The Paris Agreement: Annotated

Adopted by almost 200 parties at the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference, the Paris Agreement captures international ambitions for cooperative climate action.

The Paris Agreement on Climate was adopted in December 2015 at the twenty-first meeting of the Committee of the Parties (COP21), as part of a continuing international effort to mitigate climate change headed by the United Nations. The agreement was a successor to the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, which set specific targets, financial contributions, and monitoring and enforcement mechanisms to meet them. The Kyoto Protocol was seen by some large developed countries as harmful to their economies, and it raised complaints that other parties weren’t required to make sufficient reductions in emissions. The United States never ratified the treaty, and Canada announced its withdrawal in 2011.

In contrast, the Paris Agreement has been criticized for its lack of both country-specific goals for emission reduction and enforcement mechanisms. Instead it seeks to limit global temperature increase to below 2℃, and achieve zero greenhouse gas emissions at some point between the years 2030 and 2050.

In consideration of Earth Day , below is an annotation of the Introduction of the Agreement, with relevant scholarship covering the populations, economies, and governments affected by climate change. As always, the supporting research is free to read and download. If you see a small red letter J after a hyperlink—that looks like the one below, click it for free access to that content on JSTOR.

The red J indicates free access to JSTOR.

_____________________________________________

PARIS AGREEMENT

The Parties to this Agreement ,

Being Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change , hereinafter referred to as “the Convention,”

Pursuant to the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action established by decision 1/CP.17 of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention at its seventeenth session,

In pursuit of the objective of the Convention, and being guided by its principles, including the principle of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities , in the light of different national circumstances ,

Recognizing the need for an effective and progressive response to the urgent threat of climate change on the basis of the best available scientific knowledge,

Also recognizing the specific needs and special circumstances of developing country Parties, especially those that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change, as provided for in the Convention,

Taking full account of the specific needs and special situations of the least developed countries with regard to funding and transfer of technology,

Recognizing that Parties may be affected not only by climate change, but also by the impacts of the measures taken in response to it ,

Emphasizing the intrinsic relationship that climate change actions, responses and impacts have with equitable access to sustainable development and eradication of poverty ,

Recognizing the fundamental priority of safeguarding food security and ending hunger , and the particular vulnerabilities of food production systems to the adverse impacts of climate change ,

Taking into account the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities,

Acknowledging that climate change is a common concern of humankind, Parties should, when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health , the rights of indigenous peoples , local communities, migrants , children , persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the right to development, as well as gender equality , empowerment of women and intergenerational equity ,

Recognizing the importance of the conservation and enhancement, as appropriate, of sinks and reservoirs of the greenhouse gases referred to in the Convention,

Noting the importance of ensuring the integrity of all ecosystems, including oceans , and the protection of biodiversity , recognized by some cultures as Mother Earth, and noting the importance for some of the concept of “ climate justice ” when taking action to address climate change,

Affirming the importance of education, training, public awareness, public participation, public access to information and cooperation at all levels on the matters addressed in this Agreement,

Recognizing the importance of the engagements of all levels of government and various actors, in accordance with respective national legislations of Parties, in addressing climate change,

Also recognizing that sustainable lifestyles and sustainable patterns of consumption and production , with developed country Parties taking the lead , play an important role in addressing climate change,

Have agreed as follows :

[The full text of the Paris Agreement can be found at https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/ application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf .]

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- The Dangers of Animal Experimentation—for Doctors

Witnessing and Professing Climate Professionals

Crucial Building Blocks of Life on Earth Can More Easily Form in Outer Space

Making Implicit Racism

Recent posts.

- Zheng He, the Great Eunuch Admiral

- Fredric Wertham, Cartoon Villain

- Separated by a Common Language in Singapore

- Katherine Mansfield and Anton Chekhov

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

What is the Paris Agreement? Everything you need to know

The Paris Agreement came into effect in November 2016, after 55 countries representing at least 55% of global emissions signed up. Image: REUTERS/Susana Vera

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Douglas Broom

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Future of the Environment is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- The Paris Agreement is the global plan to keep temperature increases well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

- At COP26, Article 6 of the Paris Agreement was approved.

- Ahead of COP27 , global attention has once more turned to efforts to tackle climate change.

This article was updated on 25 October 2022.

Ahead of COP27, the world's focus has turned firmly to global efforts to tackle climate change. One of the cornerstones of that effort is the Paris Agreement.

But what is it and who's signed up to the Agreement?

Have you read?

How our responses to climate change and the coronavirus are linked, why climate change increases gender inequality, cop27: why it matters and 5 key areas for action, what is the paris agreement.

Climate change is one of the biggest challenges facing the world today. It is responsible for the increase in extreme weather events , as well as an unbroken series of hottest years on record. Indeed, environmental concerns and the threat posed by climate change have been a consistent feature of the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report .

World leaders spent two weeks in Paris during December 2015 hammering out the final wording of an agreement to keep global temperature increases well below 2°C – and if possible 1.5°C – compared with pre-industrial levels.

It was adopted by 196 Parties at COP21 and came into force on 4 November 2016.

This can only be achieved through a significant reduction in emissions of greenhouse gases. Known as COP21 (the 21st Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change), it was one of the largest gatherings of world leaders ever seen.

Everyone who attended COP21 made emission-cutting pledges. These are known as “intended nationally determined contributions”, or INDCs for short.

China's target is to reach peak CO2 emissions by 2030 at the latest, and to lower the carbon intensity of its GDP by 60-65% from 2005 levels by the same date.

The EU plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels, while the US aims to cut greenhouse gas pollution by 50-52% by 2030 from 2005, and to reach net zero by 2050 .

Climate change poses an urgent threat demanding decisive action. Communities around the world are already experiencing increased climate impacts, from droughts to floods to rising seas. The World Economic Forum's Global Risks Report continues to rank these environmental threats at the top of the list.

To limit global temperature rise to well below 2°C and as close as possible to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, it is essential that businesses, policy-makers, and civil society advance comprehensive near- and long-term climate actions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

The World Economic Forum's Climate Initiative supports the scaling and acceleration of global climate action through public and private-sector collaboration. The Initiative works across several workstreams to develop and implement inclusive and ambitious solutions.

This includes the Alliance of CEO Climate Leaders, a global network of business leaders from various industries developing cost-effective solutions to transitioning to a low-carbon, climate-resilient economy. CEOs use their position and influence with policy-makers and corporate partners to accelerate the transition and realize the economic benefits of delivering a safer climate.

Contact us to get involved.

When did it come into force?

The Paris Agreement came into effect on 4 November 2016 , after its minimum threshold was met – 55 countries representing at least 55% of global emissions.

For countries that join after this point, the Agreement comes into force 30 days after that country "deposits its instrument of ratification, acceptance, approval or accession with the Secretary-General".

The most recent scheduled gathering of the parties – COP26 – took place in Glasgow last year. One of the key outcomes of that meeting was the approval of Article 6, the Paris Agreement's guidelines for carbon markets . It allows countries to voluntarily cooperate with each other to achieve their emission reduction targets.

The next gathering, COP27 , will take in the coming weeks in Egypt.

What happens if a party changes its mind?

Once a party has joined the agreement, they cannot begin the process of withdrawal for three years, but there is no financial penalty for leaving.

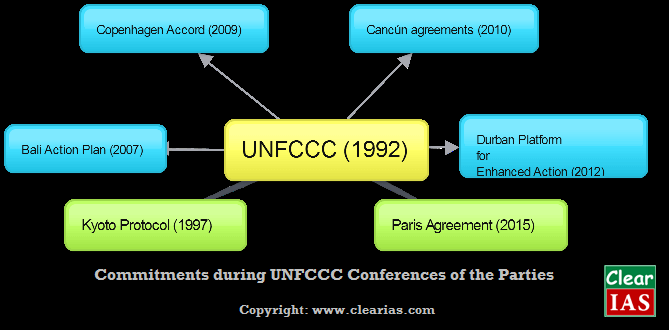

The Paris Agreement signifies years of work in trying to combat climate change. In 1992, countries joined an international treaty, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In 2005, the Kyoto Protocol became a legally binding treaty. It committed its parties to internationally binding emission reduction targets.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Nature and Biodiversity .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Scientists expect global heating to exceed 1.5°C, and other nature and climate stories you need to read this week

May 13, 2024

Scientists have found 700 species in a Cambodian mangrove forest

Funding the green technology innovation pipeline: Lessons from China

May 8, 2024

G7 agrees to phase out use of unabated coal power plants, and other nature and climate stories you need to read this week

May 6, 2024

How to navigate sustainability in the automotive industry

Lena McKnight and Stefan Fahrni

May 2, 2024

Why this Japanese circular built environment makes economic and environmental sense

Anis Nassar, Sebastian Reiter and Yuito Yamada

April 30, 2024

Greenpeace UK

- Email signup

- Donate/Join

What is the Paris climate agreement and why does it matter?

Everything you need to know about the Paris climate agreement – the world’s most important climate change treaty.

16th March 2021

- Climate change

What is the Paris Climate Agreement?

The Paris Climate Agreement is an international treaty that commits most of the world’s governments to addressing climate change.

Forged through decades of negotiations, the Paris Agreement is the world’s first comprehensive climate treaty. Despite its problems, it’s still seen as a major breakthrough in humanity’s effort to tackle the issue. When someone mentions Paris in the context of climate change, this is usually what they’re talking about.

The goal of the Paris Agreement is to stop the world’s average temperature rising more than two degrees, or ideally 1.5ºC.

Doing this would likely prevent the worst impacts of climate change (although it will still cause serious harm, especially to people who did least to cause this crisis). But at the moment the world isn’t even on track to hit that goal.

Almost every government in the world has signed up to the Paris Agreement. The only ones that haven’t joined are Iran, Turkey, Eritrea, Iraq, South Sudan, Libya and Yemen.

The US left the agreement under Donald Trump, but rejoined in early 2021 when President Joe Biden took office.

Is the Paris Agreement working?

Not yet, but it still could. Most experts agree that it’s helped speed up climate action around the world, but not by enough. It’s also a useful framework to help countries work together on climate change. However, it still relies on them taking the problem seriously in the first place.

One recent study has crunched the numbers from commitments and pledges over the last 10 years and found that the Paris Agreement’s goals are “within reach”. But reaching them won’t be easy.

To get back on track, countries need to set more ambitious short-term goals for reducing their emissions. They also need to work harder to keep their promises. Scientists say we need a 45% emissions cut in the next 10 years to stay under that 1.5ºC limit.

For the Paris Climate Agreement to succeed, we’ll need to hugely expand renewable energy. © Paul Langrock / Zenit / Greenpeace

What have countries agreed to?

Under the Paris Agreement, each country has to say how much it will reduce its contribution to climate change . As well as these targets, they also have to publish five-yearly plans for how they’ll make it all happen.

Here’s a quick look at a few countries’ latest commitments:

- UK – pledged to cut emissions 68% by 2030 .

- France – negotiates as part of the EU, which pledged to cut 55% by 2030 .

- USA – 50%–52% below 2005 levels by 2030.

- China – pledged to peak its emissions by 2030 , but a full Paris commitment is still due, which will hopefully be more ambitious.

- Brazil – pledged to cut 43% by 2030, but with a dodgy accounting trick that allows them to actually increase their emissions.

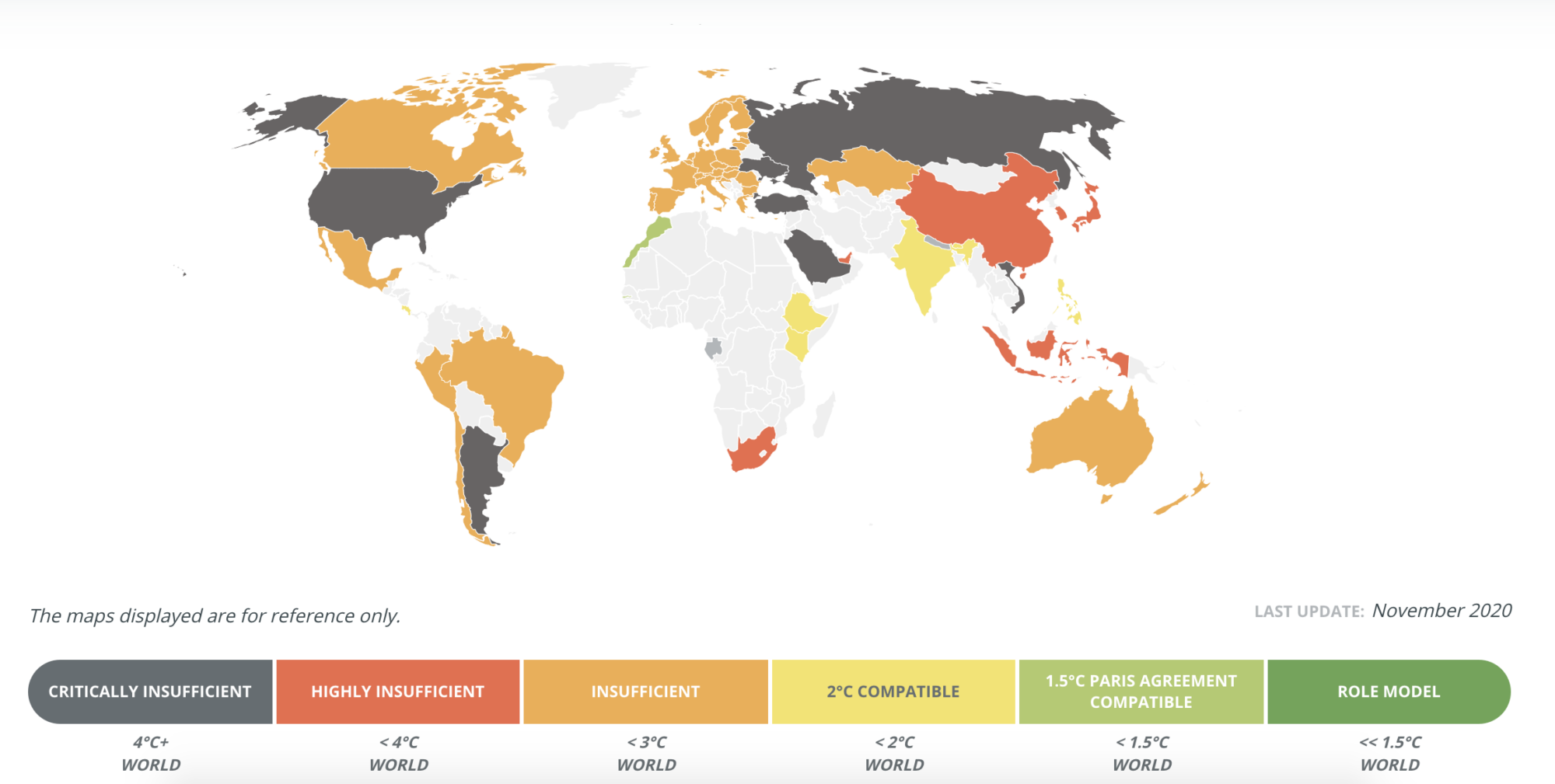

The Climate Action Tracker has a useful summary of different countries’ pledges, and a rating system showing whether they’re doing their fair share. However, the countries that industrialised first should really move even faster, given their responsibility for historic emissions.

Are countries’ plans good enough?

Not yet. The idea is that the world’s combined commitments should be enough to keep us under the 1.5ºC limit. But at the moment, they’re failing this test.

Each government can decide how big its reduction will be. And even if every country hit its current Paris Agreement target, global emissions would only be 1% lower by 2030 , and the world would warm by 2.1 – 3.3ºC . These temperature changes might not sound like much, but in the world’s hugely powerful and delicately-balanced climate system, they make all the difference .

Most countries' climate plans aren't strong enough to meet the goal of the Paris Agreement Climate Action Tracker

This shortfall in countries’ targets is a serious problem. But the Paris Climate Agreement’s designers did anticipate it, and they built in a solution. Under the treaty, countries agreed to keep reviewing and updating their targets and plans, steadily increasing the ambition over time. The EU, Canada, the US, South Korea, Japan, South Africa, and the UK have all strengthened their original commitments recently.

However, these stronger commitments won’t happen without real public pressure. We can all help by telling people in power that they need to do better.

Are countries keeping their promises?

These are long term goals, so it’s important to know if they’re doing enough to get on the right track.

So far it’s a mixed picture, and some countries are doing much more than others. But, if every country just stuck with its current climate policies, the world wouldn’t even hit its existing targets. And as we just learned, even these targets are still much too low.

However, this country-by-country view of climate progress doesn’t give the whole story. These underwhelming headline figures can hide a huge amount of movement below the surface – both good and bad. For example, the rising sales of oversized “SUV” cars have wiped out a huge amount of progress in other areas, because they’re so much more polluting than regular cars.

Look at things like cities , renewable energy , or the financial system and you’ll find similarly fascinating sub-plots in the global climate story. So while it’s good to keep an eye on the big picture, going deeper can help us find the biggest threats and opportunities ahead.

Some cities are reducing dependence on cars by investing in public transport, and making streets safer to walk and cycle © Crispin Hughes

What’s the UK doing?

The UK has done fairly well up until now, but it’s about to run into trouble. For the last 10 years or so, the UK’s carbon footprint has fallen fast. That’s because we’ve mostly stopped using power plants that burn coal – the most polluting fossil fuel.

However, nearly all the coal plants are closed now, so the government needs to find new ways to keep carbon emissions falling. And at the moment, they don’t have enough solid plans in place to make that happen.

Of course, Greenpeace UK is campaigning to change that, and there are loads of ways to get involved. Check out the Take Action page for some ideas.

Is the Paris climate agreement connected to the COP26 climate talks happening in the UK?

Yes, these talks are part of making the Paris agreement work. At the COP26 climate talks , countries will discuss their overall progress in meeting the goals of the Paris agreement, and negotiate a path forward.

COP stands for Conference of the Parties. And 26 is the number of years they’ve been holding these meetings (it’s been slow going). Sadly, the parties in question aren’t the kind with cake and dancing. Parties is diplomatic jargon for countries who’ve signed up to the UN’s climate change framework .

COP26 is important though. It’s the first global meeting where countries have to bring proper emission cutting targets, and plans to show how they’re doing their bit.

Another top priority for COP26 will be making sure that more financially wealthy countries provide more funding to support poorer and more vulnerable countries tackle and adapt to climate change.

This year, the UK is the host country. That means the government has a particular responsibility to get its house in order and lead by example. They’ll also have to work much harder to defend all their bad climate decisions.

What can people do to help?

Right now, the world’s governments are setting us up for a pretty bleak future. But that future isn’t written yet, and it’s up to all of us to make the politicians raise their game. Here are a few resources to get you started:

- Learn more with the Greenpeace guide to climate change .

- Our Take Action page has a menu of things you can do right now.

- Get inspired by the people , campaigns and movements that changed the world.

What's next?

Are world leaders on track to tackle the climate and nature crisis?

It's not too late to avoid the worst of climate change. With the global climate talks coming up in the UK next year, can we lead the world in taking real action now?

Climate change, explained

Everything you need to know about one of the biggest threats facing humanity.

What is the UK's 'net zero' target, and will it be any good?

The government committed the UK to a ‘net zero’ emissions target by 2050. But what does that mean? And will it actually help fight climate change?

Search the United Nations

- What Is Climate Change

- Myth Busters

- Renewable Energy

- Finance & Justice

- Initiatives

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Paris Agreement

- Climate Ambition Summit 2023

- Climate Conferences

- Press Material

- Communications Tips

The Paris Agreement

Climate change is a global emergency that goes beyond national borders. It is an issue that requires international cooperation and coordinated solutions at all levels.

To tackle climate change and its negative impacts, world leaders at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris reached a breakthrough on 12 December 2015: the historic Paris Agreement .

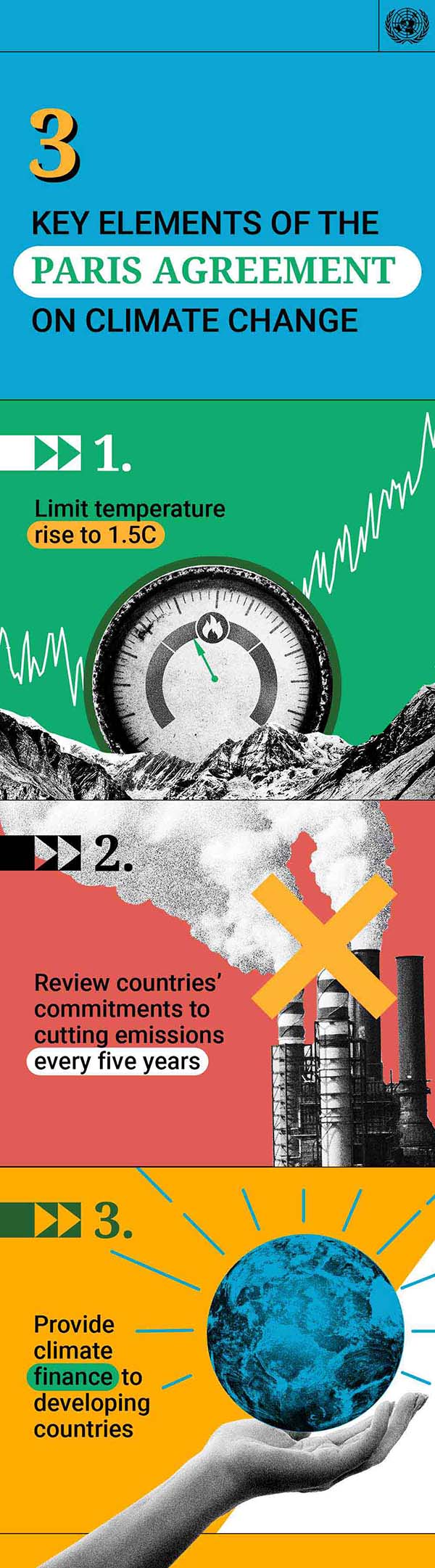

The Agreement sets long-term goals to guide all nations to:

- substantially reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to hold global temperature increase to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change

- periodically assess the collective progress towards achieving the purpose of this agreement and its long-term goals

- provide financing to developing countries to mitigate climate change, strengthen resilience and enhance abilities to adapt to climate impacts.

The Agreement is a legally binding international treaty. It entered into force on 4 November 2016. Today, 195 Parties (194 States plus the European Union) have joined the Paris Agreement.

The Agreement includes commitments from all countries to reduce their emissions and work together to adapt to the impacts of climate change, and calls on countries to strengthen their commitments over time. The Agreement provides a pathway for developed nations to assist developing nations in their climate mitigation and adaptation efforts while creating a framework for the transparent monitoring and reporting of countries’ climate goals.

The Paris Agreement provides a durable framework guiding the global effort for decades to come. It marks the beginning of a shift towards a net-zero emissions world. Implementation of the Agreement is also essential for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals .

How does it work?

The Paris Agreement works on a five- year cycle of increasingly ambitious climate action carried out by countries. Every five years, each country is expected to submit an updated national climate action plan - known as Nationally Determined Contribution , or NDC.

In their NDCs, countries communicate actions they will take to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in order to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement. Countries also communicate in the NDCs actions they will take to build resilience to adapt to the impacts of rising temperatures. In 2023, the first “ global stocktake ” of the world’s efforts under the Paris Agreement concluded at COP28 with a decision on how to accelerate action across all areas – mitigation, adaptation, and finance – by 2030, including a call on governments to speed up the transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy such as wind and solar power in their next round of climate commitments.

To better frame the efforts towards the long-term goal, the Paris Agreement invites countries to formulate and submit long-term strategies . Unlike NDCs, they are not mandatory.

The operational details for the practical implementation of the Paris Agreement were agreed on at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP24) in Katowice, Poland, in December 2018, in what is colloquially called the Paris Rulebook , and finalized at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, in November 2021.

More information on the Paris Agreement can be found here .

Key elements of the Paris Agreement

- To keep global temperatures well below 2C (3.6F) above pre-industrial times while pursuing means to limit the increase to 1.5C.

- To review countries’ contribution to cutting emissions every five years

- To help poorer nations by providing climate finance to adapt to climate change and switch to renewable energy

Aidan Gallagher: The Paris Agreement Works

What is the 'Paris Agreement', and how does it work?

What is net zero? Why is it important? Our net-zero page explains why we need steep emissions cuts now and what efforts are underway.

What is climate adaptation? Why is it so important for every country? Find out how we can protect lives and livelihoods as the climate changes.

How will the world foot the bill? We explain the issues and the value of financing climate action.

Facts and figures

- What is climate change?

- Causes and effects

- Myth busters

Cutting emissions

- Explaining net zero

- High-level expert group on net zero

- Checklists for credibility of net-zero pledges

- Greenwashing

- What you can do

Clean energy

- Renewable energy – key to a safer future

- What is renewable energy

- Five ways to speed up the energy transition

- Why invest in renewable energy

- Clean energy stories

- A just transition

Adapting to climate change

- Climate adaptation

- Early warnings for all

- Youth voices

Financing climate action

- Finance and justice

- Loss and damage

- $100 billion commitment

- Why finance climate action

- Biodiversity

- Human Security

International cooperation

- What are Nationally Determined Contributions

- Acceleration Agenda

- Climate Ambition Summit

- Climate conferences (COPs)

- Youth Advisory Group

- Action initiatives

- Secretary-General’s speeches

- Press material

- Fact sheets

- Communications tips

Advertisement

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Inside Political Debates

The secret ingredients, the paris agreement: summary and evaluation, explanations and implications, the paris agreement on climate change: behind closed doors.

Daniel Bodansky, Steinar Andresen, Daniela Stoycheva, Paul Wapner, Bjørnar Egede-Nissen, the GEP editors, and anonymous reviewers provided valuable comments and helpful suggestions.

- Cite Icon Cite

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Search Site

Radoslav S. Dimitrov; The Paris Agreement on Climate Change: Behind Closed Doors. Global Environmental Politics 2016; 16 (3): 1–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00361

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

The Paris Agreement constitutes a political success in climate negotiations and traditional state diplomacy, and offers important implications for academic research. Based on participatory research, the article examines the political dynamics in Paris and highlights features of the process that help us understand the outcome. It describes battles on key contentious issues behind closed doors, provides a summary and evaluation of the new agreement, identifies political winners and losers, and offers theoretical explanations of the outcome. The analysis emphasizes process variables and underscores the role of persuasion, argumentation, and organizational strategy. Climate diplomacy succeeded because the international conversation during negotiations induced cognitive change. Persuasive arguments about the economic benefits of climate action altered preferences in favor of policy commitments at both national and international levels.

The Paris Agreement is fair and just, comprehensive and balanced, highly ambitious, enduring and effective, and with legally binding force. China’s Closing Statement at COP21, December 12, 2015

Imagine the odds. After two decades of acrimonious debates and dismal failures, UN negotiations produced a climate agreement that was adopted and lauded in superlative terms by the European Union and India, by China, the US and island states. Countries with seemingly irreconcilable differences praised the global arrangement as fair, balanced and ambitious. At the closing session of the Paris Conference on Climate Change, they described the outcome as “revolutionary” (Venezuela), “a tremendous collective achievement” (the EU), “a marvelous act” (China), “a resounding triumph of multilateralism” (St. Lucia) introducing a “new era of global climate governance” (Egypt), and “a tremendous victory for the planet… restoring the global community’s faith that we can accomplish things multilaterally” (USA) (UNFCCC 2015a ).

The Paris Agreement of 2015 is the first global accord on climate change that contains policy obligations for all countries. It is a hybrid that enshrines both bottom-up and top-down approaches to global climate governance (Bodansky 2011 ). The new climate deal is a laissez-faire accord among nations that leaves the content of domestic policy to governments but creates international legal obligations to develop, implement, and regularly strengthen actions. National policies are subject to a robust international transparency system and global reviews, and successive policy plans must be progressively stronger. The policy agreement has considerable weaknesses and, obviously, it is still too early to assess its effectiveness. Nonetheless, the outcome is a political success in negotiations. Remarkably, all major protagonists endorsed the deal, and countries with diametrically opposed interests supported it. This underscores the significant achievement of reaching compromise on one of the most contentious issues in modern history.

How can we explain this result? This article seeks to initiate the academic conversation and examines the political dynamics in Paris from a participant’s perspective. In my view, understanding the diplomatic process is necessary for explaining the outcome. The analysis presented here highlights two process variables: persuasion and organizational tactics. The research for this report was based on direct participatory observation of negotiating sessions, closed ministerial-level meetings, and secret bilateral consultations during the conference. 1 There are compelling reasons why few scholars who serve on government delegations choose to publish their observations: disclosing politically sensitive information may compromise one’s position and future prospects for participation. This article seeks to raise the curtain and provide backstage insight into climate diplomacy, while maintaining confidentiality and keeping direct quotes anonymous. Here I will describe battles on key contentious issues, identify winners and losers, provide a brief summary and evaluation of the Paris Agreement, and highlight features of the process that help us understand the outcome.

The Twenty-First Conference of the Parties (COP-21) was a culmination of a four-year diplomatic process and was characterized by a genuine collective effort to reach mutual compromise, skillfully orchestrated by the French presidency. The political dynamics were obscured by very restricted access. Civil society delegates were left out of negotiating sessions and could only watch TV screens with live coverage of some sessions. Most government delegates also lost access in the second week, when additional required passes were introduced and only four per delegation were provided for the key meetings. Major countries such as Germany had to borrow passes from small countries to keep its diplomats fully involved.

Negotiations in Paris addressed a kaleidoscope of diverse issues, with twenty-four spinoff groups working in the first week. Key contentious issues included the global long-term goal of the agreement and level of policy ambition; the legally binding character of national policy actions; climate finance; and the evolution of the policy regime over time (Rajamani 2015 ).

Legally Binding Obligations

Developed countries were united in Paris in seeking a global agreement that focuses on mitigation; skirts adaptation (important to least developed and island states); preempts legal obligations on finance, compensation, and technology transfer; and includes strong international transparency for national mitigation actions. There were, however, important differences in the North, particularly regarding the legally binding character of the agreement. The EU, supported by a coalition of Latin American countries (AILAC) and most island states (AOSIS) strongly pushed for mandatory and quantified national mitigation policies, and a legal obligation to communicate them internationally upon ratification , in order to make treaty participation contingent on binding domestic action. Europeans also insisted on regular and synchronized policy updates every five years, to ensure that successive mitigation commitments represent a progression beyond previous policy efforts.

Publicly, the US tried to appear constructive and avoided strongly worded opposition statements. In private bilateral consultations, however, they were so adamant against legally binding mitigation and finance that leading diplomats stated with complete certainty: “If we insist on legally binding, the deal will not be global because we will lose the US” (top EU official). In the end, it was the US that weakened mitigation commitments for developed countries in the new agreement. Literally in the last minutes before the final session that adopted the agreement on December 12, the US demanded a single word change: Developed countries “should” rather than “shall” undertake economy-wide quantified emission reductions. The start of the session was delayed for 90 minutes to address this potential crisis, and the EU and the G77 reluctantly accepted. This significant change implied less legally binding action but was never publicly discussed and was hastily slipped in as a ‘technical correction,’ together with punctuation changes!

China wanted a strong legally binding character for general obligations to act but weak international transparency of national policies. As one (anonymous) high-level official put it in internal meetings: “China is maximalist on legally binding and minimalist on transparency.” During late night sessions behind closed doors, they were strongly against a proposal for external expert review teams with access to developing countries, opposed regular policy stocktaking, and wanted to delete references to a global policy review.

Long-term Goal

The coalition of island states (AOSIS) wanted zero net global emissions by 2060–2080, while the EU preferred science-based 80- to 95-percent emission reductions by 2050. A coalition of Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs, including India, China, Saudi Arabia, and Malaysia) opposed quantification and wanted only weak qualitative goals. Similarly, the US wanted a more vague “decarbonization this century,” to signal a global transition away from fossil fuels without setting a clear deadline. One important political development in Paris was the surge of countries who wanted to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. For the first time, now the majority (106 states, to be precise) demanded preventing a temperature rise of 1.5°C. Northern countries preferred 2 degrees instead. The US was mildly opposed even to that, proposing that 2 degrees appear only in the preamble and not in the substantive sections of the treaty. China, India, the US, and Iran even opposed a proposal to commission a special IPCC report on the impacts of a 1.5-degree rise.

In the face of the majority, it was politically inexpedient to oppose publicly 1.5°C. Hence, industrialized countries engaged in a political exercise of linguistic gymnastics: how to craft ‘creative language’ that mentions 1.5 degrees without making it the official operational goal. Similarly, the issue of ‘loss and damage’ was important to many countries who hold the North historically responsible for negative climate impacts. Island states wanted an institutional process to address permanent loss and irreversible damage. All developed countries closed ranks, strongly united against provisions that could lead to liability and compensation, and blocked the creation of institutional arrangements. In closed consultations, rich countries carefully strategized to formulate text that gives nominal recognition to the issue, while precluding legal obligations.

One dramatic and hidden episode of the Paris Conference pertained to finance. Less than 24 hours before the end, a very tense debate among the ministers of rich countries raged behind closed doors. Several Northern countries opposed making financial commitments, and even suggested reversing previous pledges of climate finance. The entire outcome hung in the balance, since finance was a redline issue for the G77 and China. Some European diplomats fought and argued: “Any change in our position on finance will have seismic effects on the negotiations and will wreck the entire deal. What happens in Paris will be in the history books for a long time. Let’s not give any historian a reason to write that we ruined the global response to climate change” (personal notes). Such latter arguments won, and all developed countries accepted a G77 demand for establishing a goal “from a floor of $100 billion dollars per year” by 2025.

Differentiation

A cardinal debate overarching various issues pertained to the future of differentiation between developed and developing countries. The LMDCs sought a continued, sharp distinction between developing and developed countries that defined previous international treaties. India, for instance, demanded financial contributions that are obligatory for developed countries and voluntary for developing ones. Northern countries wanted to replace simplistic ‘binary differentiation’ with a more nuanced and flexible differentiation that reflects national capabilities for both mitigation and finance. The Umbrella Group, 2 the EU, and Switzerland wanted an expansion of the donor base and rejected “unacceptable bifurcated proposals [by the G77] for quantified commitments for public finance by developed countries only” (internal delegation document). The Umbrella Group (especially the US and Japan) were more hardline and vocal on the issue than the EU or Switzerland whose delegations often let the US fight that battle and privately said “If the US can live with it, we can live with it.”

Ultimately, countries demonstrated reciprocal willingness to compromise. In their closing statements, most delegations declared the Paris Agreement to be balanced because most players made sacrifices and gained something in return. China failed to obtain legally binding actions in the North and had to concede global stocktaking and stronger international transparency than they liked. Yet, they largely won the battle over differentiation in both finance and mitigation. The simple binary division between developing and developed countries is now gone but a subtle (and more ambiguous) differentiation remains between developed and “other” countries, “in light of national circumstances.” The US managed to weaken the legally binding character of national actions but lost on their mandatory and progressive evolution as well as on financial differentiation. The EU won on transparency, finance, and loss and damage - but failed to win quantitative global emission targets and restrictions on bunker fuels from international aviation and shipping. Island nations lost on adaptation and loss and damage but their delegates chanted a song outside the plenary hall, celebrating their success in obtaining a strong reference to a 1.5 degree limit as an aspirational goal of the treaty.

The Paris outcome was made possible by the heavy use of secrecy. The agreement is a composite mélange of building block pieces, many of which were negotiated in secret over the two weeks and preceding months. Secrecy is common in diplomacy, but the French finessed it to a new level – and with compelling efficacy. What was different this time was the combination between secrecy and legitimacy: the French Presidency made genuine efforts to accommodate everyone’s central interests through reciprocal trade-offs. They ran the conference in a tightly controlled manner, consulting everyone but keeping the results of consultations generally unknown to delegations who were not directly involved. Diplomats from small and major countries alike such as Brazil, the European Union, or key island states, confided that they did not know all the breakthroughs that were reached in private. Even chief negotiators from the US were seen reading the newest draft of the PA as soon as it was distributed in plenary (two copies per delegation). The crucial last two days of COP21 were dedicated entirely to private consultations, without any official negotiating sessions.

Some of the key issues debated over the past 20 years were resolved in Paris in secret meetings among a few countries. Six working groups on the key issues were established during the second week. One of them concluded its work without a single formal session because everything was settled privately. I participated in a small “invisible” meeting regarding a secret deal between the US and Saudi Arabia. The meeting took place in a small room of 5 by 5 meters, among only 10 individuals. My delegation was asked to accept or reject the bilateral deal, without rights to negotiate or modify. No record was kept, there was no paper copy of the legal text in question that was only displayed on a small screen, and we were explicitly told not to take photos. We endorsed the deal, and so did other ‘key players.’ Yet, when the French Presidency distributed the next draft of the agreement, it did not reflect the closed deal. In fact, the official draft contained text that was exactly the opposite from what was agreed privately!

The value of secrecy was in reducing the number of actors, widely recognized as an obstacle in negotiations (Victor 2011 ). COP21 President Laurent Fabius and his team sought to secure deals only among the key actors on each contentious issue. In a crucial part of the strategy, they kept many delegations in the dark about tradeoffs and compromises already made, until the last hours when they released the final text - and then presented everyone with a fait accompli. Pieces of privately negotiated text were thrown into the final text on the last day, when it would be too late to oppose without appearing to spoil the deal. We were explicitly and repeatedly told that the final text is a “take-it-or-leave it” deal that was not open to renegotiation. The overall purpose of these tactics was to avoid provoking early opposition and to leave no time for reopening major issues.

This raises important questions about transparency and legitimacy in global governance (Bernstein 2004 ). Secretive tactics potentially undermine the effectiveness of policy agreements if they leave governments discontent, and therefore less committed to implement. The reason why this approach worked in Paris was its productiveness: it delivered results and produced an agreement based on mutual compromise. The organizational approach did not trigger the public accusations of unfairness and exclusion that helped wreck Copenhagen in 2009. In the closing session that adopted the PA, most delegations declared the process as fair, inclusive, and transparent. The political process was accepted as legitimate because it delivered results that satisfied key demands of most countries.

The outcome of the conference is captured in a COP Decision on both pre-2020 and long-term policy, with the Paris Agreement (PA) as an annex to the Decision (FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1; C2ES 2015 ). The package of the two texts constitutes the new global arrangement. It is comprehensive in thematic scope and contains provisions on mitigation policy, climate finance, transparency, reporting and review, and international cooperative mechanisms (read, carbon trading), as well as weaker sections on adaptation, capacity building, technology transfer, and forest policy. The Preamble of the PA also recognizes climate justice, the rights of indigenous peoples, gender equality, the empowerment of women and intergenerational equity.

Key provisions include a global objective of holding the temperature increase to “well below 2 C” and to “pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 C” (Article 2), and an aim of reaching global peaking of emissions “as soon as possible” (Art. 4.1). “All Parties are to undertake and communicate ambitious efforts” (Art. 2) and “Each Party shall prepare, communicate and maintain successive nationally determined contributions that it intends to achieve” (Art. 4.2), to be revised every five years, with strongly worded language throughout the text guaranteeing progression over time. Developed countries “should continue taking the lead” with economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets, while developing countries are under a weaker obligation and “should continue enhancing their mitigation efforts, and are encouraged to move over time toward economy-wide emission reduction or limitation targets in light of different national circumstances” (Art. 4.4).

“Developed country Parties shall provide financial resources to assist developing countries” while “other Parties are encouraged” to provide such support voluntarily (Art. 9). The accompanying Decision includes a provision that, after entry into force, Parties shall set a new collective financial goal “from a floor of USD 100 billion per year” (para. 54). The PA also establishes a market-based mechanism for sustainable development and carbon trading, proposed by Brazil and strongly supported by Japan and other developed countries, whose modalities are to be finalized later. Global stocktaking is to take place in 2023 and every five years thereafter, with comprehensive scope to reconsider mitigation, adaptation and finance policies. Compliance mechanisms are weak, with a “facilitative” committee whose work is “non-adversarial and non-punitive” (Art. 15).

Politically, the PA generally favors developed countries of the North, who won most of the key battles. The new climate deal meets all key demands of the US and is based on a model of global climate governance that Japan proposed in the early 1990s: a “pledge and review” system (Andresen 2015 ). The agreement is least fair to the African Group and other Least Developed Countries. It does not include references to their special circumstances, is weak on international dimensions for adaptation policy, and precludes any future claims for liability and compensation.

Strengths of the agreement pertain to principled obligations to act, regularity and progression of national policy development, international transparency and accountability. The PA is weaker on the long-term global goal, adaptation policy, compensation for loss and damage, and technology transfer. Crucially, the PA lacks specificity on the international division of labor for reducing emissions. The sharing of responsibility has been a central challenge in global negotiations (Gupta 2012 ). After decades of negotiations, countries addressed the division of labor for fighting climate change in a surprising way: they mostly avoided the issue. The exact connection between national mitigation policy “contributions” and the global policy goals is not well defined.

The complexity and experimental nature of the PA makes its evaluation difficult and has already raised controversy. In a current debate among international lawyers on the character of the PA, insider legal scholars who participate in the UNFCCC negotiations regard the PA as a legally binding treaty that creates obligations, with a complex mix of mandatory and voluntary provisions (Bodansky 2016 ; Rajamani 2016 ). Like any international treaty, the PA depends on ratification and entry into force. 3 A double threshold for entry into force mirrors the Kyoto Protocol formula: The agreement would become operational when at least 55 countries accounting for at least 55 percent of global emissions ratified. Furthermore, important elements remain to be finalized in negotiations over the next years that may rectify some current weaknesses.

The apparent political achievement of climate negotiations re-emphasizes the importance of traditional state diplomacy and intergovernmental multilateralism in climate governance. The Paris Agreement comes after a series of repeated failures to produce a global treaty over the past decades. This poor record of climate diplomacy had created a virtual consensus among academics, who have argued that UN talks cannot succeed (Hovi et al. 2013 ; Victor 2011 ; Hoffmann 2011 ). Many scholars turned away from interstate institutions and toward productive and theoretically informative research on transnational governance, with a strong emphasis on subnational and nonstate initiatives, and on comparative politics (Bulkeley et al. 2014 ; GEP 2015 ). Reminders of the importance of the UNFCCC process (Depledge and Yamin 2011; Dimitrov 2015 ) and the value of integrating it in the study of climate governance (Betsill et al. 2015 ) have not reversed a general academic skepticism about UN diplomacy. It is still not too late to vindicate some of this pessimism. Obviously, it is too early to assess status of ratification, entry into force, and policy implementation. The weaknesses of the agreement and a lack of political commitment may undermine its environmental effectiveness. 4 Nonetheless, the Paris outcome constitutes a political success in negotiating a meaningful accord. This diplomatic breakthrough raises the need to explain the switch from failure to success in regime formation.

What explains the outcome? Multicausality through an interplay of contextual and process variables likely holds the answer. Three key factors are worth emphasizing here. First, the 2014 bilateral agreement between China and the US helped jumpstart the UN process and evokes notions of ‘club approaches’ (Victor 2011 ; White House 2014 ). Second, as the evidence above suggests, the logistics of the diplomatic process and entrepreneurial leadership by host governments deserves special attention (Depledge 2005 ; Park 2015 ). The timing, pacing, sequencing and coordination of sessions, as well as the strategic rhetoric, were par excellence. Many diplomats praised the French for the organizational tactics and credited them for enabling success. 5

Third, persuasive argumentation and social learning were key factors. In my view, UN diplomacy had already succeeded, even before Paris. Negotiations had facilitated policy change even before producing a formal agreement - because persuasive arguments had changed actors’ minds about the wisdom of climate policy (Dimitrov 2015 ). Ideas tabled during the negotiations since 2005 affected policy preferences and altered cost-benefit calculations. Korea’s concept of ‘green growth’ and European arguments about ‘win-win’ solutions changed perceptions of the economic benefits of climate policy (Dimitrov 2012 ). The ‘win-win’ concept was central to the EU negotiating strategy over the past years. Their arguments, backed by hard data and combined with ambitious unilateral policies in Europe, persuaded policymakers in other countries. A cardinal result of this social learning was the spate of domestic developments around the world (Dubash et al. 2013 ; see also Rising Powers Initiative 2015 ). By the opening of the Paris conference, 186 governments had declared national plans covering 94 percent of global emissions (UNFCCC 2015b ). These policy pledges laid an important foundation for a global UN agreement.

The cognitive mechanisms through which persuasion and dialogue affected actor preferences and policy behavior operate across levels of analysis. Notably, they could help explain both the international success in Paris and domestic developments in multilevel climate governance. Can we understand the US-China bilateral agreement without persuasive EU arguments about the economic benefits of climate policy? The outcome is a case of ecological modernization, with all its positive and negative aspects (Matthews and Paterson 2005). Future research should continue to explore the interplay of structural and process variables, including the micro-dynamics of negotiation, logistical organization, and the role of argumentation in affecting policy preferences.

Political disclaimer: The author served on a government delegation of a developed country during the Paris conference. This article does not contain any information that could compromise the interests of the author’s government or its coalition partners.

The Umbrella Group is a coalition including Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Russia, Ukraine and the United States.

On the first day the PA was open for signature, 175 governments signed it. As of June 21, 2016, 177 signatories and 18 states had ratified the PA, including Norway. See UNFCCC, “Paris Agreement – Status of Ratification,” available at http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9444.php , last accessed June 22, 2016.

The aggregate effect of current national pledges is expected to be a global mean temperature rise of 3.7–4.8 degrees this century (UNFCCC 2015b , 8).

Among many examples, New Zealand stated: “We stand in awe of the French presidency’s unrivalled diplomatic skills in bringing us to a successful conclusion” (closing Plenary statement, December 12, 2012).

Author notes

Email alerts, related articles, related book chapters, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1536-0091

- Print ISSN 1526-3800

A product of The MIT Press

Mit press direct.

- About MIT Press Direct

Information

- Accessibility

- For Authors

- For Customers

- For Librarians

- Direct to Open

- Open Access

- Media Inquiries

- Rights and Permissions

- For Advertisers

- About the MIT Press

- The MIT Press Reader

- MIT Press Blog

- Seasonal Catalogs

- MIT Press Home

- Give to the MIT Press

- Direct Service Desk

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Crossref Member

- COUNTER Member

- The MIT Press colophon is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Success of the Paris Agreement hinges on the credibility of national climate goals

Subscribe to planet policy, david g. victor , david g. victor nonresident senior fellow - foreign policy , global economy and development , energy security and climate initiative marcel lumkowsky , ml marcel lumkowsky research fellow and doctoral candidate, environmental and behavioral economics - university of kassel, germany astrid dannenberg , and ad astrid dannenberg professor, environmental and behavioral economics - university of kassel, germany emily carlton emily carlton research associate, deep decarbonization inititiative - university of california san diego.

September 30, 2022

- 12 min read

Is the Paris Agreement working? That’s hard to tell, because it’s hard to measure. Under the terms of the agreement, each country pledges its own commitments to control emissions, which are not binding under international law. The beauty of the non-binding approach is that countries are free to take risks in how they set their commitments. If commitments were fully binding, as they were in previous approaches — notably the Kyoto Protocol — then diplomats might simply water down the content of agreements to make sure that countries can comfortably comply, or they might refuse to sign on or withdraw altogether.

On paper, the voluntary pledges — known formally as nationally determined contributions (NDCs) — seem to be a very big deal. About 70 percent of world emissions come from countries that have made long-term pledges to cut emissions to net zero, in most cases by 2050. But bold non-binding pledges only work if they reflect true intentions and effort –— what political scientists often call credibility. Credibility is the key currency in international diplomacy whenever there is no practical way to enforce compliance, which is nearly always.

When credibility is high, then cooperation to address the problem of climate change is a bit like a rolling snowball. A growing number of countries make credible commitments, and investors follow by putting money into new technologies. Those technologies get better and cheaper, which makes further commitment easier to achieve politically. Efforts in the highly credible countries and markets then spill over into broader cooperation.

How to measure whether a country keep its climate promises

The theory is elegant, but the problem has always been measurement. How do we know whether a country’s commitment is credible? Most research on pledges made under the Paris Agreement has ducked this question, either by assuming that all the pledges are perfectly credible , or by making guesses about whether national policies and strategies are on track for a country to honor its pledge. A few studies have been tracking the efficacy of national climate policies (for example, here , here , and here ) but those efforts still require a lot of crystal-balling as they peer inside national policy processes to discern how policies will be implemented and their real world impacts. New efforts to systemically assess the country-specific policies needed to meet NDCs, such as the World Bank’s Country Climate and Development Reports (CCDRs) , can be a useful guide to policymakers, but do not typically comment on whether such policies will be implemented as announced.

In a new paper, just published in Nature Climate Change, a team at the University of California, San Diego and the University of Kassel in Germany took a different approach to measuring credibility. We asked some of the world’s leading policy and scientific experts what they thought about the credibility of their own country’s pledges, along with those of many other countries and regions around the world. We also asked them to evaluate the ambition of those pledges, and then stacked up their assessments alongside an array of independent expert assessments of similar questions.

The analysis points to two striking findings:

Countries that set ambitious goals are more likely to meet them

First, when we asked experts to rate pledges relative to what countries have the capacity to implement, we find that the boldest pledges are also the most credible. Here Europe is exceptional — both European and outside experts consider EU pledges to be highly ambitious and the most credible in the world. Yet, outside the wealthy countries that make up the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), experts are optimistic about their countries’ pledges too, judging them to be both quite ambitious and equally credible.

Related Books

Danny Cullenward, David G. Victor

December 12, 2020

Warwick J. McKibbin, Peter J. Wilcoxen

December 16, 2002

Lael Brainard, Isaac Sorkin

August 27, 2009

This result is perhaps unexpected, given the common perception that emerging economies are especially reluctant to commit to ambitious action, and growing concern that financial support from rich countries, on which many developing countries’ pledges depend , may not materialize. But the responses of experts who come from those countries and know their policy processes and motivations best suggest that, in fact, their governments are beginning to see climate action not as an obligation to the international community but as a domestic political opportunity to advance economic growth and local environmental goals, such as limiting air pollution. This is an encouraging shift, but it remains challenging to persuade developing country policymakers that green investments are worth the cost over the long term.

This finding — that ambition and credibility are positively linked — stems from a new way of thinking about ambition. Many independent assessments of NDCs rate their ambition relative to what scientific assessments say countries should do to meet global temperature targets. But this approach, often called “ science-based ,” doesn’t give much attention to economic and political factors that limit what countries actually can do to control emissions. In our study, we ask experts to evaluate their home countries’ pledges ambition “relative to a country’s economic strength.” This approach is a political one that taps into experts’ deep knowledge and experience with their home countries’ political processes and unique economic circumstances by asking them to evaluate their promises based on what is possible practically. (Indeed, the paper is part of a long overdue effort by political scientists to get more centrally involved in studying one of the world’s most important global problems.)

Our results reveal both good news and bad news for the outlook on Paris and climate change mitigation. The good news is that the link between ambition and credibility debunks a commonly-raised fear about non-binding approaches and credibility: that without formal enforcement, governments would set very ambitious goals they have no intention of meeting. When we use the political approach to measuring ambition, we find no support for this.

The bad news is that not all countries are taking the opportunity to pledge up to their potential and follow through with action. Our study indicates that OECD countries outside of Europe — and the United States in particular — are not doing their part, and policymakers know it.

For a long time it has been easy to predict, based on the political forces at work (see here and here ), that the world would underinvest in efforts to control emissions. That logic still applies; at present, the world is on track for warming of about 3⁰C above pre-industrial levels . That’s better than the worst-case projections of a decade ago, but it’s still a lot of warming.

Stable politics and solid institutions make a country more likely to meet climate goals

Our second key finding is that the biggest factors separating credible countries from less credible ones are political and institutional. For a long time, most thinking about what motivates countries to cut emissions hinged on the economic position of the country, including its exposure to the adverse impacts of climate change. For example, developing countries or those that depend on income from fossil fuel production should be less motivated to set and meet ambitious goals, while countries that stand to bear the worst physical damages from warming, such as India , would be more motivated to act. In fact, our results don’t support these explanations: The paper includes statistical tests that probe how much these kinds of variables explain ambition and credibility, and finds they aren’t significant.

What we do find is the importance of the quality of government institutions to explain credibility. Higher quality institutions — those that create stable policy environments over the long term — lead to more credible pledges. (This result is familiar to scholars who have studied investment behavior. When investment projects require massive amounts of capital, as is true for most efforts to cut emissions, there is a premium in markets that can send reliable long-term signals so that capital can be gradually paid off over many years at low risk.)

Our approach of asking elite officials — government officials and scientists — their views, has a lot to offer. Assessing credibility is one of those topics that often requires a lot of expert judgement by people who were “in the room” when the key policy decisions were made and have intuition that is much better than the average non-expert about how to assess the totality of highly complex policy processes and uncertain futures for technology and political attitudes. Put differently, these kinds of senior decisionmakers have a crystal ball that isn’t perfect, but is a lot less cloudy than everyone else’s prognostication methods. Obviously, elites are flawed, often overconfident, and might also have incentives to overstate the credibility of their own country’s actions — biases we limited as much as possible with strict promises of anonymity and some other methods. Nonetheless, our findings around European exceptionalism and the importance of institutions in explaining policy credibility remain highly robust, even when we poked at them using a variety of statistical techniques.

This study is part of a body of research suggesting that successful international cooperation on climate depends not only on setting targets and timetables, but even more on the actions and institutions that make efforts inside a country credible to the rest of the world. That’s true not just for national governments, who are participants in diplomatic processes, but for companies and subnational governments, as more of them start making bold emissions pledges.

Why it’s hard to measure a country’s efforts to meet climate goals

Credibility can be difficult to gauge from the outside. When countries and firms make good faith attempts to cut emissions that ultimately don’t work out, the failures can look like dithering, especially if we look only at numerical emissions results. But such attempts are essential for pushing the frontier of what is possible. Even when they fail, which is inevitable because experimentation is risky, they are extremely revealing. It is vitally important to recognize, reward, and learn from these experiments, especially in sectors where climate solutions are the most uncertain, like aviation, shipping, and heavy industry. If analysts’ measuring sticks for credibility are straight and rigid, we risk labeling productive failures as willful non-compliance and undermining the very efforts we should encourage.

Shifting the dialogue to credibility won’t be easy, precisely because it is so hard to measure. Studies like this one show one way to help improve measurement, but it is also important to advance other methods, including very detailed analyses of NDCs. The Paris Agreement established formal machinery for such assessments, but it is unlikely to have much of an impact because it was designed through consensus diplomacy, which is nearly always a recipe for the lowest common denominator of what is agreeable to all. Policy review processes outside the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (akin to the International Monetary Fund’s Article IV policy reviews , in which a team of economists visits a country to examine how they do things) are encouraging models. Yet, these have proved hard to implement within international organizations where decisions often are driven by consensus and designed to avoid putting inconvenient spotlights on countries.

Still another strategy might be for countries to form clubs or coalitions: small groups of motivated governments and firms that agree to review each other’s pledges and policies in depth, not just to evaluate their adequacy and credibility, but also to learn from one another about what works and what doesn’t. Such small groups are already popping up in regions and industries around the world and were on extensive display last fall in Glasgow. Among others, the United States’ First Movers Coalition is an example.

The primacy of institutions in explaining variations in credibility has some big policy implications. One of those implications is that as governments and firms set up small groups of first movers, the kinds of national policy institutions they have in place should play a big role in determining who should be allowed membership in the club. National institutions that are administratively robust and stable, allowing policies to be implemented once decided, are key. Another big implication is that capacity-building programs that help countries build better institutions are vitally important. While there is a lot of money flowing around climate change, only a modest fraction is really going to effective capacity building. When you look at other areas of successful international cooperation, such as the Montreal Protocol, the 1987 treaty which helped phase out chemicals damaging the ozone layer, a big part of success in achieving global engagement has hinged on investing in the institutions that help countries make their policies credible.

For decades, climate cooperation has been marked by a lot of diplomacy but not much real action because pledges were either non-existent, not particularly ambitious, or disingenuous. That is now changing, and possibly quickly. With the right methods and theories, a rich research agenda is unfolding as we seek to understand the variation in pledges and, through policy processes, shape national action towards better global outcomes.

Related Content

Amar Bhattacharya, David Dollar, Vanda Felbab-Brown, Jeremy Greenwood, Samantha Gross, Shuxian Luo, Sanjay Patnaik, Natan Sachs, Todd Stern, Rahul Tongia, David G. Victor

October 28, 2021

Samantha Gross

August 4, 2022

Todd Stern, Fred Dews

May 31, 2018

Foreign Policy Global Economy and Development

Brookings Initiative on Climate Research and Action

David G. Victor, Joisa Saraiva

April 29, 2024

Tarek Ghani, Juan S. Lozano, Anouk Rigterink, Jacob N. Shapiro

March 13, 2024

David G. Victor

December 7, 2023

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In

Call us: +91-9605741000

Paris Agreement: Simplified

Last updated on September 13, 2023 by ClearIAS Team

Table of Contents

Climate Change: a reality?

- Mostly because of human actions, the concentration of gases like Carbon-di-oxide, Methane etc has increased in earth’s atmosphere and has resulted in phenomena called Green House Effect .

- Because of Green House Effect, the average global temperature has increased, which is known as Global Warming .

- The 2016 average temperatures were about 1.3 °C (2.3 degrees Fahrenheit) above the average in 1880 when global record-keeping began.

- It is estimated that the difference between today’s temperature and the last ice age is about 5°C.

- Global Warming is dangerous all life on earth.

- The only way to deal with the change in climate is to reduce the emission of Green House Gases (GHGs) like Carbon Di Oxide and Methane.

What is Paris Agreement?

- In short, Paris Agreement is an international agreement to combat climate change .

- From 30 November to 11 December 2015, the governments of 195 nations gathered in Paris, France, and discussed a possible new global agreement on climate change, aimed at reducing global greenhouse gas emissions and thus reduce the threat of dangerous climate change.

- The 32-page Paris agreement with 29 articles is widely recognized as a historic deal to stop global warming .

Aims of Paris Agreement

As countries around the world recognized that climate change is a reality, they came together to sign a historic deal to combat climate change – Paris Agreement. The aims of Paris Agreement is as below:

- Keep the global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial level.

- Pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius .

- Strengthen the ability of countries to deal with the impacts of climate change .

It may seem a small change in temperature but this can mean a big difference for the Earth!

Paris Agreement: Things to note

- In French, the Paris Agreement is known as L’accord de Paris.

- The key vision of Paris Agreement is to keep global temperatures “well below” 2.0C (3.6F) above pre-industrial times and “endeavour to limit” them even more, to 1.5C.

- Paris Accord talks about limiting the amount of greenhouse gases emitted by human activity to the same levels that trees, soil and oceans can absorb naturally, beginning at some point between 2050 and 2100.

- It also mentions the need to review each country’s contribution to cutting emissions every five years so they scale up to the challenge.

- Rich countries should help poorer nations by providing “climate finance” to adapt to climate change and switch to renewable energy.

- The Paris Agreement has a ‘bottom up’ structure in contrast to most international environmental law treaties which are ‘top down.

- The agreement is binding in some elements like reporting requirements, while leaving other aspects of the deal such as the setting of emissions targets for any individual country as non-binding.

- Note: You can download the Paris Agreement from this link .

Is this the first international agreement to combat climate change due to global warming?

No. In fact, Paris Agreement comes under the broad umbrella of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) . UNFCCC is a convention held in 1992 to combat climate change. Kyoto Protocol (1997) was another major international commitment under UNFCCC.

Paris Agreement (2015) vs Kyoto Protocol (1997)

- Paris Agreement is the world’s first comprehensive climate agreement. Although developed and developing countries were parties to Kyoto Protocol , developing countries were not mandated to reduce their emissions.

- This means that while Paris Agreement is legally binding to all parties, Kyoto Protocol was not.

- Paris Agreement was reached on the twenty-first session of the Conference of the Parties (COP) and the eleventh session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP) .

Add IAS, IPS, or IFS to Your Name!

Your Effort. Our Expertise.

Join ClearIAS

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC)

- The national pledges by countries to cut emissions are voluntary .

- The Paris Agreement requires all Parties to put forward their best efforts through “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) and to strengthen these efforts in the years ahead.

- This includes requirements that all Parties report regularly on their emissions and on their implementation efforts.

- In 2018 , Parties will take stock of the collective efforts in relation to progress towards the goal set in the Paris Agreement.

- There will also be a global stock take every 5 years to assess the collective progress towards achieving the purpose of the Agreement and to inform further individual actions by Parties.

India’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC)

- India’s INDC include a reduction in the emissions intensity of its GDP by 33 to 35 per cent by 2030 from 2005 level.