Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Case Presentation

Figure 1. Blue and silver stethoscope (Pixabay, N.D.)

Ms. S.W. is a 48-year-old white female who presented to an outpatient community mental health agency for evaluation of depressive symptoms. Over the past eight weeks she has experienced sad mood every day, which she describes as a feeling of hopelessness and emptiness. She also noticed other changes about herself, including decreased appetite, insomnia, fatigue, and poor ability to concentrate. The things that used to bring Ms. S.W. joy, such as gardening and listening to podcasts, are no longer bringing her the same happiness they used to. She became especially concerned as within the past two weeks she also started experiencing feelings of worthlessness, the perception that she is a burden to others, and fleeting thoughts of death/suicide.

Ms. S.W. acknowledges that she has numerous stressors in her life. She reports that her daughter’s grades have been steadily declining over the past two semesters and she is unsure if her daughter will be attending college anymore. Her relationship with her son is somewhat strained as she and his father are not on good terms and her son feels Ms. S.W. is at fault for this. She feels her career has been unfulfilling and though she’d like to go back to school, this isn’t possible given the family’s tight finances/the patient raising a family on a single income.

Ms. S.W. has experienced symptoms of depression previously, but she does not think the symptoms have ever been as severe as they are currently. She has taken antidepressants in the past and was generally adherent to them, but she believes that therapy was more helpful than the medications. She denies ever having history of manic or hypomanic episodes. She has been unable to connect to a mental health agency in several years due to lack of time and feeling that she could manage the symptoms on her own. She now feels that this is her last option and is looking for ongoing outpatient mental health treatment.

Past Medical History

- Hypertension, diagnosed at age 41

Past Surgical History

- Wisdom teeth extraction, age 22

Pertinent Family History

- Mother with history of Major Depressive Disorder, treated with antidepressants

- Maternal grandmother with history of Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Brother with history of suicide attempt and subsequent inpatient psychiatric hospitalization,

- Brother with history of Alcohol Use Disorder

- Father died from lung cancer (2012)

Pertinent Social History

- Works full-time as an enrollment specialist for Columbus City Schools since 2006

- Has two children, a daughter age 17 and a son age 14

- Divorced in 2015, currently single

- History of some emotional abuse and neglect from mother during childhood, otherwise denies history of trauma, including physical and sexual abuse

- Smoking 1/2 PPD of cigarettes

- Occasional alcohol use (approximately 1-2 glasses of wine 1-2 times weekly; patient had not had any alcohol consumption for the past year until two weeks ago)

Mental Health Case Study: Understanding Depression through a Real-life Example

Imagine feeling an unrelenting heaviness weighing down on your chest. Every breath becomes a struggle as a cloud of sadness engulfs your every thought. Your energy levels plummet, leaving you physically and emotionally drained. This is the reality for millions of people worldwide who suffer from depression, a complex and debilitating mental health condition.

Understanding depression is crucial in order to provide effective support and treatment for those affected. While textbooks and research papers provide valuable insights, sometimes the best way to truly comprehend the depths of this condition is through real-life case studies. These stories bring depression to life, shedding light on its impact on individuals and society as a whole.

In this article, we will delve into the world of mental health case studies, using a real-life example to explore the intricacies of depression. We will examine the symptoms, prevalence, and consequences of this all-encompassing condition. Furthermore, we will discuss the significance of case studies in mental health research, including their ability to provide detailed information about individual experiences and contribute to the development of treatment strategies.

Through an in-depth analysis of a selected case study, we will gain insight into the journey of an individual facing depression. We will explore their background, symptoms, and initial diagnosis. Additionally, we will examine the various treatment options available and assess the effectiveness of the chosen approach.

By delving into this real-life example, we will not only gain a better understanding of depression as a mental health condition, but we will also uncover valuable lessons that can aid in the treatment and support of those who are affected. So, let us embark on this enlightening journey, using the power of case studies to bring understanding and empathy to those who need it most.

Understanding Depression

Depression is a complex and multifaceted mental health condition that affects millions of people worldwide. To comprehend the impact of depression, it is essential to explore its defining characteristics, prevalence, and consequences on individuals and society as a whole.

Defining depression and its symptoms

Depression is more than just feeling sad or experiencing a low mood. It is a serious mental health disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a loss of interest in activities that were once enjoyable. Individuals with depression often experience a range of symptoms that can significantly impact their daily lives. These symptoms include:

1. Persistent feelings of sadness or emptiness. 2. Fatigue and decreased energy levels. 3. Significant changes in appetite and weight. 4. Difficulty concentrating or making decisions. 5. Insomnia or excessive sleep. 6. feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or hopelessness. 7. Loss of interest or pleasure in activities.

Exploring the prevalence of depression worldwide

Depression knows no boundaries and affects individuals from all walks of life. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 264 million people globally suffer from depression. This makes depression one of the most common mental health conditions worldwide. Additionally, the WHO highlights that depression is more prevalent among females than males.

The impact of depression is not limited to individuals alone. It also has significant social and economic consequences. Depression can lead to impaired productivity, increased healthcare costs, and strain on relationships, contributing to a significant burden on families, communities, and society at large.

The impact of depression on individuals and society

Depression can have a profound and debilitating impact on individuals’ lives, affecting their physical, emotional, and social well-being. The persistent sadness and loss of interest can lead to difficulties in maintaining relationships, pursuing education or careers, and engaging in daily activities. Furthermore, depression increases the risk of developing other mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorders or substance abuse.

On a societal level, depression poses numerous challenges. The economic burden of depression is significant, with costs associated with treatment, reduced productivity, and premature death. Moreover, the social stigma surrounding mental health can impede individuals from seeking help and accessing appropriate support systems.

Understanding the prevalence and consequences of depression is crucial for policymakers, healthcare professionals, and individuals alike. By recognizing the significant impact depression has on individuals and society, appropriate resources and interventions can be developed to mitigate its effects and improve the overall well-being of those affected.

The Significance of Case Studies in Mental Health Research

Case studies play a vital role in mental health research, providing valuable insights into individual experiences and contributing to the development of effective treatment strategies. Let us explore why case studies are considered invaluable in understanding and addressing mental health conditions.

Why case studies are valuable in mental health research

Case studies offer a unique opportunity to examine mental health conditions within the real-life context of individuals. Unlike large-scale studies that focus on statistical data, case studies provide a detailed examination of specific cases, allowing researchers to delve into the complexities of a particular condition or treatment approach. This micro-level analysis helps researchers gain a deeper understanding of the nuances and intricacies involved.

The role of case studies in providing detailed information about individual experiences

Through case studies, researchers can capture rich narratives and delve into the lived experiences of individuals facing mental health challenges. These stories help to humanize the condition and provide valuable insights that go beyond a list of symptoms or diagnostic criteria. By understanding the unique experiences, thoughts, and emotions of individuals, researchers can develop a more comprehensive understanding of mental health conditions and tailor interventions accordingly.

How case studies contribute to the development of treatment strategies

Case studies form a vital foundation for the development of effective treatment strategies. By examining a specific case in detail, researchers can identify patterns, factors influencing treatment outcomes, and areas where intervention may be particularly effective. Moreover, case studies foster an iterative approach to treatment development—an ongoing cycle of using data and experience to refine and improve interventions.

By examining multiple case studies, researchers can identify common themes and trends, leading to the development of evidence-based guidelines and best practices. This allows healthcare professionals to provide more targeted and personalized support to individuals facing mental health conditions.

Furthermore, case studies can shed light on potential limitations or challenges in existing treatment approaches. By thoroughly analyzing different cases, researchers can identify gaps in current treatments and focus on areas that require further exploration and innovation.

In summary, case studies are a vital component of mental health research, offering detailed insights into the lived experiences of individuals with mental health conditions. They provide a rich understanding of the complexities of these conditions and contribute to the development of effective treatment strategies. By leveraging the power of case studies, researchers can move closer to improving the lives of individuals facing mental health challenges.

Examining a Real-life Case Study of Depression

In order to gain a deeper understanding of depression, let us now turn our attention to a real-life case study. By exploring the journey of an individual navigating through depression, we can gain valuable insights into the complexities and challenges associated with this mental health condition.

Introduction to the selected case study

In this case study, we will focus on Jane, a 32-year-old woman who has been struggling with depression for the past two years. Jane’s case offers a compelling narrative that highlights the various aspects of depression, including its onset, symptoms, and the treatment journey.

Background information on the individual facing depression

Before the onset of depression, Jane led a fulfilling and successful life. She had a promising career, a supportive network of friends and family, and engaged in hobbies that brought her joy. However, a series of life stressors, including a demanding job, a breakup, and the loss of a loved one, began to take a toll on her mental well-being.

Jane’s background highlights a common phenomenon – depression can affect individuals from all walks of life, irrespective of their socio-economic status, age, or external circumstances. It serves as a reminder that no one is immune to mental health challenges.

Presentation of symptoms and initial diagnosis

Jane began noticing a shift in her mood, characterized by persistent feelings of sadness and a lack of interest in activities she once enjoyed. She experienced disruptions in her sleep patterns, appetite changes, and a general sense of hopelessness. Recognizing the severity of her symptoms, Jane sought help from a mental health professional who diagnosed her with major depressive disorder.

Jane’s case exemplifies the varied and complex symptoms associated with depression. While individuals may exhibit overlapping symptoms, the intensity and manifestation of those symptoms can vary greatly, underscoring the importance of personalized and tailored treatment approaches.

By examining this real-life case study of depression, we can gain an empathetic understanding of the challenges faced by individuals experiencing this mental health condition. Through Jane’s journey, we will uncover the treatment options available for depression and analyze the effectiveness of the chosen approach. The case study will allow us to explore the nuances of depression and provide valuable insights into the treatment landscape for this prevalent mental health condition.

The Treatment Journey

When it comes to treating depression, there are various options available, ranging from therapy to medication. In this section, we will provide an overview of the treatment options for depression and analyze the treatment plan implemented in the real-life case study.

Overview of the treatment options available for depression

Treatment for depression typically involves a combination of approaches tailored to the individual’s needs. The two primary treatment modalities for depression are psychotherapy (talk therapy) and medication. Psychotherapy aims to help individuals explore their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, while medication can help alleviate symptoms by restoring chemical imbalances in the brain.

Common forms of psychotherapy used in the treatment of depression include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and psychodynamic therapy. These therapeutic approaches focus on addressing negative thought patterns, improving relationship dynamics, and gaining insight into underlying psychological factors contributing to depression.

In cases where medication is utilized, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed. These medications help rebalance serotonin levels in the brain, which are often disrupted in individuals with depression. Other classes of antidepressant medications, such as serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), may be considered in specific cases.

Exploring the treatment plan implemented in the case study

In Jane’s case, a comprehensive treatment plan was developed with the intention of addressing her specific needs and symptoms. Recognizing the severity of her depression, Jane’s healthcare team recommended a combination of talk therapy and medication.

Jane began attending weekly sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with a licensed therapist. This form of therapy aimed to help Jane identify and challenge negative thought patterns, develop coping strategies, and cultivate more adaptive behaviors. The therapeutic relationship provided Jane with a safe space to explore and process her emotions, ultimately helping her regain a sense of control over her life.

In conjunction with therapy, Jane’s healthcare provider prescribed an SSRI medication to assist in managing her symptoms. The medication was carefully selected based on Jane’s specific symptoms and medical history, and regular follow-up appointments were scheduled to monitor her response to the medication and adjust the dosage if necessary.

Analyzing the effectiveness of the treatment approach

The effectiveness of treatment for depression varies from person to person, and it often requires a period of trial and adjustment to find the most suitable intervention. In Jane’s case, the combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication proved to be beneficial. Over time, she reported a reduction in her depressive symptoms, an improvement in her overall mood, and increased ability to engage in activities she once enjoyed.

It is important to note that the treatment journey for depression is not always linear, and setbacks and challenges may occur along the way. Each individual responds differently to treatment, and adjustments might be necessary to optimize outcomes. Continuous communication between the individual and their healthcare team is crucial to addressing any concerns, monitoring progress, and adapting the treatment plan as needed.

By analyzing the treatment approach in the real-life case study, we gain insights into the various treatment options available for depression and how they can be tailored to meet individual needs. The combination of psychotherapy and medication offers a holistic approach, addressing both psychological and biological aspects of depression.

The Outcome and Lessons Learned

After undergoing treatment for depression, it is essential to assess the outcome and draw valuable lessons from the case study. In this section, we will discuss the progress made by the individual in the case study, examine the challenges faced during the treatment process, and identify key lessons learned.

Discussing the progress made by the individual in the case study

Throughout the treatment process, Jane experienced significant progress in managing her depression. She reported a reduction in depressive symptoms, improved mood, and a renewed sense of hope and purpose in her life. Jane’s active participation in therapy, combined with the appropriate use of medication, played a crucial role in her progress.

Furthermore, Jane’s support network of family and friends played a significant role in her recovery. Their understanding, empathy, and support provided a solid foundation for her journey towards improved mental well-being. This highlights the importance of social support in the treatment and management of depression.

Examining the challenges faced during the treatment process

Despite the progress made, Jane faced several challenges during her treatment journey. Adhering to the treatment plan consistently proved to be difficult at times, as she encountered setbacks and moments of self-doubt. Additionally, managing the side effects of the medication required careful monitoring and adjustments to find the right balance.

Moreover, the stigma associated with mental health continued to be a challenge for Jane. Overcoming societal misconceptions and seeking help required courage and resilience. The case study underscores the need for increased awareness, education, and advocacy to address the stigma surrounding mental health conditions.

Identifying the key lessons learned from the case study

The case study offers valuable lessons that can inform the treatment and support of individuals with depression:

1. Holistic Approach: The combination of psychotherapy and medication proved to be effective in addressing the psychological and biological aspects of depression. This highlights the need for a holistic and personalized treatment approach.

2. Importance of Support: Having a strong support system can significantly impact an individual’s ability to navigate through depression. Family, friends, and healthcare professionals play a vital role in providing empathy, understanding, and encouragement.

3. Individualized Treatment: Depression manifests differently in each individual, emphasizing the importance of tailoring treatment plans to meet individual needs. Personalized interventions are more likely to lead to positive outcomes.

4. Overcoming Stigma: Addressing the stigma associated with mental health conditions is crucial for individuals to seek timely help and access the support they need. Educating society about mental health is essential to create a more supportive and inclusive environment.

By drawing lessons from this real-life case study, we gain insights that can improve the understanding and treatment of depression. Recognizing the progress made, understanding the challenges faced, and implementing the lessons learned can contribute to more effective interventions and support systems for individuals facing depression.In conclusion, this article has explored the significance of mental health case studies in understanding and addressing depression, focusing on a real-life example. By delving into case studies, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of depression and the profound impact it has on individuals and society.

Through our examination of the selected case study, we have learned valuable lessons about the nature of depression and its treatment. We have seen how the combination of psychotherapy and medication can provide a holistic approach, addressing both psychological and biological factors. Furthermore, the importance of social support and the role of a strong network in an individual’s recovery journey cannot be overstated.

Additionally, we have identified challenges faced during the treatment process, such as adherence to the treatment plan and managing medication side effects. These challenges highlight the need for ongoing monitoring, adjustments, and open communication between individuals and their healthcare providers.

The case study has also emphasized the impact of stigma on individuals seeking help for depression. Addressing societal misconceptions and promoting mental health awareness is essential to create a more supportive environment for those affected by depression and other mental health conditions.

Overall, this article reinforces the significance of case studies in advancing our understanding of mental health conditions and developing effective treatment strategies. Through real-life examples, we gain a more comprehensive and empathetic perspective on depression, enabling us to provide better support and care for individuals facing this mental health challenge.

As we conclude, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of continued research and exploration of mental health case studies. The more we learn from individual experiences, the better equipped we become to address the diverse needs of those affected by mental health conditions. By fostering a culture of understanding, support, and advocacy, we can strive towards a future where individuals with depression receive the care and compassion they deserve.

Similar Posts

Exploring the World of Bipolar Bingo: Understanding the Game and Its Connection to Bipolar Disorder

Imagine a world where a game of chance holds the power to bring solace and support to individuals affected by bipolar disorder. A seemingly unlikely connection, but one that exists nonetheless. Welcome to the world of…

Can Anxiety Disorders be Genetic? Exploring the Hereditary Aspects of Anxiety Disorders

Introduction to Genetic Factors in Anxiety Disorders Understanding anxiety disorders Anxiety disorders are a common mental health condition that affect millions of individuals worldwide. People with anxiety disorders experience overwhelming feelings of fear, worry, and unease…

Understanding the Abbreviations and Acronyms for Bipolar Disorder

Living with bipolar disorder can be a challenging journey. The constant rollercoaster of emotions, the highs and lows, can take a toll on a person’s mental and emotional well-being. But what if there was a way…

The Connection Between Ice Cream and Depression: Can Ice Cream Really Help?

Ice cream has long been hailed as a delightful treat, bringing joy to people of all ages. It is often associated with carefree summer days, laughter, and moments of pure bliss. But what if I told…

Understanding the Relationship Between Bipolar Disorder and PTSD

Imagine living with extreme mood swings that can range from feeling on top of the world one day to plunging into the depths of despair the next. Now add the haunting memories of a traumatic event…

The Connection Between Meth and Bipolar: Understanding the Link and Seeking Treatment

It’s a tangled web of interconnectedness – the world of mental health and substance abuse. One doesn’t often think of them as intertwined, but for those battling bipolar disorder, the link becomes all too clear. And…

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 Treatment of Depression

- Published: February 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Chapter 4 covers the treatment of depression, and discusses popular myths regarding depression, its frequency, characteristics and diagnosis, and includes case studies, assessment, case conceptualization, intervention development and course of treatment, problems that may arise in therapy, ethical considerations, common mistakes in the course of treatment, relapse prevention, and cultural factors.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih research matters.

April 23, 2024

Research in Context: Treating depression

Finding better approaches.

While effective treatments for major depression are available, there is still room for improvement. This special Research in Context feature explores the development of more effective ways to treat depression, including personalized treatment approaches and both old and new drugs.

Everyone has a bad day sometimes. People experience various types of stress in the course of everyday life. These stressors can cause sadness, anxiety, hopelessness, frustration, or guilt. You may not enjoy the activities you usually do. These feelings tend to be only temporary. Once circumstances change, and the source of stress goes away, your mood usually improves. But sometimes, these feelings don’t go away. When these feelings stick around for at least two weeks and interfere with your daily activities, it’s called major depression, or clinical depression.

In 2021, 8.3% of U.S. adults experienced major depression. That’s about 21 million people. Among adolescents, the prevalence was much greater—more than 20%. Major depression can bring decreased energy, difficulty thinking straight, sleep problems, loss of appetite, and even physical pain. People with major depression may become unable to meet their responsibilities at work or home. Depression can also lead people to use alcohol or drugs or engage in high-risk activities. In the most extreme cases, depression can drive people to self-harm or even suicide.

The good news is that effective treatments are available. But current treatments have limitations. That’s why NIH-funded researchers have been working to develop more effective ways to treat depression. These include finding ways to predict whether certain treatments will help a given patient. They're also trying to develop more effective drugs or, in some cases, find new uses for existing drugs.

Finding the right treatments

The most common treatments for depression include psychotherapy, medications, or a combination. Mild depression may be treated with psychotherapy. Moderate to severe depression often requires the addition of medication.

Several types of psychotherapy have been shown to help relieve depression symptoms. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy helps people to recognize harmful ways of thinking and teaches them how to change these. Some researchers are working to develop new therapies to enhance people’s positive emotions. But good psychotherapy can be hard to access due to the cost, scheduling difficulties, or lack of available providers. The recent growth of telehealth services for mental health has improved access in some cases.

There are many antidepressant drugs on the market. Different drugs will work best on different patients. But it can be challenging to predict which drugs will work for a given patient. And it can take anywhere from 6 to 12 weeks to know whether a drug is working. Finding an effective drug can involve a long period of trial and error, with no guarantee of results.

If depression doesn’t improve with psychotherapy or medications, brain stimulation therapies could be used. Electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, uses electrodes to send electric current into the brain. A newer technique, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), stimulates the brain using magnetic fields. These treatments must be administered by specially trained health professionals.

“A lot of patients, they kind of muddle along, treatment after treatment, with little idea whether something’s going to work,” says psychiatric researcher Dr. Amit Etkin.

One reason it’s difficult to know which antidepressant medications will work is that there are likely different biological mechanisms that can cause depression. Two people with similar symptoms may both be diagnosed with depression, but the causes of their symptoms could be different. As NIH depression researcher Dr. Carlos Zarate explains, “we believe that there’s not one depression, but hundreds of depressions.”

Depression may be due to many factors. Genetics can put certain people at risk for depression. Stressful situations, physical health conditions, and medications may contribute. And depression can also be part of a more complicated mental disorder, such as bipolar disorder. All of these can affect which treatment would be best to use.

Etkin has been developing methods to distinguish patients with different types of depression based on measurable biological features, or biomarkers. The idea is that different types of patients would respond differently to various treatments. Etkin calls this approach “precision psychiatry.”

One such type of biomarker is electrical activity in the brain. A technique called electroencephalography, or EEG, measures electrical activity using electrodes placed on the scalp. When Etkin was at Stanford University, he led a research team that developed a machine-learning algorithm to predict treatment response based on EEG signals. The team applied the algorithm to data from a clinical trial of the antidepressant sertraline (Zoloft) involving more than 300 people.

EEG data for the participants were collected at the outset. Participants were then randomly assigned to take either sertraline or an inactive placebo for eight weeks. The team found a specific set of signals that predicted the participants’ responses to sertraline. The same neural “signature” also predicted which patients with depression responded to medication in a separate group.

Etkin’s team also examined this neural signature in a set of patients who were treated with TMS and psychotherapy. People who were predicted to respond less to sertraline had a greater response to the TMS/psychotherapy combination.

Etkin continues to develop methods for personalized depression treatment through his company, Alto Neuroscience. He notes that EEG has the advantage of being low-cost and accessible; data can even be collected in a patient’s home. That’s important for being able to get personalized treatments to the large number of people they could help. He’s also working on developing antidepressant drugs targeted to specific EEG profiles. Candidate drugs are in clinical trials now.

“It’s not like a pie-in-the-sky future thing, 20-30 years from now,” Etkin explains. “This is something that could be in people's hands within the next five years.”

New tricks for old drugs

While some researchers focus on matching patients with their optimal treatments, others aim to find treatments that can work for many different patients. It turns out that some drugs we’ve known about for decades might be very effective antidepressants, but we didn’t recognize their antidepressant properties until recently.

One such drug is ketamine. Ketamine has been used as an anesthetic for more than 50 years. Around the turn of this century, researchers started to discover its potential as an antidepressant. Zarate and others have found that, unlike traditional antidepressants that can take weeks to take effect, ketamine can improve depression in as little as one day. And a single dose can have an effect for a week or more. In 2019, the FDA approved a form of ketamine for treating depression that is resistant to other treatments.

But ketamine has drawbacks of its own. It’s a dissociative drug, meaning that it can make people feel disconnected from their body and environment. It also has the potential for addiction and misuse. For these reasons, it’s a controlled substance and can only be administered in a doctor’s office or clinic.

Another class of drugs being studied as possible antidepressants are psychedelics. These include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms. These drugs can temporarily alter a person’s mood, thoughts, and perceptions of reality. Some have historically been used for religious rituals, but they are also used recreationally.

In clinical studies, psychedelics are typically administered in combination with psychotherapy. This includes several preparatory sessions with a therapist in the weeks before getting the drug, and several sessions in the weeks following to help people process their experiences. The drugs are administered in a controlled setting.

Dr. Stephen Ross, co-director of the New York University Langone Health Center for Psychedelic Medicine, describes a typical session: “It takes place in a living room-like setting. The person is prepared, and they state their intention. They take the drug, they lie supine, they put on eye shades and preselected music, and two therapists monitor them.” Sessions last for as long as the acute effects of the drug last, which is typically several hours. This is a healthcare-intensive intervention given the time and personnel needed.

In 2016, Ross led a clinical trial examining whether psilocybin-assisted therapy could reduce depression and anxiety in people with cancer. According to Ross, as many as 40% of people with cancer have clinically significant anxiety and depression. The study showed that a single psilocybin session led to substantial reductions in anxiety and depression compared with a placebo. These reductions were evident as soon as one day after psilocybin administration. Six months later, 60-80% of participants still had reduced depression and anxiety.

Psychedelic drugs frequently trigger mystical experiences in the people who take them. “People can feel a sense…that their consciousness is part of a greater consciousness or that all energy is one,” Ross explains. “People can have an experience that for them feels more ‘real’ than regular reality. They can feel transported to a different dimension of reality.”

About three out of four participants in Ross’s study said it was among the most meaningful experiences of their lives. And the degree of mystical experience correlated with the drug’s therapeutic effect. A long-term follow-up study found that the effects of the treatment continued more than four years later.

If these results seem too good to be true, Ross is quick to point out that it was a small study, with only 29 participants, although similar studies from other groups have yielded similar results. Psychedelics haven’t yet been shown to be effective in a large, controlled clinical trial. Ross is now conducting a trial with 200 people to see if the results of his earlier study pan out in this larger group. For now, though, psychedelics remain experimental drugs—approved for testing, but not for routine medical use.

Unlike ketamine, psychedelics aren’t considered addictive. But they, too, carry risks, which certain conditions may increase. Psychedelics can cause cardiovascular complications. They can cause psychosis in people who are predisposed to it. In uncontrolled settings, they have the risk of causing anxiety, confusion, and paranoia—a so-called “bad trip”—that can lead the person taking the drug to harm themself or others. This is why psychedelic-assisted therapy takes place in such tightly controlled settings. That increases the cost and complexity of the therapy, which may prevent many people from having access to it.

Better, safer drugs

Despite the promise of ketamine or psychedelics, their drawbacks have led some researchers to look for drugs that work like them but with fewer side effects.

Depression is thought to be caused by the loss of connections between nerve cells, or neurons, in certain regions of the brain. Ketamine and psychedelics both promote the brain’s ability to repair these connections, a quality called plasticity. If we could understand how these drugs encourage plasticity, we might be able to design drugs that can do so without the side effects.

Dr. David Olson at the University of California, Davis studies how psychedelics work at the cellular and molecular levels. The drugs appear to promote plasticity by binding to a receptor in cells called the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor (5-HT2AR). But many other compounds also bind 5-HT2AR without promoting plasticity. In a recent NIH-funded study, Olson showed that 5-HT2AR can be found both inside and on the surface of the cell. Only compounds that bound to the receptor inside the cells promoted plasticity. This suggests that a drug has to be able to get into the cell to promote plasticity.

Moreover, not all drugs that bind 5-HT2AR have psychedelic effects. Olson’s team has developed a molecular sensor, called psychLight, that can identify which compounds that bind 5-HT2AR have psychedelic effects. Using psychLight, they identified compounds that are not psychedelic but still have rapid and long-lasting antidepressant effects in animal models. He’s founded a company, Delix Therapeutics, to further develop drugs that promote plasticity.

Meanwhile, Zarate and his colleagues have been investigating a compound related to ketamine called hydroxynorketamine (HNK). Ketamine is converted to HNK in the body, and this process appears to be required for ketamine’s antidepressant effects. Administering HNK directly produced antidepressant-like effects in mice. At the same time, it did not cause the dissociative side effects and addiction caused by ketamine. Zarate’s team has already completed phase I trials of HNK in people showing that it’s safe. Phase II trials to find out whether it’s effective are scheduled to begin soon.

“What [ketamine and psychedelics] are doing for the field is they’re helping us realize that it is possible to move toward a repair model versus a symptom mitigation model,” Olson says. Unlike existing antidepressants, which just relieve the symptoms of depression, these drugs appear to fix the underlying causes. That’s likely why they work faster and produce longer-lasting effects. This research is bringing us closer to having safer antidepressants that only need to be taken once in a while, instead of every day.

—by Brian Doctrow, Ph.D.

Related Links

- How Psychedelic Drugs May Help with Depression

- Biosensor Advances Drug Discovery

- Neural Signature Predicts Antidepressant Response

- How Ketamine Relieves Symptoms of Depression

- Protein Structure Reveals How LSD Affects the Brain

- Predicting The Usefulness of Antidepressants

- Depression Screening and Treatment in Adults

- Serotonin Transporter Structure Revealed

- Placebo Effect in Depression Treatment

- When Sadness Lingers: Understanding and Treating Depression

- Psychedelic and Dissociative Drugs

References: An electroencephalographic signature predicts antidepressant response in major depression. Wu W, Zhang Y, Jiang J, Lucas MV, Fonzo GA, Rolle CE, Cooper C, Chin-Fatt C, Krepel N, Cornelssen CA, Wright R, Toll RT, Trivedi HM, Monuszko K, Caudle TL, Sarhadi K, Jha MK, Trombello JM, Deckersbach T, Adams P, McGrath PJ, Weissman MM, Fava M, Pizzagalli DA, Arns M, Trivedi MH, Etkin A. Nat Biotechnol. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0397-3. Epub 2020 Feb 10. PMID: 32042166. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, Mennenga SE, Belser A, Kalliontzi K, Babb J, Su Z, Corby P, Schmidt BL. J Psychopharmacol . 2016 Dec;30(12):1165-1180. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675512. PMID: 27909164. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. Agin-Liebes GI, Malone T, Yalch MM, Mennenga SE, Ponté KL, Guss J, Bossis AP, Grigsby J, Fischer S, Ross S. J Psychopharmacol . 2020 Feb;34(2):155-166. doi: 10.1177/0269881119897615. Epub 2020 Jan 9. PMID: 31916890. Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, Cameron LP, Patel SD, Hennessey JJ, Saeger HN, McCorvy JD, Gray JA, Tian L, Olson DE. Science . 2023 Feb 17;379(6633):700-706. doi: 10.1126/science.adf0435. Epub 2023 Feb 16. PMID: 36795823. Psychedelic-inspired drug discovery using an engineered biosensor. Dong C, Ly C, Dunlap LE, Vargas MV, Sun J, Hwang IW, Azinfar A, Oh WC, Wetsel WC, Olson DE, Tian L. Cell . 2021 Apr 8: S0092-8674(21)00374-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.043. Epub 2021 Apr 28. PMID: 33915107. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, Georgiou P, Fischell J, Elmer GI, Alkondon M, Yuan P, Pribut HJ, Singh NS, Dossou KS, Fang Y, Huang XP, Mayo CL, Wainer IW, Albuquerque EX, Thompson SM, Thomas CJ, Zarate CA Jr, Gould TD. Nature . 2016 May 26;533(7604):481-6. doi: 10.1038/nature17998. Epub 2016 May 4. PMID: 27144355.

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 22 April 2024

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on depression incidence and healthcare service use among patients with depression: an interrupted time-series analysis from a 9-year population-based study

- Vivien Kin Yi Chan 1 na1 ,

- Yi Chai 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Sandra Sau Man Chan 3 ,

- Hao Luo 4 ,

- Mark Jit 5 , 7 ,

- Martin Knapp 4 , 6 ,

- David Makram Bishai 7 ,

- Michael Yuxuan Ni 7 , 8 , 9 ,

- Ian Chi Kei Wong 1 , 10 , 11 , 13 &

- Xue Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4836-7808 1 , 10 , 12 , 13

BMC Medicine volume 22 , Article number: 169 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

800 Accesses

29 Altmetric

Metrics details

Most studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on depression burden focused on the earlier pandemic phase specific to lockdowns, but the longer-term impact of the pandemic is less well-studied. In this population-based cohort study, we examined the short-term and long-term impacts of COVID-19 on depression incidence and healthcare service use among patients with depression.

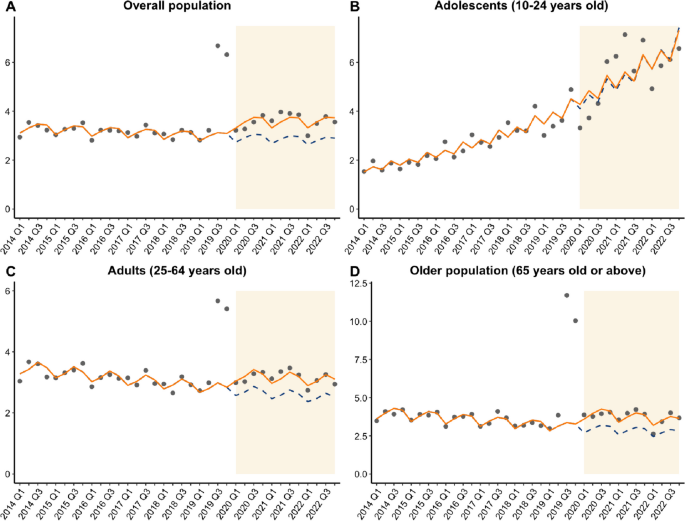

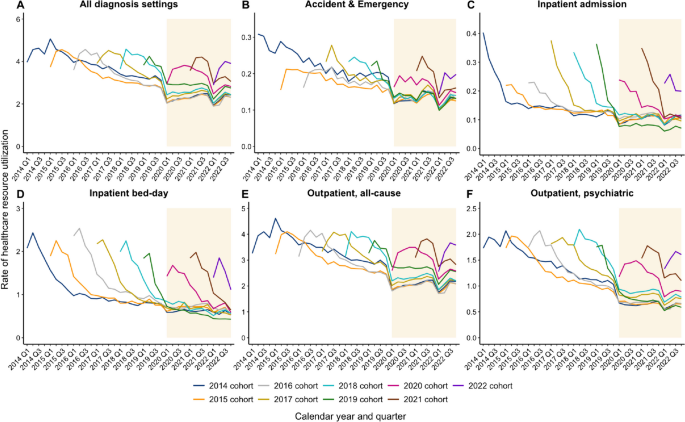

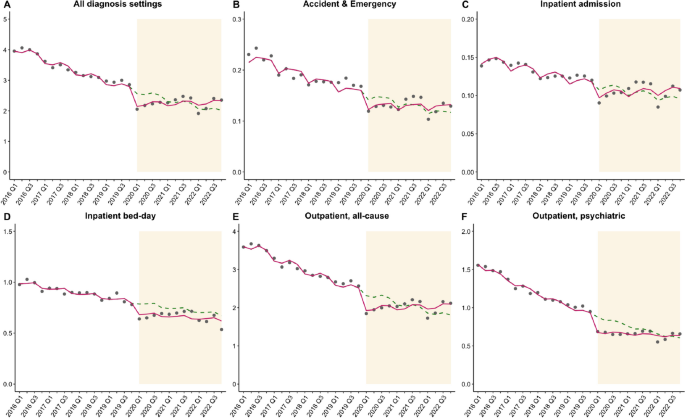

Using the territory-wide electronic medical records in Hong Kong, we identified all patients aged ≥ 10 years with new diagnoses of depression from 2014 to 2022. We performed an interrupted time-series (ITS) analysis to examine changes in incidence of medically attended depression before and during the pandemic. We then divided all patients into nine cohorts based on year of depression incidence and studied their initial and ongoing service use patterns until the end of 2022. We applied generalized linear modeling to compare the rates of healthcare service use in the year of diagnosis between patients newly diagnosed before and during the pandemic. A separate ITS analysis explored the pandemic impact on the ongoing service use among prevalent patients with depression.

We found an immediate increase in depression incidence (RR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.10–1.33, p < 0.001) in the population after the pandemic began with non-significant slope change, suggesting a sustained effect until the end of 2022. Subgroup analysis showed that the increases in incidence were significant among adults and the older population, but not adolescents. Depression patients newly diagnosed during the pandemic used 11% fewer resources than the pre-pandemic patients in the first diagnosis year. Pre-existing depression patients also had an immediate decrease of 16% in overall all-cause service use since the pandemic, with a positive slope change indicating a gradual rebound over a 3-year period.

Conclusions

During the pandemic, service provision for depression was suboptimal in the face of increased demand generated by the increasing depression incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings indicate the need to improve mental health resource planning preparedness for future public health crises.

Peer Review reports

The COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020 has resulted in an unprecedented public health crisis, with 771 million confirmed cases and over 6 million deaths across the globe as of September 2023 [ 1 ]. To curb the spread and reduce the mortality of SARS-CoV-2 infections, governments worldwide enacted stringent measures to contain its spread, including social mobility restrictions, mask-wearing, massive screenings, and lockdowns. Despite their effectiveness in limiting viral spread, these measures may have created a macro-environment of fear, social exclusion of individuals who contracted the virus, and reduced community cohesion [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. The pandemic and the ensuing measures also led to economic disruption and created financial hardship for millions of families [ 4 , 5 ]. The combined pandemic stresses may have exacerbated the risk factors for mental health conditions including depression. Among patients with pre-existing depression, the government effort re-prioritized for outbreak control may have also led to disrupted non-emergency services and unmet care need in mental health [ 6 ].

A meta-analysis estimated an additional 53 million cases of depression and a 27.6% increase in its global prevalence in 2020 due to COVID-19-related illnesses and reduced mobility [ 7 ], which affected individuals across age groups [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. In Hong Kong, a survey showed a consistent mental health crisis with a two-fold increase in depression symptoms and a 28.3% rise in the stress level even during the well-managed small-scale outbreaks [ 11 ]. Conversely, other studies reported that the pandemic reduced the risk of depression and self-harm because of the emotional security provided by timely government intervention, but these findings were confounded by increased barriers to seek medical help [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. In the emergency phase of the pandemic, it was reported that lockdowns significantly reduced healthcare service use for both outpatient and inpatient services [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Studies also found an elevated risk of depression relapse and use of antidepressants [ 18 , 19 ].

Literature exploring pandemic impact on depression has mostly focused on the earlier phase of the pandemic (2020–2021) when short-term lockdown orders were in place. There are fewer studies and more mixed results for the post-emergency phase. Hong Kong followed the “dynamic zero-COVID policy” of China with strict border control, contact tracing, and quarantine before cases spread until the end of 2022 and so recorded a low number of SARS-CoV-2 cases for most of the time before a major Omicron outbreak [ 20 ]. It did not experience full lockdown, although stringent infection control and social measures were deployed for an entire 3-year-long period. This context thus enables us to evaluate the longer-term pandemic impact apart from a focus on lockdowns. In the late pandemic period, it is also useful to understand any potential decline in depression incidence and rebound in health service utilization. Using interrupted time series (ITS) analysis with a cohort study, we examined the changes in depression incidence and healthcare service use due to the pandemic, aiming to measure both the short-term (immediately after pandemic onset) and long-term (3 years since the outbreak) impacts on the burden of depression. We aimed to facilitate better preparedness in mental health resource planning for future public health crises.

Data source

We analyzed the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS), the territory-wide routine electronic medical record (EMR) developed by the Hospital Authority, which manages all public healthcare services in Hong Kong and provides publicly funded healthcare services to all eligible residents (> 7.6 million). CDARS covers real-time anonymized patient-level data, including demographics, deaths, attendances, and all-cause diagnoses coded based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), since 1993 across outpatient, inpatient, and emergency settings for research and auditing purposes in the public sector. The quality and accuracy of CDARS have been demonstrated in population-based studies on COVID-19 [ 21 , 22 ] and depression [ 23 , 24 ]. In Hong Kong, the public healthcare is heavily subsidized at a highly affordable price, while the private sector is financed mainly by non-compulsory medical insurance and out-of-pocket payments. The Hospital Authority thus manages 76% of chronic medical conditions including mental health illnesses despite a dual-track public and private system [ 25 ].

Study design and participants