- < Previous Event

- Next Event >

Home > CURCE > 2019 > ORAL > 60

Oral Presentations

Presentation title.

The Ethics of False Advertising

Presenter Information

Melissa Pacifico , University at Albany, State University of New York Follow Kaylie Johnson , University at Albany, State University of New York Follow Phillip O'Meara , University at Albany, State University of New York Follow

The Press: Freedom, Bias, Ethics II

Lecture Center 22

3-5-2019 3:15 PM

3-5-2019 4:15 PM

Presentation Type

Oral Presentation

Academic Major

Business, Communication

False advertisement, the use of misleading and untrue information to push a consumer product, is an unethical marketing ploy that has tricked consumers since the beginning of the consumer business industry. With the modern emergence of social media, consumers are now vulnerable than ever to falling victim to these unethical deceptive representations. The ‘Fyre Festival’ documentaries that recently premiered on both Netflix and Hulu are a perfect example of modern day false advertising mixed with the use of unethical social media influencer advertising. In this research project we aim to uncover the significance of unethical advertising and research the results of both ethical and unethical advertising through the examination of four major companies who have been accused of using this tactic. The four companies we will be analyzing are Fyre, Groupon, Hydroxycut, and Redbull, since they are some of the well-known false advertising cases in the United States over the past few years. The goal of our research is to discover whether or not society falls for false advertising and how influencers and companies utilize unethical marketing to lure in consumers or followers. We will focus on four instances of false advertising and will understand how consumers were tricked into spending their money on a certain product, or going on a trip. We will analyze the marketing methods and tactics from each company and examine the trends that we find. We will be looking in depth at each lawsuit and analyze the results of both ethical and unethical advertising.

Select Where This Work Originated From

Course assignment/project

First Faculty Advisor

Chang Sup Park

First Advisor Email

First Advisor Department

The work you will be presenting can best be described as.

Finished or mostly finished by conference date

This document is currently not available here.

Since February 17, 2020

- Collections

- Disciplines

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

Author Corner

- Policies and Guidelines

- Open Access Policy

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Advertising made simpler for you. Read about new Advertising Trends, Campaigns, and Strategies.

Ethics in Advertising – It’s Importance and Effectiveness

Last updated on: January 24, 2024

In today’s consumer-driven world, advertising plays a significant role in shaping our perceptions, influencing our choices, and driving economic growth. However, with great power comes great responsibility. Ethical considerations in advertising have gained prominence as businesses strive to strike the right balance between persuasive marketing and responsible messaging. This article delves into the realm of ethics in advertising, exploring its importance, key principles, and real-world implications.

Table of Contents

What are Ethics in Advertising?

Ethics in advertising refer to the moral principles and standards that govern the conduct of advertisers and their communication with consumers. It involves ensuring that advertising messages are truthful, respectful, fair, and responsible, with a focus on protecting consumers’ interests and promoting societal well-being.

The Importance of Ethics in Advertising

Ethics in advertising hold immense significance for several reasons. Firstly, it fosters trust between advertisers and consumers. When advertisements are perceived as truthful, transparent, and respectful, consumers are more likely to develop positive attitudes towards brands and make informed purchasing decisions.

Secondly, ethical advertising contributes to the overall reputation of a company or industry. Advertisers who prioritize ethical practices not only attract loyal customers but also gain credibility and goodwill from the public. In contrast, unethical advertising can damage a brand’s image and lead to long-term negative consequences.

Transparency and Honesty in Advertising

Transparency and honesty are fundamental principles of ethical advertising. Advertisers should ensure that their claims are substantiated, avoiding false or misleading statements. Clear disclosures regarding product features, limitations, and potential risks must be provided to consumers. By maintaining transparency, advertisers establish credibility and build long-term relationships with their audience.

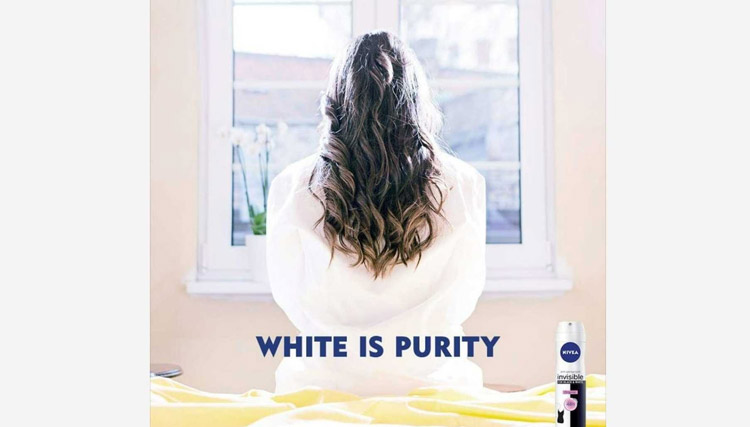

Avoiding Stereotypes and Offensive Content

Ethical advertising refrains from perpetuating stereotypes or using offensive content that may demean or marginalize individuals or communities. Advertisers should strive for inclusivity, embracing diversity in their campaigns and promoting positive social values. By avoiding stereotypes and offensive content, advertisers create an environment that celebrates and respects the diversity of their audience.

Respecting Consumer Privacy

Respecting consumer privacy is another vital aspect of ethical advertising. Advertisers must obtain consent when collecting personal information and ensure the secure handling of data. Transparency about data usage and providing opt-out mechanisms empower consumers to control their personal information, fostering trust and maintaining ethical standards.

Social Responsibility in Advertising

Ethical advertising encompasses social responsibility, where advertisers consider the broader impact of their messages on society. Advertisements should not encourage harmful behaviors, exploit vulnerabilities, or promote products that are detrimental to individuals or the environment. By embracing social responsibility, advertisers contribute positively to the well-being of communities and advocate for sustainable practices.

Balancing Creativity and Truthfulness

Ethical advertising strikes a delicate balance between creativity and truthfulness. While advertisements aim to capture attention and engage audiences, they should never sacrifice accuracy or misrepresent information. Advertisers can employ innovative and imaginative approaches while ensuring that the core message remains honest and authentic.

The Role of Regulatory Bodies

Regulatory bodies play a crucial role in upholding ethical standards in advertising. They establish guidelines and regulations that advertisers must adhere to, ensuring fairness, honesty, and transparency. These bodies monitor and investigate complaints, enforce penalties for violations, and protect consumers from misleading or deceptive advertising practices.

The Impact of Unethical Advertising

Unethical advertising can have far-reaching consequences. It erodes consumer trust, damages brand reputation, and undermines the integrity of the entire advertising industry. Moreover, misleading or manipulative advertisements can harm individuals by promoting unrealistic expectations, fostering insecurities, or exploiting vulnerabilities. Society as a whole suffers when unethical advertising practices prevail.

Case Studies: Ethical Advertising Campaigns

Numerous examples showcase the power of ethical advertising campaigns. The Dove “Real Beauty” campaign challenged traditional beauty standards, promoting self-acceptance and diversity. Patagonia’s “Don’t Buy This Jacket” campaign encouraged conscious consumption by urging consumers to consider the environmental impact of their purchases. These campaigns not only achieved commercial success but also made a positive impact on societal perceptions and behaviors.

Ethical Advertising: Challenges and Opportunities

Ethical advertising faces various challenges in today’s complex landscape. Advertisers must navigate the digital realm, where issues like ad fraud, data privacy, and invasive targeting pose ethical dilemmas. Additionally, the pressure to maximize profits and compete for consumers’ attention can tempt advertisers to employ questionable tactics. However, these challenges also present opportunities for advertisers to differentiate themselves by prioritizing ethics and establishing meaningful connections with their audience.

Educating Consumers about Ethical Advertising

Educating consumers about ethical advertising is vital for fostering a more discerning and informed audience. By increasing awareness about deceptive practices, promoting media literacy, and encouraging critical thinking, consumers can make more conscious choices and hold advertisers accountable for their ethical conduct. Collaboration between industry stakeholders, educational institutions, and advocacy groups can help empower consumers with the knowledge they need.

Measuring the Effectiveness of Ethical Advertising

Measuring the effectiveness of ethical advertising involves assessing its impact on consumer behavior, brand perception, and social attitudes. Metrics such as consumer trust, brand loyalty, purchase intent, and societal response can provide insights into the success of ethical advertising campaigns. By analyzing data and feedback, advertisers can refine their strategies and demonstrate the tangible benefits of ethical practices.

Ethical Advertising in the Digital Age

The digital age has revolutionized advertising, presenting both opportunities and challenges for ethical practices. Advertisers must navigate issues such as ad transparency, data privacy, and algorithmic bias. It is crucial to embrace responsible data collection, provide meaningful user experiences, and ensure that algorithms are unbiased and transparent. Adapting ethical principles to the digital landscape is essential for maintaining trust and relevance in the evolving advertising ecosystem.

In conclusion, ethics in advertising play a vital role in shaping the advertising landscape and maintaining a healthy relationship between advertisers and consumers. By adhering to ethical principles, advertisers can build trust, promote transparency, and foster positive societal values. The importance of honesty, transparency, respect, and social responsibility cannot be overstated in the world of advertising.

Ethical advertising not only benefits consumers by providing them with accurate information and empowering them to make informed decisions, but it also benefits advertisers themselves. Advertisers who prioritize ethics can establish a positive brand image, gain customer loyalty, and contribute to the overall reputation of their industry.

However, ethical advertising does face challenges in the digital age, such as data privacy concerns, algorithmic bias, and the need to adapt to evolving technologies. Advertisers must stay vigilant, embrace responsible practices, and adapt ethical principles to the digital landscape.

Educating consumers about ethical advertising is equally important. By raising awareness and promoting media literacy, consumers can become more discerning and make choices aligned with their values. Collaboration between industry stakeholders, educational institutions, and advocacy groups is key to empowering consumers with the knowledge they need.

Measuring the effectiveness of ethical advertising is crucial to demonstrate its impact and refine strategies. Metrics such as consumer trust, brand loyalty, and societal response provide valuable insights into the success of ethical advertising campaigns.

Ultimately, ethics in advertising contribute to a healthier and more sustainable advertising industry. By striking the right balance between persuasion and responsibility, advertisers can build lasting relationships, foster positive change, and create a trustworthy advertising environment.

FAQs Related to Ethics in Advertising

1. can ethics in advertising really make a difference.

Absolutely. Ethics in advertising have the power to shape consumer perceptions, build trust, and foster positive societal change. By adhering to ethical principles, advertisers can create meaningful connections with their audience and contribute to a healthier advertising industry.

2. How can consumers support ethical advertising?

Consumers can support ethical advertising by being aware of deceptive practices, promoting media literacy, and making conscious choices. By supporting brands that prioritize ethical advertising, consumers can influence the industry and encourage responsible practices.

3. What are the consequences of unethical advertising?

Unethical advertising can erode consumer trust, damage brand reputation, and harm individuals by promoting unrealistic expectations or exploiting vulnerabilities. It also undermines the integrity of the advertising industry as a whole.

4. How can regulatory bodies contribute to ethical advertising?

Regulatory bodies play a crucial role in upholding ethical standards in advertising. They establish guidelines, investigate complaints, and enforce penalties for violations, ensuring fairness, honesty, and transparency in advertising practices.

5. What role does social responsibility play in ethical advertising?

Social responsibility is a key aspect of ethical advertising. Advertisers should consider the broader impact of their messages on society, avoid promoting harmful behaviors, and advocate for sustainability and positive social values.

6. How important is ethics in advertising?

Ethics in advertising play a crucial role as they ensure transparency, trust, and credibility in the industry. Adhering to ethical principles helps build positive brand image, fosters long-term customer relationships, and avoids potential legal issues. Ultimately, ethics in advertising are vital for sustaining a reputable and responsible business.

7. What is the ethical side of advertising?

The ethical side of advertising involves promoting products or services while adhering to moral standards and societal norms. It emphasizes honesty, fairness, and respect for consumers’ rights. Ethical advertising avoids deceptive tactics, respects privacy, and provides accurate information, giving consumers the freedom to make informed choices.

8. What is an example of ethics in advertising?

An example of ethics in advertising is ensuring truthfulness in claims. When an advertisement accurately represents a product or service, it maintains ethical standards. For instance, a cosmetics company promoting the anti-aging effects of its product must provide reliable scientific evidence to support their claims. By doing so, they uphold ethical practices and avoid misleading consumers.

9. How do I know if an advertisement is ethical?

To determine if an advertisement is ethical, consider a few factors. First, check for transparency and honesty in the claims made. Look for evidence supporting the advertised benefits or features. Additionally, assess whether the advertisement respects consumers’ privacy and doesn’t engage in intrusive or manipulative tactics. Pay attention to any potential conflicts of interest, such as undisclosed sponsorships. By evaluating these aspects, you can gauge the ethical integrity of an advertisement.

You may also like:

Top 10 Micro-Moments in Marketing That Drive Conversions

What Is a Loyalty Program? Types, Benefits and Examples

Difference Between Advertising and Sales Promotion

IPL 2024 Experiences a Groundbreaking Television Broadcast with Unprecedented Features

One reply to “ethics in advertising – it’s importance and effectiveness”.

Refreshing read! It’s inspiring to see the center of attention on moral marketing practices. Integrity in reality units manufacturers aside in the modern-day market.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Looking for Advertising? 👀

Fill out the below form, and we will reach out to you!

Exploring Perceptions of Advertising Ethics: An Informant-Derived Approach

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 23 January 2018

- Volume 159 , pages 727–744, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Haseeb Ahmed Shabbir 1 ,

- Hala Maalouf 2 ,

- Michele Griessmair 3 ,

- Nazan Colmekcioglu 4 &

- Pervaiz Akhtar 1

19k Accesses

17 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Whilst considerable research exists on determining consumer responses to pre-determined statements within numerous ad ethics contexts, our understanding of consumer thoughts regarding ad ethics in general remains lacking. The purpose of our study therefore is to provide a first illustration of an emic and informant-based derivation of perceived ad ethics. The authors use multi-dimensional scaling as an approach enabling the emic, or locally derived deconstruction of perceived ad ethics. Given recent calls to develop our understanding of ad ethics in different cultural contexts, and in particular within the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, we use Lebanon—the most ethically charged advertising environment within MENA—as an illustrative context for our study. Results confirm the multi-faceted and pluralistic nature of ad ethics as comprising a number of dimensional themes already salient in the existing literature but in addition, we also find evidence for a bipolar relationship between individual themes. The specific pattern of inductively derived relationships is culturally bound. Implications of the findings are discussed, followed by limitations of the study and recommendations for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Perceived Greenwashing: The Effects of Green Marketing on Environmental and Product Perceptions

Impulse buying: a meta-analytic review

The influence of social media eWOM information on purchase intention

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although a unified understanding of what ethics in advertising should denote remains complicated by the multi-faceted and pluralistic nature of ethics (Drumwright 2008 ), there has been growing scholarly interest in “ad ethics”. The consensus appears to be that advertising is the most ethically charged aspect of marketing (Shabbir and Thwaites 2007 ; Richards 2008 ). Critics of advertising have raised concerns over its perpetuation of stereotypes and unbridled materialism or to its manipulative and persuasive nature (Pollay 1986 , 1987 ; Calfee 1997 ; Smith and Quelch 1993 ; Hyman et al. 1994 ), leading Beltramini ( 2003 ) to describe ad ethics as the “ultimate oxymoron”. However and despite the centrality of consumers in this discussion, we suggest that their views do not surface sufficiently in the derivation of what constitutes “ad ethics”, and yet as Ringold ( 1998 , p. 335) noted “individual consumers (not advertisers, not those who create and disseminate advertising, not the government) should be the final arbiters of what constitutes acceptable advertising practice”. Indeed, the most established view is that the viewing public should determine the (un)ethicality of ads (Laczniak 1998 ; Skipper and Hyman 1993 ). As Cook ( 2008 , p. 1) argues, ultimately “the soul of all meaningful advertisements lies in the respect shown to the person for whom that advertisement is designed” and yet a purely viewer- or informant-derived assessment of the underlying structure of ad ethics remains lacking. Although numerous studies have investigated consumer responses towards specific contexts in ad ethics and various public polls of attitudes towards advertising consistently find advertisers as one of the least ethical professions (Richards 2008 ), we know of no study, which derives the general perceptions of consumers towards ad ethics.

Without developing an understanding of consumer concerns towards advertising, it is difficult for an ad sector to anticipate the unintended consequences of unethical ads (Bush and Bush 1994 ; Treise et al. 1994 ; Polonsky and Hyman 2007 ). As Treise et al. ( 1994 , p. 68) elaborate, “Consumer opinion that a specific advertising practice is unethical or immoral can lead to a number of unwanted outcomes, ranging from consumer indifference toward the advertised product to more serious actions such as boycotts or demands for government regulation”. Therefore, determining consumer perceived ad ethics may shed important insights to guide ad agencies to act in ways commensurate with what consumers perceive as violations of ethical norms. Therefore, the aim of the current study is to address this deficiency by determining the general perceptions of ad ethics that the target audience holds. We do this by developing an inductively derived structure of ad ethics.

A Lebanese public perspective is used as an illustrative context for our study, thus addressing a second related gap, or the lack of understanding of ad ethics from different cultural perspectives. As Drumwright and Kamal ( 2016 , p. 173) argue this gap in our knowledge “has not received attention commiserate with its importance”. The notion that ethics vary across cultures has a rich and established tradition (Casmir 2013 ). Consumer perceived ethics are also dependent on cultural variations (Swaidan 2012 ) and by default, perceived ad ethics is also bound by a cultural dilemma since the target audience’s “culture filters our perceptions of what constitutes good or responsible consumption” (Belk et al. 2005 , p. 7). An audience-based derivation of ad ethics from the target cultural perspective could therefore reveal the unique combination of ethical characteristics associated with ads, effectively giving rise to a culture’s “fingerprint” of perceived ad ethics.

It is important to note from the onset that whilst previous studies have used the controversial nature of ads as a proxy for their unethical content (e.g. Treise et al. 1994 ), we avoid this assumption. Not all controversial ads are unethical, and vice versa. Controversial ads can also generate positive effects such as in social marketing awareness campaigns (Fam et al. 2009 ). Moreover, since ethics is based on moral philosophies which fluctuate with individual judgement, “there is no such thing as a right/wrong or ethical/unethical ad, there are only latitudes [or boundaries] of ethicality” (Bush and Bush 1994 , p. 33). The purpose of this article therefore is not to explore the philosophical discussions surrounding the rightness or wrongness of perceptions towards ads, but instead to determine the pattern of consumer thoughts in relation to ad ethics. As such, we provide advertisers with a means to determine the “boundaries or latitudes of ethicality” (Bush and Bush 1994 ) so that advertisers can become more aware of the parameters used by their target audiences to evaluate the (un) ethical content of their ads. In doing so, we demonstrate an approach, which enables locally or emic-based derived associations of ad ethics, which advertisers can subsequently assess to manage their own creative process in relation to aligning their content with consumer judgements of ad ethicality.

Two research questions form the basis of this study. First, what can a locally derived, or an emic-based approach uncover in relation to what constitutes perceived ad ethics? Second, how can this informant-based derivation of ad ethics inform our understanding of the multi-faceted and pluralistic nature of ad ethics? The remainder of this study is structured as follows. First, the lack of a general ad ethics perspective is derived from an overview of the extant literature. Second, a rationale is developed for an informant and emic-based approach. Next, we discuss the methodological approach selected, multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) as enabling unprompted or free elicitation of word associations linked to ad ethics, and therefore consistent with an informant and emic-based perspective. The case for using Lebanon as an illustrative context is elaborated. Thereafter, the findings of the MDS application to a sample of the Lebanese public are presented alongside a discussion of implications for theory development and elaboration. Finally, managerial implications, avenues for future research and limitations of the study are reviewed.

Literature Review

At its most fundamental level, ethics is often understood as a reference to “just or ‘right’ standards of behaviour between parties in a situation, based on individual moral philosophies” (Bush and Bush 1994 , p. 32). By extension, advertising ethics tends to focus on “what is right or wrong in the conduct of the advertising function, and concerns questions of what ought to be done, not just what legally must be done” (Cunningham 1999 , p. 500). Classifications of ad ethics differentiate between message (or content) and business ethics (Drumwright and Murphy 2009 ; Drumwright 2012 ). Message ethics relate to the ethical parameters surrounding the creation, dissemination and processing of ad messages or the “micro” perspective (Drumwright 2012 ) of ad ethics. Within this stream, important insights have emerged on specific advertising contexts. These range from gender stereotyping in ads (e.g. Boddewyn 1991 ; Gould 1994 ; Kilbourne 1999 ) and the vulnerability of children to advertising (e.g. Moore 2004 ; Preston 2004 ; Treise et al. 1994 ) to racial content in ads (e.g. Shabbir et al. 2014 ; Bristor et al. 1995 ) and the use of fear as an ad appeal (e.g. Hastings et al. 2004 ; Hyman and Tansey 1990 ; LaTour and Zahra 1989 ). In contrast, a business ethics approach adopts an organisational or “meso” perspective (Drumwright 2012 ) and deals with the ethics of the ad industry. The focus within this stream has been on uncovering practitioner attitudes towards ad ethics (Drumwright and Murphy 2004 ; Drumwright and Kamal 2016 ) or on how ad agencies should manage ethics (e.g. Hyman et al. 1990 ; Drumwright and Murphy 2009 ; Hyman 2009 ). Linking both these streams is yet a third more earlier perspective based on a largely philosophical or “macro” approach (Drumwright 2012 ) focusing on the aggregate effects of advertising. Here, the debate revolves around whether advertising serves as a “mirror”, merely reflecting the values of its target audiences (Holbrook 1987 ) or instead as a “distorted mirror”, and therefore as a manipulator of audience values (Pollay 1986 , 1987 ). Reviewing this debate, Alexander et al. ( 2011 ) conclude the evidence points to advertising as a “moulder” of its target audience’s values, both through its persuasive content (McCracken 1986 ; Sun 2015 ; Drumwright and Kamal 2016 ) and through its role as cultural intermediary (Cronin 2004 ; Cayla and Eckhardt 2008 ; Drumwright and Kamal 2016 ).

In what remains the only study to date to propose a multi-faceted typology on what constitutes ad ethics, Hyman et al. ( 1994 ) summarised, using extant literature at the time and interviews with advertising academics, the “primary topics” of consumer-based ad ethics inquiry. These primary topics were classified as (1) deception in ads, (2) advertising to children, (3), tobacco advertising, (4) alcohol ads, (5), negative political ads, (6) racial and (7) sexual stereotyping. The versatility of this typology is reflected in the fact that it “still provides researchers with the most rigorous and pragmatic agenda for exploring ethics in advertising” (Shabbir and Thwaites 2007 , p. 75). Despite the rich stream of studies exploring specific domains of consumer ad ethics, largely rooted in one of Hyman et al’s ( 1994 ) primary topic areas, our knowledge of what constitutes ad ethics purely from a consumer’s perspective remains much more limited. As a result, our understanding of the relationship between different audience derived ethical domains is also lacking.

Compounding the aforementioned gap in knowledge is the notable absence of exploring ad ethics from different cultural perspectives beyond Western markets (Drumwright and Kamal 2016 ; Moon and Franke 2000 ). Rising concerns of ad ethics in the popular and trade press of other global marketing contexts warrants extending the contextual domain of ad ethics (Drumwright and Kamal 2016 ). As LaFerle ( 2015 , p. 163) notes, if ad agencies are to succeed in an increasingly diverse marketplace, then “ethical behaviour and cultural knowledge are key”. One approach to investigating the ethics-culture nexus is the emic-etic dilemma. At its most basic level, this debate asks whether behaviour can be understood in terms of the culture in which it is derived from (emic) or whether cultural differences can be understood as variations of underlying common themes (etic) (Berry 1990 ; Casmir 2013 ).

When ad ethics have been explored in non-Western contexts, a cross-cultural lens has been adopted and therefore an etic, or “outside view” (Taylor et al. 1996 ) approach favoured, or where the assumption is that “Behavior [can be] described from a vantage external to the culture, in constructs that apply equally well to other cultures” (Morris et al. 1999 , p. 783). In contrast, emic or “inside” approaches to investigating cultural phenomenon rest on assuming that, “Behavior [can be] described as seen from the perspective of cultural insiders, in constructs drawn from their self-understandings” (ibid, p. 783). An emic-based conceptualisation of ethics is often derived through words or descriptors used by informants representing the local target audience (Taylor et al. 1996 ). As Reinecke et al. ( 2016 , p. 14) elaborate, it enables researchers to “experience-near understanding, that is, situated knowledge…of how individuals negotiate what is ethical or not in the social situation under study”.

In relation to ethics and culture, the universalist position reflects an etic approach in that it assumes that ethics supersede cultural limitations of any cultural system, does not necessarily equate or imply culture and instead a single set of values are applicable to all cultures (Hall 2013 ). In contrast, the relativist position argues for an emic perspective and suggests that “culture as a sense making system necessarily implies ethics” (ibid, p. 21). Relativists therefore advocate a more complex nexus between ethics and culture since ethics is assumed as intrinsic to cultural values and norms. Moreover, the relativist position suggests that since value systems are unique to each culture, its “insiders” can only judge ethics. Since morality is also culture bound, the plurality of ethics can be explained by the defining norms of the societal context in which it is being explored (Haidt and Joseph 2004 ). This position, therefore, accounts for the plurality of ethics as emerging from the relativism of underlying moral philosophies (Bush and Bush 1994 ; Crane and Matten 2004 ). A third position on the etic-emic dilemma argues for a dual role of universalism and relativism such that both are no longer considered as dichotomous perspectives (Hall 2013 ). This position assumes that underlying moral values, which underpin ethics, converge across cultures but the ethical evaluations of moral issues become refined by specific cultural norms and values (Morris et al. 1999 ).

Whilst several etic-based studies exist which examine ad ethics across cultures, no previous study has sought to derive general perceptions of ad ethics derived solely from the cultural audience under investigation. Moreover, those studies which have adopted an etic cross-cultural perspective have investigated particular domains of ad ethics such as attitudes towards sexual appeals (Garcia and Yang 2006 ; Sawang 2010 ), direct to consumer pharmaceutical advertising (Reast et al. 2008 ) or violent images (Waller et al. 2013 ). Similarly, where the focus has been on uncovering one particular culture’s attitude, the focus has again been on pre-selected ethical domains such as the ethics of food advertising in India (Soni and Singh 2012 ) or offensive advertising in Singapore (Phau and Prendergast 2001 ). Even when a more general approach has been adopted, combinations of pre-selected categories have remained the foci. Treise et al. ( 1994 ) and Mostafa ( 2011 ) for instance explore attitudes towards children, minority groups, sexual and fear appeals as correlates of advertising ethics. Emic-based derivations of consumer ad ethic contexts are fewer still but again specific domains have been the foci of the investigations such as Waller and Lanasier’s ( 2015 ) study on the attitude of Indonesian mothers towards the pervasiveness of children’s advertising.

Against this backdrop, we propose that an emic-based derivation of general ad ethics could contribute to our understanding of the multi-faceted and pluralistic nature of ad ethics. This approach is consistent with calls to conceptualise ad ethics in “a manner that satisfies the cultural expectations of consumers” (Rawwas 2001 , p. 203). Given the inductive nature of the emic-based logic, a priori assumptions of what constitutes ad ethics do not govern the structure of any emergent structure of perceived ad ethics. Instead, any theory development or elaboration on the nature of general perceptions towards ad ethics rests solely on emergent or inductively derived outcomes. Prioritising this informant-based logic is elaborated further.

Stakeholder Theory

Complementing an emic-based approach to investigating consumer perceived ad ethics further is stakeholder theory (Freeman 1984 ) or the view that managerial decision-making should “take account the interests of all stakeholders” (Jensen 2002 , p. 236). Among the myriad of potential stakeholders, consumers hold a particularly important position in advertising. O’Barr ( 1994 , p. 8) for instance contends, “the consumer is [the] ultimate author of the meaning of an ad, the intention of the [ad] makers becomes of secondary importance”, thus reiterating the overriding role of the consumer as “final arbiters” (Ringold 1998 ) or primary stakeholder in the consumption of advertising (Ringold 1998 ; Skipper and Hyman 1993 ; Alexander et al. 2011 ). However, and although the need to measure public attitudes towards ad ethicality is an established one (Hyman et al. 1994 ), “there are no currently recognised mechanisms for evaluating” (Polonsky and Hyman 2007 , p. 5) the unintended consequences of advertising on its primary stakeholders. Existing approaches to determining consumer derivations of ad ethics remain limited.

For instance, survey based approaches to measuring ad ethics have traditionally been problematic (Drumwright 2008 ; Skipper and Hyman 1993 ). Given the pluralistic nature of moral philosophies, “there appears to be no single standard of evaluation” for perceived ethics (Reidenbach and Robin 1988 , p. 879), an issue compounded within the “advertising community where messages are targeted to a mass audience” (Bush and Bush 1994 , p. 33). As a result, both single and multi-item scales for capturing ethical evaluations of adverts are open to misspecification and misinterpretation, and have been deemed “missing”, “vague” and “ambiguous” (Bush and Bush 1994 ; Skipper and Hyman 1993 ). Existing qualitative applications to uncover ad ethics also pose problems. A common practice for instance among ad agencies is to ask respondents for verbal self-reports to a pre-specified ad (Hyman and Tansey 1990 ). Whilst this constitutes a viable technique to gain direct insights from consumers, this approach still limits the array of potential associations due to the nature of the pre-coder specified stimuli. Despite its shortcomings, this method is widespread. A report by the ASA (Advertising Standards Authority), Public perceptions of offence and harm in UK advertising (ASA 2012 ), is largely based on consumer responses to a pre-selected number of ads to guide focus group discussions. The deciphering of meaning behind the symbology or story within the corpus of the ad, i.e. semiotic or narrative-based evaluations, has also been popular among ad agencies. However, these too are prone to coder subjectivity and influenced by coder socio-cultural norms, values and experiences (Coulter et al. 2001 ), and as a result would not be feasible if applied across an entire ad sector’s ethical positioning. We therefore propose an informant-based logic to overcome some of the aforementioned problems in ascertaining consumer perceived ad ethics.

Towards an Informant-Based MDS Approach

Informant-based research in advertising has evolved to assure that the informant, rather than the coder, should select the stimuli for research (Zaltman 1997 ) such that by “controlling the stimuli, informants are better able to represent their thoughts and feelings and identify issues that are both important to them and potentially unknown to the researcher” (Coulter et al. 2001 , p. 4). Given that individuals “may differ in the advertising activities they find (un)acceptable/(ir)responsible” (Polonsky and Hyman 2007 , p. 5), asking respondents to tap into their own associations with advertising ethics permits that individuals’ unique beliefs, values and experiences to form the basis of their personal judgments. We contend that an investigation of ad ethics based on pre-selected stimuli forces consumers to respond to a pre-determined list of attributes rather than allowing them to “describe the target stimulus in terms that are salient to [them]” (Reilly 1990 , p. 22). The free elicitation of associations from the target audience through an informative based approach therefore minimizes the “danger of forcing respondents to react to a standardised framework that may not be an accurate representation of their image” (Jenkins 1999 , p. 7). An informant-based approach to determine ad ethics is therefore also more consistent with an emic or “insider approach”, thus enabling a greater reflexive focus on “the unanticipated and unexpected—things that puzzle the researcher” (Alvesson and Kärreman 2007 , p. 1266). As Reinecke et al. ( 2016 , p. 14) argue such an approach ensures any theory development or elaboration is “…through the lens of the participant’s perceptions of his or her experiences rather than through the lens of abstract categories and concepts imposed by the researchers, including the normative assumptions that are always already inscribed into them”.

Given the methodological need to uncover audience perceptions without imposing pre-specified criteria to shape their judgements, we propose multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) as a viable technique to attain an informant-based derivation of perceived ad ethics. MDS comprises a number of procedures for analysing proximity data to identify “the underlying structure of complex psychological phenomena” (Pinkley et al. 2005 , p. 239) but critically does not require researchers to define categories for evaluation a priori. Instead, MDS allows dimensions to emerge solely on the basis of (dis)similarity ratings made by respondents. Within the context of this research, it means that we do not pre-specify the characteristics of ad ethics, but instead inductively derive the meaning of ad ethics through unprompted solicitation. This open, data-driven approach is in line with the notions of grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin 1997 ) and therefore ensures that the derived solution is truly informant-based and discovery-orientated in nature (Griessmair et al. 2011 ). Furthermore, this approach also ensures an emic-based derivation since the generation of the initial input and condensation to dimensions are performed by the target group, and thus the target group’s mental schemata is the underlying deriver of outputs. The latter point is especially important as people do not necessarily react to an “objective reality”, as interpreted by researchers and coders, but instead to their uniquely and individually experienced environment (cf. Ellis 1962 ; Lazarus 1989 ; Mahoney 1974 ). Finally, the rating procedure does not require respondents to directly provide ethical categories that underlie their judgments and perceptions—which might prove difficult considering the complexity of the phenomenon—but only to compare the stimuli and eventually provide descriptions. Thus, MDS enables the identification, categorisation, and labelling of perceptions even when the criteria used for the respective judgments are not fully explicit or not readily available in consumers’ minds (Pinkley 1990 ; Pinkley et al. 2005 ). Since raters are not “cognizant of existing theory and [therefore] blind to the purpose of the study” (Griessmair et al. 2011 , p. 1066), the findings are “less likely to be contaminated by the preconceptions or hypotheses of the researcher” (Pinkley et al. 2005 , p. 341). Systematic bias therefore is not eliminated by MDS but instead is minimised relative to alternative coding qualitative procedures (Griessmair et al. 2011 ). MDS also allows for calculating the goodness of fit of the identified dimensional solution (Borg and Groenen 2005 ; Hair et al. 2010 ). As such, it provides for additional reliability, relative to content analytical techniques for instance (Griessmair et al. 2011 ), Finally, since the aim of our study is in establishing boundaries or latitudes of ethicality from an informant perspective, MDS is particularly suitable as it encapsulates the relativity of informant-elicited responses (Griessmair et al. 2011 ). A general sample from the Lebanese public provides an appropriate context for our study for several reasons.

The Lebanese Context

First, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has been “historically ignored in advertising research” (Kalliny et al. 2009 , p. 92) and indeed in the wider domain of international marketing research (Lages et al. 2015 ). Despite being “portrayed by the sensationalistic media as politically unstable and potentially violent” (ibid, p. 5), the MENA region is characterised by rising levels of young consumers (Pew Research 2011 ), exponential growth in media proliferation (Dubai Press Club 2012 ) and therefore increasingly attractive for business opportunities (Lages et al. 2015 ; Drumwright and Kamal 2016 ). Second, and not unlike other emerging economies, MENA contexts have the potential to challenge conventional marketing thinking (Burgess and Steenkamp 2006 ) and facilitate the re-assessment of existing conceptualisations of marketing theory (Akbar and Samii 2005 ). In an era of globalisation, where “MENA [remains] largely ignored as academics focus on the evolving advertising industry in the West” (Smith, 2016 , p. 3), MENA contexts, therefore, provide fertile examples to extend research in ad ethics beyond Western markets (Drumwright and Kamal 2016 ; Moon and Franke 2000 ; Smith 2016 ). However, as Smith ( 2016 , p. 3) elaborates, given their “…lack of regulation, exponential economic growth, media revolutions and rapid move towards consumer-oriented thinking”, MENA contexts are particularly vulnerable to unethical marketing. Drumwright ( 2016 , p. 1) also argued that a particular problem in the MENA region is the notable lack of “…laws that prevent people from doing misleading advertising or if there are laws they aren’t enforced or are so specific that they don’t really deal with the important issues”. Consequently, the MENA ad landscape is particularly “…ripe for ethical infractions” (Drumwright and Kamal 2016 , p. 173) and therefore warrants attention.

Third, and specifically in relation to Lebanon, the Lebanese ad sector is considered to be the most controversial in the MENA region (Kraidy 2007 ; 2010 ; Farah and El Samad 2015a ). Whilst we recognise that not all ad controversies are necessarily unethical, nor all unethical content deemed controversial, public concerns and criticisms of Lebanon’s ad landscape are rooted in established ethical infractions. These concerns for instance range over its widespread advertising of guns and armaments (Farah and El Samad 2014 ), political and sectarian messages (Dakroub 2008 )—often in conjunction with racial innuendoes (Farah and El Samad 2014 )—and its overt sexualisation of women (Anderson 2013 ). Although sexism in advertising is a worldwide phenomenon, it has been described as salient issue in Lebanon (Anderson 2013 ; Farah and El Samad 2015b ). Until recently Lebanon also had no restrictions on tobacco advertising (Farah and Samad 2015a ).

Fourth, as a “betwixt and between nation, [or] a hybrid culture” (Kamalipour and Rampal 2001 , p. 329), Lebanon, is “possibly one of the most complex in the region in terms of culture and society” (Farah and El Samad 2014 , p. 345). Its relative non-compliance with the values governing other MENA ad sectors characterised by more traditional Arab cultural and ethical norms (Kalliny et al. 2009 ; Farah and El Samad 2015a ), is reflected in its own ad sector. According to Nasr ( 2010 ), Lebanon is unique in the MENA region given its post-conflict struggle in defining a unified self-identity (Nasr 2010 ; Farah and Newman 2010 ) or in what has become a “nation-state with no sense of nationality to unite its people” (Nasr 2010 , p. 1). Traditionally caught between two poles, a pre-colonial pan-Arab or a post-colonial Francophone identity, the national agenda in Lebanon has been on reconstructing a new unified “Lebanese identity” (Nasr 2010 ). Recently, Lebanese advertisers have been at the forefront of this national agenda to mould a “new” post-modernist cosmopolitan identity, which “transcends ideological and religious differences” (ibid, p. 1). Common to cosmopolitan identity construction, the identities shown in Lebanese ads increasingly want to express a “space where cultures mirror one another” (Hannerz 1996 , p. 104) and therefore reinforce a fusion of multiple local and, simultaneously, global identity ideals. Lebanon therefore serves as an ideal illustrative context to demonstrate whether perceived ad ethics reflects underlying social and cultural ideals and as result, therefore also demands for a non-invasive approach. It is for this reason we focus on a general sample of the Lebanese public.

Generating Input for MDS

The initial phase of MDS focuses on the free elicitation of mental stimuli to generate the initial input data (Mitchell and Olson 1981 ; Olson and Muderrisoglu 1979 ). This process requires respondents to verbalise anything that “first comes to their mind” in relation to the subject, and thereby ensures that a variety of associations in relation to the phenomenon are generated (Steenkamp and Van Trijp 1997 ). An online link was posted (containing the open question “ What words or phrases first come to your mind when you think of ‘Ethics in Advertising’”?) on various English-based Lebanese social media sites. Pre-screening questions ensured all respondents were citizens of Lebanon and had current residency in Lebanon. Associations were collected from a sample of 131 Lebanese consumers and were balanced according to gender (46.5% of the sample are males, 53.5% females) and age (average age of 30.4 years), thus reflecting the age and gender profile of the Lebanese public (CIA 2016 ). Respondents generated on average four associations, resulting in a total of 524 associations. The next phase of MDS focuses on the (dis)similarity between these elicited aspects. As the distance-matrix is generated using similarity ratings, it is sufficient that identical or very similar associations are considered only once in the rating procedure. Thus, and consistent with other MDS studies within advertising contexts (e.g. Griessmair et al. 2011 ) the original set was condensed by removing duplicate responses, synonyms as well as words that are content-wise similar. Only six associations were removed for content-wise similarity but numerous synonyms and duplicate words were removed. The remaining 386 associations served as input for the MDS procedure.

Although a number of methods are available to create distance matrices (Borg and Groenen 2005 ; Young and Hamer 1987 ), the subjective clustering method is the only one capable of handling the large amount of input statements involved in the present study (Griessmair et al. 2011 ) and is subsequently described. A convenience sample of Lebanese raters, recruited through snowballing, and representing the gender, age and residency profile of the original sample were used to sort the 386 associations into decks based on the perceived similarity of the associations. Associations within a deck are maximally similar to each other and maximally dissimilar to the other decks, thus fulfilling the conditions of a subjective clustering approach. Raters were advised to sort the associations one-by-one and regularly check the decks for consistency and re-sort the cards if necessary. In a final step, the raters had to name each deck and shortly describe why they considered the associations in the pack to be similar to each other and dissimilar from those sorted into the other packs. This assessment provides valuable information for the eventual interpretation and classification of the dimensions. The sorting procedure took on average 80 mins and was assisted by a moderator (i.e. one of the authors) to ensure that instructions were read, understood, and fully implemented throughout the session. Even though Dong ( 1983 ) showed that raters’ boredom and fatigue do not significantly influence MDS solutions, we included options for several breaks to avoid rater depletion, although no rater opted to take one, thus confirming Dong’s ( 1983 ) insight. A constant comparison technique was employed in reaching a theoretical sample size of 15 raters, with consistency checks made concurrently based on dimensional outputs, stress levels and goodness of fit indices.

Data Analysis

The frequency with which the associations have been sorted into the same deck by the different raters represents the degree of similarity of associations. The resulting proximity data were subsequently analysed using Proxscal (Borg and Groenen 2005 ). Before initiating interpretation, the different dimensional solutions were rotated (Varimax) and normalised. The overall goal of the analysis is to identify the solution with the fewest dimensions and the richest interpretation (Borg and Groenen 2005 ; Young and Hamer 1987 ). In contrast to other exploratory methods, MDS does not provide a final criterion for determining the “right” number of dimensions and their interpretation (Hair et al. 2010 ). For the present study, and consistent with MDS consistency checks (Borg and Groenen 2005 ; Kruskal and Wish 1977 ; Spence and Graef 1974 ; Young and Hamer 1987 ), we employ criteria based on goodness of fit. Table 1 shows the values indicating goodness of fit for the one- to five-dimensional solutions. Following the elbow-criterion (Kruskal and Wish 1977 ), the five-dimensional is deemed most optimal for this study. Moreover, the reported stress values indicate statistical support of the derived solution based on the sample of raters (see Table 1 ).

It has to be noted that stress values increase with the number of word associations (MacCallum and Cornelius 1977 ). Thus, for the present study with 386 word associations, we expect higher stress values than in classical marketing applications usually involving only about 7–18 stimuli (Bijmolt and Wedel 1999 ; Henry and Stumpf 1975 ). Although the goodness of fit provides important information about the quality of the chosen solution, several scholars advise against using it as primary criterion (Jaworska and Chupetlovska-Anastasova 2009 ; Steyvers 2002 ). As pointed out by Chen ( 2003 , p. 79), “the goal of MDS mapping is not merely to minimize the stress value; rather, we want to produce a meaningful and informative map that can reveal hidden structures in the original data”. Thus, the goodness-of-fit measures were considered as preliminary criteria and the main focus was placed on deriving meaning behind the emergent dimensions.

For this level of interpretation, we applied a purely inductive approach in line with basic principles of Grounded Theory (Glaser and Strauss 1967 ). The interpretation process starts with contrasting the extreme values of each dimension. Associations exhibiting high loadings on a particular dimension and low loadings on the other dimensions are especially indicative for the respective dimension (Pinkley et al. 2005 ). By contrasting the endpoints, the preliminary meaning of the dimensions are established.

Consistency Check

In a next step, a multi-dimensional perspective is taken and additional consistency checks of associations located between the poles of dimensions are performed. These associations should “represent a blending of the identified dimensions and ideally form clusters” (Griessmair et al. 2011 , p. 1072). The facets should meaningfully reflect a blend of two or more dimensions, depending on the dimension they relate to more strongly. In order to facilitate understanding, we visualise the dimensionalisation via two-dimensional perceptual maps. These maps present each association or facet as having two coordinates in a two-dimensional space, and visually portray the extent to which these facets load on the relative dimensions (Griessmair et al. 2011 ). The map plots each association, whereas the proximity of two associations with each other indicates how similar they are perceived to be. The items should ideally form clusters located between the axes. The clusters are made of items that are very close in space, thus perceived similar by the various coders. Extreme associations and clusters between the axes of two dimensions should simultaneously define both dimensions. It is important to note, however, that this interpretation is two dimensional and some associations may load high on other dimensions as well. Therefore, consistency checks are made for all dimensional outputs. Consistency checks resulted in a set of dimensions with stable meanings along their respective endpoints. In order to facilitate methodological understanding, we exemplify consistency checks for two of our dimensions (namely dimensions 3, which has subsequently been denoted Moral myopia–Sexuality) and 4 (subsequently conceptualised as Politics-CSR) in “ Appendix ”.

In this iterative process of contrasting extreme values, performing consistency checks, and recurrently integrating the raters’ characterisation, the meaning of the dimensions is revised and altered until a consistent interpretation emerges. This classification of the dimensions was conducted by three independent judges and aided by the characterisations that the raters had earlier provided. Using Perreault and Leigh’s ( 1989 ) inter-coder reliability measure, reliabilities exceeded the critical cut-off value of 0.80. The interpretation process detailed above was conducted for all dimensional solutions that met the goodness-of-fit criteria. The five-dimensional solution deemed most appropriate is shown in Table 2 .

In the subsequent section, we summarise the main inductively derived bipolar themes within each dimension. Subsequently, and to demonstrate the theoretical contribution of the findings, we discuss the results in light of existing theory.

Dimension 1 (“True Functions of Advertising—Lack of Concern for Advertising Standards”) describes ideal functions of advertising on the one end, and the concern of a lack of regulation for advertising on the other end. Free word associations from respondents representing this dimension range on the one end (for “True Functions of Advertising”) from “ Know your product, love your product ” (0.9616), “ Good offers and prices ” (0.9450) to “ Respect for competitive products ” (0.8923); and on the other end (for “Lack of Concern for Advertising Standards”) from “ No regulations ” (− 0.9918) to “ No control in advertising ” (− 0.9416) and “ No limits ” (− 0.9063).

Dimension 2 (“Deception and Manipulation—Diversity”) describes at the end of one pole the salient features of the diverse Lebanese culture, such as “ No racial discrimination in Lebanon ” (− 0.8995), “ Respect everyone’s point of view ” (− 0.8906) and “ Reflects the society we’re living in ” (− 0.8211). At the other end, we find associations reflecting deception and manipulation such as “ Fake facts in ad messages ” (0.9291) and “ We trick the customer into believing that by owning this product, he’ll be making the deal of his life ” (1.00).

Dimension 3 (“Moral myopia–Sexuality”) suggests that sexuality strongly relates to ethics in ads on the one hand (for example “ Sexual connotations ” (− 0.9642), “Women’s sexuality to advertise unrelated products/services” (− 0.9501) and “ Sex appeal is being used as the easiest approach to people’s desires ” (− 0.9464). On the other hand, several associations relate to the justification of advertisers’ behaviours such as “ Advertising is only a tool ” (0.735), “ Advertising messages are most of the time honest ” (0.7220), “ There’s room to be more courageous ” (0.7571) and “ Ethics are governed by savvy consumers ” (0.6904). Drumright and Murphy ( 2004 , p. 11) in an investigation of advertising agencies, defined such sentiments as Moral myopia, or when “individuals [have] difficulty seeing ethical issues or seeing them clearly”.

Dimension 4 (“Political Advertising—CSR”) refers to associations about humanitarian and local causes, in particular to children’s welfare, on the one hand, and associations about a concern for political marketing in Lebanon on the other hand. The CSR associations include “ Children’s Cancer Center of Lebanon (CCCL) ” (0.9208), “ Nothing with potential to be harmful to children ” (0.7663) and “ Contribution/donation ” (0.9305). Associations for unethical political marketing practices include references to “ Political brainwashing ” (0.8882), “ Black market at times of elections” (0.9993) and “ Politicians abusing the ad system ” (1.00).

Dimension 5 (“Harmful Effects—Cultural Self-Identity”) refers to associations related to promoting the national and cultural identity through traditional icons and values on the one hand, and harm and dishonesty on the other hand. National values are expressed through associations such as “ Strong national brand identity ” (− 0.9164), and “ Nice local twist (using “Lebanese” phrases)” (0.7774). Associations reflecting harm and dishonesty include “ Corruption ” (0.8604), “ Lying ” (0.7742) and “ Unfair ” (0.7518).

The specific combinational pattern derived from our findings adds to our understanding of the multi-faceted and pluralistic nature of perceived ad ethics, since we know of no existing study, which positions specific violations in consumer perceived ad ethics (e.g. harm or deception) against specific cultural ideals (e.g. diversity or cultural identity). Unlike previous studies on ad ethics, our study sought general views on “ad ethics”, thus opening up associations linked to ethical ideals as well as violations. We therefore extend existing typologies such as Hyman et al. ( 1994 ) and Drumwright and Murphy ( 2009 ) by proposing a dual approach, namely that for consumers, “ad ethics” is a confluence of ideals and violations which together shape the overall “latitudes or boundaries” of consumer perceived ad ethics. The imperative for this duality is consistent with Hyman ( 2009 , p. 199) who proposed that, “without an ideal for responsible ads, organisations are less likely to avoid irresponsible ads”.

Critically however, we find that although both ad ethics-based violations and ideals are distinct they are also inter-related, in a bipolar manner. Take for instance, the pervasive political advertising landscape of Lebanon positioned against the lack of evidence of CSR practices, or harm against cultural identity. Effectively, our study has provided a mechanism to identify the doppelgänger, or “twin opposite” image (Thompson et al. 2006 ) of individual sub-dimensions comprising “perceived ad ethics”. In doing so, we extend the debate on advertising as a reflection of societal values, but within the context of ad ethics. Therefore, from a theoretical perspective, we provide an initial foray into a distorting “mirroring effect” (cf. Pollay 1986 , 1987 ) but between ethical violations and ideals related to ad ethics. We demonstrate that certain violations in ad ethics are related negatively to specific ideals, the expression of which may be culturally bound. Based on this, it can be argued that the pluralistic and multi-faceted nature of ad ethics is more complex than previously thought. We therefore propose that perceived ad ethics, not unlike ethics in general (Casmir 2013 ; Hall 2013 ) is also a confluence of both universalism and relativism. Whilst the violations derived in the MDS output, or deception, harm, sexual imagery and political advertising, are largely universalist themes in ad ethics and therefore common to most global codes of conduct for advertising (e.g. CAMPC 2011 ), the derived ideals are largely culturally bound and therefore more reflective of relativist themes. To support this proposition, we delve deeper into theorising at the individual dimensional level to demonstrate how the specific pattern arising from our study can indeed be traced to nuances within the socio-cultural fabric of the target audience. In doing so, we also elaborate on existing theories related to individual dimensional levels.

As a polar opposite of the “True functions of advertising”, the “Lack of concern for advertising standards” emerged in consumers’ minds. This should come as no surprise since critics of advertising often propose to strengthen existing industry and legal standards or to introduce regulations as a means to overcome problems inherent in advertising ethics (e.g. Cohen-Eliya and Hammer 2004 ). The fact that both polar dimensions also include positive and negative associations reflects the complexity of this debate. This intra- and inter-dimensional tension suggests an unresolved debate among the Lebanese audience and reflective of the wider debate commonly found in academic research, where advocates of increased regulations face proponents who believe in the inherent functionality of advertising (e.g. Cohen-Eliya and Hammer 2004 ; Phillips 1997 ). It also points to consumers’ ability to articulate the largely macro and philosophical business ethics perspective (Drumwright and Murphy 2009 ) case to ad ethics. However, it is within message based ad ethics dimensions where we see greater culturally influenced derivation.

Although diversity-related aspects, as well as deception, have attracted strong attention within the advertising literature (see for e.g. Hyman et al. 1994 ; Phillips 1997 ; Shabbir and Thwaites 2007 ; Cohen-Eliya and Hammer 2004 ; Taylor and Stern 1997 ; Williams et al. 2004 ), this is the first study to show their categorisation as dimensional opposites. This bipolar nature of diversity and deception can be understood as a contribution to Aditya’s ( 2001 ) call for extending our understanding of deception in marketing to include psycho-sociological effects on individuals and therefore to include ads that have “…the potential to…cause an erosion of ethical values deemed desirable in society”. According to Darke and Ritchie ( 2007 ), deceptive ad content can generate a dual processing effect such that consumers will actively motivate themselves to protect against subsequent deception. Therefore, in a culture where deceptive ad content is associated with recurrent stereotypical portrayals of sectarian differences, as in the case of Lebanon, it is possibly that a dual processing effect generates the ethical ideal of diversity to counter this deceptive theme. In other cultural contexts, other ideals of ethical values may become the primary disassociate counterpart of deceptive ads, depending on public perceptions of which cultural ideals have been violated by the ad sector’s deceptive content.

Sexual imagery has also attracted considerable attention in the extant literature on ad ethics (e.g. Boddewyn 1991 ; Cohan 2001 ; Gould 1994 ; Latour and Henthorne 1994 ) and given its widespread use, the sexualisation of women has traditionally been viewed as one of the most pervasive violations of ad ethics (Boddewyn 1991 ). Our findings indicate that sexual imagery forms a bipolar opposite with moral myopia or when “individuals [have] difficulty seeing ethical issues or seeing them clearly” (Drumwright and Murphy 2004 , p. 11). Moral myopia in our findings was reflected in shifting the blame on the educated consumer or society, arguing that what is legal is moral and emphasising the rights of the advertiser as rationalisations for accepting unethical ad content. Our findings contribute to Belk et al. ( 2005 ) who also found this rationalisation but towards unethical corporate practices as a justification for ambivalence towards unethical consumption. In addition however, the bipolar nature of moral myopia and sexuality suggests that it is possible when sexual expression in ads become normalised in a culture, the public may become desensitised to such an extent that rationalisation becomes the only alternative counterpart. This is consistent with the normalisation of cultural stereotypes since when stereotypes become embedded and normalised within cultures, those cultures may resist breaking such stereotypes by building cognitive defences to justify them (Cohen-Eliya and Hammer 2004 ).

Given its “special status” and “above the law” nature, political advertising has attracted growing public concern (Kaid 2004 ; Lau et al. 2007 ) as well as traditionally being one of the primary ethical concerns in advertising (Hyman et al. 1994 ). The relationship between political communications and CSR has, however, only been discussed from an organisational perspective, whether generally (Aguilera et al. 2007 ; Scherer and Palazzo 2011 ; Jamali and Neville 2011 ; Fooks et al. 2013 ) or within the context of ad agencies (Drumwright and Murphy 2009 ). Negative political communications can, however, also impact civic attitudes and system-based beliefs, or those linked to public attitudes to government and its functionality (Lau et al. 2007 ). The Lebanese political culture provides an ideal context for CSR to emerge as a bipolar dimensional opposite of political advertising. At one extreme, Lebanon is unique in that political advertising has become as pervasive as corporate advertising (Maasri 2009 ) and political mistrust saturated. A report by the World Economic Forum ( 2014 ) for instance scored Lebanon having the highest public mistrust of any country in the world, ranking it 148th out of 148 in the “public trust in politicians” category. Lebanon has historically suffered from a “relative absence of state-sponsored social safety” (Cammett 2014 , p. 38) leaving the space for non-state sectarian actors to instead provide a sense of “compassionate communalism” (Cammett 2014 ). One consequence of this has been a growing consensus that enabling CSR is detached from state support. According to Sakr ( 2013 ), state imposed “bureaucratic and regulatory obstacles” (Sakr 2013 , p. 1) have caused Lebanon to lag behind other MENA countries in harnessing CSR initiatives. Work by Jamali and colleagues (Jamali and Mirshak 2007 ; Jamali et al. 2009 ; Jamali and Neville 2011 ) on CSR in Lebanon finds that executives struggle to prioritise CSR due to political volatility and turbulence. In a healthy political climate, one would expect the political apparatus to be associated with local benefits but our findings indicate that the opposite can also ensue in a climate where mistrust of political communication reaches saturation levels. It would, however, be interesting to assess if other civic attitudes are linked to political advertising in alternative cultural settings.

Harmful effects of advertising emerged as a separate negative dimension of ad ethics, which is in line with the most prevalent criticism of irresponsible ads—their potential for harm (e.g. Phillips 1997 ; Nebenzahl and Jaffe 1998 ; Hyman 2009 ). Positioned against harm, however, is cultural self-identity confirming the salience of this ethical ideal for the Lebanese public. As previously noted, Lebanese advertisers are increasingly keen to place viewers in a “culturally sterile” sphere (Nasr 2010 ). This need has arisen from an historical imperative for post-conflict identity re-construction. As Nagel ( 2000 , p. 226) suggests, the national agenda in Lebanon has been on fostering “an allegiance to Lebanon that supersedes narrow sectarian affiliations”, the latter which has often been perpetuated by Lebanon’s ad landscape. The need for regaining a sense of cultural unity and shedding sectarian differences, which may have been responsible for causing national trauma, is a social imperative in post-conflict societies (LaCapra 1999 ). It is easy therefore to see therefore how associations of harm, the most direct and obvious violation arising from unethical ad content, would be positioned against cultural self-identity, which for any post-conflict society is of paramount importance (Nagel 2000 ; LaCapra 1999 ).

Finally, our study makes a methodological contribution since no study to date has employed an emic, or indeed etic, based approach to derive general thoughts about ad ethics. The MDS approach employed demonstrates that informant-based techniques can provide a viable diagnostic tool for an ad sector to determine what is most salient to their audiences in relation to ad ethics. The bipolar opposites of each dimension represented the “outer limits” of the MDS solution generated and therefore represent the boundaries or latitudes of perceived ad ethics, or the most salient issues. It may be that additional intra-dimensional themes also exist, formed from combinations of dimensions but any such additional themes, would by default, be shaped by one or more of the bipolar themes already identified. Additional intra-dimensional sub-clusters of themes would almost certainly add to the emic derivation of the target audience’s unique fingerprint of ad ethics. The value of the MDS technique has therefore been in fulfilling the original aim of the study of determining the latitudes or boundaries of perceived ad ethics, and therefore the most salient dimensions of ad ethics.

Managerial Implications

Our research provides several managerially relevant insights. The audience-based understanding of ad ethics can and should be integrated in the development of country specific ethical codes that, in contrast to codes formed from generalisations, or global codes of conduct, provide additional guidance for companies’ day-to-day behaviour in the local ad sectors they serve. Ad agencies can benefit from knowing that what may appear salient to their audience can help in the designing of ad content that is socially and morally responsible. Informant-based approaches to determining ad ethics provide the ad sector with a “finger on the pulse” assessment as part of an on-going evaluation of consumer public opinion in relation to ad ethics. Our approach therefore advocates a shift away from ad and research agency pre-determined parameters for evaluating ad ethics to an informant based and therefore emic orientation in defining and understanding the priorities, which should shape the ethicality of ads.

Identifying the bipolar nature of ethical domains also has important implications for regulating the ad sector and for ad agencies eager to align their content with their target audience norms and values, since if ad content fails to promote particular cultural ideals, this may become linked to a particular violation in ad ethics. Knowing which cultural ideals are linked to perceived violations can help the sector to better understand how its own content relates to its target audience’s understanding of ethics. Promoting one end of a dimension, diversity for instance, may help in leveraging against public perceptions against its bipolar opposite, or deception. Similarly, reducing deceptive content may become linked to a heightened sense of advertiser responsibility towards diversity. Further research would be needed to validate this strategic option for improving ethical standards in ad content, but our study provides an initial foray into identifying patterns between salient themes of ad ethics.

Limitations

Despite the obvious utility of MDS, it is not without limitations. A key limitation is the degeneracy of solutions, which occurs when perceptual maps “are not accurate representations of the similarity responses” (Hair et al. 2010 , p. 558). This problem could arise if all respondents provide similar word associations, if a local minimum is reached despite low stress levels, if there are other inconsistencies in the data or if the MDS program cannot reach a stable solution. Recommendations to deal with degeneracy proposed by Hair et al. ( 2010 ) were followed and we did not detect any common signs of degeneracy (no perceptual output was characterised by either a circular pattern (that is when objects are found to be equally similar) or a clustered pattern (where objects are grouped at bipolar ends of a single dimension).

We also recognise the cross-sectional nature of the sample does not take into account potential changes in the audience’s perceptions over time. Just as ethical relativism is based on societal definitions of morality, cultures and underlying social norms do evolve and change over time (Crane and Matten 2004 ). This is particularly the case with public perceptions influenced by controversies. The authors are for instance currently engaged in assessing the effect of the Jimmy Saville sexual child abuse controversy in the UK, on pre- and post-perceptions of child abuse in the British public to demonstrate such shifting perceptions.

Avenues for Further Research

This study is by no means an exhaustive one and as such provides an interesting platform for further research avenues. For instance, the specific dimensions we derived in our study are specific to the Lebanese public’s perspective. Do alternative cultural contexts generate the same key dimensions but in alternative combinations? How specific or generalizable is ethics in advertising cross-culturally? Is the Lebanese “fingerprint” truly a “fingerprint” or does it shift over time, that is how stable is this solution? Given the simplicity of conducting an MDS study and the increasing need to legitimise advertisement content in conjunction with the audience’s perspective, MDS is ideal as a “finger on the pulse” diagnostic tool for the sector to determine the fluctuating and/or stable underlying structure of perceived ad ethics.

We strongly suggest future researchers to incorporate other socio-demographic and attitudinal constructs (e.g. religion, willingness to boycott unethically advertised products) and perhaps behaviours (e.g. media consumption and literacy) to advance our understanding of a segmentional approach to understanding ad ethics. Carrigan et al. ( 2005 p. 488) explain that measurements in an international setting “should be developed in those settings not modified to reflect their contextual specifics”. An MDS-based approach clearly responds to this recommendation by drawing a picture of a specific population’s unique understanding of ad ethics. Future research might use the findings presented within this study, as well as MDS applied to other stakeholder groups, to assess potential differences between academic, practitioner and consumer understanding of ethics in advertising. A cross-cultural study to assess the impact of cultural dimensions on perception of ethics also constitutes an interesting avenue for further research. It is likely that some of the dimensions derived in this study are particularly salient to the Lebanese context, such as political marketing or cultural identity congruence. Further research would be needed to validate how locally determined perceived ad ethics truly is.

Beyond establishing MDS as viable methodological approach, we provide a first illustration of how ad ethics is perceived from an audience perspective. This perspective has been largely missing from the academic debate, but the knowledge can be leveraged to pre-empt unwarranted consumer-based outcomes. The multi-faceted and pluralistic nature of ad ethics indicates a complex inter-play between consumer concerns, the precise nature influenced by local and cultural priorities but also underpinned by more universal concerns related to ad ethics. Taken collectively, we believe that a viewer-based conceptualisation of ad ethics was long necessary and hope that the findings provided within this paper will stimulate more informant-based research to further understand the multi-faceted and pluralistic nature of ad ethics.

Aditya, R. N. (2001). The psychology of deception in marketing: A conceptual framework for research and practice. Psychology & Marketing, 18 (7), 735–761.

Google Scholar

Advertising Standards Authority (ASA). (2012). Public perceptions of offence and harm in UK advertising. ASA.

Aguilera, R., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multi-level theory of social change in organisations. Academy of Management Review, 32 (3), 836–863.

Akbar, Y. H., & Samii, M. (2005). Emerging markets and international business: A research agenda. Thunderbird International Business Review, 47 (4), 389–396.

Alexander, J., Tom C., & Shrubsole, G. (2011). Think of me as evil? Opening the ethical debates in advertising. Public Interest Research Centre , pp. 1–63.

Alvesson, M., & Kärreman, D. (2007). Constructing mystery: Empirical matters in theory development. Academy of Management Review, 32 (4), 1265–1281.

Anderson, B. (2013). Shock value, sexism and superficiality: Lebanon’s advertising problem. The Daily Star, Lebanon, October 9th. http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2013/Oct-09/234028-shock-value-sexism-and-superficiality-lebanons-advertising-problem.ashx . Accessed October 27, 2016.

Belk, R. W., Devinney, T., & Eckhardt, G. (2005). Consumer ethics across cultures. Consumption Markets & Culture, 8 (3), 275–289.

Beltramini, R. F. (2003). Advertising ethics: The ultimate oxymoron? Journal of Business Ethics, 48 (1), 215–216.

Berry, J. W. (1990). Imposed etics, emics, derived etics: Their conceptual and operational status in cross-cultural psychology. In T. N. Headland, K. L. Pike, & M. Harris (Eds.), Emics and etics: The insider/outsider debate (pp. 28–47). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.