- Key Differences

Know the Differences & Comparisons

Difference Between Article and Essay

An article is nothing but a piece of writing commonly found in newspapers or websites which contain fact-based information on a specific topic. It is published with the aim of making the reader aware of something and keeping them up to date.

An essay is a literary work, which often discusses ideas, experiences and concepts in a clear and coherent way. It reflects the author’s personal view, knowledge and research on a specific topic.

Content: Article Vs Essay

Comparison chart, definition of article.

An ‘article’ can be described as any form of written information which is produced either in a printed or electronic form, in newspaper, magazine, journal or website. It aims at spreading news, results of surveys, academic analysis or debates.

An article targets a large group of people, in order to fascinate the readers and engage them. Hence, it should be such that to retain the interest of the readers.

It discusses stories, reports and describes news, present balanced argument, express opinion, provides facts, offers advice, compares and contrast etc. in a formal or informal manner, depending upon the type of audience.

For writing an article one needs to perform a thorough research on the matter, so as to provide original and authentic information to the readers.

Components of Article

- Title : An article contains a noticeable title which should be intriguing and should not be very long and descriptive. However, it should be such that which suggests the theme or issue of the information provided.

- Introduction : The introduction part must clearly define the topic, by giving a brief overview of the situation or event.

- Body : An introduction is followed by the main body which presents the complete information or news, in an elaborative way, to let the reader know about the exact situation.

- Conclusion : The article ends with a conclusion, which sums up the entire topic with a recommendation or comment.

Definition of Essay

An essay is just a formal and comprehensive piece of literature, in which a particular topic is discussed thoroughly. It usually highlights the writer’s outlook, knowledge and experiences on that particular topic. It is a short literary work, which elucidates, argues and analyzes a specific topic.

The word essay is originated from the Latin term ‘exagium’ which means ‘presentation of a case’. Hence, writing an essay means to state the reasons or causes of something, or why something should be done or should be the case, which validates a particular viewpoint, analysis, experience, stories, facts or interpretation.

An essay is written with the intent to convince or inform the reader about something. Further, for writing an essay one needs to have good knowledge of the subject to explain the concept, thoroughly. If not so, the writer will end up repeating the same points again and again.

Components of the Essay

- Title : It should be a succinct statement of the proposition.

- Introduction : The introduction section of the essay, should be so interesting which instantly grabs the attention of the reader and makes them read the essay further. Hence, one can start with a quote to make it more thought-provoking.

- Body : In the main body of the essay, evidence or reasons in support of the writer’s ideas or arguments are provided. One should make sure that there is a sync in the paragraphs of the main body, as well as they, should maintain a logical flow.

- Conclusion : In this part, the writer wraps up all the points in a summarized and simplified manner.

Key Differences Between Article and Essay

Upcoming points will discuss the difference between article and essay:

- An article refers to a written work, published in newspapers, journals, website, magazines etc, containing news or information, in a specific format. On the other hand, an essay is a continuous piece of writing, written with the aim of convincing the reader with the argument or merely informing the reader about the fact.

- An article is objective in the sense that it is based on facts and evidence, and simply describes the topic or narrate the event. As against, an essay is subjective, because it is based on fact or research-based opinion or outlook of a person on a specific topic. It analyses, argues and criticizes the topic.

- The tone used in an article is conversational, so as to make the article easy to understand and also keeping the interest of the reader intact. On the contrary, an essay uses educational and analytical tone.

- An article may contain headings, which makes it attractive and readable. In contrast, an essay does not have any headings, sections or bullet points, however, it is a coherent and organized form of writing.

- An article is always written with a definite objective, which is to inform or make the readers aware of something. Further, it is written to cater to a specific niche of audience. Conversely, an essay is written in response to a particular assertion or question. Moreover, it is not written with a specific group of readers in mind.

- An article is often supported by photographs, charts, statistics, graphs and tables. As opposed, an essay is not supported by any photographs, charts, or graphs.

- Citations and references are a must in case of an essay, whereas there is no such requirement in case of an article.

By and large, an article is meant to inform the reader about something, through news, featured stories, product descriptions, reports, etc. On the flip side, an essay offers an analysis of a particular topic, while reflecting a detailed account of a person’s view on it.

You Might Also Like:

Anna H. Smith says

November 15, 2020 at 6:21 pm

Great! Thank you for explaining the difference between an article and an academic essay so eloquently. Your information is so detailed and very helpful. it’s very educative, Thanks for sharing.

Sunita Singh says

December 12, 2020 at 7:11 am

Thank you! That’s quite helpful.

Saba Zia says

March 8, 2021 at 12:33 am

Great job!! Thank u for sharing this explanation and detailed difference between essay and article. It is really helpful.

Khushi Chaudhary says

February 7, 2021 at 2:38 pm

Thank you so much! It is really very easy to understand & helpful for my test.

Dury Frizza says

July 25, 2022 at 8:18 pm

Thanks a lot for sharing such a clear and easily understood explanation!!!!.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- English Difference Between

- Difference Between Article And Essay

Difference between Article and Essay

Are an article and an essay the same? Is there something that makes one different from the other? Check out this article to find out.

What is an Article?

An article is a report or content published in a newspaper, magazine, journal or website, either in printed or electronic form. When it comes to articles, a sizable readership is considered. It might be supported by studies, research, data, and other necessary elements. Articles may be slightly brief or lengthy, with a maximum count of 1500 words. It educates the readers on various ideas/concepts and is prepared with a clear aim in mind.

Articles, which can be found in newspapers, journals, encyclopaedias, and now, most commonly, online, inform and keep readers informed about many topics.

What is an Essay?

An essay is a formal, in-depth work of literature that analyses and discusses a specific problem or subject. It refers to a brief piece of content on a specific topic. Students are frequently required to write essays in response to questions or propositions in their academic coursework. It doesn’t target any particular readers.

Through essays, the author or narrator offers unique ideas or opinions on a given subject or question while maintaining an analytical and formal tone.

Keep learning and stay tuned to get the latest update on GATE , GATE Preparation Books & GATE Answer Key , and more.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Home » Education » Difference Between Article and Essay

Difference Between Article and Essay

Main difference – article vs essay.

Articles and essays are two forms of academic writing. Though there are certain similarities between them, there are also distinct differences between them. These differences are based on the format, purpose and content. Before looking at the difference between article and essay, let us first look at the definitions of these two words. An essay is a piece of writing that describes, analyzes and evaluates a particular topic whereas an article is a piece of writing that is included with others in a newspaper or other publications. The main difference between article and essay is that an article is written to inform the readers about some concept whereas an essay is usually written in response to a question or proposition .

What is an Article

An article is a piece of writing that is included with others in a newspaper, magazine or other publication . It is a written composition that is nonfiction and prose. Articles can be found in magazines, encyclopedias, websites, newspapers or other publications; the content and the structure of an article may depend on the source. For example, an article can be an editorial, review, feature article, scholarly articles, etc.

What is an Essay

An essay is a piece of writing that describes, analyzes and evaluates a certain topic or an issue . It is a brief, concise form of writing that contains an introduction, a body that is comprised of few support paragraphs, and a conclusion. An essay may inform the reader, maintain an argument, analyse an issue or elaborate on a concept. An essay is a combination of statistics, facts and writer’s opinions and views.

Article is a piece of writing that is included with others in a newspaper, magazine or other publication.

Essay is a short piece of writing on a particular subject.

Article is written to inform the readers about some concept.

Essay is generally written as a response to a question or proposition.

Articles follow heading and subheadings format.

Essays are not written under headings and subheadings.

Articles do not require citations or references.

Essays require citations and references.

Visual Effects

Articles are often accompanied by photographs, charts and graphs.

Essays do not require photographs.

Articles are objective as they merely describe a topic.

About the Author: admin

you may also like these.

The Essay: History and Definition

Attempts at Defining Slippery Literary Form

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

"One damned thing after another" is how Aldous Huxley described the essay: "a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything."

As definitions go, Huxley's is no more or less exact than Francis Bacon's "dispersed meditations," Samuel Johnson's "loose sally of the mind" or Edward Hoagland's "greased pig."

Since Montaigne adopted the term "essay" in the 16th century to describe his "attempts" at self-portrayal in prose , this slippery form has resisted any sort of precise, universal definition. But that won't an attempt to define the term in this brief article.

In the broadest sense, the term "essay" can refer to just about any short piece of nonfiction -- an editorial, feature story, critical study, even an excerpt from a book. However, literary definitions of a genre are usually a bit fussier.

One way to start is to draw a distinction between articles , which are read primarily for the information they contain, and essays, in which the pleasure of reading takes precedence over the information in the text . Although handy, this loose division points chiefly to kinds of reading rather than to kinds of texts. So here are some other ways that the essay might be defined.

Standard definitions often stress the loose structure or apparent shapelessness of the essay. Johnson, for example, called the essay "an irregular, indigested piece, not a regular and orderly performance."

True, the writings of several well-known essayists ( William Hazlitt and Ralph Waldo Emerson , for instance, after the fashion of Montaigne) can be recognized by the casual nature of their explorations -- or "ramblings." But that's not to say that anything goes. Each of these essayists follows certain organizing principles of his own.

Oddly enough, critics haven't paid much attention to the principles of design actually employed by successful essayists. These principles are rarely formal patterns of organization , that is, the "modes of exposition" found in many composition textbooks. Instead, they might be described as patterns of thought -- progressions of a mind working out an idea.

Unfortunately, the customary divisions of the essay into opposing types -- formal and informal, impersonal and familiar -- are also troublesome. Consider this suspiciously neat dividing line drawn by Michele Richman:

Post-Montaigne, the essay split into two distinct modalities: One remained informal, personal, intimate, relaxed, conversational and often humorous; the other, dogmatic, impersonal, systematic and expository .

The terms used here to qualify the term "essay" are convenient as a kind of critical shorthand, but they're imprecise at best and potentially contradictory. Informal can describe either the shape or the tone of the work -- or both. Personal refers to the stance of the essayist, conversational to the language of the piece, and expository to its content and aim. When the writings of particular essayists are studied carefully, Richman's "distinct modalities" grow increasingly vague.

But as fuzzy as these terms might be, the qualities of shape and personality, form and voice, are clearly integral to an understanding of the essay as an artful literary kind.

Many of the terms used to characterize the essay -- personal, familiar, intimate, subjective, friendly, conversational -- represent efforts to identify the genre's most powerful organizing force: the rhetorical voice or projected character (or persona ) of the essayist.

In his study of Charles Lamb , Fred Randel observes that the "principal declared allegiance" of the essay is to "the experience of the essayistic voice." Similarly, British author Virginia Woolf has described this textual quality of personality or voice as "the essayist's most proper but most dangerous and delicate tool."

Similarly, at the beginning of "Walden, " Henry David Thoreau reminds the reader that "it is ... always the first person that is speaking." Whether expressed directly or not, there's always an "I" in the essay -- a voice shaping the text and fashioning a role for the reader.

Fictional Qualities

The terms "voice" and "persona" are often used interchangeably to suggest the rhetorical nature of the essayist himself on the page. At times an author may consciously strike a pose or play a role. He can, as E.B. White confirms in his preface to "The Essays," "be any sort of person, according to his mood or his subject matter."

In "What I Think, What I Am," essayist Edward Hoagland points out that "the artful 'I' of an essay can be as chameleon as any narrator in fiction." Similar considerations of voice and persona lead Carl H. Klaus to conclude that the essay is "profoundly fictive":

It seems to convey the sense of human presence that is indisputably related to its author's deepest sense of self, but that is also a complex illusion of that self -- an enactment of it as if it were both in the process of thought and in the process of sharing the outcome of that thought with others.

But to acknowledge the fictional qualities of the essay isn't to deny its special status as nonfiction.

Reader's Role

A basic aspect of the relationship between a writer (or a writer's persona) and a reader (the implied audience ) is the presumption that what the essayist says is literally true. The difference between a short story, say, and an autobiographical essay lies less in the narrative structure or the nature of the material than in the narrator's implied contract with the reader about the kind of truth being offered.

Under the terms of this contract, the essayist presents experience as it actually occurred -- as it occurred, that is, in the version by the essayist. The narrator of an essay, the editor George Dillon says, "attempts to convince the reader that its model of experience of the world is valid."

In other words, the reader of an essay is called on to join in the making of meaning. And it's up to the reader to decide whether to play along. Viewed in this way, the drama of an essay might lie in the conflict between the conceptions of self and world that the reader brings to a text and the conceptions that the essayist tries to arouse.

At Last, a Definition—of Sorts

With these thoughts in mind, the essay might be defined as a short work of nonfiction, often artfully disordered and highly polished, in which an authorial voice invites an implied reader to accept as authentic a certain textual mode of experience.

Sure. But it's still a greased pig.

Sometimes the best way to learn exactly what an essay is -- is to read some great ones. You'll find more than 300 of them in this collection of Classic British and American Essays and Speeches .

- What is a Familiar Essay in Composition?

- What Does "Persona" Mean?

- What Are the Different Types and Characteristics of Essays?

- Rhetorical Analysis Definition and Examples

- What Is a Personal Essay (Personal Statement)?

- The Writer's Voice in Literature and Rhetoric

- Point of View in Grammar and Composition

- What Is Colloquial Style or Language?

- What Is Literary Journalism?

- Definition and Examples of Formal Essays

- What Is Expository Writing?

- The Difference Between an Article and an Essay

- First-Person Point of View

- What Is Tone In Writing?

- What is an Implied Author?

What this handout is about

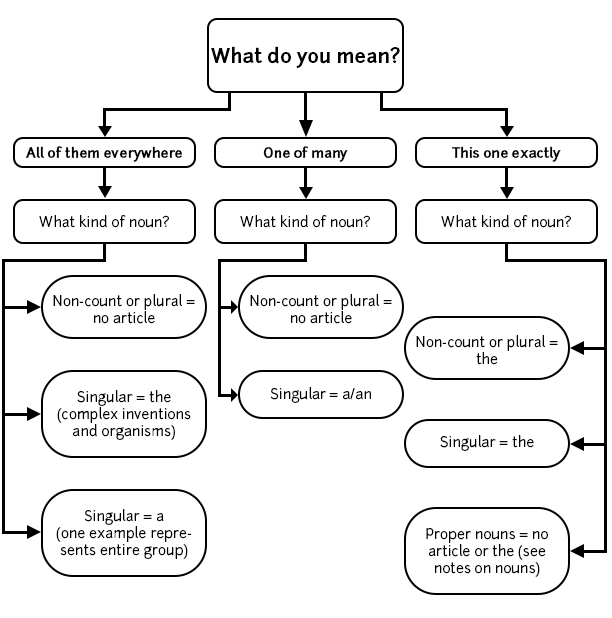

When we use nouns in English, articles (a, an, and the) specify which and how many nouns we mean. To choose the correct article for your sentence, you need to answer two questions. First, do I mean this one exactly, one of many, or all of them everywhere? Second, is the noun count or non-count? This handout explains these questions and how their answers help determine which article to use.

Using this handout

As you use the handout, try to keep three things in mind:

- First, this handout will be most effective if you use it as a tool. Every time you read this handout, read it along side another piece of writing (a journal article, a magazine, a web page, a novel, a text book, etc.). Locate a few nouns in the reading, and use the handout to analyze the article usage. If you practice a little bit at a time, this kind of analysis can help you develop a natural sensitivity to this complex system.

- Second, using articles correctly is a skill that develops over time through lots of reading, writing, speaking and listening. Think about the rules in this handout, but also try to pay attention to how articles are being used in the language around you. Simply paying attention can also help you develop a natural sensitivity to this complex system.

- Finally, although using the wrong article may distract a reader’s attention, it usually does not prevent the reader from understanding your meaning. So be patient with yourself as you learn.

Basic rules

This is a simple list, but understanding it and remembering it is crucial to using articles correctly.

Rule # 1: Every time a noun is mentioned, the writer is referring to:

- All of them everywhere (“generic” reference),

- One of many, (“indefinite” reference) or

- This one exactly (“definite” reference)

Rule # 2: Every kind of reference has a choice of articles:

- All of them everywhere…(Ø, a/an, the)

- One of many……………..(Ø, a/an)

- This one exactly…………(Ø, the)

(Ø = no article)

Rule # 3: The choice of article depends upon the noun and the context. This will be explained more fully below.

Basic questions

To choose the best article, ask yourself these questions:

- “What do I mean? Do I mean all of them everywhere, one of many, or this one exactly?”

- “What kind of noun is it? Is it countable or not? Is it singular or plural? Does it have any special rules?”

Your answers to these questions will usually determine the correct article choice, and the following sections will show you how.

When you mean “all of them everywhere”

Talking about “all of them everywhere” is also called “generic reference.” We use it to make generalizations: to say something true of all the nouns in a particular group, like an entire species of animal. When you mean “all of them everywhere,” you have three article choices: Ø, a/an, the. The choice of article depends on the noun. Ask yourself, “What kind of noun is it?”

Non-count nouns = no article (Ø)

- Temperature is measured in degrees.

- Money makes the world go around.

Plural nouns = no article (Ø)

- Volcanoes are formed by pressure under the earth’s surface.

- Quagga zebras were hunted to extinction.

Singular nouns = the

- The computer is a marvelous invention.

- The elephant lives in family groups.

Note: We use this form (the + singular) most often in technical and scientific writing to generalize about classes of animals, body organs, plants, musical instruments, and complex inventions. We do not use this form for simple inanimate objects, like books or coat racks. For these objects, use (Ø + plural).

Singular nouns = a/an when a single example represents the entire group

- A rose by any other name would still smell as sweet.

- A doctor is a highly educated person. Generally speaking, a doctor also has tremendous earning potential.

How do you know it’s generic? The “all…everywhere” test

Here’s a simple test you can use to identify generic references while you’re reading. To use this test, substitute “all [plural noun] everywhere” for the noun phrase. If the statement is still true, it’s probably a generic reference. Example:

- A whale protects its young—”All whales everywhere” protect their young. (true—generic reference)

- A whale is grounded on the beach—”All whales everywhere” are grounded on the beach. (not true, so this is not a generic reference; this “a” refers to “one of many”)

You’ll probably find generic references most often in the introduction and conclusion sections and at the beginning of a paragraph that introduces a new topic.

When you mean “one of many”

Talking about “one of many” is also called “indefinite reference.” We use it when the noun’s exact identity is unknown to one of the participants: the reader, the writer, or both. Sometimes it’s not possible for the reader or the writer to identify the noun exactly; sometimes it’s not important. In either case, the noun is just “one of many.” It’s “indefinite.” When you mean “one of many,” you have two article choices: Ø, a/an. The choice of article depends on the noun. Ask yourself, “What kind of noun is it?”

- Our science class mixed boric acid with water today.

- We serve bread and water on weekends.

- We’re happy when people bring cookies!

- We need volunteers to help with community events.

Singular nouns = a/an

- Bring an umbrella if it looks like rain.

- You’ll need a visa to stay for more than ninety days.

Note: We use many different expressions for an indefinite quantity of plural or non-count nouns. Words like “some,” “several,” and “many” use no article (e.g., We need some volunteers to help this afternoon. We really need several people at 3:00.) One exception: “a few” + plural noun (We need a few people at 3:00.) In certain situations, we always use “a” or “an.” These situations include:

- Referring to something that is one of a number of possible things. Example: My lab is planning to purchase a new microscope. (Have you chosen one yet? No, we’re still looking at a number of different models.)

- Referring to one specific part of a larger quantity. Example: Can I have a bowl of cereal and a slice of toast? (Don’t you want the whole box of cereal and the whole loaf of bread? No, thanks. Just a bowl and a slice will be fine.)

- With certain indefinite quantifiers. Example: We met a lot of interesting people last night. (You can also say “a bunch of” or “a ton of” when you want to be vague about the exact quantity. Note that these expressions are all phrases: a + quantifier + of.)

- Exception: “A few of” does not fit this category. See Number 8 in the next section for the correct usage of this expression.

- Specifying information associated with each item of a grouping. Example: My attorney asked for $200 an hour, but I’ll offer him $200 a week instead. (In this case, “a” can substitute for the word “per.”)

- Introducing a noun to the reader for the first time (also called “first mention”). Use “the” for each subsequent reference to that noun if you mean “this one exactly.” Example: I presented a paper last month, and my advisor wants me to turn the paper into an article. If I can get the article written this semester, I can take a break after that! I really need a break!

Note: The writer does not change from “a break” to “the break” with the second mention because she is not referring to one break in particular (“this break exactly”). It’s indefinite—any break will be fine!!

When you mean “this one exactly”

Talking about “this one exactly” is also called “definite reference.” We use it when both the reader and the writer can identify the exact noun that is being referred to. When you mean “this one exactly,” you have two article choices: Ø, the. The choice of article depends on the noun and on the context. Ask yourself, “What kind of noun is it?”

(Most) Proper nouns = no article (Ø)

- My research will be conducted in Luxembourg.

- Dr. Homer inspired my interest in Ontario.

Note: Some proper nouns do require “the.” See the special notes on nouns below.

Non-count nouns = the

- Step two: mix the water with the boric acid.

- The laughter of my children is contagious.

Plural nouns = the

- We recruited the nurses from General Hospital.

- The projects described in your proposal will be fully funded.

- Bring the umbrella in my closet if it looks like rain.

- Did you get the visa you applied for?

In certain situations, we always use “the” because the noun or the context makes it clear that we’re talking about “this one exactly.” The context might include the words surrounding the noun or the context of knowledge that people share. Examples of these situations include:

Unique nouns

- The earth rotates around the sun.

- The future looks bright!

Shared knowledge (both participants know what’s being referred to, so it’s not necessary to specify with any more details)

- The boss just asked about the report.

- Meet me in the parking lot after the show.

Second mention (with explicit first mention)

- I found a good handout on English articles. The handout is available online.

- You can get a giant ice cream cone downtown. If you can eat the cone in five seconds, you get another one free.

Second mention (with implied first mention—this one is very, very common)

- Dr. Frankenstein performed a complicated surgery. He said the patient is recovering nicely. (“The patient” is implied by “surgery”—every surgery has a patient.)

- My new shredder works fabulously! The paper is completely destroyed. (Again, “the paper” is implied by “shredder.”)

Ordinals and superlatives (first, next, primary, most, best, least, etc.)

- The first man to set foot on the moon…

- The greatest advances in medicine…

Specifiers (sole, only, principle, etc.)

- The sole purpose of our organization is…

- The only fact we need to consider is…

Restricters (words, phrases, or clauses that restrict the noun to one definite meaning)

- Study the chapter on osmosis for the test tomorrow.

- Also study the notes you took at the lecture that Dr. Science gave yesterday.

Plural nouns in partitive -of phrases (phrases that indicate parts of a larger whole) (Note: Treat “of the” as a chunk in these phrases—both words in or both words out)

- Most of the international students have met their advisors, but a few of them have appointments next week. (emphasis on part of the group, and more definite reference to a specific group of international students, like the international students at UNC)

- Most international students take advantage of academic advising during their college careers. (emphasis on the group as a whole, and more generic reference to international students everywhere)

- Several of the risk factors should be considered carefully, but the others are only minor concerns. (emphasis on part of the group)

- Several risk factors need to be considered carefully before we proceed with the project. (emphasis on the group as a whole)

- A few of the examples were hard to understand, but the others were very clear. (emphasis on part of the group)

- A few examples may help illustrate the situation clearly. (emphasis on the group as a whole)

Note: “Few examples” is different from “a few examples.” Compare:

- The teacher gave a few good examples. (a = emphasizes the presence of good examples)

- The teacher gave few good examples. (no article = emphasizes the lack of good examples)

Article flowchart

For the more visually oriented, this flowchart sketches out the basic rules and basic questions.

Some notes about nouns

Uncountable nouns.

As the name suggests, uncountable nouns (also called non-count or mass nouns) are things that can not be counted. They use no article for generic and indefinite reference, and use “the” for definite reference. Uncountable nouns fall into several categories:

- Abstractions: laughter, information, beauty, love, work, knowledge

- Fields of study: biology, medicine, history, civics, politics (some end in -s but are non-count)

- Recreational activities: football, camping, soccer, dancing (these words often end in -ing)

- Natural phenomena: weather, rain, sunshine, fog, snow (but events are countable: a hurricane, a blizzard, a tornado)

- Whole groups of similar/identical objects: furniture, luggage, food, money, cash, clothes

- Liquids, gases, solids, and minerals: water, air, gasoline, coffee, wood, iron, lead, boric acid

- Powders and granules: rice, sand, dust, calcium carbonate

- Diseases: cancer, diabetes, schizophrenia (but traumas are countable: a stroke, a heart attack, etc.)

Note: Different languages might classify nouns differently

- “Research” and “information” are good examples of nouns that are non-count in American English but countable in other languages and other varieties of English.

Strategy: Check a dictionary. A learner’s dictionary will indicate whether the noun is countable or not. A regular dictionary will give a plural form if the noun is countable. Note: Some nouns have both count and non-count meanings Some nouns have both count and non-count meanings in everyday usage. Some non-count nouns have count meanings only for specialists in a particular field who consider distinct varieties of something that an average person would not differentiate. Non-count meanings follow the rules for non-count nouns (generic and indefinite reference: no article; definite: “the”); count meanings follow the count rules (a/an for singular, no article for plural). Can you see the difference between these examples?

- John’s performance on all three exams was exceptional.

- John’s performances of Shakespeare were exceptional.

- To be well educated, you need good instruction.

- To assemble a complicated machine, you need good instructions.

Proper nouns

Proper nouns (names of people, places, religions, languages, etc.) are always definite. They take either “the” or no article. Use “the” for regions (like the Arctic) and for a place that’s made up of a collection of smaller parts (like a collection of islands, mountains, lakes, etc.). Examples:

- Places (singular, no article): Lake Erie, Paris, Zimbabwe, Mount Rushmore

- Places (collective, regional, “the”): the Great Lakes, the Middle East, the Caribbean

Note: Proper nouns in theory names may or may not take articles When a person’s name is part of a theory, device, principle, law, etc., use “the” when the name does not have a possessive apostrophe. Do not use “the” when the name has an apostrophe. Examples:

Note: Articles change when proper nouns function as adjectives Notice how the article changes with “Great Lakes” in the examples below. When place names are used as adjectives, follow the article rule for the noun they are modifying. Examples: I’m studying …

- …the Great Lakes. (as noun)

- …a Great Lakes shipwreck.(as adjective with “one of many” singular noun)

- …the newest Great Lakes museum. (as adjective with “this one exactly” singular noun)

- …Great Lakes shipping policies. (as adjective with “one of many” plural noun)

- …Great Lakes history. (as adjective with “one of many” uncountable noun)

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Byrd, Patricia, and Beverly Benson. 1993. Problem/Solution: A Reference for ESL Writers . Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Celce-Murcia, Marianne, and Diane Larsen-Freeman. 2015. The Grammar Book: An ESL/EFL Teacher’s Course , 3rd ed. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Swales, John, and Christine B. Feak. 2012. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Tasks and Skills , 3rd ed. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

The Difference between an Essay and an Article

Imagine opening your favorite entertainment magazine or your local newspaper and finding a collection of essays. How long, in that case, would the money you spend on magazines and newspapers be considered part of your entertainment budget?

Articles can be informative and not all of them are entertaining. However, it's more likely to find articles in magazines that offer entertainment for readers than an essay.

The most notable difference between an essay and an article is the tone. Essays traditionally are subjective pieces of formal writing that offers an analysis of a specific topic. In other words, an essay writer studies, researches, and forms a factually-based opinion on the topic in order to inform others about their ideas.

An article is traditionally objective instead of subjective. Writing an article doesn't always require that an opinion to be formed and expressed, and there's no requirement that an analysis be offered about the information being presented.

Scroll through a copy of Cosmopolitan, National Geographic, and today's edition of your local newspaper, and you'll get a sense of how articles can be structured in numerous different ways. Some include headings and subheadings along with accompanying photos to paint a picture for the reader to form their own thoughts and opinions about the subject of an article.

Essays, however, have more strict guidelines on structure depending on which type of essay a writer has chosen. Traditionally, readers will see an introductory paragraph that presents a thesis statement, body paragraphs with topic sentences that relate back to and flesh out the thesis, and a conclusion with the author's take on the information presented.

Entertainment Factor

While narrative essays can tell entertaining stories, it is articles that are most often included in magazines and newspapers to keep their subscribers informed and reading.

It's up to the writer of an article what message they want to convey. Sometimes that message is informative and sometimes it's humorous. For an essay writer, it's all about learning as much as possible about a topic, forming an opinion, and describing how they came to that opinion and why.

You're not likely to find essays in entertainment magazines. A person seeking in-depth information on a subject is going to seek out an essay, while a person looking for an entertaining piece of writing that allows them to draw their own conclusions will be more likely to seek out an article.

- Written By Gregg Rosenzweig

- Updated: November 8, 2023

We’re here to help you choose the most appropriate content types to fulfill your content strategy. In this series, we’re breaking down the most popular content types to their most basic fundamentals — simple definitions, clarity on formats, and plenty of examples — so you can start with a solid foundation.

What is an article?

An article is a piece of writing that educates, informs and/or colorfully illustrates a topic using purpose-driven writing, provocative insights and a unique perspective designed to engage an audience.

Articles also can be…

- Branded/native content

- Content ladders

- Press releases

- Thought-leadership pieces

- Skyscrapers

The long and short of it

Depending on the outlet and channel you’re publishing in, article lengths will vary . However, as with any writing, you should never write one word more than is necessary to tell your story.

A general guide to article length:

- Short Form (500 words or less)

- Standard (500-1,500 words)

- Long Form (1,500-2,500 words)

- Extra Long Form (2,500+ words)

What can articles do for a business?

Different from advertising, articles allow you to expand on a topic and/or show expertise in your industry or niche, whether an editorial piece or a how-to template . They also afford you an opportunity to enlighten your audience on a deeper level.

Popular use-case examples for articles

Ads only get you so far. If you want to have a conversation with your audience, an article can inspire interactions with a reader, drive traffic to a page, and ultimately convert customers.

- Content for social media channels with viral potential (FB, Twitter, and LinkedIn)

- Content for a company blog and to establish a content cadence

- Thought-leadership pieces that establish instant credibility in a given area

Reasons to write articles

- To inspire inbound marketing and allow you to hit your KPIs

- To expand brand awareness, build loyalty and advocacy

- To boost SEO and “page ranking” through the use of keywords and backlinks

Business types:

Whether you’re a pest control company or hotel chain, there’s always a story to tell. Literally any business, regardless of sector, can use articles to build a greater customer base.

Article examples – short form

Article examples – standard form

Article examples – long form

Article examples – extra long form

Article examples – listicles

Article examples – how-to’s

Article examples – interviews

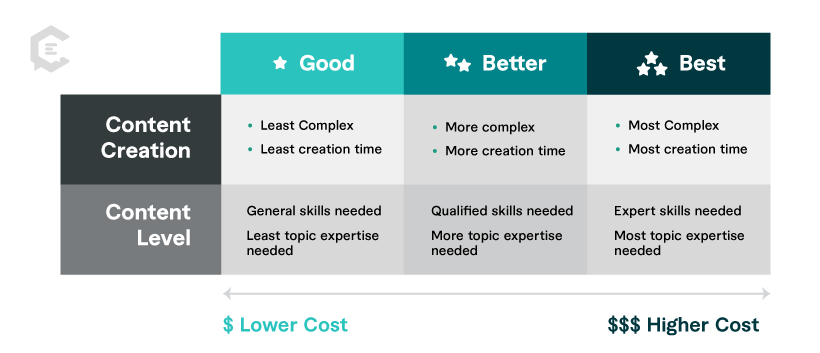

Understanding content quality in examples

Our team has rated content type examples in three degrees of quality ( Good, Better, Best ) to help you better gauge resources needed for your content plan. In general, the degrees of content quality correspond to our three content levels ( General, Qualified, Expert ) based on the criteria below. Please consider there are multiple variables that could determine the cost, completion time, or content level for any content piece with a perceived degree of quality.

More content types with examples:

- What Is an Article?

- What Is an Ebook?

- What Is a White Paper?

- What Is a Customer Story?

- What Is a Product Description?

- What Is an Infographic?

- What Is a Presentation?

- What Is a Motion Graphic?

- What Is an Animated Video?

Need help writing engaging, SEO-friendly articles? Talk to a content specialist at ClearVoice today. Our talented team of writers can easily handle all your content needs, freeing up your team’s time to focus on other parts of your business.

Stay in the know.

We will keep you up-to-date with all the content marketing news and resources. You will be a content expert in no time. Sign up for our free newsletter.

Elevate Your Content Game

Transform your marketing with a consistent stream of high-quality content for your brand.

You May Also Like...

Mastering the Content Audit: ClearVoice Marketing’s Comprehensive Process Revealed

Measuring What Matters in Your Collaborative Content Approach

Amplifying Your Content Strategy: Harnessing User Feedback for Effective Content Audits

- Content Production

- Build Your SEO

- Amplify Your Content

- For Agencies

Why ClearVoice

- Talent Network

- How It Works

- Freelance For Us

- Statement on AI

- Talk to a Specialist

Get Insights In Your Inbox

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Intellectual Property Claims

- Data Collection Preferences

What is an Essay?

10 May, 2020

11 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Well, beyond a jumble of words usually around 2,000 words or so - what is an essay, exactly? Whether you’re taking English, sociology, history, biology, art, or a speech class, it’s likely you’ll have to write an essay or two. So how is an essay different than a research paper or a review? Let’s find out!

Defining the Term – What is an Essay?

The essay is a written piece that is designed to present an idea, propose an argument, express the emotion or initiate debate. It is a tool that is used to present writer’s ideas in a non-fictional way. Multiple applications of this type of writing go way beyond, providing political manifestos and art criticism as well as personal observations and reflections of the author.

An essay can be as short as 500 words, it can also be 5000 words or more. However, most essays fall somewhere around 1000 to 3000 words ; this word range provides the writer enough space to thoroughly develop an argument and work to convince the reader of the author’s perspective regarding a particular issue. The topics of essays are boundless: they can range from the best form of government to the benefits of eating peppermint leaves daily. As a professional provider of custom writing, our service has helped thousands of customers to turn in essays in various forms and disciplines.

Origins of the Essay

Over the course of more than six centuries essays were used to question assumptions, argue trivial opinions and to initiate global discussions. Let’s have a closer look into historical progress and various applications of this literary phenomenon to find out exactly what it is.

Today’s modern word “essay” can trace its roots back to the French “essayer” which translates closely to mean “to attempt” . This is an apt name for this writing form because the essay’s ultimate purpose is to attempt to convince the audience of something. An essay’s topic can range broadly and include everything from the best of Shakespeare’s plays to the joys of April.

The essay comes in many shapes and sizes; it can focus on a personal experience or a purely academic exploration of a topic. Essays are classified as a subjective writing form because while they include expository elements, they can rely on personal narratives to support the writer’s viewpoint. The essay genre includes a diverse array of academic writings ranging from literary criticism to meditations on the natural world. Most typically, the essay exists as a shorter writing form; essays are rarely the length of a novel. However, several historic examples, such as John Locke’s seminal work “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” just shows that a well-organized essay can be as long as a novel.

The Essay in Literature

The essay enjoys a long and renowned history in literature. They first began gaining in popularity in the early 16 th century, and their popularity has continued today both with original writers and ghost writers. Many readers prefer this short form in which the writer seems to speak directly to the reader, presenting a particular claim and working to defend it through a variety of means. Not sure if you’ve ever read a great essay? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces of literature are actually nothing less than essays, or evolved into more complex structures from the essay. Check out this list of literary favorites:

- The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

- Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag

- High-Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now and Never by Barbara Kingsolver

- Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion

- Naked by David Sedaris

- Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau

Pretty much as long as writers have had something to say, they’ve created essays to communicate their viewpoint on pretty much any topic you can think of!

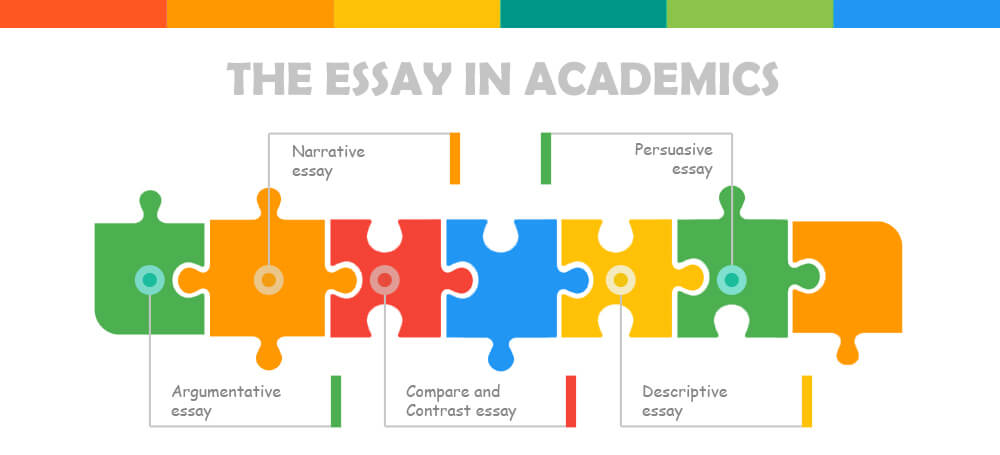

The Essay in Academics

Not only are students required to read a variety of essays during their academic education, but they will likely be required to write several different kinds of essays throughout their scholastic career. Don’t love to write? Then consider working with a ghost essay writer ! While all essays require an introduction, body paragraphs in support of the argumentative thesis statement, and a conclusion, academic essays can take several different formats in the way they approach a topic. Common essays required in high school, college, and post-graduate classes include:

Five paragraph essay

This is the most common type of a formal essay. The type of paper that students are usually exposed to when they first hear about the concept of the essay itself. It follows easy outline structure – an opening introduction paragraph; three body paragraphs to expand the thesis; and conclusion to sum it up.

Argumentative essay

These essays are commonly assigned to explore a controversial issue. The goal is to identify the major positions on either side and work to support the side the writer agrees with while refuting the opposing side’s potential arguments.

Compare and Contrast essay

This essay compares two items, such as two poems, and works to identify similarities and differences, discussing the strength and weaknesses of each. This essay can focus on more than just two items, however. The point of this essay is to reveal new connections the reader may not have considered previously.

Definition essay

This essay has a sole purpose – defining a term or a concept in as much detail as possible. Sounds pretty simple, right? Well, not quite. The most important part of the process is picking up the word. Before zooming it up under the microscope, make sure to choose something roomy so you can define it under multiple angles. The definition essay outline will reflect those angles and scopes.

Descriptive essay

Perhaps the most fun to write, this essay focuses on describing its subject using all five of the senses. The writer aims to fully describe the topic; for example, a descriptive essay could aim to describe the ocean to someone who’s never seen it or the job of a teacher. Descriptive essays rely heavily on detail and the paragraphs can be organized by sense.

Illustration essay

The purpose of this essay is to describe an idea, occasion or a concept with the help of clear and vocal examples. “Illustration” itself is handled in the body paragraphs section. Each of the statements, presented in the essay needs to be supported with several examples. Illustration essay helps the author to connect with his audience by breaking the barriers with real-life examples – clear and indisputable.

Informative Essay

Being one the basic essay types, the informative essay is as easy as it sounds from a technical standpoint. High school is where students usually encounter with informative essay first time. The purpose of this paper is to describe an idea, concept or any other abstract subject with the help of proper research and a generous amount of storytelling.

Narrative essay

This type of essay focuses on describing a certain event or experience, most often chronologically. It could be a historic event or an ordinary day or month in a regular person’s life. Narrative essay proclaims a free approach to writing it, therefore it does not always require conventional attributes, like the outline. The narrative itself typically unfolds through a personal lens, and is thus considered to be a subjective form of writing.

Persuasive essay

The purpose of the persuasive essay is to provide the audience with a 360-view on the concept idea or certain topic – to persuade the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. The viewpoints can range widely from why visiting the dentist is important to why dogs make the best pets to why blue is the best color. Strong, persuasive language is a defining characteristic of this essay type.

The Essay in Art

Several other artistic mediums have adopted the essay as a means of communicating with their audience. In the visual arts, such as painting or sculpting, the rough sketches of the final product are sometimes deemed essays. Likewise, directors may opt to create a film essay which is similar to a documentary in that it offers a personal reflection on a relevant issue. Finally, photographers often create photographic essays in which they use a series of photographs to tell a story, similar to a narrative or a descriptive essay.

Drawing the line – question answered

“What is an Essay?” is quite a polarizing question. On one hand, it can easily be answered in a couple of words. On the other, it is surely the most profound and self-established type of content there ever was. Going back through the history of the last five-six centuries helps us understand where did it come from and how it is being applied ever since.

If you must write an essay, follow these five important steps to works towards earning the “A” you want:

- Understand and review the kind of essay you must write

- Brainstorm your argument

- Find research from reliable sources to support your perspective

- Cite all sources parenthetically within the paper and on the Works Cited page

- Follow all grammatical rules

Generally speaking, when you must write any type of essay, start sooner rather than later! Don’t procrastinate – give yourself time to develop your perspective and work on crafting a unique and original approach to the topic. Remember: it’s always a good idea to have another set of eyes (or three) look over your essay before handing in the final draft to your teacher or professor. Don’t trust your fellow classmates? Consider hiring an editor or a ghostwriter to help out!

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to get help. HandMadeWriting is the perfect answer to the question “Who can write my essay?”

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

An NPR editor who wrote a critical essay on the company has resigned after being suspended

FILE - The headquarters for National Public Radio (NPR) stands on North Capitol Street on April 15, 2013, in Washington. A National Public Radio editor who wrote an essay criticizing his employer for promoting liberal reviews resigned on Wednesday, April 17, 2024, a day after it was revealed that he had been suspended. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak, File)

- Copy Link copied

NEW YORK (AP) — A National Public Radio editor who wrote an essay criticizing his employer for promoting liberal views resigned on Wednesday, attacking NPR’s new CEO on the way out.

Uri Berliner, a senior editor on NPR’s business desk, posted his resignation letter on X, formerly Twitter, a day after it was revealed that he had been suspended for five days for violating company rules about outside work done without permission.

“I cannot work in a newsroom where I am disparaged by a new CEO whose divisive views confirm the very problems” written about in his essay, Berliner said in his resignation letter.

Katherine Maher, a former tech executive appointed in January as NPR’s chief executive, has been criticized by conservative activists for social media messages that disparaged former President Donald Trump. The messages predated her hiring at NPR.

NPR’s public relations chief said the organization does not comment on individual personnel matters.

The suspension and subsequent resignation highlight the delicate balance that many U.S. news organizations and their editorial employees face. On one hand, as journalists striving to produce unbiased news, they’re not supposed to comment on contentious public issues; on the other, many journalists consider it their duty to critique their own organizations’ approaches to journalism when needed.

In his essay , written for the online Free Press site, Berliner said NPR is dominated by liberals and no longer has an open-minded spirit. He traced the change to coverage of Trump’s presidency.

“There’s an unspoken consensus about the stories we should pursue and how they should be framed,” he wrote. “It’s frictionless — one story after another about instances of supposed racism, transphobia, signs of the climate apocalypse, Israel doing something bad and the dire threat of Republican policies. It’s almost like an assembly line.”

He said he’d brought up his concerns internally and no changes had been made, making him “a visible wrong-thinker at a place I love.”

In the essay’s wake, NPR top editorial executive, Edith Chapin, said leadership strongly disagreed with Berliner’s assessment of the outlet’s journalism and the way it went about its work.

It’s not clear what Berliner was referring to when he talked about disparagement by Maher. In a lengthy memo to staff members last week, she wrote: “Asking a question about whether we’re living up to our mission should always be fair game: after all, journalism is nothing if not hard questions. Questioning whether our people are serving their mission with integrity, based on little more than the recognition of their identity, is profoundly disrespectful, hurtful and demeaning.”

Conservative activist Christopher Rufo revealed some of Maher’s past tweets after the essay was published. In one tweet, dated January 2018, Maher wrote that “Donald Trump is a racist.” A post just before the 2020 election pictured her in a Biden campaign hat.

In response, an NPR spokeswoman said Maher, years before she joined the radio network, was exercising her right to express herself. She is not involved in editorial decisions at NPR, the network said.

The issue is an example of what can happen when business executives, instead of journalists, are appointed to roles overseeing news organizations: they find themselves scrutinized for signs of bias in ways they hadn’t been before. Recently, NBC Universal News Group Chairman Cesar Conde has been criticized for service on paid corporate boards.

Maher is the former head of the Wikimedia Foundation. NPR’s own story about the 40-year-old executive’s appointment in January noted that she “has never worked directly in journalism or at a news organization.”

In his resignation letter, Berliner said that he did not support any efforts to strip NPR of public funding. “I respect the integrity of my colleagues and wish for NPR to thrive and do important journalism,” he wrote.

David Bauder writes about media for The Associated Press. Follow him at http://twitter.com/dbauder

Freedom for the Wolves

Neoliberal orthodoxy holds that economic freedom is the basis of every other kind. That orthodoxy, a Nobel economist says, is not only false; it is devouring itself.

A ny discussion of freedom must begin with a discussion of whose freedom we’re talking about. The freedom of some to harm others, or the freedom of others not to be harmed? Too often, we have not balanced the equation well: gun owners versus victims of gun violence; chemical companies versus the millions who suffer from toxic pollution; monopolistic drug companies versus patients who die or whose health worsens because they can’t afford to buy medicine.

Understanding the meaning of freedom is central to creating an economic and political system that delivers not only on efficiency, equity, and sustainability but also on moral values. Freedom—understood as having inherent ties to notions of equity, justice, and well-being—is itself a central value. And it is this broad notion of freedom that has been given short shrift by powerful strands in modern economic thinking—notably the one that goes by the shorthand term neoliberalism , the belief that the freedom that matters most, and from which other freedoms indeed flow, is the freedom of unregulated, unfettered markets.

F. A. Hayek and Milton Friedman were the most notable 20th-century defenders of unrestrained capitalism. The idea of “unfettered markets”—markets without rules and regulations—is an oxymoron because without rules and regulations enforced by government, there could and would be little trade. Cheating would be rampant, trust low. A world without restraints would be a jungle in which only power mattered, determining who got what and who did what. It wouldn’t be a market at all.

Nonetheless, Hayek and Friedman argued that capitalism as they interpreted it, with free and unfettered markets, was the best system in terms of efficiency, and that without free markets and free enterprise, we could not and would not have individual freedom. They believed that markets on their own would somehow remain competitive. Remarkably, they had already forgotten—or ignored—the experiences of monopolization and concentration of economic power that had led to the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890) and the Clayton Antitrust Act (1914). As government intervention grew in response to the Great Depression, Hayek worried that we were on “the road to serfdom,” as he put it in his 1944 book of that title; that is, on the road to a society in which individuals would become subservient to the state.

Rogé Karma: Why America abandoned the greatest economy in history

My own conclusions have been radically different. It was because of democratic demands that democratic governments, such as that of the U.S., responded to the Great Depression through collective action. The failure of governments to respond adequately to soaring unemployment in Germany led to the rise of Hitler. Today, it is neoliberalism that has brought massive inequalities and provided fertile ground for dangerous populists. Neoliberalism’s grim record includes freeing financial markets to precipitate the largest financial crisis in three-quarters of a century, freeing international trade to accelerate deindustrialization, and freeing corporations to exploit consumers, workers, and the environment alike. Contrary to what Friedman suggested in his 1962 book, Capitalism and Freedom , this form of capitalism does not enhance freedom in our society. Instead, it has led to the freedom of a few at the expense of the many. As Isaiah Berlin would have it: Freedom for the wolves; death for the sheep.

I t is remarkable that , in spite of all the failures and inequities of the current system, so many people still champion the idea of an unfettered free-market economy. This despite the daily frustrations of dealing with health-care companies, insurance companies, credit-card companies, telephone companies, landlords, airlines, and every other manifestation of modern society. When there’s a problem, ordinary citizens are told by prominent voices to “leave it to the market.” They’ve even been told that the market can solve problems that one might have thought would require society-wide action and coordination, some larger sense of the public good, and some measure of compulsion. It’s purely wishful thinking. And it’s only one side of the fairy tale. The other side is that the market is efficient and wise, and that government is inefficient and rapacious.

Mindsets, once created, are hard to change. Many Americans still think of the United States as a land of opportunity. They still believe in something called the American dream, even though for decades the statistics have painted a darker picture. The rate of absolute income mobility—that is, the percentage of children who earn more than their parents—has been declining steadily since the Second World War. Of course, America should aspire to be a land of opportunity, but clinging to beliefs that are not supported by today’s realities—and that hold that markets by themselves are a solution to today’s problems—is not helpful. Economic conditions bear this out, as more Americans are coming to understand. Unfettered markets have created, or helped create, many of the central problems we face, including manifold inequalities, the climate crisis, and the opioid crisis. And markets by themselves cannot solve any of our large, collective problems. They cannot manage the massive structural changes that we are going through—including global warming, artificial intelligence, and the realignment of geopolitics.

All of these issues present inconvenient truths to the free-market mindset. If externalities such as these are important, then collective action is important. But how to come to collective agreement about the regulations that govern society? Small communities can sometimes achieve a broad consensus, though typically far from unanimity. Larger societies have a harder go of it. Many of the crucial values and presumptions at play are what economists, philosophers, and mathematicians refer to as “primitives”—underlying assumptions that, although they can be debated, cannot be resolved. In America today we are divided over such assumptions, and the divisions have widened.

The consequences of neoliberalism point to part of the reason: specifically, growing income and wealth disparities and the polarization caused by the media. In theory, economic freedom was supposed to be the bedrock basis for political freedom and democratic health. The opposite has proved to be true. The rich and the elites have a disproportionate voice in shaping both government policies and societal narratives. All of which leads to an enhanced sense by those who are not wealthy that the system is rigged and unfair, which makes healing divisions all the more difficult.

Chris Murphy: The wreckage of neoliberalism

As income inequalities grow, people wind up living in different worlds. They don’t interact. A large body of evidence shows that economic segregation is widening and has consequences, for instance, with regard to how each side thinks and feels about the other. The poorest members of society see the world as stacked against them and give up on their aspirations; the wealthiest develop a sense of entitlement, and their wealth helps ensure that the system stays as it is.

The media, including social media, provide another source of division. More and more in the hands of a very few, the media have immense power to shape societal narratives and have played an obvious role in polarization. The business model of much of the media entails stoking divides. Fox News, for instance, discovered that it was better to have a devoted right-wing audience that watched only Fox than to have a broader audience attracted to more balanced reporting. Social-media companies have discovered that it’s profitable to get engagement through enragement. Social-media sites can develop their algorithms to effectively refine whom to target even if that means providing different information to different users.

N eoliberal theorists and their beneficiaries may be happy to live with all this. They are doing very well by it. They forget that, for all the rhetoric, free markets can’t function without strong democracies beneath them—the kind of democracies that neoliberalism puts under threat. In a very direct way, neoliberal capitalism is devouring itself.

Not only are neoliberal economies inefficient at dealing with collective issues, but neoliberalism as an economic system is not sustainable on its own. To take one fundamental element: A market economy runs on trust. Adam Smith himself emphasized the importance of trust, recognizing that society couldn’t survive if people brazenly followed their own self-interest rather than good codes of conduct:

The regard to those general rules of conduct, is what is properly called a sense of duty, a principle of the greatest consequence in human life, and the only principle by which the bulk of mankind are capable of directing their actions … Upon the tolerable observance of these duties, depends the very existence of human society, which would crumble into nothing if mankind were not generally impressed with a reverence for those important rules of conduct.

For instance, contracts have to be honored. The cost of enforcing every single contract through the courts would be unbearable. And with no trust in the future, why would anybody save or invest? The incentives of neoliberal capitalism focus on self-interest and material well-being, and have done much to weaken trust. Without adequate regulation, too many people, in the pursuit of their own self-interest, will conduct themselves in an untrustworthy way, sliding to the edge of what is legal, overstepping the bounds of what is moral. Neoliberalism helps create selfish and untrustworthy people. A “businessman” like Donald Trump can flourish for years, even decades, taking advantage of others. If Trump were the norm rather than the exception, commerce and industry would grind to a halt.

We also need regulations and laws to make sure that there are no concentrations of economic power. Business seeks to collude and would do so even more in the absence of antitrust laws. But even playing within current guardrails, there’s a strong tendency for the agglomeration of power. The neoliberal ideal of free, competitive markets would, without government intervention, be evanescent.

We’ve also seen that those with power too often do whatever they can to maintain it. They write the rules to sustain and enhance power, not to curb or diminish it. Competition laws are eviscerated. Enforcement of banking and environmental laws is weakened. In this world of neoliberal capitalism, wealth and power are ever ascendant.

Neoliberalism undermines the sustainability of democracy—the opposite of what Hayek and Friedman intended or claimed. We have created a vicious circle of economic and political inequality, one that locks in more freedom for the rich and leaves less for the poor, at least in the United States, where money plays such a large role in politics.

Read: When Milton Friedman ran the show

There are many ways in which economic power gets translated into political power and undermines the fundamental democratic value of one person casting one vote. The reality is that some people’s voices are much louder than others. In some countries, accruing power is as crude as literally buying votes, with the wealthy having more money to buy more votes. In advanced countries, the wealthy use their influence in the media and elsewhere to create self-serving narratives that in turn become the conventional wisdom. For instance, certain rules and regulations and government interventions—tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans, deregulation of key industries—that are purely in the interest of the rich and powerful are also, it is said, in the national interest. Too often that viewpoint is swallowed wholesale. If persuasion doesn’t work, there is always fear: If the banks are not bailed out, the economic system will collapse, and everyone will be worse off. If the corporate tax rate is not cut, firms will leave and go to other jurisdictions that are more business-friendly.

Is a free society one in which a few dictate the terms of engagement? In which a few control the major media and use that control to decide what the populace sees and hears? We now inhabit a polarized world in which different groups live in different universes, disagreeing not only on values but on facts.

A strong democracy can’t be sustained by neoliberal economics for a further reason. Neoliberalism has given rise to enormous “rents”—the monopoly profits that are a major source of today’s inequalities. Much is at stake, especially for many in the top one percent, centered on the enormous accretion of wealth that the system has allowed. Democracy requires compromise if it is to remain functional, but compromise is difficult when there is so much at stake in terms of both economic and political power.

A free-market, competitive, neoliberal economy combined with a liberal democracy does not constitute a stable equilibrium—not without strong guardrails and a broad societal consensus on the need to curb wealth inequality and money’s role in politics. The guardrails come in many forms, such as competition policy, to prevent the creation, maintenance, and abuse of market power. We need checks and balances, not just within government, as every schoolchild in the U.S. learns, but more broadly within society. Strong democracy, with widespread participation, is also part of what is required, which means working to strike down laws intended to decrease democratic participation or to gerrymander districts where politicians will never lose their seats.

Whether America’s political and economic system today has enough safeguards to sustain economic and political freedoms is open to serious question.

U nder the very name of freedom, neoliberals and their allies on the radical right have advocated policies that restrict the opportunities and freedoms, both political and economic, of the many in favor of the few. All these failures have hurt large numbers of people around the world, many of whom have responded by turning to populism, drawn to authoritarian figures like Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, Vladimir Putin, and Narendra Modi.

Perhaps we should not be surprised by where the U.S. has landed. It is a country now so divided that even a peaceful transition of power is difficult, where life expectancy is the lowest among advanced nations, and where we can’t agree about truth or how it might best be ascertained or verified. Conspiracy theories abound. The values of the Enlightenment have to be relitigated daily.

There are good reasons to worry whether America’s form of ersatz capitalism and flawed democracy is sustainable. The incongruities between lofty ideals and stark realities are too great. It’s a political system that claims to cherish freedom above all else but in many ways is structured to deny or restrict freedoms for many of its citizens.

I do believe that there is broad consensus on key elements of what constitutes a good and decent society, and on what kind of economic system supports that society. A good society, for instance, must live in harmony with nature. Our current capitalism has made a mess of this. A good society allows individuals to flourish and live up to their potential. In terms of education alone, our current capitalism is failing large portions of the population. A good economic system would encourage people to be honest and empathetic, and foster the ability to cooperate with others. The current capitalist system encourages the antithesis.

But the key first step is changing our mindset. Friedman and Hayek argued that economic and political freedoms are intimately connected, with the former necessary for the latter. But the economic system that has evolved—largely under the influence of these thinkers and others like them—undermines meaningful democracy and political freedom. In the end, it will undermine the very neoliberalism that has served them so well.

For a long time, the right has tried to establish a monopoly over the invocation of freedom , almost as a trademark. It’s time to reclaim the word.

This article has been adapted from Joseph E. Stiglitz’s new book, The Road to Freedom: Economics and the Good Society .

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Support for this project was provided by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Being Stuck in a Courtroom Is Just What Trump Needed

By Stuart Stevens

Mr. Stevens is a former Republican political consultant who has worked on many campaigns for federal and state office, including the presidential campaigns of George W. Bush and Mitt Romney.

For the next several weeks, the presumptive Republican nominee for president will be spending his days in a New York City courthouse. By any normal campaign standard, taking your candidate off the road for much of April and May of a presidential year would be devastating. But “normal” and Donald Trump live in different countries. The trial will afford Mr. Trump the opportunity to define the essence of his candidacy: I am a victim.

The very competent operatives running the Trump campaign didn’t draw this up as their ideal campaign plan, but they will appreciate its potential. The Manhattan courtroom will be the setting for Mr. Trump to play the role of a familiar American archetype: the wronged man seeking justice from corrupt, powerful forces. The former president is good in this role, and that’s no small thing.

Presidential campaigns pay a great deal of attention to scheduling — where, when and how many events should a candidate do on any given day. But here’s the most important element of scheduling: putting a candidate in a setting that provides a chance to excel. In George W. Bush’s 2000 presidential campaign, our default event was to put him at a school, preferably one not in a wealthy ZIP code. Education was his signature issue as governor of Texas. He knew a lot about it and cared about it passionately, and the odds were it would be a successful event. It was not surprising to me that when planes struck the twin towers, President Bush was in an elementary school reading to students.

Mr. Trump loves big rallies. He feeds off the crowd like a vampire at a blood bank. But his act is getting a little old. Cable news no longer cuts live to these invariably repetitive events, and they don’t seem to drive as much conversation among voters as they once did. By contrast, the trial gives Mr. Trump the benefits of renewed interest from voters and the media with no burden on his team to increase campaigning or produce a newsworthy event.

I feel like I have spent half my life in campaign headquarters, staring at a map and a calendar. The map is always too large, and the calendar too short. Time is the one resource allocated to campaigns in exactly the same amounts. But there’s a dirty little secret to presidential campaigns: Where you campaign may be of little consequence. A courthouse could be as valuable as the swingiest swing district in the swingiest swing state.