- International

Live updates: Sam Bankman-Fried found guilty in fraud trial

From CNN's Allison Morrow

What is Alameda, the hedge fund that brought down FTX?

Alameda Research, a hedge-fund-like crypto trading house that Bankman-Fried launched in 2017, played a pivotal role in FTX's downfall.

Almost as soon as FTX was created in 2019, former CEO Sam Bankman-Fried ordered co-founder Gary Wang to and Chief Technology Officer Nishad Singh to tweak the platform’s code to allow Alameda, as a customer on the exchange, certain “special privileges” that other customers lacked, according to Wang’s testimony.

Both Wang and Singh pleaded guilty to financial crimes as part of a plea deal with the government.

Those privileges included a virtually unlimited line of credit for Alameda that its executives could tap at any time, Wang testified. Alameda’s main trading account was also given an “allow negative” flag, meaning it could incur a negative balance without repercussion – a privilege that no other FTX customer was granted, Wang testified.

A stunning downfall for what was the most trusted name in crypto

The guilty verdict for former FTX CEO Sam Bankman-Fried comes a year after the crypto exchange entered a death spiral that fueled a panic in the trillion-dollar crypto industry and left an estimated 1 million customers facing potential losses. Prior to its collapse, the exchange attracted millions of users and a coterie of A-list backers, such as Tom Brady and Gisele Bundchen.

FTX, founded by Bankman-Fried in 2019, billed itself as a safe and easy way to start trading cryptocurrencies – digital assets whose values are based largely on a collective hope for their future application, which remains murky.

In the early 2020s, with interest rates at zero and millions of amateur investors stuck at home, FTX’s popularity as a crypto portal skyrocketed. By 2022, FTX was airing Super Bowl ads and plastering its name on the Miami Heat’s arena.

But FTX collapsed into bankruptcy on November 11, 2022 after what was effectively a run on the bank – a customer panic sparked by a leaked document that suggested irregular financial dealings between FTX and another firm owned by Bankman-Fried.

But, unlike bank customers, FTX depositors had no federal insurance fund to compensate them when the cash dried up. And despite FTX’s public assurances that it didn’t invest or move customer deposits in any way, Bankman-Fried’s other firm had been secretly siphoning deposits to repay its own lenders, underwrite executives’ luxury lifestyles, gamble in crypto markets and funnel millions of dollars in US political campaigns.

Guilty on all counts

Sam Bankman-Fried was found guilty on all seven counts for his role in the collapse of crypto exchange FTX.

Jurors deliberated from 3:15 pm ET to 7:45 pm ET.

The former crypto billionaire was found guilty of:

Count one: Wire fraud on customers of FTX

Count two: Conspiracy to commit wire fraud on customers of FTX

Count three: Wire fraud on Alameda Research lenders

Count four: Conspiracy to commit wire fraud on lenders to Alameda Research

Count five: Conspiracy to commit securities fraud on investors in FTX

Count six: Conspiracy to commit commodities fraud on customers of FTX

Count seven: Conspiracy to commit money laundering

SBF's fate lay in a jury of his peers

Over the past four weeks in a Manhattan federal court, 12 jurors and five alternates sat through more than 60 hours of testimony about the rise and fall of a multibillion-dollar crypto business empire and the person at the center of it all.

Judge Lewis Kaplan read instructions to the jury on Thursday morning, explaining each of the seven counts against Bankman-Fried before sending jurors off to deliberate.

Throughout the trial, prosecutors told the jury that 31-year-old Bankman-Fried orchestrated a yearslong fraud — building a “pyramid of deceit” — that ultimately crumbled when the market soured and his luck ran out.

Bankman-Fried has pleaded not guilty to seven federal counts of fraud and conspiracy, and he has broadcast to just about anyone who’ll listen his version of the events that landed both companies in bankruptcy. According to him, the mistakes that brought down FTX and Alameda were innocent — the kind of sloppy errors that startups are prone to.

Chief among those errors, according to his own testimony, was was not hiring a dedicated risk management team.

“I made a number of small mistakes and a number of larger mistakes,” Bankman-Fried said on the stand last week. “By far the biggest mistake was we did not have a dedicated risk management team, we didn’t have a chief risk officer.”

But on Thursday, US Assistant Attorney Danielle Sassoon described that as a strategy rather than a mistake.

“When you’re embezzling customer money, of course you’re not going to hire a risk officer,” she said.

Lead defense attorney Mark Cohen told the jury that the government’s portrayal of his client as a “movie villain” was wrong. Although Bankman-Fried made mistakes, he never defrauded anyone, Cohen told jurors.

“In the real world — unlike the movie world — things can get messy,” Cohen said. “Poor risk management is not a crime.”

How we got here

The verdict is set to come almost a year after FTX entered a death spiral that fueled a panic in the trillion-dollar crypto industry and left an estimated 1 million customers facing potential losses.

Prior to its collapse, the exchange attracted millions of users and a coterie of A-list backers, such as Tom Brady and Gisele Bundchen.

FTX, founded by Bankman-Fried in 2019, billed itself as a safe and easy way to start trading cryptocurrencies — digital assets whose values are based largely on a collective hope for their future application, which remains murky.

But FTX collapsed into bankruptcy on November 11, 2022.

A word about the prosecutors

The collapse of FTX fell to the Southern District of New York, widely known as an elite organization packed with some of the nation’s top lawyers. Its nickname is the “Sovereign District of New York.”

“People who work in the Southern District went to the best law schools, were elected to law reviews and clerked for federal judges,” Nicholas Lemann wrote in the New Yorker in 2013. “They prosecute the biggest, baddest, scariest criminals: evil billionaires, the Mafia, drug gangs, terrorists.”

“When [the Southern District of New York] gets involved, if there is criminality, odds are that they will make the case aggressively, prosecute it and secure a conviction,” Samson Enzer, a partner at Cahill Gordon & Reindel, told CNN last year. “They rarely fail.”

US Assistant Attorney Danielle Sassoon lead the government's cross-examination in Bankman-Fried's trial.

Sassoon was a law clerk to Justice Antonin Scalia, whom she said taught her "how to fire a pistol and a rifle, and made me feel like I had grit," she wrote in 2016.

Sassoon received her law degree from Yale and has a bachelor's degree in History and Literature from Harvard.

SBF didn't follow basic legal advice: Don't talk

In the weeks after his crypto empire collapsed, Sam Bankman-Fried ignored the most fundamental legal advice that any lawyer — or even a casual viewer of TV crime procedurals — would give: Shut your mouth.

Instead, SBF went on an apology tour, variously tweeting, DM-ing, and giving recorded interviews with reporters, repeatedly admitting that he “f**ked up.”

“What SBF is doing is a form of litigation suicide,” Howard Fischer, a former Securities and Exchange Commission lawyer told CNN last year. “Everything he says that turns out to be contradicted by admissible evidence will be taken as evidence of deceit … I don’t know if this is a sign of unrepentant arrogance, youthful overconfidence, or simply sheer stupidity.”

How SBF was arrested

Bankman-Fried was arrested in the Bahamas on December 12, 2022, after US prosecutors filed criminal charges against him.

The Southern District of New York, which is investigating Bankman-Fried and the collapse of FTX and its sister trading firm Alameda, confirmed his arrest on Twitter.

“Earlier this evening, Bahamian authorities arrested Samuel Bankman-Fried at the request of the US government, based on a sealed indictment filed by the SDNY,” wrote US attorney Damian Williams. “We expect to move to unseal the indictment in the morning and will have more to say at that time.”

The United States’ extradition treaty with the Bahamas allows US prosecutors to return defendants to American soil if the charges would be considered punishable by imprisonment of at least a year in both jurisdictions.

How FTX customers lost their money

In November last year, FTX suffered a run on the bank — a customer panic sparked by a leaked document that suggested irregular financial dealings between FTX and Alameda Research, a hedge fund owned by Bankman-Fried.

But, unlike bank customers, FTX depositors had no federal insurance fund to compensate them when the cash dried up.

And, despite FTX’s public assurances that it didn’t invest or move customer deposits in any way, Bankman-Fried’s other firm had been secretly siphoning deposits to repay its own lenders, underwrite executives’ luxury lifestyles, gamble in crypto markets and funnel millions of dollars to US political campaigns.

Please enable JavaScript for a better experience.

Alameda’s paper trail leads straight to Sam Bankman-Fried

And his “very valuable” hair, too..

By Elizabeth Lopatto , a reporter who writes about tech, money, and human behavior. She joined The Verge in 2014 as science editor. Previously, she was a reporter at Bloomberg.

Share this story

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24995990/236817_SBF_Trial_Stock_CAROLINE_ELLISON_B_CVirginia.jpg)

Sam Bankman-Fried wasn’t just a crypto wunderkind, he was an ambassador for improving the world through effective altruism . And if you were wondering how he squared those values with all the lying he allegedly did during his time at FTX, wonder no more: the answer is utilitarianism.

Lying and stealing were permitted, as “the only moral rule that mattered would be maximal utility,” Caroline Ellison testified on her second day at Bankman-Fried’s fraud trial . I glanced over at his parents, Joseph Bankman and Barbara Fried, to see what they made of this; both appeared to be busy scribbling into legal pads. In any case, the approach apparently worked for much of Bankman-Fried’s life — right up to demanding doctored balance sheets for the company Ellison supposedly ran.

Bankman-Fried’s cavalier attitude toward lying rubbed off on her, Ellison testified. Ellison choked up a little as she went on: “When I started working at Alameda, I don’t think I would have believed you if you told me I would be sending false balance sheets to our lenders, or taking customer money, but over time, it was something I became more comfortable with.” Later, testifying about the days when the crypto hedge fund Alameda Research and exchange FTX fell, she cried.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24960034/236817_SBF_Trial_Stock_CVirginia_D.jpg)

Sam Bankman-Fried, the founder of failed cryptocurrency exchange FTX, has been found guilty on seven counts including charges of wire fraud. FTX was a fraud “ from the start, ” the Securities and Exchange Commission alleged — with a “multi-billion-dollar deficiency caused by his own misappropriation of customer funds.”

Follow along for all the latest news and regular updates from the trial .

Ellison’s second day of testimony delved into the collapse of Bankman-Fried’s empire. Though she answered her questions with the attitude of a student trying to get an A in a difficult class, during court sidebars — where the lawyers bickered with each other in front of the judge and out of earshot of the rest of us — she slumped into herself, looking forlorn. She wore a gray blazer over a white v-neck blouse with black dots tucked into a black skirt, and she still didn’t quite summon up the appearance of an executive. That made sense. The text messages we saw suggested she made few consequential moves without first consulting Bankman-Fried — not exactly a real CEO.

The day picked up with Ellison discussing May 2022, when crypto markets entered freefall as the Terra/Luna coins collapsed . Amid the chaos, lenders started demanding their funds back. We saw Telegram chats with employees at Genesis, a crypto lender, which was asking Alameda to return its money. There was a tick-tock of Alameda getting its loans called by lenders across the board. In June, Bankman-Fried directed Ellison to repay the loans using FTX customer funds, she said.

“I was in sort of a constant state of dread at that point.”

Ellison knew this likely wasn’t possible. FTX customer funds had been used to pay off those loans, she testified. If a large number of FTX customers withdrew all at once, the exchange wouldn’t have the money. “I was really stressed out,” Ellison said. “I was in sort of a constant state of dread at that point.”

Bankman-Fried’s defense lawyers seem to be teeing up the notion that the customer funds were still there, just in an investment portfolio. The problem is that putting those funds in an investment portfolio is still stealing the funds . Crypto exchanges aren’t banks; they don’t lend out customer money. At least, the honest ones don’t.

During opening statements, the defense suggested that the failures at Alameda were Ellison’s fault — and that Bankman-Fried acted appropriately given what he knew at the time. In order to prove fraud occurred, the prosecution must show that Bankman-Fried knowingly lied. And Bankman-Fried was cagey about what he put in print. He had the company set their Slack and Signal messages to disappear, resulting in a lot of blank Signal chats in previous court exhibits, and again today.

During opening statements, the defense suggested that the failures at Alameda were Ellison’s fault

Ellison said he told her not to put anything in writing that she wouldn’t want to see on the front page of The New York Times . She violated that rule with a set of memos about their relationship. Later, Bankman-Fried would literally leak them to that paper .

Still, it’s impossible to run a business without documents. So today we saw a lot of documents that back Ellison’s claims that she worked at Bankman-Fried’s direction, even if we didn’t actually see his directions.

Part of Ellison’s job was pulling together balance sheets — by definition, writing something down. Alameda’s original balance sheets included a row called “FTX borrows,” which she said marked the customer funds. She says she wanted to identify it — but didn’t feel she could do so directly. That original balance sheet did contain $4.59 billion in related-party loans to Bankman-Fried, Gary Wang, Nishad Singh, and others. This is where the justified lying came in.

Alameda tried opening accounts using the IDs of “Thai prostitutes”

In an attempt to “conceal the things on our balance sheet we thought looked bad,” Ellison says she made seven fake balance sheets to run by Bankman-Fried. The one we saw was dated June 19th, 2022. The “FTX borrows” and related party loans had vanished. Some of the money that Alameda had borrowed from FTX was put in long-term loans — a second lie on top of the first, since customers could withdraw at any time.

The balance sheet Bankman-Fried chose made Alameda look less risky than it really was and hid the FTX funds, Ellison testified. She sent the balance sheet to a contact at Genesis, the crypto lender, the next day. That person replied that he’d “just caught up with Sam btw” and suggested that they stay “in tight contact this week.” She was asked to repay $500 million in loans because Genesis was “basically in the position where this is no longer a luxury.”

Ellison offered some other examples of Bankman-Fried’s apparently casual attitude toward lying. For instance, when Alameda funds got stuck on two Chinese exchanges, Huobi and OKX, Bankman-Fried first tried using a lawyer to negotiate. When that failed, Alameda tried opening accounts using the IDs of “Thai prostitutes” in order to create transactions that would get the funds back. We didn’t get a lot of detail about that except that it didn’t work, and I nearly expired from curiosity right there in the courtroom.

Finally, Bankman-Fried directed the company to pay a bribe, over the objections of a Chinese employee, who Ellison says he told to “shut the fuck up.” Later, Bankman-Fried and another Alameda executive would mock that employee on Signal.

He also thought his famously wild hair was “very valuable”

Ellison also testified that Bankman-Fried’s famously slovenly personal appearance was an act of careful public relations. He wanted to project the image of a smart, competent, and somewhat eccentric founder. He found Twitter particularly valuable for controlling the narrative, she said. Bankman-Fried also made investments in Semafor and The Block, and considered investments in Vox and Forbes, she testified. (Ellison didn’t testify to this, but Bankman-Fried’s philanthropic foundation, Building a Stronger Future, awarded our sister website Vox a grant for a reporting project.)

“He said he believed in a very proactive approach to public relations,” she said. He also thought his famously wild hair was “very valuable” and had led to higher bonuses at Jane Street, she testified. In the courtroom, Bankman-Fried visibly shook while she said this. Though Ellison and Bankman-Fried initially had “luxury cars,” Bankman-Fried felt it would be better for his image to drive a Toyota Corolla, so he switched cars.

At least he did really sleep on a bean bag in the office, according to Ellison. This had been thrown into question by Bankman-Fried’s college roommate in earlier testimony .

Because PR was so important to Bankman-Fried, when Bloomberg was preparing a critical — and, it seems, prescient — article about the ties between Alameda and FTX , Bankman-Fried considered shutting Alameda down. Both Bankman-Fried and Ellison lied to the reporter to make the two companies sound more separate than they were. Also, to increase the appearance of separation, a venture fund was renamed to remove “Alameda,” even though that’s where the money was coming from.

In hand-written notes, Ellison outlined the problems with shuttering Alameda. Among them? Alameda’s job was “market making for shitty things” — which was how Ellison referred to creating liquidity for thinly-traded assets. Plus, Alameda was a backup liquidity provider for FTX.

“It was finally happening.”

Ultimately, they did nothing.

But Bankman-Fried was right to worry about reporters. On November 2nd, 2022, CoinDesk published an article presumably based on a version of Ellison’s doctored balance sheet . (I expect that if the reporter had seen insider loans, that might have been somewhere near the lede.) That kicked off a flurry of communication between Bankman-Fried and Ellison, which we saw because Ellison started preserving her messages. “I was terrified,” she said. “It was finally happening.”

Bankman-Fried thought the move was to make bold tweets, but he didn’t want to do it. Instead, Ellison did — writing in her own words a workshopped version of a tweet Bankman-Fried originally wrote, which began, “Heh, I see *someone* is really trying to FUD us.”

Of course, then Changpeng “CZ” Zhao jumped into the mix, saying he wanted to liquidate his remaining FTX token, FTT. After a discussion on Signal with Bankman-Fried, Ellison responded on November 6th that she would buy FTT at $22. An eventful few days ensued , which ended in Alameda’s and FTX’s bankruptcy.

We saw a remarkable text from Ellison as the collapse was happening. “This is the best mood I’ve been in a year tbh,” Ellison messaged Bankman-Fried. It’s not clear what date the screenshot came from, though Bankman-Fried was the source. Ellison cried looking at the messages. “To be clear,” she said, “that was overall the worst week of my life. I had a lot of mood swings that week, and a lot of different feelings.”

One of those feelings was relief. The truth coming out was “something that had been in my mind every day,” she said. The thing she’d been dreading had happened and “I didn’t have to lie any more.” She said she felt “indescribably bad” about all the people “who trusted us that we had betrayed.” A court clerk passed her a tissue.

Bankman-Fried was right. The things you put in writing can come back to bite you. Your awful ex-boyfriend might leak your diaries to The New York Times . In those notes — memos, really — Ellison discussed her concerns about her personal relationship with Bankman-Fried affecting their professional relationship. She felt like an unequal partner in their relationship. Today’s evidence suggested that was certainly true in their professional life.

It also suggested something else: the things you put in writing can, potentially, save you. It’s a lot harder to paint Ellison as the sole decision-maker when she’s got contemporaneous evidence that she didn’t make a move without running it by Bankman-Fried.

OpenAI releases GPT-4o, a faster model that’s free for all ChatGPT users

Verizon, at&t, and t-mobile’s ‘unlimited’ plans just got a $10m slap on the wrist, the dji pocket 3 is almost everything i wanted my iphone camera to be, the new ipad pro looks like a winner, chatgpt is getting a mac app.

More from this stream FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried is guilty of fraud

Sam bankman-fried won’t face a second trial., an update on the ftx bankruptcy plan, via an interview with an ftx creditor., the guy who designed sam bankman-fried’s defense says that sbf was “at the very top of the list as the worst person i’ve ever seen do a cross examination.”, what could possibly go wrong, again.

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My Portfolio

- Latest News

- Stock Market

- Premium News

- Biden Economy

- EV Deep Dive

- Stocks: Most Actives

- Stocks: Gainers

- Stocks: Losers

- Trending Tickers

- World Indices

- US Treasury Bonds

- Top Mutual Funds

- Highest Open Interest

- Highest Implied Volatility

- Stock Comparison

- Advanced Charts

- Currency Converter

- Basic Materials

- Communication Services

- Consumer Cyclical

- Consumer Defensive

- Financial Services

- Industrials

- Real Estate

- Mutual Funds

- Credit cards

- Balance Transfer Cards

- Cash-back Cards

- Rewards Cards

- Travel Cards

- Personal Loans

- Student Loans

- Car Insurance

- Morning Brief

- Market Domination

- Market Domination Overtime

- Opening Bid

- Stocks in Translation

- Lead This Way

- Good Buy or Goodbye?

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

Yahoo Finance

Portrait of a 29-year-old billionaire: can sam bankman-fried make his risky crypto business work.

“I hope to never be as wrong as I was in that conversation,” says Adam Yedidia. He is reflecting on a chat he had with Sam Bankman-Fried , his close friend and former MIT classmate, in fall 2017.

Bankman-Fried was then inviting Yedidia to join him in launching a trading firm in Berkeley, Calif., that would specialize in buying and selling cryptocurrencies—digital assets like bitcoin ( BTC-USD ), ether ( ETH-USD ), and litecoin ( LTC-USD ). Yedidia declined, and even tried to talk Bankman-Fried out of the whole idea.

“I was sort of like, this crypto thing seems pretty scammy,” Yedidia recalls. “I was convinced it was a bubble.”

Bankman-Fried, now 29, went forward anyway. Four years later, he is a billionaire 16 times over, according to a recent Forbes estimate. Though such estimates are fuzzy—many of Bankman-Fried’s digital assets are illiquid, of speculative value, and just plain weird—his sudden prosperity appears to constitute one of the fastest accumulations of self-made wealth in history.

His riches stem from both the trading firm Yedidia took a pass on, Alameda Research , and from a Hong Kong-based cryptocurrency futures exchange, FTX, which Bankman-Fried started up in mid 2019. (Yedidia finally joined Bankman-Fried at FTX this past January.)

Last month, FTX—of which Bankman-Fried owns nearly 60%—completed an industry-record $900 million fundraising at an $18 billion valuation . That valuation was 18 times higher than it had been 17 months earlier, at FTX’s first-round fundraising in February 2020.

Bankman-Fried also still owns 90% of Alameda Research, he says. Alameda’s digital wallet at FTX (which is not its only store of assets) contained over $10 billion in digital coins in mid-July, according to a screengrab he sent me. (More than $5 billion of that was “locked,” however—not yet eligible for conversion to conventional money—and another $4 billion was in FTT, a digital coin issued by FTX.)

Over the past three months, FTX has unveiled high-profile marketing contracts with Major League Baseball , celebrity couple Tom Brady and Gisele Bündchen , and the NBA’s Miami Heat, which is renaming its home venue FTX Arena . Last election cycle, Bankman-Fried contributed more to President Joe Biden’s campaign than anyone except Michael Bloomberg: about $5.2 million, according to Federal Election Commission records.

Still, the book isn’t closed on whether Yedidia’s original instincts were foolish or not. Despite Bankman-Fried’s increasingly mainstream acceptance and considerable personal charisma—he’s become a frequent guest on cable business shows and also appeared on Yahoo Finance—what he’s doing is dicey.

Two approaches to cryptocurrency exchanges

Basically, we’ve seen two approaches to cryptocurrency exchanges so far. One category of operation—companies like Coinbase Global ( COIN ), which went public in April , and Gemini, founded by Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss in 2014—have set up U.S.-based operations that attempt to comply scrupulously with U.S. regulatory frameworks, even though those are cumbersome and ill-suited to the nascent asset-class. As a result, these companies offer a relatively limited set of offerings—mainly spot-market sales of a select list of cryptocurrencies. (In June 2020, FTX launched a U.S. subsidiary, FTX.US —with offices in Berkeley, Chicago, and Miami—which also takes that conservative approach.)

But a set of much more lucrative companies—like BitMEX, Binance, Bitfinex, and FTX’s international exchange—have taken a much riskier approach. They have set up offshore, and have offered a wide array of innovative products, including crypto futures, swaps, other derivatives, and “tokenized stock” (digital assets said to be tethered to actual stock holdings held by a custodian somewhere, like, in FTX’s case, a German bank). The offshore exchanges have also let traders—including unsophisticated retail traders—buy many of these volatile instruments on margin. Until last month, for instance, several exchanges, including FTX, spotted their customers margin ratios as high as 100:1; that is, you could buy a $100,000 position in a crypto derivative with just a $1,000 deposit. One big price swing—hardly unusual in crypto markets—can result in automated margin calls that wipe out a trader’s position. (Last month, a few days after The New York Time s published a story questioning the suitability of such products for retail traders , FTX and Binance each reined in their ratios to 20:1. Though comparisons are not apples-to-apples, the regulated CME Group—the Chicago Mercantile Exchange—requires 35% collateral for trades in its bitcoin futures product.)

In hopes of evading U.S. regulators, the offshore exchanges, including FTX, all say they refuse orders from U.S. customers. But such “geofencing” is notoriously hard to do in a world with virtual personal networks (VPNs) and other workarounds, and there’s evidence that at least some exchanges haven’t always tried very hard. Manhattan federal prosecutors indicted the founders of BitMEX last October alleging violations of U.S. anti-money laundering laws, while the U.S. Commodities Futures Trade Commission sued those founders for failing to register under the U.S. Commodities Exchange Act. (The defendants have denied wrongdoing.) Binance, the largest cryptocurrency exchange today—and one that no longer reveals where it is based—is reportedly under scrutiny by the U.S. Department of Justice, Internal Revenue Service , and the Commodities Futures Trading Commission . It’s also under investigation by regulators in Japan, the U.K., Germany, Italy, and others, and Thailand’s Securities and Exchange Commission brought criminal charges against it last month . (Binance CEO Changpeng Zhao has denied wrongdoing by his company.)

“There’s just inherent risk associated with this business model,” says Lee Reiners, the executive director of the Duke University School of Law’s Global Financial Markets Center. “Major, major regulatory risk,” he continues.

“There have been a few like FTX over the years,” says one player in the U.S. crypto community who is bullish on bitcoin, yet takes a dim view of the offshore exchanges. “U.S. regulators caught up with every one of them,” says this person, who requested anonymity. “FTX is relatively new, and the wheels of justice grind slowly.”

‘I wish we were perfect, but no one is’

So which is it? Is Bankman-Fried more scrupulous than his competitors? Or have the regulators just not yet gotten around to nabbing him?

“We’ve put a lot of attention and care into regulation and interfacing with regulators,” Bankman-Fried responds. (He appears to tread carefully here, so as not to draw explicit contrasts between FTX and the other exchanges. He counts Binance’s Zhao as a friend, and Binance was an investor in FTX until just last month.)

“I wish we were perfect, but no one is,” he continues. “If there’s anything we’re doing that a regulator doesn’t want, you don’t have to sue us. Just reach out and tell us what you want.” He also stresses that FTX has “had KYC since day one,”—i.e., Know Your Customer rules, designed to prevent money-laundering or terror-financing. He believes those address the regulators’ most urgent concerns.

“Their goal isn’t to go to war with industry, by and large,” he says of regulators worldwide. “They have things they want to enforce or prevent, and they want to also help industry grow. . . . They want to find a way to balance these and I think the big thing is finding a way to meet them there.”

This article aims to shed light on whether Bankman-Fried can achieve his audacious goal: persuading the world’s regulators to fashion new rules to accommodate his fait accompli exchange. It is the most in-depth profile so far of Bankman-Fried, perhaps the most pioneering young entrepreneur of our time. It draws chiefly on interviews with eight people, including more than five hours of conversations with four who know him extremely well, plus more than four-and-a-half hours of Zoom interviews with Bankman-Fried himself.

Bankman-Fried is marked by striking contradictions. On the one hand, he is a classically driven businessman who sleeps four-hour nights, famously catnapping in a beanbag chair at the office so subordinates can wake him at any hour for guidance. (Crypto trading is 24/7—and must be, given the wild, precipitous price swings. Bitcoin, for instance, was trading at nearly $64,000 in March; around $29,000 in July; and close to $46,000 this week.)

Yet Bankman-Fried is also disarmingly reflective, candid, and almost academic in his apparent effort to give dispassionate and truthful answers.

He is also an autodidact moral philosopher—a self-described “Benthamite,” “ effective altruist ,” and vegan—who is, nevertheless, devoting his career to a sector that many associate with crime, ransomware, and environmental irresponsibility.

Also—strikingly unusual for someone steeped in the crypto world—he is notably non-boosterish about it. (“I don't want to wave away all of these problems, because they're not all irrelevant,” he says of the attacks on crypto, before commencing a professorial overview of its dangers and potential benefits.)

A key Bankman-Fried character trait is that, while he’s not a daredevil, neither is he risk averse. Perhaps this stems from the fact that he’s “super-quantitative,” as FTX’s lead engineer, Nishad Singh, puts it. “Whenever we’ve had big decisions to make or been in scary times, Sam takes to his spreadsheets.”

In any event, if the mathematical upside is high enough, he appears willing to accept harrowing downside-risk in ways that more emotional types would not. Aside from the potential exposure he faces from U.S. regulators, Bankman-Fried also has to worry about whether mainland China will eventually subject Hong Kong to its own sharply anti-crypto policies. China recently banned “bitcoin-mining” in China—the energy-draining, computational process by which new bitcoin are minted—and for years it has officially outlawed cryptocurrency exchanges on its soil (though it has also tolerated puzzling exceptions).

Does he ever worry about a mainland Chinese crypto crackdown in Hong Kong—and even winding up under house arrest, the way some mainland Chinese crypto executives reportedly have? He deflects the question, offering only, “We’re doing what we can to be respectful of local regulations.”

But he does stress that FTX—which now has about 100 employees—is mobile, and can pick up its bags if need be.

“Given the emerging nature of the industry,” he says, “it’s not yet clear where the best places to be will be. We are talking with a lot of jurisdictions right now about building out regulatory frameworks. . . . We’re opening up a bunch of offices right now and we may have a new, very substantial one in the next year or so.”

For his part, Yedidia trusts Sam’s instincts. “He’s been right about not only finance things, but about personal things in my life,” he says—alluding to “girlfriends and stuff.”

Yedidia continues: “I don’t know exactly what the right word is, but part of me wants to use the word wisdom .”

That’s a big word to apply to a 29-year-old who makes a living offshore doing things that would be illegal at home. FTX could yet prove to be the Napster of commodities futures trading. But for the time being, shrewd is certainly a plausible word for someone who appears to have threaded a needle no other American could—while amassing a net worth of $16 billion.

A family of ‘take-no-prisoners utilitarians’

Sam Bankman-Fried was born March 6, 1992, on the Stanford University campus. Both his parents were—and are—law professors there. Barbara Fried writes about the intersection of law, economics, and philosophy, while Joseph Bankman mainly teaches tax policy. (In conversations, Bankman-Fried will sometimes use the word quaere —the imperative of the Latin verb quaerere , meaning to inquire. It’s a term commonly used by law professors that means, essentially, “Ask yourself ....”)

Singh, a friend of Bankman-Fried's younger brother who knew his family well when both were growing up, describes Barbara Fried as a “consequentialist.” That’s an “umbrella” term, Singh explains, for a set of philosophies of which “utilitarianism is one specific instantiation.”

It’s an odd way to describe a high-school friend’s mother, but the fact that Singh does so gives a feel for how these branches of moral philosophy permeated Bankman-Fried’s home growing up.

In an interview, Barbara Fried says that while she herself has only been “inching toward” utilitarianism over her career, her husband and both of her sons have long been “take-no-prisoners utilitarians.”

“The ethical goal of utilitarians,” she explains in a followup email, “is to maximize the total well-being of the world’s people (and for some, animals as well). . . . That goal leads utilitarians to focus their efforts on helping people in the direst straits . . . and on policy interventions that will lower the risk of existential threats to present and future generations.”

When Bankman-Fried was about 14, his mother says, she noticed that—completely on his own—he had been reading up in this area intensively.

“He emerged from his bedroom one night and said to me, ‘Mom, what kind of person labels an argument he disagrees with ‘the repugnant conclusion?’” Bankman-Fried had stumbled upon the writings of philosopher Derek Parfit, who had used that phrase in criticizing a certain strain of utilitarian thought.

“Sam was mad at Parfit for being wrong,” Barbara Fried recounts, “but madder at Parfit for the cheapness of his argument. ‘If you’re gonna take this on, you damn well need to grapple with the argument’” and not merely label it “repugnant.”

Despite his intellectual gifts—or, rather, because of them—Bankman-Fried hated school.

“It was super-structured,” he recounts in an interview, “I have a lot of pedagogical disagreements with how a school is run. . . . On the social side, I think I always felt more comfortable around older people.”

Though Bankman-Fried wasn’t a complainer, his mother says, she noticed a severe problem when he was in seventh or eighth grade. One day, she recalls, she came across him crying. “And he said to me, ‘Mom, I’m so bored I’m gonna die.’”

She and her husband then arranged to get their son some advanced math classes, and later sent him to the Canada/USA Mathcamp over summers. There he was introduced to “puzzle hunts”—versions of scavenger hunts that require solving a series of logical riddles, which are stepping stones to solving a larger meta-riddle. When he returned to high school after the summer, he organized and largely wrote a puzzle hunt in which teams from local schools could compete.

“I saw a different side of him than I had ever seen,” Barbara Fried recounts. He had “amazing managerial skills” and “could muster visible, exuberant, infectious enthusiasm for it.”

That said, high school remained a bad period for Bankman-Fried. “I was a little bit in waiting mode for the next chapter to begin,” is how he recalls it. “High school and middle school are not the things that I am really made for.”

In 2010, he went to MIT—he “basically flipped a coin” between it and Cal Tech, he says—where he chose to live at a coed group house known as Epsilon Theta, or ET.

“Think of a fraternity,” says Yedidia, who met Bankman-Fried at Epsilon Theta, “but replace all the alcohol with the nerdiest stuff you can imagine.” They would party late into the night, Yedidia continues, but that would entail playing elaborate board games or chess or “Starcraft” or “League of Legends” video games.

Bankman-Fried especially liked games that involved time pressure, according to Gary Wang, who arrived at Epsilon Theta in Sam’s sophomore year. “Sam’s really into thinking fast,” says Wang, who first met Sam at the summer math camp during high school. “In chess or other games, he would insist on playing with a timer.” (Today, Wang is FTX’s chief technology officer.)

Although Bankman-Fried was brilliant, Yedidia says, Yedidia didn’t count him as the smartest person at Epsilon Theta. (Wang might have held that distinction, Yedidia muses.) “But people were drawn to [Bankman-Fried],” Yedidia says. He was “charismatic” in a nontraditional way, and eventually became “commander” (president) of Epsilon Theta. Yedidia thinks it had to do with the fact that when Bankman-Fried spoke, it was obvious that “he really meant the stuff he said.”

Bankman-Fried majored in physics in college, with a minor in math. But he is witheringly dismissive of formal education, even at MIT. “Nothing I learned in college ended up being useful,” he says, “other than, like, social development. . . . On the academic side, though, it’s all f***ing useless. . . . School is just not helpful for most jobs. . . . Everyone knows it’s true. . . . Some people kind of don't really want to say it's true, but it just is.”

In the summer after his sophomore year, he began blogging. He mainly wrote essays on utilitarianism or statistically-based jeremiads about baseball or politics (the last category being “a sh***y version of FiveThirtyEight,” as he described it at the time).

In one of his first entries, he identified himself as “a total , act , hedonistic /one level (as opposed to high and low pleasure), classical (as opposed to negative) utilitarian,” while furnishing explanatory hyperlinks for the words “total,” “act,” “hedonistic” and “classical.”

For the lay reader, his baseball essays may be the most accessible. There he railed against the convention of grooming pitchers as “starters,” “relievers,” and “closers.” Instead, he argued, managers should always remove every pitcher after no more than two or three innings. This would, among other things, prevent batters from adjusting to “a pitcher’s stuff.” He offered empirical corroboration for some of his arguments, gleaned from a Python script he had written (dubbed “Basim”) that simulated baseball games based on the statistics of players in lineups.

Many of his essays were mordantly contrarian. In one, entitled “The Fetishization of the Old,” he decried the excessive praise (in his view) heaped upon Shakespeare, Stradivarius violins, “Citizen Kane,” aged wines, and the U.S. Constitution “as a guide to public policy.”

“Romeo and Juliet are incredibly flimsy characters,” he wrote, “and the plot is absurd. . . . [T]he number of lines between when Romeo is first made aware of Juliet's existence and when he recites his first love sonnet about her is 32, and none of those involve any action on Juliet's part, let alone interaction between them.”

‘Earning to give’

In his sophomore year, Bankman-Fried became exposed online to “effective altruism,” which he regards as a turning point in his life. That movement, founded by two Oxford philosophy professors, urges people to use their time and resources to bring about the greatest good to the greatest number they can. “EAs,” as effective altruists call each other, use empirical analysis to determine which charities are most efficient in terms of alleviating suffering in the world, and then try to advance those causes through either direct action or donation.

Around that time, he attended a talk by Will MacAskill, one of EA’s founders. Bankman-Fried’s reaction, as his mother recalls it, was along the lines of: “Yes, that's right. All of this is right. This is what I’ve been thinking about—and there's a name for it!”

Later that year, Bankman-Fried had lunch with MacAskill. “That was sort of the point,” Sam says, “at which I started to think in a more principled way about what I should do with my life.” Until then he had been assuming he’d probably become an academic. But now he began thinking that, among other drawbacks to that plan—like hating academic research—it would be hard, as an academic, “to have real positive impact on the world on a mass scale.” A more compelling pathway might be “earning to give”—an EA term for making a lot of money in some conventional, morally neutral occupation and then giving generously to a highly efficient, underfunded cause like, say, malaria relief. Basically, the notion was that, depending on one’s skill set, it may make more sense to become rich on Wall Street and donate $1 million to a Mother Teresa than to try to become a Mother Teresa. (I’m assuming, for these purposes, that one could have empirically established that Mother Teresa used donations efficiently and that she wasn’t already overfunded.)

Around that time, Bankman-Fried and his friend, Yedidia—who had also become an EA—both became vegetarians. That’s not an uncommon choice for those EAs who include animal suffering in the utilitarian calculus. (Later, both became vegans.)

“You spend half an hour eating a chicken,” Bankman-Fried explains, “and [the chicken] has to be put through a pretty miserable experience [at a factory farm] for a month in order to generate that, and it seemed like you had to make some pretty implausible assumptions about chickens for that to make sense.”

Bankman-Fried then devoted a number of blogposts to effective altruism themes. In late 2012, for instance, he performed an analysis of which charities were most effective. By his arithmetic, for instance, giving to the Berkeley Repertory Theater was hard to defend when the same dollars could be given to the Against Malaria Foundation. “For the cost of saving a life in a developing country,” he wrote, “you could subsidize about 30 tickets to a play.”

By his junior year, Bankman-Fried was torn between working for the Center for Effective Altruism itself or going to Wall Street to pursue the earning-to-give pathway. In talks with MacAskill and Ben Todd—the founder of “80,000 Hours,” an EA group that provides career counseling—he recalls sensing a gentle nudge toward the latter route.

That summer, he interned at Jane Street Capital, a Wall Street quant firm.

“I really liked it there,” he says. It’s the first time, in recounting his life story to me, that Bankman-Fried evinces unalloyed happiness. He returned to Jane Street full-time after graduation.

What did he do there exactly? “It’s being hard to answer that question is actually one of the defining properties of it,” he says. “You just try to do the right trades, whatever tool gets you there,” he says. “It straddled the lines of computer and human trading. There’s a lot of automation, but there’s a lot of manual oversight and intuition involved as well.”

Why did it appeal to him so much? Singh, now lead engineer at FTX, thinks that, in trading, Bankman-Fried had finally found an activity where he wasn’t bored. “Trading will soak up Sam’s full attention,” he says. “There’s sort of an unbounded number of things you could be thinking about productively while trading, especially at a busy moment.”

Often when Bankman-Fried has conversations, Singh continues, he’ll play a video game in the background—“even at the risk of disrespecting the other person”—because his mind just isn’t fully consumed.

(During the first of our interviews, I asked Bankman-Fried if he was doing that. “I thought about it,” he confessed. “But, completely honestly, I was sort of like just waiting to see how engaging the first few minutes were. Turned out the answer is: engaging enough that it was going to take up more of my brains than I had to spare after a video game.”)

Jane Street’s casual atmosphere appealed to him, too. Jane Street is a “proprietary firm,” Barbara Fried explains, meaning they trade on their own account rather than for clients. “Which means the quotient of bull**** is really, really low. Which was key for Sam. He could go to work in shorts and sandals all year round and nobody cared.”

Bankman-Fried worked there happily for three years. True to the earning-to-give strategy, he gave away more than half his earnings to charity during that period, he says.

In 2017, he took his first vacation in years, flying back to the Bay Area. “I forced myself to sit down and run some numbers about what I should do with my life,” he says. “Like, here’s seven things I could do, and what are the expected values of them? And it dawned on me that . . . there were just a bunch of things that seemed like maybe very high upside. . . . While Jane Street was competitive with all of them, I felt like it was unlikely to be competitive with whichever of them turned out to be the best.”

A risky venture with huge potential upside

One idea that still appealed to him was working directly for the Center for Effective Altruism. But another was setting up his own cryptocurrency trading firm.

He knew remarkably little about crypto at the time. He had never traded it at Jane Street, nor paid attention to it at MIT. (The principles behind bitcoin were first laid out in a nine-page white paper in 2008, and the first bitcoin was minted on a blockchain in 2009—the year before Bankman-Fried entered college.)

Among Bankman-Fried’s close friends, only his Epsilon Theta buddy, Gary Wang, knew anything about crypto. Wang had actually written himself a bitcoin arbitrage trading bot at MIT in 2014. He made a “couple thousand dollars” one semester—which “was nice for a college kid,” Wang says—but dropped it when he started interning at Google that summer.

Despite knowing little about crypto, as a trader Bankman-Fried recognized it had a potentially enormous upside.

“There was huge demand, huge volatility, huge inflows, huge price appreciation, huge amounts of attention and interest—and the infrastructure wasn't there,” he recalls. For an arbitrageur, the most obvious opportunities were the so-called “Kimchi premium” in Korea and a more modest premium in Japan. Relative to U.S. bitcoin exchange prices, bitcoin was trading about 30% higher in Korea and about 10% higher in Tokyo. Demand for the coins was tremendous in those countries, and the obstacles to international crypto trading—laws, regulations, fear—were hampering foreign-held bitcoin from being sold there.

“Theoretically,” he continues, “if you could get the right setup, you could make 10% doing that—in a day or something.” But he had no idea if the apparent opportunities were realizable in practice.

He began reaching out to friends and urging them to move to Berkeley and help him launch a crypto exchange there. Wang remembers Bankman-Fried telling him that the chances of success were only 20% to 25%, but the potential upside was huge. Even if they failed, Wang recalls him saying, there were a lot of effective altruists in Berkeley and maybe they could do something with that.

Wang began designing a prototype trading system for them. “At first,” says Bankman-Fried, “that meant building out [a manually operated platform] for us to be able to have one interface to trade on every exchange instead of having to go to each website. Later that meant . . . automated trading systems.”

In September 2017, Bankman-Fried quit Jane Street and Wang quit Google, and each moved to Berkeley.

In October, however, Bankman-Fried also took a position as director of development at the Center for Effective Altruism in Berkeley. Recognizing that his crypto idea might not pan out, he was pursuing both paths.

He wasn’t candid with the center, he admits. “I felt nervous about telling colleagues that I was unsure if I was going to be there for a long time,” he says. “It just creates a weird dynamic.”

The arrangement was untenable. “It was absurd of me to try to do both at once,” he admits. “I had to make a decision, with crypto trading just seeming like, every week, higher expected value than it did the week before.”

In November, he quit the center. That month he registered Alameda Research, which had already been trading for a month, as a Delaware LLC headquartered in Berkeley. (Spokespeople for the Center for Effective Altruism declined comment for this article.)

Because of currency restrictions on offshoring the Korean Won, Alameda Research focused on trying to profit from the Japanese bitcoin premium. In theory, the idea was simple. Buy bitcoin cheap in the U.S. Sell dear in Japan. Wire the proceeds back to the U.S. Rinse and repeat.

“Oh, great. Free money,” Bankman-Fried comments.

It was not simple. At the time, he soon discovered, most major U.S. banks wouldn’t deal with crypto exchanges. In any case, U.S. crypto exchanges, like Coinbase, had daily withdrawal limits, curbing an arbitrageur’s potential profits. In addition, you needed to be a Japanese resident to do certain transactions with Japanese cryptoexchanges or banks. Many Japanese bank tellers had never heard of arbitrage, and balked at facilitating repetitive transfers of Japanese Yen from crypto exchanges to U.S. banks, which raised every red flag in the book.

“At first, it seemed Sisyphean,” Bankman-Fried continues. But the hurdles proved finite in number, and, one by one, they were overcome. “All of a sudden, you could do it.”

They made about $20 million, he estimates, before the spreads suddenly dried up in early 2018. (He’s not sure why. Possibly other arbitrageurs also figured out how to make the trades. Alternatively—because bitcoin prices were then crashing worldwide—demand was drying up on both sides of the Pacific, bringing prices into alignment.)

For the next two years, Alameda Research did well. But Bankman-Fried and the other traders became frustrated with some of the offshore exchanges they were trading on. To understand the issues, it’s useful to think about—for contrast—how a regulated U.S. commodities futures exchange works. With the Chicago Mercantile Exchange or Chicago Board of Options Exchange, for instance, there are many layers of safeguards in place. If a trader defaults on a contractual commitment, an exchange “member”—the registered “futures commission merchant” through whom the trade was made—must make good on it, for instance.

No comparable safety nets existed on the offshore crypto exchanges. If a customer’s account became net negative, many exchanges would, in effect, recuperate the exchange’s losses from other customers —even though those other customers were fully collateralized and their positions were in the black. Alameda Research wrote white papers on how the exchanges could improve their practices to avoid these outcomes, but in vain.

In late 2018, Bankman-Fried went to a conference in Macau. While there, something happened that he calls “the most mismanaged event in crypto exchange history.” A digital asset called “bitcoin cash” was undergoing a technological fork and splitting into two different successor coins. This created a legitimate challenge for the exchanges in figuring out how to handle existing futures contracts on the original coin. Nevertheless, the solutions some exchanges hit upon were, in Bankman-Fried’s view, preposterous, and innocent customers collectively lost about $25 million.

“We’d obviously been frustrated for a while about how exchanges functioned,” he says, but this event made Bankman-Fried think that he and his team could do better.

While attending a series of previously scheduled meetings in Hong Kong, he got encouragement for his idea from a number of Asian crypto players. He summoned Wang, who flew the next day to Hong Kong. As for Bankman-Fried himself, he says, “I just canceled my return flight, rented out a WeWork, and basically never left.”

Wang and he began building an exchange platform with a range of improvements, particularly with respect to the risk engine and margin rules.

Back at Alameda, launching the new exchange was controversial, recounts Singh. Alameda was profitable, but “hugely understaffed,” he says. Now its best trader and best engineer, Bankman-Fried and Wang, were leaving for Hong Kong to immerse themselves in a risky new project.

“Our estimation was that it was only 20% likely to work out,” he says. “So in 80% of cases, we would have lost momentum and value in Alameda without other concrete gains.”

In hindsight, it was a phenomenal decision, Singh says. “But at the time it seemed extremely risky—and was contentious.”

Though it may sound like a stretch—lots of billionaires have boundless ambition—both Singh and Barbara Fried firmly believe that Bankman-Fried’s risk-tolerance stems from his effective altruism.

Barbara Fried puts it this way. “If you’re earning money for personal consumption, there is a very steep, declining marginal utility of income. After your fifth Porsche, do you really need a sixth? . . . But if you’re earning money to give it away to charity, there’s no diminishing marginal utility to money. The last life you save is worth as much as the first life you save.” (Aside from taking the occasional business-class flight, Bankman-Fried has little taste for living large, according to people who know him. In Hong Kong, he still lives with roommates, they note. )

Bankman-Fried registered FTX as an Antigua and Barbuda limited company in April 2019, and then launched from Hong Kong offices the following month.

FTX stood for “Fu-Tures eXchange,” he explains, shrugging. “I’m not great at naming things.”

‘Built by Traders, For Traders’

From the outset, FTX’s close relationship to Alameda Research was a selling point. Its Twitter account still proclaims: “Built By Traders, For Traders.”

FTX — The Official Cryptocurrency Exchange of the #LCS pic.twitter.com/kHsiv5iQQq — FTX - Built By Traders, For Traders (@FTX_Official) August 6, 2021

For the first year or so, Alameda played a crucial role at FTX. It was the main “liquidity provider,” accounting for “half the volume on the exchange,” Bankman-Fried acknowledges. (While there are definitional nuances, “liquidity-providers,” “market-makers,” and “arbitrageurs” all do pretty much the same thing most of the time, Bankman-Fried explains. In effect, they ensure that exchange customers can sell and buy when they want to, and they keep prices on various exchanges from getting out of line with one another.)

Though FTX’s dependence on Alameda was “not a healthy long-term setup,” it helped the fledgling exchange “bootstrap,” he says. That is, “it helped solve the problem of how’d you get users without volume, or volume without users. Since then, we’ve succeeded in onboarding a number of other liquidity providers, and now have a number of the world’s larger, multi-asset-class trading firms on it.” Alameda is no longer the biggest, he says.

Alameda’s role at FTX invites at least two followup questions, however. One is: If Alameda is based in Berkeley, how could it be dealing with FTX? I thought FTX didn’t accept trades from U.S. customers.

“Yeah, it’s an interesting question,” Bankman-Fried responds. “The answer is that [Alameda Research] is not a U.S. entity at this point. Its operations are not generally in the U.S.”

When did it switch?

“A couple years ago. Before FTX was founded.”

Does it still have offices in Berkeley?

“It doesn’t have a substantial office there.”

Where is it based now?

“So part of the answer is that it’s a bit distributed. Especially during COVID, it’s been the case that people will get stranded in various places for months to a year. . . . But it's been predominantly Asia-based for the last few years.”

Where is its charter?

Indeed, around the time FTX launched in 2019, a British Virgin Islands entity was formed called Alameda Research LTD. But the Delaware entity, Alameda Research LLC is still in “good standing,” according to Delaware authorities. So is a newly formed entity called Alameda Research Holdings Inc., which was just incorporated in Delaware two months ago. How are they all related?

In response to an email seeking clarification, he writes, without further elaboration, “BVI is a subsidiary of LLC.”

What about all the other large asset managers who now provide liquidity to FTX? Who are they and where are they based?

“So obviously, I don’t want to give away specific client information,” he says in an interview, “but in general when you look at the largest trading firms in the world . . . most of them have non-U.S. teams. This is something most of them have been building out for the last twenty-ish years. Not specifically for crypto.”

The other obvious followup question about the Alameda’s relationship with FTX relates to potential conflicts of interest. Theoretically, such a close connection between a trading firm and an exchange—albeit a very transparent one in this case—could create opportunities for abuses, like front-running.

“I have a hard time believing the S.E.C. or C.F.T.C. would permit that sort of [relationship between a trading firm and an exchange],” says Reiners, of Duke’s Global Financial Markets Center, “and to my knowledge it’s not happening” on any U.S. exchange now.

“Alameda has the same market access as any other entity trading on FTX,” Bankman-Fried responds, when asked about potential conflicts. “It doesn't have special access to data, and goes through the API like others do.”

A platform built on treacherous ground

FTX and Alameda Research have each continued to thrive. Daily trading volume on FTX is now in the $13 billion range. Alameda Research, which has about 20 employees, was making as much as $1 million a day for much of the past year, Bankman-Fried says, on just one of its trading strategies—a weird thing called “yield farming” relating to decentralized finance (DeFi) protocols. (That’s a story in itself.)

Bankman-Fried’s lifetime donations to effective charities now total about $35 million, as Fortune reported last month. In February, FTX also formed a foundation that has earmarked more than $11 million for charities like Oxygen for India, Lighthouse Foundation, and GiveDirectly, a poverty relief organization. FTX employees, many of whom are EAs, have given roughly $10 million more, Bankman-Fried estimates.

What’s hard to tell is whether Bankman-Fried’s growing wealth and stature will give him greater credibility and bargaining power with regulators or just paint a more vivid target on his back.

As the Wall Street Journal reported last month , a recent study by a data group called Inca Digital—combing through Twitter posts backed up by screengrabs—found at least 372 instances in which Americans appeared to be trading on offshore crypto exchanges. In 240 of those cases, they appeared to be trading on FTX. Bankman-Fried told the Journal that some of that number appeared to be mistakes on Inca’s part, but that, in any case, the entire number would account for only 0.01% of FTX’s trading volume. FTX also immediately contracted with Inca to help FTX weed out American traders in the future, the paper reported.

Still, the incident underscores the treacherous ground on which Bankman-Fried is building his platform. Some regulators obviously have grave concerns about offshore exchanges, while influential voices still decry the entire sector. SEC chair Gary Gensler and the U.K.’s top regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority, have each recently rattled regulatory sabers vis-à-vis offshore exchanges, while Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Krugman wrote a withering New York Times column in May called “Technobabble, Libertarian Derp, and Bitcoin.” There he noted that 12 years after their invention—“an eon in information technology time”—cryptocurrencies still play little role in “normal economic activity” and “almost the only time we hear about them being used as a means of payment — as opposed to speculative trading — is in association with illegal activity.”

Bankman-Fried, however, believes that both crypto in general and his exchange in particular are at least morally defensible propositions (aside from fueling his earning-to-give engine).

“You hear very different things [about crypto] depending on which country you’re in,” he says. “You go to half the countries in the world and you would not feel good having their fiat currency in a bank account there”—referring to their official legal tender. “Both from a hyperinflation perspective and . . . from a bank-seizing-your-money perspective. And [I don’t mean] seizing it because of money-laundering concerns, but [seizing it] because they'd prefer to have that money than for you to have it.”

What about Krugman’s critique? “Krugman is right that, right now, most legit payments don't use crypto. But I think they could and, in many cases, it would be better if they did . There's a self-fulfilling prophecy about saying nothing legit uses crypto, and using that as a way to discourage legitimate services from using crypto. . . . The current financial infrastructure is just not built to be natively digital. But I do think there’s a ton of promise.”

Ransomware? “I do think this is a thing worth . . . trying to combat,” he says. But so-called “privacy coins”—arcane assets like Z-Cash or Monero, whose blockchains are fully anonymous—are the real problems, he thinks. “There should possibly be serious regulation around some of those,” he acknowledges. But “other [digital] coins are in many ways easier to trace than other forms of extortion,” he asserts, because “the public ledger helps.” He cites, as an example, the FBI’s successful recovery of much of the Colonial Pipeline bitcoin ransom as corroboration of his point.

Environmental concerns? “Right now, only bitcoin and ether, of major coins, have large energy usage. As ether switches to [an upgraded blockchain] . . . most cryptocurrencies will not have large energy or climate impacts.”

Don’t most unsophisticated traders get burned trading in volatile crypto markets? “I don’t believe it’s historically been true,” he says, though he cautions that “this is not a forward-looking statement” and “I’m not giving investment advice.”

“ Quaere how much of that’s luck versus other things,” he continues, trying to be fair to his critics. “But the people who have been exposed to crypto . . . tend to be pretty happy with their experiences there,” he says. “I think it’s a little bit different than when you look at people who have been exposed to casinos.”

“A lot of the quote unquote trading strategies,” he continues, “are basically like, ‘I think cryptocurrency has a lot to offer the world, so I'm gonna buy some cryptocurrencies. And I think one could make a decent argument that they were basically right for the right reasons, and made money because of that.

“The last thing to note,” he adds, “is that for any asset to mature, there have to be efficient markets for it. [There needs to be] a pathway to liquidity, price discovery, stability, and maturity for the asset class,” all of which FTX is providing.

Will regulators and legislators around the world ultimately be persuaded by such arguments? Nobody knows. Bankman-Fried is betting his livelihood—perhaps even his freedom—on that known unknown.

He is a billionaire, at least in part, because he has more risk tolerance than most of us, and has not been cowed by ferocious condemnations of the sector by powerful and highly credentialed people.

Which is totally in character. As Barbara Fried says of her son: “His position has always been: ‘I will go where the premises of utilitarianism take me. I’m not going to flinch. And I’m not going to name the outcomes ‘repugnant.’ I’m going to think about them, and my judgment is going to be rational.’”

Unlike Bankman-Fried, I’m not a betting man. If I were, though, I’d bet that some of Bankman-Fried’s rational judgments will eventually come into conflict with those of regulators. At the same time, I’d bet that in the long run, U.S. law—which avoids strangling new technologies and new business models in the cradle—will do more accommodating to Bankman-Fried than vice versa.

In addition, success has a way of legitimizing itself in our country. Quaere: how many Congressmen will dare run afoul of Major League Baseball, the NBA, Gisele Bündchen, and Tom Brady?

Correction: An earlier version of this article said FTX.US , FTX's U.S. subsidiary, was launched earlier this year. In fact, it was launched in June 2020. Yahoo Finance regrets the error.

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter , Facebook , Instagram , Flipboard , LinkedIn , YouTube , and reddit

Roger Parloff is a regular contributor to Yahoo Finance and has also been published in Yahoo News, The New York Times, ProPublica, New York Magazine, and NewYorker.com, among others. He was formerly an editor-at-large at Fortune Magazine.

More from Roger:

Dominion v. MyPillow Guy poses a stark test for America's libel laws

Dominion Voting official, in hiding, speaks out: 'This never ends for me'

The wild ride that made Rudy Giuliani, 'Kraken' lawyer Sidney Powell, and Fox News targets in the mother of all defamation cases

Nikola’s Trevor Milton left a trail of bitterness on his way to founding the electric car startup

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- FT App on Android & iOS

- FirstFT: the day's biggest stories

- 20+ curated newsletters

- Follow topics & set alerts with myFT

- FT Videos & Podcasts

- 20 monthly gift articles to share

- Lex: FT's flagship investment column

- 15+ Premium newsletters by leading experts

- FT Digital Edition: our digitised print edition

- Weekday Print Edition

- Videos & Podcasts

- Premium newsletters

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Everything in Premium Digital

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- 10 monthly gift articles to share

- Everything in Print

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

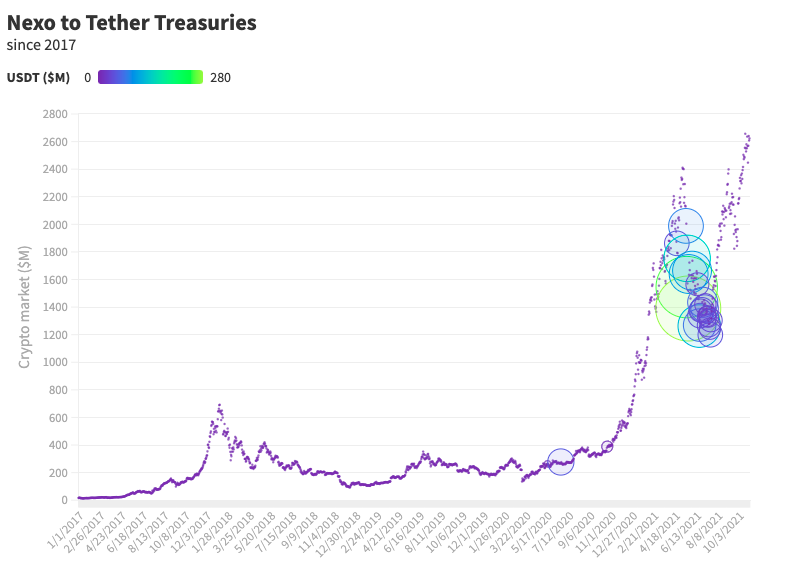

Tether Papers: This is exactly who acquired 70% of all USDT ever issued

If cryptocurrency was an engine, Tether (USDT) is one of its pistons.

Over the past seven years, the maverick stablecoin has evolved into a primary crutch for the ecosystem. It’s a tool for onboarding new money, managing and growing liquidity, pricing digital assets, and generally oiling crypto markets to keep them smooth.

Tether boasted a $1 billion market capitalization when Bitcoin hit $20,000 at the end of 2017. This year, it’s a $70 billion-plus powerhouse.

Practically every crypto exchange supports USDT trade in some form. The makeup of Tether’s reserves and its inner workings are yet to be disclosed in clear detail.

Still, the question of who exactly buys Tether directly from its parent company Bitfinex has remained unanswered since its inception way back in 2014.

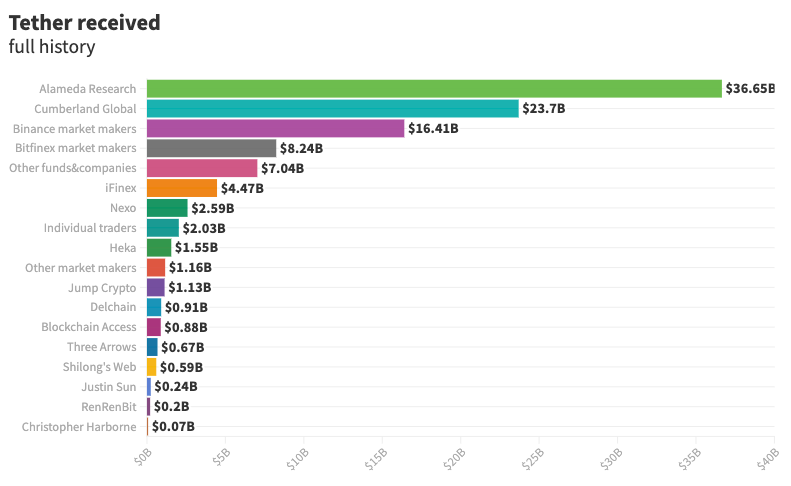

Earlier this year, Protos shed light on that mystery by reporting that just two companies, Alameda Research and Cumberland Global, were responsible for seeping roughly two-thirds of all Tether into the crypto ecosystem.

Today, we reveal a lot more.

We’ve spent months cataloguing and investigating every single USDT ever sent to and from Tether, across the eight blockchains and layers on which it currently exists: Omni (Bitcoin), Liquid (Bitcoin), Ethereum, Tron, Simple Ledger Protocol (Bitcoin Cash), EOS, Solana, and Algorand.

Here’s what we found.

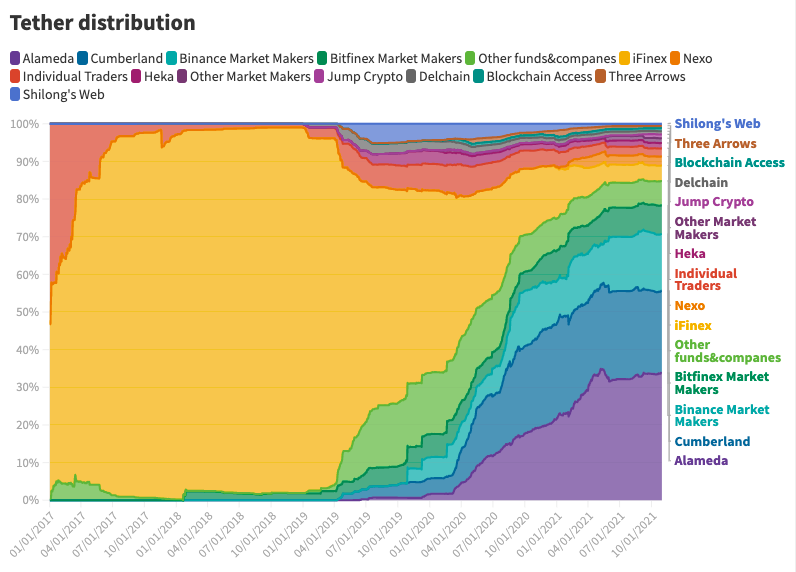

Birds-eye view of Tether

Protos pulled blockchain data from all disclosed Tether Treasuries and Printers across the various layers, stretching back to 2014 until October 31, 2021.

We then filtered out transactions between Printers and Treasuries, as our analysis is primarily concerned with USDT sent to and received from third parties.

After accounting for disclosed chain swaps (the process of transferring already-issued USDT between protocols), blockchain data shows Tether:

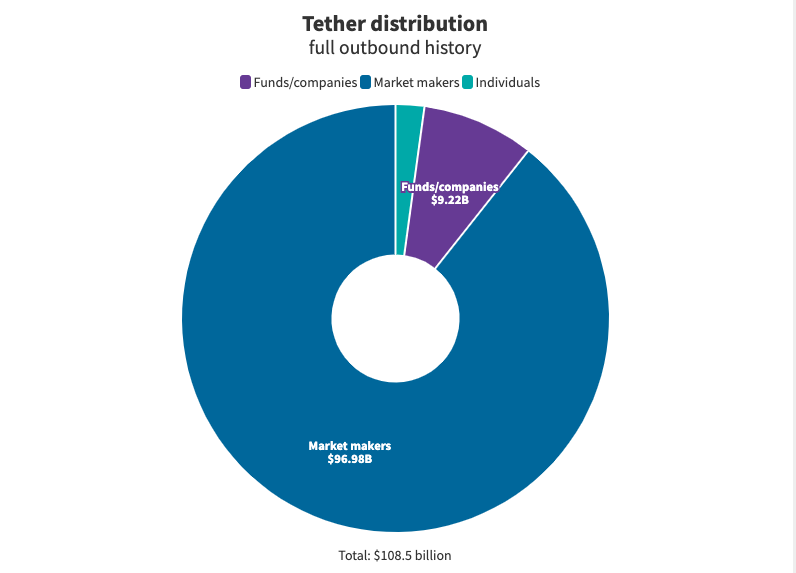

- distributed $108.5 billion in USDT,

- received $32.7 billion in USDT in that same period,

- sent a staggering majority of USDT directly to market makers and liquidity providers.

It must be noted that the figures cited in this analysis won’t always map one-to-one with Tether’s circulating supply.

Remember, we’ve tracked Tether Treasuries’ outflows and inflows; those volumes will not reflect Tether’s market value exactly (implying that Tether understandably recycles some USDT sent back to its Treasuries).

To make it clear: we’ve analyzed USDT flowing out of Tether Treasuries and linked blockchain addresses to specific entities.

Some of these entities maintain crypto exchanges; the data presented here relates specifically to their operational addresses as companies and not their exchange wallets, be they hot or cold.

Market makers, for our purposes, are simply defined as entities that have received multiple individual transactions from Tether Treasuries of $100 million USDT or more.

The term “market maker” traditionally refers to entities able to profit on the spread of assets (the difference in price between buy and sell orders).

Since it’s unclear which entities in the crypto ecosystem are strictly market making and which also utilize high frequency trading, proprietary trading desks, or operate venture capital funds, this is our attempt to delineate between them (albeit with a broad definition).

Within the context of Tether, market makers eke out gains by supplying crypto exchanges like Binance , Huobi, and FTX with liquidity for their various USDT trading pairs.

- Tether supplied categorized “market makers” with 89.2% of all USDT ($97 billion) it sent.

- Trading funds and other miscellaneous companies received $9.2 billion (8.5%).

- Smaller transactions deemed to have been received by “individuals” amounted to $2.35 billion (2.3%).

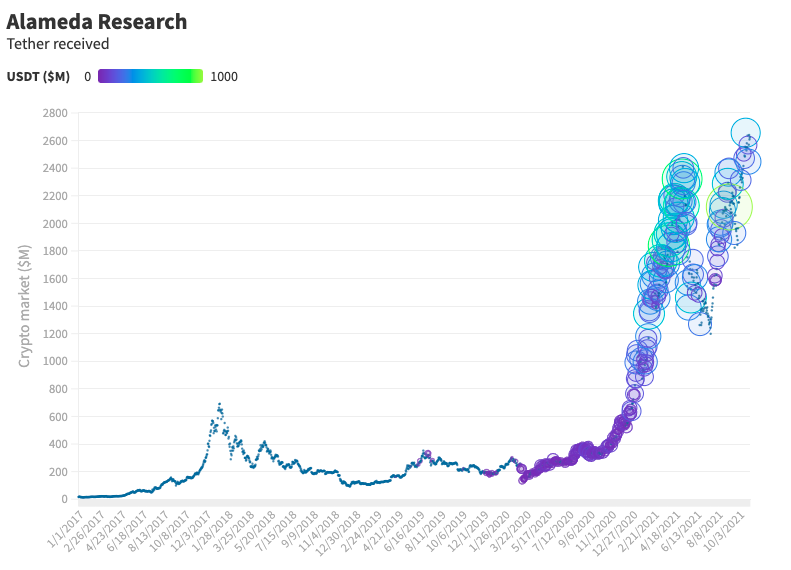

As Protos reported in August, market makers Alameda Research (spearheaded by crypto billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried) and Cumberland Global (a subsidiary of trading giant DRW) are still the biggest fish in Tether markets.

Together, Alameda and Cumberland received at least $60.3 billion in USDT across the time period analyzed, equal to around 55% of all outbound volume — ever.

$49.2 billion (71%) of Alameda and Cumberland’s USDT was acquired in the past year alone, equal to about 60% of all Tether issued in that time.

Market makers (Tether’s biggest customers)

Alameda research.

Alameda Research describes itself as a “multistage crypto and fintech investment firm,” and it made 29-year-old chief exec Bankman-Fried crypto’s richest billionaire (Forbes estimates his wealth at $26.5 billion).

Bankman-Fried founded Alameda Research in 2017 after leaving quant shop Jane Street. He opted to brand the fund a “research” unit to avoid banking problems as it started arbitrage Bitcoin trade in Japan.

The firm has historically been headquartered in Hong Kong, but recently announced plans to ship over to another tax haven, Nassau.

Read more: [ Cashed-up crypto exchange FTX heads to Bahamas — closer to Tether ]

Alameda Research wears multiple hats. It’s the parent company of crypto and crypto derivatives exchange FTX, but it’s also a quantitative trader, and serves as a venture capitalist across the ecosystem.

The firm has led an impressive 18 funding rounds and participated in 71 more, according to Crunchbase .

One of Alameda’s most notable moves was its participation in ‘Ethereum killer’ Solana’s $314 million token sale earlier this year, alongside Polychain Capital and CoinShares.

Alameda Research’s lead brain Bankman-Fried is one of Solana’s most vocal proponents. Solana’s native token SOL has since grown to become the fifth most-valued cryptocurrency at press time, just behind Tether.

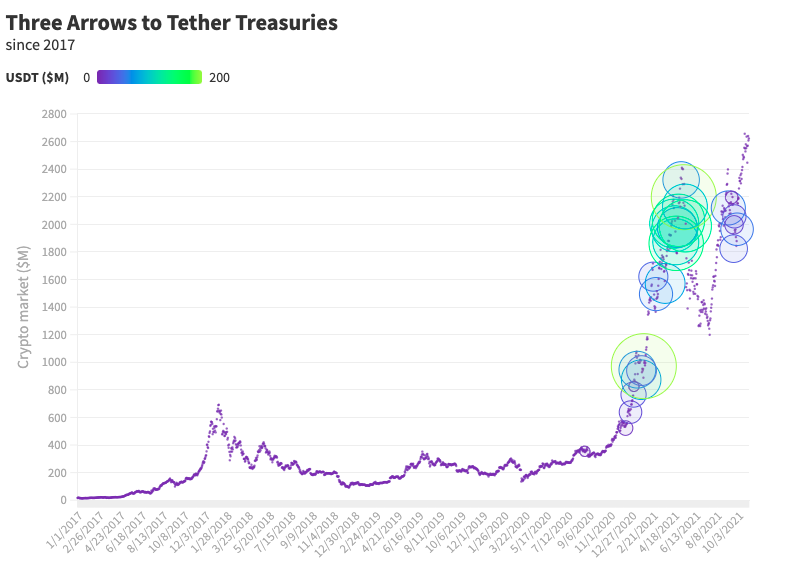

- Tether sent almost $36.7 billion in USDT to Alameda Research.

- $31.7 billion (86%) was received in the past year.

- Alameda Research accounted for 37% of all outbound volume.

While Tether sent nearly $30.1 billion (87%) of Alameda’s USDT directly to FTX, blockchain data shows Alameda operating on a number of other crypto exchanges.

Alameda also received:

- $2.1 billion (6%) on Binance,

- $1.7 billion (5%) on Huobi,

- $115 million (less than 1%) to OKEx.

The rest of Alameda’s Tether ($705 million, 2%) was sent to non-exchange addresses.

Cumberland Global

Cumberland Global is the crypto-trading subsidiary of markets powerhouse DRW, founded in 1992 by chief exec Donald R. Wilson.

As we reported in August, DRW is one of finance’s top dogs, particularly in futures markets (the Financial Times previously said the unit is “an important source” of futures trading volume across the globe).

Cumberland was first launched in 2014, during DRW’s gruelling five-year battle with the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) over alleged market manipulation — which it won in 2018.

Cumberland says it onboards wealthy individuals and financial institutions to the crypto ecosystem.

One of those clients is VanEck. The US Securities and Exchange Commission visited DRW in 2019 to discuss the listing of VanEck’s SolidX Bitcoin Trust on Cboe.

VanEck’s Trust was eventually offered to institutional investors via over-the-counter desks like the ones DRW operates.

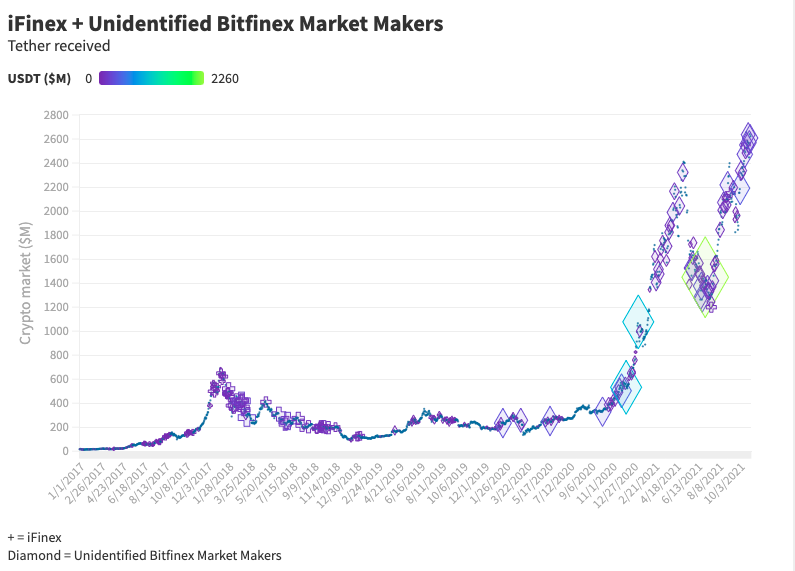

- Tether sent $23.7 billion in USDT to Cumberland.

- $17.6 billion (74%) was received in the past year.

- Cumberland received 22% of all outbound volume.

It has long been suspected, but Protos can confirm that Cumberland is one of Binance’s primary liquidity providers and market makers, and has been on the exchange since around early 2019.

Tether issued Cumberland $18.7 billion in USDT (79%) directly to Binance, and a much smaller amount to other exchanges:

- $131.5 million (less than 1%) on Poloniex.

- $9 million (less than 1%) on Bitfinex.

- $30 million (less than 1%) on both Huobi and OKEx.

The rest of Cumberland’s Tether ($4.9 billion, 21%) was sent to non-exchange addresses.