Fruits, vegetables, and health: A comprehensive narrative, umbrella review of the science and recommendations for enhanced public policy to improve intake

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Nutrition and Food Studies, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia, USA.

- 2 Think Healthy Group, Inc., Washington, DC, USA.

- 3 Department of Nutrition Science, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, USA.

- 4 Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

- 5 Center for Nutrition Research, Institute for Food Safety and Health, Illinois Institute of Technology, Bedford Park, Illinois, USA.

- 6 Biofortis Research, Merieux NutriSciences, Addison, Illinois, USA.

- 7 Department of Human Nutrition, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, USA.

- 8 Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

- 9 School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego State University, San Diego, California, USA.

- 10 Bone and Body Composition Laboratory, College of Family and Consumer Sciences, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA.

- 11 College of Education and Human Ecology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

- 12 Department of Nutritional Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA.

- 13 D&V Systematic Evidence Review, Bronx, New York, USA.

- PMID: 31267783

- DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1632258

Fruit and vegetables (F&V) have been a cornerstone of healthy dietary recommendations; the 2015-2020 U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend that F&V constitute one-half of the plate at each meal. F&V include a diverse collection of plant foods that vary in their energy, nutrient, and dietary bioactive contents. F&V have potential health-promoting effects beyond providing basic nutrition needs in humans, including their role in reducing inflammation and their potential preventive effects on various chronic disease states leading to decreases in years lost due to premature mortality and years lived with disability/morbidity. Current global intakes of F&V are well below recommendations. Given the importance of F&V for health, public policies that promote dietary interventions to help increase F&V intake are warranted. This externally commissioned expert comprehensive narrative, umbrella review summarizes up-to-date clinical and observational evidence on current intakes of F&V, discusses the available evidence on the potential health benefits of F&V, and offers implementation strategies to help ensure that public health messaging is reflective of current science. This review demonstrates that F&V provide benefits beyond helping to achieve basic nutrient requirements in humans. The scientific evidence for providing public health recommendations to increase F&V consumption for prevention of disease is strong. Current evidence suggests that F&V have the strongest effects in relation to prevention of CVDs, noting a nonlinear threshold effect of 800 g per day (i.e., about 5 servings a day). A growing body of clinical evidence (mostly small RCTs) demonstrates effects of specific F&V on certain chronic disease states; however, more research on the role of individual F&V for specific disease prevention strategies is still needed in many areas. Data from the systematic reviews and mostly observational studies cited in this report also support intake of certain types of F&V, particularly cruciferous vegetables, dark-green leafy vegetables, citrus fruits, and dark-colored berries, which have superior effects on biomarkers, surrogate endpoints, and outcomes of chronic disease.

Keywords: Fruit; health; nutrition; produce; vegetable.

Publication types

- Diet, Healthy*

- Nutrition Policy*

- Observational Studies as Topic

- Systematic Reviews as Topic

- United States

- Vegetables*

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 25 Jan 2021

- Working Paper Summaries

India’s Food Supply Chain During the Pandemic

Policy makers in the developing world face important tradeoffs in reacting to a pandemic. The quick and complete recovery of India’s food supply chain suggests that strict lockdown measures at the onset of pandemics need not cause long-term economic damage.

- 08 Jun 2020

Food Security and Human Mobility During the Covid-19 Lockdown

COVID-19 represents not only a health crisis but a crisis of food insecurity and starvation for migrants. Central governments should ensure that food security policies are implemented effectively and engage with local governments and local stakeholders to distribute food to migrants in the immediate term.

- 29 May 2020

How Leaders Are Fighting Food Insecurity on Three Continents

The pandemic could almost double the number of people facing food crises in lower-income populations by the end of 2020. Howard Stevenson and Shirley Spence show how organizations are responding. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 31 Jan 2019

- Cold Call Podcast

How Wegmans Became a Leader in Improving Food Safety

Ray Goldberg discusses how the CEO of the Wegmans grocery chain faced a food safety issue and then helped the industry become more proactive. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 15 Nov 2018

Can the Global Food Industry Overcome Public Distrust?

The public is losing trust in many institutions involved in putting food on our table, says Ray A. Goldberg, author of the new book Food Citizenship. Here's what needs to be done. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 15 Mar 2018

Targeted Price Controls on Supermarket Products

Governments sometimes consider targeted price controls when popular goods become less affordable. Looking at price controls in Argentina between 2007 and 2015, this study’s findings suggest that new technologies like mobile phones are allowing governments to better enforce targeted price control programs, but the impact of these policies on aggregate inflation is small and short-lived.

- 26 Jun 2017

- Research & Ideas

How Cellophane Changed the Way We Shop for Food

Research by Ai Hisano exposes cellophane's key role in developing self-service merchandising in American grocery stores, and how its manufacturers tried to control the narrative of how women buy food. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 31 May 2017

- Sharpening Your Skills

10 Harvard Business School Research Stories That Will Make Your Mouth Water

The food industry is under intense study at Harvard Business School. This story sampler looks at issues including restaurant marketing, chefs as CEOs, and the business of food science. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 18 Nov 2016

Standardized Color in the Food Industry: The Co-Creation of the Food Coloring Business in the United States, 1870–1940

Beginning in the late 19th century, US food manufacturers tried to create the “right” color of foods that many consumers would recognize and in time take for granted. The United States became a leading country in the food coloring business with the rise of extensive mass marketing. By 1938, when Congress enacted the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, the food coloring business had become a central and permanent component of food marketing strategies. This paper shows how food manufacturers, dye makers, and regulators co-created the food coloring business. Food-coloring practices became integrated into an entire strategy of manufacturing and marketing in the food industry.

- 16 May 2016

Food Safety Economics: The Cost of a Sick Customer

When restaurants source from local growers, it can be more difficult to assess product safety—just another wrinkle in high-stakes efforts to keep our food from harming us. Just ask Chipotle. John A. Quelch discusses a recent case study on food testing. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 15 May 2007

I’ll Have the Ice Cream Soon and the Vegetables Later: Decreasing Impatience over Time in Online Grocery Orders

How do people’s preferences differ when they make choices for the near term versus the more distant future? Providing evidence from a field study of an online grocer, this research shows that people act as if they will be increasingly virtuous the further into the future they project. Researchers examined how the length of delay between when an online grocery order is completed and when it is delivered affects what consumers order. They find that consumers purchase more "should" (healthy) groceries such as vegetables and less "want" (unhealthy) groceries such as ice cream the greater the delay between order completion and order delivery. The results have implications for public policy, supply chain managers, and models of time discounting. Key concepts include: Consumers spend less and order a higher percentage of "should" items and a lower percentage of "want" items the further in advance of delivery they place a grocery order. Encouraging people to order their groceries up to 5 days in advance of consumption could influence the healthfulness of the foods that people consume. Similarly, asking students in schools to select their lunches up to a week in advance could considerably increase the healthfulness of the foods they elect to eat. Online and catalog retailers that offer a range of goods as well as different delivery options might be able to improve their demand forecasting by understanding these findings. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

News releases.

News Release

Thursday, May 16, 2019

NIH study finds heavily processed foods cause overeating and weight gain

Small-scale trial is the first randomized, controlled research of its kind.

People eating ultra-processed foods ate more calories and gained more weight than when they ate a minimally processed diet, according to results from a National Institutes of Health study. The difference occurred even though meals provided to the volunteers in both the ultra-processed and minimally processed diets had the same number of calories and macronutrients. The results were published in Cell Metabolism .

This small-scale study of 20 adult volunteers, conducted by researchers at the NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), is the first randomized controlled trial examining the effects of ultra-processed foods as defined by the NOVA classification system . This system considers foods “ultra-processed” if they have ingredients predominantly found in industrial food manufacturing, such as hydrogenated oils, high-fructose corn syrup, flavoring agents, and emulsifiers.

Previous observational studies looking at large groups of people had shown associations between diets high in processed foods and health problems. But, because none of the past studies randomly assigned people to eat specific foods and then measured the results, scientists could not say for sure whether the processed foods were a problem on their own, or whether people eating them had health problems for other reasons, such as a lack of access to fresh foods.

“Though we examined a small group, results from this tightly controlled experiment showed a clear and consistent difference between the two diets,” said Kevin D. Hall, Ph.D., an NIDDK senior investigator and the study’s lead author. “This is the first study to demonstrate causality — that ultra-processed foods cause people to eat too many calories and gain weight.”

For the study, researchers admitted 20 healthy adult volunteers, 10 male and 10 female, to the NIH Clinical Center for one continuous month and, in random order for two weeks on each diet, provided them with meals made up of ultra-processed foods or meals of minimally processed foods. For example, an ultra-processed breakfast might consist of a bagel with cream cheese and turkey bacon, while the unprocessed breakfast was oatmeal with bananas, walnuts, and skim milk.

The ultra-processed and unprocessed meals had the same amounts of calories, sugars, fiber, fat, and carbohydrates, and participants could eat as much or as little as they wanted.

On the ultra-processed diet, people ate about 500 calories more per day than they did on the unprocessed diet. They also ate faster on the ultra-processed diet and gained weight, whereas they lost weight on the unprocessed diet. Participants, on average, gained 0.9 kilograms, or 2 pounds, while they were on the ultra-processed diet and lost an equivalent amount on the unprocessed diet.

“We need to figure out what specific aspect of the ultra-processed foods affected people’s eating behavior and led them to gain weight,” Hall said. “The next step is to design similar studies with a reformulated ultra-processed diet to see if the changes can make the diet effect on calorie intake and body weight disappear.”

For example, slight differences in protein levels between the ultra-processed and unprocessed diets in this study could potentially explain as much as half the difference in calorie intake.

“Over time, extra calories add up, and that extra weight can lead to serious health conditions,” said NIDDK Director Griffin P. Rodgers, M.D. “Research like this is an important part of understanding the role of nutrition in health and may also help people identify foods that are both nutritious and accessible — helping people stay healthy for the long term.”

While the study reinforces the benefits of unprocessed foods, researchers note that ultra-processed foods can be difficult to restrict. “We have to be mindful that it takes more time and more money to prepare less-processed foods,” Hall said. “Just telling people to eat healthier may not be effective for some people without improved access to healthy foods.”

Support for the study primarily came from the NIDDK Division of Intramural Research.

About the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): The NIDDK, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), conducts and supports research on diabetes and other endocrine and metabolic diseases; digestive diseases, nutrition and obesity; and kidney, urologic and hematologic diseases. Spanning the full spectrum of medicine and afflicting people of all ages and ethnic groups, these diseases encompass some of the most common, severe, and disabling conditions affecting Americans. For more information about the NIDDK and its programs, see https://www.niddk.nih.gov .

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov .

NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health ®

Hall KD, et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: A one-month inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metabolism . May 16, 2019.

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Watch CBS News

Limit these ultra-processed foods for longer-term health, 30-year study suggests

By Sara Moniuszko

Edited By Paula Cohen

Updated on: May 10, 2024 / 11:09 AM EDT / CBS News

New research is adding to the evidence linking ultra-processed foods to health concerns. The study tracked people's habits over 30 years and found those who reported eating more of certain ultra-processed foods had a slightly higher risk of death — with four categories of foods found to be the biggest culprits.

For the study, published in The BMJ , researchers analyzed data on more than 100,000 U.S. adults with no history of cancer, cardiovascular disease or diabetes. Every four years between 1986 and 2018, the participants completed a detailed food questionnaire.

The data showed those who ate the most ultra-processed food — about 7 servings per day — had a 4% higher risk of death by any cause, compared to participants who ate the lowest amount, a median of about 3 servings per day.

Ultra-processed foods include "packaged baked goods and snacks, fizzy drinks, sugary cereals, and ready-to-eat or heat products," a news release for the study noted. "They often contain colors, emulsifiers, flavors, and other additives and are typically high in energy, added sugar, saturated fat, and salt, but lack vitamins and fiber."

Foods with the strongest associations with increased mortality, according to the study, included:

- Ready-to-eat meat, poultry and seafood-based products

- Sugary drinks

- Dairy-based desserts

- Highly processed breakfast foods

Ultra-processed food is a "very mixed group of very different foods," the lead author of the study, Mingyang Song, told CBS News , meaning these categories can offer a helpful distinction.

"Some of the foods actually have really beneficial ingredients like vitamins, minerals, so that's why we always recommend that people not focus too much on the (whole of) ultra-processed food, but rather the individual categories of ultra-processed food."

The research included a large number of participants over a long timespan, but it did have some limitations. As an observational study, no exact cause-and-effect conclusions can be drawn. And the participants were health professionals and predominantly White and non-Hispanic, "limiting the generalizability of our findings," the authors acknowledged.

But they wrote that the findings "provide support for limiting consumption of certain types of ultra-processed food for long term health."

"Future studies are warranted to improve the classification of ultra-processed foods and confirm our findings in other populations," they added.

This study comes after other research published earlier this year found diets high in ultra-processed food are associated with an increased risk of 32 damaging health outcomes , including higher risk for cancer, major heart and lung conditions, gastrointestinal issues, obesity, type 2 diabetes, sleep issues, mental health disorders and early death.

Sara Moniuszko is a health and lifestyle reporter at CBSNews.com. Previously, she wrote for USA Today, where she was selected to help launch the newspaper's wellness vertical. She now covers breaking and trending news for CBS News' HealthWatch.

More from CBS News

Summer 2023 was the hottest in 2,000 years, study finds

Drug overdose deaths decreased in 2023

Drowning deaths surged during the pandemic — and it was worse among Black people, CDC reports

The lure of specialty medicine pulls nurse practitioners from primary care

Quick Links

- UW School of Medicine

Food, Nutrition, and Metabolism

Food, nutrition & metabolism.

Participate in Research is designed to connect potential volunteers with open research studies. We are looking for volunteers just like you to help answer important questions about food, nutrition, and metabolism. This page lists food, nutrition, and metabolism studies that may apply to you or someone you know. If you find a study that you’d like to participate in, you can contact the study team with questions or to volunteer. Join us to improve the health of others.

Active Studies

Adapt study.

ADAPT study hopes to learn if body and brain changes can predict why weight loss stops. This study requires in-person and remote visits over 18 months at UW South Lake Union and Fred Hutchinson.1. Screening visit in-person: ~2 hours at UW SLU*remote tasks leading up…

Project CONQUER

Do you struggle with binge eating? Want to receive free treatment? Research at Drexel University are looking for volunteers to participate in a NIH-funded study offering a free, remote, self-guided treatment. Individuals aged 18-65 having BMI ≥ 18.5 may be eligible to participate. Up to…

Endometriosis Dietary Study

Active participation in the study is over a 12-week period. All participants will be asked to complete questionnaires online at 4 times during the study period (questionnaires focus on pain and quality of life questions)and are randomized to either a dietary intervention or a control…

Mobile Intervention to Support Mediterranean Diet (MedD) for Persons with Memory Loss

We are the study team from the University of Washington School of Nursing inviting you to join our research project. We are seeking participants interested in joining our upcoming study aimed at helping people aged 65 and older with changes in memory to eat healthier….

Neuroimaging in Youth and Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes

One in five adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes exhibit disordered eating behaviors (DEB)—nearly twice the rate among healthy peers and affecting females more than males. Several studies show that those with DEB have worse health outcomes. Researchers at the Seattle Children’s Hospital…

The EVO Study

EVO is a 12-month healthy lifestyle and weight loss research study taking place in the Department of Preventive Medicine at Northwestern University. Researchers are looking to determine the best strategy for weight loss and healthy living. Participants enroll in the 12-month, remotely-delivered study and receive…

The main question the WYE study is exploring: Does the brain change after short term diet changes and can MRI detect these changes?Participants will have an in-person screening visit (about 2 hours), then 5 in-person study visits at UW SLU in the morning over a…

Golden Age Activity Survey

This research study is a collaboration between the University of Wyoming and the University of Washington. We are asking you to complete this survey because you are over the age of 65 years. The purpose of this survey is to better understand various health behaviors…

the FRESH study: Frequency of Eating and its Effects on Satiety and Health

How many times a day should we eat, and why? How big or small should our meals be, and why? How does meal frequency affect appetite? If you are a healthy adult, you may be able to help researchers at Fred Hutch answer these important…

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Explainable artificial intelligence and microbiome data for food geographical origin: the mozzarella di bufala campana pdo case of study.

- 1 Department of Soil, Plant, and Food Sciences, Faculty of Agricultural Science, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy

- 2 Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Bari, Bari, Italy

- 3 Department of Agriculture, School of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, University of Naples Federico II, Portici, Italy

- 4 Dipartimento Interateneo di Fisica M. Merlin, Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy

The final, formatted version of the article will be published soon.

Select one of your emails

You have multiple emails registered with Frontiers:

Notify me on publication

Please enter your email address:

If you already have an account, please login

You don't have a Frontiers account ? You can register here

Identifying the origin of a food product holds paramount importance in ensuring food safety, quality, and authenticity. Knowing where a food item comes from provides crucial information about its production methods, handling practices, and potential exposure to contaminants. Machine learning techniques play a pivotal role in this process by enabling the analysis of complex data sets to uncover patterns and associations that can reveal the geographical source of a food item.This study aims to investigate the potential use of explainable artificial intelligence for identifying the food origin. The case of study of Mozzarella di Bufala Campana PDO has been considered by examining the composition of the microbiota in each samples. Three different supervised machine learning algorithms have been compared and the best classifier model is represented by Random Forest with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) value of 0.93 and the top accuracy of 0.87. Machine learning models effectively classify origin, offering innovative ways to authenticate regional products and support local economies. Further research can explore microbiota analysis and extend applicability to diverse food products and contexts for enhanced accuracy and broader impact.

Keywords: Explainable artificial intelligence, machine learning, microbiome, Food origin, PDO

Received: 28 Feb 2024; Accepted: 13 May 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Magarelli, Novielli, De Filippis, Magliulo, Di Bitonto, Diacono, Bellotti and Tangaro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Sabina Tangaro, Department of Soil, Plant, and Food Sciences, Faculty of Agricultural Science, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, 70121, Italy

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Apply to UMaine

UMaine News

Food waste study co-authored by umaine researchers highlighted by the county.

The County highlighted a food waste study from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and aided by the University of Maine, Resource Recycling Systems in Michigan and the Center for EcoTechnology in Massachusetts. Researchers analyzed food waste from residences, farms, grocery stores, schools, hospitals, jails and hotels, among other places. Agricultural based research focused on surplus apples, blueberries, corn and potatoes and used data from the UMaine George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions.

- UMaine Today Magazine

- Submit news

- Open access

- Published: 11 May 2024

Natural approach of using nisin and its nanoform as food bio-preservatives against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and E.coli O157:H7 in yoghurt

- Walaa M. Elsherif 1 , 2 ,

- Alshimaa A. Hassanien 3 ,

- Gamal M. Zayed 2 , 4 &

- Sahar M. Kamal 5

BMC Veterinary Research volume 20 , Article number: 192 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

91 Accesses

Metrics details

Natural antimicrobial agents such as nisin were used to control the growth of foodborne pathogens in dairy products. The current study aimed to examine the inhibitory effect of pure nisin and nisin nanoparticles (nisin NPs) against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and E.coli O157:H7 during the manufacturing and storage of yoghurt. Nisin NPs were prepared using new, natural, and safe nano-precipitation method by acetic acid. The prepared NPs were characterized using zeta-sizer and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In addition, the cytotoxicity of nisin NPs on vero cells was assessed using the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of nisin and its nanoparticles were determined using agar well-diffusion method. Further, fresh buffalo’s milk was inoculated with MRSA or E.coli O157:H7 (1 × 10 6 CFU/ml) with the addition of either nisin or nisin NPs, and then the inoculated milk was used for yoghurt making. The organoleptic properties, pH and bacterial load of the obtained yoghurt were evaluated during storage in comparison to control group.

The obtained results showed a strong antibacterial activity of nisin NPs (0.125 mg/mL) against MRSA and E.coli O157:H7 in comparison with control and pure nisin groups. Notably, complete eradication of MRSA and E.coli O157:H7 was observed in yoghurt formulated with nisin NPs after 24 h and 5th day of storage, respectively. The shelf life of yoghurt inoculated with nisin nanoparticles was extended than those manufactured without addition of such nanoparticles.

Conclusions

Overall, the present study indicated that the addition of nisin NPs during processing of yoghurt could be a useful tool for food preservation against MRSA and E.coli O157:H7 in dairy industry.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Using of bacteriocins such as nisin alone or combined with other natural materials such as essential oils, could be represented as a useful candidate for improving the microbiological quality and maintaining the sensory properties of milk and milk products [ 1 , 2 ]. The utility of nisin as a bio preservative in food industry has been approved and this bacteriocins was effective enough to extended shelf life in regions with inadequate preservation facilities such as developing countries [ 3 ]. Nisin is a natural water-soluble antibacterial peptide (AMP) composed of 34 amino acid residues produced by Lactococcus lactis. It has the ability to inhibit the growth of some foodborne pathogens and many of Gram-positive spoilage bacteria [ 4 , 5 ]. This antibacterial peptide is generally regarded as a safe food preservative by the joint Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization (FAO/WHO), also by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [ 6 , 7 ]. Based on aforementioned permissions, it is widely commercialized as a safe and natural food preservative in the food industry in more than 50 countries around the world [ 8 ].

The antibacterial activity of nisin in food is depending on several factors such as its solubility, pH and structural properties of target bacteria. It could exhibit potent antimicrobial activities against many species of Gram-positive pathogens, while it has little effect against Gram-negative bacteria, yeast and fungi due to their outer membrane barriers [ 9 ]. The exact antibacterial mechanism of nisin is attributed to the passage of nisin through the cell wall of bacteria and its interaction with lipid II, which considered as an essential element in the bacterial cell wall [ 9 ].

There are some obstacles that can hinder the antimicrobial efficacy of free nisin as a food bio preservative such as its ability to interact with food components (e.g. proteolytic enzymes, phospholipids, fatty acids and proteins), high pH and many other food additives. These factors could drastically reduce or completely diminish the antimicrobial effect of nisin [ 10 ]. Hence, different strategies were developed to improve the preservative efficacy of nisin such as liposomes [ 11 ] and nanoparticles [ 12 ]. However, these reported techniques are not suitable for applications in food industries due to the utility of inorganic solvents and chemical compounds, in addition to they are expensive and complicated. For these reasons, alternative organic chemicals and solvents or green synthesized nanoparticles were developed to overcome the inactivation of free nisin by many food components through protecting nisin and releasing it in sustained manner [ 13 ]. For instance, acetic acid, a well-known biocompatible organic acid, has no adverse effects, no dietary restrictions and it is generally recognized as a safe food additive. This organic acid is commonly used, as a natural preservative, in the preservation of food especially in cheese and dairy products where it inhibit the development of bacteria, yeast and fungi [ 14 , 15 ]. Besides acetic acid, tween 80 has a great potential to stabilize nanoparticles dispersion through formation of a protective coat around the nanoparticles, so it was used in food without adverse health effect [ 16 , 17 ].

Application of nisin in dairy industry was reported in more than 55 countries due to its prominent antimicrobial, technological characteristics, safety, stability and flavorless. Commercially, nisin was used in several food matrices to ensure safety, extend shelf life, and to improve the microbial quality either through addition of nisin directly in its purified form or through its production in situ by live bacteria [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. For instance, nisin was added as a bio-preserving ingredient in some kinds of cheese [ 21 , 22 , 23 ], skim milk and whole milk [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Nisin has a potent antibacterial effect against spore-forming bacteria that are the main spoilage concerns in the food industry [ 26 ]. However, several factors such as neutral pH [ 4 ], Fat% [ 25 ], protein% [ 28 ] as well as calcium and magnesium concentrations that can reduce the antimicrobial efficacy of nisin were reported when used directly in dairy foods [ 15 , 29 , 30 ]. Certain previously reported strategies, such as encapsulation and nano-encapsulation of nisin, were applied to increase the antimicrobial efficacy of nisin in dairy industry [ 31 , 32 ]. . Importantly, there is no available data about the use of nisin or nisin NPs as antimicrobial agents during yoghurt preparation.

Accordingly, the current study was designed to prepare nisin NPs by simple nanoprecipitation technique using natural, biocompatible and safe materials. Also the aims of this study were extended to investigate the antibacterial effect of obtained nanoparticles on MRSA and E.coli O157:H7 during manufacturing and storage of yoghurt. Additionally, the effect of the used nisin NPs on the organoleptic properties of yoghurt was addressed.

Materials and methods

Acetic acid (Merck Co., Germany), nisin (Sigma Aldrich from Lactococcus lactis , potency ≥ 900 IU/mg, purity ≥ 95%, CAS Number 1414-45-5), Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) (BBL 11,407, USA), phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) were purchased and used as received. Polyethylene glycol sorbitan monooleate (Tween 80) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Additionally, Mueller Hinton agar (M173) was purchased from HiMedia (Pvt., India), and LAB204 Neogen Company. While, 0.5 McFarland Standard (8.2 log 10 CFU/ml) (Cat. No. TM50) was purchased from Dalynn Biologicals Co. The deionized water was obtained from the Molecular Biology Unit, Assiut University, Egypt.

Preparation of nisin nanoparticles

Nisin (2 mg/mL) was completely dissolved in 100 mL of 0.1 M aqueous acetic acid solution with the aid of sonication using cold probe sonication (UP100H Hielscher Ultrasound). Then, 50 mL of deionized distilled water was gradually added to the nisin solution while maintaining the pH value within the range of 2.5 to 3. Further, 0.01% tween 80 was added as a stabilizer and the mixture was constantly stirred at 25 oC for 7 h to eliminate acetic acid as much as possible. Finally, the nanoparticles suspensions were then sonicated for 5 min before stored at refrigerator temperature for further use. The obtained nanoparticles were examined for size, shape, antibacterial activity and stability after six months.

Characterization of the prepared nisin NPs

Dynamic light scattering (dls).

The prepared nanoparticles was characterized by DLS at a fixed scattered angle of 90° using a Zetasizer, ZS 90 (3000 HS, Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) at the Nanotechnology Unit, Al-Azhar University at Assiut, Egypt. Measurements were taken at 25 °C and Zetasizer® software (version 7.03) was used to collect and analyze the data [ 33 ].

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR was performed at the Chemistry Department at the Faculty of Science, Assiut University. This experiment was used to identify the functional groups and the fingerprint of the molecule. Samples were prepared by compressing potassium bromide with either free nisin or NNPs into small discs. The produced discs were then scanned using FTIR spectrometer (FTIR, NICOLET, iS10, Thermo Scientific) in the wave number ranged from of 4000 to 500 cm − 1 [ 34 ].

High resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM)

The morphology of the prepared nisin NPs was determined using HRTEM (JEM2100, Jeol, Japan) at the Electronic Microscope Unit, National Research Center, Egypt. The sample was diluted with deionized water, and a small drop of nisin NPs was dropped onto 200-mesh copper coated grids at room temperature and negatively stained with uranyl acetate for 3 min. Excess liquid was removed using Whatman filter paper and samples were dried at room temperature [ 35 ].

Bacterial strains and inoculum preparation

The tested pathogens (MRSA and E. coli O157:H7) were previously isolated from dairy products (milk, cheese and yoghurt) samples by culture method and identified using conventional biochemical method and PCR at a certified food lab, Animal Health Research Institute (AHRI), Egypt [ 36 , 37 ]. These isolates were inoculated in trypticase soy broth (Himedia, India) and incubated at 37˚C for 24 h, then co-cultured on selective agars such as MRSA agar base (Acumedia, 7420, USA) and Sorbitol MaCconkey agar (Himedia, India) [ 38 , 39 ] for MRSA and E. coli O157:H7, respectively. The isolates were inoculated in BHI broth and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h until turbidity was comparable to a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard. Before inoculating bacteria in milk, the inoculum was washed twice in PBS and then re-suspended in skim milk.

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of free nisin and nisin nanoparticles against MRSA and E. Coli O157:H7

To determine the MIC of nisin NPs against MRSA and E.coli O157:H7, the agar well diffusion method was used according to Suresh et al. [ 40 ] with minor modifications. In brief, 0.1 mL of the previously prepared bacterial suspensions was spread on Mueller Hinton agar plates and left for 10 min to be absorbed. Then, 8 mm wells were punched into the agar plates for testing the antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles. One-hundred µl of different concentrations of free nisin and nisin NPs (from 0.0313 mg/mL to 2 mg/mL) were poured onto the wells. One well in each plate contained 100 µL of sterile deionized water was kept as a negative control. After overnight incubation at 35 ± 2 °C, the diameters of the inhibition zones were observed and measured in mm [ 41 ]. Each concentration was performed in triplicate.

Assessment of nisin nanoparticles cytotoxicity

The biocompatibility and the cytotoxicity of the nisin NPs were evaluated using a MTT assay against a Vero cell line after culture at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO 2 in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum. The cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 10 4 cells/well overnight before treatment. Different dilutions (0.5×MIC, MIC, 2×MIC, 4×MIC) of optimized nisin NPs were added to the seeded cells. Cells without nanoparticles served as control group. After 72 h, the consumed media was replaced with phosphate buffered saline, 10 µL from 12 mM MTT stock solution was added to each well and cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Next, 50 µL DMSO was added to dissolve formazan crystals and then the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a BMG LABTECH®-FLUO star Omega microplate reader (Ortenberg, Germany). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Antibacterial efficacy of the free nisin and nisin NPs against MRSA and E. Coli O157:H7 during manufacturing and storage of yoghurt

Fresh milk was heated at 85 °C for 5 min in water bath then suddenly cooled. The prepared inoculums were added to the warmed milk (41 ºC) in a count of 10 6 CFU/mL. The inoculated milk was divided into four parts for further use as following, part 1 is the positive control (contained MRSA or E. coli O157:H7 only, one jar each), part 2 (contained MRSA or E. coli O157:H7 with nisin NPs at MIC and 2×MIC, two jars each), part 3 (contained MRSA or E. coli O157:H7 with free nisin at MIC and 2×MIC, two jars each) and part 4 (negative control; free from pathogens and contained free nisin or nisin NPs only, one jar each). After inoculation of the different treatments, yoghurt was manufactured according to Sarkar [ 42 ] by adding 2% yoghurt starter culture ( Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus ) at 41 °C to milk. The prepared yoghurt was placed in a constant-temperature incubator at 40 °C until pH reached 4.6 to 4.5. Finally, the obtained products were stored at refrigeration temperature (4 ± 1 °C) for 5 days. Samples were collected just after manufacturing of yoghurt and every 2 days during storage, then tested for the count of MRSA using MRSA agar base media [ 43 ], and E. coli O157:H7 using Sorbitol MacConkey (SMAC) agar plates [ 44 ]. In addition, pH values were determined in the examined samples as previously described by Igbabul et al. [ 45 ]. In brief, 10 g o f yoghurt sample was dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water. The mixture was left to equilibrate at room temperature. Then, the pH of the samples was then measured by a pH meter (Microprocessor pH meter, pH 537, WTW, Germany).

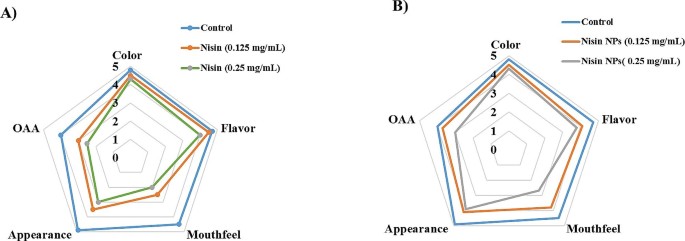

Organoleptic assay of manufactured yogurt

Pathogen-free yoghurt jars (negative control) were prepared with two concentrations of either free nisin or nisin NPs (MIC and 2×MIC) as previously mentioned to be used for organoleptic evaluation. Thirty-five panelists were selected in teams of different ages, sex and education. The perception of consumers toward samples with two concentrations of nisin NPs was recorded. Consumers were asked to evaluate the color, flavor, mouth feel, appearance, and overall acceptability (OAA) of the prepared yoghurt samples containing nisin NPs [ 46 ]. The scale points were excellent (5); very good (4); good (3); acceptable (2); and poor (1).

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using the SPSS program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, 18) to determine the statistical significance of differences between groups. Results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The microbiological and cytotoxicity assay data were prepared using Excel software version 2017. While, the FTIR results were performed using Origin Lab 2021 for graphing and analysis. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Characterization of the prepared nanoparticles

The freshly prepared nisin NPs had 26.55 nm size and PDI 0.227 as determined by zetasizer. While, the diameter of the same after 6 months at refrigeration temperature was 86.50 nm with a PDI equal to 0.431 (Table 1 ). These results indicated that reasonable small-sized particles of nisin were obtained by precipitation technique using acetic acid. The small size of the prepared particles and the small PDI range (from 0.2 to 0.4) indicated a mono size dispersion and a good stability of the prepared nisin NPs.

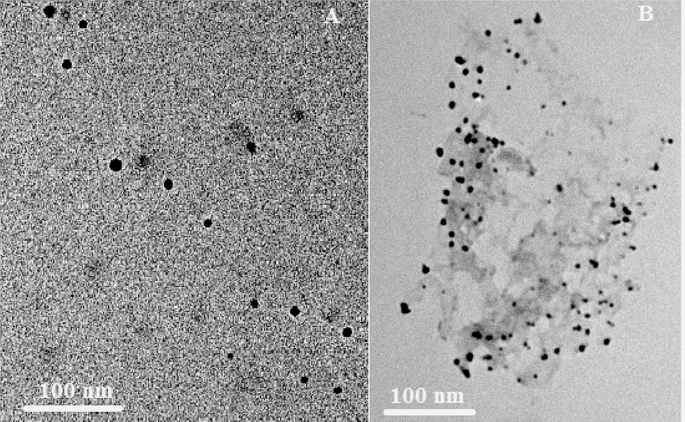

The size and morphology of the freshly prepared nisin NPs and after 6 months of storage were measured by HRTEM are presented in Fig. 1 . Both freshly prepared and stored nisin NPs were approximately uniform in size with adequate distribution of particles. The shape of the particles was nearly spherical with slightly a bit of agglomeration just after 6 months of storage. The average size of freshly prepared nisin NPs was 7.35 nm while, after 6 months was 15.4 nm. The size of particles determined by TEM is usually smaller than the dynamic particles determined by zeta-sizer because TEM determine the actual particle diameter while zeta-sizer determine the particles diameter with adjacent moving layers of solvents.

The TEM images of freshly prepared nisin NPs (A) and after 6th months of storage (B)

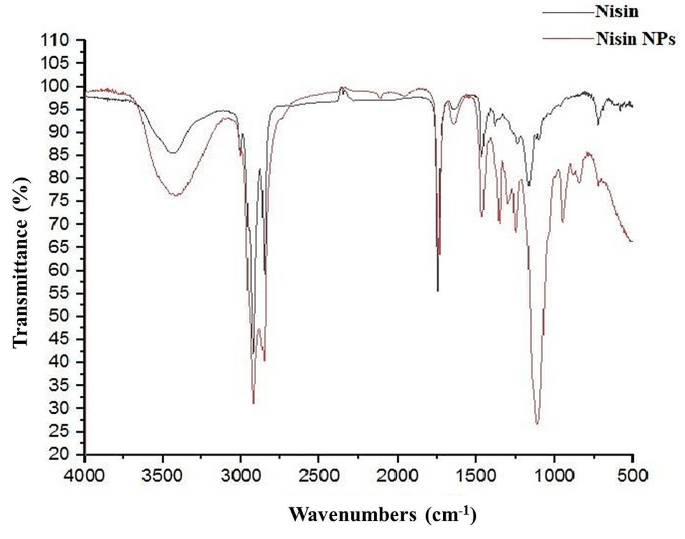

Figure 2 showed the FTIR of pure and nisin NPs; both spectrum showed the characteristic peaks of nisin at 3425, 1599 and 1493 cm − 1 corresponded to O-H stretching of COOH, C = O stretching of amide I and N-H bending amide II. Bands 1530 cm − 1 in free nisin indicated the stretching of amid II and which, increased to 1549 cm − 1 in nisin NPs that indicated increase the H- bond in nano form than free one. The results of FTIR spectrum confirmed that the formation of nisin NPs did not result in any chemical changes or interaction of nisin with used the materials. These results also demonstrated the suitability of the applied method for the preparation of chemically stable and small-sized nisin NPs.

The FTIR of pure nisin and nisin NPs

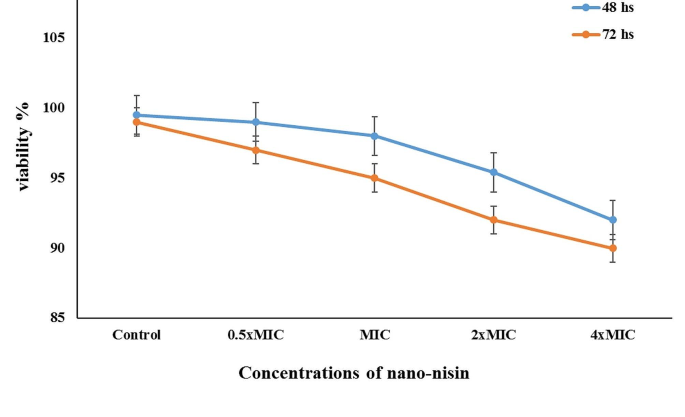

Assessment of Nisin nanoparticles cytotoxicity

In the present study, Veros cells were exposed to nisin NPs for 48 and 72 h, and the cytotoxicity was measured by MTT assays. Results showed that the MIC did not exhibit an anti-proliferation effect (Fig. 3 ). Interestingly, even at very high concentrations (4xMIC), there were no cytotoxicity effect as the percentage of viable cells reach 92% and 89.98% after 48 and 72 h, respectively. The obtained findings confirmed the safety and good biocompatibility of the prepared nisin NPs at MIC level.

Cytotoxicity and cell viability of different concentrations nisin NPs using Vero cells after 48 and 72 h using MTT assay

MIC of free nisin and nisin NPs against MRSA and E. Coli O157:H7

The efficacy of the free nisin and prepared nisin NPs against MRSA and E. coli O157:H7 was investigated using agar well diffusion assay (Table 2 ). Nisin and its nanoparticles showed potent antibacterial effect against MRSA than E. coli O157:H7. The MICs of nisin and nisin NPs toward MRSA were 0.0625 and 0.0313 mg/mL, respectively. While, 0.125 mg/mL was the MIC of both nisin and nisin NPs against E. coli O157:H7. Of note, growth inhibition zone was not observed against MRSA at 0.0313 mg/mL of nisin, and toward E. coli O157:H7 at both 0.0625 and 0.0313 mg/mL nisin (Table 2 ). On the other hand, the prepared nisin NPs could produce inhibition zones against MRSA with a mean diameter ranged from 25.4 ± 2.1 mm to 7.1 ± 0.89 mm at concentrations of 2 to 0.0313 mg/mL, respectively. Also, the nisin NPs showed anti- E. coli O157:H7 activity at different concentrations of 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.125 mg/mL with average size of 20.1, 15.4, 12.7, 9.5 and 7.2 mm of the inhibitory zones, respectively. There were no inhibition zones against E. coli O157:H7 at 0.0625 and 0.0313 mg/mL of nisin NPs. Overall, the obtained findings indicated that the most effective MICs of nisin and nisin NPs for both organisms were 0.125 mg/mL (Table 2 ).

Antibacterial effect of nisin and nisin NPs against MRSA and E. Coli O157:H7 during manufacturing and storage of yoghurt

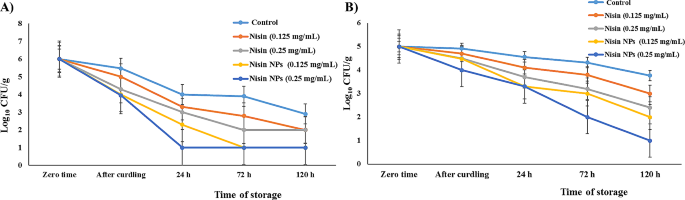

Figure 4 presented the antibacterial activity of nisin against the examined foodborne pathogens (MRSA and E. coli O157:H7). Here, nisin at 0.125 and 0.25 mg/ml could induce antibacterial effect against MRSA (3.3 and 3 log 10 CFU/g, respectively) after 24 h of yoghurt storage. However the effect was not higher as in case of nisin NPs (2.3 and 1 log 10 CFU/g) at the same concentrations and time of storage. While, the inhibitory impact of the free nisin on E. coli O157:H7 was observed after 24 h (3.7 log 10 CFU/g) and 3 days (3.8 log 10 CFU/g) of storage at the concentrations of 0.25 and 0.125 mg/mL, respectively. The pathogens were still detected till the end of the experiment in nisin treated yoghurt (Fig. 4 ).

Antibacterial effect of free nisin (A) and nisin NPs (B) on MRSA and E.coli O157:H7 during manufacturing and storage of yoghurt

On the other hand, there was a clear reduction in mean count of MRSA and E.coli O157:H7 in the laboratory-manufactured yoghurt supplemented with different concentrations (0.125 and 0.25 mg/mL) of nisin NPs. A complete inhibition of MRSA was observed after 24 h and at the 3rd day of storage by 0.25 and 0.125 mg/mL of nisin NPs, respectively (Fig. 5 ). While, E. coli O157:H7 was undetectable at the 5th day of storage with 0.25 mg/mL nisin NPs, however it was still detected till the end of the experiment in either yoghurt inoculated with 0.125 mg/mL nisin NPs or in the positive control group (Fig. 4 ). Taken together, the antimicrobial count tests revealed that the free nisin is not effective as the nisin NPs at same time points during processing and storage of yoghurt.

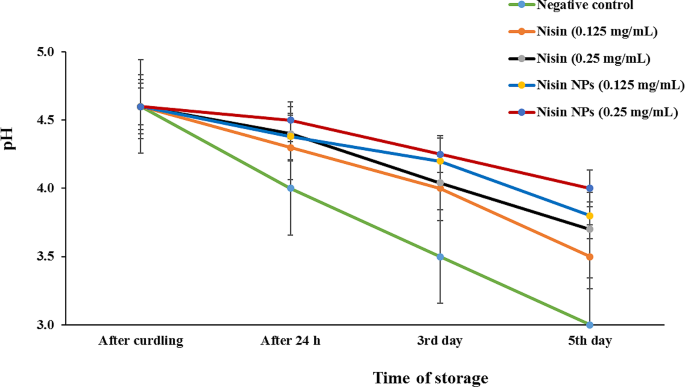

During storage, the pH did not change significantly between different treatments. However, the negative control group showed little decrease in pH in comparison to other groups at the 3rd and 5th day of storage (3.5 and 3, respectively).

Evaluation of pH levels during processing and storage of yoghurt inoculated with different concentrations of free nisin or nisin NPs

Organoleptic evaluation of the laboratory-manufactured yoghurt

Figure 6 clarified that there was no difference in the sensory properties between the different groups (contained 0.125 or 0.25 mg/mL nisin (Fig. 6A) or nisin NPs (Fig. 6B)) in comparison to the control group. The OAA of yoghurt inoculated with 0.125 mg/mL and 0.25 mg/mL of free nisin was 3 and 2.5, respectively (Fig. 6A). While, the control samples had the highest score in mouth feel (4.5), followed in order with yoghurt loaded with 0.125 mg/mL and 0.25 mg/mL nisin NPs (3.8 and 2.7, respectively). Additionally, the overall acceptability (OOA) of control, 0.125 mg/mL and 0.25 mg/mL nisin NPs groups was 4, 3.7 and 3, respectively (Fig. 6B). Such findings indicated the high acceptability of yoghurt containing different concentrations of nisin NPs than those inoculated with free nisin.

Organoleptic properties of yoghurt inoculated with different concentrations of free nisin and nisin NPs

The current study elucidated for the first time the inhibitory effect of free nisin and nisin NPs on two of the most common foodborne pathogens (MRSA and E. coli O157:H7) during processing and storage of laboratory manufactured yoghurt. Strikingly, adding of nisin NPs to yoghurt could induce much higher antibacterial effect on MRSA and E. coli O157:H7 with high consumer acceptability than free nisin. Accordingly, nisin NPs could be a useful and effective bio-preservative candidate against MRSA and E. coli O157:H7 in dairy industry.

The present study revealed that nisin NPs was prepared by a novel and safe method using natural material such as acetic acid which is commonly applied in food products. Chang et al. [ 47 ]. prepared ultra-small sizes of nisin NPs by nanoprecipitation method using HCL while we obtained much smaller particle size of NNPs using acetic acid which is more safer, less toxic and accepted by consumers. The particle size determined by TEM is smaller than the size measured by DLS this difference could be attributed to the removal of solvent and shrinking of nanoparticles during the drying of nisin NPs samples for TEM investigations. In addition, DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter of the dispersed moving particles with the surrounding moving layers of solvents [ 48 , 49 ].

The result of FTIR was in consistent with that of Flynn et al. [ 50 ]. Herein, we found that the -OH stretching peak of nisin NPs displayed a greater intensity than that of free nisin, which indicated a stronger hydrogen bonding formation within nisin NPs. In case of free nisin, the peak at 1620 cm − 1 corresponding to COO − was shifted to 1610 cm − 1 in nisin NPs indicating that the hydrogen bonding was increased within nisin NPs. In contrast, the amid II band in free nisin appeared at 1530 cm − 1 became more obvious at 1549 cm − 1 in nisin NPs which was in agreement with Webber et al. [ 51 ]. . Band of amide I at wave number of 1632 cm − 1 could be due to the change in the structure of free nisin when converted into nisin NPs by using natural acetic acid.

In food chain, nisin has been approved for use in over 50 countries due to its safety and its potent antimicrobial activity without inducing microbial resistance [ 52 ]. Of particular note, the FAO/WHO Codex Committee and US FDA allow using nisin as a food additive in dairy products at a concentration up to 250 mg/kg [ 1 , 53 ]. Moreover, European Food Safety Authority [ 54 ] reported that nisin has been shown to be non-toxic to humans and it is safe as a food preservative for dairy and meat products. In the current study, the examined organisms (MRSA and E. coli O157:H7) have been involved in many food outbreaks worldwide as well as their resistance to many antibiotics, considered a challenge to be controlled [ 55 , 56 , 57 ]. Therefore, the present study could be a useful alternative strategy to avoid the possible health hazards of these organisms after consumption of yoghurt using either nisin or nisin NPs as natural food preservatives.

The obtained results revealed that the MICs of nisin and nisin NPs against MRSA were lower than that of E. coli O157:H7. This could be due to the ability of nisin to penetrate the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria, however, it is difficult for nisin to penetrate the outer membrane barrier of Gram-negative bacteria [ 58 ]. Nisin could destroy bacteria through two mechanisms, either by making pores in the plasma membrane or by inhibiting the cell wall biosynthesis through binding to lipid II [ 59 , 60 , 61 ]. Importantly, the obtained results in the current study showed that that MIC of nisin NPs against MRSA was lower than that of pure nisin. Similarly, Zohri et al. [ 62 ] reported that the MICs of nisin and Nisin-Loaded nanoparticles was 2 and 0.5 mg/mL after 72 h of incubation period with the S. aureus samples, respectively. In addition, Moshtaghi et al. [ 63 ] examined the antibacterial effect of nisin on S. aureus and E. coli at different pH values and they found that the MICs against S. aureus were ranged from 19 to 312 µg/mL of nisin at pH levels from 8 to 5.5, respectively. While for E. coli , the MICs were from 78 to 1250 µg/mL at the same range of pH, respectively [ 63 ].

Interestingly, nisin inhibited the pathogenic foodborne bacteria and many other Gram-positive food spoilage microorganisms [ 13 ]. In the present study, evaluation of the kinetic growth of MRSA and E. coli O157:H7 based on the total counts in the laboratory manufactured yoghurt revealed that nisin NPs was able to inhibit more effectively the growth of such foodborne pathogens than free nisin during manufacturing and storage of yoghurt. These findings were in concurrent with those obtained by Zohri et al. [ 62 ] who demonstrated that nisin-loaded chitosan/alginate nanoparticles showed more antibacterial effect than free nisin on the growth of S. aureus in raw and pasteurized milk samples. Additionally, nisin Z in liposomes can provide a powerful tool to improve nisin stability and inhibitory action against Listeria innocua in the cheddar cheese [ 64 ]. In our study, nisin NPs showed a complete inhibition of MRSA after curdling of yoghurt and reduced the survivability of E. coli O157:H7 when applied at two different concentrations during storage of such product. Nisin NPs with high specific surface area could be easily attached to the target cell surface leading to increased permeability of the cell membrane, and finally cause bacterial cell death. Furthermore, nisin NPs were thermo-tolerant because of the internal non-covalent interactions in the nanoparticles [ 4 , 65 ]. Additionally, the decline in the mean count of the examined pathogens (MRSA and E.coli O157: H7) in the current study may be due to the effect of low pH (high acidity) of yoghurt that leads to shrinkage and death of the bacterial cells [ 66 ]. Similarly, Al-Nabulsi et al. [ 67 ] reported that the combination of a starter culture, low temperature, and pH ( ∼ 5.2) had inhibitory effects on the growth of S. aureus .

The effect of adding different levels of nisin and nisin NPs on OAA scores of yoghurt was recorded and the obtained results were in agreement with Hussain et al. [ 68 ], Radha [ 3 ], and Gharsallaoui et al. [ 4 ] who reported that a Nigerian fermented milk product had acceptable sensory scores till 25th day of storage when loaded with nisin at 400 IU/mL. Additionally, Chang et al. [ 47 ] said that the thermal treatments are known to cause undesirable changes in the sensory, nutritional and/or technological properties of milk. Taking advantage of the antimicrobial action of nisin NPs against several spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms, this innovative non-thermal food preservative offers the inactivation of microorganisms with minimal impact on the quality, safety, nutritional values and acceptability of dairy products.

Overall, as the demand for preservative-free food products increased, natural antimicrobials have gained more and more attention because of their effectiveness and safety. Consequently, the current study investigated that the addition of nisin NPs to milk for manufacturing of yoghurt can be used as an innovative preventive measure to inhibit the contamination with foodborne pathogens. However, further researches are required to determine the effective and safe dose of nisin NPs for application in other dairy products.

The present study prepared nisin NPs using acetic acid by precipitation method and the obtained particles were small in size with good stability and consumer acceptability. The antibacterial effect of nisin and nisin NPs against MRSA and E. coli O157:H7 in yoghurt was impressive. Additionally, the studied nanoparticles did not affect the sensory and textural characteristics of the finished product. Hence, this study could be useful for yoghurt makers and dairy products factories through using this novel preservation technology to inhibit the growth of MRSA and E. coli O157:H7, in yoghurt and dairy products, and subsequently avoid food spoilage and foodborne diseases.

Data availability

All data and materials are available here in the current study.

Ibarra-Sánchez LA, El-Haddad N, Mahmoud D, Miller MJ, Karam L. Invited review: advances in nisin use for preservation of dairy products. J Dairy Sci. 2020;103(3):2041–52.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Batiha G, Hussein DE, Algammal A, George T, Jeandet P, Al-Snafi A, Tiwari A, Pagnossa J, Gonçalves Lima CM, Thorat N et al. Application of Natural antimicrobials in Food Preservation: recent views. Food Control 2021, 126.

Radha K. Nisin as a biopreservative for pasteurized milk. Indian J Veterinary Anim Sci Res. 2014;10(6):436–44.

Google Scholar

Gharsallaoui A, Oulahal N, Joly C, Degraeve P. Nisin as a Food Preservative: part 1: Physicochemical Properties, Antimicrobial Activity, and Main uses. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56(8):1262–74.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gao S, Zhai X, Cheng Y, Zhang R, Wang W, Hou H. Starch/PBAT blown antimicrobial films based on the synergistic effects of two commercial antimicrobial peptides. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;204:457–65.

FDA/HHS. Direct food substances affirmed as generally recognized as safe: nisin preparation. Fed Regulations. 1988;53:11247–51.

Thomas LV, Clarkson MR, Delves-Broughton J. In A. S. Naidu, editor, Nisin: Natural food antimicrobial systems (Florida, Boca Raton: CRC) 2000:Press, 463–524.

Pimentel-Filho Nde J, Martins MC, Nogueira GB, Mantovani HC, Vanetti MC. Bovicin HC5 and Nisin reduce Staphylococcus aureus adhesion to polystyrene and change the hydrophobicity profile and Gibbs free energy of adhesion. Int J Food Microbiol. 2014;190:1–8.

Thébault P, Ammoun M, Boudjemaa R, Ouvrard A, Steenkeste K, Bourguignon B, Fontaine-Aupart M-P. Surface functionalization strategy to enhance the antibacterial effect of nisin Z peptide. Surf Interfaces. 2022;30:101822.

Article Google Scholar

Liu G, Nie R, Liu Y, Mehmood A. Combined antimicrobial effect of bacteriocins with other hurdles of physicochemic and microbiome to prolong shelf life of food: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2022;825:154058.

Brum LFW, Dos Santos C, Zimnoch Santos JH, Brandelli A. Structured silica materials as innovative delivery systems for the bacteriocin nisin. Food Chem. 2022;366:130599.

Kazemzadeh S, Abed-Elmdoust A, Mirvaghefi A, Hosseni Seyed V, Abdollahikhameneh H. Physicochemical evaluations of chitosan/nisin nanocapsulation and its synergistic effects in quality preservation in tilapia fish sausage. J Food Process Preserv. 2022;46(3):e16355.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Elsherif W, Zeinab A-E. Effect of nisin as a biopreservative on shelf life of pasteurized milk. Assiut Veterinary Med J. 2019;65:1–24.

Hu Y, Wu T, Wu C, Fu S, Yuan C, Chen S. Formation and optimization of chitosan-nisin microcapsules and its characterization for antibacterial activity. Food Control. 2017;72:43–52.

Khan I, Oh D-H. Integration of nisin into nanoparticles for application in foods. Innovative Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2016;34:376–84.

Zhao Y, Wang Z, Zhang W, Jiang X. Adsorbed Tween 80 is unique in its ability to improve the stability of gold nanoparticles in solutions of biomolecules. Nanoscale. 2010;2(10):2114–9.

Bekhit M, Abu el-naga MN, Sokary R, Fahim RA, El-Sawy NM. Radiation-induced synthesis of tween 80 stabilized silver nanoparticles for antibacterial applications. J Environ Sci Health Part A. 2020;55(10):1210–7.

Cui HY, Wu J, Li CZ, Lin L. Anti-listeria effects of chitosan-coated nisin-silica liposome on Cheddar cheese. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99(11):8598–606.

Kondrotiene K, Kasnauskyte N, Serniene L, Gölz G, Alter T, Kaskoniene V, Maruska AS, Malakauskas M. Characterization and application of newly isolated nisin producing Lactococcus lactis strains for control of Listeria monocytogenes growth in fresh cheese. LWT. 2018;87:507–14.

Santos JCP, Sousa RCS, Otoni CG, Moraes ARF, Souza VGL, Medeiros EAA, Espitia PJP, Pires ACS, Coimbra JSR, Soares NFF. Nisin and other antimicrobial peptides: production, mechanisms of action, and application in active food packaging. Innovative Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2018;48:179–94.

Van Tassell ML, Ibarra-Sánchez LA, Takhar SR, Amaya-Llano SL, Miller MJ. Use of a miniature laboratory fresh cheese model for investigating antimicrobial activities. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98(12):8515–24.

Ibarra-Sánchez LA, Van Tassell ML, Miller MJ. Antimicrobial behavior of phage endolysin PlyP100 and its synergy with nisin to control Listeria monocytogenes in Queso Fresco. Food Microbiol. 2018;72:128–34.

Feng Y, Ibarra-Sánchez LA, Luu L, Miller MJ, Lee Y. Co-assembly of nisin and zein in microfluidics for enhanced antilisterial activity in Queso Fresco. LWT. 2019;111:355–62.

Jung D-S, Bodyfelt FW, Daeschel MA. Influence of Fat and emulsifiers on the efficacy of Nisin in inhibiting Listeria monocytogenes in Fluid Milk1. J Dairy Sci. 1992;75(2):387–93.

Bhatti M, Veeramachaneni A, Shelef LA. Factors affecting the antilisterial effects of nisin in milk. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;97(2):215–9.

Saad MA, Ombarak RA, Abd Rabou HS. Effect of nisin and lysozyme on bacteriological and sensorial quality of pasteurized milk. J Adv Veterinary Anim Res. 2019;6(3):403–8.

Chen H, Zhong Q. Lactobionic acid enhances the synergistic effect of nisin and thymol against Listeria monocytogenes Scott A in tryptic soy broth and milk. Int J Food Microbiol. 2017;260:36–41.

Wirjantoro TI, Lewis MJ, Grandison AS, Williams GC, Delves-Broughton J. The effect of nisin on the keeping quality of reduced heat-treated milks. J Food Prot. 2001;64(2):213–9.

Silva CCG, Silva SPM, Ribeiro SC. Application of Bacteriocins and protective cultures in dairy food preservation. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:594.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Houlihan AJ, Russell JB. The effect of calcium and magnesium on the activity of bovicin HC5 and nisin. Curr Microbiol. 2006;53(5):365–9.

da Silva Malheiros P, Daroit DJ, da Silveira NP, Brandelli A. Effect of nanovesicle-encapsulated nisin on growth of Listeria monocytogenes in milk. Food Microbiol. 2010;27(1):175–8.

Martinez RCR, Alvarenga VO, Thomazini M, Fávaro-Trindade CS, Sant’Ana AS. Assessment of the inhibitory effect of free and encapsulated commercial nisin (Nisaplin®), tested alone and in combination, on Listeria monocytogenes and Bacillus cereus in refrigerated milk. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2016;68:67–75.

Lu P-J, Fu W-E, Huang S-C, Lin C-Y, Ho M-L, Chen Y-P, Cheng H-F. Methodology for sample preparation and size measurement of commercial ZnO nanoparticles. J Food Drug Anal. 2018;26(2):628–36.

Bi S, Ahmad N. Green synthesis of palladium nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 62:3172–3177.

Gruskiene R, Krivorotova T, Staneviciene R, Ratautas D, Serviene E, Sereikaite J. Preparation and characterization of iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles functionalized by nisin. Colloids Surf B. 2018;169:126–34.

Zakaria IM, Elsherif WM. Bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles on methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated from bulk milk tanks. Anim Health Res J. 2018;6(3):42–51.

Elsherif W, Ali DN. Antibacterial effect of silver nanoparticles on antibiotic resistant E. Coli O157:H7 isolated from some dairy products. Bulgarian J Veterinary Med 2020:442.

Bennett RW, Lancette GA. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus in food samples. Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM), Ch. 12./ FoodScience Research /Laboratory Methods/ucm071429htm 2016.

Sancak YC, Sancak H, Isleyici O. Presence of Escherichia coli O157 and O157:H7 in raw milk and Van Herby cheese. Bull Veterinary Inst Pulawy 2015, 59.

Suresh S, Karthikeyan S, Saravanan P, Jayamoorthy K. Comparison of antibacterial and antifungal activities of 5-amino-2-mercaptobenzimidazole and functionalized NiO nanoparticles. Karbala Int J Mod Sci. 2016;2(3):188–95.

Hassanien AA, Shaker EM. Investigation of the effect of chitosan and silver nanoparticles on the antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coliO157:H7 isolated from some milk products and diarrheal patients in Sohag City, Egypt. Veterinary World. 2020;13(8):1647–53.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sarkar S. Effect of Nisin on Techno- logical and microbiological characteristics of stirred Yoghurt. J Microbiol Microb Technol. 2016;1(1):6.

Sivaraman GK, Gupta S, Sivam V, Muthulakshmi T, Elangovan R, Perumal V, Balasubramanium G, Lodha T, Yadav A. Prevalence of S. Aureus and/or MRSA from seafood products from Indian seafood products. BMC Microbiol 2022, 22.

Anyanwu M, Cugwu I, Okorie-Kanu O, Ngwu M, Kwabugge Y, Chioma A, Chah K. Sorbitol non-fermenting Escherichia coli and E. Coli O157: prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profile of strains in slaughtered food animals in Southeast Nigeria. Access Microbiol 2022, 4.

Igbabul B, Hiikyaa O, Amove J. Effect of fermentation on the Proximate Composition and Functional Properties of Mahogany Bean (Afzelia africana) Flour. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci J. 2014;2:01–7.

Lawless H, Heymann H. Sensory Evaluation of Food Science Principles and Practices. Chapter 1, 2nd Edition, Ithaca, New York 2010: https://doi.org/10.1007/1978-1001-4419-6488-1005 .

Chang R, Lu H, Li M, Zhang S, Xiong L, Sun Q. Preparation of extra-small nisin nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial activity after autoclave treatment. Food Chem. 2018;245:756–60.

Jahanshahi M, Babaei Z. Protein nanoparticle: a unique system as drug delivery vehicles. Afr J Biotechnol 2008, 7.

Krivorotova T, Cirkovas A, Maciulyte S, Staneviciene R, Budriene S, Serviene E, Sereikaite J. Nisin-loaded pectin nanoparticles for food preservation. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;54:49–56.

Flynn J, Durack E, Collins MN, Hudson SP. Tuning the strength and swelling of an injectable polysaccharide hydrogel and the subsequent release of a broad spectrum bacteriocin, nisin A. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8(18):4029–38.

Webber JL, Namivandi-Zangeneh R, Drozdek S, Wilk KA, Boyer C, Wong EHH, Bradshaw-Hajek BH, Krasowska M, Beattie DA. Incorporation and antimicrobial activity of nisin Z within carrageenan/chitosan multilayers. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1690.

Shin JM, Gwak JW, Kamarajan P, Fenno JC, Rickard AH, Kapila YL. Biomedical applications of nisin. J Appl Microbiol. 2016;120(6):1449–65.

Sobrino-López A, Martín-Belloso O. Use of Nisin and other bacteriocins for preservation of dairy products. Int Dairy J. 2008;18(4):329–43.

European Food Safety Authority. Opinion of the scientific panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food on a request from the commission related to the use of nisin (E 234) as a food additive. EFSA J. 2005;3146:1–16.

WHO. Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance. Report of an Intercountry Workshop. 2003 Oct 14–17; Tamil Nadu, India 2004.

Titouche Y, Akkou M, Houali K, Auvray F, Hennekinne JA. Role of milk and milk products in the spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the dairy production chain. J Food Sci. 2022;87(9):3699–723.

Eltokhy HE, Abdelsamei HM, El barbary H, Nassif, mZ. Prevalence of some pathogenic bacteria in dairy products. Benha Veterinary Med J. 2021;40(2):51–5.

Li Q, Montalban-Lopez M, Kuipers OP. Increasing the antimicrobial activity of Nisin-based lantibiotics against Gram-negative pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol 2018, 84(12).

Hasper HE, Kramer NE, Smith JL, Hillman JD, Zachariah C, Kuipers OP, de Kruijff B, Breukink E. An alternative bactericidal mechanism of action for lantibiotic peptides that target lipid II. Sci (New York NY). 2006;313(5793):1636–7.

‘t Hart P, Oppedijk SF, Breukink E, Martin NI. New insights into Nisin’s antibacterial mechanism revealed by binding studies with synthetic lipid II analogues. Biochemistry. 2016;55(1):232–7.

Tol MB, Morales Angeles D, Scheffers DJ. In vivo cluster formation of nisin and lipid II is correlated with membrane depolarization. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(6):3683–6.

Zohri M, Alavidjeh MS, Haririan I, Ardestani MS, Ebrahimi SE, Sani HT, Sadjadi SK. A comparative study between the Antibacterial Effect of Nisin and Nisin-Loaded Chitosan/Alginate Nanoparticles on the growth of Staphylococcus aureus in Raw and pasteurized milk samples. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2010;2(4):258–66.

Moshtaghi H, Rashidimehr A, Shareghi B. Antimicrobial activity of Nisin and Lysozyme on Foodborne pathogens Listeria Monocytogenes, Staphylococcus Aureus, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Escherichia Coli at different pH. J Nutrtion Food Secur. 2018;3(4):193–201.

Benech RO, Kheadr EE, Laridi R, Lacroix C, Fliss I. Inhibition of Listeria innocua in cheddar cheese by addition of nisin Z in liposomes or by in situ production in mixed culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68(8):3683–90.

Hegedüs I, Nagy E. Stabilization of activity of hemicellulase enzymes by covering with polyacrylamide layer. Chem Eng Process. 2015;95:143–50.

Normanno G, La Salandra G, Dambrosio A, Quaglia NC, Corrente M, Parisi A, Santagada G, Firinu A, Crisetti E, Celano GV. Occurrence, characterization and antimicrobial resistance of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus isolated from meat and dairy products. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;115(3):290–6.

Al-Nabulsi AA, Osaili TM, AbuNaser RA, Olaimat AN, Ayyash M, Al-Holy MA, Kadora KM, Holley RA. Factors affecting the viability of Staphylococcus aureus and production of enterotoxin during processing and storage of white-brined cheese. J Dairy Sci. 2020;103(8):6869–81.

Hussain SA, Garg FC, Pal D. Effect of different preservative treatments on the shelf-life of sorghum malt based fermented milk beverage. J Food Sci Technol. 2014;51(8):1582–7.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the nanotechnology research and synthesis unit at animal health research institute, Assiut, Egypt for their help in preparation of nanomaterials.

Not applicable.

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Certified Food Lab, Nanotechnology Research and Synthesis Unit, Animal Health Research Institute (AHRI), Agriculture Research Center (ARC), Assiut,, Egypt

Walaa M. Elsherif

Faculty of Health Sciences Technology, New Assiut Technological University (NATU), Assiut, Egypt

Walaa M. Elsherif & Gamal M. Zayed

Department of Zoonoses, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Sohag University, Sohag, Egypt

Alshimaa A. Hassanien

Department of Pharmaceutics and Pharmaceutical Technology, Al-Azhar University, Assiut, Egypt

Gamal M. Zayed

Department of Food Hygiene, Safety and Technology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt

Sahar M. Kamal

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

W.M.E., A.A.H., G.M.Z., and S.M.K. conceived and designed the experiment. W.M.E., A.A.H., G.M.Z., and S.M.K. collected the experimental data. W.M.E., A.A.H., and S.M.K. performed the microbiological analysis. A.A.H. and G.M.Z. performed the preparation and analysis of nanoparticles. W.M.E. and S.M.K. performed the statistical analysis. All authors interpreted the data. W.M.E. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sahar M. Kamal .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Elsherif, W.M., Hassanien, A.A., Zayed, G.M. et al. Natural approach of using nisin and its nanoform as food bio-preservatives against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and E.coli O157:H7 in yoghurt. BMC Vet Res 20 , 192 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-024-03985-1

Download citation

Received : 12 October 2023

Accepted : 21 March 2024

Published : 11 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-024-03985-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- E.coli O157:H7

- Nanoparticles

- Cytotoxicity

- Food preservative

BMC Veterinary Research

ISSN: 1746-6148

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy, Research, Capacity and Influence

Effect of Pesticide Use on Crop Production and Food Security in Uganda

May 14, 2024 - Linda Nakato, Umar Kabanda, Pauline Nakitende, Tess Lallemant & Milu Muyanga

The increasing pest proliferation has continued to cause a serious threat to food security in Uganda. This study explores the impact of pesticide adoption on food security in Uganda. Specifically, it seeks to assess whether the use of pesticides ensures food security, with crop productivity serving as an intervening variable. Employing the control function approach with fixed effects estimation on a dataset comprising 1,656 households spanning the periods 2013/2014, 2016/2015, and 2018/19 to 2019/20 obtained from the Uganda National Panel Survey, the study reveals several determinants influencing pesticide use in Uganda. The findings also highlight that the adoption of pesticides demonstrates a positive influence on crop productivity. However, when assessed through indicators such as Food Consumption Score (FCS), Minimum Acceptable Household Food Consumption (MAHFP), and Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) at the pre-harvest stage, the results do not indicate a statistically significant correlation of pesticide use and food security outcomes. Consequently, beyond enhanced crop productivity and the pre-harvest activities focused on in the study, it is imperative to consider the post-harvest application of pesticides to comprehensively explain how pesticide use effects food security in Uganda. Based on the positive link between pesticides and crop productivity, its recommended that government should increase awareness on and access of insecticides among farmers. Given that insects are the main pests damaging crops in Uganda. It is also important for Uganda to reform and reactive a regulatory framework having a licensing system to regulate private local market dealers’ sale of pesticides. Given that the majority of the households purchase their pesticides from private traders in the local/village market. This approach might improve the quality of pesticide purchased by farmers and, increase pesticide use to diversify produce of more nutritious foods, to ultimately enhance access and nutrient intake per meal in Uganda.

Pesticide use, crop productivity, food security.

DOWNLOAD FILE

Tags: prci research paper

new - method size: 1 - Random key: 0, method: personalized - key: 0

You Might Also Be Interested In

STAAARS+ RFP webinar Sept 14 2022

Published on September 15, 2022

PRCI STAAARS+ Teams Presentation Video 2022

Published on July 26, 2022

Scoping Study of Agriculture Development Strategy of Nepal (ADS) (Five-year achievements)

Published on February 1, 2023

Sugarcane Production and Food Security in Uganda

Published on September 1, 2023

Institutional Arrangements Between Sugarcane Growers and Millers in Uganda and Implications for Grower Productivity and Profitability

Rwanda Natural Forest Cover Dynamics between 2015 and 2020

Published on June 19, 2023

Accessibility Questions: