10 Key Characteristics, Origin, Types And Classification Of A Biography

We explain what a biography is, its origin and how this writing is classified. Also, what are its features, extension and more.

What is a Biography?

Origin of the term biography, genre of the biography, biography background.

biography types

- Authorized. The one that has the approval of the biographer or his heirs and executors, that is, the one that has survived a certain process of censorship.

- Unauthorized. That written without approval and revision of the biographed character or his heirs.

- False. It is known as false autobiography or false biography to works of fiction that pretend to be biographical writings.

Delimitation of the biography

Objectivity of the biography

Biographical approach.

biographical novelty

Biography extension.

Biography Value

Kalum Talbot

MA student of the TransAtlantic Masters program at UNC-Chapel Hill. Political Science with a focus on European Studies. Expressed ideas are open to revision. He not only covers Technical articles but also has skills in the fields of SEO, graphics, web development and coding. .

Leave a reply

Social media, entertainment, recent post.

Sport: What Is It, Types, Risks, Features, Characteristics and Examples

Dogs: Emergence, Features, Characteristics, Feeding and Breeds

Story: Definition, Elements, Structure, Features and Characteristics

Essay: Definition, Structure, Features, Characteristics, How to Do It

Narrative Text: What It Is, Structure, Features, Characteristics and Examples

The Elements of a Biography: How to Write an Interesting Bio

- March 30, 2022

While these books are generally non-fiction, they may include elements of a biography in order to more accurately reflect the nature of the subject’s life and personality, Writing about someone who actually existed, whether it’s a family member, close friend, famous person, or historical figure, involves certain elements. A person’s life story is being told, and the subject’s life needs to be organized in such a way that the reader is interested and engaged.

Biographies can easily read as boring announcements of only a human’s accomplishments in life, and if you want the bio you write to stand out, you should try to avoid that.

When you’re writing a biography or even a short professional bio, ask yourself what sorts of things you’d like included if someone was writing your biography.

You would most likely want people to get a feel of who you were as a person, and to be able to understand the way that you felt, what moved and motivated you, and what changes you wanted to see and make in the world.

Do the same thing when you write about someone else. Do the subject the favor of treating them like a real person instead of a stiff and boring character that students will dread having to learn about at school each year. Getting students excited about history, historical figures, and people of interest can inspire them to work hard to make a difference as well.

What Does Biographical Mean?

The term “biographical” is an adjective that means having the characteristics of a biography or constituting a set of personal information or details. For instance, biographical notes contain information about a specific person’s life or narrate stories and experiences of that person. Another example is biographical details . Biographical details include who the person is, what they have become, what they have struggled with, and any other information unique to them.

Keep It Real

Don’t fictionalize the life of the person you are writing about, but remember your sense of humanity when you write, and do what you can to make sure that your subject can be viewed as a real person who existed, rather than just a name on a monument.

It’s a thin line between rumor, speculation, and fact when telling the stories of people, especially people who are long dead and can’t verify or refute it for themselves. Be sure that if you do research and something is speculated, you state that in your writing.

Never claim something is fact when it’s isn’t a known and proven fact. This will cause you to lose credibility as a nonfiction writer.

What to Include in a Biography

When you read or write a biography, most of them have the same basic details of a person’s life. The person’s date of birth, date of death, and the major accomplishments and key events in between those two dates are all important to include in the writing process. These are elements that need to exist within the story of the person to be considered a full biography.

Keep in mind that these are the minimum elements that need to be included. Expanding on these elements and adding meat to the bones of your story will engage readers.

If you only include important dates and accomplishments, you might as well direct the reader to visit the headstone of the person you are writing about, and they’ll get almost as much information.

Personal details offer a more intimate look into the subject’s life and can help the reader to relate or at least understand some of the decisions made by the person, as well as the influences that played a part in steering the person’s life.

If the subject had any passions that he or she voiced throughout his or her life, mentioning those in your story of their life will elevate your biography.

Relevant Information

Family members are often mentioned in biography and major details of the person’s career. If the person was known for their accomplishments in their field of work, there is often more content there than a brief career summary.

The result is usually more of a professional bio than a personal one. Basic facts of the person’s education are often mentioned as well. If you are writing a biography about someone, try to remember to write about more than just their job.

Remember that you aren’t writing a resume, and the subject isn’t asking you to help them get a job. You are tasked with writing about the entire life of someone. You are more than your job, so the subject of the biography you are writing should get to be more, as well.

Personal Information

Biographies don’t have to be boring. Personal stories, interesting stories, and funny quips are sometimes used to make the readers identify with the subject.

When included in a biography, these details give the reader a chance to feel as though the subject was a real person with opinions, feelings, flaws, and a personality, rather than a stuffy person who is significant to history and not much else.

Providing the audience with these lighthearted but not necessarily crucial elements of a biography will make the biography more interesting and appealing.

Narrator and Order

Point of view.

An important element in most biographies is establishing the point of view. You don’t want to write it like a novel and have it written in a first-person point of view. This will result in something that is somewhat fictionalized and something that more closely resembles an autobiography, which is the personal story of a person’s own life.

Biographies should be written in the third person point of view. In third person, someone outside of the story, who has all of the information, is the narrator.

Try not to be biased. Stick to the basic facts, major events that you have researched, and keep the story interesting but accurate. A biography is not meant to be a fictional adventure, but the subject’s life was significant in some manner, and the details of that can still be interesting.

Chronological Order

Biographies usually begin, well, in the beginning, at the birth of the subject. The first sentence usually includes the basic information that a reader needs to know: who the person is, where the person is from, and when the person was born. A biography that doesn’t include these details but starts at the most important life events can exist, but they aren’t common. You may see this tactic used in a short biography or a brief bio.

Usually, chronological order is the best course of action for a biography. A person’s life begins in childhood, so details of that childhood, even briefly, are necessary before getting to the subject’s adult life.

Describing the subject’s early life to the audience usually means you should research and write about the family they came from, their early education, what kind of student the person was, where they came from, any close bonds they had as children with people.

As well as their interests and whether or not they pursued the life they ended up with as an adult, or if greatness and accomplishments were thrust upon them by events outside of their control.

As you progress into a subject’s adult life, you should add achievements to the biography. Focus not only on the major achievements as acts but also try to fill the audience in on what the motivation for the achievements was.

For example, Abraham Lincoln was the sixteenth President of the United States. That’s a well-known fact. Students learn about him in American grade schools and then over and over until their educational careers are over. In a bio about Lincoln, you may discuss the fact that Lincoln freed the slaves.

While this is true, you need to research deeper into that. Just stating that a person did something doesn’t make it an interesting read. Ask yourself why he freed the slaves.

Do your research, speak to an expert, and search for journals and letters that a subject might have written to describe how they felt to the audience and how they drove the person to do what they did.

Focus on the Impact the Person’s Life Had

After you have gone over the person’s life in the biography, you should share with readers what impact the subject’s life had on the rest of the world, even (sometimes especially) after their death. Many of the important people in history who have biographies written about them are deceased.

When you write a biography, ask yourself why anyone cares what that person accomplished. What did they do for one or two people to make them important enough to have a biography?

For example, many students learn about George Washington. He gave America the sense of hope and patriotism that they needed to declare and then achieve freedom from English rule.

When we search for information about Washington, we find not only his bio and his painted picture, but we also see and learn about the things he influenced, inspired, and the feelings he invoked among the people around him.

When we give a well-rounded look at not only what the person did in their lives, but how they changed the world, even just for those around them, we start to see the bigger picture and appreciate the person more.

Students can go from being bored and obligated to reading sentence after sentence about a boring guy who lived hundreds of years ago to being excited to learn more about the founding fathers. As a writer, it is your job to inspire these feelings for the reader.

When you write a biography, it’s important that you thoroughly research and fact-check everything you are writing about. Everyone knows that Lincoln freed the slaves, but you should still research it to ensure that everything is accurate as far as dates, places, speeches, and motivations go.

Make sure that you are getting your information from reputable resources. If you are interviewing live people, be sure to verify their credentials and use a tape recorder when doing so.

A biography is not an opinion piece or a novel, and there is no room for error, miscalculation, or falsification when you write a biography.

Actor Bio Example

An actor’s bio tells about the details of a specific person with regard to a person’s acting career. Below is an example. ( This example is created to serve as a guide for you and does not describe an actual person .)

Edgar Anderson and his family reside in Washington. He is currently taking up a Business Management course and striving to achieve a balance between schooling and his career. Edgar first experienced acting when he was still a junior high school student in 2015, where he played Horton in a Seussical-inspired school theater play. His manager discovered him in 2018 when the former watched him portray the lead role in a play about the history of their school during the school’s Foundation Day.

In 2022, he got his first nomination for best actor at the Oscars. Recently, Edgar has found a new set of hobbies. He enjoys learning karate and foreign languages. Edgar often thanks his family and friends because they have fully supported him in his acting career. He also extends his gratitude to the directors he has worked with and the talent agency that has helped him ascend the ladder of his career.

He dedicates his early success to all who have believed in him over the years. According to Edger, he loves his career even more because of the overflowing love and support he continually receives from his fans and loved ones.

The Importance of a Biography

It is important to include all of the elements of a biography because a biography is the story of a person’s life, and that’s a big undertaking. The subject is often no longer alive and can’t dispute what we write about them, so we have to get the information right and do the best we can when writing.

Students work on writing biographies and research papers about people in school so that they can learn more about the people who helped us get to where we are today in terms of society.

We teach students the skills and elements of a biography so that the practice of telling the story of a person’s life never gets lost. We need to focus on the future, but we cannot do that without understanding the past.

Other people may one day come along and write your bio, and when that happens, you have to hope that the first step they take is to do the research thoroughly so that they can do your story justice. That is what we owe the person we are writing about when we start to search for information about them.

Be respectful of the biography because it is the telling of those who came before us and can serve as a guidebook for the future or even a warning.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Sign up to our newsletter!

Related articles

120 Motivational Quotes About Writing To Inspire A New Writer Like You

How To Register A Kindle On Amazon To Enjoy Your Ebooks In 4 Easy Ways

How To Market A Self-Published Book And Be Profitable In 9 Easy Ways

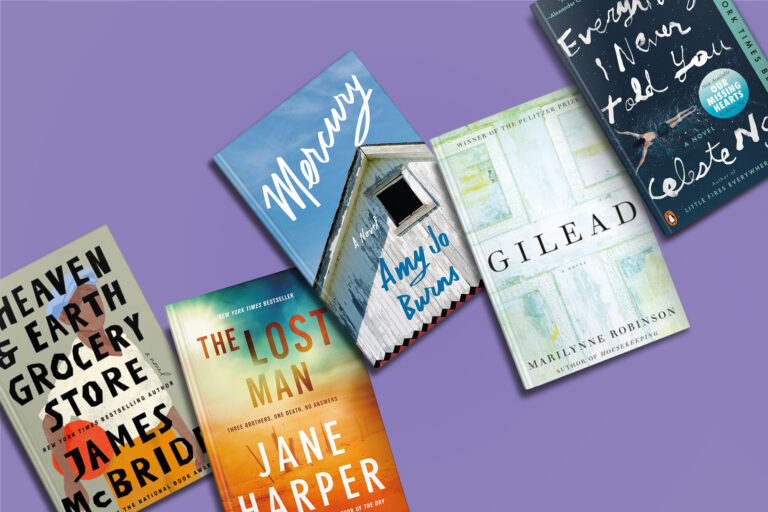

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- How to Invest

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Best Biographies » Historical Biographies

Browse book recommendations:

Best Biographies

- Ancient Biographies

- Artists' Biographies

- Group Biographies

- Literary Biographies

- Scientific Biographies

When you want to find out more about a historical or political figure, a biography is a great place to start. We have interviews dedicated to the best five books on historical figures —which can include primary sources, or books that focus on specific aspects of their life or legacy, as well as the story of their lives—but in this section, we have also included biographies of historical/political figures who don't yet have a dedicated interview on our site.

Best Spartacus biography Best Alexander the Great books Best Margaret Thatcher biography Best Joan of Arc biography Best books on Winston Churchill Best books on Elizabeth I Best Karl Marx Biography Best Eleanor of Aquitaine biography Best Isabella de' Medici biography The best books on Napoleon Bonaparte The best biography of Otto von Bismarck Best Catherine the Great biography The best books on Adolf Hitler The best Franco biography Best Books on Charles de Gaulle Best Florence Nightingale biography

Best books on Mahatma Gandhi Best Mao biography Best Indira Gandhi biography Best Aung San Suu Kyi biography (from 2011) Best Dalai Lama biography

Best Akhenaten biography Best Hatshepsut biography Best Haile Selassie biography Best books on Nelson Mandela Best Steve Biko biography

Best George Washington biography Best Martin Luther King biography Best Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt biography Best Sitting Bull biography Best Rachel Carson biography Best Amelia Earhart biography Best Frederick Douglass biography Best John F Kennedy biography (though this only covers the earlier years) Best Che Guevara biography Best Eva Peron biography Best Lula biography (from 2008)

The best books on Winston Churchill , recommended by Richard Toye

My early life 1874-1904 by winston churchill, churchill and the islamic world: orientalism, empire and diplomacy in the middle east by warren dockter, in command of history: churchill fighting and writing the second world war by david reynolds, churchill and the dardanelles by christopher m bell, winston churchill as i knew him by violet bonham carter.

Winston Churchill’s role as a global statesman remains immensely controversial. For some he was the heroic champion of liberty, saviour of the free world; for others a callous imperialist with a doleful legacy. Here, historian Richard Toye chooses the best books to help you understand the man behind the myths and Churchill's own role in making those myths.

Winston Churchill’s role as a global statesman remains immensely controversial. For some he was the heroic champion of liberty, saviour of the free world; for others a callous imperialist with a doleful legacy. Here, historian Richard Toye chooses the best books to help you understand the man behind the myths and Churchill’s own role in making those myths.

The Best Thomas Cromwell Books , recommended by Benedict King

Thomas cromwell: a life by diarmaid macculloch, the tudor constitution: documents and commentary by g r elton, the reformation parliament 1529-1536 by stanford e lehmberg, henry viii: the quest for fame by john guy, london and the reformation by susan brigden.

The Mirror and the Light— the final instalment of Hilary Mantel's epic trilogy covering the life of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister and architect of the English Reformation—was published to great acclaim this month. Here, Five Books contributing editor Benedict King chooses five of the best books to help you get to grips with the real Thomas Cromwell and the political and religious environment in which he operated. You can watch Benedict talking about his Thomas Cromwell book choices here.

The Mirror and the Light— the final instalment of Hilary Mantel’s epic trilogy covering the life of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister and architect of the English Reformation—was published to great acclaim this month. Here, Five Books contributing editor Benedict King chooses five of the best books to help you get to grips with the real Thomas Cromwell and the political and religious environment in which he operated. You can watch Benedict talking about his Thomas Cromwell book choices here.

The best books on Alexander the Great , recommended by Hugh Bowden

Alexander the great: the anabasis and the indica by arrian, the history of alexander by quintus curtius rufus, the first european: a history of alexander in the age of empire by pierre briant, the persian empire: a corpus of sources from the achaemenid period by amélie kuhrt, fire from heaven by mary renault.

Alexander the Great never lost a battle and established an empire that stretched from the Mediterranean to the Indian subcontinent. From the earliest times, historians have argued about the nature of his achievements and what his failings were, both as a man and as a political leader. Here, Hugh Bowden , professor of ancient history at King's College London, chooses five books to help you understand the controversies, the man behind the legends, and why the legends have taken the forms they have.

Alexander the Great never lost a battle and established an empire that stretched from the Mediterranean to the Indian subcontinent. From the earliest times, historians have argued about the nature of his achievements and what his failings were, both as a man and as a political leader. Here, Hugh Bowden , professor of ancient history at King’s College London, chooses five books to help you understand the controversies, the man behind the legends, and why the legends have taken the forms they have.

The best books on Napoleon , recommended by Andrew Roberts

The campaigns of napoleon by david g chandler, talleyrand by duff cooper, with eagles to glory: napoleon and his german allies in the 1809 campaign by john h gill, private memoirs of the court of napoleon by louis françois joseph bausset-roquefort, with napoleon in russia: memoirs of general de caulaincourt, duke of vicenza by armand de caulaincourt.

How did Napoleon Bonaparte, an upstart Corsican, go on to conquer half of Europe in the 16 years of his rule? Was he a military genius? And was he really that short? Historian Andrew Roberts , author of a bestselling biography of Napoleon , introduces us to the books that shaped how he sees l'Empereur —including little-known sources from those who knew Napoleon personally. Read more history book recommendations on Five Books

How did Napoleon Bonaparte, an upstart Corsican, go on to conquer half of Europe in the 16 years of his rule? Was he a military genius? And was he really that short? Historian Andrew Roberts, author of a bestselling biography of Napoleon , introduces us to the books that shaped how he sees l’Empereur —including little-known sources from those who knew Napoleon personally. Read more history book recommendations on Five Books

The best books on Gandhi , recommended by Ramachandra Guha

My days with gandhi by nirmal kumar bose, a week with gandhi by louis fischer, mahatma gandhi: nonviolent power in action by dennis dalton, gandhi's religion: a homespun shawl by j. t. f. jordens, harilal gandhi: a life by chandulal bhagubhai.

Gandhi's peaceful resistance to British rule changed India and inspired freedom movements around the globe. But as well as being an inspiring leader, Gandhi was also a human being. Ramachandra Guha , author of a new two-part biography of Gandhi, introduces us to books that give a fuller picture of the man who came to be known as 'Mahatma' Gandhi.

Gandhi’s peaceful resistance to British rule changed India and inspired freedom movements around the globe. But as well as being an inspiring leader, Gandhi was also a human being. Ramachandra Guha, author of a new two-part biography of Gandhi, introduces us to books that give a fuller picture of the man who came to be known as ‘Mahatma’ Gandhi.

The best books on Marx and Marxism , recommended by Terrell Carver

Karl marx by isaiah berlin, karl marx: his life and thought by david mclellan, karl marx's theory of history by g. a. cohen, the young karl marx by david leopold, karl marx: a nineteenth-century life by jonathan sperber.

Few people have had their ideas reinvented as many times as the German intellectual and political activist, Karl Marx. Professor of political theory, Terrell Carver , takes us through the most influential books, in English, about Marx, Marxism and his friend, publicist and financial backer, Friedrich Engels.

Few people have had their ideas reinvented as many times as the German intellectual and political activist, Karl Marx. Professor of political theory, Terrell Carver, takes us through the most influential books, in English, about Marx, Marxism and his friend, publicist and financial backer, Friedrich Engels.

The best books on British Prime Ministers , recommended by Anthony Seldon

Baldwin by keith middlemas and john barnes, lloyd george by john grigg, winston s churchill by martin gilbert, supermac by dr thorpe, margaret thatcher by john campbell.

It's their frailty that makes politicians such interesting characters, says Tony Blair's biographer Anthony Seldon . He tells us about the art of political biography and the writers who've best captured leaders such as Churchill and Thatcher

It’s their frailty that makes politicians such interesting characters, says Tony Blair’s biographer Anthony Seldon. He tells us about the art of political biography and the writers who’ve best captured leaders such as Churchill and Thatcher

The best books on The Kennedys , recommended by David Nasaw

Hostage to fortune: the letters of joseph p. kennedy by amanda smith (editor), conversations with kennedy by benjamin c. bradlee, robert kennedy and his times by arthur m. schlesinger, jr., jfk: reckless youth by nigel hamilton, true compass by edward m. kennedy.

The story and tragedy of the Kennedys is so incredible you don't need to turn to fiction, says the biographer of Joseph P Kennedy, David Nasaw . He talks us through the Kennedy generations.

The story and tragedy of the Kennedys is so incredible you don’t need to turn to fiction, says the biographer of Joseph P Kennedy, David Nasaw. He talks us through the Kennedy generations.

The best books on Hitler , recommended by Michael Burleigh

The fuehrer by konrad heiden, hitler’s vienna by brigitte hamann, hitler: the fuhrer and the people by j p stern, the hitler myth by ian kershaw, hitler by joachim fest.

Hitler has a reputation as the incarnation of evil. But, as British historian Michael Burleigh points out in selecting the best books on the German dictator, Hitler was a bizarre and strangely empty character who never did a proper day's work in his life, as well as a raving fantasist on to whom Germans were able to project their longings.

Hitler has a reputation as the incarnation of evil. But, as British historian Michael Burleigh points out in selecting the best books on the German dictator, Hitler was a bizarre and strangely empty character who never did a proper day’s work in his life, as well as a raving fantasist on to whom Germans were able to project their longings.

The best books on The French Resistance , recommended by Jonathan Fenby

Churchill and de gaulle by françois kersaudy, assignment to catastrophe by edward spears, the resistance by matthew cobb, l’armée des ombres (army of shadows) by jean-pierre melville, bad faith: a history of family and fatherland by carmen callil.

The historian and author chooses five books on de Gaulle and the Resistance. He says the British tried to veto de Gaulle’s famous 1940 speech from London calling on the French to stand up to German occupation

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

What Is a Biography?

Learning from the experiences of others is what makes us human.

At the core of every biography is the story of someone’s humanity. While biographies come in many sub-genres, the one thing they all have in common is loyalty to the facts, as they’re available at the time. Here’s how we define biography, a look at its origins, and some popular types.

“Biography” Definition

A biography is simply the story of a real person’s life. It could be about a person who is still alive, someone who lived centuries ago, someone who is globally famous, an unsung hero forgotten by history, or even a unique group of people. The facts of their life, from birth to death (or the present day of the author), are included with life-changing moments often taking center stage. The author usually points to the subject’s childhood, coming-of-age events, relationships, failures, and successes in order to create a well-rounded description of her subject.

Biographies require a great deal of research. Sources of information could be as direct as an interview with the subject providing their own interpretation of their life’s events. When writing about people who are no longer with us, biographers look for primary sources left behind by the subject and, if possible, interviews with friends or family. Historical biographers may also include accounts from other experts who have studied their subject.

The biographer’s ultimate goal is to recreate the world their subject lived in and describe how they functioned within it. Did they change their world? Did their world change them? Did they transcend the time in which they lived? Why or why not? And how? These universal life lessons are what make biographies such a meaningful read.

Origins of the Biography

Greco-Roman literature honored the gods as well as notable mortals. Whether winning or losing, their behaviors were to be copied or seen as cautionary tales. One of the earliest examples written exclusively about humans is Plutarch’s Parallel Lives (probably early 2 nd century AD). It’s a collection of biographies in which a pair of men, one Greek and one Roman, are compared and held up as either a good or bad example to follow.

In the Middle Ages, Einhard’s The Life of Charlemagne (around 817 AD) stands out as one of the most famous biographies of its day. Einhard clearly fawns over Charlemagne’s accomplishments throughout, yet it doesn’t diminish the value this biography has brought to centuries of historians since its writing.

Considered the earliest modern biography, The Life of Samuel Johnson (1791) by James Boswell looks like the biographies we know today. Boswell conducted interviews, performed years of research, and created a compelling narrative of his subject.

The genre evolves as the 20th century arrives, and with it the first World War. The 1920s saw a boom in autobiographies in response. Robert Graves’ Good-Bye to All That (1929) is a coming-of age story set amid the absurdity of war and its aftermath. That same year, Mahatma Gandhi wrote The Story of My Experiments with Truth , recalling how the events of his life led him to develop his theories of nonviolent rebellion. In this time, celebrity tell-alls also emerged as a popular form of entertainment. With the horrors of World War II and the explosion of the civil rights movement, American biographers of the late 20 th century had much to archive. Instantly hailed as some of the best writing about the war, John Hersey’s Hiroshima (1946) tells the stories of six people who lived through those world-altering days. Alex Haley wrote the as-told-to The Autobiography of Malcom X (1965). Yet with biographies, the more things change, the more they stay the same. One theme that persists is a biographer’s desire to cast its subject in an updated light, as in Eleanor and Hick: The Love Affair that Shaped a First Lady by Susan Quinn (2016).

Types of Biographies

Contemporary Biography: Authorized or Unauthorized

The typical modern biography tells the life of someone still alive, or who has recently passed. Sometimes these are authorized — written with permission or input from the subject or their family — like Dave Itzkoff’s intimate look at the life and career of Robin Williams, Robin . Unauthorized biographies of living people run the risk of being controversial. Kitty Kelley’s infamous His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra so angered Sinatra, he tried to prevent its publication.

Historical Biography

The wild success of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton is proof that our interest in historical biography is as strong as ever. Miranda was inspired to write the musical after reading Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton , an epic 800+ page biography intended to cement Hamilton’s status as a great American. Paula Gunn Allen also sets the record straight on another misunderstood historical figure with Pocahontas: Medicine Woman, Spy, Entrepreneur, Diplomat , revealing details about her tribe, her family, and her relationship with John Smith that are usually missing from other accounts. Historical biographies also give the spotlight to people who died without ever getting the recognition they deserved, such as The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks .

Biography of a Group

When a group of people share unique characteristics, they can be the topic of a collective biography. The earliest example of this is Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pirates (1724), which catalogs the lives of notorious pirates and establishes the popular culture images we still associate with them. Smaller groups are also deserving of a biography, as seen in David Hajdu’s Positively 4th Street , a mesmerizing behind-the-scenes look at the early years of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña as they establish the folk scene in New York City. Likewise, British royal family fashion is a vehicle for telling the life stories of four iconic royals – Queen Elizabeth II, Diana, Kate, and Meghan – in HRH: So Many Thoughts on Royal Style by style journalist Elizabeth Holmes.

Autobiography

This type of biography is written about one’s self, spanning an entire life up to the point of its writing. One of the earliest autobiographies is Saint Augustine’s The Confessions (400), in which his own experiences from childhood through his religious conversion are told in order to create a sweeping guide to life. Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings is the first of six autobiographies that share all the pain of her childhood and the long road that led to her work in the civil rights movement, and a beloved, prize-winning writer.

Memoirs are a type of autobiography, written about a specific but vital aspect of one’s life. In Toil & Trouble , Augusten Burroughs explains how he has lived his life as a witch. Mikel Jollett’s Hollywood Park recounts his early years spent in a cult, his family’s escape, and his rise to success with his band, The Airborne Toxic Event. Barack Obama’s first presidential memoir, A Promised Land , charts his path into politics and takes a deep dive into his first four years in office.

Fictional Biography

Fictional biographies are no substitute for a painstakingly researched scholarly biography, but they’re definitely meant to be more entertaining. Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Anne Fowler constructs Zelda and F. Scott’s wild, Jazz-Age life, told from Zelda’s point of view. The Only Woman in the Room by Marie Benedict brings readers into the secret life of Hollywood actress and wartime scientist, Hedy Lamarr. These imagined biographies, while often whimsical, still respect the form in that they depend heavily on facts when creating setting, plot, and characters.

Share with your friends

Related articles.

10 Evocative Literary Fiction Books Set in Small Towns

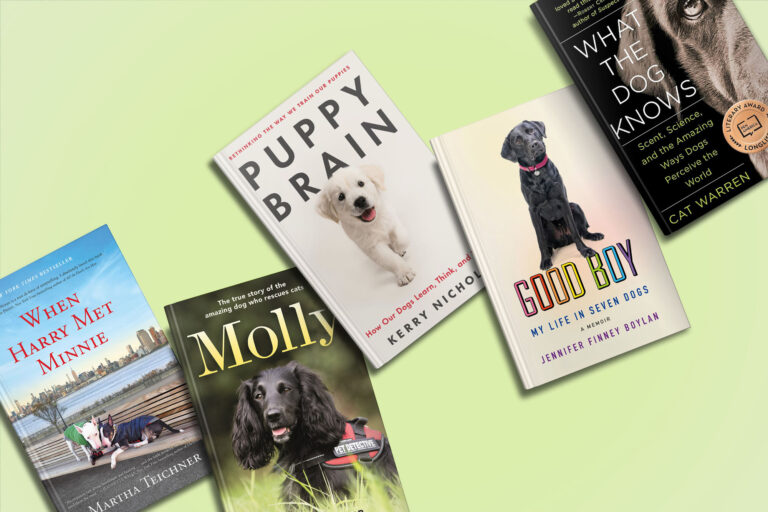

11 Must-Read Books About Dogs

What We’re Reading: Spring 2024

Celadon delivered.

Subscribe to get articles about writing, adding to your TBR pile, and simply content we feel is worth sharing. And yes, also sign up to be the first to hear about giveaways, our acquisitions, and exclusives!

" * " indicates required fields

Connect with

Sign up for our newsletter to see book giveaways, news, and more.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Policy

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Publish with Historical Research?

- About Historical Research

- About the Institute of Historical Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

History and biography.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Lawrence Goldman, History and biography, Historical Research , Volume 89, Issue 245, August 2016, Pages 399–411, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2281.12144

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article explores the relationship between historical and biographical writing. It looks at the way structural and individualized approaches to past events complement each other and also conflict on occasion by focusing on examples drawn from modern British and American history. Given as an inaugural lecture by the new Director of the Institute of Historical Research, it looks in turn at the contribution of the I.H.R. to the development of Tudor historiography; at the history and aims of the original Dictionary of National Biography and its successor, the Oxford D.N.B. , published in 2004; and at the advantages and disadvantages of a history of the modern welfare state written through the biographies of its founders, among them William Beveridge, William Temple and R. H. Tawney. On the American side, contrasting depictions of Abraham Lincoln by biographers and historians are compared and the limits of both structural and biographical approaches to the history of American slavery and of individual slave lives are considered. The article argues that the best historical research and the most readable history require both types of analysis, biographical as well as historical.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-2281

- Print ISSN 0950-3471

- Copyright © 2024 Institute of Historical Research

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Definition of Biography

A biography is the non- fiction , written history or account of a person’s life. Biographies are intended to give an objective portrayal of a person, written in the third person. Biographers collect information from the subject (if he/she is available), acquaintances of the subject, or in researching other sources such as reference material, experts, records, diaries, interviews, etc. Most biographers intend to present the life story of a person and establish the context of their story for the reader, whether in terms of history and/or the present day. In turn, the reader can be reasonably assured that the information presented about the biographical subject is as true and authentic as possible.

Biographies can be written about a person at any time, no matter if they are living or dead. However, there are limitations to biography as a literary device. Even if the subject is involved in the biographical process, the biographer is restricted in terms of access to the subject’s thoughts or feelings.

Biographical works typically include details of significant events that shape the life of the subject as well as information about their childhood, education, career, and relationships. Occasionally, a biography is made into another form of art such as a film or dramatic production. The musical production of “Hamilton” is an excellent example of a biographical work that has been turned into one of the most popular musical productions in Broadway history.

Common Examples of Biographical Subjects

Most people assume that the subject of a biography must be a person who is famous in some way. However, that’s not always the case. In general, biographical subjects tend to be interesting people who have pioneered something in their field of expertise or done something extraordinary for humanity. In addition, biographical subjects can be people who have experienced something unusual or heartbreaking, committed terrible acts, or who are especially gifted and/or talented.

As a literary device, biography is important because it allows readers to learn about someone’s story and history. This can be enlightening, inspiring, and meaningful in creating connections. Here are some common examples of biographical subjects:

- political leaders

- entrepreneurs

- historical figures

- serial killers

- notorious people

- political activists

- adventurers/explorers

- religious leaders

- military leaders

- cultural figures

Famous Examples of Biographical Works

The readership for biography tends to be those who enjoy learning about a certain person’s life or overall field related to the person. In addition, some readers enjoy the literary form of biography independent of the subject. Some biographical works become well-known due to either the person’s story or the way the work is written, gaining a readership of people who may not otherwise choose to read biography or are unfamiliar with its form.

Here are some famous examples of biographical works that are familiar to many readers outside of biography fans:

- Alexander Hamilton (Ron Chernow)

- Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder (Caroline Fraser)

- Steve Jobs (Walter Isaacson)

- Churchill: A Life (Martin Gilbert)

- The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (Simon Winchester)

- A Beautiful Mind (Sylvia Nasar)

- The Black Rose (Tananarive Due)

- John Adams (David McCullough)

- Into the Wild ( Jon Krakauer )

- John Brown (W.E.B. Du Bois)

- Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (Hayden Herrera)

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Rebecca Skloot)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (Doris Kearns Goodwin)

- Shirley Jackson : A Rather Haunted Life ( Ruth Franklin)

- the stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit (Michael Finkel)

Difference Between Biography, Autobiography, and Memoir

Biography, autobiography , and memoir are the three main forms used to tell the story of a person’s life. Though there are similarities between these forms, they have distinct differences in terms of the writing, style , and purpose.

A biography is an informational narrative and account of the life history of an individual person, written by someone who is not the subject of the biography. An autobiography is the story of an individual’s life, written by that individual. In general, an autobiography is presented chronologically with a focus on key events in the person’s life. Since the writer is the subject of an autobiography, it’s written in the first person and considered more subjective than objective, like a biography. In addition, autobiographies are often written late in the person’s life to present their life experiences, challenges, achievements, viewpoints, etc., across time.

Memoir refers to a written collection of a person’s significant memories, written by that person. Memoir doesn’t generally include biographical information or chronological events unless it’s relevant to the story being presented. The purpose of memoir is reflection and an intention to share a meaningful story as a means of creating an emotional connection with the reader. Memoirs are often presented in a narrative style that is both entertaining and thought-provoking.

Examples of Biography in Literature

An important subset of biography is literary biography. A literary biography applies biographical study and form to the lives of artists and writers. This poses some complications for writers of literary biographies in that they must balance the representation of the biographical subject, the artist or writer, as well as aspects of the subject’s literary works. This balance can be difficult to achieve in terms of judicious interpretation of biographical elements within an author’s literary work and consideration of the separate spheres of the artist and their art.

Literary biographies of artists and writers are among some of the most interesting biographical works. These biographies can also be very influential for readers, not only in terms of understanding the artist or writer’s personal story but the context of their work or literature as well. Here are some examples of well-known literary biographies:

Example 1: Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay (Nancy Milford)

One of the first things Vincent explained to Norma was that there was a certain freedom of language in the Village that mustn’t shock her. It wasn’t vulgar. ‘So we sat darning socks on Waverly Place and practiced the use of profanity as we stitched. Needle in, . Needle out, piss. Needle in, . Needle out, c. Until we were easy with the words.’

This passage reflects the way in which Milford is able to characterize St. Vincent Millay as a person interacting with her sister. Even avid readers of a writer’s work are often unaware of the artist’s private and personal natures, separate from their literature and art. Milford reflects the balance required on the part of a literary biographer of telling the writer’s life story without undermining or interfering with the meaning and understanding of the literature produced by the writer. Though biographical information can provide some influence and context for a writer’s literary subjects, style, and choices , there is a distinction between the fictional world created by a writer and the writer’s “real” world. However, a literary biographer can illuminate the writer’s story so that the reader of both the biography and the biographical subject’s literature finds greater meaning and significance.

Example 2: The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens (Claire Tomalin)

The season of domestic goodwill and festivity must have posed a problem to all good Victorian family men with more than one family to take care of, particularly when there were two lots of children to receive the demonstrations of paternal love.

Tomalin’s literary biography of Charles Dickens reveals the writer’s extramarital relationship with a woman named Nelly Ternan. Tomalin presents the complications that resulted for Dickens from this relationship in terms of his personal and family life as well as his professional writing and literary work. Revealing information such as an extramarital relationship can influence the way a reader may feel about the subject as a person, and in the case of literary biography it can influence the way readers feel about the subject’s literature as well. Artists and writers who are beloved , such as Charles Dickens, are often idealized by their devoted readers and society itself. However, as Tomalin’s biography of Dickens indicates, artists and writers are complicated and as subject to human failings as anyone else.

Example 3: Virginia Woolf (Hermione Lee)

‘A self that goes on changing is a self that goes on living’: so too with the biography of that self. And just as lives don’t stay still, so life-writing can’t be fixed and finalised. Our ideas are shifting about what can be said, our knowledge of human character is changing. The biographer has to pioneer, going ‘ahead of the rest of us, like the miner’s canary, testing the atmosphere , detecting falsity, unreality, and the presence of obsolete conventions’. So, ‘There are some stories which have to be retold by each generation’. She is talking about the story of Shelley, but she could be talking about her own life-story.

In this passage, Lee is able to demonstrate what her biographical subject, Virginia Woolf, felt about biography and a person telling their own or another person’s story. Literary biographies of well-known writers can be especially difficult to navigate in that both the author and biographical subject are writers, but completely separate and different people. As referenced in this passage by Lee, Woolf was aware of the subtleties and fluidity present in a person’s life which can be difficult to judiciously and effectively relay to a reader on the part of a biographer. In addition, Woolf offers insight into the fact that biographers must make choices in terms of what information is presented to the reader and the context in which it is offered, making them a “miner’s canary” as to how history will view and remember the biographical subject.

Post navigation

The 7 Characteristics of the Most Important Biographies

The Characteristics of good biographies Must be based on authenticity and honesty, should be objective when presenting the lives of subjects and trying to avoid stereotypes.

Biographies are narrative and expository texts whose function is to give an account of the life of a person. At the time of writing a biography, special care must be taken and be truthful throughout the text, since what is narrated are real facts that happened to an individual.

But this is not all, good biographies must present details of the person's life, such as his birth, his family, his education, his weaknesses and strengths, among others, to understand the course of this.

However, biographies can not simply be a list of events, since this would be a timeline.

In this sense, in the biographical texts must exist a thematic progression, which will allow to relate these events, giving meaning to the narration.

7 Main features of biographies

1- general topic: individual.

As stated above, biography is a narrative about a person's life. In this sense, the first thing to take into account when writing a biography is about who is going to be treated.

There is a great variety of subjects on which a biographical text can be written, from figures recognized worldwide, such as Elon Musk Or Marie Curie, to ourselves, which would be an autobiography.

2- Character of the subject

In the biographies, a description of the main elements that define the character of the subject must be included, since this description will allow the reader to understand the decisions that the subject took or the achievements that reached.

For example, if you do a biography about George Washington, you could mention that since he was young he was very mature and had a great sense of responsibility, elements that made him an outstanding military leader and a hero for the United States.

3- Limited theme: focus

Because a person's life has many stages and many events, biography can focus on only one facet of the person.

For example, if you make a biography about Stanislao Cannizzaro , Who was an Italian scientist, professor and politician, could focus the biographical text in only one of these facets, for example, that of the scientist, and thus develop the contributions that this gave to science.

This delimitation should be included in the thesis of the biography, which is in the introduction.

4- Language function: informative

The type of language that should be used in biographies is the referential or informative, since what is sought is to transmit information about the life of the individual studied.

5- Organization

Most biographies follow chronological order. Because it is a narrative about real events, beginning in the early years of life of the figure in question could provide details that facilitate the reader's understanding.

The chronological order can be divided into stages of life; For example: birth and childhood, adult life and death (in case the subject studied has died).

However, the organization of the text will depend on the needs of the author. Some of the most common non-chronological models are:

- By subjects that have affected the studied subject or phases that it has crossed. For example, a biography about the painter Pablo Picasso could focus on the periods of works of this: cubist, blue, pink, black, among others.

- By interviews: In this case, the data presented are obtained through interviews with people who knew, or know, the subject studied. In this sense, the biographical text will be a recount of the testimonies of the interviewees.

- In media res: This is a literary term that refers to the anachronistic order, in which analepsis (jumps in time into the past) and prolepsis (jumps in time into the future) are used.

This means that the text does not begin with the birth of the individual but at some point in the life of the individual, and from there"leaps"to past events, and then return to the point where the story began.

Stuart, A Life Backwards, by author Alexander Masters, is an example of this type of biography.

6- Recount of at least one relevant event in the person's life

The biography must include at least one event highlighting the life of the individual being studied; This will make the text interesting to the reader.

For example, if you make a biography about Antoine Lavoisier , One should speak of its discovery, the law of conservation of mass; If it is a biography about the scientist John Dalton , It would be appropriate to talk about the atomic theory raised by it and how it was influenced by the discoveries of other scientists of the time.

7- Veracity

The most important feature of a biography is that it must be truthful and precise, since it is about the life of a person.

In this sense, the sources of information must be carefully checked, to determine if what they transmit is true or not.

The best sources of information in these cases are autobiographies, books and letters written by the individual studied, interviews with the individual (in case he has not died) and interviews with other people who are related, or who have been related, With the individual.

- How to write a biography. Retrieved on May 9, 2017, from grammar.yourdictionary.com.

- How to write a biography (with examples). Retrieved on May 9, 2017, from wikihow.com.

- Narrative essay biographical essay. Retrieved on May 9, 2017, from phschool.com.

- Biography. Retrieved on May 9, 2017, from yourdictionary.com.

- How do you start a biography? Retrieved on May 9, 2017, from quora.com.

- Biography. Retrieved on May 9, 2017, from homeofbob.com.

- Characteristics of good biographies. Retrieved on May 9, 2017, from education.com.

Recent Posts

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Diaspora

- Afrocentrism

- Archaeology

- Central Africa

- Colonial Conquest and Rule

- Cultural History

- Early States and State Formation in Africa

- East Africa and Indian Ocean

- Economic History

- Historical Linguistics

- Historical Preservation and Cultural Heritage

- Historiography and Methods

- Image of Africa

- Intellectual History

- Invention of Tradition

- Language and History

- Legal History

- Medical History

- Military History

- North Africa and the Gulf

- Northeastern Africa

- Oral Traditions

- Political History

- Religious History

- Slavery and Slave Trade

- Social History

- Southern Africa

- West Africa

- Women’s History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

African biography and historiography.

- Heather Hughes Heather Hughes School of History and Heritage, University of Lincoln

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.229

- Published online: 28 August 2018

Biography in the African context can take many forms, from brief entries in a biographical dictionary or obituary in a newspaper to multivolume studies of single individuals. It can encompass one or many subjects and serves both to celebrate the famous and illuminate obscure lives. Biographies can be instructional as well as inspirational. Sometimes, it is hard to draw a line between biography and autobiography because of the way a work has been compiled. An attempt is made to understand this vast range of forms, with reference to social and political biography. The main focus is on work produced since the 1970s, with examples drawn from all regions of sub-Saharan Africa (although Southern Africa is better represented than others, as is English-medium material). Matters that preoccupy biographers everywhere, such as the relationship between writer and subject and the larger relationship between biography and history, are raised. Biography can be an excellent entry point into the complexities of African history.

- autobiography

- life history

- collective biography

- microbiography

- oral testimony

- Nelson Mandela

Writing Biographies of African Subjects

Since the 1970s, biography writing in an African context has come of age. In order to understand this phenomenon, it is necessary to trace the forms it has taken, as well as the themes and preoccupations it has been concerned with. 1 Explored here is the political significance of collective biography, from anthologies of relatively brief biographies (or microbiographies) to more extended treatments, such as the members of one family or representatives of a profession. Also addressed is the range of individuals who have attracted biographical attention, from the very famous such as Nelson Mandela, to the almost forgotten: iron smelters, sharecroppers, and migrant workers. Even within the restricted purview of social and political biography, a wealth of material has been published since the 1970s, of which only a small selection can be included. While an attempt has been made to draw examples from all regions of sub-Saharan Africa, a strong English-medium and southern African bias is evident.

There are some matters that preoccupy biographers everywhere, such as the relationship between writer and subject, not to mention the larger relationship between biography and history. These have a specific resonance in the African case. Indeed, students can enrich their appreciation of African history by sampling the range of biographies written about African subjects.

Each African country will have its own national register of leading citizens across all the fields of human endeavor: politics, education, religion, sport, the arts, health care, business and so on. Prominent individuals from these walks of life will also feature in newspaper obituaries, one of the most ubiquitous forms of the brief biography. In each country, there is probably also a thriving trade in biographical narratives, spoken and written, and in many different languages. Not all of this activity can be covered, as it is simply too widespread. It would also be highly instructive to investigate biography from the perspective of readers and listeners rather than writers. However, discussion is confined to an attempt to highlight key trends in the writing of biography, applicable across a number of regions and beyond the continent itself.

In the 1970s, a series of biographies appeared—three iterations in all—that provide a convenient framework for discussing biography and historiography in African settings. They first came out in the Nigerian historical journal Tarikh , under the editorship of Obaro Ikime. In 1974 , they were collected into a single volume, Leadership in 19th Century Africa , also edited by Ikime. 2 Between 1971 and 1977 , Ikime also oversaw the publication of a largely different selection of thirteen individual biographies. Apart from the fact that each was presented in a separate A5-size paperback, the format was similar to all the others. 3 Altogether, this represents a body of nearly thirty biographies that was widely used in school and college courses. Each section of the essay that follows takes this collective biographical venture as the starting point for further exploration of the nature of biography in Africa.

The Expansion of Biography

The timing of Ikime’s biographies is significant. This was a period of dramatic expansion of African history into university and college courses in Europe, North America, and across independent Africa. In the post–Second World War period, it was an area of inquiry that had to push its way in. Not only did proponents have to demonstrate to their peers that researching and teaching Africa’s past were legitimate scholarly activities, they also had to challenge a more pervasive mindset that clung to a notion of African inferiority and passivity. These biographies were self-consciously presented as a means of asserting African agency in the making of a rich and long history. It is what African American scholars have long called “race vindication.” 4 Ikime was explicit on this point: the 1974 collection was meant to demonstrate “the variety of types of leadership which Africa boasted even in a century which, until recently, used to be regarded as a century of European activity and African slumber.” 5

Moreover, there was something deliberate about the geographical spread of the biographies. Although revealing a strong West African orientation, every part of the continent was represented, from the Mediterranean littoral to the southeastern seaboard. The message was clear: that across this expanse was a sense of a shared past and a common experience. While the threatened loss of autonomy and subjugation to European rule was a critical moment in African history, it was but one element in a complex interplay of forces stretching further back in time, such as state building and the desire for modernization and reform.

This was a time when a Pan-Africanist view of an essential African unity seemed a vital ingredient of decolonization, not only of territory but also of minds. In more recent decades, the origins of this idea have been questioned. Kwame Anthony Appiah has, for example, argued that it was a product of the European (not the African) imagination that “the cultures and societies of sub-Saharan Africa formed a single continuum” before becoming so deeply embedded in African thought. 6

The Power of Collective Biography

There had long been a desire by educated, middle-class Africans and African Americans both to rescue from neglect and to highlight the talents, achievements, and autonomy of Africa’s people throughout its complex history; the vehicle of collective biography seemed entirely appropriate for this purpose. One remarkable example from the early 1930s is T. D. Mweli Skota’s The African Yearly Register, Being an Illustrated National Biographical Dictionary (Who’s Who) of Black Folks in Africa . 7 It includes sections on both the living and the late; in the latter particularly, it contains entries from every region of the African continent: the “national” in the title has a distinctly Pan-African flavor. It sought to convey a sense of determined survival in the face of adversity and how individuals were attempting to avoid a white world of oppression by following “progressive” callings such as traders, lawyers, and pastors in independent churches. Sadly, despite the promise of its title, it seems to have appeared only two or three times. Johannesburg-based Skota sorely lacked sponsorship at a time when segregationist rule was being applied ever more harshly and it proved impossible to sustain his biographical dictionary. 8

As early as the first decade of the 20th century , W. E. B. du Bois had been planning a collective biography along similar lines. 9 His ambition was delayed until 1962 , when Kwame Nkrumah invited him to an independent Ghana to realize the work, with the financial backing of the Ghana Academy of Sciences. Du Bois made clear his approach to compilation of his intended multivolume Encyclopaedia Africana : “While there should be included among its writers the best students of Africa in the world, I want the proposed Encyclopaedia to be written mainly from the African point of view by people who know and understand the history and culture of Africans.” 10 Already in his nineties Du Bois did not survive long enough to see his vision into print; the first volume eventually appeared in 1977 , followed by two more by 1995 . 11 In all, these covered some 650 individuals (the vast majority of whom were no longer alive) in eight countries. Yet another unrelated collective biography appeared in the 1970s, the Dictionary of African Historical Biography . 12 Its cut-off date was 1960 , thus serving once again to underline the depth and continuities of African history.

The 1990s saw the launch of a further large-scale biographical endeavor: the electronic/online Dictionary of African Christian Biography (DACB). Overseen by the Centre for Global Christianity and Mission at Boston University School of Theology, its purpose is to gather the biographical detail of those who have shaped the character and growth of Christianity in Africa. Foreign missionaries may have brought Christianity to Africa, but Africans have been the main agency in its propagation; the resulting growth and variety constitute remarkable social phenomena. The DACB is notable for its methodology and goals. Oral as well as written sources are represented; although mainly in English, it is multilingual and covers the earliest times onward, over the whole continent. It works in partnership with universities and theological colleges, many of them in Africa, and crowdsourcing is encouraged, despite its acknowledged challenges:

While scholarly exactitude marks some of the entries, a large number have been contributed by persons who are neither scholars nor historians. The stories are non-proprietary, belonging to the people of Africa as a whole. Since this is a first generation tool, and on the assumption that some memory is better than total amnesia, the checkered quality of the entries has been tolerated and even welcomed. 13

A recent addition to collective biography is the monumental Oxford Dictionary of African Biography (ODAB). 14 The editors, eminent scholars Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong and Henry Louis Gates, consciously place themselves in the tradition of Du Bois’s Encyclopaedia . In their preface, they claim for the ODAB

the most comprehensive continental coverage (including Africa north of the Sahara) available to date, a degree and depth of coverage that will dramatically increase our understanding of the lives and achievements of individual Africans who lived across the full range of continental Africa from ancient times to the present. The publication of such a reference work, we perceived, could have a transformative impact on teaching and research in African studies, narrating the full history of the African continent through the collective lives of the women and men who made that history. 15

The print edition contains over two thousand entries, while entries will continue to be added to the online edition, eventually totaling some ten thousand.

The quintessential form of collective biography is thus the biographical dictionary, presenting a number of microbiographies based on a common theme. Such themes might include eminence or belonging, which provide a criterion for appreciating the collection as a whole. 16 In the context of Africa, this form has been powerfully deployed as a practical expression of solidarity, a rejection of foreign oppression, a declaration of unity of purpose, an assertion of pride—nothing less, in sum, than a rehumanization of the subject.

Biography as Instruction

There is a further dimension of biography that threads its way from Ikime’s collection to the ODAB: a didactic/instructional purpose. Although intended for a wide readership, adult as well as child, Ikime’s biographies were envisioned as particularly suitable for classrooms. As such, they represent an attempt to produce patriotic historical narratives, showcasing real individuals whose achievements would instruct as well as inspire the young. All over the continent, the tradition of biographical series—inherently or explicitly collective, for both children and adults—has continued. Examples include the Kenyan Sasa Sema series, They Fought for Freedom series (mostly South African subjects), UNESCO’s series Women in African History, the Voices of Liberation series published by South Africa’s HSRC Press (South African and African figures) and the volume African Leaders of the Twentieth Century , a compilation of four titles from Ohio University Press’ Short Histories of Africa series. 17

The series Panaf Great Lives focused on leaders of liberation movements who supported the radical transformation of African society. Kwame Nkrumah had founded Panaf Books in 1968 , following the coup in Ghana and the refusal of his London publishers to handle his books thereafter. Panaf Books was based in London and managed by June Milne, who had been Nkrumah’s research assistant since the late 1950s. Its main business was to continue to publish and promote Nkrumah’s works. It also issued Panaf Great Lives, which were extended, anonymously-authored biographies cast in a heroic mold, of revolutionary leaders such as Eduardo Mondlane, Patrice Lumumba, Frantz Fanon, Sékou Touré, and Nkrumah himself. They appeared throughout the 1970s. 18 Nkrumah’s biography seems to have been the only one also to be published in the format of a schools edition. 19

Leaders and Followers, Men and Women

African biographies, according to one scholar, tend to be divided into two types: those about individuals deemed to be significant for some reason—the leaders—and those of “ordinary” people. 20 This may help to identify certain biographical characteristics, such as that leaders’ stories emphasize the exceptional and unusual, whereas those of the ordinary are assumed to be representative of many experiences: of slaves, peasants, urban workers, market women, or miners. Yet it also presents the difficulty of knowing where to draw the line between them, or to understand features they share in common; some “ordinary” lives turn out to be anything but. For this reason, it is preferable to place biographical stories along a continuum, from well-known to little-known subjects, rather than into either/or types.

The biographical subjects of Ikime’s collections were chosen for one quality: leadership. Many became kings or chiefs “in times of crisis . . . by appealing directly to the populace over the heads of the traditional king-maker class.” 21 Control over trade, not least in slaves, was often a vital ingredient. Most had to confront the pressures of colonial advances on their territories. Together, they demonstrated many creative responses to the challenges facing them. It was their public deeds that mattered and that had made them powerful, exemplary, or exceptional on the historical stage.

They were also all male; either there was insufficient knowledge at the time about women who had played significant leadership roles, or they had not been considered significant enough for inclusion. In any case, in the 1970s overwhelming maleness dominated scholarship, as well as understandings of African leadership. It took until 1984 for Heinemann, the publisher of one of Ikime’s series, to bring out a volume entitled Women Leaders in African History to redress this imbalance. 22 The most ancient of the twelve leaders featured was 15th-century bce Queen Hatshepsut of Egypt; the most recent was Nehanda of Zimbabwe, who lived toward the end of the 19th century . Like their male counterparts, they were somehow extraordinary, perhaps even doubly so, given the subjugation of women in many of the societies represented.

Herbert Macaulay’s story was alone among the Ikime biographies as someone who had risen to leadership by virtue of his Western education and involvement not in armed resistance to colonial rule but in the growth of nationalism as an oppositional force. Macaulay established the Nigeria National Democratic Party in the early 1920s and dominated Lagos politics for the following two decades. He is regarded by many as the founder of Nigerian nationalism. His solitude in the collections seems to suggest that it was conceptually difficult to fit “new Africans” into a historical framework that stressed continuity and indigenous response to change. 23 After all, they embraced a religion and politics that were considered profoundly disruptive , as they themselves knew all too well. As a young Aina Moore mused:

Opinions vary with regard to the status of the so-called ‘educated African’. While some regard him as the greatest enemy of his country, from which he becomes detached, and for which he can only develop a sophisticated form of patriotism: others look upon him as the means of creating a link between two different countries of such different culture, with both of which he is acquainted. 24

A 1979 addition to Heinemann’s African Historical Biographies series, Black Leaders in Southern African History slipped two further examples into a selection otherwise dominated by “traditional” leaders: Tiyo Soga, the first African to be ordained in South Africa, and John Tengo Jabavu, best known as a newspaper editor and politician. 25

Biographically speaking, “new Africans” seemed to fit better into a framework that privileged modernity over tradition and the promise of an independent future over the reassurance of a continuous past. Probably the most famous “new African” of the first half of the 20th century was James Emman Kwegyir Aggrey (b. 1875–d. 1927 ). Born in the Gold Coast (later Ghana) and educated by Wesleyan missionaries, Aggrey traveled to the United States to complete his education. He attended Hood Theological Seminary and later Columbia University, where his abilities as an educationist and communicator were recognized. He supported the stirrings of African nationalism but also distanced himself from anti-white hostility and even from Gandhi’s passive resistance campaigns. His stance was most likely responsible for the invitation to join the Phelps-Stokes Commission to Africa—he traveled widely on the continent, attracting huge attention everywhere—as well as for Edwin Smith’s biography, which appeared in 1929 . 26

Other in-depth biographies of prominent figures appeared before the notable expansion of the 1970s. Reflecting the long engagement of Europe with the southern tip of the continent were a number of biographies of white South African politicians, such as the voluminous studies of Jan Smuts (the anti-colonial rebel who became a world statesman) and those of leading liberals such as Saul Solomon and Jan Hofmeyr. 27