Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Ask Yale Library

My Library Accounts

Find, Request, and Use

Help and Research Support

Visit and Study

Explore Collections

Political Science Subject Guide: Literature Reviews

- Political Science

- Books & Dissertations

- Articles & Databases

- Literature Reviews

- Senior Essay Resources

- Country Information

More Literature Review Writing Tips

- Thesis Whisperer- Bedraggled Daisy Lay advice on writing theses and dissertations. This article demonstrates in more detail one aspect of our discussion

Books on the Literature Review

What is a literature review?

"A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. [...] In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries."

(from "The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Writing It," http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review )

Strategies for conducting your own literature review

1. Use this guide as a starting point. Begin your search with the resources linked from the political science subject guide. These library catalogs and databases will help you identify what's been published on your topic.

2. What came first? Try bibliographic tracing. As you're finding sources, pay attention to what and whom these authors cite. Their footnotes and bibliographies will point you in the direction of additional scholarship on your topic.

3. What comes next? Look for reviews and citation reports. What did scholars think about that book when it was published in 2003? Has anyone cited that article since 1971? Reviews and citation analysis tools can help you determine if you've found the seminal works on your topic--so that you can be confident that you haven't missed anything important, and that you've kept up with the debates in your field. You'll find book reviews in JSTOR and other databases. Google Scholar has some citation metrics; you can use Web of Science ( Social Sciences Citation Index ) for more robust citation reports.

4. Stay current. Get familiar with the top journals in your field, and set up alerts for new articles. If you don't know where to begin, APSA and other scholarly associations often maintain lists of journals, broken out by subfield . In many databases (and in Google Scholar), you can also set up search alerts, which will notify you when additional items have been added that meet your search criteria.

5. Stay organized. A citation management tool--e.g., RefWorks, Endnote, Zotero, Mendeley--will help you store your citations, generate a bibliography, and cite your sources while you write. Some of these tools are also useful for file storage, if you'd like to keep PDFs of the articles you've found. To get started with citation management tools, check out this guide .

How to find existing literature reviews

1. Consult Annual Reviews. The Annual Review of Political Science consists of thorough literature review essays in all areas of political science, written by noted scholars. The library also subscribes to Annual Reviews in economics, law and social science, sociology, and many other disciplines.

2. Turn to handbooks, bibliographies, and other reference sources. Resources like Oxford Bibliographies Online and assorted handbooks ( Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics , Oxford Handbook of American Elections and Political Behavior , etc.) are great ways to get a substantive introduction to a topic, subject area, debate, or issue. Not exactly literature reviews, but they do provide significant reference to and commentary on the relevant literature--like a heavily footnoted encyclopedia for specialists in a discipline.

3. Search databases and Google Scholar. Use the recommended databases in the "Articles & Databases" tab of this guide and try a search that includes the phrase "literature review."

4. Search in journals for literature review articles. Once you've identified the important journals in your field as suggested in the section above, you can target these journals and search for review articles.

5. Find book reviews. These reviews can often contain useful contextual information about the concerns and debates of a field. Worldwide Political Science Abstracts is a good source for book reviews, as is JSTOR . To get to book reviews in JSTOR, select the advanced search option, use the title of the book as your search phrase, and narrow by item type: reviews. You can also narrow your search further by discipline.

6. Cast a wide net--don't forget dissertations. Dissertations and theses often include literature review sections. While these aren't necessarily authoritative, definitive literature reviews (you'll want to check in Annual Reviews for those), they can provide helpful suggestions for sources to consider.

- << Previous: News

- Next: Senior Essay Resources >>

- Last Updated: Oct 21, 2024 11:37 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/politicalscience

Site Navigation

P.O. BOX 208240 New Haven, CT 06250-8240 (203) 432-1775

Yale's Libraries

Bass Library

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Classics Library

Cushing/Whitney Medical Library

Divinity Library

East Asia Library

Gilmore Music Library

Haas Family Arts Library

Lewis Walpole Library

Lillian Goldman Law Library

Marx Science and Social Science Library

Sterling Memorial Library

Yale Center for British Art

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

@YALELIBRARY

Yale Library Instagram

Accessibility Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Giving Privacy and Data Use Contact Our Web Team

© 2022 Yale University Library • All Rights Reserved

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Rigorous Policy-Making Amid COVID-19 and Beyond: Literature Review and Critical Insights

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Received 2021 Oct 10; Accepted 2021 Nov 24; Collection date 2021 Dec.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

Policies shape society. Public health policies are of particular importance, as they often dictate matters in life and death. Accumulating evidence indicates that good-intentioned COVID-19 policies, such as shelter-in-place measures, can often result in unintended consequences among vulnerable populations such as nursing home residents and domestic violence victims. Thus, to shed light on the issue, this study aimed to identify policy-making processes that have the potential of developing policies that could induce optimal desirable outcomes with limited to no unintended consequences amid the pandemic and beyond. Methods: A literature review was conducted in PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus to answer the research question. To better structure the review and the subsequent analysis, theoretical frameworks such as the social ecological model were adopted to guide the process. Results: The findings suggested that: (1) people-centered; (2) artificial intelligence (AI)-powered; (3) data-driven, and (4) supervision-enhanced policy-making processes could help society develop policies that have the potential to yield desirable outcomes with limited unintended consequences. To leverage these strategies’ interconnectedness, the people-centered, AI-powered, data-driven, and supervision-enhanced (PADS) model of policy making was subsequently developed. Conclusions: The PADS model can develop policies that have the potential to induce optimal outcomes and limit or eliminate unintended consequences amid COVID-19 and beyond. Rather than serving as a definitive answer to problematic COVID-19 policy-making practices, the PADS model could be best understood as one of many promising frameworks that could bring the pandemic policy-making process more in line with the interests of societies at large; in other words, more cost-effectively, and consistently anti-COVID and pro-human.

Keywords: COVID-19, health policy, public health, PADS, people-centered

1. Background

As much as policies shape society, they create it as well [ 1 ]. The change can be either slow or fast—depending on the context, newly found commonalities, communities, cultures, if not new reckonings among the civilizations, can either occur incrementally or with lightning speed [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Take COVID-19 prevention policies, for instance. Ranging from loose measures to long-term mandates, COVID-19 policies have created communities (e.g., mask supporters, anti-vaxxers, conspiracy theorists, and citizen vigilantes) [ 5 , 6 , 7 ], cultures (e.g., the xenophobic culture, the civic culture) [ 8 , 9 , 10 ], and perhaps most importantly, new understandings of the shared vulnerabilities and strengthens of the civilization (e.g., the peril of extremely tiny viruses, the power of small vials of vaccines, and the promise of victory-minded humanity) [ 11 , 12 , 13 ].

Public policies can be understood as the “purposive course of action followed by an actor or a set of actors in dealing with a problem or matter of concern” [ 14 ], which are often “formal, legally-binding measures adopted by legislative and administrative units of government” [ 15 ]. Overall, public policies are arbitrary rules and regulations developed to create social goods [ 16 ]. Ranging from shelter-in-place measures to lockdown mandates, and masking rules to vaccine regulations, one common denominator of these policies is their ability to curb the spread of the pandemic, and in turn, COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. In an epidemiological modeling study across eight countries, researchers found that an additional delay of imposing lockdown measures amid COVID-19 outbreaks for one week could result in half a million deaths that could have been avoided [ 20 ]. In a similar vein, an early implementation of stringent public policies on physical distancing and an early lifting of these policies are the main reasons the state of California had successfully controlled the COVID-19 outbreak first [ 21 ], and only later became the first state in the U.S. that surpassed 500,000 confirmed cases and 10,000 deaths [ 22 , 23 ].

However, it is important to note that public policies could also result in unintended consequences. A growing body of research indicates that separating people from their familiar routines and social environments could have devastating effects on their physical and psychological health [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. Furthermore, evidence indicates that COVID-19 physical distancing measures could cause mental disorders including distress, anxiety, depression, and suicidal behaviors [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. This might be especially true among vulnerable populations—older adults, domestic violence victims, racial/sexual minorities, and other underserved communities were among those who have been shouldering the most pronounced adverse impacts across the pandemic [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ].

Take nursing home residents, for instance. A key characteristic of nursing home residents is that they have either lost or are losing their abilities to take care of themselves, a situation that is particularly pronounced among those who suffer from cognitive impairments such as dementia [ 31 ]. Amid COVID-19, many nursing home residents were found to have been left for days without access to care, food, or water, let alone basic medicines, and many of them died during the abandonment [ 34 ]. While nursing homes are often plagued with various issues [ 35 , 36 , 37 ], elder abuse and neglect have rarely been this glaring prior to the pandemic [ 38 , 39 ]. One way to address these unintended consequences is via addressing their root cause—rather than scrambling to construct piecemeal policies at the eleventh hour, rigorously and pre-emptively developing policies, such as via evidence-based policy-making processes, may hold the key [ 40 ].

Evidence-based policy making can be understood as the law-making process that is guided by and developed on the basis of evidence [ 41 ]. A rich body of evidence suggests that evidence-based policy making can provide considerable benefits to society at large [ 42 ]. However, it is important to note that evidence-based policy making is not without flaws [ 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ], many of which have either been highlighted or magnified amid the pandemic [ 47 , 48 ]. Conventional policy making often follows a range of one-directional steps, including agenda setting, policy formulation, policy adoption and application, and policy evaluation [ 49 ]. This means that in order for the resultant policies to be evidence-based, reflective of people’s needs, and have the potential to yield positive outcomes, the policy-making process is often thoroughly planned, detail-rich, time-consuming, and resource-dependent [ 50 ]—parameters that most of the pandemic-era policy-making might not be able to meet.

In other words, the unprecedented nature of the pandemic has effectively deprived policy makers of the time and planning needed to develop most conventional policies pre-emptively, let alone evidence-based ones that might be even more resource-demanding. Second, the fast-evolving characteristics of the pandemic led to the inevitability that, most, if not all, policies developed based on the conventional stage-oriented policy-making procedures would significantly lag reality. As seen amid the pandemic, “facts” and “truisms”, such as “evidence-based” predictions that claim that summer 2021 is when the pandemic would end, might sound naïve, if not juvenile, in light of the Delta-disturbed reality [ 51 ]. This means that policies that are developed on old evidence, even if it is one month old, may offer little to no utility to society at large. Third, due to a lack of clear understanding of and consensus on what could be classified as “evidence” [ 52 ], as seen amid COVID-19, oftentimes even anecdotal stories and personal opinions, if not gut feelings, have been enlisted as the “evidence” upon which policy makers alike based their pandemic policies [ 53 ].

These drawbacks, in turn, could significantly compromise public health policies’ abilities to produce much-needed positive effects on society with limited to no unintended consequences. In other words, the conventional evidence-based policy-making processes may not be able to develop policies amid COVID-19 that could:

yield desirable outcomes;

produce little to no unintended consequences in light of the unique challenges of the pandemic. However, there is a dearth of insights available in the literature that could address the above-mentioned issues. Thus, to bridge the research gap, this study aimed to identify policy-making processes that have the potential to develop policies that could induce optimal desirable outcomes with limited to no unintended consequences amid the pandemic and beyond.

A literature review was conducted in PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus to identify rigorous policy-making processes that could develop competent policies with the potential of producing desirable outcomes and curbing unintended consequences amid the unique challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, the research question raised in the study had three interconnected components: rigorous policy-making processes that could (1) produce desirable pandemic prevention outcomes, with (2) limited to no unintended consequences, in light of the (3) unique challenges of COVID-19. In this study, desirable pandemic prevention outcomes can be understood as reduced COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths. Whereas “adverse unintended consequences” and “unintended consequences” are used interchangeably, referring to negative policy outcomes that were different from expected results.

The search was developed based on two overarching concepts: COVID-19 and policy making. An example PubMed search term can be found in Table 1 . All records reviewed were published in English. To effectively address this three-pronged research aim, the review strategy was developed based on three themes:

Example PubMed search strings.

unique characteristics of COVID-19;

rigorous policy-making processes;

intended and unintended policy outcomes.

A set of eligibility criteria was adopted to screen the papers. Overall, articles were excluded if they:

did not focus on COVID-19;

did not center on the pandemic policy-making process;

did not provide insights into approaches that could either improve intended outcomes or avoid unintended consequences.

To ensure up-to-date insights were included in the analysis, validated news reports were also reviewed. Furthermore, Google Scholar alerts were set up so that relevant and most updated insights could be reviewed and analyzed to further shed light on the research question. The initial search was first conducted on 8 August 2021, with the subsequent one conducted on 15 October 2021, to include updated insights in the review.

3. Theoretical Underpinning

To better guide the review process and the subsequent analysis, theoretical insights from behavioral sciences were adopted as the guiding framework. Specifically, the theoretical underpinning of the study was grounded in the extensively documented understanding that behaviors could be both rational and irrational, as seen in the well-debated strengths and weaknesses of value-expectancy theories such as the Theory of Planned Behavior [ 54 , 55 , 56 ], for instance. In other words, the study investigated the research question via an empirically based understanding that, regardless of the scale and scope of the impacts of the actions, the policy-making process can be both rational and irrational. Furthermore, drawing insights from the Social Ecological Model [ 57 ], which posits that social behaviors are often shaped by a multitude of factors with divergent strengthens of influences that often manifest on varied levels of society, the study adopted a solution-focused mindset to address the research question—with difficulties galore, what can be done to improve the efficacy of pandemic policy making with substantially limited or eliminated unintended consequences?

In terms of peer-reviewed research, a total of 28 papers were included in the final review (see Table 2 ). The findings of the review were organized in accordance with the research aim—identify rigorous policy-making processes that could produce positive outcomes with limited to no unintended consequences in light of the unique challenges and opportunities of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to underscore that only a limited number of studies have investigated COVID-19 policies from a procedural perspective (e.g., [ 58 , 59 , 60 ]). In other words, instead of examining COVID-19 policies from a connected and comprehensive perspective, most of the research has focused on nuanced aspects of COVID-19 policy making, ranging from concrete facilitators (e.g., more effective prediction or monitoring of virus spread) and tangible barriers (e.g., lack of quality data), to the promises of advanced technology-enabled decision aids (e.g., AI-based decision models) (e.g., [ 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 ]) that could either hinder the smoothness or success of the policy-making process. However, while these insights could not answer the research question directly, they nonetheless were important and could be useful to tackle the research aim.

List of articles included in the final review.

Therefore, in light of the novelty of the research question and the dearth of research insights available in the literature, all relevant insights were thoroughly reviewed and analyzed. Overall, based on the literature review and the subsequent analysis, the result suggests that policy-making processes incorporating the following strategies could develop policies that have the potential of yielding desirable outcomes with limited unintended consequences:

people-centered: put people’s needs and wants at the center of the policy-making process, effectively prioritizing people over profits, politics, and the like [ 58 , 76 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 ];

artificial intelligence (AI)-powered: incorporating intelligent and automatic decision-making mechanisms to ensure the policies are developed based on the most updated evidence [ 83 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 ];

data-driven: the need to anchor key policy-making decisions with the support of empirical insights from quality data of optimal quantity and diversity [ 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 ];

supervision-enhanced: oversight mechanisms that scrutinize the behaviors of both the policy makers and the AI systems to further enhance policies’ abilities to produce positive outcomes without incurring unintended consequences [ 69 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 ].

To leverage these strategies’ interconnectedness, the people-centered, AI-powered, data-driven, and supervision-enhanced (PADS) model of policy making was subsequently developed. In the following section, the PADS model will be discussed in detail.

5. Discussion

This study aims to identify policy-making processes that have the potential to develop policies that could induce optimal desirable outcomes with limited to no unintended consequences amid COVID-19 and beyond. This is one of the first studies that investigated solutions that could shed light on the bevy of policy-making issues the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced or intensified, ranging from opaque and questionable policy-making processes and unquestioned and unchecked power of policymakers, to the unprecedented pace seen in the erosion of health equity and implosion of public dissent partially caused by unintended consequences of COVID-19 policies [ 109 , 110 , 111 ]. Aiming to address key issues in current policy-making practices—poor adoption of rigorous data analytics, lack of accountability, and oversized dependence on individual decision makers or policy makers, the study identified strategies that could establish and sustain the rigor in COVID-19 policy-making processes—the people-centered, AI-powered, data-driven, and supervision-enhanced (PADS) model of policy-making.

5.1. People-Centered

People-centered means to put people’s needs and wants at the center of the policy-making process, effectively prioritizing people over profits, politics, and the like [ 58 , 76 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 ]. It is important to note that “people” refers to all key stakeholders that are involved in the policy-making process, ranging from decision makers such as policy makers, decision supervisors such as independent experts, and decision benefactors such as the general public. Overall, it is important to underscore that the degree to which people agree with policies is a critical factor in shaping COVID-19 containment outcomes [ 112 , 113 ]. As the literature shows, how individuals adopt and comply with public policies, whether due to belief in science [ 114 ], economic concerns [ 115 ], political ideology [ 116 ], or perceived people-friendliness of the public policies (e.g., duration of the lockdown) [ 117 ], may influence the effectiveness of these policies in controlling the spread of COVID-19. In other words, public health policies, such as lockdowns, self-isolation, and spatial distancing measures are only effective if the public acts willingly in accordance with these measures [ 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 ].

By prioritizing the people’s collective interests over individual profits, partisan politics, or the dominant powers at the moment, the people-centeredness of the policy-making process or the PADS model could not only safeguard personal and public health, but also prompt better adherence to the resultant COVID-19 policies. Take China’s zero-COVID policy, for instance. The zero-COVID policy is a unique disease elimination/eradiation policy that has two pillars:

a “zero-tolerance” mindset that treats even single-digit positive COVID-19 cases or small disease outbreaks with the utmost urgency;

a “zero-delay” action plan that employs and deploys robust and rigorous collective and corroborative actions and measures to subdue positive cases and squash potential outbreaks.

Understandably, the zero-COVID policy and its use of mass quarantines and lockdowns are often considered draconian [ 118 ], particularly in light of the ever-loosening pandemic measures adopted by other societies [ 119 , 120 ]. However, as the policy is people-centered—developed factoring in the needs of all members of the society, including vulnerable communities such as older adults, frontline workers, and volunteers [ 67 , 121 , 122 ], and possibly future short-term residents such as participants of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Games [ 123 ]—the zero-COVID policy remains well supported and rigorously followed by the public [ 93 ].

5.2. AI-Powered

AI can be understood as machine programs or algorithms that are “able to mimic human intelligence” [ 124 ]. The AI-powered component of the PADS model emphasizes the importance of incorporating intelligent and automatic decision-making mechanisms to ensure the policies are developed based on the most updated and comprehensive evidence robustly analyzed [ 83 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 ]. Advanced AI systems can help policymakers to make more informed policies that are both reactive (retrospectively analyzing data to develop intelligent solutions) and proactive (predictive decision-making insights based on advanced modelling) in nature [ 125 , 126 , 127 ]. Furthermore, AI systems can often serve as the essential platform that enables other advanced technologies, ranging from augmented reality and virtual reality to mixed reality, if not the metaverse. In addition to AI’s role as the enabler, it can also perform the function of enhancer—improving performance of everyday services or commonplace information and communication technologies [ 125 , 126 , 127 ].

For example, AI-based systems could help government and health officers develop algorithms that incorporate in-depth and comprehensive insights gained on big data analysis on diverse data in the policy-making process, ranging from search queries, medical records, public health records, social media posts, online purchases, and wastewater to surveillance footage [ 83 , 124 ]. The potential of AI systems can be further amplified when coupled with 5G or 6G technologies; 6G, the sixth-generation networking technologies, can be understood as the next-generation transmission technique following the 5G communication strategies [ 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 ] with enhanced key performance indicators (KPIs) and a wider range of real-world applications. Both 5G and 6G technologies can offer substantially greater computing powers to further improve an AI system’s abilities to generate empirical-based intelligence [ 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 ]. Research shows that, for instance, analyzing social media posts can offer a grounded and timely insight into citizens’ needs and wants, as well as concerns and considerations in times of crisis such as the COVID pandemic [ 136 , 137 , 138 ]. Emerging insights also suggest that even small local governments in the U.S. have integrated social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, into their government functions [ 139 ], aiming to proactively incorporate public participation in the policy-making process.

5.3. Data-Driven

Data-driven entails the need to anchor key policy-making decisions upon the support of empirical evidence abstracted from quality data of great quantity and diversity [ 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 ]. Data-driven can refer to either big data analytics or data analyses based on smaller-scale databases. The importance of the data-driven element in the PADS model centers on the use and application of empirically gained insights, as opposed to subjective ideas, in the policy-making process. It is important to underscore that, thanks to advanced technologies such as 5G/6G and AI, a bevy of multifaceted information about public needs and preferences can be cost-effectively monitored, ranging from search queries, social media posts, and sewage data to medical records [ 83 ]. Having a diverse pool of heterogenous data paired with advanced computing powers provided by 5G/6G technologies and competent analytical skills enabled by AI means that government and health officials can gain a more complete and comprehensive understanding of the public’s perspective and sentiments towards key policy issues.

Data are, essentially, information about people. Depending on how the data were collected, they could either shed light on information on the people from a third-person perspective (e.g., surveillance footage), relevant information provided by the people via the lens of first-person perspective (e.g., digital diary), or information that is less reflective of differences in perspectives or transitory changes (e.g., biomedical data) [ 140 ]. In other words, the data-driven strategy could ensure that both the policy-making process and the resultant policies are founded on and reflective of the collective willpower from diverse perspectives. Overall, incorporating empirical evidence in the design, development, and delivery of policies to ensure the specific rules and regulations are in line with the general public’s needs and wants can be understood as a novel approach to public participation in policy making. Public participation can be understood as the involvement of the public in the government’s agenda-setting and decision-making processes [ 141 ]. Essentially, by incorporating big data about people, and oftentimes from people, the data-driven policy-making process constitutes a novel way of ensuring that the individual circumstances are sufficiently heard, considered, and reflected in the public policies, without demanding people’s physical presence in the policy-making process.

5.4. Supervision-Enhanced

To err is but human, and artificial intelligence is but a human creation. Noticeably, AI is intrinsically flawed in terms of its lack of ability to initiate ethical considerations and moral judgments [ 142 , 143 ]. In other words, regardless of how remarkable the AI-powered data analytical system might become, in light of the inherent flaws of AI systems—intelligent but without consciousness (e.g., ethical and moral considerations) [ 144 , 145 , 146 ]—it is essential to safeguard AI systems with instrumental human involvement, in the forms of both policy making by government and health officers and rigorous supervision by independent experts [ 106 ]. In other words, to effectively prevent AI from “augmenting disparities” [ 103 ] and fostering its abilities to address inequalities or accelerate integrity, sufficient supervision is needed.

Supervision can be understood as oversight mechanisms that scrutinize the behaviors of both the policy makers and the AI systems to further enhance the policies’ abilities to produce positive outcomes without incurring unintended consequences [ 69 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 ]. By rigorously leveraging the supervision-enhanced strategy, the PADS model could help society at large better limit or eliminate potential unintended consequences that could emerge in the policy development, deployment, or delivery processes. One way to form the supervision system is via incorporating an independent review board with rigorously vetted experts participating in the review board on a rotating basis. Other approaches, such as global collaboration [ 60 , 147 ], potentially paired with expertise from international health organizations such as the World Health Organization, may also work. Overall, in light of the multifaceted nature of the concept of “unintended consequences”, it is important to note that, while the presence and robustness of the supervision system are of utmost significance, having an “expert-review-needed” or supervision-needed mindset among policy makers is of equal importance.

One way to view unintended consequences is that they could either be a result of unplanned or unforeseen policy planning—”unplanned” refers to situations in which the negative outcomes are unintended but nonetheless not unanticipated [ 148 ], whereas “unforeseen” refers to scenarios in which policy makers were completely unaware of the potential unintended consequences. In other words, not all unintended consequences denote innocence and ignorance on the part of policy makers’—some policies might be made as a result of balancing pros and cons, which means that the welfare of some members of the society could be arbitrarily ignored or neglected during the policy-making process. These flaws could be reflected in AI systems as well [ 103 ], which could further compound the potential unintended consequences caused by the policies. A “supervision-needed” mindset could be the solution:

it could facilitate the establishment of policy-making practices that value the importance of supervision;

it could help policy makers avoid causing “unforeseen” consequences in the policy-making process;

it could help policy makers incorporate moral and ethical considerations, ranging from fairness, equality, and privacy to security concerns, in the policy-making process.

5.5. The Advantages of the PADS Model

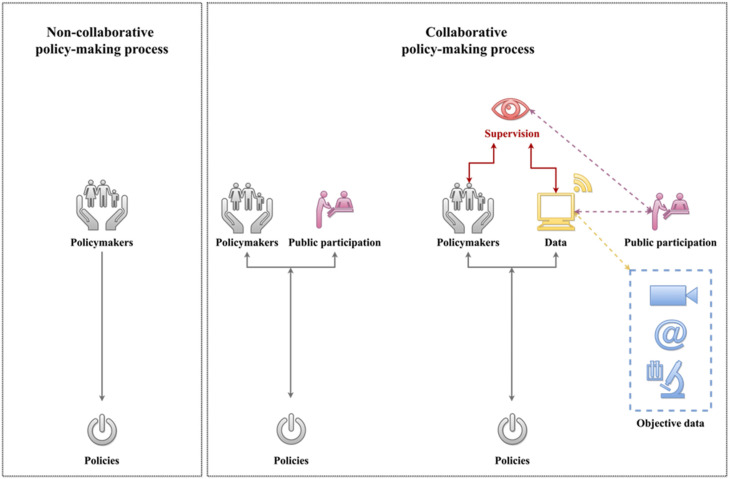

In line with the principle of parsimony [ 149 ], the policy-making process could be simplified into two collaborative and non-collaborative processes [ 60 , 150 ]. A non-collaborative policy-making process often only involves policy makers. In other words, stakeholders’ input or feedback is often not involved in the process. On the other hand, the collaborative policy-making process not only involves the policy makers, but also stakeholders as well. As the process of policy making evolves, the degree of stakeholder involvement differs across contexts. However, regardless of how the collaboration takes place, this collaborative policy-making process nonetheless suffers from a key flaw—oftentimes both the policymakers and the stakeholders’ input are subjective. A schematic representation of these two policy-making approaches can be found in Figure 1 .

A schematic representation of noncollaborative and collaborative policy-making processes.

Essentially, the leap from noncollaborative policy-making processes to collaborative policy-making processes only addresses one issue in the practice—the lack of public involvement in the decision-making process. In other words, though policies produced via the collaborative policy-making process might have greater abilities to address people’s needs and wants, they nonetheless could be flawed due to the highly subjective nature of the data upon which they are developed. One way to further improve the collaborative policy-making process is via replacing highly subjective and cross-sectional physical public participation with accumulated data that capture both the subjective and the objective needs and preferences of the stakeholders. In other words, data from the stakeholders (e.g., surveys), combined with data about the stakeholders (e.g., third-person perspective data such as surveillance footage, internet activities, etc.) and data about the overall situation from a multitude of perspectives, could serve as a considerably improved virtual proxy of public participation.

As evidence suggests, the general public may be well justified regarding whether or to what degree they wish to comply with COVID-19 public policies [ 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 ]. It is also worth noting that many, if not all, of the COVID-19 public policies were developed based on a top-down approach [ 151 , 152 ], and often without following the proper procedures that allow public participation in the policy-making process [ 153 , 154 ]. Though oftentimes public policy is held as a belief by some governments that “the governments decide to do or not to do” [ 155 ], as seen from COVID-19, for the greater good (e.g., achieve a post-pandemic reality), it should be considered and treated as a people-centered ecosystem that aims to serve the general public needs and preferences.

In other words, the data-driven component of PADS can effectively address issues that have been long plaguing policy-making: cross-sectional surveys about people’s needs and preferences are often flawed in offering stable and definitive insights about people, and longitudinal studies are often resource-dependent to conduct or limited in their abilities to provide timely insights into the subject matter. These insights combined suggest that the data-driven characteristics of the PADS model also share advantages that are commonly seen in general public participation in policy-making. It could:

better capture and comprehend the public’s needs and preferences;

design and develop public policies that are grounded in reality and people-centric; and in turn;

yield more desirable policy outcomes and limit potential unintended consequences [ 141 , 156 , 157 , 158 , 159 ].

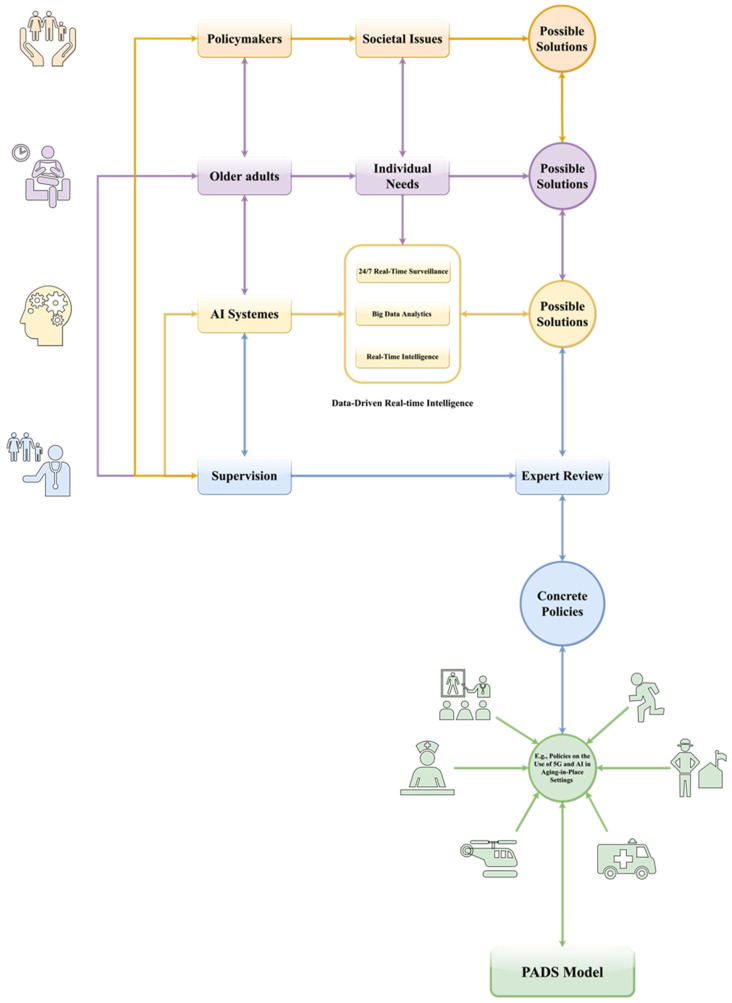

An example of applying the PADS model for developing policies on the use and application of 5G and AI technologies in the context of aging-in-place can be found in Figure 2 . Overall, Figure 2 illustrates how the people-centeredness of the PADS model respects and reflects key stakeholders’ needs and preferences in the policy-making process, with the aid of advanced technologies such as AI-powered systems and comprehensive supervision mechanisms.

An example utilization of the PADS model in the context of aging-in-place policies.

5.6. Limitations

While this study bridged important research gaps, it was not without limitations. For starters, the review only focused on relevant articles published in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This means that potentially valuable insights that were not COVID-19-specific were not included in the review. Due to the focus of the study, challenges such as developmental hurdles associated with the use and application of AI were not discussed in detail in the study. Furthermore, due to the conceptual nature of the PADS model, no empirical evidence about its real-world efficacy is available at the moment. While the efficacies of public health policies could be difficult to evaluate [ 46 ], future studies could nonetheless explore innovative approaches to gauge the effectiveness of the PADS model in generating promising policies.

6. Conclusions

Policies can be the defining factor in shaping personal and public health, especially amid global catastrophes such as COVID-19. Amid the ever-increasingly chaotic jungle of COVID-19 policy making and the rapidly intensifying public expectations of greater accountabilities among policymakers, it is then vital to investigate rigorous policy-making strategies that could help societies at large develop more cost-effective COVID-19 policies. Based on insights gained from reviewing and analyzing the state-of-the-art evidence in the literature, this study developed the PADS model, which proposes a people-centered, AI-powered, data-driven, and supervision-enhanced approach towards policy making amid COVID-19. The PADS model can develop policies that have the potential to induce optimal outcomes and limit or eliminate unintended consequences amid COVID-19 and beyond. Rather than serving as a definitive answer to problematic COVID-19 policy-making practices, the PADS model can be best understood as one of many promising frameworks that could bring the pandemic policy-making process more in line with the interests of societies at large; in other words, more cost-effectively, and consistently anti-COVID and pro-human.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to express her gratitude to the editor and reviewers for their constructive input and insightful feedback.

Abbreviations

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- 1. Skocpol T., Amenta E. States and social policies. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1986;12:131–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.001023. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Burnside C., Dollar D. Aid, Policies, and Growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000;90:847–868. doi: 10.1257/aer.90.4.847. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Von Solms R., von Solms B. From policies to culture. Comput. Secur. 2004;23:275–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2004.01.013. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Eddy D.M. Practice Policies: Where Do They Come From? JAMA. 1990;263:1265. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440090103036. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Su Z., Wen J., Abbas J., McDonnell D., Cheshmehzangi A., Li X., Ahmad J., Šegalo S., Maestro D., Cai Y. A race for a better understanding of COVID-19 vaccine non-adopters. Brain Behav. Immun. Health. 2020;9:100159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100159. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Grimes D.R. Medical disinformation and the unviable nature of COVID-19 conspiracy theories. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0245900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245900. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Shahsavari S., Holur P., Wang T., Tangherlini T.R., Roychowdhury V. Conspiracy in the time of corona: Automatic detection of emerging COVID-19 conspiracy theories in social media and the news. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2020;3:279–317. doi: 10.1007/s42001-020-00086-5. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Noel T.K. Conflating culture with COVID-19: Xenophobic repercussions of a global pandemic. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open. 2020;2:100044. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100044. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Su Z., McDonnell D., Ahmad J., Cheshmehzangi A., Li X., Meyer K., Cai Y., Yang L., Xiang Y.T. Time to stop the use of ‘Wuhan virus’, ‘China virus’ or ‘Chinese virus’ across the scientific community. BMJ Glob. Health. 2020;5:e003746. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003746. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Durante R., Guiso L., Gulino G. Asocial capital: Civic culture and social distancing during COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 2021;194:104342. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104342. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Su Z., McDonnell D., Cheshmehzangi A., Li X., Maestro D., Šegalo S., Ahmad J., Hao X. With great hopes come great expectations: Access and adoption issues associated with COVID-19 vaccines. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7:e26111. doi: 10.2196/26111. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Johns Hopkins University Mortality Analyses. 2021. [(accessed on 16 November 2021)]. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality .

- 13. Our World in Data Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) 2021. [(accessed on 8 November 2021)]. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus .

- 14. Anderson J.E. Public Policy-Making. 3rd ed. Houghton Mifflin; Boston, MA, USA: 1984. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Chriqui J.F. Obesity Prevention Policies in U.S. States and Localities: Lessons from the Field. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2013;2:200–210. doi: 10.1007/s13679-013-0063-x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Howlett M. Designing Public Policies: Principles and Instruments. Routledge; London, UK: 2019. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Lu G., Razum O., Jahn A., Zhang Y., Sutton B., Sridhar D., Ariyoshi K., von Seidlein L., Müller O. COVID-19 in Germany and China: Mitigation versus elimination strategy. Glob. Health Action. 2021;14:1875601. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1875601. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Howard J., Huang A., Li Z., Tufekci Z., Zdimal V., van der Westhuizen H.-M., von Delft A., Price A., Fridman L., Tang L.-H., et al. An evidence review of face masks against COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:2014564118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014564118. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Fu Y., Jin H., Xiang H., Wang N. Optimal lockdown policy for vaccination during COVID-19 pandemic. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021:102123. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2021.102123. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Balmford B., Annan J.D., Hargreaves J.C., Altoè M., Bateman I.J. Cross-Country Comparisons of COVID-19: Policy, Politics and the Price of Life. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020;76:525–551. doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00466-5. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. The Economist America Is in the Midst of an Extraordinary Surge of COVID-19. 2020. [(accessed on 11 August 2020)]. Available online: https://www.economist.com/united-states/2020/07/18/america-is-in-the-midst-of-an-extraordinary-surge-of-covid-19 .

- 22. Yu X., Ansari T. Coronavirus Latest: California Is First State to Pass 500,000 Infections. 2020. [(accessed on 11 August 2020)]. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/coronavirus-latest-news-08-01-2020-11596268447 .

- 23. Hawkins D., Iati M. Coronavirus Update: California Surpasses 10,000 Deaths as Trump Signs Economic Relief Orders. 2020. [(accessed on 11 August 2020)]. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/08/08/coronavirus-covid-updates/

- 24. Sibley C.G., Greaves L.M., Satherley N., Wilson M.S., Overall N.C., Lee C.H.J., Milojev P., Bulbulia J., Osborne D., Milfont T.L., et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2020;75:618–630. doi: 10.1037/amp0000662. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Galea S., Merchant R.M., Lurie N. The Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 and Physical Distancing: The Need for Prevention and Early Intervention. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180:817–818. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Verbeek H., Gerritsen D.L., Backhaus R., de Boer B.S., Koopmans R.T., Hamers J.P. Allowing Visitors Back in the Nursing Home During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Dutch National Study Into First Experiences and Impact on Well-Being. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2020;21:900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.020. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Brown E., Gray R., Monaco S.L., O’Donoghue B., Nelson B., Thompson A., Francey S., McGorry P. The potential impact of COVID-19 on psychosis: A rapid review of contemporary epidemic and pandemic research. Schizophr. Res. 2020;222:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.005. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Mazza C., Ricci E., Biondi S., Colasanti M., Ferracuti S., Napoli C., Roma P. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Guo Q., Zheng Y., Shi J., Wang J., Li G., Li C., Fromson J.A., Xu Y., Liu X., Xu H., et al. Immediate psychological distress in quarantined patients with COVID-19 and its association with peripheral inflammation: A mixed-method study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.038. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Su Z., Cheshmehzangi A., McDonnell D., Šegalo S., Ahmad J., Bennett B. Gender inequality and health disparity amid COVID-19. Nurs. Outlook. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.08.004. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Su Z., McDonnell D., Li Y. Why is COVID-19 more deadly to nursing home residents? QJM Int. J. Med. 2021;114:543–547. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa343. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Su Z., McDonnell D., Roth S., Li Q., Šegalo S., Shi F., Wagers S. Mental health solutions for domestic violence victims amid COVID-19: A review of the literature. Glob. Health. 2021;17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00710-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Su Z., McDonnell D., Wen J., Kozak M., Abbas J., Šegalo S., Li X., Ahmad J., Cheshmehzangi A., Cai Y., et al. Mental health consequences of COVID-19 media coverage: The need for effective crisis communication practices. Glob. Health. 2021;17:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00654-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Amnesty International UK: Older People in Care Homes Abandoned to Die Amid Government Failures During COVID-19 Pandemic. 2021. [(accessed on 16 November 2021)]. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2020/10/uk-older-people-in-care-homes-abandoned-to-die-amid-government-failures-during-covid-19-pandemic/

- 35. Wang F., Meng L.-R., Zhang Q., Li L., Nogueira B.O.L., Ng C.H., Ungvari G.S., Hou C.-L., Liu L., Zhao W., et al. Elder abuse and its impact on quality of life in nursing homes in China. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018;78:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2018.06.011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Myhre J., Saga S., Malmedal W., Ostaszkiewicz J., Nakrem S. Elder abuse and neglect: An overlooked patient safety issue. A focus group study of nursing home leaders’ perceptions of elder abuse and neglect. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020;20:199. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-5047-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Arens O.B., Fierz K., Zúñiga F. Elder Abuse in Nursing Homes: Do Special Care Units Make a Difference? A Secondary Data Analysis of the Swiss Nursing Homes Human Resources Project. Gerontology. 2016;63:169–179. doi: 10.1159/000450787. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Abbasi J. “Abandoned” Nursing Homes Continue to Face Critical Supply and Staff Shortages as COVID-19 Toll Has Mounted. JAMA. 2020;324:123–125. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10419. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Makaroun L.K., Bachrach R.L., Rosland A.-M. Elder Abuse in the Time of COVID-19—Increased Risks for Older Adults and Their Caregivers. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2020;28:876–880. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.017. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Sanderson I. Evaluation, Policy Learning and Evidence-Based Policy Making. Public Adm. 2002;80:1–22. doi: 10.1111/1467-9299.00292. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Banks G. World Scientific Reference on Asia-Pacific Trade Policies. World Scientific; Singapore: 2018. Evidence-Based Policy Making: What Is It? How Do We Get It? pp. 719–736. [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Richards G.W. How Research–Policy Partnerships Can Benefit Government: A Win–Win for Evidence-Based Policy-Making. Can. Public Policy. 2017;43:165–170. doi: 10.3138/cpp.2016-046. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Kemm J. The limitations of ‘evidence-based’ public health. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2006;12:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00600.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Foti K., Foraker R.E., Martyn-Nemeth P., Anderson C.A., Cook N.R., Lichtenstein A.H., de Ferranti S.D., Young D.R., Hivert M.-F., Ross R., et al. Evidence-Based Policy Making for Public Health Interventions in Cardiovascular Diseases: Formally Assessing the Feasibility of Clinical Trials. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2020;13:006378. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006378. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Sanderson I. Making sense of ‘what works’: Evidence based policy making as instrumental rationality? Public Policy Adm. 2002;17:61–75. doi: 10.1177/095207670201700305. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Whittington D., Radin M., Jeuland M. Evidence-based policy analysis? The strange case of the randomized controlled trials of community-led total sanitation. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy. 2020;36:191–221. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grz029. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Mazey S., Richardson J. Lesson-Drawing from New Zealand and COVID-19: The Need for Anticipatory Policy Making. Polit. Q. 2020;91:561–570. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12893. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Ngqangashe Y., Heenan M., Pescud M. Regulating Alcohol: Strategies Used by Actors to Influence COVID-19 Related Alcohol Bans in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:11494. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111494. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Sabatier P.A., Weible C. Theories of the Policy Process. 1st ed. Westview Press; Boulder, CO, USA: 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Stoker G., Evans M., editors. Evidence-Based Policy Making in the Social Sciences. Penguin; London, UK: 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Wallace-Wells B. What Happened to Joe Biden’s “Summer of Freedom” from the Pandemic? 2021. [(accessed on 8 November 2021)]. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-inquiry/what-happened-to-joe-bidens-summer-of-freedom-from-the-pandemic .

- 52. Phillips P.W., Castle D., Smyth S.J. Evidence-based policy making: Determining what is evidence. Heliyon. 2020;6:e04519. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04519. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Evanega S., Lynas M., Adams J., Smolenyak K., Insights C.G. Coronavirus Misinformation: Quantifying Sources and Themes in the COVID-19 ‘Infodemic’. Cornell University; Ithaca, NY, USA: 2021. [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Sniehotta F.F., Presseau J., Araújo-Soares V. Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014;8:1–7. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2013.869710. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Muthusamy G.A.P., Cheng K.T.G. The rational—Irrational dialectic with the moderating effect of cognitive bias in the theory of planned behavior. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020;7:240–250. [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour is alive and well, and not ready to retire: A commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015;9:131–137. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.883474. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 1977;32:513–531. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Ullah A., Pinglu C., Ullah S., Abbas H.S.M., Khan S. The Role of E-Governance in Combating COVID-19 and Promoting Sustainable Development: A Comparative Study of China and Pakistan. Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2021;6:86–118. doi: 10.1007/s41111-020-00167-w. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Marrazzo V. Research and Innovation Forum 2021. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2021. The implementation and use of technologies and big data by local authorities during the COVID-19 pandemic. [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Marten R., El-Jardali F., Hafeez A., Hanefeld J., Leung G.M., Ghaffar A. Co-producing the COVID-19 response in Germany, Hong Kong, Lebanon, and Pakistan. BMJ. 2021;372:n243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n243. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Tutsoy O. COVID-19 Epidemic and Opening of the Schools: Artificial Intelligence-Based Long-Term Adaptive Policy Making to Control the Pandemic Diseases. IEEE Access. 2021;9:68461–68471. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3078080. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Maor M., Howlett M. Explaining variations in state COVID-19 responses: Psychological, institutional, and strategic factors in governance and public policy-making. Policy Des. Pract. 2020;3:228–241. doi: 10.1080/25741292.2020.1824379. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Bertozzi A.L., Franco E., Mohler G., Short M.B., Sledge D. The challenges of modeling and forecasting the spread of COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:16732–16738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006520117. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Jinjarak Y., Ahmed R., Nair-Desai S., Xin W., Aizenman J. Accounting for Global COVID-19 Diffusion Patterns, January–April 2020. Econ. Disasters Clim. Chang. 2020;4:515–559. doi: 10.1007/s41885-020-00071-2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Adiga A., Chen J., Marathe M., Mortveit H., Venkatramanan S., Vullikanti A. Data-driven modeling for different stages of pandemic response. J. Indian. Inst. Sci. 2020;100:901–915. doi: 10.1007/s41745-020-00206-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 66. Coston A., Guha N., Ouyang D., Lu L., Chouldechova A., Ho D.E. Leveraging administrative data for bias audits: Assessing disparate coverage with mobility data for COVID-19 policy; Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency; Online. 3–10 March 2021; New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. pp. 173–184. [ Google Scholar ]

- 67. Baker M.G., Wilson N., Blakely T. Elimination could be the optimal response strategy for COVID-19 and other emerging pandemic diseases. BMJ. 2020;371:m4907. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4907. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 68. Brauner J.M., Mindermann S., Sharma M., Johnston D., Salvatier J., Gavenčiak T., Stephenson A.B., Leech G., Altman G., Mikulik V., et al. Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19. Science. 2021;371:eabd9338. doi: 10.1126/science.abd9338. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 69. Blasimme A., Vayena E. What’s next for COVID-19 apps? Governance and oversight. Science. 2020;370:760–762. doi: 10.1126/science.abd9006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 70. Brooks-Pollock E., Danon L., Jombart T., Pellis L. Modelling that shaped the early COVID-19 pandemic response in the UK. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021;376:20210001. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2021.0001. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 71. Christensen T., Lægreid P. Balancing Governance Capacity and Legitimacy: How the Norwegian Government Handled the COVID-19 Crisis as a High Performer. Public Adm. Rev. 2020;80:774–779. doi: 10.1111/puar.13241. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 72. Duffey R.B., Zio E. COVID-19 Pandemic Trend Modeling and Analysis to Support Resilience Decision-Making. Biology. 2020;9:156. doi: 10.3390/biology9070156. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 73. Kreuter F., Barkay N., Bilinski A., Bradford A., Chiu S., Eliat R., Fan J., Galili T., Haimovich D., Kim B., et al. Partnering with a global platform to inform research and public policy making. Surv. Res. Methods. 2020;14:159–163. [ Google Scholar ]

- 74. Harrison T.M., Pardo T.A. Data, politics and public health: COVID-19 data-driven decision making in public discourse. Digit. Gov. Res. Pract. 2020;2:1–8. doi: 10.1145/3428123. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 75. Hasan A., Putri E., Susanto H., Nuraini N. Data-driven modeling and forecasting of COVID-19 outbreak for public policy making. ISA Trans. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.isatra.2021.01.028. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 76. Lee S., Hwang C., Moon M.J. Policy learning and crisis policy-making: Quadruple-loop learning and COVID-19 responses in South Korea. Policy Soc. 2020;39:363–381. doi: 10.1080/14494035.2020.1785195. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 77. Liu P., Zhong X., Yu S. Striking a balance between science and politics: Understanding the risk-based policy-making process during the outbreak of COVID-19 epidemic in China. J. Chin. Gov. 2020;5:198–212. doi: 10.1080/23812346.2020.1745412. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 78. Manski C.F. Forming COVID-19 Policy Under Uncertainty. J. Benefit-Cost Anal. 2020;11:341–356. doi: 10.1017/bca.2020.20. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 79. Ning Y., Ren R., Nkengurutse G. China’s model to combat the COVID-19 epidemic: A public health emergency governance approach. Glob. Health Res. Policy. 2020;5:34. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00161-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 80. Panovska-Griffiths J., Kerr C., Waites W., Stuart R. Mathematical modeling as a tool for policy decision making: Applications to the COVID-19 pandemic. Handb. Stat. 2021;44:291–326. doi: 10.1016/bs.host.2020.12.001. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 81. Qiu R.G., Wang E., Gong I. Data-Driven Modeling to Facilitate Policymaking in Fighting to Contain the COVID-19 Pandemic. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021;185:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2021.05.034. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 82. Sartor G., del Riccio M., Poz I.D., Bonanni P., Bonaccorsi G. COVID-19 in Italy: Considerations on official data. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;98:188–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.060. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 83. Su Z., McDonnell D., Bentley B.L., He J., Shi F., Cheshmehzangi A., Ahmad J., Jia P. Addressing Biodisaster X Threats with Artificial Intelligence and 6G Technologies: Literature Review and Critical Insights. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021;23:e26109. doi: 10.2196/26109. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 84. Willi Y., Nischik G., Braunschweiger D., Pütz M. Responding to the COVID-19 Crisis: Transformative Governance in Switzerland. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2020;111:302–317. doi: 10.1111/tesg.12439. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 85. Yu S., Qing Q., Zhang C., Shehzad A., Oatley G., Xia F. Data-Driven Decision-Making in COVID-19 Response: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2021;8:1016–1029. doi: 10.1109/TCSS.2021.3075955. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 86. Zawadzki R.S., Gong C.L., Cho S.K., Schnitzer J.E., Zawadzki N.K., Hay J.W., Drabo E.F. Where Do We Go from Here? A Framework for Using Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered Models for Policy Making in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Value Health. 2021;24:917–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.03.005. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 87. Zheng Q., Jones F.K., Leavitt S.V., Ung L., Labrique A.B., Peters D.H., Lee E.C., Azman A.S., Adhikari B., Wahl B., et al. HIT-COVID, a global database tracking public health interventions to COVID-19. Sci. Data. 2020;7:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-00610-2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 88. Bayram M., Springer S., Garvey C.K., Özdemir V. COVID-19 Digital Health Innovation Policy: A Portal to Alternative Futures in the Making. OMICS A J. Integr. Biol. 2020;24:460–469. doi: 10.1089/omi.2020.0089. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 89. Feijóo C., Kwon Y., Bauer J.M., Bohlin E., Howell B., Jain R., Potgieter P., Vu K., Whalley J., Xia J. Harnessing artificial intelligence (AI) to increase wellbeing for all: The case for a new technology diplomacy. Telecommun. Policy. 2020;44:101988. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2020.101988. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 90. Wang B., Wen X. China’s Stringent COVID-19 Control Measures People-Centered, Coordinated Approach. 2021. [(accessed on 12 October 2021)]. Available online: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202108/18/WS611cbd84a310efa1bd6699c5.html .

- 91. Institut Économique Molinari The Zero COVID Strategy Protects People, Economies and Freedoms More Effectively. 2021. [(accessed on 3 October 2021)]. Available online: https://www.institutmolinari.org/2021/08/19/the-zero-covid-strategy-protects-people-economies-and-freedoms-more-effectively/

- 92. Liu C. China’s ‘Zero Tolerance’ COVID-19 Policy to Safeguard the Country to Withstand Epidemic Flare-Ups Amid Holidays. 2021. [(accessed on 5 October 2021)]. [Cited 5 October 2021] Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202109/1234763.shtml .

- 93. Zhou X. China’s Zero COVID Strategy Has the Support of Its People. 2021. [(accessed on 7 November 2021)]. Available online: https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/China-s-zero-COVID-strategy-has-the-support-of-its-people .

- 94. Allam Z., Dey G., Jones D.S. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Provided Early Detection of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) in China and Will Influence Future Urban Health Policy Internationally. AI. 2020;1:156–165. doi: 10.3390/ai1020009. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 95. Syrowatka A., Kuznetsova M., Alsubai A., Beckman A.L., Bain P.A., Craig K.J.T., Hu J., Jackson G.P., Rhee K., Bates D.W. Leveraging artificial intelligence for pandemic preparedness and response: A scoping review to identify key use cases. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021;4:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00459-8. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 96. Ndiaye M., Oyewobi S.S., Abu-Mahfouz A.M., Hancke G.P., Kurien A.M., Djouani K. IoT in the Wake of COVID-19: A Survey on Contributions, Challenges and Evolution. IEEE Access. 2020;8:186821–186839. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3030090. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 97. Xiao H., Zhou L., Liu L., Li X., Ma J. Historic opportunity: Artificial intelligence interventions in COVID-19 and other unknown diseases. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2021;53:1575–1577. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmab120. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 98. Ghafouri-Fard S., Mohammad-Rahimi H., Motie P., Minabi M.A., Taheri M., Nateghinia S. Application of machine learning in the prediction of COVID-19 daily new cases: A scoping review. Heliyon. 2021;7:08143. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08143. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 99. Saxena N., Gupta P., Raman R., Rathore A.S. Role of data science in managing COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Chem. Eng. 2020;62:385–395. doi: 10.1080/00194506.2020.1855085. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 100. Verma A.A., Slutsky A.S., Razak F. The consequences of neglecting to collect multisectoral data to monitor the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2021;193:E1600. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.80136. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 101. Hussain A., Tahir A., Hussain Z., Sheikh Z., Gogate M., Dashtipour K., Ali A., Sheikh A. Artificial Intelligence–Enabled Analysis of Public Attitudes on Facebook and Twitter Toward COVID-19 Vaccines in the United Kingdom and the United States: Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021;23:e26627. doi: 10.2196/26627. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 102. Raineri P., Molinari F. Introduction to Nanotheranostics. Springer; Singapore: 2021. Innovation in Data Visualisation for Public Policy Making; pp. 47–59. [ Google Scholar ]

- 103. Leslie D., Mazumder A., Peppin A., Wolters M.K., Hagerty A. Does “AI” stand for augmenting inequality in the era of COVID-19 healthcare? BMJ. 2021;372:n304. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n304. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 104. Griglio E. Parliamentary oversight under the COVID-19 emergency: Striving against executive dominance. Theory Pract. Legis. 2020;8:49–70. doi: 10.1080/20508840.2020.1789935. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 105. Bolleyer N., Salát O. Parliaments in times of crisis: COVID-19, populism and executive dominance. West Eur. Politi. 2021;44:1103–1128. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2021.1930733. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 106. Cave S., Whittlestone J., Nyrup R., Heigeartaigh S.O., Calvo R.A. Using AI ethically to tackle covid-19. BMJ. 2021;372:n364. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n364. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 107. Krass M., Henderson P., Mello M.M., Studdert D.M., Ho D.E. How US law will evaluate artificial intelligence for COVID-19. BMJ. 2021;372:n234. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n234. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 108. Carrapico H., Farrand B. Discursive continuity and change in the time of COVID-19: The case of EU cybersecurity policy. J. Eur. Integr. 2020;42:1111–1126. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2020.1853122. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 109. Su Z., McDonnell D., Li X., Bennett B., Šegalo S., Abbas J., Cheshmehzangi A., Xiang Y.-T. COVID-19 Vaccine Donations—Vaccine Empathy or Vaccine Diplomacy? A Narrative Literature Review. Vaccines. 2021;9:1024. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9091024. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 110. Barberia L.G., Gómez E.J. Political and institutional perils of Brazil’s COVID-19 crisis. Lancet. 2020;396:367–368. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31681-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 111. Chernozhukov V., Kasahara H., Schrimpf P. Causal impact of masks, policies, behavior on early COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. J. Econ. 2021;220:23–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.09.003. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]