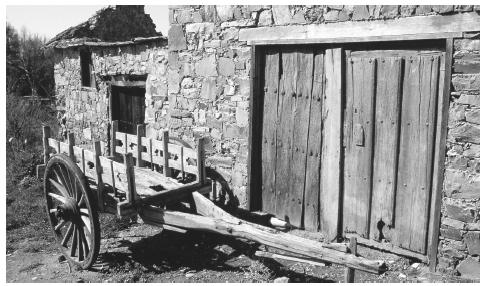

Spanish settlements are typically tightly clustered. The concentration of structures in space lends an urban quality even to small villages. The Spanish word pueblo, often narrowly translated as "village," actually refers equally to a populace, a people, or a populated place, either large or small, so a pueblo can be a village, a city, or a national populace. Size, once again, is secondary to the fact of a concentration of people. In most rural areas, dwellings, barns, storage houses, businesses, schoolhouses, town halls, and churches are close to one another, with fields, orchards, gardens, woods, meadows, and pastures lying outside the inhabited center. These latter are "the countryside" ( campo ), but the built center, no matter how large or small, is a distinct space: the urban center with a populace. Campo and pueblo are essentially separate kinds of space.

In some areas, human habitation is dispersed in the countryside; this is not the norm, and many Spaniards express pity for those who live isolated in the countryside. Dispersed settlement is most systematically associated with areas of mixed cultivation and cattle breeding, mostly in humid Spain along the Atlantic north coast. The latifundios (extensive estates) of the south also see some isolated complexes of dwelling and out-buildings ( cortijos ), and the Catalan masía is an isolated farmstead outside pueblo limits, but by and large, rural Spain is a place of multi-family pueblos.

Spain's major cities—Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Seville, and Zaragoza—and the many lesser cities, mostly provincial capitals, are major attractions for the rural populace. The qualities of urban life are sought after; in addition, nonagrarian work, market opportunities, and numerous important services are heavily concentrated in cities.

Dwelling types are varied, and what are sometimes called regional types are often in reality associated with local geographies or, within a single zone, with rustic versus more modern styles. Many parts of rural Spain display dwelling types that are rapidly becoming archaic and in which people and animals share space in ways that most Spaniards view with distaste. Most houses that meet with wider approval relegate animals to well-insulated stables within the dwelling structures, but with separate entries. Increasingly, however, animals are stalled entirely in outbuildings, and motor transport and the mechanization of agriculture have, of course, caused a significant decrease in the number and kinds of animals kept by rural families.

Houses themselves are usually sturdily built, often with meter-thick walls to insure stability, insulation, and privacy. Preferred materials are stone and adobe brick fortified by heavy timbers. Privacy is crucial because dwellings are closely clustered and often abut, even if their walls are structurally separate. Southern Spain, in particular, is home to houses built around off-street patios that may show mostly windowless walls to the public street. Urban apartment buildings throughout Spain may use the patio principle to create inner, off-street spaces for such domestic uses as hanging laundry. Building patios also constitute informal social space for exchange between neighbors.

Outside of dwellings and within a population center, most spaces are very public, particularly those areas that are used for public events. Village, town, and city streets, plazas, and open spaces are common property and subject to regulation by civic authority. The very public nature of outdoor space heightens the concern with the separation of domestic from public space and the maintenance of domestic privacy. Yet family members who share dwelling space may enjoy less privacy from one another than their American counterparts: most urban families, in particular, live in fairly cramped spaces in which the sharing of bedrooms and the multifunctional uses of common rooms are frequent.

Beyond the homes of rural or middle-class urban Spaniards, there are palaces, mansions, and monuments of both civil and sacred architecture that display some distinctions but much similarity to comparable structures in other parts of Europe. Spain also boasts such unique monuments of Islamic architecture as the Alhambra in Granada and the great Mosque of Córdoba; monuments of Roman building such as the aqueduct of Segovia and the tripartite arch at Medinaceli; and religious architecture of early Christian through Renaissance times. These—along with prehistoric art and sites—are important in the array of emblems of local and regional identities.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. The traditional Spanish diet is rooted in the products of an agrarian, pastoral, and horticultural society. Principal staples are bread (wheat is preferred); legumes (chickpeas, Old and New World beans, lentils); rice; garden vegetables; cured pork products; lamb and veal (and beef, in many regions only recently sought after); eggs; barnyard animals (chickens, rabbits, squabs); locally available wild herbs, game, fish, and shellfish; saltfish (especially cod and congereel); olives and olive oil; orchard fruits and nuts; grapes and wine made from grapes; milk of cows, sheep, and/or goats and cured milk products and dishes (cured cheeses and fresh curd); honey and Spanish-grown condiments (parsley, thyme, oregano, paprika, saffron, onions, garlic). Home production of honey is today mostly eclipsed by use of sugarcane and sugar-beet products, which have been commercialized in a few areas.

Most important among the garden vegetables are potatoes, peppers, tomatoes, carrots, cabbages and chard, green peas, asparagus, artichokes and vegetable thistle ( cardo ), zucchini squash, and eggplant. Most of these are ubiquitous but some, like artichokes and asparagus, are also highly commercialized, especially in conserve. Important orchard fruits besides olives are oranges and lemons, quinces, figs, cherries, peaches, apricots, plums, pears, apples, almonds, and walnuts. Of these, oranges, almonds, and quinces, in particular, are commercialized, as are olives and their oil. The most important vine fruits are grapes and melons, and in some regions there is caper cultivation. The heavily commercialized herbs are paprika and saffron, both of which are in heavy use in Spanish cookery.

The Spanish midday stew, of which every region has at least one version, is a brothy dish of legumes with potatoes, condimented with cured pork products and fresh meat(s) in small quantity, and with greens in season at the side or in the stew. This is known as a cocido or olla (or olla podrida ) and in some homes is eaten, in one or another version, every day. On days of abstinence from meat, cocido will be made with saltcod ( bacalao ) or salted congereel ( cóngrio ). In the eastern rice-producing areas around Valencia and Murcia, the midday meal may instead be one of the paella family of dishes (rice with vegetables, meat, poultry, and/or seafood). These rice dishes are eaten everywhere but in some areas are often reserved for Sundays.

The family meals, comida and cena, are important gathering times. Even in congested urban areas, most working people travel home to the comida and return to work afterwards. Commercial and office hours are designed around the comida hours: most businesses are closed by 1:00 or 2:00 P.M. and do not reopen for afternoon business until 4:00 or 5:00 P.M. at the earliest, depending upon the season—winter bringing earlier afternoon hours than summer. Banks and many offices have no afternoon hours. Food stores, butchers, and fishmongers may remain open longer in the mornings and not reopen until at least 6:00 (or not reopen at all) and then remain open until about 9:00 P.M. to accommodate late shoppers. Virtually all commerce is closed by the family supper hour of 10:00 P.M. , except of course taverns, bars, and restaurants.

Restaurant dining has become common in the urban middle, professional, and upper classes, where restaurants have made a few inroads on the home meals of some families; in general, however, family comida and cena hours are crucial aspects of family life throughout the nation. Restaurants in urban areas date only from the mid-nineteenth century: the Swiss restaurateur opened his eponymous Lhardy in Madrid in 1839. Other kinds of establishments—taverns, houses specializing in specific kinds of drinks (such as chocolate), and inns ( fondas ) offering meals to travelers are of course much older. But urban restaurants offering meals to those who could eat at home instead represented a new kind of social activity to those who could afford the price. Into the 1970s, Spaniards who ate in restaurants did so mostly in families and mostly to eat together, at leisure and in public, and not to try new foods. Menus were mostly of Spanish dishes from the same inventory home cooks also produced.

Spain's principal national dishes and foodstuffs are the various cocidos and the paella family of dishes, stuffed peppers, the tortilla española or Spanish omelette (a thick cake of eggs and sliced potatoes), and cured hams and sausages. A dish like gazpacho is most closely associated with Andalucía and is usually seasonal but today has national recognition, even though most of its varieties are little known outside their home zones. Tomato gazpacho is one of the Spanish dishes that has an international presence, as do paellas and mountain ( serrano ) hams.

Spain's contemporary version of the ancient refreshments barley-water (French orgeat ) or almond-water is made from the tuber chufa and is called horchata. This beverage is produced mostly for Spanish consumption. Another beverage, sherry wine, which is produced around the southern town of Jerez de la Frontera, has international fame. And it was Spaniards who first introduced Europeans to drinking chocolate. Chocolate parlors, like coffee-houses and wine cellars, are public gathering places that purvey and attract customers to drink specific beverages. In the apple country of the north, especially in Asturias, sidrerías, or cider lagers, are important gathering places. Their product, hard cider, is also bottled and exported to other regions and abroad. Wine, however, is the most common accompaniment to meals in most of the nation, and beer is drunk mostly before or between meals.

A number of desserts and sweets have a national presence, principally a group of milk desserts of the flan or caramel custard family. Cheese figures strongly as a dessert and is often served with quince paste. Almond or almond-paste confections made with honey and egg whites ( turrón, almond nougat or brittle) and marzipan ( mazapán ) are eaten everywhere during the Christmas season and are shipped across the nation and abroad from eastern almond-growing centers around Alicante (especially the town of Jijona).

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Eating and drinking together are Spaniards' principal ways of spending time together, either at everyday leisure moments, weekly on Sundays, or on special occasions. Special occasions include both general religious feast days such as Easter and Christmas and such family celebrations as birthdays, personal saints' days, baptisms, First Communions, and weddings. Many of these involve invited guests, and in small villages there may be at least token food offerings to the whole populace. Food is the principal currency of social exchange. Everywhere people with enough leisure form groups whose main purpose is the periodic enjoyment together of food and/ or drink. These sociable groups of friends are called cuadrillas, peñas, or by other terms, and their number is by no means confined to the well-known men's eating societies of Basque Country.

The contents of special meals vary. Some feature dishes from the daily inventory at their most elaborate and numerous, with the most select ingredients. Some respond to the Church's required abstentions (principally from meat) on particular days such as Christmas Eve and during Lent. Salt cod and eel are especially important in meatless dishes. Some purely secular festivals of rural families accompany the execution of major tasks: the sheepshearing, the pig slaughter, or the threshing of the grain harvest. In some regions, a funeral meal follows a burial; this is hosted by the family of the deceased for their kin and other invited guests. This (meatless) meal is in most places a thing of the past, and the Church has discouraged funeral banquets, but it was an important tradition in the north, in Basque, and in other regions.

Basic Economy. Spain has been a heavily agrarian, pastoral, and mercantile nation. As of the middle of the twentieth century the nation was principally rural. Today, industry is more highly developed, and Spain is a member of the European Economic Community and participates substantially in the global economy. Farmers' voluntary reorganization of the land base and the mechanization of agriculture (both accomplished with government assistance) have combined to modernize farming in much of the nation; these developments have in turn promoted migration from rural areas into Spain's cities, which grew significantly in the twentieth century. With the development of industry following World War II, cities offer industrial and other blue- and white-collar employment to the descendants of farm families.

The Spanish countryside as a whole has been largely self-sufficient. Local production varies greatly, even within regions, so regional and inter-regional markets are important vehicles of exchange, as has been a long tradition of interregional peddling by rural groups who came to specialize in purveying goods of different kinds away from their homes.

Land Tenure and Property. The chief factors that differentiate Spanish property and land tenure regimes are estate size and their partibility or impartibility.

Much of the southern half of Spain, roughly south of the River Tajo, is characterized by latifundios, or large estates, on which a single owner employs farm laborers who have little or no property of their own. Large estates date at least from Roman times and have given rise to a significant separation of social classes: one class consisting of the relatively leisured latifundio owners and the other class comprising the landless agrarian laborers who work for them, usually on short-term contracts, and live most of the time in the fairly large centers known as agro-towns. In the north, by contrast, properties are small ( minifundios ) and are lived on—usually in pueblo communities—and worked principally by the families of their owners or secondarily by families who live on and work the estates on long-term leases.

The north of Spain, dominated by minifundios, is crosscut by a difference in inheritance laws whereby in some areas estates are impartible and in others are divisible among heirs. Most of the nation is governed by Castilian law, which fosters the division of the bulk of an estate among all heirs, male and female, with a general (though variable) stress on equality of shares. There is a deep tradition in the northeast, however, whereby estates are passed undivided to a single heir (not everywhere or always necessarily a male or the firstborn), while other heirs receive only some settlement at marriage or have to remain single in order to stay on the familial property. This tradition characterizes the entire Pyrenean region, both Basque and Catalan, and adjacent zones of Cataluña, Navarra, and Aragón. The passage of estates undivided down the generations is a touchstone of cultural identity where it is practiced (just as estate division is deeply valued elsewhere), and as part of a separate and ancient legal system, the protection of impartibility has been central to these regions' contentions with Castile over the centuries. Spanish civil law recognizes stem-family succession in the regions where it is traditional through codified exceptions to the Castilian law followed in the rest of the nation. Nonetheless, the tradition of estate impartibility along the linguistic distinctions of the Basque and Catalan regions have long combined with other issues to make the political union of these two regions with the rest of Spain the most fragile seam in the national fabric.

Commercial Activities. Among Spain's traditional export products are olive oil, canned artichokes and asparagus, conserved fish (sardines, anchovies, tuna, saltcod), oranges (including the bitter or "Seville" oranges used in marmalade), wines (including sherry), paprika made from peppers in various regions, almonds, saffron, and cured pork products. Cured serrano ham and the paprika-and-garlic sausage called chorizo have particular renown in Europe.

Historically, Spain held a world monopoly on merino sheep and their wool; Spain's wool and textile production (including cotton) is still important, as is that of lumber, cork, and the age-old work of shipbuilding. There is coal mining in the north, especially in the region of Asturias, and metal and other mineral extraction in different regions. The Canary Islands' production of tobacco and bananas is important, as is that of esparto grass on the eastern meseta for the manufacture of traditional footgear and other items. Even though Spain no longer participates in Atlantic cod fishery, Spain's fisheries are nonetheless important for both national consumption and for export, and canneries are present in coastal areas. There is increasingly rapid transport of seafood to the nation's interior to satisfy Spaniards' high demand for quality fresh fish and shellfish.

Leather and leather goods have longstanding and continuing importance, as do furniture and paper manufacture. Several different regions supply both utilitarian and decorative ceramics and ceramic tiles, along with art ceramics; others supply traditional cloth handiwork, both lace and embroidery, while others are known for specific metal crafts—such as the knife manufacture associated with Albacete and the decorative damascene work on metal for which Toledo is famed.

Major Industries. Spain's heavy industry has developed since the end of the Civil War, with investments by Germany and Italy, and after the middle of the twentieth century with investments by the United States. The basis for these developments is old, however: iron mining and arms and munitions manufacture have been important for centuries, principally in the north. Spain's arms and munitions production is still important today, along with the manufacture of agricultural machinery, automobiles, and other kinds of equipment. Most industry is concentrated around major cities in the north and east—Bilbao, Barcelona, Valencia, Madrid, and Zaragoza. These industries have attracted migrants from the largely agrarian south, where there are sharp inequalities in land ownership not characteristic of the north, while other landless southerners have made systematic labor migrations into industrial areas of Europe—France, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland.

Trade. Spain is a member of the European Economic Community (Common Market) and has its heaviest trading relationship there, especially with Britain, and with the United States, Japan and the Ibero-American nations with which Spain also has deep historical ties and some trade relationships which date from the period of her New World empire. Among Spain's major exports are leather and textile goods; the commercialized foodstuffs named earlier; items of stone, ceramic, and tile; metals; and various kinds of manufactured equipment. Probably Spain's most significant dependence on outside sources is for crude oil, and energy costs are high for Spanish consumers.

Division of Labor. Once a predominantly agrarian and commercial nation, Spain was transformed during the twentieth century into a modern, industrial member of the global economic community. With land reform and mechanization, the agrarian sector has shrunk and the commercial, industrial, and service sectors of the economy have grown in size, significance, and global interconnection. Because the tourist industry is Spain's greatest and this rests on various forms of services, the service sector of the economy has seen particular growth since the 1950s.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. The apex of Spain's social pyramid is occupied by the royal family, followed by the titled nobility and aristocratic families. The Franco régime maintained a conservative appearance in this respect, even in the absence of a royal family (for which Franco substituted his own). But through history, Spaniards have been critical of their rulers. The anonymous medieval poet said of the soldier-hero El Cid, (Ruy Díaz de Vivar), "God, what a good vassal! If only he had a good lord!" and the populations of large territories in the north known in the Middle Ages as behetrías had the right to shift their collective allegiance from one lord to another if the first was found wanting.

In today's modern and democratic Spain, the circles around the royal family, titled nobility, and old aristocrats are ever widened by individuals who are endowed with social standing by virtue of achievements in business, public life, or cultural activity. Wealth, including new wealth, and family connections to contemporary forms of power count for a great deal, but so do older concepts of family eminence. Spain's middle class has burgeoned, its development having not suffered under Franco, and because the disdain for commercial activity that marked the ancien regime, and made nobles who kept their titles refrain from manual labor and most kinds of commerce, is long gone. Many heirs to noble titles choose not to pay the cost of claiming and maintaining them, but this does not deny them social esteem. Many titled nobles make their livings in middle-class professions without loss of social esteem. The bases on which Spaniards accord esteem have expanded enormously since the demise of the feudal regime in the mid-nineteenth century. Entrepreneurial and professional success are admired, as are new and old money, rags-to-riches success, and descent from and connection to eminent families.

Spain's class system is marked by modern Euro-American models of success; upward mobility is possible for most aspirants. Education through at least the lowest levels of university training are today a principal vehicle of mobility, and Spain's national system of public universities expanded greatly to accommodate demand in the last third of the twentieth century. After family eminence combined with some level of inherited wealth, education is increasingly the sine qua non of social advancement. The models of social success that are emulated are various, but all involve the trappings of material comfort and leisure as well as styles that are urbane and sometimes have global referents rather than simply Spanish ones. While Spain has a landed gentry—particularly in the southern latifundio regions where landlords are leisured employers rather than farmers themselves—the gentry itself values urbanity; increasingly these families have removed themselves to the urban settings of provincial or national capitals.

The wide base of the social pyramid is composed, as in western societies generally, of manual laborers, rural or urban workers in the lower echelons of the service sector, and petty tradesmen. The rural-urban difference is important here. Self-employed farming has always been an honored trade (others that do not involve food production were once seen as more dubious), but rusticity is not highly valued. Therefore, Spanish farmers, along with country tradesmen, share the disadvantage of having a rustic rather than an urbane image; urbanity must be gained with some effort (through education and emulative self-styling) if one is to move upward in society from rural beginnings.

At the margins of Spanish society are individuals and groups whose trades involve itinerancy, proximity to animals, and the lack of a fixed base in a pueblo community. Chief in this category are Spain's Roma or Gypsies (though some settle permanently) and other groups who are not necessarily of foreign origin but who shun the values Spaniards cherish and follow more of the model that contemporary Spaniards associate with Gypsies.

Symbols of Social Stratification. The outward signs of social differences are embodied in the degrees to which people can display their material worth through their homes (especially fashionable addresses) and furnishings, dress, jewelry and other possessions, fashionable forms of leisure, and the degrees to which their behavior reflects education, urbane sophistication, and travel. A Spanish family's ability to take a month's vacation is famously important as a sign of economic well-being and social status. Comfortable, even luxurious, modes of travel—not necessarily by one's own automobile—also enhance people's social images.

Political Life

Government. Spain is a parliamentary monarchy with a bicameral legislature. The current king, Juan Carlos I (the grandson of Alfonso XIII, who was displaced by the Second Republic) is the first monarch to reign following the Franco period. His succession (rather than that of his father, Juan de Borbón) was determined by Franco: Juan Carlos ascended to the throne in 1975 following Franco's death. In 1978 the constitution that would govern Spain in its new era took effect. While organizing a parliamentary democracy, it also holds the king inviolable at the pinnacle of Spain's distribution of powers. In 1981 the king helped to maintain the constitution in force in the face of an attempted right-wing coup; this promoted the continuance of orderly governance under the constitution despite other kinds of disruptions—separatist terrorism in the Basque and Catalan areas and a variety of political scandals involving government corruption. Spain has repeatedly seen orderly elections and changes of government and ruling party. The head of state, the prime minister, is a member of the majority party in a multiparty system. The years under the constitutional regime have brought Spain into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Community—and therefore, politically and economically closer to Europe—as well as into ever wider circles of global involvement.

Leadership and Political Officials. Leadership is a personal achievement but can be aided by family connections. In Spain's multiparty system, shifts in party governance tend to bring about changes in officialdom at deeper levels in official entities and agencies than occur in the United States; that is, party membership is a correlate of government employment at deeper levels and in a greater number of spheres in Spain than in the United States. Spain's political culture in the post-Franco period, however, is still developing.

The most local representative of national government is the secretario local, or civil recorder, in each municipality. Municipalities might cover one or more villages, depending on local geography, and there is a recent trend toward consolidation. Every locality as well has its municipal head of government, its alcalde (mayor), or—where a village has become a dependency of a larger seat in the municipality—an alcalde pedáneo (dependent mayor). Alcaldes are local residents who are elected locally while the secretarios are government appointees who have undergone training and passed civil service examinations. The secretario is the local recorder of property transactions and keeper of the population rolls that feed the nation's decennial census.

Social Problems and Control. Spain's justice system serves citizens from local levels, with justices of the peace and district courts, through the level of the nation's Supreme Court (and a separate Supreme Court for constitutional interpretations). The system is governed by civil and criminal law codes.

Every Spanish locality is served by one or another police force. Urban areas have municipal police forces, while rural areas and small pueblos are covered by the Guardia Civil, or Civil Guard. The Civil Guard, which is a national police corps, also handles the policing of highway and other transit systems and deals with national security, smuggling and customs, national boundary security, and terrorism.

Informal social controls are powerful forces in Spanish communities of all sizes. In tightly clustered villages, residents are always under their neighbors' observation, and potential criticism is a strong deterrent against culturally defined misconduct and the failure to adhere to expected standards. Many village communities rarely if ever activate the official systems of justice and law enforcement; gossip and censure within the community, and surveillance of all by all, are often sufficient. This is true even in urban neighborhoods (though not in entire large towns and cities) because Spaniards are socialized to observe and comment upon one another and to establish neighborly consciousness and relationships wherever they live. The anonymity of an American high-rise community, for example, is relatively foreign to Spain. But it is also true that larger Spanish populations resort to their police forces frequently and, today, are additionally plagued by the increased street crime and burglary that characterize modern times in much of the world.

Military Activity. Spain's armed forces—trained for land, sea, and air—are today engaged primarily in peacetime duties and internationally in such peacekeeping forces as those of the United Nations and in NATO actions.

Spain entered the twentieth century having lost its colonies in the New World and the Pacific in the Spanish-American War or, as it is known in Spain, the War of 1898. Troubles in Morocco and deep unrest at home engaged the military from 1909 into the 1920s. Spain did not enter World War I. The Civil War raged from 1936 to 1939. Exhausted and depleted, Spain did not enter World War II, although its Blue Division ( División Azul ) joined Hitler's campaign in Russia. The remainder of the twentieth century has seen years of recovery, rebuilding, the maintenance by Franco of a strong military presence at home, and—after his death—of the increasing internationalization of Spain's involvements and cooperation, military and otherwise, with the rest of western Europe.

Military officers have enjoyed high social status in Spain and, indeed, are usually drawn from the higher social classes, while the countryside and lower classes give their men to service when drafted. In many places, men who reach draft age together form recognized social groups in their hometowns. At the end of the twentieth century, although young men are still subject to the draft, military service is open to women as well, and the armed forces are becoming increasingly voluntary. Spain's final draft lottery was held in the year 2000.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Most of Spain's programs of social welfare, service, and development are in the hands of the state—including agencies of the regional governments—and of the Roman Catholic Church. Church and state are separate today, but Catholicism is the religion of the great majority. The Church itself—and Catholic agencies—have a weighty presence in organizing social welfare and in sponsoring hospitals, schools, and aid projects of all sorts. Local, national, and international secular agencies are active as well, but none covers the spectrum of activities covered by the Church and the religious orders. The state offers social security, extensive health care, and disability benefits to most Spaniards. Actual ministration to the sick and disadvantaged, however, often falls to Church agencies or institutions staffed by religious personnel.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

The importance of the Catholic Church in the spectrum of nongovernmental associations is great, both at parish levels and above. A hallmark of Spanish social organization in purely secular as well as in religious matters, however, is the formation of small groups on the basis of shared locality and/or other interests—sometimes in a guildlike manner—to pool resources, extend mutual aid, complete large tasks, or simply to share sociability. When based on shared locality, these groups are found from small villages to neighborhoods of large cities; nonlocal groups are based on common occupations or other shared experiences and interests. They offer intimacy beyond the family and join individuals within or between neighborhoods and localities. The spectrum of secular groups of this kind is extended—but by no means dominated—by such religious groups as saints' confraternities, other kinds of brotherhoods, and voluntary church-based associations dedicated to a variety of social as well as devotional ends. In addition, large-scale regional, national, and international organizations have an increasing importance in Spanish society in the field of nongovernmental associations, an area that was once more completely dominated by Church-related organizations.

Gender Roles and Statuses

The separation of the sexes in leisure establishes the pattern on which the division of labor is enacted among the elite. Where economic circumstances permit, men and women lead more separate lives than occurs among the peasantry, and then the traditional divisions of male from female tasks are less often breached. In public life, men more often pursue politics, and women maintain the family's religious observance and spend more time in child rearing and household management than men do. Where they have hired household help, the servants are likely women, and these are an old part of the nation's female work force, which is now expanding in new directions. The traditional ideal of a sexual division of labor is best achieved by the leisured classes, whom peasants emulate when they can. Domestic servants have always played a vital role in communicating élite models to the peasantry and working classes.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Spanish women under Castilian law inherit property equally with their brothers. They may also manage and dispose of it freely. This independence of control was traditionally relinquished to the husband upon marriage, but unmarried women or widows could wield the power of their properties independently. Today spouses are absolutely equal under the law.

Royal and noble women succeed to family titles if they have no brothers. In some areas of Spain, a woman may be heir to the family estate, but if she is not and instead marries an heir, she lives under the roof and rule of her husband and his parents. Nonetheless, women do not change their birth surnames at marriage in any part of Spain and can have public identities quite separate from those of their husbands.