Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 Planning Your Research: Reviewing the Literature and Developing Questions

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What is relevant literature? What are the best ways to find it?

- What are the best ways to organize your relevant literature?

- What are the intended outcomes of reviewing your relevant literature?

Nearly all research begins with a review of literature that is relevant to the topic of research, even if it is only a casual review. Reviewing the available literature on your topic is a vital step in the research process. The literature review process provides an anchor for your inquiry. O’Leary (2004, p. 66) states, the “production of new knowledge is fundamentally dependent on past knowledge” because “it is virtually impossible for researchers to add to a body of literature if they are not conversant with it.” By reviewing the literature in the initial stages of the inquiry process, researchers are better able to:

- Understand their topic;

- Develop and focus a topic;

- Provide a clear rationale for, or better situate, their topic;

- Fine-tune their research questions.

In terms of thinking about methodology and the actual research process, reviewing the literature can help researchers:

- Identify well-vetted data collection and analysis methods on their topic;

- Determine whether to replicate a previous study, or develop a completely new study;

- Add rigor and validity to the research by validating the topic, methods, and significance.

Lastly, reviewing the literature also helps the researcher make sense of their findings, in both their field of study and in their educational context, by:

- Assessing whether the findings correlate with findings from another study;

- Determining which of the findings are different than previous studies;

- Determining which of the findings are unique to the researcher’s educational context. [1]

As you may see, the literature review is the backbone, anchor, or foundation of your research study. Overall the review of literature helps you answer three important questions that are the result of the bullet points outlined above. The literature review helps you answer the following:

- What do we know about your topic?

- What do we not know about your topic?

- How does your research address the gap between what we know and what we don’t about your topic?

After reviewing the literature, if you are able to answer those three questions, you will have a very clear and well-rationalized justification for your inquiry. If you cannot answer those questions, then you should probably keep reviewing the literature by looking for related topics or synonyms of major concepts.

While an extensive review of the literature about your topic of study is expected, you should also be realistic as to what you are able to manage. For topics that have a lot of research literature available, make sure you establish parameters for your research, such as:

- Temporal (e.g., only articles in the last 5 or 10 years)

- Content Area (e.g., only in science and math classrooms)

- Age or grade (e.g., only middle school classrooms)

- Research Subject (e.g., girls only, teachers, struggling readers)

These categories provide only a few examples, but parameters like these can make your review of literature much more manageable and your study much more focused.

What Types of Literature Should You Consider in Your Review?

It is helpful to consider the characteristics, purposes, and outcomes of different types of literature. Below are four broad categories I identify within educational research literature. I want to emphasize that my categories are in no way definitive, and only represent my own understanding.

Policy-Based Literature

Policy-based literature includes official documents that outline education policy with which the practitioner needs to be familiar. For example, the Common Core Standards or Content Standards are often refenced in articles to situate the need for research in relation to the standards; if my topic was on place-based education with middle school social studies students, I might have to look at national social studies standards. There also may be initiatives launched by organizations or researchers that become accepted practice. The documents that launch these initiatives (e.g., reports, articles, speeches) would also be useful to review. An example would be the Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read report from the National Reading Panel. These documents may provide rationale, based on the theories and concepts they utilize, and they may provide new ways of thinking about your topic. Similarly, if your topic is based on the local context, recent newspaper articles could also provide policy-type insights. All of these policy-based insights will be useful in providing the landscape or background for your work.

Theoretical Literature

Once you have identified your theoretical perspective, it is also important to locate your research within the appropriate theoretical literature. Many of you may be engaged in highly practice-based or small-scale research and wonder if you need a theoretical basis in your literature review. Regardless of the extent of your project, theoretical literature will help with the rigor and validity of your study and will help identify any theoretical views that underlie your topic. For example, if your study focuses on the place-based education in enhancing social studies students’ learning, it is highly probable that you would cite Kolb’s (1984/2014) work on Experiential Learning. By using Kolb’s work, you situate your research theoretically in the area of experiential learning.

Applicable Literature

Applicable literature will account for the bulk of your literature review. The previous two types of literature provide indication as to where your research is rationalized professionally and situated theoretically. Applicable literature will mainly come from journals related to your specific field of study. If I was doing a study in a social studies classroom, I would look at the journals The Social Studies, Social Education, and Social Studies Research and Practice . Use Google Scholar or your university library databases to examine literature in your specific area. When using these search engines and databases, start as specific as possible with your topic and related concepts. Using the example of place-based learning from above, I would search for “place-based learning” and “social studies” and “middle school” and “historic sites”. If I did not find many articles with this first search, then I would remove “historic sites” and search again. Books or handbooks on research may also have some useful studies to support your literature review section.

Methodological Literature

When sharing or reporting your work, you will want to review and cite research methodology literature to justify the methods you chose. When reading other research articles, pay attention to the research methods used by researchers. It is especially important to find articles that use and cite action research methodology. This type of literature will provide further support of your data gathering and analysis methods. Again, your methods should fit within your theoretical and epistemological stances. In addition, you’ll want to review data collection methods and potentially borrow or adapt rubrics or surveys from other studies.

Sources of Relevant Literature

When searching for these four types of literature, there are two ways to think about possible sources:

- primary sources include government publications, policy documents, research papers, dissertations, conference presentations and institutional occasional papers with accounts of research;

- secondary sources use primary sources as references, such as papers written for professional conferences and journals, books written for practicing professionals and book reviews. This is often called “reference mining” as you look through the reference lists of other studies and then return to the primary source that was cited.

Secondary sources are often just as valuable as primary sources, or potentially more valuable. When beginning your search, secondary sources can provide links to a wealth of primary sources that the secondary source author has already vetted for you, and likely with similar intentions. This is especially true of research handbooks. You will come across both types of literature wherever you search, and they both provide a landscape for your topic and add value to your literature review.

Regardless of being a primary or secondary source, you want to make sure the literature you review is peer-reviewed. Peer-reviewed simply means that the article was reviewed by two to three scholars in the field before it was published. Books, or edited books, would have also gone through a peer-review process. We often recommend teachers to look at professional books from reputable publishing companies and professional organizations, such as ASCD, NCTE, NCTM, or NCSS. This is a way for scholars to objectively review each other’s work to maintain a high level of quality and ethics in the publication of research. Most databases have mostly peer-reviewed journals, and often provide a filter to sort out the non-peer-reviewed journals.

Using the Internet

The internet is a valuable research tool and is becoming increasingly efficient and reliable in providing peer-reviewed literature. Sites like Google Scholar are especially useful. Often, and depending on the topic, the downside of internet-based searches is that it will generate thousands or millions of sources. This can be overwhelming, especially for new researchers, and you will have to develop ways to narrow down the results.

Professional organization websites will also have resources or links to sources that have typically been vetted. With all internet sources, you should evaluate the information for credibility and authority.

Evaluating sources from the Internet

Evaluating internet sources is a whole field of study and research within itself, and an in-depth discussion would take away from the focus of this book. However, O’ Dochartaigh (2007) provides a chapter to help guide the internet source evaluation process. Here is a brief summary, based on O’ Dochartaigh’s book, to give you a general idea of the task of evaluating sources:

- Examine if the material belongs to an advocacy group. Many times, these sources are fine, however, they require extra examination for bias or funding interests.

- As mentioned above, many academic papers are published in refereed journals which are subject to peer-review. Papers found on academic or university websites are typically refereed in some manner; however, some papers are posted by academics on their personal sites and have not been reviewed by other academics. Papers published solely by academics or other experts require further scrutiny before citing.

- When you are reviewing newspaper and magazine articles from the internet be weary of potential conflicts of interest based on the political stance of that periodical.

Therefore, it is wise to consider the objectivity of any source you find on the internet before you accept the literature.

We always recommend that students consider a few questions in their evaluation of sources, which are similar to the formal questions outlined by O’ Dochartaigh (2007):

- Is it clear who is responsible for the document?

- Is there any information about the person or organization responsible for the page?

- Is there a copyright statement?

- Does it have other publications that reinforce its authority?

- Are the sources clearly listed so they can be verified?

- Is there an editorial involvement?

- Are the spelling and grammar correct?

- Are biases and affiliations clearly stated?

- Are there dates for when the document was last updated or revised?

Organizing your Literature

When you begin, here are some things to think about as your read the literature. Again, these are not definitive, but merely provided for guidance. These questions are especially focused on other action research literature:

Questions to Think about as You Examine the Literature

- What was the context of their research?

- Who was involved? Was it a collaborative project?

- Was the choice of using action research as a method justified? Are any models discussed?

- What ‘actions’ actually took place?

- How was data gathered?

- How was data analyzed?

- Were ethical considerations addressed? How?

- What were the conclusions? Were they justified using appropriate evidence?

- Was the report accessible? Useful?

- Is it possible to replicate the study?

Regardless of the amount of literature you review, your challenge will be to organize the literature in way that is manageable and easy to reference. It is important to keep a record of what you read and how it relates conceptually to your topic. Some researchers even use the questions above to organize their literature. It is easy to read and think about the content of an article by making brief notes, however, this is often not enough to initially begin to develop your study or write about your findings. I will state the obvious here: organizing your literature search efficiently from the start is vital!

No matter how you choose to record or document the articles you read (e.g., paper, computer, photo), I would suggest thinking about the format in terms of index cards. Index cards are a very practical and simple model because the space limits you to be precise in recording vital information about each article. I typically create a document on my computer, allow each article the space of an index card, and focus on recording the following information:

- Journal/Book Chapter Title

- Main Arguments/Key findings

- Pertinent Quote(s)

- Implications

- Connective Points (how does it relate to my work and/or other articles)

I find that these aspects provide the information I need to be refreshed on the article and to be able to use it upon review.

There are also a lot of computer applications that are very useful and efficient in managing your literature. For example, Mendeley © provides comprehensive support for reviewing literature, even allowing you to store the article itself and make comments or highlights in text. There are also many citation apps that are helpful if you continue this research agenda and use roughly the same literature for each project.

Using the Literature

Think ahead to when you have collected and read a good amount of literature on your topic. You are now ready to use the literature to think about your topic, your research question, and the methods you plan to use. It might be helpful to peek ahead to Chapter 7 where I discuss writing the literature review for a report to give you an idea of the end goal. The primary purpose of engaging in a literature review is to provide knowledge to construct a framework for understanding the landscape of your topic. I often suggest for students to think of it as constructing an argument for your research decisions, or as if you are telling a story of how we got to this point in researching your topic. Either way you are situating your research in what we know and don’t know about your topic.

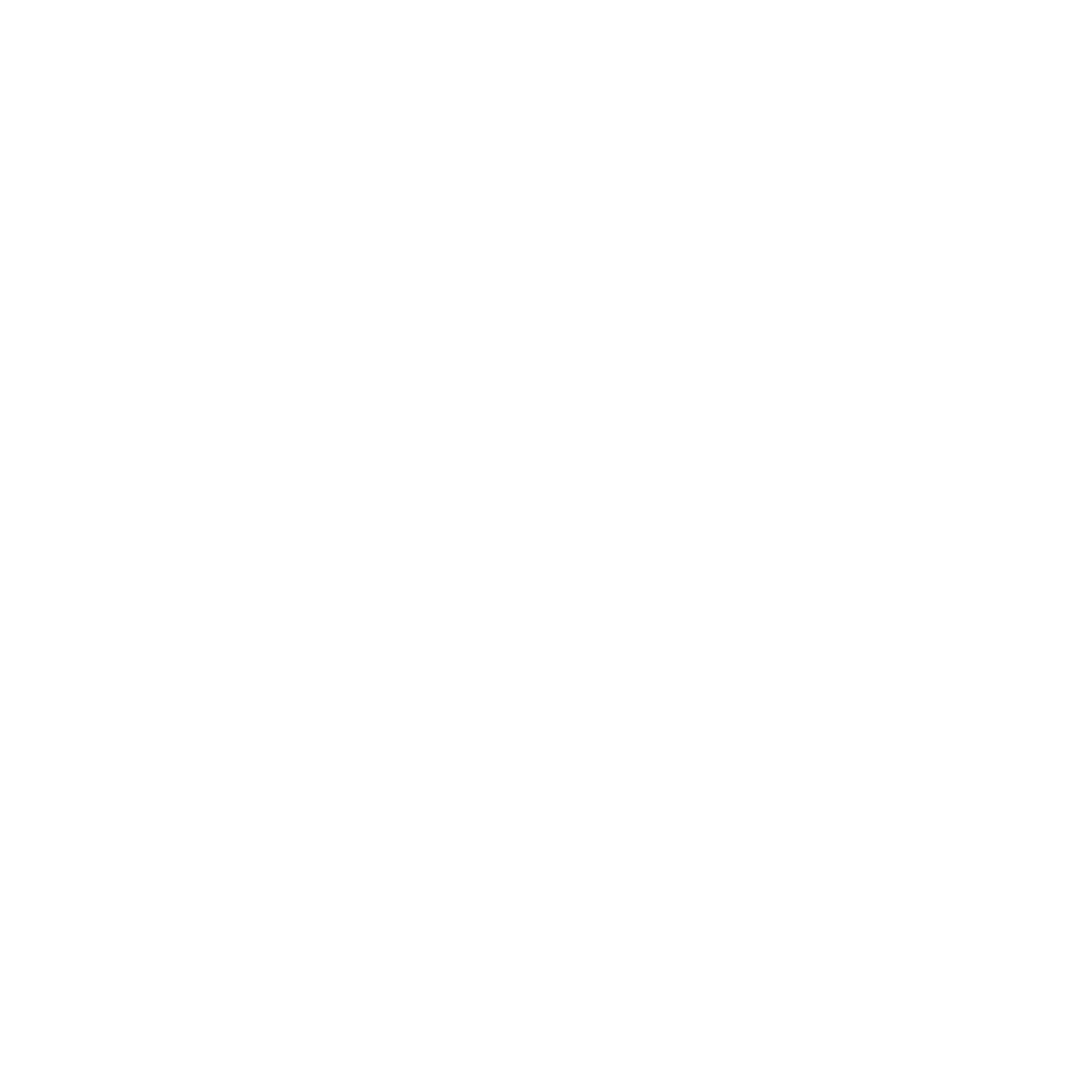

Naturally we tend to think about, and potentially write about, the literature in relation to the article’s author (e.g. Clark and Porath (2016) found that…). However, more commonly today in educational research you will find that literature reviews are organized by themes. It can be a little more organic to think about literature in terms of themes because they emerge or become more defined as you read. Also thinking thematically allows the articles to naturally connect and build on each other, whereas thinking in terms of authors can fragment thinking about the topic. In terms of thinking thematically, here are some guidelines:

- Identify the significant themes that have emerged organically from the literature review. These themes would be concepts or ideas that you typed or wrote down in your note-taking or management system.

- Introduce the common concepts or ideas by themes, instead of by authors’ disjointed viewpoints. Paragraphs in a thematic literature review begin like: The research on teacher self-efficacy has identified several key factors that contribute to strong self-efficacy… .

- Lastly, once you have introduced each theme and explained it, then present evidence from your readings to demonstrate the parameters of the knowledge on the theme, including areas of agreement and disagreement among researchers. Using the evidence, explain what the evidence for the theme means to your topic and any of your own relational or critical commentary.

Another way to think about structuring a literature review is a funnel model. A funnel model goes from broad topic, to sub-topics, to link to the study being undertaken. You can think of a literature review as a broad argument using mini-arguments. To use the funnel model, list your topic and the related subtopics, then design questions to answer with the literature. For example if our topic was discussion-based online learning, we might ask the following questions before reading the literature:

- Why is discussion important in learning?

- How does discussion support the development of social, cognitive, and teacher presence in an online course?

- What does research say about the use of traditional discussion boards ?

- What does the research say about asynchronous, video-based discussion ?

- How have other researchers compared written and video responses?

- How does this literature review link to my study?

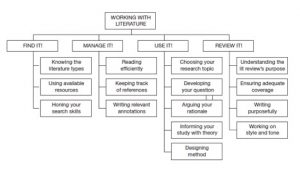

O’Leary (2004) provides an interesting representation and model of the purpose for the literature review in the research process, in Figure 3.1. We will leave this for you to think about before moving on to Chapter 4.

- We will talk about this aspect of literature reviews further in Chapters 6 and 7. ↵

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How To Structure Your Literature Review

3 options to help structure your chapter.

By: Amy Rommelspacher (PhD) | Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | November 2020 (Updated May 2023)

Writing the literature review chapter can seem pretty daunting when you’re piecing together your dissertation or thesis. As we’ve discussed before , a good literature review needs to achieve a few very important objectives – it should:

- Demonstrate your knowledge of the research topic

- Identify the gaps in the literature and show how your research links to these

- Provide the foundation for your conceptual framework (if you have one)

- Inform your own methodology and research design

To achieve this, your literature review needs a well-thought-out structure . Get the structure of your literature review chapter wrong and you’ll struggle to achieve these objectives. Don’t worry though – in this post, we’ll look at how to structure your literature review for maximum impact (and marks!).

But wait – is this the right time?

Deciding on the structure of your literature review should come towards the end of the literature review process – after you have collected and digested the literature, but before you start writing the chapter.

In other words, you need to first develop a rich understanding of the literature before you even attempt to map out a structure. There’s no use trying to develop a structure before you’ve fully wrapped your head around the existing research.

Equally importantly, you need to have a structure in place before you start writing , or your literature review will most likely end up a rambling, disjointed mess.

Importantly, don’t feel that once you’ve defined a structure you can’t iterate on it. It’s perfectly natural to adjust as you engage in the writing process. As we’ve discussed before , writing is a way of developing your thinking, so it’s quite common for your thinking to change – and therefore, for your chapter structure to change – as you write.

Need a helping hand?

Like any other chapter in your thesis or dissertation, your literature review needs to have a clear, logical structure. At a minimum, it should have three essential components – an introduction , a body and a conclusion .

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

1: The Introduction Section

Just like any good introduction, the introduction section of your literature review should introduce the purpose and layout (organisation) of the chapter. In other words, your introduction needs to give the reader a taste of what’s to come, and how you’re going to lay that out. Essentially, you should provide the reader with a high-level roadmap of your chapter to give them a taste of the journey that lies ahead.

Here’s an example of the layout visualised in a literature review introduction:

Your introduction should also outline your topic (including any tricky terminology or jargon) and provide an explanation of the scope of your literature review – in other words, what you will and won’t be covering (the delimitations ). This helps ringfence your review and achieve a clear focus . The clearer and narrower your focus, the deeper you can dive into the topic (which is typically where the magic lies).

Depending on the nature of your project, you could also present your stance or point of view at this stage. In other words, after grappling with the literature you’ll have an opinion about what the trends and concerns are in the field as well as what’s lacking. The introduction section can then present these ideas so that it is clear to examiners that you’re aware of how your research connects with existing knowledge .

2: The Body Section

The body of your literature review is the centre of your work. This is where you’ll present, analyse, evaluate and synthesise the existing research. In other words, this is where you’re going to earn (or lose) the most marks. Therefore, it’s important to carefully think about how you will organise your discussion to present it in a clear way.

The body of your literature review should do just as the description of this chapter suggests. It should “review” the literature – in other words, identify, analyse, and synthesise it. So, when thinking about structuring your literature review, you need to think about which structural approach will provide the best “review” for your specific type of research and objectives (we’ll get to this shortly).

There are (broadly speaking) three options for organising your literature review.

Option 1: Chronological (according to date)

Organising the literature chronologically is one of the simplest ways to structure your literature review. You start with what was published first and work your way through the literature until you reach the work published most recently. Pretty straightforward.

The benefit of this option is that it makes it easy to discuss the developments and debates in the field as they emerged over time. Organising your literature chronologically also allows you to highlight how specific articles or pieces of work might have changed the course of the field – in other words, which research has had the most impact . Therefore, this approach is very useful when your research is aimed at understanding how the topic has unfolded over time and is often used by scholars in the field of history. That said, this approach can be utilised by anyone that wants to explore change over time .

For example , if a student of politics is investigating how the understanding of democracy has evolved over time, they could use the chronological approach to provide a narrative that demonstrates how this understanding has changed through the ages.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself to help you structure your literature review chronologically.

- What is the earliest literature published relating to this topic?

- How has the field changed over time? Why?

- What are the most recent discoveries/theories?

In some ways, chronology plays a part whichever way you decide to structure your literature review, because you will always, to a certain extent, be analysing how the literature has developed. However, with the chronological approach, the emphasis is very firmly on how the discussion has evolved over time , as opposed to how all the literature links together (which we’ll discuss next ).

Option 2: Thematic (grouped by theme)

The thematic approach to structuring a literature review means organising your literature by theme or category – for example, by independent variables (i.e. factors that have an impact on a specific outcome).

As you’ve been collecting and synthesising literature , you’ll likely have started seeing some themes or patterns emerging. You can then use these themes or patterns as a structure for your body discussion. The thematic approach is the most common approach and is useful for structuring literature reviews in most fields.

For example, if you were researching which factors contributed towards people trusting an organisation, you might find themes such as consumers’ perceptions of an organisation’s competence, benevolence and integrity. Structuring your literature review thematically would mean structuring your literature review’s body section to discuss each of these themes, one section at a time.

Here are some questions to ask yourself when structuring your literature review by themes:

- Are there any patterns that have come to light in the literature?

- What are the central themes and categories used by the researchers?

- Do I have enough evidence of these themes?

PS – you can see an example of a thematically structured literature review in our literature review sample walkthrough video here.

Option 3: Methodological

The methodological option is a way of structuring your literature review by the research methodologies used . In other words, organising your discussion based on the angle from which each piece of research was approached – for example, qualitative , quantitative or mixed methodologies.

Structuring your literature review by methodology can be useful if you are drawing research from a variety of disciplines and are critiquing different methodologies. The point of this approach is to question how existing research has been conducted, as opposed to what the conclusions and/or findings the research were.

For example, a sociologist might centre their research around critiquing specific fieldwork practices. Their literature review will then be a summary of the fieldwork methodologies used by different studies.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself when structuring your literature review according to methodology:

- Which methodologies have been utilised in this field?

- Which methodology is the most popular (and why)?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the various methodologies?

- How can the existing methodologies inform my own methodology?

3: The Conclusion Section

Once you’ve completed the body section of your literature review using one of the structural approaches we discussed above, you’ll need to “wrap up” your literature review and pull all the pieces together to set the direction for the rest of your dissertation or thesis.

The conclusion is where you’ll present the key findings of your literature review. In this section, you should emphasise the research that is especially important to your research questions and highlight the gaps that exist in the literature. Based on this, you need to make it clear what you will add to the literature – in other words, justify your own research by showing how it will help fill one or more of the gaps you just identified.

Last but not least, if it’s your intention to develop a conceptual framework for your dissertation or thesis, the conclusion section is a good place to present this.

Example: Thematically Structured Review

In the video below, we unpack a literature review chapter so that you can see an example of a thematically structure review in practice.

Let’s Recap

In this article, we’ve discussed how to structure your literature review for maximum impact. Here’s a quick recap of what you need to keep in mind when deciding on your literature review structure:

- Just like other chapters, your literature review needs a clear introduction , body and conclusion .

- The introduction section should provide an overview of what you will discuss in your literature review.

- The body section of your literature review can be organised by chronology , theme or methodology . The right structural approach depends on what you’re trying to achieve with your research.

- The conclusion section should draw together the key findings of your literature review and link them to your research questions.

If you’re ready to get started, be sure to download our free literature review template to fast-track your chapter outline.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

27 Comments

Great work. This is exactly what I was looking for and helps a lot together with your previous post on literature review. One last thing is missing: a link to a great literature chapter of an journal article (maybe with comments of the different sections in this review chapter). Do you know any great literature review chapters?

I agree with you Marin… A great piece

I agree with Marin. This would be quite helpful if you annotate a nicely structured literature from previously published research articles.

Awesome article for my research.

I thank you immensely for this wonderful guide

It is indeed thought and supportive work for the futurist researcher and students

Very educative and good time to get guide. Thank you

Great work, very insightful. Thank you.

Thanks for this wonderful presentation. My question is that do I put all the variables into a single conceptual framework or each hypothesis will have it own conceptual framework?

Thank you very much, very helpful

This is very educative and precise . Thank you very much for dropping this kind of write up .

Pheeww, so damn helpful, thank you for this informative piece.

I’m doing a research project topic ; stool analysis for parasitic worm (enteric) worm, how do I structure it, thanks.

comprehensive explanation. Help us by pasting the URL of some good “literature review” for better understanding.

great piece. thanks for the awesome explanation. it is really worth sharing. I have a little question, if anyone can help me out, which of the options in the body of literature can be best fit if you are writing an architectural thesis that deals with design?

I am doing a research on nanofluids how can l structure it?

Beautifully clear.nThank you!

Lucid! Thankyou!

Brilliant work, well understood, many thanks

I like how this was so clear with simple language 😊😊 thank you so much 😊 for these information 😊

Insightful. I was struggling to come up with a sensible literature review but this has been really helpful. Thank you!

You have given thought-provoking information about the review of the literature.

Thank you. It has made my own research better and to impart your work to students I teach

I learnt a lot from this teaching. It’s a great piece.

I am doing research on EFL teacher motivation for his/her job. How Can I structure it? Is there any detailed template, additional to this?

You are so cool! I do not think I’ve read through something like this before. So nice to find somebody with some genuine thoughts on this issue. Seriously.. thank you for starting this up. This site is one thing that is required on the internet, someone with a little originality!

I’m asked to do conceptual, theoretical and empirical literature, and i just don’t know how to structure it

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Literature reviews

- Book a session

What is a literature review?

Finding your sources, structuring your review, critical writing, literature reviews, critiques and annotated bibliographies.

- Science and Health-based reviews This link opens in a new window

- Quick resources (5-10 mins)

- e-learning and books (30 mins+)

- SkillsCheck This link opens in a new window

- ⬅ Back to Skills Centre This link opens in a new window

Looking for sessions and tutorials on this topic? Find out more about our session types and how to register to book for sessions. You can view our full and up-to-date availability in UniHub Appointments and Events .

Not sure where to start developing your academic skills? Take the SkillsCheck for personalised recommendations on how to build your academic writing and study skills alongside your course.

Literature reviews take on many forms at university: you could be asked to write a literature review as a stand-alone document or as part of a dissertation or thesis. You may also be asked to write an annotated bibliography or a critical review - both of these assignments are closely related to literature reviews, and follow many of the same conventions.

A literature review is an extended piece of writing that should collate, link and evaluate key sources related to a chosen topic or research question. Rather than simply summarising the existing research on your chosen topic, you should aim to show which papers can be clustered around a similar theme or topic - they may have a shared methodology, or have been carried out in the same context. You will be looking for strengths and weaknesses in the research, questioning the relevance and significance of the results in relation to your topic, and looking for any gaps or under researched areas. Your writing should make these thoughts and evaluations clear to the reader, so that they have a good understanding and overview of the body of research you have chosen to investigate.

Here is a short video that explains a literature review from the perspective of the reader:

Salter, J. [Dr. Jodie Salter]. (2016, March 14). Writing the Literature Review: A Banquet Hall Analogy [Video file]. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QE_Us8UjS6

Using Library Search

The more you read around your subject, the more familiar you will become with the current literature, and you will start to build a map of the sources you already have, and the information you are missing. A clear search strategy can help fill these gaps in your knowledge, and your themes or topics of interest can be used as key search terms when looking for further resources.

Top tips for searching the Library Gateway

- Use Boolean terms to help the search engine recognise which words should be treated as a phrase. For example, if you search “costume design” , the search engine will know to treat “costume design” as a phrase, not two separate words.

- You can then add AND and OR to add in additional terms and synonyms. For example, “costume design” AND “film” will only find articles or sources that include both of these terms together, helping you to narrow your search. To go wider, think about adding in synonyms using the OR function: “costume design” AND “film” or “cinema” or “movies”.

- You can also use an asterisk (*) to search for a word stem to help widen your search. For example, if you search teach*, this will find articles that include the word teach, teacher, teachers, teaching and so on.

- Decide at the start on what your inclusion and exclusion criteria will be. These might include limits on: - Date of publication - Language - Type/group of participants - Peer-reviewed journals - Keywords and synonyms - Type of study, ie. systematic review, case study etc.

Search strategies

Explore the following resources for more information on search strategy models:

- PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) - Used primarily in Health Sciences but offers a clear step-by-step approach to literature searching that could be adapted for use in other subjects.

- SPIDER - Developed from the PICK method, SPIDER searching is used mainly in qualitative research to identify a phenomenon or behaviour, rather than a specific intervention (more quantitative).

Finding the gap

You might have heard about finding the gap in your literature review - but what does this mean?

Looking for the gap in the literature means finding an aspect of your topic that hasn't been fully explored by researchers. This might be because you are researching a new technique or technology, or that your method or approach hasn't been used before in your field of study. You don't always need to find a gap, but it is a good way of demonstrating your literature searching skills and ability to compare a wide range of different sources. If you are able to find one, introduce the gap towards the end of the literature review, so that the reader can trace your path through the evidence first.

Literature review structure: A three-tier model

Imagine you are explaining your dissertation topic to a friend for the first time. Even for someone on the same degree course, they would need some context on the topic before you introduced more detail and complex examples.

A literature review follows the same ‘funnel’ narrative , moving from general themes to more specific detail:

- Appraisal grid A template for taking notes from reading that enables you to find clear links and similarities for discussion in your literature review.

- PEP tables A template for organising notes from your reading by themes, theories and perspectives.

Paragraph structure

Each paragraph of your literature review should bring together or synthesise two or more pieces of reading (these could be articles, book chapters, reports, videos, policy documents etc.)

Synthesis is the term we use in academic writing to describe the process of creating an opinion or argument based on a trend you find in the literature. If you are able to synthesis evidence, you are not only creating a robust argument (by avoiding relying too heavily on just one piece of writing) but you are also showing that you are a critical writer that can make conclusions based on a diverse range of evidence. Bingo!

As in other forms of academic writing, the paragraphs in your literature review should have four key sections:

Compare the following paragraphs against this four-part structure - which version is more critical?

Although both paragraphs use the TIED structure, we can see that the discussion in paragraph B is much more developed, and gives a specific suggestion about how future research could be conducted. We can also see that the evidence in paragraph B is clearly linked together , and that the conclusions or critical features of the papers are explained to the reader. Although drawing on the same evidence, paragraph A summarises and describes the research papers , rather than giving an evaluation or clear comparison of the different sources.

Focusing on the discussion sections (in bold), we can see that paragraph B is more critical , as it answers a key questions to keep in mind when writing critically: 'so what?' What conclusion or take home message do you want the reader to get from the evidence you have presented? ‘Therefore’, ‘Consequently’ and ‘As a result’ are all good terms to use here, as they prompt you to be clear and explicitly explain on interpretation of the source you have included.

Other types of literature review

Not all literature reviews form part of a dissertation. Use the tabs below for guidance on different assignment formats related to literature reviews:

- What are the emotional and behavioral impacts of therapy dogs for autistic children?

- How might aptitude be tested and measured in puppies selected for guide dog training?

- What are the key success factors for dogs as social media influencers on Instagram and Facebook?

Your initial reading will help you to identify trends or themes in the literature that might help to focus your search. You can then follow the standard structure for writing a literature review, using the funnel structure from this guide.

A critical review, or ‘critique’, involves breaking a journal article down into its key sections so that you can evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each part. Making notes on each of the following headings is a useful way to kickstart your analysis of any article:

- Research aim

- Research approach (ie. quantitative)

- Ethical issues

- Data collection method

- Data analysis method

- Generalisability/transferability

This list is not exhaustive and depending on your discipline, there may be other relevant categories to focus on in the article, such as theoretical models or implications for practice. The subheadings from the article will also provide an overview of the key sections to include in your review, and you may already have an idea from your wider reading of what sections often appear in articles in your field of study. Breaking down the article in this way allows you to focus your critique and evaluation, highlighting significant or relevant aspects of the article to the reader . Your assessment criteria will help you to identify which elements of the article to include in your critique: for example, if you needed to include a reflection on how the article links to your professional practice, it would make sense to include your thoughts on the articles key findings and transferability in your critique. For examples of sentence starters and academic language to use in your critical review, take a look at the following resources:

- Writing a critical review, UCL

- Academic Phrasebank, University of Manchester

An annotated bibliography combines a correctly formatted list of references (APA) with a short paragraph that gives:

- a short summary of the source, that picks out the key points of the article, such as context and setting, participants and conclusions;

- a brief evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of the article;

- a sentence or two on the relevance of the source to your question or topic – what does it contribute to your knowledge of the subject, and in what ways might its relevance be limited?

Sources are not discussed together in the same paragraph, but the document itself will have a key theme or topic that ties the different sources together – almost like a module reading list: Brym, R., Godbout, M., Hoffbauer, A., Menard, G. & Huiquan Zhang, T. (2014) Social media in the 2011 Egyptian uprising. The British Journal of Sociology , 65 : 266-271. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12080 This article conducts a comparative analysis of quantitative data on social media usage and political engagement during the 2011 Egyptian uprising, using new bit.ly and Gallup survey results. The study generates a large amount of data on the key differences in social media usage between active demonstrators and sympathetic onlookers. Most significantly, the study explores the key drivers of participating in social unrest, such as a lack of confidence in the government, and how these are facilitated by social media. However, by only gathering quantitative data, the study is limited in its ability to provide an insight into how protestors narrate and explain their involvement in the protests in their own words. Overall, this article offers significant evidence to support a study of the importance of social media in contemporary political movements, and is particularly useful as one of few studies to focus on events outside of Europe and North America. Be sure to check your assessment criteria for tips on how you should evaluate your sources: for example, you might be asked to include specific methodology types or to link your sources to professional practice.

Two key principles apply to every literature review, whether it is part of a dissertation or an individual assignment:

1. A literature review is more than just a list of sources. The articles and evidence you include must be linked together around shared themes and characteristics, or highlight significant disagreements and contrast. Map your reading using keywords or themes that occur in multiple articles - these can be used as subheadings in your draft literature review.

2. While it is important to show that you are familiar with research in your field, you also need to show that you can evaluate and offer interpretations of the evidence you present to the reader. Remember to keep answering the 'so what?' question as you write.

- << Previous: Book a session

- Next: Science and Health-based reviews >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 1:52 PM

- URL: https://libguides.shu.ac.uk/literaturereviews

Funnel Plot in a Systematic Review

Automate every stage of your literature review to produce evidence-based research faster and more accurately.

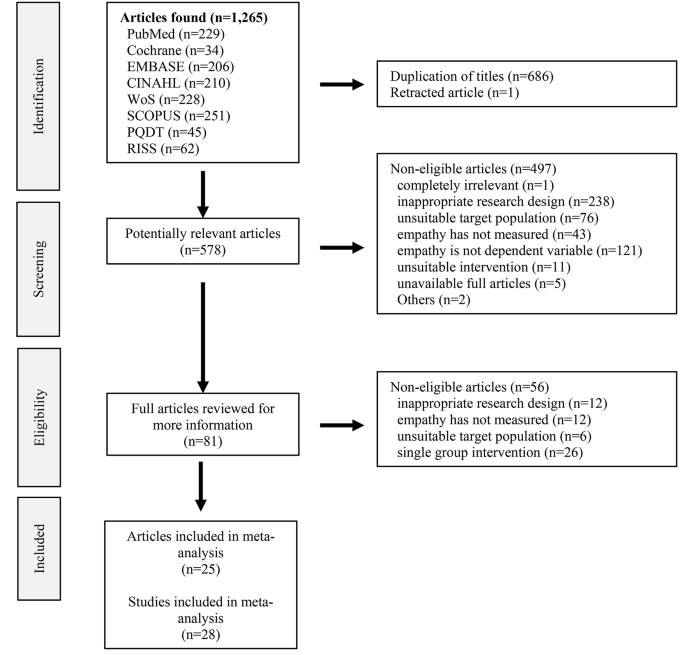

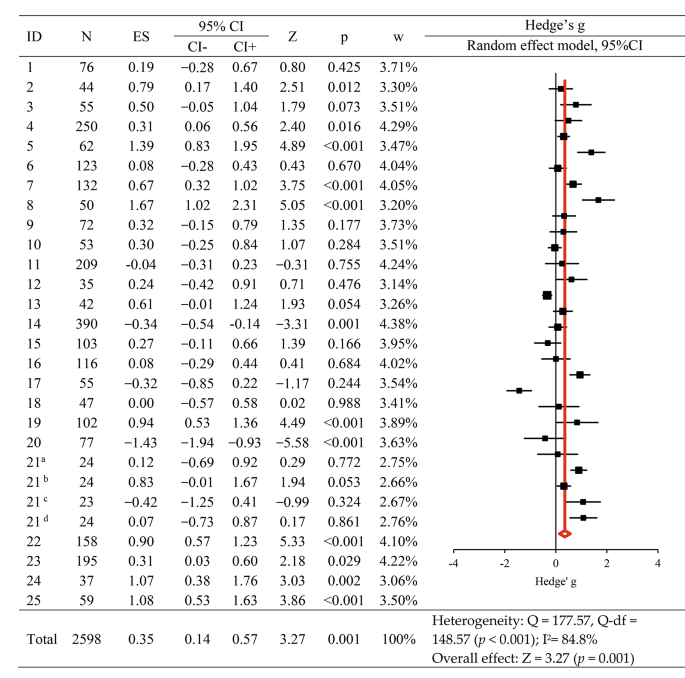

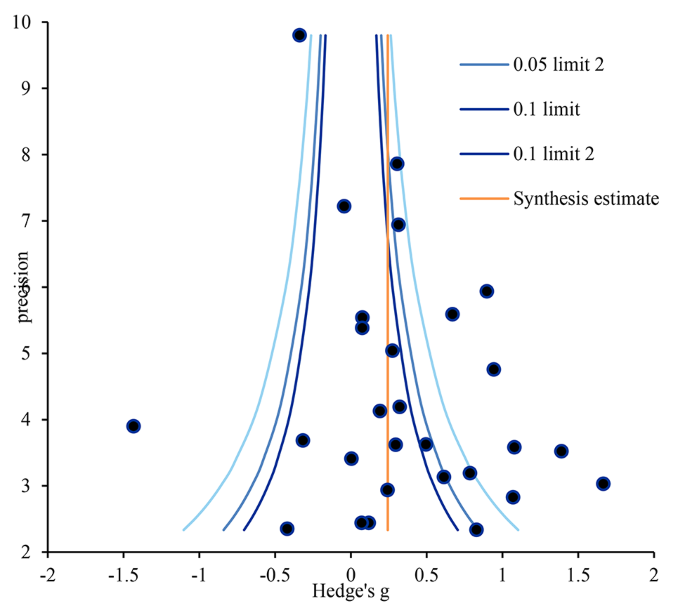

Systematic reviews are considered the gold standard in evidence-based research. These intensive “studies of studies” involve taking a systematic approach to collect, assess, and synthesize relevant literature on a specific subject, including peer-reviewed journal articles, gray literature, and other sources, to answer a well-defined research question. Systematic reviews, like other reviews, can also be prone to bias. The bias types that are most evaluated in systematic reviews are selection bias, reporting bias, detection bias, and attrition bias. But this can be prevented through several checks before you start the review. For example, ensuring that the eligibility criteria in a systematic review is well defined when designing the systematic review protocol of a systematic review article , will reduce the risk of selection bias during study selection. An effective tool called a funnel plot is designed to examine the existence of a publication bias, among studies included in a systematic review, or the tendency of authors to only publish studies with significant results, other reporting biases, and small study effects.

What Is A Funnel Plot In Systematic Reviews?

A funnel plot is a simple scatter plot of the treatment effects estimated from individual studies against a measure of the study size. The x-axis (horizontal axis) shows the results of the study, expressed as an odds or risk ratio or a percent difference, while the y-axis (vertical axis) displays the sample size or an index of precision. Other measures could also be plotted, such as reciprocals, or variances.

The scale of the y-axis is reversed; studies with higher precision are placed at the top while studies with lower precision are placed at the bottom. At the bottom where the low precision studies are placed, the points that represent the mean value of effect in each study are widely spread. The spread of these points begins to reduce, as you move upwards in the y-axis. This effect creates a plot that resembles a pyramid or an inverted funnel.

What Is The Purpose Of Funnel Plots?

A funnel plot is designed to check for the existence of publication bias, other reporting biases, and systematic heterogeneity in a systematic review. These are biases caused by the absence of information from unpublished sources (missing studies), or selective outcome reporting of a study’s result (missing outcomes). For example, the study authors may omit information that they may feel does not agree with their findings. In the absence of publication bias, the funnel plot, as its name suggests, should create a symmetrical funnel-shaped distribution. Deviations from this, like an asymmetrical plot, may indicate that there is a bias.

That said, it’s important to note that publication bias is only one of the issues examined by funnel plots. These plots can also assess small study effects, or the tendency for smaller studies to show larger treatment effects.

How to Interpret a Funnel Plot?

Funnel plots, typically, are symmetrical or asymmetrical. Here’s how to interpret them:

Symmetrical Funnel Plot

A “well-behaved” data set, one where the precision of the estimated intervention effect increases as the size of the study increases will yield a symmetric inverted funnel shape. This signifies the unlikeliness of bias.

Asymmetrical Funnel Plot

An asymmetrical funnel plot can indicate the presence of a bias, suggesting a relationship between treatment effect estimate and study precision. With these deviant shapes, you can assume the possibility of publication bias, small-study effects, or study heterogeneity. Asymmetry can also be caused by the use of an inappropriate effect measure. Whatever the cause, an asymmetric funnel plot leads to doubts about the systematic review. In this case, an investigation must be done to get to the bottom of the possible cause and correct the mistake.

Systematic reviews are one of the most rigorous research processes. But they’re not without risks as they can be prone to biases. Researchers can use tools to prevent these challenges—a funnel plot is one way to do it as it’s designed to check for publication bias, other reporting biases, and small study effects. Another great way to ensure that your systematic review is accurate, objective, and comprehensive is to use a literature review software like DistillerSR, which helps you automate each stage of your review to securely produce evidence-based research faster, and more precisely. This gives you the time and energy to focus on evaluating other information to ensure that your protocol is free from any biases.

3 Reasons to Connect

- Research Guides

Writing Literature Reviews

- Literature Review Overview

- Organizing Your Lit Review

- Tips for Writing Your Lit Review

Need Assistance?

Find your librarian, schedule a research appointment, today's hours : , what is a literature review.

A literature review ought to be a clear, concise synthesis of relevant information. A literature review should introduce the study it precedes and show how that study fits into topically related studies that already exist. Structurally, a literature review ought to be something like a funnel: start by addressing the topic broadly and gradually narrow as the review progresses.

from Literature Reviews by CU Writing Center

Why review the literature?

Reference to prior literature is a defining feature of academic and research writing. Why review the literature?

- To help you understand a research topic

- To establish the importance of a topic

- To help develop your own ideas

- To make sure you are not simply replicating research that others have already successfully completed

- To demonstrate knowledge and show how your current work is situated within, builds on, or departs from earlier publications

from Literature Review Basics from University of La Verne

Tips & Tricks

Before writing your own literature review, take a look at these resources which share helpful tips and tricks:

Lectures & Slides

- Literature Reviews | CU Writing Center

- Writing a Literature Review | CU Writing Center

- Revising a Literature Review | CU Writing Center

- Literature Reviews: How to Find and Do Them

- Literature Reviews: An Overview

How-To Guides

- Literature Reviews | Purdue OWL

- Literature Reviews | University of North Carolina

- Learn How to Write a Review of Literature | University of Wisconsin

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide | University of Connecticut

- Literature Reviews | Florida A & M

- Conduct a Literature Review | SUNY

- Literature Review Basics | University of LaVerne

Sample Literature Reviews

- Sample Literature Reviews | University of West Florida

- Sample APA Papers: Literature Review | Purdue OWL

- Next: Organizing Your Lit Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2020 3:12 PM

- URL: https://libguides.cedarville.edu/c.php?g=969394

Writers' Center

Eastern Washington University

Writing the Literature Review

The literature review, questions your literature review might address, tips for writing a literature review, tips for organizing your sources.

[ Back to resource home ]

[email protected] 509.359.2779

Cheney Campus JFK Library Learning Commons

Stay Connected!

inside.ewu.edu/writerscenter Instagram Facebook

- Occupational Therapy Sample

- Social Work Sample

- POOR Literature Review Sample This is how NOT to write a literature review.

What is a literature review?

When we hear the word "literature," we often think of great classic novels or poetry, but in this case "literature" refers to the body of work you consulted in order to make a conclusive recommendation about an issue. In other words, a literature review is a synthesis (more on synthesis below) of many articles and other published materials on a certain research topic. Depending on the field, the literature review might be a stand-alone piece or part of a larger research article.

Why write one?

By writing a literature review, you are entering into an academic conversation about an issue. You need to show that you understand what research has already been done in your field and how your own research fits into it.

1. What do we already know in the immediate area concerned?

2. What are the characteristics/traits of the key concepts or the main factors or variables?

3. What are the relationships between these key concepts, factors or variables?

4. What are the existing theories?

5. Where are the inconsistencies or other shortcomings in our knowledge and understanding?

6. What views need to be (further) tested?

7. What evidence is lacking, inconclusive, contradictory or too limited?

8. What research designs or methods seem unsatisfactory?

9. How does this research provide context for my own work?

Synthesis involves but goes beyond summary. Rather than simply summarizing sources (as an annotated bibliography does), synthesis also does the following:

- shows the relationships between sources (how are they similar or different, how do they build off one another, where are the gaps)

- shows how sources relate to your own work (provides the context for your research)

- sometimes evaluates the methods or conclusions of sources

Synthesis literally means to bring together, to combine separate elements to make a cohesive whole. Here are some analogies to help with the concept of synthesis:

Credit: https://www.flickr.com/photos/pcapemax2007/8711542470

Architecture: Each main idea is an element of architecture: a shape, a material, a color. All of the elements come together to form a coherent look (synthesis).

Remember your purpose.

Keeping your own research question or goals in mind as you read will help you decide which sources to include in your review and which ones to briefly mention or leave out entirely.

Know and organize your sources.

Use a free citation manager to keep track of and categorize articles in library databases. Use different colors to highlight different "threads" or "notes" (main ideas) of your sources. Take lots of notes.

Look for threads patiently.

Be patient with yourself during this process. It will take time to read, reread, annotate, and start to see connections beween sources.

Use transition phrases that indicate synthesis.

Language is your key to showing connections between ideas on paper. Consider using transition phrases like the following, or borrow phrasing that you like from other articles. (It's not plagiarism to use common phrases.)

Organize your review like a funnel.

Start by addressing the larger context of the issue at hand. Gradually work to the more specific aspects you will be looking at. Finally, narrow into your own project and research.

Read plenty of sample literature reviews in your field.

Literature reviews vary in purpose and format from field to field, so use published literature review articles in your discipline as models. You can find a few annotated samples on this page.

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 2:50 PM

- URL: https://research.ewu.edu/writers_c_lit_review

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Recommendations for...

Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials

- Related content

- Peer review

- Jonathan A C Sterne , professor 1 ,

- Alex J Sutton , professor 2 ,

- John P A Ioannidis , professor and director 3 ,

- Norma Terrin , associate professor 4 ,

- David R Jones , professor 2 ,

- Joseph Lau , professor 4 ,

- James Carpenter , reader 5 ,

- Gerta Rücker , research assistant 6 ,

- Roger M Harbord , research associate 1 ,

- Christopher H Schmid , professor 4 ,

- Jennifer Tetzlaff , research coordinator 7 ,

- Jonathan J Deeks , professor 8 ,

- Jaime Peters , research fellow 9 ,

- Petra Macaskill , associate professor 10 ,

- Guido Schwarzer , research assistant 6 ,

- Sue Duval , assistant professor 11 ,

- Douglas G Altman , professor 12 ,

- David Moher , senior scientist 7 ,

- Julian P T Higgins , senior statistician 13

- 1 School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2PS, UK

- 2 Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

- 3 Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

- 4 Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA

- 5 Medical Statistics Unit, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

- 6 Institute of Medical Biometry and Medical Informatics, University Medical Center Freiburg, Germany

- 7 Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- 8 School of Health and Population Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

- 9 Peninsula Medical School, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

- 10 School of Public Health, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 11 University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN, USA

- 12 Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

- 13 MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK

- Correspondence to: J A C Sterne jonathan.sterne{at}bristol.ac.uk

- Accepted 21 February 2011

Funnel plots, and tests for funnel plot asymmetry, have been widely used to examine bias in the results of meta-analyses. Funnel plot asymmetry should not be equated with publication bias, because it has a number of other possible causes. This article describes how to interpret funnel plot asymmetry, recommends appropriate tests, and explains the implications for choice of meta-analysis model

The 1997 paper describing the test for funnel plot asymmetry proposed by Egger et al 1 is one of the most cited articles in the history of BMJ . 1 Despite the recommendations contained in this and subsequent papers, 2 3 funnel plot asymmetry is often, wrongly, equated with publication or other reporting biases. The use and appropriate interpretation of funnel plots and tests for funnel plot asymmetry have been controversial because of questions about statistical validity, 4 disputes over appropriate interpretation, 3 5 6 and low power of the tests. 2

This article recommends how to examine and interpret funnel plot asymmetry (also known as small study effects 2 ) in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. The recommendations are based on a detailed MEDLINE review of literature published up to 2007 and discussions among methodologists, who extended and adapted guidance previously summarised in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 7

What is a funnel plot?

A funnel plot is a scatter plot of the effect estimates from individual studies against some measure of each study’s size or precision. The standard error of the effect estimate is often chosen as the measure of study size and plotted on the vertical axis 8 with a reversed scale that places the larger, most powerful studies towards the top. The effect estimates from smaller studies should scatter more widely at the bottom, with the spread narrowing among larger studies. 9 In the absence of bias and between study heterogeneity, the scatter will be due to sampling variation alone and the plot will resemble a symmetrical inverted funnel (fig 1 ⇓ ). A triangle centred on a fixed effect summary estimate and extending 1.96 standard errors either side will include about 95% of studies if no bias is present and the fixed effect assumption (that the true treatment effect is the same in each study) is valid. The appendix on bmj.com discusses choice of axis in funnel plots.

Fig 1 Example of symmetrical funnel plot. The outer dashed lines indicate the triangular region within which 95% of studies are expected to lie in the absence of both biases and heterogeneity (fixed effect summary log odds ratio±1.96×standard error of summary log odds ratio). The solid vertical line corresponds to no intervention effect

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Implications of heterogeneity, reporting bias, and chance

Heterogeneity, reporting bias, and chance may all lead to asymmetry or other shapes in funnel plots (box). Funnel plot asymmetry may also be an artefact of the choice of statistics being plotted (see appendix). The presence of any shape in a funnel plot is contingent on the studies having a range of standard errors, since otherwise they would lie on a horizontal line.

Box 1: Possible sources of asymmetry in funnel plots (adapted from Egger et al 1 )

Reporting biases.

Publication bias:

Delayed publication (also known as time lag or pipeline) bias

Location biases (eg, language bias, citation bias, multiple publication bias)

Selective outcome reporting

Selective analysis reporting

Poor methodological quality leading to spuriously inflated effects in smaller studies

Poor methodological design

Inadequate analysis

True heterogeneity

Size of effect differs according to study size (eg, because of differences in the intensity of interventions or in underlying risk between studies of different sizes)

Artefactual

In some circumstances, sampling variation can lead to an association between the intervention effect and its standard error

Asymmetry may occur by chance, which motivates the use of asymmetry tests

Heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity refers to differences between study results beyond those attributable to chance. It may arise because of clinical differences between studies (for example, setting, types of participants, or implementation of the intervention) or methodological differences (such as extent of control over bias). A random effects model is often used to incorporate heterogeneity in meta-analyses. If the heterogeneity fits with the assumptions of this model, a funnel plot will be symmetrical but with additional horizontal scatter. If heterogeneity is large it may overwhelm the sampling error, so that the plot appears cylindrical.

Heterogeneity will lead to funnel plot asymmetry if it induces a correlation between study sizes and intervention effects. 5 For example, substantial benefit may be seen only in high risk patients, and these may be preferentially included in early, small studies. 10 Or the intervention may have been implemented less thoroughly in larger studies, resulting in smaller effect estimates compared with smaller studies. 11

Figure 2 ⇓ shows funnel plot asymmetry arising from heterogeneity that is due entirely to there being three distinct subgroups of studies, each with a different intervention effect. 12 The separate funnels for each subgroup are symmetrical. Unfortunately, in practice, important sources of heterogeneity are often unknown.

Fig 2 Illustration of funnel plot asymmetry due to heterogeneity, in the form of three distinct subgroups of studies. Funnel plot including all studies (top left) shows clear asymmetry (P<0.001 from Egger test for funnel plot asymmetry). P values for each subgroup are all >0.49.

Differences in methodological quality may also cause heterogeneity and lead to funnel plot asymmetry. Smaller studies tend to be conducted and analysed with less methodological rigour than larger studies, 13 and trials of lower quality also tend to show larger intervention effects. 14 15

Reporting bias

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. Statistically significant “positive” results are more likely to be published, published rapidly, published in English, published more than once, published in high impact journals, and cited by others. 16 17 18 19 Data that would lead to negative results may be filtered, manipulated, or presented in such a way that they become positive. 14 20

Reporting biases can have three types of consequence for a meta-analysis:

A systematic review may fail to locate an eligible study because all information about it is suppressed or hard to find (publication bias)

A located study may not provide usable data for the outcome of interest because the study authors did not consider the result sufficiently interesting (selective outcome reporting)

A located study may provide biased results for some outcome—for example, by presenting the result with the smallest P value or largest effect estimate after trying several analysis methods (selective analysis reporting).

These biases may cause funnel plot asymmetry if statistically significant results suggesting a beneficial effect are more likely to be published than non-significant results. Such asymmetry may be exaggerated if there is a further tendency for smaller studies to be more prone to selective suppression of results than larger studies. This is often assumed to be the case for randomised trials. For instance, it is probably more difficult to make a large study disappear without trace, while a small study can easily be lost in a file drawer. 21 The same may apply to specific outcomes—for example, it is difficult not to report on mortality or myocardial infarction if these are outcomes of a large study.

Smaller studies have more sampling error in their effect estimates. Thus even though the risk of a false positive significant finding is the same, multiple analyses are more likely to yield a large effect estimate that may seem worth publishing. However, biases may not act this way in real life; funnel plots could be symmetrical even in the presence of publication bias or selective outcome reporting 19 22 —for example, if the published findings point to effects in different directions but unreported results indicate neither direction. Alternatively, bias may have affected few studies and therefore not cause glaring asymmetry.

The role of chance is critical for interpretation of funnel plots because most meta-analyses of randomised trials in healthcare contain few studies. 2 Investigations of relations across studies in a meta-analysis are seriously prone to false positive findings when there is a small number of studies and heterogeneity across studies, 23 and this may affect funnel plot symmetry.

Interpreting funnel plot asymmetry

Authors of systematic reviews should distinguish between possible reasons for funnel plot asymmetry (box 1). Knowledge of the intervention, and the circumstances in which it was implemented in different studies, can help identify causes of asymmetry in funnel plots, which should also be interpreted in the context of susceptibility to biases of research in the field of interest. Potential conflicts of interest, whether outcomes and analyses have been standardised, and extent of trial registration may need to be considered. For example, studies of antidepressants generate substantial conflicts of interest because the drugs generate vast sales revenues. Furthermore, there are hundreds of outcome scales, analyses can be very flexible, and trial registration was uncommon until recently. 24 Conversely, in a prospective meta-analysis where all data are included and all analyses fully standardised and conducted according to a predetermined protocol, publication or reporting biases cannot exist. Reporting bias is therefore more likely to be a cause of an asymmetric plot in the first situation than in the second.

Terrin et al found that researchers were poor at identifying publication bias from funnel plots. 5 Including contour lines corresponding to perceived milestones of statistical significance (P=0.01, 0.05, 0.1, etc) may aid visual interpretation. 25 If studies seem to be missing in areas of non-significance (fig 3 ⇓ , top) then asymmetry may be due to reporting bias, although other explanations should still be considered. If the supposed missing studies are in areas of higher significance or in a direction likely to be considered desirable to their authors (fig 3 ⇓ , bottom), asymmetry is probably due to factors other than reporting bias.

Fig 3 Contour enhanced funnel plots. In the top diagram there is a suggestion of missing studies in the middle and right of the plot, broadly in the white area of non-significance, making publication bias plausible. In the bottom diagram there is a suggestion of missing studies on the bottom left hand side of the plot. Since most of this area contains regions of high significance, publication bias is unlikely to be the underlying cause of asymmetry

Statistical tests for funnel plot asymmetry

A test for funnel plot asymmetry (sometimes referred to as a test for small study effects) examines whether the association between estimated intervention effects and a measure of study size is greater than might be expected to occur by chance. These tests typically have low power, so even when a test does not provide evidence of asymmetry, bias cannot be excluded. For outcomes measured on a continuous scale a test based on a weighted linear regression of the effect estimates on their standard errors is straightforward. 1 When outcomes are dichotomous and intervention effects are expressed as odds ratios, this corresponds to an inverse variance weighted linear regression of the log odds ratio on its standard error. 2 Unfortunately, there are statistical problems because the standard error of the log odds ratio is mathematically linked to the size of the odds ratio, even in the absence of small study effects. 2 4 Many authors have therefore proposed alternative tests (see appendix on bmj.com). 4 26 27 28

Because it is impossible to know the precise mechanism(s) leading to funnel plot asymmetry, simulation studies (in which tests are evaluated on large numbers of computer generated datasets) are required to evaluate test characteristics. Most have examined a range of assumptions about the extent of reporting bias by selectively removing studies from simulated datasets. 26 27 28 After reviewing the results of these studies, and based on theoretical considerations, we formulated recommendations on testing for funnel plot asymmetry (box 2). The appendix describes the proposed tests, explains the reasons that some were not recommended, and discusses funnel plots for intervention effects measured as risk ratios, risk differences, and standardised mean differences. Our recommendations imply that tests for funnel plot asymmetry should be used in only a minority of meta-analyses. 29

Box 2: Recommendations on testing for funnel plot asymmetry

All types of outcome.

As a rule of thumb, tests for funnel plot asymmetry should not be used when there are fewer than 10 studies in the meta-analysis because test power is usually too low to distinguish chance from real asymmetry. (The lower the power of a test, the higher the proportion of “statistically significant” results in which there is in reality no association between study size and intervention effects). In some situations—for example, when there is substantial heterogeneity—the minimum number of studies may be substantially more than 10

Test results should be interpreted in the context of visual inspection of funnel plots— for example, are there studies with markedly different intervention effect estimates or studies that are highly influential in the asymmetry test? Even if an asymmetry test is statistically significant, publication bias can probably be excluded if small studies tend to lead to lower estimates of benefit than larger studies or if there are no studies with significant results

When there is evidence of funnel plot asymmetry, publication bias is only one possible explanation (see box 1)

As far as possible, testing strategy should be specified in advance: choice of test may depend on the degree of heterogeneity observed. Applying and reporting many tests is discouraged: if more than one test is used, all test results should be reported

Tests for funnel plot asymmetry should not be used if the standard errors of the intervention effect estimates are all similar (the studies are of similar sizes)

Continuous outcomes with intervention effects measured as mean differences

The test proposed by Egger et al may be used to test for funnel plot asymmetry. 1 There is no reason to prefer more recently proposed tests, although their relative advantages and disadvantages have not been formally examined. General considerations suggest that the power will be greater than for dichotomous outcomes but that use of the test with substantially fewer than 10 studies would be unwise

Dichotomous outcomes with intervention effects measured as odds ratios

The tests proposed by Harbord et al 26 and Peters et al 27 avoid the mathematical association between the log odds ratio and its standard error when there is a substantial intervention effect while retaining power compared with alternative tests. However, false positive results may still occur if there is substantial between study heterogeneity

If there is substantial between study heterogeneity (the estimated heterogeneity variance of log odds ratios, τ 2 , is >0.1) only the arcsine test including random effects, proposed by Rücker et al, has been shown to work reasonably well. 28 However, it is slightly conservative in the absence of heterogeneity and its interpretation is less familiar than for other tests because it is based on an arcsine transformation.

When τ 2 is <0.1, one of the tests proposed by Harbord et al, 26 Peters et al, 27 or Rücker et al 28 can be used. Test performance generally deteriorates as τ 2 increases.

Funnel plots and meta-analysis models

Fixed and random effects models.

Funnel plots can help guide choice of meta-analysis method. Random effects meta-analyses weight studies relatively more equally than fixed effect analyses by incorporating the between study variance into the denominator of each weight. If effect estimates are related to standard errors (funnel plot asymmetry), the random effects estimate will be pulled more towards findings from smaller studies than the fixed effect estimate will be. Random effects models can thus have undesirable consequences and are not always conservative. 30

The trials of intravenous magnesium after myocardial infarction provide an extreme example of the differences between fixed and random effects analyses that can arise in the presence of funnel plot asymmetry. 31 Beneficial effects on mortality, found in a meta-analysis of small studies, 32 were subsequently contradicted when the very large ISIS-4 study found no evidence of benefit. 33 A contour enhanced funnel plot (fig 4 ⇓ ) gives a clear visual impression of asymmetry, which is confirmed by small P values from the Harbord and Peters tests (P<0.001 and P=0.002 respectively).

Fig 4 Contour enhanced funnel plot for trials of the effect of intravenous magnesium on mortality after myocardial infarction

Figure 5 ⇓ shows that in a fixed effect analysis ISIS-4 receives 90% of the weight, and there is no evidence of a beneficial effect. However, there is clear evidence of between study heterogeneity (P<0.001, I 2 =68%), and in a random effects analysis the small studies dominate so that intervention appears beneficial. To interpret the accumulated evidence, it is necessary to make a judgment about the validity or relevance of the combined evidence from the smaller studies compared with that from ISIS-4. The contour enhanced funnel plot suggests that publication bias does not completely explain the asymmetry, since many of the beneficial effects reported from smaller studies were not significant. Plausible explanations for these results are that methodological flaws in the smaller studies, or changes in the standard of care (widespread adoption of treatments such as aspirin, heparin, and thrombolysis), led to apparent beneficial effects of magnesium. This belief was reinforced by the subsequent publication of the MAGIC trial, in which magnesium added to these treatments which also found no evidence of benefit on mortality (odds ratio 1.0, 95% confidence interval 0.8 to 1.1). 34