- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Critical Reviews

How to Write an Article Review (With Examples)

Last Updated: April 24, 2024 Fact Checked

Preparing to Write Your Review

Writing the article review, sample article reviews, expert q&a.

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 3,100,459 times.

An article review is both a summary and an evaluation of another writer's article. Teachers often assign article reviews to introduce students to the work of experts in the field. Experts also are often asked to review the work of other professionals. Understanding the main points and arguments of the article is essential for an accurate summation. Logical evaluation of the article's main theme, supporting arguments, and implications for further research is an important element of a review . Here are a few guidelines for writing an article review.

Education specialist Alexander Peterman recommends: "In the case of a review, your objective should be to reflect on the effectiveness of what has already been written, rather than writing to inform your audience about a subject."

Article Review 101

- Read the article very closely, and then take time to reflect on your evaluation. Consider whether the article effectively achieves what it set out to.

- Write out a full article review by completing your intro, summary, evaluation, and conclusion. Don't forget to add a title, too!

- Proofread your review for mistakes (like grammar and usage), while also cutting down on needless information.

- Article reviews present more than just an opinion. You will engage with the text to create a response to the scholarly writer's ideas. You will respond to and use ideas, theories, and research from your studies. Your critique of the article will be based on proof and your own thoughtful reasoning.

- An article review only responds to the author's research. It typically does not provide any new research. However, if you are correcting misleading or otherwise incorrect points, some new data may be presented.

- An article review both summarizes and evaluates the article.

- Summarize the article. Focus on the important points, claims, and information.

- Discuss the positive aspects of the article. Think about what the author does well, good points she makes, and insightful observations.

- Identify contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the text. Determine if there is enough data or research included to support the author's claims. Find any unanswered questions left in the article.

- Make note of words or issues you don't understand and questions you have.

- Look up terms or concepts you are unfamiliar with, so you can fully understand the article. Read about concepts in-depth to make sure you understand their full context.

- Pay careful attention to the meaning of the article. Make sure you fully understand the article. The only way to write a good article review is to understand the article.

- With either method, make an outline of the main points made in the article and the supporting research or arguments. It is strictly a restatement of the main points of the article and does not include your opinions.

- After putting the article in your own words, decide which parts of the article you want to discuss in your review. You can focus on the theoretical approach, the content, the presentation or interpretation of evidence, or the style. You will always discuss the main issues of the article, but you can sometimes also focus on certain aspects. This comes in handy if you want to focus the review towards the content of a course.

- Review the summary outline to eliminate unnecessary items. Erase or cross out the less important arguments or supplemental information. Your revised summary can serve as the basis for the summary you provide at the beginning of your review.

- What does the article set out to do?

- What is the theoretical framework or assumptions?

- Are the central concepts clearly defined?

- How adequate is the evidence?

- How does the article fit into the literature and field?

- Does it advance the knowledge of the subject?

- How clear is the author's writing? Don't: include superficial opinions or your personal reaction. Do: pay attention to your biases, so you can overcome them.

- For example, in MLA , a citation may look like: Duvall, John N. "The (Super)Marketplace of Images: Television as Unmediated Mediation in DeLillo's White Noise ." Arizona Quarterly 50.3 (1994): 127-53. Print. [9] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For example: The article, "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS," was written by Anthony Zimmerman, a Catholic priest.

- Your introduction should only be 10-25% of your review.

- End the introduction with your thesis. Your thesis should address the above issues. For example: Although the author has some good points, his article is biased and contains some misinterpretation of data from others’ analysis of the effectiveness of the condom.

- Use direct quotes from the author sparingly.

- Review the summary you have written. Read over your summary many times to ensure that your words are an accurate description of the author's article.

- Support your critique with evidence from the article or other texts.

- The summary portion is very important for your critique. You must make the author's argument clear in the summary section for your evaluation to make sense.

- Remember, this is not where you say if you liked the article or not. You are assessing the significance and relevance of the article.

- Use a topic sentence and supportive arguments for each opinion. For example, you might address a particular strength in the first sentence of the opinion section, followed by several sentences elaborating on the significance of the point.

- This should only be about 10% of your overall essay.

- For example: This critical review has evaluated the article "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS" by Anthony Zimmerman. The arguments in the article show the presence of bias, prejudice, argumentative writing without supporting details, and misinformation. These points weaken the author’s arguments and reduce his credibility.

- Make sure you have identified and discussed the 3-4 key issues in the article.

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://libguides.cmich.edu/writinghelp/articlereview

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548566/

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 24 July 2020.

- ↑ https://guides.library.queensu.ca/introduction-research/writing/critical

- ↑ https://www.iup.edu/writingcenter/writing-resources/organization-and-structure/creating-an-outline.html

- ↑ https://writing.umn.edu/sws/assets/pdf/quicktips/titles.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_works_cited_periodicals.html

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548565/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/593/2014/06/How_to_Summarize_a_Research_Article1.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uis.edu/learning-hub/writing-resources/handouts/learning-hub/how-to-review-a-journal-article

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

If you have to write an article review, read through the original article closely, taking notes and highlighting important sections as you read. Next, rewrite the article in your own words, either in a long paragraph or as an outline. Open your article review by citing the article, then write an introduction which states the article’s thesis. Next, summarize the article, followed by your opinion about whether the article was clear, thorough, and useful. Finish with a paragraph that summarizes the main points of the article and your opinions. To learn more about what to include in your personal critique of the article, keep reading the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Prince Asiedu-Gyan

Apr 22, 2022

Did this article help you?

Sammy James

Sep 12, 2017

Juabin Matey

Aug 30, 2017

Vanita Meghrajani

Jul 21, 2016

Nov 27, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

How to Write an Article Review: Tips and Examples

Did you know that article reviews are not just academic exercises but also a valuable skill in today's information age? In a world inundated with content, being able to dissect and evaluate articles critically can help you separate the wheat from the chaff. Whether you're a student aiming to excel in your coursework or a professional looking to stay well-informed, mastering the art of writing article reviews is an invaluable skill.

Short Description

In this article, our research paper writing service experts will start by unraveling the concept of article reviews and discussing the various types. You'll also gain insights into the art of formatting your review effectively. To ensure you're well-prepared, we'll take you through the pre-writing process, offering tips on setting the stage for your review. But it doesn't stop there. You'll find a practical example of an article review to help you grasp the concepts in action. To complete your journey, we'll guide you through the post-writing process, equipping you with essential proofreading techniques to ensure your work shines with clarity and precision!

What Is an Article Review: Grasping the Concept

A review article is a type of professional paper writing that demands a high level of in-depth analysis and a well-structured presentation of arguments. It is a critical, constructive evaluation of literature in a particular field through summary, classification, analysis, and comparison.

If you write a scientific review, you have to use database searches to portray the research. Your primary goal is to summarize everything and present a clear understanding of the topic you've been working on.

Writing Involves:

- Summarization, classification, analysis, critiques, and comparison.

- The analysis, evaluation, and comparison require the use of theories, ideas, and research relevant to the subject area of the article.

- It is also worth nothing if a review does not introduce new information, but instead presents a response to another writer's work.

- Check out other samples to gain a better understanding of how to review the article.

Types of Review

When it comes to article reviews, there's more than one way to approach the task. Understanding the various types of reviews is like having a versatile toolkit at your disposal. In this section, we'll walk you through the different dimensions of review types, each offering a unique perspective and purpose. Whether you're dissecting a scholarly article, critiquing a piece of literature, or evaluating a product, you'll discover the diverse landscape of article reviews and how to navigate it effectively.

.webp)

Journal Article Review

Just like other types of reviews, a journal article review assesses the merits and shortcomings of a published work. To illustrate, consider a review of an academic paper on climate change, where the writer meticulously analyzes and interprets the article's significance within the context of environmental science.

Research Article Review

Distinguished by its focus on research methodologies, a research article review scrutinizes the techniques used in a study and evaluates them in light of the subsequent analysis and critique. For instance, when reviewing a research article on the effects of a new drug, the reviewer would delve into the methods employed to gather data and assess their reliability.

Science Article Review

In the realm of scientific literature, a science article review encompasses a wide array of subjects. Scientific publications often provide extensive background information, which can be instrumental in conducting a comprehensive analysis. For example, when reviewing an article about the latest breakthroughs in genetics, the reviewer may draw upon the background knowledge provided to facilitate a more in-depth evaluation of the publication.

Need a Hand From Professionals?

Address to Our Writers and Get Assistance in Any Questions!

Formatting an Article Review

The format of the article should always adhere to the citation style required by your professor. If you're not sure, seek clarification on the preferred format and ask him to clarify several other pointers to complete the formatting of an article review adequately.

How Many Publications Should You Review?

- In what format should you cite your articles (MLA, APA, ASA, Chicago, etc.)?

- What length should your review be?

- Should you include a summary, critique, or personal opinion in your assignment?

- Do you need to call attention to a theme or central idea within the articles?

- Does your instructor require background information?

When you know the answers to these questions, you may start writing your assignment. Below are examples of MLA and APA formats, as those are the two most common citation styles.

Using the APA Format

Articles appear most commonly in academic journals, newspapers, and websites. If you write an article review in the APA format, you will need to write bibliographical entries for the sources you use:

- Web : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Year, Month, Date of Publication). Title. Retrieved from {link}

- Journal : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Publication Year). Publication Title. Periodical Title, Volume(Issue), pp.-pp.

- Newspaper : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Year, Month, Date of Publication). Publication Title. Magazine Title, pp. xx-xx.

Using MLA Format

- Web : Last, First Middle Initial. “Publication Title.” Website Title. Website Publisher, Date Month Year Published. Web. Date Month Year Accessed.

- Newspaper : Last, First M. “Publication Title.” Newspaper Title [City] Date, Month, Year Published: Page(s). Print.

- Journal : Last, First M. “Publication Title.” Journal Title Series Volume. Issue (Year Published): Page(s). Database Name. Web. Date Month Year Accessed.

Enhance your writing effortlessly with EssayPro.com , where you can order an article review or any other writing task. Our team of expert writers specializes in various fields, ensuring your work is not just summarized, but deeply analyzed and professionally presented. Ideal for students and professionals alike, EssayPro offers top-notch writing assistance tailored to your needs. Elevate your writing today with our skilled team at your article review writing service !

.jpg)

The Pre-Writing Process

Facing this task for the first time can really get confusing and can leave you unsure of where to begin. To create a top-notch article review, start with a few preparatory steps. Here are the two main stages from our dissertation services to get you started:

Step 1: Define the right organization for your review. Knowing the future setup of your paper will help you define how you should read the article. Here are the steps to follow:

- Summarize the article — seek out the main points, ideas, claims, and general information presented in the article.

- Define the positive points — identify the strong aspects, ideas, and insightful observations the author has made.

- Find the gaps —- determine whether or not the author has any contradictions, gaps, or inconsistencies in the article and evaluate whether or not he or she used a sufficient amount of arguments and information to support his or her ideas.

- Identify unanswered questions — finally, identify if there are any questions left unanswered after reading the piece.

Step 2: Move on and review the article. Here is a small and simple guide to help you do it right:

- Start off by looking at and assessing the title of the piece, its abstract, introductory part, headings and subheadings, opening sentences in its paragraphs, and its conclusion.

- First, read only the beginning and the ending of the piece (introduction and conclusion). These are the parts where authors include all of their key arguments and points. Therefore, if you start with reading these parts, it will give you a good sense of the author's main points.

- Finally, read the article fully.

These three steps make up most of the prewriting process. After you are done with them, you can move on to writing your own review—and we are going to guide you through the writing process as well.

Outline and Template

As you progress with reading your article, organize your thoughts into coherent sections in an outline. As you read, jot down important facts, contributions, or contradictions. Identify the shortcomings and strengths of your publication. Begin to map your outline accordingly.

If your professor does not want a summary section or a personal critique section, then you must alleviate those parts from your writing. Much like other assignments, an article review must contain an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Thus, you might consider dividing your outline according to these sections as well as subheadings within the body. If you find yourself troubled with the pre-writing and the brainstorming process for this assignment, seek out a sample outline.

Your custom essay must contain these constituent parts:

- Pre-Title Page - Before diving into your review, start with essential details: article type, publication title, and author names with affiliations (position, department, institution, location, and email). Include corresponding author info if needed.

- Running Head - In APA format, use a concise title (under 40 characters) to ensure consistent formatting.

- Summary Page - Optional but useful. Summarize the article in 800 words, covering background, purpose, results, and methodology, avoiding verbatim text or references.

- Title Page - Include the full title, a 250-word abstract, and 4-6 keywords for discoverability.

- Introduction - Set the stage with an engaging overview of the article.

- Body - Organize your analysis with headings and subheadings.

- Works Cited/References - Properly cite all sources used in your review.

- Optional Suggested Reading Page - If permitted, suggest further readings for in-depth exploration.

- Tables and Figure Legends (if instructed by the professor) - Include visuals when requested by your professor for clarity.

Example of an Article Review

You might wonder why we've dedicated a section of this article to discuss an article review sample. Not everyone may realize it, but examining multiple well-constructed examples of review articles is a crucial step in the writing process. In the following section, our essay writing service experts will explain why.

Looking through relevant article review examples can be beneficial for you in the following ways:

- To get you introduced to the key works of experts in your field.

- To help you identify the key people engaged in a particular field of science.

- To help you define what significant discoveries and advances were made in your field.

- To help you unveil the major gaps within the existing knowledge of your field—which contributes to finding fresh solutions.

- To help you find solid references and arguments for your own review.

- To help you generate some ideas about any further field of research.

- To help you gain a better understanding of the area and become an expert in this specific field.

- To get a clear idea of how to write a good review.

View Our Writer’s Sample Before Crafting Your Own!

Why Have There Been No Great Female Artists?

Steps for Writing an Article Review

Here is a guide with critique paper format on how to write a review paper:

.webp)

Step 1: Write the Title

First of all, you need to write a title that reflects the main focus of your work. Respectively, the title can be either interrogative, descriptive, or declarative.

Step 2: Cite the Article

Next, create a proper citation for the reviewed article and input it following the title. At this step, the most important thing to keep in mind is the style of citation specified by your instructor in the requirements for the paper. For example, an article citation in the MLA style should look as follows:

Author's last and first name. "The title of the article." Journal's title and issue(publication date): page(s). Print

Abraham John. "The World of Dreams." Virginia Quarterly 60.2(1991): 125-67. Print.

Step 3: Article Identification

After your citation, you need to include the identification of your reviewed article:

- Title of the article

- Title of the journal

- Year of publication

All of this information should be included in the first paragraph of your paper.

The report "Poverty increases school drop-outs" was written by Brian Faith – a Health officer – in 2000.

Step 4: Introduction

Your organization in an assignment like this is of the utmost importance. Before embarking on your writing process, you should outline your assignment or use an article review template to organize your thoughts coherently.

- If you are wondering how to start an article review, begin with an introduction that mentions the article and your thesis for the review.

- Follow up with a summary of the main points of the article.

- Highlight the positive aspects and facts presented in the publication.

- Critique the publication by identifying gaps, contradictions, disparities in the text, and unanswered questions.

Step 5: Summarize the Article

Make a summary of the article by revisiting what the author has written about. Note any relevant facts and findings from the article. Include the author's conclusions in this section.

Step 6: Critique It

Present the strengths and weaknesses you have found in the publication. Highlight the knowledge that the author has contributed to the field. Also, write about any gaps and/or contradictions you have found in the article. Take a standpoint of either supporting or not supporting the author's assertions, but back up your arguments with facts and relevant theories that are pertinent to that area of knowledge. Rubrics and templates can also be used to evaluate and grade the person who wrote the article.

Step 7: Craft a Conclusion

In this section, revisit the critical points of your piece, your findings in the article, and your critique. Also, write about the accuracy, validity, and relevance of the results of the article review. Present a way forward for future research in the field of study. Before submitting your article, keep these pointers in mind:

- As you read the article, highlight the key points. This will help you pinpoint the article's main argument and the evidence that they used to support that argument.

- While you write your review, use evidence from your sources to make a point. This is best done using direct quotations.

- Select quotes and supporting evidence adequately and use direct quotations sparingly. Take time to analyze the article adequately.

- Every time you reference a publication or use a direct quotation, use a parenthetical citation to avoid accidentally plagiarizing your article.

- Re-read your piece a day after you finish writing it. This will help you to spot grammar mistakes and to notice any flaws in your organization.

- Use a spell-checker and get a second opinion on your paper.

The Post-Writing Process: Proofread Your Work

Finally, when all of the parts of your article review are set and ready, you have one last thing to take care of — proofreading. Although students often neglect this step, proofreading is a vital part of the writing process and will help you polish your paper to ensure that there are no mistakes or inconsistencies.

To proofread your paper properly, start by reading it fully and checking the following points:

- Punctuation

- Other mistakes

Afterward, take a moment to check for any unnecessary information in your paper and, if found, consider removing it to streamline your content. Finally, double-check that you've covered at least 3-4 key points in your discussion.

And remember, if you ever need help with proofreading, rewriting your essay, or even want to buy essay , our friendly team is always here to assist you.

Need an Article REVIEW WRITTEN?

Just send us the requirements to your paper and watch one of our writers crafting an original paper for you.

What Is A Review Article?

How to write an article review, how to write an article review in apa format, related articles.

.webp)

Lesson Plan on Writing an Article Review: Includes Rubric

- Trent Lorcher

- Categories : High school english lesson plans grades 9 12

- Tags : High school lesson plans & tips

Most students do not know how to write an article review, an important skill for writing research papers. This simple lesson plan helps build this vital skill. A good article review contains a summary of the article with a personal response supported by evidence and reason.

Description

When critiquing an article, students should demonstrate their awareness of any bias or prejudice, identify pros and cons of the writer’s position, and discuss if they would recommend the article to others. They can also practice research skills by writing a bibliographic citation.

Instructions

- Take students to the library and have them choose articles (option 1).

- Choose articles of varying difficulty for students (option 2).

- Give several examples .

- Have students point out bias and comment on the author’s position.

Quality Checklist

- Have I organized the article review in a logical fashion with ideas clearly and concisely stated?

- Does all information follow correct bibliographic format?

- Does the summary include a brief explanation of the article which includes the author’s point of view?

- Does the critique of the article include evidence of bias, my own or the author’s, identify the pros and cons of the article, and indicate my recommendation?

- Have I summarized my personal response in a concluding statement?

‘‘A’ REVIEW

- Organization: The article is organized and ideas are clearly stated

- Bibliographic Information: All the information follows the bibliographic format given.

- Summary: Examples are clear and accurate. There are reasons and/or details to support personal reaction.

- Critique: Concluding statement creatively and clearly summarizes the personal response.

- Organization: Ideas are clearly stated, but the review lacks solid organization.

- Bibliographic Information: Information exists but the format is not followed.

- Summary: Examples are accurate. There are reasons and/or details to support personal reaction.

- Critique: Concluding statement clearly summarizes the personal response.

- Organization: Ideas are clear but article takes too long to make a point. Article lacks organization.

- Bibliographic Information: Some required information is missing.

- Summary: Inaccurate examples. There are reasons and/or details to support personal reaction.

- Critique: Concluding statement does not clearly summarize the personal response.

- Organization: Ideas are not clear. Article rambles.

- Bibliographic information: not provided.

- Summary: There are few or no examples to support personal response.

- Critique: Contains no concluding statement or one that does not summarize the personal response.

This post is part of the series: Writing Lesson Plans

Teach writing with these writing lesson plans.

- Lesson Plan: How to Write a Cause and Effect Essay

- Writing a Mystery Lesson Plan

- Lesson Plan: How to Write a Tall Tale

- Lesson Plan: Writing Effective Dialogue

- Lesson Plan: How to Write an Article Review

How to Write an Article Review: Template & Examples

An article review is an academic assignment that invites you to study a piece of academic research closely. Then, you should present its summary and critically evaluate it using the knowledge you’ve gained in class and during your independent study. If you get such a task at college or university, you shouldn’t confuse it with a response paper, which is a distinct assignment with other purposes (we’ll talk about it in detail below).

Our specialists will write a custom essay specially for you!

In this article, prepared by Custom-Writing experts, you’ll find:

- the intricacies of article review writing;

- the difference between an article review and similar assignments;

- a step-by-step algorithm for review composition;

- a couple of samples to guide you throughout the writing process.

So, if you wish to study our article review example and discover helpful writing tips, keep reading.

❓ What Is an Article Review?

- ✍️ Writing Steps

📑 Article Review Format

🔗 references.

An article review is an academic paper that summarizes and critically evaluates the information presented in your selected article.

The first thing you should note when approaching the task of an article review is that not every article is suitable for this assignment. Let’s have a look at the variety of articles to understand what you can choose from.

Popular Vs. Scholarly Articles

In most cases, you’ll be required to review a scholarly, peer-reviewed article – one composed in compliance with rigorous academic standards. Yet, the Web is also full of popular articles that don’t present original scientific value and shouldn’t be selected for a review.

Just in 1 hour! We will write you a plagiarism-free paper in hardly more than 1 hour

Not sure how to distinguish these two types? Here is a comparative table to help you out.

Article Review vs. Response Paper

Now, let’s consider the difference between an article review and a response paper:

- If you’re assigned to critique a scholarly article , you will need to compose an article review .

- If your subject of analysis is a popular article , you can respond to it with a well-crafted response paper .

The reason for such distinctions is the quality and structure of these two article types. Peer-reviewed, scholarly articles have clear-cut quality criteria, allowing you to conduct and present a structured assessment of the assigned material. Popular magazines have loose or non-existent quality criteria and don’t offer an opportunity for structured evaluation. So, they are only fit for a subjective response, in which you can summarize your reactions and emotions related to the reading material.

All in all, you can structure your response assignments as outlined in the tips below.

✍️ How to Write an Article Review: Step by Step

Here is a tried and tested algorithm for article review writing from our experts. We’ll consider only the critical review variety of this academic assignment. So, let’s get down to the stages you need to cover to get a stellar review.

Receive a plagiarism-free paper tailored to your instructions. Cut 15% off your first order!

Read the Article

As with any reviews, reports, and critiques, you must first familiarize yourself with the assigned material. It’s impossible to review something you haven’t read, so set some time for close, careful reading of the article to identify:

- The author’s main points and message.

- The arguments they use to prove their points.

- The methodology they use to approach the subject.

In terms of research type , your article will usually belong to one of three types explained below.

Summarize the Article

Now that you’ve read the text and have a general impression of the content, it’s time to summarize it for your readers. Look into the article’s text closely to determine:

- The thesis statement , or general message of the author.

- Research question, purpose, and context of research.

- Supporting points for the author’s assumptions and claims.

- Major findings and supporting evidence.

As you study the article thoroughly, make notes on the margins or write these elements out on a sheet of paper. You can also apply a different technique: read the text section by section and formulate its gist in one phrase or sentence. Once you’re done, you’ll have a summary skeleton in front of you.

Evaluate the Article

The next step of review is content evaluation. Keep in mind that various research types will require a different set of review questions. Here is a complete list of evaluation points you can include.

Get an originally-written paper according to your instructions!

Write the Text

After completing the critical review stage, it’s time to compose your article review.

The format of this assignment is standard – you will have an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. The introduction should present your article and summarize its content. The body will contain a structured review according to all four dimensions covered in the previous section. The concluding part will typically recap all the main points you’ve identified during your assessment.

It is essential to note that an article review is, first of all, an academic assignment. Therefore, it should follow all rules and conventions of academic composition, such as:

- No contractions . Don’t use short forms, such as “don’t,” “can’t,” “I’ll,” etc. in academic writing. You need to spell out all those words.

- Formal language and style . Avoid conversational phrasing and words that you would naturally use in blog posts or informal communication. For example, don’t use words like “pretty,” “kind of,” and “like.”

- Third-person narrative . Academic reviews should be written from the third-person point of view, avoiding statements like “I think,” “in my opinion,” and so on.

- No conversational forms . You shouldn’t turn to your readers directly in the text by addressing them with the pronoun “you.” It’s vital to keep the narrative neutral and impersonal.

- Proper abbreviation use . Consult the list of correct abbreviations , like “e.g.” or “i.e.,” for use in your academic writing. If you use informal abbreviations like “FYA” or “f.i.,” your professor will reduce the grade.

- Complete sentences . Make sure your sentences contain the subject and the predicate; avoid shortened or sketch-form phrases suitable for a draft only.

- No conjunctions at the beginning of a sentence . Remember the FANBOYS rule – don’t start a sentence with words like “and” or “but.” They often seem the right way to build a coherent narrative, but academic writing rules disfavor such usage.

- No abbreviations or figures at the beginning of a sentence . Never start a sentence with a number — spell it out if you need to use it anyway. Besides, sentences should never begin with abbreviations like “e.g.”

Finally, a vital rule for an article review is properly formatting the citations. We’ll discuss the correct use of citation styles in the following section.

When composing an article review, keep these points in mind:

- Start with a full reference to the reviewed article so the reader can locate it quickly.

- Ensure correct formatting of in-text references.

- Provide a complete list of used external sources on the last page of the review – your bibliographical entries .

You’ll need to understand the rules of your chosen citation style to meet all these requirements. Below, we’ll discuss the two most common referencing styles – APA and MLA.

Article Review in APA

When you need to compose an article review in the APA format , here is the general bibliographical entry format you should use for journal articles on your reference page:

- Author’s last name, First initial. Middle initial. (Year of Publication). Name of the article. Name of the Journal, volume (number), pp. #-#. https://doi.org/xx.xxx/yyyy

Horigian, V. E., Schmidt, R. D., & Feaster, D. J. (2021). Loneliness, mental health, and substance use among US young adults during COVID-19. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 53 (1), pp. 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1836435

Your in-text citations should follow the author-date format like this:

- If you paraphrase the source and mention the author in the text: According to Horigian et al. (2021), young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic.

- If you paraphrase the source and don’t mention the author in the text: Young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic (Horigian et al., 2021).

- If you quote the source: As Horigian et al. (2021) point out, there were “elevated levels of loneliness, depression, anxiety, alcohol use, and drug use among young adults during COVID-19” (p. 6).

Note that your in-text citations should include “et al.,” as in the examples above, if your article has 3 or more authors. If you have one or two authors, your in-text citations would look like this:

- One author: “According to Smith (2020), depression is…” or “Depression is … (Smith, 2020).”

- Two authors: “According to Smith and Brown (2020), anxiety means…” or “Anxiety means (Smith & Brown, 2020).”

Finally, in case you have to review a book or a website article, here are the general formats for citing these source types on your APA reference list.

Article Review in MLA

If your assignment requires MLA-format referencing, here’s the general format you should use for citing journal articles on your Works Cited page:

- Author’s last name, First name. “Title of an Article.” Title of the Journal , vol. #, no. #, year, pp. #-#.

Horigian, Viviana E., et al. “Loneliness, Mental Health, and Substance Use Among US Young Adults During COVID-19.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs , vol. 53, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-9.

In-text citations in the MLA format follow the author-page citation format and look like this:

- According to Horigian et al., young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic (6).

- Young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic (Horigian et al. 6).

Like in APA, the abbreviation “et al.” is only needed in MLA if your article has 3 or more authors.

If you need to cite a book or a website page, here are the general MLA formats for these types of sources.

✅ Article Review Template

Here is a handy, universal article review template to help you move on with any review assignment. We’ve tried to make it as generic as possible to guide you in the academic process.

📝 Article Review Examples

The theory is good, but practice is even better. Thus, we’ve created three brief examples to show you how to write an article review. You can study the full-text samples by following the links.

📃 Men, Women, & Money

This article review examines a famous piece, “Men, Women & Money – How the Sexes Differ with Their Finances,” published by Amy Livingston in 2020. The author of this article claims that men generally spend more money than women. She makes this conclusion from a close analysis of gender-specific expenditures across five main categories: food, clothing, cars, entertainment, and general spending patterns. Livingston also looks at men’s approach to saving to argue that counter to the common perception of women’s light-hearted attitude to money, men are those who spend more on average.

📃 When and Why Nationalism Beats Globalism

This is a review of Jonathan Heidt’s 2016 article titled “When and Why Nationalism Beats Globalism,” written as an advocacy of right-wing populism rising in many Western states. The author illustrates the case with the election of Donald Trump as the US President and the rise of right-wing rhetoric in many Western countries. These examples show how nationalist sentiment represents a reaction to global immigration and a failure of globalization.

📃 Sleep Deprivation

This is a review of the American Heart Association’s article titled “The Dangers of Sleep Deprivation.” It discusses how the national organization concerned with the American population’s cardiovascular health links the lack of high-quality sleep to far-reaching health consequences. The organization’s experts reveal how a consistent lack of sleep leads to Alzheimer’s disease development, obesity, type 2 diabetes, etc.

✏️ Article Review FAQ

A high-quality article review should summarize the assigned article’s content and offer data-backed reactions and evaluations of its quality in terms of the article’s purpose, methodology, and data used to argue the main points. It should be detailed, comprehensive, objective, and evidence-based.

The purpose of writing a review is to allow students to reflect on research quality and showcase their critical thinking and evaluation skills. Students should exhibit their mastery of close reading of research publications and their unbiased assessment.

The content of your article review will be the same in any format, with the only difference in the assignment’s formatting before submission. Ensure you have a separate title page made according to APA standards and cite sources using the parenthetical author-date referencing format.

You need to take a closer look at various dimensions of an assigned article to compose a valuable review. Study the author’s object of analysis, the purpose of their research, the chosen method, data, and findings. Evaluate all these dimensions critically to see whether the author has achieved the initial goals. Finally, offer improvement recommendations to add a critique aspect to your paper.

- Scientific Article Review: Duke University

- Book and Article Reviews: William & Mary, Writing Resources Center

- Sample Format for Reviewing a Journal Article: Boonshoft School of Medicine

- Research Paper Review – Structure and Format Guidelines: New Jersey Institute of Technology

- Article Review: University of Waterloo

- Article Review: University of South Australia

- How to Write a Journal Article Review: University of Newcastle Library Guides

- Writing Help: The Article Review: Central Michigan University Libraries

- Write a Critical Review of a Scientific Journal Article: McLaughlin Library

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Short essays answer a specific question on the subject. They usually are anywhere between 250 words and 750 words long. A paper with less than 250 words isn’t considered a finished text, so it doesn’t fall under the category of a short essay. Essays of such format are required for...

High school and college students often face challenges when crafting a compare-and-contrast essay. A well-written paper of this kind needs to be structured appropriately to earn you good grades. Knowing how to organize your ideas allows you to present your ideas in a coherent and logical manner This article by...

If you’re a student, you’ve heard about a formal essay: a factual, research-based paper written in 3rd person. Most students have to produce dozens of them during their educational career. Writing a formal essay may not be the easiest task. But fear not: our custom-writing team is here to guide...

Narrative essays are unlike anything you wrote throughout your academic career. Instead of writing a formal paper, you need to tell a story. Familiar elements such as evidence and arguments are replaced with exposition and character development. The importance of writing an outline for an essay like this is hard...

A précis is a brief synopsis of a written piece. It is used to summarize and analyze a text’s main points. If you need to write a précis for a research paper or the AP Lang exam, you’ve come to the right place. In this comprehensive guide by Custom-Writing.org, you’ll...

A synthesis essay requires you to work with multiple sources. You combine the information gathered from them to present a well-rounded argument on a topic. Are you looking for the ultimate guide on synthesis essay writing? You’ve come to the right place! In this guide by our custom writing team,...

Do you know how to make your essay stand out? One of the easiest ways is to start your introduction with a catchy hook. A hook is a phrase or a sentence that helps to grab the reader’s attention. After reading this article by Custom-Writing.org, you will be able to...

Critical thinking is the process of evaluating and analyzing information. People who use it in everyday life are open to different opinions. They rely on reason and logic when making conclusions about certain issues. A critical thinking essay shows how your thoughts change as you research your topic. This type...

Process analysis is an explanation of how something works or happens. Want to know more? Read the following article prepared by our custom writing specialists and learn about: process analysis and its typesa process analysis outline tipsfree examples and other tips that might be helpful for your college assignment So,...

A visual analysis essay is an academic paper type that history and art students often deal with. It consists of a detailed description of an image or object. It can also include an interpretation or an argument that is supported by visual evidence. In this article, our custom writing experts...

Want to know how to write a reflection paper for college or school? To do that, you need to connect your personal experiences with theoretical knowledge. Usually, students are asked to reflect on a documentary, a text, or their experience. Sometimes one needs to write a paper about a lesson...

A character analysis is an examination of the personalities and actions of protagonists and antagonists that make up a story. It discusses their role in the story, evaluates their traits, and looks at their conflicts and experiences. You might need to write this assignment in school or college. Like any...

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 02 December 2020

Enhancing senior high school student engagement and academic performance using an inclusive and scalable inquiry-based program

- Locke Davenport Huyer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1526-7122 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Neal I. Callaghan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8214-3395 1 , 3 na1 ,

- Sara Dicks 4 ,

- Edward Scherer 4 ,

- Andrey I. Shukalyuk 1 ,

- Margaret Jou 4 &

- Dawn M. Kilkenny ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3899-9767 1 , 5

npj Science of Learning volume 5 , Article number: 17 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

4 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

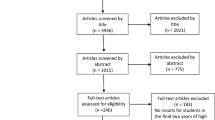

The multi-disciplinary nature of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) careers often renders difficulty for high school students navigating from classroom knowledge to post-secondary pursuits. Discrepancies between the knowledge-based high school learning approach and the experiential approach of future studies leaves some students disillusioned by STEM. We present Discovery , a term-long inquiry-focused learning model delivered by STEM graduate students in collaboration with high school teachers, in the context of biomedical engineering. Entire classes of high school STEM students representing diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds engaged in iterative, problem-based learning designed to emphasize critical thinking concomitantly within the secondary school and university environments. Assessment of grades and survey data suggested positive impact of this learning model on students’ STEM interests and engagement, notably in under-performing cohorts, as well as repeating cohorts that engage in the program on more than one occasion. Discovery presents a scalable platform that stimulates persistence in STEM learning, providing valuable learning opportunities and capturing cohorts of students that might otherwise be under-engaged in STEM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Subject integration and theme evolution of STEM education in K-12 and higher education research

Skill levels and gains in university STEM education in China, India, Russia and the United States

Academic ecosystems must evolve to support a sustainable postdoc workforce

Introduction.

High school students with diverse STEM interests often struggle to understand the STEM experience outside the classroom 1 . The multi-disciplinary nature of many career fields can foster a challenge for students in their decision to enroll in appropriate high school courses while maintaining persistence in study, particularly when these courses are not mandatory 2 . Furthermore, this challenge is amplified by the known discrepancy between the knowledge-based learning approach common in high schools and the experiential, mastery-based approaches afforded by the subsequent undergraduate model 3 . In the latter, focused classes, interdisciplinary concepts, and laboratory experiences allow for the application of accumulated knowledge, practice in problem solving, and development of both general and technical skills 4 . Such immersive cooperative learning environments are difficult to establish in the secondary school setting and high school teachers often struggle to implement within their classroom 5 . As such, high school students may become disillusioned before graduation and never experience an enriched learning environment, despite their inherent interests in STEM 6 .

It cannot be argued that early introduction to varied math and science disciplines throughout high school is vital if students are to pursue STEM fields, especially within engineering 7 . However, the majority of literature focused on student interest and retention in STEM highlights outcomes in US high school learning environments, where the sciences are often subject-specific from the onset of enrollment 8 . In contrast, students in the Ontario (Canada) high school system are required to complete Level 1 and 2 core courses in science and math during Grades 9 and 10; these courses are offered as ‘applied’ or ‘academic’ versions and present broad topics of content 9 . It is not until Levels 3 and 4 (generally Grades 11 and 12, respectively) that STEM classes become subject-specific (i.e., Biology, Chemistry, and/or Physics) and are offered as “university”, “college”, or “mixed” versions, designed to best prepare students for their desired post-secondary pursuits 9 . Given that Levels 3 and 4 science courses are not mandatory for graduation, enrollment identifies an innate student interest in continued learning. Furthermore, engagement in these post-secondary preparatory courses is also dependent upon achieving successful grades in preceding courses, but as curriculum becomes more subject-specific, students often yield lower degrees of success in achieving course credit 2 . Therefore, it is imperative that learning supports are best focused on ensuring that those students with an innate interest are able to achieve success in learning.

When given opportunity and focused support, high school students are capable of successfully completing rigorous programs at STEM-focused schools 10 . Specialized STEM schools have existed in the US for over 100 years; generally, students are admitted after their sophomore year of high school experience (equivalent to Grade 10) based on standardized test scores, essays, portfolios, references, and/or interviews 11 . Common elements to this learning framework include a diverse array of advanced STEM courses, paired with opportunities to engage in and disseminate cutting-edge research 12 . Therein, said research experience is inherently based in the processes of critical thinking, problem solving, and collaboration. This learning framework supports translation of core curricular concepts to practice and is fundamental in allowing students to develop better understanding and appreciation of STEM career fields.

Despite the described positive attributes, many students do not have the ability or resources to engage within STEM-focused schools, particularly given that they are not prevalent across Canada, and other countries across the world. Consequently, many public institutions support the idea that post-secondary led engineering education programs are effective ways to expose high school students to engineering education and relevant career options, and also increase engineering awareness 13 . Although singular class field trips are used extensively to accomplish such programs, these may not allow immersive experiences for application of knowledge and practice of skills that are proven to impact long-term learning and influence career choices 14 , 15 . Longer-term immersive research experiences, such as after-school programs or summer camps, have shown successful at recruiting students into STEM degree programs and careers, where longevity of experience helps foster self-determination and interest-led, inquiry-based projects 4 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 .

Such activities convey the elements that are suggested to make a post-secondary led high school education programs successful: hands-on experience, self-motivated learning, real-life application, immediate feedback, and problem-based projects 20 , 21 . In combination with immersion in university teaching facilities, learning is authentic and relevant, similar to the STEM school-focused framework, and consequently representative of an experience found in actual STEM practice 22 . These outcomes may further be a consequence of student engagement and attitude: Brown et al. studied the relationships between STEM curriculum and student attitudes, and found the latter played a more important role in intention to persist in STEM when compared to self-efficacy 23 . This is interesting given that student self-efficacy has been identified to influence ‘motivation, persistence, and determination’ in overcoming challenges in a career pathway 24 . Taken together, this suggests that creation and delivery of modern, exciting curriculum that supports positive student attitudes is fundamental to engage and retain students in STEM programs.

Supported by the outcomes of identified effective learning strategies, University of Toronto (U of T) graduate trainees created a novel high school education program Discovery , to develop a comfortable yet stimulating environment of inquiry-focused iterative learning for senior high school students (Grades 11 & 12; Levels 3 & 4) at non-specialized schools. Built in strong collaboration with science teachers from George Harvey Collegiate Institute (Toronto District School Board), Discovery stimulates application of STEM concepts within a unique term-long applied curriculum delivered iteratively within both U of T undergraduate teaching facilities and collaborating high school classrooms 25 . Based on the volume of medically-themed news and entertainment that is communicated to the population at large, the rapidly-growing and diverse field of biomedical engineering (BME) were considered an ideal program context 26 . In its definition, BME necessitates cross-disciplinary STEM knowledge focused on the betterment of human health, wherein Discovery facilitates broadening student perspective through engaging inquiry-based projects. Importantly, Discovery allows all students within a class cohort to work together with their classroom teacher, stimulating continued development of a relevant learning community that is deemed essential for meaningful context and important for transforming student perspectives and understandings 27 , 28 . Multiple studies support the concept that relevant learning communities improve student attitudes towards learning, significantly increasing student motivation in STEM courses, and consequently improving the overall learning experience 29 . Learning communities, such as that provided by Discovery , also promote the formation of self-supporting groups, greater active involvement in class, and higher persistence rates for participating students 30 .

The objective of Discovery , through structure and dissemination, is to engage senior high school science students in challenging, inquiry-based practical BME activities as a mechanism to stimulate comprehension of STEM curriculum application to real-world concepts. Consequent focus is placed on critical thinking skill development through an atmosphere of perseverance in ambiguity, something not common in a secondary school knowledge-focused delivery but highly relevant in post-secondary STEM education strategies. Herein, we describe the observed impact of the differential project-based learning environment of Discovery on student performance and engagement. We identify the value of an inquiry-focused learning model that is tangible for students who struggle in a knowledge-focused delivery structure, where engagement in conceptual critical thinking in the relevant subject area stimulates student interest, attitudes, and resulting academic performance. Assessment of study outcomes suggests that when provided with a differential learning opportunity, student performance and interest in STEM increased. Consequently, Discovery provides an effective teaching and learning framework within a non-specialized school that motivates students, provides opportunity for critical thinking and problem-solving practice, and better prepares them for persistence in future STEM programs.

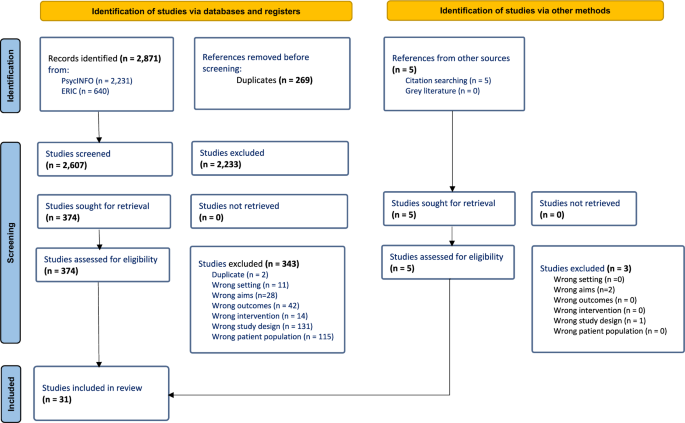

Program delivery

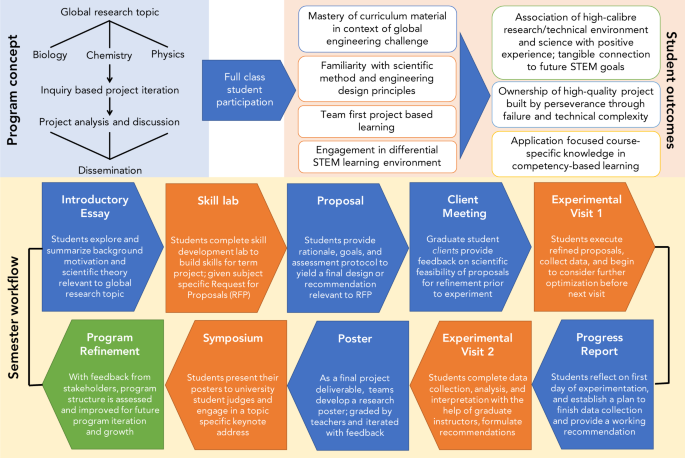

The outcomes of the current study result from execution of Discovery over five independent academic terms as a collaboration between Institute of Biomedical Engineering (graduate students, faculty, and support staff) and George Harvey Collegiate Institute (science teachers and administration) stakeholders. Each term, the program allowed senior secondary STEM students (Grades 11 and 12) opportunity to engage in a novel project-based learning environment. The program structure uses the problem-based engineering capstone framework as a tool of inquiry-focused learning objectives, motivated by a central BME global research topic, with research questions that are inter-related but specific to the curriculum of each STEM course subject (Fig. 1 ). Over each 12-week term, students worked in teams (3–4 students) within their class cohorts to execute projects with the guidance of U of T trainees ( Discovery instructors) and their own high school teacher(s). Student experimental work was conducted in U of T teaching facilities relevant to the research study of interest (i.e., Biology and Chemistry-based projects executed within Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories; Physics projects executed within Undergraduate Design Studios). Students were introduced to relevant techniques and safety procedures in advance of iterative experimentation. Importantly, this experience served as a course term project for students, who were assessed at several points throughout the program for performance in an inquiry-focused environment as well as within the regular classroom (Fig. 1 ). To instill the atmosphere of STEM, student teams delivered their outcomes in research poster format at a final symposium, sharing their results and recommendations with other post-secondary students, faculty, and community in an open environment.

The general program concept (blue background; top left ) highlights a global research topic examined through student dissemination of subject-specific research questions, yielding multifaceted student outcomes (orange background; top right ). Each program term (term workflow, yellow background; bottom panel ), students work on program deliverables in class (blue), iterate experimental outcomes within university facilities (orange), and are assessed accordingly at numerous deliverables in an inquiry-focused learning model.

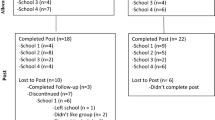

Over the course of five terms there were 268 instances of tracked student participation, representing 170 individual students. Specifically, 94 students participated during only one term of programming, 57 students participated in two terms, 16 students participated in three terms, and 3 students participated in four terms. Multiple instances of participation represent students that enrol in more than one STEM class during their senior years of high school, or who participated in Grade 11 and subsequently Grade 12. Students were surveyed before and after each term to assess program effects on STEM interest and engagement. All grade-based assessments were performed by high school teachers for their respective STEM class cohorts using consistent grading rubrics and assignment structure. Here, we discuss the outcomes of student involvement in this experiential curriculum model.

Student performance and engagement

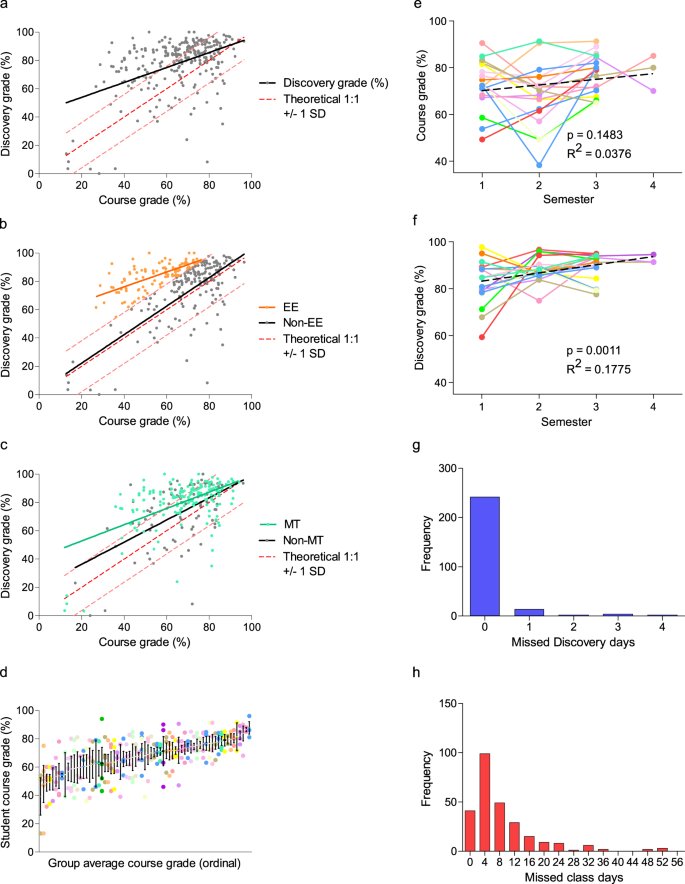

Student grades were assigned, collected, and anonymized by teachers for each Discovery deliverable (background essay, client meeting, proposal, progress report, poster, and final presentation). Teachers anonymized collective Discovery grades, the component deliverable grades thereof, final course grades, attendance in class and during programming, as well as incomplete classroom assignments, for comparative study purposes. Students performed significantly higher in their cumulative Discovery grade than in their cumulative classroom grade (final course grade less the Discovery contribution; p < 0.0001). Nevertheless, there was a highly significant correlation ( p < 0.0001) observed between the grade representing combined Discovery deliverables and the final course grade (Fig. 2a ). Further examination of the full dataset revealed two student cohorts of interest: the “Exceeds Expectations” (EE) subset (defined as those students who achieved ≥1 SD [18.0%] grade differential in Discovery over their final course grade; N = 99 instances), and the “Multiple Term” (MT) subset (defined as those students who participated in Discovery more than once; 76 individual students that collectively accounted for 174 single terms of assessment out of the 268 total student-terms delivered) (Fig. 2b, c ). These subsets were not unrelated; 46 individual students who had multiple experiences (60.5% of total MTs) exhibited at least one occasion in achieving a ≥18.0% grade differential. As students participated in group work, there was concern that lower-performing students might negatively influence the Discovery grade of higher-performing students (or vice versa). However, students were observed to self-organize into groups where all individuals received similar final overall course grades (Fig. 2d ), thereby alleviating these concerns.

a Linear regression of student grades reveals a significant correlation ( p = 0.0009) between Discovery performance and final course grade less the Discovery contribution to grade, as assessed by teachers. The dashed red line and intervals represent the theoretical 1:1 correlation between Discovery and course grades and standard deviation of the Discovery -course grade differential, respectively. b , c Identification of subgroups of interest, Exceeds Expectations (EE; N = 99, orange ) who were ≥+1 SD in Discovery -course grade differential and Multi-Term (MT; N = 174, teal ), of which N = 65 students were present in both subgroups. d Students tended to self-assemble in working groups according to their final course performance; data presented as mean ± SEM. e For MT students participating at least 3 terms in Discovery , there was no significant correlation between course grade and time, while ( f ) there was a significant correlation between Discovery grade and cumulative terms in the program. Histograms of total absences per student in ( g ) Discovery and ( h ) class (binned by 4 days to be equivalent in time to a single Discovery absence).

The benefits experienced by MT students seemed progressive; MT students that participated in 3 or 4 terms ( N = 16 and 3, respectively ) showed no significant increase by linear regression in their course grade over time ( p = 0.15, Fig. 2e ), but did show a significant increase in their Discovery grades ( p = 0.0011, Fig. 2f ). Finally, students demonstrated excellent Discovery attendance; at least 91% of participants attended all Discovery sessions in a given term (Fig. 2g ). In contrast, class attendance rates reveal a much wider distribution where 60.8% (163 out of 268 students) missed more than 4 classes (equivalent in learning time to one Discovery session) and 14.6% (39 out of 268 students) missed 16 or more classes (equivalent in learning time to an entire program of Discovery ) in a term (Fig. 2h ).

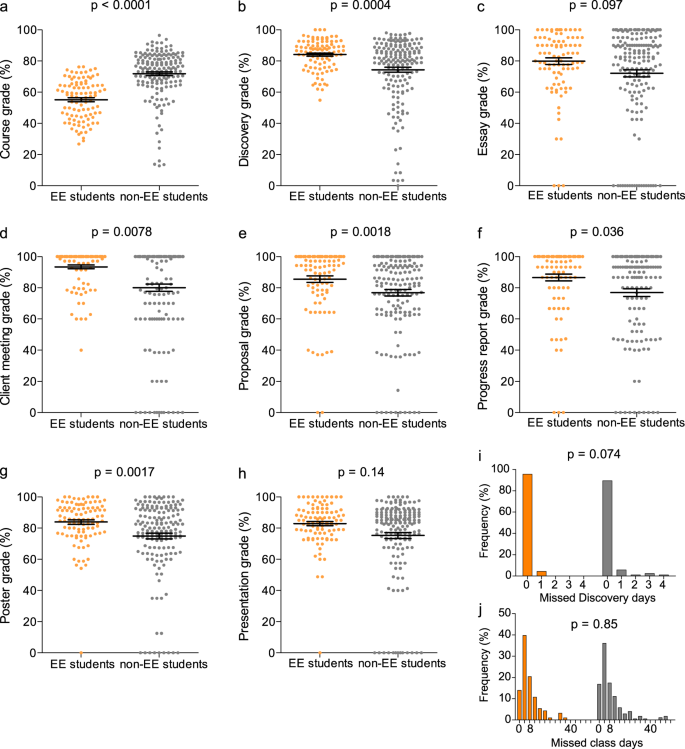

Discovery EE students (Fig. 3 ), roughly by definition, obtained lower course grades ( p < 0.0001, Fig. 3a ) and higher final Discovery grades ( p = 0.0004, Fig. 3b ) than non-EE students. This cohort of students exhibited program grades higher than classmates (Fig. 3c–h ); these differences were significant in every category with the exception of essays, where they outperformed to a significantly lesser degree ( p = 0.097; Fig. 3c ). There was no statistically significant difference in EE vs. non-EE student classroom attendance ( p = 0.85; Fig. 3i, j ). There were only four single day absences in Discovery within the EE subset; however, this difference was not statistically significant ( p = 0.074).

The “Exceeds Expectations” (EE) subset of students (defined as those who received a combined Discovery grade ≥1 SD (18.0%) higher than their final course grade) performed ( a ) lower on their final course grade and ( b ) higher in the Discovery program as a whole when compared to their classmates. d – h EE students received significantly higher grades on each Discovery deliverable than their classmates, except for their ( c ) introductory essays and ( h ) final presentations. The EE subset also tended ( i ) to have a higher relative rate of attendance during Discovery sessions but no difference in ( j ) classroom attendance. N = 99 EE students and 169 non-EE students (268 total). Grade data expressed as mean ± SEM.

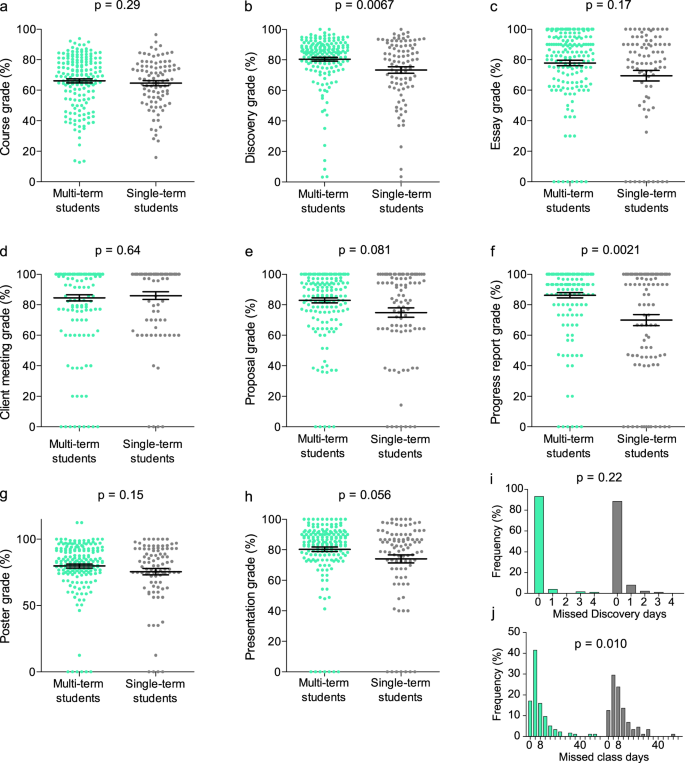

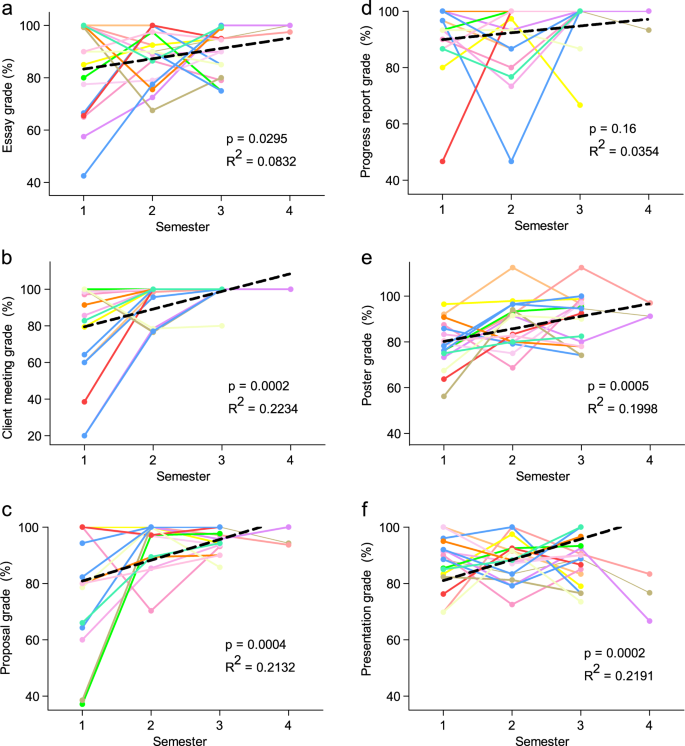

Discovery MT students (Fig. 4 ), although not receiving significantly higher grades in class than students participating in the program only one time ( p = 0.29, Fig. 4a ), were observed to obtain higher final Discovery grades than single-term students ( p = 0.0067, Fig. 4b ). Although trends were less pronounced for individual MT student deliverables (Fig. 4c–h ), this student group performed significantly better on the progress report ( p = 0.0021; Fig. 4f ). Trends of higher performance were observed for initial proposals and final presentations ( p = 0.081 and 0.056, respectively; Fig. 4e, h ); all other deliverables were not significantly different between MT and non-MT students (Fig. 4c, d, g ). Attendance in Discovery ( p = 0.22) was also not significantly different between MT and non-MT students, although MT students did miss significantly less class time ( p = 0.010) (Fig. 4i, j ). Longitudinal assessment of individual deliverables for MT students that participated in three or more Discovery terms (Fig. 5 ) further highlights trend in improvement (Fig. 2f ). Greater performance over terms of participation was observed for essay ( p = 0.0295, Fig. 5a ), client meeting ( p = 0.0003, Fig. 5b ), proposal ( p = 0.0004, Fig. 5c ), progress report ( p = 0.16, Fig. 5d ), poster ( p = 0.0005, Fig. 5e ), and presentation ( p = 0.0295, Fig. 5f ) deliverable grades; these trends were all significant with the exception of the progress report ( p = 0.16, Fig. 5d ) owing to strong performance in this deliverable in all terms.

The “multi-term” (MT) subset of students (defined as having attended more than one term of Discovery ) demonstrated favorable performance in Discovery , ( a ) showing no difference in course grade compared to single-term students, but ( b outperforming them in final Discovery grade. Independent of the number of times participating in Discovery , MT students did not score significantly differently on their ( c ) essay, ( d ) client meeting, or ( g ) poster. They tended to outperform their single-term classmates on the ( e ) proposal and ( h ) final presentation and scored significantly higher on their ( f ) progress report. MT students showed no statistical difference in ( i ) Discovery attendance but did show ( j ) higher rates of classroom attendance than single-term students. N = 174 MT instances of student participation (76 individual students) and 94 single-term students. Grade data expressed as mean ± SEM.

Longitudinal assessment of a subset of MT student participants that participated in three ( N = 16) or four ( N = 3) terms presents a significant trend of improvement in their ( a ) essay, ( b ) client meeting, ( c ) proposal, ( e ) poster, and ( f ) presentation grade. d Progress report grades present a trend in improvement but demonstrate strong performance in all terms, limiting potential for student improvement. Grade data are presented as individual student performance; each student is represented by one color; data is fitted with a linear trendline (black).

Finally, the expansion of Discovery to a second school of lower LOI (i.e., nominally higher aggregate SES) allowed for the assessment of program impact in a new population over 2 terms of programming. A significant ( p = 0.040) divergence in Discovery vs. course grade distribution from the theoretical 1:1 relationship was found in the new cohort (S 1 Appendix , Fig. S 1 ), in keeping with the pattern established in this study.

Teacher perceptions

Qualitative observation in the classroom by high school teachers emphasized the value students independently placed on program participation and deliverables. Throughout the term, students often prioritized Discovery group assignments over other tasks for their STEM courses, regardless of academic weight and/or due date. Comparing within this student population, teachers spoke of difficulties with late and incomplete assignments in the regular curriculum but found very few such instances with respect to Discovery -associated deliverables. Further, teachers speculated on the good behavior and focus of students in Discovery programming in contrast to attentiveness and behavior issues in their school classrooms. Multiple anecdotal examples were shared of renewed perception of student potential; students that exhibited poor academic performance in the classroom often engaged with high performance in this inquiry-focused atmosphere. Students appeared to take a sense of ownership, excitement, and pride in the setting of group projects oriented around scientific inquiry, discovery, and dissemination.

Student perceptions

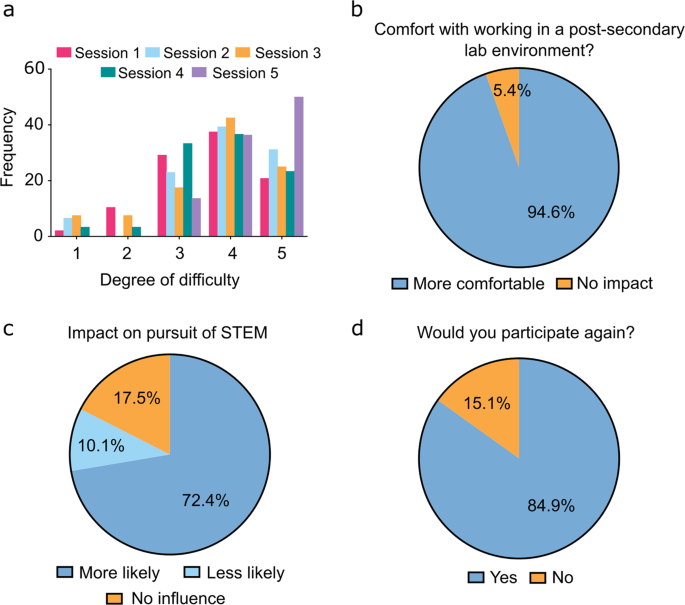

Students were asked to consider and rank the academic difficulty (scale of 1–5, with 1 = not challenging and 5 = highly challenging) of the work they conducted within the Discovery learning model. Considering individual Discovery terms, at least 91% of students felt the curriculum to be sufficiently challenging with a 3/5 or higher ranking (Term 1: 87.5%, Term 2: 93.4%, Term 3: 85%, Term 4: 93.3%, Term 5: 100%), and a minimum of 58% of students indicating a 4/5 or higher ranking (Term 1: 58.3%, Term 2: 70.5%, Term 3: 67.5%, Term 4: 69.1%, Term 5: 86.4%) (Fig. 6a ).

a Histogram of relative frequency of perceived Discovery programming academic difficulty ranked from not challenging (1) to highly challenging (5) for each session demonstrated the consistently perceived high degree of difficulty for Discovery programming (total responses: 223). b Program participation increased student comfort (94.6%) with navigating lab work in a university or college setting (total responses: 220). c Considering participation in Discovery programming, students indicated their increased (72.4%) or decreased (10.1%) likelihood to pursue future experiences in STEM as a measure of program impact (total responses: 217). d Large majority of participating students (84.9%) indicated their interest for future participation in Discovery (total responses: 212). Students were given the opportunity to opt out of individual survey questions, partially completed surveys were included in totals.

The majority of students (94.6%) indicated they felt more comfortable with the idea of performing future work in a university STEM laboratory environment given exposure to university teaching facilities throughout the program (Fig. 6b ). Students were also queried whether they were (i) more likely, (ii) less likely, or (iii) not impacted by their experience in the pursuit of STEM in the future. The majority of participants (>82%) perceived impact on STEM interests, with 72.4% indicating they were more likely to pursue these interests in the future (Fig. 6c ). When surveyed at the end of term, 84.9% of students indicated they would participate in the program again (Fig. 6d ).

We have described an inquiry-based framework for implementing experiential STEM education in a BME setting. Using this model, we engaged 268 instances of student participation (170 individual students who participated 1–4 times) over five terms in project-based learning wherein students worked in peer-based teams under the mentorship of U of T trainees to design and execute the scientific method in answering a relevant research question. Collaboration between high school teachers and Discovery instructors allowed for high school student exposure to cutting-edge BME research topics, participation in facilitated inquiry, and acquisition of knowledge through scientific discovery. All assessments were conducted by high school teachers and constituted a fraction (10–15%) of the overall course grade, instilling academic value for participating students. As such, students exhibited excitement to learn as well as commitment to their studies in the program.