10 Strategies to Make Peer Review Meaningful for Students

EdTech , Teaching | 0 comments

“A peer review can be a very mysterious process, and certainly a scary one, which is why we need to talk more about how it’s done.”- Wyn Kelley, Lecturer, Literature, MIT

One of the most powerful means of encouraging student engagement and learning is through peer review, or guiding students to both critique and encourage each other as they develop speeches, presentations, and paper drafts. Peer review activities enable students to seek guidance from others, and to gain an objective idea of the quality of their thinking and their ability to organize and present their own thoughts. Peer review, effectively, is what enables students to become better thinkers and communicators.

For some students, it can be difficult to provide concrete, actionable, and descriptive feedback to their peers. As Thomas Levenson, Professor in Writing and Humanistic Studies, MIT notes, many students are uncomfortable critiquing peers. To make sure students know that peer assessment should be constructive, he tells students that “they only get to say, ‘I liked it’ once per class.” It’s important that instructors give students a set of prompts that guide students, and enable them to see how they can be most productive and explicit in giving feedback. Grant Wiggins of Authentic Education , suggests that helpful feedback follows the following 7 criteria. It is 1) goal-referenced; 2) transparent; 3) actionable; 4) user-friendly; 5) timely; 6) ongoing; and 7) consistent. Peer feedback should, above all, provide students with a sense of closure as to where to go next.

Video: “No One Writes Alone” from MIT Video

At Acclaim, instructors from Communication and Public Speaking, as well as Entrepreneurship, Science and Digital Storytelling courses, have shared some of the prompts they send to students as they ask them to give peer evaluations of presentations. The following are 10 prompts for peer review, compiled from assignments across the disciplines; with 5 prompts on content and presentation skills, and 5 on technology:

CONTENT AND PRESENTATION:

1. What is the speaker’s main point?

2. How is the speech structured? Does the speaker have a distinct introduction and conclusion? Where does he signpost his argument?

3. How does the speaker use evidence and analysis? Do examples elaborate on facts? Can you tell the difference between broad ideas and details?

4. Is the amount of time the speaker spends on each point proportional to its importance to his argument?

5. How does the speaker engage the audience? Some things to comment on: voice level, tone, level of interest/excitement in subject, eye contact, responses/attitudes towards questions, approachability. How did his movement and gestures coordinate with content?

VISUALS/TECHNOLOGY

1. How well did the speaker coordinate his timing with the visuals?

2. Were the visuals relevant to the speech, and if so, how did they enhance it? Did the speaker adequately explain them?

3. Were the visuals clear, independently of the speaker? Voice any ideas about animations or graphics.

4. Did the speaker seem comfortable with the technology he/she used? How does the speaker respond to technological difficulties (if there were any?)

5. Are there any additional visuals that might have helped to enhance the speakers point?

While these prompts can be used in any context, real or online, they can be especially effective when both the presenters, as well as the reviewers, have the “the time to adequately reflect on the content presented and technology used before delivering feedback,” according to Robin Cooper , Professor of Biology and Neuroscience, University of Kentucky. Student feedback, when delivered in written form online, can take the pressure and discomfort off of class communication. Moreover, we’ve found that when students have the chance to review their own recorded presentations, the suggestions of their peers become increasingly actionable. For more great reading and suggestions on peer review and assessment, check out the following resources:

Annie Murphy Paul: “ From the Brilliant Report: How to Give Good Feedback .”

Cynthia C. Choi and Hsiang-ju Ho: “ Exploring New Literacies in Online Peer-Learning Environments ”

Gale Morris, “ Using Peer Review to Improve Student Writing .”

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

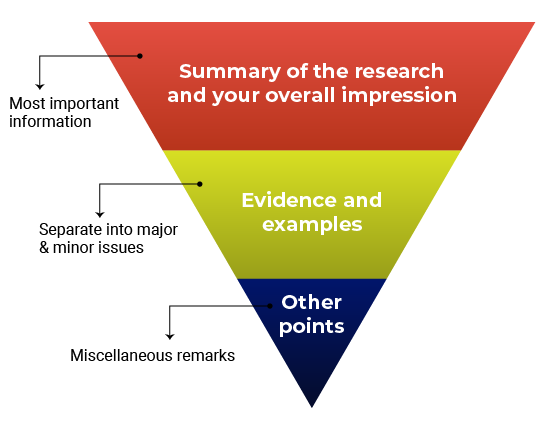

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Remote Peer Review Strategies

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

For many writing teachers, effective peer review is just as important a skill as crafting an outline or writing a clear thesis statement. Unfortunately, remote teaching poses some challenges for teachers who use typical in-person peer review strategies. However, there are a number of ways to adapt what normally occurs in the classroom to work online. These strategies, of course, depend on the level of your students and the equipment they have available to them. Some you may be able to use as presented, some may need to be adapted before they'll work for your class, and some may not be possible at all. Moreover, because a wide variety of learning management systems (LMS) are available to teachers today, it's impossible to provide instructions that will work for every teacher's situation. Feel free, then, to modify the general strategies below as needed to fit the needs of your course.

Provide Support for First-time Peer Reviewers

If you need to teach students how to do peer review for the first time, it is a good idea to help them understand how peer review functions in the writing process, or at least show them some examples of what effective peer review looks like. In this case, consider using resources provided by the Eli Review at Michigan State University. The Review's Describe-Evaluate-Suggest framework video , for example, gives students the language to talk about peer review with their classmates, and the advice in the video can be adapted to a variety of educational contexts. Providing students frameworks that define the peer review task (like this one) can help guide them away from shallow, negative commentary and toward the sort of deep, constructive insights that make peer review more useful.

You may also consider making use of the OWL's own peer review presentation , which was created with a student audience in mind.

Make Your Expectations Clear

One of the biggest challenges of remote teaching is communicating expectations. Whereas questions about assignments can be addressed as they emerge in physical classrooms, teachers of online courses benefit from trying to anticipate questions in advance. For peer review, giving students clear targets for acceptable amounts of feedback can help answer questions about how much they need to do to succeed and how much feedback is enough. For instance, these sorts of instructions might the following form:

"You should write at least five substantive comments in-text using the comment function on Google Docs, and you should write a paragraph of feedback at the end of the document that is at least five sentences."

The drawback to this strategy, however, is that students may reach the target you have set and promptly stop. Nevertheless, setting these expectations makes it more likely that students receive at least a certain amount of useful feedback from their partners. Similarly, in a physical classroom, it is simple to remind students what they should be looking for in a peer's work. Online, however, these expectations need to be frontloaded. Checklists, questions, and frameworks for how to provide commentary (like the Describe-Evaluate-Suggest framework above) help keep students on track.

Another strategy that can augment a prompt from the instructor is to have students include a memo to their peers with their draft that discusses problem areas that the student is worried about, areas they are confident about, and questions they have.

Use Digital Platforms to Facilitate Collaboration

Depending on students' access to equipment and the learning management system your class uses, you may have a variety of options for how to structure the peer review. LMSs with robust grouping and discussion board tools can allow you to initiate peer review between just a few students or between all students in the class. Similarly, students can attach their work to an initial discussion board post, allowing others to reply with holistic commentary in subsequent posts or attachments, depending on what you'd like them to do. If you use a platform like Google Docs, you can also have students take advantage of commenting features or even suggested edit features to demonstrate how they might rework a sentence, etc. If students have microphones, they could even record audio as they read through a piece to give reader reaction feedback in the moment.

Whatever strategy you choose to use, you should ensure that all student work is visible to you, whether in the learning management system as text comments or file attachments or in the form of cloud-saved documents shared with you as well as with their partners. Even if you're not grading feedback, you may need access to these documents later in case students have a dispute.

Sample Peer Review Assignment

Here is an example of a peer review assignment from an online writing class. This assignment uses threaded discussion boards to group students:

For peer review, you'll review the work of two of your classmates. In this thread, upload your documents as attachments to your first post.

Please offer at least ten substantive comments on your partners' documents using the comments function in Microsoft Word. You can do this by clicking Review >> New Comment. Save a copy of the document on your own computer, make comments, and then upload the new document here. Alternatively, you can post a numbered list of specific comments that point your partner to the section you're referring to.

I have uploaded a rubric for the resume and cover letter deliverables for Unit 1 to this week's page. Once you have made substantive in-text comments on your partner's documents, use the rubric to assess their work. You're not grading the document, but the categories and qualities listed on the rubric should help you structure your comments. Using your in-text comments and your rubric-based assessment, finish off the peer review by writing 1-2 paragraphs (using the DES framework) summarizing your feedback. When you are done, you should see a mix of praise for what your partner is doing well and constructive criticism to help them improve.

Please keep in mind that you are engaging in a conversation about your classmate's ideas. Don't focus on grammar, mechanics and spelling — instead, highlight positive aspects of the draft, and then provide constructive feedback and suggestions on what could be improved or changed, following the Describe - Evaluate - Suggest framework we read about. I will grade peer review as part of the Unit 1 total. Commenting only "good job" or similar, giving only critical comments, or commenting only on grammar, mechanics and spelling will result in deducted points.

Post your drafts by Friday, 6/14, 11:59pm EST. Post comments back to your classmates by Monday, 6/17, 11:59pm EST.

40 Peer Review

Learning Objectives

- Identify benefits to collaborative work.

- Examine cultural considerations for offering feedback.

- Use a systematic process for offering feedback.

- Use language constructive language to offer feedback.

- Use feedback to make edits to the speech outline.

- Use feedback to practice speech.

Collaborative work = Stronger Finished Product

The benefits of collaborative work are numerous. Peer review allows us to share our work and receive feedback that will help us to strengthen our final product.

Important benefits for your speech development are:

- Learning from one another: Learning is collaborative. We can learn just as much from one another as we can from course materials. We have different experiences and interpret course concepts in different ways. Peer review allows us to share these ideas.

- Clarified goals: When offering review and editing suggestions, we are forced to focus on the assignment goals. This focus allows us to catch things they may have otherwise missed.

- Strengthen speechwriting skills: The process provides opportunities for us to identify and articulate weaknesses in a peer’s outline. When doing this, we are learning at a deeper level and can use our own feedback to strengthen our outlines.

- Idea Clarification: As students explain ideas to classmates, they can identify where content development may be lacking. This provides opportunities to strengthen the outline content for audience clarification.

- Minimizes Procrastination: Often students will wait until the last minute to prepare their speech outline. The peer review process forces students to prepare in enough time to work through edits and revisions which are necessary for effective speech development.

- Builds Confidence: Public speaking is a nerve-wracking event for many of us. Having others validate our work and provide suggestions for improvement helps us to build confidence that our final product is strong!

Engaging in Peer Review

The peer-review process can be an exceptional tool if you engage in it effectively. Below are tips…

- Read/Listen first: Read through the entire outline or watch the entire speech before offering comments. Once you get a good idea of the content then you can go back through it and give feedback.

- Ask questions: Clarifying questions can provide you with information about your partner’s thought process so you can give more effective feedback. Also, questions can provide your partner with an opportunity to think through how they can better explain concepts or ideas in their speech. Questions are a great learning tool.

- Use the course materials: Use the readings, assignment descriptions, and rubrics to structure your feedback. This will help you focus on useful feedback. Look for both format and content issues. Both of these will be necessary for a successful outline or speech delivery.

- Mix criticism and praise: Knowing our strengths and our weaknesses are equally important for our speech development. Offer feedback on what you think they did well and what you think they need to improve.

- Describe what you are reading or hearing and your understanding of the content (paraphrase and clarify, “this is what I am hearing…”).

- Evaluate the outline or speech based on the rubric, assignment sheet, or class material.

- Suggest steps for improvement.

- Write out your thoughts: Even if you are talking through your feedback, offering written feedback will be more helpful when your partner is revising the work.

Effective approaches to offering feedback

- Use phrases such as, “From what I understand, in this section you are…”, “It seems to me that the focus of this section is…”, “I am not sure I understand the main point here. It seems to me that…”

- Ask questions when you are uncertain about something. “What is the purpose of this section? ” or “Why is it important to your paper? ” or “How do these points connect? or “What do you mean by…?”

- Be specific about content, speech parts, format, etc. The more specific you are, the more helpful you are. “In this section, it appears…” or “This comment is…” or “I am not certain how this support connects….”

- Remember to praise strengths. “Your use of language is great” or “You have strong introduction elements.”

Techniques of Constructive Criticism

The goal of constructive criticism is to improve the behavior or the behavioral results of a person, while consciously avoiding personal attacks and blaming. This kind of criticism is carefully framed in language acceptable to the target person, often acknowledging that the critics themselves could be wrong.

Insulting and hostile language is avoided, and phrases used are like “I feel…” and “It’s my understanding that…” and so on. Constructive critics try to stand in the shoes of the person being criticized and consider what things would look like from their perspective.

Effective criticism should be:

- Positively intended, and appropriately motivated: you are not only sending back messages about how you are receiving the other’s message but about how you feel about the other person and your relationship with him/her. Keeping this in mind will help you to construct effective critiques.

- Specific: allowing the individual to know exactly what behavior is to be considered.

- Objective, so that the recipient not only gets the message but is willing to do something about it. If your criticism is objective, it is much harder to resist.

- Constructive, consciously avoiding personal attacks and blaming, insulting language, and hostile language are avoided. Avoiding evaluative language—such as “you are wrong” or “that idea was stupid”—reduces the need for the receiver to respond defensively.

As the name suggests, the consistent and central notion is that the criticism must have the aim of constructing, scaffolding, or improving a situation, a goal that is usually subverted by the use of hostile language or personal attacks.

Effective criticism can change what people think and do; thus, criticism is the birthplace of change. Effective criticism can also be liberating. It can fight ideas that keep people down with ideas that unlock new opportunities, while consciously avoiding personal attacks and blaming.

Cultural Groups Approach Criticism with Different Styles

A culture is a system of attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that form distinctive ways of life. Different cultural groups have different ways of communicating both verbally and non-verbally. While globalization and media have moderated many of the traditional differences for younger audiences, it is wise to consider five important areas where cultural differences could play a role when giving and receiving criticism:

- Verbal style in low and high context cultures

- Instrumental versus affective message responsibility

- Collectivism and individualism in cultures

- “Face”

- Eye contact

Verbal Style in Low and High Context Cultures

In low context cultures such as in the United States and Germany, there is an expectation that people will say what is on their mind directly; they will not “beat around the bush.” In high context cultures, such as in Japan and China, people are more likely to use indirect speech, hints, and subtle suggestions to convey meaning.

Responsibility for Effectively Conveying a Message

Is the speaker responsible for conveying a message, or the audience? The instrumental style of speaking is sender-orientated; the burden is on the speaker to make him or herself understood. The affective style is receiver-orientated and places more responsibility on the listener. With this style, the listener must pay attention to verbal, nonverbal, and relationship clues in order to understand the message. Chinese, Japanese, and many Native American cultures are affective cultures, whereas the American culture is more instrumental. Think about sitting in your college classroom listening to a lecturer. If you do not understand the material, where does the responsibility lie? In the United States, students believe that it is up to the professor to communicate the material to the students. However, when posing this question to a group of Chinese students, you may encounter a different sense of responsibility. Listeners who were raised in a more affective environment respond with “no, it’s not you; it is our job to try harder.” These kinds of students accept responsibility as listeners who work to understand the speaker.

Collectivism and Individualism

Are the speaker and listeners from collectivist or individualistic cultures? When a person or culture has a collective orientation they place the needs and interests of the group above individual desires or motivations. In contrast, cultures with individualistic orientations view the self as most important. Each person is viewed as responsible for his or her own success or failure in life. When you provide feedback or criticism if you are from an individualistic culture, you may speak directly to one individual and that individual will be responsible. However, if you are speaking with someone from a culture which is more collectivist, your feedback may be viewed as shared by all the members of the same group, who may assume responsibility for the actions of each other.

Face is usually thought of as a sense of self-worth, especially in the eyes of others. Research with Chinese university students showed that they view a loss of face as a failure to measure up to one’s sense of self-esteem or what is expected by others. In more individualistic cultures, speakers and listeners are concerned with maintaining their own face and not so much focused on that of others. However, in an intercultural situation involving collectivist cultures, the speaker should not only be concerned with maintaining his or her own face, but also that of the listeners.

Receiving Feedback

You will receive feedback from a peer to revise your speech content and delivery. Accepting any criticism at all, even effective and potentially helpful criticism, can be difficult. Ideally, effective criticism is positive, specific, objective, and constructive. There is an art to being truly effective with criticism; a critic can have good intentions but poor delivery, for example, “I don’t know why my girlfriend keeps getting mad when I tell her to stop eating so many french fries; I’m just concerned about her weight!” For criticism to be truly effective, it must have the goal of improving a situation, without using hostile language or involving personal attacks.

Receiving criticism is a listening skill that is valuable in many situations throughout life: at school, at home, and in the workplace. Since it is not always easy to do, here are three things that will help to receive effective criticism gracefully:

- Accept that you are not perfect . If you begin every task thinking that nothing will ever go wrong, you are fooling yourself. You will make mistakes. The important thing is to learn from mistakes .

- Be open-minded to the fact that others may see something that you do not . Even if you do not agree with the criticism, others may be seeing something that you are not even aware of. If they say that you are negative or overbearing, and you do not feel that you are, well, you might be and are just not able to see it. Allow for the fact that others may be right, and use that possibility to look within yourself.

- Seek clarity about aspects of a critique that you are not sure of. If you do not understand the criticism, you are doomed to repeat the same mistakes. Take notes and ask questions.

Sometimes it is easier said than done, but receiving effective criticism offers opportunities to see things differently, improve performance, and learn from mistakes.

Key Takeaways

- Peer review strengthens our final product, offers us a deeper learning experience, and boosts our confidence in our final product.

- Using a systematic method helps us to offer helpful and useful feedback.

- Using language that communicates a desire to help can have a positive influence on the peer review process.

Cho, Kwangsu, Christian D. Schunn, and Davida Charney. “Commenting on Writing: Typology and Perceived Helpfulness of Comments from Novice Peer Reviewers and Subject Matter Experts.” Written Communication 23.3 (2006): 260-294.

Eli Review. (2014, December 19). Describe-evaluate-suggest: Giving helpful feedback, with Bill Hart-Davidson [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KzdBRRQhYv4

Graff, Nelson. “Approaching Authentic Peer Review.” The English Journal 95.5 (2009): 81-89.

Nilson, Linda B. “Improving Student Peer Feedback.” College Teaching 51.1 (2003): 34-38.

“Using Peer Review to Help Students Improve Writing.” The Teaching Center . Washington University in St. Louis. n.d. Web. 1 June 2014.

Public Speaking Copyright © by Dr. Layne Goodman; Amber Green, M.A.; and Various is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How to Give Effective Presentation Feedback

A conversation with sam j. lubner, md, facp.

Giving an effective scientific presentation, like all public speaking, is an acquired skill that takes practice to perfect. When delivered successfully, an oral presentation can be an invaluable opportunity to showcase your latest research results among your colleagues and peers. It can also promote attendee engagement and help audience members retain the information being presented, enhancing the educational benefit of your talk, according to Sam J. Lubner, MD, FACP , Associate Professor of Medicine and Program Director, Hematology-Oncology Fellowship, at the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, and a member of ASCO’s Education Council.

Sam J. Lubner, MD, FACP

In 2019, the Education Council launched a pilot program to provide a group of selected speakers at the ASCO Annual Meeting with feedback on their presentations. Although some of the reviewers, which included members of the Education Council and Education Scholars Program, as well as ASCO’s program directors, conveyed information to the presenters that was goal-referenced, tangible, transparent, actionable, specific, and personalized—the hallmarks of effective feedback—others provided comments that were too vague to improve the speaker’s performance, said Dr. Lubner. For example, they offered comments such as “Great session” or “Your slides were too complicated,” without being specific about what made the session “great” or the slides “too complicated.”

“Giving a presentation at a scientific meeting is different from what we were trained to do. We’re trained to take care of patients, and while we do have some training in presentation, it usually centers around how to deliver clinical information,” said Dr. Lubner. “What we are trying to do with the Education Council’s presentation feedback project is to apply evidence-based methods for giving effective feedback to make presentations at ASCO’s Annual Meeting, international meetings, symposia, and conferences more clinically relevant and educationally beneficial.”

GUEST EDITOR

The ASCO Post talked with Dr. Lubner about how to give effective feedback and how to become a more effective presenter.

Defining Effective Feedback

Feedback is often confused with giving advice, praise, and evaluation, but none of these descriptions are exactly accurate. What constitutes effective feedback?

When I was looking over the literature on feedback to prepare myself on how to give effective feedback to the medical students and residents I oversee, I was amazed to find the information is largely outdated. For example, recommendations in the 1980s and 1990s called for employing the “sandwich” feedback method, which involves saying something positive, then saying what needs to be improved, and then making another positive remark. But that method is time-intensive, and it feels disingenuous to me.

What constitutes helpful feedback to me is information that is goal-referenced, actionable, specific, and has immediate impact. It should be constructive, descriptive, and nonjudgmental. After I give feedback to a student or resident, my next comments often start with a self-reflective question, “How did that go?” and that opens the door to further discussion. The mnemonic I use to provide better feedback and achieve learning goals is SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and timely, as described here:

- Specific: Avoid using ambiguous language, for example, “Your presentation was great.” Be specific about what made the presentation “great,” such as, “Starting your presentation off with a provocative question grabbed my attention.”

- Measurable: Suggest quantifiable objectives to meet so there is no uncertainty about what the goals are. For example, “Next time, try a summary slide with one or two take-home points for the audience.”

- Achievable: The goal of the presentation should be attainable. For example, “Trim your slides to no more than six lines per slide and no more than six words per line; otherwise, you are just reading your slides.”

- Realistic: The feedback you give should relate to the goal the presenter is trying to achieve. For example, “Relating the research results back to an initial case presentation will solidify the take-home point that for cancer x, treatment y is the best choice.”

- Timely: Feedback given directly after completion of the presentation is more effective than feedback provided at a later date.

The ultimate goal of effective feedback is to help the presenter become more adept at relaying his or her research in an engaging and concise way, to maintain the audience’s attention and ensure that they retain the information presented.

“Giving a presentation at a scientific meeting is different from what we were trained to do.” — Sam J. Lubner, MD, FACP Tweet this quote

Honing Your Communication Skills

What are some specific tips on how to give effective feedback?

There are five tips that immediately come to mind: (1) focus on description rather than judgment; (2) focus on observation rather than inference; (3) focus on observable behaviors; (4) share both positive and constructive specific points of feedback with the presenter; and (5) focus on the most important points to improve future presentations.

Becoming a Proficient Presenter

How can ASCO faculty become more proficient at delivering their research at the Annual Meeting and at ASCO’s thematic meetings?

ASCO has published faculty guidelines and best practices to help speakers immediately involve an audience in their presentation and hold their attention throughout the talk. They include the following recommendations:

- Be engaging. Include content that will grab the audience’s attention early. For example, interesting facts, images, or a short video to hold the audience’s focus.

- Be cohesive and concise. When preparing slides, make sure the presentation has a clear and logical flow to it, from the introduction to its conclusion. Establish key points and clearly define their importance and impact in a concise, digestible manner.

- Include take-home points. Speakers should briefly summarize key findings from their research and ensure that their conclusion is fully supported by the data in their presentation. If possible, they should provide recommendations or actions to help solidify their message. Thinking about and answering this question—if the audience remembers one thing from my presentation, what do I want it to be?—will help speakers focus their presentation.

- When it comes to slide design, remember, less is more. It’s imperative to keep slides simple to make an impact on the audience.

Another method to keep the audience engaged and enhance the educational benefit of the talk is to use the Think-Pair ( ± Share) strategy, by which the speaker asks attendees to think through questions using two to three steps. They include:

- Think independently about the question that has been posed, forming ideas.

- Pair to discuss thoughts, allowing learners to articulate their ideas and to consider those of others.

- Share (as a pair) the ideas with the larger group.

The value of this exercise is that it helps participants retain the information presented, encourages individual participation, and refines ideas and knowledge through collaboration.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SLIDE DESIGN

- Have a single point per line.

- Use < 6 words per line.

- Use < 6 lines per slide.

- Use < 30 characters per slide.

- Use simple words.

- When using tables, maintain a maximum of 6 rows and 6 columns.

- Avoid busy graphics or tables. If you find yourself apologizing to the audience because your slide is too busy, it’s a bad slide and should not be included in the presentation.

- Use cues, not full thoughts, to make your point.

- Keep to one slide per minute as a guide to the length of the presentation.

- Include summary/take-home points per concept. We are all physicians who care about our patients and believe in adhering to good science. Highlight the information you want the audience to take away from your presentation and how that information applies to excellent patient care.

Speakers should also avoid using shorthand communication or dehumanizing language when describing research results. For example, do not refer to patients as a disease: “The study included 250 EGFR mutants.” Say instead, “The study included 250 patients with EGFR -mutant tumors.” And do not use language that appears to blame patients when their cancer progresses after treatment, such as, “Six patients failed to respond to [study drug].” Instead say, “Six patients had tumors that did not respond to [study drug].”

We all have respect for our patients, families, and colleagues, but sometimes our language doesn’t reflect that level of respect, and we need to be more careful and precise in the language we use when talking with our patients and our colleagues.

ASCO has developed a document titled “The Language of Respect” to provide guidance on appropriate respectful language to use when talking with patients, family members, or other health-care providers and when giving presentations at the Annual Meeting and other ASCO symposia. Presenters should keep these critical points in mind and put them into practice when delivering research data at these meetings. ■

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Lubner has been employed by Farcast Biosciences and has held a leadership role at Farcast Biosciences.

What Is the Impact of a Colon or Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis on Younger Adults?

International cancer organizations present collaborative work during oncology event in china, is there a role for neoadjuvant chemotherapy in hr-positive, her2-negative early breast cancer, suicide-related mortality in male aya cancer survivors, four-year asian subpopulation data from the checkmate 816 trial of neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable nsclc.

- Editorial Board

- Advertising

- Disclosures

- Privacy Policy

- LibGuides Home (current)

- Collections & Services

- General Research

- Resource Specific

- Scholarly & Research

- Subject & Topic

- Course & Assignment

Peer Review and Research

- Annual Library Symposium This link opens in a new window

- Committee Info This link opens in a new window

- Clear Goals

- Adequate Preparation

- Appropriate Methods

- Significant Results

Effective Presentation

Recommended reading.

- Reflective Critique

- Submitting Papers to Peer Reviewed Publications

- Toolbox for Library Researchers

Schedule a Pre or Post Conference Presentation

- Lunchtime brown bag: Noon - 1:00 p.m.

- Late afternoon coffee/tea brown bag: after 3:00 p.m.

- Types of Presentation

- Additional Suggestions for Success

Communication

- The work should clearly communicate the content without calls for clarification.

- If written for the general public, simplification of terms and provision of background information would allow attendees to easily grasp the concepts and research results being reported.

- If written for fellow scholars and researchers, the content would presume no need for topic education is necessary, that terminology is consistent with the subject area, and research reporting would be at the level of scholarly writing.

- The work should be free of grammatical and punctuation errors.

- Numbers and data, if used, should be presented in a manner which makes understanding easy to achieve.

Ask yourself:

- Does the content wording and use of terms match the intended audience?

- Is evidence presented logically and use appropriately?

- Is the work clearly and succinctly organized?

- Are discussions and research results of subjects, either individual or groups, presented in an objective and respectful manner?

- Are sensitive topics and issues presented with thoughtfulness and courtesy?

- Works submitted for publication in traditional print resources should follow the publisher’s guide to submissions, especially criteria involving relevant value to the readers.

- Works submitted for publication in an electronic format – web site, digital, PDF, etc. – should be cognizant of the type of format and the format’s strengths in appealing to the reader by use of technology, programming, and audio or video motion.

- Is the work suitable to the audience targeted?

- Does the work present an appropriate and suitable style?

- The work should clearly state the purpose of the work, the goals that were designed, the results that occurred, any differences between the goals and the results, and the importance of the research results to the audience or area of interest.

- The author should demonstrate scholarship in the field by the quality of supporting evidence, research method, research results, and interpretation of those results.

- Is the work objective in its content and presentation?

- Are conclusions reached without predeterminations and outside influence?

- Is there sufficient evidence, both in terms of amount and substance, to effectively support the outcome?

- Does the work provide new evidence or research results that would be of interest to the field, practitioners, and scholars?

Blogs, Listservs, and Social Media

Electronic presentations are a great way to gage collegial ideas and opinions about the topic you have selected to pursue. These formats can be done at varying and convenient times.

- Online brevity is the best – adopt Twitter’s 140 character limit, and select words carefully.

- Use simple statements.

- DON’T SHOUT.

- Seek feedback and comments.

Exhibits consist of a visual display of a collection, program, initiative, or body of work (i.e. paintings, drawings, prints, posters, photography, sculpture, ceramics, video, installation, multi-media).

- Include a general statement of purpose and statements to provide an intellectual context both for the collection as a whole and for its individual pieces.

- Be prepared to respond to comments and questions.

Facilitated Discussions

Facilitated discussions involve the arranging of attendees into groups, such as tables or round chair setup, and provide topics for discussion. Topics can be the same for all attendees and groups, or vary by group.

- Provide a brief introduction – remember that you are not the presenter, and the discussions are the purpose of this event.

- Develop discussion points, topics, and questions well in advance by polling registered attendees.

- Be willing to accept ad-hoc discussion topics relevant to the content.

- Provide for adequate Q&A and open comment time at the end.

- Ensure that the majority of time allotted for the event is reserved for discussion and report-back.

- Record group report-back’s on flip charts or other method, so that attendees may view the report-back comments as they are read out, and receive a written copy after the event.

- Foster collegial conversational exchange.

- Mingle among the groups or tables to see if attendees are participating, but avoid becoming involved in their discussions.

Keynote Address

The keynote address is perhaps the most challenging presentation. What you say and how well you communicate your ideas, research, findings, and experience sets the tone for the event. High level competency and established experience are the minimum content goals. See Oral Presentations for additional guidance.

- Presentation much be absolutely relevant to the event.

- This is a stand-alone presentation.

- Be prepared to “wow” the audience with a dynamic content, excellent slides, well developed public speaking skills, and inspiration.

- Professional credibility is presumed.

Oral Presentations

Oral presentations involve the presentation of a paper or research project with or without visual aids. This is an excellent opportunity to share research findings with colleagues, seek comments, listen to advice, and facilitate discussion and comment.

- Focus on the purpose, methodology, challenges, and findings of the research.

- Report laboratory and data results, if applicable.

- Clearly provide the reason that motivated research interest and commencement.

- Disclose the strengths and weakness of the research process, and what was learned from failures.

- PowerPoint presentations should be well done. See PowerPoint Use in Presentation for more details.

- Subject mastery is presumed.

- Expect questions and comments that indicate doubt or disagreement, and respond collegially.

- Include a Q&A section at the end of the presentation.

- Provide contact information.

Panel Discussions

Panel discussions involve a limited number of panelists, usually 3-5, presenting and discussing their views on a scholarly topic and responding to audience questions.

- Select speakers from different perspectives to give balanced presentations.

- Before finalizing speaker selection, discuss panel content and purpose to ensure that potential speakers understand the purpose of the panel discussion.

- Ask panelists to state their points concisely and clearly, mindful of the limited time for each panelist.

- Anticipate questions from both the audience and panelists.

- Defer comment and questions from the audience to panelists.

- Provide ample time for individual presentations, statements, general discussion, and Q&A.

Peer Review Publications

Poster sessions.

Posters present a visual display of work on poster boards. Presenters should be able to provide a scholarly introduction to their work and be prepared to entertain the viewers’ questions.

- Include both charts and pictures.

- Develop an eye catching format and design.

- Brevity works best, both for what is on the poster and for answering visitors.

- Have a one-sheet handout for the main take-away points, including your contact information.

- Have business cards available.

- Be prepared for many repeats of your 60-second verbal summary.

- Expect fast and furious turnovers.

- Balance the content – not too sparse but not too detailed and complex.

PowerPoint Use in Presentations

Using PowerPoint or any slide programmed should be viewed as a supplemental visual tool for many types of presentations. They should not be treated as “the” presentation.

- Don’t read from the slides.

- Look at the screen as little as possible.

- Present from knowledge and experience, not from the slides.

- Slides should be limited in numbers and complexity.

- Charts, graphics, pictures, and other inserts should be simple and visually clear.

- Sound, video, and images add value, if content relevant.

- Use bullet points. PowerPoint slides do not need full sentences, and should never have a paragraph full of information.

- Use images effectively. You should have as little text as possible on the slide. One way to accomplish this is to have images on each slide, accompanied by a small amount of text.

- Slides provide focus and guidance, not full details.

- Never put your presentation on the slides and read from the slides.

Workshops consist of a brief presentation followed by interaction with the audience. The purpose of a workshop is to introduce the audience to your subject and involve them in using a skill or technique. Learning objectives and anticipated outcomes should be clearly stated.

- Content should be timely and relevant.

- Content should be take-away – attendees should be able to leave the workshop, go back to their jobs, and begin brainstorming ideas, developing strategies, and implementing projects soon.

- Go short on theories and long on how-to methods.

- Develop learning objectives and anticipated outcomes, and build content around these goals.

- Develop an agenda that more resembles a syllabus.

- Select preparation materials, such as articles and documents to read before the workshop.

- Include data but do not overwhelm attendees with too much or complex data.

- Provide a bibliography or list of suggested readings.

Academic Presentation Formula

Newbies are strongly encouraged to follow this formula. Later and with experience, deviation from the formula is more feasible.

- Introduction/Overview/Hook

- Theoretical Framework/Research Question

- Methodology/Case Selection

- Background/Literature Review

- Discussion of Data/Results

- Q&A, if permitted

The Audience Is Ready to Listen

Avoid presenting too much information about what is already known, and provide this information, if needed, in the introduction. Only discuss literature and background information that relates directly to the topic and research results being presented. Keep this portion of the presentation to five minutes or less. More time will be needed for the presentation of the research results and audience questions and comments.

Practice Practice Practice

Practice the presentation from start to finish before delivering the presentation – several times. Repeated practicing provides delivery confidence, efficient time management, and better speaking skills. Make sure the presentation fits within the time parameters. Practicing also makes it flow better.

Keep To the Time Limit

If the time allotted for the presentation is ten minutes, prepare ten minutes of material. Regardless of the amount of time provided, a little or a lot, finish within or at the end of the allotted time. Practice the presentation with a stopwatch to ensure complicity.

- << Previous: Significant Results

- Next: Reflective Critique >>

- Last Updated: Sep 6, 2024 1:59 PM

- URL: https://library.fiu.edu/PeerReview

Information

Fiu libraries floorplans, green library, modesto a. maidique campus, hubert library, biscayne bay campus.

Directions: Green Library, MMC

Directions: Hubert Library, BBC

COMMENTS

This presentation will include the who, what, where, when, and why of peer review. The slides presented here are designed to aid the facilitator in an interactive presentation of the elements of peer review. This presentation is ideal for any level of writing, including freshman composition. This resource is enhanced by a PowerPoint file.

Learn how to make peer review meaningful and effective for students who give speeches, presentations, and paper drafts. Find 10 prompts for content, presentation, and technology skills, and see examples and resources from MIT and other instructors.

Be actionable. Giving students your opinions on their presentation is important, but make sure that you give them a specific action they can do to implement your feedback. Examples of how feedback can be improved with actions is below: Weak pieces of feedback. Stronger pieces of feedback.

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom. Here’s how your outline might look: 1. Summary of the research and your overall impression. In your own words, summarize what the manuscript ...

Learn how to introduce and teach peer feedback with presentations in English language teaching. Find out the benefits, criteria, strategies and tips for students and teachers.

Find criteria and feedback examples for peer review of writing-intensive assignments and class presentations. Learn how to provide constructive and actionable comments to your peers.

Providing students frameworks that define the peer review task (like this one) can help guide them away from shallow, negative commentary and toward the sort of deep, constructive insights that make peer review more useful. You may also consider making use of the OWL's own peer review presentation, which was created with a student audience in mind.

Minimizes Procrastination: Often students will wait until the last minute to prepare their speech outline. The peer review process forces students to prepare in enough time to work through edits and revisions which are necessary for effective speech development. Builds Confidence: Public speaking is a nerve-wracking event for many of us. Having ...

Achievable: The goal of the presentation should be attainable. For example, “Trim your slides to no more than six lines per slide and no more than six words per line; otherwise, you are just reading your slides.”. Realistic: The feedback you give should relate to the goal the presenter is trying to achieve. For example, “Relating the ...

Schedule a Pre or Post Conference Presentation Do a first run to receive feedback, or share a recent presentation with us. The Peer Review and Research Committee can schedule a session for you to speak with small or large groups. Lunchtime brown bag: Noon - 1:00 p.m. Late afternoon coffee/tea brown bag: after 3:00 p.m.