Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 05 July 2022

A meta-review of psychological resilience during COVID-19

- Katie Seaborn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7812-9096 1 ,

- Kailyn Henderson 2 ,

- Jacek Gwizdka ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2273-3996 3 &

- Mark Chignell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8120-6905 2

npj Mental Health Research volume 1 , Article number: 5 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3836 Accesses

4 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

- Public health

- Quality of life

- Research data

- Scientific community

Psychological resilience has emerged as a key factor in mental health during the global COVID-19 pandemic. However, no work to date has synthesised findings across review work or assessed the reliability of findings based on review work quality, so as to inform public health policy. We thus conducted a meta-review on all types of review work from the start of the pandemic (January 2020) until the last search date (June 2021). Of an initial 281 papers, 30 were included for review characteristic reporting and 15 were of sufficient review quality for further inclusion in strategy analyses. High-level strategies were identified at the individual, community, organisational, and governmental levels. Several specific training and/or intervention programmes were also identified. However, the quality of findings was insufficient for drawing conclusions. A major gap between measuring the psychological resilience of populations and evaluating the effectiveness of strategies for those populations was revealed. More empirical work, especially randomised controlled trials with diverse populations and rigorous analyses, is strongly recommended for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Psycho-social factors associated with mental resilience in the Corona lockdown

Ilya M. Veer, Antje Riepenhausen, … Raffael Kalisch

Interrelations of resilience factors and their incremental impact for mental health: insights from network modeling using a prospective study across seven timepoints

Sarah K. Schäfer, Jessica Fritz, … Tanja Michael

COVIDiSTRESS diverse dataset on psychological and behavioural outcomes one year into the COVID-19 pandemic

Angélique M. Blackburn, Sara Vestergren & the COVIDiSTRESS II Consortium

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted many aspects of life at a global scale. Mental health and psychological well-being have subsequently emerged as key research foci in healthcare and public health during the pandemic 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 . Most countries have endorsed interventions with known or foreseen effects on psychological well-being, such as social distancing, physical isolation, and self-quarantine. Given what is already known about the relationship between mental health and psychological interventions 5 , this has further motivated questions on the assessment, management, and prevention of negative psychological outcomes 1 , 2 , 3 , 6 , 7 , 8 . Psychological resilience plays an essential role in times of crisis. As a behavioural characteristic, it can be framed as positive adaptability: the ability to “bounce back” when confronted with unusual and negative circumstances involving adversity, stress, and trauma 9 , 10 . Psychological resilience may be affected by socio-economic status 11 , cultural factors 12 , and other sources of influence. In pandemics, psychological resilience may dramatically affect outcomes. External offerings, such as social support systems, may reduce levels of depression 1 , while internal orientations related to psychological stress 2 , coping skills 2 , positive mood 7 , and positivity, especially “finding the good in the bad,” 9 are all facets of psychological resilience that subdue or prevent negative outcomes. The extent to which it is achieved, and how, may be a fundamental determinant of a population’s ability to combat mental health difficulties resulting from stressors related to the COVID-19 global pandemic.

A meta-review is a standard way of assessing the state of affairs. Meta-reviews, also termed umbrella reviews or overviews of reviews, are systematic reviews of extant review work that aim to achieve clarity and consensus on a specific research question or topic while considering factors such as review quality and bias 13 , 14 . Intended beneficiaries are decision-makers, the academic community, and the public. Meta-reviews synthesise systematic reviews and meta-analyses of primary studies, which typically represent the highest achievable level of evidence 13 . As such, assessing the quality of the body of review work is a key component of meta-reviews 13 . However, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a unique set of circumstances. Indeed, the ongoing, pressing need for answers has led to a large number of submitted manuscripts, as well as greater leniency in publishing criteria 15 . Emerging from this “paperdemic” are crucial questions regarding scientific integrity during COVID-19 15 . The collection of review work on psychological resilience may be subject to the same pressures of time and demand. Yet, as indicated by citation counts and media coverage, this work is being relied upon to inform our understanding of the situation and make public health decisions. A rigorous evaluation is necessary to reach consensus for healthcare governance and identify current inadequacies that must be accounted for in future editorial policies and publishing requirements.

This meta-review addresses an urgent need to both assess what is known about psychological resilience during COVID-19 and appraise the quality of research and review work being conducted on this topic. Our research objectives were: (RQ1) to summarise the nature and quality of this body of work and (RQ2) to derive a consensus on strategies implemented to evaluate, maintain, and cultivate psychological resilience throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. While our objective was to provide a reliable overview of the review work along with the means for building knowledge and taking action, we were largely limited by the state of the literature. In short, we cannot offer strong evidence for or against the strategies gathered across the corpus of survey work. Indeed, the severe limitations in this body of work are alarming and undermine the recommendations offered by specific reviews, however highly cited. We map out a series of psychological resilience factors, measures, and strategies gathered from these reviews that, while having potential validity, urgently need high quality empirical work on their efficacy within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Review sample and characteristics

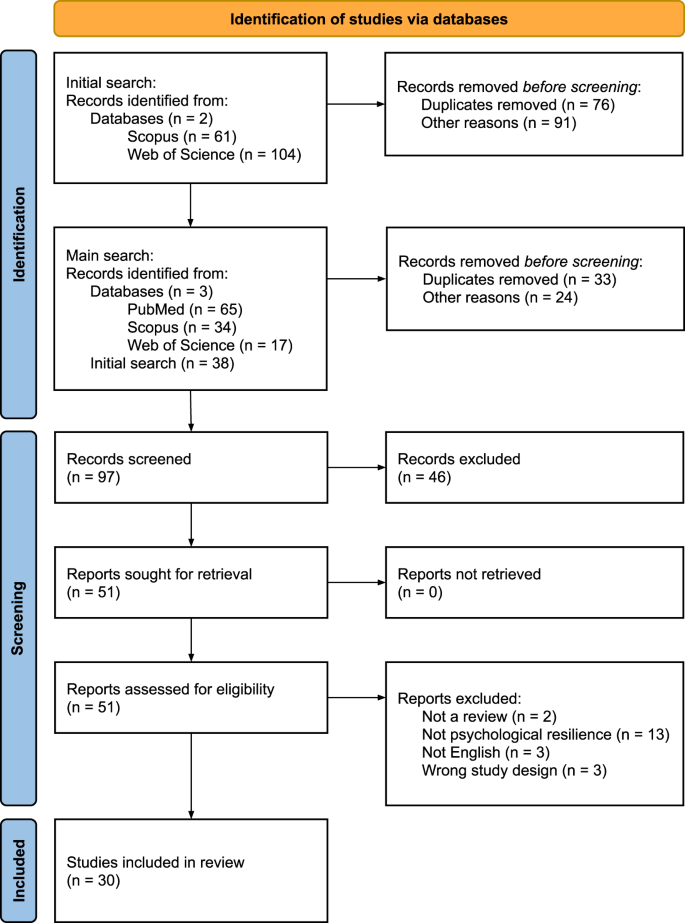

From an initial total of 281 reviews retrieved across three databases in two phases, 97 were screened and 30 were selected for analysis (Fig. 1 ). Excluded reviews and reasons for their exclusion are presented in Supplementary Table 4 .

PRISMA flow chart showing study inclusion and exclusion at the identification, screening, and included stages. The identification stage featured an initial search of two databases and a main search of three databases. The screening stage involved screening records, retrieving reports, and assessing their eligibility. Of these, 30 were included in the final stage.

General characteristics of the included reviews are presented in Supplementary Table 5 . Study characteristics were extracted from the 30 included reviews, all of which were published in 2020 or 2021. The review types included narrative (7), rapid (8), systematic (2), scoping (4), mini (1), and mixed methods (1). Only ten (33%) reviews used protocols: four pre-registered with PROSPERO, two with OSF (one in parallel), one with Cochrane Reviews, and three available but unregistered. Of these, one was available from the authors upon request, one was uploaded to an institutional website, and one explained “any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered)” 11 , 16 . Three reviews were highly cited (50 or more citations) but had no registered protocol and were deemed of low quality; three had registered protocols and were highly cited but of low quality; and five highly cited reviews, deemed of sufficient quality, had no registered protocol.

Participants were from the general population (all ages), as well as subset populations such as individuals working in healthcare (e.g., nurses, doctors, medical staff, social workers, etc.). Specific settings included hospitals, clinics, medical centres, and workplaces. Specific contexts mostly pertained to specific outbreak and pandemic situations, such as SARS, COVID-19, Ebola, H1N1, and MERS (Table 1 ). Twenty-five (83%) studies reported the number of databases searched, which ranged between 1 and 14 (M = 4.84, SD = 2.56, MD = 4, IQR = 3), with the earliest search being carried out on November 17, 2019, and the latest search on March 15, 2021. Twenty-three reviews (77%) reported the number of studies included, which ranged from 2 to 139 (M = 36.65, SD = 32.09, MD = 25, IQR = 31). These included qualitative and quantitative study designs: cross-sectional (surveys, observational), longitudinal, randomised controlled trials (RCTs), descriptive, cohort (prospective, retrospective), interviews, reviews, case-control, and mixed-methods. These studies were conducted in and across six continents: Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Europe, and Australia. Frequent countries of origin of the studies included China, UK, USA, Canada, India, Hong Kong, Italy, and Taiwan. Many of the outcomes reported pertained to the psychological and mental health impacts, e.g., anxiety, stress, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), insomnia, of COVID-19, and risk factors for these impacts.

Risk of bias across reviews

Full details of the risk of bias assessments are presented in Table 2 . The mean SANRA scores for qualitative reviews was 0.74 (SD = 0.12) and the mean JBI score for all other reviews was 0.78 (SD = 0.21). Based on the cut-off of 0.8, 15 reviews were determined to be of sufficient quality to answer RQ2: psychological resilience strategies.

Measures of psychological resilience

Reviews provided 31 unique positive measures (Table 3 ) and 55 unique negative measures (Table 4 ) to assess individuals’ psychological resilience status. Most also covered risk (with respect to negative measures) and protective (with respect to positive measures) factors and status results. A total of 14 risk factors (Table 5 ) and 7 protective factors (Table 6 ) were identified. Half of the factors received a GRADE score of moderate (7/14 for risk factors and 3/7 for protective factors). Counterpoints were included where possible to highlight patterns in how factors were framed and indicate where gaps and possibilities exist.

Strategies for psychological resilience

A corpus of 19 high-level strategies were gathered (Table 7 ). Most (17/19 or 89%) could not be given a GRADE score due to insufficient evidence, and the two remaining received very low GRADE scores. A further 15 specific training and/or intervention programmes were identified. Most were only identified by one review. The programmes were: Psychological first aid (PFA) 17 , 18 , 19 , trauma risk management (TRiM) 17 , 18 , eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) 17 , 18 , cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) 18 , 20 , 21 , cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi) 18 mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) 21 , mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) 18 , occupation therapy (OT) 18 , Motivational Interviewing (MI) 20 , resilience and coping for the healthcare community (RCHC) 17 , anticipate, plan, and deter (APD) 17 , resilience at work (RAW) 17 , mindfulness training 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , hardiness training 21 , 22 , and crisis intervention 20 .

Almost none of the high-level strategies or specific programmes were evaluated for their effectiveness, within or outside of COVID-19. Moreover, only one review 24 focused on longitudinal work, while also including and merging together non-longitudinal work, such as naturalistic studies. Indeed, 8 of the 15 reviews (53%) called for longitudinal research as future work. One exception was a significant effect of the number of protective measures and equipment provided within work contexts on reducing psychological distress, according to the reporting of Giorgi et al. 20 on 6 of 42 papers. However, no risk of bias or quality assessment was conducted, limiting our ability to draw conclusions on the strength or generalisability of this strategy. The other exception was PFA. Pollock and colleagues 18 reported on a cluster-randomised study by Sijbrandij et al. 25 in which PFA was evaluated through a measure of burnout against a control (no intervention) at baseline, post-assessment, and follow-up stages with 408 participants. Results for completers and intention-to-treat groups indicated that there was no significant difference between groups or over time (95% CI). However, Pollock et al. noted risk of bias due to insufficient reporting, use of single items from a multi-item measure, and weak statistical analyses. Subsequently, we are not confident that there is sufficient evidence to draw conclusions about the efficacy of PFA. Indeed, we are not confident to recommend any of these high-level strategies or specific programmes, based on the review work so far.

Review work, especially systematic surveys, are considered the gold standard of evidence 13 . A wide range of professionals rely on review syntheses to make decisions on policy, practice, and research 26 . In global pandemics, psychological health and resilience are key variables that impact the ability of individuals and populations to recover and carry on. As such, recognition of resilience factors, methods of measuring resilience, and strategies to build and maintain resilience are essential. Unfortunately, this meta-review indicates that the present body of review work is severely limited, leaving us unable to confidently summarise or synthesise knowledge for public health. The implications are grave, particularly given that some of this research has already been used to inform decision-making and justify subsequent research. Additionally, it is difficult to advocate for or against measures and guidance in terms of clinical practice.

Assessing review quality is one of the main objectives of meta-review work 13 . The quality of this corpus was very low overall. Furthermore, a large portion of the work could not be assessed due to insufficiency in reporting and weaknesses in review methodology. The intended main target—strategies for psychological resilience—was particularly impacted. The narrative reviews were notably biased, characterised by opinions and claims without literature backing or reasoning. The quality of most of these reviews was subsequently too low to meet the standard for inclusion in our analyses. The other types of reviews were also insufficient to draw conclusions. Meta-analyses were not possible due to the sheer variety of measures (i.e., heterogeneity) and disconnect between these measures and the strategies reported. Indeed, we found a preponderance of instruments for a relatively short list of measures, with little reasoning behind this diversity. Moreover, most of the strategies reported were mere suggestions rather than options grounded in evidence-based sources. The two strategies that did have some evidentiary support—namely, providing PPE and training or intervention programmes—were nevertheless deemed by ourselves and the original reviewers as very low in quality. In short, we have found clear and widespread evidence that the review work on psychological resilience has been subject to the COVID-19 “paperdemic” phenomenon 15 . This leaves us unable to provide recommendations with confidence. Yet, some of these reviews, notably Preti et al. 27 ( c = 269), Etkind et al. 28 ( c = 171), and Heath et al. 29 ( c = 128), have received a lot of attention via citations, news outlets, and social media. In light of their quality, reliance on these papers to inform policy and practice is inadvisable. At best, these reviews signal a keen interest and urgent need for rigorous, empirical work on matters pertaining to psychological resilience.

Synthesising the nature of the review work revealed several biases and gaps. Most of the reviews were focused on frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) and women. Yet, the literature points to several other groups for whom psychological resilience and/or well-being may be integral within the context of COVID-19, including older adults 30 , people with disabilities 31 , LGBTQ + folk 32 , people with pre-existing mental health conditions 7 , 30 , racialized groups and ethnic minorities 33 , 34 , and people living in low-income and/or isolated areas 35 . A certain level of bias in focus is a natural and common feature of many areas of study 36 . Yet, it cannot be allowed to influence review work, once discovered. We encourage researchers and practitioners to consider work focused on these overlooked populations. Additionally, the way that psychological resilience has been approached needs reconsideration. We found a negative bias in factors and measures. Most measures defined resilience as the absence of mental health problems rather than the presence of fortitude, flexibility, growth, and so on. We also found a concerted focus on risk, rather than protective, factors. While identifying who may be more susceptible and in what contexts is important, it is equally important to determine what characteristics and conditions are favourable to higher rates of psychological resilience. Mental health and well-being stressors may be unavoidable in a pandemic, which this negative bias highlights. Yet, without knowledge of additive and protective factors, it is difficult to make suggestions for clinical practice. Our tables highlight these gaps and can be used to guide future research. Finally, the gap between psychological resilience measures and strategies needs to be addressed, with strategies assessed via these measures in longitudinal studies within the context of COVID-19. Clinical practice and public health would be well-served by a direct link between negative or positive outcomes and the various strategies offered. Without this work and the consensus that a review of it could offer, we cannot make recommendations with confidence.

Methodologically, there was some consistency in the limitations observed in the surveyed review work. Most reviews were not associated with a registered protocol, such as on PROSPERO or Covidence. This created undue repetition in the corpus. It is strongly encouraged that all review protocols be registered in advance; with a hot topic like COVID-19, it is likely that review work is already being undertaken. Additionally, most works included research conducted outside of the COVID-19 pandemic and did not distinguish which results were particular to COVID-19. As such, we cannot draw conclusions on whether there are any special features of the COVID-19 context relevant to psychological resilience. Future work should focus on research conducted during COVID-19 or should delineate between studies conducted during COVID-19 and other contexts, including other pandemics.

This meta-review is limited in a few ways. The heterogeneity in the corpus made it difficult to find and extract data for synthesis and comparison. For example, some reviews reported on sample size in terms of the number of people, while others reported on the number of hospitals or used another population metric. Additionally, finding a “one size fits all” tool for quality and risk of bias assessment proved challenging. This may be a matter of the topic (i.e., a feature of work on psychological resilience) or the breadth of review types included. As with most meta-reviews, included reviews sometimes reported on the same studies, and so certain characteristics that appear to be common across reviews may actually reflect multiple citations of the same study. This issue also limits the accuracy of estimating the number of studies (aggregated across the reviews) that were surveyed. While it is beyond the scope of the present work, this may be addressed by extracting the studies from all reviews, eliminating duplicates, and re-conducting the analyses for each review—a significant effort that may not yield findings equivalent in value to the time and labour required.

The original search was conducted in June 2021, and more reviews are likely to have been published since that time. A retrospective covering the “last waves” of the pandemic will be a necessary future complement to the present meta-review. In the meantime, we briefly comment on a few relevant papers that speak to the issue of longitudinal changes during the pandemic. Riehm et al. 37 noted that time as a factor of resilience is severely understudied. Their findings from over 6000 adults in the Understanding America Study showed that mental distress varied markedly by resilience level during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, with low-resilience adults reporting the largest increases in mental distress. Bäuerle et al 38 . evaluated the impact of the “CoPE It” e-mental health intervention designed to improve resilience to mental distress during the pandemic. However, while they found a significant net gain between baseline and post-intervention, they relied on data obtained at only two time points and did not use a control group. There remains an urgent need for longitudinal studies of the effectiveness of interventions to increase psychological resilience during pandemics. A recently published study protocol by Godara et al. 39 exemplifies the type of research that is needed in this area. The planned study on a mindfulness intervention would last ten weeks, involve 300 participants, include a control group, and cover a range of key outcomes, such as levels of stress, loneliness, depression and anxiety, resilience, prosocial behaviour, empathy, and compassion. This proposed study and others like it could provide the needed information on the effectiveness of interventions to improve psychological resilience that is currently lacking.

We conclude with a sober reflection on the state of affairs. As this meta-review has shown, there is insufficient high-quality evidence to inform policy and practice. The silver lining is that a way forward can be mapped through the gaps and weaknesses that characterise this body of work. We urgently recommend the following:

Systematic reviews that follow international standards for methodology (e.g., Cochrane, JBI) and register their protocol through PROSPERO or an equivalent independent body.

Empirical work that uses a common means of measuring positive and negative states and traits related to psychological resilience.

Empirical work that evaluates the proposed psychological resilience strategies, including training interventions and programmes, during COVID-19.

Empirical and review work that targets a range of population subsets beyond frontline HCWs in a broader range of geographical locations and cultural contexts.

Empirical work that involves experimental control, longitudinal designs, naturalistic settings, and other rigorous approaches.

We conducted a systematic meta-review of literature reviews on psychological resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines 40 with modifications for meta-reviews based on Aromataris et al. 13 . Our PRISMA checklist for the abstract is in Supplementary Table 1 and our PRISMA checklist for the article is in Supplementary Table 2 . We used the protocol available in Seaborn et al. 6 . This protocol was registered in advance of data collection with PROSPERO on February 17, 2021 under registration ID CRD42021235288.

Eligibility criteria

All types of reviews that summarised empirical work on psychological resilience in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic were included. We aimed to source only the highest quality of work available. As such, included reviews needed to be published in an academic or medical trade venue and peer reviewed as a basic criterion for quality. Publications from the start of the pandemic (January 2020) until the start of the review (June 2021) were included. Only reviews written in English were included, as this was the language known by all of the authors and the current international standard. Theory and opinion papers were not included, as they would not provide the type of summarised evidence sought for public health decision making. Inaccessible and unpublished literature reviews, including papers posted to archival websites and grey literature, were excluded because a minimum of quality could not be guaranteed.

Information sources, search strategy, and study selection

Three databases, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, were searched between January 16 and 19, 2021, with an update on June 9, 2021. Full search terms and queries can be found in Supplementary Table 3 . A1, A3, and A2 conducted the searches, saving the results to Zotero and removing duplicates there. The combined list was then uploaded to Covidence. A1, A4, and A2 independently screened the papers in two phases: first based on the titles, keywords, and abstracts, and then based on the full text. A list of reviews excluded at the full text stage is available in Supplementary Table 4 . A1 and A4 divided the work and A2 screened all papers. Conflicts were resolved by involving the other reviewer.

Data collection and extraction

A1, A3, and A2 independently extracted data into a Google Sheet. A1 and A3 extracted data for about 50% of the total papers each, and A2 extracted data from all papers. A4 was assigned to resolve conflicts between the sets of data extractions. Data extraction variables were decided based on an extension of PICOS 41 for meta-reviews 13 . These included: article title, authors, year of publication, objectives, type of review, participant demographics (population subset, setting), number of databases searched, date ranges of database searches, publication date ranges of reviewed articles, number of studies, types of studies, country of origin of studies, study risk of bias/quality assessment tool used, protocol registration, citation count via Google Scholar, outcomes reported, method/s of analysis, measures of psychological resilience, their instruments, whether they were tested in COVID-19, how they were assessed (i.e., statistically), CIs, measures used to evaluate strategies, their instruments, whether they were tested in COVID-19, how they were assessed (i.e., statistically), CIs, thematic frameworks, and major finding.

Risk of bias and confidence assessments

Risk of bias and quality assessments were independently conducted by A1, A4, and A2 using a Google Form and Sheet. A1 and A4 were each responsible for about 50% of the papers, and A2 assessed all papers. We used the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) 42 for qualitative reviews and the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Synthesis 13 for the rest. In contrast to the protocol, we did not use the AMSTAR-2 because there were too few reviews that met the characteristics required for that tool. Sums were averaged across the reviewers. Cut-offs were determined after evaluating and comparing the reviews in a weighted fashion; for both, the cut-off was set at 0.8. Only the data of reviews that met the standard of quality were used to answer RQ2. Confidence in the quality of evidence was assessed by A1 and A2 using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system 43 .

Data analysis

The planned meta-synthesis could not be conducted due to the nature of the reviews captured. As such, measures of effect, variability (i.e., heterogeneity), and other inferential statistics could not be generated. Instead, a combination of descriptive statistics and thematic analyses were generated to identify meaningful patterns across the data 44 , 45 . A3 was responsible for the descriptives. A1, A4, and A2 conducted the thematic analyses. High-level themes were inductively derived as a means of “seeing across” the corpus of review work, while most sub-themes were semantically derived, using the words found within the reviews. All thematic analyses involved a standard, rigorous process of familiarisation with the data, initial coding by one reviewer, generation of initial themes by that reviewer, independent application of those themes by two reviewers, discussion and re-review until conflicts were resolved or themes discarded, and finalisation of themes by the first reviewer. A4 was the first reviewer for the measures data. A1 was the first reviewer for the strategies and risk/protective factors data. A2 was the second reviewer in all cases. We used Google Sheets for all analyses.

Data availability

Most of the data is included in this paper and/or the Supplementary Information. All other data can be made available by the authors upon request.

Giebel, C. et al. COVID-19-related social support service closures and mental well-being in older adults and those affected by dementia: A UK longitudinal survey. BMJ Open 11 , e045889 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Robillard, R. et al. Social, financial and psychological stress during an emerging pandemic: Observations from a population survey in the acute phase of COVID-19. BMJ Open 10 , e043805 (2020).

Ranieri, V. et al. COVID-19 welbeing study: A protocol examining perceived coercion and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic by means of an online survey, asynchronous virtual focus groups, and individual interviews. BMJ Open 11 , e043418 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

da Silva Júnior, F. J. G. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of young people and adults: A systematic review protocol of observational studies. BMJ Open 10 , e039426 (2020).

van Agteren, J. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 631–652 (2021).

Seaborn, K., Chignell, M. & Gwizdka, J. Psychological resilience during COVID-19: A meta-review protocol. BMJ Open 11 , e051417 (2021).

Jia, R. et al. Mental health in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional analyses from a community cohort study. BMJ Open 10 , e040620 (2020).

Feroz, A. S. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and well-being of communities: an exploratory qualitative study protocol. BMJ Open 10 , e041641 (2020).

Tugade, M. M. & Fredrickson, B. L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 86 , 320–333 (2004).

American Psychological Association. Building your resilience. https://www.apa.org . https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience (2012).

Wu, X., Li, X., Lu, Y. & Hout, M. Two tales of one city: Unequal vulnerability and resilience to COVID-19 by socioeconomic status in Wuhan, China. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 72 , 100584 (2021).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Braun-Lewensohn, O., Abu-Kaf, S. & Kalagy, T. Hope and resilience during a pandemic among three cultural groups in Israel: The second wave of Covid-19. Front. Psychol . 12 , 637349 (2021).

Aromataris, E. et al. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evid. Implement. 13 , 132–140 (2015).

Google Scholar

Higgins, J. (eds) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (John Wiley & Sons, 2019).

Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. COVID-19 research: Pandemic versus “paperdemic”, integrity, values and risks of the “speed science”. Forensic Sci. Res. 5 , 174–187 (2020).

Rieckert, A. et al. How can we build and maintain the resilience of our health care professionals during COVID-19? recommendations based on a scoping review. BMJ Open 11 , e043718 (2021).

Hooper, J. J., Saulsman, L., Hall, T. & Waters, F. Addressing the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: Learning from a systematic review of early interventions for frontline responders. BMJ Open 11 , e044134 (2021).

Pollock, A. et al. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: a mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11 , CD013779 (2020).

PubMed Google Scholar

Kunzler, A. M. et al. Mental health and psychosocial support strategies in highly contagious emerging disease outbreaks of substantial public concern: A systematic scoping review. PLoS One 16 , e0244748 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Giorgi, G. et al. COVID-19-related mental health effects in the workplace: A narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17 , 7857 (2020).

Labrague, L. J. Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of quantitative studies. J. Nurs. Manag. 29 , 1893–1905 (2021).

Batra, K., Singh, T. P., Sharma, M., Batra, R. & Schvaneveldt, N. Investigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 among healthcare workers: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17 , 9096 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Muller, A. E. et al. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: A rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res . 293 , 113441 (2020).

Prati, G. & Mancini, A. D. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol. Med. 51 , 201–211 (2021).

Sijbrandij, M. et al. The effect of psychological first aid training on knowledge and understanding about psychosocial support principles: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17 , 484 (2020).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pettman, T. L. et al. Communicating with decision-makers through evidence reviews. J. Public Health 33 , 630–633 (2011).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Preti, E. et al. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review of the evidence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 22 , 43 (2020).

Etkind, S. N. et al. The role and response of palliative care and hospice services in epidemics and pandemics: A rapid review to inform practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 60 , e31–e40 (2020).

Heath, C., Sommerfield, A. & von Ungern-Sternberg, B. S. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia 75 , 1364–1371 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Steptoe, A. & Gessa, G. D. Mental health and social interactions of older people with physical disabilities in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Public Health 6 , e365–e373 (2021).

Armitage, R. & Nellums, L. B. The COVID-19 response must be disability inclusive. Lancet Public Health 5 , e257 (2020).

Salerno, J. P., Williams, N. D. & Gattamorta, K. A. LGBTQ populations: Psychologically vulnerable communities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 12 , S239–S242 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Poole, L., Ramasawmy, M. & Banerjee, A. Digital first during the COVID-19 pandemic: Does ethnicity matter? Lancet Public Health 6 , e628–e630 (2021).

Patel, P., Hiam, L., Sowemimo, A., Devakumar, D. & McKee, M. Ethnicity and covid-19. BMJ 369 , m2282 (2020).

Patel, J. A. et al. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: The forgotten vulnerable. Public Health 183 , 110–111 (2020).

Whiting, P. et al. Sources of variation and bias in studies of diagnostic accuracy. Ann. Intern. Med. 140 , 189–202 (2004).

Riehm, K. E. et al. Association between psychological resilience and changes in mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 282 , 381–385 (2021).

Bäuerle, A. et al. Mental health burden of the COVID-19 outbreak in Germany: Predictors of mental health impairment. J. Prim Care Community Health 11 , 2150132720953682 (2020).

Godara, M. et al. Investigating differential effects of socio-emotional and mindfulness-based online interventions on mental health, resilience, and social capacities during the COVID-19 pandemic: The study protocol. PLoS One 16 , e0256323 (2021).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372 , n71 (2021).

Tacconelli, E. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10 , 226 (2010).

Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S. & Mertens, S. SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 4 , 5 (2019).

Guyatt, G. H. et al. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336 , 924–926 (2008).

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M. & Namey, E. E. Applied Thematic Analysis (Sage, 2012).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 , 77–101 (2006).

De Kock, J. H. et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: Implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 21 , 104 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Varghese, A. et al. Decline in the mental health of nurses across the globe during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 11 , 05009 (2021).

Hughes, M. C., Liu, Y. & Baumbach, A. Impact of COVID-19 on the health and well-being of informal caregivers of people with dementia: A rapid systematic review. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 7 , 23337214211020164 (2021).

Gilan, D. et al. Psychomorbidity, resilience, and exacerbating and protective factors during the SARS-CoV-2-pandemic’a systematic literature review and results from the German COSMO-PANEL. Dtsch. Arzteblatt Int. 117 , 625–632 (2020).

Jans-Beken, L. A perspective on mature gratitude as a way of coping with COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 12 , 632911 (2021).

Blanc, J. et al. Addressing psychological resilience during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A rapid review. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 34 , 29–35 (2021).

Sterina, E., Hermida, A. P., Gerberi, D. J. & Lapid, M. I. Emotional resilience of older adults during COVID-19: A systematic review of studies of stress and well-being. Clin. Gerontol . https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2021.1928355 (2021).

De Brier, N., Stroobants, S., Vandekerckhove, P. & De Buck, E. Factors affecting mental health of health care workers during coronavirus disease outbreaks (SARS, MERS & COVID-19): a rapid systematic review. PLoS One 15 , e0244052 (2020).

Sirois, F. M. & Owens, J. Factors associated with psychological distress in health-care workers during an infectious disease outbreak: A rapid systematic review of the evidence. Front. Psychiatry 11 , 589545 (2020).

Chew, Q. H., Wei, K. C., Vasoo, S. & Sim, K. Psychological and coping responses of health care workers toward emerging infectious disease outbreaks: A rapid review and practical implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Psychiatry 81 , 20r13450 (2020).

Balcombe, L. & de Leo, D. Psychological screening and tracking of athletes and digital mental health solutions in a hybrid model of care: Mini review. JMIR Form. Res . 4 , e22755 (2020).

Berger, E., Jamshidi, N., Reupert, A., Jobson, L. & Miko, A. Review: The mental health implications for children and adolescents impacted by infectious outbreaks—a systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 26 , 157–166 (2021).

Ho, C. Y. et al. The impact of death and dying on the personhood of medical students: A systematic scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 20 , 516 (2020).

Seifert, G. et al. The relevance of complementary and integrative medicine in the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative review of the literature. Front. Med. 7 , 587749 (2020).

Schwartz, R., Sinskey, J. L., Anand, U. & Margolis, R. D. Addressing postpandemic clinician mental health: A narrative review and conceptual framework. Ann. Intern. Med. 173 , 981–988 (2020).

Wright, E. M., Carson, A. M. & Kriebs, J. Cultivating resilience among perinatal care providers during the covid-19 pandemic. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 35 , 105–109 (2021).

Davis, B. E., Lakin, L., Binns, C. C., Currie, K. M. & Rensel, M. R. Patient and provider insights into the impact of multiple sclerosis on mental health: A narrative review. Neurol. Ther . https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00240-9 (2021).

Kaur, T. & Som, R. R. The predictive role of resilience in psychological immunity: A theoretical review. Int. J. Curr. Res. Rev. 12 , 139–143 (2020).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Industrial Engineering and Economics, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo, Japan

Katie Seaborn

Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, The University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Kailyn Henderson & Mark Chignell

School of Information, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA

Jacek Gwizdka

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors had full access to the data and were responsible for the decision to submit this manuscript for publication. All authors accessed and verified the final data. All were involved in data collection and analysis. K.S., J.G., and M.C. were responsible for conceptualising the research. K.S. was responsible for methodology and project administration. K.S. and M.C. were responsible for supervision. K.S., K.H., and J.G. handled data curation. K.S., M.C., and K.H. were responsible for data screening and verification. K.S., J.G., and K.H. were responsible for data extraction. J.G. was responsible for descriptive analysis. K.S., M.C., and K.H. were responsible for qualitative analysis. K.S. wrote the first draft of the paper with input from the rest. K.H. and K.S. were responsible for data visualisation and the supplemental material. Each author wrote the part of the results section relevant to their data analysis.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Katie Seaborn .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

All authors declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Seaborn, K., Henderson, K., Gwizdka, J. et al. A meta-review of psychological resilience during COVID-19. npj Mental Health Res 1 , 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-022-00005-8

Download citation

Received : 25 January 2022

Accepted : 17 March 2022

Published : 05 July 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-022-00005-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Cross-sectional study of resilience, positivity and coping strategies as predictors of engagement-burnout in undergraduate students: implications for prevention and treatment in mental well-being.

- 1 School of Education and Psychology, University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain

- 2 School of Psychology, University of Almería, Almería, Spain

- 3 UCD School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- 4 Konrad Lorenz University Foundation, Bogota, Colombia

- 5 Stress Prevention Unit, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy

- 6 Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy

- 7 STEM Unit and Centre for Workplace Excellence, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia

In a population of young adults, this study analyzes possible linear relations of resilience and positivity to coping strategies and engagement-burnout. The aim was to establish a model with linear, associative, and predictive relations, to identify needs and make proposals for therapeutic intervention in different student profiles. A population of 1,126 undergraduate students with different student profiles gave their informed, written consent, and completed validated questionnaires (CD-RISC Scale; Positivity; Coping Strategies of Stress; Engagement, and Burnout). An ex post-facto design involved bivariate association analyses, multiple regression and structural predictions. The results offered evidence of associations and predictive relationships between resilience factors, positivity, coping strategies and engagement-burnout. The factors of resilience and positivity had significant differential associations (positive and negative) with factors of coping strategies. Their negative relationship to burnout factors, and positive relation to engagement factors, is especially important. Results of structural analysis showed an acceptable model of relationships between variables. We conclude with practical implications for therapeutic intervention: (1) the proactive factors of resilience reflect a perception of self-efficacy and the ability to change adaptively; (2) the reactive factors of resilience are usually associated with withstanding experiences of change, uncertainty or trauma.

Introduction

The problem of academic stress in the University context and the demands of therapeutic response in this context has had great relevance in recent times. Numerous recent investigations have analyzed mental health prevention strategies in young University students, in order to minimize the psychological effects of this situation ( 1 , 2 ). To do this, they have focused their interest on the role of resilience and well-being. An example of this is the Monographic, in which this research is inserted ( 3 ).

The analysis of resilience, as a psychological variable in the sphere of preventive and therapeutic intervention, is important from both the structural and functional points of view ( 4 – 6 ). The distinction between structural and functional analysis of resilience is not often reflected in the previous literature, despite the importance of this distinction. Structural analysis of resilience makes it possible to reach a precise understanding of the role of each behavioral component of the theoretical construct, in order to infer therapeutic adjustment strategies for each person ( 7 , 8 ). Questions that illustrate structural analysis could be: Do all components of resilience have the same functionality? Is it possible to identify certain components of resilience that have a proactive value and others that are more reactive in nature? In complementary fashion, Functional analysis contributes to a procedural view of the behaviors associated with each component of resilience, in relation to other variables ( 9 ). In this case, questions may refer to the most likely possible relationship between components of resilience and a given variable: What factors in resilience will be strongest in predicting the psychological variable positivity, or coping strategies? Positivity and coping strategies were selected as important behavioral factors that can help predict states of engagement vs. burnout, in the context of academic stress, just as previous research has suggested ( 10 , 11 ). From an understanding of these structural and functional relationships, preventive and therapeutic intervention strategies can be plausibly established. The present study, therefore, offers a new model of evidence of plausible predictive relationships between the proactive and reactive components of resilience, positivity, coping strategies and state of engagement-burnout.

Resilience and Mental Well-Being in Young Adults

Over the past 50 years, the psychological study of stress and resilience to adversity has been plentiful ( 12 ). With the influence of Positive Psychology, resilience has become a very popular topic in the field of psychopathology as well, where there is growing interest in positive adaptation in response to stress ( 13 ).

A recent meta-analysis by Grossman ( 14 ) has identified more than 10,000 articles that include the term resilience, relating it negatively to physical health complaints, and positively to overall well-being. Moreover, resilience has been positively associated with the experience of positive emotions and the use of adaptive coping strategies, that is, problem-focused coping ( 15 ). Most researchers agree on the general definition of resilience as the ability to withstand adversity or recover from stress and negative experiences ( 12 , 14 – 17 ). Refining this definition, it can further be said that resilience is also the ability to move forward and grow in response to difficulties and challenges, that is, to become stronger through adversity ( 18 ).

The role of resilience, whether in protecting against stress, or in generating well-being, has been analyzed from several perspectives ( 19 ). Research also reports its value in personal recovery after health accidents ( 20 ), as well as in prevention of psychopathological symptoms, especially when resilience is worked on clinically within a cognitive-behavioral methodology ( 21 ). Additionally, recent studies have shown a connection between resilience and well-being, and between resilience and mental health ( 22 ), mediated by the relationship between optimism and subjective well-being ( 23 , 24 ).

Resilience and Behavioral Positivity as Protective Factors Against Stress

Resilience, as a personal characteristic, has been considered in Positive Psychology to be a factor that protects against stress ( 25 ). There is broad agreement that it is a complex, multidimensional construct ( 26 ). There is also consensus that two important aspects must be present to speak of resilience: an experience of adversity and a subsequent positive adaptation ( 13 , 27 – 29 ). These two underlying aspects of resilient experience help us implicitly understand two types of resilient behavior: (1) reactive , bearing up under negative events, or the ability to withstand ( 30 ); recall as coined by Persius: “he conquers who endures”; and (2) proactive , or a reaction to events that actively seeks to restore well-being ( 31 , 32 ); “look for the silver lining of the cloud” alludes to this type of behavior.

This positive adaptation brings benefits in terms of skills (hidden skills that are discovered and appreciated), relationships (which are selected, strengthened and improved), and changes in priorities and life philosophy, both toward the present and future ( 33 ). Moreover, scholars agree that resilience is an ability that can be the object of learning. Previous research points to the ability to bounce back as a relatively common phenomenon that does not stem from extraordinary qualities but from “ordinary magic” ( 34 ). Consequently, resilience improves with life experiences ( 35 , 36 ). On the other hand, there is still much debate about its nature. There is no clear understanding or consensus in the scientific community about its structure or its components ( 14 , 15 ), about the mechanisms that are implicit in the construct, or whether the processes and products of resilence should be considered traits or states ( 27 , 37 – 41 ). Several recent studies have established the connection between resilience and mental health, through positivity ( 42 ). Yet to be established are the precise behavioral mechanisms by which resilience takes shape as behavior. The present study seeks to contribute toward this end.

Resilience and Coping Strategies

Resilience has been associated with coping strategies, which have been identified as emotional meta-strategies ( 43 , 44 ). Accordingly, resilience has been found to be associated with a positive predictor of self-regulation, learning approaches and coping strategies ( 45 – 47 ). A relationship has also been established with effective learning ( 48 ). The literature is clear in that resilience reflects successful management of stress events ( 49 ), moderating their negative effects, and promoting adaptation and psychological well-being ( 14 , 29 , 50 ).

Certain previous studies have established specific relationships between resilience and coping ( 39 , 47 ). Resilience and coping are often used interchangeably, although there is growing evidence to suggest that they are conceptually distinct constructs, though related ( 37 ). Flecher and Srkar ( 27 ) indicate that “Resilience influences how an event is appraised whereas coping refers to the strategies employed following the appraisal of a stressful encounter” (p. 16). The message that emerges from the literature, according to these authors, is that resilience consists of various factors that promote personal assets and protect the individual from the negative appraisal of stressors; recovery and coping, then, are conceived as conceptually different from resilience.

Recent studies have shown that resilience and coping strategies are associated with and linearly predict well-being ( 51 , 52 ), as well as different diseases and health problems ( 53 , 54 ). Taking this consistent relationship further, the present study aims to show the mediational role of coping strategies between resilience and the motivational states of engagement-burnout.

Resilience and the Emotional States of Engagement vs. Burnout

Resilience has appeared as a protective variable against stress, and a negative predictor (or protective) of burnout ( 55 ). In the sphere of employment, numerous studies have indicated a negative relationship between resilience and burnout ( 56 ), as well as a positive relationship with engagement ( 57 ). Other research studies have shown that emotional skills mediate in the states of engagement-burnout ( 58 ).

In the academic context, resilience has been considered as an attitudinal or meta-motivational variable, within the Competence for Studing, learning and Performance with Stress , a CSLS model of competence for managing academic stress [( 59 ); in review]. Given its high degree of relationship with self-regulatory behavior, it has been conceptualized as a meta-ability that can determine the motivational state of students, in situations of academic stress. Therefore, it is possible to assume that it is a positive predictor of the motivational state of engagement and a negative predictor of the motivational state of burnout in University students. Several studies have reported the negative mediational role of resilience with respect to a state of burnout, and a positive mediational role in engagement ( 60 , 61 ).

Aims and Hypotheses

Yet to be established, however, are the specific mechanisms of how each component of resilience acts on the two motivational states (engagement vs. burnout), through coping strategies. This is the aim of the present study. Linear relations between resilience, coping strategies and engagement-burnout were applied to infer needs and proposals for intervening in different profiles of students. Based on prior evidence, the following hypotheses were posed: (H1) resilience would be associated with the personal variable of positivity, acting as a positive predictor; (H2) both variables, jointly, would be associated with and would be significantly positive predictors of problem-focused strategies and the motivational state of engagement; (H3) both would also be negative predictors of emotion-focused strategies and the motivational state of burnout.

Participants

An initial 1,126 undergraduate students participated in this study. The response rate was 95%, for a total of 1,069 students. This sample corresponds to a population of inference of 1,376 University students, with 99% total confidence and 0.1 percentage. The sample contained students enrolled in Psychology, Primary Education, and Educational Psychology; 85.5% were women and 14.5% were men. The age range was 19–25, and mean age was 21.33 years (sd = 2,73). Two Spanish public universities with similar characteristics were represented; 324 students attended one University and the remainder attended the other. The study design was incidental and non-randomized. The Guidance Department at each University invited teacher participation, and the teachers invited their own students to participate, on an anonymous, voluntary basis. Each course (subject) was considered one specific teaching-learning process.

Instruments

A validated Spanish version ( 62 ) of the Connor-Davidson Resilience scale , CD-RISC Scale ( 63 ) was used to measure resilience. Answers range from 1 (“Not true at all”) to 5 (“True nearly all the time”). Adequate reliability and validity values had been obtained in Spanish samples, and a five-factor structure emerged [Chi-square = 1,619, 170; Degrees of freedom (350-850) = 265; p < 0.001; Ch/Df = 6,110; SRMR (Standarized Root Mean-Square) = 0.062; NFI (Normed Fit Index) = 0.957; RFI (Relative Fix Index) = 0.948; IFI (Incremental Fix Index) = 0.922; TLI (Tucker Lewis index) = 0.980; CFI (Comparative fit index) = 0.920; RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error) = 0.063; HOELTER = 240 ( p < 0.05) and 254 ( p < 0.01)]. F1: Persistence/tenacity and strong sense of self-efficacy (TENACITY; alpha = 0.80); F2: Emotional and cognitive control under pressure (STRESS; alpha = 0.80); F3: Adaptability/ability to bounce back (CHANGE; alpha = 0.77); F4: Perceived Control (CONTROL; alpha = 0.77), and F5: Spirituality (alpha = 0.71).

The positivity scale Escala de Positividad , by Caprara et al. ( 64 ), was used to measure this variable. Ten items are to be answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Acceptable values were obtained in our sample from the Spanish validation data [Chi-square = 208.992; Degrees of freedom (58-20) = 38; p < 0.001; Ch/Df = 5,499; SRMR (Standarized Root Mean-Square) = 0.062; NFI (Normed Fit Index) = 0.901; RFI (Relative Fix Index) = 0.894; IFI (Incremental Fix Index) = 0.912; TLI (Tucker Lewis index) = 0.923, CFI (Comparative fit index) = 0.916; RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error) = 0.085; HOELTER = 260 ( p < 0.05) and 291 ( p < 0.01)]. Good internal consistency was also found (Alpha = 0.893; Part 1 = 0.832, Part 2 = 0.813; Spearman-Brown = 0.862; Guttman = 0.832).

Coping Strategies

This variable was measured using the Escala Estrategias de Coping (Coping Strategies Scale), EEC, in its original version ( 65 ), validated for University students ( 66 ). Theoretical-rational criteria were used in constructing this scale, taking the Lazarus and Folkman questionnaire ( 67 ) and coping assessment studies by Moos and Billings ( 68 ) as foundational. Validation of the original, 90-item instrument produced a first-order structure with 64 items and a second-order structure with 10 factors and two dimensions, both of them significant. Answers range from 1 (“Not true at all”) to 5 (“True nearly all the time”). The second-order structure showed adequate fit values (Chi-square = 378.750; Degrees of freedom (87-34) = 53, p < 0.001; Ch/Df = 7,146; SRMR = 0.071; NFI = 0.901; RFI = 0.945; IFI = 0.903, TLI = 0.951, CFI = 0.903). Reliability was confirmed with the following measures: Cronbach alpha values of 0.93 (complete scale), 0.93 (first half) and 0.90 (second half), Spearman-Brown of 0.84 and Guttman 0.80. There are eleven factors and two dimensions: (1) Dimension: emotion-focused coping, F1. Fantasy distraction; F6. Help for action; F8. Preparing for the worst; F9. Venting and emotional isolation; F11. Resigned acceptance. (2) Dimension: problem-focused coping, F2. Help seeking and family counsel; F5. Self-instructions; F10. Positive reappraisal and firmness; F12. Communicating feelings and social support; F13. Seeking alternative reinforcement.

Engagement-Burnout

Adequate reliability and construct validity indices for this construct have been found in cross-cultural investigations. Engagement was assessed using a validated Spanish version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students ( 69 ). Satisfactory psychometric properties were found with a sample of students from Spain. The model obtained good fit indices, and the second-order structure had three factors: vigor, dedication, and absorption. Answers range from 1 (“Not true at all”) to 5 (“True nearly all the time”). Scale unidimensionality and metric invariance were also confirmed in the samples assessed (Chi Square = 592.526, df = 74, p < 0.001; Ch/Df = 8,007; SRMR = 0.057; CFI = 0.954, TLI = 0.976, IFI = 0.954, TLI = 0.979, and CFI = 0.923; RMSEA = 0.083; HOELTER = 153, p < 0.05; 170 p < 0.01). The Cronbach alpha for this sample was 0.900 (14 items), with 0.856 (7 items) and 0.786 (7 items) for the two parts.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory, MBI ( 70 ), in its validated, open format Spanish version ( 69 ), was used to assess Burnout. Answers range from 1 (“Not true at all”) to 5 (“True nearly all the time”). Psychometric properties for this version were satisfactory in students from Spain. Good fit indices were obtained in this sample, and a second-order structure of three factors: exhaustion or depletion, cynicism, and lack of effectiveness. Scale unidimensionality and metric invariance were also confirmed in the samples assessed (Chi Square = 667.885, df = 87, p < 0.001; Ch/Df = 7,67; CFI = 0.956, TLI = 0.964, IFI = 0.951, TLI = 0.951, and CFI = 0.953; RMSEA = 0.071; HOELTER = 224, p < 0.05; 246 p < 0.01). The Cronbach alpha for this sample was 0.874 (15 items); the two parts of the scale showed 0.853 (8 items) and 0.793 (7 items), respectively.

In a single study, after signing their informed consent, students completed the validated questionnaires on an online platform. Scale completion was voluntary ( 71 ); students reported on five specific teaching-learning processes, each one representing a different University subject they took during a 2-year academic period. Presage variables were assessed in September-October of 2018 and 2019, Process variables in February-March of 2018 and 2019, and Product variables in May-June of 2018 and 2019. The respective Ethics Committees of the two universities approved the procedure, in the context of an R&D Project (2018-2021).

Data Analyses

The ex post-facto design ( 72 ) of this cross-sectional study involved bivariate association analyses, multiple regresion and structural predictions (SEM). The preliminary analyzes were carried out to guarantee the adequacy in the use of the parametric analyzes carried out: normal distribution (Kolmogoroff-Sminorf), skewness and kurtosis (±0.05).

Correlation Analysis

In order to test the association hypotheses in H1, H2, and H3, we correlated positivity with the variable resilience, coping strategies, and engagement-burnout variables (Pearson bivariate correlation), using SPSS (v.25). The assumptions assumed and contrasted for the Pearson correlation were: (1) The data must have a linear relationship, this was determined through a scatter plot; (2) The variables must have a normal distribution; (3) The observations used for the analysis should be collected randomly from the reference population.

Prediction Analysis

For the prediction hypotheses of H1, H2, and H3, multiple regression analyses were carried out, and Beta indices of prediction and significance were calculated, using SPSS (v.25). The correlation and prediction factors were calculated using the factors originating from the exploratory factor analysis, prior to the confirmatory factor analysis.

Structural Equation Model

Two different Structural Equation Models (SEM) models were tested. In the first model, the effect of gender and the mediating prediction of engagement-burnout as predictors of coping strategies (Resilience → Positivity → Engagament-Burnout → Coping strategies) was evaluated; in the second model, the prediction presented in the graph and significantly valid (Resilience → Positivity → Coping strategies → Engagament-Burnout). Model fit was assessed by first examining the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio as well as the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Normed Fit Index (NFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and Relative Fit Index (RFI). These should ideally be >0.90. The Hoelter Index was also used to determine sample size adequacy ( 73 ). AMOS (v.26) was used for these analyses. Indirect effects values were assumed to be: the regression coefficients for small (0.14), medium (0.39), and large (0.59) effects are interpreted under the assumption that the error variances of the mediator and the dependent variable are both 1.0 ( 74 ). Direct, indirect and total effects, their significance levels and confidence intervals ( 75 , 76 ) were calculated by bootstrapping (1,000 samples), using the maximum likelihood method ( 77 ). For the specific calculation of the confidence intervals of the indirect effects (Specific Indirect Effects mediation AMOS plugin, V.26) were used.

Descriptive Preliminary Results

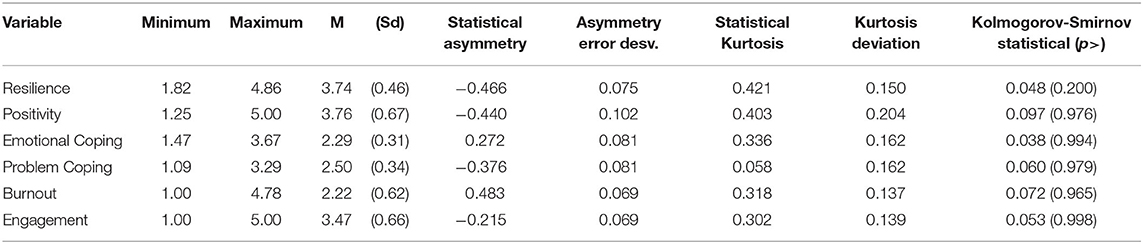

The direct and statistical values found in the preliminary sampling normality and adequacy tests showed acceptable values for the subsequent linear analysis of association and structural prediction carried out. See Table 1 .

Table 1 . Descriptive values of the analyzed variables.

Bivariate Association Relations

Resilience and positivity.

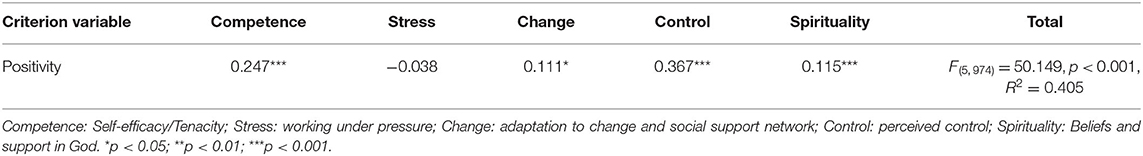

The bivariate correlational analyses between resilience (total and factors) and positivity showed a significant positive association between the two, with particular associative strength for perceived control and tenacity. See Table 2 .

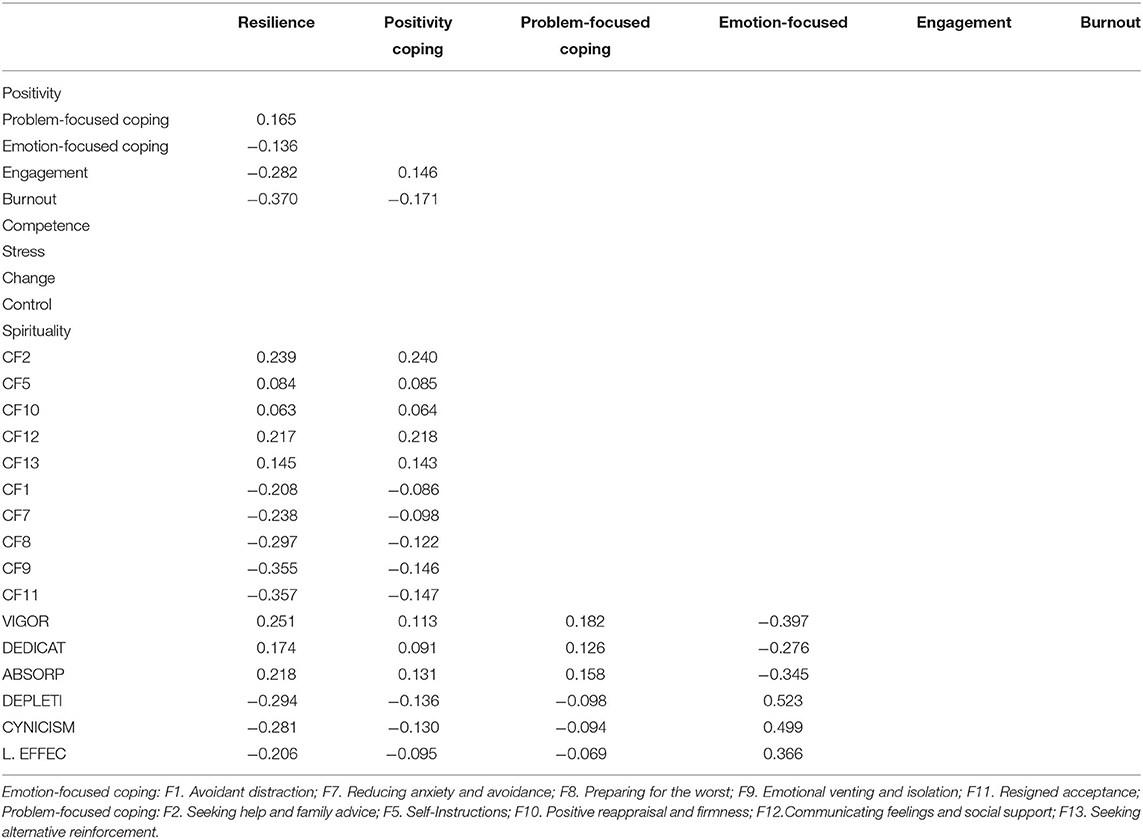

Table 2 . Bivariate correlations between resilience and positivity ( n = 1,069).

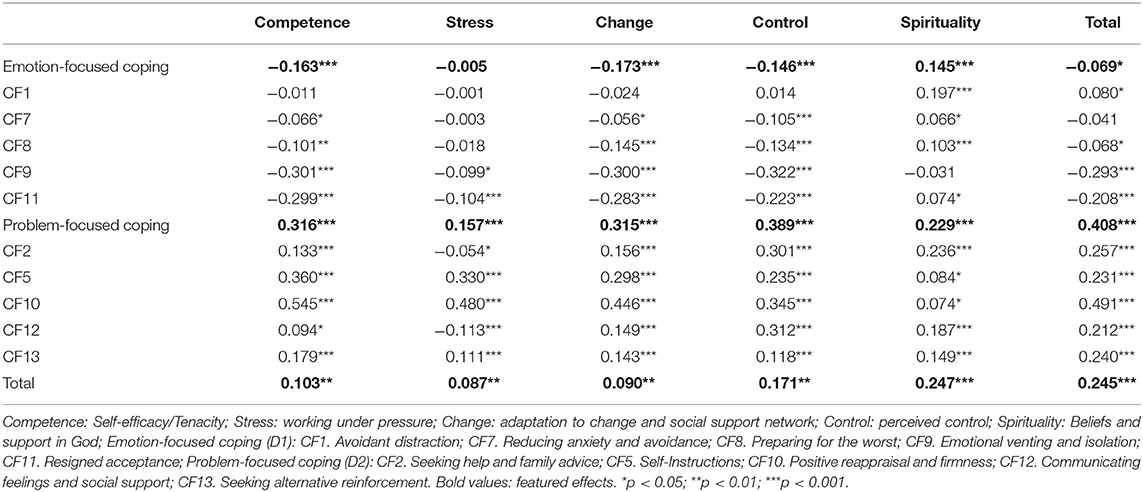

Bivariate correlational analyses between resilience (total and factors) and coping strategies showed several significant relationships. On one hand, the total resilience score was positively associated with total coping strategies ( r = 0.245, p < 0.001). In general, all the factors or components of resilience appeared to be associated positively with coping strategies focused on the problem and negatively with factors focused on emotion, except for spirituality, which appeared positively associated with both. Specifically, this association was positive with problem-focused strategies (CF2. Seeking help and family advice; CF5. Self-Instructions; CF10. Positive reappraisal and firmness; CF12. Communicating feelings and social support; CF13. Seeking alternative reinforcement), and negative with emotion-focused strategies (CF8. Preparing for the worst; CF9. Emotional venting and isolation; CF11. Resigned acceptance). Three resilience factors followed this tendency, namely: perceived control (control), acceptance of change (change) and tenacity and perception of competence (competence). The tolerance to stress factor (stress) was low related to emotion-focused strategies (only with CF9. Emotional venting and isolation; CF11. Resigned acceptance). The only factor that was positively associated both with emotion-focused strategies and with problem-focused strategies was spirituality (CF1. Avoidant distraction; CF8. Preparing for the worst; CF11. Resigned acceptance). Of special interest is the negative association between the components of resilience and the CF9 factor (Emotional venting and isolation), as a precursor coping factor for health problems. See Table 3 .

Table 3 . Bivariate association of resilience with specific strategies for coping with stress ( n = 1,069).

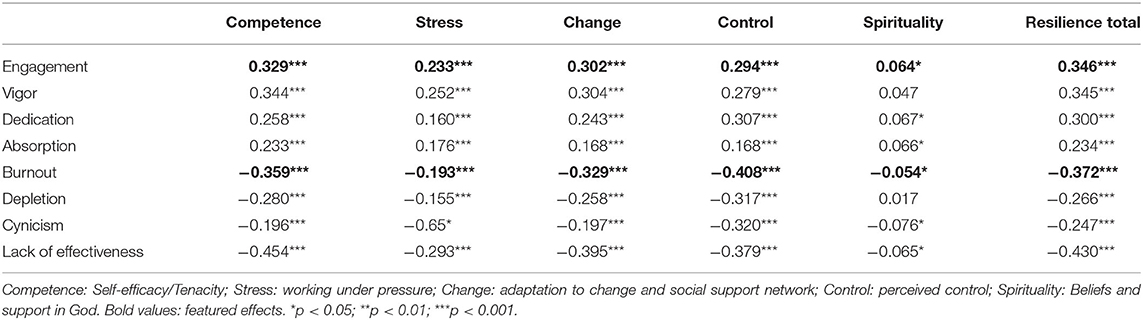

Resilience and Engagement vs. Burnout

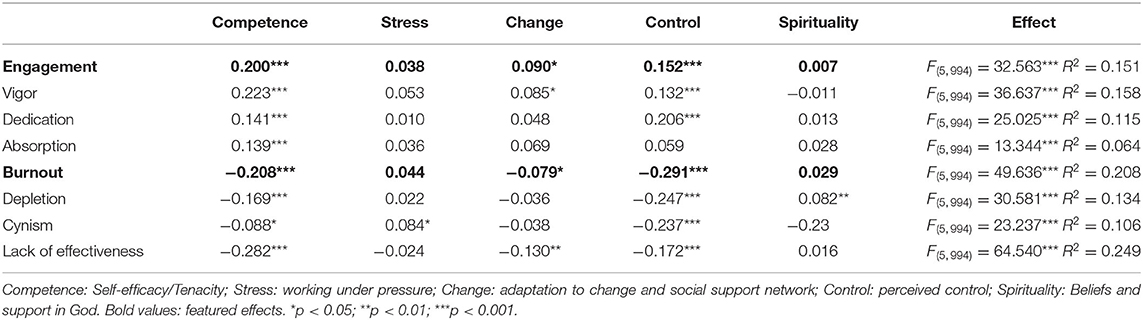

Total resilience was found to be consistently, significantly, and positively associated with engagement ( r = 0.346 ; p < 0.001) and its components, and negatively with burnout ( r = −0.372 ; p < 0.001) and its components, with particular associative strength for the component lack of effectiveness . Certain resilience factors were significantly associated with engagement and burnout, positively for the former, negatively for the latter: tenacity and perceived competence ( competence ), adaptation to change (change) , perceived control (control) , and stress tolerance (stress) were found to be positively associated with engagement; the component with the least associative strength was spiritual beliefs (spirituality) . Complementarily, the resilience factors that appeared negatively associated with burnout were tenacity and perceived competence (competence) , perceived control (control) , and adaptation to change ( change ). Moreover, the resilience factors that appeared negatively associated with burnout were the tenacity and perceived competence (competence) , perceived control (control) , and adaptation to change (change); with a lower associative force, the stress tolerance (stress) and spiritual beliefs (spirituality) . See Table 4 .

Table 4 . Bivariate associations of resilience and engagement-burnout ( n = 1,069).

Multiple Prediction Relations

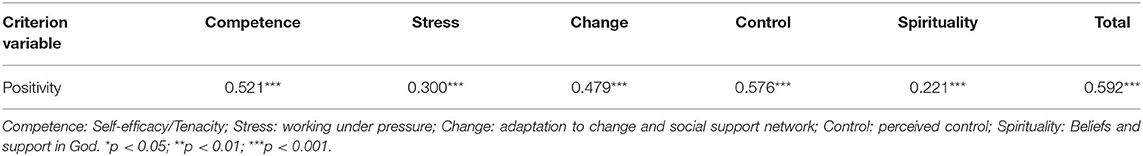

The multiple regression analysis showed a significant prediction effect of resilience factors on positivity. The resilience factors with the greatest positive predictive statistical effect were Perceived competence, Perceived control, and Spirituality. However, Tolerance to stress (stress) was not predictive of positivity. See Table 5 .

Table 5 . Regression relations between resilience components and positivity ( n = 1,069).

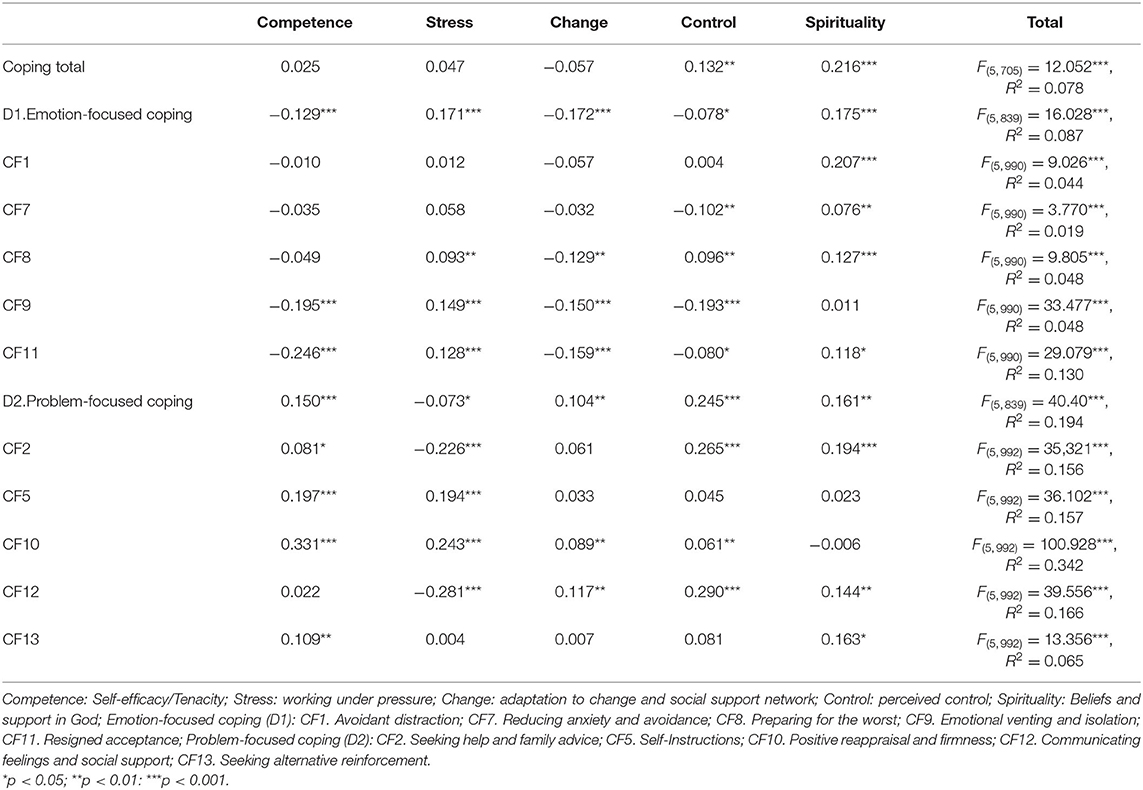

Results of multiple regression showed three types of relations between resilience factors and coping strategies: (1) factors that negatively predicted the use of emotion-focused strategies and positively predicted problem-focused strategies: perceived control, adaptation to change , and perceived competence ; (2) one factor that positively predicted the use of emotion-focused strategies and negatively predicted problem-focused strategies: stress management ; (3) one factor that predicted the combined use of both strategy types: Spirituality .

It should be noted that in the case of emotion-focused strategies, the factors that were predicted with the most statistical force -significant and moderate correlation- were CF9 ( Emotional venting and isolation ) and CF11 (Resigned acceptance ), while in problem-focused strategies, they were CF10 (Positive reappraisal and firmness), CF12 (Communicating feelings and social support), and CF5 (Self-Instructions). Of special note is Factor CF9, which was negatively predicted by the factors perceived competence, perceived control and adaptation to change . However, it was positively predicted by the stress management factor and unassociated with spirituality . See Table 6 .

Table 6 . Multiple regression of resilience to dimensions and factors of coping strategies ( n = 1,069).

Resilience and Engagement-Burnout

Results of multiple regression showed three types of relations between resilience factors and the motivational state of engagement-burnout: (1) factors that negatively predicted burnout, and positively predicted engagement, as well as its components: perceived competence, perceived control , and adaptation to change . Perceived competence positively predicted, with greater strength, the components of vigor, dedication and absorption; perceived control was a significant negative predictor of the emotional state of depletion, cynicism and lack of effectiveness; adaptation to change had the same tendency, but with less strength; (2) two factors that did not significantly predict burnout and engagement: tolerance of stress and spirituality . The only factor that positively and significantly predicted depletion was spirituality . See Table 7 .

Table 7 . Multiple regression of resilience to engagement-burnout ( n = 1,069).

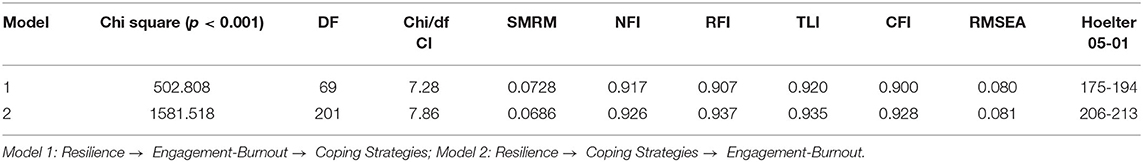

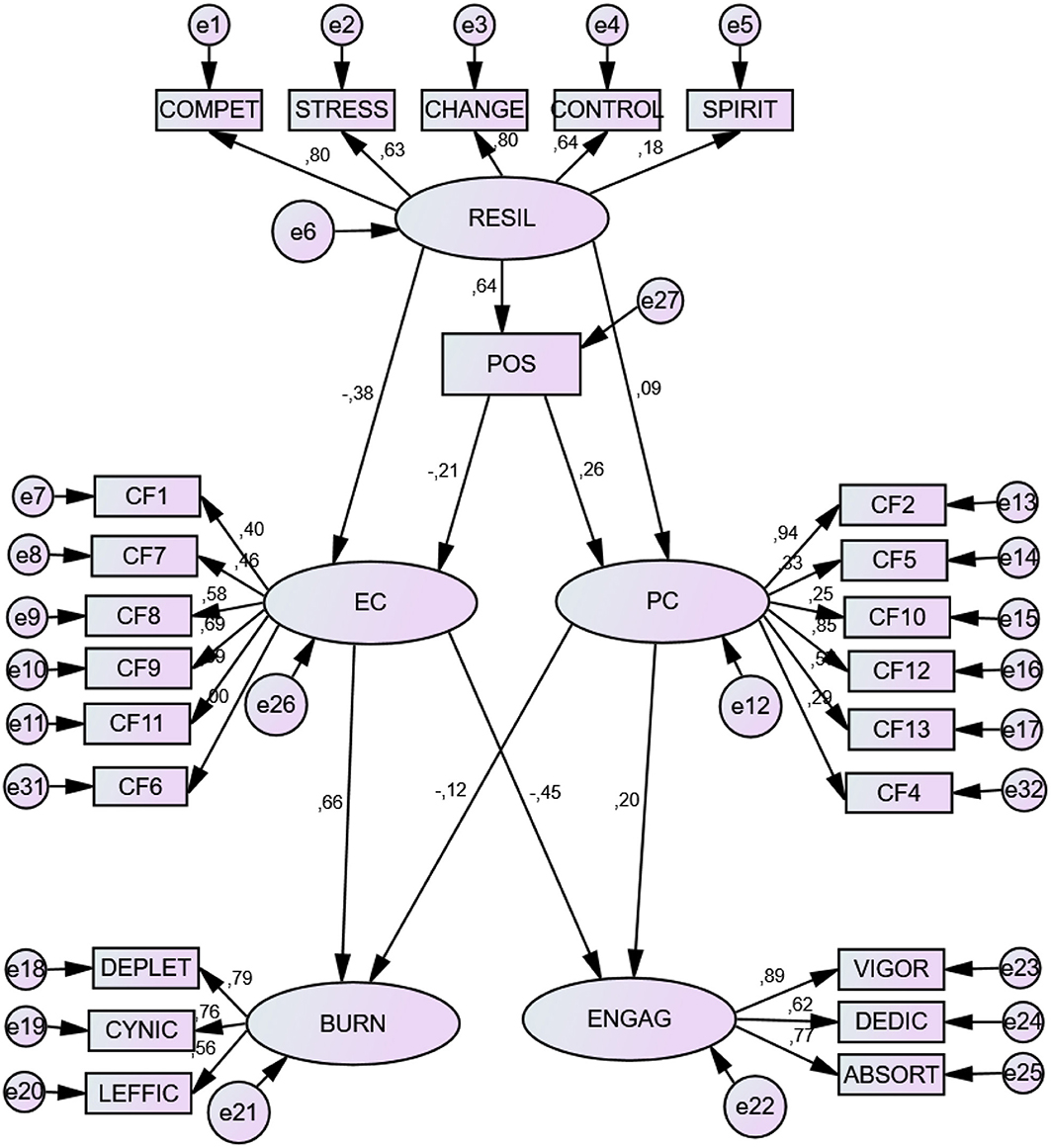

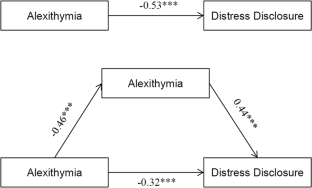

Structural Prediction Model

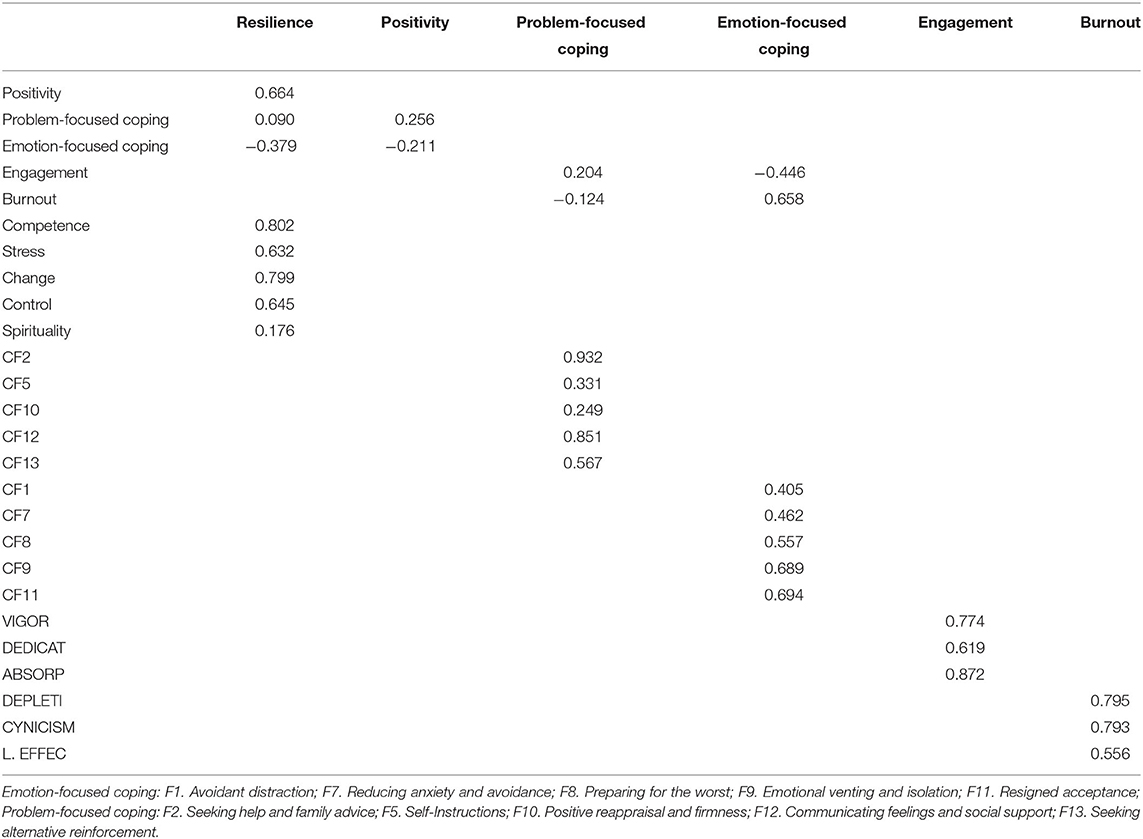

Evidence was obtained of association and prediction relationships between resilience factors, coping strategies and engagement-burnout. Different significant associations (positive or negative) appeared between resilience factors and factors of coping strategies. The negative relationship to burnout factors, and positive relation to engagement factors, was especially important. The SEM results showed an acceptable relationship model. See Table 8 and Figure 1 .

Table 8 . Models of structural linear results of the variables ( n = 1,069).

Figure 1 . Structural prediction model. RESIL, resilience; POS, Positivity; EC, Emotional Coping; PC, Problem Coping; BURN, Burnout; ENGAG, Engagement. COMPET, Persistence/tenacity and strong sense of self-efficacy; STRESS, Emotional and cognitive control under pressure; CHANGE, Adaptability/ability to bounce back; CONTROL, Perceived Control; SPIRIT, Spirituality. Emotion-focused coping: F1. Avoidant distraction; F7. Reducing anxiety and avoidance; F8. Preparing for the worst; F9. Emotional venting and isolation; F11. Resigned acceptance; Problem-focused coping: F2. Seeking help and family advice; F5. Self-Instructions; F10. Positive reappraisal and firmness; F12. Communicating feelings and social support; F13. Seeking alternative reinforcement. DEPLET, depletion; CYNIC, Cynicism; LEFFIC, Lack of effectiveness; VIGOR, vigor; DEDIC, Dedication; ABSORT, Absorption.

Direct Effects

There were several significant, direct prediction effects. Resilience showed a significant predictive effect on positivity. These two in conjunction appeared as positive predictors of problem-focused coping and negative predictors of emotion-focused coping . While resilience was the best negative predictor of emotion-focused coping, positivity was the best predictor of problem-focused coping . The factors that appeared with the most weight in the construct were perceived competence, ability to adapt to change , and perceived control .

Problem-focused coping was a positive predictor of engagement and negative predictor of burnout, while emotion-focused coping was a positive predictor burnout and negative predictor of engagement . F2 (Seeking help and family advice) and F12 (Communicating feelings and social support) were the factors with most weight in problem-focused coping , referring to social support; F11 (Resigned acceptance) and F9 (Emotional venting and isolation) had the most weight in emotion-focused coping .

Absorption and vigor were the factors with most weight in engagement; depletion; and cynicism had the most weight in burnout (See Table 9 ). Specific partial direct effects are shown in Table 10 .

Table 9 . Standardized direct effects (default model).

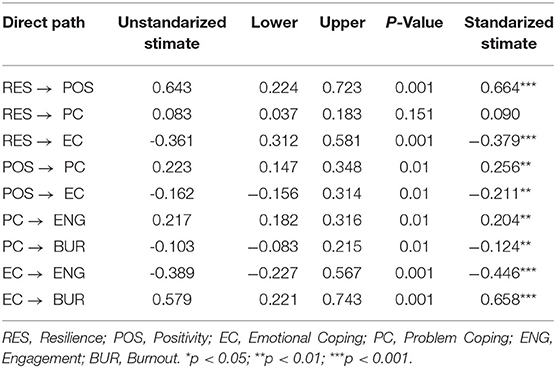

Table 10 . Direct effects specific and partial standardized values (95% B-CCI).

Indirect Effects

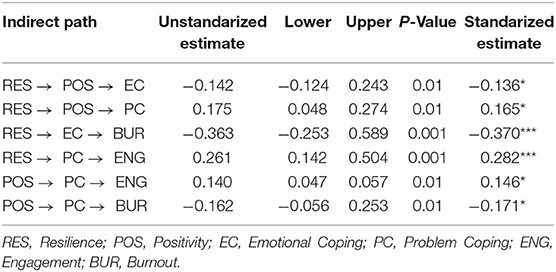

There were several indirect positive effects of Resilience and Positivity. Both variables showed multiple predictive indirect effects, in the same direction as the direct effects. Likewise, Coping Strategies had indirect effects on the components of Engagement and of Burnout: problem-focused strategies showed positive effects on Engagement and negative effects on Burnout, while emotion-focused strategies had inverse effects. Specifically, Resilience indirectly and positively predicted F2 (Seeking help and family advice) and F12 (Communicating feelings and social support), and negatively F9 (Emotional venting and isolation) and F11 (Resigned acceptance). It also positively and indirectly predicted the components of engagement and negatively the components of burnout. In a complementary way, Positivity indirectly and positively predicted F2 (Seeking help and family advice) and F12 (Communicating feelings and social support), and negatively F8 (Preparing for the worst). Finally, the strategies focused on the problem had an indirect and positive predictive effect on the engagement factors and negative on the burnout factors; however, the strategies focused on emotion had the reverse, that is, an indirect positive prediction on burnout and negative on engagement (see Table 11 ). Specific partial indirect effects are shown in Table 12 .

Table 11 . Standardized indirect effects (default model).

Table 12 . Indirect effects specific and partial standardized values (95% B-CCI).