A primer for Italian renaissance art

Raphael, School of Athens , fresco, 1509–11 (Stanza della Segnatura, Papal Palace, Vatican; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Why study Italian renaissance art?

Even if you are not a student of art history, you are likely familiar with the names Donatello , Leonardo da Vinci , Raffaello Sanzio (Raphael) , and Michelangelo Buonarotti . There is a reason these names continue to be part of our contemporary popular culture (and it’s not just because these are the names of everyone’s favorite martial arts mutant Turtles). These artists were central to what we today call the Renaissance — a period in European history (c. 1400–1600) when some of our current ideas about society, politics, and art took form.

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between Navigating the art of the past requires a different set of tools than those required for understanding art produced in our contemporary world. This introduction will orient you to some important, basic information as you begin to study Italian renaissance art. Within each section below you will find links to essays and videos that flesh out the themes introduced.

Michelangelo’s famous nudes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling borrow from ancient Roman art forms, such as the so-called Belvedere torso. Left: Apollonios, Belvedere Torso , a copy from the 1st century B.C.E. or C.E. of an earlier sculpture from the first half of the 2nd century B.C.E., marble, 159 cm (Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Michelangelo, Ignudo (detail), ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Vatican City, Rome, 1508–12, fresco

The term “renaissance” is often used to designate a rebirth of interest in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds (often referred to as “classical antiquity”) that arose in Europe in the later Middle Ages .

While engagement with the Greco-Roman past was not new, it took on a new urgency in Italy beginning in the 14th century and was eventually felt throughout the European continent. This interest prompted new intellectual investigations (learn about humanism ) that had a profound influence on European culture, affecting all realms of life including the visual arts.

Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ piu eccellenti pittori scultori e architettori (Florence, 1568) ( National Gallery of Art , Washington, D.C.)

Many of the artistic traditions originating or maturing in this context informed the direction of European art for the next several centuries. Linear perspective , volumetric figures rendered with anatomical precision, emotionally charged expression, and visual naturalism are formal elements popularized in the Renaissance. This was especially true of art in Italy where ancient Roman art demonstrating many of these traits was abundant (such as Roman relief sculpture and architecture ).

This was also the period when artistic theory and the European discipline of art history began to develop . Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise, On Painting (1435/36) , was the first theoretical text written on visual art in Europe and Giorgio Vasari ’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550, 2nd edition 1568) was the first critical history of European art. Many of the ideas originating in the writings of these men and their contemporaries are still fundamental to artistic theory and practice today. In fact, Vasari’s categories of artists, including his privileging of Florentines, and standards for evaluation of their work have dominated the discipline. For several centuries after his text’s publication, the artists and visual approaches that he celebrated were seen as the “gold standard” in art, the foundation for what we call the European canon . Contemporary scholars striving for a more inclusive art history have worked to unpack and complicate Vasari’s ideas. His construction of the artist as a born genius, for example, an idea epitomized in his life of Michelangelo, has been repeatedly challenged in feminist scholarship. Privileges of sex, race, and social status enabled the artistic success that Vasari presented as inevitable.

Who?

To understand the art of the Italian renaissance, we need to consider the values, social mores, and the religious and political interests of the people who made, paid for, and first looked at the art. Unfortunately, our knowledge of these people is limited and skewed. History is most often written by those in positions of privilege and power who generally leave behind the most evidence of their lives and ideas. This means that we have quite a bit of information about some people—primarily Christian men who were wealthy merchants, educated elites, or members of the Church—and little to none from other social groups, including most women, the peasantry, non-Christians, and non-Europeans.

Raphael’s serene and pensive sitter is a far cry from the reality of the man depicted: the fiery Warrior Pope, Julius II. Even Raphael, the artistic darling of early 16th-century Rome, was far removed from his powerful patron’s exalted status. Raphael, Portrait of Pope Julius II , 1511, oil on poplar, 108.7 x 81 cm (National Gallery, London; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

With few exceptions, artists did not enjoy the status of intellectuals or social elites. Because they made things by hand that they then sold for profit, they were deemed of lower social stature than the wealthy merchants and aristocrats who bought their work. Art making was traditionally seen as a Mechanical , and not a Liberal Art (art of the mind). While the status of the artist did improve over the course of the Renaissance—thanks in part to our Ninja Turtles’ namesakes—it was a slow and uneven process. Most artists came from what we might call urban, middle-class roots and trained for a long period in a workshop , learning their craft rather than receiving the kind of Liberal Arts education available to members of the upper classes. Even though art theorists like Alberti argued for an artist’s education in a range of subjects including philosophy (which included “natural philosophy” or science ), poetry, mathematics, medicine , and geometry (to name just a few), access to this education was limited. This changed somewhat in the 16th century with the rise of the first art academies , although the extent to which an artist could receive the kind of extensive education deemed ideal was still limited. Such advanced training was reserved for the sons of the elite. Even Leonardo da Vinci, the so-called universal genius (perhaps one of the few figures in history to whom that problematic title may justly be applied), was outside the world of highest learning, never having mastered Latin.

Despite the challenges facing Italian artists in participating directly in renaissance intellectual culture, many fought vigorously to elevate the status of their profession and their own corresponding social standing. Some artists, like Leonardo, sought to elevate visual art by drawing comparisons to philosophy or poetry. As he noted:

Painting is mute poetry and poetry is blind painting.

Leonardo da Vinci, Paragone [2] They argued that despite making objects by hand, the renaissance artist’s practice was guided first by the intellect—like a poet or a philosopher. Such arguments were modeled on the writings of ancient Roman authors like Pliny , Lucian , and Cicero , another example of humanism at work.

As humanist-inspired tastes in art developed over the course of the early renaissance, so too did requirements for artists’ skills. Art making became increasingly professionalized. To develop the mathematically defined spaces populated by anatomically correct figures enacting complex narrative scenes from religious and classical history that were in vogue, artists needed to study geometry and anatomy. They had to read ancient texts in translation and consult with learned advisors, develop sophisticated preparatory studies, and negotiate business contracts. They also needed to navigate complex social relationships requiring savvy interpersonal skills.

As in most occupations at the time, it was not only social class, but also gender that determined artistic identity: artists were almost entirely men and art making was thought to be a male prerogative. The professionalization of artistic practice that helped raise the social status of art making had the negative effect of excluding women who, particularly in mercantile cities like Florence, were increasingly regulated to the domestic sphere. Although some female artists did achieve renown (such as Sofonisba Anguissola ), their numbers were few until well into the 17th century.

This dazzling altarpiece reflected the magnificence of its patron, Palla Strozzi, the wealthiest man in Florence at the time of its creation. Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi , 1423, tempera on panel, 283 x 300 cm (Galeria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

You have likely run across the name Michelangelo , but are perhaps less familiar with his great patron, Pope Julius II . This tells us more about our present-day fascination with artists than it does about the realities of the renaissance past. In this world, the patrons—the people who paid for (commissioned) the art work—were more socially privileged than the artists who worked for them and received much of the credit for the artwork they sponsored. Again, men were the primary patrons although some women in positions of special privilege like Isabella d’Este (marchioness of Mantua, a small but glamorous principality in northern Italy) commissioned art as well. There were many reasons for commissioning art . Art could advertise an individual’s learning and taste, wealth, and position, and even political loyalties and religious faith. Patronage ranged across media and genres and was commissioned for a variety of contexts including public piazzas, private homes and palaces, private chapels and tombs in public churches, and other sacred spaces.

Giovanni Bellini, San Zaccaria Altarpiece , 1505, oil on wood transferred to canvas, 16 feet 5–1/2 inches x 7 feet 9 inches (San Zaccaria, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

What?

I have repeatedly used the word “art” so far in this essay. To us, the paintings, sculptures, buildings, tapestries, prints, and other aesthetic objects created during this time are considered “art,” but this was not the case for people living during the Renaissance. The objects and images that we study as renaissance art were understood to be functional aspects of visual culture. The primary goal was not aesthetic appreciation or art for the sake of art, which is a category of experience that is a 19th-century invention. An altarpiece that may be viewed in an art museum today originally functioned as an object of devotion; it would have been the centerpiece of Christian religious practice in a sacred setting and was first and foremost a didactic tool guiding Christians in their worship. A portrait was a form of commemoration, a way to manifest a sitter’s presence when absent or to communicate family connections . Scenes drawn from ancient poetry or heroic tales were methods of communicating virtue, demonstrating erudition, and encouraging learned discourse. Were these images and objects appreciated as aesthetically interesting, even “beautiful”? Absolutely. But it’s important to note that this was not the primary goal.

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus , 1483–85, tempera on panel, 172.5 x 278.5 cm (Galeria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In renaissance art you will confront two main categories of iconography , or subject matter: secular (non-religious) and religious. Both types fulfilled different functions, but they also sometimes overlapped. Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus , for example, exemplifies secular iconography and borrows from ancient tradition. At the same time, Venus was associated with ideas about divine love circulating in late 15th century Neoplatonic philosophy , which (among other things) sought to reconcile ancient philosophy with Christianity.

Donatello, David , c. 1440, bronze, 158 cm (Museo Nazionale de Bargello, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

We also have two main categories of audience: public and private, which also often overlapped. Donatello’s bronze David was both a private artwork, placed within the powerful Medici family’s palace courtyard, and a public statement of their power, wealth, and faith — the work was visible from the street.

The Gathering of Manna , 1595–96 (Florence), designed by Alessandro Allori, Woven in Medici workshop under the direction of Guasparri di Bartolomeo Papini, wool and silk, 426.7 x 447 cm ( The Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York)

It is also helpful to be conscious of how the present-day media hierarchy is skewed to our own interests. While we tend to prioritize the arts of painting , sculpture , and architecture, what was valued in the past was different from what we emphasize in our current patterns of collection and display. Tapestries, for example, are not often on view in museums in significant numbers nor are they foregrounded in histories of art, in part because of the fragile nature of their medium (silk and wool thread does not survive the ravages of time as well as marble or brick), but also because the art form went out of style in the modern era. During the Renaissance, however, tapestries were one of the most prized forms of visual art. These spectacular creations were amongst the most sought after and costly objects, adorning the walls of palaces, churches, and government buildings across Europe. When learning about renaissance art you will encounter painting, large-scale sculpture, and architecture, but it’s important to note that this visual world also included—and sometimes more importantly—tapestries, vestments , liturgical objects , small-scale sculptures, prints , ceramics , embroidery , and other works. Our modern interests have shaped what we consider to be “great” art, or what is even considered worthy of study. These biases towards certain media, genres, and artists are our own—or those that we have been taught—not necessarily those of people throughout history, and it is helpful to be conscious of the distorted views of the past that they can sometimes create. Recent scholarship has worked to be more inclusive, increasingly exploring visual production in various media and broadening our definitions of just what constitutes “art.”

When trying to delineate the period known as the “renaissance” scholars generally designate the years 1400–1600 . I say “generally” because life doesn’t unfold in tidy demarcated centuries. Starting points are hard to determine. Developments in art and culture in the 1400s come out of those in the preceding centuries, including historical crises like the Black Death . Many surveys of so-called renaissance art, for example, start with the innovative creations of Giotto di Bondone who lived c. 1267–1337, which is often called the Late Middle Ages by us today. Would we have Beyonce without Aretha Franklin? The operas of Lin Manuel Miranda without Mozart? Similarly, why end at 1600? In a certain sense, all such delineations are arbitrary (did 5th-century Romans know that Rome fell?). We go by broad patterns and general trends. The European political, social, and religious landscape changed dramatically in the last few decades of the 16th century, due in no small part to the rise of Protestantism , and art changed with it making this a viable, if imperfect, end point.

From Petrarch , renaissance Italians inherited the notion of three distinct ages of man: what he saw as the glorious ancient past, the “dark ages” after the decline of the Roman empire, and his own modern age where the glories of antiquity were reborn. While this periodization of history is deeply problematic—we no longer recognize the period after the decline of Rome as a “dark age”—we still borrow this general framework, using terms like “antiquity,” the “middle ages,” and “the renaissance.” The following general—and admittedly imperfect—breakdown of historical periods is what most people mean when they designate these eras:

- 600 B.C.E.–400 C.E. Ancient Greece and Rome (also known as the classical past or classical antiquity, this 1,000 year span of time is itself broken by historians and art historians into smaller designations, such as archaic, high classical, hellenistic, etc.)

- 400–c. 1400 the Middle Ages (c. 1200–1400 is often called the Late Middle Ages)

- 1400–1600 the Renaissance

Map of Italy in 1494 (underlying map © Google)

Italian renaissance art was made in Italy, right? Well, sort of. It was made on the peninsula in southern Europe that we call Italy today. But it wasn’t “Italy” then. The country was not united as we know it until the 19th century. During the renaissance, the Italian peninsula was organized into independent city-states with distinct political and social formations as well as unique dialects and cultural traditions. Some states, like Florence , Venice , and Genoa, functioned as republics where members of the urban elite governed by election. Others, like Milan, Ferrara, and Urbino, were governed by a sovereign, a ruler who had almost absolute hereditary authority. These Signorie or Lordships were usually under the leadership of a Marquis or a Duke and technically owed their allegiance to a superior political power—some were granted authority by the Holy Roman Emperor, some from the Church. In practice, however, these ruling princes (a catch-all term used throughout the Renaissance to designate a ruler), enjoyed virtual independence. There was also a massive swath of central Italy that came under the direct rule of the Catholic Church—led by the Pope —a region known as the Papal States. The southernmost part of the peninsula was divided into the Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily which were ruled by a series of dynasties throughout the Middle Ages until finally unified under a single king (ranking just below an Emperor), in the 15th century by the Spanish House of Aragon. Throughout the renaissance period, Spanish and French royal families vied for power in this territory. While we may discuss “Italian renaissance” art broadly, and there were certainly shared religious and social values as well as a shared ancestry with the ancient Roman past across the peninsula, it is important to understand that this was not a unified state in our modern sense. In fact, these various territories were often at war with one another.

Some of the territories of the Republic of Venice c. 1500 (underlying map © Google)

Gentile Bellini, Portrait of Sultan Mehmet II , 1480, oil on canvas, 69.9 x 52.1 cm ( National Gallery , London)

T his was a permeable and highly international world. Contacts with different peoples and cultures were common. This was an age of international trade (including the slave trade), exploration, rising colonial enterprises, and war, all of which required deft diplomacy. Venice, for example, was a maritime trading power that held vast territories in the north Italian mainland and throughout the Mediterranean world, and as a result had large populations of foreigners. Greek influence was particularly strong there due to the city’s colonies in Crete, Cyprus, and Rhodes, and became more so with the influx of Greek immigrants to the region after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453. Italian artists traveled throughout the Italian peninsula working for different patrons and in variable contexts; as they moved about so too did the various indigenous visual traditions in which they were trained.

Artists also went beyond Italy, finding work in the urban centers and courts of other European states and beyond. The painter Gentile Bellini spent fifteen months at the court of the Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed II as representative of the Venetian Republic. Likewise, artists from other parts of the world came to Italy. Some, like Albrecht Dürer and Alonso Berruguete , helped transform art across the continent by introducing new approaches that fused Italian traditions with those developing elsewhere. Other Italian artists even relocated to the Americas or Asia, such as those associated with the Jesuit missionary order.

But still, why do renaissance art history surveys so often start here in this region that wasn’t Italy but we all call Italy? It was in this region that many of the developments that are understood to have informed the rise of something new—what we call a “renaissance”—first emerged. The Italian city- states were early to urbanize and enjoyed relative political and economic stability, key ingredients to the creation of vast amounts of art and architecture. That literary and visual forms emerge reflecting new “renaissance” styles in these states was also a direct function of the force of the visible presence of the ancient Roman past—in Italy Rome was everywhere, in texts preserved in monasteries and libraries of the Middle Ages, and in the copious remains of visual art and architecture.

[1] See for instance t he art historian Linda Nochlin’s canonical essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ARTNews , volume 69, number 9 (1971), pp. 22–39, 67–71.

[2] Quoted in André Chastel, The Genius of Leonardo da Vinci: Leonardo da Vinci on Art and the Artist , translated by Ellen Callmann (New York: Orion Press, 1961), p. 38. Leonardo was looking to Plutarch: “ Painting is mute poetry and poetry a speaking picture,” in Plutarch, Moralia (1819), p. 346.

Additional resources

Expanding the Renaissance: A Smarthistory initiative

Read a Reframing Art History textbook chapter, Art in the Italian Renaissance Republics, c. 1400–1600

Read a Reframing Art History textbook chapter, Art in Sovereign States of the Italian Renaissance, c. 1400–1600

Giorgio Vasari, The Father of Art History on Art UK

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

We've begun to update our look on video and essay pages!

Smarthistory's video and essay pages look a little different but still work the same way. We're in the process of updating our look in small ways to make Smarthistory's content easy to read and accessible on all devices. You can now also collapse the sidebar for focused watching and reading, then open it back up to navigate. We'll be making more improvements to the site over the next few months!

Module 8 Late Gothic_Renaissance Art

Module 8 renaissance art written assignment, written assignment the northern renaissance .

This is a research essay, about 350 words, more if you get going, Mr. S.

Readings about the early Renaissance https://courses.lumenlearning.com/masteryart1-91/

I want you to research one of the following two works of art by these influential artists connected to the Renaissance in Northern Europe.

- The first work is called the Ghent Altarpiece by Jan Van Eyck, a Flemish artist in the medieval Belgium city of Ghent.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eyck.hubert.lamb.750pix.jpg

This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less .

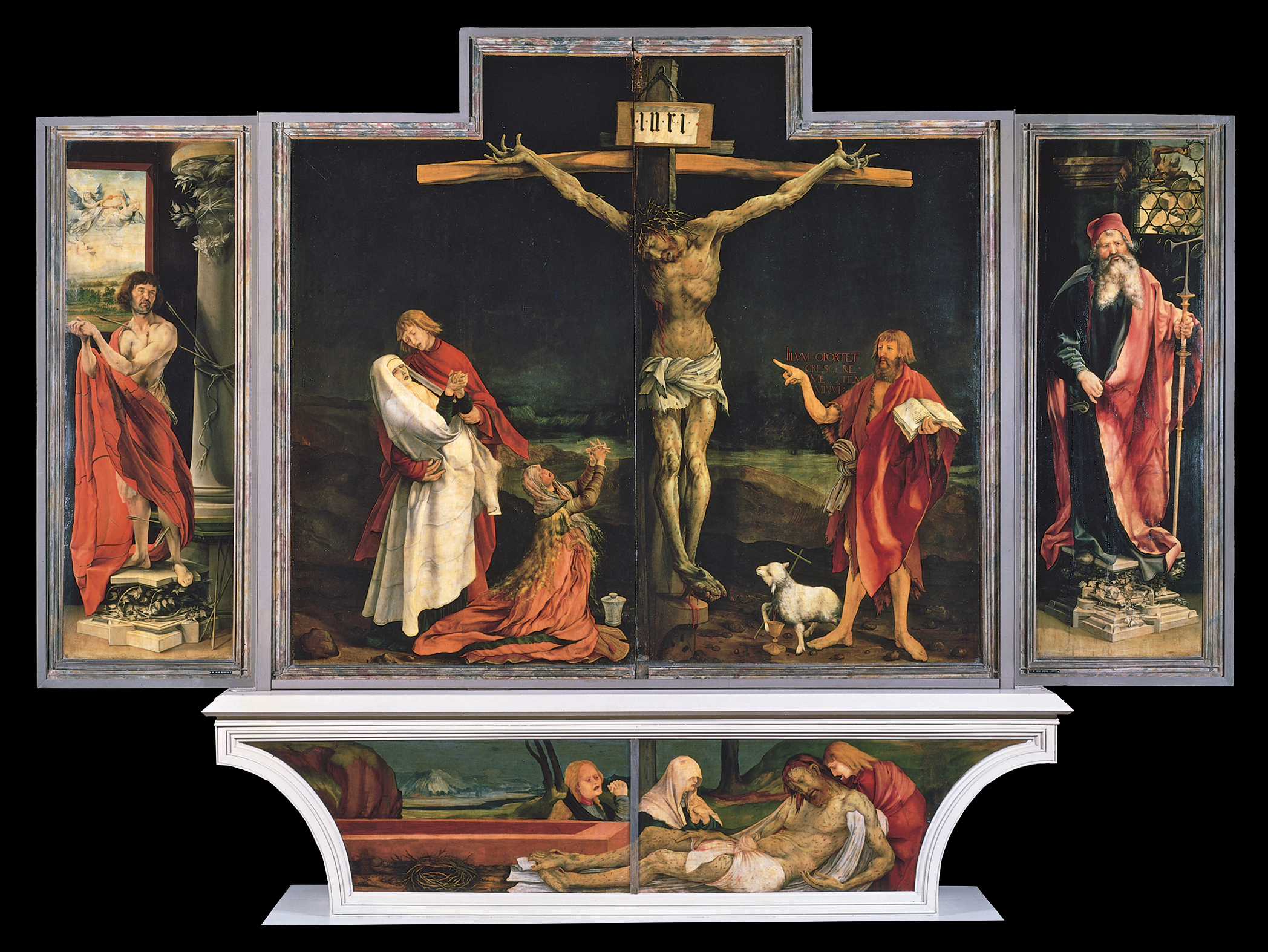

- Work two is the Isenheim Altarpiece by Mathias Grunewald, a Northern Renaissance artist in Germany.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grunewald_Isenheim1.jpg

This photographic reproduction is therefore also considered to be in the public domain in the United States.

Read everything in the text about one of these works , and the artist who created them. You should include a brief bio, and a brief description of the place in which they lived.

Research your chosen work on the web, you may start with the sites that I have included below, but you have to include a minimum of one more site that you find on your own.

Jan Van Eyck Ghent Altarpiece

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/northern-renaissance1/burgundy-netherlands/a/vaneyck-ghentaltar

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/northern-renaissance1/burgundy-netherlands/v/ghent-altarpiece-closed

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/northern-renaissance1/burgundy-netherlands/v/ghent-altar-open

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/renaissance-art-europe-ap/a/grnewald-isenheim-altarpiece

http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/Collection/artist-info.1362.html

BE SURE TO INCLUDE FOOTNOTES, AND A BIBLIOGRAPHY

See Course Information Doc. on Footnotes

- How does each artist portray his subject in a unique way?

- Describe each work, what do you see in the picture?

Is there anything that really catches your eye in the picture?

- What did you find out in your research?

- What in the picture identifies the country of origin?

i.e. is there anything in the picture that connects it to the place of origin?

- Module 8 Michelangelo and Giacometti. Authored by : Bruce Schwabach. Provided by : Herkimer College. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/masteryart1-91/chapter/module-8-michelangelo-and-giacometti-whats-due-when/ . Project : Achieving the Dream. License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Khan Academy Ghent Altarpiece. Authored by : Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker. Located at : https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/northern-renaissance1/burgundy-netherlands/a/vaneyck-ghentaltar . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

Section 19.4: Module 8 Renaissance Art Written Assignment

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 71903

Written Assignment The Northern Renaissance

This is a research essay, about 350 words, more if you get going, Mr. S.

Readings about the early Renaissance https://courses.lumenlearning.com/masteryart1-91/

I want you to research one of the following two works of art by these influential artists connected to the Renaissance in Northern Europe.

- The first work is called the Ghent Altarpiece by Jan Van Eyck, a Flemish artist in the medieval Belgium city of Ghent.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/F...amb.750pix.jpg

This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less .

- Work two is the Isenheim Altarpiece by Mathias Grunewald, a Northern Renaissance artist in Germany.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/F..._Isenheim1.jpg

This photographic reproduction is therefore also considered to be in the public domain in the United States.

Read everything in the text about one of these works , and the artist who created them. You should include a brief bio, and a brief description of the place in which they lived.

Research your chosen work on the web, you may start with the sites that I have included below, but you have to include a minimum of one more site that you find on your own.

Jan Van Eyck Ghent Altarpiece

https://www.khanacademy.org/humaniti...yck-ghentaltar

https://www.khanacademy.org/humaniti...arpiece-closed

https://www.khanacademy.org/humaniti...ent-altar-open

https://www.khanacademy.org/humaniti...eim-altarpiece

http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/Co...info.1362.html

BE SURE TO INCLUDE FOOTNOTES, AND A BIBLIOGRAPHY

See Course Information Doc. on Footnotes

- How does each artist portray his subject in a unique way?

- Describe each work, what do you see in the picture?

Is there anything that really catches your eye in the picture?

- What did you find out in your research?

- What in the picture identifies the country of origin?

i.e. is there anything in the picture that connects it to the place of origin?

- Module 8 Michelangelo and Giacometti. Authored by : Bruce Schwabach. Provided by : Herkimer College. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/masteryart1-91/chapter/module-8-michelangelo-and-giacometti-whats-due-when/ . Project : Achieving the Dream. License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Khan Academy Ghent Altarpiece. Authored by : Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker. Located at : https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/northern-renaissance1/burgundy-netherlands/a/vaneyck-ghentaltar . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Engaging History Lessons - Interactive Quizzes - Free Downloads

Mr. Dowling

Renaissance

Renaissance teaching resources, share this story, choose your platform, related posts.

Ferdinand Magellan

Europeans Explore the World

Niccolo Machiavelli

The Renaissance Spreads

© 2024 • Mike Dowling • All Rights Reserved.

- Survey 1: Prehistory to Gothic

- Survey 2: Renaissance to Modern & Contemporary

- Thematic Lesson Plans

- AP Art History

- Books We Love

- CAA Conversations Podcasts

- SoTL Resources

- Teaching Writing About Art

- VISITING THE MUSEUM Learning Resource

- AHTR Weekly

- Digital Art History/Humanities

- Open Educational Resources (OERs)

Survey 1 See all→

- Prehistory and Prehistoric Art in Europe

- Art of the Ancient Near East

- Art of Ancient Egypt

- Jewish and Early Christian Art

- Byzantine Art and Architecture

- Islamic Art

- Buddhist Art and Architecture Before 1200

- Hindu Art and Architecture Before 1300

- Chinese Art Before 1300

- Japanese Art Before 1392

- Art of the Americas Before 1300

- Early Medieval Art

Survey 2 See all→

- Rapa Nui: Thematic and Narrative Shifts in Curriculum

- Proto-Renaissance in Italy (1200–1400)

- Northern Renaissance Art (1400–1600)

- Sixteenth-Century Northern Europe and Iberia

- Italian Renaissance Art (1400–1600)

- Southern Baroque: Italy and Spain

- Buddhist Art and Architecture in Southeast Asia After 1200

- Chinese Art After 1279

- Japanese Art After 1392

- Art of the Americas After 1300

- Art of the South Pacific: Polynesia

- African Art

- West African Art: Liberia and Sierra Leone

- European and American Architecture (1750–1900)

- Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth-Century Art in Europe and North America

- Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Sculpture

- Realism to Post-Impressionism

- Nineteenth-Century Photography

- Architecture Since 1900

- Twentieth-Century Photography

- Modern Art (1900–50)

- Mexican Muralism

- Art Since 1950 (Part I)

- Art Since 1950 (Part II)

Thematic Lesson Plans See all→

- Art and Cultural Heritage Looting and Destruction

- Art and Labor in the Nineteenth Century

- Art and Political Commitment

- Art History as Civic Engagement

- Comics: Newspaper Comics in the United States

- Comics: Underground and Alternative Comics in the United States

- Disability in Art History

- Educating Artists

- Feminism & Art

- Gender in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Globalism and Transnationalism

- Playing “Indian”: Manifest Destiny, Whiteness, and the Depiction of Native Americans

- Queer Art: 1960s to the Present

- Race and Identity

- Race-ing Art History: Contemporary Reflections on the Art Historical Canon

- Sacred Spaces

- Sexuality in Art

- Check out our e-journal Art History Pedagogy and Practice

- AHTR Weekly The (Contemporary) Art History Mixtape: Setting the Tone in the Classroom with Music

- AHTR Weekly Field Notes from an Experiment in Student-Centered Pedagogy

- Contact us! [email protected]

- Teaching and Learning Resources SoTL Resources

- AHTR Weekly Bringing the Museum to AP Art History—a Model for Collaboration

- Lesson Plans Islamic Art

Art History Teaching Resources (AHTR)

is a peer-populated platform for art history teachers. AHTR is home to a constantly evolving and collectively authored online repository of art history teaching content including, but not limited to, lesson plans, video introductions to museums, book reviews, image clusters, and classroom and museum activities. The site promotes discussion and reflection around new ways of teaching and learning in the art history classroom through a peer-populated blog, and fosters a collaborative virtual community for art history instructors at all career stages.

From AHTR Weekl y

Lesson Plan Reflection

Re-Teaching Rapa Nui

October 30, 2021

by Ellen C. Caldwell see the complete lesson plan here In January of 2020, just before the world would be unalterably impacted by COVID-19, I had the great fortune of traveling to Rapa Nui. Having taught art history surveys with an emphasis on Polynesian and Oceanic art for over a decade, I had dreamt of […]

Announcement

Revealing Museums — Together

February 19, 2021

How do public art museums function today? Who selects the objects on display and defines the stories that are (de)constructed? What are the value systems underpinning how museum collections and exhibitions operate? Join a three-part series of live online conversations with artists, students, and staff of the MFA Boston, exploring some of the critical questions, structures and processes that guide our museum work today.

February 5, 2021

By Aly Meloche and Francesca Albrezzi February 10th marks the beginning of a CAA annual meeting that promises to be unlike any other. Normally, many of us look forward to the annual meeting as an opportunity to catch up with colleagues from around the world and hear new ideas for research and teaching. It’s strange […]

Online Teaching

Baptism by Fire: Tips and Tactics from My First Time Teaching Remotely

November 20, 2020

While I’ve had many years of experience working with digital tools and creating digital art history projects, the transition to distance learning provided me with an opportunity to get creative and try some things that were new. Here are a few tips and tricks that I used, which others may find useful as we continue to teach and learn in an online environment.

Teaching Strategies

Can COVID-19 Reinvigorate our Teaching? Employing Digital Tools for Spatial Learning

November 14, 2020

Spatial learning provides exciting possibilities, unhindered by remote learning (and perhaps unbound by it?), combining the brain’s natural aptitude for spatial thinking with the contextualization possible through virtual environments.

Conducting SoTL of an online art history course: using discourse analysis of discussion boards

November 1, 2020

For those of us who are just beginning to teach online, the concept of conducting scholarship of teaching and learning in addition to all of the other new responsibilities must sound about as much fun as running a virtual meeting while trying to homeschool new math.

Teaching Strategies Tool

Rethinking the Curriculum by Rethinking the Art History Survey

October 14, 2020

s a Renaissance art historian I am keenly aware of the passion that can be generated through “classic” works of art from the traditional Western survey, but it is long past the time that we stop prioritizing such a model. Doing so would not only be good for art history, but it might also offer the chance to lead by example for greater inclusivity and equity in higher education more broadly.

Writing About Art

Decolonial Introduction to the Theory, History and Criticism of the Arts

September 14, 2020

Written by Carolin Overhoff Ferreira, Associate Professor at the Department of History of ArtFederal at the University of São Paulo, this book “draws on texts from recent picture and image theory, as well as on present-day Amerindian authors, anthropologists and philosophers [to] question the power structure inherent in Eurocentric art discourses and to decolonize art studies, using Brazil’s arts, its theory and history as a case study to do so.”

Equity in Education Online Teaching Reflection Student Voices Teaching Strategies

Student Voices: The Online Switch

August 14, 2020

Author: Xavier Lopez is a queer art history student who has attended San Francisco State University and Mt. San Antonio College. He is transferring to UC Berkeley this coming fall to pursue a B.A. in Art History. With a focus on Pre-Columbian Art, Lopez hopes to further educate himself on these Indigenous cultures along with […]

Assignment Lesson Plan Online Teaching

Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Formal Analysis:Updating a Classroom Staple for the Age of Remote Learning

August 10, 2020

With some creativity and advanced planning, remote modalities can actually offer important silver linings to the art historical instructor. In particular, a well-designed, intentional rethinking of the classic formal analysis exercise has the potential to facilitate the inclusivity that we as instructors strive to foster.

Assignment Online Teaching

What do you see that makes you say that?: Gallery Teaching in the (Online) Art History Classroom

July 31, 2020

This is a reflection on the Hammer Museum Student Educator’s recent shift to digital conversations about art. In the past few months, the educators have transitioned to facilitating conversations about works of art with adult and K-12 groups on Zoom. While the bodily relationship to works of art is lost in the digital sphere, aspects of the educator’s facilitation have become richer and more nuanced.

Teaching Online Now

July 22, 2020

AHTR was founded as a space of community to share successes, failures, and reflections on teaching art history between peers. It was also founded so folks would not have to reinvent the wheel each time they taught; instead, they could expand the knowledge and experiences of colleagues. With this in mind, we have decided to devote the AHTR Weekly to teaching art history online throughout the coming academic year.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Renaissance

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 11, 2023 | Original: April 4, 2018

The Renaissance was a fervent period of European cultural, artistic, political and economic “rebirth” following the Middle Ages. Generally described as taking place from the 14th century to the 17th century, the Renaissance promoted the rediscovery of classical philosophy, literature and art.

Some of the greatest thinkers, authors, statesmen, scientists and artists in human history thrived during this era, while global exploration opened up new lands and cultures to European commerce. The Renaissance is credited with bridging the gap between the Middle Ages and modern-day civilization.

From Darkness to Light: The Renaissance Begins

During the Middle Ages , a period that took place between the fall of ancient Rome in 476 A.D. and the beginning of the 14th century, Europeans made few advances in science and art.

Also known as the “Dark Ages,” the era is often branded as a time of war, ignorance, famine and pandemics such as the Black Death .

Some historians, however, believe that such grim depictions of the Middle Ages were greatly exaggerated, though many agree that there was relatively little regard for ancient Greek and Roman philosophies and learning at the time.

During the 14th century, a cultural movement called humanism began to gain momentum in Italy. Among its many principles, humanism promoted the idea that man was the center of his own universe, and people should embrace human achievements in education, classical arts, literature and science.

In 1450, the invention of the Gutenberg printing press allowed for improved communication throughout Europe and for ideas to spread more quickly.

As a result of this advance in communication, little-known texts from early humanist authors such as those by Francesco Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio, which promoted the renewal of traditional Greek and Roman culture and values, were printed and distributed to the masses.

Additionally, many scholars believe advances in international finance and trade impacted culture in Europe and set the stage for the Renaissance.

Medici Family

The Renaissance started in Florence, Italy, a place with a rich cultural history where wealthy citizens could afford to support budding artists.

Members of the powerful Medici family , which ruled Florence for more than 60 years, were famous backers of the movement.

Great Italian writers, artists, politicians and others declared that they were participating in an intellectual and artistic revolution that would be much different from what they experienced during the Dark Ages.

The movement first expanded to other Italian city-states, such as Venice, Milan, Bologna, Ferrara and Rome. Then, during the 15th century, Renaissance ideas spread from Italy to France and then throughout western and northern Europe.

Although other European countries experienced their Renaissance later than Italy, the impacts were still revolutionary.

Renaissance Geniuses

Some of the most famous and groundbreaking Renaissance intellectuals, artists, scientists and writers include the likes of:

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519): Italian painter, architect, inventor and “Renaissance man” responsible for painting “The Mona Lisa” and “The Last Supper.

- Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536): Scholar from Holland who defined the humanist movement in Northern Europe. Translator of the New Testament into Greek.

- Rene Descartes (1596–1650): French philosopher and mathematician regarded as the father of modern philosophy. Famous for stating, “I think; therefore I am.”

- Galileo (1564-1642): Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer whose pioneering work with telescopes enabled him to describes the moons of Jupiter and rings of Saturn. Placed under house arrest for his views of a heliocentric universe.

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543): Mathematician and astronomer who made first modern scientific argument for the concept of a heliocentric solar system.

- Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679): English philosopher and author of “Leviathan.”

- Geoffrey Chaucer (1343–1400): English poet and author of “The Canterbury Tales.”

- Giotto (1266-1337): Italian painter and architect whose more realistic depictions of human emotions influenced generations of artists. Best known for his frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua.

- Dante (1265–1321): Italian philosopher, poet, writer and political thinker who authored “The Divine Comedy.”

- Niccolo Machiavelli (1469–1527): Italian diplomat and philosopher famous for writing “The Prince” and “The Discourses on Livy.”

- Titian (1488–1576): Italian painter celebrated for his portraits of Pope Paul III and Charles I and his later religious and mythical paintings like “Venus and Adonis” and "Metamorphoses."

- William Tyndale (1494–1536): English biblical translator, humanist and scholar burned at the stake for translating the Bible into English.

- William Byrd (1539/40–1623): English composer known for his development of the English madrigal and his religious organ music.

- John Milton (1608–1674): English poet and historian who wrote the epic poem “Paradise Lost.”

- William Shakespeare (1564–1616): England’s “national poet” and the most famous playwright of all time, celebrated for his sonnets and plays like “Romeo and Juliet."

- Donatello (1386–1466): Italian sculptor celebrated for lifelike sculptures like “David,” commissioned by the Medici family.

- Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510): Italian painter of “Birth of Venus.”

- Raphael (1483–1520): Italian painter who learned from da Vinci and Michelangelo. Best known for his paintings of the Madonna and “The School of Athens.”

- Michelangelo (1475–1564): Italian sculptor, painter and architect who carved “David” and painted The Sistine Chapel in Rome.

Renaissance Impact on Art, Architecture and Science

Art, architecture and science were closely linked during the Renaissance. In fact, it was a unique time when these fields of study fused together seamlessly.

For instance, artists like da Vinci incorporated scientific principles, such as anatomy into their work, so they could recreate the human body with extraordinary precision.

Architects such as Filippo Brunelleschi studied mathematics to accurately engineer and design immense buildings with expansive domes.

Scientific discoveries led to major shifts in thinking: Galileo and Descartes presented a new view of astronomy and mathematics, while Copernicus proposed that the Sun, not the Earth, was the center of the solar system.

Renaissance art was characterized by realism and naturalism. Artists strived to depict people and objects in a true-to-life way.

They used techniques, such as perspective, shadows and light to add depth to their work. Emotion was another quality that artists tried to infuse into their pieces.

Some of the most famous artistic works that were produced during the Renaissance include:

- The Mona Lisa (Da Vinci)

- The Last Supper (Da Vinci)

- Statue of David (Michelangelo)

- The Birth of Venus (Botticelli)

- The Creation of Adam (Michelangelo)

Renaissance Exploration

While many artists and thinkers used their talents to express new ideas, some Europeans took to the seas to learn more about the world around them. In a period known as the Age of Discovery, several important explorations were made.

Voyagers launched expeditions to travel the entire globe. They discovered new shipping routes to the Americas, India and the Far East and explorers trekked across areas that weren’t fully mapped.

Famous journeys were taken by Ferdinand Magellan , Christopher Columbus , Amerigo Vespucci (after whom America is named), Marco Polo , Ponce de Leon , Vasco Núñez de Balboa , Hernando De Soto and other explorers.

Renaissance Religion

Humanism encouraged Europeans to question the role of the Roman Catholic church during the Renaissance.

As more people learned how to read, write and interpret ideas, they began to closely examine and critique religion as they knew it. Also, the printing press allowed for texts, including the Bible, to be easily reproduced and widely read by the people, themselves, for the first time.

In the 16th century, Martin Luther , a German monk, led the Protestant Reformation – a revolutionary movement that caused a split in the Catholic church. Luther questioned many of the practices of the church and whether they aligned with the teachings of the Bible.

As a result, a new form of Christianity , known as Protestantism, was created.

End of the Renaissance

Scholars believe the demise of the Renaissance was the result of several compounding factors.

By the end of the 15th century, numerous wars had plagued the Italian peninsula. Spanish, French and German invaders battling for Italian territories caused disruption and instability in the region.

Also, changing trade routes led to a period of economic decline and limited the amount of money that wealthy contributors could spend on the arts.

Later, in a movement known as the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic church censored artists and writers in response to the Protestant Reformation. Many Renaissance thinkers feared being too bold, which stifled creativity.

Furthermore, in 1545, the Council of Trent established the Roman Inquisition , which made humanism and any views that challenged the Catholic church an act of heresy punishable by death.

By the early 17th century, the Renaissance movement had died out, giving way to the Age of Enlightenment .

Debate Over the Renaissance

While many scholars view the Renaissance as a unique and exciting time in European history, others argue that the period wasn’t much different from the Middle Ages and that both eras overlapped more than traditional accounts suggest.

Also, some modern historians believe that the Middle Ages had a cultural identity that’s been downplayed throughout history and overshadowed by the Renaissance era.

While the exact timing and overall impact of the Renaissance is sometimes debated, there’s little dispute that the events of the period ultimately led to advances that changed the way people understood and interpreted the world around them.

HISTORY Vault: World History

Stream scores of videos about world history, from the Crusades to the Third Reich.

The Renaissance, History World International . The Renaissance – Why it Changed the World, The Telegraph . Facts About the Renaissance, Biography Online . Facts About the Renaissance Period, Interestingfacts.org . What is Humanism? International Humanist and Ethical Union . Why Did the Italian Renaissance End? Dailyhistory.org . The Myth of the Renaissance in Europe, BBC .

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Online Collection

- Explore By...

- Museum Locations

- Plan Your Visit

- Directions & Parking

- Food, Drink, & Shop

- Free Admission

- Accessibility

- Visitor Promise

- Virtual Museum

- Exhibitions & Installations

- Programs & Events

- Collections

- Support the Walters

- Corporate Partnerships

- Institutional Funders

- Evening at the Walters

- Mission & Vision

- Strategic Plan

- Land Acknowledgment

Creative Commons Zero

- arrow_forward_ios

This is a mass-produced replica of a famous miracle-working icon of the Virgin and Child, brought to Russia from Byzatium in the 12th century, known as the "Virgin of Vladimir", and currently kept in Moscow (State Tretyakov Gallery). The Virgin and Child are each identified by abbreviated inscriptions.

Provenance Provenance (from the French provenir , 'to come from/forth') is the chronology of the ownership, custody, or location of a historical object.

Henry Walters, Baltimore [date of acquisition unknown], by purchase; Walters Art Museum, 1931, by bequest.

- social-item

Geographies

Measurements.

H: 1 15/16 x W: 1 13/16 in. (5 x 4.6 cm)

Credit Line

Acquired by Henry Walters

Location in Museum

Not on view

Accession Number In libraries, galleries, museums, and archives, an accession number is a unique identifier assigned to each object in the collection.

Do you have additional information.

Notify the curator

Tooltip description to define this term for visitors to the website.

- Articles >

The Moscow Metro Museum of Art: 10 Must-See Stations

There are few times one can claim having been on the subway all afternoon and loving it, but the Moscow Metro provides just that opportunity. While many cities boast famous public transport systems—New York’s subway, London’s underground, San Salvador’s chicken buses—few warrant hours of exploration. Moscow is different: Take one ride on the Metro, and you’ll find out that this network of railways can be so much more than point A to B drudgery.

The Metro began operating in 1935 with just thirteen stations, covering less than seven miles, but it has since grown into the world’s third busiest transit system ( Tokyo is first ), spanning about 200 miles and offering over 180 stops along the way. The construction of the Metro began under Joseph Stalin’s command, and being one of the USSR’s most ambitious building projects, the iron-fisted leader instructed designers to create a place full of svet (radiance) and svetloe budushchee (a radiant future), a palace for the people and a tribute to the Mother nation.

Consequently, the Metro is among the most memorable attractions in Moscow. The stations provide a unique collection of public art, comparable to anything the city’s galleries have to offer and providing a sense of the Soviet era, which is absent from the State National History Museum. Even better, touring the Metro delivers palpable, experiential moments, which many of us don’t get standing in front of painting or a case of coins.

Though tours are available , discovering the Moscow Metro on your own provides a much more comprehensive, truer experience, something much less sterile than following a guide. What better place is there to see the “real” Moscow than on mass transit: A few hours will expose you to characters and caricatures you’ll be hard-pressed to find dining near the Bolshoi Theater. You become part of the attraction, hear it in the screech of the train, feel it as hurried commuters brush by: The Metro sucks you beneath the city and churns you into the mix.

With the recommendations of our born-and-bred Muscovite students, my wife Emma and I have just taken a self-guided tour of what some locals consider the top ten stations of the Moscow Metro. What most satisfied me about our Metro tour was the sense of adventure . I loved following our route on the maps of the wagon walls as we circled the city, plotting out the course to the subsequent stops; having the weird sensation of being underground for nearly four hours; and discovering the next cavern of treasures, playing Indiana Jones for the afternoon, piecing together fragments of Russia’s mysterious history. It’s the ultimate interactive museum.

Top Ten Stations (In order of appearance)

Kievskaya station.

Kievskaya Station went public in March of 1937, the rails between it and Park Kultury Station being the first to cross the Moscow River. Kievskaya is full of mosaics depicting aristocratic scenes of Russian life, with great cameo appearances by Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin. Each work has a Cyrillic title/explanation etched in the marble beneath it; however, if your Russian is rusty, you can just appreciate seeing familiar revolutionary dates like 1905 ( the Russian Revolution ) and 1917 ( the October Revolution ).

Mayakovskaya Station

Mayakovskaya Station ranks in my top three most notable Metro stations. Mayakovskaya just feels right, done Art Deco but no sense of gaudiness or pretention. The arches are adorned with rounded chrome piping and create feeling of being in a jukebox, but the roof’s expansive mosaics of the sky are the real showstopper. Subjects cleverly range from looking up at a high jumper, workers atop a building, spires of Orthodox cathedrals, to nimble aircraft humming by, a fleet of prop planes spelling out CCCP in the bluest of skies.

Novoslobodskaya Station

Novoslobodskaya is the Metro’s unique stained glass station. Each column has its own distinctive panels of colorful glass, most of them with a floral theme, some of them capturing the odd sailor, musician, artist, gardener, or stenographer in action. The glass is framed in Art Deco metalwork, and there is the lovely aspect of discovering panels in the less frequented haunches of the hall (on the trackside, between the incoming staircases). Novosblod is, I’ve been told, the favorite amongst out-of-town visitors.

Komsomolskaya Station

Komsomolskaya Station is one of palatial grandeur. It seems both magnificent and obligatory, like the presidential palace of a colonial city. The yellow ceiling has leafy, white concrete garland and a series of golden military mosaics accenting the tile mosaics of glorified Russian life. Switching lines here, the hallway has an Alice-in-Wonderland feel, impossibly long with decorative tile walls, culminating in a very old station left in a remarkable state of disrepair, offering a really tangible glimpse behind the palace walls.

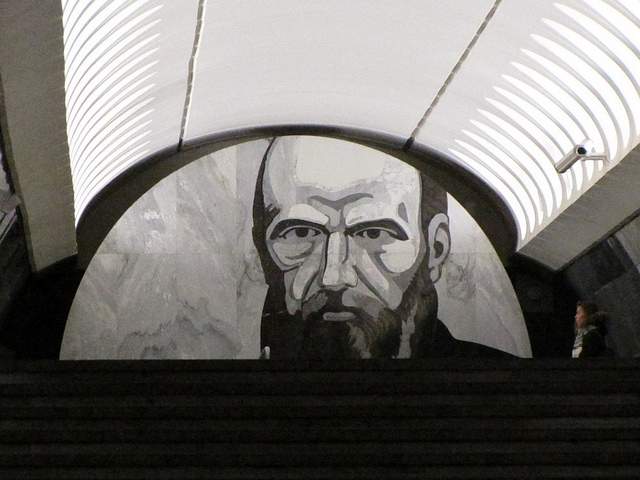

Dostoevskaya Station

Dostoevskaya is a tribute to the late, great hero of Russian literature . The station at first glance seems bare and unimpressive, a stark marble platform without a whiff of reassembled chips of tile. However, two columns have eerie stone inlay collages of scenes from Dostoevsky’s work, including The Idiot , The Brothers Karamazov , and Crime and Punishment. Then, standing at the center of the platform, the marble creates a kaleidoscope of reflections. At the entrance, there is a large, inlay portrait of the author.

Chkalovskaya Station

Chkalovskaya does space Art Deco style (yet again). Chrome borders all. Passageways with curvy overhangs create the illusion of walking through the belly of a chic, new-age spacecraft. There are two (kos)mosaics, one at each end, with planetary subjects. Transferring here brings you above ground, where some rather elaborate metalwork is on display. By name similarity only, I’d expected Komsolskaya Station to deliver some kosmonaut décor; instead, it was Chkalovskaya that took us up to the space station.

Elektrozavodskaya Station

Elektrozavodskaya is full of marble reliefs of workers, men and women, laboring through the different stages of industry. The superhuman figures are round with muscles, Hollywood fit, and seemingly undeterred by each Herculean task they respectively perform. The station is chocked with brass, from hammer and sickle light fixtures to beautiful, angular framework up the innards of the columns. The station’s art pieces are less clever or extravagant than others, but identifying the different stages of industry is entertaining.

Baumanskaya Statio

Baumanskaya Station is the only stop that wasn’t suggested by the students. Pulling in, the network of statues was just too enticing: Out of half-circle depressions in the platform’s columns, the USSR’s proud and powerful labor force again flaunts its success. Pilots, blacksmiths, politicians, and artists have all congregated, posing amongst more Art Deco framing. At the far end, a massive Soviet flag dons the face of Lenin and banners for ’05, ’17, and ‘45. Standing in front of the flag, you can play with the echoing roof.

Ploshchad Revolutsii Station

Novokuznetskaya Station

Novokuznetskaya Station finishes off this tour, more or less, where it started: beautiful mosaics. This station recalls the skyward-facing pieces from Mayakovskaya (Station #2), only with a little larger pictures in a more cramped, very trafficked area. Due to a line of street lamps in the center of the platform, it has the atmosphere of a bustling market. The more inventive sky scenes include a man on a ladder, women picking fruit, and a tank-dozer being craned in. The station’s also has a handsome black-and-white stone mural.

Here is a map and a brief description of our route:

Start at (1)Kievskaya on the “ring line” (look for the squares at the bottom of the platform signs to help you navigate—the ring line is #5, brown line) and go north to Belorusskaya, make a quick switch to the Dark Green/#2 line, and go south one stop to (2)Mayakovskaya. Backtrack to the ring line—Brown/#5—and continue north, getting off at (3)Novosblodskaya and (4)Komsolskaya. At Komsolskaya Station, transfer to the Red/#1 line, go south for two stops to Chistye Prudy, and get on the Light Green/#10 line going north. Take a look at (5)Dostoevskaya Station on the northern segment of Light Green/#10 line then change directions and head south to (6)Chkalovskaya, which offers a transfer to the Dark Blue/#3 line, going west, away from the city center. Have a look (7)Elektroskaya Station before backtracking into the center of Moscow, stopping off at (8)Baumskaya, getting off the Dark Blue/#3 line at (9)Ploschad Revolyutsii. Change to the Dark Green/#2 line and go south one stop to see (10)Novokuznetskaya Station.

Check out our new Moscow Indie Travel Guide , book a flight to Moscow and read 10 Bars with Views Worth Blowing the Budget For

Jonathon Engels, formerly a patron saint of misadventure, has been stumbling his way across cultural borders since 2005 and is currently volunteering in the mountains outside of Antigua, Guatemala. For more of his work, visit his website and blog .

Photo credits: SergeyRod , all others courtesy of the author and may not be used without permission

- Photography

- Film + Video

- Culture + Lifestyle

- Exhibits + Events

- Prescriptions

- Photographers

- Designers/Architects

- Organizations/Mags

- Museums/Galleries

- ANNOUNCEMENTS

- COLLECTIONS

- EXHIBITIONS

- 30/30 WOMEN

- CONTRIBUTORS

- SUBMISSIONS

- 30/30 WOMEN PHOTOGRAPHERS

I was born and raised in a working-class city, Elektrostal, Moscow region. I received a higher education in television in Moscow. I studied to be a documentary photographer. My vision of the aesthetics of the frame was significantly influenced by the aesthetics of my city – the endless forests and swamps of the Moscow region with endless factories, typical architecture and a meagre color palette. In this harsh world, people live and work, raise children, grow geranium, throw parties and live trouble, run a ski cross. They are the main characters of my photo projects.

I study a person in a variety of circumstances. We blog with friends with stories of such people. We are citizen journalists. In my works, I touch upon the topics of homelessness, people’s attitude to their bodies, sexual objectification, women’s work, alienation and living conditions of different people. The opportunity to communicate with my characters gives me a sense of belonging and modernity of life.

My photos create the effect of presence, invisible observation of people. I don’t interfere with what’s going on, I’m taking the place of an outside observer. I’m a participant in exhibitions in Rome (Loosenart Gallery), Collaborated with the Russian Geographical Community.

30 Under 30 Women Photographers 2021

- --> --> Thailand Biennale 2023 / The Open World Dec 9, 2023 – Apr 30, 2024 Thailand Biennale Mueang Chiang Rai, Thailand The first edition of Thailand Biennale was initiated by the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture, Thailand’s Ministry of Culture in Krabi in 2018, followed by Korat in 2021. By alternating the locations from various provinces throughout the country, the spirit of the Thailand Biennale decentralizes artistic activities (more…) Show Post >

- --> --> Tarek Lakhrissi: BLISS Feb 10 – May 20, 2024 Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst Zurich, Switzerland In his solo exhibition BLISS , Tarek Lakhrissi invites the audience on a journey: in a stage-like setting, visitors become protagonists in search of dreamy moments in the midst of chaos. Over the course of three acts, they encounter immersive installations, an enchanting film work and larger-than-life sculptures. (more…) Show Post >

- --> --> Tina Berning ARTIST / ILLUSTRATOR Featured Profile Tina Berning (b. 1969 / Braunschweig, Germany) is a Berlin based artist and illustrator. After working as a graphic designer for several years, she began to focus on drawing and Illustration. (more…) Show Post > See Full Profile >

- --> --> Anish Kapoor: Unseen Apr 11 – Oct 20, 2024 ARKEN Ishøj, Denmark Anish Kapoor’s monumental sculptures and installations speak directly to our senses and emotions. Through his unique eye for materials, shapes, colours and surfaces we are drawn into and seduced by his artwork, which turns the world upside down – often quite literally. Kapoor has been shown in the largest exhibition venues in the world, and he has also created several significant pieces for public spaces. (more…) Show Post >

- --> --> Pia Arke: Silences and Stories Feb 10 – May 11, 2024 John Hansard Gallery Southampton, UK In February 2024, John Hansard Gallery, in collaboration with KW Institute for Contemporary Art , Berlin, presents the first major survey of Danish-Greenlandic artist Pia Arke (1958–2007) to be shown outside of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland), and the Nordic countries. Seldom exhibited outside the Scandinavian context, this exhibition of Arke’s work is both timely and long overdue. (more…) Show Post >

- --> --> Jalan & Jibril Durimel Photographers Featured Profile Twin brothers Jalan & Jibril Durimel draw inspiration through their diversified upbringing between the French Antilles and the US. Born in Paris to parents from the island of Guadeloupe, at the age of 4 they moved to Miami where they first immersed themselves in American culture. (more…) Show Post > See Full Profile >

- --> --> Boris Mikhailov Photographer Featured Profile Ukrainian born Boris Mikhailov is one of the leading photographers from the former Soviet Union. For over 30 years, he has explored the position of the individual within the historical mechanisms of public ideology, touching on such subjects as Ukraine under Soviet rule (more…) Show Post > See Full Profile >

- --> --> Maria Sturm: You Don’t Look Native to Me Publication Void International In 2011, Maria Sturm began to photograph the lives of young people from the Lumbee Tribe around Pembroke, Robeson County, North Carolina. Through the process of documenting their lives, Sturm began to question her own understanding of what it means to be Native American. Her new book You Don’t Look Native to Me combines photographs with interviews and texts to preconceptions and show Native identity not as fixed, but evolving and redefining itself with each generation. (more…) Show Post >

- --> --> 30 Under 30 Women Photographers / 2024 Selections Announced Artpil International Artpil proudly announces for its 15th Edition the selection of 30 Under 30 Women Photographers / 2024 . Founded in 2010, this annual selection has helped emerging, mid-career, as well as some accomplished women photographers to gain further exposure and participate in the collective among peers. (more…) Show Post > See Full Article >

- photography

- film + video

- culture + lifestyle

- exhibits + events

- prescriptions

- photographers

- designers/architects

- organizations/mags

- museums/galleries

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Renaissance art, painting, sculpture, architecture, music, and literature produced during the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries in Europe under the combined influences of an increased awareness of nature, a revival of classical learning, and a more individualistic view of man.

Faber Hall 463. Bronx, NY 10458 • USA. Teaching resources for World History, European History, and Renaissance studies, or the era ca. 1300-1700, including the following topics: Reformation, print revolution, scientific revolution, economic history, and Counter-Reformation.

The origins of Renaissance art can be traced to Italy in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. During this so-called "proto-Renaissance" period (1280-1400), Italian scholars and artists saw ...

Italian Renaissance Learning Resources. A freely available resource, this site features eight units, each of which explores a different theme in Italian Renaissance art: Researchers and students can explore thematic essays, more than 300 images, 300 glossary items and 42 primary source texts. An invaluable tool for use in the classroom ...

To understand the art of the Italian renaissance, we need to consider the values, social mores, and the religious and political interests of the people who made, paid for, and first looked at the art. Unfortunately, our knowledge of these people is limited and skewed. History is most often written by those in positions of privilege and power ...

The Classical Revival. A defining feature of the Renaissance period was the re-interest in the ancient world of Greece and Rome.As part of what we now call Renaissance humanism, classical literature, architecture, and art were all consulted to extract ideas that could be transformed for the contemporary world.Lorenzo de Medici (1449-1492 CE), head of the great Florentine family, was a notable ...

The purpose of this assignment is to gain greater analytical skills upon viewing art from the Renaissance period. Being able to analyze works of art and primary source documents is an important component of this course. I have planned a field trip to The National Gallery of Art which has one of the nation's best Renaissance art collections.

Raphael (1483-1520): High Renaissance painter Raphael is known for his frescoes in the Vatican, including The School of Athens, and for his rivalry with Michelangelo. 6. Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528): German High Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer is best known for his portraits and religious altarpiece. 7.

Module 8 Late Gothic_Renaissance Art. Search for: Module 8 Renaissance Art Written Assignment. Written Assignment The Northern Renaissance Class, This is a research essay, about 350 words, more if you get going, Mr. S. ...

I want you to research one of the following two works of art by these influential artists connected to the Renaissance in Northern Europe. The first work is called the Ghent Altarpiece by Jan Van Eyck, a Flemish artist in the medieval Belgium city of Ghent.

A freely available resource, this site features eight units, each of which explores a different theme in Italian Renaissance art. Teaching Packets Available By Download. Art Nouveau, 1890-1914 At its height, art nouveau was a concerted attempt to create an international style. This teaching packet presents an overview of the movement ...

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform! Renaissance lessons, Powerpoint presentations, audio and video files available to teachers and homeschoolers from mrdowling.com.

Sixteenth-Century Northern Europe and Iberia. Italian Renaissance Art (1400-1600) Southern Baroque: Italy and Spain. Buddhist Art and Architecture in Southeast Asia After 1200. Chinese Art After 1279. Japanese Art After 1392. Art of the Americas After 1300. Art of the South Pacific: Polynesia. African Art.

The Renaissance was a period in European civilization that immediately followed the Middle Ages and reached its height in the 15th century. It is conventionally held to have been characterized by a surge of interest in Classical scholarship and values. The Renaissance also witnessed the discovery and exploration of new continents and numerous important inventions.

Connecting new ideas discussed on the tour to prior knowledge of Renaissance art and culture. In-Person Tour Information. Group Size: Up to 90 students. Length: 75 minutes. Meeting Location: West Building Rotunda. Important Scheduling Information. Tours must be scheduled at least four weeks in advance. Groups must contain at least 15 students.

From Darkness to Light: The Renaissance Begins. During the Middle Ages, a period that took place between the fall of ancient Rome in 476 A.D. and the beginning of the 14th century, Europeans made ...

Assignment Instructions: Renaissance Art

2.34.W - Assignment: Renaissance Art Submission Rosa Miller Mr. Beeler World History I August 13, 2021 Renaissance Art Submission 1. Birth of St. John the Baptist, Ghirlandaio. a. In the painting of the birth of John the Baptist, there is an elegant room with a bed and women dressed in fine clothes. A woman is sitting in bed with her legs covered, while behind the bed, there is a woman with a ...

HI0900 Images are taken from the Web Gallery of Art, a free resource for students. RENAISSANCE ART ASSIGNMENT In this exercise, you will evaluate and explain various works of Renaissance art. You will type your observations and analyses into a single Word document. Carefully read through all of the instructions before you begin the exercise. Begin by reviewing your lesson material that covers ...

This is a mass-produced replica of a famous miracle-working icon of the Virgin and Child, brought to Russia from Byzatium in the 12th century, known as the "Virgin of Vladimir", and currently kept in Moscow (State Tretyakov Gallery). The Virgin and Child are each identified by abbreviated inscriptions.

View 11.34.F - Assignment Renaissance Art Assignment.docx from HIUS 234 at Liberty University Online Academy. Niliana Madrigal Ms. Mills World History I June 26, 2022 1. Ghirlandaio- Birth of St.

Have a look (7)Elektroskaya Station before backtracking into the center of Moscow, stopping off at (8)Baumskaya, getting off the Dark Blue/#3 line at (9)Ploschad Revolyutsii. Change to the Dark Green/#2 line and go south one stop to see (10)Novokuznetskaya Station. Check out our new Moscow Indie Travel Guide, book a flight to Moscow and read 10 ...

I was born and raised in a working-class city, Elektrostal, Moscow region. I received a higher education in television in Moscow. I studied to be a documentary photographer. My vision of the aesthetics of the frame was significantly influenced by the aesthetics of my city - the endless forests and swamps of the Moscow region with endless factories, typical architecture and a meagre color palette.