Filed under:

How to fix Facebook

Can Facebook be redeemed? Twelve leading experts share bold solutions to the company’s urgent problems.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: How to fix Facebook

Facebook is broken, and after a recent deluge of damning internal company leaks to the press and Congress, the world has unassailable proof of how troubled it really is.

Almost 2 billion people around the world use a product owned by Meta ( formerly called Facebook ), including WhatsApp and Instagram, every day. For many of its users, the nearly $1 trillion valuation company is the internet and their primary platform for communication and information. Millions of us are dependent on its products in one way or another.

So what can be done to fix Facebook? Or is it past the point of fixing?

The documents leaked by employee whistleblower Frances Haugen, which were first reported by the Wall Street Journal in late September, revealed a host of problems: how Facebook-owned Instagram can be detrimental to teenagers’ mental health , how the company struggled to contain erroneous anti-vaccine Covid-19 content posted by its users, and how political extremism spread on the platform leading up to the January 6 Capitol riot. The documents Haugen leaked also showed that Facebook was seemingly aware of serious harms caused by its products, but in many cases failed to sufficiently address them.

In a statement, Facebook spokesperson Drew Pusateri responded in part: “We take steps to keep people safe even if it impacts our bottom line. To say we turn a blind eye to feedback ignores these investments, which includes the over $5 billion we’re on track to spend this year alone on safety and security, as well as the 40,000 people working on these issues at Facebook.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987116/GettyImages_1235714353.jpg)

For years, Congress has debated how and if it should regulate Facebook and other major social media products like Twitter, TikTok, Snapchat, and Google-owned YouTube. Outside researchers have been raising concerns about how the potentially grave long-term consequences of these platforms may be harming society at large . American users across the political spectrum have become increasingly suspicious of Big Tech . And even Facebook itself has said it welcomes regulation (while at the same time saying it’s against some regulation efforts, like strengthening antitrust laws ). But so far, federal bills to regulate privacy, competition, or other aspects of social media businesses have gone nowhere.

Now, the gravity of the new reporting about Facebook — particularly the research about Instagram’s harm to teenagers — is leading many Republicans and Democrats to agree that even if their political motivations are different, something must be done to rein in Facebook.

And it’s not just Congress that’s thinking about Facebook’s problems and how to deal with them, it’s also social scientists, the company’s former and current employees, policy experts, and the many people who use its services.

Even Facebook says it is seeking guidance on how to address some of its problems. The company says that, for two and a half years, it has been calling for updated regulations on its business.

“Every day, we make difficult decisions on where to draw lines between free expression and harmful speech, privacy, security, and other issues, and we use both our own research and research from outside experts to improve our products and policies,” wrote Pusateri. “But we should not be making these decisions on our own which is why for years we’ve been advocating for updated regulations where democratic governments set industry standards to which we can all adhere.”

So now is an urgent time to explore ideas old and new — inside and outside the realm of political reality — about how to confront a seemingly intractable problem: Can Facebook be fixed?

To try to answer that question, Recode interviewed 12 of the leading thinkers and leaders on Facebook today: from Sen. Amy Klobuchar , who is leading new Senate legislation to update antitrust laws for the tech sector; to Stanford Internet Observatory researcher Renee DiResta, who was one of the first researchers to study viral misinformation on the platform; to former Facebook executive Brian Boland , who was one of the few high-ranking employees at the company to speak out publicly against Facebook’s business practices.

First, most believe that Facebook can be fixed, or at least that some of its issues are possible to improve. Their ideas are wide-ranging, with some more ambitious and unexpected than others. But common themes emerge in many of their answers that reveal a growing consensus about what Facebook needs to change and a few different paths that regulators and the company itself could take to make it happen:

- Antitrust enforcement. Facebook isn’t just Facebook but, under the Meta umbrella, also Instagram, WhatsApp, Messenger, and Oculus. And several experts Recode interviewed believe that forcing Facebook to spin off these businesses would defang it of its concentrated power, allow smaller competitors to arise, and challenge the company to do better by offering customers alternatives for information and communication.

- Create a federal agency to oversee social media, like the Food and Drug Administration. The social media industry has no dedicated oversight agency in the US the way that other industries do, despite its growing power and influence in society. That’s why some people we interviewed advocated for making a new agency — or at least increasing funding for the existing FTC — so that it could regulate safety standards on the internet the same way the FDA does for food and pharmaceutical drugs.

- Change Facebook’s leadership. Facebook’s problems are almost synonymous with the leadership of Mark Zuckerberg, who has unilaterally controlled the company he started in his Harvard dorm room in 2004. Many interviewees believe that for any meaningful change to happen, Facebook needs an executive shake-up, starting from the very top.

- Section 230 reform. Section 230 is a landmark law that protects free speech as we know it online. It does that by shielding tech companies like Facebook from facing legal consequences for the real-world harm users can cause with the content they post on its platforms. But reforming 230 in a way that won’t run into First Amendment challenges, or entrench incumbents like Facebook itself, will be challenging.

- Increase transparency. You can’t fix a problem if you don’t know exactly what the problem is. Facebook, like other social media companies, is largely a black box to researchers, journalists, and analysts trying to understand how its complex and ever-changing algorithms dictate what billions of people see online. Which is why some of the experts interviewed by Recode argued that Facebook and other social media companies should be legally required to share certain internal data with vetted researchers about what information is circulating on their platforms.

- Hold Mark Zuckerberg and other Facebook executives criminally liable. This was the most extreme idea proposed, but some experts Recode interviewed suggested that Facebook executives should be criminally prosecuted for either misleading business partners or downplaying human harms their company causes.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987986/GettyImages_944440756.jpg)

Other approaches proposed by interviewed experts are more incremental, like redesigning Facebook’s Groups, a part of the app that has been a breeding ground for conspiracy movements like QAnon, anti-vaccine activism, and extremist political events.

The interviews were conducted separately. In each, Recode asked, “How would you fix Facebook?” Each expert defined on their own what they believe are Facebook’s biggest problems, as well as how they would fix them. Recode then asked follow-up questions based on the interviewees’ answers. These interviews have been combined, condensed, and edited for length and clarity.

Their answers are in no way a comprehensive list of all the possible solutions to Facebook’s problems, and many of them would be difficult to achieve anytime soon. But they offer a thoughtful start during a pivotal moment, as millions of people are reconsidering the bargain they agree to each time they use the company’s products.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) has long been a leader in Congress calling for regulation of the social media industry , on topics from political advertising to health misinformation . In October, Klobuchar introduced a Senate antitrust bill aimed at stopping major tech platforms from using their power to unfairly disadvantage competitors. Klobuchar also is the chair and top-ranking Democrat on the Senate antitrust committee.

How would you fix Facebook?

First, federal privacy law. Second, protecting kids online. Third, antitrust updates [and] law changes, to make our laws as sophisticated as the companies that are now in our economy. And then finally, doing something about the algorithms.

Can you explain what you would do in each of those areas?

People have to opt in if they want their data shared. When Apple recently gave their users a decision about whether to have their data tracked, 75 percent did not opt in. And that is what you would see across platforms, if it actually was a clear choice. Which it never is — it’s very confusing.

Secondly, protecting kids online, that would include not only expanding the protections from the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act.

You can’t doubt that Facebook developed an innovative product. Yes, they did. But they clearly haven’t been able to compete with the times in terms of what innovations could protect people from the problems they’re having now, like for parents that don’t want to get their kids hooked.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987784/AP21273554533123__1_a.jpg)

So my argument is that by allowing the antitrust laws to actually work and be updated, then you’re going to be able to look at some of these past mergers, like Instagram.

And here, we’re not talking about “destroying” Facebook or all these dramatic words, we’re talking about looking at the industry as a whole and figuring out if we need to update our competition laws, to track everything from what’s happening with the app stores to what’s happening with the platforms when it comes to selling stuff, so that they cannot be preferencing their own content and discriminating against competitors. I believe that is one, but not the only way; using the marketplace to push innovations and responsiveness to these problems.

How would you reform Section 230?

The one where we need to do the most work to figure out while still respecting free speech is [why] they’ve got total immunity when they amplify [harmful] stuff.

I already have a bill out there to get rid of the immunity for vaccine misinformation during a health crisis, as well as one that [Sen. Mark] Warner’s (D-VA) leading with Mazie Hirono (D-HI) and myself, which is about discrimination, violent conduct, and civil rights violations and the like.

Do you think Facebook can really change with Mark Zuckerberg in charge?

Have I been impressed by how he’s handled this latest crisis? No. He went sailing and issued posts from his boat. Basically he was saying, “Yeah, we’ll look at this,” but we got a whole week of no apologies. And that’s fine. He can choose not to apologize. That’s up to him. That’s a PR decision. But I think we are beyond expecting that he’s going to make the changes or whoever’s in charge of Facebook is going to make the changes. I think it’s time for us to act.

Matt Stoller, research director at the American Economic Liberties Project

Matt Stoller is a leading critic of monopoly power in the US economy , particularly in tech. He’s the author of the book Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy .

One, I would send Mark Zuckerberg to jail for securities fraud and advertising fraud. Maybe Sheryl Sandberg too, for insider trading. There, you have a cultural lawlessness, and you have to address that it’s a threat to the law. So we’ve got to start there.

They lied to advertisers around their reach. And that caused advertisers to spend more money on Facebook than they would have. And with these advertising frauds, they decided not to tell investors. [Editor’s note: Facebook has been sued by advertisers for allegedly inflating key metrics around how many of its users actually see advertisements companies pay for.]

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987008/GettyImages_1327683542.jpg)

Then, No. 2, I would break up the firm. The mergers of Instagram and WhatsApp are illegal and they should be unwound. That would create more fair competition in the social media market. And when firms compete, they usually have to compete by differentiating their product around quality. I would also break up their advertising. I would also sever Facebook’s ads subsidiary. [Editor’s note: Together with Google, Facebook’s advertising business represents a majority of all advertisements sold online in the US . Some have proposed separating these companies’ advertising business lines from their other lines of business to increase competition.]

And No. 3, set clear rules of the road for the industry around advertising. Just ban surveillance advertising. When I think about the problem, I look at it and I say, “Okay, this is a firm that has an advertising model that is based on undermining social stability.” They break the law and use legal power to fortify and protect their business model. So you have to address that. That’s the problem that I see.

Why do you think criminal liabilities for Mark Zuckerberg is a higher priority than breaking antitrust?

Antitrust or any regulatory policy is going to take several years to really go into force. And these guys just don’t care. They don’t care what the government does. They simply don’t believe that anything will affect them. And the only way to address that problem is to actually bring the problem straight to them. And that means sanctioning them personally: threatening to take away their freedom for violating the law. You have to make the stakes real.

The point here isn’t that Mark Zuckerberg is a bad guy. The point here is that you have a culture of lawlessness at the firm.

Brian Boland, former Facebook executive

Brian Boland is one of the few former Facebook executives to publicly criticize the company for its business practices, arguing that Facebook needs to be more transparent about the proliferation of viral misinformation and other harmful content on its platform. Boland was a vice president of partnerships and marketing, and worked at the company for 11 years.

We need to dramatically improve the safety and privacy of the platform. This breaks down into at least three things — the creation of a fully empowered regulatory body that has oversight over digital companies, reforms of Section 230, and meaningful transparency.

The one thing that Facebook could control right now is transparency. Helping society understand the harms on social media is an important step for fixing the problems. Twitter just shared research data on which political content gets more distribution on Twitter. That’s a great step where they are taking the lead.

Why is a regulatory body so important?

A regulatory body is in line with how we’ve generally worked in the United States when we’ve wanted to rein in industries that are out of control. The same way that we build building codes, that we regulate the chemicals industry. The food supply used to be unsafe, but then the FDA was created to make it safe. If you think about your car that you’re getting in every day, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration keeps you safe by making sure the car is safe.

So the things that we need to do for digital is just like all the other regulation that we’ve done before. That still gives people the great products, right? You still have awesome cars, you still have amazing food, and there’s chemicals you use every day in your life. And the building that you’re in right now is not going to collapse. We just need to do the same thing with digital platforms and services and have that regulatory body and oversight to understand what’s harmful and broken, and then the regulatory authority to mandate fixing those things.

How would you go about making data more transparent?

I think you start to make data feeds of public data available, in the same way that you have engagement data available in CrowdTangle . But you ensure that it spans the globe and has metrics like reach and engagement and distribution, so people can see what gets recommended [and] goes viral.

Algorithms aren’t good or bad, they just promote things based on the way they’ve been initially coded, and then what they learn along the way, so it’s not like people deeply understand what algorithms do or why they do it.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987041/GettyImages_1229328067.jpg)

What would you change in Section 230?

There are two important elements for me: including a provision for a duty of care and removing protections of what algorithms amplify. A duty-of-care provision would ensure that Section 230 doesn’t remove the responsibility of platforms to reduce harms to their customers. This wouldn’t require that every harmful act is removed, but that the platforms take meaningful steps to reduce harm.

For the second part, we can ensure that we protect people’s free speech on platforms like Facebook, but actually hold the platforms accountable for what they choose to amplify. These algorithms take actions that make some speech heard far more than other speech. Facebook has control over its algorithms and should not be protected from the harms those algorithms can create.

Do you think Facebook can be reformed with Mark Zuckerberg at the helm?

There’s a chance, with strong regulatory oversight, that they’ll be forced to change — but his nature is not to move in this direction. If we want Facebook and Instagram to be responsible and safer, then I don’t think you can have him and the current leadership team leading the company.

Roger McNamee, early Facebook investor and member of “the real Facebook oversight board”

Roger McNamee is an early Facebook investor and former adviser to Mark Zuckerberg. He famously changed his opinion of the company after he saw what he believed were serious failures in its leadership and business priorities.

In my opinion, you need to have three forms of legislative relief. You need to address safety, you need to adjust privacy, and you need to address competition. If Facebook were to disappear tomorrow, 100 companies would compete to fill the void, doing all the same horrible things Facebook is doing. So whatever solutions we craft must be broad enough that they prevent that from happening.

On safety, I recommend that the government create an agency, analogous to the Food and Drug Administration, that would set guidelines for which technologies should be allowed to come to market at all, and what rules they would have to follow to create a commercial product and then to remain in the market.

How do you address privacy issues?

My mentor and friend Shoshana Zuboff said this best, which is that surveillance capitalism is as morally flawed as child labor, and should be banned for the same reason.

The starting place would be to ban any third-party use of location, health, financial, app usage, web browsing, and whatever other categories of intimate data are out there.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987063/GettyImages_1236314651.jpg)

You used to have a relationship with Mark Zuckerberg as an early investor. Do you have any confidence that the company can be fixed under his leadership?

I think this is the wrong question, if you don’t mind my saying so. I think that the underlying issue here is, we tell CEOs that their only job is to maximize shareholder value. It used to be that you told CEOs that they had to find a balance between shareholders, employees, the communities where employees live (including the country where they live), and its customers and suppliers. They had five constituents, and now we only have one [shareholders]. And so it’s important to recognize that a big part of what’s wrong here is that we have operated in an environment where we just applied the incorrect set of incentives to managers in any field, and Mark has just been more successful than other people in creating a product that took advantage of the complete absence of rules.

Benedict Evans, technology analyst

Benedict Evans is one of the tech industry’s leading analysts and thinkers on the business of social media. He is an independent analyst, and used to work for the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, an early investor in Facebook.

Do you think anything else needs to be done to fix many of the problems Facebook is criticized for? And if so, what do you think should be done?

We are clearly on a path toward regulatory requirements around content moderation both in the EU and the UK. I don’t know how you could do that in a way that could be reconciled with the American Constitution — it sounds like a legal requirement to remove speech.

You can believe that there’s a lot of nonsense talked about Facebook and also believe that it has huge problems, isn’t on top of them, and doesn’t have the incentive structures right. But it’s amazing to me how much of the press and how many politicians completely ignore YouTube, which has almost exactly the same problems.

Why do you think breaking up Facebook is not the right response?

What is the theory for why changing who owns Instagram would stop teenage girls from looking at self-harm content, and for that content being shared and suggested? Why would the dynamics change? Such a move certainly would not make it any easier to compete with Instagram, just as making YouTube a separate company would not make it any easier to make a new video-sharing site. The network effects are internal to the product, not the ownership. It also wouldn’t change the business model.

To take an analogy from another generation, there are all sorts of problems with cars, and they kill people, but that doesn’t make it sensible to compare them with tobacco. And we can punish GM for shipping a car it knows will blow up in a low-speed rear collision, but we can’t make it stop teenage boys getting drunk and driving too fast. Not everything is an antitrust problem, and most policy problems are complicated and full of trade-offs. Tech policy isn’t any simpler than education policy or health care policy.

I often think the sloganeering around “break them up!” and indeed, the new comparison of tech to tobacco, is displacement: People are hunting for simple slogans and easy answers that let you avoid having to grapple with the complexity of the issues.

In the US, the cult of the First Amendment makes this even harder. The US cannot pass laws requiring social media companies to remove X or Y, whereas the UK and EU are already well on the way to passing such laws, which makes “break them up” an even stronger form of displacement — it’s what you can do as a US politician, rather than what can work.

Rep. Ken Buck

Rep. Ken Buck (R-CO) is a leading Republican in Congress on regulating tech. He co-led the historic congressional investigation into Big Tech and antitrust which finished last year, and has been one of the most senior members of his party to join with Democrats in bipartisan legislation to strengthen antitrust laws.

The obvious dangers of the platform are that bad people can use it for evil purposes. And then there are other unintended consequences where good people use it and are harmed through no fault of their own, but just because of the psychological impact.

When there’s a study that shows that something was dangerous with a car or with a food product, there’s a recall.

Facebook should be able to recall its product and to ameliorate the damages that are done before it goes too far. And they didn’t do that. Part of it has to be a personnel issue with leadership and the failure of leadership.

What’s the personnel issue? What changes would you make there?

I think that people who were in the know and realized that there was an increase in teen suicide rates, and that there was a relationship between their product and that increase — and they continued doing what they did — should be held criminally liable.

And as a member of Congress, what can you do? What are you doing to try to hold those people responsible?

I think that the role of Congress is to examine the situation — which we did with a 16-month investigation on the antitrust subcommittee — [and] expose the problems. And obviously, we saw things from the outside that now the whistleblower has confirmed from the inside with very damaging documents.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987080/GettyImages_1222589912.jpg)

Two, trying to fix the situation which we are in with antitrust laws, and perhaps with reforms to Section 230 . [Editor’s note: Section 230 is a landmark internet law that shields social media companies from being sued for most kinds of illegal activity committed by their users]. And then No. 3, it’s really up to the executive branch to make a decision on whether there is criminal liability, civil liability, and how to proceed.

Do you think Facebook should be broken up into separate companies?

I’m not sure that breaking up Facebook from Instagram makes as much sense as having other companies that are competing with Facebook and Instagram, in trying to innovate better and, frankly, offer parents an alternative.

I’m absolutely opposed to regulation. I don’t think the government should say, “This is appropriate speech in the newspaper or on Facebook or on Twitter.” I don’t think the government should say, “This is a feature that is positive or negative.” I think we’ve got to give consumers a choice. I think we make much more rational decisions when consumers make that choice.

When someone associates the word regulation with me, they think I’m going crazy. When they associate the words “competition in the marketplace” with me, they’re thinking, “Oh, okay, now I understand.”

Do you think that Facebook can be fixed with Mark Zuckerberg at the helm?

I think he has to take full responsibility and either take himself out of the picture, and others out of the picture, or make sure that changes are made so that he’s getting better information to make better decisions. But Facebook cannot continue to exist, should not continue to exist, the way they have.

Rashad Robinson, president, Color of Change

Rashad Robinson is the president of Color of Change, a civil rights advocacy group that co-led a historic advertiser boycott against Facebook last June in protest of the proliferation of hate speech on the platform.

I would have Instagram and WhatsApp owned by other people. And so I would shrink it.

And I would create real consequences and liability to its business model for the harm that it causes. And I would force Facebook to actually have to pay reparations for the harm they have done to local independent media , and to all the sorts of institutions that their sort of platform has destroyed.

Do you think you’ve seen progress since you helped lead the boycott against Facebook?

At that time [of the boycott], we didn’t have any levers within the government. There was no one to ask at the White House to get involved in this. Now a year has happened and we have a Biden administration. And so my demands are not to Facebook anymore, my demands are to the Biden administration and to Congress, and to tell them that they actually have to do their jobs, that we have outsized harm being done by this platform, and they actually have to do something about it.

What would real consequences look like for Facebook?

I’m not the numbers guy, but I do think [the consequences that] we’ve seen in the past from the FTC and other places have been the equivalent of a maybe expensive night out for [Facebook]. [Editor’s note: In 2019, the FTC fined Facebook $5 billion for its privacy failures in the Cambridge Analytica scandal. While it was a record-breaking fine imposed by the FTC, it failed to hinder Facebook’s financial performance and growth.]

I think that surveillance marketing on these platforms, combined with these platforms being able to have Section 230, that has to end — you can’t have it both ways. [Editor’s note: Surveillance marketing , or surveillance capitalism , is a pejorative name for business models — such as those that underpin Facebook and Google — that track people’s online behavior to target specific advertisements to them.]

Do you think Facebook can be fixed with Mark Zuckerberg in charge?

The current leadership lacks the sort of moral integrity to be the type of problem solvers our society needs. And the sooner they deal with the structures that have allowed them to be in charge, the better for all of us. But to be clear, this moment we are in — the story will be told in generations about who Mark Zuckerberg is and what he has done. And Mark Zuckerberg will always want to play by a different set of rules. He believes he can. He’s built a system for that.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987833/GettyImages_1091925298.jpg)

Nate Persily, professor at Stanford Law School and director of the Stanford Cyber Policy Center

Nate Persily co-founded an academic partnership program with Facebook in 2018, called Social Science One , which aimed to give researchers studying the real-world effects of social media unprecedented access to otherwise private Facebook data.

In 2020, Persily resigned from the program. He has since discussed the limitations of voluntary programs like Social Science One and is calling for legislation to mandate companies like Facebook to share more information with outside researchers.

The internet platforms have lost their right to secrecy. They simply are too big and too powerful. They cannot operate in secret like a lot of other corporations. And so they have an obligation to give access to their data to outsiders.

I have been working on this for five years. I’ve tried to do it with Facebook, and I’ve become convinced that legislation is the only answer.

And why do you think this is the first of Facebook’s problems to fix?

There is a fundamental disagreement between conventional wisdom and what the platforms are saying on any number of these issues.

That’s where the Haugen revelations are so momentous. It’s not just that you see quasi-salacious stuff about what’s happening on the platforms — it’s that you actually get a window into what they have access to and the kind of studies that they can perform. And then you start saying, “Well, look, if outsiders with public spirit had access to the data, think about what we could learn right now.”

Of course, all of this has to be done in a privacy-protected way to make sure that there’s no repeat of another Cambridge Analytica — and that’s where the devil is in the details.

Why should the average person care about Facebook being transparent with its data with researchers?

If you think that these platforms are the cause of any number of social problems stretching from anorexia to genocide, then we cannot trust their representations as to whether social media is innocent or guilty of committing these problems or contributing to these problems. And so [transparency] is a prerequisite to any kind of policy intervention in any of these areas, as well as actions by civil society. So part of it is informing governments and policymakers, but some of it is also informing us about what the dangers are on the platforms and how we can act to prevent them.

Transparency is a meta problem, if you will. It is the linchpin to studying every other problem as to the harms that social media is wreaking on society. And let me also say, we should be prepared for the possibility that when we do have access to the data, the truth is going to be not as bad as people think.

The story could be a much more complicated one than that algorithms are manipulating people into doing things that they otherwise wouldn’t do.

How do you make sure that Facebook is transparent with the data?

It’s quite simple. The FTC, working with the National Science Foundation, shall develop a program for vetted researchers and research projects, and shall compel the platforms to share the data with those researchers in a privacy-protected format. The data will reside at the firms [and will] not be given over to the federal government, so that we prevent another Cambridge Analytica.

It’s also not just about requiring data transparency [with researchers]. We should require [social media platforms] to disclose certain things to the public that are not privacy-dangerous. Basically, something like, “What are the most popular stories and popular links on Facebook each day?” That is not privacy-endangering.

Sen. Ed Markey

Massachusetts Sen. Ed Markey, a Democrat, has been a key congressional voice on online privacy for children for over two decades. He co-introduced the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 (COPPA) , a law requiring tech companies to obtain parental consent “before collecting, using, or disclosing personal information from children” under 13. Today, he’s focused on updating COPPA and making broader reforms to the tech industry.

No. 1, I will pass the Child Online Privacy Protection Act 2.0. I was the author of that law in 1998 that’s been used to protect children in company after company. We have to upgrade that law in order to pass a long-overdue bill of rights for kids and for teens, so that kids under 16 get the same protection as kids under 13.

I would say [we should also] ban targeted ads to children and create an online eraser button, so parents and children can tell companies to delete the troves of data that they have collected about young people. And to have a cybersecurity protection requirement for kids and teens.

Because it’s obvious that Facebook only cares about children to the extent to which they are of monetary value.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987103/GettyImages_1235714342.jpg)

Why children’s privacy first over many issues that Facebook has, like misinformation?

Kids are uniquely vulnerable. And we adults need to make sure that their data is not being used in ways that are harmful to them.

Facebook won’t protect young people. It can’t be voluntary any longer; it does not work.

Do you think Facebook can be fixed with Mark Zuckerberg at the helm?

I think regardless of who is running Facebook, we have to put a new, tough regulatory scheme in place in the event that Mark Zuckerberg leaves and his successor has the exact same philosophy. So we can’t trust the institution. We have to trust our laws.

Do you think Facebook should be broken up?

I think that the antitrust process is something that should begin. But just breaking up Facebook won’t solve the problems that we’re discussing today. We need to pass an impressive set of laws that stop social media giants from invading our privacy.

Renée DiResta, disinformation researcher at Stanford Internet Observatory

Renée DiResta is a longtime researcher of disinformation on social networks . She advised Congress on the role of foreign influence misinformation networks in the 2016 US elections. DiResta has also been one of the first social media researchers to track how anti-vaccine content and other kinds of false or extremist content spreads through Facebook Groups.

Groups are probably the most broken things on the platform today.

If I could pick one thing to really focus on in the short term, it would be more sophisticated rethinking of groups and how people are recommended groups, and how groups are evaluated for inclusion and being promoted to other people.

Why do you think fixing Groups is more important than, say, what people see in their news feed?

Because [groups] are a very, very significant part of what you see in your feed.

QAnon came out of these groups that were recommended to people, and then they came to be places where people really felt that they had found new friends and, in a sense, that kind of insularity. They evolved into echo chambers, and the groups became deeply disruptive.

But Facebook did not appear to have sophisticated metrics for evaluating [if] what was happening within groups was healthy or not healthy. The challenge became: Once groups are formed, disbanding them is a pretty major step. Perhaps one example of this is the Stop the Steal group, which grew to several [hundreds of thousands of] people or more. [Editor’s note: The Stop the Steal Facebook group was one of the key platforms where organizers of the January 6 Capitol riot prepared to march on Washington, DC.]

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987969/GettyImages_1284096852.jpg)

How could Facebook better curate content?

I think there are certain areas where [Groups] should largely be kept out of the recommendation engine entirely. I believe there are plenty of researchers who disagree with me, but I do believe that there are many areas where it’s not a problem to allow the content to be on site — it’s more a matter of it being amplified and pushed to new people.

[But] health misinformation actually kills people. Like, there is a non-theoretical harm that is very, very real. And that’s where I argue for certain cases being treated distinctly differently. You’re not going for six people being wrong on the internet, or at the local pub, or standing at the local corner with a bullhorn. That’s not what we’re going for. When we give people amplification, when we enable them to grow massive communities that trust in them [rather than] in authorities — which are institutions that actually have more accurate information — then we find ourselves in a situation where there are real negative impacts on real people in the real world. And so that question of, “How do we understand harms?” is actually the guiding principle that we should be using to understand, “How do we rethink curation?”

Katie Harbath, former director of public policy at Facebook

Katie Harbath spent 10 years working at Facebook, including as a public policy director on issues like election security. She left the company this March and is now the founder and CEO of tech policy consultancy Anchor Change.

I think one of the struggles with Facebook right now is just people see Mark, hear Mark, or see the name Facebook, and they just don’t trust anything that comes out of their mouths.

Are there changes in leadership at the top and fresh blood that are needed to help really give a new perspective, and really be somebody that people would listen to?

Can you talk a little bit about organizational and structural problems at Facebook?

Facebook’s such a flat company, and they want to move fast. They’re giving People [HR] employees different metrics because most of those are usually centered around growth. Then, when the Integrity team comes in and wants to make changes that might slow those numbers, you can get resistance. [Editor’s note: The Integrity team at Facebook is responsible for assessing the misuses and unintended consequences of the platform.] Because that’s what people’s bonuses are attached to.

The tech world loves working in ones and zeros — they’re very data-driven. Data wins arguments. But the problems that the Integrity team is working on aren’t all data-centric. There’s a lot of nuance. There’s gonna be trade-offs. So if you’ve got Integrity as a whole separate team, they’re trying to go to another team and be like, “Hey, you should do this because it’s gonna produce X, Y, and Z harms.” But they’re like, “Well, that’s gonna screw up my metric, and then I’ll get a bad performance review.” So you end up pitting teams against one another, like Integrity and Product.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22987978/Thumbs_Down_copy_2.jpg)

How would you fix that?

There’s no structural change that’s perfect.

But is it right for Integrity to be under Growth? Should it be separate? Should it be better integrated into the product lifecycle? One of the things that came out of some of these settlements around privacy is that there are particular procedures that the company had to put into place in order to make privacy considerations from the very beginning. So are there elements of that, that need to be done with the Integrity team?

Derek Thompson, staff writer, the Atlantic

Derek Thompson writes about economics, technology, and the media. He’s been writing about Facebook for several years, and his recent piece comparing Facebook to “attention alcohol” has sparked conversations about reframing how we think about social media .

One, I would treat social media the way we treat alcohol: have bans and clearer limitations on use among teenagers. And study the effects of social media on anxiety, depression, and negative social comparison. Two, I would continue to shame Facebook to edit its algorithm in a way that downshifts the emphasis on high-arousal emotions such as anger and outrage. And three, I would hire more people to focus not on misinformation in the US, but on the connection between mis- or disinformation and real-world violence in places outside the US, where real-world violence flowing from these Facebook products is a common phenomenon.

What would it mean to treat Facebook the way we treat alcohol?

The debate about Facebook is way too dichotomous. It’s between one group that says Facebook is effectively evil, and another group that says Facebook is basically no big deal. And that leaves a huge space in the middle for people to treat Facebook the same way we think about alcohol. I love alcohol. I use alcohol all the time, the same way I use social media all the time. But [with alcohol], I also understand, based on decades of research and social norms, that there are ways to overdo it.

We have a social vocabulary around [alcohol] overuse and drinking and driving. We don’t have a similar social vocabulary around social media. And social media can be very good as a social lubricant — and also dangerous as a compulsive product, as we have with alcohol. And that’s why I see them as reasonably analogous.

How would you change Facebook’s algorithm?

Facebook is both a mirror and a machine. It holds up a high-quality mirror to human behavior and shows us a reflection that includes all of human kindness, and all of human generosity, and all of human hate, and all of human conspiracy theorizing, but it is also a machine that, through the accentuation of high-arousal emotions, brings forth or elicits the most outrage and the most conspiracy theorizing and the most absurd disinformation.

We can’t fix the mirror — that would require fixing humanity. But we can fix the machine, and it’s pretty clear to me that the Facebook algorithmic machine is optimized for surfacing outrage, indignation, hate, and other high-arousal negative emotions. I would like to see more research done not only by Facebook itself but also by any government, the NIH, maybe by Stanford and Harvard, on alternative ways of organizing the world’s information [than] predominantly by the hybrid distribution of high-arousal negative emotions.

Can you explain why addressing Facebook’s issues in its operations outside the US is a priority problem that you would fix, and how you would fix that?

Most tech critics are hysterically over-devoted to the problems of technology in America, when these tech companies touch billions of people outside of America. And we should spend more time thinking about their impact outside of the country where their headquarters are based. Most of Facebook’s research into its negative effects, as I understand it, is focused on the effects of Facebook in the US. But we didn’t have WhatsApp- and Facebook-inspired genocide in the US.

Correction, November 8, 9:40 am: A previous version of this story misstated the last name of Rashad Robinson, president of Color of Change.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

The GameStop stock frenzy, explained

How tiktok shop ads turned an obscure, inaccurate book into a bestseller, social media platforms aren’t equipped to handle the negative effects of their algorithms abroad. neither is the law., sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

- Privacy Policy

- Affiliate Disclosure

The Strategy Watch

To be the Best Source of Business Strategy & Analysis

Leadership Qualities – Styles, Skills, and Traits of Mark Zuckerberg

Mark Zuckerberg, the creator of the blue and white platform called Facebook, which has given us the privilege to be with our friends and families 24/7 and share each moment with them. He was a student at Harvard but got dropped out from there. But the base of Facebook was established by him through the years on Harvard, and after getting out of there, he devoted all of himself to his dream project, and now we all know the result. Today the annual revenue of Facebook is nearly $17.9 billion, with almost 1.7 billion users worldwide. Whatever Facebook is now, Mark Zuckerberg is the one who made everything possible. And today, we’re going to know about his leadership style, qualities, and skills behind Facebook’s success.

He is one of the most influential tech entrepreneur in the recently history of the world. In this study we will look closely what we can learn from his leadership quality and style.

Leadership Qualities of Mark Zuckerberg

Seeing things differently: There’s no doubt that Mark Zuckerberg has built Facebook with his amazing programming knowledge, but many people have that knowledge, but not everyone has come up with something like Facebook. Because Mark has a visionary power in himself, he likes to see things differently. Before Facebook, there’re other platforms for communication but mostly with ordinary features. But Mark wanted to do something unique. And even now, he’s continually trying to make Facebook more unique with his numerous ideas and vision.

Developing the right company culture: Facebook isn’t like an ordinary workplace. It doesn’t maintain any strict flat hierarchy or workplace rules. Here employees with creativity, innovation, and out-of-the-box get valued and rewarded. Any employee can just relax anywhere in the office and do his work. The whole Facebook office’s design is the most unique one than any other big company in the world. And all these ideas mainly came from Zuckerberg, who wanted to build a workplace environment and culture where people won’t feel pressured and enjoy working.

He surrounds himself with the right people: The visionary power of Zuckerberg always helped him to get in touch with the right people. The idea of creating Facebook was criticized initially, but he made the team with some friends and roommate who believed in him and helped him to launch Facebook. Still now, in every situation, Mark manages to get the right people with him. Sheryl Sandberg, the COO of Facebook, who has contributed a lot to the company, didn’t get much acceptance in the beginning by others in the company. But Mark believed in him and showed others how much right he was by hiring Sheryl.

Willing to face criticism: Mark Zuckerberg has been criticized a lot for his decisions. A few years ago, when he was accused of some severe charges of privacy violation of users and had to go to court, he lots a huge amount of popularity among people. But still, he never gave up and took all the blames positively. He believes criticisms are a part of life, and it teaches some lessons as well. That’s why it’s better to face and accept those.

Leadership Style of Mark Zuckerberg: Mark Zuckerberg has never followed any structured leadership. He was both aggressive and encouraging. He did his best to provide a friendly and relaxed workplace. But his employees reported him as a bad listener. It can be said that he uses autocratic , democratic , and laissez-fair leadership styles all at once. But throughout the year’s Mark has tried to improve himself and now he has become more communicative. And that’s what makes him a Transformational Leader . He has learned from his mistake and now focused on changing his actions for the betterment of the company and the employees.

Leadership Characteristics and Traits of Mark Zuckerberg

Here’re some traits of Mark Zuckerberg that describe his personal characteristics that get reflected in his leadership style.

- Hard worker

Mark Zuckerberg knows what he wants, and when he gets engaged in something, he never loses his focus. He can continuously work for the betterment of his company or on a new idea. Surely he has some outstanding programming skills and compelling vision, but it is hard work, which made him to all these things he has done till today.

Mark Zuckerberg is ruthless whenever he needs to be. The steaming clash with the Winklevoss twins and co-founder Estavez caused much hype in the media due to Mark’s ruthlessness. He’s always determined to remove the competitive threats in the market. We all know how he became desperate to bring down the popularity of Snapchat and divert more people towards Facebook, Instagram, and Whatsapp.

Like most of the leaders, Mark doesn’t believe in taking risks without proper analysis. Yes, he has made many bold decisions, and he believes that not taking risks is the most significant risk, but only after a thorough calculation and exploration. He first measures the possibilities and only then moves forward to the next step.

Other traits and characteristics of Mark Zuckerberg are:

- Relationship-oriented

- Assertiveness

- Mindfulness

- Multi-tasking

- Accepting challenges

- Competitive

- Strong values

Leadership Skills of Mark Zuckerberg

Each leader has some skills that help him/her to perform his/her duties more perfectly. Here’re some leadership skills of Mark Zuckerberg.

Critical thinker: Mark always tends to thinks deeply. He likes to have a clear idea, no matter how small a fact is. He believes his more profound thought and understanding helps him to know what’s right or wrong. He better accepts the second or third best idea after a clear understanding instead of grabbing the best idea without any thoughts.

Problem Solving: Marks Zuckerberg is a problem-solver. He continually asks himself if he is doing right or why a specific idea isn’t working. He never leaves a problem without considering it the second time. Once he said that until he gets what’s actually wrong and how it can be fixed, he can’t just sit and relax. He feels an urge to solve the puzzle.

Equanimity: As a leader, Mark is someone who doesn’t lose his cool easily, no matter how stressful the situation becomes. He can take a lot of pressure and talks normally. There were many times when his company’s inside situation was a mess, and everyone was panicked. But he controlled everything maturely with a gentle and calm approach.

Bottom Line

Mark Zuckerberg isn’t a perfect leader. He was criticized many times for his leadership techniques and qualities. Even there were rumors that he might leave Facebook. But he never had the sense of giving up. He changed his flaws and constantly working to improve himself. And we hope there’s more to see from himself.

- Leadership Skills, and Style of Jeff Bezos

- Leadership Qualities of Larry Page

- Leadership Style of Tim Cook

- https://maisfl.com/leadership-attributes-of-mark-zuckerberg-essay/

- https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/why-mark-zuckerbergs-leadership-failure-was-a-predictable-surprise/

- https://www.businessinsider.com/this-one-trait-makes-you-a-better-boss-according-to-mark-zuckerberg-2018-1

- https://ceomarkzuckerberg.weebly.com/leadership.html

- https://www.livechat.com/success/zuckerberg-effect-qualities-of-a-good-boss/

“Fahmina has been actively contributing here with her writing skills. Fahmina has always had a way with her words, and now she is focused on channelling that knack for writing towards a more professional line of work. She is currently an undergrad, majoring in Marketing from the University of Dhaka. Her interests include writing engaging and insightful pieces related to Business Strategy Formulation, Business Analysis, Strategy Ideation, Market Analysis as well as Market Research.”

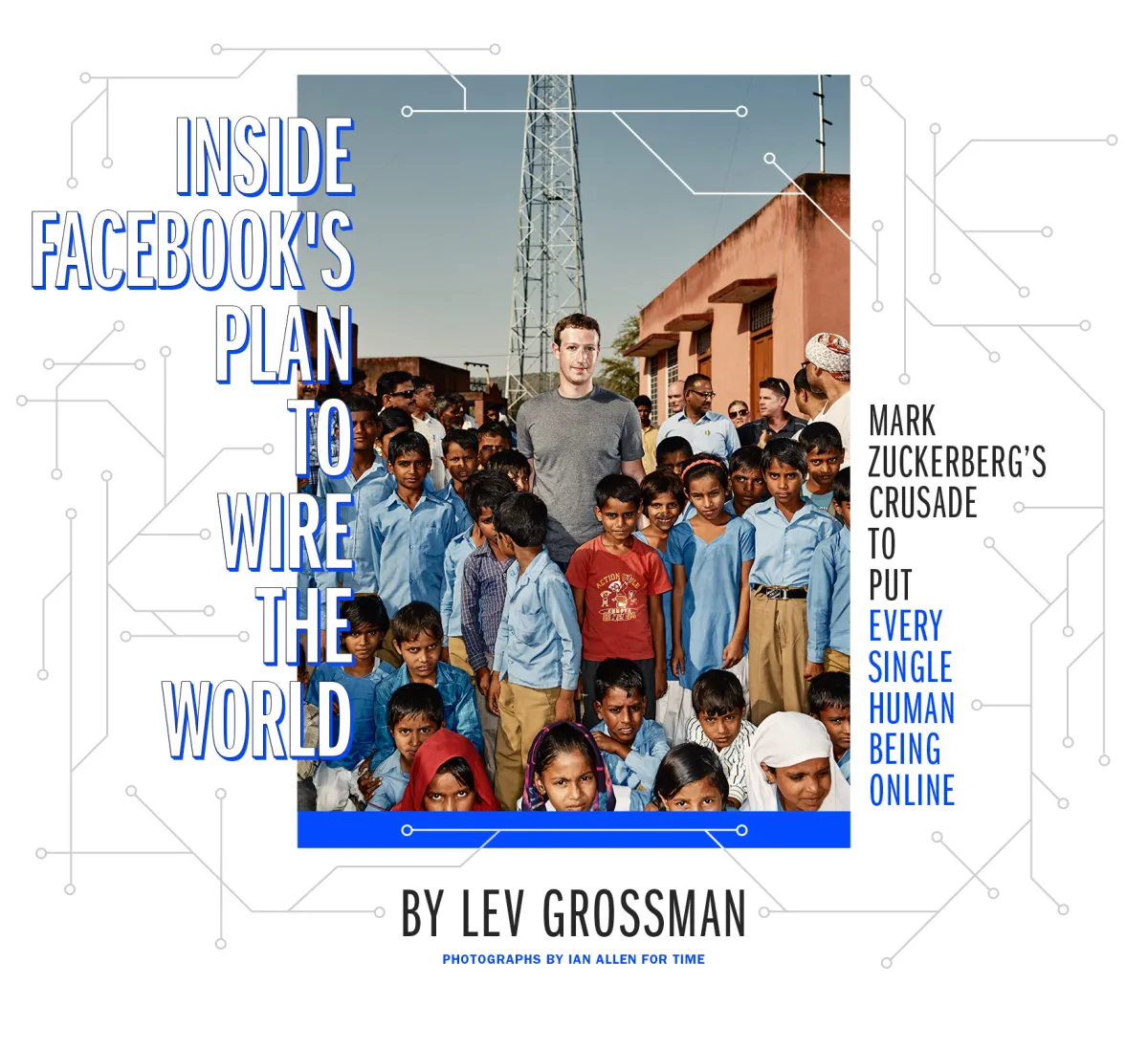

Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook’s Plan to Wire the World

It’s a dusty town, and the roads are narrow and unpaved. A third of the people here live below the poverty line, and the homes are mostly concrete blockhouses. Afternoons are hot and silent. There are goats. It is not ordinarily the focus of global media attention, but it is today, because today the 14th wealthiest man in the world, Mark Zuckerberg, has come to Chandauli.

Ostensibly, Zuckerberg is here to look at a new computer center and to have other people, like me, look at him looking at it. But he’s also here in search of something less easily definable.

I’ve interviewed Zuckerberg before—I wrote about him in 2010, when he was TIME’s Person of the Year—and as far as I can tell, he is not a man much given to quiet reflection. But this year he reached a point in his life when even someone as un-introspective as he is might reasonably pause and reflect. Facebook, the company of which he is chairman, CEO and co-founder, turned 10 this year. Zuckerberg himself turned 30. (If you’re wondering, he didn’t have a party. For his 30th birthday, on May 14, Zuckerberg flew back east to watch his younger sister defend her Ph.D. in classics at Princeton.) For years, Facebook has been the quintessential Silicon Valley startup, helmed by the global icon of brash, youthful success. But Facebook isn’t a startup anymore, and Zuckerberg is no longer especially youthful. He’s just brash and successful.

At 30, Zuckerberg still comes off as young for his age. He says “like” and “awesome” a lot. (The other word he overuses is folks .) He dresses like an undergraduate: he’s in a plain gray T-shirt today, presumably because it’s too hot in Chandauli for a hoodie. When he speaks in public, he still has the air of an enthusiastic high school kid delivering an oral report. In social situations his gaze darts around erratically, only occasionally coming to rest on the face of the person he’s talking to.

But he’s not the angry, lonely introvert of The Social Network . That character may have been useful for dramatic purposes, but he never actually existed. In person, one-on-one, Zuckerberg is a warm presence, not a cold one. He hasn’t been lonely for a long time: he met Priscilla Chan, the woman who would become his wife, in his sophomore year at Harvard. In October he stunned an audience in Beijing when he gave an interview in halting but still credible Mandarin. Watch the video: he’s grinning his face off. He’s having a blast. He’s like that most of the time.

Zuckerberg can be extremely awkward in conversation, but that’s not because he’s nervous or insecure; nervous, insecure people rarely become the 14th richest person in the world. Zuckerberg is in fact supremely confident, almost to the point of being aggressive. But casual conversation is supposed to be playful, and he doesn’t do playfulness well. He gets impatient with the slowness, the low bandwidth of ordinary speech, hence the darting gaze. He has too much the engineer’s approach to conversation: it’s less about social interaction than about swapping information as rapidly as possible. “Mark is one of the best listeners I’ve ever met,” says Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s COO. “When you talk to Mark, he doesn’t just listen to what you say. He listens to what you didn’t say, what you emphasized. He digests the information, he comes back to you and asks five follow-up questions. He’s incredibly inquisitive.”

I have found this to be true—sometimes he gives the impression of having thought through what I’m saying better than I have—with the caveat that listening to me (unlike, I imagine, listening to Sandberg, or for that matter speaking Chinese) doesn’t consume enough of his bandwidth to keep his attention from wandering off in search of more data. Probably it’s not an accident that he invented an entirely new way to socialize: efficiently, remotely, in bulk.

Zuckerberg has been thinking about Facebook’s long-term future at least since the site exceeded a billion users in 2012. “This was something that had been this rallying cry inside the company,” he says. “And it was like, O.K., wow, so what do we do now?” (It’s tempting to clean up Zuckerberg’s quotes to give them more gravitas, but that’s how he talks.) One answer was to put down bets on emerging platforms and distribution channels, in the form of some big-ticket acquisitions: the photo-sharing app Instagram for $1 billion (a head snapper at the time, but in hindsight a steal); the virtual-reality startup Oculus Rift for $2 billion; the messaging service Whats App for $22 billion (still a head snapper). But what about the bigger picture—the even bigger picture? “We were thinking about the first decade of the company, and what were the next set of big things that we wanted to take on, and we came to this realization that connecting a billion people is an awesome milestone, but there’s nothing magical about the number 1 billion. If your mission is to connect the world, then a billion might just be bigger than any other service that had been built. But that doesn’t mean that you’re anywhere near fulfilling the actual mission.”

Fulfilling the actual mission, connecting the entire world, wouldn’t actually, literally be possible unless everybody in the world were on the Internet. So Zuckerberg has decided to make sure everybody is. This sounds like the kind of thing you say you’re going to do but never actually do, but Zuckerberg is doing it. He is in Chandauli today on a campaign to make sure that actually, literally every single human being on earth has an Internet connection. As Sandberg puts it (she’s better at sound bites than Zuckerberg): “If the first decade was starting the process of connecting the world, the next decade is helping connect the people who are not yet connected and watching what happens.”

Part of Zuckerberg’s problem-solving methodology appears to be to start from the position that all problems are solvable, and moreover solvable by him. As a first step, he crunched some numbers. They were big numbers, but he’s comfortable with those: if he does nothing else, Zuckerberg scales. The population of the earth is currently about 7.2 billion. There are about 2.9 billion people on the Internet, give or take a hundred million. That leaves roughly 4.3 billion people who are offline and need to be put online. “What we figured out was that in order to get everyone in the world to have basic access to the Internet, that’s a problem that’s probably billions of dollars,” he says. “Or maybe low tens of billions. With the right innovation, that’s actually within the range of affordability.”

Zuckerberg made some calls, and the result was the formation last year of a coalition of technology companies that includes Ericsson, Qualcomm, Nokia and Samsung. The name of this group is Internet.org, and it describes itself as “a global partnership between technology leaders, nonprofits, local communities and experts who are working together to bring the Internet to the two-thirds of the world’s population that doesn’t have it.”

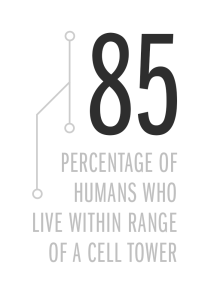

Based on that, you might think that -Internet.org will be setting up free wi-fi in the Sahara and things like that, but as it turns out, the insight that makes the whole thing feasible is that it’s not about building new infrastructure. Using maps and data from Ericsson and NASA—-including a fascinating data set called the Gridded Population of the World, which maps the geographical distribution of the human species—plus information mined from Facebook’s colossal user base, the -Internet.org team at Facebook figured out that most of their work was already done. Most humans, or about 85% of them, already have Internet access, at least in the minimal sense that they live within range of a cell tower with at least a 2G data network. They’re just not using it.

Facebook has a plan for the other 15%, a blue-sky wi-fi-in-the-Sahara-type scheme involving drones and satellites and lasers, which we’ll get to later, but that’s a long-term project. The subset of that 85% of people who could be online but aren’t: they’re the low-hanging fruit.

But why aren’t they online already? To not be on the Internet when you could be: from the vantage point of Silicon Valley, that is an alien state of being. The issues aren’t just technical; they’re also social and economic and cultural. Maybe these are people who don’t have the money for a phone and data plan. Maybe they don’t know enough about the Internet. Or maybe they do know enough about it and just don’t care, because it’s totally irrelevant to their day-to-day lives.

( Interactive: How Much Time Have You Wasted on Facebook? )

You’d think Zuckerberg the arch-hacker wouldn’t sully his hands with this kind of soft-science stuff, but in fact he doesn’t blink at it. He attacks social/economic/cultural problems the same way he attacks technical ones; in fact it’s not clear that he makes much of a distinction between them. Human nature is just more code to hack—never forget that before he dropped out, Zuckerberg was a psych major. “If you grew up and you never had a computer,” he says, “and you’ve never had access to the Internet, and somebody asked you if you wanted a data plan, your answer would probably be, ‘What’s a data plan?’ Right? Or, ‘Why would I want that?’ So the problems are different from what people think, but they actually end up being very tractable.”

Zuckerberg is a great one for breaking down messy, wonky problems into manageable chunks, and when you break this one down it falls into three buckets. Business: making the data cheap enough that people in developing countries can pay for it. Technology: simplifying the content and/or services on offer so that they work in ultra-low-bandwidth situations and on a gallimaufry of old, low-end hardware. And content: coming up with content and/or services compelling enough to somebody in the third world that they would go through the trouble of going online to get them. Basically the challenge is to imagine what it would be like to be a poor person—the kind of person who lives somewhere like Chandauli.

Engineering Empathy

The Facebook campus in Menlo Park, Calif., isn’t especially conducive to this. It’s about as far from Chandauli, geographically, aesthetically and socioeconomically, as you can get on this planet. When you walk into Facebook’s headquarters for the first time, the overwhelming impression you get is of raw, unbridled plenitude. There are bowls overflowing with free candy and fridges crammed with free Diet Coke and bins full of free Kind bars. They don’t have horns with fruits and vegetables spilling out of them, but they might as well.

The campus is built around a sun-drenched courtyard crisscrossed by well-groomed employees strolling and laughing and wheeling bikes. Those Facebookies who aren’t strolling and laughing and wheeling are bent over desks in open-plan office areas, looking ungodly busy with some exciting, impossibly hard task that they’re probably being paid a ton of money to perform. Arranged around the courtyard (where the word hack appears in giant letters, clearly readable on Google Earth if not from actual outer space) are -restaurants—Lightning Bolt’s Smoke Shack, Teddy’s Nacho Royale, Big Tony’s Pizzeria—that seem like normal restaurants right up until you try to pay, when you realize they don’t accept money. Neither does the barbershop or the dry cleaner or the ice cream shop. It’s all free.

You’re not even in the first world anymore, you’re beyond that. This is like the zeroth world. And it’s just the shadow of things to come: a brand-new campus, designed by Frank Gehry, natch, is under construction across the expressway. It’s slated to open next year.

(Because of the limits of space and time, a lot of Silicon Valley companies don’t build new headquarters; they just take over the discarded offices of older firms, like hermit crabs. Facebook’s headquarters used to belong to Sun Microsystems, a onetime power-house of innovation that collapsed and was acquired by Oracle in 2009. When Facebook moved in, Zuckerberg made over the whole place, but he didn’t change the sign out front, he just turned it around and put Facebook on the other side. The old sign remains as a reminder of what happens when you take your eye off the ball.)

As Zuckerberg himself puts it, when you work at a place like Facebook, “it’s easy to not have empathy for what the experience is for the majority of people in the world.” To avoid any possible empathy shortfall, Facebook is engineering empathy artificially. “We re-created with the Ericsson network guys the network conditions that you have in rural India,” says Javier Olivan, Facebook’s head of growth. “Then we brought in some phones, like very low-end Android, and we invited guys from the Valley here—the eBay guys, the Apple guys. It’s like, Hey, come and test your applications in these conditions! Nothing worked.” It was a revelation: for most of humanity, the Internet is broken. “I force a lot of the guys to use low-end phones now,” Olivan says. “You need to feel the pain.”

Needless to say, in all the time I spent at Facebook, I never heard anybody call it that. They just called it low-end. But his point stands.

Internet 911

Not to keep you in suspense, but Facebook figured out the answer to how to get all of humanity online. It’s an app.

Here’s the idea. First, you look at a particular geographical region that’s underserved, Internet-wise, and figure out what content might be compelling enough to lure its inhabitants online. Then you gather that content up, make sure it’s in the right language and wrap it up in a slick app. Then you go to the local cell-phone providers and convince as many of them as possible that they should offer the content in your app for free, with no data charges. There you go: anybody who has a data-capable phone has Internet access—or at least access to a curated, walled sliver of the Internet—for free.

This isn’t hypothetical: Internet.org released this app in Zambia in July. It launched in Tanzania in October. In Zambia, the app’s content offerings include AccuWeather, Wikipedia, Google Search, the Mobile Alliance for Maternal Action—there’s a special emphasis on women’s rights and women’s health—and a few job-listing sites. And Facebook. A company called Airtel (the local subsidiary of an Indian telco) agreed to offer access for nothing. “I think about it like 911 in the U.S.,” Zuckerberg says. “You don’t have to have a phone plan, but if there’s an emergency, if there’s a fire or you’re getting robbed, you can always call and get access to those kinds of basic services. And I kind of think there should be that for the Internet too.”

This makes it sound simpler than it is. For Facebook to simply reach out from Silicon Valley and blanket a country like Zambia with content requires exactly the kind of nuance and sensitivity that Facebook is not famous for. Just figuring out what language the content should be in is a challenge. The official language in Zambia is English, but the CIA’s World Factbook lists 17 languages spoken there. And Zambia is cake compared with India, which has no national language but officially recognizes 22 of them; unofficially, according to a 2011 census, India’s 1.2 billion inhabitants speak a total of 1,635 languages. It is, in the words of one Facebook executive, “brutally localized.”

But the hardest part is persuading the cell-phone companies to offer the content for free. The idea is that they should make the app available as a loss leader, and once customers see it (inside Facebook they talk about people being “exposed to data”), they’ll want more and be willing to pay for it. In other words, data is addictive, so you make the first taste free.

This part is crucial. It’s not enough for the app to work—the scheme has to replicate itself virally, driven by cell-phone companies acting in their own self-interest. It’s a business hack as much as it is a technical one. Before Zambia, Facebook tried a limited run in the Philippines with a service provider called Globe, which reported nearly doubling its registered mobile data-service users over three months. There’s your proof of concept.

The more test cases Facebook can show off, the easier it will be to persuade telcos to sign on. The more telcos that sign on, the more data Facebook compiles and the stronger its case gets. Eventually the model begins to spread by itself, region by region, country by country, and as it replicates it draws more and more people online. “Each time we do the integration, we tune different things with the operator and it gets better and better and better,” Zuckerberg says. “The thing that we haven’t proven definitely yet is that it’s valuable for them to offer those basic services for free indefinitely, rather than just as a trial. Once we have that, we feel like we’ll be ready to go around to all the other operators in the world and say, This is definitely a good model for you. You should do this.” (There’s a quiet arrogance to it, as there is to a lot of what Facebook does. Facebook is basically saying, Hey, third-world cell-phone operators, by the way, your business model? Let us optimize it for you.)

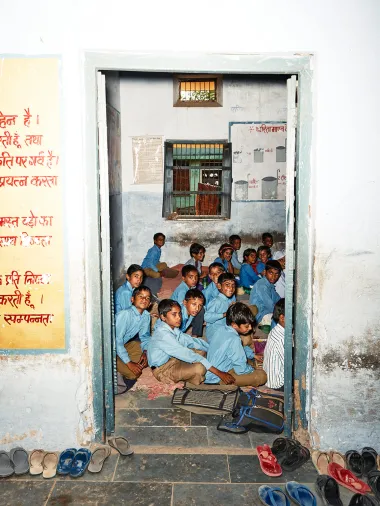

Although when you make a plan in Menlo Park and try to execute it in rural India, not everything is going to go as planned. That was amply demonstrated by Zuckerberg’s visit to Chandauli. It was meant to be a quiet, discreet affair, but Zuckerberg’s schedule got tight, so instead of driving down from New Delhi he had to be flown in by helicopter. Before you land a helicopter in India, you have to check in with the local police. The local police tipped off the local media, which meant that when Zuckerberg arrived he was enveloped in a hot, dusty scrum of journalists, police, village elders, curious onlookers, private security and kids in school uniforms who thought the whole thing was hilarious.

Education is one of Zuckerberg’s interests as a philanthropist—earlier this year he and his wife donated $120 million to Bay Area schools—and he ducked into a local school to see a classroom. “There were, like, 40 students sitting on the floor, and then the guy running it was saying that there were 1.4 million schools and this was one of the better ones,” he said later—he can never resist a statistic. “There was no power. There are no toilets in the whole village!” Eventually, Zuckerberg’s handlers got him into the computer center, a single spacious, airy room with a laser printer, a copy machine and a couple dozen laptops, each one with a student at it. It was then ascertained that the power was out in Chandauli, as it often is, so even though Zuckerberg had come 7,500 miles to see a display of Internet connectivity, the Internet was down.

Since he was there, Zuckerberg had a few heavily stage-managed conversations with the kids, which showcased in equal measure his genuine good humor and heart-stopping social awkwardness. This was followed by an apparently spontaneous but still kind of amazing musical performance by a guy with a one-stringed instrument called a bhapang . Then the world’s 14th richest man was photographed in the school courtyard, whisked back to his SUV, convoyed back to the heli-pad and choppered back to New Delhi in a huge orange helicopter in time for a meeting with the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi. I’m told he changed into a suit for the occasion.

On the way, I asked Zuckerberg if his life ever seemed surreal to him. His answer: “Yes.” But I’m not sure he meant it.

Colonialism 2.0

There’s another way to look at what Facebook is doing here, which is that however much the company spins it as altruistic, this campaign is really an act of self–serving techno-colonialism. Facebook’s membership is already almost half the size of the Internet. Facebook, like soylent green, is made of people, and it always needs more of them. Over the long term, if Facebook is going to keep growing, it’s going to have to make sure it’s got a bigger Internet to grow in.

Hence Internet.org. And if that Internet is seeded by people who initially have limited options online, of which Facebook (and no other social network) is one, all the better. Facebook started up a similar program in 2010 called Facebook Zero, targeted at developing markets, which made a streamlined mobile version of Facebook available for free, with no data charges. At the time this was not considered altruism; it was just good, aggressive marketing (it’s actually illegal in Chile because it violates Chilean Net-neutrality laws). Facebook Zero bears a strong family resemblance to Internet.org.

There’s something distasteful about the whole business: a global campaign by a bunch of Silicon Valley jillionaires to convert literally everybody into data consumers, to make sure no eyeballs anywhere go unexposed to their ads. Everybody must be integrated into the vast cultural homogeneity that is the Internet. It’s like a zombie plague: World War Z(uckerberg). After all, it’s not as though anybody asked two-thirds of humanity whether they wanted to be put online. It makes one want to say, There are still people here on God’s green earth who can conduct their social lives without being marketed to. Can’t we for God’s sake leave them alone?

( Interactive: Who Are Your Happiest Friends on Facebook? )

I aired this point of view to a few Facebook executives. Predictably, I didn’t get a lot of traction. Zuckerberg’s (unruffled) response was that Internet.org isn’t about growing Facebook for the simple reason that there isn’t any money in showing ads to the people that use the app, because they don’t have any. “When most people ask about a business growing, what they really mean is growing revenue, not just growing the number of people using a service,” he says. “Traditional businesses would view people using your service that you don’t make money from as a cost.”

The most he’ll cop to is that it might pan out as a business in the very, very long term. “There are good examples of -companies—Coca-Cola is one—that invested before there was a huge market in countries, and I think that ended up playing out to their benefit for decades to come. I do think something like that is likely to be true here. So even though there’s no clear path that we can see to where this is going to be a very profitable thing for us, I generally think if you do good things for people in the world, that that comes back and you benefit from it over time.”

Sandberg says something similar: “When we’ve been accused of doing this for our own profit, the joke we have is, God, if we were trying to maximize profits, we have a long list of ad products to build! We’d have to work our way pretty far down that list before we got to this.”

The other way of looking at Internet.org is the way Internet.org wants to be looked at: it’s spreading Internet access because the Internet makes people’s lives better. It improves the economy and enhances education and leads to better health outcomes. In February, Deloitte published a study—-admittedly commissioned by Facebook—that found that in India alone, extending Internet access from its current level, 15%, to a level comparable with that of more developed countries, say, 75%, would create 65 million jobs, cut cases of extreme poverty by 28% and reduce infant mortality by 85,000 deaths a year. Bottom line, this isn’t about money; it’s about creating wealth and saving lives.

The issue of public health is especially important, because one of the knocks on -Internet.org is that the need for connectivity is trivial compared with more fundamental needs like food and water and medicine. A few months after Zuckerberg announced Internet.org, Bill Gates appeared to take that line in an interview with the Financial Times . “Hmm, which is more important, connectivity or malaria vaccine?” Gates said. “If you think connectivity is the key thing, that’s great. I don’t.” And more succinctly: “As a priority? It’s a joke.” Zuckerberg brought this up himself. “I talked to him after that,” he says. “I called him up and I was like, ‘What’s up, dude?’ But he was misquoted, and he even corrected it afterward. He was like, ‘No, I fully believe that this is critical.’” The Financial Times never ran a correction—but the Deloitte study does make a convincing case that connectivity and health care are not unrelated.

As for the encroaching cultural homogeneity that comes with the Internet, there’s more than one point of view there too. I talked about it with Mary Good, a cultural anthropologist at Wake Forest who’s done fieldwork on the impact of Facebook in the Polynesian archipelago of Tonga. “I have found that the introduction of Facebook does not become a Western technology behemoth ruthlessly steamrolling across a passive new territory of eager users,” she wrote in an email. “Instead, adopting new digital media and incorporating it into their lives is a process, and sometimes facilitates the maintenance of more long-standing traditions.”