Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Case Presentation

Patient Overview

M.J. is a 25-year-old, African American female presenting to her PCP with complaints of fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath with minimal activity. Her friends and family have told her she appears pale, and combined with her recent symptoms she has decided to get checked out. She also states that she has noticed her hair and fingernails becoming extremely thin and brittle, causing even more concern. The patient first started noticing these symptoms a few months ago and they have been getting progressively worse. Upon initial assessment, her mucosal membranes and conjunctivae are pale. She denies pain at this time, but describes an intermittent dry, soreness of her tongue.

Vital Signs:

Temperature – 37 C (98.8 F)

HR – 95

BP – 110/70 (83)

Lab Values:

Hgb- 7 g/dL

Serum Iron – 40 mcg/dL

Transferrin Saturation – 15%

Medical History

- Diagnosed with peptic ulcer disease at age 21 – controlled with PPI pharmacotherapy

- IUD placement 3 months ago – reports an increase in menstrual bleeding since placement

Surgical History

- No past surgical history reported

Family History

- Diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia at 24 years old during pregnancy with patient – on daily supplement

- Otherwise healthy

- Diagnosis of hypertension – controlled with diet and exercise

- No siblings

Social History

- Vegetarian – patient states she has been having weird cravings for ice cubes lately

- Living alone in an apartment close to work in a lower-income community

- Works full time at a clothing department store

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 13 September 2021

Critical iron deficiency anemia with record low hemoglobin: a case report

- Audrey L. Chai ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5009-0468 1 ,

- Owen Y. Huang 1 ,

- Rastko Rakočević 2 &

- Peter Chung 2

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 15 , Article number: 472 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

34k Accesses

8 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Anemia is a serious global health problem that affects individuals of all ages but particularly women of reproductive age. Iron deficiency anemia is one of the most common causes of anemia seen in women, with menstruation being one of the leading causes. Excessive, prolonged, and irregular uterine bleeding, also known as menometrorrhagia, can lead to severe anemia. In this case report, we present a case of a premenopausal woman with menometrorrhagia leading to severe iron deficiency anemia with record low hemoglobin.

Case presentation

A 42-year-old Hispanic woman with no known past medical history presented with a chief complaint of increasing fatigue and dizziness for 2 weeks. Initial vitals revealed temperature of 36.1 °C, blood pressure 107/47 mmHg, heart rate 87 beats/minute, respiratory rate 17 breaths/minute, and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. She was fully alert and oriented without any neurological deficits. Physical examination was otherwise notable for findings typical of anemia, including: marked pallor with pale mucous membranes and conjunctiva, a systolic flow murmur, and koilonychia of her fingernails. Her initial laboratory results showed a critically low hemoglobin of 1.4 g/dL and severe iron deficiency. After further diagnostic workup, her profound anemia was likely attributed to a long history of menometrorrhagia, and her remarkably stable presentation was due to impressive, years-long compensation. Over the course of her hospital stay, she received blood transfusions and intravenous iron repletion. Her symptoms of fatigue and dizziness resolved by the end of her hospital course, and she returned to her baseline ambulatory and activity level upon discharge.

Conclusions

Critically low hemoglobin levels are typically associated with significant symptoms, physical examination findings, and hemodynamic instability. To our knowledge, this is the lowest recorded hemoglobin in a hemodynamically stable patient not requiring cardiac or supplemental oxygen support.

Peer Review reports

Anemia and menometrorrhagia are common and co-occurring conditions in women of premenopausal age [ 1 , 2 ]. Analysis of the global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010 revealed that the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia, although declining every year, remained significantly high, affecting almost one in every five women [ 1 ]. Menstruation is considered largely responsible for the depletion of body iron stores in premenopausal women, and it has been estimated that the proportion of menstruating women in the USA who have minimal-to-absent iron reserves ranges from 20% to 65% [ 3 ]. Studies have quantified that a premenopausal woman’s iron storage levels could be approximately two to three times lower than those in a woman 10 years post-menopause [ 4 ]. Excessive and prolonged uterine bleeding that occurs at irregular and frequent intervals (menometrorrhagia) can be seen in almost a quarter of women who are 40–50 years old [ 2 ]. Women with menometrorrhagia usually bleed more than 80 mL, or 3 ounces, during a menstrual cycle and are therefore at greater risk for developing iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia. Here, we report an unusual case of a 42-year-old woman with a long history of menometrorrhagia who presented with severe anemia and was found to have a record low hemoglobin level.

A 42-year-old Hispanic woman with no known past medical history presented to our emergency department with the chief complaint of increasing fatigue and dizziness for 2 weeks and mechanical fall at home on day of presentation.

On physical examination, she was afebrile (36.1 °C), blood pressure was 107/47 mmHg with a mean arterial pressure of 69 mmHg, heart rate was 87 beats per minute (bpm), respiratory rate was 17 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. Her height was 143 cm and weight was 45 kg (body mass index 22). She was fully alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation without any neurological deficits and was speaking in clear, full sentences. She had marked pallor with pale mucous membranes and conjunctiva. She had no palpable lymphadenopathy. She was breathing comfortably on room air and displayed no signs of shortness of breath. Her cardiac examination was notable for a grade 2 systolic flow murmur. Her abdominal examination was unremarkable without palpable masses. On musculoskeletal examination, her extremities were thin, and her fingernails demonstrated koilonychia (Fig. 1 ). She had full strength in lower and upper extremities bilaterally, even though she required assistance with ambulation secondary to weakness and used a wheelchair for mobility for 2 weeks prior to admission. She declined a pelvic examination. No bleeding was noted in any part of her physical examination.

Koilonychia, as seen in our patient above, is a nail disease commonly seen in hypochromic anemia, especially iron deficiency anemia, and refers to abnormally thin nails that have lost their convexity, becoming flat and sometimes concave in shape

She was admitted directly to the intensive care unit after her hemoglobin was found to be critically low at 1.4 g/dL on two consecutive measurements with an unclear etiology of blood loss at the time of presentation. Note that no intravenous fluids were administered prior to obtaining the hemoglobin levels. Upon collecting further history from the patient, she revealed that she has had a lifetime history of extremely heavy menstrual periods: Since menarche at the age of 10 years when her periods started, she has been having irregular menstruation, with periods occurring every 2–3 weeks, sometimes more often. She bled heavily for the entire 5–7 day duration of her periods; she quantified soaking at least seven heavy flow pads each day with bright red blood as well as large-sized blood clots. Since the age of 30 years, her periods had also become increasingly heavier, with intermittent bleeding in between cycles, stating that lately she bled for “half of the month.” She denied any other sources of bleeding.

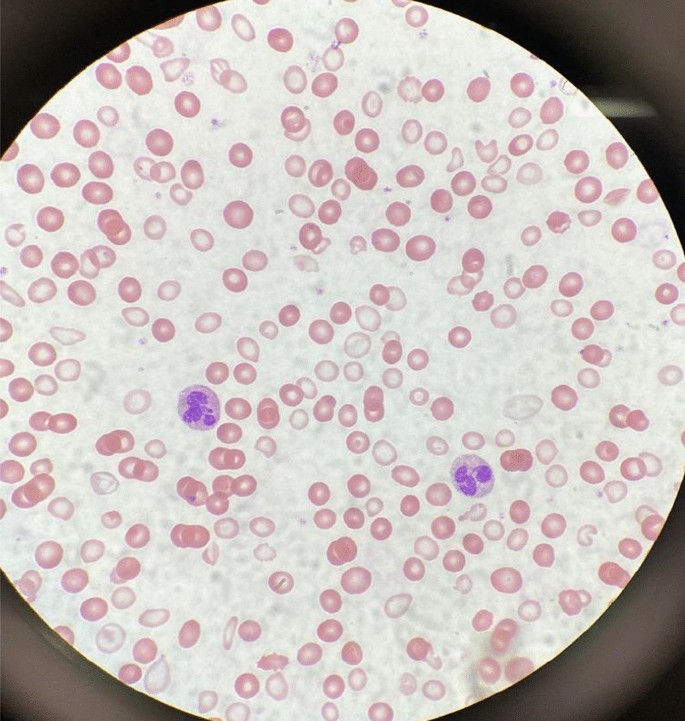

Initial laboratory data are summarized in Table 1 . Her hemoglobin (Hgb) level was critically low at 1.4 g/dL on arrival, with a low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of < 50.0 fL. Hematocrit was also critically low at 5.8%. Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) was elevated to 34.5%, and absolute reticulocyte count was elevated to 31 × 10 9 /L. Iron panel results were consistent with iron deficiency anemia, showing a low serum iron level of 9 μg/dL, elevated total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) of 441 μg/dL, low Fe Sat of 2%, and low ferritin of 4 ng/mL. Vitamin B12, folate, hemolysis labs [lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), haptoglobin, bilirubin], and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) labs [prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), fibrinogen, d -dimer] were all unremarkable. Platelet count was 232,000/mm 3 . Peripheral smear showed erythrocytes with marked microcytosis, anisocytosis, and hypochromia (Fig. 2 ). Of note, the patient did have a positive indirect antiglobulin test (IAT); however, she denied any history of pregnancy, prior transfusions, intravenous drug use, or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Her direct antiglobulin test (DAT) was negative.

A peripheral smear from the patient after receiving one packed red blood cell transfusion is shown. Small microcytic red blood cells are seen, many of which are hypochromic and have a large zone of pallor with a thin pink peripheral rim. A few characteristic poikilocytes (small elongated red cells also known as pencil cells) are also seen in addition to normal red blood cells (RBCs) likely from transfusion

A transvaginal ultrasound and endometrial biopsy were offered, but the patient declined. Instead, a computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis with contrast was performed, which showed a 3.5-cm mass protruding into the endometrium, favored to represent an intracavitary submucosal leiomyoma (Fig. 3 ). Aside from her abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), the patient was without any other significant personal history, family history, or lab abnormalities to explain her severe anemia.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was obtained revealing an approximately 3.5 × 3.0 cm heterogeneously enhancing mass protruding into the endometrial canal favored to represent an intracavitary submucosal leiomyoma

The patient’s presenting symptoms of fatigue and dizziness are common and nonspecific symptoms with a wide range of etiologies. Based on her physical presentation—overall well-appearing nature with normal vital signs—as well as the duration of her symptoms, we focused our investigation on chronic subacute causes of fatigue and dizziness rather than acute medical causes. We initially considered a range of chronic medical conditions from cardiopulmonary to endocrinologic, metabolic, malignancy, rheumatologic, and neurological conditions, especially given her reported history of fall. However, once the patient’s lab work revealed a significantly abnormal complete blood count and iron panel, the direction of our workup shifted towards evaluating hematologic causes.

With such a critically low Hgb on presentation (1.4 g/dL), we evaluated for potential sources of blood loss and wanted to first rule out emergent, dangerous causes: the patient’s physical examination and reported history did not elicit any concern for traumatic hemorrhage or common gastrointestinal bleeding. She denied recent or current pregnancy. Her CT scan of abdomen and pelvis was unremarkable for any pathology other than a uterine fibroid. The microcytic nature of her anemia pointed away from nutritional deficiencies, and she lacked any other medical comorbidities such as alcohol use disorder, liver disease, or history of substance use. There was also no personal or family history of autoimmune disorders, and the patient denied any history of gastrointestinal or extraintestinal signs and/or symptoms concerning for absorptive disorders such as celiac disease. We also eliminated hemolytic causes of anemia as hemolysis labs were all normal. We considered the possibility of inherited or acquired bleeding disorders, but the patient denied any prior signs or symptoms of bleeding diatheses in her or her family. The patient’s reported history of menometrorrhagia led to the likely cause of her significant microcytic anemia as chronic blood loss from menstruation leading to iron deficiency.

Over the course of her 4-day hospital stay, she was transfused 5 units of packed red blood cells and received 2 g of intravenous iron dextran. Hematology and Gynecology were consulted, and the patient was administered a medroxyprogesterone (150 mg) intramuscular injection on hospital day 2. On hospital day 4, she was discharged home with follow-up plans. Her hemoglobin and hematocrit on discharge were 8.1 g/dL and 24.3%, respectively. Her symptoms of fatigue and dizziness had resolved, and she was back to her normal baseline ambulatory and activity level.

Discussion and conclusions

This patient presented with all the classic signs and symptoms of iron deficiency: anemia, fatigue, pallor, koilonychia, and labs revealing marked iron deficiency, microcytosis, elevated RDW, and low hemoglobin. To the best of our knowledge, this is the lowest recorded hemoglobin in an awake and alert patient breathing ambient air. There have been previous reports describing patients with critically low Hgb levels of < 2 g/dL: A case of a 21-year old woman with a history of long-lasting menorrhagia who presented with a Hgb of 1.7 g/dL was reported in 2013 [ 5 ]. This woman, although younger than our patient, was more hemodynamically unstable with a heart rate (HR) of 125 beats per minute. Her menorrhagia was also shorter lasting and presumably of larger volume, leading to this hemoglobin level. It is likely that her physiological regulatory mechanisms did not have a chance to fully compensate. A 29-year-old woman with celiac disease and bulimia nervosa was found to have a Hgb of 1.7 g/dL: she presented more dramatically with severe fatigue, abdominal pain and inability to stand or ambulate. She had a body mass index (BMI) of 15 along with other vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies, leading to a mixed picture of iron deficiency and non-iron deficiency anemia [ 6 ]. Both of these cases were of reproductive-age females; however, our patient was notably older (age difference of > 20 years) and had a longer period for physiologic adjustment and compensation.

Lower hemoglobin, though in the intraoperative setting, has also been reported in two cases—a patient undergoing cadaveric liver transplantation who suffered massive bleeding with associated hemodilution leading to a Hgb of 0.6 g/dL [ 7 ] and a patient with hemorrhagic shock and extreme hemodilution secondary to multiple stab wounds leading to a Hgb of 0.7 g/dL [ 8 ]. Both patients were hemodynamically unstable requiring inotropic and vasopressor support, had higher preoperative hemoglobin, and were resuscitated with large volumes of colloids and crystalloids leading to significant hemodilution. Both were intubated and received 100% supplemental oxygen, increasing both hemoglobin-bound and dissolved oxygen. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that the deep anesthesia and decreased body temperature in both these patients minimized oxygen consumption and increased the available oxygen in arterial blood [ 9 ].

Our case is remarkably unique with the lowest recorded hemoglobin not requiring cardiac or supplemental oxygen support. The patient was hemodynamically stable with a critically low hemoglobin likely due to chronic, decades-long iron deficiency anemia of blood loss. Confirmatory workup in the outpatient setting is ongoing. The degree of compensation our patient had undergone is impressive as she reported living a very active lifestyle prior to the onset of her symptoms (2 weeks prior to presentation), she routinely biked to work every day, and maintained a high level of daily physical activity without issue.

In addition, while the first priority during our patient’s hospital stay was treating her severe anemia, her education became an equally important component of her treatment plan. Our institution is the county hospital for the most populous county in the USA and serves as a safety-net hospital for many vulnerable populations, most of whom have low health literacy and a lack of awareness of when to seek care. This patient had been experiencing irregular menstrual periods for more than three decades and never sought care for her heavy bleeding. She, in fact, had not seen a primary care doctor for many years nor visited a gynecologist before. We emphasized the importance of close follow-up, self-monitoring of her symptoms, and risks with continued heavy bleeding. It is important to note that, despite the compensatory mechanisms, complications of chronic anemia left untreated are not minor and can negatively impact cardiovascular function, cause worsening of chronic conditions, and eventually lead to the development of multiorgan failure and even death [ 10 , 11 ].

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Kassebaum NJ. The global burden of anemia. Hematol Oncol Clin. 2016;30(2):247–308.

Article Google Scholar

Donnez J. Menometrorrhagia during the premenopause: an overview. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(sup1):1114–9.

Cook JD, Skikne BS, Lynch SR, Reusser ME. Estimates of iron sufficiency in the US population. Blood. 1986;68(3):726–31.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Palacios S. The management of iron deficiency in menometrorrhagia. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(sup1):1126–30.

Can Ç, Gulactı U, Kurtoglu E. An extremely low hemoglobin level due to menorrhagia and iron deficiency anemia in a patient with mental retardation. Int Med J. 2013;20(6):735–6.

Google Scholar

Jost PJ, Stengel SM, Huber W, Sarbia M, Peschel C, Duyster J. Very severe iron-deficiency anemia in a patient with celiac disease and bulimia nervosa: a case report. Int J Hematol. 2005;82(4):310–1.

Kariya T, Ito N, Kitamura T, Yamada Y. Recovery from extreme hemodilution (hemoglobin level of 0.6 g/dL) in cadaveric liver transplantation. A A Case Rep. 2015;4(10):132.

Dai J, Tu W, Yang Z, Lin R. Intraoperative management of extreme hemodilution in a patient with a severed axillary artery. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(5):1204–6.

Koehntop DE, Belani KG. Acute severe hemodilution to a hemoglobin of 1.3 g/dl tolerated in the presence of mild hypothermia. J Am Soc Anesthesiol. 1999;90(6):1798–9.

Georgieva Z, Georgieva M. Compensatory and adaptive changes in microcirculation and left ventricular function of patients with chronic iron-deficiency anaemia. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 1997;17(1):21–30.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lanier JB, Park JJ, Callahan RC. Anemia in older adults. Am Fam Phys. 2018;98(7):437–42.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

No funding to be declared.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Audrey L. Chai & Owen Y. Huang

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Rastko Rakočević & Peter Chung

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AC, OH, RR, and PC managed the presented case. AC performed the literature search. AC, OH, and RR collected all data and images. AC and OH drafted the article. RR and PC provided critical revision of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Audrey L. Chai .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Chai, A.L., Huang, O.Y., Rakočević, R. et al. Critical iron deficiency anemia with record low hemoglobin: a case report. J Med Case Reports 15 , 472 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03024-9

Download citation

Received : 25 March 2021

Accepted : 21 July 2021

Published : 13 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03024-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Menometrorrhagia

- Iron deficiency

- Critical care

- Transfusion

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- ASH Foundation

- Cookie Settings

- Log in or create an account

- Publications

- Diversity Equity and Inclusion

- Global Initiatives

- Resources for Hematology Fellows

- American Society of Hematology

- Hematopoiesis Case Studies

Case Study: 32 Year-Old Female with Anemia and Confusion

- Agenda for Nematology Research

- Precision Medicine

- Genome Editing and Gene Therapy

- Immunologic Treatment

- Research Support and Funding

A board-style question with an explanation and a link to a relevant article is a recurring feature of TraineE-News . The goal of the case study is to clarify specific and timely teaching points in the field of hematology. The following case study focuses on a 32-year-old woman, with no significant past medical history, who presents to the emergency department with several days of worsening confusion. The complete blood count shows a hemoglobin concentration of 9.8 g/dL and platelet count of 34 x 109/L. Creatinine is 3.1 mg/dL and the LDH is 448 IU/L. Review of the peripheral blood smear shows numerous schistocytes. ADAMTS13 level is measured and found to be 68 percent without evidence of a detectable inhibitor. The patient is diagnosed with atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome and eculizumab is started.

Which of the following vaccinations should be administered as soon as possible after initiating eculizumab?

- Seasonal influenza

- Varicella zoster virus

- Hepatitis B

- Meningococcus

Explanation

Meningococcal (Neisseria meningitides) infections have occurred in patients receiving eculizumab, and patients receiving eculizumab should be vaccinated. The patient has evidence of a thrombotic microangiopathy with anemia, schistocytosis, and elevated LDH. When combined with thrombocytopenia and renal failure along with an ADAMTS13 level > 10 percent, the clinical picture suggests atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. While similar to thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), it is not due to a deficiency of ADAMTS13, but rather mutations in the genes for C3, Factors H, B, and I, as well as membrane cofactor protein. The monoclonal antibody eculizumab inhibits the terminal portion of the complement cascade and is approved by the FDA to treat atypical HUS as well as paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). The drug carries an FDA black-box warning about the risk of meningococcal disease and the product insert includes a recommendation to vaccinate patients against meningococcus as well as provide education and counseling. Ideally, the vaccine should be administered at least two weeks prior to initiation of eculizumab in order to allow sufficient immune response. For patients requiring immediate initiation of treatment with eculizumab, vaccination against meningococcus should be done as soon as possible. Should a patient develop evidence of meningoccocus, eculizumab therapy should be stopped.

- Case study submitted by Nathan Connell, MD, Brown University, Providence, RI, Trainee Council Member.

American Society of Hematology. (1). Case Study: 32 Year-Old Female with Anemia and Confusion. Retrieved from https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/female-anemia-confusion .

American Society of Hematology. "Case Study: 32 Year-Old Female with Anemia and Confusion." Hematology.org. https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/female-anemia-confusion (label-accessed November 20, 2024).

"American Society of Hematology." Case Study: 32 Year-Old Female with Anemia and Confusion, 20 Nov. 2024 , https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/female-anemia-confusion .

Citation Manager Formats

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A Case of Severe Aplastic Anemia in a 35-Year-Old Male With a Good Response to Immunosuppressive Therapy

Ekaterina proskuriakova, ranjit b jasaraj, aleyda m san hernandez, anuradha sakhuja, mtanis khoury.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Ekaterina Proskuriakova [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Received 2023 May 1; Accepted 2023 Jun 9; Collection date 2023 Jun.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Aplastic anemia (AA) is a severe but rare hematologic condition associated with hematopoietic failure leading to decreased or total absent hematopoietic precursor cells in the bone marrow. AA presents at any age with equal distribution among gender and race. There are three known mechanisms of AA: direct injuries, immune-mediated disease, and bone marrow failure. The most common etiology of AA is considered to be idiopathic. Patients usually present with non-specific findings, such as easy fatigability, dyspnea on exertion, pallor, and mucosal bleeding. The primary treatment of AA is to remove the offending agent. In patients in whom the reversible cause was not found, patient management depends on age, disease severity, and donor availability. Here, we present a case of a 35-year-old male who presented to the emergency room with profuse bleeding after a deep dental cleaning. He was found to have pancytopenia on his laboratory panel and had an excellent response to immunosuppressive therapy.

Keywords: eltrombopag, anti-thymocyte globulin (atg), hypocellular bone marrow, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (pnh), severe aplastic anemia

Introduction

Aplastic anemia (AA) is a rare condition characterized by the combination of hypoplasia or aplasia of the bone marrow and pancytopenia in at least two of the three main lines of cells: red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and platelets [ 1 ]. An estimated incidence of this disease is 0.6 to 6.1/million per year with a sex ratio of about 1:1 [ 2 ]. AA is more common in Asia than in Western countries [ 3 ]. This could reflect the variability of exposure to different environmental factors, such as drugs, chemicals, viral pathogens, or genetic predisposition. Although this condition could be seen in any age group, two incidence peaks of AA are reported: in young adults (20-25 years old) and the elderly population with a peak after the age of 60 [ 4 , 5 ].

The three main mechanisms of AA are direct injuries, immune-mediated disease, and bone marrow failure (inherited or acquires) [ 1 ]. The most common etiology of AA is considered to be idiopathic, responsible for 65% of cases. Seronegative hepatitis accounts for about 10% of cases and tends to develop three months after the episode of acute hepatitis [ 6 ]. Telomerase abnormalities are found in approximately 5% of late-onset AA [ 7 ]. Among hereditary causes, Fanconi anemia is the most common, which presents in the first 10 years of life with pancytopenia, hypoplasia, and bone abnormalities [ 8 ].

The clinical manifestation of AA is usually some non-specific finding due to pancytopenia, such as fatigue, dyspnea on exertion due to anemia, mucosal bleeding like petechiae, heavy menses, gingival bleeding due to thrombocytopenia, or fever with neutropenia [ 9 ]. A bone marrow examination with a finding of aplastic or hypoplastic marrow is required to establish a diagnosis. In addition, cytogenetic studies, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or next-generation sequencing (NGS), help make a diagnosis and rule out other hematologic abnormalities responsible for pancytopenia [ 9 ]. Peripheral blood-flow cytometry could be helpful in order to exclude paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) [ 10 ].

Management of AA in patients without reversible causes depends on the age of the patient and disease severity. For young and healthy individuals under 50 years old, an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) should be performed before initiation of immunosuppressive therapy (IST). Those who are older than 50 years old or younger individuals who cannot have HCT should start on full-dose IST, including eltrombopag, which is a thrombopoietin agonist, anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) that eliminates antigen-reactive T-cells, cyclosporin A inhibiting interleukin-II (IL-2), and prednisone that leads to the destruction of immature T-lymphocytes [ 9 ]. Supportive treatment with transfusions of leukoreduced RBC for hemoglobin (Hgb) less than 7 mg/dL or platelets less than 10,000/microliters and infection treatment or prophylaxis is also indicated for patients with AA [ 1 ].

Here, we present a case of a 35-year-old male who presented to the emergency room with profuse bleeding after deep dental cleaning and was found to have pancytopenia on his laboratory panel.

Case presentation

A 35-year-old male presented to the emergency department (ED) of our hospital for persistent bleeding of his gums. He had been having episodes of minimal gum bleeding for a week that he attributed to an infection and had gone to a dentist on the day of admission for dental cleaning. He started having profuse bleeding after the dental procedure, which did not resolve with the application of pressure and was advised to go to the ED.

At the time of admission, he was in mild distress and concerned about the bleeding. The patient did not have any dizziness, headache, palpitations, or bleeding anywhere else. He denied similar episodes in the past or a family history of bleeding. The patient denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use and was not on any anticoagulants/anti-platelets. The patient migrated from Mexico 20 years ago and worked in construction. He denied any sick contact or recent travel. On examination, his vital signs were stable, but he was in mild distress. He was having profuse bleeding in his bilateral lower gums, both the buccal and lingual side, and in the buccal side of his upper gums. The rest of the examination was unremarkable.

Initial laboratory results were significant for pancytopenia (Table 1 ). The chemistry panel was significant for elevated blood urea nitrogen and mild hypokalemia (potassium = 3.4 mEq/L). The liver function test, renal function test, coagulation panel, and other electrolyte results were normal. The peripheral blood smear test showed normal WBC and platelet morphology, decreased platelet number, abnormal RBC morphology, marked hypochromasia, and slight schistocytes.

Table 1. CBC results.

g/dL: grams per deciliter; mm 3 : cubic meter; µm 3 : cubic micrometer; pg/cell: picogram per cell

CBC: complete blood count; WBCs: white blood cells; RBCs: red blood cells; Hbg: hemoglobin; Hct: hematocrit; MCV: mean cell volume; MCH: mean cell hemoglobin; PT: prothrombin time; INR: international normalized ratio; PTT: partial thromboplastin time

Within two hours, the patient became hypotensive and developed hemorrhagic shock, and was admitted to the intensive care unit. The patient’s mouth was packed, and he received multiple transfusions of packed RBC and platelets. Further test results (Table 2 ) were negative for any infections. However, he was positive for parvovirus and cytomegalovirus IgG antibodies, which were likely from a previously cleared infection. The reticulocyte count was 0.9 after correction for hematocrit, and haptoglobin and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were both within normal limits, pointing toward the hypoproliferation of the bone marrow rather than hemolysis.

Table 2. Viral serology profiles.

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HBVs Ag: hepatitis B surface antigen; HBVc IgM Ab: IgM antibody against hepatitis B core antigen; HBV cIgM: hepatitis B virus cytoplasmic IgM; HCV IgG Ab: IgG antibody against hepatitis C; HAV IgM: IgM antibody against hepatitis A; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; CMV IgG Ab; IgG antibody against cytomegalovirus; CMV IgM Ab: IgM antibody against cytomegalovirus; parvovirus B19 IgG Ab: parvovirus B19 IgG antibody; parvovirus B19 IgM Ab: parvovirus B19 IgM antibody

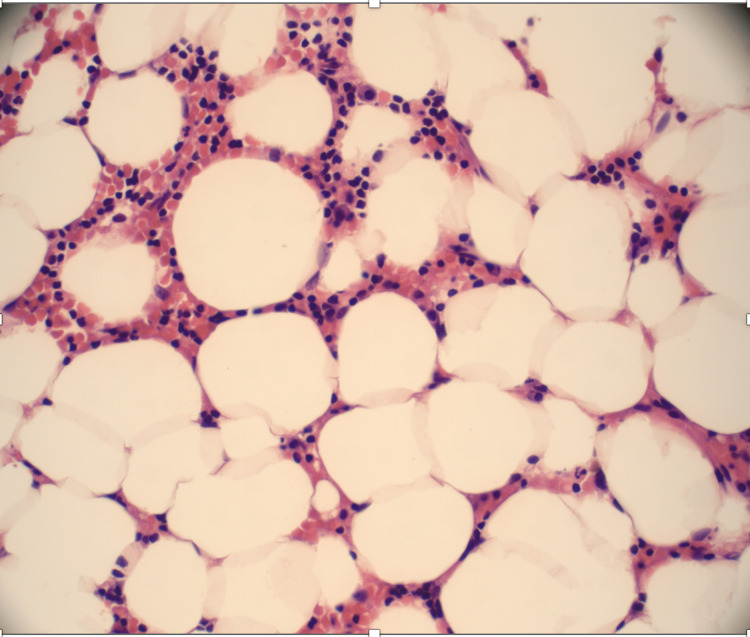

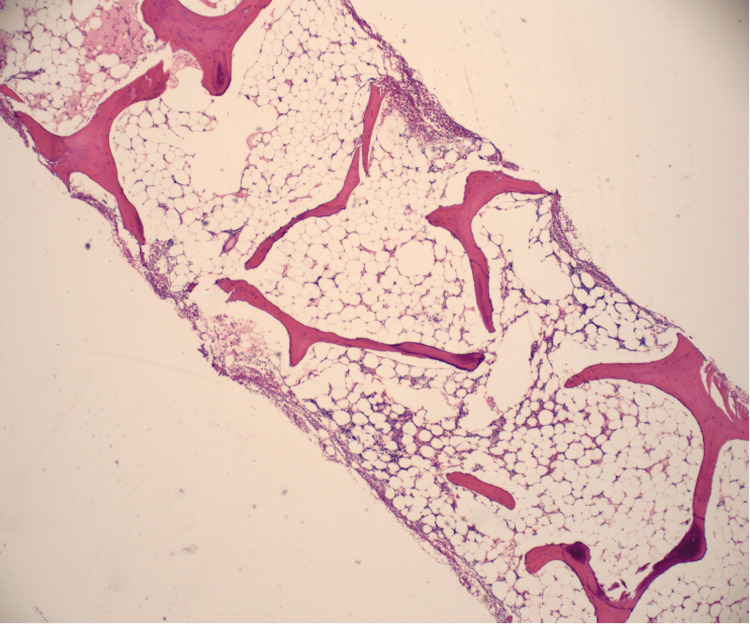

The bone marrow biopsy showed a hypocellular bone marrow with 5-10% cellularity consistent with AA (Figure 1 , Figure 2 ).

Figure 1. Bone marrow aspiration is aparticulate and markedly hypocellular, 5-10% cellularity consistent with aplastic anemia. No abnormal cells were seen.

Figure 2. Bone marrow trephine biopsy shows a hypocellular marrow, which was replaced mainly with nonhematopoietic tissues, such as fat.

PNH flow cytometry with fluorescein-labeled proaerolysin (FLAER), which is a high-sensitivity assay that assesses the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked CD59 on erythrocytes, was abnormal with elevated PNH monocytes (2.001%) and polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMNs) (0.381%). No circulating blasts and megakaryocytes were seen. The overall AA is associated with PNH.

The patient was not accepted for the Allogenic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSTC) Center due to the lack of insurance. The patient was started on triple immune suppression therapy: ATG, cyclosporine (CsA), and prednisone. The patient was started on equine ATG 40 mg/kg/day IV for four consecutive days in combination with CsA 10 mg/kg every 12 hours and prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/day). In addition, he received eltrombopag 150 mg per oral (PO) once per day, an oral thrombopoietin-receptor agonist, and diphenhydramine 25 mg to prevent serum sickness from ATG. The patient continued to be on neutropenic precautions and close monitoring of all cell line levels, with goals of Hgb 7 g/dL and platelet count 10,000/mm 3 .

The patient was discharged home to continue outpatient chemotherapy. On the last follow-up at the outpatient clinic, three months after admission, recovery of all the three cell lines was noted (Table 3 ).

Table 3. CBC results.

CBC: complete blood count; WBCs; white blood cells; RBCs: red blood cells; Hbg: hemoglobin; Hct: hematocrit; MCV: mean cell volume; MCH: mean cell hemoglobin

The 35-year-old patient with no significant past medical history presented to the hospital with oropharyngeal bleeding. The severity of his thrombocytopenia expanded and the bleeding worsened upon his presentation to the hospital. His decreased WBC count and neutropenia put him at a high risk of infection. Low Hgb and below-normal reticulocytes showed that his RBC production was profoundly impaired. The bone marrow biopsy ruled out other differential diagnoses, but the cause of AA development was still questionable. In addition, the patient was found to have PNH, which could be associated with AA in 40% of patients. However, there are contradictory data in the literature about the impact of PNH clones on patients with AA undergoing immunosuppressive treatment.

AA can be associated with a broad spectrum of pathologies that could lead to the loss of progenitor cells and pancytopenia. There are three main mechanisms of its development: disrupting extrinsic factors, expression of familial genetic mutations, or damage by an autoimmune attack on hematologic cells [ 1 ]. The extrinsic mechanisms of AA are usually apparent and include exposure to therapeutic radiation, benzene, chemotherapy [ 11 ], several medications, or pesticides, such as organophosphates [ 7 ]. Nevertheless, this patient did not take any medications or have no known history of radiation or chemotherapy.

A genetic abnormality that is mainly associated with AA is Fanconi anemia, a condition attributed to DNA repair abnormalities. This syndrome is usually manifested in patients during the first or second decade with other congenital defects, such as thumb or facial abnormalities and short stature [ 12 ]. Dyskeratosis congenita is another common mechanism, a condition caused by mutations in genes responsible for the repair of telomeres. Patients can present with skin pigmentations, oral leukoplakia, and dystrophic nails [ 13 ]. Congenital abnormality was highly unlikely in this patient; he did not have any family history of such conditions, nor had a clinical manifestation.

Another common cause of AA can be seronegative hepatitis, which can develop in up to 10% of cases approximately three months before the manifestation of AA [ 14 ]. It usually occurs in the younger population. However, this patient did not have any risk factors or any history related to the development of hepatitis. Other viruses that could predispose to AA include HIV or parvovirus B19 [ 15 ]. IgG usually develops two weeks after infection and persists for life, with an increase in level post-re-exposure. Transient aplastic crisis (TAC) is characterized by the abrupt onset of anemia with absent or low-level reticulocytes and can be associated with B19 in patients with hematologic abnormalities. TAC and B19 can also lead to other cytopenias in other blood lineages [ 16 ]. TAC could be a potential explanation for the patient’s symptoms as his blood tests revealed elevated IgG levels to B19. This finding can reflect only previous infections and has no association with AA in this patient. Nevertheless, regardless of the trigger, the patient’s presentation and the severity of his AA were associated with a high chance of death without urgent management.

Management of AA depends on the severity of the condition, the age of a person, access to the treatment or availability of a matched stem-cell donor, and the presence of other comorbidities that decrease the chance of getting a cell transplant [ 17 ]. The patient’s laboratory values met the criteria for severe AA, which are defined by bone marrow hypocellularity of less than 30% and involvement of at least two out of the three criteria: absolute reticulocyte count less than <60 ×109/L, absolute neutrophil count less than 0.5×109/L, or platelet count less than 20 ×109/L. Younger age (less than 40) and the presence of a matched sibling donor favor the use of the allogeneic HSCT. Usually, older patients (>40 years) and those who do not have access to HSCT are treated with IST, which includes a combination of ATG and CsA with response rates up to 80% and survival rates the same as those after HSCT [ 18 ]. However, rates of relapse and evolution to myelodysplastic syndromes are higher with IST treatment [ 19 ]. Bacigalupo et al. showed an overall survival rate of 87% and a response rate of 77% in 100 patients treated with CsA, ATG, prednisone, and filgrastim [ 20 ]. Nevertheless, the patient did not have access to the treatment with an allogeneic stem cell transplant. He was commenced on full IST with eltrombopag, ATG, and CsA with prednisone and diphenhydramine to prevent serum sickness from ATG.

Some studies have revealed factors that predict a better response to IST, such as younger age, high absolute reticulocyte and lymphocyte count, and mutations in the PIGA, BCOR, or BCORL1 genes [ 21 ]. Mutations in the PIGA gene lead to the lack of the GPI-anchored proteins, CD59, and decay-accelerating factor (DAF or CD55) in patients with PNH. Deficiency of these GPI-anchoring proteins in WBCs and RBCs leads to the development of the so-called escape clones of PNH in AA [ 22 ].

The explanation of this immune escape mechanism is proposed to be associated with cytotoxic T cells that target normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), and PNH-positive HSCs are protected from this immune attack. These T cells’ target can most likely be GPI anchors in patients with AA [ 23 , 24 ].

PNH escape clones can be found in more than 50% of patients with AA at the time of diagnosis, as in this patient. According to the AA guidelines of the British Society for Standards in Haematology, all patients with AA should be screened for PNH clones [ 17 ]. The impact of PNH clones on the treatment outcome of patients treated with IST has been discussed in the recent meta-analysis that showed a better response rate in the group diagnosed with PNH [ 25 ].

Apart from IST, patients with AA usually require supportive care that includes prophylaxis and treatment of infections, transfusions of leukoreduced packed RBC if the level of Hgb is less than 7 mg/dL, or platelets if their level drops below 10 x 109/L, or less than 50 x 109/L with active bleeding [ 1 ]. The patient presented with a platelet count of 4 x 109/L; therefore, he received multiple platelet transfusions before being discharged home.

The patient gradually improved on IST and was eventually discharged home to continue outpatient chemotherapy. On the last follow-up at the outpatient clinic, three months after admission, recovery of all the three cell lines was noted.

Conclusions

In this case report, we described a case of a healthy young man with no medical history who presented to the hospital with persistent bleeding from his gums and was found to have AA. The patient’s laboratory values met the criteria for severe AA, and he was also found to have PNH that could be associated with AA in 40% of patients. Patients with age less than 40 and the presence of a matched sibling donor favor the use of HSCT. Our patient did not have access to the bone marrow transplant. Therefore, he was commenced on full IST with ATG, prednisone, and CsA. In addition to IST, the patient was also receiving eltrombopag. The patient with severe AA responded excellently to the therapy, recovering all the three cell lines after three months of management. Therefore, young age, no significant past medical history, and concomitant diagnosis with PNH can be the main factors leading to a better response rate to IST in patients diagnosed with severe AA.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

- 1. Aplastic anaemia: current concepts in diagnosis and management. Furlong E, Carter T. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56:1023–1028. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14996. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Incidence and outcome of acquired aplastic anemia: real-world data from patients diagnosed in Sweden from 2000-2011. Vaht K, Göransson M, Carlson K, et al. Haematologica. 2017;102:1683–1690. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.169862. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Incidence of aplastic anemia in Bangkok. The Aplastic Anemia Study Group. Issaragrisil S, Sriratanasatavorn C, Piankijagum A, et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2029577/ Blood. 1991;77:2166–2168. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Cyclosporin A response and dependence in children with acquired aplastic anaemia: a multicentre retrospective study with long-term observation follow-up. Saracco P, Quarello P, Iori AP, et al. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06903.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Epidemiology of aplastic anemia: a prospective multicenter study. Montané E, Ibáñez L, Vidal X, Ballarín E, Puig R, García N, Laporte JR. Haematologica. 2008;93:518–523. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12020. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Hepatitis-associated aplastic anaemia: epidemiology and treatment results obtained in Europe. A report of The EBMT aplastic anaemia working party. Locasciulli A, Bacigalupo A, Bruno B, et al. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:890–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08194.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Aplastic anemia: etiology, molecular pathogenesis, and emerging concepts. Shallis RM, Ahmad R, Zeidan AM. Eur J Haematol. 2018;101:711–720. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13153. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Genetic basis of Fanconi anemia. Bagby GC Jr. Curr Opin Hematol. 2003;10:68–76. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200301000-00011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Aplastic anaemia. Brodsky RA, Jones RJ. Lancet. 2005;365:1647–1656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66515-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Improved detection and characterization of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria using fluorescent aerolysin. Brodsky RA, Mukhina GL, Li S, Nelson KL, Chiurazzi PL, Buckley JT, Borowitz MJ. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:459–466. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/114.3.459. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Aplastic anemia. Young NS. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1643–1656. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1413485. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Fanconi anemia. Soulier J. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:492–497. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.492. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Dyskeratosis congenita. Dokal I. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:480–486. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.480. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia. Brown KE, Tisdale J, Barrett AJ, Dunbar CE, Young NS. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1059–1064. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361504. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Concise review: anemia caused by viruses. Morinet F, Leruez-Ville M, Pillet S, Fichelson S. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1656–1660. doi: 10.1002/stem.725. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Parvoviruses and bone marrow failure. Brown KE, Young NS. Stem Cells. 1996;14:151–163. doi: 10.1002/stem.140151. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anaemia. Killick SB, Bown N, Cavenagh J, et al. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:187–207. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13853. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Antilymphocyte globulin, cyclosporin, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with acquired severe aplastic anemia (SAA): a pilot study of the EBMT SAA Working Party. Bacigalupo A, Broccia G, Corda G, et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7532040/ Blood. 1995;85:1348–1353. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporine for severe aplastic anemia: association between hematologic response and long-term outcome. Rosenfeld S, Follmann D, Nunez O, Young NS. JAMA. 2003;289:1130–1135. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1130. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Antilymphocyte globulin, cyclosporine, prednisolone, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for severe aplastic anemia: an update of the GITMO/EBMT study on 100 patients. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Working Party on Severe Aplastic Anemia and the Gruppo Italiano Trapianti di Midolio Osseo (GITMO) Bacigalupo A, Bruno B, Saracco P, et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10706857/ Blood. 2000;95:1931–1934. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Minor population of CD55-CD59- blood cells predicts response to immunosuppressive therapy and prognosis in patients with aplastic anemia. Sugimori C, Chuhjo T, Feng X, et al. Blood. 2006;107:1308–1314. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2485. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. A closer look at paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Rachidi S, Musallam KM, Taher AT. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.04.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in aplastic anemia. Yoshizato T, Dumitriu B, Hosokawa K, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:35–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414799. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Novel therapeutic choices in immune aplastic anemia. Scheinberg P. F1000Res. 2020;9 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22214.1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. PNH clones for aplastic anemia with immunosuppressive therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tu J, Pan H, Li R, et al. Acta Haematol. 2021;144:34–43. doi: 10.1159/000506387. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (589.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

COMMENTS

Address correspondence to Alexandra P. Wolanskyj, MD, Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Rochester, MN 55905 ([email protected]. A 39-year-old woman was referred to our institution for evaluation of anemia. She was known to have multiple comorbidities and had a baseline hemoglobin concentration of approximately 10. ...

Mother alive at 50 years old. Diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia at 24 years old during pregnancy with patient - on daily supplement. Otherwise healthy. Father alive at 52 years old. Diagnosis of hypertension - controlled with diet and exercise. Otherwise healthy.

Background Anemia is a serious global health problem that affects individuals of all ages but particularly women of reproductive age. Iron deficiency anemia is one of the most common causes of anemia seen in women, with menstruation being one of the leading causes. Excessive, prolonged, and irregular uterine bleeding, also known as menometrorrhagia, can lead to severe anemia. In this case ...

The following case study focuses on a 12-year-old boy from Guyana who is referred by his family physician for jaundice, normocytic anemia, and recurrent acute bone pains. Test your knowledge by reading the background information below and making the proper selections. Complete blood count (CBC) reveals a hemoglobin of 6.5 g/dL, MCV 82.3 fL ...

Anemia-2: Overview and Select Cases. Marc Zumberg Associate Professor Division of Hematology/Oncology. Complete blood count with indices. MCV-indication of RBC size. RDW-indication of RBC size variation. Examination of the peripheral blood smear. Reticulocyte count-measurement of newly produced young rbc's. Stool guiac.

As our case illustrates, distinguishing microcytic anemia due to chronic disease from IDA may be difficult when the history and physical examination findings are not helpful and the results of serum iron studies are atypical for either disease. When iron studies are not helpful, further tests are warranted to exclude IDA or inflammatory disease.

We report the case of a 76-year-old woman with clinical symptoms and laboratory con fi rmation of se-. vere anemia with level of hemoglobin 24 g/l, and hematocrit 0.08. Anemia was a sign of ...

The goal of the case study is to clarify specific and timely teaching points in the field of hematology. The following case study focuses on a 32-year-old woman, with no significant past medical history, who presents to the emergency department with several days of worsening confusion. The complete blood count shows a hemoglobin concentration ...

In this case report, we described a case of a healthy young man with no medical history who presented to the hospital with persistent bleeding from his gums and was found to have AA. ... and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with acquired severe aplastic anemia (SAA): a pilot study of the EBMT SAA Working Party. Bacigalupo A ...

Dr. Nicole de Paz (Pediatrics): A 20-month-old boy was admitted to the pediatric inten-sive care unit of this hospital because of severe anemia. The patient was well until 5 days before admission ...