Inner Strength For Life – The 12 Master Virtues

Our journey of growth in life can be described as a journey of developing both insights and also virtues (qualities of mind and heart). This article maps out what are the main qualities to develop, and what particular strengths or gifts are gained from each of them.

Developing virtues is not about being better than others, but about developing the potential of our own heart and mind. The philosophers of ancient Greece , Buddha , the Yogis, and the Positive Psychology movement all value the cultivation of certain personal qualities. In this essay I attempt to systematize these core strengths into 12 “buckets” or “power virtues”, as many of them share common features.

Each of these virtues, rather than being an inborn personal trait, are habits and states of mind that can be consciously cultivated using a systematic approach.

There are many books written about each of these virtues. In this post I can only cover a brief introduction of each, and suggest some further reading. Finally, I have separated them into virtues of mind and heart only for the sake of exposition – in truth there is great overlap between both.

Let us begin by talking about the need to develop virtues holistically.

Jump to section

What is a Virtue

Balanced self-development, tranquility, virtues list, parting thoughts.

A virtue is a positive character trait that is consider a foundation for living well, and a key ingredient to greatness.

For some, the word “virtue” may have a bit of a Victorian puritanism associated with it. This is not my understanding of it, nor is this the spirit of this article.

Rather, a virtue is a personal asset , a shield to protect us from difficulty, trouble, and suffering. Each virtue is a special sort of “power” that enables us to experience a level of well-being that we wouldn’t be able to access otherwise. Indeed, “virtue”comes from the latin virtus (force, worth, power).

Let’s take the virtue of equanimity as an example.

Developing equanimity protects us from suffering through the ups and downs of life, and saves us from the pain of being criticized, wronged, or left behind. It unlocks a new level of well-being: the emotional stability of knowing we will always be ok.

The same is true for every virtue discussed in this essay.

We all have certain personal qualities more naturally developed than the others. And our tendency is often to double-down on the virtues that we already have, rather than developing complementary virtues . For instance, people who are good at self-discipline may focus on getting even better at that, and overlook the need to develop the opposing virtue of flexibility.

There is no doubt that we need to play our strengths . But when we focus solely on our strengths and use them to overcompensate our weaknesses, the result is often not good. We can become victims of our own blessings.

Let’s take the case of a person whose natural strength is compassion and kindness. In certain relationships, this might be abused by other people (directly or indirectly). Dealing with this situation by becoming kinder would not be wise. Instead, the opposing virtue of self-assertiveness (the courage of setting boundaries), is to be exercised.

Here are some other examples of virtues that are incomplete (and potentially harmful) in isolation:

- Tranquility without joy and energy is stale;

- Detachment and equanimity without love can be cold;

- Trust without wisdom can be blind;

- Morality without humility can be self-righteous;

- Love without wisdom can cause harm to oneself;

- Focus and courage without love and wisdom is just blind power.

It took me years to get to this precious insight – and I’ll probably need a lifetime to learn how to implement it. 😉

Funnily enough, afterwards I discovered that this was already a concept praised by the Stoics. In Stoicism, it is called anacoluthia , the mutual entailment of virtues.

The point is: we need to focus on our strengths, but we also need to pay attention to the virtues we lack the most. Any development in these areas, however small, has the potential to be life-changing. I go deeper into this topic here .

Have a look at your current strengths. What complementary virtues might you be overlooking?

Best Virtues of Mind

“Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage.” – Anais Nin

Related qualities: boldness, fearlessness, decisiveness, leadership, assertiveness, confidence, magnanimity.

Courage says: “The consequences of this action might be painful for me, but it’s the right thing to do. I’ll do it.”

Courage is the ability to hold on to the feeling “I need to do this”, ignore the fear mongering thoughts, and take action. For a few, it is the absence of fear; for most, it’s the willingness to act despite fear.

Examples: It takes courage to expose yourself, to try something new, to change directions, to take a risk, to let go of an attachment, to say “I was wrong”, to have a difficult conversation, to trust yourself. Its manifestations are many, both in small and big things in life.

Without courage we feel powerless. Because we know what we want to do, or what we need to do, but we lack the boldness to take action. We default to the easy way out, the path of least resistance. It might feel comfortable now, but in the long term it doesn’t make us happy.

Recommended book: Daring Greatly (Brené Brown)

“The more tranquil a man becomes, the greater his success, his influence, his power for good. Calmness of mind is one of the beautiful jewels of wisdom.” – James Allen

Related qualities: serenity, calmness, non-reactivity, gentleness, peace, acceptance.

Tranquility says: “There is no need to stress. All is well.”

Tranquility involves keeping your mind and heart calm, like the ocean’s depth. You take your time to perceive what’s going on and act purposefully, without agitation, without hurry, and without overreacting. On a deeper level, it means to diminish rumination, worries, and useless thinking.

Examples: Taking a deep breath before answering an email or phone call, or before responding to the hurtful behavior of someone else. Being ok with the fact that things are often not going to go as we expect. Not brooding about the past or worrying too much about the future. Shunning busyness in favor of a more purposeful living. Not living in fight-or-flight mode.

Without tranquility we expend more energy than what’s really needed. We experience a constant feeling of stress, anxiety, or agitation in the back of our minds. And sometimes we may be fooling ourselves thinking we are being “active” or “productive”.

Recommended book: The Path to Tranquility (Dalai Lama)

“Success is going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm.” -Winston Churchill

Related qualities: energy, enthusiasm, passion, vitality, zeal, perseverance, willpower, determination, discipline, self-control, resolution, mindfulness, steadfastness, tenacity, grit.

Diligence says: “I am committed to this work / habit / path. I will continue it no matter what , even in the face of challenges, discouragement, and tiredness.”

Some may say that it is the most essential virtue for success in any field – career, art, sports or business. It is about making a decision once, in something that is good for you, and then keeping it up despite adversities and mood fluctuations.

Examples: Deciding to stop smoking and never again lighting acigarette. Deciding that I will meditate every day and keeping that up, like a perfect habit chain. Showing up to train / study / work in your passion project day after day, regardless of how you feel. Always getting up as soon as you fall. Having an unbreakable, almost stubborn, determination. Treating challenges like energy bars.

Without diligence we can’t accomplish anything meaningful. We can’t properly take care of our health, finances, mind, or relationships. We give up on everything too soon. We can’t create good habits, break bad habits, or manifest the things we want in our lives. We are a victim of circumstances, social/familial conditioning, and genetics.

Recommended books: The Willpower Instinct (Kelly McGonigal), Grit (Angela Duckworth), Power of Habit (Charles Duhhig)

“The powers of the mind are like the rays of the sun – when they are concentrated they illumine.” – Swami Vivekananda

Related qualities: concentration, one-pointedness, depth, contemplation, essentialism, meditation, orderliness.

Focus says: “I will ignore distractions, ignore the thousand different trivial things, and put all my energy in the most important thing. I will keep going deeper into what really matters. I can tame my own mind.”

Focus, the ability to control your attention, is the core skill of meditation . It involves bringing your mind, moment after moment, to dwell where you want it to dwell, rather than being pulled by the gravity of all the noise going on inside and outside of you.

Examples: Bringing your mind again and again to your breathing or mantra , during meditation. Cutting down on social media, TV and gossip. Learning to say “no” to 90% of good opportunities, so you can say yes to the 10% of great opportunities. Staying on your chosen path and not chasing the next shiny thing.

Without focus our energy is dissipated and our progress in any field is limited (like moving one mile in ten directions, rather than ten miles in a single direction). Focus, together with motivation and diligence, is a type of fire, and as such it needs to be balanced with more water-like virtues.

Recommended book: Essentialism (Greg McKeown)

“Happy is the man who can endure the highest and lowest fortune. He who has endured such vicissitudes with equanimity has deprived misfortune of its power.” – Seneca the Younger

Related qualities: balance, temperance, patience, forbearance, tolerance, acceptance, resilience, fortitude.

Equanimity says: “In highs and lows, victory and defeat, pleasure and pain, gain or loss – I keep evenness of temper. Nothing can mess me up.”

It is the ability to accept the present moment without emotional reaction, without agitation. It’s being unfuckwithable , imperturbable.

Examples: Not going into despair when we miss an opportunity, or lose some money. Not feeling elated when praised, or discouraged when criticized. Not taking offense from other people. Not indulging in emotional reactions to gain or loss, whatever shape they take. Being modest in success, and gracious in defeat.

Without equanimity , life is an emotional roller-coaster. We are attached to the highs, which brings pain because they are short-lived. And we are uncomfortable (perhaps even fearful) with the lows – which also brings pain, because they can’t be fully avoided.

Recommended book: Letters from a Stoic (Seneca), Dhammapada (Buddha)

“A great man is always willing to be little.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

Related qualities: modesty, humbleness, discretion, egolessness, lack of conceit, simplicity, prudence, respect.

Humility says: “There are many things that I don’t know. Every person I meet is my teacher in something.”

Humility is letting go of the desire to feel superior to other people, either by means of wealth, fame, intelligence, beauty, titles, or influence. It’s about not comparing yourself with others, to be either superior or inferior. In the words of C.S. Lewis, True humility is not about thinking less of yourself; it is thinking of yourself less . In the deepest sense, humility is about transcending the ego.

This virtue is especially needed for overachievers and “successful people”.

Examples: Accepting your own mistakes. Learning to see virtue and good in others. Not dwelling on vanity and feelings of inflated self-importance. Being genuinely happy with other people’s successes. Accepting the uncertainty of life, and how small we are.

Without humility , we live stuck in an ego trap which prevents us from growing beyond the confines of our self-interests, and also poisons our relationships.

Recommended books: Ego is the Enemy (Ryan Holiday), Humility: An Unlikely Biography of America’s Greatest Virtue

“Always do what is right. It will gratify half of mankind and astound the other.” – Mark Twain

Related qualities: character, justice, honor, truthfulness, sincerity, honesty, responsibility, reliability, morality, righteousness, ethics, idealism, loyalty, dignity.

Integrity says: “I will do what is right, according to my conscience, even if nobody is looking. I will choose thoughts and words based on my values, not on personal gains. I will be radically honest and authentic, with myself and others.”

Like many virtues, integrity is about choosing what is best , rather than what is easy . It invites us to resist instant gratification in favor of a higher type of satisfaction – that of doing the right thing. It’s not about being moralistic, but about being congruent to our own conscience and values, in all our actions.

Examples: Refusing to distort the truth in order to gain personal benefits. Sticking to our words. Acting as though all our real intentions were publicly visible by others. Letting go of the “but I can get away with it” thinking. Not promising what you know you cannot fulfill.

Without integrity , we are not perceived as trustable or genuine. We make decisions that favor a short term gain but are likely to bring disastrous consequences in the long run.

Recommended books: Lying (Sam Harris), Yoga Morality (Georg Feuerstein)

“Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom” – Aristotle

Related qualities: intelligence, discernment, insight, understanding, knowledge, transcendence, perspective, discrimination, contemplation, investigation, clarity, vision.

Wisdom says: “Let me contemplate deeply on this. Let me understand it from the inside out. Let me know myself.”

Unlike the other virtues listed so far, wisdom it is not something that you can directly practice. Rather, it is the result of contemplation, introspection, study, and experience. It unveils the other virtues, informs them, and makes their practice easier. It points out the truth behind the surface, and the connection among things.

Without wisdom , we don’t really know what we are doing. Life is small, often confusing, and there might be a sense of purposelessness.

Recommended books: This depends on your taste for traditional and philosophy ( here is my list). Or you can also join my Practical Wisdom Newsletter .

Best Virtues of Heart

“You have to trust in something – your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever.” – Steve Jobs

Related qualities: optimism, faith, openness, devotion, hope.

Trust says: “There is something larger than me. Life flows better when I trust resources larger than my own, and when I see purpose in random events.”

Trust is not a whimsical expectation that things will happen according to your preference; but rather a faith that things will happen in favor of your greater good. As Tony Robbins says, it is the attitude that life is happening for you , not to you .

Examples: Not dwelling on negative interpretations of what has happened in your life. Trusting that there is something good to be learned or gained from any situation. Having the feeling that if you keep true to your path, things will eventually work out ok.

Without trust , life can feel lonely, scary, or unfair. You are on your own, in the midst of random events, in a cold and careless universe.

Recommended book: Radical Acceptance (Tara Brach)

“Remain cheerful, for nothing destructivecan piece through the solid wall of cheerfulness.” – Sri Chinmoy

Related qualities: contentment, cheerfulness, satisfaction, gratitude, humor, appreciation.

Joy says: “I am cheerful, content, happy, and grateful. There is always something good in anything that happens. I feel well in my own skin, without depending on anything else.”

The disposition for joy is something that can be consciously cultivated. It is often the result of good vitality in the body, peace of mind, and an attitude of appreciation. It is also a natural consequence of a deep meditation practice , and the letting go of clinging.

Examples: Feeling good as a result of the positive states you have cultivated in your body (health), mind (peace), and heart (gratitude).

Without joy we are unhappy, cranky, gloomy, pessimistic, bored, neurotic.

Recommended books: The How of Happiness (Sonja Lyubomirsky), The Book of Joy (Dalai Lama et ali)

“The tighter you squeeze, the less you have.” – Zen Saying

Related qualities: dispassion, non-attachment, forgiveness, letting go, moderation, flexibility, frugality.

Detachment says: “I interact with things, I experience things, but I do not own them. Everything passes. I can let them be, and let them go.”

Learning how to let go is one of the most important things in overcoming suffering. It doesn’t mean that we live life less intensely; rather, we do what we are called to do with zest, and then we step back and watch what happens, without anxiety. It doesn’t mean we don’t love, play, work, or seek with intensity; but rather that we are detached from the results, knowing that we have full control only over the effort we make.

At the deepest level, detachment is a disillusionment with external desires and goals, and there is the realization that the only reliable source of happiness is internal. It also involves not holding onto any particular state.

Examples: Not being anxious about what the future brings. Letting go when things need to go. “Opening the hand” of your mind and allowing things to flow as they will. Having the feeling of not needing anything .

Without detachment, we suffer loss again and again. We can be manipulated. The mind is an open field for worries, fear, and insecurity.

Recommended books: Letting Go (David R. Hawkins), Everything Arises, Everything Falls Away (Ajahn Chah)

Check also my online course on the topic: Letting Go, Letting Be .

“The more you lose yourself in something bigger than yourself, the more energy you will have.” – Norman Vincent Peale

Related qualities: love, compassion, friendliness, service, generosity, sacrifice, selflessness, cooperation, nonviolence, consideration, tact, sensitivity.

Kindness says: “I feel others as myself, and take pleasure in doing good for them, in giving and serving. I wish everyone well. The well-being of others is my well-being.”

Kindness and related virtues (love, compassion, consideration) is the core “social virtue”. It invites us to expand our sense of well-being to include others as well. It gives us the ability to put ourselves in another person’s shoes, and feel what they feel as if it is happening to us, and if appropriate do something about it. The result is the experience of the “helper’s high”, a mix of dopamine and oxytocin.

At it’s most basic level, this virtue tell us to do unto others as you would have them do unto you . At the deepest level, it says “We are all one”.

Examples: Offering a word of encouragement or advice. Listening without judgment. Helping someone in need, directly or indirectly. Teaching. Assuming the best in others. Volunteering. Doing something for someone who can never repay you.

Without kindness , we cannot build any true human connection, and we fail to experience a happiness that is larger than ourself.

Recommended books: The Power of Kindness (Pierro Ferrucci), Awakening Loving-Kindness (Pema Chodron)

Here is the full list of virtues. The ones that are very similar are grouped together.

- Acceptance. Letting go.

- Contentment. Joyfulness.

- Confidence. Boldness. Courage. Assertiveness.

- Forgiveness. Magnanimity. Clemency.

- Honesty. Authenticity. Truthfulness. Sincerity. Integrity.

- Kindness. Generosity. Compassion. Empathy. Friendliness.

- Loyalty. Trustworthiness. Reliability.

- Perseverance. Determination. Purposefulness. Tenacity.

- Willpower. Self-control. Fortitude. Self-discipline.

- Loyalty. Commitment. Responsibility.

- Caringness. Consideration. Support. Service.

- Cooperation. Unity.

- Humility. Simplicity.

- Creativity. Imagination.

- Detachment.

- Wisdom. Thoughtfulness. Insight.

- Dignity. Honor. Respect.

- Energy. Motivation. Zest. Enthusiasm. Passion.

- Resilience. Grit. Tolerance. Patience.

- Excellence.

- Orderliness. Purity. Clarity.

- Prudence. Awareness. Tactfulness. Preparedness.

- Temperance. Balance. Moderation.

- Justice. Fairness.

- Trust. Faith. Hope. Optimism.

- Calmnes. Serenity. Centeredness. Peace.

- Grace. Elegance. Gentleness.

- Flexibility. Adaptability.

Developing these virtues is a life-long process. We’ll probably never be perfect at them. But the more we cultivate them, the better our life becomes. And, chances are, simply reading about these virtues has already enlivened them in you.

One simple way of cultivating these virtues is to focus on a single virtue each week (or month), and look daily for opportunities to put that chosen quality into practice. Keep asking yourself throughout the day, “What does it mean to be [virtue]?”

However, if you want to develop them more systematically, with practical exercises and support, consider joining my Intermediate Meditation Course . In this online program, besides learning 10 different types of meditation, you will find lessons focused on developing 10 different character strengths/virtues.

Another option is to work in person with me as your coach .

Every step taken on developing these virtues is valuable. By developing them we grow as a person, expand our awareness, and have better tools to live a happy and meaningful life.

Spread Meditation:

- ← Previous post

- Next Post →

Related Posts

Shifting from anxious living to fearless living, optimism, gratitude, and contentment as a solution to anxiety 🙏🏻🙃😌, anxiety feeds on itself… but so does courage 😉💪🏻.

Become Calm, Centered, Focused.

Make the world a better place, one mind at a time.

Copyrights @ 2019 All Rights Reserved

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics is currently one of three major approaches in normative ethics. It may, initially, be identified as the one that emphasizes the virtues, or moral character, in contrast to the approach that emphasizes duties or rules (deontology) or that emphasizes the consequences of actions (consequentialism). Suppose it is obvious that someone in need should be helped. A utilitarian will point to the fact that the consequences of doing so will maximize well-being, a deontologist to the fact that, in doing so the agent will be acting in accordance with a moral rule such as “Do unto others as you would be done by” and a virtue ethicist to the fact that helping the person would be charitable or benevolent.

This is not to say that only virtue ethicists attend to virtues, any more than it is to say that only consequentialists attend to consequences or only deontologists to rules. Each of the above-mentioned approaches can make room for virtues, consequences, and rules. Indeed, any plausible normative ethical theory will have something to say about all three. What distinguishes virtue ethics from consequentialism or deontology is the centrality of virtue within the theory (Watson 1990; Kawall 2009). Whereas consequentialists will define virtues as traits that yield good consequences and deontologists will define them as traits possessed by those who reliably fulfil their duties, virtue ethicists will resist the attempt to define virtues in terms of some other concept that is taken to be more fundamental. Rather, virtues and vices will be foundational for virtue ethical theories and other normative notions will be grounded in them.

We begin by discussing two concepts that are central to all forms of virtue ethics, namely, virtue and practical wisdom. Then we note some of the features that distinguish different virtue ethical theories from one another before turning to objections that have been raised against virtue ethics and responses offered on its behalf. We conclude with a look at some of the directions in which future research might develop.

1.2 Practical Wisdom

2.1 eudaimonist virtue ethics, 2.2 agent-based and exemplarist virtue ethics, 2.3 target-centered virtue ethics, 2.4 platonistic virtue ethics, 3. objections to virtue ethics, 4. future directions, other internet resources, related entries, 1. preliminaries.

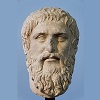

In the West, virtue ethics’ founding fathers are Plato and Aristotle, and in the East it can be traced back to Mencius and Confucius. It persisted as the dominant approach in Western moral philosophy until at least the Enlightenment, suffered a momentary eclipse during the nineteenth century, but re-emerged in Anglo-American philosophy in the late 1950s. It was heralded by Anscombe’s famous article “Modern Moral Philosophy” (Anscombe 1958) which crystallized an increasing dissatisfaction with the forms of deontology and utilitarianism then prevailing. Neither of them, at that time, paid attention to a number of topics that had always figured in the virtue ethics tradition—virtues and vices, motives and moral character, moral education, moral wisdom or discernment, friendship and family relationships, a deep concept of happiness, the role of the emotions in our moral life and the fundamentally important questions of what sorts of persons we should be and how we should live.

Its re-emergence had an invigorating effect on the other two approaches, many of whose proponents then began to address these topics in the terms of their favoured theory. (One consequence of this has been that it is now necessary to distinguish “virtue ethics” (the third approach) from “virtue theory”, a term which includes accounts of virtue within the other approaches.) Interest in Kant’s virtue theory has redirected philosophers’ attention to Kant’s long neglected Doctrine of Virtue , and utilitarians have developed consequentialist virtue theories (Driver 2001; Hurka 2001). It has also generated virtue ethical readings of philosophers other than Plato and Aristotle, such as Martineau, Hume and Nietzsche, and thereby different forms of virtue ethics have developed (Slote 2001; Swanton 2003, 2011a).

Although modern virtue ethics does not have to take a “neo-Aristotelian” or eudaimonist form (see section 2), almost any modern version still shows that its roots are in ancient Greek philosophy by the employment of three concepts derived from it. These are arête (excellence or virtue), phronesis (practical or moral wisdom) and eudaimonia (usually translated as happiness or flourishing). (See Annas 2011 for a short, clear, and authoritative account of all three.) We discuss the first two in the remainder of this section. Eudaimonia is discussed in connection with eudaimonist versions of virtue ethics in the next.

A virtue is an excellent trait of character. It is a disposition, well entrenched in its possessor—something that, as we say, goes all the way down, unlike a habit such as being a tea-drinker—to notice, expect, value, feel, desire, choose, act, and react in certain characteristic ways. To possess a virtue is to be a certain sort of person with a certain complex mindset. A significant aspect of this mindset is the wholehearted acceptance of a distinctive range of considerations as reasons for action. An honest person cannot be identified simply as one who, for example, practices honest dealing and does not cheat. If such actions are done merely because the agent thinks that honesty is the best policy, or because they fear being caught out, rather than through recognising “To do otherwise would be dishonest” as the relevant reason, they are not the actions of an honest person. An honest person cannot be identified simply as one who, for example, tells the truth because it is the truth, for one can have the virtue of honesty without being tactless or indiscreet. The honest person recognises “That would be a lie” as a strong (though perhaps not overriding) reason for not making certain statements in certain circumstances, and gives due, but not overriding, weight to “That would be the truth” as a reason for making them.

An honest person’s reasons and choices with respect to honest and dishonest actions reflect her views about honesty, truth, and deception—but of course such views manifest themselves with respect to other actions, and to emotional reactions as well. Valuing honesty as she does, she chooses, where possible to work with honest people, to have honest friends, to bring up her children to be honest. She disapproves of, dislikes, deplores dishonesty, is not amused by certain tales of chicanery, despises or pities those who succeed through deception rather than thinking they have been clever, is unsurprised, or pleased (as appropriate) when honesty triumphs, is shocked or distressed when those near and dear to her do what is dishonest and so on. Given that a virtue is such a multi-track disposition, it would obviously be reckless to attribute one to an agent on the basis of a single observed action or even a series of similar actions, especially if you don’t know the agent’s reasons for doing as she did (Sreenivasan 2002).

Possessing a virtue is a matter of degree. To possess such a disposition fully is to possess full or perfect virtue, which is rare, and there are a number of ways of falling short of this ideal (Athanassoulis 2000). Most people who can truly be described as fairly virtuous, and certainly markedly better than those who can truly be described as dishonest, self-centred and greedy, still have their blind spots—little areas where they do not act for the reasons one would expect. So someone honest or kind in most situations, and notably so in demanding ones, may nevertheless be trivially tainted by snobbery, inclined to be disingenuous about their forebears and less than kind to strangers with the wrong accent.

Further, it is not easy to get one’s emotions in harmony with one’s rational recognition of certain reasons for action. I may be honest enough to recognise that I must own up to a mistake because it would be dishonest not to do so without my acceptance being so wholehearted that I can own up easily, with no inner conflict. Following (and adapting) Aristotle, virtue ethicists draw a distinction between full or perfect virtue and “continence”, or strength of will. The fully virtuous do what they should without a struggle against contrary desires; the continent have to control a desire or temptation to do otherwise.

Describing the continent as “falling short” of perfect virtue appears to go against the intuition that there is something particularly admirable about people who manage to act well when it is especially hard for them to do so, but the plausibility of this depends on exactly what “makes it hard” (Foot 1978: 11–14). If it is the circumstances in which the agent acts—say that she is very poor when she sees someone drop a full purse or that she is in deep grief when someone visits seeking help—then indeed it is particularly admirable of her to restore the purse or give the help when it is hard for her to do so. But if what makes it hard is an imperfection in her character—the temptation to keep what is not hers, or a callous indifference to the suffering of others—then it is not.

Another way in which one can easily fall short of full virtue is through lacking phronesis —moral or practical wisdom.

The concept of a virtue is the concept of something that makes its possessor good: a virtuous person is a morally good, excellent or admirable person who acts and feels as she should. These are commonly accepted truisms. But it is equally common, in relation to particular (putative) examples of virtues to give these truisms up. We may say of someone that he is generous or honest “to a fault”. It is commonly asserted that someone’s compassion might lead them to act wrongly, to tell a lie they should not have told, for example, in their desire to prevent someone else’s hurt feelings. It is also said that courage, in a desperado, enables him to do far more wicked things than he would have been able to do if he were timid. So it would appear that generosity, honesty, compassion and courage despite being virtues, are sometimes faults. Someone who is generous, honest, compassionate, and courageous might not be a morally good person—or, if it is still held to be a truism that they are, then morally good people may be led by what makes them morally good to act wrongly! How have we arrived at such an odd conclusion?

The answer lies in too ready an acceptance of ordinary usage, which permits a fairly wide-ranging application of many of the virtue terms, combined, perhaps, with a modern readiness to suppose that the virtuous agent is motivated by emotion or inclination, not by rational choice. If one thinks of generosity or honesty as the disposition to be moved to action by generous or honest impulses such as the desire to give or to speak the truth, if one thinks of compassion as the disposition to be moved by the sufferings of others and to act on that emotion, if one thinks of courage as mere fearlessness or the willingness to face danger, then it will indeed seem obvious that these are all dispositions that can lead to their possessor’s acting wrongly. But it is also obvious, as soon as it is stated, that these are dispositions that can be possessed by children, and although children thus endowed (bar the “courageous” disposition) would undoubtedly be very nice children, we would not say that they were morally virtuous or admirable people. The ordinary usage, or the reliance on motivation by inclination, gives us what Aristotle calls “natural virtue”—a proto version of full virtue awaiting perfection by phronesis or practical wisdom.

Aristotle makes a number of specific remarks about phronesis that are the subject of much scholarly debate, but the (related) modern concept is best understood by thinking of what the virtuous morally mature adult has that nice children, including nice adolescents, lack. Both the virtuous adult and the nice child have good intentions, but the child is much more prone to mess things up because he is ignorant of what he needs to know in order to do what he intends. A virtuous adult is not, of course, infallible and may also, on occasion, fail to do what she intended to do through lack of knowledge, but only on those occasions on which the lack of knowledge is not culpable. So, for example, children and adolescents often harm those they intend to benefit either because they do not know how to set about securing the benefit or because their understanding of what is beneficial and harmful is limited and often mistaken. Such ignorance in small children is rarely, if ever culpable. Adults, on the other hand, are culpable if they mess things up by being thoughtless, insensitive, reckless, impulsive, shortsighted, and by assuming that what suits them will suit everyone instead of taking a more objective viewpoint. They are also culpable if their understanding of what is beneficial and harmful is mistaken. It is part of practical wisdom to know how to secure real benefits effectively; those who have practical wisdom will not make the mistake of concealing the hurtful truth from the person who really needs to know it in the belief that they are benefiting him.

Quite generally, given that good intentions are intentions to act well or “do the right thing”, we may say that practical wisdom is the knowledge or understanding that enables its possessor, unlike the nice adolescents, to do just that, in any given situation. The detailed specification of what is involved in such knowledge or understanding has not yet appeared in the literature, but some aspects of it are becoming well known. Even many deontologists now stress the point that their action-guiding rules cannot, reliably, be applied without practical wisdom, because correct application requires situational appreciation—the capacity to recognise, in any particular situation, those features of it that are morally salient. This brings out two aspects of practical wisdom.

One is that it characteristically comes only with experience of life. Amongst the morally relevant features of a situation may be the likely consequences, for the people involved, of a certain action, and this is something that adolescents are notoriously clueless about precisely because they are inexperienced. It is part of practical wisdom to be wise about human beings and human life. (It should go without saying that the virtuous are mindful of the consequences of possible actions. How could they fail to be reckless, thoughtless and short-sighted if they were not?)

The second is the practically wise agent’s capacity to recognise some features of a situation as more important than others, or indeed, in that situation, as the only relevant ones. The wise do not see things in the same way as the nice adolescents who, with their under-developed virtues, still tend to see the personally disadvantageous nature of a certain action as competing in importance with its honesty or benevolence or justice.

These aspects coalesce in the description of the practically wise as those who understand what is truly worthwhile, truly important, and thereby truly advantageous in life, who know, in short, how to live well.

2. Forms of Virtue Ethics

While all forms of virtue ethics agree that virtue is central and practical wisdom required, they differ in how they combine these and other concepts to illuminate what we should do in particular contexts and how we should live our lives as a whole. In what follows we sketch four distinct forms taken by contemporary virtue ethics, namely, a) eudaimonist virtue ethics, b) agent-based and exemplarist virtue ethics, c) target-centered virtue ethics, and d) Platonistic virtue ethics.

The distinctive feature of eudaimonist versions of virtue ethics is that they define virtues in terms of their relationship to eudaimonia . A virtue is a trait that contributes to or is a constituent of eudaimonia and we ought to develop virtues, the eudaimonist claims, precisely because they contribute to eudaimonia .

The concept of eudaimonia , a key term in ancient Greek moral philosophy, is standardly translated as “happiness” or “flourishing” and occasionally as “well-being.” Each translation has its disadvantages. The trouble with “flourishing” is that animals and even plants can flourish but eudaimonia is possible only for rational beings. The trouble with “happiness” is that in ordinary conversation it connotes something subjectively determined. It is for me, not for you, to pronounce on whether I am happy. If I think I am happy then I am—it is not something I can be wrong about (barring advanced cases of self-deception). Contrast my being healthy or flourishing. Here we have no difficulty in recognizing that I might think I was healthy, either physically or psychologically, or think that I was flourishing but be wrong. In this respect, “flourishing” is a better translation than “happiness”. It is all too easy to be mistaken about whether one’s life is eudaimon (the adjective from eudaimonia ) not simply because it is easy to deceive oneself, but because it is easy to have a mistaken conception of eudaimonia , or of what it is to live well as a human being, believing it to consist largely in physical pleasure or luxury for example.

Eudaimonia is, avowedly, a moralized or value-laden concept of happiness, something like “true” or “real” happiness or “the sort of happiness worth seeking or having.” It is thereby the sort of concept about which there can be substantial disagreement between people with different views about human life that cannot be resolved by appeal to some external standard on which, despite their different views, the parties to the disagreement concur (Hursthouse 1999: 188–189).

Most versions of virtue ethics agree that living a life in accordance with virtue is necessary for eudaimonia. This supreme good is not conceived of as an independently defined state (made up of, say, a list of non-moral goods that does not include virtuous activity) which exercise of the virtues might be thought to promote. It is, within virtue ethics, already conceived of as something of which virtuous activity is at least partially constitutive (Kraut 1989). Thereby virtue ethicists claim that a human life devoted to physical pleasure or the acquisition of wealth is not eudaimon , but a wasted life.

But although all standard versions of virtue ethics insist on that conceptual link between virtue and eudaimonia , further links are matters of dispute and generate different versions. For Aristotle, virtue is necessary but not sufficient—what is also needed are external goods which are a matter of luck. For Plato and the Stoics, virtue is both necessary and sufficient for eudaimonia (Annas 1993).

According to eudaimonist virtue ethics, the good life is the eudaimon life, and the virtues are what enable a human being to be eudaimon because the virtues just are those character traits that benefit their possessor in that way, barring bad luck. So there is a link between eudaimonia and what confers virtue status on a character trait. (For a discussion of the differences between eudaimonists see Baril 2014. For recent defenses of eudaimonism see Annas 2011; LeBar 2013b; Badhwar 2014; and Bloomfield 2014.)

Rather than deriving the normativity of virtue from the value of eudaimonia , agent-based virtue ethicists argue that other forms of normativity—including the value of eudaimonia —are traced back to and ultimately explained in terms of the motivational and dispositional qualities of agents.

It is unclear how many other forms of normativity must be explained in terms of the qualities of agents in order for a theory to count as agent-based. The two best-known agent-based theorists, Michael Slote and Linda Zagzebski, trace a wide range of normative qualities back to the qualities of agents. For example, Slote defines rightness and wrongness in terms of agents’ motivations: “[A]gent-based virtue ethics … understands rightness in terms of good motivations and wrongness in terms of the having of bad (or insufficiently good) motives” (2001: 14). Similarly, he explains the goodness of an action, the value of eudaimonia , the justice of a law or social institution, and the normativity of practical rationality in terms of the motivational and dispositional qualities of agents (2001: 99–100, 154, 2000). Zagzebski likewise defines right and wrong actions by reference to the emotions, motives, and dispositions of virtuous and vicious agents. For example, “A wrong act = an act that the phronimos characteristically would not do, and he would feel guilty if he did = an act such that it is not the case that he might do it = an act that expresses a vice = an act that is against a requirement of virtue (the virtuous self)” (Zagzebski 2004: 160). Her definitions of duties, good and bad ends, and good and bad states of affairs are similarly grounded in the motivational and dispositional states of exemplary agents (1998, 2004, 2010).

However, there could also be less ambitious agent-based approaches to virtue ethics (see Slote 1997). At the very least, an agent-based approach must be committed to explaining what one should do by reference to the motivational and dispositional states of agents. But this is not yet a sufficient condition for counting as an agent-based approach, since the same condition will be met by every virtue ethical account. For a theory to count as an agent-based form of virtue ethics it must also be the case that the normative properties of motivations and dispositions cannot be explained in terms of the normative properties of something else (such as eudaimonia or states of affairs) which is taken to be more fundamental.

Beyond this basic commitment, there is room for agent-based theories to be developed in a number of different directions. The most important distinguishing factor has to do with how motivations and dispositions are taken to matter for the purposes of explaining other normative qualities. For Slote what matters are this particular agent’s actual motives and dispositions . The goodness of action A, for example, is derived from the agent’s motives when she performs A. If those motives are good then the action is good, if not then not. On Zagzebski’s account, by contrast, a good or bad, right or wrong action is defined not by this agent’s actual motives but rather by whether this is the sort of action a virtuously motivated agent would perform (Zagzebski 2004: 160). Appeal to the virtuous agent’s hypothetical motives and dispositions enables Zagzebski to distinguish between performing the right action and doing so for the right reasons (a distinction that, as Brady (2004) observes, Slote has trouble drawing).

Another point on which agent-based forms of virtue ethics might differ concerns how one identifies virtuous motivations and dispositions. According to Zagzebski’s exemplarist account, “We do not have criteria for goodness in advance of identifying the exemplars of goodness” (Zagzebski 2004: 41). As we observe the people around us, we find ourselves wanting to be like some of them (in at least some respects) and not wanting to be like others. The former provide us with positive exemplars and the latter with negative ones. Our understanding of better and worse motivations and virtuous and vicious dispositions is grounded in these primitive responses to exemplars (2004: 53). This is not to say that every time we act we stop and ask ourselves what one of our exemplars would do in this situations. Our moral concepts become more refined over time as we encounter a wider variety of exemplars and begin to draw systematic connections between them, noting what they have in common, how they differ, and which of these commonalities and differences matter, morally speaking. Recognizable motivational profiles emerge and come to be labeled as virtues or vices, and these, in turn, shape our understanding of the obligations we have and the ends we should pursue. However, even though the systematising of moral thought can travel a long way from our starting point, according to the exemplarist it never reaches a stage where reference to exemplars is replaced by the recognition of something more fundamental. At the end of the day, according to the exemplarist, our moral system still rests on our basic propensity to take a liking (or disliking) to exemplars. Nevertheless, one could be an agent-based theorist without advancing the exemplarist’s account of the origins or reference conditions for judgments of good and bad, virtuous and vicious.

The touchstone for eudaimonist virtue ethicists is a flourishing human life. For agent-based virtue ethicists it is an exemplary agent’s motivations. The target-centered view developed by Christine Swanton (2003), by contrast, begins with our existing conceptions of the virtues. We already have a passable idea of which traits are virtues and what they involve. Of course, this untutored understanding can be clarified and improved, and it is one of the tasks of the virtue ethicist to help us do precisely that. But rather than stripping things back to something as basic as the motivations we want to imitate or building it up to something as elaborate as an entire flourishing life, the target-centered view begins where most ethics students find themselves, namely, with the idea that generosity, courage, self-discipline, compassion, and the like get a tick of approval. It then examines what these traits involve.

A complete account of virtue will map out 1) its field , 2) its mode of responsiveness, 3) its basis of moral acknowledgment, and 4) its target . Different virtues are concerned with different fields . Courage, for example, is concerned with what might harm us, whereas generosity is concerned with the sharing of time, talent, and property. The basis of acknowledgment of a virtue is the feature within the virtue’s field to which it responds. To continue with our previous examples, generosity is attentive to the benefits that others might enjoy through one’s agency, and courage responds to threats to value, status, or the bonds that exist between oneself and particular others, and the fear such threats might generate. A virtue’s mode has to do with how it responds to the bases of acknowledgment within its field. Generosity promotes a good, namely, another’s benefit, whereas courage defends a value, bond, or status. Finally, a virtue’s target is that at which it is aimed. Courage aims to control fear and handle danger, while generosity aims to share time, talents, or possessions with others in ways that benefit them.

A virtue , on a target-centered account, “is a disposition to respond to, or acknowledge, items within its field or fields in an excellent or good enough way” (Swanton 2003: 19). A virtuous act is an act that hits the target of a virtue, which is to say that it succeeds in responding to items in its field in the specified way (233). Providing a target-centered definition of a right action requires us to move beyond the analysis of a single virtue and the actions that follow from it. This is because a single action context may involve a number of different, overlapping fields. Determination might lead me to persist in trying to complete a difficult task even if doing so requires a singleness of purpose. But love for my family might make a different use of my time and attention. In order to define right action a target-centered view must explain how we handle different virtues’ conflicting claims on our resources. There are at least three different ways to address this challenge. A perfectionist target-centered account would stipulate, “An act is right if and only if it is overall virtuous, and that entails that it is the, or a, best action possible in the circumstances” (239–240). A more permissive target-centered account would not identify ‘right’ with ‘best’, but would allow an action to count as right provided “it is good enough even if not the (or a) best action” (240). A minimalist target-centered account would not even require an action to be good in order to be right. On such a view, “An act is right if and only if it is not overall vicious” (240). (For further discussion of target-centered virtue ethics see Van Zyl 2014; and Smith 2016).

The fourth form a virtue ethic might adopt takes its inspiration from Plato. The Socrates of Plato’s dialogues devotes a great deal of time to asking his fellow Athenians to explain the nature of virtues like justice, courage, piety, and wisdom. So it is clear that Plato counts as a virtue theorist. But it is a matter of some debate whether he should be read as a virtue ethicist (White 2015). What is not open to debate is whether Plato has had an important influence on the contemporary revival of interest in virtue ethics. A number of those who have contributed to the revival have done so as Plato scholars (e.g., Prior 1991; Kamtekar 1998; Annas 1999; and Reshotko 2006). However, often they have ended up championing a eudaimonist version of virtue ethics (see Prior 2001 and Annas 2011), rather than a version that would warrant a separate classification. Nevertheless, there are two variants that call for distinct treatment.

Timothy Chappell takes the defining feature of Platonistic virtue ethics to be that “Good agency in the truest and fullest sense presupposes the contemplation of the Form of the Good” (2014). Chappell follows Iris Murdoch in arguing that “In the moral life the enemy is the fat relentless ego” (Murdoch 1971: 51). Constantly attending to our needs, our desires, our passions, and our thoughts skews our perspective on what the world is actually like and blinds us to the goods around us. Contemplating the goodness of something we encounter—which is to say, carefully attending to it “for its own sake, in order to understand it” (Chappell 2014: 300)—breaks this natural tendency by drawing our attention away from ourselves. Contemplating such goodness with regularity makes room for new habits of thought that focus more readily and more honestly on things other than the self. It alters the quality of our consciousness. And “anything which alters consciousness in the direction of unselfishness, objectivity, and realism is to be connected with virtue” (Murdoch 1971: 82). The virtues get defined, then, in terms of qualities that help one “pierce the veil of selfish consciousness and join the world as it really is” (91). And good agency is defined by the possession and exercise of such virtues. Within Chappell’s and Murdoch’s framework, then, not all normative properties get defined in terms of virtue. Goodness, in particular, is not so defined. But the kind of goodness which is possible for creatures like us is defined by virtue, and any answer to the question of what one should do or how one should live will appeal to the virtues.

Another Platonistic variant of virtue ethics is exemplified by Robert Merrihew Adams. Unlike Murdoch and Chappell, his starting point is not a set of claims about our consciousness of goodness. Rather, he begins with an account of the metaphysics of goodness. Like Murdoch and others influenced by Platonism, Adams’s account of goodness is built around a conception of a supremely perfect good. And like Augustine, Adams takes that perfect good to be God. God is both the exemplification and the source of all goodness. Other things are good, he suggests, to the extent that they resemble God (Adams 1999).

The resemblance requirement identifies a necessary condition for being good, but it does not yet give us a sufficient condition. This is because there are ways in which finite creatures might resemble God that would not be suitable to the type of creature they are. For example, if God were all-knowing, then the belief, “I am all-knowing,” would be a suitable belief for God to have. In God, such a belief—because true—would be part of God’s perfection. However, as neither you nor I are all-knowing, the belief, “I am all-knowing,” in one of us would not be good. To rule out such cases we need to introduce another factor. That factor is the fitting response to goodness, which Adams suggests is love. Adams uses love to weed out problematic resemblances: “being excellent in the way that a finite thing can be consists in resembling God in a way that could serve God as a reason for loving the thing” (Adams 1999: 36).

Virtues come into the account as one of the ways in which some things (namely, persons) could resemble God. “[M]ost of the excellences that are most important to us, and of whose value we are most confident, are excellences of persons or of qualities or actions or works or lives or stories of persons” (1999: 42). This is one of the reasons Adams offers for conceiving of the ideal of perfection as a personal God, rather than an impersonal form of the Good. Many of the excellences of persons of which we are most confident are virtues such as love, wisdom, justice, patience, and generosity. And within many theistic traditions, including Adams’s own Christian tradition, such virtues are commonly attributed to divine agents.

A Platonistic account like the one Adams puts forward in Finite and Infinite Goods clearly does not derive all other normative properties from the virtues (for a discussion of the relationship between this view and the one he puts forward in A Theory of Virtue (2006) see Pettigrove 2014). Goodness provides the normative foundation. Virtues are not built on that foundation; rather, as one of the varieties of goodness of whose value we are most confident, virtues form part of the foundation. Obligations, by contrast, come into the account at a different level. Moral obligations, Adams argues, are determined by the expectations and demands that “arise in a relationship or system of relationships that is good or valuable” (1999: 244). Other things being equal, the more virtuous the parties to the relationship, the more binding the obligation. Thus, within Adams’s account, the good (which includes virtue) is prior to the right. However, once good relationships have given rise to obligations, those obligations take on a life of their own. Their bindingness is not traced directly to considerations of goodness. Rather, they are determined by the expectations of the parties and the demands of the relationship.

A number of objections have been raised against virtue ethics, some of which bear more directly on one form of virtue ethics than on others. In this section we consider eight objections, namely, the a) application, b) adequacy, c) relativism, d) conflict, e) self-effacement, f) justification, g) egoism, and h) situationist problems.

a) In the early days of virtue ethics’ revival, the approach was associated with an “anti-codifiability” thesis about ethics, directed against the prevailing pretensions of normative theory. At the time, utilitarians and deontologists commonly (though not universally) held that the task of ethical theory was to come up with a code consisting of universal rules or principles (possibly only one, as in the case of act-utilitarianism) which would have two significant features: i) the rule(s) would amount to a decision procedure for determining what the right action was in any particular case; ii) the rule(s) would be stated in such terms that any non-virtuous person could understand and apply it (them) correctly.

Virtue ethicists maintained, contrary to these two claims, that it was quite unrealistic to imagine that there could be such a code (see, in particular, McDowell 1979). The results of attempts to produce and employ such a code, in the heady days of the 1960s and 1970s, when medical and then bioethics boomed and bloomed, tended to support the virtue ethicists’ claim. More and more utilitarians and deontologists found themselves agreed on their general rules but on opposite sides of the controversial moral issues in contemporary discussion. It came to be recognised that moral sensitivity, perception, imagination, and judgement informed by experience— phronesis in short—is needed to apply rules or principles correctly. Hence many (though by no means all) utilitarians and deontologists have explicitly abandoned (ii) and much less emphasis is placed on (i).

Nevertheless, the complaint that virtue ethics does not produce codifiable principles is still a commonly voiced criticism of the approach, expressed as the objection that it is, in principle, unable to provide action-guidance.

Initially, the objection was based on a misunderstanding. Blinkered by slogans that described virtue ethics as “concerned with Being rather than Doing,” as addressing “What sort of person should I be?” but not “What should I do?” as being “agent-centered rather than act-centered,” its critics maintained that it was unable to provide action-guidance. Hence, rather than being a normative rival to utilitarian and deontological ethics, it could claim to be no more than a valuable supplement to them. The rather odd idea was that all virtue ethics could offer was, “Identify a moral exemplar and do what he would do,” as though the university student trying to decide whether to study music (her preference) or engineering (her parents’ preference) was supposed to ask herself, “What would Socrates study if he were in my circumstances?”

But the objection failed to take note of Anscombe’s hint that a great deal of specific action guidance could be found in rules employing the virtue and vice terms (“v-rules”) such as “Do what is honest/charitable; do not do what is dishonest/uncharitable” (Hursthouse 1999). (It is a noteworthy feature of our virtue and vice vocabulary that, although our list of generally recognised virtue terms is comparatively short, our list of vice terms is remarkably, and usefully, long, far exceeding anything that anyone who thinks in terms of standard deontological rules has ever come up with. Much invaluable action guidance comes from avoiding courses of action that would be irresponsible, feckless, lazy, inconsiderate, uncooperative, harsh, intolerant, selfish, mercenary, indiscreet, tactless, arrogant, unsympathetic, cold, incautious, unenterprising, pusillanimous, feeble, presumptuous, rude, hypocritical, self-indulgent, materialistic, grasping, short-sighted, vindictive, calculating, ungrateful, grudging, brutal, profligate, disloyal, and on and on.)

(b) A closely related objection has to do with whether virtue ethics can provide an adequate account of right action. This worry can take two forms. (i) One might think a virtue ethical account of right action is extensionally inadequate. It is possible to perform a right action without being virtuous and a virtuous person can occasionally perform the wrong action without that calling her virtue into question. If virtue is neither necessary nor sufficient for right action, one might wonder whether the relationship between rightness/wrongness and virtue/vice is close enough for the former to be identified in terms of the latter. (ii) Alternatively, even if one thought it possible to produce a virtue ethical account that picked out all (and only) right actions, one might still think that at least in some cases virtue is not what explains rightness (Adams 2006:6–8).

Some virtue ethicists respond to the adequacy objection by rejecting the assumption that virtue ethics ought to be in the business of providing an account of right action in the first place. Following in the footsteps of Anscombe (1958) and MacIntyre (1985), Talbot Brewer (2009) argues that to work with the categories of rightness and wrongness is already to get off on the wrong foot. Contemporary conceptions of right and wrong action, built as they are around a notion of moral duty that presupposes a framework of divine (or moral) law or around a conception of obligation that is defined in contrast to self-interest, carry baggage the virtue ethicist is better off without. Virtue ethics can address the questions of how one should live, what kind of person one should become, and even what one should do without that committing it to providing an account of ‘right action’. One might choose, instead, to work with aretaic concepts (defined in terms of virtues and vices) and axiological concepts (defined in terms of good and bad, better and worse) and leave out deontic notions (like right/wrong action, duty, and obligation) altogether.

Other virtue ethicists wish to retain the concept of right action but note that in the current philosophical discussion a number of distinct qualities march under that banner. In some contexts, ‘right action’ identifies the best action an agent might perform in the circumstances. In others, it designates an action that is commendable (even if not the best possible). In still others, it picks out actions that are not blameworthy (even if not commendable). A virtue ethicist might choose to define one of these—for example, the best action—in terms of virtues and vices, but appeal to other normative concepts—such as legitimate expectations—when defining other conceptions of right action.

As we observed in section 2, a virtue ethical account need not attempt to reduce all other normative concepts to virtues and vices. What is required is simply (i) that virtue is not reduced to some other normative concept that is taken to be more fundamental and (ii) that some other normative concepts are explained in terms of virtue and vice. This takes the sting out of the adequacy objection, which is most compelling against versions of virtue ethics that attempt to define all of the senses of ‘right action’ in terms of virtues. Appealing to virtues and vices makes it much easier to achieve extensional adequacy. Making room for normative concepts that are not taken to be reducible to virtue and vice concepts makes it even easier to generate a theory that is both extensionally and explanatorily adequate. Whether one needs other concepts and, if so, how many, is still a matter of debate among virtue ethicists, as is the question of whether virtue ethics even ought to be offering an account of right action. Either way virtue ethicists have resources available to them to address the adequacy objection.

Insofar as the different versions of virtue ethics all retain an emphasis on the virtues, they are open to the familiar problem of (c) the charge of cultural relativity. Is it not the case that different cultures embody different virtues, (MacIntyre 1985) and hence that the v-rules will pick out actions as right or wrong only relative to a particular culture? Different replies have been made to this charge. One—the tu quoque , or “partners in crime” response—exhibits a quite familiar pattern in virtue ethicists’ defensive strategy (Solomon 1988). They admit that, for them, cultural relativism is a challenge, but point out that it is just as much a problem for the other two approaches. The (putative) cultural variation in character traits regarded as virtues is no greater—indeed markedly less—than the cultural variation in rules of conduct, and different cultures have different ideas about what constitutes happiness or welfare. That cultural relativity should be a problem common to all three approaches is hardly surprising. It is related, after all, to the “justification problem” ( see below ) the quite general metaethical problem of justifying one’s moral beliefs to those who disagree, whether they be moral sceptics, pluralists or from another culture.

A bolder strategy involves claiming that virtue ethics has less difficulty with cultural relativity than the other two approaches. Much cultural disagreement arises, it may be claimed, from local understandings of the virtues, but the virtues themselves are not relative to culture (Nussbaum 1993).

Another objection to which the tu quoque response is partially appropriate is (d) “the conflict problem.” What does virtue ethics have to say about dilemmas—cases in which, apparently, the requirements of different virtues conflict because they point in opposed directions? Charity prompts me to kill the person who would be better off dead, but justice forbids it. Honesty points to telling the hurtful truth, kindness and compassion to remaining silent or even lying. What shall I do? Of course, the same sorts of dilemmas are generated by conflicts between deontological rules. Deontology and virtue ethics share the conflict problem (and are happy to take it on board rather than follow some of the utilitarians in their consequentialist resolutions of such dilemmas) and in fact their strategies for responding to it are parallel. Both aim to resolve a number of dilemmas by arguing that the conflict is merely apparent; a discriminating understanding of the virtues or rules in question, possessed only by those with practical wisdom, will perceive that, in this particular case, the virtues do not make opposing demands or that one rule outranks another, or has a certain exception clause built into it. Whether this is all there is to it depends on whether there are any irresolvable dilemmas. If there are, proponents of either normative approach may point out reasonably that it could only be a mistake to offer a resolution of what is, ex hypothesi , irresolvable.

Another problem arguably shared by all three approaches is (e), that of being self-effacing. An ethical theory is self-effacing if, roughly, whatever it claims justifies a particular action, or makes it right, had better not be the agent’s motive for doing it. Michael Stocker (1976) originally introduced it as a problem for deontology and consequentialism. He pointed out that the agent who, rightly, visits a friend in hospital will rather lessen the impact of his visit on her if he tells her either that he is doing it because it is his duty or because he thought it would maximize the general happiness. But as Simon Keller observes, she won’t be any better pleased if he tells her that he is visiting her because it is what a virtuous agent would do, so virtue ethics would appear to have the problem too (Keller 2007). However, virtue ethics’ defenders have argued that not all forms of virtue ethics are subject to this objection (Pettigrove 2011) and those that are are not seriously undermined by the problem (Martinez 2011).

Another problem for virtue ethics, which is shared by both utilitarianism and deontology, is (f) “the justification problem.” Abstractly conceived, this is the problem of how we justify or ground our ethical beliefs, an issue that is hotly debated at the level of metaethics. In its particular versions, for deontology there is the question of how to justify its claims that certain moral rules are the correct ones, and for utilitarianism of how to justify its claim that all that really matters morally are consequences for happiness or well-being. For virtue ethics, the problem concerns the question of which character traits are the virtues.

In the metaethical debate, there is widespread disagreement about the possibility of providing an external foundation for ethics—“external” in the sense of being external to ethical beliefs—and the same disagreement is found amongst deontologists and utilitarians. Some believe that their normative ethics can be placed on a secure basis, resistant to any form of scepticism, such as what anyone rationally desires, or would accept or agree on, regardless of their ethical outlook; others that it cannot.

Virtue ethicists have eschewed any attempt to ground virtue ethics in an external foundation while continuing to maintain that their claims can be validated. Some follow a form of Rawls’s coherentist approach (Slote 2001; Swanton 2003); neo-Aristotelians a form of ethical naturalism.

A misunderstanding of eudaimonia as an unmoralized concept leads some critics to suppose that the neo-Aristotelians are attempting to ground their claims in a scientific account of human nature and what counts, for a human being, as flourishing. Others assume that, if this is not what they are doing, they cannot be validating their claims that, for example, justice, charity, courage, and generosity are virtues. Either they are illegitimately helping themselves to Aristotle’s discredited natural teleology (Williams 1985) or producing mere rationalizations of their own personal or culturally inculcated values. But McDowell, Foot, MacIntyre and Hursthouse have all outlined versions of a third way between these two extremes. Eudaimonia in virtue ethics, is indeed a moralized concept, but it is not only that. Claims about what constitutes flourishing for human beings no more float free of scientific facts about what human beings are like than ethological claims about what constitutes flourishing for elephants. In both cases, the truth of the claims depends in part on what kind of animal they are and what capacities, desires and interests the humans or elephants have.

The best available science today (including evolutionary theory and psychology) supports rather than undermines the ancient Greek assumption that we are social animals, like elephants and wolves and unlike polar bears. No rationalizing explanation in terms of anything like a social contract is needed to explain why we choose to live together, subjugating our egoistic desires in order to secure the advantages of co-operation. Like other social animals, our natural impulses are not solely directed towards our own pleasures and preservation, but include altruistic and cooperative ones.

This basic fact about us should make more comprehensible the claim that the virtues are at least partially constitutive of human flourishing and also undercut the objection that virtue ethics is, in some sense, egoistic.

(g) The egoism objection has a number of sources. One is a simple confusion. Once it is understood that the fully virtuous agent characteristically does what she should without inner conflict, it is triumphantly asserted that “she is only doing what she wants to do and hence is being selfish.” So when the generous person gives gladly, as the generous are wont to do, it turns out she is not generous and unselfish after all, or at least not as generous as the one who greedily wants to hang on to everything she has but forces herself to give because she thinks she should! A related version ascribes bizarre reasons to the virtuous agent, unjustifiably assuming that she acts as she does because she believes that acting thus on this occasion will help her to achieve eudaimonia. But “the virtuous agent” is just “the agent with the virtues” and it is part of our ordinary understanding of the virtue terms that each carries with it its own typical range of reasons for acting. The virtuous agent acts as she does because she believes that someone’s suffering will be averted, or someone benefited, or the truth established, or a debt repaid, or … thereby.

It is the exercise of the virtues during one’s life that is held to be at least partially constitutive of eudaimonia , and this is consistent with recognising that bad luck may land the virtuous agent in circumstances that require her to give up her life. Given the sorts of considerations that courageous, honest, loyal, charitable people wholeheartedly recognise as reasons for action, they may find themselves compelled to face danger for a worthwhile end, to speak out in someone’s defence, or refuse to reveal the names of their comrades, even when they know that this will inevitably lead to their execution, to share their last crust and face starvation. On the view that the exercise of the virtues is necessary but not sufficient for eudaimonia , such cases are described as those in which the virtuous agent sees that, as things have unfortunately turned out, eudaimonia is not possible for them (Foot 2001, 95). On the Stoical view that it is both necessary and sufficient, a eudaimon life is a life that has been successfully lived (where “success” of course is not to be understood in a materialistic way) and such people die knowing not only that they have made a success of their lives but that they have also brought their lives to a markedly successful completion. Either way, such heroic acts can hardly be regarded as egoistic.

A lingering suggestion of egoism may be found in the misconceived distinction between so-called “self-regarding” and “other-regarding” virtues. Those who have been insulated from the ancient tradition tend to regard justice and benevolence as real virtues, which benefit others but not their possessor, and prudence, fortitude and providence (the virtue whose opposite is “improvidence” or being a spendthrift) as not real virtues at all because they benefit only their possessor. This is a mistake on two counts. Firstly, justice and benevolence do, in general, benefit their possessors, since without them eudaimonia is not possible. Secondly, given that we live together, as social animals, the “self-regarding” virtues do benefit others—those who lack them are a great drain on, and sometimes grief to, those who are close to them (as parents with improvident or imprudent adult offspring know only too well).

The most recent objection (h) to virtue ethics claims that work in “situationist” social psychology shows that there are no such things as character traits and thereby no such things as virtues for virtue ethics to be about (Doris 1998; Harman 1999). In reply, some virtue ethicists have argued that the social psychologists’ studies are irrelevant to the multi-track disposition (see above) that a virtue is supposed to be (Sreenivasan 2002; Kamtekar 2004). Mindful of just how multi-track it is, they agree that it would be reckless in the extreme to ascribe a demanding virtue such as charity to people of whom they know no more than that they have exhibited conventional decency; this would indeed be “a fundamental attribution error.” Others have worked to develop alternative, empirically grounded conceptions of character traits (Snow 2010; Miller 2013 and 2014; however see Upton 2016 for objections to Miller). There have been other responses as well (summarized helpfully in Prinz 2009 and Miller 2014). Notable among these is a response by Adams (2006, echoing Merritt 2000) who steers a middle road between “no character traits at all” and the exacting standard of the Aristotelian conception of virtue which, because of its emphasis on phronesis, requires a high level of character integration. On his conception, character traits may be “frail and fragmentary” but still virtues, and not uncommon. But giving up the idea that practical wisdom is the heart of all the virtues, as Adams has to do, is a substantial sacrifice, as Russell (2009) and Kamtekar (2010) argue.

Even though the “situationist challenge” has left traditional virtue ethicists unmoved, it has generated a healthy engagement with empirical psychological literature, which has also been fuelled by the growing literature on Foot’s Natural Goodness and, quite independently, an upsurge of interest in character education (see below).

Over the past thirty-five years most of those contributing to the revival of virtue ethics have worked within a neo-Aristotelian, eudaimonist framework. However, as noted in section 2, other forms of virtue ethics have begun to emerge. Theorists have begun to turn to philosophers like Hutcheson, Hume, Nietzsche, Martineau, and Heidegger for resources they might use to develop alternatives (see Russell 2006; Swanton 2013 and 2015; Taylor 2015; and Harcourt 2015). Others have turned their attention eastward, exploring Confucian, Buddhist, and Hindu traditions (Yu 2007; Slingerland 2011; Finnigan and Tanaka 2011; McRae 2012; Angle and Slote 2013; Davis 2014; Flanagan 2015; Perrett and Pettigrove 2015; and Sim 2015). These explorations promise to open up new avenues for the development of virtue ethics.