- Systematic review update

- Open access

- Published: 16 February 2024

The global economic burden of COVID-19 disease: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis

- Ahmad Faramarzi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5661-8991 1 ,

- Soheila Norouzi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3028-7861 1 ,

- Hossein Dehdarirad 2 ,

- Siamak Aghlmand 1 ,

- Hasan Yusefzadeh 1 &

- Javad Javan-Noughabi 3

Systematic Reviews volume 13 , Article number: 68 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1180 Accesses

Metrics details

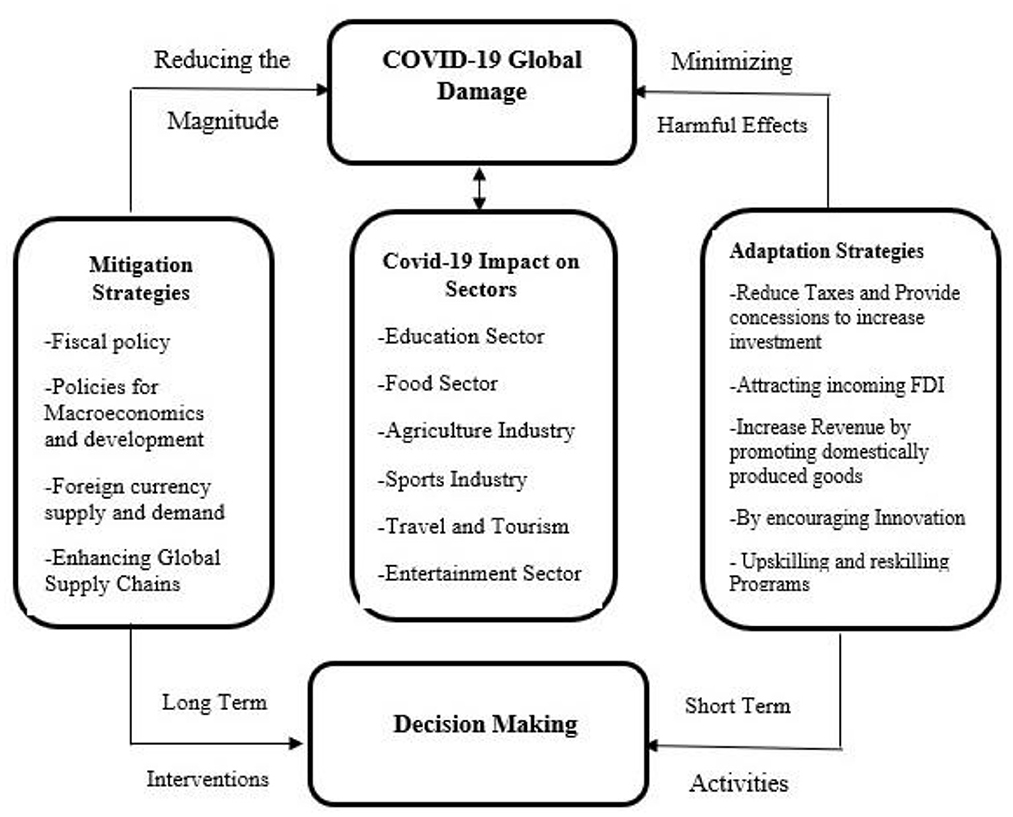

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a considerable threat to the economics of patients, health systems, and society.

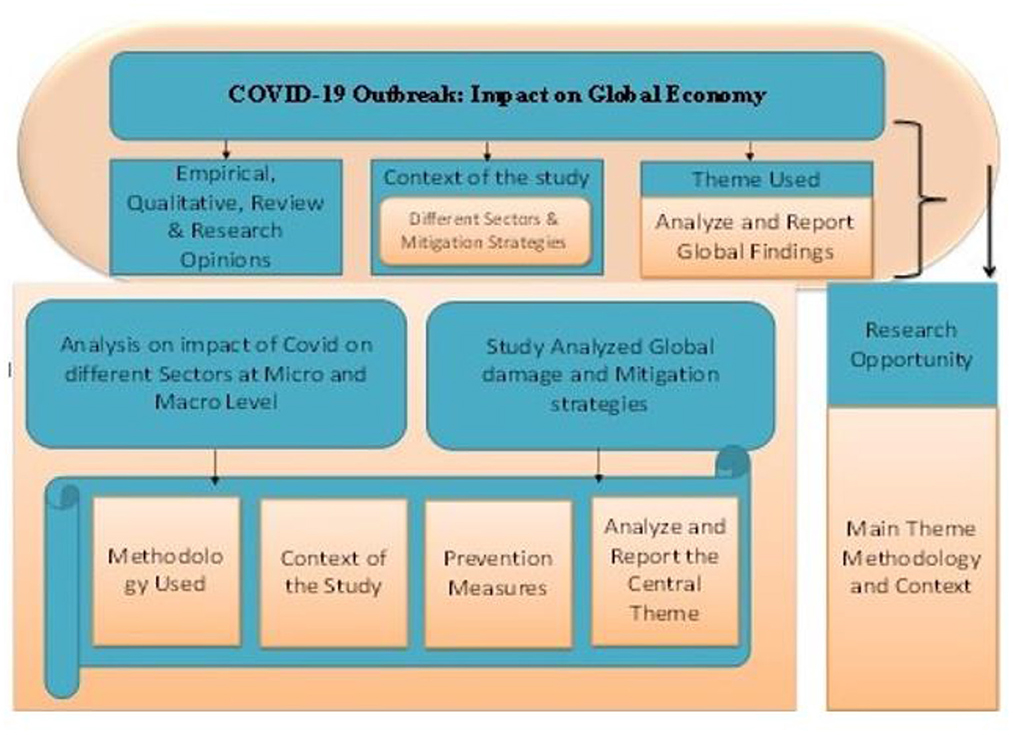

This meta-analysis aims to quantitatively assess the global economic burden of COVID-19.

A comprehensive search was performed in the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases to identify studies examining the economic impact of COVID-19. The selected studies were classified into two categories based on the cost-of-illness (COI) study approach: top-down and bottom-up studies. The results of top-down COI studies were presented by calculating the average costs as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) and health expenditures. Conversely, the findings of bottom-up studies were analyzed through meta-analysis using the standardized mean difference.

The implemented search strategy yielded 3271 records, of which 27 studies met the inclusion criteria, consisting of 7 top-down and 20 bottom-up studies. The included studies were conducted in various countries, including the USA (5), China (5), Spain (2), Brazil (2), South Korea (2), India (2), and one study each in Italy, South Africa, the Philippines, Greece, Iran, Kenya, Nigeria, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The results of the top-down studies indicated that indirect costs represent 10.53% of GDP, while the total estimated cost accounts for 85.91% of healthcare expenditures and 9.13% of GDP. In contrast, the bottom-up studies revealed that the average direct medical costs ranged from US $1264 to US $79,315. The meta-analysis demonstrated that the medical costs for COVID-19 patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) were approximately twice as high as those for patients in general wards, with a range from 0.05 to 3.48 times higher.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic has imposed a significant economic burden worldwide, with varying degrees of impact across countries. The findings of our study, along with those of other research, underscore the vital role of economic consequences in the post-COVID-19 era for communities and families. Therefore, policymakers and health administrators should prioritize economic programs and accord them heightened attention.

Peer Review reports

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a respiratory infection instigated by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2), first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. The disease has since proliferated globally at an alarming rate, prompting the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [ 1 ]. As of February 21, 2023, the global total of confirmed COVID-19 cases stands at 757,264,511, with a death toll of 6,850,594 [ 2 ].

Patients afflicted with COVID-19 exhibit a range of symptoms, including flu-like manifestations, acute respiratory failure, thromboembolic diseases, and organ dysfunction or failure [ 3 ]. Moreover, these patients have had to adapt to significant changes in their environment, such as relocating for quarantine purposes, remote work or job loss, and air-conditioning [ 4 , 5 ].

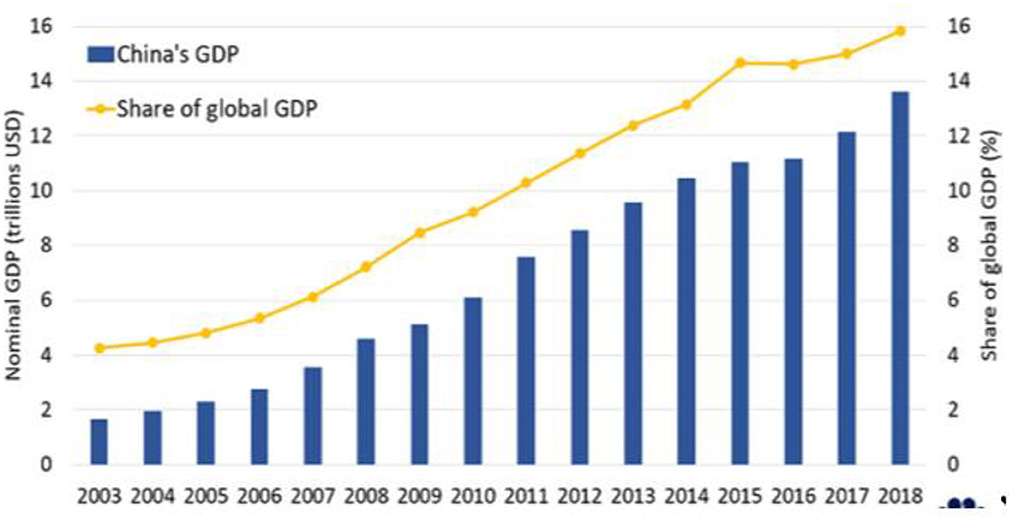

The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed substantial direct and indirect costs on patients, families, healthcare systems, and communities. These costs fluctuate significantly based on socioeconomic factors, age, disease severity, and comorbidities [ 6 , 7 ]. For instance, a study conducted in the United States of America (USA) estimated the median direct medical cost of a single symptomatic COVID-19 case to be US $3045 during the infection period alone [ 8 ]. Additionally, indirect costs arising from the pandemic, such as lost productivity due to morbidity and mortality, reduced consumer spending, and supply chain disruptions, could be substantial in certain countries [ 9 ]. Studies by Maltezou et al. and Faramarzi et al. revealed that absenteeism costs accounted for a large proportion (80.4%) of total costs [ 10 ] and estimated an average cost of US $671.4 per patient [ 11 ], respectively. Furthermore, the macroeconomic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is considerably more significant. Data from Europe indicates that the gross domestic product (GDP) fell by an average of 7.4% in 2020 [ 12 ]. Globally, the economic burden of COVID-19 was estimated to be between US $77 billion and US $2.7 trillion in 2019 [ 13 ]. Another study calculated the quarantine costs of COVID-19 to exceed 9% of the global GDP [ 14 ].

Evaluating the cost of COVID-19, encompassing both direct (medical and non-medical) and indirect costs, provides valuable insights for policymakers and healthcare managers to devise effective strategies for resource allocation and cost control, particularly in the post-COVID-19 era. Despite the abundance of literature on COVID-19, only a handful of studies have concentrated on its economic burden. Furthermore, the currency estimates provided in these articles is inconsistent. To address this gap, our study aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the global economic burden of COVID-19. The objectives of this study are twofold: firstly, to estimate the direct and indirect costs of COVID-19 as a percentage of GDP and health expenditure (HE) at the global level, and secondly, to estimate the direct medical costs based on the inpatient ward, which includes both the general ward and the intensive care unit (ICU).

This study was designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 15 ].

Search strategy and data sources

We performed a comprehensive search in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases to retrieve studies on the economic burden of COVID-19 disease. To this objective, we conducted a comprehensive search by combining the search terms relating to COVID-19 (coronavirus, 2019-nCoV), as a class, with the terms relating to the economic burden and terms related to it (direct cost, indirect cost, productivity cost, morbidity cost, mortality cost, cost analysis, cost of illness, economic cost, noneconomic cost, financial cost, expenditure, spending). The search was limited to English language publications and human studies that were published before September 19, 2021. The search strategy was validated by a medical information specialist. All search strategies are available in the Additional file 1 .

Screening and selection

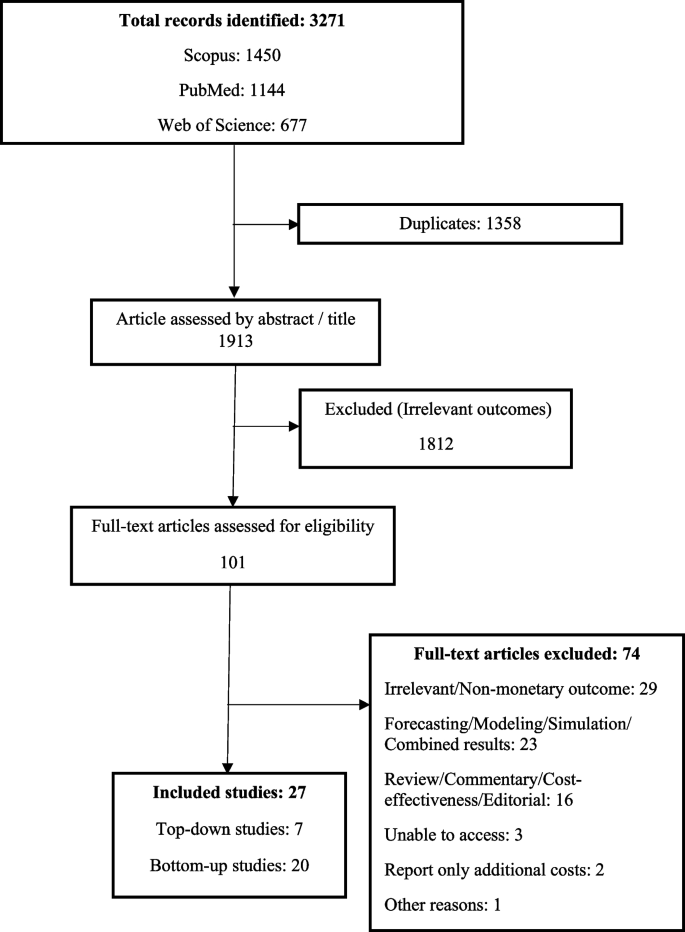

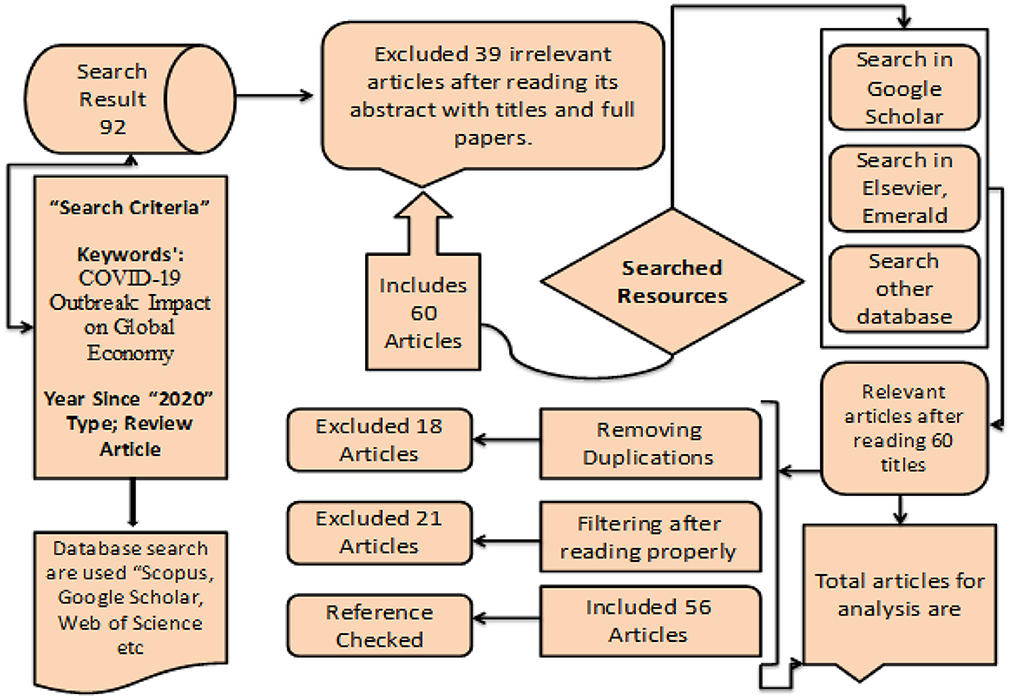

Two reviewers independently screened all distinct articles, focusing on the title and abstract and utilizing EndNote software. The reviewers were blinded to each other’s findings during the screening phase. Potential duplicates were identified and scrutinized to exclude identical entries. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were reconciled through consensus or by consulting a third reviewer. The final decision regarding inclusion was determined subsequent to a comprehensive review of the full-text article. The whole process of the study selection was outlined in a flow chart (Fig. 1 ).

Flowchart depicting the selection of research studies

This systematic review included all original studies that addressed the economic burden of COVID-19, provided they (1) estimated all costs associated with COVID-19, including both direct (medical and non-medical) and indirect (morbidity and mortality) costs and (2) were designed as observational studies or controlled clinical trials. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) they were review articles, commentaries, editorials, protocols, case studies, case series, animal studies, book chapters, or theses, (2) they estimated costs for a specific disease or action during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (3) they were studies assessing budget impact or economic evaluations.

Data extraction

A specific data extraction template was developed to extract relevant information from every study that satisfied our eligibility criteria. The data extracted covered the general study characteristics (authors, study publication, geographical location of data collection), cost-related information (direct medical cost, direct nonmedical cost, indirect cost, total cost, years of costing, and currency), and participants-related data (sample size and population studied for estimation).

Outcome and quality assessment

The primary outcomes were documented as the standardized mean difference (SMD) accompanied by 95% confidence intervals, representing the direct medical costs borne in general wards as compared to ICU for patients diagnosed with COVID-19. Additionally, another outcome was the estimation of these costs as a proportion of the GDP and health expenditure (HE).

A quality assessment was conducted on all the included studies, utilizing the checklist formulated by Larg and Moss [ 16 ]. This checklist comprises three domains: analytic framework, methodology and data, and analysis and reporting. The quality assessment was independently corroborated by two reviewers. In case of any discrepancies in the quality assessment, resolution was ensured through consensus or consultation with a third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

To analyze the data, we utilized the cost-of-illness (COI) study approach, which involved categorizing the studies into two groups: top-down studies and bottom-up studies. Top-down studies were defined as population-based methods that estimated costs for a specific country or group of countries, while bottom-up studies were defined as person methods that estimated costs per person [ 16 ].

In our methodological approach to the top-down studies, we initially categorized the costs into direct and indirect types. The direct costs comprised both medical and nonmedical expenses, while the indirect costs were related to potential productivity losses stemming from mortality and morbidity. Subsequently, we undertook the adjustment of all costs to the 2020 US dollar value. This was achieved based on the principle of purchasing power parity (PPP), and we utilized the currency conversion factor as recommended by the World Bank for this purpose. We employed the method proposed by Konnopka and König to present the COVID-19 cost to top-down studies. This method, which expresses the costs as a proportion of the gross domestic product (GDP) and health expenditure (HE), eliminates the need for adjustments for inflation or differences in purchasing power [ 17 ]. Moreover, we computed the costs using both an unweighted mean and a population-weighted mean.

In the bottom-up studies, a random-effects model was employed for the meta-analysis, with the SMD serving as the measure of effect size. To mitigate the influence of heterogeneity, all costs were converted to 2020 US dollars based on PPP, utilizing the currency conversion factor suggested by the World Bank. The focus of our analysis was a comparison of the direct medical costs of patients admitted to the general ward versus those in ICU. The SMD was calculated as the measure of effect size, with the sample size acting as the weighting factor. Heterogeneity was assessed through Cochran’s Q test and the I 2 statistic. The Q -test, a classical measure with a chi-square distribution, is calculated as the weighted sum of squared differences between individual study effects and the pooled effects across studies. The I 2 statistic represents the percentage of variation across studies, with threshold values of 25%, 50%, and 75% indicating low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively. To assess possible publication or disclosure bias, we used funnel plots, the Begg-adjusted rank correlation test, and Egger’s test. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA), and P -values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1 . The search strategy produced 3271 records (Scopus, 1450; PubMed, 1144; Web of Science, 677), from which 1358 duplicates were eliminated. Out of the remaining 1913 articles, a mere 101 satisfied the inclusion criteria and underwent a full-text review. During this full-text screening, 74 articles were excluded for various reasons, resulting in a final selection of 27 studies included in the systematic review. Among these, 20 were bottom-up studies [ 7 , 10 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ], and 7 were top-down studies [ 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ].

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the included studies. Out of the 27 studies, 5 were conducted in the USA; 5 in China; 2 each in Spain, Brazil, South Korea, and India; and 1 each in Italy, South Africa, the Philippines, Greece, Iran, Kenya, Nigeria, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Based on the methodology employed, 20 studies were categorized as bottom-up studies and seven as top-down studies.

Among the seven top-down studies, only three calculated direct medical costs [ 37 , 38 , 41 ], two studies examined the direct nonmedical costs [ 38 , 41 ], and all but Santos et al. [ 37 ], who did not report these costs, calculated indirect costs. Of the 20 bottom-up studies, all but 1 study [ 31 ] assessed the direct medical costs. Only four studies calculated the direct nonmedical costs [ 10 , 19 , 29 , 34 ], and seven studies reported the indirect costs [ 7 , 10 , 19 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 34 ].

Table 2 presents the specific characteristics of the top-down studies. These studies indicate that the direct costs of COVID-19 span from US $860 million to US $8,657 million, while indirect costs range from US $610 million to US $5,500,000 million. On average, top-down studies estimate the direct costs associated with COVID-19 to constitute 2.73% and 0.39% of healthcare expenditures, based on unweighted and weighted means, respectively. The results also reveal that, on average, indirect costs account for 10.53% of GDP, with a range of 0.02 to 30.90%. Furthermore, the total cost estimated by top-down studies comprises 85.91% of healthcare expenditure and 9.13% of GDP.

Table 3 outlines the specific characteristics of the bottom-up studies. Excluding two studies [ 23 , 27 ], all reported their sample sizes, which varied from 9 to 1,470,721. The mean estimate of direct medical costs ranged from US $1264 to US $79,315. Two studies reported values for direct nonmedical costs [ 19 , 29 ], with means of US $25 and US $71. The mean estimate of indirect costs ranged from US $187 to US $689,556.

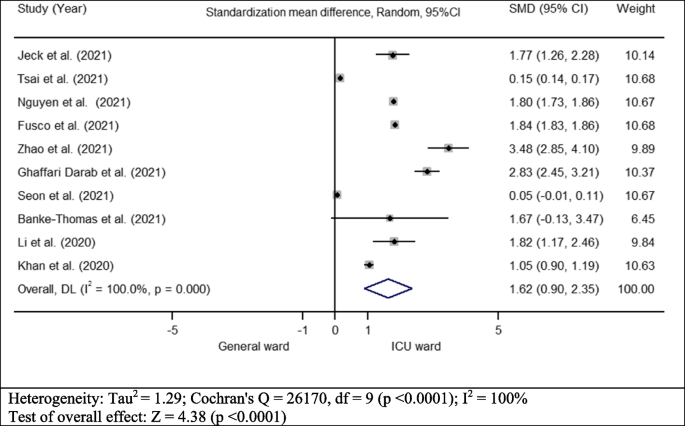

Meta-analysis results

The results of the meta-analysis for the direct medical costs are shown in Figure 2 . The results indicate a significant association between the mean cost of direct medical services and the inpatient ward. Specifically, the analysis yielded a standardized mean difference (SMD) of 1.62 ( CI : 0.9–2.35) with a substantial degree of heterogeneity ( Q = 26170, p < 0.0001; I 2 = 100%).

Mean direct medical cost for patient with COVID-19 based on disease severity

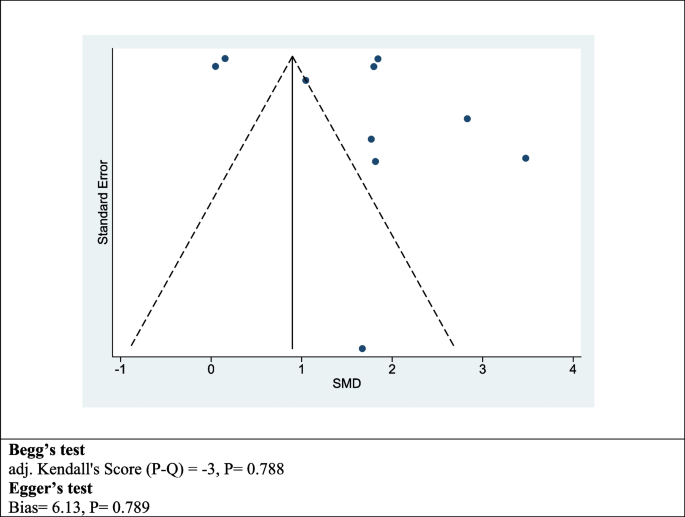

Assessment of publication bias

Figure 3 presents the information related to publication bias. The funnel plot, constructed from the studies included, does not suggest the presence of potential publication bias. Moreover, the application of Begg’s and Egger’s tests in the statistical analysis resulted in P-values of 0.788 and 0.789, respectively, indicating an absence of significant bias.

The funnel plots, Begg’s test, and Egger’s test to assessment of publication bias for included studies that assessed the direct medical costs of patients hospitalized in the general ward versus those in the intensive care unit (ICU)

This investigation represents the initial systematic review and meta-analysis conducted on the topic of the global economic impact of COVID-19. Furthermore, it is the first study to evaluate economic burden research related to COVID-19 using both top-down and bottom-up approaches, and it has conducted a meta-analysis of medical direct expenses based on hospitalization wards. In general, studies examining the economic impact of COVID-19 are scarce, with a greater proportion of studies employing a bottom-up approach. More than 30% of these studies were conducted in the USA and China. Patients admitted to the ICU ward exhibited higher costs than those admitted to the general ward.

Admission to the ICU significantly escalated the medical expenditure associated with COVID-19 treatment. This study discovered that the medical costs for COVID-19 patients in the ICU were approximately twice as high as those for patients in general wards, with a range from 0.05 to 3.48 times higher. This finding aligns with existing literature, which suggests that ICU patients with COVID-19 are more likely to require expensive treatments such as mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, compared to those in general wards [ 44 , 45 ]. Consistent with this, other studies have reported an increase in medical expenditures with the hospitalization of COVID-19 patients in the ICU. For instance, a study conducted in the USA found a fivefold increase in costs for patients in the ICU who required invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), compared to those not in the ICU or without IMV [ 22 ]. Similarly, a study in China reported a 2.5-fold increase in costs for severe COVID-19 patients compared to mild cases [ 30 ]. Given the elevated medical costs associated with treating COVID-19 patients in the ICU or those with severe symptoms, health policymakers must concentrate on implementing programs that promote early diagnosis. Consequently, healthcare providers could initiate treatment at an earlier stage, potentially reducing the severity of the disease and associated costs.

Our research indicates that significant variations in estimated costs would be observed if these costs were reported in PPP, particularly in relation to direct medical expenses. The lowest value was calculated in India, amounting to US $1264, while the highest value was observed in the USA, reaching US $54,165. Furthermore, the calculated medical costs varied across countries. For example, in the USA, direct medical expenditures ranged from US $1701 to US $54,156 [ 21 , 35 ]. In contrast, in China, the reported costs fluctuated between US $5264 and US $79,315 [ 7 , 25 ]. Several factors contribute to this variation in the estimation of direct medical costs. Primarily, direct medical costs cover a spectrum of services, including diagnosis, medication, consumables, inpatient care, and consultation services. Consequently, each study may have estimated the direct medical costs for a subset or the entirety of these services, leading to differences in the estimated costs. For instance, Nguyen et al. demonstrated a nearly threefold increase in direct costs for COVID-19 patients managed with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) compared to patients not receiving ECMO [ 35 ]. This highlights the impact of specific treatments on the overall cost. Secondly, the sample size may vary between studies, resulting in different cost estimates. Larger sample sizes typically provide more accurate and reliable estimates, but they also require more resources to collect and analyze. Lastly, the studies may have estimated costs for patients with varying conditions, such as those in acute status, patients hospitalized in general wards, or those admitted to ICU wards.

In addition to direct medical expenditures, the indirect costs arising from productivity losses due to COVID-19 have substantial societal implications. This study discovered that direct medical expenses attributable to COVID-19 varied from US $860 million (representing 0.11% of China’s healthcare expenditure) as reported by Zhao et al. [ 38 ] in China to US $8657 million (equivalent to 7.4% of Spanish healthcare expenditure) as reported by Gonzalez Lopez et al. [ 41 ] in Spain. On a global scale, direct medical costs due to COVID-19 constituted 2.73% of healthcare expenditure and 0.25% of GDP. The results also unveiled that the indirect costs of the COVID-19 pandemic impacted different countries to varying extents. The minimum value of indirect costs was estimated in Italy [ 40 ] and India [ 39 ] at US $610 million and US $658 million, respectively. Interestingly, when reported as a percentage of GDP, India had a lower cost (0.02% of GDP) compared to China (0.03% of GDP). The maximum value of indirect costs was calculated in the USA at US $5,500,000 million, which accounted for approximately 26.32% of the USA’s GDP [ 36 ]. Despite the numerical value of indirect costs being lower in Spain than in the USA and China, it represented a higher percentage of GDP (30.90%). The resulting pooled estimate indicated that the indirect costs due to COVID-19 were responsible for 10.53% of global GDP. The review underscores the significant economic repercussions of COVID-19. The total costs in the USA accounted for about 157% of healthcare expenditure and 26% of GDP, in China for 80% of healthcare expenditure and 4.28% of GDP, and in Spain for approximately 345% of healthcare expenditure and 32% of GDP. Globally, the total costs of COVID-19 accounted for about 86% of healthcare expenditure and 9.13% of GDP. This highlights the profound economic impact of the pandemic on both healthcare systems and economies worldwide.

Strengths and limitation

Our study possesses several significant strengths. It is the inaugural meta-analysis of the worldwide costs associated with COVID-19, supplementing a systematic review conducted by Richards et al. on the economic burden studies of COVID-19 [ 12 ]. A considerable number of studies was conducted in the USA and China, but our analysis also incorporated studies from other high- and low-income countries, potentially enhancing the generalizability of our findings. Recognizing that economic burden studies often display significant heterogeneity, we endeavored to minimize this by distinguishing between bottom-up and top-down studies and standardizing currencies to US dollars in terms of PPP.

However, our study is not without limitations. As is typical with all meta-analyses of economic burden studies, the most substantial limitation is heterogeneity. This heterogeneity can originate from various factors, including differences in study design, the range of services included in individual studies, the year of estimation, the currencies used for estimation, the study population, among other factors. Our systematic review only incorporated studies that estimated costs for an actual population, thereby excluding a wide array of studies on the economic burden of COVID-19 that employed modeling techniques. Future research could potentially conduct systematic reviews and meta-analyses on cost estimation modeling studies for COVID-19. Lastly, while no publication bias was detected through statistical analysis, our study was limited to papers written in English. As a result, numerous papers published in other languages were inevitably excluded.

Our research indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic has imposed a substantial economic strain worldwide, with the degree of impact varying across nations. The quantity of studies examining the economic repercussions of COVID-19 is limited, with a majority employing a bottom-up methodology. The indirect costs ascribed to COVID-19 constituted 10.53% of the global GDP. In total, the costs linked to COVID-19 represented 9.13% of GDP and 86% of healthcare spending. Moreover, our meta-analysis disclosed that the direct medical expenses for COVID-19 patients in the ICU were almost twice those of patients in general wards. The results of our research, along with those of others, underscore the pivotal role of economic outcomes in the post-COVID-19 era for societies and families. Consequently, it is imperative for policymakers and health administrators to prioritize and pay greater attention to economic programs.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated during the study. The data analysis file during this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):401–2.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 .

Gautier JF, Ravussin Y. A new symptom of COVID-19: loss of taste and smell. Obesity. 2020;28(5):848.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Delikhoon M, Guzman MI, Nabizadeh R, Norouzian BA. Modes of transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and factors influencing on the airborne transmission: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):395.

Alimohammadi M, Abolli S, Ghordouei ME. Perceiving effect of environmental factors on prevalence of SARS-Cov-2 virus and using health strategies: a review. J Adv Environ Health Res. 2022;10(3):187–96.

Article Google Scholar

Li XZ, Jin F, Zhang JG, Deng YF, Shu W, Qin JM, et al. Treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 in Shandong, China: a cost and affordability analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):78.

Jin H, Wang H, Li X, Zheng W, Ye S, Zhang S, et al. Economic burden of COVID-19, China, January–March, 2020: a cost-of-illness study. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(2):112.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bartsch SM, Ferguson MC, McKinnell JA, O'Shea KJ, Wedlock PT, Siegmund SS, et al. The potential health care costs and resource use associated with COVID-19 in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(6):927–35.

Juranek S, Paetzold J, Winner H, Zoutman F. Labor market effects of COVID-19 in Sweden and its neighbors: evidence from novel administrative data. NHH Dept of Business and Management Science Discussion Paper. (2020/8); 2020.

Google Scholar

Maltezou H, Giannouchos T, Pavli A, Tsonou P, Dedoukou X, Tseroni M, et al. Costs associated with COVID-19 in healthcare personnel in Greece: a cost-of-illness analysis. J Hosp Infect. 2021;114:126–33.

Faramarzi A, Javan-Noughabi J, Tabatabaee SS, Najafpoor AA, Rezapour A. The lost productivity cost of absenteeism due to COVID-19 in health care workers in Iran: a case study in the hospitals of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1169.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Richards F, Kodjamanova P, Chen X, Li N, Atanasov P, Bennetts L, et al. Economic burden of COVID-19: a systematic review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2022;14:293–307.

Forsythe S, Cohen J, Neumann P, Bertozzi SM, Kinghorn A. The economic and public health imperatives around making potential coronavirus disease–2019 treatments available and affordable. Value Health. 2020;23(11):1427–31.

Rodela TT, Tasnim S, Mazumder H, Faizah F, Sultana A, Hossain MM. Economic impacts of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in developing countries; 2020.

Book Google Scholar

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group* t. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Larg A, Moss JR. Cost-of-illness studies: a guide to critical evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29:653–71.

Konnopka A, König H. Economic burden of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38:25–37.

Jeck J, Jakobs F, Kron A, Franz J, Cornely OA, Kron F. A cost of illness study of COVID-19 patients and retrospective modelling of potential cost savings when administering remdesivir during the pandemic “first wave” in a German tertiary care hospital. Infection. 2022;50(1):191–201.

Kotwani P, Patwardhan V, Pandya A, Saha S, Patel GM, Jaiswal S, et al. Valuing out-of-pocket expenditure and health related quality of life of COVID-19 patients from Gujarat, India. J Commun Dis (E-ISSN: 2581-351X & P-ISSN: 0019-5138). 2021;53(1):104–9.

Tsai Y, Vogt TM, Zhou F. Patient characteristics and costs associated with COVID-19–related medical care among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(8):1101–9.

Weiner JP, Bandeian S, Hatef E, Lans D, Liu A, Lemke KW. In-person and telehealth ambulatory contacts and costs in a large US insured cohort before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e212618-e.

Di Fusco M, Shea KM, Lin J, Nguyen JL, Angulo FJ, Benigno M, et al. Health outcomes and economic burden of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2021;24(1):308–17.

Edoka I, Fraser H, Jamieson L, Meyer-Rath G, Mdewa W. Inpatient care costs of COVID-19 in South Africa’s public healthcare system. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(8):1354.

PubMed Google Scholar

Tabuñar SM, Dominado TM. Hospitalization expenditure of COVID-19 patients at the university of the Philippines-Philippine general hospital (UP-PGH) with PhilHealth coverage. Acta Med Philipp. 2021;55(2)

Zhao J, Yao Y, Lai S, Zhou X. Clinical immunity and medical cost of COVID-19 patients under grey relational mathematical model. Results Phys. 2021;22:103829.

Ghaffari Darab M, Keshavarz K, Sadeghi E, Shahmohamadi J, Kavosi Z. The economic burden of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence from Iran. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–7.

Barasa E, Kairu A, Maritim M, Were V, Akech S, Mwangangi M. Examining unit costs for COVID-19 case management in Kenya. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(4):e004159.

Seon J-Y, Jeon W-H, Bae S-C, Eun B-L, Choung J-T, Oh I-H. Characteristics in pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(20):e148.

Banke-Thomas A, Makwe CC, Balogun M, Afolabi BB, Alex-Nwangwu TA, Ameh CA. Utilization cost of maternity services for childbirth among pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019 in Nigeria’s epicenter. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;152(2):242–8.

Li X-Z, Jin F, Zhang J-G, Deng Y-F, Shu W, Qin J-M, et al. Treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 in Shandong, China: a cost and affordability analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(03):31–8.

CAS Google Scholar

Kirigia JM, Muthuri RNDK. The fiscal value of human lives lost from coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in China. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13:1–5.

Lee JK, Kwak BO, Choi JH, Choi EH, Kim J-H, Kim DH. Financial burden of hospitalization of children with coronavirus disease 2019 under the national health insurance service in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(24):e224.

Khan AA, AlRuthia Y, Balkhi B, Alghadeer SM, Temsah M-H, Althunayyan SM, et al. Survival and estimation of direct medical costs of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7458.

Mas Romero M, Avendaño Céspedes A, Tabernero Sahuquillo MT, Cortés Zamora EB, Gómez Ballesteros C, Sánchez-Flor Alfaro V, et al. COVID-19 outbreak in long-term care facilities from Spain. Many lessons to learn. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0241030.

Nguyen NT, Sullivan B, Sagebin F, Hohmann SF, Amin A, Nahmias J. Analysis of COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome managed with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation at US academic centers. Ann Surg. 2021;274(1):40.

Viscusi WK. Economic lessons for COVID-19 pandemic policies. South Econ J. 2021;87(4):1064–89.

Santos HLPC, Maciel FBM, Santos Junior GM, Martins PC, Prado NMBL. Public expenditure on hospitalizations for COVID-19 treatment in 2020, in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2021;55:52.

Zhao J, Jin H, Li X, Jia J, Zhang C, Zhao H, et al. Disease burden attributable to the first wave of COVID-19 in China and the effect of timing on the cost-effectiveness of movement restriction policies. Value Health. 2021;24(5):615–24.

John D, Narassima M, Menon J, Rajesh JG, Banerjee A. Estimation of the economic burden of COVID-19 using disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and productivity losses in Kerala, India: a model-based analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e049619.

Nurchis MC, Pascucci D, Sapienza M, Villani L, D’Ambrosio F, Castrini F, et al. Impact of the burden of COVID-19 in Italy: results of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and productivity loss. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4233.

González López-Valcárcel B, Vallejo-Torres L. The costs of COVID-19 and the cost-effectiveness of testing. Appl Econ Anal. 2021;29(85):77–89.

Debone D, Da Costa MV, Miraglia SG. 90 days of COVID-19 social distancing and its impacts on air quality and health in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Sustainability. 2020;12(18):7440.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ghaffari Darab M, Keshavarz K, Sadeghi E, Shahmohamadi J, Kavosi Z. The economic burden of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence from Iran. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):132.

Oliveira TF, Rocha CAO, Santos AGG, Silva Junior LCF, Aquino SHS, Cunha EJO, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in COVID-19 treatment: a systematic literature review. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;36:388–96.

Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, Rajagopalan H, O’Donnell L, Chernyak Y, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966.

Download references

There was no funding utilized in this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Economics and Management, School of Public Health, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran

Ahmad Faramarzi, Soheila Norouzi, Siamak Aghlmand & Hasan Yusefzadeh

Department of Medical Library and Information Science, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Hossein Dehdarirad

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

Javad Javan-Noughabi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AF was principal investigators of designing the study, conducted analysis, and was major contributor in writing the manuscript. SN, HD, and SA conducted the literature search, conducted the screening and data extraction. HY and JJ contributed in designing the study and writing the manuscript. All authors contributed, reviewed, and approved this paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ahmad Faramarzi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Urmia University of Medical Sciences (IR.UMSU.REC.1400.121).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1..

Search strategies

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Faramarzi, A., Norouzi, S., Dehdarirad, H. et al. The global economic burden of COVID-19 disease: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 13 , 68 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02476-6

Download citation

Received : 13 August 2023

Accepted : 31 January 2024

Published : 16 February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02476-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cost of illness

- Systematic review

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Effects of COVID-19 on trade flows: Measuring their impact through government policy responses

Contributed equally to this work with: Javier Barbero, Juan José de Lucio, Ernesto Rodríguez-Crespo

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Commission, Seville, Andalucía, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Economic Structure and Development Economics, Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain

Affiliation Department of Economic Structure and Development Economics, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

- Javier Barbero,

- Juan José de Lucio,

- Ernesto Rodríguez-Crespo

- Published: October 13, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258356

- Peer Review

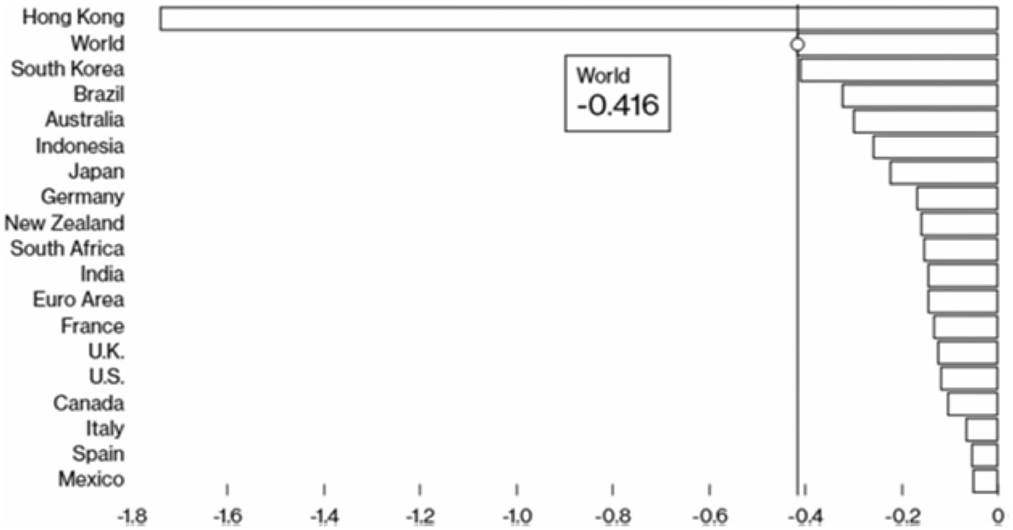

- Reader Comments

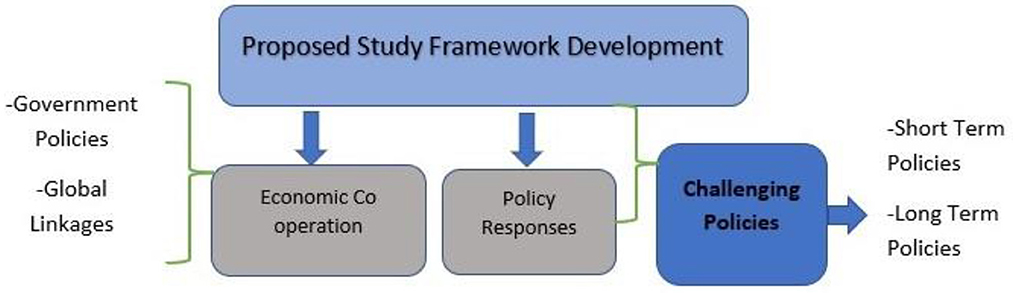

This paper examines the impact of COVID-19 on bilateral trade flows using a state-of-the-art gravity model of trade. Using the monthly trade data of 68 countries exporting across 222 destinations between January 2019 and October 2020, our results are threefold. First, we find a greater negative impact of COVID-19 on bilateral trade for those countries that were members of regional trade agreements before the pandemic. Second, we find that the impact of COVID-19 is negative and significant when we consider indicators related to governmental actions. Finally, this negative effect is more intense when exporter and importer country share identical income levels. In the latter case, the highest negative impact is found for exports between high-income countries.

Citation: Barbero J, de Lucio JJ, Rodríguez-Crespo E (2021) Effects of COVID-19 on trade flows: Measuring their impact through government policy responses. PLoS ONE 16(10): e0258356. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258356

Editor: Stefan Cristian Gherghina, The Bucharest University of Economic Studies, ROMANIA

Received: April 12, 2021; Accepted: September 26, 2021; Published: October 13, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Barbero et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the results presented in the study are available from UN Comtrade ( https://comtrade.un.org ), the Centre d'Études Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales (CEPII) Gravity database ( http://www.cepii.fr/cepii/en/bdd_modele/presentation.asp?id=8 ) and from Our World in Data COVID-19 Git Hub repository ( https://github.com/owid/covid-19-data/tree/master/public/data ). The three datasets are publicly available for all researchers. Merging the three datasets and following the steps described in the “Model description and estimation strategy” section readers can replicate the results of this manuscript.

Funding: de Lucio and Rodríguez-Crespo thank financial support from Universidad de Alcalá de Henares (UAH) and Banco Santander through research project COVID-19 UAH 2019/00003/016/001/007. De Lucio also thanks financial support from Comunidad de Madrid and UAH (ref: EPU-INV/2020/006 and H2019/HUM5761).

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

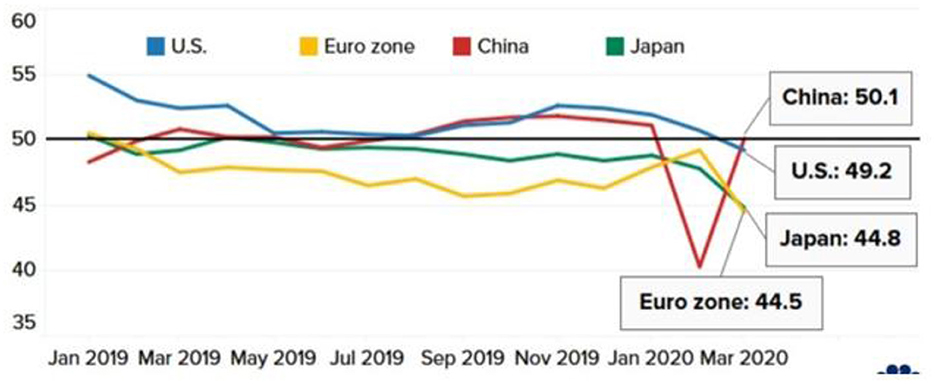

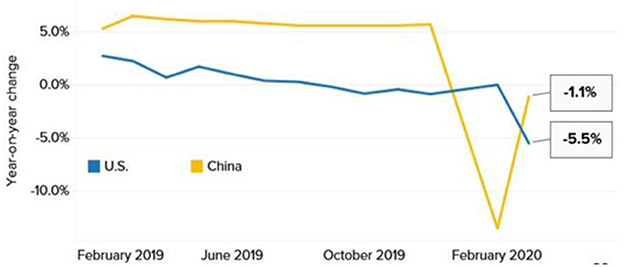

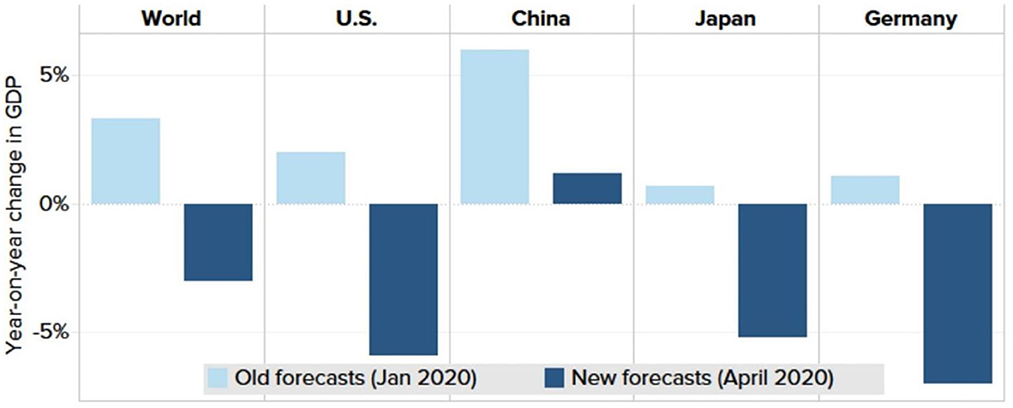

The world is facing an unexpected recession due to the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic in the global economy. In parallel with the consequences of the 2008–2009 crisis, international trade has once again collapsed. World trade volumes decreased by 21% between March and April 2020, while during the previous crisis the highest monthly drop was 18%, between September and October 2008. Cumulative export growth rate for the period December 2019– March 2020 was -7%, while for the period July 2008 –February 2009 it was -0,8%. The 2020 downturn was less prolonged than that caused by the latter crisis. Trade volumes in August 2020 only showed a 3% decrease compared to March 2020. The World Trade Organization (WTO) estimated that international merchandise trade volumes fell by 9.2% in 2020, a figure similar in magnitude to the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, although factors such as the economic context, the origins of the crisis and the transmission channels are deemed to be very distinct from the previous crisis [ 1 ].

Due to its rapid propagation, a proper evaluation of the economic impacts of COVID-19 crisis is not only desirable but challenging if the aim is to mitigate uncertainty [ 2 ]. The COVID-19 crisis has its origins in the policy measures adopted to combat the health crisis, while the 2008–2009 crisis had economic roots contingent on financially related issues. At the current time, the collapse of international trade has been driven by the voluntary and mandatory confinement measures imposed on world trade. We aim to analyse the impact of said confinement measures on trade. Estimating COVID-19 impacts on trade would shed light on the cost of confinement measures and the evolution and forecast of bilateral trade.

From an empirical point of view, we resort to [ 3 ], who use quarterly data for the period 2003–2005 in order to analyse the impact of the SARS epidemic on firms. They show that regions with higher transmission of SARS experienced lower import and export growth compared to those in the unaffected regions. The propagation of a virus resembles natural disasters, with both interpreted as external non-economic based shocks, the effects of which have been addressed already in the literature (e.g., [ 4 – 9 ]).

Another strand of the literature directly analyses the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on global trade in terms of the transmission mechanism of the shock: demand, supply and global supply chains. Some authors argue that demand factors have played an important role in explaining the shock [ 10 , 11 ] conclude that both shocks (demand and supply) are present in the crisis [ 1 ] highlight the role of global value chains in the transmission of shocks [ 12 ] focus on supply chain disruptions and reveal that those sectors with large exposure to intermediate goods imports from China contracted more than other sectors [ 13 ]. Focus on the role of global supply chains on the GDP growth for 64 countries during the COVID-19 pandemic and show that one quarter of the total downturn is due to global supply chains transmission. They also conclude that in general global supply chains, make countries more resilient to pandemic-induced contractions in labour supply. Finally, the collapse in trade can also be considered as a trade-induced effect caused by economic recessions (e.g., [ 14 – 16 ]) and may also be associated with the impact of COVID-19.

During the current wave of globalization, time lags in synchronizing business cycles between countries are reduced significantly in terms of the intensity of trade relationships [ 17 ]. Find that business cycle synchronization increases when countries trade more with each other [ 18 ]. Show that bilateral trade intensity has a sizeable positive, statistically significant, and robust impact on synchronization. These results are in line with [ 19 ], who finds that greater trade intensity increases business cycle synchronization, especially in country pairs with a free trade agreement and among industrial country pairs. Our paper provides prima facie evidence that this relationship also holds during pandemic-related trade shocks.

We contribute to the literature by integrating monthly data for a trade analysis of 68 countries, 31 of which are classified as high-income. We additionally focus on differential effects between high-income and low- and middle-income countries. This paper aims to shed light on the impact of COVID-19 on exports by means of an integrated approach for a significant number of countries, thereby avoiding an individual analysis of a single country or region that could potentially be affected by idiosyncratic shocks. Given the existence of substantial differences in trade performance and containment measures exhibited by countries and trade partners and attributable in part to their income, we also study whether the impact of COVID-19 on trade differs in terms of income levels. To the best of our knowledge, both questions, the integrated impact of confinement measures and the income related effects, remain unexplored in previous studies.

A proper analysis of ex-post trade impacts related to COVID-19 requires a suitable and fruitful methodology. Gravity models can be helpful in achieving this goal, since they have recently started to incorporate monthly trade data into the analyses, albeit with empirical evidence that is still scarce and far from conclusive [ 8 , 20 , 21 ]. At the same time, several methodological issues need to be resolved adequately when using gravity models [ 22 ]. Resorting to monthly data may pose several advantages in terms of accomplishing our research goals and exploiting the explanatory power exhibited by gravity models and monthly country confinement measures. First, the data reflect monthly variations and allow us to better capture any differential effects arising across countries. Second, annual trade data do not capture the short-run impact of shocks that occur very rapidly, something which a monthly time span can achieve. Monthly data can pick up any rapid movements associated with COVID-19 measures and allow for differential shocks in relation to months and countries. This is particularly relevant given the growing importance of nowcasting and short-term analysis techniques required nowadays for an understanding of world economy dynamics. Finally, monthly data can explain the relative importance of demand and supply shocks during the course of the trade crisis.

We collect monthly trade data for 68 countries ( S1 Table ), which exported to 222 destinations between January 2019 and October 2020. Using state-of-the-art estimation techniques for trade-related gravity models, our results are threefold. First, we reveal a negative impact of COVID-19 on trade that holds across specifications. Second, we obtain results that do not vary substantially when considering different governmental measures. Finally, our results show that the greatest negative COVID-19 impact occurs for exports within groups (high-income countries and low-middle-income countries), but not between groups. These findings are robust to different tests resulting from the introduction of lagging explanatory variables, alternative trade flows (exports vs imports as the dependent variable) or COVID-19 impact measures (independent variables such as stringency index or the number of reported deaths per million population).

Literature review on COVID-19 and trade

The specific literature covering the COVID-19 induced effects on trade can be catalogued as flourishing and burgeoning, but also as incipient and inconclusive at the current time. Some studies have addressed the impact of the health-related crisis on trade. The first strand of literature analyses the effects of previous pandemics by emphasizing asymmetric impacts across sectors. Using the quarterly transaction-level trade data of all Chinese firms in 2003 [ 3 ], estimate the effects of the first SARS pandemic on trade in that year. They find that (i) Chinese regions with a local transmission of SARS experienced a lower decline in trade margins, and (ii) the trade of more skilled and capital-intensive products was less affected by the pandemic.

Despite data being scarce, other studies focus on the current COVID-19 trade shock but are usually restricted to specific countries. For the case of Switzerland [ 23 ], combine weekly and monthly trade data, for the lockdown between mid-March and the end of July. They use goods information disaggregated by product and trade partner. They find that: (i) During lockdown Swiss trade fell 11% compared to the same period of 2019, and this trade shock proved more profound than the previous trade shock in 2009, (ii) contraction in Swiss exports seems to be correlated with the number of COVID-19 cases in importing countries, but at the same time, Swiss imports are related to the stringency of government measures in the exporter country (iii) for the case of products, only pharmaceutical and chemical products remained resilient to the trade shock and (iv) the pandemic negatively affected the demand and supply sides of foreign trade [ 24 ]. Use a gravity model and focus on exports from China for the period January 2019 to December 2020. They find a negative effect of COVID-19 on trade, but said effect is largely attenuated for medical goods and products that entail working from home.

For the case of Spain [ 10 ], find that for the period between January and July 2020, stringency in containment measures at the destination countries decreased Spanish exports, while imports did not succumb to such a sharp decline. Finally [ 25 ], extends the discussion of the Spanish case to analyse the impact of COVID-19 on trade in goods and services, corroborating the existence of a negative effect. He finds a more pronounced decline for trade in services, due to the importance of tourism in the Spanish economy.

Other studies have provided additional evidence by considering a larger sample of countries. Using monthly bilateral trade data of EU member states covering the period from June 2015 to May 2020 [ 20 ], use a gravity model framework to highlight the role of chain forward linkages for the transmission of Covid-19 demand shocks. They explain that when the pandemic spread and more prominent measures were taken, not only did demand decrease further, but labour supply shortage and production halted [ 21 ]. Find a negative impact of COVID-19 on trade growth for a sample of 28 countries and their most relevant trade partners. Their findings suggest that COVID-19 has affected sectoral trade growth negatively by decreasing countries’ participations in Global Value Chains from the beginning of the pandemic to June 2020 [ 26 ]. Analyse the impact of COVID-19 on trade for a larger sample of countries, focusing on export flows for 35 reporting countries and 250 partner countries between January and August in both 2019 and 2020. However, they restrict, their study exclusively to trade in medical goods and find that an increase in COVID-19 stringency leads to lower exports of medical products. Finally [ 27 ], use maritime trade shipping data from January to June 2020 for different countries, such as Australia, China, Germany, Malaysia, New Zealand, South Africa, United States, United Kingdom, and Vietnam. By applying the automatic identification system methodology to observational data, they obtain pronounced declines in trade, albeit the effect is different for each country.

Surprisingly, little attention has been paid to the impacts of COVID-19 on trade for different country income levels and we find several reasons to consider this issue as important. First, the role of trade costs is important, as the latter are related to economic policy and direct policy instruments (e.g., tariffs) are less relevant compared to other components [ 28 ]. According to [ 29 ], differences are expected in trade between high-,low- and middle-income countries due to the composition of trade costs: information, transport, and transaction costs seem to be more important for trade between high-income countries, while trade policy and regulatory differences better explain trade between low- and middle-income countries. The second reason is related to the composition of products, given that average skills in making a product are more intensive in high-income countries resulting in increasing complexity of the products traded compared to low- and middle-income countries [ 30 ]. Accordingly, specific product categories incorporate more embedded knowledge and their production may require engaging in a global production network with multiple countries. However, it has been alleged that participation of countries in global value chains depends on their income levels due to the objectives pursued: high-income countries focus on achieving growth and sustainability, while low- and middle-income countries seek to attract foreign direct investment and increase their economic upgrading [ 31 ]. Third, it is found that low-income countries present a lower share of jobs that can be done at home [ 32 ], rendering them more sensitive to lockdowns that affect services. Finally, due to the paucity of health supplies to mitigate COVID-19, as certain healthcare commodities may not be affordable for certain low-income countries [ 33 ]. Consequently, the effect of COVID-19 on the global economy may be more pronounced for those countries with fewer healthcare resources and impacts on trade do not constitute an exception.

Due to the reasons mentioned above, we expect different countries’ responses to trade shocks induced by COVID-19 depending on their income levels, but this issue remains largely unexplored by the academic literature. The only exception is [ 34 ], but they reduce their analysis to COVID-19 impacts on trade concerning Commonwealth countries. Using the period from January 2019 to November 2020, they find ambivalent evidence: an increase in the number of COVID-19 cases in low-income countries reduced Commonwealth exports, but an identical scenario in high-income countries boosted their export flows.

All these findings are summarized as follows. In Table 1 , we present a compilation of studies using monthly data that feature the impact of COVID-19 on trade.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258356.t001

It is also worth noting that the main shock started in March 2020, when most countries closed their borders and implemented lockdown measures. Accordingly, further analysis of COVID-19 impacts on trade requires periods with high frequency, such as monthly data, in order to deliver satisfactory results. Apart from the aforementioned studies in the context of COVID-19 research, to the best of our knowledge, monthly data are scarcely used in gravity models. They have been used either in the context of trade preferences [ 35 , 36 ] or, more recently, to study the impact of natural disasters on trade [ 8 ].

Additionally, we aim to provide evidence concerning the COVID-19 effects on trade at country level, without restricting our research to either specific countries or territories, or, specific trade flows, such as intermediate goods. Since the COVID-19 crisis is still ongoing, it is also necessary to incorporate the most recent and updated time spans to provide policy recommendations aligned with the business cycle. We intend to analyse whether COVID-19 impacts on trade have affected the world economy from a global perspective. This analysis will allow us to distinguish different impacts in terms of levels of economic development, which to the best of our knowledge, remain largely unexplored by the academic literature.

Empirical analysis

This section is organized into three separate sub-sections. First, we describe the empirical model and the estimation strategy. Second, we report information on data issues. Finally, we cover country policy responses to COVID-19.

Model description and estimation strategy

For the purpose of accomplishing our research objectives, we resort to a bilateral trade gravity model, which has progressively become the reference methodology for analysing the causal impacts of specific variables on trade (e.g., [ 22 , 37 – 40 ]; among other scholars).

Where subscripts i , j and m refer to exporter and importer country and month, respectively. COVID m is a control variable that takes value 1 for a COVID-19 trade shock, after March 2020, and 0 otherwise. DIST ij is the geographical distance between exporter and importer country. CONTIG ij is a control variable that takes value 1 when exporter and importer country are adjacent and 0 otherwise. COMLANG ij is a control variable that takes value 1 when exporter and importer country share a common language and 0 otherwise. COLONY ij is a control variable that takes value 1 when exporter and importer country share past colonial linkages and 0 otherwise. RTA ij is a control variable that takes value 1 when exporter and importer country have a regional trade agreement in force and 0 otherwise. In addition to these explanatory variables, we also consider other control variables to capture omitted factors. φ im and γ jm are exporter-month and importer-month fixed effects, respectively. Finally, ε ijm stands for the error term.

The logic behind including these variables is found in the literature, and the explanation is provided as follows: COVID-19-related variables are introduced to estimate the impact of the current COVID-19-shock on trade, since it is expected to be detrimental (e.g., [ 3 , 23 ]). Governmental actions are expected to reduce the duration and magnitude of COVID-19 shock by facilitating a smoother transition to a post-pandemic scenario while generating an economic downturn in the short-run due to the limitations of economic activity and the increase in government expenditure. Adjacency and distance relate to the geographical impacts on trade, given the great influence exerted by geography on trade patterns [ 43 ]. Adjacency is included due to the existence of a border effect, where countries tend to concentrate their trade flows with nearby trade partners [ 41 , 44 ], so that higher adjacency leads to increasing trade flows. The reasons to include distance in gravity models stem from the early contributions [ 45 ]. Countries prefer to trade with less distant trade partners, so that a negative coefficient is expected. Colonial linkages and common language respond to the flourishing literature on the impact of institutions on trade, where the latter play a key role in reducing trade costs and facilitating trade (e.g., [ 46 , 47 ]; among others). Finally, regional trade agreements have multiplied exponentially in the context of globalization and trade liberalization, so that they contribute to decreasing trade costs and enhancing trade [ 48 , 49 ].

Exporter-month and importer-month fixed effects are included to comply with multilateral resistance terms (MRTs), which are related to third-country impacts on the bilateral relationship. They are considered as a pivotal element of modern gravity equations [ 41 ]. According to the structural gravity literature, the omission of such aforementioned MRTs is expected to lead to inconsistent and biased outcomes [ 22 ].

Concerning the previous gravity specification, it is important to highlight that our baseline gravity Eq ( 1 ) does not contain GDP, which is considered a fundamental variable in the seminal gravity models because it measures country size [ 45 ]. The omission of GDP is intentional due to several reasons: (i) GDP variables tend to vary quarterly or yearly and (ii) the inclusion of exporter-month and importer-month fixed effects are perfectly collinear with GDP, so that these control variables will capture its effects on trade.

Eq ( 2 ) introduces some novelties in relation to the previous Eq ( 1 ). First, by interacting the COVID-19 variable with the control variable for regional trade agreements we can compute the impact of COVID-19 on trade by assuming that countries with regional trade agreements affect this empirical relationship. Thus we assess whether COVID-19 impacts on trade are more (less) profound for these countries with (without) previous regional trade agreements. We sum 1 to the variable before taking the logs to avoid losing the observations before the COVID started. This strategy responds to the strands of literature that acknowledge the role of international trade as a driver of business cycle synchronization (e.g., [ 51 , 52 ]) and, more specifically, that regional trade agreements may be behind the transmission of shocks across countries (e.g., [ 19 , 53 , 54 ]). In particular, we follow [ 26 ] approach since the interaction between COVID-19 variables and regional trade agreements allows us to study the heterogeneous impacts of COVID-19 on trade by bringing economic linkages into the discussion.

Another advantage is that interacting an explanatory variable with a control variable may also relieve us from endogeneity issues, as shown by [ 55 ]. In particular, COVID-19 impacts on trade may be driven by omitted variable bias. However, this comes at the cost of not interpreting exporter and importer impacts simultaneously, as both coefficients become symmetric and only one of them can be interpreted, as shown by [ 56 ] and [ 57 ] when studying the impact of institutions on trade using gravity equations at country and regional level, respectively.

Eq ( 2 ) also considers a third set of fixed effects, which are exporter-importer pair effects denoted by η ij . Considering pair effects in the gravity equation as an explanatory variable may pose the advantage of mitigating the estimation from endogenous impacts induced by time-invariant determinants (e.g., [ 58 , 59 ]) and hence may improve the empirical specification. Three-way fixed effects, constituted by pair, exporter-month and importer-month fixed effects, have become the spotlight in gravity specifications assessing the impact of natural disasters on trade, even for those scholars using monthly data, such as [ 8 ].

Finally, we acknowledge that the simultaneous inclusion of such three-way fixed effects, requires large amounts of data in order to carry out the estimation procedure. For this reason, sophisticated PPML estimation commands have recently been developed for gravity equation estimations, so that they can include a high number of dimensional fixed effects and run relatively fast in contrast to previous existing commands [ 60 , 61 ].

Our sample covers a set of 68 countries exporting across 222 destinations, between January 2019 and October 2020 with 31 of these exporters classified as high-income countries. Due to the specific monthly nature of COVID-19 shock, we rely on monthly bilateral trade flows gathered from UN Comtrade. Trade data were extracted on the 15 of February 2021, using the UN Comtrade Bulk Download service. According to the degree of availability of monthly trade flows for countries, our analysis covers aggregate trade flows. For those observations with missing trade flows, we conveniently follow previous studies that suggest that missing trade flows can be completed with zeros, [ 50 , 62 ].

Variables related to the COVID-19 government response have been taken from the systematic dataset of policy measures elaborated by the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford University [ 63 ]. These indices refer to government response, health measures, stringency, and economic measures. Their composition and implications are described more broadly in the following sections.

The rest of the variables, institutional and geographical, are gathered from the Centre d’Études Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (CEPII) Gravity database [ 64 ]. S1 and S2 Tables show the list of countries and the main descriptive statistics, respectively.

Policy responses to COVID-19: equal or unequal?

Once COVID-19 spread across a significant number of countries, they were urged to implement policy actions of response. For this reason, several indicators were built to measuring countries´ governmental response to COVID-19. As mentioned previously, the set of policy indicators developed by [ 63 ] constitutes the most noteworthy approach for measuring countries´ policy responses. The four indicators are described as follows:

- Stringency index (upper left chart, Fig 1 ) contains the degree of lockdown policies to control the pandemic via restricting people´s social outcomes. The index is built using data on the closure in education (schools and universities), public transport and workspaces, the cancellation of public events, limits on gatherings, restrictions in internal movements, and orders to confine at home.

- Economic Support index (upper right chart, Fig 1 ) includes measures related to public expenditure, such as income support to people who lose their jobs or cannot work, debt relief to households, fiscal measures, and spending to other countries.

- Containment and Health index (lower left chart, Fig 1 ) combines lockdown measures with health policies, such as the openness of the testing policy to all the population with symptoms or asymptomatic, the extent of the contact tracing, the policy on mandatory use of facial coverings, and monetary investments in healthcare and in vaccines.

- Overall Government Response index (lower right chart, Fig 1 ) collects all governments’ responses to COVID-19 by assessing whether they have become stronger or weaker. This index combines all the variables of the containment and health index and the economic support index.

Source: own elaboration from [ 63 ]. Note: each point represents a country, and the concentration of countries with similar values produces darker areas. Additionally, the mean and 95% confidence bands are represented.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258356.g001

These indices vary from 0 to 100, with a higher value indicating stronger country measures in response to COVID-19. As these indicators are collected daily, we convert them to monthly averages. The evolution of the four indicators is presented in Fig 1 , where each point represents a country and the concentration of countries with similar values produces darker areas. Additionally, the mean and 95% confidence bands are represented. We pay special attention to differences between high-income and low- and middle-income countries, in line with our research objectives.

Stringency reaches its maximum in April 2020 when the first wave reaches its peak in most countries. Since then, restrictions have been slowly lifted but started to increase again after the summer in high-income countries, coinciding with the beginning of the second wave.

Economic support increased rapidly in March and April and remains stable, with high-income countries granting more economic support to the population than low- and middle-income countries. The economic support variable identifies significant differences between high-income and low- and middle-income countries during the whole period.

The containment and health index and the overall government response index, present a similar pattern regarding income levels. However, we observe that low- and middle-income countries relaxed the measures from April 2021 onwards, whereas high-income countries did so in July 2021. In any case, the countries analysed show significant variability in all the indices, as indicated by the estimates made in the following section.

To sum up, we find that in low- and middle-income countries, pandemic measures have been slightly stricter than in high-income ones, as the values of their COVID-19 policy responses indices are higher for all cases except for the economic support index. The greater availability of resources in high-income countries to control the pandemic explains this difference.

Fig 2 displays the evaluation of total monthly exports in 2020, relative to January 2020, by income level for our sample of exporting countries. We observe the big decline in exports between March and April mentioned previously. In fact, the observed magnitude of trade decline as a consequence of COVID-19 is identical to the previous global recession, but contractions in GDP and trade flows are more profound at the current stage [ 65 ]. However, we observe that high-income countries have gradually been recovering their export flows, revealing a larger degree of resilience and how economic support policies might have helped them in recovering economic activity. In particular, greater firm engagement in trade because of previous global recession may be beneficial, as they have been able to recover in a shorter period of time from this new contraction in GDP due to the openness to foreign markets [ 66 ]. Find that net firm entry in export markets contributed less to export growth during the Great Trade Collapse, between 2008 and 2013, than continuing exporters. Export capacity to foreign markets in order to counteract the negative impact of local demand shocks is illustrated by [ 67 ] for the specific case of Spain.

Source: own elaboration using UN Comtrade trade data.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258356.g002

We acknowledge that policy responses differ by country, as the impacts of COVID-19 have been strongly unequal for countries due to several reasons. First, countries have reported differences in the number of deaths, mainly attributable to the population composition. There is an increasing number of elder populations in a significant number of high-income OECD countries [ 68 ] and this group is the most vulnerable to COVID-19 (e.g., [ 69 ]).

At the same time, countries have also implemented trade policy actions to mitigate the influence of COVID-19 on the global economy. For the sake of brevity and in line with the aim of the article, we only consider the trade policy response. Readers interested in analyzing a complete set of economic policy responses (i.e., budgetary and/or monetary) to COVID-19 are entitled to check the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Policy Tracker at https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19 .

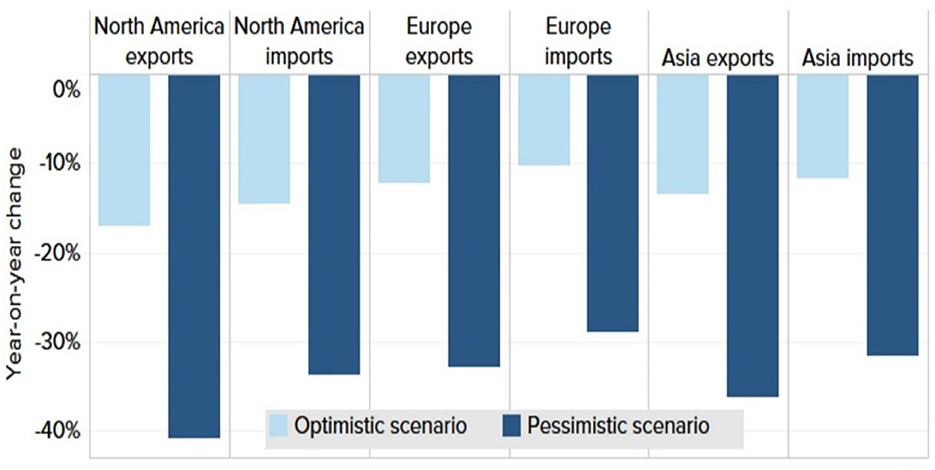

We focus on the corresponding period coincident with our sample, but further trade policy actions have been implemented after this period because of the increasing number of cases related to COVID-19 in subsequent waves. They can be checked at the IMF Policy Tracker previously reported, which is updated regularly [ 70 ]. Summarizes the major stylized facts during the first nine months of the pandemic. First, there was a noticeable rise in trade policy activism consisting mainly of export controls and import liberalization measures with strong cross-country variation. Second, this activism was reported to vary by country and products, where medical and food products experimented a substantial overall increase in their demand from February 2020. Third, we observe a further trade liberalization process after May 2020, where the number of liberalization measures exceeded the number of trade restrictions in medical products.

Such cross-country variation in trade policy response aligns with our expectations since, as mentioned previously, trade specialization differs by country. Accordingly, their sensitivity to the growing demand for food and medical products may vary substantially. For this reason, some countries were more resilient to COVID-19 trade shocks than other countries, as shown by the decreases observed in their trade flows. To this end, we compare trade drops for the most affected countries relative to January 2020 and their governmental response, from May 2020 to October 2020. As described by [ 70 ], countries experienced a substantial relaxation in most of their trade measures in May 2020.

For the ten countries with the largest trade drop evidence is ambivalent. For the sake of brevity, we have omitted the data concerning each country and provide a general overview. Data is available from the authors upon request to the corresponding author and can be obtained from the UN Comtrade database. On the one hand, four high-income (Macao, Mauritius, Portugal, and Slovakia) and six middle-income countries (El Salvador, Mexico, Montenegro, Guyana, Egypt, and Romania) were among the most affected countries in May 2020, with El Salvador registering the highest level of governmental response. Trade relative to January 2020 ranges from 51 to 69 percent in this period. On the other hand, we find that the number of high-income countries increased to six in October 2020 but, at the same time, differences in governmental response decreased their observed variance. Israel registered the highest level of governmental response during this month. In this case, relative trade ranges from 76 to 102, corroborating the previous finding that countries recovered rapidly from this trade shock. To sum up, despite differences in governmental response due to the impact of COVID-19 by countries, recovery can be alleged to follow similar patterns for the most affected countries.

This section is organized into three separate sub-sections. First, we present a benchmark analysis, and afterwards we show the main results obtained for the four different COVID-19 government policy response indices. Finally, we review whether COVID-19 impacts differ by levels of economic development.

Benchmark analysis

This section reviews four specifications of the gravity equation: Column (I) in Table 2 includes the COVID-19 binary variable without interactions and only including exporter and importer fixed effects. Column (II) departs from Eq ( 2 ) but introduces exporter-month and importer-month fixed effects and, finally, column (III) adds pair fixed effects to the specification showed in column (II). For this robustness analysis, we use COVID m variable, which takes value 1 from March 2020, when several countries worldwide implemented lockdown measures, and 0 otherwise.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258356.t002

The coefficients shown in column (I) may be biased because the specification does not accurately capture those factors related to MRTs and structural gravity. We hence move on to the alternative specification considered in columns (II) and (III), where we choose column (3) because it corresponds to Eq ( 2 ) and solves limitations in the baseline Eq ( 1 ).

Alternative specifications show an unequivocal detrimental effect of COVID-19 shock on trade. While the magnitude of the COVID-19 coefficient in column (I) is larger, -0.204, the size decreases when we move to our baseline specification in column (III), where we interact with the RTA variable, with an estimated coefficient of -0.050 when we include pair fixed-effects. The rest of the variables show the expected coefficients according to the theoretical insights and projections of gravity models.

Results by COVID-19 government policy responses indices

We now estimate our results introducing the four COVID-19 government response indices using Eq ( 2 ), as governments in countries more affected by the pandemic are expected to response with stringency, health, and economic support measures. Table 3 shows that the effect of COVID-19 on trade is negative and significant for all the variables considered. We agree with the existing literature on the negative impact of COVID-19 on trade (e.g. [ 21 , 23 ]); and also with the negative impact of previous pandemics [ 3 ]. We also find that results do not vary substantially across indices related to COVID-19, as they range between -0.009, for containment and health measures, and -0.012 for economic support. Although estimated parameters are not statistically different from each other, this might indicate that countries demanding more support to boost their economies have been the most affected ones by the COVID-19 trade shock. We also test our results using the traditional variable of COVID-19 reported deaths per million population as impact measure of the pandemic by country. Results, available under request, show no relevant variation to those presented in the article, which might be considered as an additional robustness test of the results presented.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258356.t003

Our results suggest that COVID-19 may be detrimental to trade flows for those countries engaged in previous regional trade agreements compared to the countries that were not members of these agreements, as shown by the result of interacting these variables. However, interaction terms fail to reflect that those countries not participating in regional trade agreements were not affected by COVID-19, given the large set of existing possibilities of trade integration between countries. Furthermore, these countries could have been expanding their trade flows via preferential trade agreements, which are less restrictive than regional trade agreements.