Gender and Development

- First Online: 22 February 2022

Cite this chapter

- Shelley Feldman 4

330 Accesses

This chapter offers a brief historical overview of research focused on gender relations and practices within nongovernmental organizations (NGO) and state institutions, as well as national policies that have unfolded in Bangladesh. Research in the early years of Bangladesh’s independence focused on rural relations, household and reproductive labor, and the norms of purdah that guided programs and projects that sought to improve women’s lives and livelihoods. With the rise of the garment manufacturing sector in the 1980s, women’s entry into the urban labor market shifted attention to new issues related to the transformation of women’s work within the changing urban landscape and labor market. This new opportunity for women also drew attention to changing household and family relations and women’s increased mobility. Significantly, the garment sector is credited with helping to realize economic growth in the country, where Bangladesh is now positioned as a lower middle-income country, even as women’s central contribution to this effort often goes unremarked.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

This is, arguably, a narrow focus, limited to research that is directly tied to development issues. It does not include the rich and growing literature that offers gender and feminist analyses of, for example, nationalism, international relations, or religion.

UN Development Programme. 2010 Human Development Report: Asian countries lead development progress over 40 years. http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/PR6-HDR10-RegRBAP-E-rev5-sm.pdf

In 1977, the World Bank appointed a Women in Development Adviser and in 1984 mandated that its programs consider women’s issues. Reflecting the shift from WID to GAD, a 1994 policy paper sought to question policy and institutional constraints that maintained gender disparities and limited the effectiveness of development programs.

WID scholars and practitioners, for example, pressured US policy makers to include women in their activities, which resulted in the 1973 Percy Amendment to the US Foreign Assistance Act, requiring USAID’s programs to support efforts to integrate women into their respective national economies. To be clear, this presumed that integration meant, first, recognizing women as members of the body politic, and, second, neither understanding their exclusion nor challenging the development approach that excluded them.

During this period, academic women formed Women for Women , a research and advocacy group that examined women’s education (Islam, 1982 ), health and medical practices (Islam, 1980 , 1985 ), gender violence (Jahan, 1983 , 1988a , 1988b ), and women’s economic position (Huq et al., 1983 ; Jahan, 1975 ).

This was written for Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era (DAWN).

In moral regulation and rule I include critical engagements with the symbolic and practical work that purdah or credit, among other practices, produce, enable, and constrain.

This historicization of gender and development highlights the long-term process of women’s engagement in in-kind and wage work, a concern elided in most research on women yet central to critiques of the assumptions of the WID/WAD/GAD approaches to understanding gender relations. It is also noteworthy that these studies were supported by the Ministries of Agricultural and Local Government and Rural Development and funded with external financial support.

There is a vast literature on micro-credit and finance, far too broad to elaborate here, taking multiple sides in the debate on its value for empowering women or indebting women, focusing on credit or on patriarchy, and examining whether credit decreases or increases domestic violence against women. See, for example, Kabeer ( 1998 ), Karim ( 2008 , 2011 , 2014 ), Nijera Kori ( 1990 ), Goetz and Gupta ( 1996 ), Hashemi et al. ( 1996 ) and Rozario ( 2007 ).

Other NGOs also advocate for such freedoms but do not work as women’s or feminist institutions (see, e.g., Odhikar, Bangladesh).

Two excellent collections responding to Rana Plaza are Saxena ( 2020 ) and a special issue of Development and Change , Volume 50, Issue 5.

Absar, S. S. (2001). Problems Surrounding Wages: The Readymade Garments Sector in Bangladesh. Labour and Management in Development Journal, 2 (7), 2–17.

Google Scholar

Ahmed, F. E. (2004). The Rise of the Bangladesh Garment Industry: Globalization, Women Workers, and Voice. NWSA Journal, 16 (2), 34–45.

Ahmed, N. R., & Chaudhury, R. H. (1980). Female Status in Bangladesh . Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies.

Ahmed, R. (1985). Women’s Movement in Bangladesh and the Left’s Understanding of the Women Question. Journal of Social Studies, 30 , 27–56.

Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), Bangladesh Mahila Parishad, & Steps Toward Development. (2004). Shadow Report to the Fifth Periodic Report of the Government of Bangladesh. To the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) , Dhaka. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&lr=&q=cache:IXnpkbTJgYAJ:www.iwraw-ap.org/resources/pdf/bangladesh_SR.pdf+salish+bangladesh

Alamgir, F., & Banerjee, S. B. (2019). Contested Compliance Regimes in Global Production Networks: Insights from the Bangladesh Garment Industry. Human Relations, 72 (2), 272–297.

Amin, R., Becker, S., & Bayes, A. (1998, Winter). NGO-Promoted Micro Programs and Women’s Empowerment in Rural Bangladesh: Quantitative and Qualitative Evidence. Journal of Developing Areas, 32 (2), 221–236.

Amin, S. (1995). Women’s Reproductive Rights and the Politics of Fundamentalism: A View from Bangladesh. The American University Law Review, 44 (4), 1319–1343.

Amin, S. (1997). The Poverty-Purdah Trap in rural Bangladesh: Implications for Women’s Roles in the Family. Development and Change, 28 , 213–233.

Amin, S., & Cain, M. (1997). The Rise of Dowry in Bangladesh. In G. W. Jones, J. C. Caldwell, R. M. Douglas, & R. M. D’Souza (Eds.), The Continuing Demographic Transition . Oxford University Press.

Anner, M. (2015). Worker Resistance in Global Supply Chains: Wildcat Strikes, International Accords and Transnational Campaigns. Internal Journal of Labour Research, 7 (1–2), 17–34.

Ashwin, S., Kabeer, N., & Schussler, E. (2020). Contested Understandings in the Global Garment Industry after Rana Plaza. Development and Change, 51 (5), 1360–1398.

Azim, F., & Sultan, M. (Eds.). (2010). Mapping Women’s Empowerment . BDI BRAC Development Institute, The University Press Limited.

Aziz, K. M. A., & Maloney, C. (1985). Life Stages, Gender and Fertility in Bangladesh . International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research Monograph No. 3.

Barrientos, S., Kabeer, N., & Hossain, N. (2004). The Gender Dimensions of the Globalization of Production, Working Paper No. 17, Policy Integration Department, World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalization . International Labour Organization.

Begum, S. (1985). Women and Technology: Rice Processing in Bangladesh. In Women in Rice Farming. Proceedings of a Conference on Women in Rice Farming Systems, 26–30 September 1983, International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Philippines . Gower Publishing Co. Ltd.

Begum, F., Ali, R. N., Hossain, M. A. & Shahid, S. B. (2010). Harassment of women garment workers in Bangladesh. Journal of Bangladesh Agricultural University, 8 , 291–196.

Boserup, E. (1970). Women’s Role in Economic Development . George Allen and Unwin.

Chen, L., Huo, E., & D’Souza, S. (1981). Sex Bias in the Family Allocation of Food and Health Care in Rural Bangladesh. Population and Development Review, 7 , 1.

Citizens’ Initiatives on CEDAW, Bangladesh (CIC-BD). (2016). Eighth CEDAW Shadow Report to the UN CEDAW Committee. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Secretariat, Steps Towards Development. www.steps.org.bd

Dannecker, P. (2002). Between Conformity and Resistance Women Garment Workers in Bangladesh . The University Press Limited.

Feldman, A., & McCarthy, F. E. (1983, November). Purdah and Changing Patterns of Social Control among Rural Women in Bangladesh. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45 (4), 949–959.

Feldman, S. (1983). The Use of Private Health Care Providers in Rural Bangladesh: A Response to Claquin. Social Science and Medicine, 17 (23), 1887–1896.

Feldman, S. (1990). Human Rights and the New Industrial Working Class in Bangladesh. In J. Claude, E. Welch, & V. A. Leary (Eds.), Asian Perspectives on Human Rights (pp. 218–231). Westview.

Feldman, S. (1992). Crisis, Islam and Gender in Bangladesh: The Social Construction of a Female Labor Force. In L. Benería & S. Feldman (Eds.), Unequal Burden: Economic Crises, Persistent Poverty, and Women’s Work (pp. 105–130). Westview Press.

Feldman, S. (1993). Contradictions of Gender Inequality: Urban Class Formation in Contemporary Bangladesh. In A. Clark (Ed.), Gender and Political Economy: Explorations of South Asian Systems (pp. 215–245). Oxford University Press.

Feldman, S. (2001). Exploring Theories of Patriarchy: A Perspective from Contemporary Bangladesh. SIGNS, 26 (4), 1097–1127.

Feldman, S. (2009). Historicizing Garment Manufacturing in Bangladesh: Gender, Generation, and New Regulatory Regimes. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 11 (1 (Gender and Islam in Asia)), 268–288.

Feldman, S. (2010). Social Development, Capabilities, and the Contradictions of (Capitalist) Development. In S. L. Esquith & F. Gifford (Eds.), Capabilities, Power, and Institutions: Toward a More Critical Development Ethics . The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Feldman, S. (2015). “Just 6p on a T-shirt, or 12p on a Pair of Jeans:” Bangladeshi Garment Workers Fight for a Livable Wage. In G. H. Ahmed (Ed.), Asian Muslim Women: Globalization and Local Realities (pp. 21–38). SUNY Press.

Feldman, S., Akhter, F., & Banu, F. (1980). An Analysis and Evaluation of the IRDP Women’s Programme in Population Planning and Rural Women’s Cooperatives . CIDA.

Feldman, S., & Hossain, J. (2020). The Longue Durée and the Promise of Export-Led Development: Readymade Garment Manufacturing in Bangladesh. In S. B. Saxena (Ed.), Labor, Global Supply Chains, and the Garment Industry in South Asia (pp. 21–44). Routledge.

Gelb, A., Mukherjee, A., Navis, K., Akter, M., & Naima, J. (2019, May). Primary Education Stipends in Bangladesh: Do Mothers Prefer Digital Payments over Cash? CGD Note . https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/primary-education-stipends-bangladesh-do-mothers-prefer-digital-payments-over-cash.pdf

Goetz, A. M., & Gupta, R. S. (1996). Who Takes the Credit? Gender, Power, and Control over Loan Use in Rural Credit Programs in Bangladesh. World Development, 24 (1), 45–63.

Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh (GoB). (2015). Millennium Development Goals, Bangladesh Progress Report . Bangladesh Progress Report 2015. Dhaka: General Economics Division (GED), Bangladesh Plannning Commission.

Hartmann, B. (1995). Reproductive Rights and Wrongs: The Global Politics of Population Control . South End Press.

Hashemi, S. M., Schuler, S. R., & Riley, A. P. (1996). Rural Credit Programs and Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh. World Development, 24 (4), 635–653.

Hossain, H., Jahan, R., & Sobhan, S. (1990). No Better Option?: Industrial Women Workers in Bangladesh . Dhaka: University Press.

Hossain, N. (2010). School Exclusion as Social Exclusion: The Practices and Effects of a Conditional Cash Transfer Programme for the Poor in Bangladesh. Journal of Development Studies, 46 (7), 1264–1282.

Hossain, N. (2011). Exports, Equity and Empowerment: The Effects of Readymade Garments Manufacturing Employment on Gender Equality in Bangladesh . World Development Report 2012, Gender Equality and Development, Background Paper.

Hossain, N. (2012). Women’s Empowerment Revisited: From Individual to Collective Power among the Export Sector Workers of Bangladesh (IDS Working Papers 389). Institute of Development Studies.

Hossain, N. (2017). The Aid Lab: Understanding Bangladesh’s Unexpected Success . Oxford University Press.

Huq, J., et al. (Eds.). (1983). Women in Bangladesh: Some Socio-economic Issues . Women for Women.

Huq, R. (2020). Bangladesh’s Private Sector: Beyond Tragedies and Challenges. In S. B. Saxena (Ed.), Labor, Global Supply Chains, and the Garment Industry in South Asia (pp. 117–130). Routledge.

Huq, S. (2006). Sex Workers’ Struggles in Bangladesh: Learning for the Women’s Movement. IDS Bulletin, 37 , 5.

Huq, S. P. (2003). Bodies as Sites of Struggle: Naripokkho and the Movement for Women’s Rights in Bangladesh. The Bangladesh Development Studies, 29 (3/4), 47–65.

Islam, M. (1980). Folk Medicine and Rural Women in Bangladesh . Women for Women.

Islam, M. (1985). Women, Health and Culture: A Study of Beliefs and Practices Connected with Female Diseases in a Bangladesh Village . Women for Women.

Islam, S. (1982). Women’s Education in Bangladesh: Needs and Issues . Foundation for Research on Educational Planning and Development.

Jahan, R. (1975). Women in Bangladesh. In Women for Women Research and Study Group (Ed.), Women for Women: Bangladesh 1975 (pp. 1–30). University Press Limited.

Jahan, R. (1983). Family Violence and Bangladeshi Women: Some Observations. In R. Jahan & L. Akanda (Eds.), Collected Articles, Women for Women: Research and Study Group (pp. 13–22). Women for Women.

Jahan, R. (1988a). Hidden Danger: Women and Family Violence in Bangladesh . Women for Women.

Jahan, R. (1988b). Hidden Wounds, Visible Scars: Violence Against Women in Bangladesh. In B. Agarwal (Ed.), Structures of Patriarchy (pp. 199–227). Zed Books Ltd..

Kabeer, N. (1988). Subordination and Struggle: Women in Bangladesh. New Left Review, 168 , 95–121.

Kabeer, N. (1990). Poverty, Purdah and Women’s Survival Strategies in Rural Bangladesh. In H. Bernstein, B. Crow, M. Macintosh, & C. Martin (Eds.), The Food Question: Profits versus People (pp. 134–148). Earthscan.

Kabeer, N. (1991). The Quest for National Identity: Women, Islam and the State in Bangladesh. In D. Kandyoti (Ed.), Women, Islam and the State (pp. 115–143). Temple University Press.

Kabeer, N. (1994). Reversed Realities: Gender Hierarchies in Development Thought . Verso.

Kabeer, N. (1997). Women, Wages and Intra-household Power Relations in Urban Bangladesh. Development and Change, 28 , 261–302.

Kabeer, N. (1998). Money Can’t Buy Me Love? Re-evaluating Gender, Credit and Empowerment in Rural Bangladesh. In IDS Discussion Paper 363 .

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Development and Change, 30 , 435–464.

Kabeer, N. (2000). The Power to Choose . Verso.

Kabeer, N. (2005). Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: A Critical Analysis of the Third Millennium Development Goal 1. Gender & Development, 13 (1), 13–24.

Kabeer, N., & Mahmud, S. (2004). Rags, Riches and Women Workers: Export-oriented Garment Manufacturing in Bangladesh. In M. Carr (Ed.), Chains of Fortune: Linking Women Producers and Workers with Global Markets (pp. 133–162). Commonwealth Secretariat.

Kabeer, N., & Mahmud, S. (2004a). Globalization, Gender and Poverty: Bangladeshi Women Workers in Export and Local Markets. Journal of International Development, 16 (1), 93–109.

Kabeer, N., & Mahmud, S. (2004b). Rags, Riches and Women Workers: Export-oriented Garment Manufacturing in Bangladesh. In M. Carr (Ed.), Chains of Fortune: Linking Women Producers and Workers with Global Markets (pp. 133–162). Commonwealth Secretariat.

Kabeer, N., Huq, L., & Sulaiman, M. (2020). Paradigm Shift or Business as Usual? Workers’ Views on Multistakeholder Initiatives in Bangladesh. Development and Change, 51 (5), 1360–1398.

Kabeer, N., Mahmud, S., & Tasneem, S. (2017). The Contested Relationship Between Paid Work and Women’s Empowerment: Empirical Analysis from Bangladesh. The European Journal of Development Research, 30 (2), 235–251.

Karim, L. (2008). Demystifying Micro-Credit: The Grameen Bank, NGOs, and Neoliberalism in Bangladesh. Cultural Dynamics, 20 (1), 5–29.

Karim, L. (2011). Microfinance and Its Discontents: Women in Debt in Bangladesh . University of Minnesota Press.

Karim, L. (2014). Analyzing Women’s Empowerment: Microfinance and Garment Labor in Bangladesh. Fletcher Forum of World Affair, 38 (2), 153–166.

Karim, L. (2018). Reversal of Fortunes: Transformations in State-NGO Relations in Bangladesh. Critical Sociology, 44 (4–5), 579–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920516669215

Article Google Scholar

Keating, C., Rasmussen, C., & Rishi, P. (2010). The Rationality of Empowerment: Microcredit, Accumulation by Dispossession and the Gendered Economy. SIGNS, 36 (1), 153–176.

Khan, S. I. (2001). Gender Issues and the Ready-made Garment Industry of Bangladesh: The Trade Union Context. In S. Rehman & N. Khundker (Eds.), Globalization and Gender: Changing Patterns of Women’s Employment in Bangladesh (pp. 179–218). University Press Ltd.

Kibria, N. (1995). Culture, Social Class, and Income Control in the Lives of Women Garment Workers in Bangladesh. Gender and Society, 9 (3), 289–309.

Kibria, N. (1998). Becoming a Garments Worker: The Mobilization of Women into the Garments Factories of Bangladesh. In C. Miller & J. Vivian (Eds.), Women’s Employment in the Textile Manufacturing Sectors of Bangladesh and Morocco (pp. 151–177). UNRISD and UNDP.

Lindenbaum, S. (1974). The Social and Economic Status of Women in Bangladesh . The Ford Foundation.

Mahmud, S., & Kabeer, N. (2003). Compliance Versus Accountability: Struggles for Dignity and Daily Bread in the Bangladesh Garment Industry. The Bangladesh Development Studies, 29 (3/4), 21–46.

Mahmud, S., & Kabeer, N. (2006). Compliance Versus Accountability: Struggles for Dignity and Daily Bread in the Bangladesh Garment Industry. In P. Newell & J. Wheeler (Eds.), Rights, Resources and the Politics of Accountability (pp. 223–244). Zed Books.

McCarthy, F. (1977). Bengali Village Women as Mediators of Social Change. Human Organization, 36 (4), 363–370.

McCarthy, F. E. (1978). The Status and Condition of Rural Women in Bangladesh . Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Planning and Development Cell.

McCarthy, F. E. (1980). Patterns of Employment and Income Earning among Female Household Labour . Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Women’s Planning Cell.

McCarthy, F. E. (1981a). Differential Family Characteristics as the Context for Women’s Productive Activities, Ministry of Agriculture, Bangladesh, Study Paper No. 1.

McCarthy, F. E. (1981b). Contributions of Women to the Production and Processing of Crops in Bangladesh . Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Women’s Section.

McCarthy, F. E. (n.d.). Female Household Workers in Four Districts in Bangladeshi . Unpublished Manuscript. Dhaka: Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Women’s Planning Cell.

McCarthy, F. E., & Feldman, S. (1983). Rural Women Discovered: New Sources of Capital and Labour in Bangladesh. Development and Change, 14 , 211–236.

Mookherjee, N. (2008, January). Gendered Embodiments: Mapping the Body-Politic of the Raped Woman and the Nation in Bangladesh. Feminist Review, 88 , 36–53.

Naved, R., Rahman, T., Willan, S., Jewkesb, R., & Gibb, A. (2018). Female Garment Workers’ Experiences of Violence in Their Homes and Workplaces in Bangladesh: A Qualitative Study. Social Science & Medicine, 196 , 150–157.

Naved, R. T., Newby, M., & Amin, S. (2001). The Effects of Migration and Work on Marriage of Female Garment Workers in Bangladesh. International Journal of Population Geography, 7 (2), 91–104.

Naved, R. T., & Persson, L. A. (2010). Dowry and Spousal Physical Violence Against Women in Bangladesh. Journal of Family Issues, XX (X), 1–27.

Nazneen, S., Hossain, N., & Chopra, D. (2019). Introduction: Contentious Women’s Empowerment in South Asia. Contemporary South Asia, 27 (4), 257–470.

Nazneen, S., Hossain, N., & Sultan, M. (2011). National Discourses on Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh: Continuities and Change . IDS. http://www.ids.ac.uk/files/dmfile/Wp368.pdf

Nazneen, S., Sultan, M., & Hossain, N. (2010). National Discourses on Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh: Enabling or Constraining Women’s Choices? Development, 53 (2), 239–246.

Nijera Kori. (1990). Annual Report . Nijera Kori.

Papanek, H. (1982). Purdah: Separate World and Symbolic Shelter. In H. Papanek & G. Minault (Eds.), Separate Worlds: Studies of Purdah in South Asia . Chanakya Publications.

Pastner, C. M. (1972). A Social Structural and Historical Analysis of Honour, Shame and Purdah. Anthropological Quarterly, 45 , 248–261.

Pastner, C. M. (1974). Accommodation to Purdah: The Female Perspective. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 36 , 408–418.

Rahman, S., & Rahmanur, K. M. (2020). Multi-actor Initiatives after Rana Plaza: Factory Managers’ Views. Development and Change, 51 (5), 1331–1359.

Rahman, Z., & Langford, T. (2012). Why Labour Unions Have Failed Bangladesh’s Garment Workers. In S. Mosoetsa & M. Williams (Eds.), Labor in the Global South: Challenges and Alternatives for Workers (pp. 87–106). ILO.

Rock, M. (2001). Globalisation and Bangladesh: The Case of Export-Oriented Garment Manufacture. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, XXIV (1), 201–225.

Rock, M. (2003). Labour Conditions in the Export-Oriented Garment Industry in Bangladesh. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 26 (3), 391–407.

Rozario, S. (1992). Purity and Communal Boundaries: Women and Social Change in a Bangladeshi Village . Zed Books.

Rozario, S. (1998). Disjunctions and Continuities: Dowry and the Position of Single Women in Bangladesh. In C. Risseeuw & K. Ganesh (Eds.), Negotiation and Social Space: A Gendered Analysis of Changing Kin and Security Networks in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa . AltaMira.

Rozario, S. (2007). The Dark Side of Micro-credit. In Open Democracy . http://www.opendemocracy.net/node/35350/print .

Saxena, S. B. (2020). Introduction: How Do We Understand the Rana Plaza Disaster and What Needs to Be Done to Prevent Future Tragedies. In S. B. Saxena (Ed.), Labor, Global Supply Chains, and the Garment Industry in South Asia (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

Schuler, S. R., Hashemi, S. M., & Badal, S. H. (2010). Men’s Violence against Women in Rural Bangladesh: Undermined or Exacerbated by Microcredit Programmes? In D. Eade (Ed.), Development with Women: Selected Essays from Development in Practice . OXFAM GB.

Schuler, S. R., Hashemi, S. M., & Jenkins, A. H. (1995). Bangladesh’s Family Planning Success Story: A Gender Perspective. International Family Planning Perspectives, 21 (4), 132–137, 166.

Sen, G., & Grown, C. for DAWN (Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era). (1988). Development Crises and Alternative Visions: Third World Women’s Perspectives . Earthscan Publications.

Siddiqi, D. M. (2017a). Afterword: Politics After Rana Plaza. In Unmaking the Global Sweatshop: Health and Safety of the World’s Garment Workers (pp. 275–282). University of Pennsylvania Press.

Siddiqi, D. M. (2017b). Before Rana Plaza: Toward a History of Labour Organizing in Bangladesh’s Garment Industry. In A. Vickers & V. Crinis (Eds.), Labour in the Clothing Industry in the Asia Pacific (pp. 60–79). Routledge.

Siddiqi, D. M. (2020). Spaces of Exception: National Interest and the Labor of Sedition. In S. B. Saxena (Ed.), Labor, Global Supply Chains, and the Garment Industry in South Asia (pp. 100–114). Routledge.

Sobhan, S. (1978). Legal Status of Women in Bangladesh . Bangladesh Institute of Law and International Affairs.

Stoeckel, J., & Choudhury, M. A. (1969). East Pakistan: Fertility and Family Planning in Comilla. Studies in Family Planning, 1 (39), 14–16.

Westergaard, K. (1983). Pauperization and Rural Women in Bangladesh: A Case Study . Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development.

White, S. C. (1992). Arguing with the Crocodile: Gender and Class in Bangladesh . Zed Books.

Zaman, H. (1999). Violence Against Women in Bangladesh: Issue and Responses. Women’s Studies International Forum, 22 (1), 37–48.

Zaman, H. (2001). Paid Work and Socio-political Consciousness of Garment Workers in Bangladesh. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 31 (2), 145–160.

Download references

Acknowledgment

This chapter is part of a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 665958.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Max-Weber-Kolleg für kultur-und sozialwissenschaftliche Studien, Universität Erfurt, Erfurt, Germany

Shelley Feldman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shelley Feldman .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Social Sciences, Zayed University, Khalifa City, United Arab Emirates

Habibul Khondker

School of Business and Law, Central Queensland University, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Olav Muurlink

Department of History and Philosophy, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Asif Bin Ali

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Feldman, S. (2022). Gender and Development. In: Khondker, H., Muurlink, O., Bin Ali, A. (eds) The Emergence of Bangladesh. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5521-0_12

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5521-0_12

Published : 22 February 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-5520-3

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-5521-0

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 04 Mar 2024

- Research & Ideas

Want to Make Diversity Stick? Break the Cycle of Sameness

Whether on judicial benches or in corporate boardrooms, white men are more likely to step into roles that other white men vacate, says research by Edward Chang. But when people from historically marginalized groups land those positions, workforce diversification tends to last. Chang offers three pieces of advice for leaders striving for diversity.

- 14 Sep 2023

Working Moms Are Mostly Thriving Again. Can We Finally Achieve Gender Parity?

The pandemic didn't destroy the workplace advancements moms had achieved. However, not all of the positive changes forced by the crisis and remote work have stuck, says research by Kathleen McGinn and Alexandra Feldberg.

- 26 Jul 2023

STEM Needs More Women. Recruiters Often Keep Them Out

Tech companies and programs turn to recruiters to find top-notch candidates, but gender bias can creep in long before women even apply, according to research by Jacqueline Ng Lane and colleagues. She highlights several tactics to make the process more equitable.

- 18 Jul 2023

- Cold Call Podcast

Diversity and Inclusion at Mars Petcare: Translating Awareness into Action

In 2020, the Mars Petcare leadership team found themselves facing critically important inclusion and diversity issues. Unprecedented protests for racial justice in the U.S. and across the globe generated demand for substantive change, and Mars Petcare's 100,000 employees across six continents were ready for visible signs of progress. How should Mars’ leadership build on their existing diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts and effectively capitalize on the new energy for change? Harvard Business School associate professor Katherine Coffman is joined by Erica Coletta, Mars Petcare’s chief people officer, and Ibtehal Fathy, global inclusion and diversity officer at Mars Inc., to discuss the case, “Inclusion and Diversity at Mars Petcare.”

- 03 Mar 2023

When Showing Know-How Backfires for Women Managers

Women managers might think they need to roll up their sleeves and work alongside their teams to show their mettle. But research by Alexandra Feldberg shows how this strategy can work against them. How can employers provide more support?

- 31 Jan 2023

Addressing Racial Discrimination on Airbnb

For years, Airbnb gave hosts extensive discretion to accept or reject a guest after seeing little more than a name and a picture, believing that eliminating anonymity was the best way for the company to build trust. However, the apartment rental platform failed to track or account for the possibility that this could facilitate discrimination. After research published by Professor Michael Luca and others provided evidence that Black hosts received less in rent than hosts of other races and showed signs of discrimination against guests with African American sounding names, the company had to decide what to do. In the case, “Racial Discrimination on Airbnb,” Luca discusses his research and explores the implication for Airbnb and other platform companies. Should they change the design of the platform to reduce discrimination? And what’s the best way to measure the success of any changes?

- 03 Jan 2023

Confront Workplace Inequity in 2023: Dig Deep, Build Bridges, Take Collective Action

Power dynamics tied up with race and gender underlie almost every workplace interaction, says Tina Opie. In her book Shared Sisterhood, she offers three practical steps for dismantling workplace inequities that hold back innovation.

- 29 Nov 2022

How Will Gamers and Investors Respond to Microsoft’s Acquisition of Activision Blizzard?

In January 2022, Microsoft announced its acquisition of the video game company Activision Blizzard for $68.7 billion. The deal would make Microsoft the world’s third largest video game company, but it also exposes the company to several risks. First, the all-cash deal would require Microsoft to use a large portion of its cash reserves. Second, the acquisition was announced as Activision Blizzard faced gender pay disparity and sexual harassment allegations. That opened Microsoft up to potential reputational damage, employee turnover, and lost sales. Do the potential benefits of the acquisition outweigh the risks for Microsoft and its shareholders? Harvard Business School associate professor Joseph Pacelli discusses the ongoing controversies around the merger and how gamers and investors have responded in the case, “Call of Fiduciary Duty: Microsoft Acquires Activision Blizzard.”

- 10 Nov 2022

Too Nice to Lead? Unpacking the Gender Stereotype That Holds Women Back

People mistakenly assume that women managers are more generous and fair when it comes to giving money, says research by Christine Exley. Could that misperception prevent companies from shrinking the gender pay gap?

- 08 Nov 2022

How Centuries of Restrictions on Women Shed Light on Today's Abortion Debate

Going back to pre-industrial times, efforts to limit women's sexuality have had a simple motive: to keep them faithful to their spouses. Research by Anke Becker looks at the deep roots of these restrictions and their economic implications.

- 01 Nov 2022

Marie Curie: A Case Study in Breaking Barriers

Marie Curie, born Maria Sklodowska from a poor family in Poland, rose to the pinnacle of scientific fame in the early years of the twentieth century, winning the Nobel Prize twice in the fields of physics and chemistry. At the time women were simply not accepted in scientific fields so Curie had to overcome enormous obstacles in order to earn a doctorate at the Sorbonne and perform her pathbreaking research on radioactive materials. How did she plan her time and navigate her life choices to leave a lasting impact on the world? Professor Robert Simons discusses how Marie Curie rose to scientific fame despite poverty and gender barriers in his case, “Marie Curie: Changing the World.”

- 18 Oct 2022

When Bias Creeps into AI, Managers Can Stop It by Asking the Right Questions

Even when companies actively try to prevent it, bias can sway algorithms and skew decision-making. Ayelet Israeli and Eva Ascarza offer a new approach to make artificial intelligence more accurate.

- 29 Jul 2022

Will Demand for Women Executives Finally Shrink the Gender Pay Gap?

Women in senior management have more negotiation power than they think in today's labor market, says research by Paul Healy and Boris Groysberg. Is it time for more women to seek better opportunities and bigger pay?

- 24 May 2022

Career Advice for Minorities and Women: Sharing Your Identity Can Open Doors

Women and people of color tend to minimize their identities in professional situations, but highlighting who they are often forces others to check their own biases. Research by Edward Chang and colleagues.

- 08 Mar 2022

Representation Matters: Building Case Studies That Empower Women Leaders

The lessons of case studies shape future business leaders, but only a fraction of these teaching tools feature women executives. Research by Colleen Ammerman and Boris Groysberg examines the gender gap in cases and its implications. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 22 Feb 2022

Lack of Female Scientists Means Fewer Medical Treatments for Women

Women scientists are more likely to develop treatments for women, but many of their ideas never become inventions, research by Rembrand Koning says. What would it take to make innovation more equitable? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 01 Sep 2021

How Women Can Learn from Even Biased Feedback

Gender bias often taints performance reviews, but applying three principles can help women gain meaningful insights, says Francesca Gino. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 23 Jun 2021

One More Way the Startup World Hampers Women Entrepreneurs

Early feedback is essential to launching new products, but women entrepreneurs are more likely to receive input from men. Research by Rembrand Koning, Ramana Nanda, and Ruiqing Cao. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 01 Jun 2021

- What Do You Think?

Are Employers Ready for a Flood of 'New' Talent Seeking Work?

Many people, particularly women, will be returning to the workforce as the COVID-19 pandemic wanes. What will companies need to do to harness the talent wave? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 10 May 2021

Who Has Potential? For Many White Men, It’s Often Other White Men

Companies struggling to build diverse, inclusive workplaces need to break the cycle of “sameness” that prevents some employees from getting an equal shot at succeeding, says Robin Ely. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Understanding Poverty

publication

World Bank Group Gender Equality Strategy (FY16-23)

Gender equality is central to the World Bank Group’s goals of ending extreme poverty and boosting shared prosperity. No society can develop sustainably without transforming the distribution of opportunities, resources and choices for males and females so that they have equal power to shape their own lives and contribute to their families, communities, and countries.

Henriette Kolb

WDR 2012: Gender Equality and Development

Gender equality is a core development objective in its own right. But greater gender equality is also smart economics, enhancing productivity and improving other development outcomes.

You have clicked on a link to a page that is not part of the beta version of the new worldbank.org. Before you leave, we’d love to get your feedback on your experience while you were here. Will you take two minutes to complete a brief survey that will help us to improve our website?

Feedback Survey

Thank you for agreeing to provide feedback on the new version of worldbank.org; your response will help us to improve our website.

Thank you for participating in this survey! Your feedback is very helpful to us as we work to improve the site functionality on worldbank.org.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Data Descriptor

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

Towards Gender Harmony Dataset: Gender Beliefs and Gender Stereotypes in 62 Countries

- Natasza Kosakowska-Berezecka ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3503-3921 1 ,

- Tomasz Besta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6209-3677 1 ,

- Paweł Jurek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9958-3941 1 ,

- Michał Olech 2 ,

- Jurand Sobiecki 1 ,

- Jennifer Bosson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2566-1078 3 ,

- Joseph A. Vandello 3 ,

- Deborah Best ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6715-0957 4 ,

- Magdalena Zawisza 5 ,

- Saba Safdar 6 ,

- Anna Włodarczyk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2106-5324 7 &

- Magdalena Żadkowska 1

Scientific Data volume 11 , Article number: 392 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

608 Accesses

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

The Towards Gender Harmony (TGH) project began in September 2018 with over 160 scholars who formed an international consortium to collect data from 62 countries across six continents. Our overarching goal was to analyze contemporary perceptions of masculinity and femininity using quantitative and qualitative methods, marking a groundbreaking effort in social science research. The data collection took place between January 2018 and February 2020, and involved undergraduate students who completed a series of randomized scales and the data was collected through the SurveyMonkey or Qualtrics platforms, with paper surveys being used in rare cases. All the measures used in the project were translated into 22 languages. The dataset contains 33,313 observations and 286 variables, including contemporary measures of gendered self-views, attitudes, and stereotypes, as well as relevant demographic data. The TGH dataset, linked with accessible country-level data, provides valuable insights into the dynamics of gender relations worldwide, allowing for multilevel analyses and examination of how gendered self-views and attitudes are linked to behavioral intentions and demographic variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Perceived gender and political persuasion: a social media field experiment during the 2020 US Democratic presidential primary election

Attitude toward gender inequality in China

Benevolent and hostile sexism in a shifting global context

Background & summary.

The Towards Gender Harmony project ( https://towardsgenderharmony.ug.edu.pl/ ) started in September 2018 with more than 160 scholars who have built an international consortium that collected data in 62 countries and six continents. Our overarching goal was to analyze contemporary perceptions of masculinity and femininity using quantitative and qualitative methods, marking a groundbreaking effort in social science research. Such multinational research is important, as it helps us move beyond the WEIRD perspective of Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic countries which heavily predominates in psychology 1 , 2 , 3 .

It has been more than 30 years since a similar large cross-cultural study examined understandings of masculinity and femininity. John Williams and Deborah Best established that universally, across 26 countries, (1) communality is associated with femininity and agency is associated with masculinity, and (2) women view themselves as more communal than men and men view themselves as more agentic than women 4 . While communality and agency are universal dimensions of human evaluation 5 , 6 underlying gender stereotypes and gendered self-views, the measures used in Williams and Best to capture communality and agency were not subjected to rigorous psychometric procedures for ensuring scales’ cultural invariance and equivalence. Further, because some of the data reported in Williams and Best were originally collected around 1977, they do not reflect the influence of dramatic changes in gender roles that have altered contemporary gender stereotypes 7 . It is thus important to reexamine these gender constructs today but with culturally invariant and equivalent measures. Our dataset includes contemporary data reflecting individuals’ gendered self-views, their descriptive, prescriptive, and proscriptive stereotypes about women and men, and a selection of gender beliefs and attitudes reflecting the contemporary literature of social psychology and society as a whole.

What is more, our project is unique as it examines the under-researched topic of the universality of stereotypes about men who, according to results of research (carried out so far mainly within Western cultural contexts), face strong pressures for conformity to norms such as agency, dominance, pursuit of high social status, and avoidance of femininity 8 , 9 . Apart from including contemporary measures of gendered self-views, attitudes, and gender stereotypes, we have also collected relevant demographic data. As a result, our Towards Gender Harmony dataset, linked with accessible country/nation-level data, offers powerful insight into the dynamics of gender relations worldwide, allowing for multilevel analyses and examination of how gender beliefs are linked to behavioral intentions and demographic variables.

This dataset has been so far used to test men’s support for gender equality across countries 10 ; to establish cross-culturally valid, psychometric properties and correlates of precarious manhood beliefs 11 ; to examine binary gender gaps in agentic and communal self-views 12 ; to investigate whether the degree of endorsement of precarious manhood beliefs at the country level was associated with various risk-related health behaviors and outcomes 13 , to test the double standard in gender rules across countries 14 ; and to test whether country-level precarious manhood beliefs were associated with more negative attitudes, fewer rights, more restrictive laws, and reduced safety for LGBTQ+ groups 15 .

To gather data, we conducted a cross-sectional survey study employing a rigorous approach encompassing questionnaire development, data acquisition, data processing, and statistical analysis techniques. Our study aimed to investigate contemporary perceptions of masculinity and femininity across different regions of the world. We prioritize transparency and reproducibility, ensuring that our methods are accessible to fellow researchers.

Questionnaire development

To collect pertinent information, we meticulously designed comprehensive questionnaires (refer to the Measures section for detailed content). Participants completed a battery of scales measuring a broad range of variables concerning gender beliefs and gender stereotypes (the full list is available at https://osf.io/7tza3 ).

Data acquisition

We adopted the convenience sampling method, aiming to recruit a minimum of 200 participants from each country. We sent out invitations to researchers to participate in our project using mailing lists aimed at psychology researchers across the globe. These mailing lists included the International Association of Cross-Cultural Psychology, the International Academy for Intercultural Relations, and the European Association of Social Psychology. To reduce cross-national differences due to potential confounding variables (e.g., education, age) that might occur if relied on more heterogeneous samples, we asked each collaborator to obtain a university student sample of at least 100 women and men. We have also made special efforts to recruit colleagues from underrepresented countries and continents and contacted individual colleagues. Data collection occurred between January 2018 and February 2020, as part of a broader cross-cultural research project (accessible on OSF: https://osf.io/mq48y ). Our participants consisted of undergraduate students who volunteered their time and, in most countries, received no compensation. We obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Board for Research projects at the Institute of Psychology, University of Gdańsk (no. 11/2018) and local Institutional Review Boards, and all participants provided informed consent. The order of measures was randomized, and data collection was facilitated through the SurveyMonkey or Qualtrics platforms. In rare instances, participants completed paper surveys.

Data processing

We took steps to ensure data quality and integrity throughout the data processing phase. Subsequently, we conducted data cleaning procedures to identify and address missing values, outliers, and inconsistencies (detailed in the Data Records section).

By adhering to these rigorous data collection and processing procedures, we aimed to generate reliable and robust findings concerning contemporary perceptions of masculinity and femininity across diverse global contexts. This commitment to transparency and thorough methodology ensures that our research can be comprehended and replicated by other scholars in the field.

All the measures used in the project were translated into 22 languages (Armenian, Chinese, Croatian, Danish, Dutch, English, Filipino, French, Georgian, German, Italian, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Spanish, Turkish, Ukrainian). Bilingual scholars in psychology used the back-translation procedure to create national versions of each scale. The English version of the scales was used as the basis for all translations.

Gendered self-views and gender stereotypes

Gendered self-views.

Participants indicated the extent to which 12 agency-related traits, 12 communality-related traits, 12 dominance-related traits, and 12 weakness-related traits described them on a scale from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 7 (describes me well). Traits were selected from a pool of 472 prescriptive gender stereotypes (see supplementary material for the adjectives selected, Table S1 and https://osf.io/7tza3 ) 4 , 8 , 16 . In addition, using the same scale, they also rated the following traits: gifted in science, gifted in math, linguistically gifted, and gifted in humanities.

Descriptive stereotypes

Participants rated the same set of traits (12 agency-related, 12 communality-related, 12 dominance-related, 12 weakness-related) on a scale from 1 (more frequently associated with women than men) to 7 (more frequently associated with men than women). In addition, using the same scale, they also rated the following traits: gifted in science, gifted in math, linguistically gifted, and gifted in humanities.

Prescriptive and proscriptive stereotypes

Participants rated the prescriptive (desirable) and proscriptive (undesirable) nature of the traits (12 agency-related, 12 communality-related, 12 dominance-related, 12 weakness-related) by answering “How desirable is it in your society for a woman [man] to possess this trait?” on a scale from 1 (not at all desirable) to 7 (very desirable). In addition, using the same scale, they also rated the following traits: gifted in science, gifted in math, linguistically gifted, and gifted in humanities.

Gender Beliefs & Attitudes

Precarious manhood beliefs.

We administered a short version of the Precarious Manhood Beliefs (PMB) scale 17 . Based on an exploratory factor analysis of 7 items from Vandello et al . 17 , we selected four items with loadings >0.45 that conveyed beliefs that manhood is difficult to earn (“Some boys do not become men no matter how old they get,” “Other people often question whether a man is a ‘real man’”) and easy to lose (“It is fairly easy for a man to lose his status as a man,” “Manhood is not assured – it can be lost”). Participants indicated their agreement on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Gender essentialism

Participants’ essentialist beliefs were measured with five items (e.g., “Their underlying nature makes it difficult for men to learn to behave more like women 18 ) on a scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

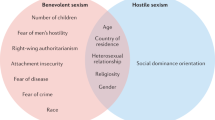

Ambivalent sexism

We used six items from the short version of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI) 19 , which measures Hostile Sexism (HS) and Benevolent Sexism (BS). We selected items from Rollero et al . 19 with factor loadings >0.50. HS items were: “Women seek to gain power by getting control over men,” “Women exaggerate problems they have at work,” and “When women lose to men in a fair competition, they typically complain about being discriminated against.” BS items were: “Women should be cherished and protected by men,” “Men are incomplete without women,” and “Women, compared to men, tend to have superior moral sensibility.” Items were answered on scales from 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Ambivalence toward Men

We used six items from the short version of the Ambivalence toward Men Inventory (AMI) 20 , which measures Hostility toward Men (HM) and Benevolence toward Men (BM). We selected items from Rollero et al . 20 with factor loadings >0.50. HM items were: “Men will always fight to have greater control in society than women,” “Men act like babies when they are sick,” and “Most men sexually harass women, even if only in subtle ways, once they are in a position of power over them.” BM items were: “Men are more willing to put themselves in danger to protect others,” “Every woman needs a male partner who will cherish her,” and “A woman will never be truly fulfilled in life if she doesn’t have a committed, long-term relationship with a man.” Items were rated on a 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale.

Collective action intentions to support gender equality

To measure intention to engage in collective behaviors for gender equality, we used items taken and modified from two scales. All items were rated on a scale from 1 (not likely at all) to 7 (very likely). Instructions started with a sentence stem (“To support gender equality, how likely it is that you would …”) followed by a list of actions. Four actions, modified from Tausch et al . 21 , included: “participate in demonstrations”; “sign a petition”; “block buildings or streets, and “disturb events, where advocates of inequality appear.” Six actions, modified from Alisat and Reimer 22 , included: “become involved with a group (or political party) focused on gender issues/gender equality (e.g., volunteer, summer job, etc.)”; “consciously make time to be able to work on gender issues/(support) gender equality (e.g., working part time for an organization, contribute to raise awareness about gender issues, choosing activities focused on gender issues over other leisure activities)”; “participate in a community event which focused on gender issues”; “Used online tools (e.g., Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, Wikipedia, Blogs) to raise awareness about gender issues/gender equality”; “Participated in an educational event (e.g., workshop) related to gender issues/gender equality”; “Spent time working with a group/organization that deals with the connection of the gender issues/gender equality to other societal issues such as justice or inequality”.

Identification with gender

Participants’ identification with their gender was measured with two items (“Being a member of my gender group is an important part of how I see myself”, “To what extent you consider yourself feminine/masculine”; based on van Breen et al . 23 . Responses ranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much).

Awareness of gender inequalities

Participants’ awareness of gender inequalities was measured with one item: “Overall, our society currently treats women less fairly than it treats men”. Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Gender roles and expectations

The items “What do you think women should prioritize?” and “What do you think men should prioritize?” were asked to assess societal attitudes and beliefs regarding gender roles. Respondents answered using a scale from 1 (Having a family) to 7 (Having a career). These items provided insights into broader societal norms related to gender roles and expectations. Individual preferences were also measured by similarly asking respondents what they would prioritize themselves – having a family or having a career.

Zero-sum beliefs about gender status

Participants’ zero-sum beliefs about gender status were assessed in two ways. The first was by the six-item Zero-Sum Perspective on Gender Status Scale (ZSPGS) 24 . The scale consists of items reflecting zero-sum beliefs in specific domains: occupational (‘More good jobs for women mean fewer good jobs for men’), power (‘The more power women gain, the less power men have’), economic (‘Women’s economic gains translate into men’s economic losses’), political (‘The more influence women have in politics, the less influence men have in politics’), social status (‘As women gain more social status, men lose social status’), and familial (‘More family-related decision making for women means less family-related decision making for men’). The second method was a more general single-item zero-sum perspective of gender status measure: ‘Declines in discrimination against women are directly related to increased discrimination against men’. Response options for each item ranged from 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Culture-related Relevant Measures

Autonomy and embeddedness values.

In this study, the 10-item scale for measuring Autonomy vs. Embeddedness values was employed, following Vignoles et al . 25 . This scale, derived from the Portrait Values Questionnaire 26 , assessed participants’ orientations towards Autonomy (e.g., “It is important to this person to think up new ideas and be creative; to do things one’s own way.”) vs. Embeddedness (e.g., “Living in secure surroundings is important to this person; to avoid anything that might be dangerous.”) values. Participants assessed how well the description matched their own characteristics or traits from 1 (very much like me) to 6 (not at all like me).

Power distance beliefs

Participants’ power distance beliefs were measured using four items 27 . These items (e.g., “There should be established ranks in society with everyone occupying their rightful place regardless of whether that place is high or low in the ranking”) measured attitudes about societal ranks, requesting salary increases, questioning authority decisions, and formal communication with superiors. Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Subjective socio-economic status

The Subjective Social Status Ladder 28 often referred to as the “Social Status Ladder”, was used to gauge an individual’s perception of their relative social position within their country. Respondents were asked to choose a number on the ladder from 0 (representing the lowest social status) to 10 (representing the highest social status) to indicate where they perceive themselves to be in comparison to others.

Attention checks

The survey also included three attention checks in which participants were asked to mark on a scale from 1 to 7 indicated numbers (“If you are reading this please choose 3”).

Demographic variables

At the end of the questionnaire demographic information was collected. We asked participants to declare their age, study major, gender identity, education level, marital status, number of children, citizenship, and sexual orientation/identity. We also measured migration background and ethnicity (with a list of major ethnic backgrounds, if necessary adjusted/extended to meet local cultural contexts). Additionally, we ask who fulfilled the role of financial provider in the family, who fulfilled the role of homemaker in the family, and how would they describe the place they grew up (a city, a town, the countryside/remote place/rural area. Finally, our demographic part included questions about religiosity and religious denomination as well as political orientation.

Data Records

The data comprising the TGH project results are stored in a single table. The data table is available in the repository 29 in three formats: csv, xlsx, and Rda. The dataset contains 33,313 observations, each in a separate row, and 286 variables, each in a separate column. A detailed description of the variables can be found in the Supplementary Excel File titled ‘CodebookTGH.xlsx’, available in the Towards Gender Harmony full dataset repository 29 , which also includes a link to an interactive map with descriptive statistics and a summary of selected published statistics – the map will be developed with more analyses. The variable description consists of the following components: ‘ID’ – a unique sequential number for the item/variable (ranging from 1 to 286); ‘Variable Name’; ‘Measure’ – reference to the measurement tool used to assess this variable (containing the respective item); ‘Scale’ – the dimension, the name of the theoretical variable composed of items assigned to the scale; ‘Label’ – the content of the survey item; ‘Level of measurement’ – information about the level at which the variable/response to the item is expressed (nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio); ‘Values’ – the range of values the variable can take; ‘Value Labels’ – possible response categories.

The dataset contains only responses provided by the study participants. Aggregated variables requiring, for example, the averaging of selected items (according to the key) must be calculated separately. To facilitate this process, we provide R code enabling the calculation of selected variables ‘TGH total scores code.R’ is available in the repository 29 .

Sample composition

We summarize the sample composition, including sample size, gender distribution, and descriptive statistics regarding age, for 13 distinct world regions, as illustrated in Table 1 . Additionally, we have provided detailed data for the 62 countries under study in the Supplementary Table 1 . As previously mentioned, our participants consisted of undergraduate students who volunteered their time. After data cleaning, the final dataset comprises 33,313 observations from 62 countries across 13 world regions. As can be seen in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 , both country-level and regional-level samples exhibit variations not only in terms of sample size but also in gender distribution and age distribution parameters.

Technical Validation

Data cleaning procedure.

Data cleaning is a crucial preparatory step to ensure the quality and reliability of data for subsequent analysis and modeling tasks 30 . In the TGH project, the data-cleaning procedure involved the following steps:

Data Integration: Data from various countries were provided by collaborators in separate files. We combined data from multiple sources into a unified dataset, resolving any inconsistencies in variables or units.

Data Inspection: We examined the dataset to identify inconsistencies, missing values, or outliers. We paid particular attention to data integrity, making sure that values either fell within acceptable ranges or adhered to predefined rules including verification of completeness of the data in all the scales, congruity between nominal categories in different countries. During this stage, we removed records with incorrect responses to attention check questions.

Handling Missing Data: In the TGH database, no data imputation methods were applied. In most cases, records with missing values were retained in the database. Only observations with data gaps preventing the calculation of most measured variables were removed.

Outlier Treatment: Outliers were observed in the age variable. Some responses appeared to contain randomly entered numbers (e.g., 247). Observations with such responses were removed. In a few cases where birthdates were mistakenly entered as ages, we recalculated the age by subtracting the birthdate from the examination date and rounding to full years. Outliers in other variables that could potentially skew the analysis were neither removed nor adjusted.

Data Transformation and Scaling: Due to the use of different response scales (mainly single-item scales) in some countries compared to the standardized scale adopted for the entire study (e.g., using a scale from 0 to 6 instead of 0 to 5), linear transformations were applied to harmonize the data.

Data Formatting: To ensure data format consistency, some responses recorded as labels were encoded into numerical values. The mapping of labels to numbers can be found in the Supplementary Excel File titled ‘CodebookTGH.xlsx,’ available in the repository 29 .

Data Verification: The cleaned dataset underwent validation, including the estimation of reliability ratios for aggregated scores (see Technical Validation).

As a result of the aforementioned operations, 710 observations were removed from the initial dataset ( N = 34,023). However, further processing is necessary, depending on the objectives of subsequent analyses and due to the presence of missing data in the dataset, to select a subset suitable for testing specific models that involve particular variables.

In addition to socio-demographic variables, the majority of variables under study are psychometric measures. As previously mentioned, the target variables are derived either by averaging/summing responses to items that make up the scale or by calculating them from the results of fitting CFA models. To assess the reliability of these measured variables, it is necessary to employ psychometric techniques. In this field, the most common method for estimating the reliability of such measurements is through the calculation of internal consistency coefficients, such as Cronbach’s (as recommended when raw scores are obtained by averaging/summing responses to items comprising a scale) 31 or McDonald’s omega (recommended when standardized scores are to be derived using CFA results) 32 . Table 2 presents both of these reliability measures for all target variables calculated on the total sample. Detailed data on reliability coefficients calculated for each country separately are provided in Supplementary Excel File titled ‘ReliabilityTGH.xlsx’, available in the repository 29 .

As can be seen in Table 2 , in the vast majority of cases, the reliability of variable measurements, as measured by the coefficient of internal consistency, exceeds the widely accepted cutoff point of >0.70 33 . Only in the case of five measures (i.e., Benevolent Sexism, Benevolence toward Men, Power Distance Beliefs, Autonomy Value, Embeddedness Value) did the results indicate reliabilities below the desired threshold. This partially can be attributed to the use of very short scales (<10 items) to measure these variables. Nevertheless it is advisable to exercise caution in interpreting the results, and it is recommended to thoroughly examine the reliability of measurements for these variables in individual countries (see Supplementary Excel File ‘ReliabilityTGH.xlsx’).

Given the cross-cultural nature of the data, it is essential to establish measurement invariance (MI) before conducting any analyses that compare results between countries. Measurement invariance refers to the consistency of a scale’s measurement properties across different groups or cultural contexts 34 . In simpler terms, it assesses whether the construct being measured is understood and interpreted in the same way across various groups or settings. Typically, researchers report three levels of measurement invariance, which are determined by parameters that are constrained to be equal across groups. The first level, configural invariance, requires the scale to demonstrate the same overall factor structure for all groups; the second level, metric invariance, necessitates that the scale items’ factor loadings be equal across the groups; and the third level, scalar invariance, demands that item intercepts be equal across groups.

For some variables in this study, such analyses have already been conducted and published 10 , 11 , 14 . These analyses involve assessing whether the measurement properties of a scale, such as factor loadings or item intercepts, remain consistent across different groups or countries. Establishing MI is crucial to ensure that any observed differences in the data result from genuine variations in the construct being measured and not from measurement bias or cultural differences.

Moreover, in the context of using the data to calculate country-level scores, it is advisable to test for psychometric isomorphism. Psychometric isomorphism extends the concept of MI by examining whether the underlying psychological structure of the measurement remains consistent across different levels, such as countries or cultures 35 . This analysis goes beyond examining the equivalence of mere measurement properties; it also investigates the constancy of the conceptual meaning and relationships among variables when considering the data at the country level.

These assessments of MI and psychometric isomorphism help ensure the validity and comparability of the data when conducting cross-cultural analyses and making country-level comparisons, providing a robust foundation for meaningful and reliable research findings.

Code availability

We provide R code enabling the calculation of selected variables. This code is available in the repository 29 under the name TGH total scores code.R. Its proper operation requires the use of the R environment at least version 4.3.1 and the tidyverse package 36 .

Arnett, J. J. The neglected 95%: why American psychology needs to become less American. Am. Psychol. 63 (7), 602–614 (2008).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J. & Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 33 (2-3), 61–83 (2010).

Rad, M. S., Martingano, A. J. & Ginges, J. Toward a psychology of Homo sapiens: Making psychological science more representative of the human population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115 (45), 11401–11405, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721165115 (2018).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Williams, J. E. & Best, D. L. Sex and psyche: Gender and self viewed cross-culturally . (Sage Publications Inc., 1990).

Bakan, D. The Duality of Human Existence: Isolation and Communion in Western Man . (Boston: Beacon Press, 1966).

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P. & Xu, J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82 , 878–902 (2002).

Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M. & Sczesny, S. Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of U.S. public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. Am. Psychol. 75 , 301–315 (2020).

Prentice, D. A. & Carranza, E. What women and men should be, shouldn’t be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychol. Women Q. 26 , 269–281 (2002).

Article Google Scholar

Vandello, J. A. & Bosson, J. K. Hard won and easily lost: A review and synthesis of theory and research on precarious manhood. Psychol. Men Masculin. 14 , 101–113 (2013).

Kosakowska-Berezecka, N. et al . Country-level and individual-level predictors of men’s support for gender equality in 42 countries. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 50 (6), 1276–1291 (2020).

Bosson, J. K. et al . Psychometric properties and correlates of precarious manhood beliefs in 62 nations. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 52 (3), 231–258 (2021).

Kosakowska-Berezecka, N. et al . Gendered self-views across 62 countries: A test of competing models. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 14 , 808–824 (2023).

Vandello, J. A., Wilkerson, M., Bosson, J. K., Wiernik, B. M. & Kosakowska-Berezecka, N. Precarious manhood and men’s physical health around the world. Psychol. Men Masculinity. 24 , 1–15 (2023).

Google Scholar

Bosson, J. K., Wilkerson, M., Kosakowska-Berezecka, N., Jurek, P. & Olech, M. Harder won and easier lost? Testing the double standard in gender rules in 62 countries. Sex Roles 87 , 1–19 (2022).

Vandello, J. A., Upton, R. A., Wilkerson, M., Kubicki, R. J. & Kosakowska-Berezecka, N. Cultural beliefs about manhood predict anti-LGBTQ+ attitudes and policies. Sex Roles 88 , 442–458 (2023).

Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E. & Nauts, S. Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48 , 165–179 (2012).

Vandello, J. A., Bosson, J. K., Cohen, D., Burnaford, R. M. & Weaver, J. R. Precarious manhood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95 , 1325–1339 (2008).

Skewes, L., Fine, C. & Haslam, N. Beyond Mars and Venus: The role of gender essentialism in support for gender inequality and backlash. PLoS ONE 13 (7), e0200921 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rollero, C., Glick, P. & Tartaglia, S. Psychometric properties of short versions of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory and Ambivalence Toward Men Inventory. TPM-Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 21 (2), 149–159 (2014).

Glick, P. & Whitehead, J. Hostility toward men and the perceived stability of male dominance. Soc. Psychol. 41 (3), 177–185 (2010).

Tausch, N. et al . Explaining radical group behavior: Developing emotion and efficacy routes to normative and nonnormative collective action. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101 (1), 129–148 (2011).

Alisat, S. & Reimer, M. The environmental action scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. J. Environ. Psychol. 43 , 13–23 (2015).

van Breen, J. A. et al . A Multiple Identity Approach to Gender: Identification with Women, Identification with Feminists, and Their Interaction. Front Psychol . (2017).

Ruthig, J. C., Kehn, A., Gamblin, B. W., Vanderzanden, K. & Jones, K. When women’s gains equal men’s losses: Predicting a zero-sum perspective of gender status. Sex Roles 76 (1-2), 17–26 (2017).

Vignoles, V. L. et al . Beyond the ‘east–west’ dichotomy: Global variation in cultural models of selfhood. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 145 (8), 966–1000 (2016).

Schwartz, S. Value orientations: Measurement, antecedents, and consequences across nations. In Measuring attitudes cross-nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey (Eds. Jowell, R., Roberts, C., Fitzgerald, R., & Eva, G.). (London: Sage Publications, 169-203, 2007).

Brockner, J. et al . Culture and procedural justice: The influence of power distance on reactions to voice. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 37 , 300–315 (2001).

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G. & Ickovics, J. R. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health Psychol. 19 , 586–592 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kosakowska-Berezecka, N. et al . Towards Gender Harmony Dataset. Open Science Framework https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TRKYC (2024).

van der Loo, M., & De Jonge, E. Statistical data cleaning with applications in R. (John Wiley & Sons, 2018).

Cronbach, L. J. Essentials of psychological testing (3rd ed.). (New York: Harper & Row, 1970).

McDonald, R. Test Theory: A Unified Treatment. (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1999).

Furr, M. R. Psychometrics: An Introduction (4th ed.). (SAGE Publications, 2021).

Milfont, T. L. & Fischer, R. Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 3 (1), 111–130 (2010).

Tay, L., Woo, S. E. & Vermunt, J. K. A conceptual and methodological framework for psychometric isomorphism: Validation of multilevel construct measures. Organ. Res. Methods 17 (1), 77–106 (2014).

Wickham, H. et al . Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software 4 (43), 1686 (2019).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The results presented in this paper are part of the larger project titled “Towards Gender Harmony” ( www.towardsgenderharmony.ug.edu.pl ), which involves many wonderful people. Here, we acknowledge our University of Gdańsk Research Assistants Team: Agata Bizewska, Mariya Amiroslanova, Aleksandra Globińska, Andy Milewski, Piotr Piotrowski, Stanislav Romanov, Aleksandra Szulc, and Olga Żychlińska for their assistance with programming the surveys and coordinating the collection of data at all sites. We are also thankful to all Towards Gender Harmony collaborators for their assistance in data collection.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Gdansk, Gdansk, Poland

Natasza Kosakowska-Berezecka, Tomasz Besta, Paweł Jurek, Jurand Sobiecki & Magdalena Żadkowska

Medical University of Gdansk, Gdansk, Poland

Michał Olech

University of South Florida, Tampa, USA

Jennifer Bosson & Joseph A. Vandello

Wake Forrest University, Winston-Salem, USA

Deborah Best

Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, England

Magdalena Zawisza

University of Guelph, Guelph, Canada

Saba Safdar

Universidad Catolica del Norte, Antofagasta, Chile

Anna Włodarczyk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

N.K.B. supervised the entire project and data collection. In addition, P.J. and M.O. and J.S. and T.B. were involved in dataset preparation, and P.J. and M.O. were responsible for data validation and data visualization. All Authors (N.K.B., T.B., P.J., M.O., J.S., J.B., J.V., D.B., S.S., A.W., M.Ż.) contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, and the drafting of the work or revising it critically for important intellectual contributions. All authors have approved this version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Natasza Kosakowska-Berezecka .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary table 1, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kosakowska-Berezecka, N., Besta, T., Jurek, P. et al. Towards Gender Harmony Dataset: Gender Beliefs and Gender Stereotypes in 62 Countries. Sci Data 11 , 392 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03235-x

Download citation

Received : 14 December 2023

Accepted : 05 April 2024

Published : 17 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03235-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Faculty & Staff

- Five Islands

- St. Augustine

- Open Campus

First In the Region

- Welcome to UWI

- UWI Achievements

- History & Mission

- Media Centre

- Giving to UWI

- Contributing Countries

For Students

- Student Resources & Financial Aid

- Staff Directory

- Alumni Online

- Our Programmes

- Programme Search

- International Students

- Student Life at UWI

UG & PG Admissions

- UG Admissions by Campus

- PG Admissions by Campus

- The University Chancellor

- The Office of the Visitor

- The Vice Chancellery

- Principal Officers

- Book Our facilities

- The Open Campus

Our Research Initiatives