Research Question Examples 🧑🏻🏫

25+ Practical Examples & Ideas To Help You Get Started

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | October 2023

A well-crafted research question (or set of questions) sets the stage for a robust study and meaningful insights. But, if you’re new to research, it’s not always clear what exactly constitutes a good research question. In this post, we’ll provide you with clear examples of quality research questions across various disciplines, so that you can approach your research project with confidence!

Research Question Examples

- Psychology research questions

- Business research questions

- Education research questions

- Healthcare research questions

- Computer science research questions

Examples: Psychology

Let’s start by looking at some examples of research questions that you might encounter within the discipline of psychology.

How does sleep quality affect academic performance in university students?

This question is specific to a population (university students) and looks at a direct relationship between sleep and academic performance, both of which are quantifiable and measurable variables.

What factors contribute to the onset of anxiety disorders in adolescents?

The question narrows down the age group and focuses on identifying multiple contributing factors. There are various ways in which it could be approached from a methodological standpoint, including both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Do mindfulness techniques improve emotional well-being?

This is a focused research question aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of a specific intervention.

How does early childhood trauma impact adult relationships?

This research question targets a clear cause-and-effect relationship over a long timescale, making it focused but comprehensive.

Is there a correlation between screen time and depression in teenagers?

This research question focuses on an in-demand current issue and a specific demographic, allowing for a focused investigation. The key variables are clearly stated within the question and can be measured and analysed (i.e., high feasibility).

Examples: Business/Management

Next, let’s look at some examples of well-articulated research questions within the business and management realm.

How do leadership styles impact employee retention?

This is an example of a strong research question because it directly looks at the effect of one variable (leadership styles) on another (employee retention), allowing from a strongly aligned methodological approach.

What role does corporate social responsibility play in consumer choice?

Current and precise, this research question can reveal how social concerns are influencing buying behaviour by way of a qualitative exploration.

Does remote work increase or decrease productivity in tech companies?

Focused on a particular industry and a hot topic, this research question could yield timely, actionable insights that would have high practical value in the real world.

How do economic downturns affect small businesses in the homebuilding industry?

Vital for policy-making, this highly specific research question aims to uncover the challenges faced by small businesses within a certain industry.

Which employee benefits have the greatest impact on job satisfaction?

By being straightforward and specific, answering this research question could provide tangible insights to employers.

Examples: Education

Next, let’s look at some potential research questions within the education, training and development domain.

How does class size affect students’ academic performance in primary schools?

This example research question targets two clearly defined variables, which can be measured and analysed relatively easily.

Do online courses result in better retention of material than traditional courses?

Timely, specific and focused, answering this research question can help inform educational policy and personal choices about learning formats.

What impact do US public school lunches have on student health?

Targeting a specific, well-defined context, the research could lead to direct changes in public health policies.

To what degree does parental involvement improve academic outcomes in secondary education in the Midwest?

This research question focuses on a specific context (secondary education in the Midwest) and has clearly defined constructs.

What are the negative effects of standardised tests on student learning within Oklahoma primary schools?

This research question has a clear focus (negative outcomes) and is narrowed into a very specific context.

Need a helping hand?

Examples: Healthcare

Shifting to a different field, let’s look at some examples of research questions within the healthcare space.

What are the most effective treatments for chronic back pain amongst UK senior males?

Specific and solution-oriented, this research question focuses on clear variables and a well-defined context (senior males within the UK).

How do different healthcare policies affect patient satisfaction in public hospitals in South Africa?

This question is has clearly defined variables and is narrowly focused in terms of context.

Which factors contribute to obesity rates in urban areas within California?

This question is focused yet broad, aiming to reveal several contributing factors for targeted interventions.

Does telemedicine provide the same perceived quality of care as in-person visits for diabetes patients?

Ideal for a qualitative study, this research question explores a single construct (perceived quality of care) within a well-defined sample (diabetes patients).

Which lifestyle factors have the greatest affect on the risk of heart disease?

This research question aims to uncover modifiable factors, offering preventive health recommendations.

Examples: Computer Science

Last but certainly not least, let’s look at a few examples of research questions within the computer science world.

What are the perceived risks of cloud-based storage systems?

Highly relevant in our digital age, this research question would align well with a qualitative interview approach to better understand what users feel the key risks of cloud storage are.

Which factors affect the energy efficiency of data centres in Ohio?

With a clear focus, this research question lays a firm foundation for a quantitative study.

How do TikTok algorithms impact user behaviour amongst new graduates?

While this research question is more open-ended, it could form the basis for a qualitative investigation.

What are the perceived risk and benefits of open-source software software within the web design industry?

Practical and straightforward, the results could guide both developers and end-users in their choices.

Remember, these are just examples…

In this post, we’ve tried to provide a wide range of research question examples to help you get a feel for what research questions look like in practice. That said, it’s important to remember that these are just examples and don’t necessarily equate to good research topics . If you’re still trying to find a topic, check out our topic megalist for inspiration.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

Posing a Researchable Question

You are here

Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves. —Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

Whenever I talk to teachers about doing teacher research, I start by exhorting them to question everything and, following Rainer Maria Rilke’s advice, to love the questions. It is appropriate advice because teaching, by its very nature, is an inquiry process—a serious encounter with life’s most meaningful and often baffling questions. Questions like “Why does one activity engage the children so thoroughly one day, yet totally bomb the next day?” and “How can I make a connection with those children who seem distant and unwilling to interact with others?” are typical of the kinds of questions teachers ask every day as they confront the complex world of the classroom.

If we take seriously the complexity of teaching, then we understand the need for teachers to have an active role in the process of finding the answers to their meaningful questions. When teachers ask questions about the what, how, and why of what they do and think about alternatives to their practices, they incorporate the element of inquiry into their teaching. When teachers systematically and intentionally pursue their questions, using methods that are meaningful to them to collect, analyze, and interpret data, they demonstrate the value of teacher research as a vehicle for promoting self-reflection and decision making. Most important, as they begin to investigate questions that are to their own situations, they move from conveyers of knowledge about teaching and learning to creators of their own knowledge.

The focus of this article is how to pose a teacher research question. More precisely, the aim is to examine the components of a researchable question and offer suggestions for how to go about the question in a way that makes it researchable. Researchable questions emerge from areas teachers consider problematic (i.e., puzzling, intriguing, astonishing) or from issues they simply want to know more about.

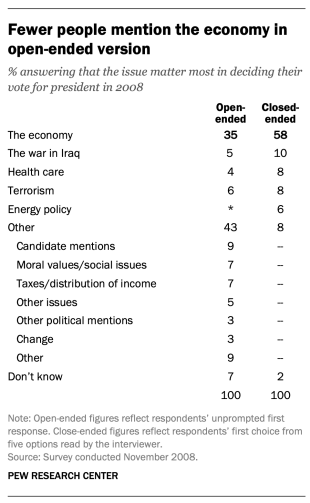

Not all teaching questions are researchable

Teachers are questioners, but not all questions are inquiry oriented. In many cases, especially in traditional classrooms, teachers ask children questions to elicit a specific response (“What is your favorite color?,” “What color do we make when we mix red and blue paint?”) or to get children to think about what they are learning (“What is happening in this story?,” “Why do you think that?”). These questions serve primarily as a means to help children recall information, to check on children’s thinking, and to assess children’s understanding of certain material. Teaching questions

- May be open or closed, but are usually closed

- Are typically phrased as yes or no questions

- Seek answers to specific problems

- Tend to have clear boundaries

- Often carry the outlines of their solutions

- Involve thought, but may lack emotion or passion

While these questions have their place in teaching, they do not serve as an invitation to investigate further. As Clifford and Marinucci (2008) emphasize, an important characteristic of inquiry is that it evokes stimulating questions that lead to further questions.

What are the questions worth asking?

Teachers ask other kinds of questions, and like the children they teach, teachers are curious. They have the desire to know and the need to understand. In genuine inquiry, however, teachers ask and pursue questions in order to make critical decisions about their practice, to assess the viability of their methods and techniques, and to rethink assumptions that may no longer fit their classroom experiences. I like to think about teacher inquiry as the continuous engagement with questions worth asking—the wonderings worth pursuing that lead to a greater understanding of how to teach and how children learn.

Inquiry typically begins with reflection on what teachers think, what they believe and value, and ultimately who they are. That is, inquiry may stem from teachers’ assumptions, identities, and images of teaching and learning. The impetus to pursue a question often arises out of personal curiosity, a nagging issue, a keen interest, or a perspective that begs examination in order to understand something more fully or to see it in different ways. When teachers pose questions worth asking, they do so from an attitude—a stance—of inquiry, and they see their classrooms as laboratories for wonder and discovery.

Questions worth asking are questions that teachers care about—questions that come from real-world obstacles and dilemmas. They are problems of meaning that develop gradually after careful observation and deliberation about why certain things are happening in the classroom. These questions are not aimed at quick fix solutions; rather, they involve the desire to understand teaching and learning in profound ways. Questions worth asking have the power to change us and to cause us to see ourselves and the children we teach in new ways. They engage the mind and the passion of the teacher; encourage wonder about the space between what is known and what is knowable; and allow for possibilities that are neither imagined nor anticipated (Hubbard & Power 2003).

However, while all teachers may have wonderings worth pursuing, not all questions are researchable. What makes a question researchable?

What is a researchable question?

One of the central characteristics of inquiry is that it evokes an invitation to investigate further. How does one begin to frame a question in a way that will yield the best research? I believe that it is important to start by talking with a trusted colleague or fellow teacher who understands the uncertainties and dilemmas of teaching. I will revisit this idea shortly. First, let us look at the kinds of questions one can ask to start on the path to developing a researchable question:

- What interests me?

- What puzzles or intrigues me?

- What do I wonder about my teaching?

- What do I want to know or better understand about children as learners or about myself as a teacher, a learner, or a person?

- What would I like to change or improve?

- Why is this important?

- What are my assumptions or hypotheses?

- What have my initial observations revealed to me?

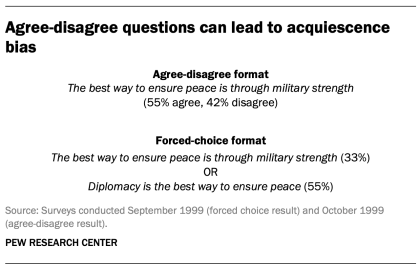

In general, researchable questions must be open ended, suggesting multiple directions and possibilities (Freeman 1998; Hubbard & Power 2003). This means avoiding yes-or-no questions and questions that have clear boundaries or solutions. In contrast, questions that begin with how or what allow a researcher to describe the process and changes as they emerge. They are questions that are most likely to be addressed through observation and documentation that will yield rich descriptions and more detailed and meaningful information. As much as possible, researchable questions are phrased in ways that direct the questioner toward inquiry and away from specific courses of action (Freeman 1998). Researchable questions

- Are always open ended

- Are investigative

- Seek possibilities and multiple responses

- Enable surprises and epiphanies

- Assume that knowledge and understanding are constructed

- Draw out experiences, perspectives, and beliefs

- Involve emotion as well as thought

The more personally meaningful and urgent the questions are, the more likely the teacher has the desire and motivation to address them. As stated previously, the teacher must care about the questions—inquiry demands an orientation toward what matters. Furthermore, questions that can evolve with time and with continued observation and reflection produce the most useful information and results. The teacher can act upon the information and results to make changes and improvements.

Here are some examples of researchable questions:

- How can I become more self-aware regarding my feelings and how they affect my interactions and relationships with children?

- What can I do to prepare myself emotionally when I am not feeling my best?

- How do children react when I use praise? What do children learn from this?

- How does the lack of recess time affect learning in the classroom?

- What kinds of learning activities promote positive interactions among peers?

In sum, researchable questions have the power to change us, and they lend themselves to documentation of those changes. They lead to surprises and epiphanies and help teachers develop greater self-awareness and understanding and more meaningful ways to teach. Thus, the benefits of teacher research begin with finding and enjoying the possibilities in the questions themselves.

Getting started

Getting started can be surprisingly challenging. As a teacher educator, I have found that teachers experience the most difficulty developing researchable questions. Stringer (2004) points out that one of the reasons teachers have such difficulty is that classrooms are highly complicated places involving complex interactions and an interplay of actions and perceptions that are not easily examined without ample time to carefully observe and reflect on classroom situations and problems. Therefore, to clarify the nature and purpose of their research, teachers need time to focus on what happens in the classroom and to reflect on what they do and why they do it. One of the major strengths of teacher research is that it allows teachers to reflect on issues and problems and to formulate tentative questions that may be refined and reframed throughout the research process.

I encourage teachers to keep a journal, record their observations, reflect on their wonderings, and take the time needed to frame meaningful research questions. In addition, I advise teachers to revisit, refocus, and reframe their questions as new evidence and insights emerge. Although many teachers balk at the idea of keeping a reflective journal, it is still one of the best ways to keep track of meaningful questions.

I recommend writing down the questions that arise from teachers’ interactions and encounters (e.g., “What am I observing, assuming, wondering about, or puzzling over?”) rather than writing down everything that happens during the day. Recording these questions makes the next step of reflective practice a lot easier; that is, listing all the questions wondered about over the course of a week, then reflecting on why they were important.

At this point, it does not matter how researchable the questions may be; what is important is to get them down on paper in one’s own words. Teachers who use their journals to record their meaningful questions find it easier to keep journals as part of their everyday reflective practice and to settle on a question they feel comfortable pursuing (MacLean & Mohr 1999).

The next step is to recast the questions to make them more researchable. I have found that using a “free write” activity developed by Marian Mohr (see MacLean & Mohr 1999) helps teacher researchers to write their questions in several different ways and then revisit them. In addition, I believe it is critical to share questions with others. Having a critical friend or an inquiry group that includes colleagues, collaborators, and students is essential to the inquiry process because they help the teacher researchers to rethink and reexamine questions through collective dialogue and reflection, thus enabling them to recast the questions and their subsequent research plans.

In teacher research, the focus is largely on events and experiences and how teachers interpret them rather than on factual information or the development of causal connections explaining why something occurs (Stringer 2004). A teacher researcher starts not necessarily with a hypothesis to test, but with a question that is rooted in subjective experience and motivated by a desire to better understand events and behaviors and to act on this understanding to yield practical results that are immediately applicable to a specific problem (Noffke 1997). Therefore, it is helpful to focus initially on perceptions when reframing original questions to make them researchable.

I typically encourage teachers to explore how they and the children think and feel about what they are doing in the classroom. This perspective orients teachers’ questions toward the ways they experience and perceive particular problems or situations and their interpretations of them. For example, when a public school made scheduling changes that limited children’s recess time in order to have more time to focus on instruction, a second-grade teacher was interested in pursuing this question: “What happens to learning when children are deprived of outdoor recess?”

To make this question more researchable, I suggested that the teacher think about this from her point of view: “How does the lack of recess time contribute to learning in the classroom?” I also recommended that she focus on the children’s perspective and reframe the question: “How do children feel about recess?”—specifically, “What benefits do they perceive recess offers them?” Because her questions did not allow her to observe and compare students who have recess with those who do not, she could not make any conclusive statements; she could, however, get at perceptions and understandings that could lead to some important decisions (and in fact did, as the school returned to its original recess schedule).

Throughout any teacher research project, the initial research question is modified continually to create a closer fit with the classroom environment. Consider this interaction I had with a teacher who was struggling with reframing her question to be more researchable:

After weeks of observing her classroom and reflecting in her journal, Meredith has been wondering why her third-grade students seem so uninspired and uninterested in reading. Her initial question was, “In what ways can I best help students become inspired about learning? In particular, they seem to lack any desire to read in class.”

My response to Meredith was the following: “Meredith, you make some assumptions here about student desire and motivation. Are these accurate? How might your question be reframed to find out? It seems as though you may have a few questions here: ‘How can I help motivate students to learn?,’ ‘Why do students feel uninspired?,’ and ‘Why do students have a lack of motivation to succeed or do well?’

“Alternatively, you might ask, ‘What kinds of activities motivate students to learn?’ In researching this question, you would be able to explore student perceptions and observe what does seem to motivate them. For example, if hands-on, exploratory activities are fun and challenging but math worksheets aren’t, why is that? How are the activities different and how are they perceived?”

Meredith began her inquiry with casual observation and moved toward more systematic, intentional observation, using her reflective teaching journal to record her reactions to questions like “What am I noticing that makes me think these children are unmotivated?” and “Why does this trouble me?” Meredith noted that the more she observed and reflected, the more she became adept at documenting what she heard and saw. Eventually she settled on the question “How do students’ feelings about particular activities affect their motivation to learn?” This question did not yield specific, generalizable strategies that would work for every teacher in every classroom; however, it enabled Meredith to develop greater self-awareness and self-understanding and more meaningful ways to teach the children in her classroom.

It takes practice, self-monitoring, and awareness to become proficient in asking researchable questions. The support and encouragement of an inquiry group and the willingness to give thoughtful consideration to one’s questions are essential. As data collection proceeds, it may be necessary to ask yourself, “Is there something else more interesting emerging from my data?” Therefore, I recommend that teacher researchers, along with their inquiry groups, conduct a regular review of their research questions by asking questions like the following:

- What do the data tell me about my question?

- Am I asking the right question?

- What other questions may be emerging from my data?

- Is my question still meaningful, intriguing, worthy of investigation?

- Is my question more complicated than I had previously thought?

- Can my question evolve with time and with continued observation and reflection?

Framing questions to be researchable makes doing research possible in the midst of teaching and helps teachers stay attuned to the flow of the classroom and the needs of the children. Opportunities and time to revisit or look again are essential to refocusing and reframing questions, rethinking assumptions, and becoming attentive to what is happening in the classroom as new evidence and insights emerge.

Summary

All teachers are questioners. They ask questions of children for various reasons, yet not all questions lead to genuine inquiry by children or by teachers. Questions that lead to inquiry evoke a sense of wonder or puzzlement. Teachers oriented toward understanding and enhancing their practice through inquiry ask meaningful questions—worthy questions that enable them to pursue what interests them about their teaching and to address the problems and concerns that they confront daily in the classroom. Thinking from this perspective, teacher research is not an “add on” but a way to build theory through reflection, inquiry, and action, based on the specific circumstances of the classrooms. It is a way to make informed decisions based on data collected from meaningful inquiry.

Here, I have addressed ways to help teachers move from teaching questions to researchable questions. Posing a researchable question is often viewed as the most challenging aspect of doing teacher research; however, when teaching is viewed as an ongoing process of inquiry involving observation and reflection, then questioning becomes increasingly a tool for exploring assumptions, informing decisions, and changing (improving) what teachers do. In other words, teaching becomes a matter of living and loving the questions.

Clifford, P., & S.J. Marinucci. 2008. “Voices Inside Schools: Testing the Waters: Three Elements of Classroom Inquiry.” Harvard Educational Review 78 (4): 675–88.

Freeman, D. 1998. Doing Teacher Research: From Inquiry to Understanding. Teachersource series. New York: Heinle & Heinle.

Hubbard, R.S., & B.M. Power. 2003. The Art of Classroom Inquiry: A Handbook for Teacher-Researchers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

MacLean, M.S., & M.M. Mohr. 1999. Teacher Researchers at Work. Berkeley, CA: National Writing Project.

Noffke, S.E. 1997. “Professional, Personal, and Political Dimensions of Action Research.” Chap. 6 in Review of Educational Research, vol. 22, 305–43. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Stringer, E. 2007. Action Research in Education . 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Andrew Stremmel is professor in Teaching, Learning and Leadership at South Dakota State University. His scholarship focuses on teacher action research and Reggio Emilia-inspired, inquiry-based approaches. He is an executive editor of Voices of Practitioners. [email protected]

Vol. 13, No. 1

Print this article

Educational Leadership - Ed.D. and Ph.D.

- Developing a Research Question

When you need to develop a research question, you want to ask yourself: what do you want to know about a topic? Additionally, you'll want to determine:

- WHO you are researching,

- WHAT you are researching,

- WHEN your research topic takes place,

- WHERE your research topic takes place, and

- WHY you are researching this topic.

Try these steps to formulate a research question:

Check out these links and the video below for more information:

- How to Write a Research Question

- Writing a Good Research Question

Have Questions? Browse all our FAQs or ask a librarian by chat or email at [email protected] !

- << Previous: What is a Research Question?

- Next: Example Research Questions >>

What are Examples of Research Questions?

What are examples of research questions? This article lists 8 illustrative examples of research questions.

Table of Contents

Introduction.

Well-written research questions determine how the entire research process will proceed.

To effectively write the statement of your thesis’s problem, you will need to remember certain principles that will guide you in framing those critical questions.

This article features some examples of research questions.

There are already many literature pieces written on how to write the research questions required to investigate a phenomenon. But how are the research questions framed in actual situations? How do you write the research questions?

The intention of the research activity should guide all research activities. Once this is clearly defined, the research has three primary outcomes.

The next sections discuss these three principles of framing research questions in more detail.

Intention of Writing Research Questions

You will need to remember specific rules and principles on how to go about writing the research questions. Before you write the research questions, discern what you intend to arrive at in your research.

What are your aims, and what are your expected research outcomes? Do you intend to describe something, determine differences, or explain the causes of a phenomenon?

Research has at least three essential research outcomes. These are described below, along with examples of research questions for each outcome.

Three Primary Research Outcomes

In quantitative research , there are at least three basic research outcomes that will arise in writing the research questions. These are

- come up with a description,

- determine differences between variables, and

- find out correlations between variables.

Research Outcome Number 1. Come up with a description.

The outcome of your research question may be as a description. The description contextualizes the situation, explains something about the subjects or respondents of the study. It also provides the reader with an overview of your research.

For instance, the school administrator might want to study a group of teachers in a school to help improve the school’s performance in the licensure examinations. The school has been lagging in their ranking and there is a need to identify training needs to make the teachers more effective.

Specifically, the administrator would like to find out the composition of teachers in that school, find out how much time they spend in preparing their lessons, and what teaching styles they use in managing the teaching-learning process.

Below are examples of research questions for Research Outcome Number 1 on research about this hypothetical study.

3 Examples of Research Questions That Entail Description

- What is the demographic profile of the teachers in terms of age, gender, educational attainment, civil status, and number of training attended?

- How much time do teachers devote to preparing their lessons?

- What teaching styles are used by teachers in managing their students?

The expected outcomes of the example research questions above will be a description of the teachers’ demographic profile, a range of time devoted to preparing their lessons, and a description of the teachers’ teaching styles .

These research outcomes show tables and graphs with accompanying highlights of the findings. Highlights are those interesting trends or dramatic results that need attention, such as very few training provided to teachers.

Armed with information derived from such research, the administrator can then undertake measures to enhance the teachers’ performance. A hit-and-miss approach is avoided. Thus, the intervention becomes more effective than issuing memos to correct the situation without systematic study.

Research Outcome Number 2. Determine differences between variables.

To write research questions that integrate the variables of the study, you should be able to define what is a variable. If this term is already quite familiar to you, and you are confident in your understanding, you may read the rest of this post.

Check this out : What are examples of variables in research ?

For example, you might want to find out the differences between groups in a selected variable in your study. Say you would like to know if there is a significant difference in long quiz scores (the variable you are interested in) between students who study at night and students who study early in the morning.

You may frame your research questions thus:

2 Examples of Research Questions to Determine Difference

Non-directional.

- Is there a significant difference in long quiz score between students who study early in the morning and students who study at night?

Directional

- Are the quiz scores of students who study early in the morning higher than those who study at night?

The first example research question intends to determine if a difference exists in long quiz scores between students who study at night and those who study early in the morning, hence are non-directional. The aim is just to find out if there is a significant difference. A two-tailed t-test will show if a difference exists.

The second research question aims to determine if students who study in the morning have better quiz scores than what the literature review suggests. Thus, the latter is directional.

Research Outcome Number 3 . Find out correlations or relationships between variables.

The outcome of research questions in this category will be to explain correlations or causality. Below are examples of research questions that aim to determine correlations or relationships between variables using a combination of the variables mentioned in research outcome numbers 1 and 2.

3 Examples of Research Questions That Imply Correlation Analysis

- Is there a significant relationship between teaching style and the long quiz score of students?

- Is there a significant association between the student’s long quiz score and the teacher’s age, gender, and training attended?

- Is there a relationship between the long quiz score and the number of hours devoted by students in studying their lessons?

Note that in all the preceding examples of research questions, the conceptual framework integrates the study variables. Therefore, research questions must always incorporate the variables in them so that the researcher can describe, find differences, or correlate them with each other.

Be more familiar with the conceptual framework : Conceptual Framework: A Step-by-Step Guide on How to Make One

If you find this helpful, take the time to share this with your peers to discover new and exciting things along with their fields of interest.

© 2012 October 22 P. A. Regoniel; Updated 01/11/24

Related Posts

Research Topics on Education: Four Child-Centered Examples

5 tips on how to make a mind map for research purposes, researcher’s euphoria: discovering something new, about the author, patrick regoniel.

Dr. Regoniel, a faculty member of the graduate school, served as consultant to various environmental research and development projects covering issues and concerns on climate change, coral reef resources and management, economic valuation of environmental and natural resources, mining, and waste management and pollution. He has extensive experience on applied statistics, systems modelling and analysis, an avid practitioner of LaTeX, and a multidisciplinary web developer. He leverages pioneering AI-powered content creation tools to produce unique and comprehensive articles in this website.

145 Comments

My topic is “The high failure rates in an education course among first-year students enrolled in the Bachelor of Education programme in Fiji University”.Please I need help with three research questions and three hypothesis…

My topic: impact of educational facilities on the academic performance of students Please I need help with three research questions and three hypothesis…

404 Not found

Qualitative Research Questions: Gain Powerful Insights + 25 Examples

We review the basics of qualitative research questions, including their key components, how to craft them effectively, & 25 example questions.

Einstein was many things—a physicist, a philosopher, and, undoubtedly, a mastermind. He also had an incredible way with words. His quote, "Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted," is particularly poignant when it comes to research.

Some inquiries call for a quantitative approach, for counting and measuring data in order to arrive at general conclusions. Other investigations, like qualitative research, rely on deep exploration and understanding of individual cases in order to develop a greater understanding of the whole. That’s what we’re going to focus on today.

Qualitative research questions focus on the "how" and "why" of things, rather than the "what". They ask about people's experiences and perceptions , and can be used to explore a wide range of topics.

The following article will discuss the basics of qualitative research questions, including their key components, and how to craft them effectively. You'll also find 25 examples of effective qualitative research questions you can use as inspiration for your own studies.

Let’s get started!

What are qualitative research questions, and when are they used?

When researchers set out to conduct a study on a certain topic, their research is chiefly directed by an overarching question . This question provides focus for the study and helps determine what kind of data will be collected.

By starting with a question, we gain parameters and objectives for our line of research. What are we studying? For what purpose? How will we know when we’ve achieved our goals?

Of course, some of these questions can be described as quantitative in nature. When a research question is quantitative, it usually seeks to measure or calculate something in a systematic way.

For example:

- How many people in our town use the library?

- What is the average income of families in our city?

- How much does the average person weigh?

Other research questions, however—and the ones we will be focusing on in this article—are qualitative in nature. Qualitative research questions are open-ended and seek to explore a given topic in-depth.

According to the Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry , “Qualitative research aims to address questions concerned with developing an understanding of the meaning and experience dimensions of humans’ lives and social worlds.”

This type of research can be used to gain a better understanding of people’s thoughts, feelings and experiences by “addressing questions beyond ‘what works’, towards ‘what works for whom when, how and why, and focusing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation,” states one paper in Neurological Research and Practice .

Qualitative questions often produce rich data that can help researchers develop hypotheses for further quantitative study.

- What are people’s thoughts on the new library?

- How does it feel to be a first-generation student at our school?

- How do people feel about the changes taking place in our town?

As stated by a paper in Human Reproduction , “...‘qualitative’ methods are used to answer questions about experience, meaning, and perspective, most often from the standpoint of the participant. These data are usually not amenable to counting or measuring.”

Both quantitative and qualitative questions have their uses; in fact, they often complement each other. A well-designed research study will include a mix of both types of questions in order to gain a fuller understanding of the topic at hand.

If you would like to recruit unlimited participants for qualitative research for free and only pay for the interview you conduct, try using Respondent today.

Crafting qualitative research questions for powerful insights

Now that we have a basic understanding of what qualitative research questions are and when they are used, let’s take a look at how you can begin crafting your own.

According to a study in the International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, there is a certain process researchers should follow when crafting their questions, which we’ll explore in more depth.

1. Beginning the process

Start with a point of interest or curiosity, and pose a draft question or ‘self-question’. What do you want to know about the topic at hand? What is your specific curiosity? You may find it helpful to begin by writing several questions.

For example, if you’re interested in understanding how your customer base feels about a recent change to your product, you might ask:

- What made you decide to try the new product?

- How do you feel about the change?

- What do you think of the new design/functionality?

- What benefits do you see in the change?

2. Create one overarching, guiding question

At this point, narrow down the draft questions into one specific question. “Sometimes, these broader research questions are not stated as questions, but rather as goals for the study.”

As an example of this, you might narrow down these three questions:

into the following question:

- What are our customers’ thoughts on the recent change to our product?

3. Theoretical framing

As you read the relevant literature and apply theory to your research, the question should be altered to achieve better outcomes. Experts agree that pursuing a qualitative line of inquiry should open up the possibility for questioning your original theories and altering the conceptual framework with which the research began.

If we continue with the current example, it’s possible you may uncover new data that informs your research and changes your question. For instance, you may discover that customers’ feelings about the change are not just a reaction to the change itself, but also to how it was implemented. In this case, your question would need to reflect this new information:

- How did customers react to the process of the change, as well as the change itself?

4. Ethical considerations

A study in the International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education stresses that ethics are “a central issue when a researcher proposes to study the lives of others, especially marginalized populations.” Consider how your question or inquiry will affect the people it relates to—their lives and their safety. Shape your question to avoid physical, emotional, or mental upset for the focus group.

In analyzing your question from this perspective, if you feel that it may cause harm, you should consider changing the question or ending your research project. Perhaps you’ve discovered that your question encourages harmful or invasive questioning, in which case you should reformulate it.

5. Writing the question

The actual process of writing the question comes only after considering the above points. The purpose of crafting your research questions is to delve into what your study is specifically about” Remember that qualitative research questions are not trying to find the cause of an effect, but rather to explore the effect itself.

Your questions should be clear, concise, and understandable to those outside of your field. In addition, they should generate rich data. The questions you choose will also depend on the type of research you are conducting:

- If you’re doing a phenomenological study, your questions might be open-ended, in order to allow participants to share their experiences in their own words.

- If you’re doing a grounded-theory study, your questions might be focused on generating a list of categories or themes.

- If you’re doing ethnography, your questions might be about understanding the culture you’re studying.

Whenyou have well-written questions, it is much easier to develop your research design and collect data that accurately reflects your inquiry.

In writing your questions, it may help you to refer to this simple flowchart process for constructing questions:

Download Free E-Book

25 examples of expertly crafted qualitative research questions

It's easy enough to cover the theory of writing a qualitative research question, but sometimes it's best if you can see the process in practice. In this section, we'll list 25 examples of B2B and B2C-related qualitative questions.

Let's begin with five questions. We'll show you the question, explain why it's considered qualitative, and then give you an example of how it can be used in research.

1. What is the customer's perception of our company's brand?

Qualitative research questions are often open-ended and invite respondents to share their thoughts and feelings on a subject. This question is qualitative because it seeks customer feedback on the company's brand.

This question can be used in research to understand how customers feel about the company's branding, what they like and don't like about it, and whether they would recommend it to others.

2. Why do customers buy our product?

This question is also qualitative because it seeks to understand the customer's motivations for purchasing a product. It can be used in research to identify the reasons customers buy a certain product, what needs or desires the product fulfills for them, and how they feel about the purchase after using the product.

3. How do our customers interact with our products?

Again, this question is qualitative because it seeks to understand customer behavior. In this case, it can be used in research to see how customers use the product, how they interact with it, and what emotions or thoughts the product evokes in them.

4. What are our customers' biggest frustrations with our products?

By seeking to understand customer frustrations, this question is qualitative and can provide valuable insights. It can be used in research to help identify areas in which the company needs to make improvements with its products.

5. How do our customers feel about our customer service?

Rather than asking why customers like or dislike something, this question asks how they feel. This qualitative question can provide insights into customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction with a company.

This type of question can be used in research to understand what customers think of the company's customer service and whether they feel it meets their needs.

20 more examples to refer to when writing your question

Now that you’re aware of what makes certain questions qualitative, let's move into 20 more examples of qualitative research questions:

- How do your customers react when updates are made to your app interface?

- How do customers feel when they complete their purchase through your ecommerce site?

- What are your customers' main frustrations with your service?

- How do people feel about the quality of your products compared to those of your competitors?

- What motivates customers to refer their friends and family members to your product or service?

- What are the main benefits your customers receive from using your product or service?

- How do people feel when they finish a purchase on your website?

- What are the main motivations behind customer loyalty to your brand?

- How does your app make people feel emotionally?

- For younger generations using your app, how does it make them feel about themselves?

- What reputation do people associate with your brand?

- How inclusive do people find your app?

- In what ways are your customers' experiences unique to them?

- What are the main areas of improvement your customers would like to see in your product or service?

- How do people feel about their interactions with your tech team?

- What are the top five reasons people use your online marketplace?

- How does using your app make people feel in terms of connectedness?

- What emotions do people experience when they're using your product or service?

- Aside from the features of your product, what else about it attracts customers?

- How does your company culture make people feel?

As you can see, these kinds of questions are completely open-ended. In a way, they allow the research and discoveries made along the way to direct the research. The questions are merely a starting point from which to explore.

This video offers tips on how to write good qualitative research questions, produced by Qualitative Research Expert, Kimberly Baker.

Wrap-up: crafting your own qualitative research questions.

Over the course of this article, we've explored what qualitative research questions are, why they matter, and how they should be written. Hopefully you now have a clear understanding of how to craft your own.

Remember, qualitative research questions should always be designed to explore a certain experience or phenomena in-depth, in order to generate powerful insights. As you write your questions, be sure to keep the following in mind:

- Are you being inclusive of all relevant perspectives?

- Are your questions specific enough to generate clear answers?

- Will your questions allow for an in-depth exploration of the topic at hand?

- Do the questions reflect your research goals and objectives?

If you can answer "yes" to all of the questions above, and you've followed the tips for writing qualitative research questions we shared in this article, then you're well on your way to crafting powerful queries that will yield valuable insights.

Download Free E-Book

.png?width=2500&name=Respondent_100+Questions_Banners_1200x644%20(1).png)

Asking the right questions in the right way is the key to research success. That’s true for not just the discussion guide but for every step of a research project. Following are 100+ questions that will take you from defining your research objective through screening and participant discussions.

Fill out the form below to access free e-book!

Recommend Resources:

- How to Recruit Participants for Qualitative Research

- The Best UX Research Tools of 2022

- 10 Smart Tips for Conducting Better User Interviews

- 50 Powerful Questions You Should Ask In Your Next User Interview

- How To Find Participants For User Research: 13 Ways To Make It Happen

- UX Diary Study: 5 Essential Tips For Conducing Better Studies

- User Testing Recruitment: 10 Smart Tips To Find Participants Fast

- Qualitative Research Questions: Gain Powerful Insights + 25

- How To Successfully Recruit Participants for A Study (2022 Edition)

- How To Properly Recruit Focus Group Participants (2022 Edition)

- The Best Unmoderated Usability Testing Tools of 2022

50 Powerful User Interview Questions You Should Consider Asking

We researched the best user interview questions you can use for your qualitative research studies. Use these 50 sample questions for your next...

How To Unleash Your Extra Income Potential With Respondent

The number one question we get from new participants is “how can I get invited to participate in more projects.” In this article, we’ll discuss a few...

Understanding Why High-Quality Research Needs High-Quality Participants

Why are high-quality participants essential to your research? Read here to find out who they are, why you need them, and how to find them.

Advertisement

Posing Researchable Questions in Mathematics and Science Education: Purposefully Questioning the Questions for Investigation

- Published: 07 April 2020

- Volume 18 , pages 1–7, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Jinfa Cai 1 &

- Rachel Mamlok-Naaman 2

5536 Accesses

8 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 15 May 2020

This article has been updated

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Perhaps the most obvious example is the set of 23 influential mathematical problems posed by David Hilbert that inspired a great deal of progress in the discipline of mathematics (Hilbert, 1901 -1902). Einstein and Infeld ( 1938 ) claimed that “to raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old problems from a new angle, requires creative imagination and marks real advance in science” (p. 95). Both Cantor and Klamkin recommended that, in mathematics, the art of posing a question be held as high or higher in value than solving it. Similarly, in the history of science, formulating precise, answerable questions not only advances new discoveries but also gives scientists intellectual excitement (Kennedy, 2005 ; Mosteller, 1980 ).

In research related to mathematics and science education, there is no shortage of evidence for the impact of posing important and researchable questions: Posing new, researchable questions marks real advances in mathematics and science education (Cai et al., 2019a ). Although research in mathematics and science education begins with researchable questions, only recently have researchers begun to purposefully and systematically discuss the nature of researchable questions. To conduct research, we must have researchable questions, but what defines a researchable question? What are the sources of researchable questions? How can we purposefully discuss researchable questions?

This special issue marks effort for the field’s discussion of researchable questions. As the field of mathematics and science education matures, it is necessary to reflect on the field at such a metalevel (Inglis & Foster, 2018 ). Although the authors in this special issue discuss researchable questions from different angles, they all refer to researchable questions as those that can be investigated empirically. For any empirical study, one can discuss its design, its conduct, and how it can be written up for publication. Therefore, researchable questions in mathematics and science education can be discussed with respect to study design, the conduct of research, and the dissemination of that research.

Even though there are many lines of inquiry that we can explore with respect to researchable questions, each exploring the topic from a different angle, we have decided to focus on the following three aspects to introduce this special issue: (1) criteria for selecting researchable questions, (2) sources of researchable questions, and (3) alignment of researchable questions with the conceptual framework as well as appropriate research methods.

Criteria for Selecting Researchable Questions

It is clear that not all researchable questions are worth the effort to investigate. According to Cai et al. ( 2020 ), of all researchable questions in mathematics and science education, priority is given to those that are significant. Research questions are significant if they can advance the fields’ knowledge and understanding about the teaching and learning of science and mathematics. Through an analysis of peer reviews for a research journal, Cai et al. ( 2020 ) provide a window into the field’s frontiers related to significant researchable questions. In an earlier article, Cai et al. ( 2019a ) argued that

The significance of a research question cannot be determined just by reading it. Rather, its significance stands in relation to the knowledge of the field. The justification for the research question itself—why it is a significant question to investigate—must therefore be made clear through an explicit argument that ties the research question to what is and is not already known. (p. 118)

In their analysis, Cai et al. ( 2020 ) provide evidence that many reviews that highlighted issues with the research questions in rejected manuscripts specifically called for authors to make an argument to motivate the research questions, whereas none of the manuscripts that were ultimately accepted (pending revisions) received this kind of comment. Cai et al. ( 2020 ) provide a framework not only for analyzing peer reviews about research questions but also for how to communicate researchable questions in journal manuscript preparations.

Whereas Cai and his colleagues, as editors of a journal, discuss significant research questions from the perspective of peer review and publication, King, Ochsendorf, Solomon, and Sloane ( 2020 ), as program directors at the Directorate for Education and Human Resources at the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), discuss fundable research questions for research in mathematics and science education. King et al. ( 2020 ) situate their discussion of fundable research questions in the context of writing successful educational research grant proposals. For them, fundable research questions must be transformative and significant with specific and clear constructs. In addition, they present examples of STEM education research questions from different types of research (Institute of Education Sciences [IES] & NSF, 2013 ) and how the questions themselves direct specific design choices, methodologies, measures, study samples, and analytical models as well as how they can reflect the disciplinary orientations of the researchers.

Hjalmarson and Baker ( 2020 ) take a quite different approach to discussing researchable questions for teacher professional development. They argue for the need to include mathematics specialists (e.g. mathematics coaches or mathematics teacher leaders) for studying teacher learning and development. To Hjalmarson and Baker ( 2020 ), researchable questions related to teacher professional learning should be selected by including mathematics specialists because of their role in connecting research and practice.

Sanchez ( 2020 ) discuss, in particular, the importance of replication studies in mathematics and the kinds of researchable questions that would be productive to explore within this category. With the increased acknowledgement of the importance of replication studies (Cai et al., 2018 ), Sanchez Aguilar has provided a useful typology of fundamental questions that can guide a replication study in mathematics (and science) education.

Schoenfeld ( 2020 ) is very direct in suggesting that researchable questions must advance the field and that these research questions must be meaningful and generative: “What is meant by meaningful is that the answer to the questions posed should matter to either practice or theory in some important way. What is meant by generative is that working on the problem, whether it is ‘solved’ or not, is likely to provide valuable insights” (pp. XX). Schoenfeld calls for researchers to establish research programs—that is, one not only selects meaningful research questions to investigate but also continues in that area of research to produce ongoing insights and further meaningful questions.

Stylianides and Stylianides ( 2020 ) argue that, collectively, researchers can and need to pose new researchable questions. The new researchable questions are worth investigating if they reflect the field’s growing understanding of the web of potentially influential factors surrounding the investigation of a particular area. The argument that Stylianides and Stylianides ( 2020 ) use is very similar to Schoenfeld’s ( 2020 ) generative criteria, but Stylianides and Stylianides ( 2020 ) explicitly emphasize the collective nature of the field’s growing understanding of a particular phenomenon.

Sources of Researchable Questions

Research questions in science and mathematics education arise from multiple sources, including problems of practice, extensions of theory, and lacunae in existing areas of research. Therefore, through a research question’s connections to prior research, it should be clear how answering the question extends the field’s knowledge (Cai et al., 2019a ). Across the papers in this special issue lies a common theme that researchable questions arise from understanding the area under study. Cai et al. ( 2020 ) take the position that the significance of researchable questions must be justified in the context of prior research. In particular, reviewers of manuscripts submitted for publication will evaluate if the study is adequately motivated. In fact, posing significant researchable questions is an iterative process beginning with some broader, general sense of an idea which is potentially fruitful and leading, eventually, to a well-specified, stated research question (Cai et al., 2019a ). Similarly, King et al. ( 2020 ) argue that fundable research questions should be grounded in prior research and make explicit connections to what is known or not known in the given area of study.

Sanchez ( 2020 ) suggest that it is time for the field of mathematics and science education research to seriously consider replication studies. Researchable questions related to replication studies might arise from the examination of the following two questions: (1) Do the results of the original study hold true beyond the context in which it was developed? (2) Are there alternative ways to study and explain an identified phenomenon or finding? Similarly, Hjalmarson and Baker ( 2020 ) specifically suggest two needs related to mathematics specialists in studies of professional development that drive researchable questions: (1) defining practices and hidden players involved in systematic school change and (2) identifying the unit of analysis and scaling up professional development.

Schoenfeld ( 2020 ) uses various examples to illustrate the origin of researchable questions. One of his (perhaps most familiar) examples is his decade-long research on mathematical problem solving. He elaborates on how answering one specific research question leads to another and another. In the context of research on mathematical proof, Stylianides and Stylianides ( 2020 ) also illustrate how researchable questions arise from existing research in the area leading to new researchable questions in the dynamic process of educational research. The arguments and examples in both Schoenfeld ( 2020 ) and Stylianides and Stylianides ( 2020 ) are quite powerful in the sense that this source of researchable questions facilitates the accumulation of knowledge for the given areas of study.

A related source of researchable questions is not discussed in this set of papers—unexpected findings. A potentially powerful source of research questions is the discovery of an unexpected finding when conducting research (Cai et al., 2019b ). Many important advances in scientific research have their origins in serendipitous, unexpected findings. Researchers are often faced with unexpected and perhaps surprising results, even when they have developed a carefully crafted theoretical framework, posed research questions tightly connected to this framework, presented hypotheses about expected outcomes, and selected methods that should help answer the research questions. Indeed, unexpected findings can be the most interesting and valuable products of the study and a source of further researchable questions (Cai et al., 2019b ).

Of course, researchable questions can also arise from established scholars in a given field—those who are most familiar with the scope of the research that has been done. For example, in 2005, in celebrating the 125th anniversary of the publication of Science ’s first issue, the journal invited researchers from around the world to propose the 125 most important research questions in the scientific enterprise (Kennedy, 2005 ). A list of unanswered questions like this is a great source for researchable questions in science, just as the 23 great questions in mathematics by Hilbert ( 1901 -1902) spurred the field for decades. In mathematics and science education, one can look to research handbooks and compendiums. These volumes often include lists of unanswered research questions in the hopes of prompting further research in various areas (e.g. Cai, 2017 ; Clements, Bishop, Keitel, Kilpatrick, & Leung, 2013 ; Talbot-Smith, 2013 ).

Alignment of Researchable Questions with the Conceptual Framework and Appropriate Research Methods

Cai et al. ( 2020 ) and King et al. ( 2020 ) explicitly discuss the alignment of researchable questions with the conceptual framework and appropriate research methods. In writing journal publications or grant proposals, it is extremely important to justify the significance of the researchable questions based on the chosen theoretical framework and then determine robust methods to answer the research questions. According to Cai et al. ( 2019a ), justification for the significance of the research questions depends on a theoretical framework: “The theoretical framework shapes the researcher’s conception of the phenomenon of interest, provides insight into it, and defines the kinds of questions that can be asked about it” (p. 119). It is true that the notion of a theoretical framework can remain somewhat mysterious and confusing for researchers. However, it is clear that the theoretical framework links research questions to existing knowledge, thus helping to establish their significance; provides guidance and justification for methodological choices; and provides support for the coherence that is needed between research questions, methods, results, and interpretations of findings (Cai & Hwang, 2019 ; Cai et al., 2019c ).

Analyzing reviews for a research journal in mathematics education, Cai et al. ( 2020 ) found that the reviewers wanted manuscripts to be explicit about how the research questions, the theoretical framework, the methods, and the findings were connected. Even for manuscripts that were accepted (pending revisions), making explicit connections across all parts of the manuscript was a challenging proposition. Thus, in preparing manuscripts for publication, it is essential to communicate the significance of a study by developing a coherent chain of justification connecting researchable questions, the theoretical framework, and the research methods chosen to address the research questions.

The Long Journey Has Just Begun with a First Step

As the field of mathematics and science education matures, there is a need to take a step back and reflect on what has been done so that the field can continue to grow. This special issue represents a first step by reflecting on the posing of significant researchable questions to advance research in mathematics and science education. Such reflection is useful and necessary not only for the design of studies but also for the writing of research reports for publication. Most importantly, working on significant researchable questions cannot only contribute to theory generation about the teaching and learning of mathematics and science but also contribute to improving the impact of research on practice in mathematics and science classrooms.

To conclude, we want to draw readers’ attention to a parallel between this reflection on research in our field and a line of research that investigates the development of school students’ problem-posing and questioning skills in mathematics and science (Blonder, Rapp, Mamlok-Naaman, & Hofstein, 2015 ; Cai, Hwang, Jiang, & Silber, 2015 ; Cuccio-Schirripa & Steiner, 2000 ; Hofstein, Navon, Kipnis, & Mamlok-Naaman, 2005 ; Silver, 1994 ; Singer, Ellerton, & Cai, 2015 ). Posing researchable questions is critical for advancing research in mathematics and science education. Similarly, providing students opportunities to pose problems is critical for the development of their thinking and learning. With the first step in this journey made, perhaps we can dream of something bigger further on down the road.

Change history

15 may 2020.

The original version of this article unfortunately contains correction.

Blonder, R., Rapp, S., Mamlok-Naaman, R., & Hofstein, A. (2015). Questioning behavior of students in the inquiry chemistry laboratory: Differences between sectors and genders in the Israeli context. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 13 (4), 705–732.

Google Scholar

Cai, J. (Ed.). (2017). Compendium for research in mathematics education . Reston, VA: National Council for Teachers of Mathematics.

Cai, J., & Hwang, S. (2019). Constructing and employing theoretical frameworks in (mathematics) education research. For the Learning of Mathematics, 39 (3), 45–47.

Cai, J., Hwang, S., Hiebert, J., Hohensee, C., Morris, A., & Robison, V. (2020). Communicating the significance of research questions: Insights from peer review at a flagship journal. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-020-10073-x .

Cai, J., Hwang, S., Jiang, C., & Silber, S. (2015). Problem posing research in mathematics: Some answered and unanswered questions. In F. M. Singer, N. Ellerton, & J. Cai (Eds.), Mathematical problem posing: From research to effective practice (pp. 3–34). New York, NY: Springer.

Cai, J., Morris, A., Hohensee, C., Hwang, S., Robison, V., Cirillo, M., . . . Hiebert, J. (2019a). Posing significant research questions. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education , 50 (2), 114120. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.50.2.0114 .

Cai, J., Morris, A., Hohensee, C., Hwang, S., Robison, V., Cirillo, M., . . . Hiebert, J. (2019b). So what? Justifying conclusions and interpretations of data. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education , 50 (5), 470477. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.50.5.0470 .

Cai, J., Morris, A., Hohensee, C., Hwang, S., Robison, V., Cirillo, M., . . . Hiebert, J. (2019c). Theoretical framing as justifying. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education , 50 (3), 218224. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.50.3.0218 .

Cai, J., Morris, A., Hohensee, C., Hwang, S., Robison, V., & Hiebert, J. (2018). The role of replication studies in educational research. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 49 (1), 2–8. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.49.1.0002 .

Clements, M. A., Bishop, A., Keitel, C., Kilpatrick, J., & Leung, K. S. F. (Eds.). (2013). Third international handbook of mathematics education research . New York, NY: Springer.

Cuccio-Schirripa, S., & Steiner, H. E. (2000). Enhancement and analysis of science question level for middle school students. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37 , 210–224.

Einstein, A., & Infeld, L. (1938). The evolution of physics: The growth of ideas from early concepts to relativity and quanta . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Hilbert, D. (1901-1902). Mathematical problems. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society , 8 , 437–479.

Hjalmarson, M. A., & Baker, C. K. (2020). Mathematics specialists as the hidden players in professional development: Researchable questions and methodological considerations. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-020-10077-7 .

Hofstein, A., Navon, O., Kipnis, M., & Mamlok-Naaman, R. (2005). Developing students ability to ask more and better questions resulting from inquiry-type chemistry laboratories. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42 , 791–806.

Inglis, M., & Foster, C. (2018). Five decades of mathematics education research. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 49 (4), 462–500.

Institute of Education Sciences & National Science Foundation. (2013). Common guidelines for education research and development . Washington, DC: Authors.

Kennedy, D. (2005). Editorial. Science, 310 (5749), 787. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.310.5749.787b .

King, K., Ochsendorf, R. J., Solomon, G. E. A., & Sloane, F. C. (2020). Posing fundable questions in mathematics and science education. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-020-10088-4 .

Mosteller, F. (1980). The next 100 years of science. Science, 209 (4452), 21–23. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7280662 .

Sanchez, M. (2020). Replication studies in mathematics education: What kind of questions would be productive to explore? International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-020-10069-7 .

Schoenfeld, A. (2020). On meaningful, researchable, and generative questions. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-020-10068-8 .

Silver, E. A. (1994). On mathematical problem posing. For the Learning of Mathematics, 14 (1), 19–28.

Singer, F. M., Ellerton, N., & Cai, J. (2015). Mathematical problem posing: From research to effective practice . New York, NY: Springer.

Stylianides, G. J., & Stylianides, A. J. (2020). Posing new researchable questions as a dynamic process in educational research. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-020-10067-9 .

Talbot-Smith, M. (2013). Handbook of research on science education . Waltham, Massachusetts, Focal Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Delaware, Newark, DE, USA

Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel

Rachel Mamlok-Naaman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jinfa Cai .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cai, J., Mamlok-Naaman, R. Posing Researchable Questions in Mathematics and Science Education: Purposefully Questioning the Questions for Investigation. Int J of Sci and Math Educ 18 (Suppl 1), 1–7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-020-10079-5

Download citation

Published : 07 April 2020

Issue Date : May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-020-10079-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Write my thesis

- Thesis writers

- Buy thesis papers

- Bachelor thesis

- Master's thesis

- Thesis editing services

- Thesis proofreading services

- Buy a thesis online

- Write my dissertation

- Dissertation proposal help

- Pay for dissertation

- Custom dissertation

- Dissertation help online

- Buy dissertation online

- Cheap dissertation

- Dissertation editing services

- Write my research paper

- Buy research paper online

- Pay for research paper

- Research paper help

- Order research paper

- Custom research paper

- Cheap research paper

- Research papers for sale

- Thesis subjects

- How It Works

110+ Exceptional Education Research Topics Ideas

Topics for education research usually comprise school research topics, research problems in education, qualitative research topics in education, and concept paper topics about education to mention a few.

If you’re looking for research titles about education, you’re reading the right post! This article contains 110 of the best education research topics that will come in handy when you need to choose one for your research. From sample research topics in education, to research titles examples for high school students about education – we have it all.

Educational Research Topics

Research title examples for college students, quantitative research titles about education, topics related to education for thesis, research titles about school issues, ph.d. research titles in education, elementary education research topics, research title examples about online class, research titles about modular learning, examples of research questions in education, special education research titles.

The best research titles about education must be done through the detailed process of exploring previous works and improving personal knowledge.

Here are some good research topics in education to consider.

What Are Good Research Topics Related to Education?

- The role of Covid-19 in reinvigorating online learning

- The growth of cognitive abilities through leisure experiences

- The merits of group study in education

- Merits and demerits of traditional learning methods

- The impact of homework on traditional and modern education

- Student underdevelopment as a result of larger class volumes

- Advantages of digital textbooks in learning

- The struggle of older generations in computer education

- The standards of learning in the various academic levels

- Bullying and its effects on educational and mental health

- Exceptional education tutors: Is the need for higher pay justifiable?

The following examples of research titles about education for college students are ideal for a project that will take a long duration to complete. Here are some education topics for research that you can consider for your degree.

- Modern classroom difficulties of students and teachers

- Strategies to reform the learning difficulties within schools

- The rising cost of tuition and its burden on middle-class parents

- The concept of creativity among public schools and how it can be harnessed

- Major difficulties experienced in academic staff training

- Evaluating the learning cultures of college students

- Use of scientific development techniques in student learning

- Research of skill development in high school and college students

- Modern grading methods in underdeveloped institutions

- Dissertations and the difficulties surrounding their completion

- Integration of new gender categories in personalized learning

These research topics about education require a direct quantitative analysis and study of major ideas and arguments. They often contain general statistics and figures to back up regular research. Some of such research topics in education include: