Periodical Essay Definition and Examples

Print Collector/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

A periodical essay is an essay (that is, a short work of nonfiction) published in a magazine or journal--in particular, an essay that appears as part of a series.

The 18th century is considered the great age of the periodical essay in English. Notable periodical essayists of the 18th century include Joseph Addison, Richard Steele , Samuel Johnson , and Oliver Goldsmith .

Observations on the Periodical Essay

"The periodical essay in Samuel Johnson's view presented general knowledge appropriate for circulation in common talk. This accomplishment had only rarely been achieved in an earlier time and now was to contribute to political harmony by introducing 'subjects to which faction had produced no diversity of sentiment such as literature, morality and family life.'" (Marvin B. Becker, The Emergence of Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century . Indiana University Press, 1994)

The Expanded Reading Public and the Rise of the Periodical Essay

"The largely middle-class readership did not require a university education to get through the contents of periodicals and pamphlets written in a middle style and offering instruction to people with rising social expectations. Early eighteenth-century publishers and editors recognized the existence of such an audience and found the means for satisfying its taste. . . . [A] host of periodical writers, Addison and Sir Richard Steele outstanding among them, shaped their styles and contents to satisfy these readers' tastes and interests. Magazines--those medleys of borrowed and original material and open-invitations to reader participation in publication--struck what modern critics would term a distinctly middlebrow note in literature. "The most pronounced features of the magazine were its brevity of individual items and the variety of its contents. Consequently, the essay played a significant role in such periodicals, presenting commentary on politics, religion, and social matters among its many topics ." (Robert Donald Spector, Samuel Johnson and the Essay . Greenwood, 1997)

Characteristics of the 18th-Century Periodical Essay

"The formal properties of the periodical essay were largely defined through the practice of Joseph Addison and Steele in their two most widely read series, the "Tatler" (1709-1711) and the "Spectator" (1711-1712; 1714). Many characteristics of these two papers--the fictitious nominal proprietor, the group of fictitious contributors who offer advice and observations from their special viewpoints, the miscellaneous and constantly changing fields of discourse , the use of exemplary character sketches , letters to the editor from fictitious correspondents, and various other typical features--existed before Addison and Steele set to work, but these two wrote with such effectiveness and cultivated such attention in their readers that the writing in the Tatler and Spectator served as the models for periodical writing in the next seven or eight decades." (James R. Kuist, "Periodical Essay." The Encyclopedia of the Essay , edited by Tracy Chevalier. Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997)

The Evolution of the Periodical Essay in the 19th Century

"By 1800 the single-essay periodical had virtually disappeared, replaced by the serial essay published in magazines and journals. Yet in many respects, the work of the early-19th-century ' familiar essayists ' reinvigorated the Addisonian essay tradition, though emphasizing eclecticism, flexibility, and experientiality. Charles Lamb , in his serial Essays of Elia (published in the London Magazine during the 1820s), intensified the self-expressiveness of the experientialist essayistic voice . Thomas De Quincey 's periodical essays blended autobiography and literary criticism , and William Hazlitt sought in his periodical essays to combine 'the literary and the conversational.'" (Kathryn Shevelow, "Essay." Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837 , ed. by Gerald Newman and Leslie Ellen Brown. Taylor & Francis, 1997)

Columnists and Contemporary Periodical Essays

"Writers of the popular periodical essay have in common both brevity and regularity; their essays are generally intended to fill a specific space in their publications, be it so many column inches on a feature or op-ed page or a page or two in a predictable location in a magazine. Unlike freelance essayists who can shape the article to serve the subject matter, the columnist more often shapes the subject matter to fit the restrictions of the column. In some ways this is inhibiting because it forces the writer to limit and omit material; in other ways, it is liberating, because it frees the writer from the need to worry about finding a form and lets him or her concentrate on the development of ideas." (Robert L. Root, Jr., Working at Writing: Columnists and Critics Composing . SIU Press, 1991)

- The Essay: History and Definition

- exploratory essay

- What Is Enlightenment Rhetoric?

- What Are the Different Types and Characteristics of Essays?

- The Difference Between an Article and an Essay

- An Introduction to Literary Nonfiction

- Biography of Samuel Johnson, 18th Century Writer and Lexicographer

- What Is a Personal Essay (Personal Statement)?

- Definition of Belles-Lettres in English Grammer

- Definition and Examples of Formal Essays

- Samuel Johnson's Dictionary

- What is a Familiar Essay in Composition?

- 4 Publications of the Harlem Renaissance

- Samuel Johnson Quotes

- Life and Work of H.L. Mencken: Writer, Editor, and Critic

- Top Books About The Age of Enlightenment

What Is a Periodical Essay?

Publication Date: 06 Mar 2019

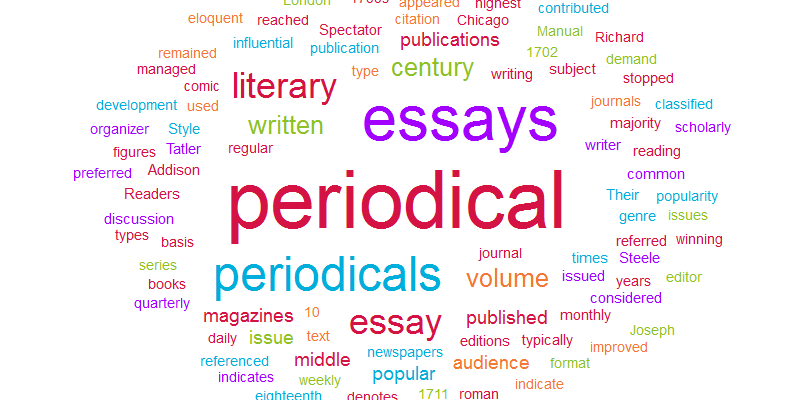

A periodical essay is a type of writing that is issued on a regular basis as a part of a series in editions such as journals, magazines, newspapers or comic books. It is typically published daily, weekly, monthly or quarterly and is referenced by volume and issue.

Volume indicates the number of years when the publication took place while issue denotes how many times the periodical was issued during the year. For example, the May 1711 publication of a monthly journal that was first published in 1702 would be referred to as, “volume 10, issue 5”. At times, roman numerals were also used to indicate the volume number. For the citation of text in a periodical, such a format as The Chicago Manual of Style is used.

The periodical essay appeared in the early 1700s and reached its highest popularity in the middle of the eighteenth century. London magazines such as The Tatler and The Spectator were the most popular and influential periodicals of that time. It is considered that The Tatler introduced such literary genre as periodical essay while The Spectator improved it. The magazines remained influential even after they stopped publications. Their issues were later published in the form of a book, which was in demand for the rest of the century.

Richard Steele and Joseph Addison are considered to be the figures who contributed the most to the development of the eighteen-century literary genre of periodical essays. They managed to create a winning team where Addison was more of an eloquent writer while Steele made his contribution by being an outstanding organizer and editor.

Typically, the essays can be classified into such two types as popular and scholarly. Also, this literary form was written for an audience of professionals who preferred to read business, technical, academic, scientific and trade publications.

However, for the most part, the periodicals were about morality, emotions and manners. Readers expected essays to be common sense and thought-provoking. Publications were relatively short and mainly characterized as those which provide an opinion inspired by contemporary events. Periodicals were meant to be not “heavy”, especially those which were referred to as popular reading. The majority of topics in the periodicals were supposed to be appropriate for the common talk and general discussion.

Many essays were written for female readers as a target audience. Periodicals were aimed at middle-class people who were literate enough and could afford to buy the editions regularly. The essays were written in a so-called middle style and high education was not required for reading the majority of the contents. Over time, many periodical writers shaped their styles in order to satisfy the literary taste of the audience.

All periodical essays tend to be brief but texts written by a columnist and freelance essayist would slightly differ in length. The former writes his material trying to shape the subject of discussion to fit the requirements of the column. The latter though can take advantage of a more liberating approach by crafting his work the way he wants as long as his text manages to effectively highlight the subject.

Periodicals evolved in the 19 th century and single essays were almost fully replaced by serial essay publishing. The writings became more eclectic, flexible and brave being at the same time literary and conversational.

Do you need the help of a professional essay writer ? Contact us today and get quality assistance with writing any type of paper. Getting good grades has never been so easy!

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Addison and Steele Q-THE PERIODICAL ESSAY

Related Papers

Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research)

Girija Suri

John Richetti

First a talk at various places, then a published essay in about 2000 in Eighteenth-Century Fiction.

Brno Studies in English

Katarzyna Kozak

The period between the Glorious Revolution and the end of Queen Anne's reign was a time when political parties struggled with one another in order to create their own distinctive identity. The rivalry between Whigs and Tories defined the political situation in early eighteenth-century Britain and laid the foundation for the development of the ministerial machine of propaganda aimed at discrediting opponents and justifying the policies of the government. The rhetoric adopted by the contemporary political writers included the reason-passion bias so inextricably associated with the philosophical background of the 'Age of Reason'. From this perspective, this article sets out to trace the evolution in Steele's journalistic productions (The Spectator, The Englishman, The Reader) and to delineate key changes in his strategies for achieving political goals and, at the same time, discredit his rival paper-The Examiner.

Cambridge History of Literary Criticism

James Basker

The rise of periodical literature changed the face of criticism between 1660 and 1800. To chart a course through this jungle of literary growth and its implications for the history of criticism, it is useful to look at three basic periods within which slightly different genres of periodical predominated and left their mark on literary culture. The first, from the mid- 1600s to 1700, saw the infancy of the newspaper and, from about 1665, the establishment of the learned journal; during the second, from 1700 to 1750, the periodical essay enjoyed its greatest influence, and the magazine or monthly miscellany, with all its popular appeal, came to prominence; in the third, from about 1750 to 1800, the literary review journal emerged in a recognizably modern form and rapidly came to dominate the practice of criticism.

LITERATURE OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

This was an invited paper given at the 'Inventions of the Text' seminar at Durham University in May 2018. The paper considers the relationship between empiricism and the familiar essay in the eighteenth century. It notes the emergence of scepticism, dialogue, and the idea of performative rationality as hallmarks of what might be termed a tradition of ‘socialised’, decentred empiricism that flourished in the mid-to-late eighteenth century in Britain. The essay was vital to this emergence because of the ways in which the genre drew together experience and communication, the philosophical and the social. By subordinating methodical 'dispositio' to dialogical 'complicatio', the essay offered an alternative model of order and rational thought to that implied by system. This model relied not upon a priori principle or even sensory data, but upon a blurry consensus underpinned by a mixture of doubt, dialogue and the performance of civic virtues. And yet, even as it celebrates an idea of truth that was underpinned by these activities and qualities, the familiar essay ultimately testifies to the passing of this idea.

Studies in British Literature: The …

Studies in British Literature: The Eighteenth Century. DSpace/Manakin Repository. ...

Ingo Berensmeyer

This article explores the development of English poetry in the eighteenth century in relation to the emergence of prose fiction, arguing for a less novel-centred perspective in eighteenth-century literary history and for a a more inclusive, media-oriented approach to the study of literary genres in general. It demonstrates how Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift respond to the challenges of a new media culture by a thematic shift towards 'urban realism' in the mock epic and mock georgic. On that basis, it then analyses Thomas Gray's Elegy Wrote in a Country Church Yard as a complex reflection on the role of poetry in competition with the novel in eighteenth-century print culture.

konchok kyab

RELATED PAPERS

Mariana Gutierrez

Astronomy & Astrophysics

Axel Jessner

Shirlei Recco-pimentel

Molecular biology and …

David Harry

Konstantina Chatzara

TIMOTHY JAMES STA. ANA GUIRIBA

AVES: Jurnal Ilmu Peternakan

Ahmad Khoirul

Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology

Tạp chí Y học Việt Nam

Nguyễn Tấn Bình

Antonio Daniele

Environments

Anabela Martins

Revista do Direito do Trabalho e Meio Ambiente do Trabalho

Alessandro Severino Vallér Zenni

Journal of Science and Technology - IUH

Aquaculture Economics & Management

Ambekar Eknath

Endocrine Connections

Marta Burei

Publicationes Mathematicae Debrecen

Matjaž Omladič

International Journal of Epidemiology

Susan Levenstein

Tijdschrift voor psychiatrie

Philippe Delespaul

BMC chemistry

Hanan Georgey

Miraides Brown

Value in Health

Javier Rejas

HAL (Le Centre pour la Communication Scientifique Directe)

ALAIN PANERO

Revista Cultivando o Saber

Irene Carniatto

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Buy Custom Assignment

- Custom College Papers

- Buy Dissertation

- Buy Research Papers

- Buy Custom Term Papers

- Cheap Custom Term Papers

- Custom Courseworks

- Custom Thesis Papers

- Custom Expository Essays

- Custom Plagiarism Check

- Cheap Custom Essay

- Custom Argumentative Essays

- Custom Case Study

- Custom Annotated Bibliography

- Custom Book Report

- How It Works

- +1 (888) 398 0091

- Essay Samples

- Essay Topics

- Research Topics

- Uncategorized

- Writing Tips

How To Write a Periodical Essay

December 26, 2016

Periodical essay papers are a journey or journal through one's eye or characters develop based on series of events accordingly.

Essay papers based on periodical is affected by century, culture, language and belief of the community, showing the mirror of their age, the reflection of their thinking. How literature acts as a medium in daily’s usage of a population in certain areas affect most on how this periodical journal is produced, how characters are developed, what makes the journal stands out from the others and so on.

How To Write?

Joseph Addison and Steele have applied periodical essay in their papers which are Tatler in 1709-1711 and Spectator in 1711-1712 and again in 1714. This means that custom periodical essay papers have been recognized and used the long time ago to produce series of events through custom essay papers. It is said that custom periodical essay papers existed even before Joseph Addison and Steele start their work, through sketches and letters from various features.

The most successful periodical essays can be a long list. Most influential custom periodical essay papers include Henry Fielding’s Covent Garden Journal in 1752, Samuel Johnson’s Rambler in 1750- 1752, Henry Mackenzie’s Mirror in 1779-1780, Oliver Goldsmith in 1757 to 1772 to name a few.

Cultures and analysis of the ways relate to the associations are reflected through actors characterization and goals for the particular projects. The role of maintaining language practices in the community allows these essayists to work on their periodical essay papers customization. College essay papers also related to social networks in a culture by the time these papers are produced.

That is basically how these popular periodical essays gain attention from worldwide at their century.

Editorial Policies

The impact on periodical essay papers was immediate through the eighteenth century. It is definitely beyond Addison and Steller's expectations as well as publications. These guys re-modeled their content and editorial policies of their periodical essay, Tatler, and Spectator, as well as Guardian into different languages outside England, gained immediate attention from a community outside England.

Oliver Goldsmith from 1757 to 1772 also contributed to numbers of custom periodical essay including The Monthly Review with ran to eight weekly numbers. His best work, The Citizen of the World in 1762 proves that he is attractive, lack of formality and sensitive as the main attraction to his periodical essay.

Periodically essay is still emerging despite the deep roots and far-reaching networks by the eighteenth century. These essay papers belong to definite period due to its tight connection in publishing practices, politics, and law.

Howeve,r the numbers of publication rise and fall considerably even at times of national crisis.

Customs writing service can do all of your college assignments! Stop dreaming about legal write my essay for me service! We are here!

Sociology Research Topics Ideas

Importance of Computer in Nursing Practice Essay

History Research Paper Topics For Students

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy. We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related emails.

Latest Articles

Navigating the complexities of a Document-Based Question (DBQ) essay can be daunting, especially given its unique blend of historical analysis...

An introduction speech stands as your first opportunity to connect with an audience, setting the tone for the message you...

Embarking on the journey to write a rough draft for an essay is not just a task but a pivotal...

I want to feel as happy, as your customers do, so I'd better order now

We use cookies on our website to give you the most relevant experience by remembering your preferences and repeat visits. By clicking “Accept All”, you consent to the use of ALL the cookies. However, you may visit "Cookie Settings" to provide a controlled consent.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Richard Squibbs is Associate Professor of English at DePaul University in Chicago and author of Urban Enlightenment and the Eighteenth-Century Periodical Essay (Palgrave, 2014). While he continues to publish articles on the British and early American periodical essay, he is also completing a monograph that explores the messy entanglements of picaresque fiction and the early English novel.

- Published: 20 October 2022

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter examines Johnson’s achievements as an essayist in relation to the established conventions of the periodical essay. With the Rambler , Johnson restored the periodical essay to its once-prominent place in English literary culture by elevating its moral seriousness and emphasizing its aptness as a vehicle for literary criticism. The success of the series spurred a revival of the genre at mid-century, albeit largely in reaction to the Rambler ’s relative gravity and ponderous diction. After doubling down on the Rambler ’s style with his contributions to the Adventurer , Johnson experimented with a more playful approach to the periodical essay in the Idler . The mixed critical reception of his efforts near the end of the century often associated his essays more with the moralist and critic Johnson had become than with the genre in which he first enjoyed popular success, an enduring perspective that this chapter aims to qualify.

What must Johnson have made of Oliver Goldsmith’s “resverie” in his short-lived periodical the Bee (1759), wherein the gruff coachman of “ The fame machine ” refuses Johnson a seat for his Dictionary but relents immediately upon realizing that this “very grave personage” is the author of the Rambler ? 1 To a writer who had striven for fame since arriving in London over twenty years before, such praise from a stranger was no doubt gratifying (Johnson and Goldsmith wouldn’t first meet for another eighteen months). And it might have boosted his morale as he toiled away at the Idler in the wake of terrible personal and financial setbacks, while still procrastinating on his long-delayed edition of Shakespeare. But while collected editions of the Rambler had sold moderately well by the time Goldsmith hailed it, Johnson may have been bemused nonetheless to see his literary immortality staked on his periodical essays rather than his monumental contribution to fixing the English language.

On the other hand, the relatively minor genre of the periodical essay seems to have appealed to Johnson because no one since its great originators, Addison and Steele, had managed to find enduring success in it. In the thirty-five years between the end of the Spectator and the first number of the Rambler , roughly three dozen essay series modeled on the Tatler , Spectator , and Guardian had appeared in London. Of these, only three titles were issued in collected editions more than three times; and even then, only the most recent, the Female Spectator (1744–6), would see an edition in print beyond the 1740s. 2 Meanwhile, new collected editions of Addison’s and Steele’s series continued to appear regularly every few years, with the latest brought out in 1749–50. Johnson’s aim was therefore to succeed in writing essays that would not just momentarily captivate the public but stand “the test of a long trial” like those of his great predecessors (Boswell, Life , vol. i, 201). And in this he half-succeeded. For while the Rambler ’s original periodical readership was small, the collected essays enjoyed a thriving afterlife as “classicks” for roughly seventy years, until English literary taste had changed sufficiently to make the rigor and religiosity of Johnson’s moralizing seem outmoded and dull. Goldsmith, then, was half-right too. Posterity indeed still remembers the Rambler , but only as the lesser writing of Dictionary Johnson.

From the vantage of 1759, however, Johnson’s single-handed restoration of the periodical essay to literary prominence was remarkable not just for the Rambler itself, but for stimulating a brief but prolific revival of the genre after more than three decades of mediocre iterations. The Rambler ’s ruminative style, generalizing philosophy, and sober self-criticism stripped the approach of Addison’s and Steele’s essays to what Johnson conceived as the genre’s bare rhetorical essence. Instead of recording the foibles of the Town in their time-bound details, he sought to abstract from them general principles of right and wrong conduct. When three major collections of periodical essays—James Harrison’s British Classicks (1786), J. Parsons’s Select British Classics (1793), and Alexander Chalmers’s British Essayists (1803)—canonized the genre at the end of the eighteenth century, all skipped straight from the Guardian to the Rambler and those series which immediately followed it. Nathan Drake, too, structured his five-volume history of the genre (1805, 1809) around these same high-water marks. But where Johnson looked to the Spectator as an inspiring example of how diurnal essays could live on into posterity, most essayists writing in the wake of the Rambler pointedly rejected Johnson’s religious seriousness and heavy-handed style. So even in the one literary genre in which Johnson was demonstrably influential, his example was mostly a negative one—fitting for such a dogged contrarian.

The Periodical Essay

The Rambler today is best known for its moral and intellectual rigor and elevated diction: a totemic expression of the older Johnson made familiar by Boswell. Among students of the eighteenth century who are not Johnsonians, roughly five essays have come to stand in for the series as a whole: Rambler 4 (on the novel), 5 (on Spring), 12 (on a young woman come to London for service), 60 (on biography), and 155 (on the danger of habits). In this, the Rambler has shared the fate of the Spectator , whose 635 essays are typically represented by the eight or so that are most often anthologized. But in the Spectator ’s case, we read them because of the ratified historical impact they had in constituting the modern public sphere and its characteristic print media. In the case of the Rambler , we read them because Boswell’s Johnson wrote them. Their difference from other periodical essays, in other words, is what marks them as Johnson’s and makes them worth reading. Taken as a whole, however, the Rambler offers insight not just into the literary development of Johnson’s characteristic philosophical tough-mindedness, but into a generic conception of the periodical essay that has been mostly lost to literary history.

As Boswell notes, Johnson undertook the Rambler to remedy a conspicuous absence in the publishing world of mid-century London: no essay series of comparable scope, moral intent, or literary and intellectual quality had appeared since the Spectator ’s last volume of 1714. So much time had elapsed, and so many inferior imitations had come and gone, in fact, that he believed such a publication would “have the advantage of novelty” ( Life , vol. i, 201). The Rambler ’s wordy, at times ponderous, style was certainly novel for the genre and much remarked upon (Boswell’s defense of it, comparing the acquired taste of Johnson’s harder “liquor of more body” to Addison’s instantly pleasing “light wine,” is among his most apt similes—even if he seems to have taken it from Johnson himself: Life , vol. i, 224). 3 And against the expectations of the title, Rambler essays tend to reek of the closed air of the study rather than sparkle with the liveliness of the town as had the Tatler and Spectator . This was deliberate, as Johnson found Steele’s essays wanting for “being mere Observations on Life and Manners without a sufficiency of solid Learning acquired from Books” (Boswell, Life , vol. i, 215). Instead of recording and reflecting on the minutiae of London life with such compelling style that his essays might eventually claim the notice of posterity, Johnson used the winnowing force of his intellect and rhetoric immediately to retrieve kernels of universal truth from the disposable husks of everyday situations. This made the Rambler responsive more to Johnson’s sense of what should always matter than to the comparatively petty matters of the day.

Johnson’s account of the Spectator ’s achievement in the Life of Addison offers crucial insight into this revisionist conception of the periodical essay. John Gay’s “Present State of Wit” (1711), the first extensive account of the new genre, provided the template, which Johnson would fill out with a deeper sense of literary history. Gay had marveled at how the Tatler dared “to tell the Town”—twice weekly—“that they were a parcel of Fops, Fools, and vain Cocquets” yet managed to reform readers’ behavior because it did so with such panache. 4 “’Tis incredible to conceive the effect his Writings have had on the Town,” Gay goes on; “How many Thousand follies they have either quite banish’d, or given a very great check to” while having “set all our Wit and Men of Letters upon a new way of Thinking” ( Poetry and Prose , vol. ii, 452). Though Town manners had started to backslide once the Tatler ceased publishing, Gay held out great hope for the newly published Spectator , whose “Spirit and Stile” and “Prodigious … Run of Wit and Learning” promises similarly great things (455). Johnson, too, praises the Tatler and Spectator for supplying “cooler and more inoffensive reflections” to “minds heated with political contest” by the newssheets of the day, noting that these essays “had a perceptible influence upon the conversation of that time, and taught the frolick and the gay to unite merriment with decency” (Yale Works , vol. xxii, 614). One can hear echoes of this account in Habermas’s still-influential theory of how the first English periodicals helped create modern public culture in Queen Anne’s London. Yet Johnson also situates this new form of print media in a longer history of European literature in ways that implicitly explain his manner of proceeding in the Rambler .

The Rambler was, in some ways, a throwback. But to what exactly? Boswell sought to explain and ennoble the Rambler ’s characteristic ponderousness by giving it a distinguished national pedigree. The rigor of Johnson’s style, he claimed, harks back to “the great writers of the last century, Hooker, Bacon, Sanderson, Hakewell, and others,” like Sir William Temple and Sir Thomas Browne ( Life , vol. i, 219, 221). By the time Boswell wrote this, the Rambler had become a “classic” of the English essay tradition, known to many more readers as handsomely bound volumes than it ever had been in periodical form; it had taken its rightful place, shelved alongside the tomes of early modern England’s hardest and most serious thinkers. The Rambler ’s original periodicity appears, from this vantage, incidental to its universal character and worth. Johnson’s own account of the periodical essay, however, emphasizes the genre’s complex, and necessary, engagement with its own moment. He also gives it a deep transnational pedigree, citing “Casa in his book of Manners , and Castiglione in his Courtier ” as key precedents for the Tatler ’s and Spectator ’s common mission to reform “the unsettled practice of daily intercourse by propriety and politeness” (Yale Works , vol. xxii, 614). But Johnson notes, too, that these English serials bear the influence of the popular Caractères (1688) of Jean de La Bruyère. This collection of satiric portraits of courtiers and citizens during the reign of Louis XIV “exhibited the “Characters and Manners of the Age” so engagingly and with such “justness of observation” that new French and English editions continued to be issued and read, long after the society, whose foibles La Bruyère skewered, had ceased to be (vol. xxii, 614, 612). By so successfully bridging the gap between timely moral writing and the regard of posterity, the Caractères in Johnson’s view provides a model to which authors of popular moral essays should aspire. The distinctively English innovation was to use the nation’s notorious public appetite for news and controversy, and the teeming print media which fed it, as a means of mass social and cultural improvement. 5

The Form of the Rambler

This potted history might suggest that Johnson wasn’t much concerned with the periodical essay’s formal dimensions, but the format he chose for the Rambler indicates otherwise. The Caractères in The Life of Addison appears not only as a conceptual bridge between present and future, but also formally as one between the Italian conduct books and the Spectator . While Castiglione’s Cortegiano (Book of the Courtier) (1528) is a collection of dialogues and Casa’s Galateo (A Treatise on Politeness) (1558) a monologic discourse, the Caractères is a miscellaneous collection of essays, moral reflections, and character sketches that manage to compel despite being “written without connection” (Yale Works , vol. xxii, 612). La Bruyère’s book, in a way, represents what would become the end of the publishing trajectory of the English periodical essay, as formerly weekly (or biweekly, or even daily) sheets responding to matters of the moment were collected in volumes and reprinted as morally, if not thematically, consistent wholes. The numerous sections of the Caractères , however, never circulated individually. In Johnson’s view, this may have hindered the work’s effectiveness, for writing that attempts to reform its readers’ morals and manners must be adapted formally to its intended sphere of action. Johnson notes that while English readers have long “had many books to teach us our more important duties,” before the Tatler and Spectator no literary works had appositely engaged the comparatively minor “track of daily conversation” that required for its reformation “the frequent publication of short papers, which we read not as study, but amusement” (vol. xxii, 613). The dignity of the form (minor though it may be) lies in its self-sufficiency: regularly circulated folio half-sheets act as a material bulwark of common sense against the flood of newssheets and controversial tracts “agitating the nation” (vol. xxii, 614). This was the original format of the periodical essay, to which Johnson deliberately returned with the Rambler .

Between the final number of the Spectator and the first of the Rambler , essay serials had appeared much more frequently as columns amidst the miscellaneous matter in magazines and newspapers than as individually published sheets. Many of these, like Lewis Theobald’s Censor , first published in Mist’s Journal (1715–17), were later brought out in collected editions to assert their enduring value apart from their original, evidently ephemeral, publication media. Such was the assumed cachet of the single-sheet essay that the preface to the Humourist (1720) claimed that its initial popularity when the essays had “appear’d Abroad singly” warranted this collected volume, though there’s no indication that the Humourist had ever circulated as individual sheets (1720, [xxxi]). 6 The folio half-sheet, according to Spectator 10, helped focus the mind amidst the myriad distractions of London and its teeming “publick Prints.” 7 The double-column printing of the Spectator ’s sheets, moreover, slyly mimicked the form of the standard early eighteenth-century newssheet in order to confound readers’ expectations when, instead of finding the usual miscellaneous material therein, they’d discover a single, sustained topic for reflection. By taking just the “Quarter of an Hour” required to read one of these essays each morning, London’s citizens could then apply the “sound and wholesome Sentiments” they contained to their daily experiences around town ( Spectator , vol. i, 47, 46). Johnson, as a former editor and miscellaneous writer for the Gentleman’s Magazine , recognized how essential this self-contained format was to the focusing aims of the periodical essay and refined it further to emphasize the genre’s inherent dignity. Each Rambler essay was printed in single columns across three half-sheets to make it stand out even more from other periodicals. The series was also the first printed without advertisements, and with sequential page numbering to encourage readers to keep and bind them in order. These changes materially reflect Johnson’s posterity-oriented conception of the periodical essay and would shortly be adopted by series like the Adventurer (1752–4), the World (1753–6), the Connoisseur (1754–6), the Mirror (1779–80), and the Lounger (1785–7). To write essays for the present was, for Johnson and his immediate successors, also to write for the edification of readers in an extensive, unknowable future.

The Topicality of the Rambler

While these formal departures indicate Johnson’s desire to elevate the Rambler above everyday pettiness and commercial concerns, the essays themselves were not unconcerned with matters of the moment. James Woodruff has shown how Johnson’s original readers would have easily grasped the topical relevance of a number of Rambler essays whose contemporary context is not immediately evident to us. Using London newspapers as his guide, Woodruff connects several essays on the problematic effects of sudden riches, and one on the force of chance in human affairs, to the public mania generated by the State Lottery drawing of 1751. 8 Rambler 107 (March 26, 1751) refers directly to the imminent shift in Britain from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar; the taxonomy in Rambler 144 of various types of pernicious detractors appeared amidst several cases of public reputation-trashing; the warning in Rambler 149 against prematurely condemning suspects of criminal acts followed on the heels of a widely reported instance of mob justice; and no. 148, dealing with “parental tyranny,” was published in the wake of news reports concerning multiple acts of parricide and filicide. 9 Besides these, the Rambler features recurring seasonal reflections; meditations during religious holidays; and critical essays on biography, history, prose fiction, and poetry which seem prompted by recent publications. Though Johnson would boast in the Rambler ’s final number that he had “never complied with temporary curiosity, nor enabled [his] readers to discuss the topick of the day” (Yale Works , vol. v, 316), this was true only in the most reductive sense. Research like Woodruff’s demonstrates how Johnson regularly aligned the Rambler ’s philosophical inquiries with topics of great public interest to demonstrate, by implication, how readers might come to recognize general or universal patterns of conduct (or moral truth) in what might otherwise appear passing matters of media-driven concern.

This Johnsonian impulse to reveal the enduring substance beneath superficial appearances informs the Rambler ’s signature rhetorical style as well. The contrast with the Spectator illuminates how each series models, in its essayistic form, different conceptions of how readers should engage with the world. A typical Spectator essay will declare its proposition concerning human character and conduct, and then move through a number of particular instances that demonstrate the validity of that proposition. “The most improper things we commit in the Conduct of our Lives, we are led into by the Force of Fashion,” begins Spectator 64. “Instances may be given, in which a prevailing Custom makes us act against the Rules of Nature, Law, and common Sense,” Mr. Spectator continues, “but at present I shall confine my Consideration of the Effect it has upon Men’s Minds, by looking into our Behaviour when it is the Fashion to go into Mourning.” Following an account of the history of courtly mourning rituals, the essay concludes by pointing out how absurd it is for the general public to adopt such rituals to mourn foreign princes with whom they have no connection, not least because the mass shift to mourning garb leaves domestic clothiers “pinched with present Want” for the period’s duration. The essay’s arch tone and wry depiction of the “wholesale Dealer in Silks and Ribbons,” who dreads the death of any “foreign Potentate” because of how this fashionable “Folly” will impact his bottom line, reinforce the worldliness of its moralizing ( Spectator , vol. i, 275–7). This pattern—followed throughout the Spectator —formally enacts the ideal process by which readers should mull over the general moral or philosophical points the essays raise as they encounter representative instances of them in their daily business around the Town and City.

The Rambler likewise matches its rhetoric to its aims, but with a key difference. Whereas the Spectator adduces worldly particulars to bear out its nuggets of general wisdom, Rambler essays often take circuitous tours from moral generalities through particular exceptions to these general rules, before returning to modified reaffirmations of these essays’ original propositions. “The heart of Johnson’s mission as a moralist,” according to Leopold Damrosch, “is to make us stop parroting the precepts of moralists and start thinking for ourselves” (81). The movement Damrosch describes from received precepts to the reader’s thoughtful reconsideration of them highlights individual moral agency to a greater degree than the more sociable ethos expressed (and modeled) throughout the Tatler and Spectator . Mark E. Wildermuth’s consideration of the religious dimensions of Johnson’s style in the Rambler likewise points to the series’ primary focus on individual moral and intellectual development. Each essay aims, he notes, “to expand our moral consciousness by prompting us to consider different kinds of perspectives, the human and the divine, the relative and the absolute, in order more fully to comprehend the spiritual and ethical significance of our behavior” (229). The rhetorical pattern Johnson used to try to catalyze this new comprehension is remarkably consistent throughout: over half of the Rambler ’s 208 essays (114, to be exact) begin by asserting a general idea or precept, which is then subjected to minute inquiry to ascertain just how far it applies to the vagaries of human experience. Of the remaining ninety-four essays, sixty-five are epistles from fictitious readers, with the rest comprising literary criticism (mostly of Milton’s verse and the folly of pastoralism) and Eastern tales—and even many of these essays revolve around common assumptions which Johnson proceeds to question. Whereas Addison and Steele primarily sought to make their readers better, more thoughtful citizens, Johnson wants his readers to adjust their expectations, and come to self-understanding, via a rational, gently skeptical, Christian morality. Only thus prepared, the Rambler insists, can readers fortify themselves against the fashionable caprices and material temptations of a superficial world.

The Religiosity of the Rambler

Johnson’s critical concern with the power of inherited opinion is unique in the history of the British periodical essay. The Rambler ’s musings often proceed either from a universal principle identified by one of the ancients (Cicero or Horace, usually) or from a long-held belief with which most would automatically agree. Over 20 percent of the essays, in fact, begin with some variant of the formulation “It has long been observed …” (Yale Works , vol. iv, 92), or “Nothing has been longer observed …” (vol. v, 172). This pattern, along with the wandering quality of the essays’ ruminations, speaks to Johnson’s intent to lay bare for readers how they might critically examine the validity of truisms and adapt them to more productive uses. Rambler 29, for instance, begins by asserting that “There is nothing recommended with greater frequency among the gayer poets of antiquity, than the secure possession of the present hour, and the dismission of all the cares which intrude upon our quiet” and ends with the Christian moral that “if we neglect the duties” of the present “to make provision against visionary attacks, we shall certainly counteract our own purpose” (vol. iii, 158–62). In a movement typical of the series, a pagan carpe diem ethos is surprisingly transformed, via a process of rational sifting and refinement, into a call to live a virtuous Christian life. Following ancient sensualist practice is, of course, absurd for those living with the benefits of Christianity, Johnson avers; yet “the incitements to pleasure are, in these authors, generally mingled with such reflections upon life, as well deserve to be considered distinctly from the purposes for which they are produced.” The essay then moves through arguments concerning the paralytic effects of an “idle and thoughtless resignation to chance”; the reason why “a wise man is not amazed at sudden occurrences” (because he “never considered things not yet existing as the proper objects of his attention,” not because he has special insight into “futurity”); and how the traditional moralists’ check to “the swellings of vain hope by representations of the innumerable casualties to which life is subject” can work equally well as “an antidote to fear” of the unknown by reinforcing just how much of life exceeds our control. It ends by musing on how indulging imaginary fears prevents us from recognizing that every moment offers opportunities for the work of moral improvement, the only real route to “human happiness”—a conception of the good, and of the means of attaining it, far afield from the essay’s opening precept. But the essential point—that worrying about an unknowable future prevents us from living the good life, however we conceive it—abides through all the philosophical and religious transmutations to which Johnson rigorously subjects it.

The Rambler ’s method of testing and qualifying received moral wisdom is brought to bear on even the hoariest sentiments, such as the universality of the “wish for riches.” Rambler 131 (Yale Works , vol. iv, 331–5) begins by affirming that “Wealth is the general center of inclination, the point to which all minds preserve an invariable tendency.” There’s good reason for this, as “No desire can be formed which riches do not assist or gratify”; and it follows that since wealth is the surest means to gratification, the temptation to acquire it via “subtilty and dishonesty” is nearly as universal as the desire for wealth itself. After several paragraphs detailing the social ramifications of this problem (general unease, endemic fraud, the unfortunate “punctilious minuteness” of contracts), the essay concludes by facing up to the stubborn fact of inequality, which exacerbates the universal desire for riches. While we might pine for a lost “golden age” and its “community of possessions,” Johnson posits, it has vanished forever along with the “spontaneity of production” which made it possible. For production has long since depended on labor, and in spite of the “multitudes” who “strive to pluck the fruit without cultivating the tree,” “property” rightfully accrues to those who work for it. Readers determined not to resort to fraud, nor to take “vows of perpetual poverty” (which Johnson dismisses as an unproductive escape into “inactivity and uselessness”), are left with one course of action: to embrace “riches” as a means “necessary to present convenience” while adhering rigorously to “justice, veracity, and piety” in the pursuit and use of them. The intellectual loop Johnson runs here, like that of Rambler 29 and so many others, takes readers from an inherited truism, through a variety of instances which account for and test it, and back to the original proposition seen anew from the solid, common-sense grounding of basic Christian morality. It’s a form of baptism-by-argument, plunging readers into the fluid medium of worldly knowledge illuminated by Christian piety, from which they emerge with new perspectives on themselves, and their moral-cultural inheritance.

The Adventurer and the Universal Chronicle

The Rambler ’s pervasive religiosity, however moderated by the genre’s customary worldliness, is new to the periodical essay. While subsequent series like the World , the Connoisseur , and the Lounger would revert to the less religious, topical-satiric mode associated with the Tatler and Spectator , the next significant London half-sheet essay periodical the Adventurer (1752–4) carried on the religious turn—not surprisingly, given that Johnson wrote for it. Started by John Hawkesworth, who had succeeded Johnson as parliamentary reporter for the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1744 and would go on to literary fame for his edition of Swift’s works (1765–6) and The Three Voyages of Captain Cook (1773–84), the series was also brought out by John Payne, the Rambler ’s publisher. Johnson wrote roughly a quarter of its 140 numbers, as did Joseph Warton; Hawkesworth was responsible for most of the rest, with assistance on a few papers from Bonnell Thornton (who would shortly begin the Connoisseur with George Coleman) and several others—all anonymously. According to Payne, the Adventurer ’s “ultimate design … [was] to promote the practice of piety and virtue upon the principles of Christianity; yet in such a manner that they for whose benefit it is chiefly intended may not be tempted to throw it aside”: in other words, to do what the Rambler did. 10 And it succeeded, for the Adventurer initially outsold the Rambler in both its original sheets and its first folio and duodecimo editions. The series followed its predecessor, too, in presenting itself—even more explicitly—as a collection designed with posterity in mind. A note at the end of the Adventurer ’s first essay informed readers that “These Numbers will be formed into regular Volumes, to each of which will be printed a Title, a Table of Contents, and a Translation of the Mottos and Quotations”; another at the bottom of no. 70 reads “End of the First Volume”; and the last essay notes that “when [the Adventurer ] was first planned, it was determined, that, whatever might be the success, it should not be continued as a paper, till it became unwieldy as a book.” 11 Though now known only to the most devoted eighteenth-century specialist (and even then only for the twenty-nine essays Johnson had anonymously authored), editions of the Adventurer were reprinted nearly as often as those of the Rambler through the 1790s. 12 The explicit religiosity of both, however, remained unique; only the Looker-On (1792–3), a half-sheet essay series which later marshaled Christian piety against the immediate threat of Jacobin infidelity, would work in a similar vein.

Even as Johnson can claim to have revived the periodical essay with the Rambler , the mid-century literary marketplace remained a difficult environment for such ventures. The World and Connoisseur were singularly successful, publishing as weekly sheets for four and nearly three years, respectively, but the rest of the essay series that followed the Adventurer were either short-lived or first appeared as columns in magazines and reviews, and then quickly forgotten. Johnson, too, capitulated to the realities of the market and published the Idler in the Universal Chronicle , a weekly review that appeared every Saturday from April 15, 1758 to April 5, 1760. The details of Johnson’s involvement in the paper beyond writing the Idler are murky, but Payne published the first thirty numbers, after which the Chronicle underwent two changes in publishing arrangements until it finally folded with its 104th number. Each issue ran eight pages, printed in three columns, and began with an Idler essay. Highlights from the week’s news culled from other papers followed, mostly centered on London, though coverage of events in Scotland, Ireland, and foreign countries featured as well, along with poems and political essays, and advertisements (which appeared regularly after Payne gave up the paper). While the Chronicle struggled to find readers, a number of Idler essays were widely reprinted in other newspapers and magazines during the paper’s run; and volumes of the series were brought out over a dozen times through the end of the century, in addition to being included in Harrison’s and Parsons’s collections of “classicks.” So the Idler was another measured success for Johnson in this genre.

Critically, the Idler has been treated as an afterthought. Walter Jackson Bate’s remark that “the confirmed Johnsonian finds them thin” (Yale Works , vol. ii, xix) has colored reception of the essays ever since, to the extent that while the Rambler ’s critical bibliography runs to over fifty published entries, there are only seven article-length studies devoted to the Idler . 13 An unconfirmed Johnsonian, however, can discern in the Idler ’s lighter touch and more consistent engagement with Town life Johnson’s purposeful return to the established conventions of the periodical essay. Like the Rambler , the Idler features literary criticism, Eastern tales, and general moral reflections. Since Idler essays are shorter, the critical pieces mostly focus on broad evaluative principles instead of meticulously analyzing verse structure as in the Rambler ’s Milton essays. The Idler ’s early numbers also deal explicitly with current events, the series having begun nearly two years into the Seven Years’ War (essays 5 through 8 concern the war, a topical focus nowhere evident in the Rambler ). Bate argues that while this topical turn indicates that Johnson initially wanted to distinguish the new series from its predecessor, the Idler ’s reversion in later numbers to universal subjects and literary criticism suggests that Johnson found it easier in the end to rely on the approach he had pioneered in the Rambler . Given Johnson’s habitual indolence and pressure to continue working on his Shakespeare edition, this seems plausible. But the pervasive differences between the two series imply that Johnson wanted to explore a side of the genre that he had de-emphasized in the Rambler .

Though it lacks the Rambler ’s analytical rigor, the Idler translates its predecessor’s concern with self-scrutiny into a more humorous, workaday idiom. Between the Adventurer ’s last and the Idler ’s first number, the World and the Connoisseur had infused the periodical essay with a sharper sense of irony and satire. Both series present a London public marked by shallow and materialistic self-absorption that, especially in the Connoisseur , reflects the failure of the Spectator and other periodical essays to make good on the genre’s promise to create thoughtful, reflective citizens. 14 The gleeful irreverence with which they skewered the pretentions of Town life, though far afield from the pious sobriety we associate with the Rambler , seems to have registered with Johnson as he embarked on his final essay series, which is indeed marked by a greater “satiric impulse” (O’Flaherty, “Johnson’s Idler ,” 213). But the Idler ’s gentle satires of ordinary foibles suggest that Johnson strove to mitigate the barbed severity of the World and Connoisseur by restoring to the periodical essay the more tolerant and sociable tenor of Addison’s and Steele’s work.