Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 4: Theoretical frameworks for qualitative research

Tess Tsindos

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe qualitative frameworks.

- Explain why frameworks are used in qualitative research.

- Identify various frameworks used in qualitative research.

What is a Framework?

A framework is a set of broad concepts or principles used to guide research. As described by Varpio and colleagues 1 , a framework is a logically developed and connected set of concepts and premises – developed from one or more theories – that a researcher uses as a scaffold for their study. The researcher must define any concepts and theories that will provide the grounding for the research and link them through logical connections, and must relate these concepts to the study that is being carried out. In using a particular theory to guide their study, the researcher needs to ensure that the theoretical framework is reflected in the work in which they are engaged.

It is important to acknowledge that the terms ‘theories’ ( see Chapter 3 ), ‘frameworks’ and ‘paradigms’ are sometimes used interchangeably. However, there are differences between these concepts. To complicate matters further, theoretical frameworks and conceptual frameworks are also used. In addition, quantitative and qualitative researchers usually start from different standpoints in terms of theories and frameworks.

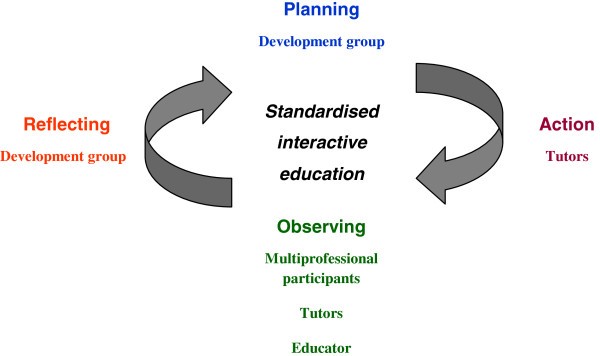

A diagram by Varpio and colleagues demonstrates the similarities and differences between theories and frameworks, and how they influence research approaches. 1(p991) The diagram displays the objectivist or deductive approach to research on the left-hand side. Note how the conceptual framework is first finalised before any research is commenced, and it involves the articulation of hypotheses that are to be tested using the data collected. This is often referred to as a top-down approach and/or a general (theory or framework) to a specific (data) approach.

The diagram displays the subjectivist or inductive approach to research on the right-hand side. Note how data is collected first, and through data analysis, a tentative framework is proposed. The framework is then firmed up as new insights are gained from the data analysis. This is referred to as a specific (data) to general (theory and framework) approach .

Why d o w e u se f rameworks?

A framework helps guide the questions used to elicit your data collection. A framework is not prescriptive, but it needs to be suitable for the research question(s), setting and participants. Therefore, the researcher might use different frameworks to guide different research studies.

A framework informs the study’s recruitment and sampling, and informs, guides or structures how data is collected and analysed. For example, a framework concerned with health systems will assist the researcher to analyse the data in a certain way, while a framework concerned with psychological development will have very different ways of approaching the analysis of data. This is due to the differences underpinning the concepts and premises concerned with investigating health systems, compared to the study of psychological development. The framework adopted also guides emerging interpretations of the data and helps in comparing and contrasting data across participants, cases and studies.

Some examples of foundational frameworks used to guide qualitative research in health services and public health:

- The Behaviour Change Wheel 2

- Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) 3

- Theoretical framework of acceptability 4

- Normalization Process Theory 5

- Candidacy Framework 6

- Aboriginal social determinants of health 7(p8)

- Social determinants of health 8

- Social model of health 9,10

- Systems theory 11

- Biopsychosocial model 12

- Discipline-specific models

- Disease-specific frameworks

E xamples of f rameworks

In Table 4.1, citations of published papers are included to demonstrate how the particular framework helps to ‘frame’ the research question and the interpretation of results.

Table 4.1. Frameworks and references

As discussed in Chapter 3, qualitative research is not an absolute science. While not all research may need a framework or theory (particularly descriptive studies, outlined in Chapter 5), the use of a framework or theory can help to position the research questions, research processes and conclusions and implications within the relevant research paradigm. Theories and frameworks also help to bring to focus areas of the research problem that may not have been considered.

- Varpio L, Paradis E, Uijtdehaage S, Young M. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad Med . 2020;95(7):989-994. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003075

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci . 2011;6:42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- CFIR Research Team. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Center for Clinical Management Research. 2023. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://cfirguide.org/

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res . 2017;17:88. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

- Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med . 2010;8:63. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-63

- Tookey S, Renzi C, Waller J, von Wagner C, Whitaker KL. Using the candidacy framework to understand how doctor-patient interactions influence perceived eligibility to seek help for cancer alarm symptoms: a qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv Res . 2018;18(1):937. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3730-5

- Lyon P. Aboriginal Health in Aboriginal Hands: Community-Controlled Comprehensive Primary Health Care @ Central Australian Aboriginal Congress; 2016. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://nacchocommunique.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/cphc-congress-final-report.pdf

- Solar O., Irwin A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice); 2010. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852

- Yuill C, Crinson I, Duncan E. Key Concepts in Health Studies . SAGE Publications; 2010.

- Germov J. Imagining health problems as social issues. In: Germov J, ed. Second Opinion: An Introduction to Health Sociology . Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Laszlo A, Krippner S. Systems theories: their origins, foundations, and development. In: Jordan JS, ed. Advances in Psychology . Science Direct; 1998:47-74.

- Engel GL. From biomedical to biopsychosocial: being scientific in the human domain. Psychosomatics . 1997;38(6):521-528. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71396-3

- Schmidtke KA, Drinkwater KG. A cross-sectional survey assessing the influence of theoretically informed behavioural factors on hand hygiene across seven countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1432. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11491-4

- Graham-Wisener L, Nelson A, Byrne A, et al. Understanding public attitudes to death talk and advance care planning in Northern Ireland using health behaviour change theory: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:906. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13319-1

- Walker R, Quong S, Olivier P, Wu L, Xie J, Boyle J. Empowerment for behaviour change through social connections: a qualitative exploration of women’s preferences in preconception health promotion in the state of Victoria, Australia. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1642. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-14028-5

- Ayton DR, Barker AL, Morello RT, et al. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of the 6-PACK falls prevention program: a pre-implementation study in hospitals participating in a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLOS ONE . 2017;12(2):e0171932. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171932

- Pratt R, Xiong S, Kmiecik A, et al. The implementation of a smoking cessation and alcohol abstinence intervention for people experiencing homelessness. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1260. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13563-5

- Bossert J, Mahler C, Boltenhagen U, et al. Protocol for the process evaluation of a counselling intervention designed to educate cancer patients on complementary and integrative health care and promote interprofessional collaboration in this area (the CCC-Integrativ study). PLOS ONE . 2022;17(5):e0268091. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0268091

- Lwin KS, Bhandari AKC, Nguyen PT, et al. Factors influencing implementation of health-promoting interventions at workplaces: protocol for a scoping review. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275887. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275887

- Wilhelm AK, Schwedhelm M, Bigelow M, et al. Evaluation of a school-based participatory intervention to improve school environments using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1615. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11644-5

- Timm L, Annerstedt KS, Ahlgren JÁ, et al. Application of the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability to assess a telephone-facilitated health coaching intervention for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275576. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275576

- Laing L, Salema N-E, Jeffries M, et al. Understanding factors that could influence patient acceptability of the use of the PINCER intervention in primary care: a qualitative exploration using the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275633

- Renko E, Knittle K, Palsola M, Lintunen T, Hankonen N. Acceptability, reach and implementation of a training to enhance teachers’ skills in physical activity promotion. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1568. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09653-x

- Alexander SM, Agaba A, Campbell JI, et al. A qualitative study of the acceptability of remote electronic bednet use monitoring in Uganda. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1010. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13393

- May C, Rapley T, Mair FS, et al. Normalization Process Theory On-line Users’ Manual, Toolkit and NoMAD instrument. 2015. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://normalization-process-theory.northumbria.ac.uk/

- Davis S. Ready for prime time? Using Normalization Process Theory to evaluate implementation success of personal health records designed for decision making. Front Digit Health . 2020;2:575951. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2020.575951

- Durand M-A, Lamouroux A, Redmond NM, et al. Impact of a health literacy intervention combining general practitioner training and a consumer facing intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening in underserved areas: protocol for a multicentric cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1684. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11565

- Jones SE, Hamilton S, Bell R, Araújo-Soares V, White M. Acceptability of a cessation intervention for pregnant smokers: a qualitative study guided by Normalization Process Theory. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1512. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09608-2

- Ziegler E, Valaitis R, Yost J, Carter N, Risdon C. “Primary care is primary care”: use of Normalization Process Theory to explore the implementation of primary care services for transgender individuals in Ontario. PLOS ONE . 2019;14(4):e0215873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215873

- Mackenzie M, Conway E, Hastings A, Munro M, O’Donnell C. Is ‘candidacy’ a useful concept for understanding journeys through public services? A critical interpretive literature synthesis. Soc Policy Adm . 2013;47(7):806-825. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00864.x

- Adeagbo O, Herbst C, Blandford A, et al. Exploring people’s candidacy for mobile health–supported HIV testing and care services in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res . 2019;21(11):e15681. doi:10.2196/15681

- Mackenzie M, Turner F, Platt S, et al. What is the ‘problem’ that outreach work seeks to address and how might it be tackled? Seeking theory in a primary health prevention programme. BMC Health Serv Res . 2011;11:350. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-350

- Liberati E, Richards N, Parker J, et al. Qualitative study of candidacy and access to secondary mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Med. 2022;296:114711. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114711

- Pearson O, Schwartzkopff K, Dawson A, et al. Aboriginal community controlled health organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1859. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09943-4

- Freeman T, Baum F, Lawless A, et al. Revisiting the ability of Australian primary healthcare services to respond to health inequity. Aust J Prim Health . 2016;22(4):332-338. doi:10.1071/PY14180

- Couzos S. Towards a National Primary Health Care Strategy: Fulfilling Aboriginal Peoples Aspirations to Close the Gap . National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. 2009. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/35080/

- Napier AD, Ancarno C, Butler B, et al. Culture and health. Lancet . 2014;384(9954):1607-1639. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61603-2

- WHO. COVID-19 and the Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity: Evidence Brief . 2021. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038387

- WHO. Social Determinants of Health . 2023. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- McCrae JS, Robinson JAL, Spain AK, Byers K, Axelrod JL. The Mitigating Toxic Stress study design: approaches to developmental evaluation of pediatric health care innovations addressing social determinants of health and toxic stress. BMC Health Serv Res . 2021;21:71. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06057-4

- Hosseinpoor AR, Stewart Williams J, Jann B, et al. Social determinants of sex differences in disability among older adults: a multi-country decomposition analysis using the World Health Survey. Int J Equity Health . 2012;11:52. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-11-52

- Kabore A, Afriyie-Gyawu E, Awua J, et al. Social ecological factors affecting substance abuse in Ghana (West Africa) using photovoice. Pan Afr Med J . 2019;34:214. doi:10.11604/pamj.2019.34.214.12851

- Bíró É, Vincze F, Mátyás G, Kósa K. Recursive path model for health literacy: the effect of social support and geographical residence. Front Public Health . 2021;9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.724995

- Yuan B, Zhang T, Li J. Family support and transport cost: understanding health service among older people from the perspective of social-ecological model. Arch Public Health . 2022;80:173. doi:10.1186/s13690-022-00923-1

- Mahmoodi Z, Karimlou M, Sajjadi H, Dejman M, Vameghi M, Dolatian M. A communicative model of mothers’ lifestyles during pregnancy with low birth weight based on social determinants of health: a path analysis. Oman Med J . 2017 ;32(4):306-314. doi:10.5001/omj.2017.59

- Vella SA, Schweickle MJ, Sutcliffe J, Liddelow C, Swann C. A systems theory of mental health in recreational sport. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2022;19(21):14244. doi:10.3390/ijerph192114244

- Henning S. The wellness of airline cabin attendants: A systems theory perspective. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure . 2015;4(1):1-11. Accessed February 15, 2023. http://www.ajhtl.com/archive.html

- Sutphin ST, McDonough S, Schrenkel A. The role of formal theory in social work research: formalizing family systems theory. Adv Soc Work . 2013;14(2):501-517. doi:10.18060/7942

- Colla R, Williams P, Oades LG, Camacho-Morles J. “A new hope” for positive psychology: a dynamic systems reconceptualization of hope theory. Front Psychol . 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809053

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–136. doi:10.1126/science.847460

- Wade DT, HalliganPW. The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clin Rehabi l. 2017;31(8):995–1004. doi:10.1177/0269215517709890

- Ip L, Smith A, Papachristou I, Tolani E. 3 Dimensions for Long Term Conditions – creating a sustainable bio-psycho-social approach to healthcare. J Integr Care . 2019;19(4):5. doi:10.5334/ijic.s3005

- FrameWorks Institute. A Matter of Life and Death: Explaining the Wider Determinants of Health in the UK . FrameWorks Institute; 2022. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FWI-30-uk-health-brief-v3a.pdf

- Zemed A, Nigussie Chala K, Azeze Eriku G, Yalew Aschalew A. Health-related quality of life and associated factors among patients with stroke at tertiary level hospitals in Ethiopia. PLOS ONE . 2021;16(3):e0248481. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248481

- Finch E, Foster M, Cruwys T, et al. Meeting unmet needs following minor stroke: the SUN randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Health Serv Res . 2019;19:894. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4746-1

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners Copyright © 2023 by Tess Tsindos is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

What Is A Theoretical Framework? A Practical Answer

- Published: 30 November 2015

- Volume 26 , pages 593–597, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

- Norman G. Lederman 1 &

- Judith S. Lederman 1

211k Accesses

26 Citations

37 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Other than the poor or non-existent validity and/or reliability of data collection measures, the lack of a theoretical framework is the most frequently cited reason for our editorial decision not to publish a manuscript in the Journal of Science Teacher Education . A poor or missing theoretical framework is similarly a critical problem for manuscripts submitted to other journals for which Norman or Judith have either served as Editor or been on the Editorial Board. Often the problem is that an author fails to justify his/her research effort with a theoretical framework. However, there is another level to the problem. Many individuals have a rather narrow conception of what constitutes a theoretical framework or that it is somehow distinct from a conceptual framework. The distinction on lack thereof is a story for another day. The following story may remind you of an experience you or one of your classmates have had.

Doctoral students live in fear of hearing these now famous words from their thesis advisor: “This sounds like a promising study, but what is your theoretical framework?” These words instantly send the harried doctoral student to the library (giving away our ages) in search of a theory to support the proposed research and to satisfy his/her advisor. The search is often unsuccessful because of the student’s misconception of what constitutes a “theoretical framework.” The framework may actually be a theory, but not necessarily. This is especially true for theory driven research (typically quantitative) that is attempting to test the validity of existing theory. However, this narrow definition of a theoretical framework is commonly not aligned with qualitative research paradigms that are attempting to develop theory, for example, grounded theory, or research falling into the categories of description and interpretation research (Peshkin, 1993 ). Additionally, a large proportion of doctoral theses do not fit the narrow definition described. The argument here is not that various research paradigms have no overarching philosophies or theories about knowing. Clearly quantitative research paradigms are couched in a realist perspective and qualitative research paradigms are couched in an idealist perspective (Bogdan & Biklen, 1982 ). The discussion here is focused on theoretical frameworks at a much more specific and localized perspective with respect to the justification and conceptualization of a single research investigation. So, what is a theoretical framework?

It is, perhaps, easier to understand the nature and function of a theoretical framework if it is viewed as the answer to two basic questions:

What is the problem or question?

Why is your approach to solving the problem or answering the question feasible?

Indeed, the answers to these questions are the substance and culmination of Chapters I and II of the proposal and completed dissertation, or the initial sections preceding the Methods section of a research article. The answers to these questions can come from only one source, a thorough review of the literature (i.e., a review that includes both the theoretical and empirical literature as well as apparent gaps in the literature). Perhaps, a hypothetical situation can best illustrate the development and role of the theoretical framework in the formalization of a dissertation topic or research investigation. Let us continue with the doctoral student example, keeping in mind that a parallel situation also presents itself to any researcher planning research that he/she intends to publish.

As an interested reader of educational literature, a doctoral student becomes intrigued by the importance of questioning in the secondary classroom. The student immediately begins a manual and computer search of the literature on questioning in the classroom. The student notices that the research findings on the effectiveness of questioning strategies are rather equivocal. In particular, much of the research focuses on the cognitive levels of the questions asked by the teacher and how these questions influence student achievement. It appears that the research findings exhibit no clear pattern. That is, in some studies, frequent questioning at higher cognitive levels has led to more achievement than frequent questioning at the lower cognitive levels. However, an equal number of investigations have shown no differences between the achievement of students who are exposed to questions at distinctly different cognitive levels, but rather the simple frequency of questions.

The doctoral student becomes intrigued by these equivocal findings and begins to speculate about some possible explanations. In a blinding flash of insight, the student remembers hearing somewhere that an eccentric Frenchman named Piaget said something about students being categorized into levels of cognitive development. Could it be that a student’s cognitive level has something to do with how much and what he/she learns? The student heads back to the library and methodically searches through the literature on cognitive development and its relationship to achievement.

At this point, the doctoral student has become quite familiar with two distinct lines of educational research. The research on the effectiveness of questioning has established that there is a problem. That is, does the cognitive level of questioning have any effect on student achievement? In effect, this answers the first question identified previously with respect to identification of a theoretical framework. The research on the cognitive development of students has provided an intriguing perspective. That is, could it be possible that students of different cognitive levels are affected differently by questions at different cognitive levels? If so, an answer to the problem concerning the effectiveness questioning may be at hand. This latter question, in effect, has addressed the second question previously posed about the identification of a theoretical framework. At this point, the student has narrowed his/her interests as a result of reviewing the literature. Note that the doctoral student is now ready to write down a specific research question and that this is only possible after having conducted a thorough review of the literature.

The student writes down the following research hypotheses:

Both high and low cognitive level pupils will benefit from both high and low cognitive levels of questions as opposed to no questions at all.

Pupils categorized at high cognitive levels will benefit more from high cognitive level questions than from low level questions.

Pupils categorized at lower cognitive levels will benefit more from low cognitive level questions than from high level questions.

These research questions still need to be transformed into testable statistical hypotheses, but they are ready to be presented to the dissertation advisor. The advisor looks at the questions and says: “This looks like a promising study, but what is your theoretical framework?” There is no need, however for a sprint to the library. The doctoral student has a theoretical framework. The literature on questioning has established that there is a problem and the literature on cognitive development has provided the rationale for performing the specific investigation that is being proposed. ALL IS WELL!

If some of the initial research completed by Norman concerning what classroom variables contributed to students’ understandings of nature of science (Lederman, 1986a , 1986b ; Lederman & Druger, 1985 ) had to align with the overly restricted definition of a theoretical framework, which necessitates the presence of theory, it never would have been published. In these initial studies, various classroom variables were identified that were related to students’ improved understandings of nature of science. The studies were descriptive and correlational and were not driven by any theory about how students learn nature of science. Indeed, the design of the studies was derived from the fact that there were no existing theories, general or specific, to explain how students might learn nature of science more effectively. Similarly, the seminal study of effective teaching, the Beginning Teacher Evaluation Study (Tikunoff, Berliner, & Rist, 1975 ), was an ethnographic study that was not guided by the findings of previous research on effective teaching. Rather, their inductive study simply compared 40 teachers “known” to be effective and ineffective of mathematics and reading to derive differences in classroom practice. Their study had no theoretical framework if one were to use the restrictive conception that a theory needed to provide a guiding framework for the investigation. There are plenty of other examples that have guided lines of research that could be provided, but there is no need to beat a dead horse by detailing more examples. The simple, but important, point is that research following qualitative research paradigms or traditions (Jacob, 1987 ; Smith, 1987 ) are particularly vulnerable to how ‘theoretical framework’ is defined. Indeed, it could be argued that the necessity of a theory is a remnant from the times in which qualitative research was not as well accepted as it is today. In general, any research design that is inductive in nature and attempts to develop theory would be at a loss. We certainly would not want to eliminate multiple traditions of research from the Journal of Science Teacher Education .

Harry Wolcott’s discussion about validity in qualitative research (Wolcott, 1990 ) is quite explicit about the lack of theory or necessity of theory in driving qualitative ethnography. Interestingly, he even rejects the idea of validity as being a necessary criterion in qualitative research. Additionally, Bogdan and Biklen ( 1982 ) emphasize the importance of qualitative researchers “bracketing” (i.e., masking or trying to forget) their a priori theories so that it does not influence the collection of data or any meanings assigned to data during an investigation. Similar discussions about how qualitative research differs from quantitative research with respect to the necessity of theory guiding the research have been advanced by many others (e.g., Becker, 1970 ; Bogdan & Biklen, 1982 ; Erickson, 1986 ; Krathwohl, 2009 ; Rist, 1977 ; among others). Perhaps, Peshkin ( 1993 , p. 23) put it best when he expressed his concern that “Research that is not theory driven, hypothesis testing, or generalization producing may be dismissed as deficient or worse.” Again, the key point is that qualitative research is as valuable and can contribute as much to our knowledge of teaching and learning as quantitative research.

There is little doubt that qualitative researchers often invoke theory when analyzing the data they have collected or try to place their findings within the context of the existing literature. And, as stated at the beginning of this editorial, different research paradigms have large overarching theories about how one comes to know about the world. However, this is not the same thing has using a theory as a framework for the design of an investigation from the stating of research questions to developing a design to answer the research questions.

It is quite possible that you may be thinking that this editorial about the meaning of a theoretical framework is too theoretical. Trust us in believing that there is a very practical reason for us addressing this issue. At the beginning of the editorial we talked about the lack of a theoretical framework being the second most common reason for manuscripts being rejected for publication in the Journal of Science Teacher Education . Additionally, we mentioned that this is a common reason for manuscripts being rejected by other prominent journals in science education, and education in general. Consequently, it is of critical importance that we, as a community, are clear about the meaning of a theoretical framework and its use. It is especially important that our authors, reviewers, associate editors, and we as Editors of the journal are clear on this matter. Let us not fail to mention that most of us are advising Ph.D. students in the conceptualization of their dissertations. This issue is not new. In 1992, the editorial board of the Journal of Research in Science Teaching was considering the claim, by some, that qualitative research was not being evaluated fairly for publication relative to quantitative research. In their analysis of the relative success of publication for quantitative and qualitative research, Wandersee and Demastes ( 1992 , p. 1005) noted that reviewers often noted, “The manuscript had a weak theoretical basis” when reviewing qualitative research.

Theoretical frameworks are critically important to all of our work, quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. All research articles should have a valid theoretical framework to justify the importance and significance of the work. However, we should not live in fear, as the doctoral student, of not having a theoretical framework, when we actually have such, because an Editor, reviewer, or Major Professor is using any unduly restrictive and outdated meaning for what constitutes a theoretical framework.

Becker, H. (1970). Sociological work: Methods and substance . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Google Scholar

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (1982). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods . Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Erickson, F. (1986). Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 119–161). New York: Macmillan.

Jacob, E. (1987). Qualitative research traditions: A review. Review of Educational Research, 57 , 1–50.

Article Google Scholar

Krathwohl, D. R. (2009). Methods of educational and social science research . Logrove, IL: Waveland Press.

Lederman, N. G. (1986a). Relating teaching behavior and classroom climate to changes in students’ conceptions of the nature of science. Science Education, 70 (1), 3–19.

Lederman, N. G. (1986b). Students’ and teachers’ understanding of the nature of science: A reassessment. School Science and Mathematics, 86 , 91–99.

Lederman, N. G., & Druger, M. (1985). Classroom factors related to changes in students’ conceptions of the nature of science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 22 , 649–662.

Peshkin, A. (1993). The goodness of qualitative research. Educational Researcher, 22 (2), 24–30.

Rist, R. (1977). On the relations among educational research paradigms: From disdain to détente. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 8 , 42–49.

Smith, M. L. (1987). Publishing qualitative research. American Educational Research Journal, 24 (2), 173–183.

Tikunoff, W. J., Berliner, D. C., & Rist, R. C. (1975). Special study A: An enthnographic study of forty classrooms of the beginning teacher evaluation study known sample . Sacramento, CA: California Commission for Teacher Preparation and Licensing.

Wandersee, J. H., & Demastes, S. (1992). An analysis of the relative success of qualitative and quantitative manuscripts submitted to the Journal of Research in Science Teaching . Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 29 , 1005–1010.

Wolcott, H. F. (1990). On seeking, and rejecting, validity in qualitative research. In E. W. Eisner & A. Peshkin (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry in education (pp. 121–152). New York: Teachers College Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Chicago, IL, USA

Norman G. Lederman & Judith S. Lederman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Norman G. Lederman .

About this article

Lederman, N.G., Lederman, J.S. What Is A Theoretical Framework? A Practical Answer. J Sci Teacher Educ 26 , 593–597 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-015-9443-2

Download citation

Published : 30 November 2015

Issue Date : November 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-015-9443-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Find My Rep

You are here

Theoretical Frameworks in Qualitative Research

- Vincent A. Anfara, Jr. - University of Tennessee, Knoxville, USA

- Norma T. Mertz - University of Tennessee, Knoxville, USA

- Description

The Second Edition of Theoretical Frameworks in Qualitative Research brings together some of today’s leading qualitative researchers to discuss the frameworks behind their published qualitative studies. They share how they found and chose a theoretical framework, from what discipline the framework was drawn, what the framework posits, and how it influenced their study. Both novice and experienced qualitative researchers are able to learn first-hand from various contributors as they reflect on the process and decisions involved in completing their study. The book also provides background for beginning researchers about the nature of theoretical frameworks and their importance in qualitative research; about differences in perspective about the role of theoretical frameworks; and about how to find and use a theoretical framework.

Committee decision because of the depth of the qualitative information.

Not the right fit for analysis course

useful for all types of health care professions

Sample Materials & Chapters

For instructors, select a purchasing option.

- Electronic Order Options VitalSource Amazon Kindle Google Play eBooks.com Kobo

- Privacy Policy

Home » Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Theoretical Framework

Definition:

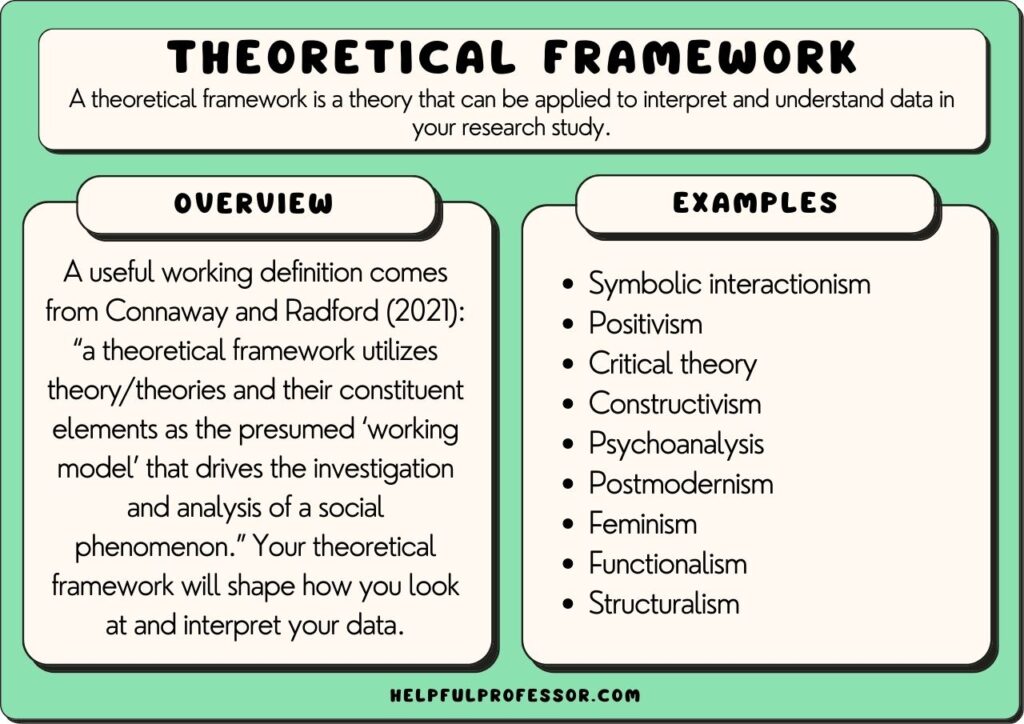

Theoretical framework refers to a set of concepts, theories, ideas , and assumptions that serve as a foundation for understanding a particular phenomenon or problem. It provides a conceptual framework that helps researchers to design and conduct their research, as well as to analyze and interpret their findings.

In research, a theoretical framework explains the relationship between various variables, identifies gaps in existing knowledge, and guides the development of research questions, hypotheses, and methodologies. It also helps to contextualize the research within a broader theoretical perspective, and can be used to guide the interpretation of results and the formulation of recommendations.

Types of Theoretical Framework

Types of Types of Theoretical Framework are as follows:

Conceptual Framework

This type of framework defines the key concepts and relationships between them. It helps to provide a theoretical foundation for a study or research project .

Deductive Framework

This type of framework starts with a general theory or hypothesis and then uses data to test and refine it. It is often used in quantitative research .

Inductive Framework

This type of framework starts with data and then develops a theory or hypothesis based on the patterns and themes that emerge from the data. It is often used in qualitative research .

Empirical Framework

This type of framework focuses on the collection and analysis of empirical data, such as surveys or experiments. It is often used in scientific research .

Normative Framework

This type of framework defines a set of norms or values that guide behavior or decision-making. It is often used in ethics and social sciences.

Explanatory Framework

This type of framework seeks to explain the underlying mechanisms or causes of a particular phenomenon or behavior. It is often used in psychology and social sciences.

Components of Theoretical Framework

The components of a theoretical framework include:

- Concepts : The basic building blocks of a theoretical framework. Concepts are abstract ideas or generalizations that represent objects, events, or phenomena.

- Variables : These are measurable and observable aspects of a concept. In a research context, variables can be manipulated or measured to test hypotheses.

- Assumptions : These are beliefs or statements that are taken for granted and are not tested in a study. They provide a starting point for developing hypotheses.

- Propositions : These are statements that explain the relationships between concepts and variables in a theoretical framework.

- Hypotheses : These are testable predictions that are derived from the theoretical framework. Hypotheses are used to guide data collection and analysis.

- Constructs : These are abstract concepts that cannot be directly measured but are inferred from observable variables. Constructs provide a way to understand complex phenomena.

- Models : These are simplified representations of reality that are used to explain, predict, or control a phenomenon.

How to Write Theoretical Framework

A theoretical framework is an essential part of any research study or paper, as it helps to provide a theoretical basis for the research and guide the analysis and interpretation of the data. Here are some steps to help you write a theoretical framework:

- Identify the key concepts and variables : Start by identifying the main concepts and variables that your research is exploring. These could include things like motivation, behavior, attitudes, or any other relevant concepts.

- Review relevant literature: Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature in your field to identify key theories and ideas that relate to your research. This will help you to understand the existing knowledge and theories that are relevant to your research and provide a basis for your theoretical framework.

- Develop a conceptual framework : Based on your literature review, develop a conceptual framework that outlines the key concepts and their relationships. This framework should provide a clear and concise overview of the theoretical perspective that underpins your research.

- Identify hypotheses and research questions: Based on your conceptual framework, identify the hypotheses and research questions that you want to test or explore in your research.

- Test your theoretical framework: Once you have developed your theoretical framework, test it by applying it to your research data. This will help you to identify any gaps or weaknesses in your framework and refine it as necessary.

- Write up your theoretical framework: Finally, write up your theoretical framework in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate terminology and referencing the relevant literature to support your arguments.

Theoretical Framework Examples

Here are some examples of theoretical frameworks:

- Social Learning Theory : This framework, developed by Albert Bandura, suggests that people learn from their environment, including the behaviors of others, and that behavior is influenced by both external and internal factors.

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs : Abraham Maslow proposed that human needs are arranged in a hierarchy, with basic physiological needs at the bottom, followed by safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization at the top. This framework has been used in various fields, including psychology and education.

- Ecological Systems Theory : This framework, developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner, suggests that a person’s development is influenced by the interaction between the individual and the various environments in which they live, such as family, school, and community.

- Feminist Theory: This framework examines how gender and power intersect to influence social, cultural, and political issues. It emphasizes the importance of understanding and challenging systems of oppression.

- Cognitive Behavioral Theory: This framework suggests that our thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes influence our behavior, and that changing our thought patterns can lead to changes in behavior and emotional responses.

- Attachment Theory: This framework examines the ways in which early relationships with caregivers shape our later relationships and attachment styles.

- Critical Race Theory : This framework examines how race intersects with other forms of social stratification and oppression to perpetuate inequality and discrimination.

When to Have A Theoretical Framework

Following are some situations When to Have A Theoretical Framework:

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research in any discipline, as it provides a foundation for understanding the research problem and guiding the research process.

- A theoretical framework is essential when conducting research on complex phenomena, as it helps to organize and structure the research questions, hypotheses, and findings.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when the research problem requires a deeper understanding of the underlying concepts and principles that govern the phenomenon being studied.

- A theoretical framework is particularly important when conducting research in social sciences, as it helps to explain the relationships between variables and provides a framework for testing hypotheses.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research in applied fields, such as engineering or medicine, as it helps to provide a theoretical basis for the development of new technologies or treatments.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research that seeks to address a specific gap in knowledge, as it helps to define the problem and identify potential solutions.

- A theoretical framework is also important when conducting research that involves the analysis of existing theories or concepts, as it helps to provide a framework for comparing and contrasting different theories and concepts.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research that seeks to make predictions or develop generalizations about a particular phenomenon, as it helps to provide a basis for evaluating the accuracy of these predictions or generalizations.

- Finally, a theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research that seeks to make a contribution to the field, as it helps to situate the research within the broader context of the discipline and identify its significance.

Purpose of Theoretical Framework

The purposes of a theoretical framework include:

- Providing a conceptual framework for the study: A theoretical framework helps researchers to define and clarify the concepts and variables of interest in their research. It enables researchers to develop a clear and concise definition of the problem, which in turn helps to guide the research process.

- Guiding the research design: A theoretical framework can guide the selection of research methods, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures. By outlining the key concepts and assumptions underlying the research questions, the theoretical framework can help researchers to identify the most appropriate research design for their study.

- Supporting the interpretation of research findings: A theoretical framework provides a framework for interpreting the research findings by helping researchers to make connections between their findings and existing theory. It enables researchers to identify the implications of their findings for theory development and to assess the generalizability of their findings.

- Enhancing the credibility of the research: A well-developed theoretical framework can enhance the credibility of the research by providing a strong theoretical foundation for the study. It demonstrates that the research is based on a solid understanding of the relevant theory and that the research questions are grounded in a clear conceptual framework.

- Facilitating communication and collaboration: A theoretical framework provides a common language and conceptual framework for researchers, enabling them to communicate and collaborate more effectively. It helps to ensure that everyone involved in the research is working towards the same goals and is using the same concepts and definitions.

Characteristics of Theoretical Framework

Some of the characteristics of a theoretical framework include:

- Conceptual clarity: The concepts used in the theoretical framework should be clearly defined and understood by all stakeholders.

- Logical coherence : The framework should be internally consistent, with each concept and assumption logically connected to the others.

- Empirical relevance: The framework should be based on empirical evidence and research findings.

- Parsimony : The framework should be as simple as possible, without sacrificing its ability to explain the phenomenon in question.

- Flexibility : The framework should be adaptable to new findings and insights.

- Testability : The framework should be testable through research, with clear hypotheses that can be falsified or supported by data.

- Applicability : The framework should be useful for practical applications, such as designing interventions or policies.

Advantages of Theoretical Framework

Here are some of the advantages of having a theoretical framework:

- Provides a clear direction : A theoretical framework helps researchers to identify the key concepts and variables they need to study and the relationships between them. This provides a clear direction for the research and helps researchers to focus their efforts and resources.

- Increases the validity of the research: A theoretical framework helps to ensure that the research is based on sound theoretical principles and concepts. This increases the validity of the research by ensuring that it is grounded in established knowledge and is not based on arbitrary assumptions.

- Enables comparisons between studies : A theoretical framework provides a common language and set of concepts that researchers can use to compare and contrast their findings. This helps to build a cumulative body of knowledge and allows researchers to identify patterns and trends across different studies.

- Helps to generate hypotheses: A theoretical framework provides a basis for generating hypotheses about the relationships between different concepts and variables. This can help to guide the research process and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Facilitates communication: A theoretical framework provides a common language and set of concepts that researchers can use to communicate their findings to other researchers and to the wider community. This makes it easier for others to understand the research and its implications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- Expert advice

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Methodology Previous Next

Use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks in qualitative research, helen elise green director of student education, university of leeds, uk.

Aim To debate the definition and use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks in qualitative research.

Background There is a paucity of literature to help the novice researcher to understand what theoretical and conceptual frameworks are and how they should be used. This paper acknowledges the interchangeable usage of these terms and researchers’ confusion about the differences between the two. It discusses how researchers have used theoretical and conceptual frameworks and the notion of conceptual models. Detail is given about how one researcher incorporated a conceptual framework throughout a research project, the purpose for doing so and how this led to a resultant conceptual model.

Review methods Concepts from Abbott ( 1988 ) and Witz ( 1992 ) were used to provide a framework for research involving two case study sites. The framework was used to determine research questions and give direction to interviews and discussions to focus the research.

Discussion Some research methods do not overtly use a theoretical framework or conceptual framework in their design, but this is implicit and underpins the method design, for example in grounded theory. Other qualitative methods use one or the other to frame the design of a research project or to explain the outcomes. An example is given of how a conceptual framework was used throughout a research project.

Conclusion Theoretical and conceptual frameworks are terms that are regularly used in research but rarely explained. Textbooks should discuss what they are and how they can be used, so novice researchers understand how they can help with research design.

Implications for practice/research Theoretical and conceptual frameworks need to be more clearly understood by researchers and correct terminology used to ensure clarity for novice researchers.

Nurse Researcher . 21, 6, 34-38. doi: 10.7748/nr.21.6.34.e1252

This article has been subject to double blind peer review

None declared

Received: 22 May 2013

Accepted: 28 August 2013

Theoretical framework - conceptual framework - case study - conceptual model - qualitative research - research design - case study research.

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

25 July 2014 / Vol 21 issue 6

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks in qualitative research

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks in qualitative research

Affiliation.

- 1 University of Leeds, UK.

- PMID: 25059086

- DOI: 10.7748/nr.21.6.34.e1252

Aim: To debate the definition and use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks in qualitative research.

Background: There is a paucity of literature to help the novice researcher to understand what theoretical and conceptual frameworks are and how they should be used. This paper acknowledges the interchangeable usage of these terms and researchers' confusion about the differences between the two. It discusses how researchers have used theoretical and conceptual frameworks and the notion of conceptual models. Detail is given about how one researcher incorporated a conceptual framework throughout a research project, the purpose for doing so and how this led to a resultant conceptual model.

Review methods: Concepts from Abbott (1988) and Witz ( 1992 ) were used to provide a framework for research involving two case study sites. The framework was used to determine research questions and give direction to interviews and discussions to focus the research.

Discussion: Some research methods do not overtly use a theoretical framework or conceptual framework in their design, but this is implicit and underpins the method design, for example in grounded theory. Other qualitative methods use one or the other to frame the design of a research project or to explain the outcomes. An example is given of how a conceptual framework was used throughout a research project.

Conclusion: Theoretical and conceptual frameworks are terms that are regularly used in research but rarely explained. Textbooks should discuss what they are and how they can be used, so novice researchers understand how they can help with research design.

Implications for practice/research: Theoretical and conceptual frameworks need to be more clearly understood by researchers and correct terminology used to ensure clarity for novice researchers.

Keywords: Theoretical framework; case study; case study research.; conceptual framework; conceptual model; qualitative research; research design.

- Nursing Research / organization & administration*

- Qualitative Research*

- Research Design

Examples of Theoretical Framework in Qualitative Research

Theoretical framework, also known as a theoretical standpoint, is the foundation of a qualitative study. It guides researchers to analyze data and helps them interpret results. The theoretical framework is a leading idea in a qualitative paper, and it helps shape the research plan.

What is a Theory?

It is a set of ideas that explain the relationship among variables in a cause-effect relationship. It guides researchers to make inferences about results or answer a research question.

How Does a Theoretical Framework in a Qualitative Study?

In general, the theoretical framework presents assumptions about relationships among concepts in theory. It is then applied to the study to explain certain phenomena.

A theoretical framework in qualitative studies is usually based on an existing theory or theories. A proposed theoretical framework should be relevant to the study’s goals and objectives.

Theoretical frameworks can be presented in different ways, including visual models or diagrams used to illustrate relationships among concepts.

A theoretical framework is flexible. It can change as the study progresses, depending on the data collected. Researchers then check if their assumptions are correct, refine the framework based on results, or refine it as they go along the way.

A theoretical framework addresses three key questions:

- What do we think or feel about the phenomenon being studied?

- Do we seek to explain, describe, interpret, critique, support, or read?

- What might be the consequences of doing such work?

A theoretical framework is a type of theory that links the data and the subject of study.

Some examples of theoretical frameworks in qualitative research are:

Grounded Theory Approach

This type of inquiry uses emergent theories during data collection and focuses more on discovery rather than explanation.

For example, a researcher might start by asking: “What is the experience of early motherhood like in a particular culture?”

In this case, the grounded theory approach would guide you to collect interviews from mothers and then analyze data inductively to construct theories that emerge from the collected data.

The grounded theory does not try to explain results. It only focuses on describing the phenomenon in question.

Key assumptions of this approach are:

- The theory is created during the research process

- Theory development is continuous

- Theoretical sensitivity is the basis upon which a framework is built

- The theory can explain something that would otherwise be unknown

Participatory Action Research

This inquiry focuses on people too, who are actively involved in research. The participants also have a say in directing the inquiry to address their needs.

The main assumptions in this approach are:

- Knowledge is developed through collaboration

- Collaboration requires community involvement

- The concept of power is acknowledged

- There’s no predetermined outcome

- Knowledge is both theoretical and practical

An example of participatory action research for a non-profit organization is to involve community members in the review of policies that affect them.

Critical Theory Approach

This framework helps researchers consider power relations within a society and emphasizes how access, voice, and representation are central to a study.

For example, the researcher might ask: “How have the effects of colonization changed the role of women in this culture?”

Here, the critical theory would inform your theoretical framework. This theory helps you explore power dynamics and their relationship to the subject of your study.

The critical theory framework will help you pay attention to the following:

- The intersection of various forms of oppression and power relations in a society

- Examining the influence of other structures such as capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy

- The relationship between structural forces and individual behavior

- Studying the role of knowledge and how it is produced

- How dominant discourses silence people

- The significance of social action

Driving Force Approach

This framework helps you explore the motives behind people’s actions and decisions. It aims to explain why something happens.

For example, the researcher might pose the question: “Why do African-American girls experience emergency room care differently than their Caucasian peers?”

The driving force’s approach would guide you to explore the motives behind people’s actions, which helps you answer this research question.

This approach taps into the following:

- The motivation that drives people to behave in a certain way

- Assumptions about human nature and the importance of individual action

- Use of case studies that are drawn from small samples

- Comparing different situations to see which factors have the greatest influence on decisions or actions

Semiotic Approach

This type of inquiry uses symbols and signs to help you understand how people construct meanings. It focuses on the processes through which meaning is influenced by social context.

For instance, the research question could be: “How does this culture define success?”

The semiotic approach helps you explore how symbols are used to construct meaning and how meaning is influenced by cultural context.

Researchers use this framework to determine:

- The use of signs and symbols

- Interpretative repertoires – the language people use to describe their experiences

- Discourses – the socially shared set of values, assumptions, and expectations at play in your study

- Conceptual metaphors – comparisons that people make with ideas or objects

- Cultural models – the shared understandings that link people to a particular cultural group

Phenomenological Approach

It focuses on subjective experiences, feelings, and thoughts. The goal is to understand the meaning people make of their lived experiences.

For example, the researcher might ask: “What is it like to go blind?”

This inquiry would utilize a phenomenological approach to guide your research process.

This framework seeks to examine:

- The unique experiences of the individual/group you are studying

- The influence of social and cultural factors on people’s beliefs, feelings, and behaviors

- The meaning people make of their experiences

- How people describe their own experiences

Transcendental Approach Framework

It is used to explore the “true” or universal aspects of human nature that exist independent of social context. It is a form of philosophical inquiry.

In the example above, the researcher might ask: “Is going blind psychologically devastating?”

This type of framework would help you explore the “fundamental,” universal aspects of human nature. The researcher focuses on broad, conceptual questions about human nature.

Feminist Approach

This framework helps researchers consider how women are portrayed and treated within society.

An example of a research problem would be: “How does this society define a ‘real man’?”

In this case, the feminist approach would guide you to explore how women are portrayed and treated within society.

Symbolic Interactionism Framework

According to this framework, the meaning of a situation for an individual is influenced by social interaction.

For example, consider the following research question: “What is a ‘high status’ job in this culture?”

The symbolic interactionist approach would guide you to explore how individuals define and negotiate their status within a culture, which helps you answer this research question.

Functionalism Framework

This approach focuses on how institutions, objects, and behaviors are interconnected within a culture.

For example, the researcher could pose the question: “How does this society keep its history alive?”

The functionalist framework would guide this research question. It helps you explore how institutions, objects, and behaviors are interconnected for this culture.

Postmodern Approach

In this framework, knowledge is fluid, and there are no absolute truths. It challenges traditional concepts of hierarchy, power, and knowledge.

For example, you might pose the question: “How do cultural norms construct gender in this society?”

The postmodern approach would guide you to explore how knowledge is fluid, and there are no absolute truths.

This approach is fluid, so the researcher is free to explore any topic they are interested in. It does not adhere to a specific set of guidelines. Instead, the researcher is free to explore any topic they are interested in.

The researcher is free to pose broad, open-ended questions that focus on the unique characteristics of their study.

Marxist Framework

This framework looks at how class, race, and gender influence the way people live.

For example, a research question could be: “What is the meaning of ‘success in this culture for a female business executive?”

In this case, the Marxist framework would help you explore how class, race, and gender influence the way people live. This framework would help you consider the unique experiences of a female business executive.

Considering the impact of race, class, and gender on people’s lives within this society would guide your research process.

Constructionist Framework

This approach helps you analyze language and meaning-making systems. It focuses on the process through which social structures are created and maintained.

For instance, if your research study is about the youth’s understanding of their rights, you might ask: “What is considered ‘childhood’ in this culture?”

The constructionist framework would guide you to explore how social structures are created and maintained. This understanding will help you answer the research question.

When using the constructionist framework, your research study is more of a process than a result. The constructionist approach focuses on the process through which social structures are created and maintained. It helps the researcher consider language and meaning-making systems.

Emergent Design

The emergent design focuses on collaborative research. It is used when the researcher wants to bring multiple perspectives into their study and has little control over the research process.

An example of a question you could ask is: “What makes a marriage successful?”

In this case, in an emergent design, you would be collaborating with multiple people or participants to answer this question.

Emergent design framework makes it easier for you to invite participants to share their insights and opinions during your study. This approach will help you involve more people in your research process. It also enables you to gain a deeper understanding of a specific topic.

Individualist Approach

It works by identifying, understanding, and describing the behavior of individuals within a society.

For example, you might develop a research question such as: “How do people in this culture experience illness daily?”

The individualist approach would help you explore the behavior of individuals within the society.

This framework is best used when the researcher needs a deep understanding of an individual’s experience. It is helpful for exploratory research where you are noticing patterns within people’s behavior.

Radical Framework/Subversive Methods

The radical approach is focused on social change and liberation. The research method uses a major research question to engage in a political project.

For example, you might ask: “How does this culture perpetuate inequality?”

In the radical framework/subversive methods, you would engage in a political project to answer the research question.

The main difference between the radical approach and other frameworks is that you must form a major research question for this approach.

Using the radical framework also helps the researcher ensure that people have a voice in their studies.

Critical Race Approach

This approach helps understand and challenge racism through the lens of law. In this framework, you analyze how laws and other societal structures impact people from different backgrounds.

You might ask: “What are the barriers to education for people of color?”

In this case, the critical race approach will help you explore how laws and other societal structures impact people of different backgrounds.

If you are interested in the intersection of law and social justice, this approach may be for you. It helps you understand how the law works and enables you to develop a productive way to challenge racism.

Categories of Theoretical Frameworks

- Theoretical orientation: it provides the conceptual basis for your study. It guides you through answering what’s important and why while also helping you determine which data are relevant.

- Philosophical perspective: this helps researchers address ethical considerations during their studies. For example, political or social justice orientations are helpful in that they help researchers consider the effects of their research on society at large.

- The ontological perspective focuses on what is real and how it might be depicted in a study. Does it address questions like, ‘What kinds of things exist? What is our role as researchers?

- Theoretical paradigm: this provides the structure for directing your research. It highlights how you determine what is relevant and influences how you need to do your work.

The Importance of Theoretical Frameworks in Qualitative Research

- A theoretical framework is critical because it guides you through answering research questions and synthesizing your data.

- It influences how you determine what is relevant and how you locate, select, analyze, and interpret your data.

- It also helps to determine the worth of your study, and it helps to give a structure for guiding your research.

- A theoretical framework also provides a lens that helps you interpret your findings.

- It helps you assess the validity and credibility of your data. An example is: studying a phenomenon that impacted people from different cultures. You might look at the various theoretical orientations to help you interpret your findings.

- Theoretical frameworks are analogous to maps that help researchers trace out the terrain of their research. Without a map, you would not know where to go and thus, misguide your research. Likewise, theoretical frameworks help researchers stay on track throughout the research process.

- A good theoretical framework guides you to ask the right questions. For example, knowing which theoretical perspective is most appropriate for your research will help you choose the right research questions and thus, make your inquiry more focused.

Theoretical Framework Vs. Conceptual Framework.

It’s important to note that theoretical frameworks and conceptual frameworks are not synonymous. Below are the main differences between the two:

How to Develop a Strong Theoretical Framework for Your Study

When reaching the theoretical framework section of your proposal, you might feel a sense of panic. It’s common to feel overwhelmed by the theoretical frameworks that are available to you. The following are the steps you can take to develop a theoretical framework for your study:

- Identify what you already know. It’s helpful to reflect on the knowledge that you already possess about your topic. Existing knowledge can provide the basis for developing a coherent theoretical framework.

- Choose the theoretical perspective that will provide the best framework for your study. It’s important to consider which theoretical perspective is best suited for your research topic. For example, if you were interested in conducting a critical ethnography, you would use the critical theory perspective.

- Develop your framework by synthesizing different theoretical perspectives. When developing your framework, make sure to draw from multiple theoretical perspectives and integrate their unique contributions.

- Make sure your framework is relevant to your research topic . For example, if you were studying prison reform, a humanistic perspective might not be appropriate. Instead, symbolic Interactionism would be more relevant.

- Use a theoretical perspective that you feel comfortable with and facilitates understanding of the field you are studying.

- Address how your theoretical framework will help guide your research within that methodology.

Sometimes a research question is theoretical. Other times it can be a practical one. To use a theoretical framework means to engage in the way of thinking about the topic under study. It is a way to develop a meaningful question about something which can help you better understand it.

Theoretical frameworks are a set of assumptions based on a theoretical perspective. At its best, a theoretical framework guides you through answering your research questions. Choosing an appropriate framework for your study will help you ask the right questions and make more informed decisions.

A theoretical framework will help you explore your research topic from different angles. It must be relevant to your research topic. The theoretical framework you choose must be able to stand up to scrutiny, so it’s best to use well-known and established frameworks.

I ‘m a freelance content and SEO writer with a passion for finding the perfect combination of words to capture attention and express a message . I create catchy, SEO-friendly content for websites, blogs, articles, and social media. My experience spans many industries, including health and wellness, technology, education, business, and lifestyle. My clients appreciate my ability to craft compelling stories that engage their target audience, but also help to improve their website’s search engine rankings. I’m also an avid learner and stay up to date on the latest SEO trends. I enjoy exploring new places and reading up on the latest marketing and SEO strategies in my free time.

Similar Posts

Participial Phrase: Definition and Examples

Participial phrases are words, phrases, or clauses used in a sentence to modify the subject or object. A participial phrase can also be known as a participle phrase. These phrases are used as modifiers and can be recognized by a few common traits: They usually begin with a present or past participle, but there are…

How to Write the Results Section of a Lab Report

Overview The results section of a lab report is one of the sections in your paper that will be most scrutinized. If you are looking to separate yourself from other students in your class, take care in developing this portion. A common mistake among younger students is writing too much information at once. Keep in…

How to Summarize a Chapter, Story, and Essay

A summary is a concise and accurate explanation of the main idea of a text. It should be brief, but it must not leave out any important details. A good summary will tell more than what has been read while also providing the reader with an understanding of the author’s intention. This article will discuss…

How to Write a Term Paper in APA Format-With Examples

Overview APA stands for American Psychological Association. It is used by most educational institutions in the US and Canada. To keep your term paper organized, it is necessary to follow proper citation styles like the APA style. We will explore more about APA referencing style. The APA style is primarily used in the social sciences…

Symbolic Interactionism- Definition, Theorists, & Examples

Symbolic interactionism suggests that people are constantly trying to figure out how their behavior will impact the thoughts and emotions of others. We’ll delve more into this theory in this guide; you’ll be a professor in symbolic interactionalism by the time you’re done reading!

How to Write a Chemistry Lab Report

Chemistry is the study of matter and how it interacts with other substances. Chemistry Laboratory Reports are often used to analyze chemical reactions, test hypotheses, or explore scientific questions. A Chemistry Lab Report can be written using different formats depending on the type of experiment being conducted. For qualitative experiments (i.e., those not involving exact…

- Correspondence

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2013

Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research

- Nicola K Gale 1 ,

- Gemma Heath 2 ,

- Elaine Cameron 3 ,

- Sabina Rashid 4 &

- Sabi Redwood 2

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 13 , Article number: 117 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

518k Accesses

4724 Citations

100 Altmetric

Metrics details

The Framework Method is becoming an increasingly popular approach to the management and analysis of qualitative data in health research. However, there is confusion about its potential application and limitations.

The article discusses when it is appropriate to adopt the Framework Method and explains the procedure for using it in multi-disciplinary health research teams, or those that involve clinicians, patients and lay people. The stages of the method are illustrated using examples from a published study.

Used effectively, with the leadership of an experienced qualitative researcher, the Framework Method is a systematic and flexible approach to analysing qualitative data and is appropriate for use in research teams even where not all members have previous experience of conducting qualitative research.