Volume 18, issue 1, December 2020

100 articles in this issue

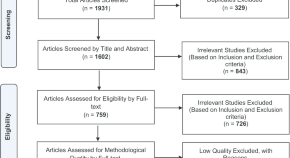

The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-regression

Authors (first, second and last of 9).

- Nader Salari

- Habibolah Khazaie

- Soudabeh Eskandari

- Content type: Research

- Open Access

- Published: 17 December 2020

- Article: 100

Turnover among Australian general practitioners: a longitudinal gender analysis

Authors (first, second and last of 5).

- E. Anne Bardoel

- Grant Russell

- Margaret Kay

- Published: 09 December 2020

- Article: 99

- Research to support evidence-informed decisions on optimizing gender equity in health workforce policy and planning ,

- Research to support evidence-informed decisions on optimizing gender equity in health workforce policy and planning

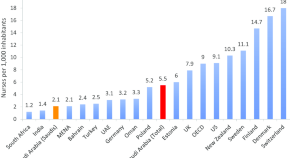

Challenges and policy opportunities in nursing in Saudi Arabia

Authors (first, second and last of 11).

- Mohammed Alluhidan

- Nabiha Tashkandi

- Mohammed G. Alghamdi

- Content type: Case study

- Published: 04 December 2020

- Article: 98

Task-shifting directly observed treatment and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis injection administration to lay health workers: stakeholder perceptions in rural Eswatini

Authors (first, second and last of 4).

- Ernest Peresu

- J. Christo Heunis

- Diana De Graeve

- Published: 03 December 2020

- Article: 97

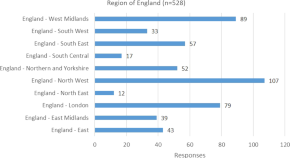

Workforce experience of the implementation of an advanced clinical practice framework in England: a mixed methods evaluation

- Jessica Lawler

- Katrina Maclaine

- Alison Leary

- Article: 96

More public health service providers are experiencing job burnout than clinical care providers in primary care facilities in China

- Liang Zhang

- Dionne Kringos

- Article: 95

Attitude of nurses and midwives towards collaborative care with physicians in Jimma University medical center, Jimma, South West Ethiopia

- Eneyew Melkamu

- Aynalem Yetwale

- Published: 02 December 2020

- Article: 94

Factors associated with increasing rural doctor supply in Asia-Pacific LMICs: a scoping review

- Likke Prawidya Putri

- Belinda Gabrielle O’Sullivan

- Rebecca Kippen

- Content type: Review

- Published: 01 December 2020

- Article: 93

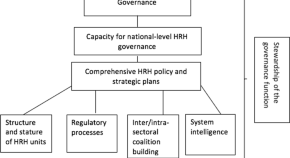

Looking back to look forward: a review of human resources for health governance in South Africa from 1994 to 2018

- Manya Van Ryneveld

- Helen Schneider

- Uta Lehmann

- Published: 26 November 2020

- Article: 92

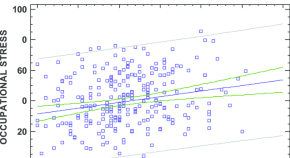

Occupational stress and burnout among physiotherapists: a cross-sectional survey in Cadiz (Spain)

Authors (first, second and last of 6).

- Ines Carmona-Barrientos

- Francisco J. Gala-León

- Jose A. Moral-Munoz

- Published: 25 November 2020

- Article: 91

The relevance of educational attainments of parents of medical students for health workforce planning: data from Guiné-Bissau

- Paulo Ferrinho

- Inês Fronteira

- Clotilde Neves

- Article: 90

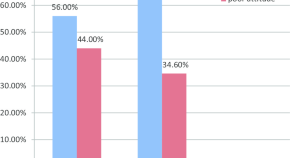

The effect of breaches of the psychological contract on the job satisfaction and wellbeing of doctors in Ireland: a quantitative study

- Aedin Collins

- Alexandra Beauregard

- Published: 12 November 2020

- Article: 89

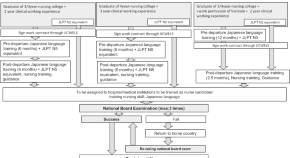

Factors associated with the recruitment of foreign nurses in Japan: a nationwide study of hospitals

- Yuko O. Hirano

- Kunio Tsubota

- Published: 10 November 2020

- Article: 88

- Research to support evidence-informed decisions on optimizing the contributions of nursing and midwifery workforces ,

- Research to support evidence-informed decisions on optimizing the contributions of nursing and midwifery workforces

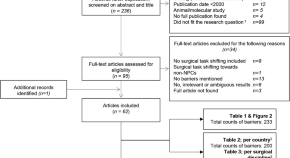

Impact of Medical Doctors Global Health and Tropical Medicine on decision-making in caesarean section: a pre- and post-implementation study in a rural hospital in Malawi

Authors (first, second and last of 8).

- Wouter Bakker

- Emma Bakker

- Thomas van den Akker

- Published: 09 November 2020

- Article: 87

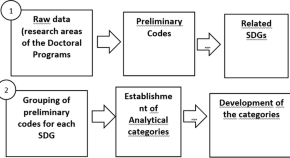

Alignment and contribution of nursing doctoral programs to achieve the sustainable development goals

Authors (first, second and last of 10).

- Isabel Amélia Costa Mendes

- Carla Aparecida Arena Ventura

- Álvaro Francisco Lopes de Sousa

- Published: 07 November 2020

- Article: 86

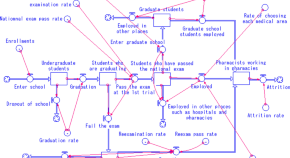

Projecting supply and demand for pharmacists in pharmacies based on the number of prescriptions and system dynamics modeling

- Yasuhiro Morii

- Seiichi Furuta

- Katsuhiko Ogasawara

- Published: 05 November 2020

- Article: 85

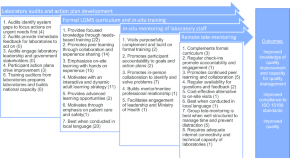

Strengthening the clinical laboratory workforce in Cambodia: a case study of a mixed-method in-service training program to improve laboratory quality management system oversight

- Siew Kim Ong

- Grant T. Donovan

- Lucy A. Perrone

- Published: 04 November 2020

- Article: 84

The COVID-19 pandemic presents an opportunity to develop more sustainable health workforces

- Ivy Lynn Bourgeault

- Claudia B. Maier

- Mohsin Sidat

- Content type: Commentary

- Published: 31 October 2020

- Article: 83

Using data to support evidence-informed decisions about skilled birth attendants in fragile contexts: a situational analysis from Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Tim Martineau

- Joanna Raven

- Published: 29 October 2020

- Article: 82

Virtual adaptation of traditional healthcare quality improvement training in response to COVID-19: a rapid narrative review

- Zuneera Khurshid

- Aoife De Brún

- Eilish McAuliffe

- Published: 28 October 2020

- Article: 81

The experiences of female surgeons around the world: a scoping review

- Meredith D. Xepoleas

- Naikhoba C. O. Munabi

- Caroline A. Yao

- Article: 80

Are health care assistants part of the long-term solution to the nursing workforce deficit in Kenya?

- Louise Fitzgerald

- David Gathara

- Mike English

- Published: 20 October 2020

- Article: 79

The current status of gender equity in medicine in Korea: an online survey about perceived gender discrimination

- Hyun-Young Shin

- Hang Aie Lee

- Article: 78

Increasing access to health workers in rural and remote areas: what do stakeholders’ value and find feasible and acceptable?

- Onyema Ajuebor

- Mathieu Boniol

- Elie A. Akl

- Published: 16 October 2020

- Article: 77

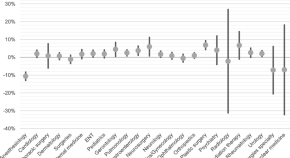

The association between the workload of general practitioners and patient experiences with care: results of a cross-sectional study in 33 countries

- Willemijn L. A. Schäfer

- Michael J. van den Berg

- Peter P. Groenewegen

- Article: 76

Maternal and newborn care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya: re-contextualising the community midwifery model

- Rachel Wangari Kimani

- Sheila Shaibu

- Published: 07 October 2020

- Article: 75

Regulation, migration and expectation: internationally qualified health practitioners in Australia—a qualitative study

- Melissa Cooper

- Philippa Rasmussen

- Judy Magarey

- Article: 74

Experiences of a new cadre of midwives in Bangladesh: findings from a mixed method study

- Rashid U. Zaman

- Adiba Khaled

- Sophie Witter

- Published: 06 October 2020

- Article: 73

Health professional regulation in historical context: Canada, the USA and the UK (19th century to present)

- Tracey L. Adams

- Article: 72

- Health workforce: Accreditation of education and regulation of practice ,

- Health workforce: Accreditation of education and regulation of practice

Ensuring quality of health workforce education and practice: strengthening roles of accreditation and regulatory systems

- William Burdick

- Ibadat Dhillon

- Content type: Editorial

- Article: 71

Exploring the role of shift work in the self-reported health and wellbeing of long-term and assisted-living professional caregivers in Alberta, Canada

- Oluwagbohunmi Awosoga

- Claudia Steinke

- Sheli Murphy

- Published: 24 September 2020

- Article: 70

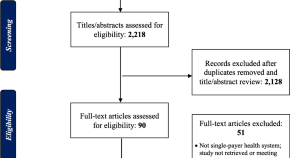

The evidence gap on gendered impacts of performance-based financing among family physicians for chronic disease care: a systematic review reanalysis in contexts of single-payer universal coverage

- Neeru Gupta

- Holly M. Ayles

- Published: 22 September 2020

- Article: 69

Work-life interface and intention to stay in the midwifery profession among pre- and post-clinical placement students in Canada

Authors (first, second and last of 7).

- Farimah HakemZadeh

- Elena Neiterman

- Article: 68

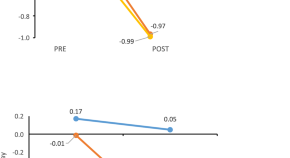

Modern work patterns of “classic” versus millennial family doctors and their effect on workforce planning for community-based primary care: a cross-sectional survey

- Lindsay Hedden

- Setareh Banihosseini

- Rita McCracken

- Published: 21 September 2020

- Article: 67

“They have been neglected for a long time”: a qualitative study on the role and recognition of rural health motivators in the Shiselweni region, Eswatini

- Caroline Walker

- Doris Burtscher

- Katherine Whitehouse

- Article: 66

Midwives’ challenges and factors that motivate them to remain in their workplace in the Democratic Republic of Congo—an interview study

- Malin Bogren

- Malin Grahn

- Published: 17 September 2020

- Article: 65

Development of competency model for family physicians against the background of ‘internet plus healthcare’ in China: a mixed methods study

- Xiaohe Wang

- Published: 11 September 2020

- Article: 64

Plan, recruit, retain: a framework for local healthcare organizations to achieve a stable remote rural workforce

Authors (first, second and last of 13).

- Birgit Abelsen

- Roger Strasser

- Published: 03 September 2020

- Article: 63

A health care professionals training needs assessment for oncology in Uganda

Authors (first, second and last of 14).

- Josaphat Byamugisha

- Ian G. Munabi

- Charles Ibingira

- Published: 01 September 2020

- Article: 62

Implementation and evaluation of a Project ECHO telementoring program for the Namibian HIV workforce

Authors (first, second and last of 37).

- Leonard Bikinesi

- Gillian O’Bryan

- Bruce Struminger

- Article: 61

Biased technical change in hospital care and the demand for physicians

- Jos L. T. Blank

- Thomas K. Niaounakis

- Vivian G. Valdmanis

- Published: 20 August 2020

- Article: 60

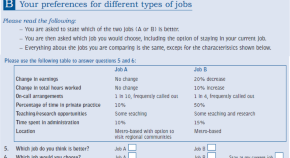

Preferences of physicians for public and private sector work

- Anthony Scott

- Jon Helgeim Holte

- Published: 10 August 2020

- Article: 59

How should community health workers in fragile contexts be supported: qualitative evidence from Sierra Leone, Liberia and Democratic Republic of Congo

- Sally Theobald

- Published: 08 August 2020

- Article: 58

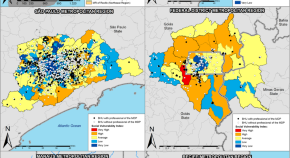

Spatial distribution of the “ Mais Médicos (More Doctors) Program” and social vulnerability: an analysis of the Brazilian metropolitan regions

- Aimê Oliveira

- Jorge Otávio Maia Barreto

- Leonor Maria Pacheco Santos

- Published: 05 August 2020

- Article: 57

Knowledge, attitude, and preparedness toward IPV care provision among nurses and midwives in Tanzania

- Joel Seme Ambikile

- Sebalda Leshabari

- Mayumi Ohnishi

- Published: 03 August 2020

- Article: 56

Involving systems thinking and implementation science in pharmacists’ emerging role to facilitate the safe and appropriate use of traditional and complementary medicines

- Joanna E. Harnett

- Shane P. Desselle

- Carolina Oi Lam Ung

- Article: 55

Measuring motivation among close-to-community health workers: developing the CTC Provider Motivational Indicator Scale across six countries

Authors (first, second and last of 12).

- Frédérique Vallières

- Miriam Taegtmeyer

- Published: 01 August 2020

- Article: 54

A cross-sectional study on preferred employment settings of final-year nursing students in Israel

- Keren Grinberg

- Rachel Nissanholtz-Gannot

- Published: 31 July 2020

- Article: 53

Mentoring the working nurse: a scoping review

- Jerilyn Hoover

- Adam D. Koon

- Krishna D. Rao

- Published: 29 July 2020

- Article: 52

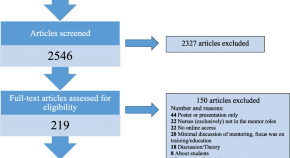

Barriers to surgery performed by non-physician clinicians in sub-Saharan Africa—a scoping review

- Phylisha van Heemskerken

- Henk Broekhuizen

- Leon Bijlmakers

- Published: 17 July 2020

- Article: 51

For authors

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

The abiding, hidden, and pervasive centrality of the health research workforce

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

HR’s New Role

- Peter Cappelli

- Ranya Nehmeh

Though the human resources function was once a strong advocate for employees, in the 1980s things changed. As labor markets became slack, HR shifted its focus to relentless cost cutting. Because it was hard for employees to quit, pay and every kind of benefit got squeezed. But now the pendulum has swung the other way. The U.S. unemployment rate has been below 4% for five years (except during the Covid shutdown), and the job market is likely to remain tight. So today the priorities are keeping positions filled and preventing employees from burning out. Toward that end HR needs to focus again on taking care of workers and persuade management to change outdated policies on compensation, training and development, layoffs, vacancies, outsourcing, and restructuring.

One way to do that is to show leaders what the true costs of current practices are, creating dashboards with metrics on turnover, absenteeism, reasons for quitting, illness rates, and engagement. It’s also critical to prevent employee stress, especially by addressing fears about AI and restructuring. And when firms do restructure, they should take a less-painful, decentralized approach. To increase organizational flexibility and employees’ opportunities, HR can establish internal labor markets, and to promote a sense of belonging and win employees’ loyalty, it should ramp up DEI efforts.

In this tight labor market, cost cutting is out. Championing employee concerns is in.

Idea in Brief

The pendulum swing.

For decades, when U.S. labor markets were slack, HR focused on cost cutting, which meant squeezing employees’ pay, benefits, and training. But now that labor markets are tight, the challenge is to retain workers.

The New Priorities

HR must focus on keeping positions filled and preventing employees from burning out or becoming dissatisfied.

The HR function must educate leaders about the true costs of turnover, address employee anxiety about AI and restructuring, lobby for investments in training, rethink how contract workers and vendors are used, and strengthen diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts.

From World War II through 1980 the focus of the human resources function was advocating for workers—first as a way to keep unions out of companies and later to manage employees’ development in the era when all talent was grown from within. Then things changed. Driven by the stagflation of the 1970s, the recession of the early 1980s, and more recently the Great Recession, HR’s focus increasingly shifted to relentless cost cutting. Decades of slack labor markets made slashing HR expenses easy because it was hard for people to quit. Pay and every kind of benefit, including training and development, got squeezed. Work demands went up, and job security fell.

- Peter Cappelli is the George W. Taylor Professor of Management at the Wharton School and the director of its Center for Human Resources. He is the author of several books, including Our Least Important Asset: Why the Relentless Focus on Finance and Accounting Is Bad for Business and Employees (Oxford University Press, 2023).

- Ranya Nehmeh is an HR specialist working on topics related to people strategy, human capital, leadership development, and talent management and is the author of The Chameleon Leader: Connecting with Millennials (2019).

Partner Center

- Open access

- Published: 14 April 2003

Human resources for health policies: a critical component in health policies

- Gilles Dussault 1 &

- Carl-Ardy Dubois 2

Human Resources for Health volume 1 , Article number: 1 ( 2003 ) Cite this article

124k Accesses

185 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

In the last few years, increasing attention has been paid to the development of health policies. But side by side with the presumed benefits of policy, many analysts share the opinion that a major drawback of health policies is their failure to make room for issues of human resources. Current approaches in human resources suggest a number of weaknesses: a reactive, ad hoc attitude towards problems of human resources; dispersal of accountability within human resources management (HRM); a limited notion of personnel administration that fails to encompass all aspects of HRM; and finally the short-term perspective of HRM.

There are three broad arguments for modernizing the ways in which human resources for health are managed:

• the central role of the workforce in the health sector;

• the various challenges thrown up by health system reforms;

• the need to anticipate the effect on the health workforce (and consequently on service provision) arising from various macroscopic social trends impinging on health systems.

The absence of appropriate human resources policies is responsible, in many countries, for a chronic imbalance with multifaceted effects on the health workforce: quantitative mismatch, qualitative disparity, unequal distribution and a lack of coordination between HRM actions and health policy needs.

Four proposals have been put forward to modernize how the policy process is conducted in the development of human resources for health (HRH):

• to move beyond the traditional approach of personnel administration to a more global concept of HRM;

• to give more weight to the integrated, interdependent and systemic nature of the different components of HRM when preparing and implementing policy;

• to foster a more proactive attitude among human resources (HR) policy-makers and managers;

• to promote the full commitment of all professionals and sectors in all phases of the process.

The development of explicit human resources policies is a crucial link in health policies and is needed both to address the imbalances of the health workforce and to foster implementation of the health services reforms.

Introduction

The concern with growing inequalities in health status, problems of access and falling returns for investments in health care and the difficulty of controlling the growth of costs have prompted most countries to engage in reforms of their health sector. In low-income countries, multilateral and bilateral international organizations as well as major foundations now give a high priority to health as an essential part of the fight against poverty. Major investments are currently made by international agencies and foundations to increase vaccination rates in countries (for example, via the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations) and to combat HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria (Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; Roll Back Malaria alliance).

Concurrently, the debt relief process launched by international financial agencies is increasing the resources available for health in the poorest and most disease-ridden countries. Forty-two countries (34 in Africa alone) are eligible for debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative (HIPC), launched by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. A report of May 2002 estimated that the 26 countries that have reached the decision point (at which they have access to the full advantages of the initiative) would see their total debt reduced by two-thirds between the beginning of the initiative (1999) and 2005. This represents a sum of about USD 40 billion, of which 60% is expected to go to education (40%) and health (20%, not including AIDS), an average amount of USD 830 million per year to the social sector. Five more countries are expected to reach the decision point before the end of 2002 [ 1 ].

Paradoxically, the ability of poor countries to pursue actions made financially viable by access to new resources has never been so limited. This is due to major problems with regard to their health workforce, such as loss of personnel and productivity linked to the effects of AIDS, migration from the public sector to the private sector, and migration from the health sector to other sectors, as well as migration to richer or more stable countries. These problems are often caused, or at least exacerbated, by inadequate policies and practices at the levels of training, planning and deployment of staff, management of performance and definition of working conditions.

While acknowledging the fundamentally political character of human resources for health (HRH) issues, this article argues for the need for more rational health workforce policies as a sine qua non for the successful implementation of health policies. The discussion is structured into four sections. Drawing on the recent literature, Section A formulates the rationale for including explicit human resources policies in health policies, which most countries, rich and poor, have yet to do. Section B presents the specificities of the process of devising, adopting, introducing and evaluating HRH policies. Sections C and D formulate proposals on how better to develop HRH policies and discuss what is known about their conditions of success.

Why HRH policies are needed

The usefulness of health policies.

The idea of formulating health policies is relatively recent. Until the end of the 1940s, national policies tended to be a distinctive feature of planned economies. As the Marshall Plan made the drafting of national plans a condition for the financing of Europe's reconstruction [ 2 ], national policies became a normal instrument of policy.

In poor countries, the drafting of national policies also became a condition of access to aid [ 3 , 4 ]. In the health sector, it took the form of statements and plans aiming at reaching the goal of Health for All by the Year 2000 (HFA) set by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the late 1970s. Following Alma-Ata, the Member States of WHO adopted a strategy in 1981 setting objectives and priorities within the framework of HFA. Three years later, a regional strategy was adopted by 38 Member countries of the European Region of WHO. This movement was followed up nationally and in all continents, by measures taken by ministries of health aimed at devising policies in which priority-setting continues to be an essential part. Although countries have hardly come close to achieving the goal of HFA, policy-makers now agree that health policies are nonetheless crucial tools that can help in various ways (see Table 1 ):

A health policy facilitates planning. According to WHO, policies help to develop a vision of the future, to define short-, medium- and long-term references, to determine objectives, to set out priorities, to delegate roles and to define means of action and institutional arrangements [ 5 , 6 ].

A health policy can support decision-making in a context of greater public awareness of the harmful effects of incoherent policies and of greater public scrutiny of decision-makers regarding the costs and benefits of proposed options. The public expects governments to be more selective and to adopt strategies that are effective, efficient and reliably high performing [ 7 , 8 ]. An explicit framework for identifying problems, for choosing priorities and objectives, and for rational assessment of alternatives for intervention can be a tool for decision-makers to justify their choices [ 9 ]. The complexity of the health field is another argument that pleads in favour of the development of a policy framework for guiding decision-making [ 10 ]. Health problems are multifaceted and may require various sectors to work in conjunction. Actions undertaken in the health sector may have significant and long-lasting effects both on the health of individuals and on other economic and social sectors. Wrong decisions in this field may therefore have particularly disastrous effects. Thus, it is important that in the health sector, more than in any other field, the decision-making process should be anchored in solid analytical skills, based on the best available knowledge, supported by proven management techniques, and guided by a clear vision of the hoped-for future and the means needed to get there.

A health policy provides a framework for evaluating performance. By setting expectations, objectives, priorities and strategies and the resources required to achieve them, policy simultaneously sets out criteria on the basis of which actions can be evaluated while providing a frame of reference that may be used by health professionals at different levels to understand their responsibilities.

A health policy can help to rally professionals and other sectors around health problems and to legitimize actions. When it is part of a judicious planning of change, the development of health policies provides a unique opportunity for building consensus around health issues and for allowing citizens to voice their opinion, thus giving a greater degree of legitimacy to actions that will be proposed later. Critical and difficult decisions, such as new allocation of resources or rationing services, may be made more acceptable to interest groups if they are taken in the context of a political process that has brought the main players together.

Limitations of current approaches to human resources management (HRM)

It is not enough for health policies to be intrinsically good. If they remain at the planning stage and do not take economic and social realities into sufficient consideration, their influence is likely to remain minimal [ 6 ]. Their success depends heavily on how their development and implementation process is conducted. Many analysts argue that a major failing of health policies is precisely the insufficient consideration given to HRH issues [ 11 , 12 ]. In many reforms, there is discordance between the elevated attention given to issues of financing and structural transformation and the low attention given to HRH issues [ 13 ], which are often treated as just another production factor [ 14 ]. The implications of reforms for HRH are often considered only in retrospect when it emerges that proposed plans (a) cannot be implemented because of unaffordable personnel costs; (b) they are opposed by professional groups; (c) they are shown to be unrealistic in view of the baseline situation; or (d) they require modifications in the organization of work that are too difficult, in view of the current organizational capacity or of the political acceptability of the modifications [ 15 ]. The low level of interest in human resources issues is surprising if we consider the crucial role played by the health workforce in the process of achieving the objectives set by health policies [ 16 ]. But it is more easily understood when the difficulties of addressing these issues are considered, as will be illustrated later.

Even where HRH issues receive attention, the way they are addressed is usually characterized by:

A limited vision of HRM , reduced to personnel administration , i.e. operational tasks relating to recruitment, maintaining discipline and handling complaints. This lowers the status of HRH administrators and isolates them within the organization [ 17 ]. HRM of this type does not address all aspects of workforce issues.

Dispersal of accountability and lack of coordinated actions. Those responsible for HRH development in health ministries often limit their role to staff planning and allocation, and leave other, more delicate matters to political decision-makers. This practice has led to a cleavage between health policies and the HRH operations required to implement them [ 18 ]. Training programmes, for instance, may duplicate each other and not always correspond to needs. The absence of regular strategic consultations with the main actors concerned with workforce planning and development opens the door to uncoordinated, even contradictory interventions [ 19 ].

Reactive attitudes in the management of the health workforce. It has been observed, for example in Turkey [ 20 ], that governments often set very broad, annually adjusted HRH objectives outside a general policy framework and without an explicit link to health needs. Opening new schools, increasing admissions in existing schools or even temporarily easing restrictions on immigration of health personnel are often decided punctually to address problems that could easily have been anticipated [ 21 ].

Subordination of HRH decisions to economic criteria. In many instances, health workers are treated as mere production tools, such as when financial incentives are introduced to increase productivity, without taking into account other dimensions of work. As a result, these measures regularly fail to produce the expected results [ 22 ]. Governments tend to be more concerned with macroeconomic issues, such as the size of the workforce and the wage bill [ 23 ], and easily overlook other issues of importance relating to work organization, personnel motivation and individual performance.

A short-term view of HRM. This refers to the tendency to provide symptomatic responses to problems without looking at their causes or considering their long-term consequences. In Canada, nursing is in a critical situation because of difficulties in recruiting and retaining personnel. The causes of these problems are well known to be linked to conditions of practice, working conditions and the image of the profession, but little is done to address them, even when radical reactions from the nursing profession, such as long-lasting strikes, have to be faced [ 24 ]. In other cases, staff numbers have been reduced to meet fiscal constraints, which subsequently created shortages much more difficult to rectify. In Quebec, such across-the-board reductions in the mid-1990s as part of a commitment to balance the government budget led to shortages of certain professional categories, both clinical and managerial; excessive workload; disruption of performing teams; and increased psychological distress among staff and users of services [ 25 ]. This short-term management is also common among aid donors, who tend to support actions that fit their project cycle and to ignore problems that require long-term interventions, but whose impact may remain uncertain [ 19 ].

These observations give an idea of the difficulties that need to be addressed before HRH issues can be more firmly incorporated into health policy. Workforce problems are among the most complex matter on the international health reform agenda. Even in countries where national plans for the development of HRH have been made, they have been implemented only partially, and few countries evaluate policy advances in this area [ 5 ]. Hence, HRH issues remain of crucial importance and their omission from health policy agendas can only be prejudicial to health sector reforms.

Workforce issues and health policies

There are at least three arguments for giving serious attention to workforce issues in policies and even for designing specific HRH policies:

More than any other type of organization, health organizations are highly dependent on their workforce. The growth and development of any organization depend on the availability of an appropriate workforce, on its competences and level of effort in trying to perform the tasks assigned to it [ 26 , 27 ]. HR are a strategic capital in any organization (see Table 2 ), especially in service and health organizations, where the various clinical, managerial, technical and other personnel are the principal input making it possible for most health interventions to be performed. Staff diagnose problems and determine which services will be provided and when, where and how. Health interventions are knowledge-based and the providers are the "guardians" of this knowledge [ 11 ].

HR account for a high proportion of budgets assigned to the health sector [ 32 ]. The health sector is a major employer in all countries. The International Labour Organisation reckons that 35 million persons are currently employed in the health sector worldwide [ 33 ]. While health expenditure claims an increasingly important share of gross domestic product, wage costs (salaries, bonuses and other payments) account for between 65% and 80% of the recurrent health expenditure [ 34 , 35 ]. These costs are strongly linked to the ways in which HR are deployed and used [ 20 ]. In community-based health care, which relies less on equipment and advanced technology, HR have an even more prominent role and account for an even higher proportion of total costs [ 36 ]. In addition to representing direct costs, health care providers, particularly those who have the autonomy to prescribe, generate other costs. When incentives, such as payment by fee-for-service, encourage production, there is a risk of inducing demand for non-essential services. Studies of geographical variations of the use of health services show that it is often explained more by professional decisions and patterns of practice rather than by population needs [ 37 , 38 ].

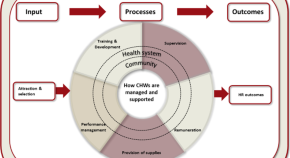

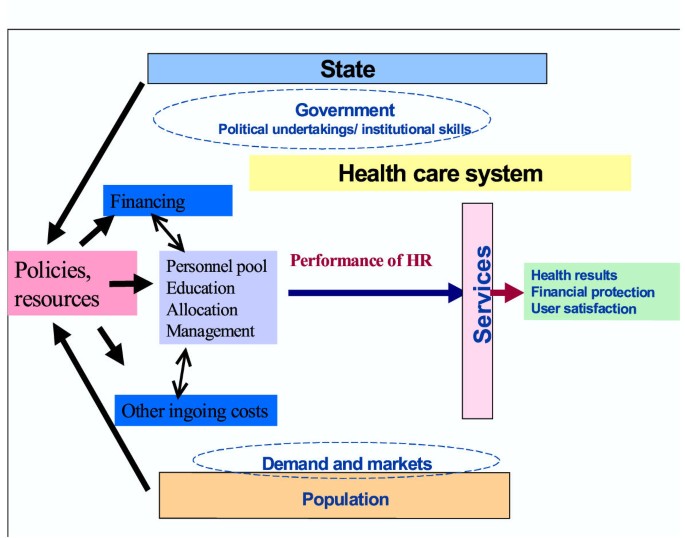

The economic and human costs of poor HRM are particularly high in the health sector. The quality of health services, their efficacy, efficiency, accessibility and viability depend primarily on the performance of those who deliver them [ 5 , 39 ] The performance of providers is, in turn, determined by the policies and practices that define number of staff, their qualifications, their deployment and their working conditions [ 40 ]. Crucial choices must therefore be made in relation to the processes that will influence the performance of the workforce, as defined in Table 3 , in terms of productivity of personnel, technical and sociocultural quality of services and organizational stability, on which the performance of health services will depend (see Fig. 1 ). Wrong choices may have harmful effects on the functioning of health services and, consequently, on the ability of these services in helping to attain health policy objectives. Also, given that they have long-term effects, these decisions are usually difficult to correct.

Relationship between the performance of human resources and the performance of services

The challenges of health system reforms

The challenges raised by sector reforms aiming at reducing costs, improving performance, increasing equity, decentralizing management and reviewing patterns of health care provision have a direct impact on staff, the very people on whom the success of reform depends [ 22 , 41 , 42 ]. These are illustrated here:

Reduction of costs. The response to inflation in health expenditure is often to reduce costs by stimulating efficiency. Given the proportion of the health budget absorbed by the workforce, any attempt to reduce costs or to improve efficiency calls for measures that directly affect staff. These typically include:

improved planning to avoid overstaffing . This requires more information on the staffing situation, the application of more accurate methods for determining personnel requirements, and closer coordination between supply of staff (often independently controlled by education institutions) and demand or capacity of absorption.

better distribution of personnel by categories : for example, increasing the proportion of assistants and technicians in order to improve the productivity of specialized staff in performing tasks requiring higher skills.

recognition of new categories of personnel , such as the clinical nurse, or giving official recognition to existing providers, such as midwives or traditional healers, that have been chosen in recent years.

modification of the working conditions to promote staff mobility and greater flexibility in personnel deployment or to rationalize methods of remuneration to bring them more in line with the expected performance.

The improvement of performance entails actions such as reviewing incentive systems, the development of new skills, improving work organization, and the adoption of new strategies of professional development.

The improvement of equity of access to services cannot be achieved without a more balanced redistribution of personnel between isolated and urban areas, and between rich and poor regions. It also depends on the provision of appropriate incentives for recruiting, and above all, retaining staff in the less well-served areas.

The decentralization of services , which is on the agenda of many governments, entails transfer of decision-making posts to intermediate and local levels. At the same time, it raises urgent needs for the development of HRH required to fill these new posts, particularly in management.

The proposed changes in health care models and the promotion of primary care are major challenges in terms of redefining professional roles and integrating services. They require health professionals to be more mobile, more versatile and to acquire new skills and the ability to work in multiprofessional teams. They suppose that non-medical staff will play an extended role in providing primary care services and that there will be a higher use of alternative treatment methods and a greater acceptance of non-traditional providers.

In labour-intensive sectors, the process of change entails important adjustments in the job market. Evidence suggests that these could be implemented more easily if HRH issues are dealt with at the policy development and planning stages. In Kazakhstan, the success in primary health care reform has been attributed, in large part, to the policy for mobilizing HRH, either by fostering professionalism among providers, providing adequate financial incentives or giving primary health care units more autonomy. In Chile, however, the reform of the health sector begun in the 1990s has run up against the lack of engagement of health professionals, who had a different perception of reform from that of the government [ 39 ]. The successful experience of Costa Rica is another case that illustrates the benefits of making HRH policy part of a health policy [ 16 ].

The need to anticipate the potential effects of macroscopic social trends affecting health systems on the health workforce (and consequently on the provision of services)

Health care systems are affected by a number of major trends that can have important effects on the organization of work and may consequently require adjustments if the objectives of equity, efficiency and quality are to be attained.

Technological transition. Technological innovations have already brought radical changes in how most diseases are treated. Health professionals must adjust their roles and skills accordingly. New information technologies and telecommunications have a high potential for improving productivity, by allowing health professionals to exchange clinical data over a distance in real time or to have immediate access to new knowledge. They allow greater flexibility in the organization of work, improve communication between professionals and create jobs in new sectors. At the same time, they eliminate jobs, impose new skill requirements and require new investment in terms of training.

Telemedicine, the term given to the various applications of information technology and telecommunications for health service delivery and health information over long and short distances, has the potential importance of reducing costs and injuries linked to patient transfer, of improving the provision of services in isolated regions, of giving access to distance training and of fostering development of domiciliary care [ 43 , 44 ]. On the other hand, it may require modifications in conventional modes of work organization and remuneration or new working methods (teamwork and networking, sharing of information, use of computers).

Sociodemographic transition. Demographic changes have a substantial effect both on the demand for services and on the workforce providing them. The ageing of the population in industrialized countries, likely to increase the use of health services [ 45 ], will also be accompanied by a fall in the working population. For example, 42% of public sector employees in Finland are due to retire in the next 10 years [ 46 ]. Tools for management of human resources should be adapted to this ageing workforce. Training programmes and compensation programmes ought to be adjusted to meet the specific needs of both young staff and older staff. Another aspect linked to this transition is the growing proportion of women in the job market and their desire to combine their career and their familial roles. Female doctors work fewer hours per week, retire earlier and take time off more frequently than their male colleagues, factors that affect the planning of the medical workforce [ 47 – 49 ]. The impact of the HIV epidemic is worst in the most productive age group, including the health workforce. In the low-income countries, especially African countries, which are paying the heaviest toll, the epidemic has consequences on the health workforce in the form of reduced numbers, absenteeism, reduced productivity and psychological distress [ 50 ].

Globalization of markets. At least two factors linked to globalization of markets have direct effects on the health workforce:

structural adjustment measures undertaken by states have included radical reviews of their public sectors and often led to cuts in health and social programmes, reduced numbers of staff and, in most cases, to a deterioration of working conditions [ 33 ].

the use of market mechanisms to manage health care systems has led to a redefinition of the role of the state, expected to concentrate more on its role as regulator and to give more scope to the private sector in the provision of services. The case of Nicaragua may be cited in this regard [ 51 ]. The traditional relationship between the employer-state and health personnel has been modified. Centralized negotiations between national unions and governments are supplanted by management of employment relations at the local level; the case of Great Britain illustrates this point [ 52 ]. The career structure is no longer so clearly defined, and as a consequence workers are less inclined to show loyalty to an organization that may make them redundant when it restructures.

Changes in the behaviour of consumers and in their relationships with health professionals. In rich countries, consumer demands are more diversified, more sophisticated and better informed, and consumers easily question the capacity of their governments to meet these demands [ 45 ]. As taxpayers, they are concerned about the rising costs of the health services, but as users, they want access to services of the highest quality. They expect administrators and health professionals to do better with the same resources. The same trend is seen in low-income countries when consumers become better informed about which services are available to others or should be available to them.

Mobility of the workforce and the brain drain. In industrialized countries, conditions of mobility of the workforce, in particular the highly qualified workforce, are now negotiated within the framework of regional agreements, aiming at greater standardization of qualifications between countries [ 53 ]. In developing countries, however, this mobility has often taken the form of a more brutal exodus of skills, depriving countries of rare resources crucial for the development of their health systems [ 53 ]. As the job market is rapidly changing and competition is increasing, public health care systems must also cope with difficulties of retaining personnel who are attracted by better offers from the private sector or who decide to pursue other more lucrative professional activities [ 50 ].

As a result of these major trends, vertical, pyramidal and rigid forms of work organization are replaced by more flexible structures and methods of deployment. The limited horizon of the local or regional job market expands to cater to new global economic orders. The traditional focus on products and services is supplanted by a client-centred approach that emphasizes needs and preferences. The traditional division of work that put a premium on specialization is yielding to a greater integration of health services provision and to teamwork. Production based on information and knowledge is replacing a machine-based mode of production. Stable and protected working relations, with the underlying assumption of a lifetime career, are giving way to flexibility of work and employment [ 54 , 55 ].

The arguments outlined here indicate the crucial role of HRM in improving the performance of health systems and implementing reforms and suggest that HR allocation cannot be left to the unregulated market. Strategic planning is essential to control the effects of the complex factors that affect HR. Technocratic planning as practised in the past is highly ineffective, as illustrated by the chronic imbalances (see Table 4 ) experienced by most countries [ 56 , 57 ], i.e. mismatch of numbers, qualitative disparity, unequal distribution and a lack of coherence between HRM practices and the overriding concerns of health policy (see Table 5 ). These imbalances prove to be major limiting factors to achieving the objectives of health sector reforms or to implementing health policy.

Which human resources policies?

What is a policy.

The notion of policy is not always conceived or understood in a uniform manner. Policy is sometimes perceived as a product (principles, declaration, law) that serves as a frame of reference for action; sometimes as a process that ought to lead to the attainment of certain goals [ 58 ]. The policy process itself, however, gives rise to numerous interpretations. Two major approaches can be distinguished [ 59 ].

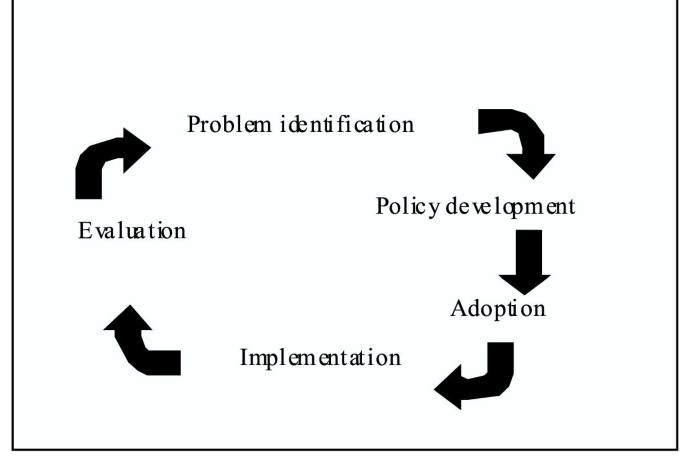

The traditional approach understands public policy as a cyclic process, the different stages of which can be separately analysed (see Fig. 2 ). In order to resolve a problem, a policy is devised, a number of objectives are set and strategies are defined to achieve them. The operational implementation of the policy is expected to lead to resolution of the problem [ 60 – 64 ].

Policy cycle

Here, the policy process is assumed to be rational, to follow a logical succession of stages and to be based on an objective evaluation of different alternatives and on scientific knowledge [ 65 ]. Critics [ 61 , 66 – 68 ] have shown that to understand policy-making, account had to be taken of the uncertainty inherent in all decision-making, the limited rationality of the agents, the power relations in social systems and the ideological biases influencing the decision-makers (see Table 6 ).

The alternative approach to technical rationality, from which only a very partial explanation of policy can be derived [ 27 ], puts the emphasis on the interpersonal and contextual relations of the policy process. Policy is conceived not as a sequential process but as an integrated process in which values and differences are made explicit, consensus agreements sought, compromises made, alliances formed and action justified [ 69 – 72 ]. This is a political exercise that goes beyond technical activities and calls for a process of exchange and negotiation between various interest groups. For Kingdon [ 73 ], political changes rarely stem from a linear process, but tend to result from repeated interactions between three flows of ideas relating to defining problems, proposing solutions and obtaining policy consensus. Change happens when these flows converge, creating a window of opportunity that can be seized by policy-makers [ 73 ].

Characteristics of HR activities in the health sector

In HRM the two planning approaches are not mutually exclusive, and can even be complementary. The rational approach encourages a recognition of the role of information, of modern analytical techniques and of decision-making tools for developing coherent policies These are necessary but not sufficient conditions. The second approach brings an appraisal of the political, economic, cultural and social context in which the development and implementation of policies take place. But there are also some specifics to the health context that need to be taken into account in the process of developing and implementing HRH policies:

The intersectoral nature of issues linked to HRH and the variety of participants and sectors involved. The causes of HR problems in the health sector are various and complex. Solutions depend on many inputs (financial resources, education programmes, working conditions), which are in many instances outside the control of the health sector decision-makers or HRM administrators [ 74 , 75 ]. In most industrialized countries, such as Canada or the countries of Western Europe, central unions negotiate working conditions directly with the government and sign collective agreements that leave administrators of health organizations little room for independent decisions [ 17 , 25 ]. Responsibility for the production of personnel, for the definition of curricula and for certification criteria is usually in the hands of independent training institutions. Practice standards are generally defined by professional bodies. In other words, strategies for intervening on the health workforce cannot be decided autonomously by a single organization or single unit at the ministry of health. They have to incorporate the viewpoints of a wide variety of institutions, participants and interest groups who have a stake in the decision-making and in implementing actions.

The time-lag between decision-making and outcome. Contextual changes influencing the demand for health services and tendencies within the workforce cannot be dealt with in a short time. For a number of decisions relating to the health workforce, short-term or medium-term projections are not sufficient. Hall [ 76 ] shows that a 10% rise in the number of students registering with medical schools will produce only a 2% increase in the supply of doctors after 10 years. A substantial lapse of time is therefore required to bring about major quantitative and qualitative changes in the health workforce or to rectify the adverse effects of poor decisions [ 77 ]. Accordingly, HRH policies in reforms and attempts to expand health services should allow for the intervals needed to train and develop the workforce. They must equally anticipate the long-term impact some major trends such as ageing of the population are likely to have on the demand for services and on the workforce demand.

Strong professional dominance. Health care systems are widely influenced by the role of professionals whose training emphasizes the value of autonomy and professional self-regulation [ 78 ]. Generally speaking, professional structures are well established, supported by laws, guidelines, culture and history [ 79 ]. Various professional categories assume distinct roles and have their own training structures and regulatory mechanisms. These groups also tend to have a distinctive culture and a very pronounced identity that may complicate implementation of changes. Strong in the conviction of their cultural and symbolic power and in their ability to rally public opinion behind them, they may hinder the implementation of new policies if there is no clear understanding of the proposed changes, or if these changes are perceived as affecting them negatively [ 23 , 80 ]. All these factors indicate that the process of development and implementation of workforce policies in the health sector must be an ongoing process of adjustment, not only to the needs of the population but also to the changing expectations of the personnel, and that it should be conducted with their full participation [ 81 , 82 ].

The interdependence of the different professional categories. Most health occupations are highly interdependent when carrying out their tasks. Problems in one professional category may spill over into another. For example, a shortage of nurses resulting from inadequate planning may have adverse effects on the work of doctors.

The role of the state as the principal employer. The state remains the principal employer in the health sector, despite a tendency to give increasingly greater scope to the private sector in the provision of services [ 33 ]. HRH are expensive to produce and in terms of recurrent expenditure. Any inadequate workforce policy that encourages overproduction of personnel, excess consumption of resources or poor utilization of available personnel has a direct effect on public finances and further reduces scarce resources that could have been assigned to other sectors of the economy.

The high proportion of women employed in health services. The health sector is also recognized as being a major employer of women [ 83 ], who are increasingly active in the job market while fulfilling family responsibilities. As seen in Zimbabwe, women working in the health sector often receive lower salaries and have fewer opportunities than their male colleagues to rise to the higher echelons of the hierarchy [ 84 ]. Concentrated in specific professional categories such as nursing, they often pay the highest toll when budgets are cut [ 33 ].

The ambiguity of the relationship between health needs, service requirements and resource needs (human or material) in the supply of these services. Understanding of health needs is imperfect. Understanding of the services required to respond to needs is also imperfect. The relative contribution of health services is not well understood. The development of HRH policy has to deal with uncertainty and with many other factors – political, economic, social and cultural – that influence these relationships [ 85 ].

Deficiencies of the market. In other sectors of the economy, the job market responds to the law of supply and demand, and adjustment processes may be both more easy and less costly [ 82 ]. But in health, where there are imperfections as in any market, the state may be required to intervene in order to see through the necessary adjustments within the framework of the political process. The challenge here is to overcome the rigidity associated with certain institutional mechanisms (unions, professional regulations, etc.) that may restrain the implementation of the adjustments required or render them more costly.

The content of HRH policies

Martinez and Martineau [ 41 ] suggest four categories of issues that HRH policies should address:

Planning for the supply of personnel. This aims to ensure adequate numbers of personnel in the different employment categories and that personnel are available and distributed equitably and coherently between geographical regions, establishments and levels of care. The challenge is to deploy personnel of adequate quality in sufficient numbers at the right time and place; this includes equitable gender distribution within the limits of what the country can afford.

Education and training. This involves providing the different categories of personnel with the skills required by the objectives set by health policies. Policy actions may include: adaptation of the training curricula to health policy objectives and to service requirements; development of new teaching and learning methods; monitoring of skills and training requirements; development of training infrastructures; training of trainers; and the regulation of training institutions and programmes.

Management of performance. This relates to the optimization of the service production process and to making sure that staff are encouraged to provide effective, efficient, high-quality services that meet the needs and expectations of citizens. Guidelines regarding the organization and division of work, practice standards, payment methods, circulation of information, management practices and tools, evaluation and accountability mechanisms and, more generally, the strategies for maintaining and upgrading the quality of services provided are included here.

Working conditions. Expected policy guidelines address methods of recruiting and retaining staff, career management, mechanisms of mobility, methods and levels of remuneration incentives, management of labour relations, and systems of evaluation.

As critical choices are made in relation to objectives and defining priorities and strategies, the question arises: Which criteria can help? Two sets of considerations can help answer that question.

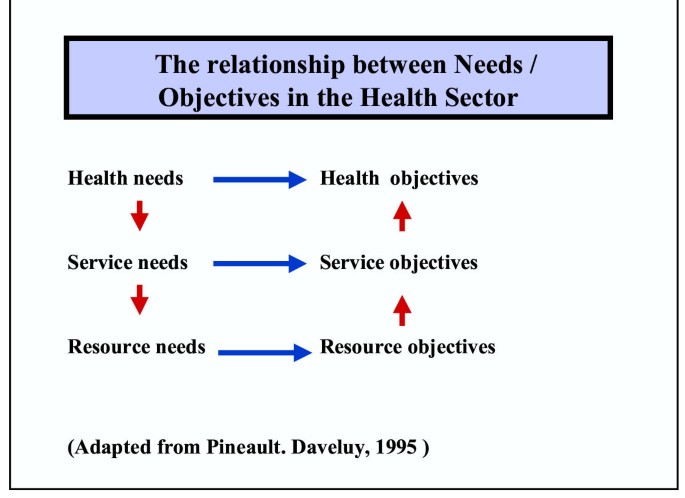

First, HRH-related objectives – which need to be coherent with health objectives and health needs – should be subordinated to health services [ 86 ] (see Fig. 3 ).

The relationship between needs and objectives in the health sector

Second, policy choices are not neutral, but are always derived from sets of values that condition their social acceptability, legitimacy and consequently the probability of success of their implementation. Accordingly, the following would help the choice of objectives, priorities and strategies:

an explicit statement of the values that will inspire policy and to which decision-makers will be bound: equity in access? the importance of the personnel as associates in the development and implementation of the policies? equality between men and women? a good balance between family and professional life?

a clear identification of service objectives to which HRH policies are expected to contribute: more balanced distribution of services, level of quality sought, continuity of services, efficiency.

quantifiable objectives, covering a specific period and covering all aspects of HR issues. The policy should be able to justify how these objectives are linked to service objectives.

strategies considered and the required means for attaining these objectives.

monitoring and evaluation.

Prescriptions for modernizing the policy process in health workforce development

The literature presents at least four "prescriptions" to adapt the policy process relating to the health workforce:

(1) : HRH policies must be comprehensive, i.e. go beyond personnel administration and incorporate all aspects of HRM. [ 11 , 18 , 41 , 87 ] HRM should be recognized as a set of trans-sectoral activities, all necessary , acting globally on the HR system so that the workforce is used in ways that effectively contribute to meeting the health needs of the population. HRM will continue to include traditional functions such as recruitment of personnel, but also others, such as negotiations with professional groups and unions, as reforms usually envisage changes in working conditions, allocation of responsibilities or training programmes. Closer relations need to be maintained with various ministries, such as that of education for training issues, or finance for matters relating to remuneration and to incentive schemes. The policy challenges, therefore, are to involve HR managers in all decisions relating to the workforce and to develop coordinated (across both jurisdictions and stakeholders) "policy packages" [ 88 , 89 ].

(2) : The development and implementation of HRH policies should reflect the integrated, interdependent and systemic nature of the different components of HRM. Acknowledging the systemic nature of HRM calls for a recognition of (1) the contribution of each of its functions and their mutual dependencies; and (2) the links between HR policy, health policy and the environment in which they are to be implemented.

The HRH subsystem brings together a number of interdependent functions working in synergy that determine the performance of any health care system: staffing, management of performance, training and definition of working conditions [ 41 , 81 , 90 ]. The challenge here is to ensure that these basic functions are dealt with in a coherent manner. Any action affecting one of them may have effects on other functions. Operations intended to balance the distribution of personnel may, for instance, have consequences on staff motivation and performance. The development of in-service training may have effects on the provision of services. Letting staff surplus build up may make it difficult to provide professional development opportunities. Reducing staff to meet cost restrictions may affect the quality of services. The internal coherence of the HR subsystem depends on balancing its different functions. Youlong et al. [ 91 ], referring to China, showed how a system of professional regulation, when not based on a systemic approach, may have an unequal impact on rich and poor regions and work against an equitable distribution of care.

The HR subsystem also has exchange and interdependency relations with other parts of the health care system. The quality of a service depends on its personnel, but also on the settings in which it develops and on the resources available to provide services. In other words, the issue of HRH cannot be dealt with or managed in isolation. HRH policy development and implementation must allow for the fact that personnel is only one input among others that contribute to a balanced health system. Steps must be taken to ensure that HR meet the objectives of health policies while concurrently ensuring that the broad thrust of health policy allows the conditions to be created for full development of the workforce.

(3) : Given the critical and strategic role of HR in health organizations, the implementation of HRH policies requires that decision-making and management be more proactive [ 23 ]. A more strategic conception of and approach to HRM require a higher degree of sensitivity to the many signals of change emanating from both inside and outside health care organizations themselves: changes in laws and other regulations; economic trends (labour market, growth rate, economic priorities of the government); organizational changes; technological progress; and sociocultural and demographic changes.

HRH managers should be capable of recognizing and interpreting these different signals, and of acting judiciously in response to them by making appropriate adjustments to the workforce [ 92 ]. Permanent monitoring of macroscopic changes and of organizational changes and their consequences for HRH is needed to identify new environmental challenges and emerging problems [ 29 ]. The recruitment and retention of high-level HRH managers, with enough autonomy to implement policies flexibly, is a correlate of this prescription and is the real test of the commitment of political leaders to a more rational and need-centred HRM.

(4) : The mobilization of all stakeholders is a key element in the development, implementation and evaluation of HRH policies. Many players influence or have the potential to influence changes in the workforce, given that they control or influence one or several of the key functions cited above [ 40 ]. Minimally, these include:

those who define and negotiate working conditions: ministries of health, finance, civil service, planning, unions, hospital boards.

those who define standards of professional practice: professional councils, governmental regulatory agencies.

those who produce health workers: training establishments, ministry of education.

those who produce services: health establishments and their staff, both private and public; professionals.

those who consume services: users, user associations.

those who finance services: governments, citizens, private insurers, donors.

Recognizing the roles of these players makes planning health workforce actions part of a political process in which the different key players express their opinions and exert their influence. Involvement of these different players in policy development, even though it will demand more energy and time, may in fact facilitate the subsequent adoption and implementation of policy and ensure that its effects are sustained.

These different prescriptions highlight a number of challenges and needed actions:

When developing policy: ensure that objectives and priorities affecting the different aspects of HRM are made explicit; ensure that objectives and priorities are consistent with the requirements of services, health needs and available resources; involve all sectors concerned in the definition of objectives and priorities.

When implementing policy: ensure that the mechanisms required for coordination of the different actions are properly in place; ensure continuing monitoring of signals from inside and outside the system; mobilize resources required for the different actions; foster synergy between the different HRM functions.

When evaluating policy: ensure wide participation in evaluation; collect relevant information on the different components of HRM; use results of evaluation for creating an evidence base and for upgrading actions.

Conditions for success of human resources policies

The success of policy remains conditional on a number of factors, of which four appear to be especially crucial in the context of HRH:

Institutional/technical capacities

The development, implementation and evaluation of HRH policies is part of a complex process relying on multiple analytical tasks: analysis of needs, planning, evaluation of programmes, economic evaluation, policy analysis, demographics and statistics, teaching methods, etc. Capacities required for their performance are essential resources. Saltman and Figueras [ 93 ] point out that countries that have had the most success in reforming their health systems are precisely those that have been able to mobilize technical capacities to design coherent and viable policies. Decision-makers who understand the specific features of the health workforce, its critical role and HRM and its importance for supporting reforms are essential. But for planning and implementing appropriate actions in relation to the many components of HRM, specialized technical capacities are needed.

Policy implementation depends also on the strength and stability of institutions. Thain [ 94 ] stresses the importance of constitutional, political, informational and technological resources that help to construct an environment that promotes sound policy formulation and implementation.

National capacities for developing and implementing HRH policies are inadequate [ 74 ] because skills are rare and institutions are weak, or the information base is deficient and good information is not available. Regularly updated statistical data are essential to the formulation of appropriate and coherent policies. This includes data on health needs, on existing services, and on personnel and their distribution (in terms of geography, sex and professional categories), their training and their working conditions.

To reinforce national capacities, Martineau and Buchan [ 95 ] suggest actions on two fronts: (1) strategic , by providing national leaders with the means to develop a clear vision of health needs, environmental constraints and options for the development of the workforce. HRH policies externally imposed, by donors or otherwise, inhibit the development of this kind of national leadership and hinder the adaptation of policies and programmes to the national context [ 96 ]; (2) operational , by developing the specific skills required by each component of HRM.

Stepping up technical capacities requires time for training and building experience. This also applies to the consolidation of institutions. These actions change the power relationship between actors, challenge old practices, and call for new regulatory mechanisms, all of which generate resistance and require long periods of adaptation.

Political feasibility

Commitment is crucial for both the development and the implementation of policies. In a climate of instability in which decision-makers are frequently replaced and priorities redefined, it may be difficult to devise policies consistent with a long-term approach. Stability of the state apparatus is a prerequisite for the credibility of the political process. Commitment is expressed when government explicitly includes the development of the workforce in its priorities and treats it as an essential public health function. It presupposes that government accepts the political risks of promoting changes likely to provoke the opposition of powerful interest groups. Benveniste [ 97 ] points out that change becomes possible only when a sufficient critical mass of stakeholders is convinced of its necessity and supports it. Mobilizing the ministries of health, education, finance and so on, and local governments, professional bodies and private organizations is not only a good strategy, but probably a necessary one [ 98 ]. Some interest groups such as doctors are particularly powerful, dominant and capable of mobilizing public opinion. Ignoring them is a recipe for failure. HR actions have more chance of being coherent if they are concerted, and of being implemented if they truly reflect the outcome of the political process, i.e. needs expressed, proposals made and compromises reached. The challenge is to identify all the key players and make their resources, interests and expectations explicit. Negotiating with them may pre-empt the development of an active and organized opposition to the proposed changes.

Social acceptability

New policies may hurt the expectations, preferences, beliefs or values of some stakeholders [ 99 ], such as when male personnel are used to deliver maternal and child care. Increasing the acceptability of reforms is possible, either by adapting the policies to the social and cultural environment, or by trying to change the latter through education or social marketing strategies, or, of course, by combining the two.

Affordability

The correction of imbalances in personnel may require substantial short-term financial commitments. Understaffing may require the opening of new training institutions or an increase of the intake of existing schools. Overstaffing may be addressed by offering financially attractive early retirement programmes. Geographical redeployment of personnel requires systems of incentives to attract workers to distant areas. Programmes for improving quality and performance require investment in infrastructure or equipment, or changes in working conditions (bonuses, salary increases, etc.). It is important, therefore, that HRH policy be based on an accurate assessment of its financial implications and of the capacity of the country to mobilize the necessary resources.

Conclusions

Attaining health objectives in a population depends to a large extent on the provision of effective, efficient, accessible, viable and high-quality services by personnel, present in sufficient numbers and appropriately allocated across different occupations and geographical regions. The lack of explicit policies for HRH development has produced, in most countries, imbalances that threaten the capacity of health care systems to attain their objectives. The workforce in the health sector has specific features that cannot be ignored. Health organizations are faced with external pressures that cannot be effectively met without appropriate adjustments to the workforce. The development of the workforce thus appears to be a crucial part of the health policy development process. Putting workforce problems on the political agenda and developing explicit HRH policies is a way to clarify objectives and priorities in this area, to rally all sectors concerned around these objectives, and to promote a more comprehensive and systematic approach to HRM. In the long term, this opens the prospect of developing health care systems more responsive to the expectations and needs of populations.

The World Bank: Financial impact of the HIPC Initiative: first 26 country cases. Washington, DC. 2002

Google Scholar

Decosas J: Planning for primary health care: the case of the Sierra Leone national action plan. Int J Health Plann Manage. 1990, 20 (1): 167-177.

CAS Google Scholar

Cassels A, K Janovsky K: Better health in developing countries: Are sector-wide approaches the way of the future?. Lancet North Am Ed. 1998, 35 (9142): 1777-1779.

Article Google Scholar

Walt G, Pavignani E, Gilson L, Buse K: Health sector development: from aid coordination to resource management. Health Policy Plan. 1999, 14: 207-218.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organization: World Health Report 2000. Health systems: improving performance. Geneva. 2000, [ http://www.who.int/m/topics/world_health_report/en/index.html ]

Cassels A: A guide to sector-wide approaches for health development. Genève, Organisation Mondiale de la Santé/DANIDA/DFID/Commission Européenne. 1997

Beaglehole R, Davis P: Setting national health goals and targets in the context of a fiscal crisis: the politics of social choice in New Zealand. Int J Health Serv. 1992, 22 (3): 417-428.

Peters BG: La capacité des pouvoirs publics d'élaborer des politiques. Centre canadien de gestion, Rapport de recherche No 18. 1996

Castley RJ: Policy-focused approach to manpower planning. Int J Manpower. 1996, 17 (3): 15-24.

Dussault G: Cadre pour l'analyse de la main-d'œuvre sanitaire. Ruptures Revue Transdisciplinaire Santé. 2001, 7 (2): 64-78.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): Development and strengthening of human resources management in the health sector. Washington DC, 128th Session of the Executive Committee. 2001

Buchan J: Health sector reform and human resources: lessons from the United Kingdom. Health Policy Plan. 2000, 15: 319-325.

Healy J, McKee M: Health sector reform in Central and Eastern Europe: the professional dimension. Health Policy Plan. 1997, 12 (4): 286-295.

Filmer D, Hammer JS, Pritchett LH: Weak links in the chain: a diagnosis of health policy in poor countries. World Bank Res Obs (Int). 2000, 15 (2): 199-224.

SARA: A public health workforce crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. An issues paper. Support for analysis and research in Africa (SARA). 2001

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): Human Resources: a critical factor in health sector reform. Report of a meeting in San José. Costa Rica, 3–5 December 1997. Washington DC. 1998

Bach S: Changing public service employment relations. In: Public Service Employment Relations in Europe, Transformation, Modernization and Inertia. Edited by: Bach S, Bordogna L, Della RG, Winchester D. 1999, London: Routledge

Buchan J, Seccombe I: The changing role of the NHS personnel function. In: Evaluating the NHS Reforms. Edited by: Legrand J, Robinson R. 1994, London: Kings Fund

Biscoe G: Human resources: the political and policy context. Human Resource Devel J. 2000, 4: 3-[ http://www.moph.go.th/ops/hrdj/ ]

Ozcan S, Taranto Y, Hornby P: Shaping the health future in Turkey – a new role for human resource planning. Int J Health Plann Manage. 1995, 10 (4): 305-319.

Adams OB, Hirschfeld M: Human resources for health – challenges for the 21st century. World Health Stat Q. 1998, 51 (1): 28-32.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Brito P, Galin P, Novick M: Labor relations, employment conditions and participation in health sector. Annecy, World Health Organization Workshop on Global Workforce Strategy. 2000, [ http://www.who.int/health-services-delivery/human/workforce/Documents.htm ]

Bach S: HR and new approaches to public sector management: improving HRM capacity. Annecy, World Health Organization Workshop on Global Workforce Strategy. 2000, [ http://www.who.int/health-services-delivery/human/workforce/Documents.htm ]

Dussault G: The nursing labour market in Canada: review of the literature. Cahiers du groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire en santé (research paper r01–03). University of Montréal. 2001

CESSSS (Commission d'Etude sur les services de santé et les services sociaux): Rapport et recommandations – Commission d'Etude sur les services de santé et les services sociaux – Les Solutions émergentes. Gouvernement du Québec. 2000, [ http://www.cessss.gouv.qc.ca/pdf/fr/00-109.pdf ]

Evans RG: Strained mercy: the economics of Canadian health care. Toronto: Butterworth & Co. 1984

Murray VV, Dimick DE: Contextual influences on personnel policies and programs: an explanatory model. Acad Manage Rev. 1978, 750-761.

Pfeffer J: The human equation: building profits by putting people first. Boston: Harvard University Press. 1998

Zairi M: Managing human resources in healthcare: learning from world class practices – part I. Health Manpow Manage. 1998, 24 (2): 88-99.

Koch MJ, McGraith RJ: Improving labor productivity: human resource management policies do matter. Strategic Manage J. 1996, 17: 335-354.

Eaton S: Beyond unloving care: linking human resource management and patient care quality in nursing homes. Int J Hum Resour Manage. 2000, 11 (3): 591-616.

Narine L: Impact of health system factors on changes in human resource and expenditures levels in OECD countries. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2000, 22 (3): 292-307.

International Labour Organisation: Terms of employment and working conditions in health sector reforms. Report for discussion at the Joint meeting on terms of employment and working conditions in health sector reforms. Geneva. 1998

Saltman RB, von Otter C: Implementing planned markets in health care: balancing social and economic responsibility. Ballmoor: Open University Press. 1995

Kolehamainen-Aiken RL: Decentralization and human resources: implications and impact. Human Resource Devel J. 1997, 2 (1): 1-14.