- May 3 Cultures collide at the Bellaire International Student Association Fest

- May 2 Uncalculated uncertainties

- May 1 National Honor Society welcomes new inductees

- April 27 The road from Rhode Island

- April 27 Students celebrate with sustainability at Earth Day party

Three Penny Press

Students spend three times longer on homework than average, survey reveals

Sonya Kulkarni and Pallavi Gorantla | Jan 9, 2022

Graphic by Sonya Kulkarni

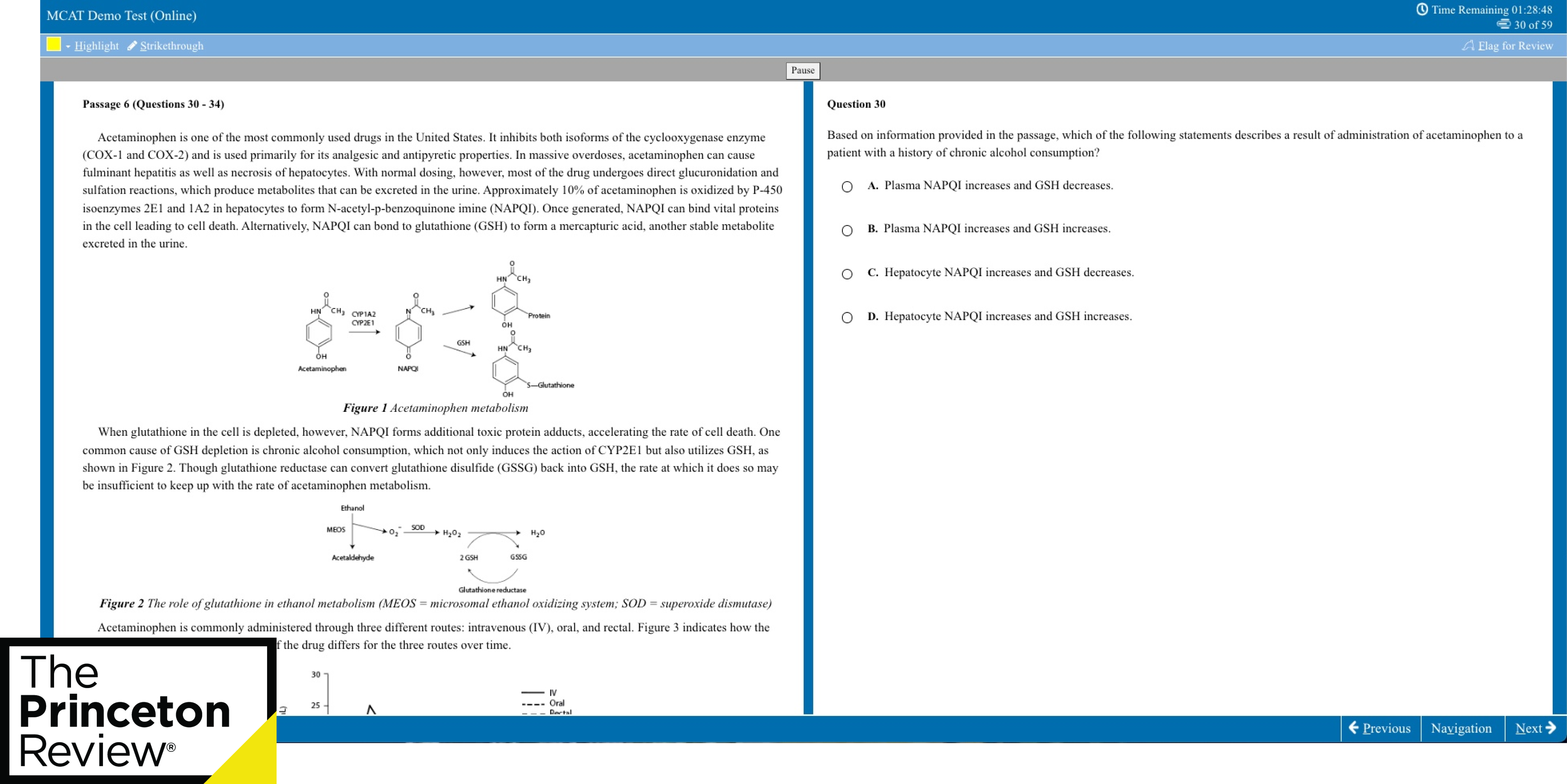

The National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association have suggested that a healthy number of hours that students should be spending can be determined by the “10-minute rule.” This means that each grade level should have a maximum homework time incrementing by 10 minutes depending on their grade level (for instance, ninth-graders would have 90 minutes of homework, 10th-graders should have 100 minutes, and so on).

As ‘finals week’ rapidly approaches, students not only devote effort to attaining their desired exam scores but make a last attempt to keep or change the grade they have for semester one by making up homework assignments.

High schoolers reported doing an average of 2.7 hours of homework per weeknight, according to a study by the Washington Post from 2018 to 2020 of over 50,000 individuals. A survey of approximately 200 Bellaire High School students revealed that some students spend over three times this number.

The demographics of this survey included 34 freshmen, 43 sophomores, 54 juniors and 54 seniors on average.

When asked how many hours students spent on homework in a day on average, answers ranged from zero to more than nine with an average of about four hours. In contrast, polled students said that about one hour of homework would constitute a healthy number of hours.

Junior Claire Zhang said she feels academically pressured in her AP schedule, but not necessarily by the classes.

“The class environment in AP classes can feel pressuring because everyone is always working hard and it makes it difficult to keep up sometimes.” Zhang said.

A total of 93 students reported that the minimum grade they would be satisfied with receiving in a class would be an A. This was followed by 81 students, who responded that a B would be the minimum acceptable grade. 19 students responded with a C and four responded with a D.

“I am happy with the classes I take, but sometimes it can be very stressful to try to keep up,” freshman Allyson Nguyen said. “I feel academically pressured to keep an A in my classes.”

Up to 152 students said that grades are extremely important to them, while 32 said they generally are more apathetic about their academic performance.

Last year, nine valedictorians graduated from Bellaire. They each achieved a grade point average of 5.0. HISD has never seen this amount of valedictorians in one school, and as of now there are 14 valedictorians.

“I feel that it does degrade the title of valedictorian because as long as a student knows how to plan their schedule accordingly and make good grades in the classes, then anyone can be valedictorian,” Zhang said.

Bellaire offers classes like physical education and health in the summer. These summer classes allow students to skip the 4.0 class and not put it on their transcript. Some electives also have a 5.0 grade point average like debate.

Close to 200 students were polled about Bellaire having multiple valedictorians. They primarily answered that they were in favor of Bellaire having multiple valedictorians, which has recently attracted significant acclaim .

Senior Katherine Chen is one of the 14 valedictorians graduating this year and said that she views the class of 2022 as having an extraordinary amount of extremely hardworking individuals.

“I think it was expected since freshman year since most of us knew about the others and were just focused on doing our personal best,” Chen said.

Chen said that each valedictorian achieved the honor on their own and deserves it.

“I’m honestly very happy for the other valedictorians and happy that Bellaire is such a good school,” Chen said. “I don’t feel any less special with 13 other valedictorians.”

Nguyen said that having multiple valedictorians shows just how competitive the school is.

“It’s impressive, yet scary to think about competing against my classmates,” Nguyen said.

Offering 30 AP classes and boasting a significant number of merit-based scholars Bellaire can be considered a competitive school.

“I feel academically challenged but not pressured,” Chen said. “Every class I take helps push me beyond my comfort zone but is not too much to handle.”

Students have the opportunity to have off-periods if they’ve met all their credits and are able to maintain a high level of academic performance. But for freshmen like Nguyen, off periods are considered a privilege. Nguyen said she usually has an hour to five hours worth of work everyday.

“Depending on the day, there can be a lot of work, especially with extra curriculars,” Nguyen said. “Although, I am a freshman, so I feel like it’s not as bad in comparison to higher grades.”

According to the survey of Bellaire students, when asked to evaluate their agreement with the statement “students who get better grades tend to be smarter overall than students who get worse grades,” responders largely disagreed.

Zhang said that for students on the cusp of applying to college, it can sometimes be hard to ignore the mental pressure to attain good grades.

“As a junior, it’s really easy to get extremely anxious about your GPA,” Zhang said. “It’s also a very common but toxic practice to determine your self-worth through your grades but I think that we just need to remember that our mental health should also come first. Sometimes, it’s just not the right day for everyone and one test doesn’t determine our smartness.”

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – JuanDiego Cerda

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Michael Goldman

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Caroline Pettigrew

The road from Rhode Island

Snapping memories

Cultures collide at the Bellaire International Student Association Fest

Uncalculated uncertainties

National Honor Society welcomes new inductees

Students celebrate with sustainability at Earth Day party

Humans of Bellaire

Someone to count on

Welcome to Houston

A passion for performing

Nature’s wildheart: Teen naturalist kindles love for the environment

Parental influence

The student news site of Bellaire High School

- Letter to the Editor

- Submit a Story Idea

- Advertising/Sponsorships

Comments (7)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Anonymous • Nov 21, 2023 at 10:32 am

It’s not really helping me understand how much.

josh • May 9, 2023 at 9:58 am

Kassie • May 6, 2022 at 12:29 pm

Im using this for an English report. This is great because on of my sources needed to be from another student. Homework drives me insane. Im glad this is very updated too!!

Kaylee Swaim • Jan 25, 2023 at 9:21 pm

I am also using this for an English report. I have to do an argumentative essay about banning homework in schools and this helps sooo much!

Izzy McAvaney • Mar 15, 2023 at 6:43 pm

I am ALSO using this for an English report on cutting down school days, homework drives me insane!!

E. Elliott • Apr 25, 2022 at 6:42 pm

I’m from Louisiana and am actually using this for an English Essay thanks for the information it was very informative.

Nabila Wilson • Jan 10, 2022 at 6:56 pm

Interesting with the polls! I didn’t realize about 14 valedictorians, that’s crazy.

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

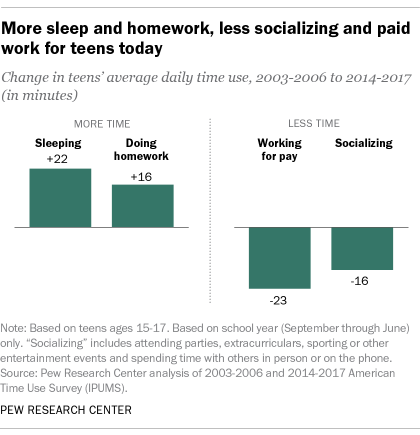

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

How Much Homework Is Too Much for Our Teens?

Here's what educators and parents can do to help kids find the right balance between school and home.

Does Your Teen Have Too Much Homework?

Today’s teens are under a lot of pressure.

They're under pressure to succeed, to win, to be the best and to get into the top colleges. With so much pressure, is it any wonder today’s youth report being under as much stress as their parents? In fact, during the school year, teens say they experience stress levels higher than those reported by adults, according to a previous American Psychological Association "Stress in America" survey.

Odds are if you ask a teen what's got them so worked up, the subject of school will come up. School can cause a lot of stress, which can lead to other serious problems, like sleep deprivation . According to the National Sleep Foundation, teens need between eight and 10 hours of sleep each night, but only 15 percent are even getting close to that amount. During the school week, most teens only get about six hours of zzz’s a night, and some of that sleep deficit may be attributed to homework.

When it comes to school, many adults would rather not trade places with a teen. Think about it. They get up at the crack of dawn and get on the bus when it’s pitch dark outside. They put in a full day sitting in hours of classes (sometimes four to seven different classes daily), only to get more work dumped on them to do at home. To top it off, many kids have after-school obligations, such as extracurricular activities including clubs and sports , and some have to work. After a long day, they finally get home to do even more work – schoolwork.

[Read: What Parents Should Know About Teen Depression .]

Homework is not only a source of stress for students, but it can also be a hassle for parents. If you are the parent of a kid who strives to be “perfect," then you know all too well how much time your child spends making sure every bit of homework is complete, even if it means pulling an all-nighter. On the flip side, if you’re the parent of a child who decided that school ends when the last bell rings, then you know how exhausting that homework tug-of-war can be. And heaven forbid if you’re that parent who is at their wit's end because your child excels on tests and quizzes but fails to turn in assignments. The woes of academics can go well beyond the confines of the school building and right into the home.

This is the time of year when many students and parents feel the burden of the academic load. Following spring break, many schools across the nation head into the final stretch of the year. As a result, some teachers increase the amount of homework they give. The assignments aren’t punishment, although to students and parents who are having to constantly stay on top of their kids' schoolwork, they can sure seem that way.

From a teacher’s perspective, the assignments are meant to help students better understand the course content and prepare for upcoming exams. Some schools have state-mandated end of grade or final tests. In those states these tests can account for 20 percent of a student’s final grade. So teachers want to make sure that they cover the entire curriculum before that exam. Aside from state-mandated tests, some high school students are enrolled in advanced placement or international baccalaureate college-level courses that have final tests given a month or more before the end of the term. In order to cover all of the content, teachers must maintain an accelerated pace. All of this means more out of class assignments.

Given the challenges kids face, there are a few questions parents and educators should consider:

Is homework necessary?

Many teens may give a quick "no" to this question, but the verdict is still out. Research supports both sides of the argument. Personally, I would say, yes, some homework is necessary, but it must be purposeful. If it’s busy work, then it’s a waste of time. Homework should be a supplemental teaching tool. Too often, some youth go home completely lost as they haven’t grasped concepts covered in class and they may become frustrated and overwhelmed.

For a parent who has been in this situation, you know how frustrating this can be, especially if it’s a subject that you haven’t encountered in a while. Homework can serve a purpose such as improving grades, increasing test scores and instilling a good work ethic. Purposeful homework can come in the form of individualizing assignments based on students’ needs or helping students practice newly acquired skills.

Homework should not be used to extend class time to cover more material. If your child is constantly coming home having to learn the material before doing the assignments, then it’s time to contact the teacher and set up a conference. Listen when kids express their concerns (like if they say they're expected to know concepts not taught in class) as they will provide clues about what’s happening or not happening in the classroom. Plus, getting to the root of the problem can help with keeping the peace at home too, as an irritable and grumpy teen can disrupt harmonious family dynamics .

[Read: What Makes Teens 'Most Likely to Succeed?' ]

How much is too much?

According to the National PTA and the National Education Association, students should only be doing about 10 minutes of homework per night per grade level. But teens are doing a lot more than that, according to a poll of high school students by the organization Statistic Brain . In that poll teens reported spending, on average, more than three hours on homework each school night, with 11th graders spending more time on homework than any other grade level. By contrast, some polls have shown that U.S. high school students report doing about seven hours of homework per week.

Much of a student's workload boils down to the courses they take (such as advanced or college prep classes), the teaching philosophy of educators and the student’s commitment to doing the work. Regardless, research has shown that doing more than two hours of homework per night does not benefit high school students. Having lots of homework to do every day makes it difficult for teens to have any downtime , let alone family time .

How do we respond to students' needs?

As an educator and parent, I can honestly say that oftentimes there is a mismatch in what teachers perceive as only taking 15 minutes and what really takes 45 minutes to complete. If you too find this to be the case, then reach out to your child's teacher and find out why the assignments are taking longer than anticipated for your child to complete.

Also, ask the teacher about whether faculty communicate regularly with one another about large upcoming assignments. Whether it’s setting up a shared school-wide assignment calendar or collaborating across curriculums during faculty meetings, educators need to discuss upcoming tests and projects, so students don’t end up with lots of assignments all competing for their attention and time at once. Inevitably, a student is going to get slammed occasionally, but if they have good rapport with their teachers, they will feel comfortable enough to reach out and see if alternative options are available. And as a parent, you can encourage your kid to have that dialogue with the teacher.

Often teens would rather blend into the class than stand out. That’s unfortunate because research has shown time and time again that positive teacher-student relationships are strong predictors of student engagement and achievement. By and large, most teachers appreciate students advocating for themselves and will go the extra mile to help them out.

Can there be a balance between home and school?

Students can strike a balance between school and home, but parents will have to help them find it. They need your guidance to learn how to better manage their time, get organized and prioritize tasks, which are all important life skills. Equally important is developing good study habits. Some students may need tutoring or coaching to help them learn new material or how to take notes and study. Also, don’t forget the importance of parent-teacher communication. Most educators want nothing more than for their students to succeed in their courses.

Learning should be fun, not mundane and cumbersome. Homework should only be given if its purposeful and in moderation. Equally important to homework is engaging in activities, socializing with friends and spending time with the family.

[See: 10 Concerns Parents Have About Their Kids' Health .]

Most adults don’t work a full-time job and then go home and do three more hours of work, and neither should your child. It's not easy learning to balance everything, especially if you're a teen. If your child is spending several hours on homework each night, don't hesitate to reach out to teachers and, if need be, school officials. Collectively, we can all work together to help our children de-stress and find the right balance between school and home.

12 Questions You Should Ask Your Kids at Dinner

Tags: parenting , family , family health , teens , education , high school , stress

Most Popular

health disclaimer »

Disclaimer and a note about your health ».

Your Health

A guide to nutrition and wellness from the health team at U.S. News & World Report.

You May Also Like

Moderating pandemic news consumption.

Victor G. Carrion, M.D. June 8, 2020

Helping Young People Gain Resilience

Nancy Willard May 18, 2020

Keep Kids on Track With Reading During the Pandemic

Ashley Johnson and Tom Dillon May 14, 2020

Pandemic and Summer Education

Nancy Willard May 12, 2020

Trauma and Childhood Regression

Dr. Gail Saltz May 8, 2020

The Sandwich Generation and the Pandemic

Laurie Wolk May 6, 2020

Adapting to an Evolving Pandemic

Laurie Wolk May 1, 2020

Picky Eating During Quarantine

Jill Castle May 1, 2020

Baby Care During the Pandemic

Dr. Natasha Burgert April 29, 2020

Co-Parenting During the Pandemic

Ron Deal April 24, 2020

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

How false reports of homework overload in America have spread so far

Confusing debate suggests homework is too much when it’s often too little

A previous version of this column mistakenly referred to the education nonprofit Challenge Success as College Success. The column has been corrected.

Recently I saw in the Phi Delta Kappan magazine an attack on homework by a California high school junior, Colin McGrath. Writing the piece as a letter to his younger brother , he said:

“In a 2020 Washington Post article , Denise Pope described what she learned from a survey of more than 50,000 high school students: On average, they complete 2.7 hours of homework a night . That means you won’t be able to play on the trampoline anymore, ride your bike, or explore any other facet of life.”

My reaction: Huh??!! I’ve spent two decades trying to dispel the myth that our kids all get too much homework. The truth, according to several scholarly sources, is that U.S. high school homework averages about an hour a night.

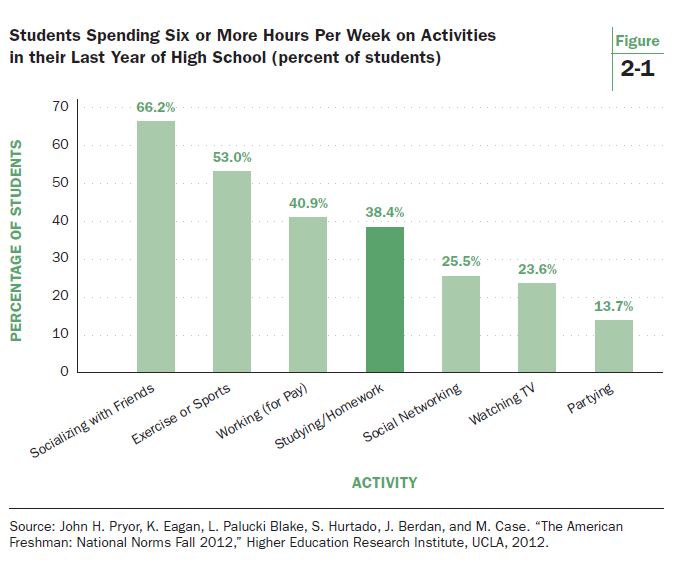

What most teenagers do with the rest of their free time has little connection to trampolines, bicycles or other healthy pursuits. Scholars say their favorite leisure activities are watching TV, playing video games or maybe both at the same time.

So I looked for that Sept. 1, 2020, article in my newspaper that McGrath mentioned. McGrath quoted Pope correctly. I missed that piece when it came out. Maybe most people did. I looked for Wikipedia’s official answer to this frequently asked question: How much time does the average teenager spend on homework?

I was horrified by what I saw, delivered to millions of Wikipedia users: “High schoolers reported doing an average of 2.7 hours of homework per weeknight, according to a study by The Washington Post from 2018 to 2020 of over 50,000 individuals.”

That’s wrong, but I am used to widespread falsehoods about homework overload. Otherwise responsible writers and filmmakers seem unable to resist adding to the hysteria. The popular 2009 film documentary “Race to Nowhere,” screened in 47 states and 20 countries, left the impression that young Americans everywhere were buckling under homework’s weight, yet the film never told viewers that the average amount is an just an hour a night.

Why ‘Race to Nowhere’ documentary is wrong

When Sara Bennett, an attorney and activist parent, and Nancy Kalish, a journalist specializing in parenting issues, went on the “Today” show in 2006 to publicize their book “The Case Against Homework: How Homework Is Hurting Our Children and What We Can Do About It,” they said the average homework load had “skyrocketed.” They used that same word in their book.

They were sensationalizing the fact that the average time 6-to-8-year-olds spent on homework went from eight minutes a day in 1981 to 22 minutes a day in 2003. That supposedly awful demand on their time was the equivalent of watching two episodes of “SpongeBob SquarePants.”

The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research reported in 2003 an average of 50 minutes of homework each weekday for 15-to-17-year-olds, based on a nationally representative sample of 2,907 children and adolescents. A 2019 report by the Pew Research Center , based on Bureau of Labor Statistics data, said 15-to-17- year-olds spent on average an hour a day on homework during the school year. The 2019 UCLA Higher Education Research Institute survey of 95,505 college freshmen reported 57 percent of those students, all good enough to get into college, recalled spending five hours or less a week on homework their senior year of high school. Research shows homework has little value in elementary school, but does correlate with higher achievement in high school.

The false notion of teenagers averaging 2.7 hours a night was incorrectly derived from a study by Challenge Success, a nonprofit organization that works on identifying problems and implementing best practices in schools. Pope, the author of the piece in my newspaper, is a co-founder of Challenge Success and a senior lecturer at the Stanford University Graduate School of Education.

Pope is a wonderful writer and scholar whom I have quoted in the past. She can’t be blamed for Wikipedia saying wrongly the Challenge Success study was done by The Post. She also tried to tell readers that her study did NOT use a representative sample of U.S. teens.

She said the students in the study were all from “high-performing schools.” I only wish she had revealed that in the same sentence that she reported the 2.7-hours-per-night homework average. Her note that the study was confined to the best schools appeared in a different paragraph. That may explain why McGrath, Wikipedia and careless people like me failed, at least on first reading, to see that the sample was skewed.

The Weak Case Against Homework

Too much homework can be a problem in high-achieving schools that cater to middle- and upper-class children. But they represent only about half the country. People on my side of the argument would say that three hours of homework a night is fine if the courses raise achievement and college readiness. I don’t think our kids’ favorite pastimes, video games and TV, are as good for them as going deep into those courses. And even three hours of homework leaves another three hours or so each night (plus the weekend) for nonacademic pursuits.

My concern is the less advantaged students who bring the national average down to just one hour a night by doing little or no homework at all. Since 1996 I have been studying hundreds of unusually dedicated public high schools in low-income communities that have raised achievement for their students and made it far more likely they will succeed in college or whatever they do after high school.

Those schools consider homework vital. One of them was led by Deborah Meier, a hero to many progressive educators. She created New York City’s Central Park East High School, where the mostly low-income students heard much about the importance of using time wisely.

“We told our kids … that the school’s explicit work probably required a 40-hour week — maybe more, maybe less,” she said to me. The official school week was about 30 hours. So she kept the school open an extra 10 hours a week — maybe an hour before school, an hour after school and Saturday mornings.

She didn’t call the extra time homework, but made clear it was essential. “Everyone had more to read than could be done while at school — mostly five-plus hours a week,” she said, “and probably another five for exploring and preparing and revising work done during school hours.”

Pope thinks in similar ways. She sees her Challenge Success research “as a way to a much larger conversation about how to create more meaningful and engaging learning, … how to add time for advisory/tutorial and more student to teacher interaction, how to make all the kids in the school feel like they belong and are cared for.”

That will require more than our puny national homework average of an hour a night, after an inadequate average of five hours of class a day. More learning takes time. One step in the right direction would be accepting the need for regular homework, particularly in high school, and dispensing with falsehoods about giving kids too much to learn.

How Much Homework Is Enough? Depends Who You Ask

- Share article

Editor’s note: This is an adapted excerpt from You, Your Child, and School: Navigate Your Way to the Best Education ( Viking)—the latest book by author and speaker Sir Ken Robinson (co-authored with Lou Aronica), published in March. For years, Robinson has been known for his radical work on rekindling creativity and passion in schools, including three bestselling books (also with Aronica) on the topic. His TED Talk “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” holds the record for the most-viewed TED talk of all time, with more than 50 million views. While Robinson’s latest book is geared toward parents, it also offers educators a window into the kinds of education concerns parents have for their children, including on the quality and quantity of homework.

The amount of homework young people are given varies a lot from school to school and from grade to grade. In some schools and grades, children have no homework at all. In others, they may have 18 hours or more of homework every week. In the United States, the accepted guideline, which is supported by both the National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association, is the 10-minute rule: Children should have no more than 10 minutes of homework each day for each grade reached. In 1st grade, children should have 10 minutes of daily homework; in 2nd grade, 20 minutes; and so on to the 12th grade, when on average they should have 120 minutes of homework each day, which is about 10 hours a week. It doesn’t always work out that way.

In 2013, the University of Phoenix College of Education commissioned a survey of how much homework teachers typically give their students. From kindergarten to 5th grade, it was just under three hours per week; from 6th to 8th grade, it was 3.2 hours; and from 9th to 12th grade, it was 3.5 hours.

There are two points to note. First, these are the amounts given by individual teachers. To estimate the total time children are expected to spend on homework, you need to multiply these hours by the number of teachers they work with. High school students who work with five teachers in different curriculum areas may find themselves with 17.5 hours or more of homework a week, which is the equivalent of a part-time job. The other factor is that these are teachers’ estimates of the time that homework should take. The time that individual children spend on it will be more or less than that, according to their abilities and interests. One child may casually dash off a piece of homework in half the time that another will spend laboring through in a cold sweat.

Do students have more homework these days than previous generations? Given all the variables, it’s difficult to say. Some studies suggest they do. In 2007, a study from the National Center for Education Statistics found that, on average, high school students spent around seven hours a week on homework. A similar study in 1994 put the average at less than five hours a week. Mind you, I [Robinson] was in high school in England in the 1960s and spent a lot more time than that—though maybe that was to do with my own ability. One way of judging this is to look at how much homework your own children are given and compare it to what you had at the same age.

Many parents find it difficult to help their children with subjects they’ve not studied themselves for a long time, if at all.

There’s also much debate about the value of homework. Supporters argue that it benefits children, teachers, and parents in several ways:

- Children learn to deepen their understanding of specific content, to cover content at their own pace, to become more independent learners, to develop problem-solving and time-management skills, and to relate what they learn in school to outside activities.

- Teachers can see how well their students understand the lessons; evaluate students’ individual progress, strengths, and weaknesses; and cover more content in class.

- Parents can engage practically in their children’s education, see firsthand what their children are being taught in school, and understand more clearly how they’re getting on—what they find easy and what they struggle with in school.

Want to know more about Sir Ken Robinson? Check out our Q&A with him.

Q&A With Sir Ken Robinson

Ashley Norris is assistant dean at the University of Phoenix College of Education. Commenting on her university’s survey, she says, “Homework helps build confidence, responsibility, and problem-solving skills that can set students up for success in high school, college, and in the workplace.”

That may be so, but many parents find it difficult to help their children with subjects they’ve not studied themselves for a long time, if at all. Families have busy lives, and it can be hard for parents to find time to help with homework alongside everything else they have to cope with. Norris is convinced it’s worth the effort, especially, she says, because in many schools, the nature of homework is changing. One influence is the growing popularity of the so-called flipped classroom.

In the stereotypical classroom, the teacher spends time in class presenting material to the students. Their homework consists of assignments based on that material. In the flipped classroom, the teacher provides the students with presentational materials—videos, slides, lecture notes—which the students review at home and then bring questions and ideas to school where they work on them collaboratively with the teacher and other students. As Norris notes, in this approach, homework extends the boundaries of the classroom and reframes how time in school can be used more productively, allowing students to “collaborate on learning, learn from each other, maybe critique [each other’s work], and share those experiences.”

Even so, many parents and educators are increasingly concerned that homework, in whatever form it takes, is a bridge too far in the pressured lives of children and their families. It takes away from essential time for their children to relax and unwind after school, to play, to be young, and to be together as a family. On top of that, the benefits of homework are often asserted, but they’re not consistent, and they’re certainly not guaranteed.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

How Much Homework Do American Kids Do?

Various factors, from the race of the student to the number of years a teacher has been in the classroom, affect a child's homework load.

![average high school homework time [IMAGE DESCRIPTION]](https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/img/posts/Ryan_Homework_Post.jpg)

In his Atlantic essay , Karl Taro Greenfeld laments his 13-year-old daughter's heavy homework load. As an eighth grader at a New York middle school, Greenfeld’s daughter averaged about three hours of homework per night and adopted mantras like “memorization, not rationalization” to help her get it all done. Tales of the homework-burdened American student have become common, but are these stories the exception or the rule?

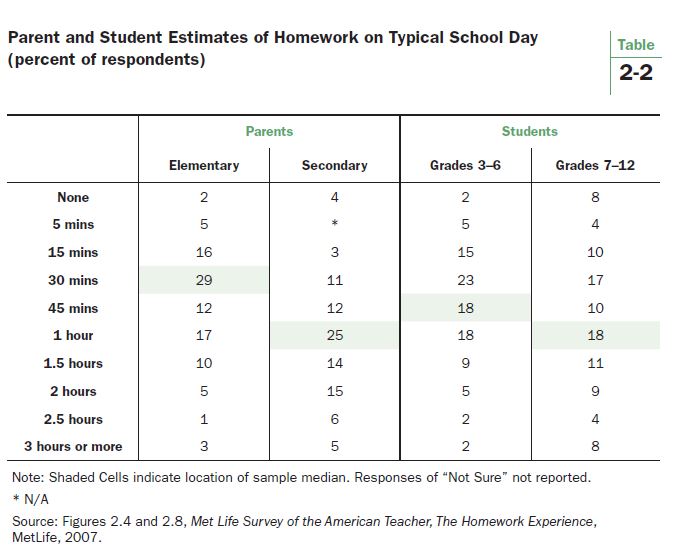

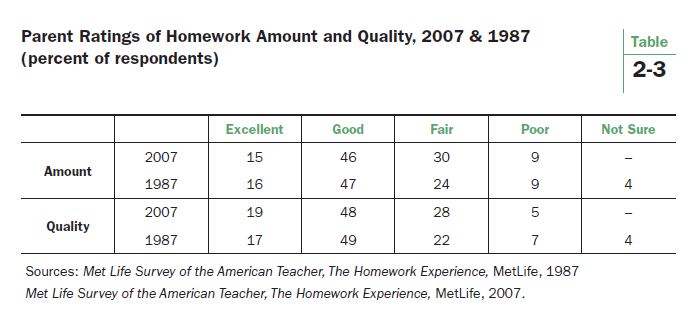

A 2007 Metlife study found that 45 percent of students in grades three to 12 spend more than an hour a night doing homework, including the six percent of students who report spending more than three hours a night on their homework. In the 2002-2003 school year, a study out of the University of Michigan found that American students ages six through 17 spent three hours and 38 minutes per week doing homework.

A range of factors plays into how much homework each individual student gets:

Older students do more homework than their younger counterparts.

This one is fairly obvious: The National Education Association recommends that homework time increase by ten minutes per year in school. (e.g., A third grader would have 30 minutes of homework, while a seventh grader would have 70 minutes).

Studies have found that schools tend to roughly follow these guidelines: The University of Michigan found that students ages six to eight spend 29 minutes doing homework per night while 15- to 17-year-old students spend 50 minutes doing homework. The Metlife study also found that 50 percent of students in grades seven to 12 spent more than an hour a night on homework, while 37 percent of students in grades three to six spent an hour or more on their homework per night. The National Center for Educational Statistics found that high school students who do homework outside of school average 6.8 hours of homework per week.

![average high school homework time [IMAGE DESCRIPTION]](https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/img/posts/Ryan_Homework_MetlifeGraph.jpg)

Race plays a role in how much homework students do.

Asian students spend 3.5 more hours on average doing homework per week than their white peers. However, only 59 percent of Asian students’ parents check that homework is done, while 75.6 percent of Hispanic students’ parents and 83.1 percent of black students’ parents check.

![average high school homework time [IMAGE DESCRIPTION]](https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/img/posts/Ryan_Homework_NCESGraph.jpg)

Teachers with less experience assign more homework.

The Metlife study found that 14 percent of teachers with zero to five years of teaching experience assigned more than an hour of homework per night, while only six percent of teachers with 21 or more years of teaching experience assigned over an hour of homework.

![average high school homework time [IMAGE DESCRIPTION]](https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/img/posts/Ryan_Homework_GraphTeachers.jpg)

Math classes have homework the most frequently.

The Metlife study found that 70 percent of students in grades three to 12 had at least one homework assignment in math. Sixty-two percent had at least one homework assignment in a language arts class (English, reading, spelling, or creative writing courses) and 42 percent had at least one in a science class.

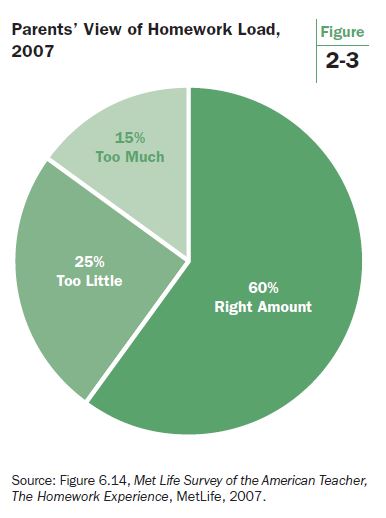

Regardless of how much homework kids are actually doing every night, most parents and teachers are happy with the way things are: 60 percent of parents think that their children have the “right amount of homework,” and 73 percent of teachers think their school assigns the right amount of homework.

Students, however, are not necessarily on board: 38 percent of students in grades seven through 12 and 28 percent of students in grades three through six report being “very often/often” stressed out by their homework.

Take the Quiz: Find the Best State for You »

What's the best state for you », students spend more time on homework but teachers say it's worth it.

Time spent on homework has increased in recent years, but educators say that's because the assignments have also changed.

Students Spending More Time on Homework

iStockphoto

High school students get assigned up to 17.5 hours of homework per week, according to a survey of 1,000 teachers.

Although students nowadays are spending significantly more time on homework assignments – sometimes up to 17.5 hours each week – the type and quality of the assignments have changed to better capture critical thinking skills and higher levels of learning, according to a recent survey of teachers conducted by the University of Phoenix College of Education.

The survey of 1,000 K-12 teachers found, among other things, that high school teachers on average assign about 3.5 hours of homework each week. For high school students who typically have five classes with different teachers, that could mean as much as 17.5 hours each week. By comparison, the survey found middle school teachers assign about 3.2 hours of homework each week and kindergarten through fifth grade teachers assign about 2.9 hours each week.

[ READ : Standardized Testing Debate Should Focus on Local School Districts, Report Says ]

By comparison, a 2011 study from the National Center for Education Statistics found high school students reported spending an average of 6.8 hours of homework per week, while a 1994 report from the National Center for Education Statistics – reviewing trends in data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress – found 39 percent of 17-year-olds said they did at least one hour of homework each day.

"What has changed is not necessarily the magic number of how many hours they’re doing per night, but it’s the quality of the homework," says Ashley Norris, assistant dean of the university's college of education. Part of that shift in recent years, she says, may come from more schools implementing the Common Core State Standards, which are intended to put more of an emphasis on critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

"You see a change from teachers … giving, really, busy work … to where they’re actually creating long-term projects that students have to manage outside of the classroom, or reading, where they read and come back into the classroom and share their findings," Norris says. "It's not just about rote memorization, because we know that doesn't stick."

For younger students, having more meaningful homework assignments can help build time-management skills, as well as enhance parent-child interaction, Norris says. But the bigger connection for high school students, she says, is doing assignments outside of the classroom that get them interested in a career path.

[ MORE : How Virtual Games Can Help Struggling Students Learn ]

Moving forward, as more schools dive into more time-consuming – but Norris says more meaningful – assignments, there may be a greater shift in the number of schools utilizing the "flipped classroom" method, in which students watch a lesson or lecture at home online, and bring their questions to the classroom to work with their peers while the teacher is present to help facilitate any problems that arise.

"This is already happening in the classrooms. And I think that idea, this whole idea where homework is this applied learning that goes outside the boundaries of a classroom – what can we use that actual class time for?" Norris says "To come back and collaborate on learning, learn from each other, maybe critique our own [work] and share those experiences."

Join the Conversation

Tags: K-12 education , education , Common Core , teachers

America 2024

Health News Bulletin

Stay informed on the latest news on health and COVID-19 from the editors at U.S. News & World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

Cartoons on President Donald Trump

Feb. 1, 2017, at 1:24 p.m.

Photos: Obama Behind the Scenes

April 8, 2022

Photos: Who Supports Joe Biden?

March 11, 2020

The Cicadas Are Coming: Grab Your Fork?

Laura Mannweiler May 10, 2024

U.S. Report Stings Israeli War Effort

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 10, 2024

Inflation, High Rates Spook Consumers

Tim Smart May 10, 2024

Stormy Daniels' Testimony Gets Heated

Laura Mannweiler and Lauren Camera May 9, 2024

How Rare Are Brain Worms Like RFK Jr.’s?

Laura Mannweiler May 8, 2024

QUOTES: Israel's Rafah Attack

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder May 8, 2024

- Our Mission

Research Trends: Why Homework Should Be Balanced

Research suggests that while homework can be an effective learning tool, assigning too much can lower student performance and interfere with other important activities.

Homework: effective learning tool or waste of time?

Since the average high school student spends almost seven hours each week doing homework, it’s surprising that there’s no clear answer. Homework is generally recognized as an effective way to reinforce what students learn in class, but claims that it may cause more harm than good, especially for younger students, are common.

Here’s what the research says:

- In general, homework has substantial benefits at the high school level, with decreased benefits for middle school students and few benefits for elementary students (Cooper, 1989; Cooper et al., 2006).

- While assigning homework may have academic benefits, it can also cut into important personal and family time (Cooper et al., 2006).

- Assigning too much homework can result in poor performance (Fernández-Alonso et al., 2015).

- A student’s ability to complete homework may depend on factors that are outside their control (Cooper et al., 2006; OECD, 2014; Eren & Henderson, 2011).

- The goal shouldn’t be to eliminate homework, but to make it authentic, meaningful, and engaging (Darling-Hammond & Ifill-Lynch, 2006).

Why Homework Should Be Balanced

Homework can boost learning, but doing too much can be detrimental. The National PTA and National Education Association support the “10-minute homework rule,” which recommends 10 minutes of homework per grade level, per night (10 minutes for first grade, 20 minutes for second grade, and so on, up to two hours for 12th grade) (Cooper, 2010). A recent study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90–100 minutes of homework per day, their math and science scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015). Giving students too much homework can lead to fatigue, stress, and a loss of interest in academics—something that we all want to avoid.

Homework Pros and Cons

Homework has many benefits, ranging from higher academic performance to improved study skills and stronger school-parent connections. However, it can also result in a loss of interest in academics, fatigue, and a loss of important personal and family time.

Grade Level Makes a Difference

Although the debate about homework generally falls in the “it works” vs. “it doesn’t work” camps, research shows that grade level makes a difference. High school students generally get the biggest benefits from homework, with middle school students getting about half the benefits, and elementary school students getting few benefits (Cooper et al., 2006). Since young students are still developing study habits like concentration and self-regulation, assigning a lot of homework isn’t all that helpful.

Parents Should Be Supportive, Not Intrusive

Well-designed homework not only strengthens student learning, it also provides ways to create connections between a student’s family and school. Homework offers parents insight into what their children are learning, provides opportunities to talk with children about their learning, and helps create conversations with school communities about ways to support student learning (Walker et al., 2004).

However, parent involvement can also hurt student learning. Patall, Cooper, and Robinson (2008) found that students did worse when their parents were perceived as intrusive or controlling. Motivation plays a key role in learning, and parents can cause unintentional harm by not giving their children enough space and autonomy to do their homework.

Homework Across the Globe

OECD , the developers of the international PISA test, published a 2014 report looking at homework around the world. They found that 15-year-olds worldwide spend an average of five hours per week doing homework (the U.S. average is about six hours). Surprisingly, countries like Finland and Singapore spend less time on homework (two to three hours per week) but still have high PISA rankings. These countries, the report explains, have support systems in place that allow students to rely less on homework to succeed. If a country like the U.S. were to decrease the amount of homework assigned to high school students, test scores would likely decrease unless additional supports were added.

Homework Is About Quality, Not Quantity

Whether you’re pro- or anti-homework, keep in mind that research gives a big-picture idea of what works and what doesn’t, and a capable teacher can make almost anything work. The question isn’t homework vs. no homework ; instead, we should be asking ourselves, “How can we transform homework so that it’s engaging and relevant and supports learning?”

Cooper, H. (1989). Synthesis of research on homework . Educational leadership, 47 (3), 85-91.

Cooper, H. (2010). Homework’s Diminishing Returns . The New York Times .

Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003 . Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1-62.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Ifill-Lynch, O. (2006). If They'd Only Do Their Work! Educational Leadership, 63 (5), 8-13.

Eren, O., & Henderson, D. J. (2011). Are we wasting our children's time by giving them more homework? Economics of Education Review, 30 (5), 950-961.

Fernández-Alonso, R., Suárez-Álvarez, J., & Muñiz, J. (2015, March 16). Adolescents’ Homework Performance in Mathematics and Science: Personal Factors and Teaching Practices . Journal of Educational Psychology. Advance online publication.

OECD (2014). Does Homework Perpetuate Inequities in Education? PISA in Focus , No. 46, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. C. (2008). Parent involvement in homework: A research synthesis . Review of Educational Research, 78 (4), 1039-1101.

Van Voorhis, F. L. (2003). Interactive homework in middle school: Effects on family involvement and science achievement . The Journal of Educational Research, 96 (6), 323-338.

Walker, J. M., Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Whetsel, D. R., & Green, C. L. (2004). Parental involvement in homework: A review of current research and its implications for teachers, after school program staff, and parent leaders . Cambridge, MA: Harvard Family Research Project.

US South Carolina

Recently viewed courses

Recently viewed.

Find Your Dream School

This site uses various technologies, as described in our Privacy Policy, for personalization, measuring website use/performance, and targeted advertising, which may include storing and sharing information about your site visit with third parties. By continuing to use this website you consent to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

COVID-19 Update: To help students through this crisis, The Princeton Review will continue our "Enroll with Confidence" refund policies. For full details, please click here.

Enter your email to unlock an extra $25 off an SAT or ACT program!

By submitting my email address. i certify that i am 13 years of age or older, agree to recieve marketing email messages from the princeton review, and agree to terms of use., homework wars: high school workloads, student stress, and how parents can help.

Studies of typical homework loads vary : In one, a Stanford researcher found that more than two hours of homework a night may be counterproductive. The research , conducted among students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities, found that too much homework resulted in stress, physical health problems and a general lack of balance.

Additionally, the 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education , found that with the exception of nine-year-olds, the amount of homework schools assign has remained relatively unchanged since 1984, meaning even those in charge of the curricula don't see a need for adding more to that workload.

But student experiences don’t always match these results. On our own Student Life in America survey, over 50% of students reported feeling stressed, 25% reported that homework was their biggest source of stress, and on average teens are spending one-third of their study time feeling stressed, anxious, or stuck.

The disparity can be explained in one of the conclusions regarding the Brown Report:

Of the three age groups, 17-year-olds have the most bifurcated distribution of the homework burden. They have the largest percentage of kids with no homework (especially when the homework shirkers are added in) and the largest percentage with more than two hours.

So what does that mean for parents who still endure the homework wars at home?

Read More: Teaching Your Kids How To Deal with School Stress

It means that sometimes kids who are on a rigorous college-prep track, probably are receiving more homework, but the statistics are melding it with the kids who are receiving no homework. And on our survey, 64% of students reported that their parents couldn’t help them with their work. This is where the real homework wars lie—not just the amount, but the ability to successfully complete assignments and feel success.

Parents want to figure out how to help their children manage their homework stress and learn the material.

Our Top 4 Tips for Ending Homework Wars

1. have a routine..

Every parenting advice article you will ever read emphasizes the importance of a routine. There’s a reason for that: it works. A routine helps put order into an often disorderly world. It removes the thinking and arguing and “when should I start?” because that decision has already been made. While routines must be flexible to accommodate soccer practice on Tuesday and volunteer work on Thursday, knowing in general when and where you, or your child, will do homework literally removes half the battle.

2. Have a battle plan.

Overwhelmed students look at a mountain of homework and think “insurmountable.” But parents can look at it with an outsider’s perspective and help them plan. Put in an extra hour Monday when you don’t have soccer. Prepare for the AP Chem test on Friday a little at a time each evening so Thursday doesn’t loom as a scary study night (consistency and repetition will also help lock the information in your brain). Start reading the book for your English report so that it’s underway. Go ahead and write a few sentences, so you don’t have a blank page staring at you. Knowing what the week will look like helps you keep calm and carry on.

3. Don’t be afraid to call in reserves.

You can’t outsource the “battle” but you can outsource the help ! We find that kids just do better having someone other than their parents help them —and sometimes even parents with the best of intentions aren’t equipped to wrestle with complicated physics problem. At The Princeton Review, we specialize in making homework time less stressful. Our tutors are available 24/7 to work one-to-one in an online classroom with a chat feature, interactive whiteboard, and the file sharing tool, where students can share their most challenging assignments.

4. Celebrate victories—and know when to surrender.

Students and parents can review completed assignments together at the end of the night -- acknowledging even small wins helps build a sense of accomplishment. If you’ve been through a particularly tough battle, you’ll also want to reach reach a cease-fire before hitting your bunk. A war ends when one person disengages. At some point, after parents have provided a listening ear, planning, and support, they have to let natural consequences take their course. And taking a step back--and removing any pressure a parent may be inadvertently creating--can be just what’s needed.

Stuck on homework?

Try an online tutoring session with one of our experts, and get homework help in 40+ subjects.

Try a Free Session

Explore Colleges For You

Connect with our featured colleges to find schools that both match your interests and are looking for students like you.

Career Quiz

Take our short quiz to learn which is the right career for you.

Get Started on Athletic Scholarships & Recruiting!

Join athletes who were discovered, recruited & often received scholarships after connecting with NCSA's 42,000 strong network of coaches.

Best 389 Colleges

165,000 students rate everything from their professors to their campus social scene.

SAT Prep Courses

1400+ course, act prep courses, free sat practice test & events, 1-800-2review, free digital sat prep try our self-paced plus program - for free, get a 14 day trial.

Free MCAT Practice Test

I already know my score.

MCAT Self-Paced 14-Day Free Trial

Enrollment Advisor

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 1

1-877-LEARN-30

Mon-Fri 9AM-10PM ET

Sat-Sun 9AM-8PM ET

Student Support

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 2

Mon-Fri 9AM-9PM ET

Sat-Sun 8:30AM-5PM ET

Partnerships

- Teach or Tutor for Us

College Readiness

International

Advertising

Affiliate/Other

- Enrollment Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility

- Cigna Medical Transparency in Coverage

Register Book

Local Offices: Mon-Fri 9AM-6PM

- SAT Subject Tests

Academic Subjects

- Social Studies

Find the Right College

- College Rankings

- College Advice

- Applying to College

- Financial Aid

School & District Partnerships

- Professional Development

- Advice Articles

- Private Tutoring

- Mobile Apps

- Local Offices

- International Offices

- Work for Us

- Affiliate Program

- Partner with Us

- Advertise with Us

- International Partnerships

- Our Guarantees

- Accessibility – Canada

Privacy Policy | CA Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information | Your Opt-Out Rights | Terms of Use | Site Map

©2024 TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. All Rights Reserved. The Princeton Review is not affiliated with Princeton University

TPR Education, LLC (doing business as “The Princeton Review”) is controlled by Primavera Holdings Limited, a firm owned by Chinese nationals with a principal place of business in Hong Kong, China.

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

Homework in High School: How Much Is Too Much?

Please try again

It’s not hard to find a high school student who is stressed about homework. Many are stressed to the max–juggling extracurricular activities, jobs, and family responsibilities. It can be hard for many students, particularly low-income students, to find the time to dedicate to homework. So students in the PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs program at YouthBeat in Oakland, California are asking what’s a fair amount of homework for high school students?

TEACHERS: Guide your students to practice civil discourse about current topics and get practice writing CER (claim, evidence, reasoning) responses. Explore lesson supports.

Is homework beneficial to students?

The homework debate has been going on for years. There’s a big body of research that shows that homework can have a positive impact on academic performance. It can also help students prepare for the academic rigors of college.

Does homework hurt students?

Some research suggests that homework is only beneficial up to a certain point. Too much homework can lead to compromised health and greater stress in students. Many students, particularly low-income students, can struggle to find the time to do homework, especially if they are working jobs after school or taking care of family members. Some students might not have access to technology, like computers or the internet, that are needed to complete assignments at home– which can make completing assignments even more challenging. Many argue that this contributes to inequity in education– particularly if completing homework is linked to better academic performance.

How much homework should students get?

Based on research, the National Education Association recommends the 10-minute rule stating students should receive 10 minutes of homework per grade per night. But opponents to homework point out that for seniors that’s still 2 hours of homework which can be a lot for students with conflicting obligations. And in reality, high school students say it can be tough for teachers to coordinate their homework assignments since students are taking a variety of different classes. Some people advocate for eliminating homework altogether.

Edweek: How Much Homework Is Enough? Depends Who You Ask

Business Insider: Here’s How Homework Differs Around the World

Review of Educational Research: Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Research, 1987-2003

Phys.org: Study suggests more than two hours of homework a night may be counterproductive

The Journal of Experimental Education: Nonacademic Effects of Homework in Privileged, High-Performing High Schools

National Education Association: Research Spotlight on Homework NEA Reviews of the Research on Best Practices in Education

The Atlantic: Who Does Homework Work For?

Center for Public Education: What research says about the value of homework: Research review

Time: Opinion: Why I think All Schools Should Abolish Homework

The Atlantic: A Teacher’s Defense of Homework

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

The way U.S. teens spend their time is changing, but differences between boys and girls persist

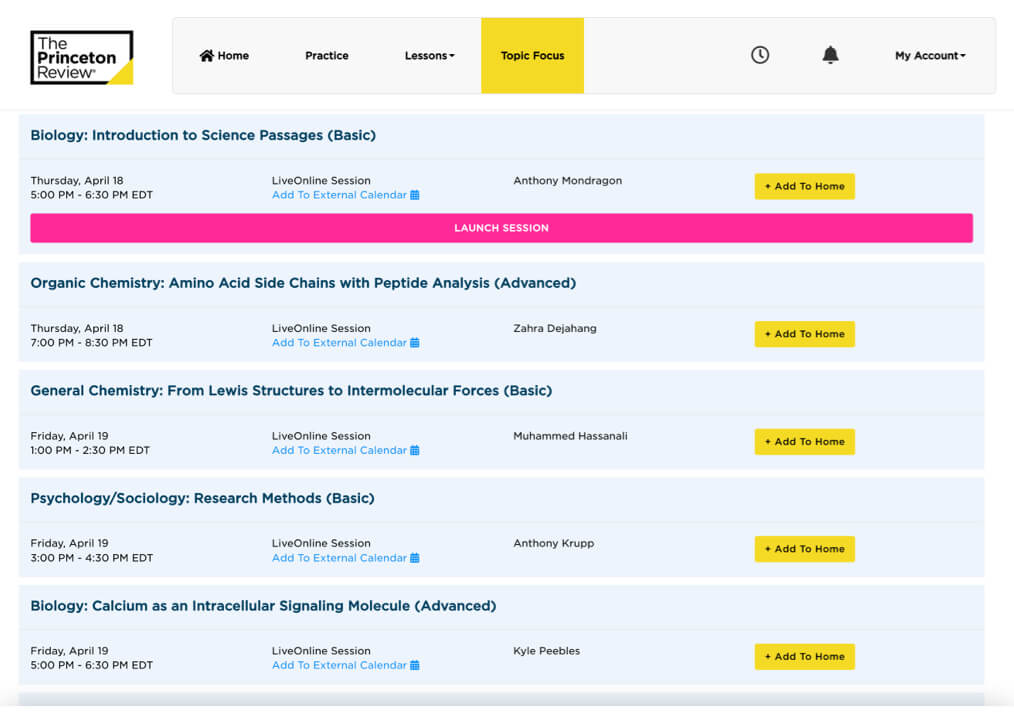

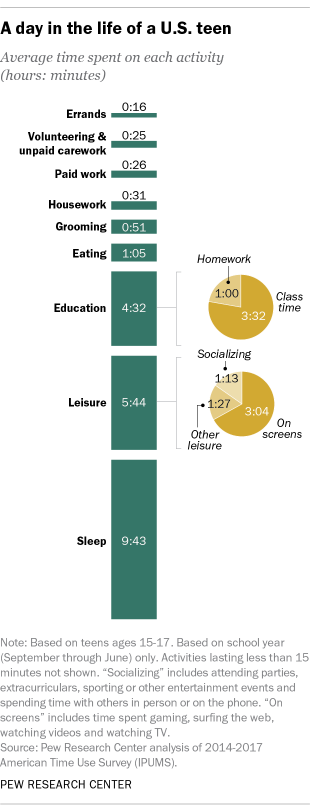

Teens today are spending their time differently than they did a decade ago. They’re devoting more time to sleep and homework, and less time to paid work and socializing. But what has not changed are the differences between teen boys and girls in time spent on leisure, grooming, homework, housework and errands, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Overall, teens (ages 15 to 17) spend an hour a day, on average, doing homework during the school year, up from 44 minutes a day about a decade ago and 30 minutes in the mid-1990s.

Teens are also getting more shut-eye than they did in the past. They are clocking an average of over nine and a half hours of sleep a night, an increase of 22 minutes compared with teens a decade ago and almost an hour more than those in the mid-1990s. Sleep patterns fluctuate quite a bit – on weekends, teens average about 11 hours, while on weekdays they typically get just over nine hours a night. (While these findings are derived from time diaries in which respondents record the amount of time they slept on the prior night, results from other types of surveys suggest teens are getting fewer hours of sleep .)

Teens now enjoy more than five and a half hours of leisure a day (5 hours, 44 minutes). The biggest chunk of teens’ daily leisure time is spent on screens: 3 hours and 4 minutes on average. This figure, which can include time spent gaming, surfing the web, watching videos and watching TV, has held steady over the past decade. On weekends, screen time increases to almost four hours a day (3 hours, 53 minutes), and on weekdays teens are spending 2 hours and 44 minutes on screens.

Time spent playing sports has held steady at around 45 minutes, as has the time teens spend in other types of leisure such as shopping for clothes, listening to music and reading for pleasure.

Time spent by teens in other leisure activities has declined. Over the past decade, the time spent socializing – including attending parties, extracurriculars, sporting or other entertainment events as well as spending time with others in person or on the phone – has dropped by 16 minutes, to 1 hour and 13 minutes a day.

Teens also are spending less time on paid work during the school year than their predecessors: 26 minutes a day, on average, compared with 49 minutes about a decade ago and 57 minutes in the mid-1990s. Much of this decline reflects the fact that teens are less likely to work today than in the past; among employed teens, the amount of time spent working is not much different now than it was around 2005.

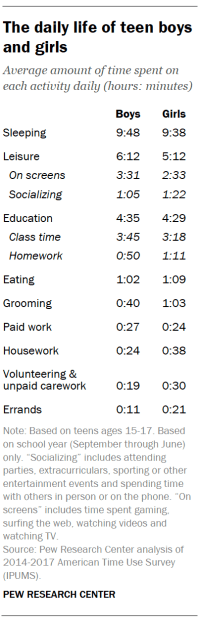

While the way teens overall spend their time has changed in a number of ways, persistent gender differences in time use remain. Teen boys are spending an average of about six hours a day in leisure time, compared with roughly five hours a day for girls – driven largely by the fact that boys are spending about an hour (58 minutes) more a day than girls engaged in screen time. Boys also spend more time playing sports: 59 minutes vs. 33 minutes for girls.

On the flip side, girls spend 10 more minutes a day, on average, shopping for items such as clothes or going to the mall (15 minutes vs. 5 minutes).

Teen girls also spend more time than boys on grooming activities, such as bathing, getting dressed, getting haircuts, and other activities related to their hygiene and appearance. Girls spend an average of about an hour a day on these types of tasks (1 hour, 3 minutes); boys spend 40 minutes on them.

Girls also devote 21 more minutes a day to homework than boys do – 71 minutes vs. 50 minutes, on average, during the school year. This pattern has held steady over the past decade, as the amount of time spent on homework has risen equally for boys and girls.

When it comes to the amount of time spent on housework, the differences between boys and girls reflect gender dynamics that are also evident among adults . Teenage girls spend 38 minutes a day, on average, helping around the house during the school year, compared with 24 minutes a day for boys. The bulk of this gap is driven by the fact that girls spend more than twice as much time cleaning up and preparing food as boys do (29 minutes vs. 12 minutes). There are not significant differences in the amount of time boys and girls spend on home maintenance and lawn care.

Girls also spend more time running errands, such as shopping for groceries (21 minutes vs. 11 minutes for boys).

In addition to these differences in how they spend their time, the way boys and girls feel about their day also differs in some key ways. A new survey by Pew Research Center of teens ages 13 to 17 finds that 36% of girls say they feel tense or nervous about their day every or almost every day; 23% of boys say the same. At the same time, girls are more likely than boys to say they get excited daily or almost daily by something they study in school (33% vs. 21%). And while similar shares of boys and girls say they feel a lot of pressure to get good grades, be involved in extracurricular activities or fit in socially, girls are more likely than boys to say they face a lot of pressure to look good (35% vs. 23%).

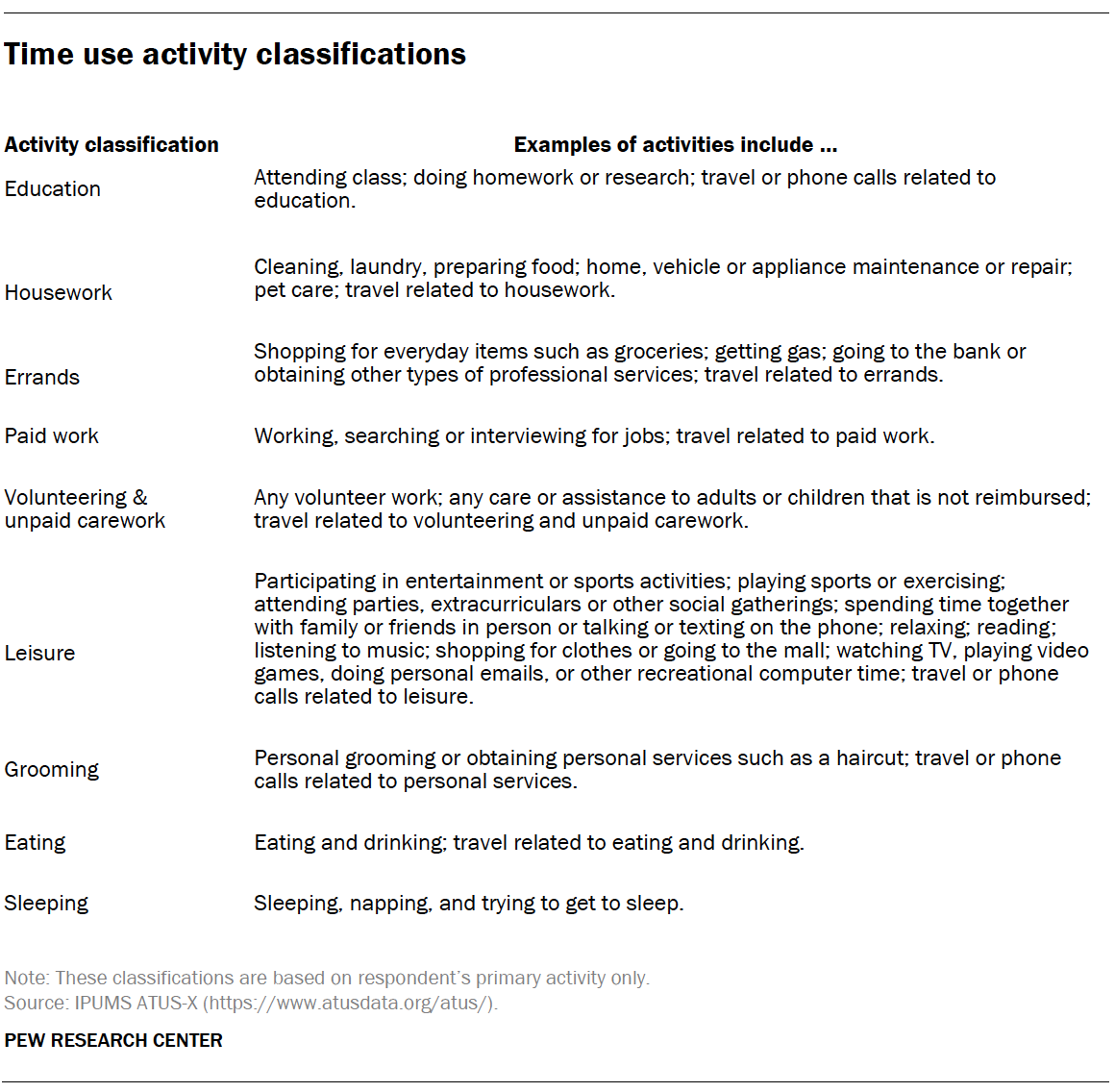

This analysis is based primarily on time diary data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), which has been sponsored by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and annually conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau since 2003. The ATUS produces a nationally representative sample of respondents, drawn from the Current Population Survey.

Most of the analyses are based on respondents in the 2003-2006 and the 2014-2017 ATUS samples (referred to in the text as “2005” and “2015”). Data regarding time use in the mid-1990s is based on 1992-1994 data from the American Heritage Time Use Survey (AHTUS). For all time points, multiple years of data were combined in order to increase sample size. Because time use among teens can vary so much between the summer and the school year, only data for September through June are used for these analyses. Although focused on the school year, the data also reflect time use during school holidays, such as spring break.

These time diaries track in detail how Americans spend their time, focusing on each respondent’s primary activity (i.e., the main thing they were doing) sequentially for the prior day, including the start and end times for each activity.

All data were accessed via the ATUS-X website made available through IPUMS .

- Age & Generations

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Generation Z

- Teens & Tech

- Teens & Youth

Gretchen Livingston is a former senior researcher focusing on fertility and family demographics at Pew Research Center .

Teens and Video Games Today

As biden and trump seek reelection, who are the oldest – and youngest – current world leaders, how teens and parents approach screen time, who are you the art and science of measuring identity, u.s. centenarian population is projected to quadruple over the next 30 years, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Homework in America

- 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education

Subscribe to the Brown Center on Education Policy Newsletter

Tom loveless tom loveless former brookings expert @tomloveless99.

March 18, 2014

- 18 min read

Part II of the 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education

Homework! The topic, no, just the word itself, sparks controversy. It has for a long time. In 1900, Edward Bok, editor of the Ladies Home Journal , published an impassioned article, “A National Crime at the Feet of Parents,” accusing homework of destroying American youth. Drawing on the theories of his fellow educational progressive, psychologist G. Stanley Hall (who has since been largely discredited), Bok argued that study at home interfered with children’s natural inclination towards play and free movement, threatened children’s physical and mental health, and usurped the right of parents to decide activities in the home.

The Journal was an influential magazine, especially with parents. An anti-homework campaign burst forth that grew into a national crusade. [i] School districts across the land passed restrictions on homework, culminating in a 1901 statewide prohibition of homework in California for any student under the age of 15. The crusade would remain powerful through 1913, before a world war and other concerns bumped it from the spotlight. Nevertheless, anti-homework sentiment would remain a touchstone of progressive education throughout the twentieth century. As a political force, it would lie dormant for years before bubbling up to mobilize proponents of free play and “the whole child.” Advocates would, if educators did not comply, seek to impose homework restrictions through policy making.

Our own century dawned during a surge of anti-homework sentiment. From 1998 to 2003, Newsweek , TIME , and People , all major national publications at the time, ran cover stories on the evils of homework. TIME ’s 1999 story had the most provocative title, “The Homework Ate My Family: Kids Are Dazed, Parents Are Stressed, Why Piling On Is Hurting Students.” People ’s 2003 article offered a call to arms: “Overbooked: Four Hours of Homework for a Third Grader? Exhausted Kids (and Parents) Fight Back.” Feature stories about students laboring under an onerous homework burden ran in newspapers from coast to coast. Photos of angst ridden children became a journalistic staple.

The 2003 Brown Center Report on American Education included a study investigating the homework controversy. Examining the most reliable empirical evidence at the time, the study concluded that the dramatic claims about homework were unfounded. An overwhelming majority of students, at least two-thirds, depending on age, had an hour or less of homework each night. Surprisingly, even the homework burden of college-bound high school seniors was discovered to be rather light, less than an hour per night or six hours per week. Public opinion polls also contradicted the prevailing story. Parents were not up in arms about homework. Most said their children’s homework load was about right. Parents wanting more homework out-numbered those who wanted less.

Now homework is in the news again. Several popular anti-homework books fill store shelves (whether virtual or brick and mortar). [ii] The documentary Race to Nowhere depicts homework as one aspect of an overwrought, pressure-cooker school system that constantly pushes students to perform and destroys their love of learning. The film’s website claims over 6,000 screenings in more than 30 countries. In 2011, the New York Times ran a front page article about the homework restrictions adopted by schools in Galloway, NJ, describing “a wave of districts across the nation trying to remake homework amid concerns that high stakes testing and competition for college have fueled a nightly grind that is stressing out children and depriving them of play and rest, yet doing little to raise achievement, especially in elementary grades.” In the article, Vicki Abeles, the director of Race to Nowhere , invokes the indictment of homework lodged a century ago, declaring, “The presence of homework is negatively affecting the health of our young people and the quality of family time.” [iii]

A petition for the National PTA to adopt “healthy homework guidelines” on change.org currently has 19,000 signatures. In September 2013, Atlantic featured an article, “My Daughter’s Homework is Killing Me,” by a Manhattan writer who joined his middle school daughter in doing her homework for a week. Most nights the homework took more than three hours to complete.

The Current Study

A decade has passed since the last Brown Center Report study of homework, and it’s time for an update. How much homework do American students have today? Has the homework burden increased, gone down, or remained about the same? What do parents think about the homework load?

A word on why such a study is important. It’s not because the popular press is creating a fiction. The press accounts are built on the testimony of real students and real parents, people who are very unhappy with the amount of homework coming home from school. These unhappy people are real—but they also may be atypical. Their experiences, as dramatic as they are, may not represent the common experience of American households with school-age children. In the analysis below, data are analyzed from surveys that are methodologically designed to produce reliable information about the experiences of all Americans. Some of the surveys have existed long enough to illustrate meaningful trends. The question is whether strong empirical evidence confirms the anecdotes about overworked kids and outraged parents.

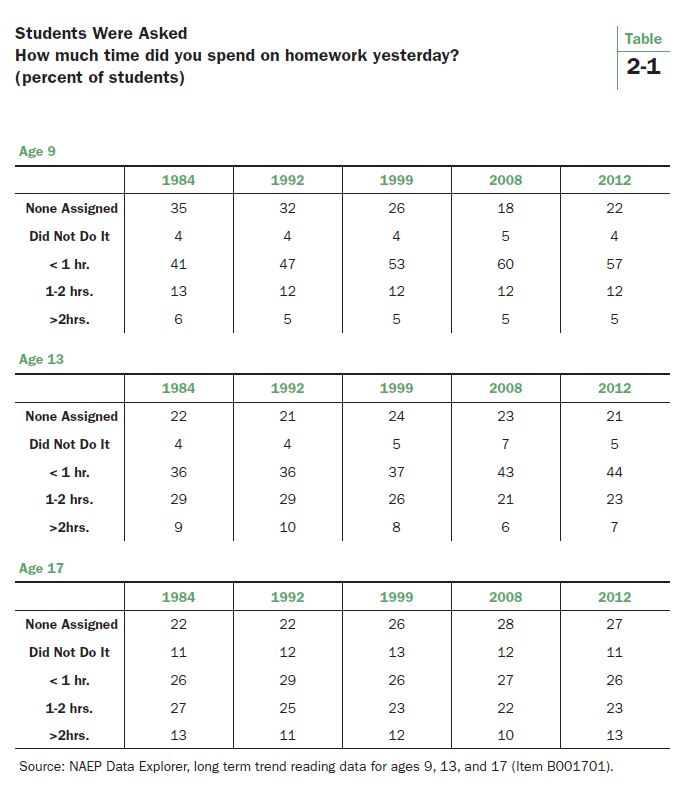

Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) provide a good look at trends in homework for nearly the past three decades. Table 2-1 displays NAEP data from 1984-2012. The data are from the long-term trend NAEP assessment’s student questionnaire, a survey of homework practices featuring both consistently-worded questions and stable response categories. The question asks: “How much time did you spend on homework yesterday?” Responses are shown for NAEP’s three age groups: 9, 13, and 17. [iv]