Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

MLA Tables, Figures, and Examples

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The purpose of visual materials or other illustrations is to enhance the audience's understanding of information in the document and/or awareness of a topic. Writers can embed several types of visuals using most basic word processing software: diagrams, musical scores, photographs, or, for documents that will be read electronically, audio/video applications. Because MLA style is most often used in the humanities, it is unlikely that you will include raw scientific data in an MLA-style paper, but you may be asked to include other kinds of research in your writing. For additional information on writing a research paper in MLA style, visit the MLA Style Center’s page on Formatting a Research Paper .

General guidelines

- Collect sources. Gather the source information required for MLA documentation for the source medium of the illustration (e.g. print, Web, podcast).

- Determine what types of illustrations best suit your purpose. Consider the purpose of each illustration, how it contributes to the purpose of the document and the reader's understanding, and whether the audience will be able to view and/or understand the illustration easily.

- Use illustrations of the best quality. Avoid blurry, pixilated, or distorted images for both print and electronic documents. Often pixelation and distortion occurs when writers manipulate image sizes. Keep images in their original sizes or use photo editing software to modify them. Reproduce distorted graphs, tables, or diagrams with spreadsheet or publishing software, but be sure to include all source information. Always represent the original source information faithfully and avoid unethical practices of false representation or manipulation (this is considered plagiarism) .

- Use illustrations sparingly. Decide what items can best improve the document's ability to augment readers' understanding of the information, appreciation for the subject, and/or illustration of the main points. Do not provide illustrations for illustrations' sake. Scrutinize illustrations for how potentially informative or persuasive they can be.

- Do not use illustrations to boost page length. In the case of student papers, instructors often do not count the space taken up by visual aids toward the required page length of the document. Remember that texts explain, while illustrations enhance. Illustrations cannot carry the entire weight of the document.

Labels, captions, and source information

Illustrations appear directly embedded in the document, except in the case of manuscripts that are being prepared for publication. (For preparing manuscripts with visual materials for publication, see Note on Manuscripts below.) Each illustration must include a label, a number, a caption and/or source information.

- The illustration label and number should always appear in two places: the document main text (e.g. see fig. 1 ) and near the illustration itself ( Fig. 1 ).

- Captions provide titles or explanatory notes (e.g., Van Gogh’s The Starry Night)

- Source information documentation will always depend upon the medium of the source illustration. If you provide source information with all of your illustrations, you do not need to provide this information on the Works Cited page.

MLA documentation for tables, figures, and examples

MLA provides three designations for document illustrations: tables, figures, and examples (see specific sections below).

- Refer to the table and its corresponding numeral in-text. Do not capitalize the word table. This is typically done in parentheses (e.g. "(see table 2)").

- Situate the table near the text to which it relates.

- Align the table flush-left to the margin.

- Label the table 'Table' and provide its corresponding Arabic numeral. No punctuation is necessary after the label and number (see example below).

- On the next line, provide a caption for the table, most often the table title. Use title case.

- Place the table below the caption, flush-left, making sure to maintain basic MLA style formatting (e.g. one-inch margins).

- Below the title, signal the source information with the descriptor "Source," followed by a colon, then provide the correct MLA bibliographic information for the source in note form (see instructions and examples above). If you provide source information with your illustrations, you do not need to provide this information on the Works Cited page.

- If additional caption information or explanatory notes is necessary, use lowercase letters formatted in superscript in the caption information or table. Below the source information, indent, provide a corresponding lowercase letter (not in superscript), a space, and the note.

- Labels, captions, and notes are double-spaced.

Table Example

In-text reference:

In 1985, women aged 65 and older were 59% more likely than men of the same age to reside in a nursing home, and though 11,700 less women of that age group were enrolled in 1999, men over the same time period ranged from 30,000 to 39,000 persons while women accounted for 49,000 to 61,500 (see table 1).

Table reference:

Rate of Nursing Home Residence among People Age 65 or Older, by Sex and Age Group, 1985, 1995, 1997, 1999 a

Example Table

Source: Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, Older Americans 2008: Key Indicators of Well-Being , Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, Mar. 2008, table 35A.

a. Note: Rates for 65 and over category are age-adjusted using the 2000 standard population. Beginning in 1997, population figures are adjusted for net underenumeration using the 1990 National Population Adjustment Matrix from the U.S. Census Bureau. People residing in personal care or domiciliary care homes are excluded from the numerator.

- All visuals/illustrations that are not tables or musical score examples (e.g. maps, diagrams, charts, videos, podcasts, etc.) are labeled Figure or Fig.

- Refer to the figure in-text and provide an Arabic numeral that corresponds to the figure. Do not capitalize figure or fig .

- MLA does not specify alignment requirements for figures; thus, these images may be embedded as the reader sees fit. However, continue to follow basic MLA Style formatting (e.g. one-inch margins).

- Below the figure, provide a label name and its corresponding arabic numeral (no bold or italics), followed by a period (e.g. Fig. 1.). Here, Figure and Fig . are capitalized.

- Beginning with the same line as the label and number, provide a title and/or caption as well as relevant source information in note form (see instructions and examples above). If you provide source information with your illustrations, you do not need to provide this information on the Works Cited page.

- If full citation information is provided in the caption, use the same formatting as you would for your Works Cited page. However, names should be listed in first name last name format.

Figure Example

Some readers found Harry’s final battle with Voldemort a disappointment, and recently, the podcast, MuggleCast debated the subject (see fig. 2).

Figure caption (below an embedded podcast file for a document to be viewed electronically):

Fig. 2. Harry Potter and Voldemort final battle debate from Andrew Sims et al.; “Show 166”; MuggleCast ; MuggleNet.com, 19 Dec. 2008, www.mugglenet.com/2015/11/the-snape-debate-rowling-speaks-out.

Musical Illustrations/"Examples"

- The descriptor "Example" only refers to musical illustrations (e.g. portions of a musical score). It is often abbreviated "ex ."

- Refer to the example in-text and provide an Arabic numeral that corresponds to the example. Do not capitalize "example" or "ex " in the text.

- Supply the illustration, making sure to maintain basic MLA Style formatting (e.g. one-inch margins).

- Below the example, provide the label (capitalizing Example or Ex . ) and number and a caption or title. The caption or title will often take the form of source information along with an explanation, for example, of what part of the score is being illustrated. If you provide source information with your illustrations, you do not need to provide this information on the Works Cited page.

Musical Illustration Example

In Ambroise Thomas's opera Hamlet, the title character's iconic theme first appears in Act 1. As Hamlet enters the castle's vacant grand hall following his mother's coronation, the low strings begin playing the theme (ex 1).

Musical Illustration reference:

Ex. 1: Hamlet's Theme

Source: Thomas, Ambroise. Hamlet . 1868.

Source information and note form

Notes serve two purposes: to provide bibliographic information and to provide additional context for information in the text. When it comes to citing illustrations, using notes allows for the bibliographic information as close to the illustration as possible.

Note form entries appear much like standard MLA bibliographic entries with a few exceptions:

- Author names are in First_Name—Last_Name format.

- Commas are substituted for periods (except in the case of the period that ends the entry).

- Publication information for books (publisher, year) appears in parentheses.

- Relevant page numbers follow the publication information.

Note: Use semicolons to denote entry sections when long series of commas make these sections difficult to ascertain as being like or separate (see examples below.) The MLA Handbook (8 th ed.) states that if the table or illustration caption provides complete citation information about the source and the source is not cited in the text, authors do not need to list the source in the Works Cited list.

For additional information, visit the MLA Style Center’s page on Using Notes in MLA Style .

Examples - Documenting source information in "Note form"

The following examples provide information on how a note might look following an illustration. Write the word “Source” immediately before your source note. If an illustration requires more than one note, label additional notes with lowercase letters, starting with a (see the note underneath the example table above).

Tom Shachtman, Absolute Zero and the Conquest of Cold (Houghton Mifflin, 1999), p. 35.

Website (using semicolons to group like information together)

United States; Dept. of Commerce; Census Bureau; Manufacturing, Mining, and Construction Statistics; Housing Units Authorized by Building Permits ; US Dept. of Commerce, 5 Feb. 2008; Table 1a.

In this example, the commas in Manufacturing, Mining, and Construction Statistics prompt the need for semicolons in order for the series information to be read easily. Even if Manufacturing, Mining, and Construction Statistics had not appeared in the entry, the multiple "author names" of United States, Dept. of Commerce, and Census Bureau would have necessitated the use of a semicolon before and after the title and between ensuing sections to the end of the entry.

Furthermore, the publisher and date in a standard entry are separated by a comma and belong together; thus, their inclusion here (US Dept. of Commerce, 5 Feb. 2008) also necessitates the semicolons.

Note on manuscripts

Do not embed illustrations (tables, figures, or examples) in manuscripts for publication. Put placeholders in the text to show where the illustrations will go. Type these placeholders on their own line, flush left, and bracketed (e.g. [table 1]). At the end of the document, provide label, number, caption, and source information in an organized list. Send files for illustrations in the appropriate format to your editor separately. If you provide source information with your illustrations, you do not need to provide this information on the Works Cited page.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Use Tables & Graphs in a Research Paper

It might not seem very relevant to the story and outcome of your study, but how you visually present your experimental or statistical results can play an important role during the review and publication process of your article. A presentation that is in line with the overall logical flow of your story helps you guide the reader effectively from your introduction to your conclusion.

If your results (and the way you organize and present them) don’t follow the story you outlined in the beginning, then you might confuse the reader and they might end up doubting the validity of your research, which can increase the chance of your manuscript being rejected at an early stage. This article illustrates the options you have when organizing and writing your results and will help you make the best choice for presenting your study data in a research paper.

Why does data visualization matter?

Your data and the results of your analysis are the core of your study. Of course, you need to put your findings and what you think your findings mean into words in the text of your article. But you also need to present the same information visually, in the results section of your manuscript, so that the reader can follow and verify that they agree with your observations and conclusions.

The way you visualize your data can either help the reader to comprehend quickly and identify the patterns you describe and the predictions you make, or it can leave them wondering what you are trying to say or whether your claims are supported by evidence. Different types of data therefore need to be presented in different ways, and whatever way you choose needs to be in line with your story.

Another thing to keep in mind is that many journals have specific rules or limitations (e.g., how many tables and graphs you are allowed to include, what kind of data needs to go on what kind of graph) and specific instructions on how to generate and format data tables and graphs (e.g., maximum number of subpanels, length and detail level of tables). In the following, we will go into the main points that you need to consider when organizing your data and writing your result section .

Table of Contents:

Types of data , when to use data tables .

- When to Use Data Graphs

Common Types of Graphs in Research Papers

Journal guidelines: what to consider before submission.

Depending on the aim of your research and the methods and procedures you use, your data can be quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative data, whether objective (e.g., size measurements) or subjective (e.g., rating one’s own happiness on a scale), is what is usually collected in experimental research. Quantitative data are expressed in numbers and analyzed with the most common statistical methods. Qualitative data, on the other hand, can consist of case studies or historical documents, or it can be collected through surveys and interviews. Qualitative data are expressed in words and needs to be categorized and interpreted to yield meaningful outcomes.

Quantitative data example: Height differences between two groups of participants Qualitative data example: Subjective feedback on the food quality in the work cafeteria

Depending on what kind of data you have collected and what story you want to tell with it, you have to find the best way of organizing and visualizing your results.

When you want to show the reader in detail how your independent and dependent variables interact, then a table (with data arranged in columns and rows) is your best choice. In a table, readers can look up exact values, compare those values between pairs or groups of related measurements (e.g., growth rates or outcomes of a medical procedure over several years), look at ranges and intervals, and select specific factors to search for patterns.

Tables are not restrained to a specific type of data or measurement. Since tables really need to be read, they activate the verbal system. This requires focus and some time (depending on how much data you are presenting), but it gives the reader the freedom to explore the data according to their own interest. Depending on your audience, this might be exactly what your readers want. If you explain and discuss all the variables that your table lists in detail in your manuscript text, then you definitely need to give the reader the chance to look at the details for themselves and follow your arguments. If your analysis only consists of simple t-tests to assess differences between two groups, you can report these results in the text (in this case: mean, standard deviation, t-statistic, and p-value), and do not necessarily need to include a table that simply states the same numbers again. If you did extensive analyses but focus on only part of that data (and clearly explain why, so that the reader does not think you forgot to talk about the rest), then a graph that illustrates and emphasizes the specific result or relationship that you consider the main point of your story might be a better choice.

When to Use Data Graphs

Graphs are a visual display of information and show the overall shape of your results rather than the details. If used correctly, a visual representation helps your (or your reader’s) brain to quickly understand large amounts of data and spot patterns, trends, and exceptions or outliers. Graphs also make it easier to illustrate relationships between entire data sets. This is why, when you analyze your results, you usually don’t just look at the numbers and the statistical values of your tests, but also at histograms, box plots, and distribution plots, to quickly get an overview of what is going on in your data.

Line graphs

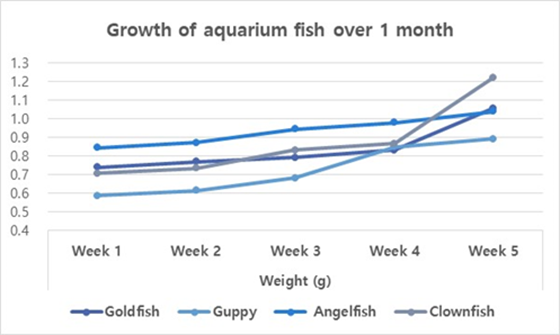

When you want to illustrate a change over a continuous range or time, a line graph is your best choice. Changes in different groups or samples over the same range or time can be shown by lines of different colors or with different symbols.

Example: Let’s collapse across the different food types and look at the growth of our four fish species over time.

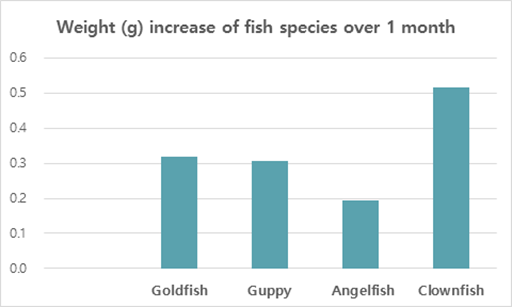

You should use a bar graph when your data is not continuous but divided into categories that are not necessarily connected, such as different samples, methods, or setups. In our example, the different fish types or the different types of food are such non-continuous categories.

Example: Let’s collapse across the food types again and also across time, and only compare the overall weight increase of our four fish types at the end of the feeding period.

Scatter plots

Scatter plots can be used to illustrate the relationship between two variables — but note that both have to be continuous. The following example displays “fish length” as an additional variable–none of the variables in our table above (fish type, fish food, time) are continuous, and they can therefore not be used for this kind of graph.

As you see, these example graphs all contain less data than the table above, but they lead the reader to exactly the key point of your results or the finding you want to emphasize. If you let your readers search for these observations in a big table full of details that are not necessarily relevant to the claims you want to make, you can create unnecessary confusion. Most journals allow you to provide bigger datasets as supplementary information, and some even require you to upload all your raw data at submission. When you write up your manuscript, however, matching the data presentation to the storyline is more important than throwing everything you have at the reader.

Don’t forget that every graph needs to have clear x and y axis labels , a title that summarizes what is shown above the figure, and a descriptive legend/caption below. Since your caption needs to stand alone and the reader needs to be able to understand it without looking at the text, you need to explain what you measured/tested and spell out all labels and abbreviations you use in any of your graphs once more in the caption (even if you think the reader “should” remember everything by now, make it easy for them and guide them through your results once more). Have a look at this article if you need help on how to write strong and effective figure legends .

Even if you have thought about the data you have, the story you want to tell, and how to guide the reader most effectively through your results, you need to check whether the journal you plan to submit to has specific guidelines and limitations when it comes to tables and graphs. Some journals allow you to submit any tables and graphs initially (as long as tables are editable (for example in Word format, not an image) and graphs of high enough resolution.

Some others, however, have very specific instructions even at the submission stage, and almost all journals will ask you to follow their formatting guidelines once your manuscript is accepted. The closer your figures are already to those guidelines, the faster your article can be published. This PLOS One Figure Preparation Checklist is a good example of how extensive these instructions can be – don’t wait until the last minute to realize that you have to completely reorganize your results because your target journal does not accept tables above a certain length or graphs with more than 4 panels per figure.

Some things you should always pay attention to (and look at already published articles in the same journal if you are unsure or if the author instructions seem confusing) are the following:

- How many tables and graphs are you allowed to include?

- What file formats are you allowed to submit?

- Are there specific rules on resolution/dimension/file size?

- Should your figure files be uploaded separately or placed into the text?

- If figures are uploaded separately, do the files have to be named in a specific way?

- Are there rules on what fonts to use or to avoid and how to label subpanels?

- Are you allowed to use color? If not, make sure your data sets are distinguishable.

If you are dealing with digital image data, then it might also be a good idea to familiarize yourself with the difference between “adjusting” for clarity and visibility and image manipulation, which constitutes scientific misconduct . And to fully prepare your research paper for publication before submitting it, be sure to receive proofreading services , including journal manuscript editing and research paper editing , from Wordvice’s professional academic editors .

IMAGES

VIDEO