Beyond the pages of academic medicine

10 Tips for Reviewing a Qualitative Paper

Editor’s Note: The following post is part of a series of Peer Reviewer Resources written by some of Academic Medicine ‘s top peer reviewers. Read other peer review posts .

By: Carol-anne Moulton, MD, FRACS, MEd, PhD, Department of Surgery, University of Toronto, and Priyanka Patel, MSc, Wilson Center, University Health Network, University of Toronto

This is a tough task. Let us say that off the bat. We have been involved in qualitative research for a long time now and the complexity of it never ceases to amaze us…so there is no “how to” guide that will suit all qualitative research.

Having said that, we think there are some guiding principles that can help us begin to understand the rigor of qualitative research and consequently the review process.

- Question/Purpose : This should be clearly stated, as in all research studies. There are generally no hypotheses statements in qualitative research as we are not testing but rather exploring. Ideally, the questions are framed around how and why type questions, rather than how often, is there a difference, or what are the factors type questions.

- Rationale of study : We like to make sure that the study was built upon a well justified and referenced rationale. It may not be our area of study but we think it is important for the authors to provide rationale for their study by building up the arguments from the literature. Theories or pre-existing frameworks that informed the research question should be described up front. Some work claims to be atheoretical. Traditionally, grounded theorists claimed their work to be atheoretical, but nowadays many grounded theorists are acknowledging being informed by particular perspectives, frameworks, or theories. This should be made explicit.

- Methodology described : What type of research was this? Ethnography? Grounded theory? Phenomenology? Discourse analysis? It’s important that the researchers describe their research journey in a clear and detailed enough way to give the readers an understanding for how the analyses evolved. This should include an explanation of why the methodological approach was used, as well as the key principles from the methodology that guided the study.

- Epistemology : Researchers come from all paradigms and it is important to identify within which paradigm the authors are situated. Sometimes they might state deliberately “We have used constructivist grounded theory,” but it might be a matter of reading between the lines to figure it out. If from the positivist paradigm, authors might use the terms valid or verified to imply they are making statements of truth. The paradigm helps us understand what the authors mean by “truth” and informs how they went about creating knowledge and constructing meaning from their results.

- Context described satisfactorily : Qualitative research is not meant to imply generalizability. In fact, we celebrate the importance of context. We recognize that the phenomena we study are often different in meaningful ways when taken to a different context. For example, the experiences of physicians coping with burnout may be unique based on specialty and/or institution (i.e. type of systems-level support available, differing demands in academic or community institutions). A good qualitative study should therefore describe sufficient details of context (i.e. physical, cultural, social, and/or environmental context) in which the research was conducted to allow the reader to make judgments of whether the results might be transferable to another (possibly their own) setting.

- Data collection and analysis : Do they provide enough information to understand the collection and analysis process? As reviewers, we often ask ourselves whether the data collection and analyses are clear and detailed enough for us to gain a sense of how the analysis of the phenomena evolved. For example, who made up the research team? Because most knowledge is viewed as a co-construction between researcher and participants, each individual (e.g. a sociologist versus a surgeon) will analyze the results differently, but both meaningfully, based on their unique position and perspective.

- Sampling strategies : These are very important to understand whether the question was aligned with the data collection process. The sample reflects the type of results achieved and helps the reader understand from which perspective the data was collected. Some common sampling strategies include theoretical sampling and negative case sampling. Researchers may theoretically sample by selecting participants that in someway inform their understanding of an emergent theme or idea. Negative case sampling may be used to search for instances that may challenge the emergent patterns from the data for the purpose of refining the analysis. Negative case sampling is used to ensure that the researchers are not specifically selecting cases that confirm their findings.

- Analysis elevated beyond description : Results might be descriptive in nature (e.g. “One surgeon felt upset and isolated after he experienced a hernia complication in his first month of independent practice”) or they might be elevated to create more abstract concepts and ideas removed from the primary dataset (e.g. characterizing the phases of surgeons’ reactions to complications). In either case, the researcher should ensure that the way they present their findings are aligned with principles of the methodology used.

- Proof of an iterative process : Qualitative research is usually done in an iterative manner where ideas and concepts are built up over time and occur through cycles of data collection and data analysis. This is demonstrated through statements like “Our interview template was altered over time to reflect the emergent ideas through the analysis process,” or “As we became interested in this concept, we began to sample for…”.

- Reflexivity : This is tough to understand, especially for those of us who come from the positivist paradigm where it is of utmost importance to “prove” that the results are “true” and untainted by bias. The aim of qualitative research is to understand meaning rather than assuming that there is a singular truth or reality. A good qualitative researcher recognizes that the way they make sense of and attach meaning to the data is partly shaped by the characteristics of the researcher (i.e. age, gender, social class, ethnicity, professional status, etc.) and the assumptions they hold. The researcher should make explicit the perspectives they are coming from so that the readers can interpret the data appropriately. Consider a study exploring the pressures surgical trainees experience in residency conducted by a staff surgeon versus a non-surgical anthropologist. You can imagine the findings may differ based on the types of questions the two interviewers decide to ask, what they each find interesting or important, or how comfortable the resident feels discussing sensitive information with an outsider (anthropologist) as opposed to an insider (surgeon). We like to see that a researcher has reflected on how her or his unique position, preconceptions, and biases influenced the findings.

19 thoughts on “ 10 Tips for Reviewing a Qualitative Paper ”

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Nursing Papers 247

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Essay Don

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Assignmentnerds.net

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Academia Essays

Pingback: qualitative review in nursing - Superb Papers

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Allessaysexpert

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Chip Writers

Pingback: Science - Technical Assignments

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing – fastwriting

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing – EssaySolutions.net

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Homework Market

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Midterm Essays

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Tutoring Beast

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - StudyCore

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Custom Nursing Essays

Pingback: qualitative review in nursing - Gradesmine.com

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Master My Course

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Proficient Essay Help

Pingback: Qualitative Review in Nursing - Eliteprofessionalwriters.com

Comments are closed.

Discover more from AM Rounds

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 22, Issue 1

- How to appraise qualitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Calvin Moorley 1 ,

- Xabi Cathala 2

- 1 Nursing Research and Diversity in Care, School of Health and Social Care , London South Bank University , London , UK

- 2 Institute of Vocational Learning , School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Calvin Moorley, Nursing Research and Diversity in Care, School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London SE1 0AA, UK; Moorleyc{at}lsbu.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2018-103044

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

In order to make a decision about implementing evidence into practice, nurses need to be able to critically appraise research. Nurses also have a professional responsibility to maintain up-to-date practice. 1 This paper provides a guide on how to critically appraise a qualitative research paper.

What is qualitative research?

- View inline

Useful terms

Some of the qualitative approaches used in nursing research include grounded theory, phenomenology, ethnography, case study (can lend itself to mixed methods) and narrative analysis. The data collection methods used in qualitative research include in depth interviews, focus groups, observations and stories in the form of diaries or other documents. 3

Authenticity

Title, keywords, authors and abstract.

In a previous paper, we discussed how the title, keywords, authors’ positions and affiliations and abstract can influence the authenticity and readability of quantitative research papers, 4 the same applies to qualitative research. However, other areas such as the purpose of the study and the research question, theoretical and conceptual frameworks, sampling and methodology also need consideration when appraising a qualitative paper.

Purpose and question

The topic under investigation in the study should be guided by a clear research question or a statement of the problem or purpose. An example of a statement can be seen in table 2 . Unlike most quantitative studies, qualitative research does not seek to test a hypothesis. The research statement should be specific to the problem and should be reflected in the design. This will inform the reader of what will be studied and justify the purpose of the study. 5

Example of research question and problem statement

An appropriate literature review should have been conducted and summarised in the paper. It should be linked to the subject, using peer-reviewed primary research which is up to date. We suggest papers with a age limit of 5–8 years excluding original work. The literature review should give the reader a balanced view on what has been written on the subject. It is worth noting that for some qualitative approaches some literature reviews are conducted after the data collection to minimise bias, for example, in grounded theory studies. In phenomenological studies, the review sometimes occurs after the data analysis. If this is the case, the author(s) should make this clear.

Theoretical and conceptual frameworks

Most authors use the terms theoretical and conceptual frameworks interchangeably. Usually, a theoretical framework is used when research is underpinned by one theory that aims to help predict, explain and understand the topic investigated. A theoretical framework is the blueprint that can hold or scaffold a study’s theory. Conceptual frameworks are based on concepts from various theories and findings which help to guide the research. 6 It is the researcher’s understanding of how different variables are connected in the study, for example, the literature review and research question. Theoretical and conceptual frameworks connect the researcher to existing knowledge and these are used in a study to help to explain and understand what is being investigated. A framework is the design or map for a study. When you are appraising a qualitative paper, you should be able to see how the framework helped with (1) providing a rationale and (2) the development of research questions or statements. 7 You should be able to identify how the framework, research question, purpose and literature review all complement each other.

There remains an ongoing debate in relation to what an appropriate sample size should be for a qualitative study. We hold the view that qualitative research does not seek to power and a sample size can be as small as one (eg, a single case study) or any number above one (a grounded theory study) providing that it is appropriate and answers the research problem. Shorten and Moorley 8 explain that three main types of sampling exist in qualitative research: (1) convenience (2) judgement or (3) theoretical. In the paper , the sample size should be stated and a rationale for how it was decided should be clear.

Methodology

Qualitative research encompasses a variety of methods and designs. Based on the chosen method or design, the findings may be reported in a variety of different formats. Table 3 provides the main qualitative approaches used in nursing with a short description.

Different qualitative approaches

The authors should make it clear why they are using a qualitative methodology and the chosen theoretical approach or framework. The paper should provide details of participant inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as recruitment sites where the sample was drawn from, for example, urban, rural, hospital inpatient or community. Methods of data collection should be identified and be appropriate for the research statement/question.

Data collection

Overall there should be a clear trail of data collection. The paper should explain when and how the study was advertised, participants were recruited and consented. it should also state when and where the data collection took place. Data collection methods include interviews, this can be structured or unstructured and in depth one to one or group. 9 Group interviews are often referred to as focus group interviews these are often voice recorded and transcribed verbatim. It should be clear if these were conducted face to face, telephone or any other type of media used. Table 3 includes some data collection methods. Other collection methods not included in table 3 examples are observation, diaries, video recording, photographs, documents or objects (artefacts). The schedule of questions for interview or the protocol for non-interview data collection should be provided, available or discussed in the paper. Some authors may use the term ‘recruitment ended once data saturation was reached’. This simply mean that the researchers were not gaining any new information at subsequent interviews, so they stopped data collection.

The data collection section should include details of the ethical approval gained to carry out the study. For example, the strategies used to gain participants’ consent to take part in the study. The authors should make clear if any ethical issues arose and how these were resolved or managed.

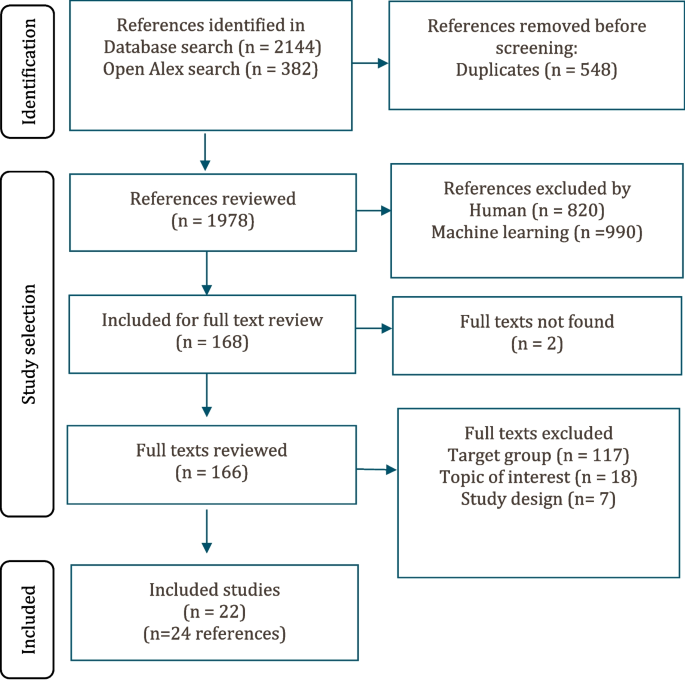

The approach to data analysis (see ref 10 ) needs to be clearly articulated, for example, was there more than one person responsible for analysing the data? How were any discrepancies in findings resolved? An audit trail of how the data were analysed including its management should be documented. If member checking was used this should also be reported. This level of transparency contributes to the trustworthiness and credibility of qualitative research. Some researchers provide a diagram of how they approached data analysis to demonstrate the rigour applied ( figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Example of data analysis diagram.

Validity and rigour

The study’s validity is reliant on the statement of the question/problem, theoretical/conceptual framework, design, method, sample and data analysis. When critiquing qualitative research, these elements will help you to determine the study’s reliability. Noble and Smith 11 explain that validity is the integrity of data methods applied and that findings should accurately reflect the data. Rigour should acknowledge the researcher’s role and involvement as well as any biases. Essentially it should focus on truth value, consistency and neutrality and applicability. 11 The authors should discuss if they used triangulation (see table 2 ) to develop the best possible understanding of the phenomena.

Themes and interpretations and implications for practice

In qualitative research no hypothesis is tested, therefore, there is no specific result. Instead, qualitative findings are often reported in themes based on the data analysed. The findings should be clearly linked to, and reflect, the data. This contributes to the soundness of the research. 11 The researchers should make it clear how they arrived at the interpretations of the findings. The theoretical or conceptual framework used should be discussed aiding the rigour of the study. The implications of the findings need to be made clear and where appropriate their applicability or transferability should be identified. 12

Discussions, recommendations and conclusions

The discussion should relate to the research findings as the authors seek to make connections with the literature reviewed earlier in the paper to contextualise their work. A strong discussion will connect the research aims and objectives to the findings and will be supported with literature if possible. A paper that seeks to influence nursing practice will have a recommendations section for clinical practice and research. A good conclusion will focus on the findings and discussion of the phenomena investigated.

Qualitative research has much to offer nursing and healthcare, in terms of understanding patients’ experience of illness, treatment and recovery, it can also help to understand better areas of healthcare practice. However, it must be done with rigour and this paper provides some guidance for appraising such research. To help you critique a qualitative research paper some guidance is provided in table 4 .

Some guidance for critiquing qualitative research

- ↵ Nursing and Midwifery Council . The code: Standard of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives . 2015 https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf ( accessed 21 Aug 18 ).

- Barrett D ,

- Cathala X ,

- Shorten A ,

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

About Journal

American Journal of Qualitative Research (AJQR) is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal that publishes qualitative research articles from a number of social science disciplines such as psychology, health science, sociology, criminology, education, political science, and administrative studies. The journal is an international and interdisciplinary focus and greatly welcomes papers from all countries. The journal offers an intellectual platform for researchers, practitioners, administrators, and policymakers to contribute and promote qualitative research and analysis.

ISSN: 2576-2141

Call for Papers- American Journal of Qualitative Research

American Journal of Qualitative Research (AJQR) welcomes original research articles and book reviews for its next issue. The AJQR is a quarterly and peer-reviewed journal published in February, May, August, and November.

We are seeking submissions for a forthcoming issue published in February 2024. The paper should be written in professional English. The length of 6000-10000 words is preferred. All manuscripts should be prepared in MS Word format and submitted online: https://www.editorialpark.com/ajqr

For any further information about the journal, please visit its website: https://www.ajqr.org

Submission Deadline: November 15, 2023

Announcement

Dear AJQR Readers,

Due to the high volume of submissions in the American Journal of Qualitative Research , the editorial board decided to publish quarterly since 2023.

Volume 8, Issue 1

Current issue.

Social distancing requirements resulted in many people working from home in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic. The topic of working from home was often discussed in the media and online during the pandemic, but little was known about how quality of life (QOL) and remote working interfaced. The purpose of this study was to describe QOL while working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. The novel topic, unique methodological approach of the General Online Qualitative Study ( D’Abundo & Franco, 2022a), and the strategic Social Distancing Sampling ( D’Abundo & Franco, 2022c) resulted in significant participation throughout the world (n = 709). The United Kingdom subset of participants (n = 234) is the focus of this article. This big qual, large qualitative study (n >100) included the principal investigator-developed, open-ended, online questionnaire entitled the “Quality of Life Home Workplace Questionnaire (QOLHWQ)” and demographic questions. Data were collected peak-pandemic from July to September 2020. Most participants cited increased QOL due to having more time with family/kids/partners/pets, a more comfortable work environment while being at home, and less commuting to work. The most cited issue associated with negative QOL was social isolation. As restrictions have been lifted and public health emergency declarations have been terminated during the post-peak era of the COVID-19 pandemic, the potential for future public health emergencies requiring social distancing still exists. To promote QOL and work-life balance for employees working remotely in the United Kingdom, stakeholders could develop social support networks and create effective planning initiatives to prevent social isolation and maximize the benefits of remote working experiences for both employees and organizations.

Keywords: qualitative research, quality of life, remote work, telework, United Kingdom, work from home.

(no abstract)

This essay reviews classic works on the philosophy of science and contemporary pedagogical guides to scientific inquiry in order to present a discussion of the three logics that underlie qualitative research in political science. The first logic, epistemology, relates to the essence of research as a scientific endeavor and is framed as a debate between positivist and interpretivist orientations within the discipline of political science. The second logic, ontology, relates to the approach that research takes to investigating the empirical world and is framed as a debate between positivist qualitative and quantitative orientations, which together constitute the vast majority of mainstream researchers within the discipline. The third logic, methodology, relates to the means by which research aspires to reach its scientific ends and is framed as a debate among positivist qualitative orientations. Additionally, the essay discusses the present state of qualitative research in the discipline of political science, reviews the various ways in which qualitative research is defined in the relevant literature, addresses the limitations and trade-offs that are inherently associated with the aforementioned logics of qualitative research, explores multimethod approaches to remedying these issues, and proposes avenues for acquiring further information on the topics discussed.

Keywords: qualitative research, epistemology, ontology, methodology

This paper examines the phenomenology of diagnostic crossover in eating disorders, the movement within or between feeding and eating disorder subtypes or diagnoses over time, in two young women who experienced multiple changes in eating disorder diagnosis over 5 years. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis, this study found that transitioning between different diagnostic labels, specifically between bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa binge/purge subtype, was experienced as disempowering, stigmatizing, and unhelpful. The findings in this study offer novel evidence that, from the perspective of individuals diagnosed with EDs, using BMI as an indicator of the presence, severity, or change of an ED may have adverse consequences for well-being and recovery and may lead to mischaracterization or misclassification of health status. The narratives discussed in this paper highlight the need for more person-centered practices in the context of diagnostic crossover. Including the perspectives of those with lived experience can help care providers working with individuals with eating disorders gain an in-depth understanding of the potential personal impact of diagnosis changing and inform discussions around developing person-focused diagnostic practices.

Keywords: feeding and eating disorders, bulimia nervosa, diagnostic labels, diagnostic crossover, illness narrative

Often among the first witnesses to child trauma, educators and therapists are on the frontline of an unfolding and multi-pronged occupational crisis. For educators, lack of support and secondary traumatic stress (STS) appear to be contributing to an epidemic in professional attrition. Similarly, therapists who do not prioritize self-care can feel depleted of energy and optimism. The purpose of this phenomenological study was to examine how bearing witness to the traumatic narratives of children impacts similar helping professionals. The study also sought to extrapolate the similarities and differences between compassion fatigue and secondary trauma across these two disciplines. Exploring the common factors and subjective individual experiences related to occupational stress across these two fields may foster a more complete picture of the delicate nature of working with traumatized children and the importance of successful self-care strategies. Utilizing Constructivist Self-Development Theory (CSDT) and focus group interviews, the study explores the significant risk of STS facing both educators and therapists.

Keywords: qualitative, secondary traumatic stress, self-care, child trauma, educators, therapists.

This study explored the lived experiences of residents of the Gulf Coast in the USA during Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall in August 2005 and caused insurmountable destruction throughout the area. A heuristic process and thematic analysis were employed to draw observations and conclusions about the lived experiences of each participant and make meaning through similar thoughts, feelings, and themes that emerged in the analysis of the data. Six themes emerged: (1) fear, (2) loss, (3) anger, (4) support, (5) spirituality, and (6) resilience. The results of this study allude to the possible psychological outcomes as a result of experiencing a traumatic event and provide an outline of what the psychological experience of trauma might entail. The current research suggests that preparedness and expectation are key to resilience and that people who feel that they have power over their situation fare better than those who do not.

Keywords: mass trauma, resilience, loss, natural disaster, mental health.

Women from rural, low-income backgrounds holding positions within the academy are the exception and not the rule. Most women faculty in the academy are from urban/suburban areas and middle- and upper-income family backgrounds. As women faculty who do not represent this norm, our primary goal with this article is to focus on the unique barriers we experienced as girls from rural, low-income areas in K-12 schools that influenced the possibilities for successfully transitioning to and engaging with higher education. We employed a qualitative duoethnographic and narrative research design to respond to the research questions, and we generated our data through semi-structured, critical, ethnographic dialogic conversations. Our duoethnographic-narrative analyses revealed six major themes: (1) independence and other benefits of having a working-class mom; (2) crashing into middle-class norms and expectations; (3) lucking and falling into college; (4) fish out of water; (5) overcompensating, playing middle class, walking on eggshells, and pushing back; and (6) transitioning from a working-class kid to a working class academic, which we discuss in relation to our own educational attainment.

Keywords: rurality, working-class, educational attainment, duoethnography, higher education, women.

This article draws on the findings of a qualitative study that focused on the perspectives of four Indian American mothers of youth with developmental disabilities on the process of transitioning from school to post-school environments. Data were collected through in-depth ethnographic interviews. The findings indicate that in their efforts to support their youth with developmental disabilities, the mothers themselves navigate multiple transitions across countries, constructs, dreams, systems of schooling, and services. The mothers’ perspectives have to be understood against the larger context of their experiences as citizens of this country as well as members of the South Asian diaspora. The mothers’ views on services, their journey, their dreams for their youth, and their interpretation of the ideas anchored in current conversations on transition are continually evolving. Their attempts to maintain their resilience and their indigenous understandings while simultaneously negotiating their experiences in the United States with supporting their youth are discussed.

Keywords: Indian-American mothers, transitioning, diaspora, disability, dreams.

This study explored the influence of yoga on practitioners’ lives ‘off the mat’ through a phenomenological lens. Central to the study was the lived experience of yoga in a purposive sample of self-identified New Zealand practitioners (n=38; 89.5% female; aged 18 to 65 years; 60.5% aged 36 to 55 years). The study’s aim was to explore whether habitual yoga practitioners experience any pro-health downstream effects of their practice ‘off the mat’ via their lived experience of yoga. A qualitative mixed methodology was applied via a phenomenological lens that explicitly acknowledged the researcher’s own experience of the research topic. Qualitative methods comprised an open-ended online survey for all participants (n=38), followed by in-depth semi-structured interviews (n=8) on a randomized subset. Quantitative methods included online outcome measures (health habits, self-efficacy, interoceptive awareness, and physical activity), practice component data (tenure, dose, yoga styles, yoga teacher status, meditation frequency), and socio-demographics. This paper highlights the qualitative findings emerging from participant narratives. Reported benefits of practice included the provision of a filter through which to engage with life and the experience of self-regulation and mindfulness ‘off the mat’. Practitioners experienced yoga as a self-sustaining positive resource via self-regulation guided by an embodied awareness. The key narrative to emerge was an attunement to embodiment through movement. Embodied movement can elicit self-regulatory pathways that support health behavior.

Keywords: embodiment, habit, interoception, mindfulness, movement practice, qualitative, self-regulation, yoga.

Historically and in the present day, Black women’s positionality in the U.S. has paradoxically situated them in a society where they are both intrinsically essential and treated as expendable. This positionality, known as gendered racism, manifests commonly in professional environments and results in myriad harms. In response, Black women have developed, honed, and practiced a range of coping styles to mitigate the insidious effects of gendered racism. While often effective in the short-term, these techniques frequently complicate Black women’s well-being. For Black female clinicians who experience gendered racism and work on the frontlines of community mental health, myriad bio-psycho-social-spiritual harms compound. This project provided an opportunity for Black female clinicians from across the U.S. to share their experiences during the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and anti-Black violence. I conducted in-depth interviews with clinicians (n=14) between the ages of 30 and 58. Using the Listening Guide voice-centered approach to data generation and analysis, I identified four voices to help answer this project’s central question: How do you experience being a Black female clinician in the U.S.? The voices of self, pride, vigilance, and mediating narrated the complex ways participants experienced their workplaces. This complexity seemed to be context-specific, depending on whether the clinicians worked in predominantly White workplaces (PWW), a mix of PWW and private practice, or private practice exclusively. Participants who worked only in PWW experienced the greatest stress, oppression, and burnout risk, while participants who worked exclusively in private practice reported more joy, more authenticity, and more job satisfaction. These findings have implications for mentoring, supporting, and retaining Black female clinicians.

Keywords: Black female clinicians, professional experiences, gendered racism, Listening Guide voice-centered approach.

The purpose of this article is to speak directly to the paucity of research regarding Dominican American women and identity narratives. To do so, this article uses the Listening Guide Method of Qualitative Inquiry (Gilligan, et al., 2006) to explore how 1.5 and second-generation Dominican American women narrated their experiences of individual identity within American cultural contexts and constructs. The results draw from the emergence of themes across six participant interviews and showed two distinct voices: The Voice of Cultural Explanation and the Tides of Dominican American Female Identity. Narrative examples from five participants are offered to illustrate where 1.5 and second-generation Dominican American women negotiate their identity narratives at the intersection of their Dominican and American selves. The article offers two conclusions. One, that participant women use the Voice of Cultural Explanation in order to discuss their identity as reflected within the broad cultural tensions of their daily lives. Two, that the Tides of Dominican American Female Identity are used to express strong emotions that manifest within their personal narratives as the unwanted distance from either the Dominican or American parts of their person.

Keywords: Dominican American, women, identity, the Listening Guide, narratives

- Open access

- Published: 02 April 2022

A qualitative study of rural healthcare providers’ views of social, cultural, and programmatic barriers to healthcare access

- Nicholas C. Coombs 1 ,

- Duncan G. Campbell 2 &

- James Caringi 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 22 , Article number: 438 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

19 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Ensuring access to healthcare is a complex, multi-dimensional health challenge. Since the inception of the coronavirus pandemic, this challenge is more pressing. Some dimensions of access are difficult to quantify, namely characteristics that influence healthcare services to be both acceptable and appropriate. These link to a patient’s acceptance of services that they are to receive and ensuring appropriate fit between services and a patient’s specific healthcare needs. These dimensions of access are particularly evident in rural health systems where additional structural barriers make accessing healthcare more difficult. Thus, it is important to examine healthcare access barriers in rural-specific areas to understand their origin and implications for resolution.

We used qualitative methods and a convenience sample of healthcare providers who currently practice in the rural US state of Montana. Our sample included 12 healthcare providers from diverse training backgrounds and specialties. All were decision-makers in the development or revision of patients’ treatment plans. Semi-structured interviews and content analysis were used to explore barriers–appropriateness and acceptability–to healthcare access in their patient populations. Our analysis was both deductive and inductive and focused on three analytic domains: cultural considerations, patient-provider communication, and provider-provider communication. Member checks ensured credibility and trustworthiness of our findings.

Five key themes emerged from analysis: 1) a friction exists between aspects of patients’ rural identities and healthcare systems; 2) facilitating access to healthcare requires application of and respect for cultural differences; 3) communication between healthcare providers is systematically fragmented; 4) time and resource constraints disproportionately harm rural health systems; and 5) profits are prioritized over addressing barriers to healthcare access in the US.

Conclusions

Inadequate access to healthcare is an issue in the US, particularly in rural areas. Rural healthcare consumers compose a hard-to-reach patient population. Too few providers exist to meet population health needs, and fragmented communication impairs rural health systems’ ability to function. These issues exacerbate the difficulty of ensuring acceptable and appropriate delivery of healthcare services, which compound all other barriers to healthcare access for rural residents. Each dimension of access must be monitored to improve patient experiences and outcomes for rural Americans.

Peer Review reports

Unequal access to healthcare services is an important element of health disparities in the United States [ 1 ], and there remains much about access that is not fully understood. The lack of understanding is attributable, in part, to the lack of uniformity in how access is defined and evaluated, and the extent to which access is often oversimplified in research [ 2 ]. Subsequently, attempts to address population-level barriers to healthcare access are insufficient, and access remains an unresolved, complex health challenge [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. This paper presents a study that aims to explore some of the less well studied barriers to healthcare access, particularly those that influence healthcare acceptability and appropriateness.

In truth, healthcare access entails a complicated calculus that combines characteristics of individuals, their households, and their social and physical environments with characteristics of healthcare delivery systems, organizations, and healthcare providers. For one to fully ‘access’ healthcare, they must have the means to identify their healthcare needs and have available to them care providers and the facilities where they work. Further, patients must then reach, obtain, and use the healthcare services in order to have their healthcare needs fulfilled. Levesque and colleagues critically examined access conceptualizations in 2013 and synthesized all ways in which access to healthcare was previously characterized; Levesque et al. proposed five dimensions of access: approachability, acceptability, availability, affordability and appropriateness [ 2 ]. These refer to the ability to perceive, seek, reach, pay for, and engage in services, respectively.

According to Levesque et al.’s framework, the five dimensions combine to facilitate access to care or serve as barriers. Approachability indicates that people facing health needs understand that healthcare services exist and might be helpful. Acceptability represents whether patients see healthcare services as consistent or inconsistent with their own social and cultural values and worldviews. Availability indicates that healthcare services are reached both physically and in a timely manner. Affordability simplifies one’s capacity to pay for healthcare services without compromising basic necessities, and finally, appropriateness represents the fit between healthcare services and a patient’s specific healthcare needs [ 2 ]. This study focused on the acceptability and appropriateness dimensions of access.

Before the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19) pandemic, approximately 13.3% of adults in the US did not have a usual source of healthcare [ 6 ]. Millions more did not utilize services regularly, and close to two-thirds reported that they would be debilitated by an unexpected medical bill [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Findings like these emphasized a fragility in the financial security of the American population [ 10 ]. These concerns were exacerbated by the pandemic when a sudden surge in unemployment increased un- and under-insurance rates [ 11 ]. Indeed, employer-sponsored insurance covers close to half of Americans’ total cost of illness [ 12 ]. Unemployment linked to COVID-19 cut off the lone outlet to healthcare access for many. Health-related financial concerns expanded beyond individuals, as healthcare organizations were unequipped to manage a simultaneous increase in demand for specialized healthcare services and a steep drop off for routine revenue-generating healthcare services [ 13 ]. These consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic all put additional, unexpected pressure on an already fragmented US healthcare system.

Other structural barriers to healthcare access exist in relation to the rural–urban divide. Less than 10% of US healthcare resources are located in rural areas where approximately 20% of the American population resides [ 14 ]. In a country with substantially fewer providers per capita compared to many other developed countries, persons in rural areas experience uniquely pressing healthcare provider shortages [ 15 , 16 ]. Rural inhabitants also tend to have lower household income, higher rates of un- or under-insurance, and more difficulty with travel to healthcare clinics than urban dwellers [ 17 ]. Subsequently, persons in rural communities use healthcare services at lower rates, and potentially preventable hospitalizations are more prevalent [ 18 ]. This disparity often leads rural residents to use services primarily for more urgent needs and less so for routine care [ 19 , 20 , 21 ].

The differences in how rural and urban healthcare systems function warranted a federal initiative to focus exclusively on rural health priorities and serve as counterpart to Healthy People objectives [ 22 ]. The rural determinants of health, a more specific expression of general social determinants, add issues of geography and topography to the well-documented social, economic and political factors that influence all Americans’ access to healthcare [ 23 ]. As a result, access is consistently regarded as a top priority in rural areas, and many research efforts have explored the intersection between access and rurality, namely within its less understood dimensions (acceptability and appropriateness) [ 22 ].

Acceptability-related barriers to care

Acceptability represents the dimension of healthcare access that affects a patient’s ability to seek healthcare, particularly linked to one’s professional values, norms and culture [ 2 ]. Access to health information is an influential factor for acceptable healthcare and is essential to promote and maintain a healthy population [ 24 ]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, health literacy or a high ‘health IQ’ is the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others, which impacts healthcare use and system navigation [ 25 ]. The literature indicates that lower levels of health literacy contribute to health disparities among rural populations [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. Evidence points to a need for effective health communication between healthcare organizations and patients to improve health literacy [ 24 ]. However, little research has been done in this area, particularly as it relates to technologically-based interventions to disseminate health information [ 29 ].

Stigma, an undesirable position of perceived diminished status in an individual’s social position, is another challenge that influences healthcare acceptability [ 30 ]. Those who may experience stigma fear negative social consequences in relation to care seeking. They are more likely to delay seeking care, especially among ethnic minority populations [ 31 , 32 ]. Social media presents opportunities for the dissemination of misleading medical information; this runs further risk for stigma [ 33 ]. Stigma is difficult to undo, but research has shown that developing a positive relationship with a healthcare provider or organization can work to reduce stigma among patients, thus promoting healthcare acceptability [ 34 ].

A provider’s attempts to engage patients and empower them to be active decision-makers regarding their treatment has also been shown to improve healthcare acceptability. One study found that patients with heart disease who completed a daily diary of weight and self-assessment of symptoms, per correspondence with their provider, had better care outcomes than those who did not [ 35 ]. Engaging with household family members and involved community healers also mitigates barriers to care, emphasizing the importance of a team-based approach that extends beyond those who typically provide healthcare services [ 36 , 37 ]. One study, for instance, explored how individuals closest to a pregnant woman affect the woman’s decision to seek maternity care; partners, female relatives, and community health-workers were among the most influential in promoting negative views, all of which reduced a woman’s likelihood to access care [ 38 ].

Appropriateness-related barriers to care

Appropriateness marks the dimension of healthcare access that affects a patient’s ability to engage, and according to Levesque et al., is of relevance once all other dimensions (the ability to perceive, seek, reach and pay for) are achieved [ 2 ]. The ability to engage in healthcare is influenced by a patient’s level of empowerment, adherence to information, and support received by their healthcare provider. Thus, barriers to healthcare access that relate to appropriateness are often those that indicate a breakdown in communication between a patient with their healthcare provider. Such breakdown can involve a patient experiencing miscommunication, confrontation, and/or a discrepancy between their provider’s goals and their own goals for healthcare. Appropriateness represents a dimension of healthcare access that is widely acknowledged as an area in need of improvement, which indicates a need to rethink how healthcare providers and organizations can adapt to serve the healthcare needs of their communities [ 39 ]. This is especially true for rural, ethnic minority populations, which disproportionately experience an abundance of other barriers to healthcare access. Culturally appropriate care is especially important for members of minority populations [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Ultimately, patients value a patient-provider relationship characterized by a welcoming, non-judgmental atmosphere [ 43 , 44 ]. In rural settings especially, level of trust and familiarity are common factors that affect service utilization [ 45 ]. Evidence suggests that kind treatment by a healthcare provider who promotes patient-centered care can have a greater overall effect on a patient’s experience than a provider’s degree of medical knowledge or use of modern equipment [ 46 ]. Of course, investing the time needed to nurture close and caring interpersonal connections is particularly difficult in under-resourced, time-pressured rural health systems [ 47 , 48 ].

The most effective way to evaluate access to healthcare largely depends on which dimensions are explored. For instance, a population-based survey can be used to measure the barrier of healthcare affordability. Survey questions can inquire directly about health insurance coverage, care-related financial burden, concern about healthcare costs, and the feared financial impacts of illness and/or disability. Many national organizations have employed such surveys to measure affordability-related barriers to healthcare. For example, a question may ask explicitly about financial concerns: ‘If you get sick or have an accident, how worried are you that you will not be able to pay your medical bills?’ [ 49 ]. Approachability and availability dimensions of access are also studied using quantitative analysis of survey questions, such as ‘Is there a place that you usually go to when you are sick or need advice about your health?’ or ‘Have you ever delayed getting medical care because you couldn’t get through on the telephone?’ In contrast, the remaining two dimensions–acceptability and appropriateness–require a qualitative approach, as the social and cultural factors that determine a patient’s likelihood of accepting aspects of the services that are to be received (acceptability) and the fit between those services and the patient’s specific healthcare needs (appropriateness) can be more abstract [ 50 , 51 ]. In social science, qualitative methods are appropriate to generate knowledge of what social events mean to individuals and how those individuals interact within them; these methods allow for an exploration of depth rather than breadth [ 52 , 53 ]. Qualitative methods, therefore, are appropriate tools for understanding the depth of healthcare providers’ experiences in the inherently social context of seeking and engaging in healthcare.

In sum, acceptability- and appropriateness-related barriers to healthcare access are multi-layered, complex and abundant. Ensuring access becomes even more challenging if structural barriers to access are factored in. In this study, we aimed to explore barriers to healthcare access among persons in Montana, a historically underserved, under-resourced, rural region of the US. Montana is the fourth largest and third least densely populated state in the country; more than 80% of Montana counties are classified as non-core (the lowest level of urban/rural classification), and over 90% are designated as health professional shortage areas [ 54 , 55 ]. Qualitative methods supported our inquiry to explore barriers to healthcare access related to acceptability and appropriateness.

Participants

Qualitative methods were utilized for this interpretive, exploratory study because knowledge regarding barriers to healthcare access within Montana’s rural health systems is limited. We chose Montana healthcare providers, rather than patients, as the population of interest so we may explore barriers to healthcare access from the perspective of those who serve many persons in rural settings. Inclusion criteria required study participants to provide direct healthcare to patients at least one-half of their time. We defined ‘provider’ as a healthcare organization employee with clinical decision-making power and the qualifications to develop or revise patients’ treatment plans. In an attempt to capture a group of providers with diverse experience, we included providers across several types and specialties. These included advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), physicians (MDs and DOs), and physician assistants (PAs) who worked in critical care medicine, emergency medicine, family medicine, hospital medicine, internal medicine, pain medicine, palliative medicine, pediatrics, psychiatry, and urgent care medicine. We also included licensed clinical social workers (LCSWs) and clinical psychologists who specialize in behavioral healthcare provision.

Recruitment and Data Collection

We recruited participants via email using a snowball sampling approach [ 56 ]. We opted for this approach because of its effectiveness in time-pressured contexts, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which has made healthcare provider populations hard to reach [ 57 ]. Considering additional constraints with the pandemic and the rural nature of Montana, interviews were administered virtually via Zoom video or telephone conferencing with Zoom’s audio recording function enabled. All interviews were conducted by the first author between January and September 2021. The average length of interviews was 50 min, ranging from 35 to 70 min. There were occasional challenges experienced during interviews (poor cell phone reception from participants, dropped calls), in which case the interviewer remained on the line until adequate communication was resumed. All interviews were included for analysis and transcribed verbatim into NVivo Version 12 software. All qualitative data were saved and stored on a password-protected University of Montana server. Hard-copy field notes were securely stored in a locked office on the university’s main campus.

Data analysis included a deductive followed by an inductive approach. This dual analysis adheres to Levesque’s framework for qualitative methods, which is discussed in the Definition of Analytic Domains sub-section below. Original synthesis of the literature informed the development of our initial deductive codebook. The deductive approach was derived from a theory-driven hypothesis, which consisted of synthesizing previous research findings regarding acceptability- and appropriateness-related barriers to care. Although the locations, patient populations and specific type of healthcare services varied by study in the existing literature, several recurring barriers to healthcare access were identified. We then operationalized three analytic domains based on these findings: cultural considerations, patient-provider communication, and provider-provider communication. These domains were chosen for two reasons: 1) the terms ‘culture’ and ‘communication’ were the most frequently documented characteristics across the studies examined, and 2) they each align closely with the acceptability and appropriateness dimensions of access to healthcare, respectively. In addition, ‘culture’ is included in the definition of acceptability and ‘communication’ is a quintessential aspect of appropriateness. These domains guided the deductive portion of our analysis, which facilitated the development of an interview guide used for this study.

Interviews were semi-structured to allow broad interpretations from participants and expand the open-ended characterization of study findings. Data were analyzed through a flexible coding approach proposed by Deterding and Waters [ 58 ]. Qualitative content analysis was used, a method particularly beneficial for analyzing large amounts of qualitative data collected through interviews that offers possibility of quantifying categories to identify emerging themes [ 52 , 59 ]. After fifty percent of data were analyzed, we used an inductive approach as a formative check and repeated until data saturation, or the point at which no new information was gathered in interviews [ 60 ]. At each point of inductive analysis, interview questions were added, removed, or revised in consideration of findings gathered [ 61 ]. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) was used for reporting all qualitative data for this study [ 62 ]. The first and third authors served as primary and secondary analysts of the qualitative data and collaborated to triangulate these findings. An audit approach was employed, which consisted of coding completed by the first author and then reviewed by the third author. After analyses were complete, member checks ensured credibility and trustworthiness of findings [ 63 ]. Member checks consisted of contacting each study participant to explain the study’s findings; one-third of participants responded and confirmed all findings. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the authors’ institution’s Institutional Review Board.

Definitions of Analytic Domains

Cultural considerations.

Western health systems often fail to consider aspects of patients’ cultural perspectives and histories. This can manifest in the form of a providers’ lack of cultural humility. Cultural humility is a process of preventing imposition of one’s worldview and cultural beliefs on others and recognizing that everyone’s conception of the world is valid. Humility cultivates sensitive approaches in treating patients [ 64 ]. A lack of cultural humility impedes the delivery of acceptable and appropriate healthcare [ 65 ], which can involve low empathy or respect for patients, or dismissal of culture and traditions as superstitions that interfere with standard treatments [ 66 , 67 ]. Ensuring cultural humility among all healthcare employees is a step toward optimal healthcare delivery. Cultural humility is often accomplished through training that can be tailored to particular cultural- or gender-specific populations [ 68 , 69 ]. Since cultural identities and humility have been marked as factors that can heavily influence patients’ access to care, cultural considerations composed our first analytic domain. To assess this domain, we asked participants how they address the unique needs of their patients, how they react when they observe a cultural behavior or attitude from a patient that may not directly align with their treatment plan, and if they have received any multicultural training or training on cultural considerations in their current role.

Patient-provider communication

Other barriers to healthcare access can be linked to ineffective patient-provider communication. Patients who do not feel involved in healthcare decisions are less likely to adhere to treatment recommendations [ 70 ]. Patients who experience communication difficulties with providers may feel coerced, which generates disempowerment and leads patients to employ more covert ways of engagement [ 71 , 72 ]. Language barriers can further compromise communication and hinder outcomes or patient progress [ 73 , 74 ]. Any miscommunication between a patient and provider can affect one’s access to healthcare, namely affecting appropriateness-related barriers. For these reasons, patient-provider communication composed our second analytic domain. We asked participants to highlight the challenges they experience when communicating with their patients, how those complications are addressed, and how communication strategies inform confidentiality in their practice. Confidentiality is a core ethical principle in healthcare, especially in rural areas that have smaller, interconnected patient populations [ 75 ].

Provider-Provider Communication

A patient’s journey through the healthcare system necessitates sufficient correspondence between patients, primary, and secondary providers after discharge and care encounters [ 76 ]. Inter-provider and patient-provider communication are areas of healthcare that are acknowledged to have some gaps. Inconsistent mechanisms for follow up communication with patients in primary care have been documented and emphasized as a concern among those with chronic illness who require close monitoring [ 68 , 77 ]. Similar inconsistencies exist between providers, which can lead to unclear care goals, extended hospital stays, and increased medical costs [ 78 ]. For these reasons, provider-provider communication composed our third analytic domain. We asked participants to describe the approaches they take to streamline communication after a patient’s hospital visit, the methods they use to ensure collaborative communication between primary or secondary providers, and where communication challenges exist.

Healthcare provider characteristics

Our sample included 12 providers: four in family medicine (1 MD, 1 DO, 1 PA & 1 APRN), three in pediatrics (2 MD with specialty in hospital medicine & 1 DO), three in palliative medicine (2 MDs & 1 APRN with specialty in wound care), one in critical care medicine (DO with specialty in pediatric pulmonology) and one in behavioral health (1 LCSW with specialty in trauma). Our participants averaged 9 years (range 2–15) as a healthcare provider; most reported more than 5 years in their current professional role. The diversity of participants extended to their patient populations as well, with each participant reporting a unique distribution of age, race and level of medical complexity among their patients. Most participants reported that a portion of their patients travel up to five hours, sometimes across county- or state-lines, to receive care.

Theme 1: A friction exists between aspects of patients’ rural identities and healthcare systems

Our participants comprised a collection of medical professions and reported variability among health-related reasons their patients seek care. However, most participants acknowledged similar characteristics that influence their patients’ challenges to healthcare access. These identified factors formed categories from which the first theme emerged. There exists a great deal of ‘rugged individualism’ among Montanans, which reflects a self-sufficient and self-reliant way of life. Stoicism marked a primary factor to characterize this quality. One participant explained:

True Montanans are difficult to treat medically because they tend to be a tough group. They don’t see doctors. They don’t want to go, and they don’t want to be sick. That’s an aspect of Montana that makes health culture a little bit difficult.

Another participant echoed this finding by stating:

The backwoods Montana range guy who has an identity of being strong and independent probably doesn’t seek out a lot of medical care or take a lot of medications. Their sense of vitality, independence and identity really come from being able to take care and rely on themselves. When that is threatened, that’s going to create a unique experience of illness.

Similar responses were shared by all twelve participants; stoicism seemed to be heavily embedded in many patient populations in Montana and serves as a key determinant of healthcare acceptability. There are additional factors, however, that may interact with stoicism but are multiply determined. Stigma is an example of this, presented in this context as one’s concern about judgement by the healthcare system. Respondents were openly critical of this perception of the healthcare system as it was widely discussed in interviews. One participant stated:

There is a real perception of a punitive nature in the medical community, particularly if I observe a health issue other than the primary reason for one’s hospital visit, whether that may be predicated on medical neglect, delay of care, or something that may warrant a report to social services. For many of the patients and families I see, it’s not a positive experience and one that is sometimes an uphill barrier that I work hard to circumnavigate.