Advertisement

Empirical studies of factors associated with child malnutrition: highlighting the evidence about climate and conflict shocks

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 21 May 2020

- Volume 12 , pages 1241–1252, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Molly E. Brown ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7384-3314 1 ,

- David Backer 2 ,

- Trey Billing 2 ,

- Peter White 3 ,

- Kathryn Grace 4 ,

- Shannon Doocy 5 &

- Paul Huth 2

15k Accesses

26 Citations

37 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Children who experience poor nutrition during the first 1000 days of life are more vulnerable to illness and death in the near term, as well as to lower work capacity and productivity as adults. These problems motivate research to identify basic and underlying factors that influence risks of child malnutrition. Based on a structured search of existing literature, we identified 90 studies that used statistical analyses to assess relationships between potential factors and major indicators of child malnutrition: stunting, wasting, and underweight. Our review determined that wasting, a measure of acute malnutrition, is substantially understudied compared to the other indicators. We summarize the evidence about relationships between child malnutrition and numerous factors at the individual, household, region/community, and country levels. Our results identify only select relationships that are statistically significant, with consistent signs, across multiple studies. Among the consistent predictors of child malnutrition are shocks due to variations in climate conditions (as measured with indicators of temperature, rainfall, and vegetation) and violent conflict. Limited research has been conducted on the relationship between violent conflict and wasting. Improved understanding of the variables associated with child malnutrition will aid advances in predictive modeling of the risks and severity of malnutrition crises and enhance the effectiveness of responses by the development and humanitarian communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Conflict and Climate Factors and the Risk of Child Acute Malnutrition Among Children Aged 24–59 Months: A Comparative Analysis of Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda

Kathryn Grace, Andrew Verdin, … Trey Billing

Conflict and Child Malnutrition: a Systematic Review of the Emerging Quantitative Literature

Maria Sassi & Harshita Thakare

Armed conflict as a determinant of children malnourishment: a cross-sectional study in The Sudan

Rihab Dahab, Laia Bécares & Mark Brown

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Malnutrition is preventable, yet remains a major public health challenge. This condition affects one in five children and contributes to nearly half of all deaths during childhood globally (Black et al. 2013 ). Children who have poor nutrition during their first 1000 days of life attain lower levels of education and have lower work capacity and productivity as adults. Malnourished children also face increased likelihoods of being overweight, of developing chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer, and of suffering from mental health issues later in life (Haddad et al. 1994 ; Hoddinott et al. 2013 ). After having suffered of malnutrition during early childhood, girls face increased likelihoods of having children that are born too early or underweight (UNSCN 2010 ).

Given the serious repercussions for survival, health, and well-being, anticipating and addressing the circumstances under which children become malnourished is vital. Various development and humanitarian interventions focus on fostering healthy communities where children are better protected and able to recover from nutrient deficits (Collins et al. 2006 ). To facilitate those interventions, assessments of food security conducted by organizations such as the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) and the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) initiative have sought to project the future status of at-risk countries and issue alerts about impending and ongoing crises months in advance, aiming to ensure enough lead time for the coordination and implementation of appropriate responses (Brown et al. 2007 ; Funk et al. 2019 ; IPC 2012 ). Assessments that focus on early warning have advantages relative to relying on measuring the prevalence of malnutrition in a community, which can detect a crisis only after it emerges (Maxwell et al. 2020 ). Assessments such as FEWS NET and IPC, however, do not gauge, much less substantiate, associations between malnutrition at an individual level and relevant factors. Statistically modelling these empirical relationships is integral to detecting vulnerabilities, diagnosing their sources, and directing assistance.

In this article, we consolidate what has been learned from published studies that used statistical analysis of empirical data to examine relationships between malnutrition among children and a large array of individual-, household-, community-, regional- and national-level variables. Our literature review is guided by two main questions: (1) Which variables were consistently associated with child malnutrition? (2) What types of quantitative empirical data and statistical methods have been used to analyse the nature of the relationship between these variables and child malnutrition? Answering these questions results in a summary of drivers of malnutrition, clarifies the strengths and limitations of existing studies, and suggests potential directions for further research, which may include a formal meta-analysis.

Our review considers studies in which the outcomes of interest included at least one of three major indicators of malnutrition, formalized in international standards (WHO 2020 ). Wasting (low weight for height) indicates an acute decline in nutritional status experienced by a normally well-nourished child. This decline usually involves rapid and substantial weight loss. Stunting (low height for age), by contrast, indicates a chronic, long-term nutritional deficit, the effects of which are potentially irreversible (Kennedy et al. 2015 ). Children who suffer wasting regularly over time may also develop stunting (Hoddinott et al. 2008 ). Underweight (low weight for age), on the other hand, can reflect wasting, stunting, or both (WHO 2010 ).

The breadth of our review provides a more expansive picture of the findings from the empirical research about malnutrition, according to statistical modelling of quantitative data. In the process, we can compare the state of knowledge about factors associated with the different indicators of malnutrition. Our expectation is that the findings of the review will improve awareness of which factors yield consistent findings and emphasize how particular relationships can vary across different measures of malnutrition.

At the same time, we have a specific interest in the variables associated with wasting. The acute nature of this condition presents a distinct challenge in practice. Prompt, effective interventions, with the potential to mitigate the risk of wasting, depend on the existence of reliable guidance about factors that tend to be associated with changes in individuals’ nutritional status in the short term. Insights from such a review may help inform interventions that are focused on reversing weight loss trajectories in children before malnutrition becomes a persistent condition.

Finally, we spotlight the role of external shocks experienced by individuals, households and communities, especially those caused by exposures to environmental and societal forces. Disasters due to climate extremes (e.g., drought) and violent conflict (e.g., civil war) are regularly attributed as the primary causes – acting independently and in interaction – of crises such as famines resulting in prevalence spikes in the rate of acute malnutrition. The urgency of understanding the role of these shocks has been magnified as complex emergencies are becoming more common and lasting longer (Lautze and Raven-Roberts 2006 ; Young et al. 2004 ). Policies resulting in timely action are needed to reduce the impact of these crises on children, families, and the communities in which they live (Ghobarah et al. 2003 ; Hillbruner and Moloney 2012 ).

We start by presenting the methods we used to isolate and code relevant studies that were included in our review. Next, we summarize the results of our review. In the concluding section, we discuss the results in the context of the broader literature, with particular attention to studies about the relationship between malnutrition and climate extremes, conflict events, and their interactions.

We conducted a search of the American Economic Association’s EconLit database in January 2019. EconLit indexes six types of materials: journal articles, books, book chapters, dissertations, working papers, and book reviews. The coverage features nearly 1 million articles from over 1000 journals published in 74 countries, dating from 1969 to the present ( https://www.aeaweb.org/econlit/content ). Many of the topics covered by the material indexed in EconLit relate to child malnutrition, including Health and Economic Development (JEL code I15), Health and Inequality (JEL code I14), Health, Government Policy, and Regulation (JEL code I16), Welfare, Wellbeing and Poverty (JEL code I3), Fertility, Family Planning, Child Care, Children, and Youth (JEL code J13), Agricultural Economics (JEL code Q1), and Renewable Resources and Conservation (JEL code Q2) (see http://www.aeaweb.org/econlit/jelCodes.php for a complete list of topics covered by EconLit). We sought to identify articles indexed by EconLit that quantitatively assess potential factors, with explicit statistical tests, in relation to child malnutrition. We therefore conducted separate searches using “malnutrition,” “wasting,” “wasted,” “stunting,” “stunted,” “underweight,” and “undernourishment” as key words. In addition, we paired each of these key words with “child” when conducting searches. In total, the searches yielded a set of 688 articles.

Within this set, we then selected articles relevant to our review. We therefore searched for any mentions of “child wast*” (166 articles), “child stunt*” (104 articles), and “child under*” (39 articles) in the article titles and abstracts. Certain articles referenced multiple search terms. We thus selected 209 potentially relevant articles. Finally, we scanned the titles and abstracts of these remaining articles with the following criteria:

use of quantitative and/or numerically coded qualitative data within a statistical analysis.

dependent variable(s) in the analysis must be some variant(s) of child malnutrition.

testing of statistical relationship between child malnutrition and one or more independent variables.

Some of the reasons for excluding articles include:

article not published in an English-language academic journal (for reasons of feasibility in conducting the review).

title and/or abstract indicating that the study is unrelated to our review (e.g., food waste).

title and/or abstract indicating that the study is peripheral to our objective (e.g., global narratives regarding child health).

title and/or abstract not mentioning quantitative data analysis.

quantitative analysis referred to in abstract concerning adult malnutrition Articles evaluating adult nutrition (e.g., of the mother during pregnancy) as a factor for child malnutrition were retained.

quantitative analysis referred to in title and/or abstract concerning not concerning relationships between child nutrition prevalence and any of its factors.

quantitative analysis referred to in the title and/or abstract considering child malnutrition as an independent, and not a dependent variable.

Our approach using the inclusion and exclusion criteria yielded a sample of 61 articles from EconLit.

We further augmented the sample with 29 articles from beyond the EconLit database. These additional articles: (1) cited articles from the EconLit sample, (2) were cited by those articles, and/or (3) involved authors of those articles. All the additional articles satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria stated above. The final sample therefore consists of a total of 90 articles (see supplementary Table S 1 for details).

2.1 Coding of article variables

Information pertaining to each article was coded according to the following: the data used (location, timing, panel vs. cross-section, sample size); statistical methods of analysis; and the dependent and independent variables considered. Only the main statistical results in a given article were coded; other results (e.g., exploratory subgroup tests, robustness checks, and sensitivity analyses) were not included. Dependent variables were grouped into three categories: wasting (W, continuous weight-for-height z-score and/or binary indicator for wasted), stunting (S, continuous height-for-age z-score and/or binary indicator for stunted), and underweight (U, continuous weight-for-age z-score and/or binary indicator for underweight) (de Onis and Blössner 2003 ). Each combination of a dependent variable and an independent variable in a given article was coded with both the sign and the level of reported statistical significance of the relationship as evaluated in the analysis. Most of the reviewed studies focus on the sign of relationships; few studies pay close attention to the magnitude of effect sizes. P -values were not always reported in all articles, reflecting differences in standards across journals and fields. The coding categorized each relationship as significant if the p value was smaller than or equal to 0.05. These instances were marked as 1. All other instances were marked as 0. The coding also noted instances of p -values less than (or equal to) 0.01 and 0.001 (supplementary materials; (Finlay and Agresti 1986 )). Supplementary Table S 2 provides a list of all variables reported in all 90 reviewed articles, along with their reported statistical significance.

Across the sample of reviewed studies, more than 300 independent variables were found. Independent variables about the same factor, even if operationalized differently, were consolidated into a factor category to facilitate comparison across studies (Phalkey et al. 2015 ). Supplementary Table S 3 lists all variables analysed in the reviewed studies that comprise our factor categories, and which papers they came from.

The findings of the studies included in our review enabled each factor to be characterized as follows:

Risk factor – a majority of reviewed studies examining a given type of malnutrition report a significant ( p ≤ 0.05) positive relationship with the independent variables (i.e., a greater extent or probability of malnutrition as a function of increasing values of the independent variable).

Mitigating factor – a majority of reviewed studies examining a given type of malnutrition report a significant (p ≤ 0.05) negative relationship with the independent variables (i.e., a lower extent or probability of malnutrition as a function of increasing values of the independent variable).

Inconclusive factor – a majority of studies examining a given type of malnutrition report either an inconsistent sign of the relationship with the independent factor, or a relationship that is not statistically significant ( p > 0.05).

In order to facilitate comparison and the policy and other practical applications of the analysis, factors were grouped according to the scale they concern: child, household, region/community, or country (Smith et al. 2005 ).

Relationships between a given type of malnutrition and a given factor may have been evaluated in only one study. While all relationships appearing in the main statistical analysis of each study were coded and documented (Table S2 ), only factors evaluated in multiple studies were reported in the results. All studies were treated equally, regardless of scope, scale of the analysis, magnitude of effect sizes, and level of significance reported. The results of the analysis offer a general summary and mapping of results to capture patterns in the existing research. No statistical assessment of the importance of factors across publications (“effect size” in the meta-analysis literature) is provided in the interest of reflecting the broadest possible sample of studies.

Wasting and underweight have been studied less often than stunting (Table 1 ). Just over 34% of the reviewed studies modelled wasting. Slightly more studies operationalized this outcome with a binary variable (whether or not children were wasted, as a status based on exceeding a given threshold) than with a z-score (extent of deviation from international standards, along a continuous scale that captures a spectrum of outcomes in a process of becoming undernourished). Under 5% of the reviewed articles used both operationalizations of wasting in their analysis. Similarly, underweight appeared in 34% of the reviewed studies. In these studies, the operationalization was most often a z-score, rather than a binary variable. Meanwhile, 81% of the articles used stunting as a dependent variable; a z-score was most common for stunting as well.

3.1 Factors evaluated as affecting child nutrition

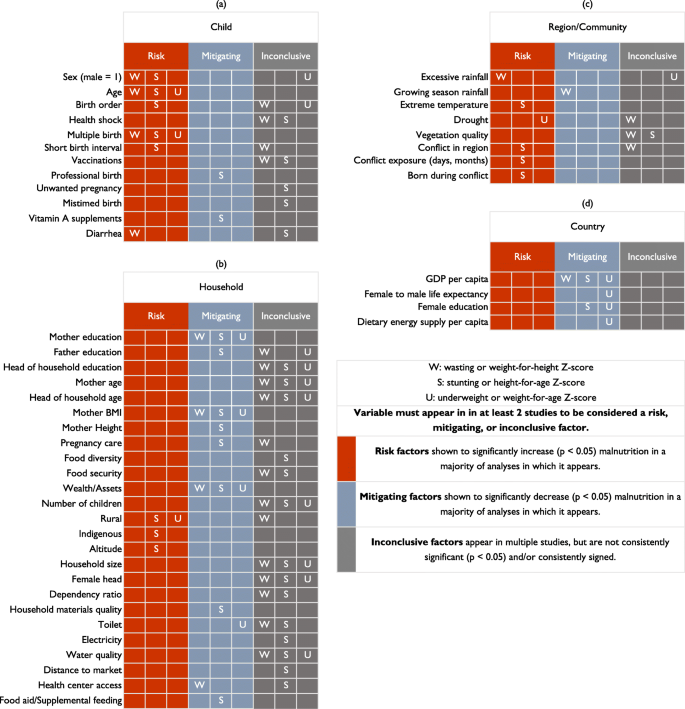

A total of 49 factors were evaluated in relation to wasting, stunting, and/or underweight by multiple studies (Fig. 1 ). This list includes 12 factors measured at the individual level; 25 factors measured at the household level (including five factors pertaining to mothers); eight factors measured at the region/community level; and four factors measured at the country level (Table S3 ). Analysis of disaggregated data at the individual and/or household level featured in 89% of the reviewed articles. Most analyses did not include any covariates measured at the regional/community or country levels (e.g., (Ekbrand and Halleröd 2018 )). Thus, fewer articles are available with which to evaluate the consistency of relationships of factors at the regional/community and country levels than at the individual and household levels. Of the 49 factors, 18 have been evaluated by multiple studies in relation to each of the three standard measures of child malnutrition (Fig. 1 ). The subsequent presentation of results is restricted to instances of prevailing evidence of statistically significant relationships indicating risk factors or mitigating factors, according to a majority of relevant reviewed studies.

Summary of results from statistical analyses of relationships between indicators of child malnutrition and: a child-specific factors, b household-level factors, c region/community-level factors, and d country-level factors. Note: We limit the results reflected in this figure to factors that are evaluated in the main statistical analyses reported in at least two of the 90 reviewed articles. Details of which study was included in each factor can be found in Supplementary Table S 3

Eight of the 12 factors measured at the level of individual children exhibited statistically significant relationships for the following factors: child’s sex and age, if they were a multiple at birth (twin, triplet, etc.), and diarrhea status (Fig. 1a ). Seven of the 10 factors evaluated in relation to stunting exhibited statistically significant associations. These associations identified five risk factors: child’s sex and age, their birth order, if they were a multiple at birth, and short birth interval. Two mitigating factors were also identified: if a professionally trained assistant was present at the birth and if Vitamin A supplements had been used. The results indicated that two of the four factors evaluated in relation to underweight were statistically significant risk factors: child’s age and if they were a multiple at birth. According to our review, therefore, all three anthropometric measures of malnutrition were associated with two individual-level risk factors: age and multiple at birth.

Of the 25 household-level factors, just four of the 17 factors exhibited statistically significant associations: mother’s education, mother’s BMI, wealth/assets, and access to a health care center (Fig. 1b ). All were evaluated as being mitigating factors. Eleven of the 25 factors evaluated in relation to stunting yielded statistically significant associations. The relationships identified three risk factors: rural, indigenous, and altitude. In addition, eight mitigating factors were identified: mother’s education, father’s education, mother’s BMI, mother’s height, pregnancy care, wealth/assets, quality of household materials, and food aid or supplemental feeding. Five of the 13 factors evaluated in relation to underweight yielded statistically significant associations. Only one relationship identified a risk factor: rural residence. Four mitigating factors were also identified: mother’s education, mother’s BMI, wealth/assets, and quality of toilet. According to our review, therefore, all three anthropometric measures were associated with three household-level risk factors: mother’s education (either years of education or specific levels relative to no education), mother’s BMI, and wealth/assets (encompassing different indices).

The eight factors measured at the region/community level is split between measuring features of the environment, including climate conditions, and features related to conflict (Fig. 1c ). Wasting had a statistically significant association with excessive rainfall as a risk factor and growing season rainfall as a mitigating factor. Stunting had a statistically significant association with extreme temperatures as a risk factor. Underweight only exhibited a statistically significant association with drought as a risk factor. Several of the reviewed studies analysed vegetation quality, employing either the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) or the enhanced vegetation index (EVI), with varying operationalizations. In particular, vegetation quality during the previous growing season has been evaluated in multiple studies of both wasting and stunting, yielding findings that vary by context. Statistically significant associations were observed between stunting and three factors that reflect distinctive operationalizations of the role of conflict. Conflict in the surrounding region, conflict exposure (days or months), and whether a child was born during a conflict were all identified as risk factors for stunting.

At the country level, national per capita GDP was identified as a mitigating factor for wasting, stunting, and underweight (Fig. 1d ). Female education (encompassing national rates of female literacy and female secondary enrolment) was identified as a mitigating factor for stunting and underweight. Both the national average female-to-male life expectancy ratio and the dietary energy supply per capita were identified as mitigating factors for underweight.

3.2 Statistical methods

About 60% of the reviewed studies employed standard variations of multivariate regression techniques, such as linear, generalized linear (e.g., logit), or multilevel models. Only 5% of studies used explicit multilevel statistical techniques, modelling simultaneously the relationships between malnutrition and covariates at the individual, household, and regional/community levels (e.g., (Ekbrand and Halleröd 2018 )). Other studies that did not estimate multilevel models instead included covariates aggregated to higher levels, introduced dummy variables for geographic regions, or adjusted for within-spatial-unit correlation via clustered standard errors (e.g., (Rashad and Sharaf 2018 )). Five articles used quantile regression, which fits a model through quantiles of the dependent variable, rather than the mean (e.g., (Asfaw 2018 )). This approach has the advantage of allowing for heterogeneous treatment effects for different segments of the distribution of child malnutrition. For example, a given factor may exhibit a stronger association with weight-for-height z-scores for children who are undernourished (i.e., the left tail of the distribution), relative the association observed for children whose nutrition status is near the center of the distribution.

A majority of reviewed studies relied on cross-sectional analysis of either data from single surveys or a pooled dataset comprising multiple cross-sectional surveys. Just five of the studies capitalized on panel data involving repeated waves of data collection for the same children or households over time. The remaining studies employed a diversity of approaches, including time-series analysis of repeated cross-sections of countries or subnational regions. Among the reviewed studies, the most common source of malnutrition measures was Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data (27 studies). Five of the reviewed studies used Living Standards and Measurements Survey (LSMS) data. The remaining studies employed other country-specific surveys, with India’s National Family Health Survey (4 studies) and Ethiopia’s Rural Household Survey (2 studies) featuring in multiple cases.

In terms of causal identification strategies, 17% of the reviewed studies directly leveraged the availability of data collected from repeated measurement over time, estimating either unit-level fixed effects or difference-in-differences models (e.g., (Lucas and Wilson 2013 )). A further 9% of articles featured an instrumental variables strategy (e.g., (Yamano et al. 2005 )) and another 6% of articles resorted to matching techniques (e.g., propensity score) to control for selection bias and minimize problems of sample imbalance. The remaining studies exhibited a variety of other approaches, including decomposition analysis (Block et al. 2004 ; Rodriguez 2016 ) and a regression discontinuity design (Ali and Elsayed 2018 ).

Among the reviewed studies, attention to the temporal relationship between malnutrition and potential factors was limited and uneven, constraining the ability to ascertain any general patterns. The lack of such examination of the impact of climate and conflict shocks is especially conspicuous. A common approach has been to measure deviations in conditions during the survey period relative to long-run average conditions, within a suitable sub-national geographic area surrounding the survey cluster. The implicit assumption is that the deviations in conditions exert a contemporaneous impact on malnutrition. Select studies used models specifying factors with time lags. For example, Johnson and Brown (Johnson and Brown 2014 ) tested one- and two-year lagged measures of shocks in vegetation, but the results of these estimations were not presented because the observed effects were not statistically significant. Kinyoki et al. ( 2016 ) tested lags measures of conflict during the three months prior to survey and the period from 3 to 12 months prior to the survey, finding that both variables have statistically significant associations with wasting and stunting. Howell et al. (Howell et al. 2018 ) tested yearly lagged values of conflict days and deaths in an analyses of stunting and wasting. Another approach in studies that have modelled the effects of conflict shocks on child malnutrition is cohort analysis. The effect of the shock is gauged based on birth timing relative to the shock, evaluating how the “during” shock cohort differs from the “before” shock and “after” shock cohorts (Grace et al. 2015 ).

3.3 Geographical coverage

Nearly 80% of the reviewed studies focused on a single country or even just one sub-national geographic area within a country. The country that features the most often was India, in 13% of the studies. Ethiopia was second (10%), followed by Guatemala and Kenya (6% each). Nineteen of the reviewed studies (21%) analysed data from multiple countries. The studies with the most extensive geographic scope covered 166 countries (Smith and Haddad 2015 ), 63 countries (Smith and Haddad 2001 ), and 41 countries (Kimenju and Qaim 2016 ). The analysis in each of these studies was conducted at the country level.

The shortage of comparative analysis within individual studies, the limited scope of geographic coverage among multiple studies that examined the same factors, and the lack of comparability of the studies that did examine the same factors in different country settings restricts understanding of the generalizability of observed relationships. Of interest, no comparative studies have been conducted to analyse the consistency of the relationship between child malnutrition and conflict across multiple country settings.

4 Discussion and conclusions

We conducted a review of 90 studies involving statistical analyses of empirical data to examine relationships of child malnutrition to factors measured at the individual, household, regional/community and national levels. Our main purpose was to consolidate understanding about the tendencies of findings to date and the design and extent of existing research. A main strength of our review was the wide scope, with respect to the number of studies included, the multiple measures of malnutrition reflected in the analyses reported in these studies, and the volume of factors evaluated in those analyses. The review by Phalkey et al. (Phalkey et al. 2015 ) takes a similar approach on fewer (15) studies and considered seven categories (agriculture, crops, weather, livelihood, demographics, morbidity, and diet). These categories were simply reported statistically significant, or not (Phalkey et al. 2015 ). The present review achieves a broader coverage of the literature, includes description of risk and mitigating factors, and highlights possible differences in relationships across the types of malnutrition. The approach used in the present review departs from a formal meta-analytical approach (Borenstein et al. 2011 ). Our approach allowed us to include a large number of studies, irrespective of statistical designs, choice of variables, and modelling approaches. Meta-analysis published elsewhere will be useful in confirming trends reported here.

Specifically, our review reveals that wasting is understudied as a measure of child malnutrition. Instead, far more attention has been paid to stunting. Another main observation is that many of the factors evaluated in relation to the different types of child malnutrition yielded inconclusive results or were not analysed in multiple studies. According to the prevailing evidence, select factors were associated with all three types of child malnutrition: age of child and multiple births are risk factors, while mother’s education, mother’s BMI, household wealth/assets, and national GDP per capita are mitigating factors. A single factor is associated with both wasting and stunting (child’s sex as a categorical variable) and two factors with both stunting and underweight (rural household, national female education level), while 23 factors are associated with only one of the types of malnutrition.

Previous research summarising determinants of child nutritional status identified factors similar to those in our review. For example, Smith et al. (Smith et al. 2005 ) list a number of individual- and household-level factors that seem important to nutritional status, including whether the child has had diarrhoea, mother’s education, mother’s nutritional status, feeding practices, sanitary conditions, wealth, and medical care. Many of these factors exhibit significant associations in the studies included in our review, which identifies other risk and mitigating factors as well.

The present review explicitly captures findings about the role of climate and conflict conditions, while other recent reviews about child malnutrition overlook these conditions (Jones et al. 2013 ; Leroy et al. 2015 ; (Wrottesley et al. 2015 )). Among the studies we reviewed, climate conditions are widely included in analyses, most often measured with indicators of precipitation, temperature, and vegetation. Measures of conflict conditions – activity in the surrounding region, extent of exposure, and birth during an affected period – are also included more selectively in analyses (Akresh et al. 2012 ; Delbiso et al. 2017 ). The prevailing evidence indicates that climate shocks involving excessive rainfall, extreme temperatures, and drought are among the risk factors for wasting, stunting, and underweight, respectively, while conflict emerged as a risk factor for stunting. Additional relationships between certain types of malnutrition and certain forms of external shocks may exist, but the evidence from our review is either inconclusive or only reflects single studies (Table S2 ).

Our results are consistent with existing research showing that climate-related shocks, such as droughts or floods, are detrimental to food security, especially of rural populations (Table S3 ) (Cooper et al. 2019 ; Douxchamps et al. 2016 ; Grace et al. 2014 ; Murali and Afifi 2014 ). Our review reveals that excessive rainfall is a risk factor and growing season rainfall is a mitigating factor. Excessive rainfall represents an extreme event, with the potential for natural disasters (e.g., floods) that can be damaging to health, well-being, and economic production. By comparison, growing season rainfall captures conditions during critical periods of agricultural productivity, when above-average precipitation logically tends to be beneficial to food security (Cooper et al. 2019 ; Funk et al. 2008 ). Another study found that households located in regions that experienced a drier-than-average year reported one more month of food insecurity than households experiencing wetter-than-average years (Niles and Brown 2017 ). Our review also found that stunting was associated with both extremely cold temperatures (Skoufias and Vinha 2012 ) and extremely hot temperatures (Jacoby et al. 2014 ) as risk factors. Other existing studies suggest that high temperatures and heat waves tend to be important for understanding food security (Phalkey et al. 2015 ; Bain et al. 2013 ; Grace et al. 2012 ). In addition, we found that the results for vegetation quality differ across countries. For example, Johnson and Brown (Johnson and Brown 2014 ) find vegetation quality during the previous growing season to be a statistically significant mitigating factor for wasting in Mali, but not Benin, Burkina Faso, or Guinea, while Shively et al. (Shively et al. 2015 ) did not find a statistically significant relationship between wasting and this factor in Nepal.

In comparison to the literature using climate variables, analyses of relationships between child malnutrition and conflict shocks are limited in number. Foundations for such studies exist in the literature about the effect of conflict on food security and public health. For example, Akresh et al. ( 2011 , (Akresh et al. 2012 )) and Bundervoet et al. ( 2009 ) showed that children in conflict-affected settings exhibit signs of stunting, with similar effects for children born before or during wartime. These results, however, have not translated into interventions that take advantage of data on climate and conflict, despite the increasing availability of sources with granular detail (Dunn 2018 ; Jones et al. 2010 ; Raleigh et al. 2010 ). Our review also highlights the lack of attention in existing research to the relationship between conflict and wasting. We view this gap as warranting attention given the acute nature of this type of malnutrition, which could plausibly be influenced by the sort of shock that conflict represents.

Another important consideration is that climate and conflict shocks can coincide – and influence one another. These potential intersections and interactions suggest possible causal pathways of child malnutrition. Multiple theories address the impact of climate shocks on the emergence of armed conflict, which cannot be decisively established (Hsiang and Burke 2014 ). Food security and nutrition may also be a key mediating factors in the nexus between climate and conflict. For example, Buhaug et al. (Buhaug et al. 2015 ) model a process in which climate shocks cause in a first stage to an increase of local food prices, which then lead to conflict during a second stage. They find evidence of a strong climate impact at the first stage, but a weak and inconsistent one at the second stage. Their argument is that the effect of food prices on conflict is likely conditional on local “socioeconomic and political contexts.” This explanation is consistent with findings of studies on the relationship between food prices and urban unrest (Berazneva and Lee 2013 ; Hendrix and Haggard 2015 ).

Our review indicates that empirical research evaluating the joint effects of environmental and political conditions on risks of malnutrition unfortunately remains the exception (Fig. 1 and Tables S 2 and S 3 ). Few studies on malnutrition have considered both climate and conflict simultaneously. A meta-analysis of nutrition surveys in Ethiopia from 2000 to 2017 concluded that droughts increase the prevalence of wasting, but the impact of conflict is less certain (Delbiso et al. 2017 ). Other research suggests that the effects of climate extremes and conflict should exacerbate one another, pushing conditions beyond a tipping point and contributing to complex emergencies. In the famines of the twentieth Century caused primarily by drought or flood, concurrent conflict often served to escalate the environmental crisis and exacerbate mortality (Devereux 2000 ). This finding is consistent with Sen’s (Sen 1981 ) seminal argument that no famines with exclusively natural causes have been observed in the modern era. Sen (Sen 1981 ) argues that contemporary societies should be able to respond more effectively to potential famines caused by droughts or other natural events, except when hampered by failures in social, economic, and political institutions. Crises arising with one type of shock may be eased by stored food or relief supplies, whereas the coincidence of both types of shocks undermines those responses. For example, conflict blocked aid from reaching populations at risk of malnutrition amid droughts in Ethiopia during the 1980s and in Somalia in 2011 (Hillbruner and Moloney 2012 ; Maxwell and Fitzpatrick 2012 ). More generally, conflict diminishes the capacity of households and communities to cope with other stresses and shocks (Raleigh et al. 2015 ).

Among the main challenges to achieving improvements in the detailed, rigorous analysis of relationships between child malnutrition and conflict is the availability of data. Surveys that serve as the source of data on nutrition are conducted in conflict-affected areas. The insecure nature of these conditions, however, can make data collection less frequent, extensive, and reliable, reducing their scope, scale, and quality. Also, the relevant surveys rarely collect information about direct conflict exposure at the individual or household level. Instead, studies that evaluate conflict as a factor usually resort to making inferences from analysis using event data. These data offer consistent precision of georeferencing of events only to the level of first- or at best second-order administrative divisions (Raleigh et al. 2010 ), rather than specific point locations or even small areas. Appropriately integrating these data on conflict into analysis requires a multilevel modelling approach (Gelman and Hill 2006 ), which can account for potential influences at the regional level, as well as other levels (individual, household, community). Such an approach can be complemented by reasonable theoretical arguments that children residing within regions experiencing conflict (and possibly affected neighbouring regions) are more vulnerable to suffering effects on malnutrition, through various causal pathways. Given that the direct exposure to conflict events is not measured, compounded by events being infrequent in most settings, the evaluated relationships are likely to be difficult to detect. Encountering such difficulties in the analysis of climate factors is less likely because of the greater geographic granularity of the available data, a more balanced distribution of conditions, and clearer, more direct pathways of influence of local conditions on individuals and households.

Ultimately, examining the state of knowledge about factors associated with acute and chronic child malnutrition holds the potential to help advance an ongoing agenda of scientific inquiry with practical applications that have important real-world consequences. Recent technological developments in mobile devices and remote sensing, communications coverage (including cell phone and Internet networks), and the ability to transmit large amounts of information rapidly improve the potential of designing and implementing more timely protective interventions (GSMA 2015 ). Considerable opportunities exist for identifying where, when, how, and why proven policy and public health interventions should be implemented (Collins et al. 2006 ), especially to gauge the local impact of climate and conflict shocks. Our review contributes to capabilities of isolating intervention points in ways that can improve strategies (Wrottesley et al. 2015 ; Walker et al. 2015 ). Further evidence from studies spanning multiple countries and time periods is needed to bolster the foundations for designing interventions (Dilley 2000 ). Pertinent data are increasingly available, including from sources (e.g., the World Food Program’s Food Aid Information System) that can be used to study the effectiveness of international aid and humanitarian assistance in relation to vulnerabilities to malnutrition.

Akresh, R., Lucchetti, L., & Thirumurthy, H. (2012). Wars and child health: Evidence from the Eritrean--Ethiopian conflict. Journal of Development Economics, 99 , 330–340.

Article Google Scholar

Akresh, R., Verwimp, P., & Bundervoet, T. (2011). Civil war, crop failure, and child stunting in Rwanda. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 59 , 777–810.

Ali, F. R. M., & Elsayed, M. A. A. (2018). The effect of parental education on child health: Quasi-experimental evidence from a reduction in the length of primary schooling in Egypt. Health Economics, 27 , 649–662.

Asfaw, A. A. (2018). The distributional effect of investment in early childhood nutrition: A panel quantile approach. World Development, 110 , 63–74.

Bain, L.E., Awah, P.K., Geraldine, N., Kindong, N.P., Siga, Y., Bernard, N., Tanjeko, A.T., 2013. Malnutrition in sub--Saharan Africa: Burden, causes and prospects. Pan Afr. Med. J. 15.

Berazneva, J., & Lee, D. R. (2013). Explaining the African food riots of 2007--2008: An empirical analysis. Food Policy, 39 , 28–39.

Black, R.E., Victora, C.G., Walker, S.P., Bhutta, Z.A., Christian, P., De Onis, M., Ezzati, M., Grantham-McGregor, S., Katz, J., Martorell, R., others, 2013. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet, 382 : 427–451.

Block, S. A., Kiess, L., Webb, P., Kosen, S., Moench-Pfanner, R., Bloem, M. W., & Timmer, C. P. (2004). Macro shocks and micro outcomes: Child nutrition during Indonesia’s crisis. Economics and Human Biology, 2 , 21–44.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2011). Introduction to meta-analysis . Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Google Scholar

Brown, M. E., Funk, C., Galu, G., & Choularton, R. (2007). Earlier famine warning possible using remote sensing and models. EOS. Transactions of the American Geophysical Union, 88 , 381–382.

Buhaug, H., Benjaminsen, T. A., Sjaastad, E., & Theisen, O. M. (2015). Climate variability, food production shocks, and violent conflict in sub-Saharan Africa. Environmental Research Letters, 10 , 125015.

Bundervoet, T., Verwimp, P., & Akresh, R. (2009). Health and civil war in rural Burundi. Journal of Human Resources, 44 , 536–563.

Collins, S., Dent, N., Binns, P., Bahwere, P., Sadler, K., & Hallam, A. (2006). Management of severe acute malnutrition in children. Lancet, 368 , 1992–2000.

Cooper, M., Brown, M. E., Azzarri, C., & Meinzen-Dick, R. (2019). Hunger, nutrition, and precipitation: Evidence from Ghana and Bangladesh. Population and Environment, 41 , 151–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-019-00323-8 .

de Onis, M., & Blössner, M. (2003). The World Health Organization global database on child growth and malnutrition: Methodology and applications. International Journal of Epidemiology, 32 , 518–526.

Delbiso, T. D., Rodriguez-Llanes, J. M., Donneau, A.-F., Speybroeck, N., & Guha-Sapir, D. (2017). Drought, conflict and children’s undernutrition in Ethiopia 2000--2013: a meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 95 , 94–102.

Devereux, S., 2000. Famine in the twentieth century. Institute of Development Studies.

Dilley, M. (2000). Warning and intervention: What kind of information does the response community need from the early warning community . Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance, Washington DC: USAID.

Douxchamps, S., Van Wijk, M. T., Silvestri, S., Moussa, A. S., Quiros, C., Ndour, N. Y. B., Buah, S., Somé, L., Herrero, M., Kristjanson, P., Ouedraogo, M., Thornton, P. K., Van Asten, P., Zougmoré, R., & Rufino, M. C. (2016). Linking agricultural adaptation strategies, food security and vulnerability: Evidence from West Africa. Regional Environmental Change, 16 , 1305–1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0838-6 .

Dunn, G. (2018). The impact of the Boko haram insurgency in Northeast Nigeria on childhood wasting: A double-difference study. Conflict and Health, 12 , 6.

Ekbrand, H., & Halleröd, B. (2018). The more gender equity, the less child poverty? A multilevel analysis of malnutrition and health deprivation in 49 low-and middle-income countries. World Development, 108 , 221–230.

Finlay, B., Agresti, A., 1986. Statistical methods for the social sciences. Dellen.

Funk, C. C., Dettinger, M. D., Michaelsen, J. C., Verdin, J. P., Brown, M. E., Barlow, M., & Hoell, A. (2008). The warm ocean dry Africa dipole threatens food insecure Africa, but could be mitigated by agricultural development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105 , 11081–11086. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708196105 .

Funk, C., Shukla, S., Thiaw, W.M., Rowland, J., Hoell, A., McNally, A., Husak, G., Novella, N., Budde, M., Peters-Lidard, C., others, 2019. Recognizing the famine early warning systems network: Over 30 years of drought early warning science advances and partnerships promoting global food security. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 100 : 1011–1027.

Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2006). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/ hierarchical models . London: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Ghobarah, H. A., Huth, P., & Russett, B. (2003). Civil wars kill and maim people-long after the shooting stops. The American Political Science Review, 97 , 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000613 .

Grace, K., Davenport, F., Funk, C., & Lerner, A. M. (2012). Child malnutrition and climate in sub-Saharan Africa: An analysis of recent trends in Kenya. Applied Geography, 35 , 405–413.

Grace, K., Brown, M., & McNally, A. (2014). Examining the link between food prices and food insecurity: A multi-level analysis of maize price and birthweight in Kenya. Food Policy, 46 , 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.01.010 .

Grace, K., Davenport, F., Hanson, H., Funk, C., & Shukla, S. (2015). Linking climate change and health outcomes: Examining the relationship between temperature, precipitation and birth weight in Africa. Global Environmental Change, 35 , 125–137.

GSMA, 2015. The Mobile economy 2014, URL: http://www. gsmamobileeconomylatinamerica. com/GSMA_Mobile_Economy_ LatinAmerica_2014. pdf. London, UK.

Haddad, L., Kennedy, E., & Sullivan, J. (1994). Choice of indicators for food security and nutrition monitoring. Food Policy, 19 , 329–343.

Hendrix, C. S., & Haggard, S. (2015). Global food prices, regime type, and urban unrest in the developing world. Journal of Peace Research, 52 , 143–157.

Hillbruner, C., Moloney, G., 2012. When early warning is not enough - lessons learned from the 2011 Somalia famine. Glob. Food Sec. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2012.08.001

Hoddinott, J., Maluccio, J. A., Behrman, J. R., Flores, R., & Martorell, R. (2008). Effect of a nutrition intervention during early childhood on economic productivity in Guatemalan adults. Lancet, 371 , 411–416.

Hoddinott, J., Alderman, H., Behrman, J. R., Haddad, L., & Horton, S. (2013). The economic rationale for investing in stunting reduction. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 9 , 69–82.

Howell, E., Waidmann, T., Holla, N., Birdsall, N., Jiang, K., 2018. The impact of civil conflict on child malnutrition and mortality, Nigeria, 2002–2013. Cent. Glob. Dev. Work. Pap.

Hsiang, S. M., & Burke, M. (2014). Climate, conflict, and social stability: What does the evidence say? Clim. Change, 123 , 39–55.

IPC (2012). Integrated food security phase classification technical manual version 2.0: evidence and standards for better food security decisions. . Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Rome.

Jacoby, H.G., Rabassa, M.J., Skoufias, E., 2014. Weather and child health in rural Nigeria.

Johnson, K. B., & Brown, M. E. (2014). Environmental risk factors and child nutritional status and survival in a context of climate variability and change. Applied Geography, 54 , 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.08.007 .

Jones, A. D., Ngure, F. M., Pelto, G., & Young,. S. L. (2013). What are we assessing when we measure food security? A compendium and review of current metrics. Advances in Nutrition, 4 , 481–505.

Jones, L., Jaspars, S., Pavanello, S., Ludi, E., Slater, R., Grist, N., Mtisi, S. (2010). Responding to a changing climate: Exploring how disaster risk reduction, social protection and livelihoods approaches promote features of adaptive capacity.

Kennedy, E., Branca, F., Webb, P., Bhutta, Z., & Brown, R. (2015). Setting the scene: An overview of issues related to policies and programs for moderate and severe acute malnutrition. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 36 , S9–S14.

Kimenju, S. C., & Qaim, M. (2016). The nutrition transition and indicators of child malnutrition. Food Secur., 8 , 571–583.

Kinyoki, D. K., Berkley, J. A., Moloney, G. M., Odundo, E. O., Kandala, N,. & Noor, A. M. (2016). Space--time mapping of wasting among children under the age of five years in Somalia from 2007 to 2010. Spatial and Spatio-temporal Epidemiology, 16 , 77–87.

Lautze, S., & Raven-Roberts, A. (2006). Violence and complex humanitarian emergencies: Implications for livelihoods models. Disasters, 30 , 383–401.

Leroy, J. L., Ruel, M., Frongillo, E. A., Harris, J., & Ballard, T. J. (2015). Measuring the food access dimension of food security: a critical review and mapping of indicators. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 36 , 167–195.

Lucas, A. M., & Wilson, N. L. (2013). Adult antiretroviral therapy and child health: Evidence from scale-up in Zambia. The American Economic Review, 103 , 456–461.

Maxwell, D., & Fitzpatrick, M. (2012). The 2011 Somalia famine: Context, causes, and complications. Global Food Security, 1 , 5–12.

Maxwell, D., Khalif, A., Hailey, P., Checchi, F., 2020. Determining famine: Multi-dimensional analysis for the twenty-first century. Food Policy in press.

Murali, J., & Afifi, T. (2014). Rainfall variability, food security and human mobility in the Janjgir-Champa district of Chhattisgarh state. India. Clim. Dev., 6 , 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2013.867248 .

Niles, M., Brown, M.E., 2017. A multi-country assessment of factors related to smallholder food security in varying rainfall conditions. Sci. Rep.

Phalkey, R. K., Aranda-Jan, C., Marx, S., Höfle, B., & Sauerborn, R. (2015). Systematic review of current efforts to quantify the impacts of climate change on undernutrition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112 , E4522–E4529.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Raleigh, C., Linke, A., Hegre, H., & Karlsen, J. (2010). Introducing ACLED – Armed conflict location and event data. Journal of Peace Research, 47 , 651–660.

Raleigh, C., Choi, H. J., & Kniveton, D. (2015). The devil is in the details: An investigation of the relationships between conflict, food price and climate across Africa. Global Environmental Change, 32 , 187–199.

Rashad, A. S., & Sharaf, M. F. (2018). Economic growth and child malnutrition in Egypt: New evidence from national demographic and health survey. Social Indicators Research, 135 , 769–795.

Rodriguez, L. (2016). Intrahousehold inequalities in child rights and well-being. A barrier to progress? World Development, 83 , 111–134.

Sen, A. K. (1981). Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlements and deprivation . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Shively, G., Sununtnasuk, C., & Brown, M. E. (2015). Environmental variability and child growth in Nepal. Health Place in press, 35 , 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.06.008 .

Skoufias, E., & Vinha, K. (2012). Climate variability and child height in rural Mexico. Economics and Human Biology, 10 , 54–73.

Smith, L. C., & Haddad, L. (2001). How important is improving food availability for reducing child malnutrition in developing countries? Agricultural Economics, 26 , 191–204.

Smith, L. C., & Haddad, L. (2015). Reducing child undernutrition: Past drivers and priorities for the post-MDG era. World Development, 68 , 180–204.

Smith, L. C., Ruel, M. T., & Ndiaye, A. (2005). Why is child malnutrition lower in urban than in rural areas? Evidence from 36 developing countries. World Development, 33 , 1285–1305.

UNSCN. (2010). Sixth report on the world nutrition situation . Italy: Rome.

Walker, S. P., Chang, S. M., Wright, A., Osmond, C., & Grantham-McGregor, S. M. (2015). Early childhood stunting is associated with lower developmental levels in the subsequent generation of children. The Journal of Nutrition, 145 , 823–828. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.200261 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

WHO (2010). Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) country profile indicators: interpretation guide.

WHO (2020) Severe acute malnutrition. Nutrition topics. United Nations World Health Organization.

Wrottesley, S. V., Lamper, C., & Pisa, P. T. (2015). Review of the importance of nutrition during the first 1000 days: Maternal nutritional status and its associations with fetal growth and birth, neonatal and infant outcomes among African women. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, 7 , 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2040174415001439 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yamano, T., Alderman, H., & Christiaensen, L. (2005). Child growth, shocks, and food aid in rural Ethiopia. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 87 , 273–288.

Young, H., Borrel, A., Holland, D., & Salama, P. (2004). Public nutrition in complex emergencies. Lancet, 364 , 1899–1909.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland, 7251 Preinkert Drive, 2181 LeFrak Hall, College Park, MD, 20742, USA

Molly E. Brown

Department of Government & Politics and Center for International Development and Conflict Management, University of Maryland, 2117 Chincoteague Hall, 7401 Preinkert Drive, College Park, MD, 20142, USA

David Backer, Trey Billing & Paul Huth

Department of Political Science, Auburn University, 7080 Haley Center, Auburn, AL, 36849, USA

Peter White

Department of Geography, Environment, and Society, Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, 55455, USA

Kathryn Grace

International Health, Johns Hopkins University, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Room E8132, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA

Shannon Doocy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Molly E. Brown .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 128 kb)

(PDF 69 kb)

(DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Brown, M.E., Backer, D., Billing, T. et al. Empirical studies of factors associated with child malnutrition: highlighting the evidence about climate and conflict shocks. Food Sec. 12 , 1241–1252 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01041-y

Download citation

Received : 07 July 2019

Accepted : 30 April 2020

Published : 21 May 2020

Issue Date : December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01041-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Food security

- Undernutrition

- Literature review

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Tackling malnutrition: a systematic review of 15-year research evidence from INDEPTH health and demographic surveillance systems

Affiliations.

- 1 INDEPTH Network, Accra, Ghana.

- 2 Department of Demography and Population Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa; [email protected].

- 3 Library Department, Systems and Technical Services, Mangosuthu University of Technology, Umlazi, Durban, South Africa.

- 4 Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa.

- 5 Ouagadougou HDSS, ISSP, University of Ouagadougou, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

- 6 MRC Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit (Agincourt), School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- 7 Umeå Centre for Global Health Research, Division of Epidemiology and Global Health, Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

- 8 Independent Consultant, Mwanza, Tanzania.

- 9 School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- 10 Faculty of Public Health, Hanoi Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam.

- PMID: 26519130

- PMCID: PMC4627942

- DOI: 10.3402/gha.v8.28298

Background: Nutrition is the intake of food in relation to the body's dietary needs. Malnutrition results from the intake of inadequate or excess food. This can lead to reduced immunity, increased susceptibility to disease, impaired physical and mental development, and reduced productivity.

Objective: To perform a systematic review to assess research conducted by the International Network for the Demographic Evaluation of Populations and their Health (INDEPTH) of health and demographic surveillance systems (HDSSs) over a 15-year period on malnutrition, its determinants, the effects of under and over nutrition, and intervention research on malnutrition in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods: Relevant publication titles were uploaded onto the Zotero research tool from different databases (60% from PubMed). Using the keywords 'nutrition', 'malnutrition', 'over and under nutrition', we selected publications that were based only on data generated through the longitudinal HDSS platform. All titles and abstracts were screened to determine inclusion eligibility and full articles were independently assessed according to inclusion/exclusion criteria. For inclusion in this study, papers had to cover research on at least one of the following topics: the problem of malnutrition, its determinants, its effects, and intervention research on malnutrition. One hundred and forty eight papers were identified and reviewed, and 67 were selected for this study.

Results: The INDEPTH research identified rising levels of overweight and obesity, sometimes in the same settings as under-nutrition. Urbanisation appears to be protective against under-nutrition, but it heightens the risk of obesity. Appropriately timed breastfeeding interventions were protective against malnutrition.

Conclusions: Although INDEPTH has expanded the global knowledge base on nutrition, many questions remain unresolved. There is a need for more investment in nutrition research in LMICs in order to generate evidence to inform policies in these settings.

Keywords: LMICs; health and demographic surveillance system; low- and middle-income countries; malnutrition; nutrition; overweight; under and over nutrition.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Systematic Review

- Biomedical Research*

- Developing Countries

- Global Health

- Health Status

- Malnutrition*

- Nutritional Requirements

- Population Surveillance / methods*

Grants and funding

- 097318/Wellcome Trust/United Kingdom

78 Malnutrition Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best malnutrition topic ideas & essay examples, 👍 simple & easy malnutrition essay titles, 🎓 good research topics about malnutrition, ❓ research question about malnutrition.

- Obesity as a Form of Malnutrition and Its Effects Obesity is considered a malnutrition because the extended consumption of nutrients can still lead to the lack macro- and microelements. Overweight and obesity are serious disorders affecting a substantial part of the current population.

- Healthy Nutrition: Case Study of Malnutrition Sofia’s possible malnutrition might be owing to her demanding schedule and lack of prenatal care, which is an important part of a healthy pregnancy. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Malnutrition in Hospitalized Patients: Intended and Potential Outcomes Furthermore, there is a chance that the patients will be able to determine malnutrition at its early stages and inform nurses about the problem. As a result, a rise in the number of positive patient […]

- Malnutrition in South Africa: Public Health Policy The global food systems are highly dysfunctional, creating malnutrition crises in certain parts of the world which are the primary cause of death and disease.

- Malnutrition: Criteria and Description of Statement of the Problem Between adequate nutrition programs and malnutrition primary prevention programs, what approach is the most effective to enhance children’s development? What are the dissimilarities between adequate nutrition programs and malnutrition primary prevention programs?

- Obesity and Malnutrition: Who Is at Fault I would like to note that in both the interview and the article Nestle states that malnutrition is not only the responsibility of the consumers.

- Child Malnutrition in the GCC Countries Countries which have faired badly in the recent past include Kuwait and Qatar which saw an increase in their child malnutrition rates from 5% in the 1990s to 10% in the mid-2000s.

- Child Malnutrition: Term Definition Majority of the people in the globe specifically in the rural areas do not have access to safe drinking water and most of them lack the access of good sanitation.

- The Issues of Malnutrition and the Healing Process The issues of malnutrition and the healing process are regarded in lots of journals and scientific literature. The nutritional status of the patient previous to and after a surgical procedure is significant for speedy and […]

- Integrated Nursing Practice Addressing Malnutrition The benefits of the specified intervention include an opportunity to reduce the extent of stress experienced by the patient and create the basis for the future patient education.

- Malnutrition in Children as a Global Health Issue The peculiarity of this initiative is not to support children and control their feeding processes but prevent pediatric malnutrition even before a child is born.

- Malnutrition: Major Risk Factors and Causes The normal functioning of body organs is something that requires an adequate amount of mineral salts, fluids, and nutrients that are derived from different food materials. The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to analyze […]

- Early Enteral Nutrition to Prevent Malnutrition The choice of the method depends on the state of a patient, his/her disease, and the peculiarities of the health problem that should be solved at the moment.

- Accelerating Progress Toward Reducing Child Malnutrition in India

- Addressing Chronic Malnutrition Through Multi-Sectoral, Sustainable Approaches

- Addressing the Double Burden of Malnutrition in ASEAN

- Battle Against Starvation and Malnutrition

- Behaviors Associated With Child Malnutrition

- Childhood Malnutrition and Schooling in the Terai Region of Nepal

- Chronic Malnutrition and Its Effects on Children

- Closing the Rural-Urban Gap in Child Malnutrition: Evidence From Paraguay

- Child Malnutrition and Antenatal Care: Evidence From Three Latin American Countries

- Combating Child Chronic Malnutrition and Anemia in Peru

- Death From Stroke During the Danish Malnutrition Period 1999-2007

- Comparing Peri-Urban Versus Rural Poverty and Child Malnutrition Reduction

- Deforestation and Household- And Individual-Level Double Burden of Malnutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Combining Insights From Quantile and Ordinal Regression: Child Malnutrition in Guatemala

- Child Malnutrition and Poverty: The Case of Pakistan

- Developing Countries Suffer From Poverty and Malnutrition

- Diets, Malnutrition, and Disease: The Indian Experience

- Child Malnutrition and Mortality in China and Vietnam in a Comparative Perspective

- Effects of Parental Education on Malnutrition Among Children in Brazil

- How Hunger and Malnutrition Influence the Health and Development of Communities

- Child Malnutrition and the Provision of Water and Sanitation in the Philippines

- Linking Economic Growth and Child Malnutrition in Egypt

- Economic Growth, Poverty, and Malnutrition in India

- Child Malnutrition, Social Development, and Health Services in the Andean Region

- Ending Malnutrition: From Commitment to Action

- Environmental Factors and Children’s Malnutrition in Ethiopia

- Children’s Malnutrition and Horizontal Inequalities in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Difference Between Undernutrition and Malnutrition

- The Impact of Public Expenditure on Child Malnutrition in Peru

- Factors Affecting the Prevalence of Malnutrition

- Fetal Malnutrition and Academic Success: Evidence From Muslim Immigrants in Denmark

- Fighting Poverty and Child Malnutrition: On the Design of Foreign Aid Policies

- Factors Influencing the Occurrence of Malnutrition Health and Social Care

- An Opportunity to Minimize Malnutrition and Hunger in Developing Countries

- Geography and Culture Matter for Malnutrition in Bolivia

- Household and Community HIV/AIDS Status and Child Malnutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Hunger and Malnutrition Are a Problem Everywhere

- Identifying Risk Factors for Severe Childhood Malnutrition by Boosting Additive Quantile Regression

- Inequality, Hunger, and Malnutrition: Power Matters

- Hunger, Malnutrition and Millennium Development Goals: What Can Be Done

- What Happens to Your Body Durimg Malnutrition?

- What Causes Malnutrition?

- What Is the Treatment for Malnutrition?

- How Long Does It Take To Recover From Malnutrition in Adults?

- How Do Doctors Test for Malnutrition?

- What Is the Largest Reason for Malnutrition?

- How Do Doctors Diagnose Malnutrition?

- How Long Can You Live With Malnutrition?

- Which Medicine Is Best for Malnutrition?

- What Drugs Cause Malnutrition?

- Can Blood Test Detect Malnutrition?

- What Bloodwork Shows Malnutrition?

- What Are the Most Common Signs of Malnutrition?

- How Is Malnutrition Best Managed?

- What Social Factors Cause Malnutrition?

- What Are the Long Term Effects of Malnutrition?

- What Are Immediate Cause of Malnutrition?

- What Is the Best Way for Early Detection of Malnutrition?

- What Are the Complications of Malnutrition?

- How Is Severe Malnutrition Diagnosed?

- What Infection Causes Malnutrition?

- What Are the Diseases Caused by Malnutrition?

- How Is Malnutrition Treated in Adults?

- How Does Malnutrition Affect the Brain in Adults?

- Can You Get Brain Damage From Malnutrition?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 26). 78 Malnutrition Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/malnutrition-essay-topics/

"78 Malnutrition Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/malnutrition-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '78 Malnutrition Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "78 Malnutrition Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/malnutrition-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "78 Malnutrition Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/malnutrition-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "78 Malnutrition Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/malnutrition-essay-topics/.

- Metabolic Disorders Questions

- Weight Loss Essay Titles

- Vitamins Research Topics

- Eating Disorders Questions

- Diabetes Questions

- World Hunger Research Topics

- Diet Essay Topics

- Obesity Ideas

- Poverty Essay Titles

- Food Essay Ideas

- Dietary Supplements Questions

- Allergy Research Ideas

- Famine Essay Titles

- Anorexia Essay Ideas

- Fast Food Essay Titles

- Frontiers in Public Health

- Life-Course Epidemiology and Social Inequalities in Health

- Research Topics

Malnutrition: A Cause or a Consequence of Poverty?

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

In the 21st century, malnutrition is considered as one of the many health inequalities affecting humanity worldwide, regardless of their income status. Malnutrition is a universal issue with several different forms. It has been observed that one or more forms of malnutrition can appear in a single country ...

Keywords : malnutrition, poverty, diet, eating habits, inequalities, low-income

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

Malnutrition enteropathy in Zambian and Zimbabwean children with severe acute malnutrition: A multi-arm randomized phase II trial

- Kanta Chandwe 1 na1 ,

- Mutsa Bwakura-Dangarembizi 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Beatrice Amadi 1 ,

- Gertrude Tawodzera 2 ,

- Deophine Ngosa 1 ,

- Anesu Dzikiti 2 ,

- Nivea Chulu 1 ,

- Robert Makuyana 2 ,

- Kanekwa Zyambo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5686-5319 1 ,

- Kuda Mutasa 2 ,

- Chola Mulenga 1 ,

- Ellen Besa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5606-9435 1 ,

- Jonathan P. Sturgeon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1318-1739 2 , 4 ,

- Shepherd Mudzingwa 2 ,

- Bwalya Simunyola 1 ,

- Lydia Kazhila 1 ,

- Masuzyo Zyambo 5 ,

- Hazel Sonkwe 5 ,

- Batsirai Mutasa 2 ,

- Miyoba Chipunza 1 ,

- Virginia Sauramba 2 ,

- Lisa Langhaug ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9131-8158 2 ,

- Victor Mudenda 1 ,

- Simon H. Murch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3870-8229 6 ,

- Susan Hill 7 ,

- Raymond J. Playford ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1235-8504 8 , 9 ,

- Kelley VanBuskirk ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0004-9110-9059 1 ,

- Andrew J. Prendergast ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7904-7992 2 , 4 &

- Paul Kelly ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0844-6448 1 , 4

Nature Communications volume 15 , Article number: 2910 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

196 Accesses

38 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Intestinal diseases

- Paediatric research

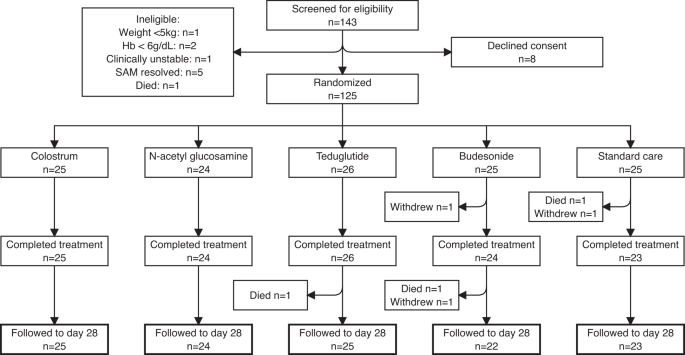

Malnutrition underlies almost half of all child deaths globally. Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) carries unacceptable mortality, particularly if accompanied by infection or medical complications, including enteropathy. We evaluated four interventions for malnutrition enteropathy in a multi-centre phase II multi-arm trial in Zambia and Zimbabwe and completed in 2021. The purpose of this trial was to identify therapies which could be taken forward into phase III trials. Children of either sex were eligible for inclusion if aged 6–59 months and hospitalised with SAM (using WHO definitions: WLZ <−3, and/or MUAC <11.5 cm, and/or bilateral pedal oedema), with written, informed consent from the primary caregiver. We randomised 125 children hospitalised with complicated SAM to 14 days treatment with (i) bovine colostrum ( n = 25), (ii) N-acetyl glucosamine ( n = 24), (iii) subcutaneous teduglutide ( n = 26), (iv) budesonide ( n = 25) or (v) standard care only ( n = 25). The primary endpoint was a composite of faecal biomarkers (myeloperoxidase, neopterin, α 1 -antitrypsin). Laboratory assessments, but not treatments, were blinded. Per-protocol analysis used ANCOVA, adjusted for baseline biomarker value, sex, oedema, HIV status, diarrhoea, weight-for-length Z-score, and study site, with pre-specified significance of P < 0.10. Of 143 children screened, 125 were randomised. Teduglutide reduced the primary endpoint of biomarkers of mucosal damage (effect size −0.89 (90% CI: −1.69,−0.10) P = 0.07), while colostrum (−0.58 (−1.4, 0.23) P = 0.24), N-acetyl glucosamine (−0.20 (−1.01, 0.60) P = 0.67), and budesonide (−0.50 (−1.33, 0.33) P = 0.32) had no significant effect. All interventions proved safe. This work suggests that treatment of enteropathy may be beneficial in children with complicated malnutrition. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT03716115.

Similar content being viewed by others

Diagnosis and management of Guillain–Barré syndrome in ten steps

Sonja E. Leonhard, Melissa R. Mandarakas, … Bart C. Jacobs

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Ketan K. Dhatariya, Nicole S. Glaser, … Guillermo E. Umpierrez

Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: consensus report of the 28th Acute Disease Quality Initiative workgroup

Alexander Zarbock, Mitra K. Nadim, … Lui G. Forni

Introduction

Despite 17 million annual worldwide cases of childhood severe acute malnutrition (SAM), and its high associated mortality when children are hospitalized with complications 1 , 2 , there have been few new treatments for over three decades for children with complicated SAM. Current management follows steps in the WHO guidelines launched in 1999 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 but there is an acknowledged lack of evidence for many interventions 1 , 7 and consensus that more trials are needed. In sub-Saharan Africa, HIV has had a major impact on SAM, causing higher mortality during 8 , 9 and after admission 2 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , complications like persistent diarrhoea 9 , and prolonged hospital admission.

Even after recovery from acute SAM, there are very common chronic consequences, including both stunting of linear growth and short- and long-term inhibition of neurodevelopmental potential 14 . The effects of chronic malnutrition upon cognitive functioning are particularly notable in the domains of attention, memory and learning, contributing to poor school performance 15 and corresponding with abnormalities on neuroimaging 16 . Such long-term consequences may not be averted by providing improved nutrition alone, as small intestinal absorption of nutrients and essential micronutrients is compromised by ongoing malnutrition enteropathy 17 . Effective treatment of malnutrition enteropathy is thus likely to have major benefits for the development of large numbers of children within resource-poor countries.