Implementation Research in Developed and Developing Countries: an Analysis of the Trends and Directions

- Published: 10 September 2022

- Volume 23 , pages 1259–1273, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Daniel Dramani Kipo-Sunyehzi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3697-3333 1

234 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The article examines implementation research across developed countries (North America, Europe), developing countries (Asia, Pacific) and Africa. It examines some key trends and directions of implementation research across regions. It revisits policy debate among scholars on approaches to implementation-top-down, bottom-up and mixed which characterised the developed world. Also, it adds some perspectives on the developing world including Africa. The paper has three contributions: it highlights trends in implementation research in developed and developing countries. It gives some directions on implementation research in Africa. It recommends that the policy design process should not be neglected, such neglect is inimical to implementation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Launch of the Norwegian Network for Implementation Research (NIMP): Proceedings from the First Annual Conference

Thomas Engell, Cecilie Varsi, … Karina M. Egeland

Proceedings from the Third Annual Conference of the Norwegian Network for Implementation Research (NIMP)

Anne Merete Bjørnerud, Helle K. Falkenberg, … Thomas Engell

Proceedings from the Second Annual Conference of the Norwegian Network for Implementation Research

Karina M. Egeland, Thomas Engell, … Cecilie Varsi

Aina, T. A. (2013). Giving to help, helping to give: The context and politics of African philanthropy . Dakar: Amalion Publishing

Google Scholar

Asagba, A. (2005). Research and the formulation and implementation of ageing policy in Africa: the case of Nigeria. Generations Review , 15 (2), 39–41

Awortwi, N. (2017). ‘Politics, public policy and social protection in Africa: an Introduction and Overview’. In N. Awortwi and., & E. R. Aiyede (Eds.), (Eds ), Politics, Public Policy and Social Protection in Africa: Evidence from Cash Transfer Programmes . London: Routledge

Chapter Google Scholar

Awortwi, N., & Helmsing, A. H. J. (2014). Behind the façade of bringing services closer to people The proclaimed and hidden intentions of the government of Uganda to create many new local government districts. Canadian Journal of African Studies , 48 (2), 297–314

Ayee, J. R. (1994). An Anatomy of Public Policy Implementation. The case of Decentralisation Policies in Ghana . Aldershot: Evebury

Ayee, J. (2012). Politicians and bureaucrats as generators of public policy in Ghana. In F. Ohemeng, & J. Ayee (Eds.), The Public Policy Making Process in Ghana: How Politicians and Civil Servants Deal with Public Problems (pp. 19–50). Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press

Ayisi, E. K., Yeboah-Assiamah, E., & Bawole, J. N. (2018). Politics of Public Policy Implementation: Case of Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance . NY: Springer

Bardach, E. (1977). The Implementation Game: What Happens After a Bill Becomes a Law . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Béland, D., & Ridde, V. (2016). Ideas and policy implementation: Understanding the resistance against free health care in Africa. Global Health Governance , 10 (3), 9–23

Bénit-Gbaffou, C. (2018). Beyond the policy-implementation Gap: how the city of Johannesburg manufactured the ungovernability of street trading. The Journal of Development Studies , 54 (12), 2149–2167

Article Google Scholar

Berman, P. (1978). The study of macro-and micro-implementation. Public Policy , 26 (2), 157–184

Berman, P. (1980). Thinking about programmed and adaptive implementation: matching strategies to situations. In H. Ingram, & D. Mann (Eds.), Why Policies Succeed or Fail . Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications

Bhardwaj, S., Carter, B., Aarons, G. A., & Chi, B. H. (2015). Implementation research for the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa: existing evidence, current gaps, and new opportunities. Current HIV/AIDS Reports , 12 (2), 246–255

Bowen, E. R. (1982). The Pressman-Wildavsky paradox: four addenda or why models based on probability theory can predict implementation success and suggest useful tactical advice for implementers. Journal of Public Policy , 2 (1), 1–21

Bratton, M. (1990). Non-governmental organizations in Africa: Can they influence public policy? Development and change , 21 (1), 87–118

Brinkerhoff, D. W. (1996). Process perspectives on policy change: highlighting implementation. World Development , 24 (9), 1395–1401

Brinkerhoff, D. W. (1999). State-Civil Society Networks for Policy Implementation in Developing Countries. Review of Policy Research , 16 (1), 123–147

Brynard, P. A. (2009). Policy implementation: is policy learning a myth or an imperative? Administracio Publica , 17 (4), 13–27

Cowan, F. M., Delany-Moretlwe, S., Sanders, E. J., Mugo, N. R., Guedou, F. A., Alary, M., & Bekker, L. G. (2016). PrEP implementation research in Africa: what is new? Journal of the International AIDS Society , 19 (6), 1–11

Crosby, B. L. (1996). Policy implementation: the organisational challenge. World Development , 24 (9), 1403–1415

Derthick, M. (1970). The Impact of Federal Grants: Public Assistance in Massachusetts . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Book Google Scholar

Derthick, M. (1972). New Towns In-Town: Why a Federal Program Failed . Washington DC: Urban Institute

Edward, I. I. I., G.C (1980). Implementing Public Policy . Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Press

Effiong, A. N. (2013). Policy Implementation and its challenges in Nigeria. Int’l J Advanced Legal Stud & Governance , 4 , 26

Elmore, R. F. (1979). Backward Mapping: Implementation research and policy decision. Political Science Quarterly , 94 (4), 601–616

Elmore, R. F. (1985). Forward and backward mapping: reversible logic in the analysis of public policy. In K. Hanf, & T. A. J. Toonen (Eds.), Policy Implementation in Federal and Unitary Systems . Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers

Flisher, A. J., Lund, C., Funk, M., Banda, M., Bhana, A., Doku, V., & Petersen, I. (2007). Mental health policy development and implementation in four African countries. Journal of health psychology , 12 (3), 505–516

Garner, P., Kale, R., Dickson, R., Dans, T., & Salinas, R. (1998). Implementing research findings in developing countries. Bmj , 317 (7157), 531–535

Goggin, M. L., Bowman, A. O. M., Lester, J. P., & O’Toole, L. J. Jr. (1990). Implementation Theory and Practice: Toward a Third Generation . Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman/Little, Brown and Company

Grindle, M. S. (1980). Policy Content and Context in Implementation. In M. Grindle (Ed.), Politics and Policy Implementation in the Third World . Princeton-New Jersey: Princeton University Press

Grindle, M. S., & Thomas, J. W. (1991). Public Choices and Policy Change: The Political Economy of Reform in Developing Countries . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

Grindle, M. S. (2017). Politics and policy implementation in the Third World . Princeton University Press

Hill, M., & Hupe, P. (2009). Implementing Public Policy (2nd ed.). London: SAGE Publications

Hjern, B. (1982). Implementation research: the link gone missing. Journal of Public Policy , 2 , 301–308

Hjern, B., & Porter, D. O. (1981). Implementation structures: a new unit of administrative analysis. Organizational Studies , 2 , 211–227

Hjern, B., & Hull, C. (1982). Implementation research as empirical constitutionalism. European Journal of Political Research , 10 (2), 105–115

Hupe, P., & Sætren, H. (2015). Comparative Implementation Research: Directions and Dualities. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice , 17 (2), 93–102

Imurana, B., Kilu, R. H., & Kofi, A. B. (2014). The politics of public policy and problems of implementation in Africa: an appraisal of Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme in Ga East District. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science , 4 (4), 196–207

Isidiho, A. O., & Sabran, M. S. B. (2016). Evaluating the top-bottom and bottom-up community development approaches: Mixed method approach as alternative for rural un-educated communities in developing countries. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences , 7 (4), 266

Johnson, K. (2004). The politics of AIDS policy development and implementation in postapartheid South Africa.Africa Today,107–128

Kipo, D. D. (2011). Implementation of public policy at the local level in Ghana: the case of national health insurance scheme in Sawla-Tuna-Kalba District. Master of Philosophy Thesis, University of Bergen, Norway

Kipo-Sunyehzi, D. D. (2019). Public-Private Organizations Behaviour: the Paradoxes in the Implementation of Ghana’s Health Insurance Scheme.Public Organization Review,1–12

Kipo-Sunyehzi, D. D. (2020b). Global Social Welfare and Social Policy Debates: Ghana’s Health Insurance Scheme Promotion of the Well-Being of Vulnerable Groups.Journal of Social Service Research,1–15

Kipo-Sunyehzi, D. D. (2020a). Making public policy implementable: the experience of the National Health Insurance Scheme of Ghana. International Journal of Public Policy , 15 (5–6), 451–469

Kpessa-Whyte, M. (2018). The Politics of Healthcare Financing Reforms in Ghana: a Comparative Analysis of the Rawlings and Kufuor Years. Ghana Social Science , 15 (1), 1

Langlois, E. V., Mancuso, A., Elias, V., & Reveiz, L. (2019). Embedding implementation research to enhance health policy and systems: a multi-country analysis from ten settings in Latin America and the Caribbean. Health research policy and systems , 17 (1), 1–14

Lester, J. P., Bowman, A. O. M., Goggin, M. L., & O’Toole, L. J. (1987). Public policy implementation: evolution of the field and agenda for future research. Policy Studies Review , 7 (1), 200–216

Linder, S. H., & Peters, B. G. (1987). A design perspective on policy implementation: the fallacies of misplaced prescription. Policy Studies Review , 6 (3), 459–475

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services . New York: Russell Sage Foundation

Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service . 30th Ann. ed. New York: Russell Sage Foundation

Lledó, V., & Poplawski-Ribeiro, M. (2013). Fiscal policy implementation in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development , 46 , 79–91

Makinde, T. (2005). Problems of policy implementation in developing nations: the Nigerian experience. Journal of Social Science , 11 (1), 63–69

Matland, R. E. (1995). Synthesizing the implementation literature: the ambiguity-conflict model of policy implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory , 5 (2), 145–174

Milward, H. B., & Provan, K. G. (1993). The Hollow State: Private Provision of Public Services. In H. Ingram, & S. R. Smith (Eds.), Public Policy for Democracy (pp. 222–237). Washington DC: Brookings Institution

Mohammed, A. K. (2020). Does the policy cycle reflect the policymaking approach in Ghana?Journal of Public Affairs,1–15

Molete, M., Stewart, A., Bosire, E., & Igumbor, J. (2020). The policy implementation gap of school oral health programmes in Tshwane, South Africa: a qualitative case study. BMC health services research , 20 , 1–11

Murphy, J. (1973). The education bureaucracies implement noble policy: the politics of title I of ESEA. In A. Sindler (Ed.), Policy and Politics in America . Boston, MA: Little, Brown

Najam, A. (1995). Learning from the literature on policy implementation: a synthesis perspective. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIAS). Working Paper 95 – 61, pp. 1.70

Nakamura, R. T., & Smallwood, F. (1980). The politics of policy implementation (pp. 7–8). New York: St. Martin’s Press

Nkondo, G. M. (2007). Ubuntu as public policy in South Africa: A conceptual framework. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies , 2 (1), 88–100

Norren, D. E. V. (2014). The nexus between Ubuntu and Global Public Goods: its relevance for the post 2015 development Agenda, Development Studies Research. An Open Access Journal , 1 (1), 255–266

Ohemeng, F., Carroll, B., & Ayee, J. (2012). The Public Policy Making Process in Ghana: How Politicians and Civil Servants Deal with Public Problems . Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press

Ohemeng, F., & Ayee, J. (2012). Public policy making: the Ghanaian context. In F. Ohemeng, Frank, & J. Ayee (Eds.), The Public Policy Making Process in Ghana: How Politicians and Civil Servants Deal with Public Problems (pp. 19–50). Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press

O’Toole, L. J. Jr. (2000). Research on policy implementation: assessment and prospects. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory , 10 (2), 263–288

Peters, B. G., Capano, G., Howlett, M., Mukherjee, I., Chou, M. H., & Ravinet, P. (2018). Designing for policy effectiveness: Defining and understanding a concept . Cambridge University Press

Peters, D. H., Adam, T., Alonge, O., Agyepong, I. A., & Tran, N. (2013). Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. Bmj , 347 (f6753), 1–7

Pressman, J. L., & Wildavsky, A. B. (1973). Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland; Or, Why It’s Amazing that Federal Programs Work at All… . Berkeley: University of California Press

Qobo, M., & Nyathi, N. (2016). Ubuntu, public policy ethics and tensions in South Africa’s foreign policy. South African Journal of International Affairs , 23 (4), 421–436

Quintero, J., García-Betancourt, T., Caprara, A., Basso, C., Garcia da Rosa, E., Manrique-Saide, P., & Kroeger, A. (2017). Taking innovative vector control interventions in urban Latin America to scale: lessons learnt from multi-country implementation research. Pathogens and global health , 111 (6), 306–316

Ridde, V. (2009). Policy implementation in an African state: an extension of Kingdon’s Multiple-Streams Approach. Public Administration , 87 (4), 938–954

Sabatier, P. A. (1986). Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: a critical analysis and suggested synthesis. Journal of public policy , 6 (1), 21–48

Sabatier, P. A., & Mazmanian, D. (1979). The conditions of effective implementation: a guide to accomplishing policy objectives. Policy Analysis , 5 (4), 481–504

Sabatier, P. A., & Mazmanian, D. (1980). The implementation of public policy: a framework of analysis. Policy Studies Journal , 8 (4), 538–560

Saetren, H. (2005). Facts and myths about research on public policy implementation: Out-of‐Fashion, allegedly dead, but still very much alive and relevant. The Policy Studies Journal , 33 (4), 559–582

Saetren, H. (2014). Implementing the third generation research paradigm in policy implementation research: an empirical assessment. Public Policy and Administration , 0 (0), 1–22

Saguin, K., Ramesh, M., & Howlett, M. (2018). Policy work and capacities in a developing country: evidence from the Philippines. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration , 40 (1), 1–22

Sanders, D., & Haines, A. (2006). Implementation research is needed to achieve international health goals. Plos Medicine , 3 (6), 0719–0722

Sapolsky, H. M. (1972). The Polaris System Development: Bureaucratic and Programmatic Success in Government . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Tran, N., Langlois, E. V., Reveiz, L., Varallyay, I., Elias, V., Mancuso, A., & Ghaffar, A. (2017). Embedding research to improve program implementation in Latin America and the Caribbean. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública , 41 , e75

Van Meter, D., & Van Horn, C. E. (1975). The policy implementation process: a conceptual framework. Administration and Society , 6 (4), 445–488

Varallyay, N. I., Bennett, S. C., Kennedy, C., Ghaffar, A., & Peters, D. H. (2020). How does embedded implementation research work? Examining core features through qualitative case studies in Latin America and the Caribbean. Health policy and planning , 35 (Supplement_2), ii98–ii111

Winter, S. C. (2012). Implementation. In B. G. Peters, & J. Pierre (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Public Administration (2nd ed., pp. 255–264). London: Sage Publications Ltd

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Ghana, Legon Centre for International Affairs and Diplomacy (LECIAD), Accra, Ghana

Daniel Dramani Kipo-Sunyehzi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel Dramani Kipo-Sunyehzi .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

the author declares no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Informed consent, additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Kipo-Sunyehzi, D.D. Implementation Research in Developed and Developing Countries: an Analysis of the Trends and Directions. Public Organiz Rev 23 , 1259–1273 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00659-0

Download citation

Accepted : 27 August 2022

Published : 10 September 2022

Issue Date : September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00659-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Implementation research

- Developed countries

- Developing countries

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

DevelopingCountriesandEconomies →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

The economic commitment of climate change

- Maximilian Kotz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2564-5043 1 , 2 ,

- Anders Levermann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4432-4704 1 , 2 &

- Leonie Wenz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8500-1568 1 , 3

Nature volume 628 , pages 551–557 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

63k Accesses

3473 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Environmental economics

- Environmental health

- Interdisciplinary studies

- Projection and prediction

Global projections of macroeconomic climate-change damages typically consider impacts from average annual and national temperatures over long time horizons 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . Here we use recent empirical findings from more than 1,600 regions worldwide over the past 40 years to project sub-national damages from temperature and precipitation, including daily variability and extremes 7 , 8 . Using an empirical approach that provides a robust lower bound on the persistence of impacts on economic growth, we find that the world economy is committed to an income reduction of 19% within the next 26 years independent of future emission choices (relative to a baseline without climate impacts, likely range of 11–29% accounting for physical climate and empirical uncertainty). These damages already outweigh the mitigation costs required to limit global warming to 2 °C by sixfold over this near-term time frame and thereafter diverge strongly dependent on emission choices. Committed damages arise predominantly through changes in average temperature, but accounting for further climatic components raises estimates by approximately 50% and leads to stronger regional heterogeneity. Committed losses are projected for all regions except those at very high latitudes, at which reductions in temperature variability bring benefits. The largest losses are committed at lower latitudes in regions with lower cumulative historical emissions and lower present-day income.

Similar content being viewed by others

Climate damage projections beyond annual temperature

Paul Waidelich, Fulden Batibeniz, … Sonia I. Seneviratne

Investment incentive reduced by climate damages can be restored by optimal policy

Sven N. Willner, Nicole Glanemann & Anders Levermann

Climate economics support for the UN climate targets

Martin C. Hänsel, Moritz A. Drupp, … Thomas Sterner

Projections of the macroeconomic damage caused by future climate change are crucial to informing public and policy debates about adaptation, mitigation and climate justice. On the one hand, adaptation against climate impacts must be justified and planned on the basis of an understanding of their future magnitude and spatial distribution 9 . This is also of importance in the context of climate justice 10 , as well as to key societal actors, including governments, central banks and private businesses, which increasingly require the inclusion of climate risks in their macroeconomic forecasts to aid adaptive decision-making 11 , 12 . On the other hand, climate mitigation policy such as the Paris Climate Agreement is often evaluated by balancing the costs of its implementation against the benefits of avoiding projected physical damages. This evaluation occurs both formally through cost–benefit analyses 1 , 4 , 5 , 6 , as well as informally through public perception of mitigation and damage costs 13 .

Projections of future damages meet challenges when informing these debates, in particular the human biases relating to uncertainty and remoteness that are raised by long-term perspectives 14 . Here we aim to overcome such challenges by assessing the extent of economic damages from climate change to which the world is already committed by historical emissions and socio-economic inertia (the range of future emission scenarios that are considered socio-economically plausible 15 ). Such a focus on the near term limits the large uncertainties about diverging future emission trajectories, the resulting long-term climate response and the validity of applying historically observed climate–economic relations over long timescales during which socio-technical conditions may change considerably. As such, this focus aims to simplify the communication and maximize the credibility of projected economic damages from future climate change.

In projecting the future economic damages from climate change, we make use of recent advances in climate econometrics that provide evidence for impacts on sub-national economic growth from numerous components of the distribution of daily temperature and precipitation 3 , 7 , 8 . Using fixed-effects panel regression models to control for potential confounders, these studies exploit within-region variation in local temperature and precipitation in a panel of more than 1,600 regions worldwide, comprising climate and income data over the past 40 years, to identify the plausibly causal effects of changes in several climate variables on economic productivity 16 , 17 . Specifically, macroeconomic impacts have been identified from changing daily temperature variability, total annual precipitation, the annual number of wet days and extreme daily rainfall that occur in addition to those already identified from changing average temperature 2 , 3 , 18 . Moreover, regional heterogeneity in these effects based on the prevailing local climatic conditions has been found using interactions terms. The selection of these climate variables follows micro-level evidence for mechanisms related to the impacts of average temperatures on labour and agricultural productivity 2 , of temperature variability on agricultural productivity and health 7 , as well as of precipitation on agricultural productivity, labour outcomes and flood damages 8 (see Extended Data Table 1 for an overview, including more detailed references). References 7 , 8 contain a more detailed motivation for the use of these particular climate variables and provide extensive empirical tests about the robustness and nature of their effects on economic output, which are summarized in Methods . By accounting for these extra climatic variables at the sub-national level, we aim for a more comprehensive description of climate impacts with greater detail across both time and space.

Constraining the persistence of impacts

A key determinant and source of discrepancy in estimates of the magnitude of future climate damages is the extent to which the impact of a climate variable on economic growth rates persists. The two extreme cases in which these impacts persist indefinitely or only instantaneously are commonly referred to as growth or level effects 19 , 20 (see Methods section ‘Empirical model specification: fixed-effects distributed lag models’ for mathematical definitions). Recent work shows that future damages from climate change depend strongly on whether growth or level effects are assumed 20 . Following refs. 2 , 18 , we provide constraints on this persistence by using distributed lag models to test the significance of delayed effects separately for each climate variable. Notably, and in contrast to refs. 2 , 18 , we use climate variables in their first-differenced form following ref. 3 , implying a dependence of the growth rate on a change in climate variables. This choice means that a baseline specification without any lags constitutes a model prior of purely level effects, in which a permanent change in the climate has only an instantaneous effect on the growth rate 3 , 19 , 21 . By including lags, one can then test whether any effects may persist further. This is in contrast to the specification used by refs. 2 , 18 , in which climate variables are used without taking the first difference, implying a dependence of the growth rate on the level of climate variables. In this alternative case, the baseline specification without any lags constitutes a model prior of pure growth effects, in which a change in climate has an infinitely persistent effect on the growth rate. Consequently, including further lags in this alternative case tests whether the initial growth impact is recovered 18 , 19 , 21 . Both of these specifications suffer from the limiting possibility that, if too few lags are included, one might falsely accept the model prior. The limitations of including a very large number of lags, including loss of data and increasing statistical uncertainty with an increasing number of parameters, mean that such a possibility is likely. By choosing a specification in which the model prior is one of level effects, our approach is therefore conservative by design, avoiding assumptions of infinite persistence of climate impacts on growth and instead providing a lower bound on this persistence based on what is observable empirically (see Methods section ‘Empirical model specification: fixed-effects distributed lag models’ for further exposition of this framework). The conservative nature of such a choice is probably the reason that ref. 19 finds much greater consistency between the impacts projected by models that use the first difference of climate variables, as opposed to their levels.

We begin our empirical analysis of the persistence of climate impacts on growth using ten lags of the first-differenced climate variables in fixed-effects distributed lag models. We detect substantial effects on economic growth at time lags of up to approximately 8–10 years for the temperature terms and up to approximately 4 years for the precipitation terms (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 2 ). Furthermore, evaluation by means of information criteria indicates that the inclusion of all five climate variables and the use of these numbers of lags provide a preferable trade-off between best-fitting the data and including further terms that could cause overfitting, in comparison with model specifications excluding climate variables or including more or fewer lags (Extended Data Fig. 3 , Supplementary Methods Section 1 and Supplementary Table 1 ). We therefore remove statistically insignificant terms at later lags (Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ). Further tests using Monte Carlo simulations demonstrate that the empirical models are robust to autocorrelation in the lagged climate variables (Supplementary Methods Section 2 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 ), that information criteria provide an effective indicator for lag selection (Supplementary Methods Section 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6 ), that the results are robust to concerns of imperfect multicollinearity between climate variables and that including several climate variables is actually necessary to isolate their separate effects (Supplementary Methods Section 3 and Supplementary Fig. 7 ). We provide a further robustness check using a restricted distributed lag model to limit oscillations in the lagged parameter estimates that may result from autocorrelation, finding that it provides similar estimates of cumulative marginal effects to the unrestricted model (Supplementary Methods Section 4 and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9 ). Finally, to explicitly account for any outstanding uncertainty arising from the precise choice of the number of lags, we include empirical models with marginally different numbers of lags in the error-sampling procedure of our projection of future damages. On the basis of the lag-selection procedure (the significance of lagged terms in Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 2 , as well as information criteria in Extended Data Fig. 3 ), we sample from models with eight to ten lags for temperature and four for precipitation (models shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ). In summary, this empirical approach to constrain the persistence of climate impacts on economic growth rates is conservative by design in avoiding assumptions of infinite persistence, but nevertheless provides a lower bound on the extent of impact persistence that is robust to the numerous tests outlined above.

Committed damages until mid-century

We combine these empirical economic response functions (Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ) with an ensemble of 21 climate models (see Supplementary Table 5 ) from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP-6) 22 to project the macroeconomic damages from these components of physical climate change (see Methods for further details). Bias-adjusted climate models that provide a highly accurate reproduction of observed climatological patterns with limited uncertainty (Supplementary Table 6 ) are used to avoid introducing biases in the projections. Following a well-developed literature 2 , 3 , 19 , these projections do not aim to provide a prediction of future economic growth. Instead, they are a projection of the exogenous impact of future climate conditions on the economy relative to the baselines specified by socio-economic projections, based on the plausibly causal relationships inferred by the empirical models and assuming ceteris paribus. Other exogenous factors relevant for the prediction of economic output are purposefully assumed constant.

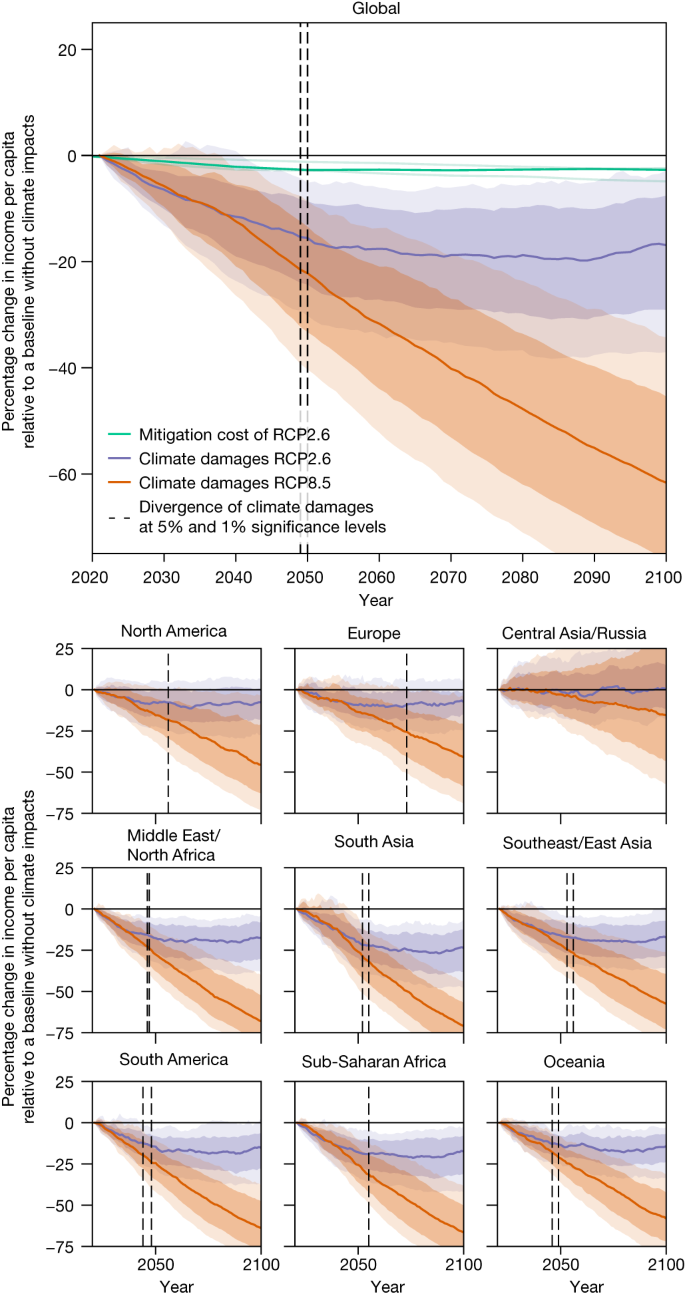

A Monte Carlo procedure that samples from climate model projections, empirical models with different numbers of lags and model parameter estimates (obtained by 1,000 block-bootstrap resamples of each of the regressions in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ) is used to estimate the combined uncertainty from these sources. Given these uncertainty distributions, we find that projected global damages are statistically indistinguishable across the two most extreme emission scenarios until 2049 (at the 5% significance level; Fig. 1 ). As such, the climate damages occurring before this time constitute those to which the world is already committed owing to the combination of past emissions and the range of future emission scenarios that are considered socio-economically plausible 15 . These committed damages comprise a permanent income reduction of 19% on average globally (population-weighted average) in comparison with a baseline without climate-change impacts (with a likely range of 11–29%, following the likelihood classification adopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); see caption of Fig. 1 ). Even though levels of income per capita generally still increase relative to those of today, this constitutes a permanent income reduction for most regions, including North America and Europe (each with median income reductions of approximately 11%) and with South Asia and Africa being the most strongly affected (each with median income reductions of approximately 22%; Fig. 1 ). Under a middle-of-the road scenario of future income development (SSP2, in which SSP stands for Shared Socio-economic Pathway), this corresponds to global annual damages in 2049 of 38 trillion in 2005 international dollars (likely range of 19–59 trillion 2005 international dollars). Compared with empirical specifications that assume pure growth or pure level effects, our preferred specification that provides a robust lower bound on the extent of climate impact persistence produces damages between these two extreme assumptions (Extended Data Fig. 3 ).

Estimates of the projected reduction in income per capita from changes in all climate variables based on empirical models of climate impacts on economic output with a robust lower bound on their persistence (Extended Data Fig. 1 ) under a low-emission scenario compatible with the 2 °C warming target and a high-emission scenario (SSP2-RCP2.6 and SSP5-RCP8.5, respectively) are shown in purple and orange, respectively. Shading represents the 34% and 10% confidence intervals reflecting the likely and very likely ranges, respectively (following the likelihood classification adopted by the IPCC), having estimated uncertainty from a Monte Carlo procedure, which samples the uncertainty from the choice of physical climate models, empirical models with different numbers of lags and bootstrapped estimates of the regression parameters shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 . Vertical dashed lines show the time at which the climate damages of the two emission scenarios diverge at the 5% and 1% significance levels based on the distribution of differences between emission scenarios arising from the uncertainty sampling discussed above. Note that uncertainty in the difference of the two scenarios is smaller than the combined uncertainty of the two respective scenarios because samples of the uncertainty (climate model and empirical model choice, as well as model parameter bootstrap) are consistent across the two emission scenarios, hence the divergence of damages occurs while the uncertainty bounds of the two separate damage scenarios still overlap. Estimates of global mitigation costs from the three IAMs that provide results for the SSP2 baseline and SSP2-RCP2.6 scenario are shown in light green in the top panel, with the median of these estimates shown in bold.

Damages already outweigh mitigation costs

We compare the damages to which the world is committed over the next 25 years to estimates of the mitigation costs required to achieve the Paris Climate Agreement. Taking estimates of mitigation costs from the three integrated assessment models (IAMs) in the IPCC AR6 database 23 that provide results under comparable scenarios (SSP2 baseline and SSP2-RCP2.6, in which RCP stands for Representative Concentration Pathway), we find that the median committed climate damages are larger than the median mitigation costs in 2050 (six trillion in 2005 international dollars) by a factor of approximately six (note that estimates of mitigation costs are only provided every 10 years by the IAMs and so a comparison in 2049 is not possible). This comparison simply aims to compare the magnitude of future damages against mitigation costs, rather than to conduct a formal cost–benefit analysis of transitioning from one emission path to another. Formal cost–benefit analyses typically find that the net benefits of mitigation only emerge after 2050 (ref. 5 ), which may lead some to conclude that physical damages from climate change are simply not large enough to outweigh mitigation costs until the second half of the century. Our simple comparison of their magnitudes makes clear that damages are actually already considerably larger than mitigation costs and the delayed emergence of net mitigation benefits results primarily from the fact that damages across different emission paths are indistinguishable until mid-century (Fig. 1 ).

Although these near-term damages constitute those to which the world is already committed, we note that damage estimates diverge strongly across emission scenarios after 2049, conveying the clear benefits of mitigation from a purely economic point of view that have been emphasized in previous studies 4 , 24 . As well as the uncertainties assessed in Fig. 1 , these conclusions are robust to structural choices, such as the timescale with which changes in the moderating variables of the empirical models are estimated (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11 ), as well as the order in which one accounts for the intertemporal and international components of currency comparison (Supplementary Fig. 12 ; see Methods for further details).

Damages from variability and extremes

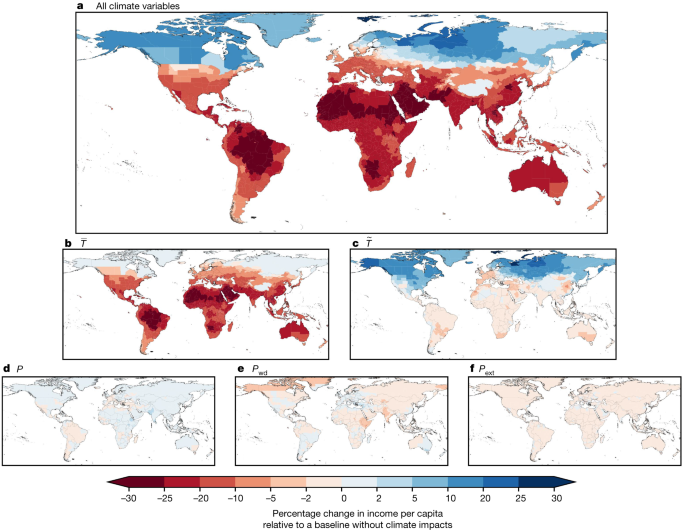

Committed damages primarily arise through changes in average temperature (Fig. 2 ). This reflects the fact that projected changes in average temperature are larger than those in other climate variables when expressed as a function of their historical interannual variability (Extended Data Fig. 4 ). Because the historical variability is that on which the empirical models are estimated, larger projected changes in comparison with this variability probably lead to larger future impacts in a purely statistical sense. From a mechanistic perspective, one may plausibly interpret this result as implying that future changes in average temperature are the most unprecedented from the perspective of the historical fluctuations to which the economy is accustomed and therefore will cause the most damage. This insight may prove useful in terms of guiding adaptation measures to the sources of greatest damage.

Estimates of the median projected reduction in sub-national income per capita across emission scenarios (SSP2-RCP2.6 and SSP2-RCP8.5) as well as climate model, empirical model and model parameter uncertainty in the year in which climate damages diverge at the 5% level (2049, as identified in Fig. 1 ). a , Impacts arising from all climate variables. b – f , Impacts arising separately from changes in annual mean temperature ( b ), daily temperature variability ( c ), total annual precipitation ( d ), the annual number of wet days (>1 mm) ( e ) and extreme daily rainfall ( f ) (see Methods for further definitions). Data on national administrative boundaries are obtained from the GADM database version 3.6 and are freely available for academic use ( https://gadm.org/ ).

Nevertheless, future damages based on empirical models that consider changes in annual average temperature only and exclude the other climate variables constitute income reductions of only 13% in 2049 (Extended Data Fig. 5a , likely range 5–21%). This suggests that accounting for the other components of the distribution of temperature and precipitation raises net damages by nearly 50%. This increase arises through the further damages that these climatic components cause, but also because their inclusion reveals a stronger negative economic response to average temperatures (Extended Data Fig. 5b ). The latter finding is consistent with our Monte Carlo simulations, which suggest that the magnitude of the effect of average temperature on economic growth is underestimated unless accounting for the impacts of other correlated climate variables (Supplementary Fig. 7 ).

In terms of the relative contributions of the different climatic components to overall damages, we find that accounting for daily temperature variability causes the largest increase in overall damages relative to empirical frameworks that only consider changes in annual average temperature (4.9 percentage points, likely range 2.4–8.7 percentage points, equivalent to approximately 10 trillion international dollars). Accounting for precipitation causes smaller increases in overall damages, which are—nevertheless—equivalent to approximately 1.2 trillion international dollars: 0.01 percentage points (−0.37–0.33 percentage points), 0.34 percentage points (0.07–0.90 percentage points) and 0.36 percentage points (0.13–0.65 percentage points) from total annual precipitation, the number of wet days and extreme daily precipitation, respectively. Moreover, climate models seem to underestimate future changes in temperature variability 25 and extreme precipitation 26 , 27 in response to anthropogenic forcing as compared with that observed historically, suggesting that the true impacts from these variables may be larger.

The distribution of committed damages

The spatial distribution of committed damages (Fig. 2a ) reflects a complex interplay between the patterns of future change in several climatic components and those of historical economic vulnerability to changes in those variables. Damages resulting from increasing annual mean temperature (Fig. 2b ) are negative almost everywhere globally, and larger at lower latitudes in regions in which temperatures are already higher and economic vulnerability to temperature increases is greatest (see the response heterogeneity to mean temperature embodied in Extended Data Fig. 1a ). This occurs despite the amplified warming projected at higher latitudes 28 , suggesting that regional heterogeneity in economic vulnerability to temperature changes outweighs heterogeneity in the magnitude of future warming (Supplementary Fig. 13a ). Economic damages owing to daily temperature variability (Fig. 2c ) exhibit a strong latitudinal polarisation, primarily reflecting the physical response of daily variability to greenhouse forcing in which increases in variability across lower latitudes (and Europe) contrast decreases at high latitudes 25 (Supplementary Fig. 13b ). These two temperature terms are the dominant determinants of the pattern of overall damages (Fig. 2a ), which exhibits a strong polarity with damages across most of the globe except at the highest northern latitudes. Future changes in total annual precipitation mainly bring economic benefits except in regions of drying, such as the Mediterranean and central South America (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 13c ), but these benefits are opposed by changes in the number of wet days, which produce damages with a similar pattern of opposite sign (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 13d ). By contrast, changes in extreme daily rainfall produce damages in all regions, reflecting the intensification of daily rainfall extremes over global land areas 29 , 30 (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 13e ).

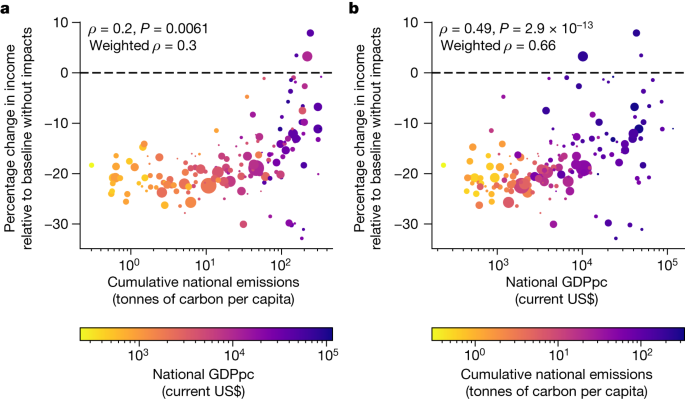

The spatial distribution of committed damages implies considerable injustice along two dimensions: culpability for the historical emissions that have caused climate change and pre-existing levels of socio-economic welfare. Spearman’s rank correlations indicate that committed damages are significantly larger in countries with smaller historical cumulative emissions, as well as in regions with lower current income per capita (Fig. 3 ). This implies that those countries that will suffer the most from the damages already committed are those that are least responsible for climate change and which also have the least resources to adapt to it.

Estimates of the median projected change in national income per capita across emission scenarios (RCP2.6 and RCP8.5) as well as climate model, empirical model and model parameter uncertainty in the year in which climate damages diverge at the 5% level (2049, as identified in Fig. 1 ) are plotted against cumulative national emissions per capita in 2020 (from the Global Carbon Project) and coloured by national income per capita in 2020 (from the World Bank) in a and vice versa in b . In each panel, the size of each scatter point is weighted by the national population in 2020 (from the World Bank). Inset numbers indicate the Spearman’s rank correlation ρ and P -values for a hypothesis test whose null hypothesis is of no correlation, as well as the Spearman’s rank correlation weighted by national population.

To further quantify this heterogeneity, we assess the difference in committed damages between the upper and lower quartiles of regions when ranked by present income levels and historical cumulative emissions (using a population weighting to both define the quartiles and estimate the group averages). On average, the quartile of countries with lower income are committed to an income loss that is 8.9 percentage points (or 61%) greater than the upper quartile (Extended Data Fig. 6 ), with a likely range of 3.8–14.7 percentage points across the uncertainty sampling of our damage projections (following the likelihood classification adopted by the IPCC). Similarly, the quartile of countries with lower historical cumulative emissions are committed to an income loss that is 6.9 percentage points (or 40%) greater than the upper quartile, with a likely range of 0.27–12 percentage points. These patterns reemphasize the prevalence of injustice in climate impacts 31 , 32 , 33 in the context of the damages to which the world is already committed by historical emissions and socio-economic inertia.

Contextualizing the magnitude of damages

The magnitude of projected economic damages exceeds previous literature estimates 2 , 3 , arising from several developments made on previous approaches. Our estimates are larger than those of ref. 2 (see first row of Extended Data Table 3 ), primarily because of the facts that sub-national estimates typically show a steeper temperature response (see also refs. 3 , 34 ) and that accounting for other climatic components raises damage estimates (Extended Data Fig. 5 ). However, we note that our empirical approach using first-differenced climate variables is conservative compared with that of ref. 2 in regard to the persistence of climate impacts on growth (see introduction and Methods section ‘Empirical model specification: fixed-effects distributed lag models’), an important determinant of the magnitude of long-term damages 19 , 21 . Using a similar empirical specification to ref. 2 , which assumes infinite persistence while maintaining the rest of our approach (sub-national data and further climate variables), produces considerably larger damages (purple curve of Extended Data Fig. 3 ). Compared with studies that do take the first difference of climate variables 3 , 35 , our estimates are also larger (see second and third rows of Extended Data Table 3 ). The inclusion of further climate variables (Extended Data Fig. 5 ) and a sufficient number of lags to more adequately capture the extent of impact persistence (Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2 ) are the main sources of this difference, as is the use of specifications that capture nonlinearities in the temperature response when compared with ref. 35 . In summary, our estimates develop on previous studies by incorporating the latest data and empirical insights 7 , 8 , as well as in providing a robust empirical lower bound on the persistence of impacts on economic growth, which constitutes a middle ground between the extremes of the growth-versus-levels debate 19 , 21 (Extended Data Fig. 3 ).

Compared with the fraction of variance explained by the empirical models historically (<5%), the projection of reductions in income of 19% may seem large. This arises owing to the fact that projected changes in climatic conditions are much larger than those that were experienced historically, particularly for changes in average temperature (Extended Data Fig. 4 ). As such, any assessment of future climate-change impacts necessarily requires an extrapolation outside the range of the historical data on which the empirical impact models were evaluated. Nevertheless, these models constitute the most state-of-the-art methods for inference of plausibly causal climate impacts based on observed data. Moreover, we take explicit steps to limit out-of-sample extrapolation by capping the moderating variables of the interaction terms at the 95th percentile of the historical distribution (see Methods ). This avoids extrapolating the marginal effects outside what was observed historically. Given the nonlinear response of economic output to annual mean temperature (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 2 ), this is a conservative choice that limits the magnitude of damages that we project. Furthermore, back-of-the-envelope calculations indicate that the projected damages are consistent with the magnitude and patterns of historical economic development (see Supplementary Discussion Section 5 ).

Missing impacts and spatial spillovers

Despite assessing several climatic components from which economic impacts have recently been identified 3 , 7 , 8 , this assessment of aggregate climate damages should not be considered comprehensive. Important channels such as impacts from heatwaves 31 , sea-level rise 36 , tropical cyclones 37 and tipping points 38 , 39 , as well as non-market damages such as those to ecosystems 40 and human health 41 , are not considered in these estimates. Sea-level rise is unlikely to be feasibly incorporated into empirical assessments such as this because historical sea-level variability is mostly small. Non-market damages are inherently intractable within our estimates of impacts on aggregate monetary output and estimates of these impacts could arguably be considered as extra to those identified here. Recent empirical work suggests that accounting for these channels would probably raise estimates of these committed damages, with larger damages continuing to arise in the global south 31 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 .

Moreover, our main empirical analysis does not explicitly evaluate the potential for impacts in local regions to produce effects that ‘spill over’ into other regions. Such effects may further mitigate or amplify the impacts we estimate, for example, if companies relocate production from one affected region to another or if impacts propagate along supply chains. The current literature indicates that trade plays a substantial role in propagating spillover effects 43 , 44 , making their assessment at the sub-national level challenging without available data on sub-national trade dependencies. Studies accounting for only spatially adjacent neighbours indicate that negative impacts in one region induce further negative impacts in neighbouring regions 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , suggesting that our projected damages are probably conservative by excluding these effects. In Supplementary Fig. 14 , we assess spillovers from neighbouring regions using a spatial-lag model. For simplicity, this analysis excludes temporal lags, focusing only on contemporaneous effects. The results show that accounting for spatial spillovers can amplify the overall magnitude, and also the heterogeneity, of impacts. Consistent with previous literature, this indicates that the overall magnitude (Fig. 1 ) and heterogeneity (Fig. 3 ) of damages that we project in our main specification may be conservative without explicitly accounting for spillovers. We note that further analysis that addresses both spatially and trade-connected spillovers, while also accounting for delayed impacts using temporal lags, would be necessary to adequately address this question fully. These approaches offer fruitful avenues for further research but are beyond the scope of this manuscript, which primarily aims to explore the impacts of different climate conditions and their persistence.

Policy implications

We find that the economic damages resulting from climate change until 2049 are those to which the world economy is already committed and that these greatly outweigh the costs required to mitigate emissions in line with the 2 °C target of the Paris Climate Agreement (Fig. 1 ). This assessment is complementary to formal analyses of the net costs and benefits associated with moving from one emission path to another, which typically find that net benefits of mitigation only emerge in the second half of the century 5 . Our simple comparison of the magnitude of damages and mitigation costs makes clear that this is primarily because damages are indistinguishable across emissions scenarios—that is, committed—until mid-century (Fig. 1 ) and that they are actually already much larger than mitigation costs. For simplicity, and owing to the availability of data, we compare damages to mitigation costs at the global level. Regional estimates of mitigation costs may shed further light on the national incentives for mitigation to which our results already hint, of relevance for international climate policy. Although these damages are committed from a mitigation perspective, adaptation may provide an opportunity to reduce them. Moreover, the strong divergence of damages after mid-century reemphasizes the clear benefits of mitigation from a purely economic perspective, as highlighted in previous studies 1 , 4 , 6 , 24 .

Historical climate data

Historical daily 2-m temperature and precipitation totals (in mm) are obtained for the period 1979–2019 from the W5E5 database. The W5E5 dataset comes from ERA-5, a state-of-the-art reanalysis of historical observations, but has been bias-adjusted by applying version 2.0 of the WATCH Forcing Data to ERA-5 reanalysis data and precipitation data from version 2.3 of the Global Precipitation Climatology Project to better reflect ground-based measurements 49 , 50 , 51 . We obtain these data on a 0.5° × 0.5° grid from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP) database. Notably, these historical data have been used to bias-adjust future climate projections from CMIP-6 (see the following section), ensuring consistency between the distribution of historical daily weather on which our empirical models were estimated and the climate projections used to estimate future damages. These data are publicly available from the ISIMIP database. See refs. 7 , 8 for robustness tests of the empirical models to the choice of climate data reanalysis products.

Future climate data

Daily 2-m temperature and precipitation totals (in mm) are taken from 21 climate models participating in CMIP-6 under a high (RCP8.5) and a low (RCP2.6) greenhouse gas emission scenario from 2015 to 2100. The data have been bias-adjusted and statistically downscaled to a common half-degree grid to reflect the historical distribution of daily temperature and precipitation of the W5E5 dataset using the trend-preserving method developed by the ISIMIP 50 , 52 . As such, the climate model data reproduce observed climatological patterns exceptionally well (Supplementary Table 5 ). Gridded data are publicly available from the ISIMIP database.

Historical economic data

Historical economic data come from the DOSE database of sub-national economic output 53 . We use a recent revision to the DOSE dataset that provides data across 83 countries, 1,660 sub-national regions with varying temporal coverage from 1960 to 2019. Sub-national units constitute the first administrative division below national, for example, states for the USA and provinces for China. Data come from measures of gross regional product per capita (GRPpc) or income per capita in local currencies, reflecting the values reported in national statistical agencies, yearbooks and, in some cases, academic literature. We follow previous literature 3 , 7 , 8 , 54 and assess real sub-national output per capita by first converting values from local currencies to US dollars to account for diverging national inflationary tendencies and then account for US inflation using a US deflator. Alternatively, one might first account for national inflation and then convert between currencies. Supplementary Fig. 12 demonstrates that our conclusions are consistent when accounting for price changes in the reversed order, although the magnitude of estimated damages varies. See the documentation of the DOSE dataset for further discussion of these choices. Conversions between currencies are conducted using exchange rates from the FRED database of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 55 and the national deflators from the World Bank 56 .

Future socio-economic data

Baseline gridded gross domestic product (GDP) and population data for the period 2015–2100 are taken from the middle-of-the-road scenario SSP2 (ref. 15 ). Population data have been downscaled to a half-degree grid by the ISIMIP following the methodologies of refs. 57 , 58 , which we then aggregate to the sub-national level of our economic data using the spatial aggregation procedure described below. Because current methodologies for downscaling the GDP of the SSPs use downscaled population to do so, per-capita estimates of GDP with a realistic distribution at the sub-national level are not readily available for the SSPs. We therefore use national-level GDP per capita (GDPpc) projections for all sub-national regions of a given country, assuming homogeneity within countries in terms of baseline GDPpc. Here we use projections that have been updated to account for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the trajectory of future income, while remaining consistent with the long-term development of the SSPs 59 . The choice of baseline SSP alters the magnitude of projected climate damages in monetary terms, but when assessed in terms of percentage change from the baseline, the choice of socio-economic scenario is inconsequential. Gridded SSP population data and national-level GDPpc data are publicly available from the ISIMIP database. Sub-national estimates as used in this study are available in the code and data replication files.

Climate variables

Following recent literature 3 , 7 , 8 , we calculate an array of climate variables for which substantial impacts on macroeconomic output have been identified empirically, supported by further evidence at the micro level for plausible underlying mechanisms. See refs. 7 , 8 for an extensive motivation for the use of these particular climate variables and for detailed empirical tests on the nature and robustness of their effects on economic output. To summarize, these studies have found evidence for independent impacts on economic growth rates from annual average temperature, daily temperature variability, total annual precipitation, the annual number of wet days and extreme daily rainfall. Assessments of daily temperature variability were motivated by evidence of impacts on agricultural output and human health, as well as macroeconomic literature on the impacts of volatility on growth when manifest in different dimensions, such as government spending, exchange rates and even output itself 7 . Assessments of precipitation impacts were motivated by evidence of impacts on agricultural productivity, metropolitan labour outcomes and conflict, as well as damages caused by flash flooding 8 . See Extended Data Table 1 for detailed references to empirical studies of these physical mechanisms. Marked impacts of daily temperature variability, total annual precipitation, the number of wet days and extreme daily rainfall on macroeconomic output were identified robustly across different climate datasets, spatial aggregation schemes, specifications of regional time trends and error-clustering approaches. They were also found to be robust to the consideration of temperature extremes 7 , 8 . Furthermore, these climate variables were identified as having independent effects on economic output 7 , 8 , which we further explain here using Monte Carlo simulations to demonstrate the robustness of the results to concerns of imperfect multicollinearity between climate variables (Supplementary Methods Section 2 ), as well as by using information criteria (Supplementary Table 1 ) to demonstrate that including several lagged climate variables provides a preferable trade-off between optimally describing the data and limiting the possibility of overfitting.

We calculate these variables from the distribution of daily, d , temperature, T x , d , and precipitation, P x , d , at the grid-cell, x , level for both the historical and future climate data. As well as annual mean temperature, \({\bar{T}}_{x,y}\) , and annual total precipitation, P x , y , we calculate annual, y , measures of daily temperature variability, \({\widetilde{T}}_{x,y}\) :

the number of wet days, Pwd x , y :

and extreme daily rainfall:

in which T x , d , m , y is the grid-cell-specific daily temperature in month m and year y , \({\bar{T}}_{x,m,{y}}\) is the year and grid-cell-specific monthly, m , mean temperature, D m and D y the number of days in a given month m or year y , respectively, H the Heaviside step function, 1 mm the threshold used to define wet days and P 99.9 x is the 99.9th percentile of historical (1979–2019) daily precipitation at the grid-cell level. Units of the climate measures are degrees Celsius for annual mean temperature and daily temperature variability, millimetres for total annual precipitation and extreme daily precipitation, and simply the number of days for the annual number of wet days.

We also calculated weighted standard deviations of monthly rainfall totals as also used in ref. 8 but do not include them in our projections as we find that, when accounting for delayed effects, their effect becomes statistically indistinct and is better captured by changes in total annual rainfall.

Spatial aggregation

We aggregate grid-cell-level historical and future climate measures, as well as grid-cell-level future GDPpc and population, to the level of the first administrative unit below national level of the GADM database, using an area-weighting algorithm that estimates the portion of each grid cell falling within an administrative boundary. We use this as our baseline specification following previous findings that the effect of area or population weighting at the sub-national level is negligible 7 , 8 .

Empirical model specification: fixed-effects distributed lag models

Following a wide range of climate econometric literature 16 , 60 , we use panel regression models with a selection of fixed effects and time trends to isolate plausibly exogenous variation with which to maximize confidence in a causal interpretation of the effects of climate on economic growth rates. The use of region fixed effects, μ r , accounts for unobserved time-invariant differences between regions, such as prevailing climatic norms and growth rates owing to historical and geopolitical factors. The use of yearly fixed effects, η y , accounts for regionally invariant annual shocks to the global climate or economy such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation or global recessions. In our baseline specification, we also include region-specific linear time trends, k r y , to exclude the possibility of spurious correlations resulting from common slow-moving trends in climate and growth.

The persistence of climate impacts on economic growth rates is a key determinant of the long-term magnitude of damages. Methods for inferring the extent of persistence in impacts on growth rates have typically used lagged climate variables to evaluate the presence of delayed effects or catch-up dynamics 2 , 18 . For example, consider starting from a model in which a climate condition, C r , y , (for example, annual mean temperature) affects the growth rate, Δlgrp r , y (the first difference of the logarithm of gross regional product) of region r in year y :

which we refer to as a ‘pure growth effects’ model in the main text. Typically, further lags are included,

and the cumulative effect of all lagged terms is evaluated to assess the extent to which climate impacts on growth rates persist. Following ref. 18 , in the case that,

the implication is that impacts on the growth rate persist up to NL years after the initial shock (possibly to a weaker or a stronger extent), whereas if

then the initial impact on the growth rate is recovered after NL years and the effect is only one on the level of output. However, we note that such approaches are limited by the fact that, when including an insufficient number of lags to detect a recovery of the growth rates, one may find equation ( 6 ) to be satisfied and incorrectly assume that a change in climatic conditions affects the growth rate indefinitely. In practice, given a limited record of historical data, including too few lags to confidently conclude in an infinitely persistent impact on the growth rate is likely, particularly over the long timescales over which future climate damages are often projected 2 , 24 . To avoid this issue, we instead begin our analysis with a model for which the level of output, lgrp r , y , depends on the level of a climate variable, C r , y :

Given the non-stationarity of the level of output, we follow the literature 19 and estimate such an equation in first-differenced form as,

which we refer to as a model of ‘pure level effects’ in the main text. This model constitutes a baseline specification in which a permanent change in the climate variable produces an instantaneous impact on the growth rate and a permanent effect only on the level of output. By including lagged variables in this specification,

we are able to test whether the impacts on the growth rate persist any further than instantaneously by evaluating whether α L > 0 are statistically significantly different from zero. Even though this framework is also limited by the possibility of including too few lags, the choice of a baseline model specification in which impacts on the growth rate do not persist means that, in the case of including too few lags, the framework reverts to the baseline specification of level effects. As such, this framework is conservative with respect to the persistence of impacts and the magnitude of future damages. It naturally avoids assumptions of infinite persistence and we are able to interpret any persistence that we identify with equation ( 9 ) as a lower bound on the extent of climate impact persistence on growth rates. See the main text for further discussion of this specification choice, in particular about its conservative nature compared with previous literature estimates, such as refs. 2 , 18 .

We allow the response to climatic changes to vary across regions, using interactions of the climate variables with historical average (1979–2019) climatic conditions reflecting heterogenous effects identified in previous work 7 , 8 . Following this previous work, the moderating variables of these interaction terms constitute the historical average of either the variable itself or of the seasonal temperature difference, \({\hat{T}}_{r}\) , or annual mean temperature, \({\bar{T}}_{r}\) , in the case of daily temperature variability 7 and extreme daily rainfall, respectively 8 .

The resulting regression equation with N and M lagged variables, respectively, reads:

in which Δlgrp r , y is the annual, regional GRPpc growth rate, measured as the first difference of the logarithm of real GRPpc, following previous work 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 18 , 19 . Fixed-effects regressions were run using the fixest package in R (ref. 61 ).

Estimates of the coefficients of interest α i , L are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1 for N = M = 10 lags and for our preferred choice of the number of lags in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 . In Extended Data Fig. 1 , errors are shown clustered at the regional level, but for the construction of damage projections, we block-bootstrap the regressions by region 1,000 times to provide a range of parameter estimates with which to sample the projection uncertainty (following refs. 2 , 31 ).

Spatial-lag model

In Supplementary Fig. 14 , we present the results from a spatial-lag model that explores the potential for climate impacts to ‘spill over’ into spatially neighbouring regions. We measure the distance between centroids of each pair of sub-national regions and construct spatial lags that take the average of the first-differenced climate variables and their interaction terms over neighbouring regions that are at distances of 0–500, 500–1,000, 1,000–1,500 and 1,500–2000 km (spatial lags, ‘SL’, 1 to 4). For simplicity, we then assess a spatial-lag model without temporal lags to assess spatial spillovers of contemporaneous climate impacts. This model takes the form:

in which SL indicates the spatial lag of each climate variable and interaction term. In Supplementary Fig. 14 , we plot the cumulative marginal effect of each climate variable at different baseline climate conditions by summing the coefficients for each climate variable and interaction term, for example, for average temperature impacts as:

These cumulative marginal effects can be regarded as the overall spatially dependent impact to an individual region given a one-unit shock to a climate variable in that region and all neighbouring regions at a given value of the moderating variable of the interaction term.

Constructing projections of economic damage from future climate change

We construct projections of future climate damages by applying the coefficients estimated in equation ( 10 ) and shown in Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 (when including only lags with statistically significant effects in specifications that limit overfitting; see Supplementary Methods Section 1 ) to projections of future climate change from the CMIP-6 models. Year-on-year changes in each primary climate variable of interest are calculated to reflect the year-to-year variations used in the empirical models. 30-year moving averages of the moderating variables of the interaction terms are calculated to reflect the long-term average of climatic conditions that were used for the moderating variables in the empirical models. By using moving averages in the projections, we account for the changing vulnerability to climate shocks based on the evolving long-term conditions (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11 show that the results are robust to the precise choice of the window of this moving average). Although these climate variables are not differenced, the fact that the bias-adjusted climate models reproduce observed climatological patterns across regions for these moderating variables very accurately (Supplementary Table 6 ) with limited spread across models (<3%) precludes the possibility that any considerable bias or uncertainty is introduced by this methodological choice. However, we impose caps on these moderating variables at the 95th percentile at which they were observed in the historical data to prevent extrapolation of the marginal effects outside the range in which the regressions were estimated. This is a conservative choice that limits the magnitude of our damage projections.

Time series of primary climate variables and moderating climate variables are then combined with estimates of the empirical model parameters to evaluate the regression coefficients in equation ( 10 ), producing a time series of annual GRPpc growth-rate reductions for a given emission scenario, climate model and set of empirical model parameters. The resulting time series of growth-rate impacts reflects those occurring owing to future climate change. By contrast, a future scenario with no climate change would be one in which climate variables do not change (other than with random year-to-year fluctuations) and hence the time-averaged evaluation of equation ( 10 ) would be zero. Our approach therefore implicitly compares the future climate-change scenario to this no-climate-change baseline scenario.

The time series of growth-rate impacts owing to future climate change in region r and year y , δ r , y , are then added to the future baseline growth rates, π r , y (in log-diff form), obtained from the SSP2 scenario to yield trajectories of damaged GRPpc growth rates, ρ r , y . These trajectories are aggregated over time to estimate the future trajectory of GRPpc with future climate impacts:

in which GRPpc r , y =2020 is the initial log level of GRPpc. We begin damage estimates in 2020 to reflect the damages occurring since the end of the period for which we estimate the empirical models (1979–2019) and to match the timing of mitigation-cost estimates from most IAMs (see below).

For each emission scenario, this procedure is repeated 1,000 times while randomly sampling from the selection of climate models, the selection of empirical models with different numbers of lags (shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ) and bootstrapped estimates of the regression parameters. The result is an ensemble of future GRPpc trajectories that reflect uncertainty from both physical climate change and the structural and sampling uncertainty of the empirical models.

Estimates of mitigation costs

We obtain IPCC estimates of the aggregate costs of emission mitigation from the AR6 Scenario Explorer and Database hosted by IIASA 23 . Specifically, we search the AR6 Scenarios Database World v1.1 for IAMs that provided estimates of global GDP and population under both a SSP2 baseline and a SSP2-RCP2.6 scenario to maintain consistency with the socio-economic and emission scenarios of the climate damage projections. We find five IAMs that provide data for these scenarios, namely, MESSAGE-GLOBIOM 1.0, REMIND-MAgPIE 1.5, AIM/GCE 2.0, GCAM 4.2 and WITCH-GLOBIOM 3.1. Of these five IAMs, we use the results only from the first three that passed the IPCC vetting procedure for reproducing historical emission and climate trajectories. We then estimate global mitigation costs as the percentage difference in global per capita GDP between the SSP2 baseline and the SSP2-RCP2.6 emission scenario. In the case of one of these IAMs, estimates of mitigation costs begin in 2020, whereas in the case of two others, mitigation costs begin in 2010. The mitigation cost estimates before 2020 in these two IAMs are mostly negligible, and our choice to begin comparison with damage estimates in 2020 is conservative with respect to the relative weight of climate damages compared with mitigation costs for these two IAMs.

Data availability

Data on economic production and ERA-5 climate data are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4681306 (ref. 62 ) and https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets/reanalysis-datasets/era5 , respectively. Data on mitigation costs are publicly available at https://data.ene.iiasa.ac.at/ar6/#/downloads . Processed climate and economic data, as well as all other necessary data for reproduction of the results, are available at the public repository https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10562951 (ref. 63 ).

Code availability

All code necessary for reproduction of the results is available at the public repository https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10562951 (ref. 63 ).

Glanemann, N., Willner, S. N. & Levermann, A. Paris Climate Agreement passes the cost-benefit test. Nat. Commun. 11 , 110 (2020).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527 , 235–239 (2015).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kalkuhl, M. & Wenz, L. The impact of climate conditions on economic production. Evidence from a global panel of regions. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 103 , 102360 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Moore, F. C. & Diaz, D. B. Temperature impacts on economic growth warrant stringent mitigation policy. Nat. Clim. Change 5 , 127–131 (2015).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Drouet, L., Bosetti, V. & Tavoni, M. Net economic benefits of well-below 2°C scenarios and associated uncertainties. Oxf. Open Clim. Change 2 , kgac003 (2022).

Ueckerdt, F. et al. The economically optimal warming limit of the planet. Earth Syst. Dyn. 10 , 741–763 (2019).

Kotz, M., Wenz, L., Stechemesser, A., Kalkuhl, M. & Levermann, A. Day-to-day temperature variability reduces economic growth. Nat. Clim. Change 11 , 319–325 (2021).

Kotz, M., Levermann, A. & Wenz, L. The effect of rainfall changes on economic production. Nature 601 , 223–227 (2022).

Kousky, C. Informing climate adaptation: a review of the economic costs of natural disasters. Energy Econ. 46 , 576–592 (2014).

Harlan, S. L. et al. in Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives (eds Dunlap, R. E. & Brulle, R. J.) 127–163 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2015).

Bolton, P. et al. The Green Swan (BIS Books, 2020).

Alogoskoufis, S. et al. ECB Economy-wide Climate Stress Test: Methodology and Results European Central Bank, 2021).

Weber, E. U. What shapes perceptions of climate change? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 1 , 332–342 (2010).

Markowitz, E. M. & Shariff, A. F. Climate change and moral judgement. Nat. Clim. Change 2 , 243–247 (2012).

Riahi, K. et al. The shared socioeconomic pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42 , 153–168 (2017).

Auffhammer, M., Hsiang, S. M., Schlenker, W. & Sobel, A. Using weather data and climate model output in economic analyses of climate change. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 7 , 181–198 (2013).

Kolstad, C. D. & Moore, F. C. Estimating the economic impacts of climate change using weather observations. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 14 , 1–24 (2020).