Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Steps in Developing a Research Proposal

Learning objectives.

- Identify the steps in developing a research proposal.

- Choose a topic and formulate a research question and working thesis.

- Develop a research proposal.

Writing a good research paper takes time, thought, and effort. Although this assignment is challenging, it is manageable. Focusing on one step at a time will help you develop a thoughtful, informative, well-supported research paper.

Your first step is to choose a topic and then to develop research questions, a working thesis, and a written research proposal. Set aside adequate time for this part of the process. Fully exploring ideas will help you build a solid foundation for your paper.

Choosing a Topic

When you choose a topic for a research paper, you are making a major commitment. Your choice will help determine whether you enjoy the lengthy process of research and writing—and whether your final paper fulfills the assignment requirements. If you choose your topic hastily, you may later find it difficult to work with your topic. By taking your time and choosing carefully, you can ensure that this assignment is not only challenging but also rewarding.

Writers understand the importance of choosing a topic that fulfills the assignment requirements and fits the assignment’s purpose and audience. (For more information about purpose and audience, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” .) Choosing a topic that interests you is also crucial. You instructor may provide a list of suggested topics or ask that you develop a topic on your own. In either case, try to identify topics that genuinely interest you.

After identifying potential topic ideas, you will need to evaluate your ideas and choose one topic to pursue. Will you be able to find enough information about the topic? Can you develop a paper about this topic that presents and supports your original ideas? Is the topic too broad or too narrow for the scope of the assignment? If so, can you modify it so it is more manageable? You will ask these questions during this preliminary phase of the research process.

Identifying Potential Topics

Sometimes, your instructor may provide a list of suggested topics. If so, you may benefit from identifying several possibilities before committing to one idea. It is important to know how to narrow down your ideas into a concise, manageable thesis. You may also use the list as a starting point to help you identify additional, related topics. Discussing your ideas with your instructor will help ensure that you choose a manageable topic that fits the requirements of the assignment.

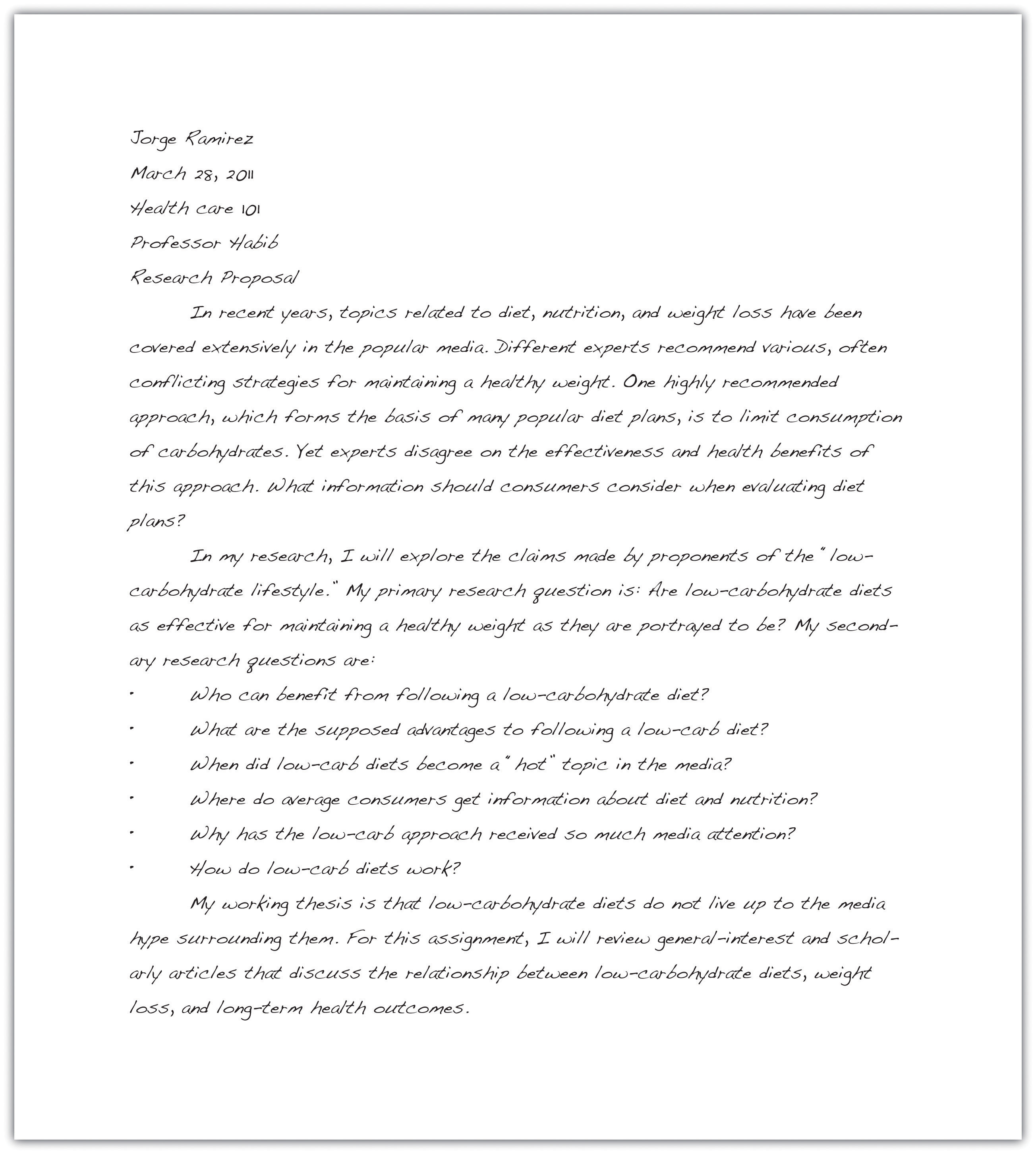

In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Jorge, who is studying health care administration, as he prepares a research paper. You will also plan, research, and draft your own research paper.

Jorge was assigned to write a research paper on health and the media for an introductory course in health care. Although a general topic was selected for the students, Jorge had to decide which specific issues interested him. He brainstormed a list of possibilities.

If you are writing a research paper for a specialized course, look back through your notes and course activities. Identify reading assignments and class discussions that especially engaged you. Doing so can help you identify topics to pursue.

- Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) in the news

- Sexual education programs

- Hollywood and eating disorders

- Americans’ access to public health information

- Media portrayal of health care reform bill

- Depictions of drugs on television

- The effect of the Internet on mental health

- Popularized diets (such as low-carbohydrate diets)

- Fear of pandemics (bird flu, HINI, SARS)

- Electronic entertainment and obesity

- Advertisements for prescription drugs

- Public education and disease prevention

Set a timer for five minutes. Use brainstorming or idea mapping to create a list of topics you would be interested in researching for a paper about the influence of the Internet on social networking. Do you closely follow the media coverage of a particular website, such as Twitter? Would you like to learn more about a certain industry, such as online dating? Which social networking sites do you and your friends use? List as many ideas related to this topic as you can.

Narrowing Your Topic

Once you have a list of potential topics, you will need to choose one as the focus of your essay. You will also need to narrow your topic. Most writers find that the topics they listed during brainstorming or idea mapping are broad—too broad for the scope of the assignment. Working with an overly broad topic, such as sexual education programs or popularized diets, can be frustrating and overwhelming. Each topic has so many facets that it would be impossible to cover them all in a college research paper. However, more specific choices, such as the pros and cons of sexual education in kids’ television programs or the physical effects of the South Beach diet, are specific enough to write about without being too narrow to sustain an entire research paper.

A good research paper provides focused, in-depth information and analysis. If your topic is too broad, you will find it difficult to do more than skim the surface when you research it and write about it. Narrowing your focus is essential to making your topic manageable. To narrow your focus, explore your topic in writing, conduct preliminary research, and discuss both the topic and the research with others.

Exploring Your Topic in Writing

“How am I supposed to narrow my topic when I haven’t even begun researching yet?” In fact, you may already know more than you realize. Review your list and identify your top two or three topics. Set aside some time to explore each one through freewriting. (For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .) Simply taking the time to focus on your topic may yield fresh angles.

Jorge knew that he was especially interested in the topic of diet fads, but he also knew that it was much too broad for his assignment. He used freewriting to explore his thoughts so he could narrow his topic. Read Jorge’s ideas.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Another way writers may focus a topic is to conduct preliminary research . Like freewriting, exploratory reading can help you identify interesting angles. Surfing the web and browsing through newspaper and magazine articles are good ways to start. Find out what people are saying about your topic on blogs and online discussion groups. Discussing your topic with others can also inspire you. Talk about your ideas with your classmates, your friends, or your instructor.

Jorge’s freewriting exercise helped him realize that the assigned topic of health and the media intersected with a few of his interests—diet, nutrition, and obesity. Preliminary online research and discussions with his classmates strengthened his impression that many people are confused or misled by media coverage of these subjects.

Jorge decided to focus his paper on a topic that had garnered a great deal of media attention—low-carbohydrate diets. He wanted to find out whether low-carbohydrate diets were as effective as their proponents claimed.

Writing at Work

At work, you may need to research a topic quickly to find general information. This information can be useful in understanding trends in a given industry or generating competition. For example, a company may research a competitor’s prices and use the information when pricing their own product. You may find it useful to skim a variety of reliable sources and take notes on your findings.

The reliability of online sources varies greatly. In this exploratory phase of your research, you do not need to evaluate sources as closely as you will later. However, use common sense as you refine your paper topic. If you read a fascinating blog comment that gives you a new idea for your paper, be sure to check out other, more reliable sources as well to make sure the idea is worth pursuing.

Review the list of topics you created in Note 11.18 “Exercise 1” and identify two or three topics you would like to explore further. For each of these topics, spend five to ten minutes writing about the topic without stopping. Then review your writing to identify possible areas of focus.

Set aside time to conduct preliminary research about your potential topics. Then choose a topic to pursue for your research paper.

Collaboration

Please share your topic list with a classmate. Select one or two topics on his or her list that you would like to learn more about and return it to him or her. Discuss why you found the topics interesting, and learn which of your topics your classmate selected and why.

A Plan for Research

Your freewriting and preliminary research have helped you choose a focused, manageable topic for your research paper. To work with your topic successfully, you will need to determine what exactly you want to learn about it—and later, what you want to say about it. Before you begin conducting in-depth research, you will further define your focus by developing a research question , a working thesis, and a research proposal.

Formulating a Research Question

In forming a research question, you are setting a goal for your research. Your main research question should be substantial enough to form the guiding principle of your paper—but focused enough to guide your research. A strong research question requires you not only to find information but also to put together different pieces of information, interpret and analyze them, and figure out what you think. As you consider potential research questions, ask yourself whether they would be too hard or too easy to answer.

To determine your research question, review the freewriting you completed earlier. Skim through books, articles, and websites and list the questions you have. (You may wish to use the 5WH strategy to help you formulate questions. See Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” for more information about 5WH questions.) Include simple, factual questions and more complex questions that would require analysis and interpretation. Determine your main question—the primary focus of your paper—and several subquestions that you will need to research to answer your main question.

Here are the research questions Jorge will use to focus his research. Notice that his main research question has no obvious, straightforward answer. Jorge will need to research his subquestions, which address narrower topics, to answer his main question.

Using the topic you selected in Note 11.24 “Exercise 2” , write your main research question and at least four to five subquestions. Check that your main research question is appropriately complex for your assignment.

Constructing a Working ThesIs

A working thesis concisely states a writer’s initial answer to the main research question. It does not merely state a fact or present a subjective opinion. Instead, it expresses a debatable idea or claim that you hope to prove through additional research. Your working thesis is called a working thesis for a reason—it is subject to change. As you learn more about your topic, you may change your thinking in light of your research findings. Let your working thesis serve as a guide to your research, but do not be afraid to modify it based on what you learn.

Jorge began his research with a strong point of view based on his preliminary writing and research. Read his working thesis statement, which presents the point he will argue. Notice how it states Jorge’s tentative answer to his research question.

One way to determine your working thesis is to consider how you would complete sentences such as I believe or My opinion is . However, keep in mind that academic writing generally does not use first-person pronouns. These statements are useful starting points, but formal research papers use an objective voice.

Write a working thesis statement that presents your preliminary answer to the research question you wrote in Note 11.27 “Exercise 3” . Check that your working thesis statement presents an idea or claim that could be supported or refuted by evidence from research.

Creating a Research Proposal

A research proposal is a brief document—no more than one typed page—that summarizes the preliminary work you have completed. Your purpose in writing it is to formalize your plan for research and present it to your instructor for feedback. In your research proposal, you will present your main research question, related subquestions, and working thesis. You will also briefly discuss the value of researching this topic and indicate how you plan to gather information.

When Jorge began drafting his research proposal, he realized that he had already created most of the pieces he needed. However, he knew he also had to explain how his research would be relevant to other future health care professionals. In addition, he wanted to form a general plan for doing the research and identifying potentially useful sources. Read Jorge’s research proposal.

Before you begin a new project at work, you may have to develop a project summary document that states the purpose of the project, explains why it would be a wise use of company resources, and briefly outlines the steps involved in completing the project. This type of document is similar to a research proposal. Both documents define and limit a project, explain its value, discuss how to proceed, and identify what resources you will use.

Writing Your Own Research Proposal

Now you may write your own research proposal, if you have not done so already. Follow the guidelines provided in this lesson.

Key Takeaways

- Developing a research proposal involves the following preliminary steps: identifying potential ideas, choosing ideas to explore further, choosing and narrowing a topic, formulating a research question, and developing a working thesis.

- A good topic for a research paper interests the writer and fulfills the requirements of the assignment.

- Defining and narrowing a topic helps writers conduct focused, in-depth research.

- Writers conduct preliminary research to identify possible topics and research questions and to develop a working thesis.

- A good research question interests readers, is neither too broad nor too narrow, and has no obvious answer.

- A good working thesis expresses a debatable idea or claim that can be supported with evidence from research.

- Writers create a research proposal to present their topic, main research question, subquestions, and working thesis to an instructor for approval or feedback.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

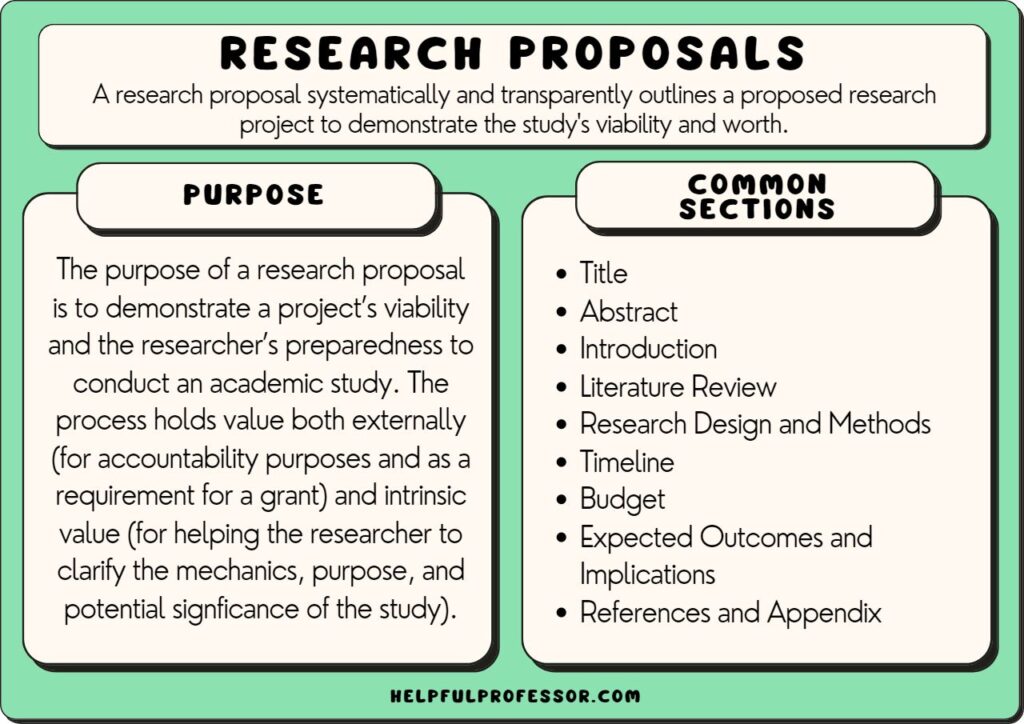

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

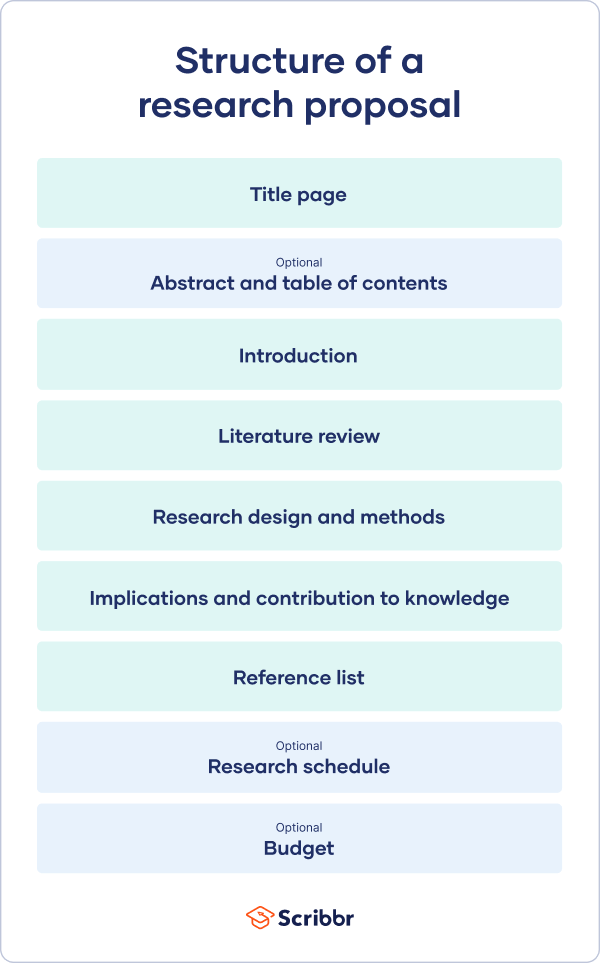

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Advanced Research Methods

- Writing a Research Proposal

- What Is Research?

- Library Research

What Is a Research Proposal?

Reference books.

- Writing the Research Paper

- Presenting the Research Paper

When applying for a research grant or scholarship, or, just before you start a major research project, you may be asked to write a preliminary document that includes basic information about your future research. This is the information that is usually needed in your proposal:

- The topic and goal of the research project.

- The kind of result expected from the research.

- The theory or framework in which the research will be done and presented.

- What kind of methods will be used (statistical, empirical, etc.).

- Short reference on the preliminary scholarship and why your research project is needed; how will it continue/justify/disprove the previous scholarship.

- How much will the research project cost; how will it be budgeted (what for the money will be spent).

- Why is it you who can do this research and not somebody else.

Most agencies that offer scholarships or grants provide information about the required format of the proposal. It may include filling out templates, types of information they need, suggested/maximum length of the proposal, etc.

Research proposal formats vary depending on the size of the planned research, the number of participants, the discipline, the characteristics of the research, etc. The following outline assumes an individual researcher. This is just a SAMPLE; several other ways are equally good and can be successful. If possible, discuss your research proposal with an expert in writing, a professor, your colleague, another student who already wrote successful proposals, etc.

Author, author's affiliation

Introduction:

- Explain the topic and why you chose it. If possible explain your goal/outcome of the research . How much time you need to complete the research?

Previous scholarship:

- Give a brief summary of previous scholarship and explain why your topic and goals are important.

- Relate your planned research to previous scholarship. What will your research add to our knowledge of the topic.

Specific issues to be investigated:

- Break down the main topic into smaller research questions. List them one by one and explain why these questions need to be investigated. Relate them to previous scholarship.

- Include your hypothesis into the descriptions of the detailed research issues if you have one. Explain why it is important to justify your hypothesis.

Methodology:

- This part depends of the methods conducted in the research process. List the methods; explain how the results will be presented; how they will be assessed.

- Explain what kind of results will justify or disprove your hypothesis.

- Explain how much money you need.

- Explain the details of the budget (how much you want to spend for what).

Conclusion:

- Describe why your research is important.

References:

- List the sources you have used for writing the research proposal, including a few main citations of the preliminary scholarship.

- << Previous: Library Research

- Next: Writing the Research Paper >>

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 12:24 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/research-methods

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Here's What You Need to Understand About Research Methodology

Table of Contents

Research methodology involves a systematic and well-structured approach to conducting scholarly or scientific inquiries. Knowing the significance of research methodology and its different components is crucial as it serves as the basis for any study.

Typically, your research topic will start as a broad idea you want to investigate more thoroughly. Once you’ve identified a research problem and created research questions , you must choose the appropriate methodology and frameworks to address those questions effectively.

What is the definition of a research methodology?

Research methodology is the process or the way you intend to execute your study. The methodology section of a research paper outlines how you plan to conduct your study. It covers various steps such as collecting data, statistical analysis, observing participants, and other procedures involved in the research process

The methods section should give a description of the process that will convert your idea into a study. Additionally, the outcomes of your process must provide valid and reliable results resonant with the aims and objectives of your research. This thumb rule holds complete validity, no matter whether your paper has inclinations for qualitative or quantitative usage.

Studying research methods used in related studies can provide helpful insights and direction for your own research. Now easily discover papers related to your topic on SciSpace and utilize our AI research assistant, Copilot , to quickly review the methodologies applied in different papers.

The need for a good research methodology

While deciding on your approach towards your research, the reason or factors you weighed in choosing a particular problem and formulating a research topic need to be validated and explained. A research methodology helps you do exactly that. Moreover, a good research methodology lets you build your argument to validate your research work performed through various data collection methods, analytical methods, and other essential points.

Just imagine it as a strategy documented to provide an overview of what you intend to do.

While undertaking any research writing or performing the research itself, you may get drifted in not something of much importance. In such a case, a research methodology helps you to get back to your outlined work methodology.

A research methodology helps in keeping you accountable for your work. Additionally, it can help you evaluate whether your work is in sync with your original aims and objectives or not. Besides, a good research methodology enables you to navigate your research process smoothly and swiftly while providing effective planning to achieve your desired results.

What is the basic structure of a research methodology?

Usually, you must ensure to include the following stated aspects while deciding over the basic structure of your research methodology:

1. Your research procedure

Explain what research methods you’re going to use. Whether you intend to proceed with quantitative or qualitative, or a composite of both approaches, you need to state that explicitly. The option among the three depends on your research’s aim, objectives, and scope.

2. Provide the rationality behind your chosen approach

Based on logic and reason, let your readers know why you have chosen said research methodologies. Additionally, you have to build strong arguments supporting why your chosen research method is the best way to achieve the desired outcome.

3. Explain your mechanism

The mechanism encompasses the research methods or instruments you will use to develop your research methodology. It usually refers to your data collection methods. You can use interviews, surveys, physical questionnaires, etc., of the many available mechanisms as research methodology instruments. The data collection method is determined by the type of research and whether the data is quantitative data(includes numerical data) or qualitative data (perception, morale, etc.) Moreover, you need to put logical reasoning behind choosing a particular instrument.

4. Significance of outcomes

The results will be available once you have finished experimenting. However, you should also explain how you plan to use the data to interpret the findings. This section also aids in understanding the problem from within, breaking it down into pieces, and viewing the research problem from various perspectives.

5. Reader’s advice

Anything that you feel must be explained to spread more awareness among readers and focus groups must be included and described in detail. You should not just specify your research methodology on the assumption that a reader is aware of the topic.

All the relevant information that explains and simplifies your research paper must be included in the methodology section. If you are conducting your research in a non-traditional manner, give a logical justification and list its benefits.

6. Explain your sample space

Include information about the sample and sample space in the methodology section. The term "sample" refers to a smaller set of data that a researcher selects or chooses from a larger group of people or focus groups using a predetermined selection method. Let your readers know how you are going to distinguish between relevant and non-relevant samples. How you figured out those exact numbers to back your research methodology, i.e. the sample spacing of instruments, must be discussed thoroughly.

For example, if you are going to conduct a survey or interview, then by what procedure will you select the interviewees (or sample size in case of surveys), and how exactly will the interview or survey be conducted.

7. Challenges and limitations

This part, which is frequently assumed to be unnecessary, is actually very important. The challenges and limitations that your chosen strategy inherently possesses must be specified while you are conducting different types of research.

The importance of a good research methodology

You must have observed that all research papers, dissertations, or theses carry a chapter entirely dedicated to research methodology. This section helps maintain your credibility as a better interpreter of results rather than a manipulator.

A good research methodology always explains the procedure, data collection methods and techniques, aim, and scope of the research. In a research study, it leads to a well-organized, rationality-based approach, while the paper lacking it is often observed as messy or disorganized.

You should pay special attention to validating your chosen way towards the research methodology. This becomes extremely important in case you select an unconventional or a distinct method of execution.

Curating and developing a strong, effective research methodology can assist you in addressing a variety of situations, such as:

- When someone tries to duplicate or expand upon your research after few years.

- If a contradiction or conflict of facts occurs at a later time. This gives you the security you need to deal with these contradictions while still being able to defend your approach.

- Gaining a tactical approach in getting your research completed in time. Just ensure you are using the right approach while drafting your research methodology, and it can help you achieve your desired outcomes. Additionally, it provides a better explanation and understanding of the research question itself.

- Documenting the results so that the final outcome of the research stays as you intended it to be while starting.

Instruments you could use while writing a good research methodology

As a researcher, you must choose which tools or data collection methods that fit best in terms of the relevance of your research. This decision has to be wise.

There exists many research equipments or tools that you can use to carry out your research process. These are classified as:

a. Interviews (One-on-One or a Group)

An interview aimed to get your desired research outcomes can be undertaken in many different ways. For example, you can design your interview as structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. What sets them apart is the degree of formality in the questions. On the other hand, in a group interview, your aim should be to collect more opinions and group perceptions from the focus groups on a certain topic rather than looking out for some formal answers.

In surveys, you are in better control if you specifically draft the questions you seek the response for. For example, you may choose to include free-style questions that can be answered descriptively, or you may provide a multiple-choice type response for questions. Besides, you can also opt to choose both ways, deciding what suits your research process and purpose better.

c. Sample Groups

Similar to the group interviews, here, you can select a group of individuals and assign them a topic to discuss or freely express their opinions over that. You can simultaneously note down the answers and later draft them appropriately, deciding on the relevance of every response.

d. Observations

If your research domain is humanities or sociology, observations are the best-proven method to draw your research methodology. Of course, you can always include studying the spontaneous response of the participants towards a situation or conducting the same but in a more structured manner. A structured observation means putting the participants in a situation at a previously decided time and then studying their responses.

Of all the tools described above, it is you who should wisely choose the instruments and decide what’s the best fit for your research. You must not restrict yourself from multiple methods or a combination of a few instruments if appropriate in drafting a good research methodology.

Types of research methodology

A research methodology exists in various forms. Depending upon their approach, whether centered around words, numbers, or both, methodologies are distinguished as qualitative, quantitative, or an amalgamation of both.

1. Qualitative research methodology

When a research methodology primarily focuses on words and textual data, then it is generally referred to as qualitative research methodology. This type is usually preferred among researchers when the aim and scope of the research are mainly theoretical and explanatory.

The instruments used are observations, interviews, and sample groups. You can use this methodology if you are trying to study human behavior or response in some situations. Generally, qualitative research methodology is widely used in sociology, psychology, and other related domains.

2. Quantitative research methodology

If your research is majorly centered on data, figures, and stats, then analyzing these numerical data is often referred to as quantitative research methodology. You can use quantitative research methodology if your research requires you to validate or justify the obtained results.

In quantitative methods, surveys, tests, experiments, and evaluations of current databases can be advantageously used as instruments If your research involves testing some hypothesis, then use this methodology.

3. Amalgam methodology

As the name suggests, the amalgam methodology uses both quantitative and qualitative approaches. This methodology is used when a part of the research requires you to verify the facts and figures, whereas the other part demands you to discover the theoretical and explanatory nature of the research question.

The instruments for the amalgam methodology require you to conduct interviews and surveys, including tests and experiments. The outcome of this methodology can be insightful and valuable as it provides precise test results in line with theoretical explanations and reasoning.

The amalgam method, makes your work both factual and rational at the same time.

Final words: How to decide which is the best research methodology?

If you have kept your sincerity and awareness intact with the aims and scope of research well enough, you must have got an idea of which research methodology suits your work best.

Before deciding which research methodology answers your research question, you must invest significant time in reading and doing your homework for that. Taking references that yield relevant results should be your first approach to establishing a research methodology.

Moreover, you should never refrain from exploring other options. Before setting your work in stone, you must try all the available options as it explains why the choice of research methodology that you finally make is more appropriate than the other available options.

You should always go for a quantitative research methodology if your research requires gathering large amounts of data, figures, and statistics. This research methodology will provide you with results if your research paper involves the validation of some hypothesis.

Whereas, if you are looking for more explanations, reasons, opinions, and public perceptions around a theory, you must use qualitative research methodology.The choice of an appropriate research methodology ultimately depends on what you want to achieve through your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Research Methodology

1. how to write a research methodology.

You can always provide a separate section for research methodology where you should specify details about the methods and instruments used during the research, discussions on result analysis, including insights into the background information, and conveying the research limitations.

2. What are the types of research methodology?

There generally exists four types of research methodology i.e.

- Observation

- Experimental

- Derivational

3. What is the true meaning of research methodology?

The set of techniques or procedures followed to discover and analyze the information gathered to validate or justify a research outcome is generally called Research Methodology.

4. Where lies the importance of research methodology?

Your research methodology directly reflects the validity of your research outcomes and how well-informed your research work is. Moreover, it can help future researchers cite or refer to your research if they plan to use a similar research methodology.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Using AI for research: A beginner’s guide

Research Proposal: A step-by-step guide with template

Making sure your proposal is perfect will drastically improve your chances of landing a successful research position. Follow these steps.

There’s no doubt you have the most cutting-edge research idea to date, backed up by a solid methodology and a credible explanation proving its relevance! There are thousands of research ideas that could change the world with many new ideologies.

The truth is, none of this would matter without support. It can be daunting, challenging, and uncertain to secure funding for a research project. Even more so when it isn’t well-thought-out, outlined, and includes every detail.

An effective solution for presenting your project, or requesting funding, is to provide a research proposal to potential investors or financiers on your behalf.

It’s crucial to understand that making sure your proposal is perfect will drastically improve your chances of landing a successful research position. Your research proposal could result in the failure to study the research problem entirely if it is inadequately constructed or incomplete.

It is for this reason that we have created an excellent guide that covers everything you need to know about writing a research proposal, and includes helpful tips for presenting your proposal professionally and improving its likelihood of acceptance!

What Is a Research Proposal?

Generally, a research proposal is a well-crafted, formal document that provides a thorough explanation of what you plan to investigate. This includes a rationale for why it is worth investigating, as well as a method for investigating it.

Research proposal writing in the contemporary academic environment is a challenging undertaking given the constant shift in research methodology and a commitment to incorporating scientific breakthroughs.

An outline of the plan or roadmap for the study is the proposal, and once the proposal is complete, everything should be smooth sailing. It is still common for post-graduate evaluation panels and funding applications to submit substandard proposals.

By its very nature, the research proposal serves as a tool for convincing the supervisor, committee, or university that the proposed research fits within the scope of the program and is feasible when considering the time and resources available.

A research proposal should convince the person who is going to sanction your research, or put another way, you need to persuade them that your research idea is the best.

Obviously, if it does not convince them that it is reasonable and adequate, you will need to revise and submit it again. As a result, you will lose significant time, causing your research to be delayed or cut short, which is not good.

A good research proposal should have the following structure

A dissertation or thesis research proposal may take on a variety of forms depending on the university, but most generally a research proposal will include the following elements:

- Titles or title pages that give a description of the research

- Detailed explanation of the proposed research and its background

- Outline of the research project

- An overview of key research studies in the field

- Description the proposed research design (approach)

So, if you include all these elements, you will have a general outline. Let’s take a closer look at how to write them and what to include in each element so that the research proposal is as robust as the idea itself.

A step-by-step guide to writing a research proposal

#1 introduction.

Researchers who wish to obtain grant funding for a project often write a proposal when seeking funding for a research-based postgraduate degree program, or in order to obtain approval for completing a thesis or PhD. Even though this is only a brief introduction, we should be considering it the beginning of an insightful discussion about the significance of a topic that deserves attention.

Your readers should understand what you are trying to accomplish after they read your introduction. Additionally, they should be able to perceive your zeal for the subject matter and a genuine interest in the possible outcome of the research.

As your introduction, consider answering these questions in three to four paragraphs:

- In what way does the study address its primary issue?

- Does that subject matter fall under the domain of that field of study?

- In order to investigate that problem, what method should be used?

- What is the importance of this study?

- How does it impact academia and society overall?

- What are the potential implications of the proposed research for someone reviewing the proposal?

It is not necessary to include an abstract or summary for the introduction to most academic departments and funding sources. Nevertheless, you should confirm your institution’s requirements.

#2 Background and importance

An explanation of the rationale for a research proposal and its significance is provided in this section. It is preferable to separate this part from the introduction so that the narrative flows seamlessly.

This section should be approached by presuming readers are time-pressed but want a general overview of the whole study and the research question.

Please keep in mind that this isn’t an exhaustive essay that contains every detail of your proposed research, rather a concise document that will spark interest in your proposal.

While you should try to take into account the following factors when framing the significance of your proposed study, there are no rigid rules.

- Provide a detailed explanation of the purpose and problem of the study. Multidimensional or interdisciplinary research problems often require this.

- Outline the purpose of your proposed research and describe the advantages of carrying out the study.

- Outline the major issues or problems to be discussed. These might come in the form of questions or comments.

- Be sure to highlight how your research contributes to existing theories that relate to the problem of the study.

- Describe how your study will be conducted, including the source of data and the method of analysis.

- To provide a sense of direction for your study, define the scope of your proposal.

- Defining key concepts or terms, if necessary, is recommended.

The steps to a perfect research proposal all get more specific as we move forward to enhance the concept of the research. In this case, it will become important to make sure that your supervisor or your funder has a clear understanding of every aspect of your research study.

#3 Reviewing prior literature and studies

The aim of this paragraph is to establish the context and significance of your study, including a review of the current literature pertinent to it.

This part aims to properly situate your proposed study within the bigger scheme of things of what is being investigated, while, at the same time, showing the innovation and originality of your proposed work.

When writing a literature review, it is imperative that your format is effective because it often contains extensive information that allows you to demonstrate your main research claims compared to other scholars.

Separating the literature according to major categories or conceptual frameworks is an excellent way to do this. This is a more effective method than listing each study one by one in chronological order.

In order to arrange the review of existing relevant studies in an efficient manner, a literature review is often written using the following five criteria:

- Be sure to cite your previous studies to ensure the focus remains on the research question. For more information, please refer to our guide on how to write a research paper .

- Study the literature’s methods, results, hypotheses, and conclusions. Recognize the authors’ differing perspectives.

- Compare and contrast the various themes, arguments, methodologies, and perspectives discussed in the literature. Explain the most prominent points of disagreement.

- Evaluate the literature. Identify persuasive arguments offered by scholars. Choose the most reliable, valid, and suitable methodologies.

- Consider how the literature relates to your area of research and your topic. Examine whether your proposal for investigation reflects existing literature, deviates from existing literature, synthesizes or adds to it in some way.

#4 Research questions and objectives

The next step is to develop your research objectives once you have determined your research focus.

When your readers read your proposal, what do you want them to learn? Try to write your objectives in one sentence, if you can. Put time and thought into framing them properly.

By setting an objective for your research, you’ll stay on track and avoid getting sidetracked.

Any study proposal should address the following questions irrespective of the topic or problem:

- What are you hoping to accomplish from the study? When describing the study topic and your research question, be concise and to the point.

- What is the purpose of the research? A compelling argument must also be offered to support your choice of topic.

- What research methods will you use? It is essential to outline a clear, logical strategy for completing your study and make sure that it is doable.

Some authors include this section in the introduction, where it is generally placed at the end of the section.

#5 Research Design and Methods

It is important to write this part correctly and organize logically even though you are not starting the research yet. This must leave readers with a sense of assurance that the topic is worthwhile.

To achieve this, you must convince your reader that your research design and procedures will adequately address the study’s problems. Additionally, it seeks to ensure that the employed methods are capable of interpreting the likely study results efficiently.

You should design your research in a way that is directly related to your objectives.

Exemplifying your study design using examples from your literature review, you are setting up your study design effectively. You should follow other researchers’ good practices.

Pay attention to the methods you will use to collect data, the analyses you will perform, as well as your methods of measuring the validity of your results.

If you describe the methods you will use, make sure you include the following points:

- Develop a plan for conducting your research, as well as how you intend to interpret the findings based on the study’s objectives.

- When describing your objectives with the selected techniques, it is important to also elaborate on your plans.

- This section does not only present a list of events. Once you have chosen the strategy, make sure to explain why it is a good way to analyse your study question. Provide clear explanations.

- Last but not least, plan ahead to overcome any challenges you might encounter during the implementation of your research design.

In the event that you closely follow the best practices outlined in relevant studies as well as justify your selection, you will be prepared to address any questions or concerns you may encounter.

We have an amazing article that will give you everything you need to know about research design .

#6 Knowledge Contribution and Relevance

In this section, you describe your theory about how your study will contribute to, expand, or alter knowledge about the topic of your study.

You should discuss the implications of your research on future studies, applications, concepts, decisions, and procedures. It is common to address the study findings from a conceptual, analytical, or scientific perspective.

If you are framing your proposal of research, these guide questions may help you:

- How could the results be interpreted in the context of contesting the premises of the study?

- Could the expected study results lead to proposals for further research?

- Is your proposed research going to benefit people in any way?

- Is the outcome going to affect individuals in their work setting?

- In what ways will the suggested study impact or enhance the quality of life?

- Are the study’s results going to have an impact on intervention forms, techniques, or policies?

- What potential commercial, societal, or other benefits could be derived from the outcomes?

- Policy decisions will be influenced by the outcomes?

- Upon implementation, could they bring about new insights or breakthroughs?

Throughout this section, you will identify unsolved questions or research gaps in the existing literature. If the study is conducted as proposed, it is important to indicate how the research will be instrumental in understanding the nature of the research problem.

#7 Adherence to the Ethical Principles

In terms of scientific writing style, no particular style is generally acknowledged as more or less effective. The purpose is simply to provide relevant content that is formatted in a standardized way to enhance communication.

There are a variety of publication styles among different scholarly disciplines. It is therefore essential to follow the protocol according to the institution or organization that you are targeting.

All scholarly research and writing is, however, guided by codes of ethical conduct. The purpose of ethical guidelines, if they are followed, is to accomplish three things:

1) Preserve intellectual property right;

2) Ensure the rights and welfare of research participants;

3) Maintain the accuracy of scientific knowledge.

Scholars and writers who follow these ideals adhere to long-standing standards within their professional groups.

An additional ethical principle of the APA stresses the importance of maintaining scientific validity. An observation is at the heart of the standard scientific method, and it is verifiable and repeatable by others.

It is expected that scholars will not falsify or fabricate data in research writing. Researchers must also refrain from altering their studies’ outcomes to support a particular theory or to exclude inconclusive data from their report in an effort to create a convincing one.

#8 The budget

The need for detailed budgetary planning is not required by all universities when studying historical material or academic literature, though some do require it. In the case of a research grant application, you will likely have to include a comprehensive budget that breaks down the costs of each major component.

Ensure that the funding program or organization will cover the required costs, and include only the necessary items. For each of the items, you should include the following.

- To complete the study in its entirety, how much money would you require?

- Discuss the rationale for such a budget item for the purpose of completing research.

- The source of the amount – describe how it was determined.

When doing a study, you cannot buy ingredients the way you normally would. With so many items not having a price tag, how can you make a budget? Take the following into consideration:

- Does your project require access to any software programs or solutions? Do you need to install or train a technology tool?

- How much time will you be spending on your research study? Are you required to take time off from work to do your research?

- Are you going to need to travel to certain locations to meet with respondents or to collect data? At what cost?

- Will you be seeking research assistants for the study you propose? In what capacity and for what compensation? What other aspects are you planning to outsource?

It is possible to calculate a budget while also being able to estimate how much more money you will need in the event of an emergency.

#9 Timeline

A realistic and concise research schedule is also important to keep in mind. You should be able to finish your plan of study within the allotted time period, such as your degree program or the academic calendar.

You should include a timeline that includes a series of objectives you must complete to meet all the requirements for your scholarly research. The process starts with preliminary research and ends with final editing. A completion date for every step is required.

In addition, one should state the development that has been made. It is also recommended to include other relevant research events, for instance paper or poster presentations . In addition, a researcher must update the timeline regularly, as necessary, since this is not a static document.

#10 A Concluding Statement

Presenting a few of the anticipated results of your research proposal is an effective way to conclude your proposal.

The final stage of the process requires you to reveal the conclusion and rationale you anticipate reaching. Considering the research you have done so far, your reader knows that these are anticipated results, which are likely to evolve once the whole study is completed.

In any case, you must let the supervisors or sponsors know what implications may be drawn. It will be easier for them to assess the reliability and relevance of your research.

It will also demonstrate your meticulousness since you will have anticipated and taken into consideration the potential consequences of your research.

The Appendix section is required by some funding sources and academic institutions. This is extra information that is not in the main argument of the proposal, but appears to enhance the points made.

For example, data in the form of tables, consent forms, clinical/research guidelines, and procedures for data collection may be included in this document.

Research Proposal Template

Now that you know all about each element that composes an ideal research proposal, here is an extra help: a ready to use research proposal example. Just hit the button below, make a copy of the document and start working!

Avoid these common mistakes

In an era when rejection rates for prestigious journals can reach as high as 90 percent, you must avoid the following common mistakes when submitting a proposal:

- Proposals that are too long. Stay to the point when you write research proposals. Make your document concise and specific. Be sure not to diverge into off-topic discussions.

- Taking up too much research time. Many students struggle to delineate the context of their studies, regardless of the topic, time, or location. In order to explain the methodology of the study clearly to the reader, the proposal must clearly state what the study will focus on.

- Leaving out significant works from a literature review. Though everything in the proposal should be kept at a minimum, key research studies must need to be included. To understand the scope and growth of the issue, proposals should be based on significant studies.

- Major topics are too rarely discussed, and too much attention is paid to minor details. To persuasively argue for a study, a proposal should focus on just a few key research questions. Minor details should be noted, but should not overshadow the thesis.

- The proposal does not have a compelling and well-supported argument. To prove that a study should be approved or funded, the research proposal must outline its purpose.

- A typographical error, bad grammar or sloppy writing style. Even though a research proposal outlines a part of a larger project, it must conform to academic writing standards and guidelines.

A final note

We have come to the end of our research proposal guide. We really hope that you have found all the information you need. Wishing you success with the research study.

We at Mind the Graph create high quality illustrative graphics for research papers and posters to beautify your work. Check us out here .

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Unlock Your Creativity

Create infographics, presentations and other scientifically-accurate designs without hassle — absolutely free for 7 days!

About Fabricio Pamplona

Fabricio Pamplona is the founder of Mind the Graph - a tool used by over 400K users in 60 countries. He has a Ph.D. and solid scientific background in Psychopharmacology and experience as a Guest Researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry (Germany) and Researcher in D'Or Institute for Research and Education (IDOR, Brazil). Fabricio holds over 2500 citations in Google Scholar. He has 10 years of experience in small innovative businesses, with relevant experience in product design and innovation management. Connect with him on LinkedIn - Fabricio Pamplona .

Content tags

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide [With Template]

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide [With Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write A Proposal

Writing a Proposal involves several key steps to effectively communicate your ideas and intentions to a target audience. Here’s a detailed breakdown of each step:

Identify the Purpose and Audience

- Clearly define the purpose of your proposal: What problem are you addressing, what solution are you proposing, or what goal are you aiming to achieve?

- Identify your target audience: Who will be reading your proposal? Consider their background, interests, and any specific requirements they may have.

Conduct Research

- Gather relevant information: Conduct thorough research to support your proposal. This may involve studying existing literature, analyzing data, or conducting surveys/interviews to gather necessary facts and evidence.

- Understand the context: Familiarize yourself with the current situation or problem you’re addressing. Identify any relevant trends, challenges, or opportunities that may impact your proposal.

Develop an Outline

- Create a clear and logical structure: Divide your proposal into sections or headings that will guide your readers through the content.

- Introduction: Provide a concise overview of the problem, its significance, and the proposed solution.

- Background/Context: Offer relevant background information and context to help the readers understand the situation.

- Objectives/Goals: Clearly state the objectives or goals of your proposal.

- Methodology/Approach: Describe the approach or methodology you will use to address the problem.