Can online travel agencies contribute to the recovery of the tourism activity after a health crisis?

Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences

ISSN : 2632-279X

Article publication date: 14 July 2023

Issue publication date: 28 August 2023

Online travel agencies (OTAs) have an important role to play in reactivating tourism activity following a health crisis by providing information about the health conditions of tourist destinations. Once developed, it is necessary to analyze the effectiveness of the information provided and ascertain whether the provision of such information effects the understanding of the value of using OTAs and, in turn, the intention to do so.

Design/methodology/approach

This paper, based on an empirical case study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, examines whether following a health crisis, the quality of information provided by OTAs on the health conditions of tourist destinations and the perceived value of their offer generate a greater OTA services reuse intention, and signals, therefore, a return to travel.

The results show the quality of the information positively influences the perceived value, but not the OTA services reuse intention. Rather, the perceived value positively influences the OTA services reuse intention.

Practical implications

Overall, it can be suggested that providing quality health information for a destination is a necessary strategy because it contributes to increasing the perceived value of OTAs. To incentivize the intention for repeated use of OTA services, it is necessary to consider the perceived value that influences the intention to make repeat OTA reservations.

Originality/value

This research offers a novel perspective about the OTAs’ contribution to the recovery of the activity of the tourism industry after a health crisis. This contributes to achieving a more resilient sector in the face of future health crises.

- Health crisis

- Online travel agencies

- Information quality

- Perceived value

- Reservation intention

- Intention to travel

Polo Peña, A.I. , Andrews, H. and Morales Fernández, V. (2023), "Can online travel agencies contribute to the recovery of the tourism activity after a health crisis?", Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences , Vol. 5 No. 4, pp. 271-292. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHASS-12-2022-0171

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Ana Isabel Polo Peña, Hazel Andrews and Victor Morales Fernández

Published in Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was a stark reminder of the way in which tourism supply and demand is sensitive to both natural and anthropogenic crises. As future pandemics, which may have similar devastating effects on the tourism industry, cannot be ruled out ( Ivanova et al. , 2021 ; Magno and Cassia, 2022 ), it is important to identify strategies and mechanisms that contribute towards the sector’s recovery ( Sampaio et al. , 2022 ).

Studies that show the evolution of the extensive literature specializing in the study of crises in the tourism and hospitality industry identify a need to understand more about the impacts on consumer behaviour of market mechanisms and strategies (e.g. Berbekova et al. , 2021 ; Li et al. , 2022 ; Wut et al. , 2021 ). Although these works have focused on the perspective of the company (managers or employees), there is a gap in the literature regarding the effect that the adoption of these strategies exerts from the perspective of the market. The study of the effect that response measures to health crises adopted by companies have on consumer behaviour is key to moving forward in the face of potential future health crises. In a crisis context, and from the perspective of the consumer, the psychometric or “revealed preference approach” ( Fischhoff et al. , 1978 ; Slovic, 1987 ) is used to identify and test factors that help to mitigate tourists’ perceived risk and restimulate the desire to travel.

Online travel agencies (OTAs) are the leading tourist intermediary in the distribution of tourist services as an instrument for managing trips and searching for information pre-stay ( Cortés Bello and Vargas Martínez, 2018 ). OTAs have enough potential to generate consumer participation in the purchase choice process and during the search for information ( Harrigan et al. , 2017 ). In addition, consumers appreciate information provided by OTAs. This is because OTAs facilitate the reduction of the perceived risk about if one should travel and to where that occurs as part of the travel decision-making process. This is even more pertinent during periods of crises and the resulting greater uncertainty ( Gössling et al. , 2020 ; Menchero Sánchez, 2020 ).

Considering the capacity and potential of OTAs to offer value to the customer, it is worth analyzing whether offering a higher perceived value contributes to generating a greater intention to book a trip and therefore to travel again following a crisis. Among the different elements that OTAs can face to provide a service with high perceived value is time saved in the search for information about choices available ( Sarmiento Guede, 2017 ), affordable prices ( Rodríguez et al. , 2015 ), ease of usage ( Dwikesumasari and Ervianty, 2017 ) and service quality ( Talwar et al. , 2020 ). In addition, using an OTA at the height of the pandemic, and in its immediate aftermath, negated the need for an in-person visit to high street travel agencies, which afforded a greater sense of safety because it allowed social distancing.

Considering the need for information in accordance with the new trends of responsibility in public health ( De la Puente Pacheco, 2015 ), tourists are concerned about obtaining health information during trip planning. Accordingly, OTAs can adopt communication strategies based on the health information at a destination ( Wang and Lopez, 2020 ). At the same time, there is evidence that providing information about a destination’s sanitary conditions has a positive influence on the behaviour of potential tourists. This is especially during public health crises, when the perception of risk and concern for safety are most pronounced ( Jiang and Wen, 2020 ; Wang and Lopez, 2020 ).

The implications of variables, such as the quality of information in purchasing decisions within the online context, have been studied as an instrument to measure the quality of service and as an antecedent of the repurchase intentions ( Matute Vallejo et al. , 2015 ). The quality of information is also recognized as an important factor in the adoption of information by the electronic user ( Cheung et al. , 2008 ). There is, however, a lack of research that analyzes the influence of the quality of the information provided about the sanitary conditions of a destination during a health crisis and the impact on the perceived value and the intention to make travel reservations.

The lack of understanding about the influence of the quality of information about the sanitary conditions of a destination during a health crisis will be addressed in this paper. The overall aim of this study focuses in a novel way on identifying whether the provision of quality information about the health conditions of tourist destinations and the offer provided by OTAs (collected with the variable of perceived value) constitutes actions capable of prompting potential tourists to make reservations again, and therefore to travel in the context of a health crisis, such as that generated by COVID-19. More specifically, the research objectives are (1) to analyze whether the perceived value provided by OTAs has a positive influence on the OTA services reuse intention in the context of a health crisis, (2) to determine whether providing quality information about the sanitary conditions of the tourist destination has a positive influence on the perceived value of the offer provided by OTAs and (3) to examine whether providing quality information about the health conditions of the tourist destination has a positive influence on the OTA services reuse intention in the context of a health crisis.

Given the aim and objectives of this research it was necessary to conduct the research aims in a country that has been deeply affected by the global health emergency caused by COVID-19. Thus, Spain was selected for study because it was among one of the most badly impacted countries in terms of tourism during the crisis. This was due to the widespread restrictions placed on both domestic and international travel and government-imposed lockdowns around the world ( Gursoy and Chi, 2020 ). In addition, the tourism industry is a major economic driver in Spain ( Garrido-Moreno et al. , 2018 ).

Literature review

Online travel agencies, crisis management and the recovery of tourist activity in health crises situations.

The tourism industry is inherently vulnerable to disaster and external crises, from natural to anthropogenic incidents ( Ritchie, 2004 ). Despite some recent studies of crisis management in tourism, the field lacks research about both the impact of such events on specific organizations and responses to such events ( Faulkner, 2001 ; Ritchie, 2004 ). This section reviews existing literature on crisis management in the tourism industry. It, firstly, defines the main concepts. Secondly, it summarizes relevant studies of crisis management and recovery plans in the tourism industry.

There has been extensive discussion in the literature describing and conceptualizing what a crisis and/or disaster is. This is especially so in the context of the tourism industry ( Faulkner, 2001 ; Lo et al. , 2006 ; Ritchie, 2004 ). Faulkner (2001) conceptualizes disasters as unpredictable, catastrophic changes that originate outside an organization and over which it has very little control. As Kim et al. (2005) highlight, a disaster involves unexpected changes to which one can normally respond only after the event happens, by implementing contingency plans or responding reactively. A crisis is defined as any action or failure to act that interferes with an organization’s ongoing functions, achievement of objectives, viability or survival; or that has a detrimental personal effect on its main stakeholders ( Ritchie, 2004 ). It is argued that crises arise due to a lack of planning and proper management and could thus have been anticipated, whereas one can only respond to a disaster after the fact ( Kim et al. , 2005 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic was unique in nature, scale and complexity, combining a natural disaster with sociopolitical, economic and hospitality demand crises ( Zenker and Kock, 2020 ). To address this complex situation properly, tourism industry research must help managers implement crisis recovery and response strategies, with a view to providing valuable knowledge to inform and foster crisis-enabled transformations in the industry (e.g. Garrido-Moreno et al. , 2021 ; Romao, 2020 ; Sigala, 2020 ).

Development and implementation of crisis guidelines are essential to facilitate tourism’s recovery from negative events ( Kim et al. , 2005 ). The importance of post-crisis recovery in terms of a health issue has been discussed in the academic literature, and in terms of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a greater emphasis on how to respond to such situations (e.g. Garrido-Moreno et al. , 2021 ). Table 1 summarizes the main results of studies on health crisis management in major tourism journals (ordered chronologically), and recent studies of crisis management in the COVID-19 scenario.

The contributions collated in Table 1 are focused on the study of strategies and actions from the perspective of companies. What is missing is a consideration of the behaviour of customers. It is essential to consider the perspective of customers about the effect that measures adopted by hotels have in the recovery of tourist activity to understand the degree to which procedures are successful ( Sigala, 2020 ; Polo-Peña et al. , 2023 ). There is little research that consider the client’s point of view during a crisis (e.g. Peco-Torres et al. , 2021 ).

Indeed, Gursoy and Chi (2020) underline the need for research that provides answers to critical questions such as, for example, what are the factors that will influence consumers’ intentions to resume their consumption of tourism services ( Wang et al. , 2020 ). In crises contexts, perceived risk is a key variable affecting the changes in consumer behaviour. Perceived risk “refers to the combined measurement of ‘perceived probability’ and ‘perceived consequences’ of a certain event or activity” ( Bubeck et al. , 2012 , p. 1483). The psychometric or “revealed preference approach” is the most influential paradigm in modelling and forecasting risk perceptions and acceptance ( Fischhoff et al. , 1978 ; Slovic, 1987 ). Following on from Volgger et al. (2021) , the key insights of this risk perception/acceptance framework have been used in this research to identify and test factors that help to mitigate tourists’ perceived risk and encourage them to travel again.

The psychometric model asserts that informed awareness of a risk and how prepared someone is can increase acceptance of the risk. In general, preparedness and awareness are usually associated with increased notions of control over the risk and increased trust in the managers of the risk ( Fischhoff et al. , 1978 ; Slovic, 1992 ). This also applies in the tourism context ( Volgger et al. , 2021 ). One important method of increasing perceived control over risks is the provision of information related to the sanitary conditions of the tourist destinations that they wish to visit.

In relation to the process of tourists searching for information, an essential link in the chain of the tourism sector with the ability to influence the decision-making process of tourists are OTAs ( Ku and Fan, 2009 ). OTAs have visibility in the global market. Their use is part of the information search process that potential tourists usually carry out before travelling. This makes OTAs, therefore, ideal for providing information on the health conditions of tourist destinations that reaches the entire market ( Wang and Lopez, 2020 ). Additionally, after a health crisis, OTAs need tourists to start to reuse their accommodation services again. For this to happen, they require the use of effective strategies to guarantee the safety of potential tourists ( Niewiadomski, 2020 ; Wang and Lopez, 2020 ). In periods of crisis, intermediaries, such as OTAs, must face episodes of greater uncertainty that contribute to potential tourists perceiving a more attractive offer ( Rodríguez et al. , 2015 ) and a reduction in the perceived risk of travelling to affected areas ( Menchero Sánchez, 2020 ).

Despite the fact that much has been written about OTAs, the value they offered and the effect on consumer behaviour in times of health crises (such as COVID-19) have not, however, been previously analyzed. In addition, the role of OTAs and their use in contributing to the recovery of the tourism sector – by offering a higher perceived value and generating a greater intention to return to tourist accommodation services – have also not been assessed.

The effect of perceived value of the offer provided by online tourist intermediaries

The conceptual proposal made by Zeithaml (1988 , p. 14) defines perceived value as “the overall assessment of the utility of a product based on the perceptions of what is received and what is given”. As the perceived value construct reflects customers’ evaluations of the offer, it is considered to be the greatest indicator of key variables of customer behaviour (e.g. Gallarza and Gil, 2006 ; Polo-Peña et al. , 2012 ).

There are numerous articles that have studied the effects of perceived value on consumer behaviour. In relation to the tourist context, the empirical studies carried out show the effect of perceived value on variables such as satisfaction ( Choe and Kim, 2019 ), trust ( Bonsón et al. , 2015 ), repurchase intention ( Choe and Kim, 2019 ) or consumer loyalty ( Chang and Wang, 2011 ). While in the online context, there is also evidence of the positive effects of perceived value on web user satisfaction ( Chen and Lin, 2019 ; Chang and Wang, 2011 ), trust ( Kim et al. , 2011 ), intention to use ( Li and Shang, 2020 ), the intention to continue using ( Yang et al. , 2018 ), the intention to purchase ( Talwar et al. , 2020 ), or repurchase ( Bonsón et al. , 2015 ; Droguett et al. , 2010 ), or consumer loyalty ( Karjaluoto et al. , 2019 ; Sabiote-Ortiz et al. , 2014 ). In addition, Talwar et al. (2020) found a positive relationship between functional value (perceived value dimension) and the intention to book accommodation through OTAs ( Talwar et al. , 2020 ).

The perceived value of OTAs in a health crisis situation has a positive and significant effect on the intention to reuse their services.

Effects of the quality of information about a destination’s health situation offered by online travel agencies

The new trends in the search for well-being and greater commitment to public health, in addition to the increase in tourists’ knowledge and the information available to them ( De la Puente Pacheco, 2015 ), materialize in the search for health information as a planning action prior to embarking on a trip. In exceptional situations, like a health crisis, tourists consider that it is necessary to spend time searching for security information as an antecedent to the decision of choosing a destination ( Wang and Lopez, 2020 ). This means that tourist intermediary agents must develop communication based on messages that provide effective reassurance to those who are willing to travel ( Liu-Lastres et al. , 2019 ).

In accordance with previous crises faced by the tourism sector in recent years, the development of appropriate messaging is crucial to develop travellers’ positive perceptions about travel and destinations. This, in turn, can influence behaviour during trips, or in the phase prior to the purchase decision. When it comes to public health, the content of the messages promoted is educational in an effort to protect the public from diseases ( Liu-Lastres et al. , 2019 ), and it is well-established that the said information must be of good quality. Cheung et al. (2008) describe the quality of information within the online context. They emphasize its effectiveness as a factor to be taken into account in the adoption of information by the electronic user. In turn, the quality of the information is also part of the advantageous features offered by virtual communities ( Mellinas et al. , 2016 ).

Research that has analyzed how information quality can affect consumer behaviour in the online environment has drawn three main conclusions. Firstly, the quality of the information will facilitate the success of the tourist intermediary ( Matute Vallejo et al. , 2015 ). Secondly, this will serve to evaluate its potential ( Cheung et al. , 2008 ), and, by corollary, thirdly, the information quality would positively affect the value of purchases online, both for the functional and affective components ( Kim et al. , 2012 ).

The quality of the information about the health situation of the destination provided by the OTAs in a health crisis situation has a positive and significant effect on the perceived value.

However, studies by, for example, Matute Vallejo et al. (2015) provide empirical evidence of the effect of the quality of information as an antecedent to intention to repurchase online (through the perceived usefulness of the web), so that when the client perceives quality in the information that the online seller displays on its website, the client would be predisposed to continue acquiring the services of the same seller. This leads to the study of the effect that the quality of the information provided by the OTAs, related to the sanitary conditions of the destination, can have on a consumer’s intention to reuse OTA services during a health crisis.

The quality of information about the health situation of the destination provided by the OTAs in a health crisis situation has a positive and significant effect on the intention to reuse their services.

Figure 1 shows the proposed research model.

Methodology

Research population and sample.

The research was conducted in 2020 in Spain, at a time when there was still a heightened awareness and concern about the risks related to COVID-19. The study of the effect of the quality of the information on COVID-19 provided by OTAs required that a representative OTA of the sector be selected, and, in addition, provide information about the sanitary conditions of the tourist destinations. This led to Booking.com being selected as the OTA of reference for the development of the research. Booking.com has been the leading OTA in the market for several years ( Balagué et al. , 2016 ; Lorenzo Padilla, 2017 ). It has also incorporated, as part of its services, information regarding the sanitary conditions of tourist destinations for its users. As in the cases of Liu et al. (2020) and Sánchez-Cañizares et al. (2021) , a convenience sample was obtained, with data collected for the empirical analysis by means of a self-administered questionnaire. The sample population consists of residents in Spain, who may potentially be travellers in the short/medium term within the environment created by the virus and with previous experience in the use of OTAs. The link to the survey was shared on social networks and travel forums for Spaniards.

A total of 394 responses were received. The distribution of the sample is similar to the structure of the population of domestic tourists in Spain (e.g. Sánchez-Cañizares et al. , 2021 ) in terms of gender (49.6% men and 50.4% women) and age (16% aged 18 and 24 years; 53.6% aged 25 and 39 years, and 30.4% from 40 years).

Questionnaire and measurement scales

The questionnaire consisted of two different parts: the first includes filter questions about information regarding the health situation of the tourist destination given by an OTA ( Booking.com ). The second part included the measurement scales of variables used in the research model and the sociodemographic and psychographic profiles of the respondent.

First, the respondent was consulted about the place within Spain they would like to visit.

Second, the respondent is informed that they are to be provided with information from the OTA referring to the destination that the respondent had indicated that they wished to travel to and that this would be displayed for at least 80 s.

The information provided adopted a format like the one used by Booking.com in Spain. This information included two images with information about the sanitary conditions of the tourist destination to which they wanted to travel.

The second part of the questionnaire included the measurement scales of the variables collected in the research model ( Appendix ). Specifically, the “perceived value of OTAs in a health crisis situation” variable is measured based on the scales proposed in the literature such as, for example, by Choe and Kim (2019) , Lee et al. (2015) , Lin and Huang (2012) , Mohd Suki (2016) and Talwar et al. (2020) . The Quality of the health information of the destination variable is made up of four items adapted from Bailey and Pearson (1983) and Hur et al. (2017) , both are examples of applied research in the field of social networks and online media. The intention to reuse the OTAs’ services variable is made up of three items adapted from Matute Vallejo et al. ’s (2015) , study that analyzes the characteristics of word of mouth in the electronic context and its impact on online repurchase intention.

In addition, the variable previous image of the OTA ( Drolet et al. , 2007 ; Keppel, 1991 ), which although is not part of the research model, is included as a control variable that corrects the possible bias that can be introduced in the assessment of the relationships established between the variables analyzed.

The items of the measurement scales included Likert-type items from 1 to 7 points, with 1 being “totally disagree” and 7 “totally agree”, except for the previous image of the OTA scale that was a semantic differential.

Finally, the sociodemographic and psychographic variables of the respondents were collected.

Analysis strategy

The research model used ( Figure 1 ) shows the relationships included in the hypotheses. It is suggested that destination-related health information influences perceived value and intention to reuse OTA services, and that perceived value influences intention to reuse OTA services. Additionally, the “previous image of the OTA” variable was included as a control variable that acts on the “perceived value of OTAs in a health crisis situation” and the “intention to reuse the OTAs’ services” as a mechanism to correct the possible bias that can be introduced in the assessment of the relationships established between the variables analyzed based on the previous image of Booking.com held by the respondents in the study.

The structural equation modelling (SEM) methodology was deemed the most appropriate, given that the research model includes latent variables that are not directly observable ( Hair et al. , 2018 , pp. 541–591). SEM is a multivariate analysis technique widely used for this type of test, and it brings together methodological techniques that have been perfected over time and developed in various disciplines ( Hair et al. , 2018 , pp. 541–591). SPSS 21 and AMOS 21 data analysis software were therefore used to examine descriptive statistics and the factor structure of the proposed scales, and the hypotheses were tested using SEM. SEM allowed us to perform validation tests on the measurement scales (which requires adequate reliability and validity of the scales) and then test the relationships between the variables of the research model (to provide empirical evidence in relation to the research hypotheses proposed).

First, the psychometric properties of the proposed model were estimated and evaluated. Since the multivariate normality test of the variables included in the proposed model proved significant, the estimation was conducted using the maximum likelihood model combined with the bootstrap methodology ( Yuan and Hayashi, 2003 ). Even applying this technique, the Chi-square value remained significant. The fact that the results of the Chi-square were significant was due to its being sensitive to sample size. In this case, a valid reference was the value of Normed Chi-square, which gave a value of 1.86 – within the limits recommended in the literature. As for the overall fit of the model, the RMSEA value was (0.07). The incremental fit measures of CFI (0.91), IFI (0.92) and TLI (0.91) were also found to be adequate. Thus, the model fit can be said to be acceptable in line with the recommendations of Hair et al. (2018) .

Evaluating scale reliability and validity

The dimensions included in the research variables (“perceived value of OTAs in a health crisis situation”, “quality of the health information of the destination”, “intention to reuse the OTAs’ services” and “previous image of the OTA”) reflect the composition of the scales when their validity and reliability can be confirmed ( Devlin et al. , 1993 ). To achieve this, the standardized charges, the individual reliability coefficient ( R 2 ), the confidence interval and the significance of each one of the items included must be analyzed ( Table 2 ). The reliability indicators show a value greater or close to the minimum acceptable limit which is 0.50 ( Hair et al. , 2018 ). The next step is to verify the internal consistency of each one of the dimensions on the first-order and second-order scales. Consistency can be measured with composite reliability and variance extracted. In both cases, the values obtained are acceptable, as they are close to or above the reference value of 0.70 for composite reliability and 0.50 in the case of variance extracted ( Hair et al. , 2018 ) ( Table 2 ). The results obtained to date lead to the conclusion that the set of first-order dimensions proposed to measure perceived value – quality information, OTA services reuse intention and previous image is valid – given that it allows the existence of adequate validity and reliability to be confirmed.

As regards second-order construct, Table 2 shows the standardized charges, individual reliability, confidence intervals, and the level of significance for each of the first-order dimensions included, as well as for the composite reliability and variance extracted for second-order construct. It can be seen that the scale for perceived value offers individual reliability levels above or close to 0.50. That is, with the exception of the social dimension which show a value lower than the recommended levels are not removed from the model. This is because their removal does not significantly improve the overall fit of the model and can adversely affect the validity of the content ( Hair et al. , 2018 ). Similarly, overall these results contribute to determining that the second-order scale referring to perceived value has a high level of internal consistency.

Finally, the discriminant validity was assessed among the different variables and dimensions included in the research model. For this, the method proposed by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) is used according to which, for there to be adequate discriminant validity, the confidence interval of the estimated correlation coefficient must not include the value “1”. The results achieved in relation to the measurement scales used in the study indicate that the scales are adequate for measuring each of the variables included in the research model ( Table 3 ).

Taken together, the results show that the measurement scales used for the variables of perceived value, quality information, OTA services reuse intention and previous image provide adequate convergent and discriminant validity.

Evaluating the research model

Returning to the proposed research model, it is necessary to consider the effect that the previous image of the OTA exerts as a control variable. The previous image of the OTA does not have a significant effect on the perceived value (since the standardized load is 0.14, with a p -value ≥0.05). It does, however, on the intention to reuse the OTAs’ services with a p -value ≤1% (with a standardized load of 0.29). These results show the adequacy of having considered the previous image of the OTA variable as a control variable, since it has allowed bias correction introduced in the research model.

Next, the relationships between information quality, perceived value of OTAs and OTA services reuse intention with the current health crisis conditions were analyzed ( Figure 2 ):

Hypothesis 1 proposed that perceived value of OTAs in a health crisis situation has a positive and significant effect on OTA services reuse intention with the conditions of the health crisis. The results showed a statistically significant relationship between the two variables ( p -value≤ 0.01). The direct effect was 0.60, with a confidence interval of between 0.39 and 0.77. Thus, there is empirical support for this hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2 proposes that quality of the health information of the destination has a positive and significant influence on perceived value of OTAs in a health crisis situation. The results showed a statistically significant relationship ( p -value≤ 0.01), with a direct effect of 0.51 and a confidence interval of between 0.33 and 0.65. Therefore, this hypothesis also finds empirical support.

Hypothesis 3 proposed that quality of the health information of the destination has a positive and significant effect on the OTA services reuse intention with the conditions of the health crisis. The results showed a non-statistically significant relationship between the two variables ( p -value = 0.37). The standardized coefficient was 0.09, with a confidence interval of between −0.07 and 0.26. Thus, there is no empirical support for this hypothesis.

Discussion, conclusions and implications

The COVID-19 global pandemic had profound impacts on the travel and tourism industry. Similarly, future scenarios cannot be discounted ( Ivanova et al. , 2021 ; Li et al. , 2022 ; Magno and Cassia, 2022 ). Further, the COVID-19 pandemic generated conditions that allowed the sector to identify actions and strategies that can contribute to achieving greater resilience ( Kumar et al. , 2022 ; Li et al. , 2022 ).

In this paper, we have considered the development of the study of crisis management before and during the pandemic. The systematic review made it possible to identify an interest in obtaining greater knowledge about the use of market mechanisms and strategies, and their effects on consumer behaviour (e.g. Berbekova et al. , 2021 ; Li et al. , 2022 ; Wut et al. , 2021 ). Chen et al. (2022) found that although previous epidemic research has foregrounded consumers’ perceptions of risk and associated changes to their travel behaviour, potential strategies for ameliorating such behavioural changes while maintaining safety and security have mainly been ignored. Such strategies should not simply be applied, but preferably carefully measured by researchers for their impacts on consumers’ behaviour. This paper addresses this concern by offering original insights into whether providing quality information about the sanitary conditions of the destination influences the perceived value offered by OTAs and the reuse intention. It provides empirical evidence indicating that (1) providing quality information on the sanitary conditions of the destination influences the perceived value of the OTAs, but not the reuse intention; although, (2) the perceived value offered by the OTAs positively influences the OTA services reuse intention.

In accordance with emerging trends, such as a greater commitment to public health and a search for well-being ( De la Puente Pacheco, 2015 ), in times of crises and situations of uncertainty, tourists are increasingly searching for quality information that guarantees their safety during a trip ( Félix Mendoza et al. , 2020 ). The quality of the information must be present in the context of social networks and, even more so, in the offer of OTAs ( Mellinas et al. , 2016 ). In the research for this paper, a strategy based on risk communication and guidelines has been proposed as prevention and protection instruments for tourists that can be implemented by tourist intermediaries. For this study, this information was explicitly included through the information quality variable ( Cheung et al. , 2008 ).

More knowledge is needed regarding the effect that the adoption of this type of action generates from the market perspective in key variables of consumer behaviour (e.g. Volgger et al. , 2021 ). From the “revealed preference approach” ( Fischhoff et al. , 1978 ; Slovic, 1987 ), this research gives empirical evidence about the effect of factors that affect the risk perception and the perceived control tourists exert on perceived value and the intention to resume using OTA services.

The findings of this research make several contributions to knowledge. Firstly, specialized literature on crisis management in the tourism and hospitality industry shows interest in knowing more about the use of market-oriented actions and their impacts on consumer behaviour (e.g. Wut et al. , 2021 ; Li et al. , 2022 ). Also, Chen et al. (2022) recognize that it is necessary to develop a greater knowledge about consumers’ perceptions of risk and associated changes to their travel behaviour and how taking action can contribute to ameliorating the reuse and value of services when travelling while maintaining safety and security.

Specifically, the findings make several contributions to knowledge. There is previous literature examining the quality of health information about a destination and the subsequent effects on the perceived value in the online tourism context. For example, Cheung et al. (2008) test the influence of the quality of the information on the perceived usefulness of the user in the electronic field and Kim et al. (2012) show how information quality would positively affect the value of online purchases, on utilitarian and hedonic dimensions. The first contribution to knowledge is that the results achieved in this work mainly concur with the findings of previous research, showing that the quality of the health information of the destination has a positive influence on the perceived value of the OTA. This corroborates that when the tourist receives quality information about the situation of a health crisis at tourist destinations this, in turn, attributes a greater value to the offer proposed by the OTA.

Previous studies have identified the influence of information quality as an antecedent of the intention to repurchase online, through the influence of the perceived usefulness of the website (e.g. Matute Vallejo et al. , 2015 ), but the direct relationship between the quality of the health information of the destination and the intention to repurchase from the same OTA has not been analyzed. In this work, this relationship has been tested empirically, reaching a result according to which there is no direct significant relationship between the quality of the information related to the health situation of the destination and the OTA services reuse intention. It can be deduced from this that an improvement in the quality of information perceived by tourists would not directly influence their desire to book through the OTA’s platform. The second contribution to knowledge is that these results indicate that in situations of high uncertainty, such as a health crisis, providing quality information about the health conditions of the tourist destination is not enough to encourage potential tourists to book again through OTAs.

Lastly, it has been found that perceived value of OTAs in a health crisis situation positively and significantly influences the OTA services reuse intention in the context of a health crisis. This result is consistent with the empirical evidence of previous research, and shows that an improvement in the value perceived by the tourist of the OTAs offer would have a positive and significant impact on a tourist’s desire to travel, even in the context of a health crisis.

Considering all the results about the relationships established between the variables of quality of the health information of the destination, perceived value of OTAs in a health crisis situation and OTA services reuse intention, it can be suggested that providing quality health information about the destination is a necessary strategy because it contributes to the higher value potential tourists attribute to the offer provided by OTAs. This is not enough, however, to arouse the OTA services reuse intention (and consequently to travel). In order to incentivize the OTA services reuse intention, it is necessary to consider quality health information together with the perceived value of its offer, which does influence the intention to make repeat reservations with the OTAs.

Implications for practitioners

Some of the results of this research have practical and professional applications for tourist and hospitality intermediaries that operate online.

Recommendations can be made about the application of strategic measures appropriate to the development of the offer presented by OTAs and other tourist intermediaries. As an appropriate measure that OTAs can take advantage of to deal with tourism crises, the development and implementation of a risk and crisis communication strategy aimed at potential tourists stand out with the conviction that the perceived risk of travelling will be reduced and the security perceived by the individual in the tourist destination will be increased. At the same time, this measure must be based on quality information. In other words, it is suggested that providing quality information regarding the health situation of the tourist destination is essential information that should be incorporated into the portals of OTAs and other tourist intermediaries. To this end, in the preparation of the said information, OTAs should consult specialized organizations dedicated to studying the health crisis situation, and government institutions to provide reliable and consistent information.

The results from the research model support the idea that the actions of OTAs could contribute to awakening the desire to travel. In view of the fact that intermediary agents have the opportunity to play a relevant role in the recovery of tourist activity, these intermediaries, in addition to providing their own information and that of official government guidelines, also provide official and verified information on their web portals.

However, it has been shown that without an increase in the value of the OTAs’ offer to their users, the strategy based on the provision of quality information on the health situation of the destination is not enough to encourage the intention of the reuse of the OTAs’ services and make reservations for accommodation. In this sense, the results identify that transmitting offer of high perceived value – in which a convenience, social, emotional and epistemic value is contemplated – is key to encouraging the intention to make reservations again through the OTAs.

Taken together, the results show that the adoption of an adequate strategy by OTAs can influence the reuse intention and book accommodation, and therefore, return to travel in a pandemic context. For this, the incorporation of quality information on the sanitary conditions of the destination and transmitting offer of high perceived value is relevant.

Limitations and future research directions

Like all empirical research, this work has limitations that must be considered and, in turn, contribute to recommendations for future research. The first limitation relates to the study context. The study was carried out in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Spanish domestic market. In this respect, it can only act as a “snapshot”, small case study about the unfolding situation. Thus, the first recommendation for further research is to replicate this study in other geographical contexts, and the second is to extend the sample to the international market.

A second limitation is the choice of variables. Although variables relevant to consumer behaviour were selected, there are other relevant variables in contexts of high uncertainty and market strategies. Future research should consider other relevant variables for consumer behaviour, such as risk or perceived safety or the value of user-generated content provided by OTAs. It is also interesting that for future research, more complex research models are tested in which a greater number of variables typical of consumer behaviour and the relationships between them are included. Despite these limitations, if, as predicted, the world faces health emergencies in the future, any knowledge about how the market can respond to support the tourism sector’s recovery is of value.

Another potential line of scholarly inquiry would be to include in the research model other characteristics, or qualities, about the individual respondents that may influence their perceived risk, such as self-efficacy, in addition to considering alternative business strategies that may influence the consumer to perceive a lower risk and decide to return to using an OTA’s services.

Research model proposed

Outline of results from the proposed research model

Studies examining crisis management and strategic measures to overcome crises

Source(s): Own elaboration from literature review

Anderson , J.C. and Gerbing , D.W. ( 1988 ), “ Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach ”, Psychological Bulletin , Vol. 103 No. 3 , pp. 411 - 423 .

Bailey , J.E. and Pearson , S.W. ( 1983 ), “ ‘Development of a tool for measuring and analyzing’, computer user satisfaction ”, Management Science , Vol. 29 No. 5 , pp. 530 - 545 .

Balagué , C. , Martin-Fuentes , E. and Gómez , M.J. ( 2016 ), “ Fiabilidad de las críticas hoteleras autenticadas y no autenticadas: el caso de TripAdvisor y Booking.com ”, Cuadernos de Turismo , Vol. 38 No. 67 , pp. 513 - 516 .

Berbekova , A. , Uysal , M. and Assaf , A.G. ( 2021 ), “ A thematic analysis of crisis management in tourism: a theoretical perspective ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 86 , 104342 .

Bonsón , E. , Carvajal-Trujillo , E. and Escobar-Rodríguez , T. ( 2015 ), “ Influence of trust and perceived value on the intention to purchase travel online: integrating the effects of assurance on trust antecedents ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 47 , pp. 286 - 302 .

Bubeck , P. , Botzen , W.J.W. and Aerts , J.C. ( 2012 ), “ A review of risk perceptions and other factors that influence flood mitigation behavior ”, Risk Analysis: International Journal , Vol. 32 No. 9 , pp. 1481 - 1495 .

Chang , H.H. and Wang , H. ( 2011 ), “ The moderating effect of customer perceived value on online shopping behaviour ”, Online Information Review , Vol. 35 No. 3 , pp. 333 - 359 .

Chen , S.-C. and Lin , C.-P. ( 2019 ), “ Understanding the effect of social media marketing activities: the mediation of social identification, perceived value, and satisfaction ”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change , Vol. 140 , pp. 22 - 32 .

Chen , L.H. , Munoz , K.E. and Aye , N. ( 2022 ), “ Systematic review of crisis reactions toward major disease outbreaks: application of the triple helix model in the context of tourism ”, International Journal of Tourism Cities , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 327 - 341 .

Cheung , C.M.K. , Lee , M.K.O. and Rabjohn , N. ( 2008 ), “ The impact of electronic word-of-mouth: the adoption of online opinions in online customer communities ”, Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy , Vol. 18 No. 3 , pp. 229 - 247 .

Chien , G.C.L. and Law , R. ( 2003 ), “ The impact of the severe acute respiratory syndrome on hotels: a case study of Hong Kong ”, International Journal Hospitality Management , Vol. 22 , pp. 327 - 332 .

Choe , J.Y. and Kim , S. ( 2019 ), “ Development and validation of a multidimensional tourist's local food consumption value (TLFCV) scale ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 77 , pp. 245 - 259 .

Cortés Bello , R.D.C. and Vargas Martínez , E.E. ( 2018 ), “ Prospectiva en Agencias de Viajes: una Revisión de la Literatura (Prospective in Travel Agencies: a Revision of Literature) ”, Turismo y Sociedad , Vol. 22 , pp. 45 - 64 .

De la Puente Pacheco , M. ( 2015 ), “ Dinámica del turismo de salud internacional: una aproximación cuantitativa ”, Dimensión Empresarial , Vol. 13 No. 2 , pp. 167 - 184 .

Devlin , S.J. , Dong , H.K. and Brown , M. ( 1993 ), “ Selecting a scale for measuring quality ”, Marketing Review , Vol. 5 No. 3 , pp. 12 - 17 .

Droguett , C. , Paine , T. and Riveros , E. ( 2010 ), E-commerce en el turismo: — Modelamiento del perfil de clientes que prefieren comprar servicios turísticos por internet , Universidad de Chile , available at: http://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/108013 ( accessed 30 ovember 2022 ).

Drolet , A. , Williams , P. and Lau-Gesk , L. ( 2007 ), “ Age-related differences in responses to affective vs. Rational ads for hedonic vs Utilitarian products ”, Marketing Letters , Vol. 18 No. 4 , pp. 211 - 221 .

Dwikesumasari , P.R. and Ervianty , R.M. ( 2017 ), “ Customer loyalty analysis of online travel agency app with customer satisfaction as A mediation variable ”, available at: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/icoi-17/25880030 ( accessed 20 June 2022 ).

Faulkner , B. ( 2001 ), “ Towards a framework for tourism disaster management ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 22 No. 2 , pp. 135 - 147 .

Félix Mendoza , Á.G. , García Reinoso , N. and Vera Vera , J.R. ( 2020 ), “ Participatory diagnosis of the tourism sector in managing the crisis caused by the pandemic (COVID-19) ”, Revista Interamericana de Ambiente y Turismo - RIAT , Vol. 16 No. 1 , pp. 66 - 78 .

Fischhoff , B. , Slovic , P. , Lichtenstein , S. , Read , S. and Combs , B. ( 1978 ), “ How safe is safe enough? A psychometric study of attitudes towards technological risks and benefits ”, Policy Sciences , Vol. 9 No. 2 , pp. 127 - 152 .

Gallarza , M.G. and Gil , I. ( 2006 ), “ Desarrollo de una escala multidimensional para medir el valor percibido de una experiencia de servicio ”, Revista española de investigación de marketing ESIC , Vol. 10 No. 2 , pp. 25 - 59 .

Garrido-Moreno , A. , García-Morales , V.J. , Lockett , N. and King , S. ( 2018 ), “ The missing link: creating value with social media use in hotels ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 75 , pp. 94 - 104 .

Garrido-Moreno , A. , García-Morales , V.J. and Martín-Rojas , R. ( 2021 ), “ Going beyond the curve: strategic measures to recover hotel activity in times of COVID-19 ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 96 , 102928 .

Gössling , S. , Scott , D. and Hall , C.M. ( 2020 ), “ Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19 ”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , Vol. 29 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 20 .

Gursoy , D. and Chi , C.G. ( 2020 ), “ Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: review of the current situations and a research agenda ”, Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management , Vol. 29 No. 5 , pp. 527 - 529 .

Hair , J.F. , Black , W.C. , Babin , B.F. and Anderson , R. ( 2018 ), Multivariate Data Analysis , Prentice Hall , Madrid .

Hao , F. , Xiao , Q. and Chon , K. ( 2020 ), “ COVID-19 and China's hotel industry: impacts, a disaster management framework, and post-pandemic agenda ”, International Journal Hospitality Management , Vol. 90 No. 102636 , pp. 1 - 11 .

Harrigan , P. , Evers , U. , Miles , M. and Daly , T. ( 2017 ), “ Customer engagement with tourism social media brands ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 59 , pp. 597 - 609 .

Herédia-Colaço , V. and Rodrigues , H. ( 2021 ), “ Hosting in turbulent times: hoteliers' perceptions and strategies to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic ”, International Journal Hospitality Management , Vol. 94 No. 102835 , pp. 1 - 12 .

Hur , K. , Kim , T.T. , Karatepe , O.M. and Lee , G. ( 2017 ), “ An exploration of the factors influencing social media continuance usage and information sharing intentions among Korean travellers ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 63 , pp. 170 - 178 .

Ivanova , M. , Ivanov , I.K. and Ivanov , S. ( 2021 ), “ Travel behaviour after the pandemic: the case of Bulgaria ”, Anatolia , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 11 .

Jiang , Y. and Wen , J. ( 2020 ), “ Effects of COVID-19 on hotel marketing and management: a perspective article ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 32 No. 8 , pp. 2563 - 2573 .

Karjaluoto , H. , Shaikh , A.A. , Saarijärvi , H. and Saraniemi , S. ( 2019 ), “ How perceived value drives the use of mobile financial services apps ”, International Journal of Information Management , Vol. 47 , pp. 252 - 261 .

Keppel , G. ( 1991 ), Design and Analysis: A Researcher’s Handbook , 3rd ed. , Prentice-Hall, Incorporate , Englewood Clifts, New York .

Kim , S.S. , Chun , H. and Lee , H. ( 2005 ), “ The effects of SARS on the Korean hotel industry and measures to overcome the crisis: a case study of six Korean five-star hotels ”, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 10 , pp. 369 - 377 .

Kim , M.-J. , Chung , N. and Lee , C.-K. ( 2011 ), “ The effect of perceived trust on electronic commerce: shopping online for tourism products and services in South Korea ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 32 No. 2 , pp. 256 - 265 .

Kim , C. , Galliers , R.D. , Shin , N. , Ryoo , J.-H. and Kim , J. ( 2012 ), “ Factors influencing Internet shopping value and customer repurchase intention ”, Electronic Commerce Research and Applications , Vol. 11 No. 4 , pp. 374 - 387 .

Ku , E.C.S. and Fan , Y.W. ( 2009 ), “ The decision making in selecting online travel agencies: an application of analytic hierarchy process ”, Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing , Vol. 26 Nos 5-6 , pp. 482 - 493 .

Kumar , N. , Panda , R.K. and Adhikari , K. ( 2022 ), “ Tourists' engagement and willingness to pay behavior during COVID-19: an assessment of antecedents, consequences and intermediate relationships ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights , Vol. 6 No. 2 , pp. 1024 - 1042 .

Lai , I.K.W. and Wong , J.W.C. ( 2020 ), “ Comparing crisis management practices in the hotel industry between initial and pandemic stages of COVID-19 ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 32 No. 10 , pp. 3135 - 3156 .

Lee , C.K.C. , Levy , D.S. and Yap , C.S.F. ( 2015 ), “ How does the theory of consumption values contribute to place identity and sustainable consumption? ”, International Journal of Consumer Studies , Vol. 39 No. 6 , pp. 597 - 607 .

Leung , P. and Lam , T. ( 2004 ), “ Crisis management during the SARS threat: a case study of the Metropole hotel in Hong Kong ”, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 47 - 57 .

Li , Y. and Shang , H. ( 2020 ), “ Service quality, perceived value, and citizens' continuous-use intention regarding e-government: empirical evidence from China ”, Information and Management , Vol. 57 No. 3 , 103197 .

Li , H. , Liu , X. , Zhou , H. and Li , Z. ( 2022 ), “ Research progress and future agenda of COVID-19 in tourism and hospitality: a timely bibliometric review ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 35 No. 7 , pp. 2289 - 2321 .

Lin , P.-C. and Huang , Y.-H. ( 2012 ), “ The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values ”, Journal of Cleaner Production , Vol. 22 No. 1 , pp. 11 - 18 .

Liu , M. , Liu , Y. , Mo , Z. , Zhao , Z. and Zhu , Z. ( 2020 ), “ How CSR influences customer behavioural loyalty in the Chinese hotel industry ”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 22 .

Liu , M.T. , Wang , S. , McCartney , G. and Wong , I.A. ( 2021 ), “ Taking a break is for accomplishing a longer journey: hospitality industry in Macao under the COVID-19 pandemic ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 33 No. 4 , pp. 1249 - 1275 .

Liu-Lastres , B. , Schroeder , A. and Pennington-Gray , L. ( 2019 ), “ Cruise line customers' responses to risk and crisis communication messages: an application of the risk perception attitude framework ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 58 No. 5 , pp. 849 - 865 .

Lo , A. , Cheung , C. and Law , R. ( 2006 ), “ The survival of hotels during disaster: a case study of Hong Kong in 2003 ”, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 11 No. 1 , pp. 65 - 79 .

Lorenzo Padilla , Y. ( 2017 ), Valoraciones de los hoteles de Costa Adeje a traves de Booking y Tripadvisor , Universidad de La Laguna , available at: https://riull.ull.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/915/7506/Valoraciones%20de%20los%20hoteles%20de%20Costa%20Adeje%20a%20traves%20de%20Booking%20y%20Tripadvisor.pdf?sequence=1 ( accessed 20 June 2022 ).

Magno , F. and Cassia , F. ( 2022 ), “ Firms' responses to the COVID-19 crisis in the tourism industry: effects on customer loyalty and economic performance ”, Anatolia , Vol. 33 No. 2 , pp. 263 - 265 .

Matute Vallejo , J. , Polo Redondo , Y. and Utrillas Acerete , A. ( 2015 ), “ Las características del boca-oído electrónico y su influencia en la intención de recompra online ”, Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa , Vol. 24 No. 2 , pp. 61 - 75 .

McCartney , G. , Pinto , J. and Liu , M. ( 2021 ), “ City resilience and recovery from COVID-19: the case of Macao ”, Cities , Vol. 112 , 103130 .

Mellinas , J.P. , Martínez María-Dolores , S.M. and Bernal García , J.J. ( 2016 ), “ Evolución de las valoraciones de los hoteles españoles de costa (2011-2014) en Booking.com ”, PASOS Revista de turismo y patrimonio cultural , Vol. 14 No. 1 , pp. 141 - 151 .

Menchero Sánchez , M. ( 2020 ), “ Flujos turísticos, geopolítica y COVID-19: cuando los turistas internacionales son vectores de transmisión. Geopolítica(s) ”, Revista de estudios sobre espacio y poder , Vol. 11 , pp. 105 - 114 .

Mohd Suki , N. ( 2016 ), “ Consumer environmental concern and green product purchase in Malaysia: structural effects of consumption values ”, Journal of Cleaner Production , Vol. 132 , pp. 204 - 214 .

Niewiadomski , P. ( 2020 ), “ COVID-19: from temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? ”, Tourism Geographies , Vol. 22 No. 3 , pp. 651 - 656 .

Novelli , M. , Burgess , L.G. , Jones , A. and Ritchie , B.W. ( 2018 ), “ ‘No Ebola. still doomed’: the Ebola-induced tourism crisis ”, Annals Tourism Research , Vol. 70 , pp. 76 - 87 .

Peco-Torres , F. , Polo-Peña , A.I. and Frías-Jamilena , D.M. ( 2021 ), “ Tourists' information literacy self-efficacy: its role in their adaptation to the ‘new normal’ in the hotel context ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 33 No. 12 , pp. 4526 - 4549 .

Polo-Peña , A.I. , Frías-Jamilena , D.M. and Rodríguez-Molina , M.A. ( 2012 ), “ The perceived value of the rural tourism stay and its effect on rural tourist behaviour ”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , Vol. 20 No. 8 , pp. 1045 - 1065 .

Polo-Peña , A.I. , Andrews , H. and Torrico-Jódar , J. ( 2023 ), “ The role of health and safety protocols and brand awareness for the recovery of hotel activity following a health crisis ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights , in press .

Ritchie , B. ( 2004 ), “ Chaos, crisis and disasters: a strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 25 , pp. 669 - 683 .

Rodríguez , C. , Rodríguez , M.M. , Martínez , V. and Juanatey , O. ( 2015 ), “ La intermediación turística en España y su vinculación con el Marketing de Afiliación: una aproximación a la realidad de las Agencias de Viajes ”, Revista de turismo y patrimonio cultural , Vol. 13 No. 4 , pp. 805 - 827 .

Romao , J. ( 2020 ), “ Tourism, smart specialisation, growth, and resilience ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 84 , pp. 1 - 15 , 102995 .

Sánchez-Cañizares , S.M. , Cabeza-Ramírez , L.J. , Muñoz-Fernández , G. and Fuentes-García , F.J. ( 2021 ), “ Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel ”, Current Issues in Tourism , Vol. 24 No. 7 , pp. 970 - 984 .

Sabiote-Ortiz , C.M. , Frías-Jamilena , D.M. and Castañeda-García , J.A. ( 2014 ), “ Overall perceived value of a tourism service delivered via different media: a cross-cultural perspective ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 55 No. 1 , pp. 34 - 51 .

Sampaio , C. , Farinha , L. , Sebastião , J.R. and Fernandes , A. ( 2022 ), “ Tourism industry at times of crisis: a bibliometric approach and research agenda ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights , in press .

Sarmiento Guede , J.R. ( 2017 ), “ La experiencia de la calidad de servicio online como antecedente de la satisfacción online: estudio empírico en los sitios web de viajes ”, Investigaciones Turísticas , Vol. 13 , pp. 30 - 53 .

Sigala , M. ( 2020 ), “ Tourism and COVID-19: impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 117 , pp. 312 - 321 .

Slovic , P. ( 1987 ), “ Perception of risk ”, Science , Vol. 236 No. 4799 , pp. 280 - 285 .

Slovic , P. ( 1992 ), “ Perception of risk: reflections on the psychometric paradigm ”, in Krimsky , S. and Golding , D. (Eds), Social Theories of Risk , Praeger , Westport , pp. 117 - 178 .

Talwar , S. , Dhir , A. , Kaur , P. and Mäntymäki , M. ( 2020 ), “ Why do people purchase from online travel agencies (OTAs)? A consumption values perspective ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 88 , 102534 .

Tew , P.J. , Lu , Z. , Tolomiczencko , G. and Gellatly , J. ( 2008 ), “ SARS: lessons in strategic planning for hoteliers and destination marketers ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 20 No. 3 , pp. 332 - 346 .

Volgger , M. , Taplin , R. and Aebli , A. ( 2021 ), “ Recovery of domestic tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic: an experimental comparison of interventions ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management , Vol. 48 , pp. 428 - 440 .

Waller , G. and Abbasian , S. ( 2022 ), “ An assessment of crisis management techniques in hotels in London and Stockholm as response to COVID-19's economic impact ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 34 No. 6 , pp. 2134 - 2153 .

Wang , F. and Lopez , C. ( 2020 ), “ Does communicating safety matter? ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 80 , 102805 .

Wang , F. , Xue , T. , Wang , T. and Wu , B. ( 2020 ), “ The mechanism of tourism risk perception in severe epidemic—the antecedent effect of place image depicted in anti-epidemic music videos and the moderating effect of visiting history ”, Sustainability , Vol. 12 No. 13 , 5454 .

Wut , T.M. , Xu , J.B. and Wong , S.M. ( 2021 ), “ Crisis management research (1985-2020) in the hospitality and tourism industry: a review and research agenda ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 85 , 104307 .

Xue , J. , Mo , Z. , Liu , M.T. and Gao , M. ( 2021 ), “ How does leader conscientiousness influence frontline staff under conditions of serious anxiety? An empirical study from integrated resorts (IRs) ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights , Vol. 6 No. 1 , pp. 90 - 109 .

Yang , S. , Jiang , H. , Yao , J. , Chen , Y. and Wei , J. ( 2018 ), “ Perceived values on mobile GMS continuance: a perspective from perceived integration and interactivity ”, Computers in Human Behavior , Vol. 89 , pp. 16 - 26 .

Yuan , K.H. and Hayashi , H.K. ( 2003 ), “ Bootstrap approach to inference and power analysis based on three statistics for covariance structure models ”, British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology , Vol. 56 No. 1 , pp. 161 - 175 .

Zeithaml , V.A. ( 1988 ), “ Percepciones del consumidor sobre el precio, la calidad y el valor: un modelo de medios y fines y síntesis de la evidencia ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 52 No. 3 , pp. 2 - 22 .

Zenker , S. and Kock , F. ( 2020 ), “ The coronavirus pandemic – a critical discussion of a tourism research agenda ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 81 , 104164 .

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the por la Consejería de Universidad, Investigación e Innovación de la Junta de Andalucía y por FEDER, Una manera de Hacer Europa (Research Project A-SEJ-462-UGR20).

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Skift Research

- Airline Weekly

- Skift Meetings

- Daily Lodging Report

Online Travel Booking Trends During the Pandemic

Executive summary, overall booking trends, online booking site share shifts, u.s. online travel share in airlines and hotels, u.s. traveler planning habits, related reports.

- The Past, Present, and Future of Online Travel March 2024

- Outbound Travel 2024: Asia’s Big Year, Europe’s Slowdown February 2024

- Will Hotel Pricing Strength Continue into 2024? January 2024

- Skift Research Global Travel Outlook 2024 January 2024

Report Overview

This report looks at how online travel booking habits changed during the pandemic and how these behaviors will continue to evolve. Since February 2020, Skift has been regularly surveying 1,000+ Americans about their travel behaviors first on a monthly, and then a bi-monthly basis. The topline results of these surveys are published as our U.S. Travel Tracker . However, we ask more granular travel questions that have not been published previously.

This report teases out specific insights around which channels Americans use to book their hotels and flights. With this data we can see how direct bookings changed during the pandemic and whether it has reverted to pre-crisis trends. We can also look at specific booking site market share shifts and investigate whether the trip planning process shifted.

What You'll Learn From This Report

- How did the pandemic impact direct bookings and are these trends still in place?

- How has online travel agency market share shifted since 2020 in the U.S.?

- Did the pandemic change Americans’ trip planning process?

Using new data from our survey of American travelers we find that online travel booking trends are in flux. The early pandemic drove a wave of direct bookings, likely spurred by safety fears, customer service concerns around cancellations, and a lack of trust that third-parties could provide up-to-the minute in-destination information.

However, we see mounting evidence that these first-party gains may not be durable. As financial concerns loom larger over trust and safety, our surveys show more shoppers reverting to third-party bookings, likely as they seek out discounts and comparison shopping to find the best value.

Our survey data also hints at changes in the U.S. online travel agency landscape. Expedia Group’s multi-brand strategy makes it the largest family of booking sites in the U.S. by a wide margin. But their dominance is being challenged by aggressive investment from Booking.com and new challenger brands like Hopper.com and HotelTonight.

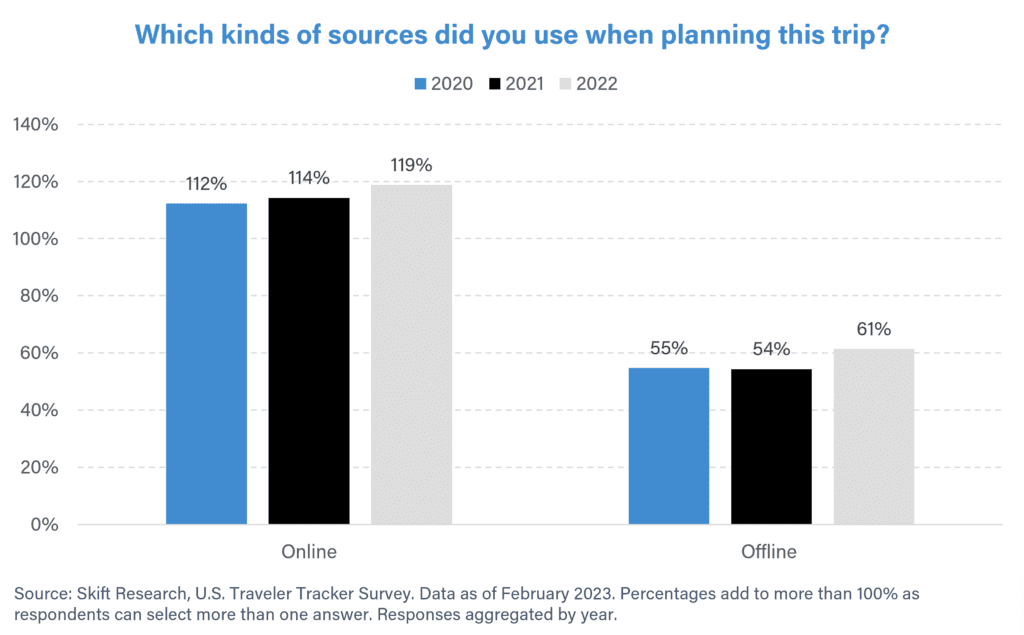

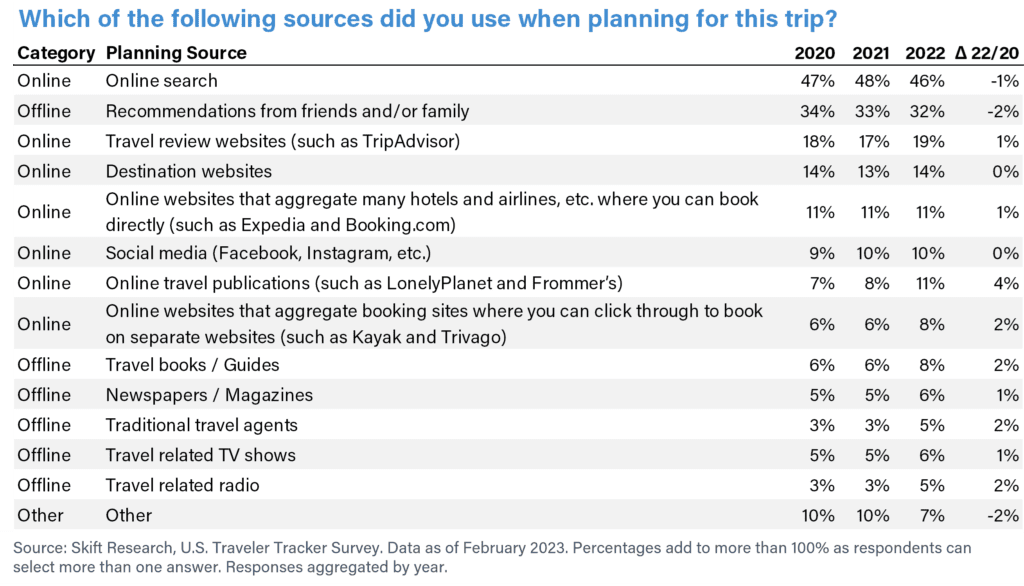

Despite the many shifts happening in online travel bookings, we see little evidence that the online travel planning toolset changed much. Online search and word of mouth recommendations remain the most important sources of travel planning (but not inspiration!) by far. This has been the case for the last three years since 2020 and throughout the pandemic.

Let’s start with the big picture. Skift Research asked U.S. travelers which channels they used to book their hotels and flights. We tagged all channels as either direct or third-party and then aggregated activity across both hotel and flight bookings.

This gives us our broadest look into how travel direct booking has been trending. We find it is on the decline after a peak early on in the pandemic, although more than half of all transactions still come direct.

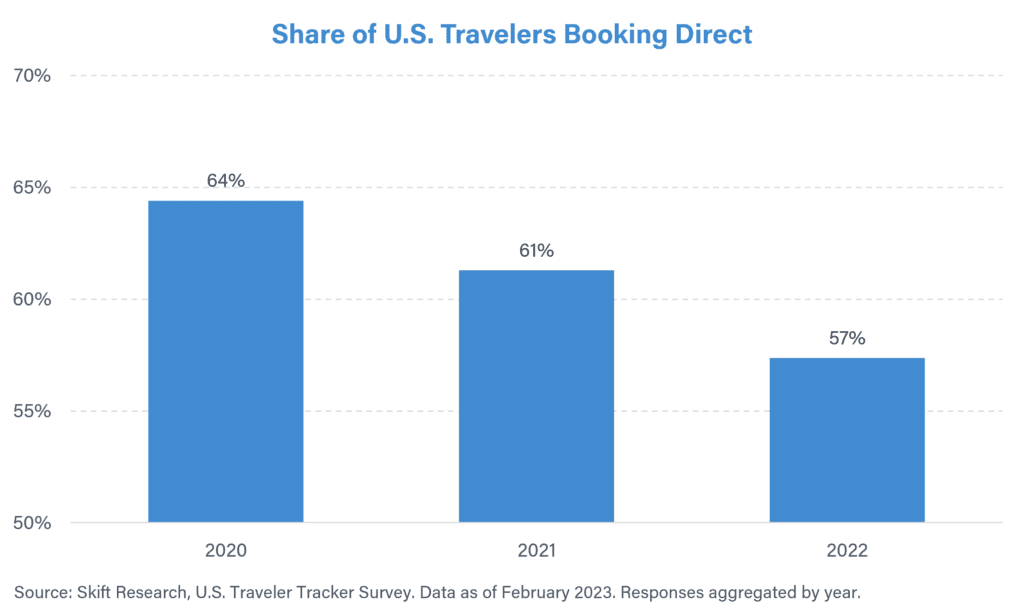

According to our survey results, 64% of U.S. flight and hotel bookings came direct in 2020.. This fell to 61% in 2021 and to 57% in 2022.

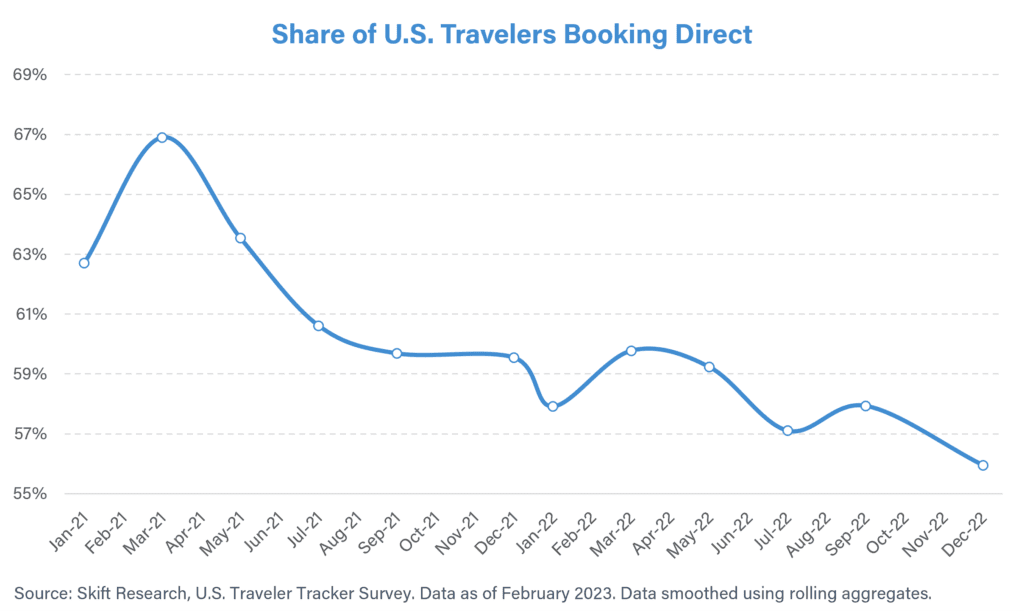

We can rechart this to examine how the trend evolved over time. We exclude 2020 data here as it was too volatile at the monthly level with such limited travel activity taking place. What we see in the time series is that direct bookings peaked in early 2021 and quickly fell off into summer and fall 2021.

We suspect that it is no coincidence that this quick fall-off in direct bookings coincides with the rapid return of mass travel in the U.S. as vaccines became widely available and international locations began to re-open.

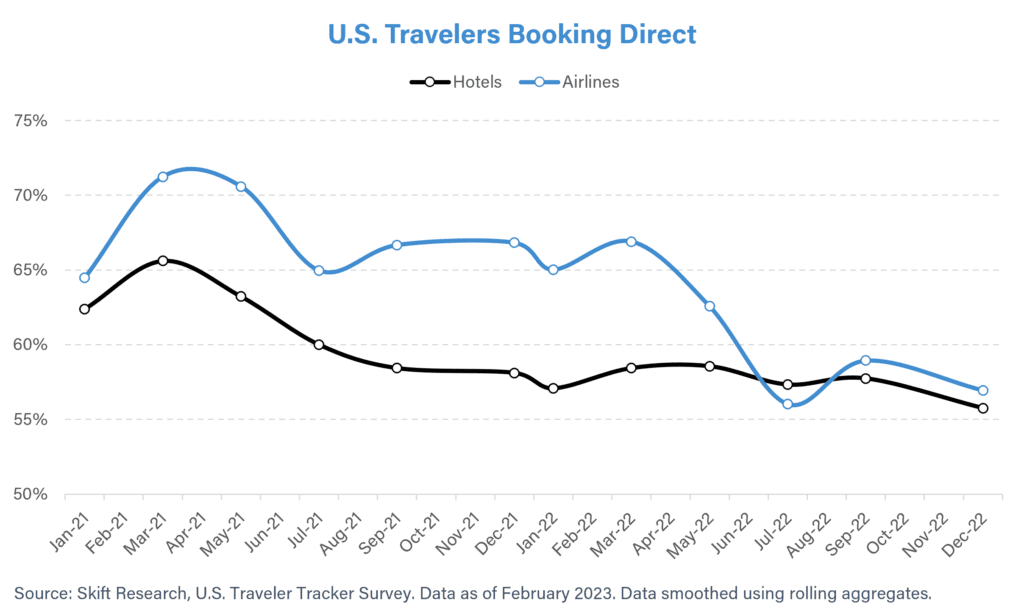

Let’s split this aggregate data into its two component travel products: Airlines and Hotels. Individually the broad direction of the trend is the same and since the summer of 2022, both hotels and airlines have been operating at parity in terms of direct booking share. However, Airlines fell farther, coming from a high of 70%+ direct bookings down to 57%, today.

Our best guess for this divergence is flight vouchers issued in the wake of mass cancellations in 2020. Online booking sites struggled to handle these future flight credits and we suspect most consumers rebooked directly. This would explain why Airline direct bookings remained elevated throughout all of 2021 even as Hotels fell. It would also neatly fit with the rapid decline of airline direct bookings in Summer 2022 as that is around the same time we began anecdotally hearing that consumers had used up many of their outstanding travel credits.

After a mostly stable 2022, in both hotels and airlines, we see a small dip in the most recent reading from December 2022. It is still too early to tell if this is the start of another, larger, leg down or just a blip. But overall, what we see is a strong decline in direct bookings as we get further out from the heart of the pandemic.

This is consistent with our ongoing thesis around online travel built on the core that the pandemic was a crisis of trust and not of finances. We believe that consumers have higher confidence in both the travel product and the customer experience they will receive when they book direct. This is even more so in the case of booking branded travel experiences. But staying within a brand ecosystem limits the consumers’ ability to shop around for deals. Comparison shopping is the strong suit of the online booking platforms while their ability to control the end product experience and to resolve customer service issues is limited by their nature as third parties.

Skift Research believes that online travel booking sites stumbled in the early phases of the recovery because consumers didn’t trust that these brands could deliver on the very specific and safety-conscious experiences they were seeking. Consumers were also skeptical of third parties’ ability to provide real-time updates as to what amenities and activities were available in both properties and destinations. Plus, consumers were flush with savings from the pandemic and held branded travel vouchers.

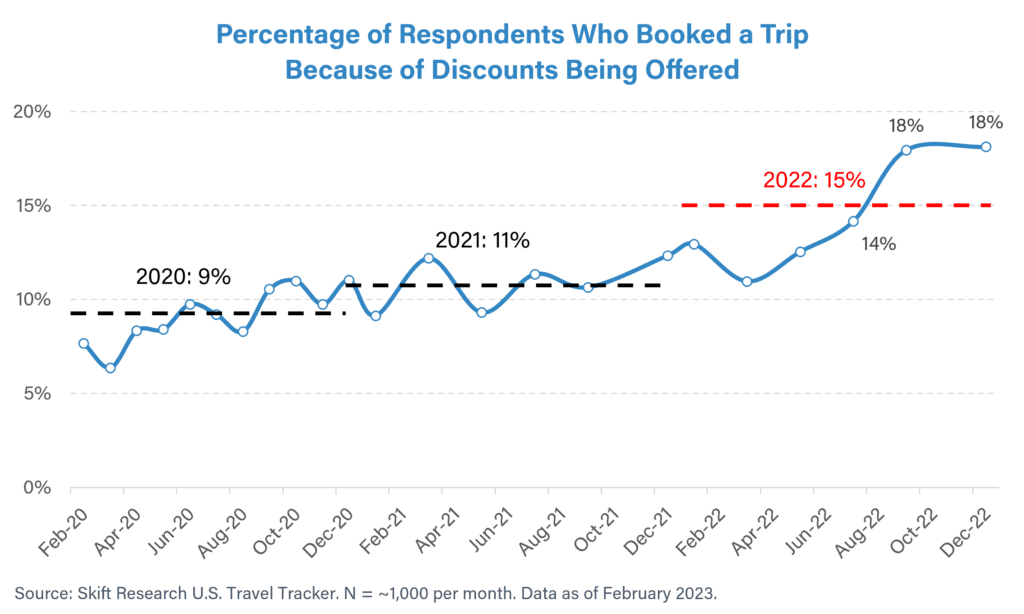

All of this drove a strong direct booking push that benefited travel supplier brands. To wit, in 2020, just 9% of American travelers told Skift that they had booked a trip because of discounts being offered. Trust and safety far outweighed financial concerns. That share of travelers remained mostly unchanged in 2021, rising to 11% of travelers incentivized by discounts.

However, our last two surveys, conducted in October and December of 2022, mark a potentially significant shift in this trend. Most recently, 18% of respondents told us that discounts proved effective in driving their travel booking decision in December 2022, a six point share shift versus December 2021.

When paired with the broad lifting of COVID restrictions, rising prices due to inflation, and growing recessionary fears, we think the stage is set for a change in sentiment among the U.S. traveling public. We may be moving from a regime where trust and safety are the top priority to one where price is king. If not yet broad based, we suspect this change is rapidly taking place in certain demographics, especially in the more midscale and economy chain scales.

Let’s focus in on inflation which we think is rapidly supplanting COVID-19 as the top concern impacting travel for the American public. The below chart shows how lodging and airfare prices have increased relative to 2019. While this is not the traditional way an economist would display inflation, we think that benchmarking the numbers against 2019 helps visualize the gut reactions that many consumers feel when looking to book travel today and comparing it in their minds eye against their last pre-COVID trip.

As of January 2023, lodging prices were up 15% relative to the same period in 2019. Air fares were 6% higher, though note the summer spike when tickets were briefly 27% pricier than the same time in 2019. Broad U.S. inflation along the same methodology was actually 16% above 2019 levels. This means that in inflation adjusted terms, both hotels and airlines are still cheaper relative to 2019. But consumers struggle to think in real (inflation adjusted) price terms and instead see nominal price changes. Plus, broad inflation hurts the wallet just as well. When groceries and fuel prices go up, consumers have less to spend on travel, even if they can recognize that hotel price increases have lagged broader price changes.

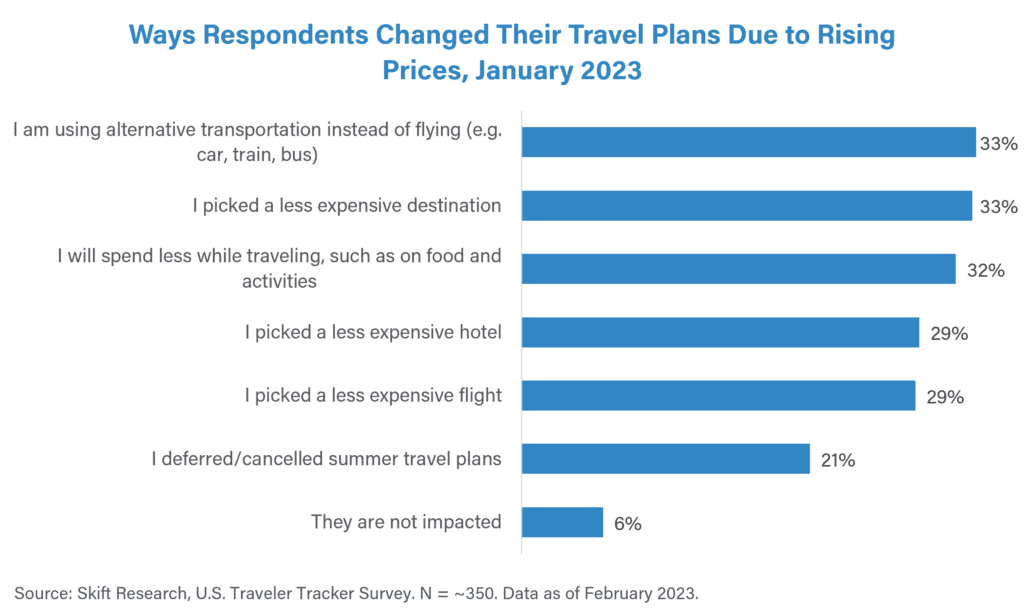

Our travel tracker survey says that inflation is already impacting traveler decisions. A majority of respondents told us that they had altered their travel plans due to rising prices. The most common decisions made were to take an alternative form of transport rather than flying and to pick a less expensive destination. We also saw nearly a third of respondents indicated that they had shopped around to pick a less expensive flight or hotel.

This ties directly into our thesis on brand value growing in importance relative to brand trust. We see evidence that discounts are becoming more effective and we suspect hotels and airlines alike will increasingly need to compete on price. This would undermine the current situation where brands have held the line on pricing power and much revenue growth is being driven by rising yields. It would also play straight into the hands of the online travel agencies which excel at comparison shopping and are strongly associated with value pricing.

Even if an individual brand is not discounting, online travel agencies help consumers find properties within a market that are offering below market rates or else help them discover well-reviewed ‘trade-downs’ into lower price scales in the same market.

This narrative is consistent with the direct booking data that we are receiving from our travel tracking survey. If correct, it suggests that the high direct booking rates may have been a pandemic-only event and that we are on track to return to a more competitive mix of channel booking shares. Ultimately, we see this as a positive tailwind for online travel agencies.

With the trend shifting in favor of third-party bookings, let’s examine what specific booking sites American travelers told Skift they used.

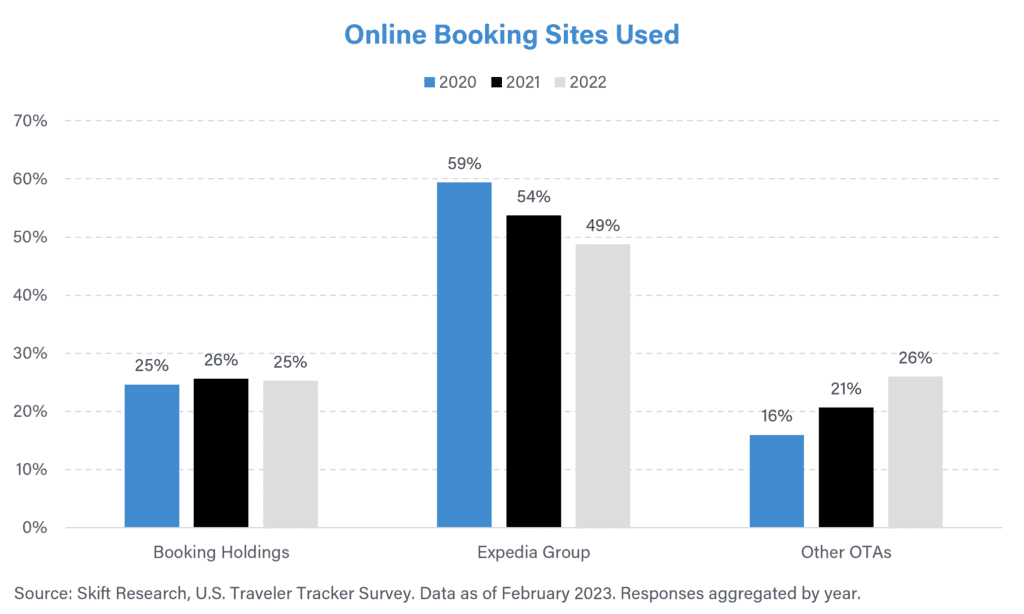

We asked travelers to tell us if they booked either their flights or hotels via one of 16 specific online travel sites. Of these, three brands were owned by Booking Holdings (Booking.com, Priceline, and Agoda) while six were owned by Expedia Group (Expedia.com, Hotels.com, Orbitz, Hotwire, Travelocity, and Cheaptickets.com). Alternative accommodations were not included in these survey questions and so Airbnb and Vrbo.com are excluded from our data. Bear in mind that, as sample sizes in our survey get smaller at this granular level, these results likely don’t represent true market shares. But we believe this is still useful data to help us understand the order of magnitude of differences across brands and how trends in their relative positions are changing.

What we find is that Expedia Group is overwhelmingly the most popular family of booking sites used in the United States. In 2022, our survey suggested that 49% of airline or hotel bookings made on OTAs were done via one of the Expedia Groups’ brands. That is nearly double the share of its rival competitor, Booking Holdings.

But it is not all smooth sailing for Expedia Group. Although it remains the largest family of brands in the U.S., our data suggests a worrying trend that these sites are ceding market share. In our data, Expedia Group websites saw a ten point share decline, falling from 59% of OTA bookings in 2020 to 49% in 2022.

Looking at individual websites and brands rather than at the parent company level gives us a bit more insight into the puts and takes of what is happening here. However, we again caution that as sample sizes get thin here, this data can be helpful in drawing an informed thesis about what is happening in the market, but it is not a conclusive market share.

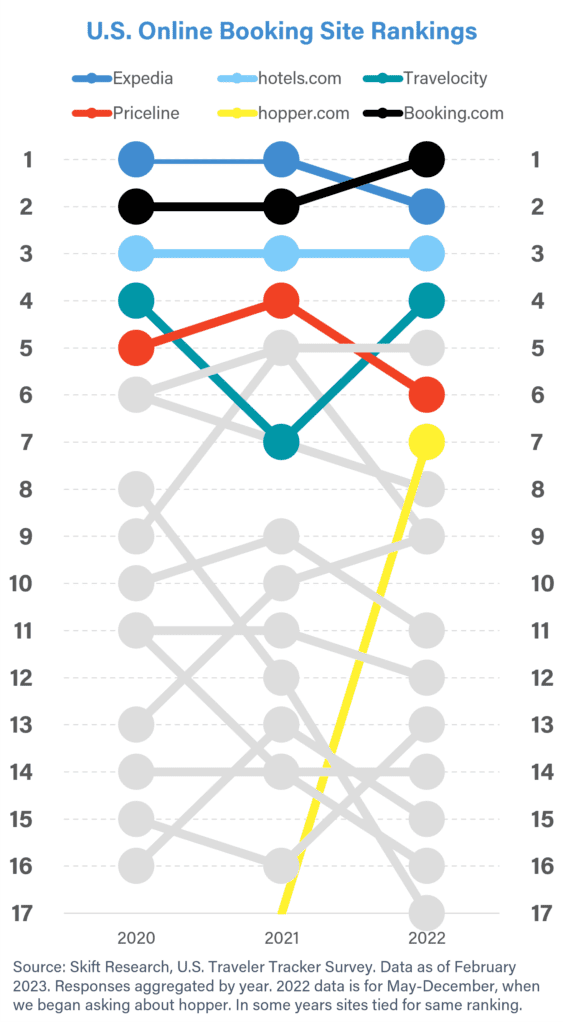

We asked respondents to tell us what site they used when booking a flight or hotel. This data was then aggregated by year, and each site was ranked. This lets us come to a more nuanced conclusion about how consumer usage of OTA brands is evolving.

Right off the bat, the most shocking result is that, in our survey data, Booking.com surpassed Expedia.com as the most used booking site in the U.S. in 2022. Expedia.com had been number one in 2020 and 2021 with Booking.com in second place.

We should note here that this finding does not tie out with web traffic data from SimilarWeb that ranks Expedia.com above Booking.com. But then again, SimilarWeb only measures web traffic and not actual bookings. It is possible that Booking.com has a better conversion rate of lookers to bookers as compared to Expedia.com.

Nonetheless, we think it is unlikely that Booking.com truly overtook Expedia.com in 2022 in the U.S. But we do think that this data captures a very real surge in momentum that Booking.com experienced in North America because of its increased strategic focus on this region. Also, it seems that Booking.com’s U.S. push cannibalized bookings from Priceline. Priceline fell from a fourth place ranking in 2021 to sixth in 2022. This explains why market share at the parent company level for Booking Holdings didn’t budge last year.

It also emphasizes the importance of Expedia Groups multi-brand strategy. Expedia.com goes toe-to-toe with booking.com and both have similar usage amongst our survey respondents. But Booking Holdings has a weaker bench, and traction for Priceline and Agoda is slim. Expedia Group, on the other hand, owned four out of the five top brands in the U.S. in our survey. This is how the parent company has such greater U.S. share in aggregate than its European rival.

This also explains why Expedia Group has been so reluctant to abandon its multi-brand strategy . It has good reason to fear that it could lose market share by shutting down its smaller brands. But despite these valid concerns, a multi-brand strategy may face challenges in a future where Google continues to grow at the expense of other metasearch sites and where travel supplier brands consolidate and push direct loyalty.

If Booking Holdings kept its overall share the same, then who stole Expedia Group’s market share since 2020? Our survey suggests a number of emerging competitors that are growing in the U.S. Each is small individually but add up to a notable market share shift in aggregate. Independent Lastminute.com and Airbnb-owned HotelTonight both have climbed our rankings since 2020. But the most dramatic was Hopper.com.