Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

Triangulation in Research | Guide, Types, Examples

Published on January 3, 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Triangulation in research means using multiple datasets, methods, theories, and/or investigators to address a research question . It’s a research strategy that can help you enhance the validity and credibility of your findings and mitigate the presence of any research biases in your work.

Triangulation is mainly used in qualitative research , but it’s also commonly applied in quantitative research . If you decide on mixed methods research , you’ll always use methodological triangulation.

- Qualitative research: You conduct in-depth interviews with different groups of stakeholders, such as parents, teachers, and children.

- Quantitative research: You run an eye-tracking experiment and involve three researchers in analyzing the data.

- Mixed methods research: You conduct a quantitative survey, followed by a few (qualitative) structured interviews.

Table of contents

Types of triangulation in research, what is the purpose of triangulation, pros and cons of triangulation in research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about triangulation.

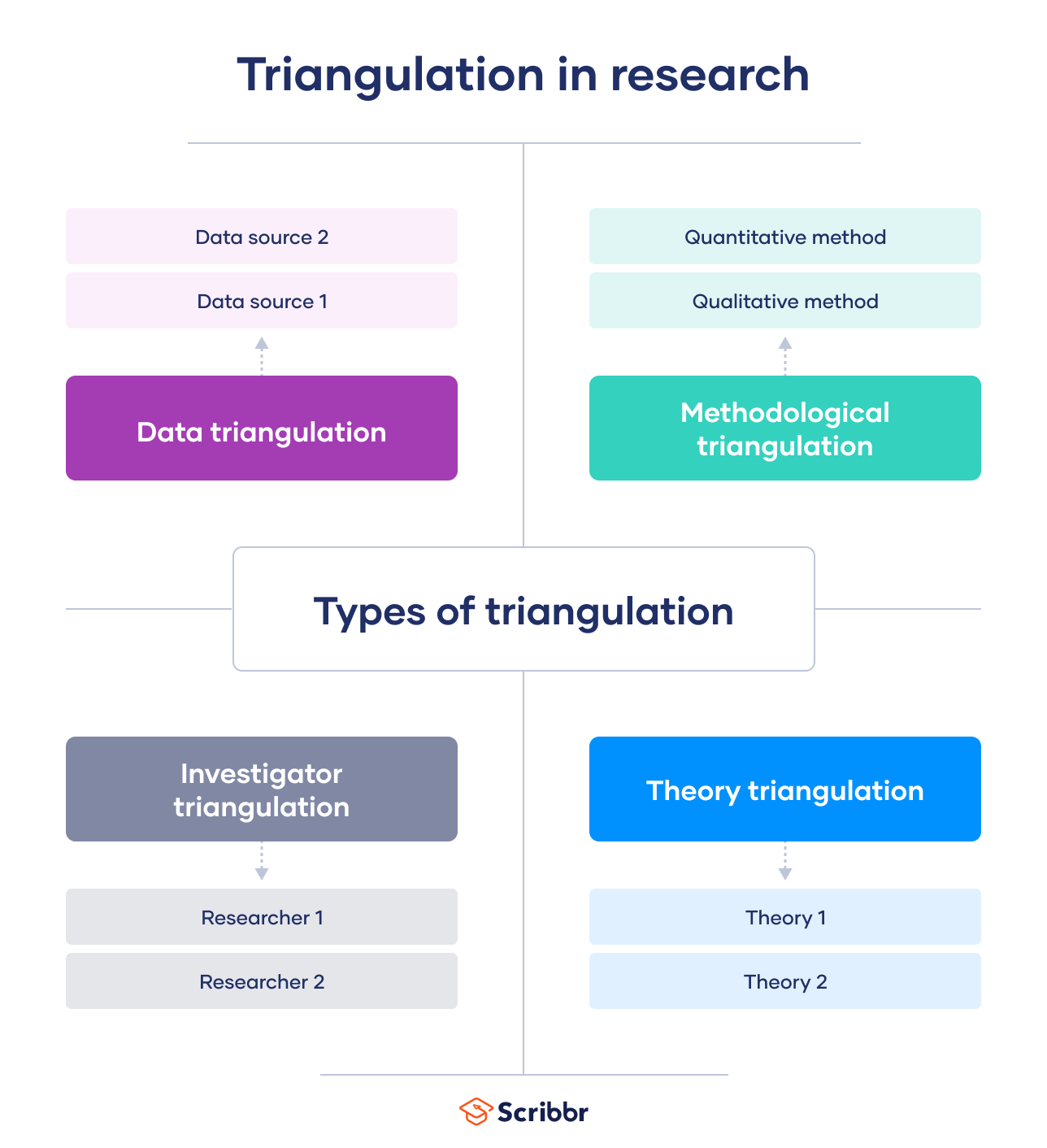

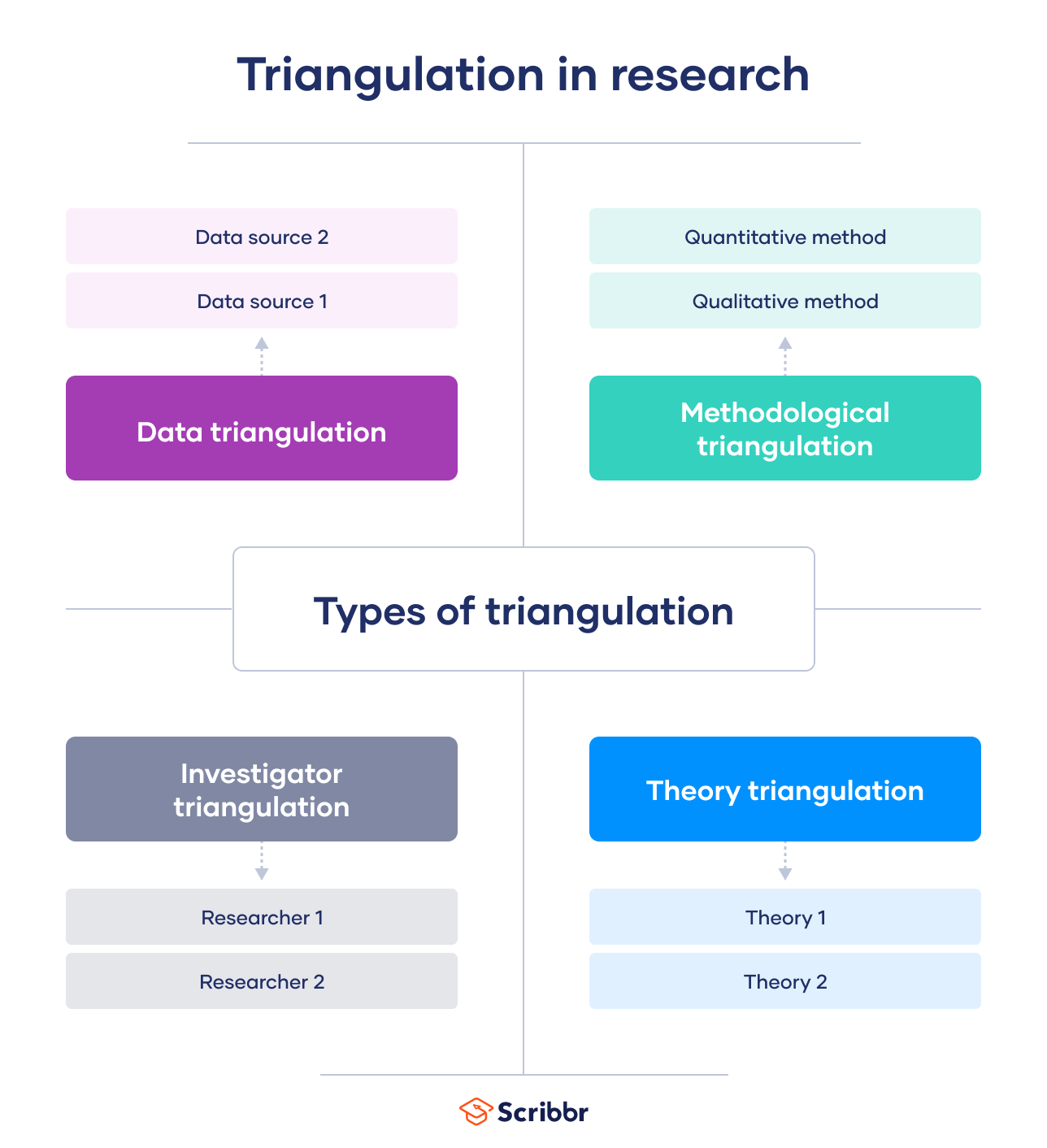

There are four main types of triangulation:

- Data triangulation: Using data from different times, spaces, and people

- Investigator triangulation: Involving multiple researchers in collecting or analyzing data

- Theory triangulation: Using varying theoretical perspectives in your research

- Methodological triangulation : Using different methodologies to approach the same topic

We’ll walk you through the four types of triangulation using an example. This example is based on a real study .

Methodological triangulation

When you use methodological triangulation, you use different methods to approach the same research question.

This is the most common type of triangulation, and researchers often combine qualitative and quantitative research methods in a single study.

Methodological triangulation is useful because you avoid the flaws and research bias that come with reliance on a single research technique.

Data triangulation

In data triangulation, you use multiple data sources to answer your research question. You can vary your data collection across time, space, or different people.

When you collect data from different samples, places, or times, your results are more likely to be generalizable to other situations.

Investigator triangulation

With investigator triangulation, you involve multiple observers or researchers to collect, process, or analyze data separately.

They review video recordings of your participants playing team games in pairs and analyze and note down any cooperative behaviors. You check that their code sheets line up with each other to ensure high interrater reliability.

Investigator triangulation helps you reduce the risk of observer bias and other experimenter biases.

Theory triangulation

Triangulating theory means applying several different theoretical frameworks in your research instead of approaching a research question from just one theoretical perspective.

- People cooperate for a sense of reward: they cooperate to feel good.

- People cooperate to avoid guilt: they cooperate to avoid feeling bad.

Testing competing hypotheses is one way to perform theory triangulation. Using theory triangulation may help you understand a research problem from different perspectives or reconcile contradictions in your data.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Researchers use triangulation for a more holistic perspective on a specific research question. Triangulation is also helpful for enhancing credibility and validity.

To cross-check evidence

It’s important to gather high-quality data for rigorous research. When you have data from only one source or investigator, it may be difficult to say whether the data are trustworthy.

But if data from multiple sources or investigators line up, you can be more certain of their credibility.

Credibility is about how confident you can be that your findings reflect reality. The more your data converge, or or agree with each other, the more credible your results will be.

For a complete picture

Triangulation helps you get a more complete understanding of your research problem.

When you rely on only one data source, methodology, or investigator, you may risk bias in your research. Observer bias may occur when there’s only one researcher collecting data. Similarly, using just one methodology means you may be disadvantaged by the inherent flaws and limitations of that method.

- Behavioral observations from a lab setting

- Self-report survey data from participants reflecting on their daily lives

- Neural data from an fMRI scanner during a cooperative task

It’s helpful to use triangulation when you want to capture the complexity of real-world phenomena. By varying your data sources, theories, and methodologies, you gain insights into the research problem from multiple perspectives and levels.

To enhance validity

Validity is about how accurately a method measures what it’s supposed to measure.

You can increase the validity of your research through triangulation. Since each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, you can combine complementary methods that account for each other’s limitations.

In contrast, survey data offers you more insights into everyday behaviors outside a lab setting, but since it’s self-reported, it may be biased.

Finally, fMRI data can tell you more about hidden neural mechanisms without any participant interference. But this type of data is only valuable for your research when combined with the others.

Like all research strategies, triangulation has both advantages and disadvantages.

Reduces bias

Triangulating data, methods, investigators, or theories helps you avoid the research bias that comes with using a single perspective in your research. You’ll get a well-rounded look into the research topic when you use triangulation.

Establishes credibility and validity

Combining different methods, data sources, and theories enhances the credibility and validity of your research. You’ll be able to trust that your data reflect real life more closely when you gather them using multiple perspectives and techniques.

Time-consuming

Triangulation can be very time-consuming and labor-intensive. You’ll need to juggle different datasets, sources, and methodologies to answer one research question.

This type of research often involves an interdisciplinary team and a higher cost and workload. You’ll need to weigh your options and strike a balance based on your time frame and research needs.

Inconsistent

Sometimes, the data from different sources, investigators, methods may not line up to give you a clear picture. Your data may be inconsistent or contradict each other.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that your research is incoherent. Rather, you’ll need to dig deeper to make sense of why your data are contradictory. These inconsistencies can be challenging but may also lead to new avenues for further research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Triangulation in research means using multiple datasets, methods, theories and/or investigators to address a research question. It’s a research strategy that can help you enhance the validity and credibility of your findings.

Triangulation is mainly used in qualitative research , but it’s also commonly applied in quantitative research . Mixed methods research always uses triangulation.

There are four main types of triangulation :

- Data triangulation : Using data from different times, spaces, and people

- Investigator triangulation : Involving multiple researchers in collecting or analyzing data

- Theory triangulation : Using varying theoretical perspectives in your research

Triangulation can help:

- Reduce research bias that comes from using a single method, theory, or investigator

- Enhance validity by approaching the same topic with different tools

- Establish credibility by giving you a complete picture of the research problem

But triangulation can also pose problems:

- It’s time-consuming and labor-intensive, often involving an interdisciplinary team.

- Your results may be inconsistent or even contradictory.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). Triangulation in Research | Guide, Types, Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/triangulation/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, mixed methods research | definition, guide & examples, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, observer bias | definition, examples, prevention, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

The use of triangulation in qualitative research

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Nursing, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario.

- 2 School of Nursing and Department of Oncology, McMaster University.

- 3 School of Nursing and the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University.

- 4 School of Nursing, McMaster University.

- 5 Department of Oncology, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, Canada.

- PMID: 25158659

- DOI: 10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

Triangulation refers to the use of multiple methods or data sources in qualitative research to develop a comprehensive understanding of phenomena (Patton, 1999). Triangulation also has been viewed as a qualitative research strategy to test validity through the convergence of information from different sources. Denzin (1978) and Patton (1999) identified four types of triangulation: (a) method triangulation, (b) investigator triangulation, (c) theory triangulation, and (d) data source triangulation. The current article will present the four types of triangulation followed by a discussion of the use of focus groups (FGs) and in-depth individual (IDI) interviews as an example of data source triangulation in qualitative inquiry.

Keywords: focus groups; in-depth individual interviews; qualitative research; triangulation.

- Data Collection

- Focus Groups

- Group Processes

- Interviews as Topic

- Models, Theoretical

- Qualitative Research*

- Research Design*

- Research Personnel

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Triangulation in Research – Types, Methods and Guide

Triangulation in Research – Types, Methods and Guide

Table of Contents

Triangulation

Definition:

Triangulation is a research technique that involves the use of multiple methods or sources of data to increase the validity and reliability of findings.

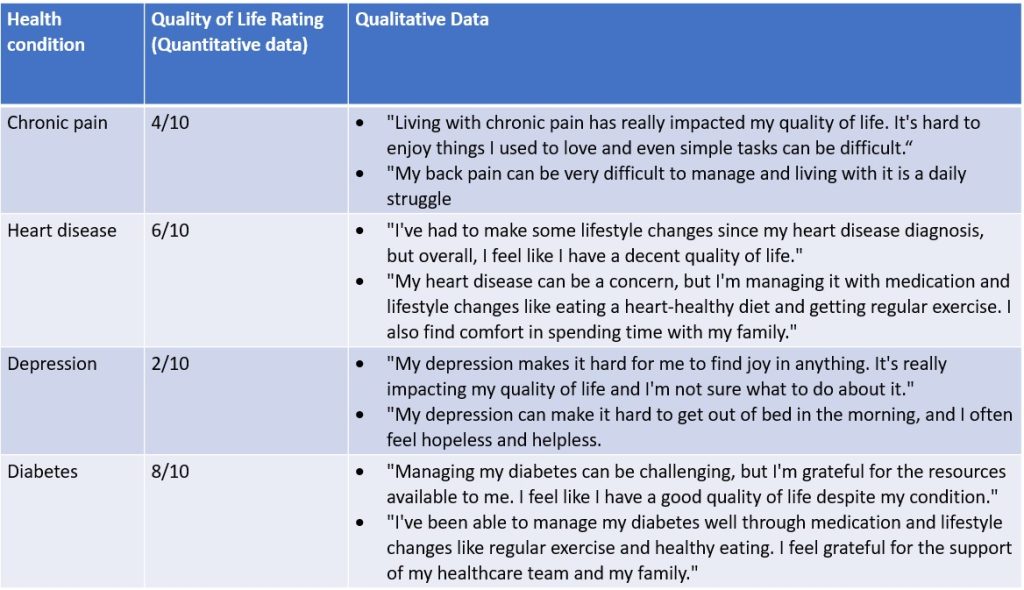

When triangulated, data from different sources can be combined and analyzed to produce a more accurate understanding of the phenomenon being studied. Triangulation can be used in both quantitative and qualitative research and can be implemented at any stage of the research process.

Types of Triangulation

There are many types of Triangulation in research but we are featuring only Five main types:

Data Triangulation

Data triangulation is the use of multiple sources of data to examine a research question or phenomenon. This can include using a variety of data collection methods, such as surveys, interviews, observations, and document analysis, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. By using multiple sources of data, researchers can validate their findings and reduce the risk of bias that may occur when using a single method.

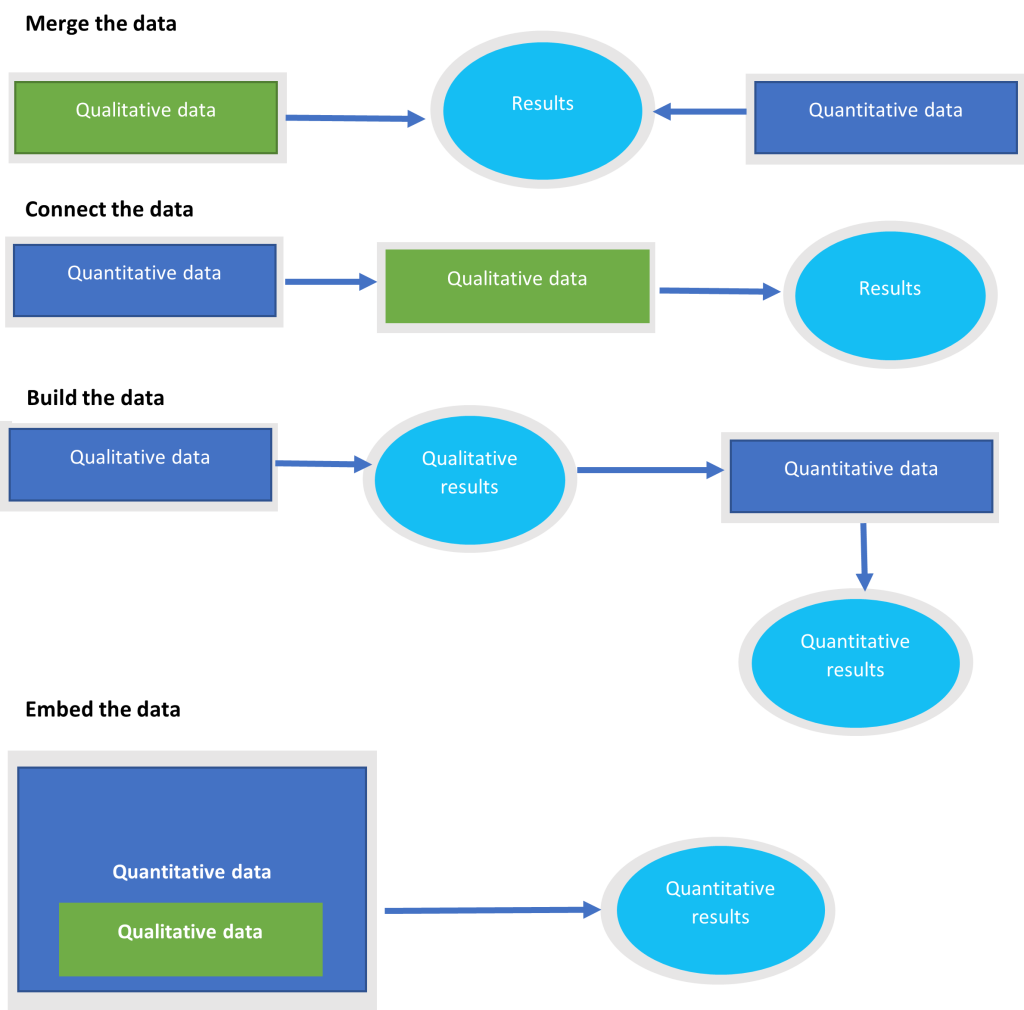

Methodological Triangulation

Methodological triangulation involves using multiple research methods to investigate a research question or phenomenon. This can include both qualitative and quantitative methods, or different types of qualitative methods, such as focus groups and interviews. By using multiple methods, researchers can strengthen their findings, as well as gain a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

Theoretical Triangulation

Theoretical triangulation involves using multiple theoretical frameworks or perspectives to analyze and interpret research findings. This can include applying different theoretical models or approaches to the same data to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. The use of multiple theories can also help to validate findings and identify inconsistencies.

Investigator Triangulation

Investigator triangulation involves using multiple researchers to examine a research question or phenomenon. This can include researchers with different backgrounds, expertise, and perspectives, to reduce the risk of bias and increase the validity of the findings. It can also help to validate the findings by having multiple researchers analyze and interpret the data.

Time Triangulation

Time triangulation involves studying the same phenomenon or research question at different time points. This can include longitudinal studies that track changes over time, or retrospective studies that examine the same phenomenon at different points in the past. Time triangulation can help to identify changes or patterns in the phenomenon, as well as validate findings over time.

Triangulation Methods

Triangulation is a research technique that involves using multiple methods, sources, or perspectives to validate or corroborate research findings. Here are some common triangulation methods used in research:

Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

Triangulating between qualitative and quantitative methods involves using both types of research methods to collect data and analyze the phenomenon under investigation. This can help to strengthen the validity and reliability of the findings by providing a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

Multiple Data Sources

Triangulating between multiple data sources involves collecting data from various sources to validate the findings. This can include using data from interviews, observations, surveys, or archival records to corroborate the findings.

Multiple Researchers

Triangulating between multiple researchers involves using multiple researchers to analyze and interpret the data. This can help to ensure the findings are not biased by the perspectives of a single researcher.

Triangulating Theories

Triangulating between theories involves using multiple theoretical frameworks to analyze and interpret the data. This can help to identify inconsistencies in the findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

Triangulating Methodologies

Triangulating between methodologies involves using multiple research methods within a single research design. For example, a study may use both qualitative and quantitative methods to investigate the same phenomenon, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

Triangulating Time

Triangulating between time involves studying the same phenomenon at different points in time. This can help to identify changes in the phenomenon over time and validate the findings across time.

Triangulating Participants

Triangulating between participants involves collecting data from multiple participants with different backgrounds, experiences, or perspectives. This can help to validate the findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

Data Collection Methods

Here are some common triangulation data collection methods used in research:

Interviews are a popular data collection method used in qualitative research. Researchers may use different types of interviews, such as structured, semi-structured, or unstructured interviews, to gather data from participants. Triangulating interviews involves conducting multiple interviews with different participants or conducting interviews with the same participants at different times to validate or corroborate the findings.

Observations

Observations involve systematically observing and recording behavior or interactions in a natural setting. Researchers may use different types of observations, such as participant observation, non-participant observation, or structured observation, to collect data. Triangulating observations involves collecting data from different observers or conducting observations at different times to validate or corroborate the findings.

Surveys involve collecting data from a large number of participants using standardized questionnaires. Researchers may use different types of surveys, such as self-administered surveys or telephone surveys, to collect data. Triangulating surveys involves collecting data from different surveys or using surveys in combination with other data collection methods to validate or corroborate the findings.

Document Analysis

Document analysis involves systematically analyzing and interpreting documents, such as government reports, policy documents, or archival records, to understand a phenomenon. Triangulating document analysis involves analyzing different types of documents or using document analysis in combination with other data collection methods to validate or corroborate the findings.

Focus Groups

Focus groups involve bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic or phenomenon. Researchers may use different types of focus groups, such as traditional focus groups or online focus groups, to collect data. Triangulating focus groups involves conducting multiple focus groups with different participants or conducting focus groups in combination with other data collection methods to validate or corroborate the findings.

Data Analysis Methods

Here are some common data analysis methods used in triangulation:

- Comparative analysis: Comparative analysis involves comparing data collected from different sources or methods to identify similarities and differences in the findings. This can help to identify patterns and relationships across the data and validate or corroborate the findings.

- Convergent validation: Convergent validation involves using different methods to collect data on the same phenomenon and comparing the findings to identify areas of convergence or agreement. This can help to increase the validity and reliability of the findings by providing multiple perspectives on the phenomenon.

- Divergent validation: Divergent validation involves using different methods to collect data on the same phenomenon and comparing the findings to identify areas of divergence or disagreement. This can help to identify inconsistencies in the findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

- Complementary analysis: Complementary analysis involves using different methods to collect data on different aspects of the same phenomenon and combining the findings to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. This can help to identify patterns and relationships across the data and provide a more complete picture of the phenomenon.

- Triangulated verification: Triangulated verification involves using multiple methods to verify the findings. This can involve using different data collection methods, data sources, or data analysis methods to validate or corroborate the findings.

- Meta-triangulation: Meta-triangulation involves using multiple studies or research designs to triangulate the findings. This can involve combining the findings from different studies or using multiple research designs to investigate the same phenomenon, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

- Member checking: Member checking involves validating the findings with the participants or stakeholders involved in the research. This can help to ensure the findings accurately reflect the experiences and perspectives of the participants and increase the credibility of the findings.

- Peer review: Peer review involves having other researchers or experts review the findings to ensure their validity and reliability. This can help to identify potential biases or errors in the data analysis and increase the credibility of the findings.

- Triangulated coding: Triangulated coding involves using different coding methods or approaches to analyze the data and identify themes or patterns. This can help to ensure the reliability and validity of the coding process and increase the credibility of the findings.

- Inter-rater reliability: Inter-rater reliability involves having multiple coders independently analyze the same data and comparing their findings to ensure consistency and agreement in the coding process. This can help to increase the reliability and validity of the findings.

How to Conduct Triangulation

Here are some general steps to conduct triangulation in research:

- Determine the research question: The first step in conducting triangulation is to determine the research question or objective. This will help to identify the types of data sources and methods needed to answer the research question.

- Select multiple data sources: Identify the multiple data sources that can be used to answer the research question. These sources may include primary data sources such as surveys, interviews, or observations, or secondary data sources such as literature reviews or existing datasets.

- Choose multiple data collection methods : Choose the multiple data collection methods that can be used to gather data from each data source. These methods may include quantitative and qualitative methods, such as surveys, focus groups, interviews, or observations.

- Collect data: Collect data from each data source using the selected data collection methods. Be sure to document the methods used to collect the data and any issues that arise during the data collection process.

- Analyze data: Analyze the data using appropriate data analysis methods. This may involve using different methods or approaches to analyze the data from each data source.

- Compare and contrast findings: Compare and contrast the findings from each data source to identify similarities and differences. This can help to validate or corroborate the findings and identify any inconsistencies or biases in the data.

- Synthesize findings: Synthesize the findings from each data source to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. This can involve identifying patterns or themes across the data and drawing conclusions based on the findings.

- Evaluate and report findings: Evaluate the validity and reliability of the findings and report the results in a clear and concise manner. Be sure to include a description of the triangulation process and the methods used to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

Applications of Triangulation

Here are some common applications of triangulation:

- Validating research findings: Triangulation can be used to validate research findings by using multiple methods, sources, or perspectives to corroborate the results. This can help to ensure that the findings are accurate and reliable and increase the credibility of the research.

- Exploring complex phenomena: Triangulation can be particularly useful when investigating complex or multifaceted phenomena that cannot be fully understood using a single method or perspective. By using multiple methods or sources, triangulation can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

- Enhancing data quality: Triangulation can help to enhance the quality of the data collected by identifying inconsistencies or biases in the data and providing multiple perspectives on the phenomenon. This can help to ensure that the data is accurate and reliable and increase the validity of the research.

- Providing richer data: Triangulation can provide richer and more detailed data by using multiple data collection methods or sources to capture different aspects of the phenomenon. This can provide a more complete picture of the phenomenon and help to identify patterns and relationships across the data.

- Enhancing the credibility of the research: Triangulation can enhance the credibility of the research by using multiple methods or sources to corroborate the findings and ensure their validity and reliability. This can increase the confidence that readers or stakeholders have in the research and its findings.

Examples of Triangulation

Here are some real-time examples of triangulation:

- Mixed-methods research : Mixed-methods research is a common example of triangulation that involves using both quantitative and qualitative research methods to collect and analyze data. This approach can help to validate or corroborate the findings by providing multiple perspectives on the same phenomenon.

- Clinical diagnosis : In medicine, triangulation can be used to diagnose complex or rare medical conditions. This can involve using multiple diagnostic tests, such as blood tests, imaging scans, and biopsies, to corroborate the diagnosis and ensure its accuracy.

- Market research : In market research, triangulation can be used to validate consumer preferences or opinions. This can involve using multiple data collection methods, such as surveys, focus groups, and interviews, to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Educational research: In educational research, triangulation can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of teaching methods. This can involve using multiple data sources, such as student test scores, classroom observations, and teacher interviews, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the teaching and learning process.

- Environmental research: In environmental research, triangulation can be used to evaluate the impact of human activities on the environment. This can involve using multiple data sources, such as satellite imagery, field observations, and interviews with local communities, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the environmental impacts.

Purpose of Triangulation

The purpose of triangulation in research is to increase the validity and reliability of the findings by using multiple data sources and methods to study the same phenomenon. Triangulation can help to mitigate the limitations of using a single data source or method and can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research question or objective.

By using multiple data sources and methods, triangulation can help to:

- Validate research findings: Triangulation can help to validate the findings by providing converging evidence from multiple data sources and methods. This can increase the credibility of the research and reduce the likelihood of drawing false conclusions.

- Enhance the completeness of data : Triangulation can help to enhance the completeness of data by providing multiple perspectives on the same phenomenon. This can help to capture the complexity and richness of the phenomenon and reduce the risk of bias or oversimplification.

- I dentify discrepancies and inconsistencies : Triangulation can help to identify discrepancies and inconsistencies in the data by comparing and contrasting the findings from multiple data sources and methods. This can help to identify areas of uncertainty or ambiguity and guide further investigation.

- Provide a more comprehensive understanding: Triangulation can help to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research question or objective by integrating data from multiple sources and methods. This can help to identify patterns or relationships that may not be apparent from a single data source or method.

When to use Triangulation

Here are some situations where triangulation may be appropriate:

- When the research question is complex: Triangulation may be appropriate when the research question is complex and requires a multifaceted approach. Using multiple data sources and methods can help to capture the complexity of the phenomenon under investigation.

- When the research is exploratory: Triangulation may be appropriate when the research is exploratory and aims to generate new insights or hypotheses. Using multiple data sources and methods can help to validate the findings and reduce the risk of drawing false conclusions.

- When the research is sensitive: Triangulation may be appropriate when the research is sensitive and requires a high level of rigor and validation. Using multiple data sources and methods can help to increase the credibility and rigor of the findings and reduce the likelihood of bias or error.

- When the research is interdisciplinary: Triangulation may be appropriate when the research is interdisciplinary and requires a range of expertise and methods. Using multiple data sources and methods can help to integrate different perspectives and approaches and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

- When the research is longitudinal : Triangulation may be appropriate when the research is longitudinal and aims to study changes over time. Using multiple data sources and methods can help to capture the changes and validate the findings across different time periods.

Advantages of Triangulation

Here are some advantages of using triangulation:

- Increased validity: Triangulation can help to increase the validity of research findings by providing converging evidence from multiple data sources and methods. This can help to reduce the risk of drawing false conclusions and increase the credibility of the research.

- Increased reliability: Triangulation can help to increase the reliability of research findings by reducing the likelihood of bias or error. By using multiple data sources and methods, triangulation can help to validate the findings and reduce the risk of drawing incorrect conclusions.

- Enhanced completeness of data: Triangulation can help to enhance the completeness of data by providing multiple perspectives on the same phenomenon. This can help to capture the complexity and richness of the phenomenon and reduce the risk of oversimplification.

- Better understanding of the phenomenon: Triangulation can help to provide a better understanding of the phenomenon under investigation by integrating data from multiple sources and methods. This can help to identify patterns or relationships that may not be apparent from a single data source or method.

- Increased confidence in the findings: Triangulation can help to increase the confidence in the research findings by providing multiple sources of evidence. This can help to reduce the risk of drawing false conclusions and increase the credibility of the research.

Limitations of Triangulation

Here are some limitations of using triangulation:

- Resource-intensive: Triangulation can be resource-intensive in terms of time, money, and personnel. Collecting and analyzing data from multiple sources and methods can require more resources than using a single data source or method.

- Increased complexity: Triangulation can increase the complexity of the research process by requiring researchers to integrate data from multiple sources and methods. This can make the analysis more challenging and time-consuming.

- Difficulty in comparing data: Triangulation can make it difficult to compare data collected from different sources and methods. The data may be collected using different measures or instruments, making it difficult to compare or combine the data.

- Data inconsistencies: Triangulation can also result in data inconsistencies if the data collected from different sources or methods are contradictory or conflicting. This can make it challenging to interpret the findings and draw meaningful conclusions.

- Interpretation issues: Triangulation can also create interpretation issues if the findings from different data sources or methods are not consistent or do not converge. This can lead to uncertainty or ambiguity in the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 28: Triangulation

Tess Tsindos

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the definition of triangulation.

- Describe the four types of triangulation.

- Understand how to conduct triangulation.

- Identify the strengths and limitations of triangulation.

What is triangulation?

Triangulation is the combination or blending of more than one participant group, researcher, theory and/or method in the same research. Its purpose is to understand the phenomenon under study 1 by determining consistency, or ‘truth’. 1 Triangulation can be used to demonstrate the rigour, validity and credibility of research findings. 2 While the purpose of triangulation is not to confirm results, but rather to understand differences, it can be difficult to explain inconsistent results when discussing the research undertaken.

There are four main types of triangulation 2 :

- T heoretical triangulation is the use of more than one theory to guide the research process. For example, a researcher might analyse data on family violence by applying feminist and critical theory, and they might also apply structural functionalist theory (see Section 1) when examining family violence as part of a complex system. By applying different theories, the data is able to be interrogated through theoretical lenses, which can lead to deeper understanding of the findings and greater nuance than a single theory might support.

- R esearcher triangulation is the use of multiple (two or more) researchers to collect and / or analyse data. The researchers may have different disciplinary backgrounds and experiences, and will also bring their professional and personal interpretations to the data. For example, research approaches to consumer and community involvement (or patient and public involvement) might advocate for patients to be involved in the analysis of data, to include patient perspectives in the interpretation of the data. In a study developing a ‘BroSupPORT’ portal and examining issues facing men with prostate cancer, 3 researchers found that health professionals were not sure that a Patient Reported Outcome comparator tool would be helpful in prompting health-seeking behaviour, but participants with prostate cancer welcomed such a tool. Focusing a patient lens on data in this study was important because it was able to highlight differences between perspectives of health professionals and patient participants. If only health professionals had been consulted the tool would not have been considered helpful and would have been ruled out as an option for the portal.

- Methodological triangulation is the use of multiple (two or more) methods to collect and analyse data . The data collection methods might include focus groups, interviews, photovoice, observations, field notes and more. In essence, it is bringing together the various methods used to collect data and can provide a more nuanced explanation of results. Methodological triangulation can include quantitative methods to support or harmonise results. Using quantitative and qualitative methods together enables the research to answer the questions of ‘what’ and ‘why’ (see Chapter 11: Mixed Methods). The BroSupPort portal study 3 is a good example of methodological triangulation because it used a combination of workshops, interviews and focus groups to collect data.

- Data triangulation uses more than one data source and / or method of analysis to interrogate the data. Data sources may include interviews with people in a range of roles in an organisation, rather than only those in one particular role. Data analyses might include data from both inductive and deductive perspectives. Data triangulation might also include different data sources, such as qualitative (e.g. interviews) and quantitative (e.g. surveys). In the BroSupPORT portal study 3 data were gathered at workshops, focus groups and interviews. Surveys, mind maps, River of Life activities and problem trees (in printed form), along with field notes taken at each workshop, were used to collect data. A range of techniques was used to analyse the data including, but not limited to, descriptive content analysis.

Table 28.1 provides examples of the four main types of triangulation. Other types of triangulation, such as ‘time’ and ‘space’ 3 , are not covered in this chapter because they are used less often.

Table 28.1: Examples of triangulation

How to conduct triangulation.

How triangulation is conducted depends on the type of triangulation.

- Theoretical triangulation requires an introduction to each theory and can be written as a literature review. The theories are described and then compared, to elicit inferences that will form the basis of data interpretation. For example, a feminist theory will inform data collection in such a way that girls and women (and women’s marginalised groups) will be deliberately sought out and included in the research study. Analysis would include a focus on gender identity, patriarchal oppression, diversity of culture and background, and would seek to demonstrate women’s points of view through a feminist lens. If, for example, a study is about women patients, the data collection and analysis would focus on how or whether women are represented in the data, and how women are medically treated by healthcare practitioners. Women’s own perspectives would be sought and analysed, to understand their perspectives.

- Researcher triangulation is often described in the type of data being analysed, and can often be read in the researcher’s statement of positionality or in the reflexivity section of a journal paper or report 9 . Some forms of thematic analysis (not reflexive thematic analysis) requires more than one investigator to read, re-read, code and re-code interviews or focus groups. When it is not a requirement of the method of analysis, triangulation should still be considered, in order to address concerns about the rigour, validity and credibility of findings of a single researcher. Including more than one researcher and participant can leads to greater divergence and the potential for nuanced findings.

- Methodological triangulation is used often in the literature. A decision is made about how to conduct the research, on the basis of the research question or aim. Often in mixed methods research, a qualitative component seeks to answer the question, ‘Why?’ and the quantitative component seeks to test a hypothesis or answer the question, ‘What?’. However, many qualitative methods might be included, such as interviews, focus groups, newspaper clippings, to answer the research question(s). When using methodological triangulation, the researcher is looking to expand their understanding of the findings. For example, if a survey and interviews are the mixed methods used in a study, the researcher would seek to compare and contrast the findings of both methods, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon, and then would describe how the findings support or diverge in answering the research question(s). Thus, a study exploring barriers and enablers in the implementation of the 6-PACK falls prevention program 10 incorporated a cluster randomised control trial, economic and program evaluations, and surveys and focus groups. The findings were triangulated and results suggested that regular, practical face-to-face education and training for nurses were key to successful falls prevention program implementation in acute hospitals, as were provision of equipment; audit, reminders and feedback; leadership and champions; and the provision of falls data .

- Data triangulation involves using and analysing more than one participant group. It is often considered an aspect of methodological triangulation because different methods usually involve more than one source of data. Data collection needs to be well-defined and conducted. Once the data from all participant groups has been examined, the findings are compared and contrasted to assist in answering the research question(s).

It’s important to remember that triangulation can involve more than one type of triangulation, and this is often the case with mixed-methods research. For example, in mixed-methods research, methodological, investigator and data triangulation may be used to demonstrate the full findings of the research. While Table 28.1 has listed each type separately, examining some of the example papers will show that there is more than one type of triangulation in the studies. Strict adherence to only one triangulation type can make researching the phenomenon more difficult.

Advantages and challenges of triangulation

Comparing and contrasting theories, data sources, methods and data analyses can ensure strong reliability and validity in research results. However, this can also be time-consuming and resource-intensive. Attention needs to be paid to the nuances of the research, to provide holistic explanations. There are times when triangulation may not be considered necessary, and this also needs to be understood when addressing the research question. For example, if the purpose of the research is to develop a new theory, there may be no need to include more than one method, data point or theoretical foundation.

Triangulation is the use of more than one data source, investigator, theory or method in the same research. There are four main triangulation types: each provides a means for examining the research from different perspectives and for ensuring the rigour, validity and credibility of findings.

- Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Sciences Research . 1999:34, 1189-1208.

- Denzin NK. Sociological Methods: A Source Book (2nd ed). Mcgraw-Hill: 1978.

- Shemesh B et al. Codesigning a patient support portal with health professionals and men with prostate cancer: an action research study. Health Expect . 2022:25, 1319-1331. doi /10.1111/hex.13444

- Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research M ethods in E ducation . Routledge; 2017.

- Yeh A, Trang P. Avicii’s S.O.S.: a psychobiographical approach and corpus-based discourse analysis on suicidal ideation. Psychology of Language and Communication . 2022;26(1):207-241. doi.10.2478/plc-2022-0010

- Lundell S, Pesola U et al . Groping around in the dark for adequate COPD management: a qualitative study on experiences in long-term care. BMC Health Serv Res . 2020;20:1025. doi . 10.1186/s12913-020-05875-2

- McCrone L & Kingsbury M. Combining worlds: a mixed method for understanding learning spaces. Int J Qual Methods . 2023;22. doi : 10.1177/16094069231173781

- Johnson M, O’Hara R et al Multiple triangulation and collaborative research using qualitative methods to explore decision making in pre-hospital emergency care. BMC Med Res Methodol . 2017;17 ( 11). doi : 10.1186/s12874-017-0290-z

- Llewellyn-Beardsley J et al “Nothing’s changed, baby”: how the mental health narratives of people with multiple and complex needs disrupt the recovery framework. SSM – Ment Health. 2023;3(100221). doi : 10.1016/j.ssmmh.2023.100221

- Ayton D et al. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of the 6-PACK falls prevention program: pre-implementation study in hospitals participating in a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLOS ONE . 2017;12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171932

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners Copyright © 2023 by Tess Tsindos is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Triangulation in Research | Guide, Types, Examples

Published on 8 April 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 16 January 2023.

Triangulation in research means using multiple datasets, methods, theories and/or investigators to address a research question . It’s a research strategy that can help you enhance the validity and credibility of your findings.

Triangulation is mainly used in qualitative research , but it’s also commonly applied in quantitative research . If you decide on mixed methods research , you’ll always use methodological triangulation.

- Qualitative research: You conduct in-depth interviews with different groups of stakeholders, such as parents, teachers, and children.

- Quantitative research: You run an eye-tracking experiment and involve three researchers in analysing the data.

- Mixed methods research: You conduct a quantitative survey, followed by a few (qualitative) structured interviews.

Table of contents

Types of triangulation in research, what is the purpose of triangulation, pros and cons of triangulation in research, frequently asked questions about triangulation.

There are four main types of triangulation:

- Data triangulation: Using data from different times, spaces, and people

- Investigator triangulation: Involving multiple researchers in collecting or analysing data

- Theory triangulation: Using varying theoretical perspectives in your research

- Methodological triangulation : Using different methodologies to approach the same topic

We’ll walk you through the four types of triangulation using an example. This example is based on a real study .

Methodological triangulation

When you use methodological triangulation, you use different methods to approach the same research question.

This is the most common type of triangulation, and researchers often combine qualitative and quantitative research methods in a single study.

Methodological triangulation is useful because you avoid the flaws and research bias that come with reliance on a single research technique.

Data triangulation

In data triangulation, you use multiple data sources to answer your research question. You can vary your data collection across time, space, or different people.

When you collect data from different samples, places, or times, your results are more likely to be generalisable to other situations.

Investigator triangulation

With investigator triangulation, you involve multiple observers or researchers to collect, process, or analyse data separately.

Investigator triangulation helps you reduce the risk of observer bias and other experimenter biases.

Theory triangulation

Triangulating theory means applying several different theoretical frameworks in your research instead of approaching a research question from just one theoretical perspective.

- People cooperate for a sense of reward: they cooperate to feel good.

- People cooperate to avoid guilt: they cooperate to avoid feeling bad.

Testing competing hypotheses is one way to perform theory triangulation. Using theory triangulation may help you understand a research problem from different perspectives or reconcile contradictions in your data.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Researchers use triangulation for a more holistic perspective on a specific research question. Triangulation is also helpful for enhancing credibility and validity.

To cross-check evidence

It’s important to gather high-quality data for rigorous research. When you have data from only one source or investigator, it may be difficult to say whether the data are trustworthy.

But if data from multiple sources or investigators line up, you can be more certain of their credibility.

Credibility is about how confident you can be that your findings reflect reality. The more your data converge, or or agree with each other, the more credible your results will be.

For a complete picture

Triangulation helps you get a more complete understanding of your research problem.

When you rely on only one data source, methodology, or investigator, you may risk bias in your research. Observer bias may occur when there’s only one researcher collecting data. Similarly, using just one methodology means you may be disadvantaged by the inherent flaws and limitations of that method.

- Behavioral observations from a lab setting

- Self-report survey data from participants reflecting on their daily lives

- Neural data from an fMRI scanner during a cooperative task

It’s helpful to use triangulation when you want to capture the complexity of real-world phenomena. By varying your data sources, theories, and methodologies, you gain insights into the research problem from multiple perspectives and levels.

To enhance validity

Validity is about how accurately a method measures what it’s supposed to measure.

You can increase the validity of your research through triangulation. Since each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, you can combine complementary methods that account for each other’s limitations.

Finally, fMRI data can tell you more about hidden neural mechanisms without any participant interference. But this type of data is only valuable for your research when combined with the others.

Like all research strategies, triangulation has both advantages and disadvantages.

Reduces bias

Triangulating data, methods, investigators, or theories helps you avoid the bias that comes with using a single perspective in your research. You’ll get a well-rounded look into the research topic when you use triangulation.

Establishes credibility and validity

Combining different methods, data sources, and theories enhances the credibility and validity of your research. You’ll be able to trust that your data reflect real life more closely when you gather them using multiple perspectives and techniques.

Time-consuming

Triangulation can be very time-consuming and labour-intensive. You’ll need to juggle different datasets, sources, and methodologies to answer one research question.

This type of research often involves an interdisciplinary team and a higher cost and workload. You’ll need to weigh your options and strike a balance based on your time frame and research needs.

Inconsistency

Sometimes, the data from different sources, investigators, methods may not line up to give you a clear picture. Your data may be inconsistent or contradict each other.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that your research is incoherent. Rather, you’ll need to dig deeper to make sense of why your data are contradictory. These inconsistencies can be challenging but may also lead to new avenues for further research.

Triangulation in research means using multiple datasets, methods, theories and/or investigators to address a research question. It’s a research strategy that can help you enhance the validity and credibility of your findings.

Triangulation is mainly used in qualitative research , but it’s also commonly applied in quantitative research . Mixed methods research always uses triangulation.

There are four main types of triangulation :

- Data triangulation : Using data from different times, spaces, and people

- Investigator triangulation : Involving multiple researchers in collecting or analysing data

- Theory triangulation : Using varying theoretical perspectives in your research

Triangulation can help:

- Reduce bias that comes from using a single method, theory, or investigator

- Enhance validity by approaching the same topic with different tools

- Establish credibility by giving you a complete picture of the research problem

But triangulation can also pose problems:

- It’s time-consuming and labour-intensive, often involving an interdisciplinary team.

- Your results may be inconsistent or even contradictory.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, January 16). Triangulation in Research | Guide, Types, Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/triangulation-in-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, mixed methods research | definition, guide, & examples, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, what is qualitative research | methods & examples.

- Member Benefits

- Communities

- Grants and Scholarships

- Student Nurse Resources

- Member Directory

- Course Login

- Professional Development

- Institutions Hub

- ONS Course Catalog

- ONS Book Catalog

- ONS Oncology Nurse Orientation Program™

- Account Settings

- Help Center

- Print Membership Card

- Print NCPD Certificate

- Verify Cardholder or Certificate Status

- Trouble finding what you need?

- Check our search tips.

- Oncology Nursing Forum

- Number 5 / September 2014

The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research

Nancy Carter

Denise Bryant-Lukosius

Alba DiCenso

Jennifer Blythe

Alan J. Neville

Triangulation refers to the use of multiple methods or data sources in qualitative research to develop a comprehensive understanding of phenomena (Patton, 1999). Triangulation also has been viewed as a qualitative research strategy to test validity through the convergence of information from different sources. Denzin (1978) and Patton (1999) identified four types of triangulation: (a) method triangulation, (b) investigator triangulation, (c) theory triangulation, and (d) data source triangulation. The current article will present the four types of triangulation followed by a discussion of the use of focus groups (FGs) and in-depth individual (IDI) interviews as an example of data source triangulation in qualitative inquiry.

Jump to a section

Related articles, systematic reviews, case study research methodology in nursing research, preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A review of qualitative data analysis practices in health education and health behavior research

Ilana g. raskind.

Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University 1518 Clifton Rd. NE, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA. [email protected]

Rachel C. Shelton

Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Dawn L. Comeau

Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Hannah L. F. Cooper

Derek m. griffith.

Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA

Michelle C. Kegler

Data analysis is one of the most important, yet least understood stages of the qualitative research process. Through rigorous analysis, data can illuminate the complexity of human behavior, inform interventions, and give voice to people’s lived experiences. While significant progress has been made in advancing the rigor of qualitative analysis, the process often remains nebulous. To better understand how our field conducts and reports qualitative analysis, we reviewed qualitative papers published in Health Education & Behavior between 2000–2015. Two independent reviewers abstracted information in the following categories: data management software, coding approach, analytic approach, indicators of trustworthiness, and reflexivity. Of the forty-eight (n=48) articles identified, the majority (n=31) reported using qualitative software to manage data. Double-coding transcripts was the most common coding method (n=23); however, nearly one-third of articles did not clearly describe the coding approach. Although terminology used to describe the analytic process varied widely, we identified four overarching trajectories common to most articles (n=37). Trajectories differed in their use of inductive and deductive coding approaches, formal coding templates, and rounds or levels of coding. Trajectories culminated in the iterative review of coded data to identify emergent themes. Few papers explicitly discussed trustworthiness or reflexivity. Member checks (n=9), triangulation of methods (n=8), and peer debriefing (n=7) were the most common. Variation in the type and depth of information provided poses challenges to assessing quality and enabling replication. Greater transparency and more intentional application of diverse analytic methods can advance the rigor and impact of qualitative research in our field.

Introduction

Data analysis is one of the most powerful, yet least understood stages of the qualitative research process. During this phase extensive fieldwork and illustrative data are transformed into substantive and actionable conclusions. In the field of health education and health behavior, rigorous data analysis can elucidate the complexity of human behavior, facilitate the development and implementation of impactful programs and interventions, and give voice to the lived experiences of inequity. While tremendous progress has been made in advancing the rigor of qualitative analysis, persistent misconceptions that such methods can be intuited rather than intentionally applied, coupled with inconsistent and vague reporting, continue to obscure the process ( Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014 ). In an era of public health grounded in evidence-based research and practice, rigorously conducting, documenting, and reporting qualitative analysis is critical for the generation of reliable and actionable knowledge.

There is no single “right” way to engage in qualitative analysis ( Saldana & Omasta, 2018 ). The guiding inquiry framework, research questions, participants, context, and type of data collected should all inform the choice of analytic method ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 ; Saldana & Omasta, 2018 ). While the diversity and flexibility of methods for analysis may put the qualitative researcher in a more innovative position than their quantitative counterparts ( Miles et al., 2014 ), it also makes rigorous application and transparent reporting even more important ( Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey, 2011 ). Unlike many forms of quantitative analysis, qualitative analytic methods are far less likely to have standardized, widely agreed upon definitions and procedures ( Miles et al., 2014 ). The phrase thematic analysis , for example, may capture a variety of approaches and methodological tools, limiting the reader’s ability to accurately assess the rigor and credibility of the research. An explicit description of how data were condensed, patterns identified, and interpretations substantiated is likely of much greater use in assessing quality and facilitating replication. Yet, despite increased attention to the systematization of qualitative research ( Levitt et al., 2018 ; O’Brien et al., 2014 ; Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007 ), many studies remain vague in their reporting of how the researcher moved from “1,000 pages of field notes to the final conclusions” ( Miles et al., 2014 ).

Reflecting on the relevance of qualitative methods to the field of health education and health behavior, and challenges still facing the paradigm, we were interested in understanding how our field conducts and reports qualitative data analysis. In a companion paper ( Kegler et al. 2018 ), we describe our wider review of qualitative articles published in Health Education & Behavior ( HE&B ) from 2000 to 2015, broadly focused on how qualitative inquiry frameworks inform study design and study implementation. Upon conducting our initial review, we discovered that our method for abstracting information related to data analysis—documenting the labels researchers applied to analytic methods—shed little light on the concrete details of their analytic processes. As a result, we conducted a second round of review focused on how analytic approaches and techniques were applied. In particular, we assessed data preparation and management, approaches to data coding, analytic trajectories, methods for assessing credibility and trustworthiness, and approaches to reflexivity. Our objective was to develop a greater understanding of how our field engages in qualitative data analysis, and identify opportunities for strengthening our collective methodological toolbox.

Our methods are described in detail in a companion paper ( Kegler et al. 2018 ). Briefly, eligible articles were published in HE&B between 2000 and 2015 and used qualitative research methods. We excluded mixed methods studies because of differences in underlying paradigms, study design, and methods for analysis and interpretation. We reviewed 48 papers using an abstraction form designed to assess 10 main topics: qualitative inquiry framework, sampling strategy, data collection methods, data management software, coding approach, analytic approach, reporting of results, use of theory, indicators of trustworthiness, and reflexivity. The present paper reports results on data management software, coding approach, analytic approach, indicators of trustworthiness, and reflexivity.

Each article was initially double-coded by a team of six researchers, with one member of each coding pair reviewing the completed abstraction forms and noting discrepancies. This coder fixed discrepancies that could be easily resolved by re-reviewing the full text (e.g. sample size); a third coder reviewed more challenging discrepancies, which were then discussed with a member of the coding pair until consensus was reached. Data were entered into an Access database, and queries were generated to summarize results for each topic. Preliminary results were shared with all co-authors for review, and then discussed as a group.

New topics of interest emerged from the first round of review regarding how analytic approaches and techniques were applied. Two of the authors conducted a second round of review focused on: use of software, how authors discussed achieving coding consensus, use of matrices, analytic references cited, variation in how authors used the terms code and theme , and identification of common analytic trajectories, including how themes were identified, and the process of grouping themes or concepts. To facilitate the second round of review, the analysis section of each article was excerpted into a single document. One reviewer populated a spreadsheet with text from each article pertinent to the aforementioned categories, and summarized the content within each category. These results informed the development of a formal abstraction form. Two reviewers independently completed an abstraction form for each article’s analysis section and met to resolve discrepancies. For three of the categories (use of the terms code and theme; how themes were identified; and the process of grouping themes or concepts), we do not report counts or percentages because the level of detail provided was often insufficient to determine with certainty whether a particular strategy or combination of strategies was used.

Data preparation and management

We examined several dimensions of the data preparation and management process ( Table 1 ). The vast majority of papers (87.5%) used verbatim transcripts as the primary data source. Most others used detailed written summaries of interviews or a combination of transcripts and written summaries (14.6%). We documented whether qualitative software was mentioned and which packages were most commonly used. Fourteen of the articles used Atlas.ti (29.2%) and another seventeen (35.4%) did not report using software. NVivo and its predecessor NUD-IST were somewhat common (20.8%), and Ethnograph was used in two articles. Several other software packages were mentioned in one of the papers (e.g. AnSWR, EthnoNotes). Of those reporting use of a software package, the most common use, in addition to the implied management of data, was to code transcripts (33.3%). Approximately 10.4% described using the software to generate code reports, and 8.3% described using the software to calculate inter-rater reliability. Two articles (4.2%) described using the software to draft memos or data summaries. The remainder did not provide detail on how the software was used (16.7%).

Approaches to data preparation and management in qualitative papers, Health Education & Behavior 2000-2015 (n=48)

Note . Percentages may sum to >100 due to the use of multiple approaches

Data coding and analysis

Coding and consensus.

Double coding of all transcripts was most common by far (47.9%), although a significant proportion of papers did not discuss their approach to coding or the description provided was unclear (31.3%) ( Table 2 ). Among the remaining papers, approaches included a single coder with a second analyst reviewing the codes (8.3%), a single coder only (6.3%), and double coding of a portion of the transcripts with single coding of the rest (6.3%). A related issue is how consensus was achieved among coders. Approximately two-thirds (64.6%) of articles discussed their process for reaching consensus. Most described reaching consensus on definitions of codes or coding of text units through discussions (43.8%), while some mentioned the use of an additional reviewer to resolve discrepancies (8.3%).

Approaches to data coding and analysis in qualitative papers, Health Education & Behavior 2000-2015 (n=48)

Analytic approaches named by authors

As reported in our companion paper, thematic analysis (22.9%), content analysis (20.8%), and grounded theory (16.7%) were most commonly named analytic approaches. Approximately 43.8% named an approach that was not reported by other authors, including inductive analysis, immersion/crystallization, issue focused analysis, and editing qualitative methodology. Approximately 20% of the articles reported using matrices during analysis; most described using them to compare codes or themes across cases or demographic groups (14.6%).

We also examined which references authors cited to support their analytic approach. Although editions varied over time, the most commonly cited references included: Miles and Huberman (1984 , 1994 ); Bernard (1994 , 2002 , 2005 ), Bernard & Ryan (2010) , or Ryan & Bernard (2000 , 2003 ); Patton (1987 , 1990 , 1999 , 2002 ); and Strauss & Corbin (1994 , 1998 ) or Corbin & Strauss (1990) . These authors were cited in over five papers. Other references cited in 3–5 papers included: Lincoln and Guba (1985) or Guba (1978) ; Krueger (1994 , 1998 ) or Krueger & Casey (2000) ; Creswell (1998 , 2003 , 2007 ); and Charmaz (2000 , 2006 ).

Terminology: codes and themes

Given the diversity of definitions for the terms code and theme in the qualitative literature, we were interested in exploring how authors applied and distinguished the terms in their analyses. In over half of the articles, either both terms were not used, or the level of detail provided did not allow for clear categorization of how they were used. In the remainder of articles, we observed two general patterns: 1) the terms being used interchangeably and 2) themes emerging from codes.

Common analytic trajectories

In addition to examining various aspects of the analytic process as outlined above, we attempted to identify common overarching analytic trajectories or pathways. Authors generally used two approaches to indexing or breaking down and labeling the data (i.e., coding). The first approach (Pathways 1 and 2) was to create an initial list of codes based on theory, the literature, research questions, or the interview guide. The second approach (Pathways 3 and 4) was to read through transcripts to generate initial codes or patterns inductively. This approach was often labeled ‘open-coding’ or described as ‘making margin notes’ or ‘memoing’. We were unable to categorize 11 articles (22.9%) into one of the above pathways because the analysis followed a different trajectory (10.4%) or there was not enough detail reported (12.5%).

Those studies that began with initial or ‘start codes’ generally followed two pathways. The first (Pathway 1; 14.6%) was to code the data using the initial codes and then conduct a second round of coding within the ‘top level’ codes, often using open-coding to allow for identification of emergent themes. The second (Pathway 2; 18.8%) was to fully code the transcripts with the initial codes while simultaneously identifying emerging codes and modifying code definitions as needed. Those that did not start with an initial list of codes similarly followed two pathways. The first (Pathway 3; 33.3%) was to develop a formal coding template after open-coding (e.g., code transcripts in full with an iterative relabeling and creation of sub-codes) and the second (Pathway 4; 10.4%) was to use the initial codes generated from inductively reading the transcripts as the primary analytic step.

From all pathways, several approaches were used to identify themes: group discussions of salient themes, comparisons of coded data to develop or refine themes, combining related codes into themes, or extracting themes from codes. A small number of articles discussed or implied that themes or concepts were further grouped into broader categories or classes. However, the limited details provided by the authors made it difficult to ascertain the process used.

Validity, Trustworthiness, and Credibility

Few papers explicitly discussed techniques used to strengthen validity ( Table 3 ). Maxwell (1996) defines qualitative validity as “the correctness or credibility of a description, conclusion, explanation, interpretation, or other sort of account.” Member checks (18.8%; soliciting feedback on the credibility of the findings from members of the group from whom data were collected ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 )) and triangulation of methods (16.7%; assessing the consistency of findings across different data collection methods ( Patton, 2015 )) were the techniques reported most commonly. Peer debriefing (14.6%; external review of findings by a person familiar with the topic of study ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 )), prolonged engagement at a research site (10.4%), and analyst triangulation (10.4%; using multiple analysts to review and interpret findings ( Patton, 2015 )) were also reported. Triangulation of sources (assessing the consistency of findings across data sources within the same method ( Patton, 2015 )), audit trails (maintaining records of all steps taken throughout the research process to enable external auditing ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 )), and analysis of negative cases (examining cases that contradict or do not support emergent patterns and refining interpretations accordingly ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 )) were each mentioned only a few times. Lack of generalizability was discussed frequently, and was often a focus of the limitations section. Another commonly discussed threat to validity was an inability to draw conclusions about a construct or a domain of a construct because the sample was not diverse enough or because the number of participants in particular subgroups was too small. No papers discussed limitations to the completeness and accuracy of the data.

Approaches to establishing credibility, trustworthiness, and reflexivity in qualitative papers, Health Education & Behavior 2000-2015 (n=48)

Reflexivity

Reflexivity relates to the recognition that the perspective and position of the researcher shapes every step of the research process ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 ; Patton, 2015 ). Of the papers we reviewed, only four (8.3%) fully described the personal characteristics of the interviewers/facilitators (e.g. gender, occupation, training; Table 3 ). The majority (62.5%) provided minimal information about the interviewers (e.g. title or position), and 14 authors (29.2%) did not provide any information about personal characteristics. The vast majority of papers (87.5%) did not discuss the relationship and extent of interaction between interviewers/facilitators and participants. Only two papers explicitly discussed reflexivity, positionality, or potential personal bias based on the position of the researcher(s).

The present study sought to examine how the field of health education and health behavior has conducted and reported qualitative analysis over the past 15 years. We found great variation in the type and depth of analytic information reported. Although we were able to identify several broad analysis trajectories, the terminology used to describe the approaches varied widely, and the analytic techniques used were not described in great detail.

While the majority of articles reported whether data were double-coded, single-coded, or a combination thereof, additional detail on the coding method was infrequently provided. Saldaña (2016) describes two primary sets of coding methods that can be used in various combination: foundational first cycle codes (e.g. In Vivo, descriptive, open, structural), and conceptual second cycle codes (e.g. focused, pattern, theoretical). Each coding method possesses a unique set of strengths and can be used either solo or in tandem, depending upon the analytic objectives. For example, In Vivo codes, drawn verbatim from participant language and placed in quotes, are particularly useful for identifying and prioritizing participant voices and perspectives ( Saldana, 2016 ). Greater familiarity with, and more intentional application of, available techniques is likely to strengthen future research and accurately capture the ‘emic’ perspective of study participants.

Similarly, less than one quarter of studies described the use of matrices to organize coded data and support the identification of patterns, themes, and relationships. Matrices and other visual displays are widely discussed in the qualitative literature as an important organizing tool and stage in the analytic process ( Miles et al., 2014 ; Saldana & Omasta, 2018 ). They support the analyst in processing large quantities of data and drawing credible conclusions, tasks which are challenging for the brain to complete when the text is in extended form (i.e. coded transcripts) ( Miles et al., 2014 ). Like coding methods, myriad techniques exist for formulating matrices, which can be used for meeting various analytic objectives such as exploring specific variables, describing variability in findings, examining change across time, and explaining causal pathways ( Miles et al., 2014 ). Most qualitative software packages have extended capabilities in the construction of matrices and other visual displays.

Most authors reflected on their findings as a whole in article discussion sections. However, explicit descriptions of how themes or concepts were grouped together or related to one another—made into something greater than the sum of their parts—were rare. Miles et al. (2014) describe two tactics for systematically understanding the data as a whole: building a logical chain of evidence that describes how themes are causally linked to one another, and making conceptual coherence by aligning these themes with more generalized constructs that can be placed in a broader theoretical framework. Only one study in our review described the development of theory; while not a required outcome of analysis, moving from the identification of themes and patterns to such “higher-level abstraction” is what enables a study to transcend the particulars of the research project and draw more widely applicable conclusions ( Hennink et al., 2011 ; Saldana & Omasta, 2018 ).