How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

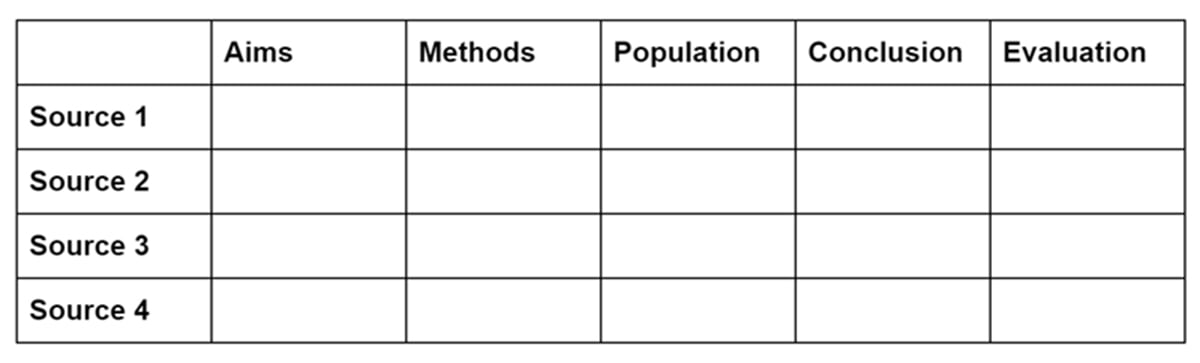

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

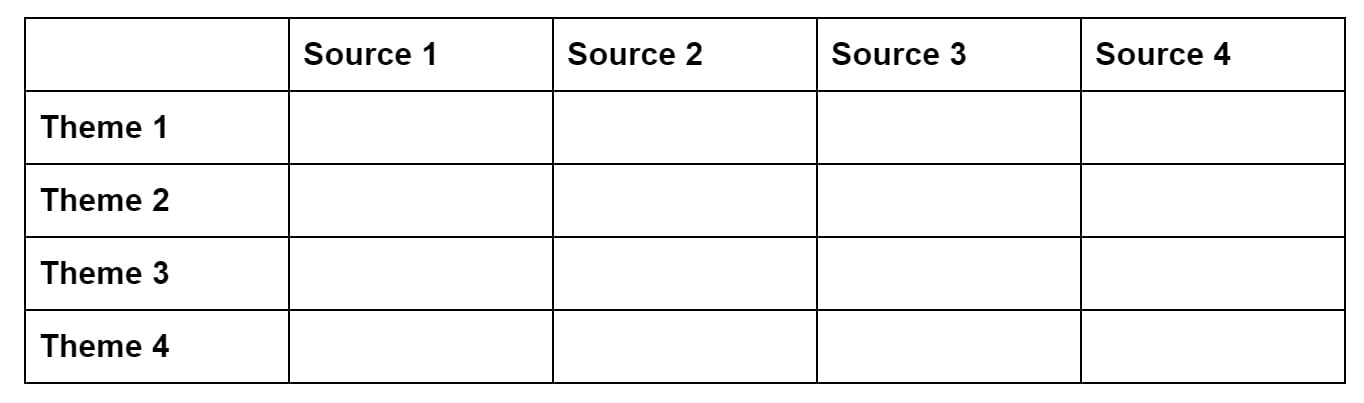

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

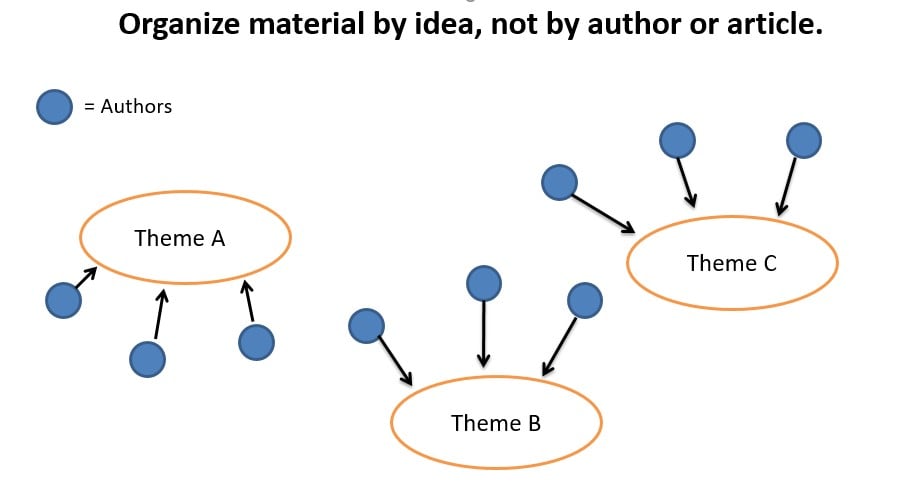

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Synthesizing Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you look for areas where your sources agree or disagree and try to draw broader conclusions about your topic based on what your sources say, you are engaging in synthesis. Writing a research paper usually requires synthesizing the available sources in order to provide new insight or a different perspective into your particular topic (as opposed to simply restating what each individual source says about your research topic).

Note that synthesizing is not the same as summarizing.

- A summary restates the information in one or more sources without providing new insight or reaching new conclusions.

- A synthesis draws on multiple sources to reach a broader conclusion.

There are two types of syntheses: explanatory syntheses and argumentative syntheses . Explanatory syntheses seek to bring sources together to explain a perspective and the reasoning behind it. Argumentative syntheses seek to bring sources together to make an argument. Both types of synthesis involve looking for relationships between sources and drawing conclusions.

In order to successfully synthesize your sources, you might begin by grouping your sources by topic and looking for connections. For example, if you were researching the pros and cons of encouraging healthy eating in children, you would want to separate your sources to find which ones agree with each other and which ones disagree.

After you have a good idea of what your sources are saying, you want to construct your body paragraphs in a way that acknowledges different sources and highlights where you can draw new conclusions.

As you continue synthesizing, here are a few points to remember:

- Don’t force a relationship between sources if there isn’t one. Not all of your sources have to complement one another.

- Do your best to highlight the relationships between sources in very clear ways.

- Don’t ignore any outliers in your research. It’s important to take note of every perspective (even those that disagree with your broader conclusions).

Example Syntheses

Below are two examples of synthesis: one where synthesis is NOT utilized well, and one where it is.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for KidsHealth , encourages parents to be role models for their children by not dieting or vocalizing concerns about their body image. The first popular diet began in 1863. William Banting named it the “Banting” diet after himself, and it consisted of eating fruits, vegetables, meat, and dry wine. Despite the fact that dieting has been around for over a hundred and fifty years, parents should not diet because it hinders children’s understanding of healthy eating.

In this sample paragraph, the paragraph begins with one idea then drastically shifts to another. Rather than comparing the sources, the author simply describes their content. This leads the paragraph to veer in an different direction at the end, and it prevents the paragraph from expressing any strong arguments or conclusions.

An example of a stronger synthesis can be found below.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Different scientists and educators have different strategies for promoting a well-rounded diet while still encouraging body positivity in children. David R. Just and Joseph Price suggest in their article “Using Incentives to Encourage Healthy Eating in Children” that children are more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they are given a reward (855-856). Similarly, Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for Kids Health , encourages parents to be role models for their children. She states that “parents who are always dieting or complaining about their bodies may foster these same negative feelings in their kids. Try to keep a positive approach about food” (Ben-Joseph). Martha J. Nepper and Weiwen Chai support Ben-Joseph’s suggestions in their article “Parents’ Barriers and Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating among School-age Children.” Nepper and Chai note, “Parents felt that patience, consistency, educating themselves on proper nutrition, and having more healthy foods available in the home were important strategies when developing healthy eating habits for their children.” By following some of these ideas, parents can help their children develop healthy eating habits while still maintaining body positivity.

In this example, the author puts different sources in conversation with one another. Rather than simply describing the content of the sources in order, the author uses transitions (like "similarly") and makes the relationship between the sources evident.

- How it works

"Christmas Offer"

Terms & conditions.

As the Christmas season is upon us, we find ourselves reflecting on the past year and those who we have helped to shape their future. It’s been quite a year for us all! The end of the year brings no greater joy than the opportunity to express to you Christmas greetings and good wishes.

At this special time of year, Research Prospect brings joyful discount of 10% on all its services. May your Christmas and New Year be filled with joy.

We are looking back with appreciation for your loyalty and looking forward to moving into the New Year together.

"Claim this offer"

In unfamiliar and hard times, we have stuck by you. This Christmas, Research Prospect brings you all the joy with exciting discount of 10% on all its services.

Offer valid till 5-1-2024

We love being your partner in success. We know you have been working hard lately, take a break this holiday season to spend time with your loved ones while we make sure you succeed in your academics

Discount code: RP0996Y

How to Synthesise Sources – Steps and Examples

Published by Olive Robin at October 17th, 2023 , Revised On October 17, 2023

The ability to effectively incorporate multiple sources into one’s work is not just a skill, but a necessity. Whether we are talking about research papers, articles, or even simple blog posts, synthesising sources can elevate our content to a more nuanced, comprehensive, and insightful level. But what does it truly mean to synthesise sources, and how does it differ from the commonly understood techniques of summarising and paraphrasing?

Importance of Synthesising Sources in Research and Writing

When finding sources , it is imperative to distinguish between various available information types. Secondary sources , for example, provide interpretations and analyses based on primary sources. Synthesising goes beyond the mere gathering of information. It involves the complex task of interweaving multiple sources to generate a broader and richer perspective. When we synthesise, we are not just collecting; we are connecting.

By merging various viewpoints and data, we provide our readers with a well-rounded understanding of the topic. This approach ensures that our work is grounded in credible sources while also adding unique insights.

Summarising, Paraphrasing, and Synthesising

At first glance, these three techniques might seem similar, but they serve distinctly different purposes:

Summarising

Synthesis is the art of blending multiple sources to create a unified narrative or argument. It is essential to use signal phrases to introduce these sources naturally, helping the reader follow the information flow. Block quotes can also be used for direct quotations, especially if they’re longer.

Paraphrasing

Here, we restate the original content using different words. While the wording changes, the essence and core meaning remain intact. This method is useful for clarifying complex ideas or for tailoring content to a specific audience.

Synthesising

Synthesis is the art of blending multiple sources to create a unified narrative or argument. It is not about echoing what others have said; it is about drawing connections, identifying patterns, and building a cohesive piece that holds its own merit.

What is Synthesising Sources?

Synthesising sources is a method used in research and writing wherein the author combines, interprets, and analyses information from various sources to generate a unified perspective, narrative, or argument. It involves a process that we can call source evaluation . It is an intricate process that goes beyond simply collecting data or quoting authors. Instead, it involves evaluating, integrating, and constructing a new narrative based on a collective understanding of all the sources under consideration.

Imagine a quilt where each piece of fabric represents a different source. Synthesising would be the act of sewing these individual pieces together in such a way that they form a beautiful, cohesive blanket. Each piece retains its uniqueness but contributes to the larger design and purpose of the quilt.

Objective of Synthesising

- Synthesising allows writers to delve deeper into topics by using a multitude of perspectives. This offers a more robust and comprehensive view than any single source could provide.

- By integrating diverse sources, authors can identify trends, consistencies, or discrepancies within a field or topic. This can lead to new insights or highlight areas needing further exploration.

- By interlinking sources, writers can add layers of complexity to their arguments, making their content more engaging and thought-provoking.

- While the sources themselves might not be new, the way in which they are combined and interpreted can lead to fresh conclusions and unique standpoints.

- Relying on a single source or a few like-minded ones can inadvertently introduce biases. Synthesising encourages the consideration of diverse viewpoints, ensuring a more balanced representation of the topic.

Why is Synthesis Important?

The art of synthesis, while a nuanced aspect of research and writing, holds unparalleled significance in constructing meaningful, in-depth content. Here is a detailed exploration of why synthesis is pivotal:

Enhancing Comprehension and Knowledge Depth

- Depth Over Breadth: While a vast amount of information exists on nearly any topic, true understanding isn’t about skimming the surface. Synthesising allows you to dive deeper, connecting various pieces of information and seeing the bigger picture.

- Clarifying Complexity: Topics, especially those in research, can be multifaceted. By merging multiple sources, we can simplify and explain intricate subjects more effectively.

- Reinforcing Concepts: By revisiting a concept from various sources and angles, the repetition, in a way, strengthens our grasp on the subject. It’s like studying from multiple textbooks; the overlap in content solidifies understanding.

Avoiding Plagiarism

- Original Thought Generation: While synthesising, you are compelled to merge ideas, compare viewpoints, and draw unique conclusions. This process naturally leads to producing original content rather than merely reproducing what one source says.

- Skilful Integration: A well-synthesised piece does not heavily rely on long, verbatim quotes. Instead, it seamlessly integrates information from various sources, duly cited, minimising the chances of unintentional plagiarism.

- Reflecting Authentic Engagement: When you synthesise, it showcases your genuine engagement with the material. It’s evident that you have not just copied content but have wrestled with the information, pondered upon it, and made it your own.

Developing a Holistic Perspective on a Topic

- Seeing the Full Spectrum: Single sources can offer a limited or biased viewpoint. Synthesis, by its nature, compels you to consult multiple sources, allowing for a more balanced and comprehensive view.

- Connecting the Dots: Life, society, and most academic subjects are interconnected. Synthesis helps recognise patterns, draw parallels, and understand how various elements interplay in the grand scheme of things.

- Elevating Critical Thinking: The act of synthesis hones your critical thinking skills. You’re constantly evaluating the validity of sources, comparing arguments, and discerning the weight of different perspectives. This makes your current work stronger and sharpens your intellect for future projects.

Steps of Synthesizing a Source

Here is a step-by-step guide on how to synthesise sources.

Step 1: Read and Understand

Before you can synthesise sources effectively, you must first understand them individually. A strong synthesis is built upon a clear understanding of each source’s content, context, and nuances.

Tips To Ensure Comprehension

- Annotations: Make notes in the margins as you read, highlighting key points and ideas.

- Summarisation: After reading a section or an article, write a brief summary in your own words.

- Discussion: Talk about the content with peers or mentors. This can help clarify any confusion and deepen your understanding.

- Questioning: Constantly ask questions as you read. If something is unclear, revisit the content or consult supplementary materials.

Step 2: Identify Common Themes

Sources will often touch upon similar themes, even if they approach them differently. Recognising these themes can act as a foundation for synthesis.

- Mind Mapping: Visualise the interconnectedness of topics and subtopics.

- Lists: Create lists of similar ideas or arguments from different sources.

- Highlighting: Use colour codes to highlight recurring themes across different documents.

Step 3: Analyse and Compare

Different sources might have diverging opinions or findings. Recognising these differences is crucial to produce a balanced synthesis.

- Side-by-Side Analysis: Put the information from various sources next to each other to see how they align or diverge.

- Critical Evaluation: Ask yourself why sources might have different perspectives. Consider the methodology, context, or biases that could contribute.

Determining the Relevance of Each Source

Not all sources will hold equal weight or relevance in your synthesis.

- Criteria Checklist: Establish criteria for relevance (e.g., publication date, author credentials) and evaluate each source against this.

- Priority Setting: Decide which sources offer primary insights and which offer supplementary information.

Step 4: Organise Information

A clear structure is essential to guide your readers through the synthesised narrative.

- Outlines: Create a traditional outline that sequences your main points and supports them with subpoints from your sources.

- Flowcharts: For more complex topics, flowcharts can visually demonstrate the progression of ideas and their interconnections.

Step 5: Craft Your Narrative

This step involves the actual writing, where you combine the insights, evidence, and analysis into a singular narrative.

- Transitional Phrasing: Use transitions to move between ideas and sources smoothly.

- Voice Consistency: Even though you integrate multiple sources, ensure that the narrative maintains a consistent voice and tone.

Step 6: Cite Appropriately

Always credit original authors and sources to maintain integrity in your work and avoid plagiarism. Knowing how to cite sources is crucial in this process.

- In-text Citations: Whenever you refer to, paraphrase, or quote a source, provide a citation.

Different Citation Styles and Choosing The Right One

There are multiple citation styles (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago), and your choice will often depend on your discipline or the preference of your institution or publication.

- Guideline Review: Familiarise yourself with the preferred citation style’s guidelines.

Citation Tools: Consider using tools like Zotero, Mendeley, or EndNote to help streamline and manage your citations.

The research done by our experts have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- Authentic Sources

Examples of Source Synthesis

Let’s explore some examples of synthesising sources.

Example 1: Synthesising sources on climate change

Scenario: You have sources that discuss the causes of climate change. Some sources argue for anthropogenic (human-caused) factors, while others emphasise natural cycles.

Synthesis Approach

- Begin with an overview of climate change, its impacts, and its significance.

- Introduce the anthropogenic viewpoint, citing research on the rise of CO2 from industrial processes, deforestation, etc.

- Present the natural cycle perspective, highlighting periods in Earth’s history where temperature fluctuations were observed.

- Discuss overlaps, such as how human activities might exacerbate natural cycles.

- Conclude by emphasising the consensus in the scientific community about human contributions to recent climate change, but acknowledge the existence of natural cycles as part of Earth’s climate history.

Example 2: Merging Historical Texts on a Particular Event

Scenario: You are examining the Battle of Waterloo from British, French, and Prussian primary sources.

- Provide background on the Battle of Waterloo, setting the stage.

- Introduce the British perspective, detailing their strategies, key figures, and their account of the battle’s progression.

- Shift to the French viewpoint, noting their strategic decisions, challenges, and Napoleon’s role.

- Explore the Prussian account, emphasising their contributions and coordination with the British.

- Highlight areas of agreement among the sources (e.g., timeline of events) and areas of discrepancy or unique insights (e.g., differing reasons for the outcome).

- Conclude with a comprehensive view of the battle, incorporating insights from all perspectives and its significance in European history.

Example 3: Synthesising Qualitative And Quantitative Research On A Social Issue

Scenario: You are researching the effects of remote learning on student performance and well-being during the pandemic.

- Start with an introduction to the sudden shift to remote learning due to COVID-19.

- Present quantitative data: statistics showcasing the drop or rise in student grades, attendance rates, and standardised test scores.

- Introduce qualitative insights, like interviews or case studies, highlighting student sentiments, challenges faced at home, or feelings of isolation.

- Discuss the interplay between numbers and narratives. For instance, a drop in grades (quantitative) could be related to a lack of motivation or home distractions (qualitative).

- Compare outcomes across different demographics, using both types of data to show how remote learning might affect diverse student populations differently.

- Conclude with a holistic understanding of the impacts of remote learning, noting areas that need further research or intervention.

Common Mistakes to Avoid when Synthesising Sources

- Relying heavily on a single source limits the depth and breadth of your understanding. It may also inadvertently introduce bias if that source isn’t comprehensive or neutral.

- How to Avoid: Ensure you consult various sources for a well-rounded view. This includes both primary and secondary sources, academic articles, and more accessible pieces like news articles or blogs, if relevant.

- Every source comes with its own perspective. Identifying these biases can lead to a skewed understanding of your topic.

- How to Avoid: Critical reading is key. Always consider who the author is, their potential motivations, the context in which they’re writing, and the methodologies they use.

- Simply presenting what each source says without drawing connections or highlighting contrasts misses the essence of synthesis.

- How to Avoid: As you research, actively look for common themes, conflicting viewpoints, and unique insights. Your goal is to weave a narrative that reflects a comprehensive understanding of all these elements.

Tools and Resources for Synthesising Sources

These are the different tools that can be used for synthesising sources.

Citation Tools

Managing references can be cumbersome, especially when dealing with numerous sources. Citation tools can help organise, format, and insert citations with ease.

- Zotero: A free, open-source tool that helps you collect, organise, cite, and share research.

- Mendeley: A reference manager and academic social network that can help you organise your research, collaborate with others online, and discover the latest developments.

Mind-Mapping Software or Apps

Mind mapping helps visually organise and interlink ideas, making the synthesis process more intuitive.

- MindMeister: An online mind-mapping tool that lets you capture, develop, and share ideas visually.

- XMind: A popular mind mapping and brainstorming software with various templates to help structure your thoughts.

Note-Taking Apps and Strategies

Effective note-taking is fundamental to understanding and organising information from various sources. Digital note-taking apps often offer features like tagging, search functionalities, and integration with other tools.

- Evernote: A cross-platform app designed for note-taking, organising, and archiving.

- Microsoft OneNote: A digital notebook that allows you to gather drawings, handwritten or typed notes, and save web clippings.

- Cornell Note-taking System: A structured method of note-taking that divides the paper into sections, encouraging active engagement with the material.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a literature review.

A literature review is a comprehensive survey of existing research on a particular topic, synthesising findings to provide an overview of key concepts, debates, and gaps in knowledge. It establishes a foundation for new research, highlighting relevant studies and contextualising them within the broader academic conversation.

How to synthesise a source?

To synthesise a source, thoroughly understand its content, and then integrate its insights with information from other sources. This involves comparing and contrasting viewpoints, identifying patterns, and constructing a cohesive narrative or argument that offers a broader perspective rather than merely echoing the original source’s content.

Why do I need to cite sources?

Citing sources acknowledges original authors, maintains academic integrity, and provides readers with a reference for verification. It prevents plagiarism by giving credit to the ideas and research of others, allowing readers to trace the evolution of thought and confirm the reliability and accuracy of the presented information.

What are topic sentences?

Topic sentences are the main statements that introduce and summarise a paragraph’s main idea or focus. They provide context and direction, helping readers follow the writer’s argument or narrative. Typically placed at the beginning of a paragraph, they act as signposts, guiding the flow of the discussion.

You May Also Like

Critical thinking is the disciplined art of analysing and evaluating information or situations by applying a range of intellectual skills. It goes beyond mere memorisation or blind acceptance of information, demanding a deeper understanding and assessment of evidence, context, and implications.

In a world bombarded with vast amounts of information, condensing and presenting data in a digestible format becomes invaluable. Enter summaries.

A secondary source refers to any material that interprets, analyses, or reviews information originally presented elsewhere. Unlike primary sources, which offer direct evidence or first-hand testimony, secondary sources work on those original materials, offering commentary, critiques, and perspectives.

As Featured On

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

Splash Sol LLC

- How It Works

A Guide to Evidence Synthesis: What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Meet Our Team

- Our Published Reviews and Protocols

- What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Types of Evidence Synthesis

- Evidence Synthesis Across Disciplines

- Finding and Appraising Existing Systematic Reviews

- 0. Develop a Protocol

- 1. Draft your Research Question

- 2. Select Databases

- 3. Select Grey Literature Sources

- 4. Write a Search Strategy

- 5. Register a Protocol

- 6. Translate Search Strategies

- 7. Citation Management

- 8. Article Screening

- 9. Risk of Bias Assessment

- 10. Data Extraction

- 11. Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Evidence Synthesis Institute for Librarians

- Open Access Evidence Synthesis Resources

What are Evidence Syntheses?

What are evidence syntheses.

According to the Royal Society, 'evidence synthesis' refers to the process of bringing together information from a range of sources and disciplines to inform debates and decisions on specific issues. They generally include a methodical and comprehensive literature synthesis focused on a well-formulated research question. Their aim is to identify and synthesize all of the scholarly research on a particular topic, including both published and unpublished studies. Evidence syntheses are conducted in an unbiased, reproducible way to provide evidence for practice and policy-making, as well as to identify gaps in the research. Evidence syntheses may also include a meta-analysis, a more quantitative process of synthesizing and visualizing data retrieved from various studies.

Evidence syntheses are much more time-intensive than traditional literature reviews and require a multi-person research team. See this PredicTER tool to get a sense of a systematic review timeline (one type of evidence synthesis). Before embarking on an evidence synthesis, it's important to clearly identify your reasons for conducting one. For a list of types of evidence synthesis projects, see the next tab.

How Does a Traditional Literature Review Differ From an Evidence Synthesis?

How does a systematic review differ from a traditional literature review.

One commonly used form of evidence synthesis is a systematic review. This table compares a traditional literature review with a systematic review.

Video: Reproducibility and transparent methods (Video 3:25)

Reporting Standards

There are some reporting standards for evidence syntheses. These can serve as guidelines for protocol and manuscript preparation and journals may require that these standards are followed for the review type that is being employed (e.g. systematic review, scoping review, etc).

- PRISMA checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

- PRISMA-P Standards An updated version of the original PRISMA standards for protocol development.

- PRISMA - ScR Reporting guidelines for scoping reviews and evidence maps

- PRISMA-IPD Standards Extension of the original PRISMA standards for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of individual participant data.

- EQUATOR Network The EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research) Network is an international initiative that seeks to improve the reliability and value of published health research literature by promoting transparent and accurate reporting and wider use of robust reporting guidelines. They provide a list of various standards for reporting in systematic reviews.

Video: Guidelines and reporting standards

PRISMA Flow Diagram

The PRISMA flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of an evidence synthesis. It maps the search (number of records identified), screening (number of records included and excluded), and selection (reasons for exclusion). Many evidence syntheses include a PRISMA flow diagram in the published manuscript.

See below for resources to help you generate your own PRISMA flow diagram.

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Tool

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Word Template

- << Previous: Our Published Reviews and Protocols

- Next: Types of Evidence Synthesis >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2024 2:24 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evidence-synthesis

Synthesizing Research

When combining another author’s ideas with your own, we have talked about how using the can help make sure your points are being adequately argued (if you have not read our handout on the evidence cycle, check it out!). Synthesis takes assertions (statements that describe your claim), evidence (facts and proof from outside sources), and commentary (your connections to why the evidence supports your claim), and blends these processes together to make a cohesive paragraph.

In other words, synthesis encompasses several aspects:

- It is the process of integrating support from more than one source for one idea/argument while also identifying how sources are related to each other and to your main idea.

- It is an acknowledgment of how the source material from several sources address the same question/research topic.

- It is the identification of how important factors (assumptions, interpretations of results, theories, hypothesis, speculations, etc.) relate between separate sources.

TIP: It’s a fruit smoothie!

Think of synthesis as a fruit smoothie that you are creating in your paper. You will have unique parts and flavors in your writing that you will need to blend together to make one tasty, unified drink!

Why Synthesis is Important

- Synthesis integrates information from multiple sources, which shows that you have done the necessary research to engage with a topic more fully.

- Research involves incorporating many sources to understand and/or answer a research question, and discovering these connections between the sources helps you better analyze and understand the conversations surrounding your topic.

- Successful synthesis creates links between your ideas helping your paper “flow” and connect better.

- Synthesis prevents your papers from looking like a list of copied and pasted sources from various authors.

- Synthesis is a higher order process in writing—this is the area where you as a writer get to shine and show your audience your reasoning.

Types of Synthesis

Demonstrates how two or more sources agree with one another.

The collaborative nature of writing tutorials has been discussed by scholars like Andrea Lunsford (1991) and Stephen North (1984). In these essays, they explore the usefulness and the complexities of collaboration between tutors and students in writing center contexts.

Demonstrates how two or more sources support a main point in different ways.

While some scholars like Berlin (1987) have primarily placed their focus on the histories of large, famous universities, other scholars like Yahner and Murdick (1991) have found value in connecting their local histories to contrast or highlight trends found in bigger-name universities.

Accumulation

Demonstrates how one source builds on the idea of another.

Although North’s (1984) essay is fundamental to many writing centers today, Lunsford (1991) takes his ideas a step further by identifying different writing center models and also expanding North’s ideas on how writing centers can help students become better writers.

Demonstrates how one source discusses the effects of another source’s ideas.

While Healy (2001) notes the concerns of having primarily email appointments in writing centers, he also notes that constraints like funding, resources, and time affect how online resources are formed. For writing centers, email is the most economical and practical option for those wanting to offer online services but cannot dedicate the time or money to other online tutoring methods. As a result, in Neaderheiser and Wolfe’s (2009) reveals that of all the online options available in higher education, over 91% of institutions utilize online tutoring through email, meaning these constraints significantly affect the types of services writing centers offer.

Discussing Specific Source Ideas/Arguments

To debate with clarity and precision, you may need to incorporate a quote into your statement. Using can help you to thoroughly introduce your quotes so that they fit in to your paragraph and your argument. Remember that you need to use the to bridge between your ideas and outside source material.

Berlin, J. (1987). Rhetoric and reality: Writing instruction in American colleges, 1900-1985 . Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Boquet, E.H. (2001). “Our little secret”: A history of writing centers, pre- to open admissions. In R.W. Barnett & J.S. Blumner (Eds.), The Allyn and Bacon guide to writing center theory and practice (pp. 42-60). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Carino, P. (1995). Early writing centers: Toward a history. The Writing Center Journal , 15 (2), 103-15.

Healy, D. (2001). From place to space: Perceptual and administrative issues in the online writing center. In R.W. Barnett & J.S. Blumner (Eds.), T he Allyn and Bacon guide to writing center theory and practice (pp. 541-554). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Lunsford, A. (1991). Collaboration, control, and the idea of the writing center. The Writing Center Journal , 12 (1), 310-75.

Neaderheiser, S. & Wolfe, J. (2009). Between technological endorsement and resistance: The state of online writing centers. The Writing Center Journal . 29 (1), 49-75.

North, S. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English , 45 (5), 433-446.

Yahner, W. & Murdick, W. (1991). The evolution of a writing center: 1972-1990. Writing Center Journal , 11 (2), 13-28.

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 1:42 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

- Zondervan Library

- Research Guides

Professional Writing

- Synthesis in Research

- Databases (Articles)

- Tips for Article Searches

- Articles through Interlibrary Loan

- Searching for Books & eBooks

- Books through Interlibrary Loan

- Web Resources

- Finding Sources

- Types of Sources

- Searching Tips and Tricks

- Evaluating Sources

- Writing Help

- Citation Styles

- Citation Tools

What is Synthesis?

Here are some ways to think about synthesis:

Synthesis blends claims, evidence, and your unique insights to create a strong, unified paragraph. Assertions act as the threads, evidence adds texture, and your commentary weaves them together, revealing the connections and why they matter.

Beyond the sum of its parts: Synthesis isn't just adding one and one. It's recognizing how multiple sources, through their connections and relationships, create a deeper understanding than any single one could achieve.

Synthesis isn't just about what sources say, it's about how they say it. By digging into assumptions, interpretations, and even speculations, you uncover hidden connections and build a more nuanced picture.

Whereas analyzing involves dismantling a whole to understand its parts and their relationships, synthesizing involves collecting diverse parts and weaving them together to form a novel whole. Reading is an automatic synthesis process, where we connect incoming information with our existing knowledge, constructing a new, expanded "whole" of our understanding in the subject area.

You've been doing synthesis for a long time, the key now is being aware and organized in the process.

- Sharpen your research direction: Be clear about your main objective. This guides your reading and analysis to make the most of your time.

- Build a strong foundation: Use trusted sources like peer-reviewed journals, academic books, and reputable websites. Diverse sources add strength and credibility to your research.

Then Organize your Research:

- Dig deep and connect the dots: While reading, highlight key ideas, arguments, and evidence. Mark potential links between sources, like overlaps or contrasting arguments.

- Organize ideas by neighborhood: Group sources with similar themes or angles on your topic. This will show you where sources agree or clash, helping you build a nuanced understanding.

- Build a mind map of your research: Create a table of key themes, listing key points from each source and how they connect. This visual map can reveal patterns and identify any missing pieces in your research.

Finally, Build your synthesis:

- Lay out the groundwork: Kick off each section with a clear claim or theme to guide your analysis.

- Weave sources together: Briefly explain what each source brings to the table, smoothly connecting their ideas with transitions and language.

- Embrace the debate: Don't tiptoe around differences. Point out where sources agree or clash, and explore possible reasons for these discrepancies.

- Dig deeper than surface facts: Don't just parrot findings. Explain what they mean and how they impact your topic.

- Add your voice to the mix: Go beyond reporting. Analyze, evaluate, and draw conclusions based on your synthesis. What does this research tell us?

Tips & Tricks:

- Let the evidence do the talking: Back up your claims with concrete details, quotes, and examples from your sources. No need for personal opinions, just let the facts speak for themselves.

- Play fair with opposing views: Be objective and present different perspectives without showing favoritism. Even if you disagree, let readers see the other side of the coin.

- Give credit where credit is due: Make sure your sources get the recognition they deserve with proper citations, following your chosen style guide consistently.

- Polish your masterpiece: Take some time to revise and proofread your work. Ensure your arguments are crystal clear, concise, and well-supported by the evidence.

- Embrace the growth mindset: Remember, research and synthesis are a journey, not a destination. Keep refining your analysis as you learn more and encounter new information. The more you explore, the deeper your understanding will become.

Demonstrates how two or more sources agree with one another.

The collaborative nature of writing tutorials has been discussed by scholars like Andrea Lunsford (1991) and Stephen North (1984). In these essays, they explore the usefulness and the complexities of collaboration between tutors and students in writing center contexts.

Demonstrates how two or more sources support a main point in different ways.

While some scholars like Berlin (1987) have primarily placed their focus on the histories of large, famous universities, other scholars like Yahner and Murdick (1991) have found value in connecting their local histories to contrast or highlight trends found in bigger-name universities.

Accumulation

Demonstrates how one source builds on the idea of another.

Although North’s (1984) essay is fundamental to many writing centers today, Lunsford (1991) takes his ideas a step further by identifying different writing center models and also expanding North’s ideas on how writing centers can help students become better writers.

Demonstrates how one source discusses the effects of another source’s ideas.

While Healy (2001) notes the concerns of having primarily email appointments in writing centers, he also notes that constraints like funding, resources, and time affect how online resources are formed. For writing centers, email is the most economical and practical option for those wanting to offer online services but cannot dedicate the time or money to other online tutoring methods. As a result, in Neaderheiser and Wolfe’s (2009) reveals that of all the online options available in higher education, over 91% of institutions utilize online tutoring through email, meaning these constraints significantly affect the types of services writing centers offer.

[Taken from University of Illinois, "Synthesizing Research "]

The Writing Center at University of Arizona showcases how to create and use a synthesis matrix when reading sources and taking notes. It is a great, organized way to synthesize your research.

You can find it here .

Creativity in researching begins with developing a thorough understanding of your research topic; this is fundamental to streamlining the process and enriching your findings. This entails delving into its intricacies—exploring both similarities and divergences with related subject areas. Consider the most appropriate sources (and types of sources) for your study, critically engaging with all perspectives, and acknowledging the complex interplay between its positives, negatives, and broader connections.

Embrace interdisciplinary exploration. Delve deeper through transdisciplinary analysis, venturing beyond the immediate field to parallel professions and diverse academic arenas. Consider comparative studies from other cultural contexts to add fresh perspectives.

For example, researching rule changes in the NFL demands a nuanced approach. One might investigate the link to Traumatic Brain Injury, analyze case studies of impacted players, and even examine rule adjustments in other sports, drawing insights from their rationale and outcomes.

Remember, librarians are invaluable partners in this process. Their expertise in creative thinking and resource navigation can unlock a wealth of information, guiding you towards fruitful discoveries.

- << Previous: Evaluating Sources

- Next: Writing & Citing >>

- Last Updated: Oct 15, 2024 3:47 PM

- URL: https://library.taylor.edu/professional-writing

Hours Policies Support Services

WorldCat Research Guides Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

Staff Directory Email the Library

Blackboard My Library Account My Taylor

Zondervan Library Taylor University 1846 Main Street, Upland, IN 46989 (765) 998-4357

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

Synthesis Visualization

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

Approaches to synthesis.

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2024 11:48 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Summarizing and synthesizing

Part 3: Chapter 10

Questions to consider

A. What distinguishes a synthesis from a summary?

B. How much “author voice” is present relative to source material?

C. What is the nature of the material contributed to a synthesis by the author?

The purpose of synthesizing

Combining separate elements into a whole is the basic dictionary definition of synthesis. It is a way to make connections between numerous and varied source materials. A literature review presents a synthesis of material, grouped by topic, to create a broad and comprehensive view of the literature relevant to a research question. Here, the research questions are often modified to the realities of the information, or information may be selected or rejected based on relevance. This organizational approach helps in understanding the information and structuring the review.

Because research is an iterative process, it is not unusual to go back and search information sources for more material while remaining within the parameters of the topic and research questions. It can be difficult to cope with “everything” on a topic; the need to carefully select based on relevancy is ongoing.

The synthesis must demonstrate a critical analysis of the papers assembled as well as an integration of the analytical results. All included sources must be directly relevant and the synthesis writer should make a significant contribution. As part of an introduction or literature review, the syntheses not only illustrate the evolution of research on an issue, but the writer’s own commentary on what this information means .

Many writers begin the synthesis process by creating a grid, table, or an outline organizing summaries of the source material to discover or extend common themes with the collection. The summary grid or outline provides a researcher an overview to compare, contrast and otherwise investigate the relationships and potential deficiencies. [1]

Language in Action

- How many different sources are used in the synthesis (excerpted from “Does international work experience pay off? The relationship between international work experience, employability and career success: A 30-country, multi-industry study” ) that follows? (IWE: international work experience)

- How do the sources contribute to the message of the paragraph?

- What are the elements of a strong synthesis?

- What information is contributed by the authors themselves?

1 Taking stock of the literature, several characteristics stand out that limit our understanding of the IWE−career success relationship. 2 First, many studies focus on individuals soon after their return from an IWE or while they are still expatriates (Kraimer et al., 2016). 3 These findings may therefore report results pertaining to a short-lived career phase. 4 Given that careers develop over time, and success, especially in the form of promotions and salary increases, may take some time to materialise, it is perhaps not surprising that findings have been mixed. 5 Some authors note that there are short-term, career-related costs of IWE and the career ‘payoff’ occurs after a time lag for which cross-sectional studies may not account (Benson & Pattie, 2008; Biemann & Braakmann, 2013). 6 Second, the majority of studies use samples consisting only of individuals with IWE (Jokinen et al., 2008; Stahl et al., 2009; Suutari et al., 2018). 7 Large samples that include both individuals with and without IWE are needed to provide the variance needed to identify the influence of IWE on career success (e.g., Andresen & Biemann, 2013). 8 Third, studies tend to focus on the baseline question of whether IWE or IWE-specific characteristics (e.g., host country, developmental nature of assignment) are related to a particular career success variable (e.g., Bücker et al., 2016; Jokinen et al., 2008; Stahl et al., 2009). 9 Yet there may be an indirect relationship between IWE and career success (Zhu et al., 2016). 10 More complex models that examine the possible impact of mediating variables are thus needed (Mayrhofer et al., 2012). 11 Lastly, while studies acknowledge that findings from specific countries/nationalities, industries, organisations or occupational roles may not be transferable to all individuals with IWE (Biemann & Braakmann, 2013; Schmid & Wurster, 2017; Suutari et al., 2018), the specific role of national context is rarely considered. 12 However, careers do not develop in a vacuum. 13 Contextual factors play an important role in moderating the career impact of various career experiences such as IWE (Shen et al., 2015). [2]

Organizing the material

Beginning the synthesis process by creating a grid, table, or an outline for summaries of sources offers an overview of the material along with findings and common themes. The summary, grid, or outline will allow quick comparison of the material and reveal gaps in information. [3]

The process of building a “library” from which to draw information is critical in developing the defense, argument or justification of a research study. While field and laboratory research is often engaging and interesting, understanding the backstory and presenting it as an explanation of a proposed method or approach is essential in obtaining funding and/or the necessary committee approval.

Returning to the foundational skill of producing a summary , and combining that with the maintenance of a system to manage source material and details, an annotated bibliography can be both an intellectual structure that reveals connections among sources and a means to initiating – on a manageable level – the arduous writing.

Example – Two entries from an annotated bibliography

Nafisi, A. (2003). Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books. New York: Random House.

A brave teacher in Iran met with seven of her most committed female students to discuss forbidden Western classics over the course of a couple of years, while Islamic morality squads staged raids, universities fell under the control of fundamentalists, and artistic expression was suppressed. This powerful memoir weaves the stories of these women with those of the characters of Jane Austen, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Henry James, and Vladimir Nabokov and extols the liberating power of literature.

Obama, B. (2007). Dreams from My Father. New York: Random House.

This autobiography extends from a childhood in numerous locations with a variety of caregivers (a single parent, grandparents, boarding school) to an exploration of individual heritage and family in Africa, revealing a broken/blended family, abandonment and reconnection, and unresolved endings. Obama describes his existence on the margins of society, the racial tension within his biracial family, and his own identity conflict and turmoil.

Using a chart or grid

Below is a model of a basic table for organizing source material.

Exercise #1

- Read the excerpts from three sources below. Determine the common topic and themes.

- Complete a table like the one above using information from these three sources.

1 Completion of a dissertation is an intense activity. 2 For both groups [completers and non-], the advisor and the student’s family and spouse served as the major source of emotional support and are most heavily invested in the dissertation. 3 Other students and the balance of the dissertation committee were rated as providing little support. 4 Since work on the dissertation is highly individual and there are no College organized groups of students working on the dissertation that meet regularly, the process can be a lonely one. 5 Great independence and a strong sense of direction is required. 6 Although many students rated themselves as having little experience with research, students are dependent on their own resources and on those closest to them. 7 It was noted that graduates rated emotional support from all sources more highly than students rated it. 8 This may be a significant factor associated with dissertation completion.

9 The scales and checklists suggest that there are identifiable differences between the two groups. 10 Since the differences are not great, the implications are that with some modification of procedures, a greater proportion of students can become graduates. 11 Emotional support, financial support, experience with research, familiarity with university and college dissertation requirements, and ready access to university resources and advisors may be factors to build into a modified system to achieve a greater proportion of graduates.

Kluever, R., Green, K. E., Lenz, K., Miller, M. M., & Katz, E. (1995). Graduates and ABDs in colleges of education: Characteristics and implications for the structure of doctoral programs. In Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. San Francisco, CA. Retrieved from the ERIC database .

1 In this writing group, students evaluated their goal achievement, reflected on the obstacles before them, and set new targets. 2 This process encouraged them to achieve their goals, and they could modify or start a new target instead of giving up. 3 The students also received positive feedback and support from other members of the group. 4 This positive environment helped the students view failure as part of the nature of writing a thesis.

5 On the other hand, daily monitoring encouraged the students to focus more on the process and less on the outcome; therefore, they experienced daily success instead of feeling a failure when the goals were not achievable.

Patria, B., & Laili, L. (2021). Writing group program reduces academic procrastination: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Psychology , 9 (1), 1–157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00665-9

1 The promotion of awareness of the tension between core qualities and ideals, and inner obstacles, in particular limiting thoughts, in combination with guidelines for overcoming the tension by being aware of one’s ideals and character strengths is characteristic of the core reflection approach and appears to have a strong potential for diminishing academic procrastination behavior. 2 These results make clear that a positive psychological approach focusing on strengths can be beneficial for diminishing students’ academic procrastination. 3 In particular, supporting and regenerating character strengths can be an effective approach for overcoming academic procrastination.

Visser, L., Schoonenboom, J., & Korthagen, F. A. J. (2017). A Field Experimental Design of a Strengths-Based Training to Overcome Academic Procrastination: Short- and Long-Term Effect. Frontiers in Psychology , 8, 1949–1949. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01949

A topical outline is another tool writers may use to organize their material. It begins as a simple list of facts gleaned from various sources and arranged by category. [4]

A topical outline might look like this:

a. fact #1/source #1

b. fact #2/source #1

a. fact #3/source #1

b. fact #4/source #2

Exercise #2

Identify relevant facts presented by the three sources in Exercise #1. Determine the relationships between them. Consider how to categorize and arrange them in order to support or extend a related concept.

Exercise #3

A word about primary sources

Primary source material is information conveyed by the author(s) of the publication. The information they use to support or extend their ideas – their source material – is secondary source material for their readers. Anything considered for inclusion in research writing should be derived from primary sources. When writers find very valuable material cited, they retrieve the original work rather than paraphrase what has already been paraphrased.

Example – Synthesis

The excerpted synthesis below is the work of Joellen E. Coryell, Maria Cinque, Monica Fedeli, Angelina Lapina Salazar, and Concetta Tino. The two primary sources they use in the paragraph were authored by Niehaus and Williams (2016), and Urban, Navarro, and Borron (2017). Because research writers are urged to only use primary sources, further investigation into the paper of Niehaus and Williams would be required in order to use their work as a source. As discussed in Identifying and deploying source material , an effective strategy in finding useful sources is to explore the references of particularly valuable articles or papers.

University Teaching in Global Times: Perspectives of Italian University Faculty on Teaching International Graduate Students

1 Other researchers (Niehaus & Williams, 2016; Urban et al., 2017) offered analyses of faculty’s experiences participating in various training programs for internationalization of their courses. 2 Niehaus and Williams (2016) studied a 4-year global faculty development program aimed at transforming faculty perspectives and internationalizing the curriculum. 3 Findings indicated that participants integrated international and comparative topics to support their learners’ development of global perspectives. 4 They worked to integrate international students’ viewpoints on research, and participants reported professional and personal gains defined by expanded professional networks of faculty members and higher standing that comes with teaching international students. 5 Similarly, Urban et al. (2017) reported findings from a training program that assisted teaching staff to internationalize their courses. 6 The program included a 12-day field trip to a different country. 7 Semi-structured interviews with faculty members, 6 years after participating in the program, affirmed updated course content, new and broader perspectives, and a supportive environment for implementing the internationalized courses and teaching activities.

Primary source:

Coryell, J. E., Cinque, M., Fedeli, M., Lapina Salazar, A., & Tino, C. (2022). University Teaching in Global Times: Perspectives of Italian University Faculty on Teaching International Graduate Students. Journal of Studies in International Education , 26(3), 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315321990749

Secondary sources:

Niehaus, E., & Williams, L. (2016). Faculty Transformation in Curriculum Transformation: The Role of Faculty Development in Campus Internationalization. Innovative Higher Education, 41(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-015-9334-7

Urban, E., Navarro, M., & Borron, A. (2017). Long-term Impacts of a Faculty Development Program for the Internationalization of Curriculum in Higher Education. Journal of Agricultural Education, 58(3), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2017.03219

Experienced researchers often have a strong hypothesis and search for evidence that supports or extends this. However, students often learn about their topic during the research process and formulate a hypothesis as they learn what is established in the field on their topic. Both approaches are acceptable, as is a hybrid.

Discovery phase

Researchers typically begin by paraphrasing any important facts or arguments, tracking their discoveries in a table, outline or spreadsheet. Some good examples include definitions of concepts, statistics regarding relevance, and empirical evidence about the key variables in the research question. The original source information (citations in the appropriate style and format) is as important as the content under consideration. As shown in the model syntheses here, multiple sources often support a common finding.

Evaluation and analysis phase

A strong synthesis must demonstrate a critical analysis of the papers as well as an integration of analytical results; this is the voice of the synthesis writer, interpreting the relationships of the cited works as they are assembled. Each paper under consideration should be critically evaluated according to its relevancy to the topic and the quality of its content.

Writers first establish relationships between cited concepts and facts by continuously considering these questions:

A. Where are the similarities within each topic or subtopic?

B. Where are the differences?

C. Are the differences methodological or theoretical in nature?

The answers will produce general conclusions for each topic or subtopic as the entire group of studies relate to it.

As the material is organized logically using a grid, table or outline, the most logical order must be determined. That order might be from general to specific, sequential or chronological, or from cause to result. [5]

Review and Reinforce

Summarizing and synthesizing are key building blocks in research writing. Read with an awareness of

A. what information has been added for support;

B. what the source of that information is; and

C. how the information was incorporated (quotations or summaries) and documented (integral or parenthetical citations) into the material.

Research writing is a process itself that synthesizes new information, stylistic tendencies, and established conventions with the background knowledge of the researcher.

Media Attributions

- chameleon © Frontierofficial is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 5182866555_18ae623262_c © rarebeasts is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Adapted from Frederiksen, L., & Phelps, S. F. (2017). Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students . Open Textbook Library. ↵

- Andresen, M., Lazarova, M., Apospori, E., Cotton, R., Bosak, J., Dickmann, M., Kaše, R., & Smale, A. (2022). Does international work experience pay off? The relationship between international work experience, employability and career success: A 30-country, multi-industry study. Human Resource Management Journal , 32(3), 698–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12423 ↵

- Adapted from DeCarlo, M. (2018). Scientific Inquiry in Social Work . Open Textbook Library. ↵

- Adapted from DeCarlo, M. (2018). Scientific Inquiry in Social Work. Open Textbook Library. ↵

- Adapted from Frederiksen, L., & Phelps, S. F. (2017). Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students . Open Textbook Library. ↵

combining separate elements into a whole, generally new, result

a condensed version of a longer text

a list of sources on a particular topic, formatted in the field specific format, which includes a brief summary of each reference

a reference presenting their own data and information

reference material used and cited by a primary source

Sourcing, summarizing, and synthesizing: Skills for effective research writing Copyright © 2023 by Wendy L. McBride is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Literature Review Basics

- What is a Literature Review?

- Synthesizing Research

- Using Research & Synthesis Tables

- Additional Resources

Synthesis: What is it?

First, let's be perfectly clear about what synthesizing your research isn't :

- - It isn't just summarizing the material you read

- - It isn't generating a collection of annotations or comments (like an annotated bibliography)

- - It isn't compiling a report on every single thing ever written in relation to your topic

When you synthesize your research, your job is to help your reader understand the current state of the conversation on your topic, relative to your research question. That may include doing the following:

- - Selecting and using representative work on the topic

- - Identifying and discussing trends in published data or results

- - Identifying and explaining the impact of common features (study populations, interventions, etc.) that appear frequently in the literature

- - Explaining controversies, disputes, or central issues in the literature that are relevant to your research question

- - Identifying gaps in the literature, where more research is needed

- - Establishing the discussion to which your own research contributes and demonstrating the value of your contribution

Essentially, you're telling your reader where they are (and where you are) in the scholarly conversation about your project.

Synthesis: How do I do it?

Synthesis, step by step.

This is what you need to do before you write your review.

- Identify and clearly describe your research question (you may find the Formulating PICOT Questions table at the Additional Resources tab helpful).

- Collect sources relevant to your research question.

- Organize and describe the sources you've found -- your job is to identify what types of sources you've collected (reviews, clinical trials, etc.), identify their purpose (what are they measuring, testing, or trying to discover?), determine the level of evidence they represent (see the Levels of Evidence table at the Additional Resources tab ), and briefly explain their major findings . Use a Research Table to document this step.

- Study the information you've put in your Research Table and examine your collected sources, looking for similarities and differences . Pay particular attention to populations , methods (especially relative to levels of evidence), and findings .

- Analyze what you learn in (4) using a tool like a Synthesis Table. Your goal is to identify relevant themes, trends, gaps, and issues in the research. Your literature review will collect the results of this analysis and explain them in relation to your research question.

Analysis tips

- - Sometimes, what you don't find in the literature is as important as what you do find -- look for questions that the existing research hasn't answered yet.

- - If any of the sources you've collected refer to or respond to each other, keep an eye on how they're related -- it may provide a clue as to whether or not study results have been successfully replicated.

- - Sorting your collected sources by level of evidence can provide valuable insight into how a particular topic has been covered, and it may help you to identify gaps worth addressing in your own work.

- << Previous: What is a Literature Review?

- Next: Using Research & Synthesis Tables >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 12:06 PM

- URL: https://usi.libguides.com/literature-review-basics

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Evidence-Based Arguments: Synthesis

Paraphrasing and synthesis.

Synthesis is important in scholarly writing as it is the combination of ideas on a given topic or subject area. Synthesis is different from summary. Summary consists of a brief description of one idea, piece of text, etc. Synthesis involves combining ideas together.

Summary: Overview of important general information in your own words and sentence structure. Paraphrase: Articulation of a specific passage or idea in your own words and sentence structure. Synthesis: New interpretation of summarized or paraphrased details in your own words and sentence structure.